REGISTER NOW FOR FIRST NATIONS

EXECUTIVE EDUCATION 2026 PROGRAMS

Why Choose FNEE?

Empowering First Nations leaders with tools, knowledge, and connections to drive change and create a lasting impact in their communities

Our Programs:

✔ Governance – Grow an Agile and Innovative Leadership

✔ Entrepreneurship – Strengthen Your Entrepreneurial Skills

✔ Management – Boost your collaborative approach

✔ Women Leadership – Reach your full potential

✔ Economic Reconciliation – Co-lead a Reconciliation Project

✔ Next Generation – Trail forward

by Will Nicholls

October was a hard month. First, I mourned the passing of my Aunt Maggie, a difficult moment for my family. This was followed by the passing of Davey Bobbish and then came my old friend Buckley Petawabano.

Not only did Buckley and I talk about many different things, but when I took over CINI-FM he was the president who justified my actions. He was special – something most Mistissini people acknowledged and were proud of. He’s a person our youth may not know as his stories have not been written down yet or passed on verbally.

There is another person who joined the list of the departed and that was Robert Baribeau. I didn’t share my grief in early October as I felt it would be lost amongst all the other grief.

Robert was one of my first employees when I ran the Mistissini radio station. He was a young lad with a smile that came easy to his lips. His laughter was infectious and made you want to join in. He loved working with us and enjoyed joking around a lot.

Despite the fun, he always completed the job he was given, something I know was always part of his life. Hell, one time he had me doing a bench press, which was over my weight. I managed to do it twice before I had to stop. To my surprise he said he never would have tried pressing that much and told me he was proud that I managed to pull it off.

Robert gave me many challenges and a friendship I returned without ever looking at the cost because I knew he felt the same way. His friendship was freely given until you abused it. It’s something I understand as do many Cree.

We take care of each other as long as sharing and respect is a two-way street. With Robert it was a matter weighed or considered when determining his opinion or plan involving anyone he knew.

In the end, all I can say is Robert was a special friend who I will miss. As do the many others who feel the same way about him.

Good night, Robert. The peace you feel in the long night is something that came much too soon.

18 Buckley Petawabano remembered

/ ads@nationnews.ca / 514-943-6191 // HEAD OFFICE: P.O. Box 151, Chisasibi, QC. J0M 1E0 www.nationnews.ca // EDITORIAL: will@nationnews.ca news@nationnews.ca // ADS: Donna Malthouse: donna@beesum.com // SUBSCRIPTIONS: $60 plus taxes, US: $90, Abroad: $110, Payable to beesum communications, all rights reserved, publication mail #40015005, issn #1206-2642 // the Nation is a member of: The James Bay Cree Communications Society, Circle Of Aboriginal Controlled Publishers, Magazines Canada Quebec Community Newspaper Assn. Canadian Newspapers Assn. Les Hebdos Sélect Du Québec. Funded [in part] by the Government of Canada // ONLINE AT: www.nationnews.ca | facebook.com/NATIONnewsmagazine | Twitter: @creenation_news

by Patrick Quinn, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

With concerns about declining moose populations, inland Cree communities and regional entities introduced initiatives to limit harvests this hunting season. However, the Cree Trappers’ Association’s management plan in the heavily impacted Zone 17 has met with mixed results so far.

After a 2021 aerial survey found a 35% drop in areas near Waswanipi, Ouje-Bougoumou and Waskaganish, the sports hunt for non-Natives was suspended in Zone 17 and the CTA introduced new measures for Cree hunters, including a permit system and a recommended harvest limit of two moose per trapline.

Based on community consultations and tallyman input, permit tags were to be evenly distributed to impacted traplines. Tallymen retain full authority to distribute tags among trusted hunters, respecting family and community needs, and can change hunters for different dates. Hunters may submit permission forms to their local CTA, who provide authorization under the tallyman’s conditions.

"Tallymen are getting frustrated because they want to follow the guidelines in Zone 17, but some hunters don’t follow them," said Gordon Saganash, the CTA moose management coordinator in Ouje-Bougoumou. "It’s way off the limit."

From the community’s 10 traplines in Zone 17, Saganash has recorded 12 females, 20 males and 5 calves harvested so far this year – far exceeding two per trapline. That’s not counting those

who neglect to report their harvests, some who try to avoid him when he visits after being tipped off by other community members.

"There’s a lot of poachers around, at night too," said Saganash. "The white people who had camps in Zone 17 have moved to Zone 16. Maybe they should give out fines to people who aren’t respecting guidelines. I recommend hiring monitors travelling from trapline to trapline."

A community meeting is planned for November 18 to discuss potential solutions. To better understand the current status of moose, which some land users have reported as abundant this year, the CTA is asking hunters in Zone 17 to submit incisor moose teeth to local administrators to determine their age.

The regional CTA stated that wildlife protection officers may address unsafe hunting practices by imposing fines or taking away equipment. While nighttime hunting is to be avoided, orange safety vests and hats should be worn, which moose are mostly colourblind to.

"We were taught once the sun sets not to harvest," said Waskaganish Elder George L. Diamond. "The way we hunt needs to change – we’re not sports hunters or trophy gatherers. We have to have respectful ways of harvesting and share the food that we harvest."

With a huge increase in the number of both hunters and roads in the territory, Diamond said hunters calling moose from the highway are creating a safety hazard for drivers. He offered a practi-

cal reason for not chasing moose with snowmobiles in wintertime – "the meat doesn’t taste good."

While Diamond emphasized not killing female moose to encourage them giving birth to calves, longtime Waswanipi forest and wildlife consultant Allan Saganash suggested this was most important in the late winter but not necessarily pragmatic in the autumn because "that’s all we see out there" and harvesting only the male population could further limit reproduction.

With 33 traplines covering more than half of Waswanipi territory in Zone 17, the community is particularly impacted by moose management measures. Tallymen in neighbouring zones such as Zone 22 are reporting an excess of hunting activity. Establishing harvesting quotas is complicated because moose wander between traplines.

"Crees should ban all non-Native moose sports hunting on all Cree ancestral lands, not only in Zone 17, out of respect for settlers and Indians living peacefully together," asserted Waswanipi tallyman Paul Dixon. "The solutions proposed or brought to the conservation table are all just band-aid solutions to a life or death of our Cree culture."

Allan Saganash believes limiting the number of moose killed per trapline overlooks the fact that several families may be living there, potentially all hunting moose on the same day without realizing it. Some traplines have more moose than

others because of the forest structure, development impacts and other reasons.

"I’ve seen four moose killed on a trapline in the same day and they don’t know it," said Saganash. "You can’t stop people from hunting, no matter how you try to apply these measures. A moose is a moose to a Cree because it’s meat – it’s very difficult to control that."

Saganash asserted that the community’s 30,000 km of forestry roads are the root of the problem, with moose sheltering in the patchwork forest left standing easily picked off by high-calibre rifles when they move to the clearings to feed on new growth. Development has dramatically altered the area’s landscape and wildlife, with eagles and vultures now prevalent and smaller species like muskrats suffering a severe decline.

"What’s happening in Zone 17 is a prime example of problems that other communities will be having," suggested Saganash. "The JBNQA protects Cree hunters’ rights to hunt, fish and trap. It doesn’t necessarily mean to abuse the number of species taken off the trapline."

Diamond shared a story of his Uncle Philip, who had walked several miles to Muskachii (Bear Mountain) to look for big game, which could always be relied upon when food was in short supply.

"Uncle Philip harvested only one male moose even though he saw seven moose that he could have easily killed," Diamond recounted. "This is our Cree teaching and it has been with us for thousands of years – harvest only what you need, leave something for later."

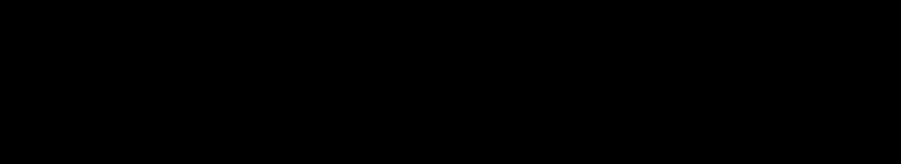

The Christopher Wapachee Memorial Foundation launches a new website by Natalia Fedosieieva

hen tragedy struck in 2007 with the loss of their 19-year-old son, Teddy and Marianne Wapachee channeled their grief into creating the Christopher Wapachee Memorial Foundation (CWMF), which launched a new website to continue sharing his legacy and supporting the community of Nemaska.

“It’s been 18 years since Christopher passed away on May 18, 2007,” said his father Teddy Wapachee, president of the CWMF.

“A community member once told me we should do something to keep his memory alive. That’s how the idea for the foundation was born,” he explained.

Founded in 2008, the CWMF has grown into a cornerstone of community support in Nemaska. Every year, it financially assists nearly 40 members for activities across its four pillars: Sports and Recreation; Arts and Culture; Education; and Health and Well-Being.

According to Wapachee, the volunteer-driven foundation operates with the help of dedicated team members, like Norman Wapachee and Joshua Paul Iserhoff, who ensure that all funds raised go toward community initiatives.

“To sustain the programs, the foundation organizes an annual charity golf tournament, which has become a major fundraiser and a cherished community tradition,” Wapachee said.

Building on this spirit of connection and growth, the CWMF recently launched its official website (cwmf.ca).

“People can apply for support on the website,” Wapachee pointed out. “It will help us reach more people and share Christopher’s story. The foundation not just about financial help, it’s about keeping his spirit alive.”

The website will also provide a way for people to make donations, since the foundation operates without government financial support and relies on contributions to sustain its initiative.

“As long as we continue this work, Christopher’s memory will always live on through every young person who learns, plays, creates or grows because of the foundation,” shared Wapachee.

For Iserhoff, serving as a CWMF board director has been both a commitment of the heart and a duty to his community.

“I’ve been part of the foundation since 2010, three years after Christopher passed,” Iserhoff said. “It was the right time to create something meaningful in his memory.”

The annual golf tournament has been supporting Nemaska youth in sports activities for nearly 15 years. But now that the foundation has expanded its mandate to include other activities, more funding is needed, Iserhoff said.

The CWMF is working to create a simple, centralized online application with clickable options for each category, replacing the current letter-based process and making applying easier for community members.

Iserhoff believes with the website will transform how the organization operates.

“We wanted to make it very easy for our people to access instead of using Facebook or emails or directly contacting the board of directors,” he stated. “The website will centralize all the information and help us when we meet every two months to look at the applications and approve them.”

Although still a work in progress, Iserhoff says the website is a vital tool to support youth and strengthen the community.

Mistissini mourns hit-and-run victim

Mistissini community members gathered on November 6 for a candlelight vigil honouring the life of 15-year-old Dylanna Capassasit, who was fatally struck in a hit-and-run accident on St-John Street. The Eeyou Eenou Police Force had found the victim unresponsive on the evening of November 3 and her death was confirmed shortly after being transported to the local clinic.

"This loss has touched our entire school community," stated Voyageur Memorial High School. "We extend our heartfelt love and condolences to Dylanna’s family and loved ones during this unimaginably difficult time. We want everyone to remember – you are not alone."

The EEPF requested the Sûreté du Québec’s Major Crimes Unit for assistance. Taken into custody was 24-year-old Myra Longchap, facing charges for failure to stop after an accident, accident resulting in bodily harm, and accident resulting in death. Longchap is scheduled to return to court on November 25. She was already awaiting trial in another case regarding charges of theft and fraud.

The Mistissini Youth Council said that hymns would be sung during the candlelight vigil and community walk to bring comfort, peace and healing. Liam Swallow

remembered Dylanna’s strong spirit and cultural pride during a school trip to OujeBougoumou last year for an Annie Whiskeychan Day event.

"She carried the heartbeat of Cree culture in everything she did," said Swallow. "Proud, curious and full of love for our culture and language. It’s a memory I will forever cherish."

Dylanna’s teacher of the last two years, Dominique Roy, remembered her as "athletic, determined, gentle, kind, creative, artistic and empathetic with a deep love for your culture."

"I doubt you ever realized just how many lives you touched just by being you," shared Roy. "You are gone way too soon with so much life left to live; endless potential and possibilities were ahead. Your quiet presence is and will be missed; your laughter still heard."

National Geographic highlights Nibiischii Park

National Geographic has named Mistissini’s Nibiischii Park a "must-visit destination" in a new article highlighting the "best places in the world to travel to in 2026." Located in the heart of Eeyou Istchee, Nibiischii is Quebec’s most recent national park and its first to be managed by a First Nation.

"Waconichi Lake’s waterfront cabins, floating chalets and sauna provide a summer wilderness retreat for anglers and paddlers, as well as wildlife-watchers, who can take in panoramas of the lake and surrounding boreal forest from a new cliffside walkway and suspension bridge," noted National Geographic.

With over 12,000 square kilometres of protected area in the province’s largest wildlife reserve encompassing Albanel, Mistassini and Waconichi lakes, Nibiischii was celebrated by the Indigenous Tourism Awards earlier this year as "a leader in ecotourism and sustainability." In September, Conrad Mianscum was appointed its deputy park director.

Although Nibiischii Park is still under development and not yet fully open to visitors, numerous innovative accommodations and attractions are accessible. Now open year-round, last winter for the first time it launched Cree-led activities including fireside storytelling, crafting workshops, and wilderness survival classes.

Promoting this prestigious honour, Eeyou Istchee Baie-James regional tourism suggested the Nibiischii Corporation represents an inspiring gateway to the territory, illustrating how a community can balance conservation, cultural transmission and sustainable development.

Mural unveiled for Treaties Recognition Week

Family members of the late Tragically Hip singer Gord Downie joined a gathering in Amherstview, Ontario on October 20 to celebrate the opening of the latest Downie Wenjack Fund legacy space.

The fund is intended to honour the memory and legacy of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old who died of hunger and exposure after escaping the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora in October 1966.

In his final years before passing in 2017, Downie worked closely with the Wenjack family to create the “Secret Path” project, which shared Wenjack's story through music, a graphic novel and a film. This year alone, over 9,500 Legacy Schools are engaging with “Secret Path” in classrooms throughout the country.

The room in Amherstview's recreation centre, just west of Kingston, is equipped with books, paintings and information about Wenjack and his story. The fund has opened over 100 spaces across Canada, mostly in schools, libraries and hospitals.

"I think he knew that this was going to be important and was going to outlive him, so yeah, he would be very proud,” said Gord's brother Mike Downie. He said when Gord knew his time was short with brain cancer, he wanted to draw greater attention to reconciliation and residential school experiences.

Local Anishinaabe Elder Judi Montgomery told APTN News that the recreation centre was an ideal space for people to learn more about the issue "and we’re here to help open people’s eyes.”

In the 1600s and 1700s, Europeans began colonizing North America, including Eeyou Istchee, to obtain land and resources that directly developed their own empires and economies. They did so, in complete disregard and disrespect of the existence, rights and interests of the Indigenous Peoples who used and occupied the land.

European sovereigns, at the time of contact with Indigenous Peoples, generally did not recognize the validity of Indigenous civilizations who occupied the “Americas.” The Europeans classed them as “savages.”

We, Eeyou/Eenou of Eeyou Istchee, like other First Nations across Canada, came through this dreadful past of colonization which included dispossession of our lands, imperialism, imposition of a foreign state and government, denial of rights, politics of exclusion, forced relocation or eviction, systemic racism, marginalization, and ongoing cultural genocide and assimilation.

For centuries, since the arrival of Europeans to the shores of our homeland, this dreadful history has repeated itself.

And this history was to repeat itself when the James Bay Hydroelectric Development Project was announced by Quebec in 1971.

However, we, Eeyou/ Eenou of Eeyou Istchee, stood up against the governments and Hydro-Québec to oppose the James Bay Project and defend our rights, Eeyou Istchee, and Eeyou/ Eenou Eedouwun.

We did so even though we didn’t have money to orga-

(This article was edited for space; the full article is on the Nation’s website.)

nize a challenge, as Indian Affairs then controlled and managed band funds.

The Indian Act denied us self-determination, and the federal government denied us, amongst other rights, the right to govern ourselves as it exercised substantial control over our lives and communities.

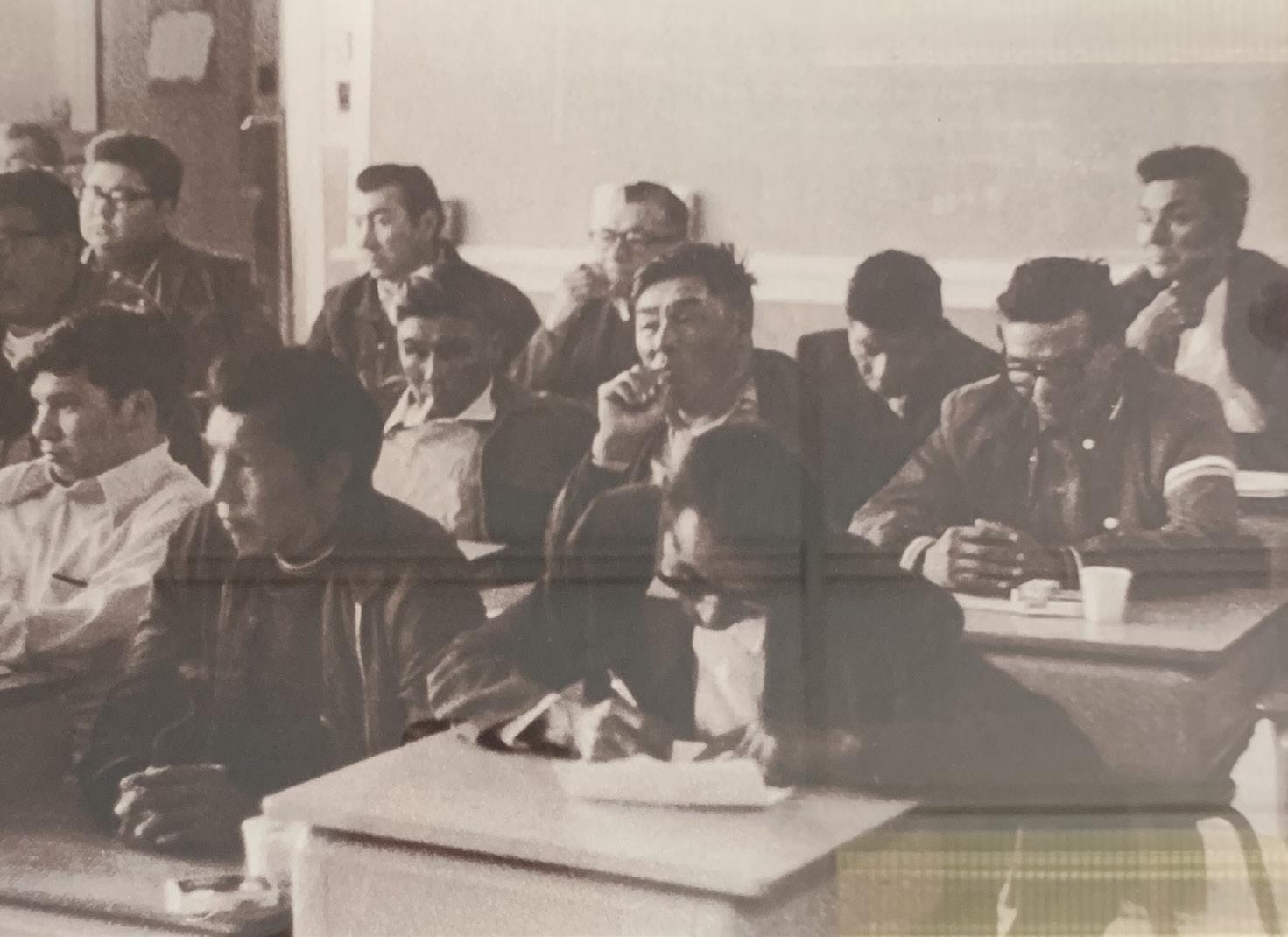

We didn’t have an organization like the Grand Council of the Crees. In the early 1970s, the Eeyou/Eenou of about 6,400 people were living in six isolated communities and had no access roads or local airstrips.

Nevertheless, in 1971, when the James Bay Hydroelectric Development Project was announced by Quebec, slated for construction in Eeyou Istchee, without consultations with us or consent from us, we challenged the authorities and proponents and commenced our journey for social justice and full self-government.

On the 50th anniversary of the signing of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement in 1975, I want to share my personal account and perspective on the Eeyou/Eenou journey for social justice over these 50 years.

In April 1971, I learned about the James Bay Hydroelectric Development Project in the English-language newspapers. Eeyou/Eenou people did not have televisions, but they had radios. They were not contacted by the governments or the developers before the project was announced. The project as planned would cause serious and devastating impacts on the Eeyou/Eenou of Eeyou Istchee, and their hunting territories and communities.

I immediately took the newspapers to Chief Smally Petawabano of the Mistissini Eenouch. Because of

its impacts on Eeyou/Eenou of Eeyou Istchee, Chief Petawabano and I concluded that the Chiefs of Eeyou Istchee should gather in Mistissini to discuss the threatening project. I managed to obtain some funding from an academic institution to partially fund this meeting.

Mistissini residents, like AnneMarie Awashish, Edna Neeposh, Louise Shecapio and Daisy Longchap, helped in the organization of the meeting and found accommodations for the Chiefs in local homes. Chief Petawabano invited the coastal and inland Chiefs. I invited Chief Billy Diamond of the Rupert’s House Band since I knew him from our Indian residential school days.

With financial assistance of the Indians of Quebec Association, the historic meeting of the Eeyou/Eenou Chiefs took place for three days in Mistissini on June 30, July 1-2, 1971. This meeting was the first time that the Chiefs got together to discuss common issues in the history of the Eeyou. The Chiefs decided to act in unity as one nation and one voice to oppose the James Bay Project and defend our land, rights and Eedouwun. That decision empowered the Eeyou/ Eenou of Eeyou Istchee, as they were no longer acting as separate bands and communities. Thus, the Eeyou/Eenou of Eeyou Istchee commenced their journey for political and social justice.

The Chiefs, in this historic meeting, asked Chief Diamond and I to assist them in the organization of their opposition to the James Bay Project and to get more information about it.

Following this gathering, Chief Diamond became the public face, voice and leader of the Eeyou/Eenou of Eeyou Istchee in our journey for justice. He

was the first Grand Chief. I thank the late Grand Chief Diamond for his tremendous contribution and valuable leadership in our journey.

We faced enormous odds and barriers in our journey for social justice. Many thought our fight was hopeless against such powerful governments and corporations.

We sought social justice and effective self-governance through political action, litigation and negotiation.

After four years of relentless efforts and struggles, on November 11, 1975, the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement was signed by the Eeyou and Inuit representatives, and representatives of Canada, Quebec and corporations such as Hydro-Québec.

The JBNQA is a modern treaty respecting our land and rights, and an accommodation with a modified James Bay Hydroelectric Development Project.

The negotiations leading to the JBNQA gave us a window to address our dreadful past.

We found that history will repeat itself unless we learn from it and change its path. So, we learned from our dreadful past to determine our collective vision that would guide us in our journey for social justice.

When seeking legal counsel to help us defend our land, rights and Eedouwun, a lawyer told me that we didn’t have a chance against three powerful giants such as the Government of Canada, Government of Quebec and Hydro-Québec. They had the human and financial resources to defend their interests and proceed with their plans for hydroelectric development in Eeyou Istchee.

Today we can look back and see what we achieved in challenging these giants over the past 50 years.

We know that after the announcement of the hydroelectric project in 1971:

1. We held the first Eeyou/Eenou Chiefs meeting to discuss and oppose the James Bay Project.

2. We became united in our opposition to the James Bay Project thus empowering ourselves.

3. We initiated court proceedings to protect our rights, land and Eeyou Eedouwun.

4. We achieved Judge Albert Malouf’s ruling which recognizes our rights, declared that the James Bay Project should stop, and forced the government to negotiate a settlement.

5. And we negotiated the terms and provisions of the JBNQA with our vision of Eeyou Eedouwun for the future.

I am proud of the achievements of Eeyou/Eenou of Eeyou Istchee over the past 50 years.

In particular, I want to stress the importance and significance of the Malouf judgment rendered on November 15, 1973, for achieving the JBNQA. Eeyou/Eenou of Eeyou Istchee had initiated court proceedings, in 1972, to stop the James Bay Project and defend our land, rights and Eedouwun.

The Eeyou/Eenou hunters, stewards (tallymen) and Elders played a vital role in the court proceedings that led to Malouf’s judgement. Their testimonies convinced Judge Malouf of the Eeyou/ Eenou use and occupation of Eeyou Istchee. And that our way of life, what we call Eeyou Eedouwin, is unique and vital to who we are, and that it was threatened by the damages that the hydro project would cause.

Judge Malouf in the Superior Court of Quebec recognized our apparent rights to our land and our distinctive way of life and ordered a stop in the construction of the James Bay Project. His judgment was the first explicit court recognition of Indigenous rights in the history of Canada. In addition, Judge Malouf had concluded that the lands of the Eeyou/Eenou and Inuit could not be developed without the prior agreement of the Eeyou/Eenou and Inuit. This decision marked a turning point in the

relations between the Eeyou/Eenou and the governments of Canada and Quebec.

A consequence of Malouf’s judgement was that Canada and Quebec decided they would negotiate with us after refusing to do so many times. Their change of the stance led to two years of intensive negotiations and to the signing of the JBNQA.

Throughout these challenges, the Eeyou/Eenou collective vision for social justice and inherent self-government with Eeyou Eedouwun was shared and supported, in unity, by the Chiefs, youth, Elders, men, women, hunters, stewards (tallymen) of Eeyou Istchee. During our deliberations the Eeyou/Eenou First Nations agreed to create a regional council, the Grand Council of the Cree (Eeyou Istchee), to help advance our collective vision.

Over the past 50 years, dramatic and drastic changes have happened to the Eeyou way of life, lands, resources and development, economies, health, education, communities, culture, governance, and relations with the outside world.

After centuries of denial of rights and exclusion from governance and decision-making regarding Eeyou, communities and lands and natural resources, the Eeyou of Eeyou Istchee, with the proper implementation of the JBNQA, are in the long process of rebuilding the Eeyou/ Eenou Nation.

In 1974, we were a population of 6,370 Eeyou/Eenou living in six isolated communities. In 2025, we are a population of about 21,000 Eeyou/Eenou living in nine communities

We have reclaimed our right to self-determination and self-government by killing the application of the Indian Act to us. Now we have local Cree First Nations Governments and the Cree Nation Government who exercise Eeyou governance without the control and interference of the federal government through the JBNQA.

We are exercising our rights to hunt, fish and trap without the legal impediments that existed before 1975. Hunters are receiving benefits such as the Cree Hunters Economic Security Program to help in the continuance of harvesting, hunting, and related activities. Before 1975, the only source of income that

Eeyou/Eenou hunters had was from the sales of fur.

Through the Cree School Board and the Cree Health Board, we are in control of health, social services, education and schools. In this regard, we have constructed new elementary and secondary schools in the communities, a new hospital in Chisasibi, and new modern clinics in the communities. In addition, we have changed the path of Cree education by providing it for our youth in their communities. By taking into account our language and culture in our schools instead of the pre-1975 policies of assimilation and cultural genocide administered by the Canadian government.

We have constructed four new Eeyou/Eenou communities – Chisasibi, Waswanipi, Nemaska and OujeBougoumou – so that each local Cree Nation has a village home. We have our own Eeyou/Eenou Police Force. We have substantially improved living conditions of Eeyou/Eenou of Eeyou Istchee through the construction of housing, streets, electricity, and water and sewage systems. We have improved access and transport throughout Eeyou Istchee with roads, airports, and cellphone and internet services in the communities.

In economic development, we have local and regional Eeyou/Eenou business enterprises such as motels, restaurants, gas stations, construction companies, and an airline. We have improved the employment status of Eeyou/Eenou who are employed by local and regional governments, Cree institutions such as the Cree School Board, the Cree Health Board, and Cree business enterprises.

We have established new and generally effective relationships with Quebec and Canada.

On the other hand, over the past 50 years, Eeyou of Eeyou Istchee have faced social, political, environmental, economic and other problems related to rapid development of natural resources in Eeyou Istchee. The JBNQA has contributed to opening the door to Eeyou Istchee and its natural resources. The construction of vast road networks has provided access to Eeyou Istchee and has resulted in an influx of outsiders, products, and proponents of natural resource developments. Such external encroachment disrupts the health of

Eeyou in the communities, the hunting territory system of Eeyou hunters, and the abundance and distribution of fish and wildlife.

Hydroelectric and commercial forestry development have eroded the land and resource base of Eeyou of Eeyou Istchee. Many families have felt a tremendous sense of loss over the past five decades as hydroelectric developments have resulted in impacts such as the displacement and relocation of communities, flooding of valuable hunting territories and burial grounds, loss of wildlife habitat, loss of major rivers, loss of fish and game, loss of drinking water, and loss of cultural and spiritual sites.

In addition, the vast clear-cutting activities of the forestry companies have resulted in a great loss of valuable Eeyou hunting territories and wildlife habitat. While there has been some employment for Eeyou/Eenou in hydroelectric and mineral development, Eeyou/Eenou need regulation and protection from these developments, and more benefits from natural resource development that Eeyou approve for Eeyou Istchee. There are many serious problems to solve as Eeyou of Eeyou Istchee seek to benefit from economic and resource development along with their desire to maintain key elements of their cultural heritage, homeland, way of life and Eeyou Eedouwun.

In summary, over the past 50 years, the rights and benefits of the JBNQA have been beneficial for Eeyou/Eenou, Eeyou Istchee and Eeyou Eedouwin in substantially achieving the collective vision of the people. The impacts of resource development such as hydroelectric and commercial forestry have been and continue to be devasting on Eeyou/Eenou. Eeyou Istchee and Eeyou Eedouwin.

We, Eeyou of Eeyou Istchee, have paid a tremendous price for the rights and benefits of the JBNQA. And yet we had to expend much human and financial resources for the proper implementation of our modern treaty.

In our journey over the past 50 years, we’ve faced our share of challenges, and come through them stronger as individuals, families, communities and as a people and a nation.

That’s because we have never let go of a belief that has guided us – our conviction that, together, we can change our world and Eeyou Istchee for a better present and a hopeful future.

Over the past 50 years, with a stronger feeling of who we are, we have restored our cultural integrity and historical identity. And we have restored our self-governing status. We are a nation and a people with a homeland rather than 10 separate bands and villages. We use the term “Eeyou/Eenou” to indicate how inland Eenou and coastal Eeyou people have come together.

In our understanding as one nation and one people, we have empowered ourselves to speak and act for ourselves in our contacts and relations with other peoples and governments. We have taken our rightful place in Canadian society as Eeyou/Eenou of Eeyou Istchee. In this manner, we will continue to protect our way of life in the traditional and wage economies, our land and Eeyou Eedouwun.

I thank the Eenou/Eenou Chiefs, negotiators, legal counsel, scientific and technical advisors, Eeyou/Eenou hunters, stewards (tallymen), youth, men, women, Elders and administrative and support staff for their valuable contributions in our journey for social justice over the past 50 years.

I want to end with a final thought and fact. Fifty years ago, the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement was signed. This means that one would have to be at least 68 years old to remember what went on 50 years ago. A substantial majority of the present Eeyou population is under the age of 68. I want to state to the Eeyou people of today especially to the present Eeyou Youth: Do not spoil what you presently have by desiring what you do not have but remember that what you now have were once the things Eeyou/Eenou of Eeyou Istchee of the 1970s only hoped for.

Meequetch! Thank you!

P hili P A wA shish wA s A negoti Ator And signAtory of the JAmes BAy And northern QueBec Agreement. he is Also A c ommissioner of the c ree / n A sk AP i commission.

by Bill Namagoose

This is my take on the 50th anniversary of the transformative James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement signed on November 11, 1975, and the Agreement in Principle signed in 1974 while I was still in school in Gatineau. The JBNQA became a treaty in 1982 with the adoption of the Canadian Constitution.

My piece is critical of the environmentalists and Indigenous leaders who were not politically supportive of the Cree’s decision and vision at that time.

The Cree Nation was led by brave leaders such as Grand Chief Billy Diamond, along with Chief Robert Kanatwat, Philip Awashish, Ted Moses, Smally Petwabano, Abel Kitchen, Chief Peter Gull, Chief Fred Blackned, Chief Joseph Petagamaskum, and Chief Bertie Whapachee, to name a few.

Many of the leaders were in their 20s when they signed. They were guided by their strong ties to their Cree culture, language and traditional way of life, and by their desire to improve the standard of living in Cree communities.

The political atmosphere in Canadian and Indian politics was intense. In 1969, the federal government published the

White Paper, a policy that would abolish Indian status and transfer its responsibilities over Indians to the provincial governments, thereby extinguishing Indigenous rights to land, resources and extinguish Indigenous rights to self-determination.

There are several takes on this historic land claim agreement, which Canada and Quebec later regretted signing. The two governments felt the Crees got too much and acted in the 1980s and 1990s to get the Crees to sign off and gut the Treaty and Constitutional status of the JBNQA. But the Crees insisted on full implementation and on maintaining the constitutional status.

In the early 1970s, Quebec premier Robert Bourassa sent bulldozers into Cree territory to build the world’s largest hydroelectric dam project as if we didn’t exist. The Cree Nation was dependent on the land as it practiced its traditional way of life by hunting, fishing and trapping. The Cree Nation strongly opposed the “Project of the Century” and began organizing to stop it.

They formed the Grand Council of the Crees after not getting satisfaction from the Indians of Quebec Association

(IQA), who they initially called upon to help stop the project.

The IQA had other ideas. They told the governments that they should first settle the land claims in southern Quebec and the St. Lawrence Seaway issue, and then they could discuss the Project of the Century.

When the Cree leaders found out about this double-dealing, they bolted from the IQA and formed the Grand Council of the Cree to deal exclusively with Canada and Quebec. Had we stayed with the IQA, we would still be waiting, as there were no land claims settled in the south, nor was the St. Lawrence Seaway.

The Cree Nation communities at that time were remote and traditional. Canada and Quebec were not very present in our lives.

Canada and Quebec thought they were getting a power project and settling a land claim referred to in the Boundary Extension Act of 1898 and 1912. These two acts “gave” land to the province of Quebec, which was previously identified as the Northwest Territories.

But that has always been Cree and Inuit land since time immemorial.

The Cree and Inuit, on the other hand, viewed it as an opportunity to design a framework for a relationship with Canada and Quebec that would ensure greater autonomy for themselves.

Bourassa had promised to modernize the Quebec economy with massive energy projects and sell the electricity to the United States. And the Cree and Inuit benefited from that leverage in their negotiations.

The IQA leaders called us sellouts when we left. Yet they were the ones who were going to sell us out after they had settled their own land claims in southern Quebec. Many Quebec Indigenous leaders still call us sellouts. They cannot point to our success, bravery and accomplishments over the past 50 years. They are still in and manage inadequate Indian Act programs.

We have developed our social and economic development institutions, but we still have many in need. We would have been in more serious economic and social decline had we followed the advice of many who were not from our society. We kept fighting.

The JBNQA is not perfect and has negatively affected our sovereignty and independence. But it is better to compromise and live to fight another day. Our

people do not aspire to a perfect world or to return to the way it was 400 years ago. They are realistic and prioritize the well-being of the individual Cree person over striving for perfection.

It never dawned on me that I would spend my career ensuring that Cree people receive the benefits as promised in the JBNQA, and to help stop reckless development of Cree lands and rivers.

I recall when the late Chief Robert Weistche from Waskaganish thought it would be a good idea to witness history in Montreal. We were still in school when we decided to hitchhike to Montreal and witness the signing of the Agreement in Principle. It took about seven hours to get to the hotel where the Cree were staying.

We told them we were there to witness the signing. They told us the signing was in Quebec City and not in Montreal. After a few choice words, we decided to stay in Montreal that night, even though we didn’t have any money or a place to stay.

Some girls took pity on us and agreed we could hang out with them in their room, since the people they were with were at the signing in Quebec City.

At about 2:30am, the hotel room door burst open, and a Chisasibi trapper stood

in the doorway telling us to get out. “Madji-wiwig!” he said forcefully.

We left in a hurry and ended up in the lobby. At around 3:00am, the hotel receptionist was looking at us, and we knew he was going to ask us to leave. It was then that I remembered my late uncle Angus Whiskeychan was usually a delegate. I went to the front desk and asked if he was registered in the hotel. Luckily, he was. I called and woke him up. He was not happy, but I told him we were in the lobby, had nowhere to sleep, and were broke. I asked if we could sleep in his room.

We got to his room, and he had only one bed. I wondered what he was going to decide. He pointed to the floor on the right side of his bed and said, “You, Robert, sleep there,” and then pointed to the floor on the left side and said, “You, Bill, sleep there.”

That historic night Robert and I slept on the bare floor of my late uncle’s hotel room.

It never dawned on us what the future held. We would both be elected as Chiefs in Waskaganish and participate in Cree Nation leadership.

You may be eligible for compensation. Help is a phone call away.

As part of the First Nations Child and Family Services and Jordan’s Principle Settlement, Caregiving Parents and Caregiving Grandparents of Removed Children are now able to submit a Claim for compensation. This includes the biological and adoptive parents, biological and adoptive grandparents and First Nations Stepparents of a First Nations Child who was removed from their home between April 1, 1991, and March 31, 2022, by Child Welfare Authorities.

You do not need to provide child welfare records or share your story to submit a Claim. And you do not have to work through the Claim Process alone. Free support is available.

Across the country, Claims Helpers are available to help at no cost. They are ready to support you in person, by phone or video call – in both English and French, and also in some Indigenous languages.

Most Claims Helpers are Indigenous and are connected to their communities. They are trained in cultural safety and can help you through your Claim at a pace that works for you.

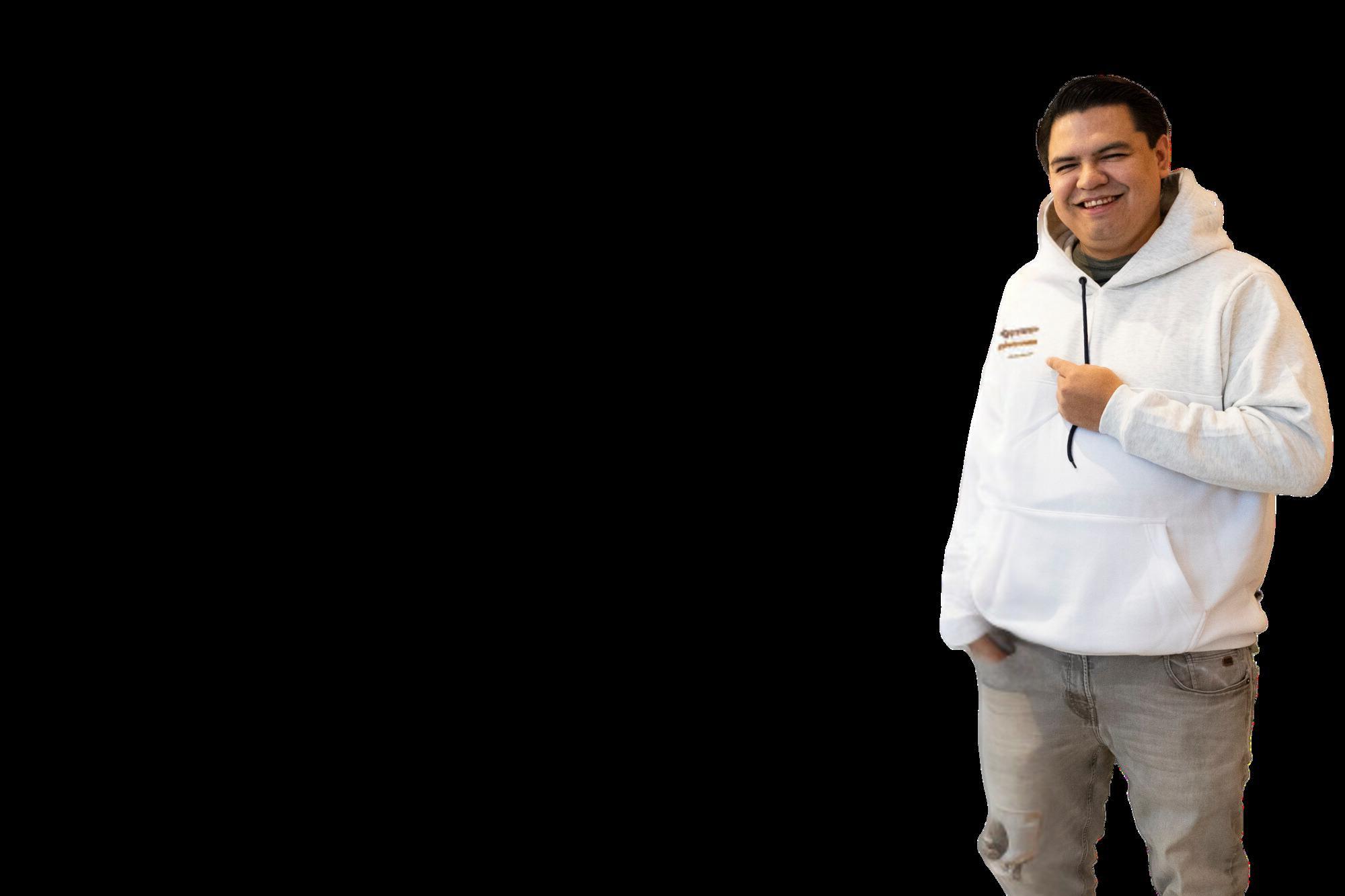

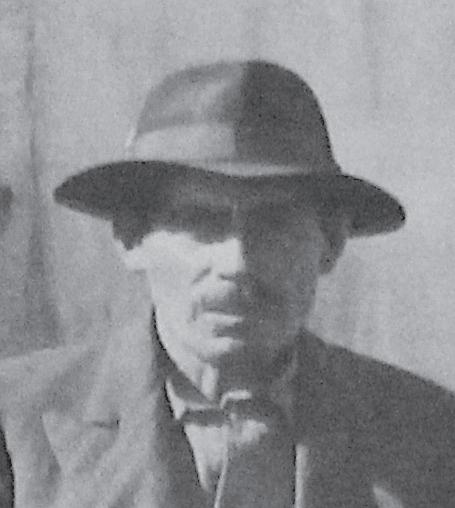

Buckley Petawabano remembered as a Cree

by Patrick Quinn, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

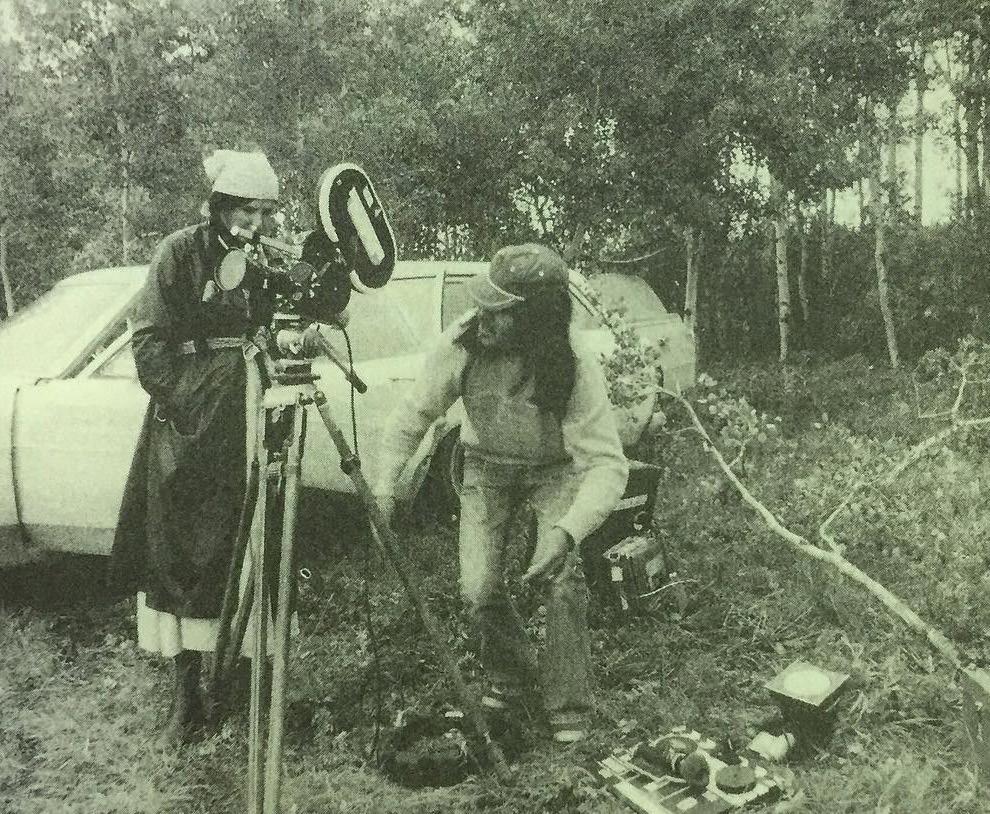

Buckley Petawabano, who passed away on October 19 at age 77, is being remembered as a trailblazing actor and Indigenous media visionary, who leveraged his early fame as a television star on the CBC series Adventures in Rainbow Country to uplift his Cree people.

Following influential acting roles in the 1970s, Petawabano stepped behind the camera as a cinematographer, paved the way for modern Indigenous broadcasting and dedicated himself to community service in Mistissini. The community held a farewell drive in his honour after the funeral to express their gratitude and respect.

"Buckley wasn’t just someone we saw on screen – he was one of us," said former Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come. "Buckley showed us that love for your people can guide a whole life. He opened the door for so many others, showing that we can be ourselves and believe we can achieve anything we want."

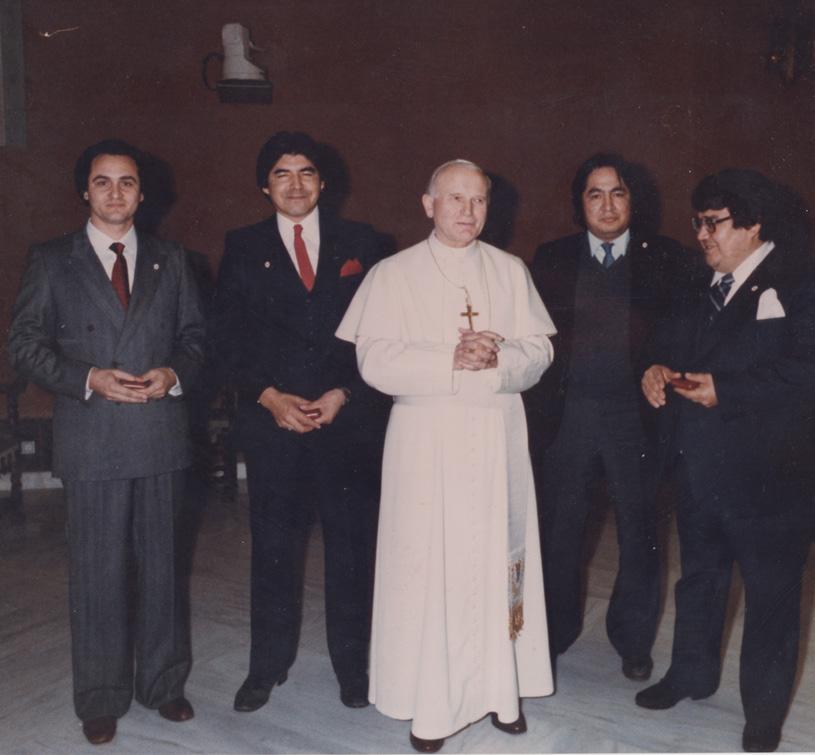

Alphelise Petawabano was born in a tent by Lake Mistassini in 1948 to Philip and Mary Petawabano, his father well known as a drum maker by the local hunters and tallymen. When meeting lifelong friend Philip Awashish at residential school in Moose Factory at age six, he introduced himself as Buckley and had his right arm in a sling to hide being left-handed.

When they moved to Sault Ste. Marie for high school, Awashish said they were so brainwashed by their education that they thought life in non-Native society was great. In 1967, Petawabano’s first acting experience was in a play writ-

ten by an Anglican minister portraying assimilation as beneficial, in which Billy Diamond even had a line saying, “The old Indian ways are gone.”

Enjoying their newfound freedom in the city, smoking and drinking cheap wine at the local pool hall, they started a social club for Indigenous students with Diamond MCing Friday night dances. Petawabano and Awashish started a band called Nature’s Children with other Cree students including Morley Loon, who later found fame as one of the first to popularize original songs in an Indigenous language.

Moving to Montreal after high school, Petawabano and Awashish rented an apartment together while taking courses at McGill University and mingling with young Indigenous activists. It was an era of profound social change and there was a growing awareness of Indigenous political issues.

"Buckley and I became more socially conscious," recalled Awashish. "We realized that Eenouch had a collective history with a dreadful past as an oppressed people in a similar way as other First Nations in Canada."

When the producers of a new CBC series asked about his plans in a Montreal

restaurant, Petawabano replied: “Take up anthropology to study the white man.” Realizing his natural charisma and convincing screen presence, Petawabano was immediately cast as Pete Gawa in Adventures in Rainbow Country, becoming the first Indigenous Canadian to star in a TV series.

When its 26 episodes started airing in 1970, the show and its stars became very popular. Petawabano received fan mail and enjoyed being stopped on the city streets. He bought himself a car and his father a snowmobile. Bringing reels of the show back to Mistissini, the entire community gathered to watch them together, teasing “You better not get a big head, Buck, or we’ll throw you in the lake.”

"I first saw Buckley on TV when we were at La Tuque Indian Residential School," said Coon Come. "We were so proud of him knowing he was from our community. We were his greatest fans. He didn’t do it for fame – he did it because he knew representation mattered."

After creative differences between the production company and the CBC limited the show to only one season, the broadcaster put its resources into The Beachcombers, which some accused of

being a Rainbow Country ripoff. In 2006, Petawabano attended a cast and crew reunion in Whitefish Falls, Ontario, where the show was shot.

In 1971, he was one of six Indigenous people chosen for a two-year filmmaking course at the National Film Board. Petawabano told the Montreal Gazette: “There are always a lot of films showing how poor Indians are... I’d like to make films about how happy they are, even on their modest means, about the beauty of Indian life.

Following a stint on stage in George Ryga’s play The Ecstasy of Rita Joe, Petawabano starred in Cold Journey,

a 1975 drama about a Cree boy torn between his family’s traditions and the residential school system, inspired by the tragic story of Chanie Wenjack. The film featured a supporting performance from his good friend Johnny Yesno.

"When he was shooting Rainbow Country, he would drive to Toronto and stay with us," said the late Yesno’s ex-wife, Delia Opekokew. "He was the best man at our wedding. It was an exciting time – he was kind, generous, lots of fun."

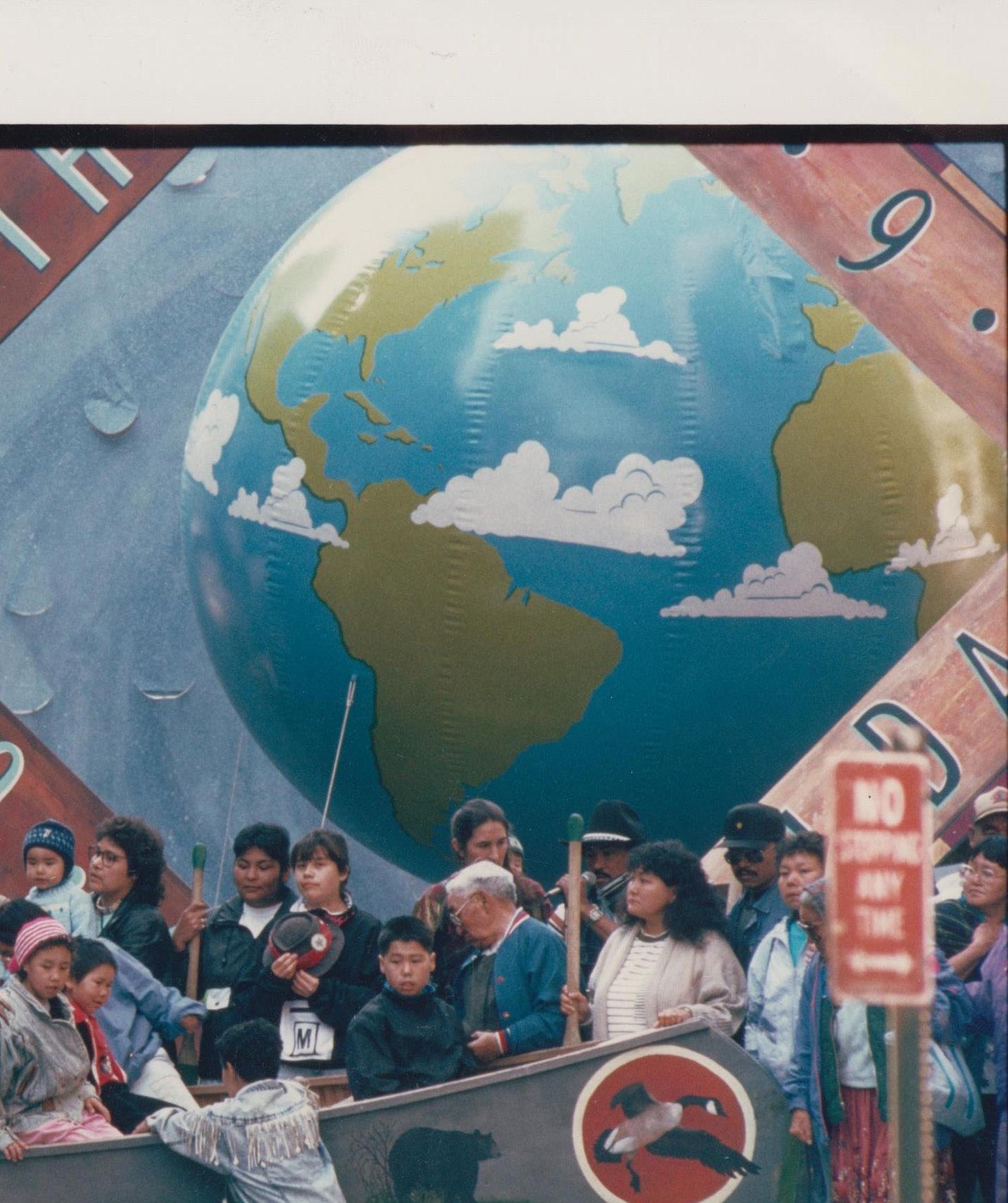

Petawabano had become increasingly political, helping to organize the nine-day James Bay Festival in Montreal

in 1973, galvanizing support for the Cree against hydroelectric development with legendary Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists including Joni Mitchell. His editing and cinematography of these concerts were seen in Alanis Obomsawin’s NFB documentary Amisk.

On August 18, 1973, Petawabano married Bella Moses, who was also involved in the Cree social justice movement. Supporting Awashish, Diamond and new brother-in-law Ted Moses, Petawabano became the “communications man”, filming negotiation meetings and gatherings for court cases. He was present for the signing of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement 50 years ago.

Petawabano’s proposals to the CRTC to encourage Indigenous broadcasting and exempt status to on-reserve radio stations were accepted, resulting in the James Bay Cree Communications Society, which has served Eeyou Istchee since 1981. Cinematography and production work continued as he became a mentor for the next generation.

"His knowledge was extensive, yet he made it look simple and accessible, and more than anything else enjoyable," said Urban Rez Productions co-founder and former student, Jeff Bear. "He dedicated many of his years to Cree stories. After anything serious, he would say, ‘On the side, of course.’"

A founding member of Eeyou Communications Network, Petawabano served several dedicated years on Mistissini’s band council. After a major stroke in 2008 left him paralyzed, he courageously maintained his loving relationships and delivered a moving speech when accepting the Cree Legend Award in 2013 from the Cree Native Arts and Crafts Association.

"We’re really proud of his legacy and have named an award after him recognizing artists in media," said CNACA executive director Dale Cooper.

Petawabano leaves behind daughters Tina, Lisa and Leslie Ann, several grandchildren and a great-grandchild. When Awashish arrived at the Chibougamau institution where he passed away, Bella told him, “Buckley has gone fishing, and he had not invited us.”

There is no such thing as a just or honourable war

by Xavier Kataquapit

As we prepare to honour November 11, Remembrance Day, I think about the destruction war has done to my James Bay Cree family and my partner Mike’s Irish Canadian family. When you are affected by the death, wounding or dramatization of family members, you realize how the terror of war continues to ripple through the generations.

There is no glamour, no justice and no sense to any war ever fought that I can understand. In the First World War, a recruiter made his way by canoe all the way to Attawapiskat in 1916 and coerced a group of 22 young Cree men. He took them by canoe south where these men ended up on a train which travelled to points further south, to army training and then they were shipped off from Halifax to England.

Attawapiskat is a remote First Nation these days, so can you imagine how remote it was in 1916. None of these Cree boys had any idea where they were going, no concept of the world outside of their traditional lands and they could not speak English. Many made it back, but they were changed forever and my great-grandfather John Chookomolin, from my mother’s family, never did return. My family didn’t find out what happened to him until the 1980s.

My grandfather James Kataquapit, on my father’s side, returned but the experience had changed him. My dad Marius and Elders always reminded me never to trust the military when they want to take our young people. Today I see evidence of the militarization of our First Nations and it worries me. You can read my grandfather’s war stories at www.nativeveterans.com

My partner Mike’s dad James was wounded and suffered from shell shock in the Second World War and had a terrible sad life. James’ brother Patrick, who was only a teen, was killed in action on the same day James was wounded in October 1944. They had both fought in the infamous Canadian-led Battle of the Scheldt in Belgium. These tragedies

still reverberate today through the new generations.

When we discovered these facts, their stories drew us into a lot of research on war. We were shocked to find so much information on how these wars developed. The propaganda around war and convincing populations to support war are full of lies. War is always about money and power, and governments always lie about why we have to send our young people off to die and suffer. Really wealthy people or their families rarely go to war.

Communism and socialism were not dirty words in the early 20th century. In fact, academics, many scientists, artists and authors considered a world of socialist ideals of sharing the wealth, labour unions and free thinking was a good thing. The problem then, as it is now, is that the small group of rich corporate heads did not want to share their wealth. These groups supported fascist organizations, funded them and put them into power in Spain, Portugal, Italy, Germany and many other countries.

The idea was to stop the world from considering fair and just environments that would infringe on the bottom line of the wealthy. It worked to a great degree with the killing of labour organizers and union members, socialist leaning academics who were well represented by the Jewish communities and anyone who was different. These evil kingpins were responsible for the destruction of many wonderful cities in Europe and around the world. Millions died, were injured and left impoverished by these wars.

Fascism was being promoted by wealthy right-wingers with movements in Europe, the United Kingdom, the United States and right here in Canada.

So, when we stand to honour and remember those who fell and who were injured and terrorized by war this November 11 take a realistic and honest view of why wars happen. Right now, we have wars in the Middle East and Ukraine which are buried in all kinds of propaganda. The only thing we must remember is that war is always about money and who benefits from war.

An example of how far-right ideals have often been supported is demonstrated by how at the end of the Second World War, it was far too easy for Nazi, fascists and far-right extremists to enter Canada after having fought against our troops. The Deschênes Commission, officially known as the Commission of Inquiry on War Criminals in Canada, was set up in 1985 to investigate claims that Canada was a haven for Nazi war criminals. This led to some prosecutions, but the list of these people has never been fully released. Even after continued calls to do so after many decades, the Canadian government still refuses to release the full report.

In the US, they carried out Operation Paperclip to actively bring former Nazi scientists and professionals to America, many of whom were war criminals and active participants in the Nazi war machine.

We have to do our best to see past the lies of war. There is no such thing as a just or honourable war.