Natasha Yaworsky // Holst Housing Seminar // Fall 2021 // Dave Otte & Renee Strand

Natasha Yaworsky // Holst Housing Seminar // Fall 2021 // Dave Otte & Renee Strand

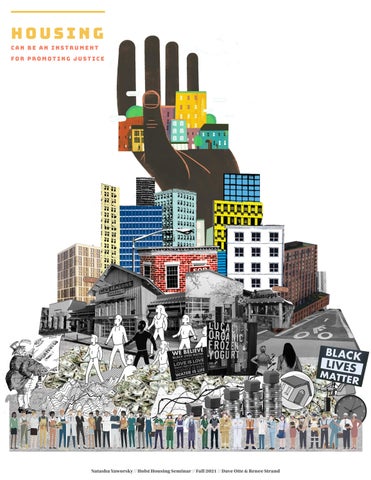

Housing can be an instrument for promoting justice

Natasha Yaworsky // Holst Housing Seminar // Fall 2021 // Dave Otte & Renee Strand

Natasha Yaworsky // Holst Housing Seminar // Fall 2021 // Dave Otte & Renee Strand

Housing can be an instrument for promoting justice

5Gentrification has quickly become a serious urban issue, one that is widespread across multiple cities around the globe. Government and philanthropic efforts to prevent or ameliorate displacement of marginalized individuals from their communities have increased over the past few years as revitalization efforts continue to produce unaffordable housing markets. Affordable housing action and homeownership assistance initiatives have been relatively successful in promoting such justice in neighborhoods experiencing gentrification, however certain aspects of housing often result in these efforts falling short of the target. Once the shortcomings associated with anti-displacement efforts are addressed, architects can implement more effective and thoughtful solutions into affordable housing initiatives. This is how housing can be an instrument of justice and equity while still creating desirable and successful neighborhoods. This leads to the question: what are the issues associated with affordable housing that are allowing the negative impacts of gentrification to continue, and in what ways can architects confront these issues through design?

This paper outlines two different scale issues when answering this question. The first issue examines what happens in a gentrified neighborhood when affordable housing is developed, and how housing must provide community support as well as reducedcost shelter in order to promote equity. The second part of this paper identifies a broader issue associated with housing, discussing how the American economy and market tend to perpetuate the negative impacts of gentrification. The solutions to this issue are therefore more policy-driven and progressive, however these proposals offer intriguing methods for architects and their collaborators to implement in developments aiming to promote justice.

How can affordable housing perpetuate inequity?

How can housing economics perpetuate inequity?

Affordable housing efforts have worked hard to try and mitigate displacement in neighborhoods around the world. Many developments and city effor ts have worked to provide affordable housing oppor tunities through mixed market rate and affordable units, by allowing current residents to preference for new affordable units, and through other policies that aim to increase housing stability for residents and mitigate the impacts of gentrification (Chapple & Loukaitou-Sideris). These methods are diverse and range in their successes, and although no effort can ever be perfect, affordable housing efforts can often become a tokenistic box to check off a list. The issue with housing action is that it can act as a band-aid that does not always address the actual damage that has been caused. Are these communities still put at a disadvantage even when housing is provided and they’re not displaced? Even as affordable housing gets developed in neighborhoods such as Albina, what would the community look like for those who are able to stay? Affordable housing initiatives by themselves won’t provide the restitutions necessary to support marginalized communities:

“If there aren’t enough Black people li ving in Albina, then Black community institutions and businesses can’t make a go of it. But the opposite is true too: if there is not a critical mass of identifiably Black-owned and Black-run cultural and social institutions in the neighborhood, then African American People don’t have much reason to live here” (Hern ch. 5) .

Housing action attempts to mitigate gentrifica tion with affordable units for residents at risk of displacement. However, if community institutions aren’t supported as well, a community cannot stay affordable and comfortable for its residents. This results in continued displacement of marginalized communities- even if there is available affordab le housing, there is little reason to stay in a nei ghborhood made up of Natural Grocers, organic pet stores, and boutique coffee shops. It is at this point that affordable housing becomes a band-aid solution, where one major underlying cause for displacement - economic support- is not being ad dressed. Architects need to address more than just housing needs when fighting displacement. Once marginalized residents are able to share the growth and prosperities of revitalization efforts, then the “desirable neighborhood”: one with the pedestrian/ bike friendly streets, mixed use buildings, and lively realms, can become fully realized and appreciated.

Which leads to the question, how can architects help in providing both housing action and economic support? The affordable housing formula seems to be on a steady and effective path. The next step is working with these communities to ensure continued economic sustainability as inevitable new develop ment comes to a neighborhood. Much of this means embedding concepts of community benefits into de sign and partnering with local institutions. There are a variety of approaches already being taken by desig ners trying to incorporate equity into design, some of which will be explored in the following case studies.

One step to make toward a goal of in creasing economic stability among those at risk of displacement is increasing equi ty within the building profession itself- “If you don’t really have a team that unders tands all the users and all the diversity within each community, then you are not going to create something that is truly in clusive of everybody who will use the spa ce.” (Melton).

This is what BORA architects in Portland, Oregon have aimed to do throu gh their Young Black Professionals Work force Housing project. The partnership with Self Enhancement Inc. and Andersen Construction will provide stable housing for young peoples of color interested in a career in the building industry, however the initiative intends to invest in the Bla ck community through something more than just housing. Residents selected for the program will take part in a three year Professional Apprenticeship Program in construction management, architectu re, or engineering that will provide men torship, leadership skills, and jobs with a local AEC firm. Through this program, communities at risk of displacement can be impacted by professionals who come from a similar background, allowing for more positive and thoughtful design deci sions to be made. More than that, the pro gram works to support economic growth of marginalized peoples by creating ways to gain wealth.

As stated in AIA Oregon’s Digital Design Series article, “In isolation, a building pro ject does very little to address the issue of wealth disparity; the YBP Workforce Hou sing strives to do much more,” as it aims to boost economic stability among commu nities at risk of displacement rather than only supply an affordable unit. By working to promote wealth among communities at risk of displacement and inviting them into the professions that can make an im pact on anti-gentrification efforts, the YPB program is one example of transforming housing projects from only an affordable unit into an instrument of promoting jus tice.

This mixed use development in Seattle emerged as an effort to prevent not only re sidential, but also commercial and cultural displacement in the diverse and low-income neighborhood of Othello. It provides housing action through affordable units for families below 80% of the AMI; specifically designed units to accommodate the multigenerational families already in the area; and gives low-in come owners the opportunity to purchase uni ts at low market rates then re-sell with limited profits (Melton). However, the community-led project goes beyond housing. Made up of mul tiple buildings, Othello Square offers a host of resources aimed at stabilizing communities who are at risk of displacement. This includes a children’s clinic, a childcare center, a high school, and commercial space that aims to “in crease access to economic opportunity, STEM education, small business incubation, cultural celebration and preservation, and financial services” (HomeSight, Othello Square). By in cluding space for small businesses, education, and culture, Othello Square is another example of how affordable housing projects can act as an instrument of justice.

Located in Northeast Portland’s Humboldt neighborhood, the LEED Gold-certified Humboldt Gardens project includes a mixed-use building and townhomes with a variety of housing options. In regard to affordability, the project houses those with less than 60% of the AMI through one to four bedroom units. However, the project strives to provide more than housing for residents in the historically displaced neighborhood through a few different strategies. First, the residents who qualify for the subsidized housing are to participate in the GOALS program. This Homeforward program offers supportive services such as job training, building savings, homeownership help, and re pairing credit among other things (HomeForward, GOALS Pro gram). Overall, the main purpose of GOALS is to help participan ts establish financial independence and self-sufficiency.

The next action that Humboldt Gardens takes to increase the economic stability of marginalized communities is by housing the Albina Head Start Center. This program is extended to fami lies that meet certain low-income guidelines and offers health, nutrition, social, and childhood education services. In partne ring with this nonprofit organization and designing space for their program alongside affordable housing, the project enri ches the development of economically disadvantaged children. And by promoting the social and economic welfare of children and their families, Albina Head Start and Humboldt Gardens work towards closing the achievement gap among marginalized communities. One other program included in the housing ini tiative is the Bridges to Housing model, which offers affordable housing and intensive case management to houseless families facing obstacles in their path to economic stability (Kinshella). Twenty units in the development will be provided permanently for this model.

In addition to these two programs, Humboldt Gardens in cludes a small park, a community center, a computer lab, re tail space, a Community Policing office, and a Neighborhood Networking office. Moreover, other economic stability initiati ves were offered before the project was even completed: “40% of all work was completed by Disadvantaged, Minority, Women or Emerging Small Businesses as certified by the state. In addi tion, over 58% of all hours worked on site were completed by women and minority workers.” (Humboldt Gardens: Creating New Opportunities ). On top of this, a few projects on site crea ted opportunities for youth to be involved in construction trades. This includes a team from the Portland YouthBuilders framing one of the buildings, as well as a pre-apprenticeship opportunity for ten Jefferson High School students to work alongside con tractors.

All together, Humboldt Gardens sets a remarkable precedent of how “desirable” communities- those with bike lanes, proxi mity to public transit, quality schools, green space, mixed-use realms, and lively public realms can still be achieved while still working to boost the lives of those who have been displaced by these designs in the past. The extensive community partnerships within the project aim to enhance the stability of disadvantaged families so that they have both a reason and an ability to stay in their community in the wake of gentrification.

Architect MWA Architects Partnerships Construction Forward Iris Court ResidentsIris Court residents and other community members joined HAP and its project partners to help design Humboldt Gardens – a mix of 100 units of public housing and 30 units of moderate income affordable housing.

Jackson Construction

Head Start

Housing and Community Development

One major obstacle that is often examined when attempting to repair displaced commu nities is the topic of homeownership. It makes sense when looking at statistics: renters are about two times more likely to be displaced by gentrification than homeowners, as “Owners have more money and more equity in their ho mes. Their costs are locked in and do not rise like rents do. Homeowners also tend to be ol der and more attached to the neighborhoods they live in” (Florida). Homeownership is seen as one of the most successful ways to build wealth. This sentiment exists for good reasonhomeownership builds equity, comes with tax benefits, and allows for a stable mortgage payment. Combined with the likely apprecia tion of a home’s value, it then makes sense why many affordable housing and anti-gentrifica tion strategies focus on increasing homeow nership among disadvantaged communities. However, flaws within the market not only bring up issues in these models but also help empower the continuation of gentrification as it pushes land value out of reach to even the average wage owner.

Housing action can provide low-income families with affordable options, but these options are often temporary. Some affordable housing projects and their units can return to market-rate after a certain period of time. For example, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program established in the early 1990s offered tax credits if developers included below-market units in their projects that remained affordable for a minimum of thirty years. This means that in Oregon, about 4,189 affordable units will be lost by 2030 as these agreements come to an end (Ellis). In addition to this, homeowner ship assistance can often be just as temporary: “once a household is no longer eligible to recei ve rental subsidies, or a family sells the home it purchased with down-payment assistance, the housing unit they formerly occupied goes ri ght back to being market-rate—in other words, unaffordable” (Schneider).

Moreover, the characteristics of today’s market and commodification of land con tributes to a perpetual cycle of inequity as only a portion of a city’s population benefits from it’s collective achievement. Within the housing market, homes gain value as the nei ghborhoods around them become more at tractive. Better schools, bike lanes, mixed use buildings, and green spaces, among other thin gs, can cause the price of a home to skyrocket.

The problem with this is that this appreciation isn’t earned solely by the homeowner, yet they still acquire an exorbitantly disproportionate reward by simply holding onto their property.

As Matt Hern discusses in his book What a City

is For: Remaking the Politics of Displacement, one of his peers bought a house in Vancouver (one of the world’s least affordable housing markets) for $200,000 fifteen years ago. At the time of the book’s publishing in 2016, it was then worth 1.2 million. Hern discusses how this friend did nothing notable to earn such an increase in property value, and how the achievement of Vancouver is what caused this rise in value. The city of Vancouver, like Portland, became attrac tive for a multitude of reasons, and “if the city is a collective achievement, all the people con tributed: nurses, firefighters, people who clean the streets” (Korfhage). Yet not all of the people profit from this collective achievement- only those who own property do. Citizens invested their tax dollars to improve their city’s and its struggling neighborhoods, and now a majority of them can’t afford to live there anymore. Why should only some residents of a city profit from its success, when the rest of the population who contributed to it get left behind?

In short, the housing market promotes con tinued inequity as it rewards those who have the means to purchase property for the achie vements of entire communities. It also encou rages land to be viewed as nothing more than property to be acquired and unproductively sat on in anticipation of value appreciation. This in turn promotes gentrification as privileged individuals are able to speculate and purcha se land in “blighted” communities, wait for the neighborhood to transform as a result of the collective achievement of a city’s residen ts, then profit excessively from sale for deve lopment or ability to increase prices for rental of their property. In addition to this, even if a low-income family already owns a home in this community, the exorbitant price inflation of their property is enough to convince anyone to sell, profit, and move somewhere else- another continuation of displacement.

It is through the housing market’s effect on land value that privileged populations are able to continue building their wealth off of the ba cks of marginalized populations, drive them out of the communities they established, and therefore perpetuate gentrification. This leads to the question, how can housing better ad dress an inequitable market? In order to fight gentrification, architects must consider how the housing market is currently promoting it. In doing so, designers can develop creative housing models that challenge market forces and the ever-growing inflation of unearned land value. Then, these alternatives to property ownership can be implemented as a strategy to oppose displacement and create more equitab le wealth-building opportunities for disadvan taged communities.

It’s a big statement to point at a multifaceted economic system and blame the layered problem of displacement on it. Of course there are many factors contributing to the continued displacement and discrimi nation seen within many cities today. There’s also the fact that one can not simply change the housing market. However, it’s necessary to outli ne specifically in what ways property ownership can be reimagined as something other than a commodity to bolsters one’s own wealth. How can the market be refused in a way that benefits all who contributed towards the success of a neighborhood, rather than just those who own property? Can cities and designers create space outside of the housing market, where exorbitant land appreciation is mitigated and collective achievement is recognized? More importantly, how can architects tackle such an intimidating proposal for change? In order for designers to be able to tackle issues associated with ownership and gentrification, they must use housing projects to actively fight against the market. There is a long list of alternative homeownership models and projects that aim to do exactly this- some more radical than others- and only a sample of them will be broadly outlined below. However, each of the concepts dis cussed offer captivating glances of how housing can be an instrument for promoting justice through reconstructed ownership models.

Shared-equity homeownership models aim to ensure that housing remains affordable in perpetuity and allow low to moderate income fa milies to build equity- even as housing markets strengthen and a nei ghborhood’s desirability increases in the wake of gentrification. Shared Equity Homeownership programs establish the grounds for a perma nent and self-sustaining equity builder outside of the inequitable, tradi tional housing market. The model “takes a one-time public investment to make a home affordable for a lower-income family and then restricts the home’s sale price each time it is sold to keep it affordable for sub sequent low-income families who purchase the home”(Grounded Solu tions Network, Shared Equity Homeownership). Although no program is perfect, they provide at least one strategy to help disadvantaged families build wealth and continue to be a part of the communities that they contributed so much to. In addition, these programs combat the hou sing market’s system of disproportionately rewarding a singular proper ty owner for the investments of a community.

A Community Land Trust is a nonprofit organization that owns and acts as stewards of land. With one-time public or private investment, the CLT is able to build or buy homes and then sell to a low-income buyer. In exchange for the affordable price, they agree to sell the home at an affordable price to the next low-income buyer (Grounded Solutions Ne twork, Community Land Trusts).

In Limited Equity Cooperatives, government assistance such as sub sidies for construction and low-interest financing establish a project where “residents purchase a share in a development (rather than an in dividual unit) and commit to resell their share at a price determined by formula” (Local Housing Solutions, Deed Restricted Homeownership).

Deed Restricted Homeownership aims to preserve unit prices that were reduced through federal or nonprofit subsidies, inclusionary zo ning, or other affordability initiatives. Like other Share Equity models, deed restrictions limits how much buyers can gain financially on the appreciation of a home or unit price (Local Housing Solutions, Deed Restricted Homeownership).

An alternative method of refusing the hou sing market is through taxes. To reiterate, land gains value by passively sitting and by the collective achievement of a city’s residen ts. This encourages landowners to leave their land empty as its value is increased by a city’s growth, and allows them to achieve large profit margins with very little effort (and often off of the backs of those less privileged than them . If land was taxed, the federal resources collected from said taxes could then be poured back into the city- including contributing to affordable housing projects- and benefit the working class residents who helped the land gain value in the first place. A land tax would not only provide the necessary award for the collective achieve ment of a city. It would also discourage hou sing speculation and therefore help alleviate the steadily increasing inflation of land prices. This in turn allows low-income families to be come homeowners in their communities and better resist gentrification, encouraging fami lies to build wealth without disproportionately profiting from extortionate value increases and contribute to a neighborhood’s gentrification.

“About Us: Albina Head Start & Early Head Start.” Albina Head Start, https://www.albinahs.org/about-us.

Bates, Lisa K., “Gentrification and Displacement Study: Implementing an Equitable Inclusive Development Strategy in the Context of Gentrification” (2013). Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations.

Chapple, Karren, and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris. White Paper on Anti-Displacement Strategy Effectiveness. “Commu nity Land Trusts.” Grounded Solutions Network, https://groundedsolutions.org/strengthening-neighborhoods/ community-land-trusts.

Condon, Patrick. “A Tax That Would Solve the Housing Crisis.” The Tyee, The Tyee, 4 June 2018, https://thetyee.ca/Solu tions/2018/06/04/Tax-To-Solve-Housing-Crisis/.

Condon, Patrick. “How Vienna Cracked the Case of Housing Affordability.” The Tyee, The Tyee, 6 June 2018, https://the tyee.ca/Solutions/2018/06/06/Vienna-Housing-Affordability-Case-Cracked/.

“Deed-Restricted Homeownership.” Local Housing Solutions, 16 June 2021, https://localhousingsolutions.org/hous ing-policy-library/deed-restricted-homeownership/.

“Digital Design Series - InProcess.” AIA Oregon, https://www.aiaoregon.org/events/2021/9/15/digital-design-series-in process.

Ellis, Rebecca. “A Portland Suburb Is Poised to Lose One-Fifth of Its Affordable Housing. Experts Say It’s the Tip of the Iceberg.” Opb, OPB, 15 June 2021, https://www.opb.org/article/2021/06/15/tigard-oregon-poised-to-lose-onefifth-of-its-affordable-housing/.

Florida, Richard. Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 24 Jan. 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-24/prop erty-taxes-do-not-make-people-leave-neighborhoods.

“GOALS Program.” More Resources for You | Home Forward, http://www.homeforward.org/residents/section-8-hand book/more-resources-for-you.

Hern, Matt. What a City Is for: Remaking the Politics of Displacement. Kindle ed., MIT Press, 2017.

“Humboldt Gardens Mixed-Use Development.” MWA Architects, 2 Mar. 2021, https://www.mwaarchitects.com/work/ humboldt-gardens-mixed-use-development/.

“Humboldt Gardens- Creating New Opportunities.” HomeForward, http://homeforward.org/sites/default/files/HG-project summarysheets.pdf.

“Humboldt Gardens.” Home Forward, http://www.homeforward.org/development/property-developments/humboldt-gar dens.

Kinshella, Matt. “Bridges to Housing Selected as ‘Promising Practice.’” Neighborhood Partnerships, 24 May 2012, https:// neighborhoodpartnerships.org/2012/05/24/bridges-to-housing-selected-as-promising-practice/.

Korfhage, Matthew. “North Portland’s Albina Neighborhood Is the Focus of New Book about Gentrification.” Willamette Week, 22 Nov. 2016, https://www.wweek.com/arts/books/2016/11/22/north-portlands-albina-neighborhood-is-the-focusof-new-book-about-gentrification/.

“Limited Equity Cooperatives.” Local Housing Solutions, 21 May 2021, https://localhousingsolutions.org/housing-poli cy-library/limited-equity-cooperatives/.

Melton, Paula. “Equity in Design and Construction: Seven Case Studies.” BuildingGreen, BuildingGreen, 1 June 2020, https://www.buildinggreen.com/feature/equity-design-and-construction-seven-case-studies.

Melton, Paula. “Re-Forming the Building Industry: Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion.” BuildingGreen, 1 June 2020, https:// www.buildinggreen.com/feature/re-forming-building-industry-equity-diversity-and-inclusion.

“Othello Square.” HomeSight, 14 July 2021, https://www.homesightwa.org/othello-square/.

“Othello Square.” SKL Architects, 16 July 2020, https://sklarchitects.com/portfolio_page/othello_square/.

Schneider, Benjamin. “Shared Equity Homeownership.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 29 Apr. 2019, https://www.bloomb erg.com/news/articles/2019-04-29/alternative-homeownership-land-trusts-and-co-ops.

“Shared Equity Homeownership.” Grounded Solutions Network, https://groundedsolutions.org/strengthening-neighbor hoods/shared-equity-homeownership.

Thompson, Weber. “Othello Square Master Plan.” Issuu, 25 Apr. 2018, https://issuu.com/weberthompson/docs/othel lo_square_master_plan_180425_4.

“Young Black Professionals Workforce Housing.” Bora, 29 Sept. 2021, https://bora.co/project/young-black-profession als-workforce-housing/#!