The Voices of Jon Fosse

A Critical Study

Edited by Trond Haugen and Marius Wulfsberg

A Critical Study

Edited by Trond Haugen and Marius Wulfsberg

1400–1700:

tekst, visualitet og materialitet

Bente Lavold og John Ødemark (red.)

Edited by Trond Haugen and Marius Wulfsberg

National Library of Norway, Oslo 2025

1 Introduction: Voicing Fosse. The Life, Works and Criticism of Jon Fosse 11

Trond Haugen and Marius Wulfsberg

2 A Unity, However Hidden: On the Origins and Promise of 30 Jon Fosse’s Essays

Arild Linneberg

3 Writing as Insight: On Gnosis and “Shining darkness”, with Emphasis 51 on Septology

Tom Egil Hverven

4 Between Rural Men: Anxiety and Homosocial Bonds in Jon Fosse’s 83 Boathouse and Septology

Christine Hamm

5 Sounding German: An Exploration of Linguistic Devices in Trilogien 106 versus Trilogie

Rebecca Boxler Ødegaard

6 The Wonder of Literature: On Rhythm, Narration and the Question of 138 “What” in Jon Fosse’s A Shining

Marius Wulfsberg

7 Jon Fosse Emerges through the Director’s Archives – An Essay 170

Kai Johnsen

8 Manipulative Desire: A Reading of Someone is Going to Come 196

Frode Helmich Pedersen

9 La voix de l’ecriture: The Story of an International Breakthrough 226 Trond Haugen

10 Metaphysics in the Everyday: Drama by Jon Fosse with Emphasis on

I Am the Wind

Drude von der Fehr

11 Jon Fosse and the Festival System: New Perspectives on the 280 Playwright’s Success on the Global Stage

Jens-Morten Hanssen

12 He and She out into the World: An Introduction to the Jon Fosse 302 Archive at The National Library of Norway

Benedikte Berntzen

In 2021, the National Library of Norway received the Fosse Archive from its previous custodian, Nynorsk Kultursentrum (Centre for Norwegian Language and Literature). The acquisition of this archive was a key motivation for a seminar hosted by the National Library in September 2023 as part of the International Fosse Festival at Oslo Nye Teater. Titled Literature, Theatre – A Seminar on Jon Fosse’s Authorship, the event focused on Fosse’s novels and dramas, highlighting their vital contributions to contemporary literary prose and theatre. One month later, Jon Fosse was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Voices of Jon Fosse offers an academic response to this significant moment. Most chapters in this volume originate from presentations given at the seminar, which have since been revised and expanded into scholarly essays. We are pleased that Benedikte Berntzen, Drude von der Fehr, Christine Hamm, Jens-Morten Hanssen, Trond Haugen, Tom Egil Hverven, Kai Johnsen, and Marius Wulfsberg have chosen to publish their contributions in this collection.

A few additional chapters have been included following the seminar. Special thanks go to Frode Helmich Pedersen for “Manipulative Desire”, a chapter based on a lecture delivered at the symposium The Big Soaring at Litteraturhuset (The House of Literature) in Bergen on 1 June 2023, to Rebecca Boxler Ødegaard for her study of Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel’s translations of Jon Fosse into German, and to Arild Linneberg for his new study on Fosse’s literary-theoretical essays. We are also grateful for the enthusiasm and rigorous reviews provided by several anonymous peers.

When we began work on this volume in the autumn of 2023, following the announcement that the Swedish Academy had awarded Jon Fosse the Nobel Prize in Literature, we did so with a deep sense of purpose and the conviction that his authorship merits sustained scholarly attention. We knew that this view was shared by many within both the Norwegian and international literary communities. Over time, however, the project took on an additional dimension – one that, with a playful nod to Friedrich Nietzsche, we might call the joyful science . The process became infused with the pleasure of reading, writing, interpreting, and analysing a literature that continuously invites reflection on what literature may be.

Trond Haugen

and

Marius Wulfsberg

Oslo, 3 June 2025

1. Introduction: Voicing Fosse. The Life, Works and Criticism of Jon Fosse

Trond Haugen and Marius Wulfsberg

Since the 1980s, Jon Fosse has been one of Norway’s most challenging, intriguing, and influential authors. Alongside a select group of writers, he helped shape a new form of Norwegian literature. In dialogue with European modernism and contemporary theory, he pushed the boundaries of what literature and writing can be. Over the years, his authorship has evolved from prose and poetry into drama, reaching an ever-growing audience in Norway and internationally. In October 2023, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his ability to “give voice to the unsayable” (NobelPrize.org.).

But what is it about these texts – written in Nynorsk (New Norwegian) – filled with repetition, composed of either strikingly short or endlessly long sentences, marked by unusual punctuation, and at times formulated in ways that make us wonder whether meaning lies in the word’s definition or whether the words themselves carry a material presence that unsettles our capacity to read, feel, and understand? His writing seems to move toward a voice resonating from a place where words have not yet – or no longer – assumed their conventional meanings. What, then, creates the singular quality of Jon Fosse’s writing? And how might we, as readers, even begin to analyse his texts?

The Voices of Jon Fosse offers a series of responses to the question: What constitutes the distinctive qualities of Jon Fosse’s literature?

This introduction offers a brief survey of his biography, an

overview of the literary criticism and scholarly reception of his work, and a presentation of the volume’s outline.1

Jon Olav Fosse was born on 29 September 1959 in Haugesund, a city on Norway’s west coast. However, he grew up in the hamlet of Fosse, part of the village Strandebarm in Hardanger – a place where “the houses lie not far from the foreshore, the waves, the wooden boats, the jetty, and the row of boathouses. Across the fjord rise snow-covered peaks, Gygrastol, Melderskin, and Folgefonna, cloaked in an icy blue. At its deepest, the fjord plunges to 800 meters” (Seiness 2009, 22). 2

Fosse’s childhood home was a smallholding whose houses were built with money earned from transporting the dried fish known as clipfish or bacalao across the world. Fosse’s great-grandfather was a skipper, but after his ship was wrecked, he lived off his savings. His father managed the local Strandebarm Co-Op grocery store, while his mother was a housewife.

Jon Olav Fosse is the oldest of three siblings. He was named after his grandfather and his grandfather’s brother, but later, after becoming a writer, he began using only the name Jon. At the age of twelve, Fosse began playing the guitar. His first instrument was red and black, and from that moment on, he gave up everything else to play. His first band was called Lucifer Green; later, he became the thin,

1 The presentation of Jon Fosse’s writings and their scholarly reception is based on the Fosse bibliography at the National Library of Norway (www.nb.no/bibliografi/fosse/), as well as the Bibliografi for norsk litteraturforsking (Bibliography of Norwegian Research in Literature , www.nb.no/bibliografi/littforsk/) and the former database of Norwegian Journal Articles (NORART, www.nb.no/bibliografi/norart/), which was discontinued in 2022. The Fosse bibliography went online in the autumn of 2021 and is continuously updated. It includes references to Fosse’s works in their original language and in translation, journal articles and book chapters, theatre manuscripts, theatre programs, adaptations based on his works, as well as his translations and reworkings of other authors’ texts. Additionally, it contains reviews of Fosse’s works published in daily newspapers. The list of references in this introduction is not exhaustive but is limited to the works and articles specifically mentioned here.

2 This short biographical sketch of Fosse’s youth is based on Cecilie Seiness’s book Jon Fosse. Poet på Guds jord (2009).

long-haired guitarist in Rocking Chair. Eventually, he left the guitar behind and turned to the computer keyboard instead. While still in high school, Fosse published his first texts. He wrote short stories and poems for a column titled “Skriverier” (“Writings”) in the Socialist Youth League’s magazine Ungsosialisten (The Young Socialist). The short story “Knuste draumar” (“Broken Dreams”) was among the pieces published. This was in the late 1970s, when literature was widely regarded as a tool for political engagement.

He went on to study at the University of Bergen. Initially, he enrolled in sociology, but the subject reportedly disappointed him. He then turned to literature and philosophy and earned a master’s degree in comparative literature under the supervision of Professor Atle Kittang, the highly influential founder of the department. His thesis, composed of two essays on the theory of the novel, argued that there is no narrator in the novel – only a writer.

When he began his university studies, Fosse was already a father, living in Bergen with his partner and their son. From 1979 to 1981, alongside his studies and writing, he worked as a journalist for the newspaper Gula Tidend , which publishes in Fosse’s preferred Nynorsk version of the Norwegian language.

In 1981, while still a student at the University of Bergen, Jon Fosse won a short story competition hosted by the student magazine StudVest with his story “Han” (“He”). The jury, which included acclaimed Norwegian avant-garde writer Cecilie Løveid, praised Fosse’s distinct style: “It is highly deliberately composed, and the author has succeeded in employing a somewhat original style” (StudVest , no. 9/10, 1981). A year later, the story was featured in the literary magazine Vinduet (3/1982).

Fosse made his debut as a novelist in early 1983 with Raudt, svart (Red, Black), published by Samlaget, Norway’s leading publisher of Nynorsk literature. His reputation quickly grew, and he became a key voice in the language-oriented avant-garde. His second novel, Stengd gitar (Closed Guitar), first published in 1985, was translated into

Swedish in 1988 by the prestigious publishing house Bonnier, earning widespread acclaim across the Swedish press. His 1986 debut poetry collection, Engel med vatn i augene (Angel with Water in Her Eyes), was included in Danish critic Poul Borum’s list of the top 40 Scandinavian poetry works that year. And in 1989, Fosse released his third novel, Naustet (Boathouse), which was also translated into Swedish that same year.

In the late 1980s Fosse also taught creative writing at the Hordaland Writing Academy and contributed essays on literature and literary theory to academic journals. In a series of articles published late in the decade, he explored the relationship between modernism and the social realism that had defined Norwegian experimental writing in the 1970s. Drawing on Marxist, linguistic, and poststructuralist criticism, he developed his own concept of the voice of writing – a theme he further refined in his first essay collection, Frå telling via showing til writing (From Telling via Showing to Writing), published in 1989.

By the end of the decade, Fosse was no longer just a significant writer of avant-garde poetry and novels in Norway – he was recognised as one of the leading Scandinavian authors of his generation.

As one of Scandinavia’s most influential novelists, Fosse’s initial ventures into playwriting came as a surprise to many of his readers. In the mid-1990s, he began writing his first dramatic works in collaboration with Den Nationale Scene (The National Stage) in Bergen. His first full-length play, Namnet (The Name), premiered there in 1995 under the direction of Kai Johnsen. Four years later, the play Nokon kjem til å komme (Someone is Going to Come) received a triumphant reception on the theatrical stages of Paris. Soon The Name experienced similar success in Salzburg and Berlin.

While Fosse’s early theoretical writings had explored the voice of writing in response to the formal challenges of modernism, in the 1990s, his essays took a more religious turn. Through his engagement in themes of negative mysticism and Gnosticism, he seemed to nudge the paradox of the silent voice of writing in a somewhat theological

direction. This transition culminated in the publication of his second essay collection, Gnostiske essay (Gnostic Essays), in 1999. His fiction underwent a similar shift. Melancholia I (Melancholy I ) from 1995 and Melancholia II (Melancholy II ) from 1996 are fictional explorations of the real-life Norwegian landscape painter Lars Hertervig (1830–1902). With this novel, Fosse reached a wider audience. Later, in 2012, the German newspaper Die Zeit even named the novel the best literary work of 1995. During this period, Fosse also published three poetry collections, further expanding his literary range. By the end of his first two decades as a writer, Jon Fosse was on the verge of his international breakthrough and had firmly established himself as a writer to be reckoned with across all three classical branches of literature: the novel, drama, and lyric poetry.

Following his swift international success in the theatre around the turn of the millennium, Fosse’s authorship was characterised by a dynamic interplay between drama and fiction. During this phase, his novels appeared less frequently than in his early career. Morgon og kveld (Morning and Evening) was published in 2000, Det er Ales (Aliss at the Fire) in 2004, while the trilogy Andvake (Wakefulness), Olavs draumar (Olav’s Dreams), and Kveldsvævd (Weariness) were released separately between 2007 and 2014. In 2015, Fosse received The Nordic Council Literature Prize for the trilogy. The jury praised the work for its poetic qualities and timeless storytelling. These novels, in turn, are surrounded by a series of plays – approximately one per year from 2000 to 2010 – that have secured Fosse a prominent position in the international theatrical canon. Draum om hausten. Skodespel (Dream of Autumn), directed by Kai Johnsen, premiered at the amphitheatre stage of the National Theatre in Oslo 1999. Dødsvariasjonar. Skodespel (Death Variations) premiered at the National Theatre in 2002, while Eg er vinden. Skodespel (I Am the Wind ) premiered at Den Nationale Scene in Bergen during the Bergen International Festival in 2007. These last two works have since become part of the most internationally renowned plays by Fosse.

Fosse seemed to withdraw somewhat from the public spotlight between 2011 and 2020, at least in terms of output. Perhaps it was due to his work on the novel Septologien (Septology), which was published in stages between 2019 and 2021. With this monumental prose work, he garnered widespread international recognition as one of the foremost contemporary novelists. This decade saw only two new plays: Hav. Skodespel (Ocean) (2014) and Slik var det. Monolog (Thus It Was) (2020).

When Jon Fosse received the Nobel Prize in Literature from the Swedish Academy in October 2023, he was already widely recognised as one of the most distinguished dramatists and prose writers of his time. His poetry had been included in the Norwegian Hymn Book of 2013, his dramatic works had become integral to modern postdramatic theatre, his children’s books had been adapted for theatre, and his prose, once primarily appreciated by a literary elite drawn to his minimalist experiments, had reached a broader audience engaging with his fiction as part of the great epic tradition of the Western novel. Jon Fosse had become a household name in what often is referred to as World literature.

In his Nobel Prize Lecture, A Silent Language , Fosse reflected on his early fear of reading aloud in secondary school – an overpowering experience in which he felt consumed by his own anxiety. Over time, he came to understand that this fear was deeply connected to his own voice, or rather, his own language. “I had to take [language] back, so to speak,” he explained. His response was to write.

In recent years, Fosse has continued to expand his literary output. His full-length play Einkvan (Everyman) premiered at Det Norske Teatret on 25 April 2024, while his most recent prose work, Kvitleik (A Shining), released in the spring of 2023, explores themes of boredom, loss of meaning, and death. The story can be regarded as a prose version of the 2023 play I svarte skogen inne (Inside the Black Forest), serving – as it stands now – as a striking reminder of Fosse’s sustained artistic engagement with literary language across poetry, prose, and drama.

More than forty years have passed since Samlaget published Fosse’s debut novel Red, Black in 1983. His works continue to evolve.

There is every reason to believe that he will remain a rewarding presence for readers and scholars worldwide. Our dedicated interpretations of his literary efforts to reclaim his own language are one satisfying way to listen to, enjoy, and actualise his frail, yet multiple voices of writing.

Negotiations – Fosse’s scholarly reception 1986–2000

Scholarly engagement with Jon Fosse’s work evolved slowly but significantly, tracing a path from his early theoretical writings to his emergence as a major dramatist. The negotiation between Fosse and the scholarly discourse on literature began in the mid-1980s, when he, armed with his first novels and a master’s thesis on the poetics of the novel, entered the literary-theoretical debate. He published essays on poetics, particularly on the relationship between speech and writing and the status of narrative language, where he developed his conception of the voice of writing. These contributions engaged not only with philosophers such as Martin Heidegger, Theodor Adorno and Jacques Derrida, but also in polemical dialogue with Norwegian writers and academics.

The first academic article on Fosse according to the Fosse bibliography is Asbjørn Aarseth’s “Scripsi Scripsit. En replikk til Jon Fosse” (1988), a reply to Fosse’s essay “Tale eller skrift som romanteoretisk metafor” (“Speech or Writing as a Metaphor in the Theory of the Novel”) (1987), both published in the Norwegian literary journal Norsk Litterær Årbok . These texts reflect the early critical debate on the status of writing in narrative fiction, which took place within both academic and literary discourse at the time.

Sustained literary analysis of Fosse’s fiction began to appear after the publication of the novel Boathouse in 1989. In Finn Tveito’s article “På sporet av den tapte vestlandstid” (“In Search of Lost Time on the West Coast”) from 1992, the scholarly focus shifted to Fosse’s prose fiction, with particular attention to phenomenology, metaphysics and the aesthetics of repetition. This theme was further explored in Ole Karlsen’s “‘Ei uro er kommen over meg’. Om Jon Fosses Naustet (1989) og den repeterende skrivemåten” (“‘A Restlessness Has Come

Over Me’: Repetition in Jon Fosse’s Boathouse (1989)”), from 2000. Both articles were published in Edda. Scandinavian Journal of Literary Research , the most prestigious scholarly journal for literary studies in Norway.

Throughout the early 1990s, theses and academic articles increasingly examined Fosse’s novels through modernist and existential lenses, notably in Drude von der Fehr’s “Det ‘fenomenale’ som leserprosjekt i Jon Fosses Stengd gitar ” (“The ‘Phenomenal’ as a Reading Project in Jon Fosse’s Closed Guitar ”) (1994). Despite Fosse’s early and distinctive poetry, scholarly interest in his poetry remained limited throughout this period.

A rare and influential exception is poet and critic Espen Stueland’s 1996 essay Å erstatte lykka med eit komma (To Replace Happiness with a Comma), which offered a nuanced reading of both Fosse’s poetry and prose, emphasising their shared rhythm, tone, and metaphysical orientation.

By the mid-1990s, as Fosse’s poetics turned increasingly toward mysticism and drama, scholarship began to explore theological, mystical and ritualistic dimensions in his work. This shift is evident in Rolv Nøtvik Jakobsen’s “Det namnlause. Litteratur og mystikk” (“The Nameless: Literature and Mysticism”) (1997) and Unni Langås’s “Intet er hans stoff. Om Jon Fosses dramatikk” (“Nothing Is His Material: On the Drama of Jon Fosse”) (1998).

Toward the end of the decade, following Fosse’s international breakthrough as a playwright, scholars increasingly interpreted his oeuvre as a unified exploration of existential and spiritual themes. Academic writing began to focus on his dramatic language, ritual structures and the interplay between silence, voice and transcendence across genres. What began as a negotiation between literary theory and fiction gradually developed into an attempt to read Fosse’s entire authorship as a singular event in contemporary literature, one that challenges conventional boundaries between prose, poetry and drama.

During the 2000s, literary criticism’s engagement with Jon Fosse’s work expanded across disciplines and geographies. This period saw a marked shift toward drama, theatrical reception and performance studies.

A pivotal moment in this shift was the writing of Therese Bjørneboe, editor of the journal Norsk Shakespearetidsskrift (Norwegian Shakespeare Journal ), particularly her 2003 article “Jon Fosse på europeiske scener” (“Jon Fosse on European Stages”), which analysed the reception of his plays across the continent. This shift can also be traced in the publication of the book Tendensar i moderne norsk dramatikk (Tendencies in Contemporary Norwegian Drama) (2004), in which several articles framed Fosse’s work in terms of phenomenology, negative theology, and material aesthetics.

Thematically, research in this period concentrated on silence, repetition, absence and transcendence. Fosse’s essays in Gnostiske essay (Gnostic Essays), first published in 1999 and reissued in 2004, became essential theoretical texts for understanding the metaphysical dimensions of his writing. Scholars such as Lars Sætre, Tom Egil Hverven and Hadle Oftedal Andersen investigated the aesthetic and theological resonances in both his prose and his drama.

This decade also marked the emergence of substantial international scholarship on Fosse’s work. Suzanne Bordemann’s extensive research, including her PhD thesis and later book Jon Fosses frühe Dramen und ihre Rezeption in norwegischen und deutschsprachigen Medien ( Jon Fosse’s Early Plays and Their Reception in the Norwegian and German Media) (2013), argues that Fosse’s dramatic experiment with linguistic rhythm and language as aesthetic material posed a challenge for contemporary Norwegian and German criticism. French theatre theorist Jean-Pierre Sarrazac situated Fosse within a lineage of European modern drama in Poétique du drame moderne (Poetics of modern drama) (2012). Scholars such as Sarah Cameron Sunde (USA) and Kirsten Wechsel (Germany) contributed new readings of Fosse’s scenographic and rhythmic language.

By the end of the decade, Fosse was no longer studied solely as a

Norwegian modernist. He had become a transnational figure – a writer whose work traversed genre boundaries, spiritual traditions and aesthetic frameworks, and whose language of silence and repetition resonated across cultural and linguistic contexts.

In the last fifteen years, Fosse’s global status was fully consolidated. International scholarship deepened, with significant contributions from French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian scholars. The publication of Septology and the 2023 Nobel Prize in Literature intensified interest in the religious, mystical and metaphysical dimensions of his work.

Theological and post-secular interpretations flourished, especially following his Nobel Lecture, A Silent Language . For example, Paul J. Griffiths offered a reading of Septology through the lens of Christian mysticism in his essay “A Life of Repose in the World to Come”, published in the magazine Commonweal in 2023. Unni Langås and Kjell Arnold Nyhus explored trauma, ritual and mysticism in relation to Fosse’s prose and drama, while Ingrid Nymoen articulated a poetics of silence in post-secular terms.

Meanwhile, scholars such as Avra Sidiropoulou (Cyprus), Maren Anderson Johnson (USA) and Marie Lundquist (Sweden) have explored Fosse’s theatre in relation to Henrik Ibsen and Friedrich Hölderlin, translation, scenography and voice. Studies have also examined the musicality and rhythm of his work – Geir Hjorthol’s Kontrapunkt (Counterpoint) (2023) being one example. The Swedish critic Leif Zern and the Norwegian critic Jan H. Landro published important books on Fosse’s writing and poetics. Fosse’s literature has also become an integral part of studies on theatre directors such as Claude Régy and Thomas Ostermeier.

Fosse’s plays and novels are increasingly studied as expressions of religious experience and literary exploration. The growing interest in the relationship between literature and faith has led to comparative studies with the works of Hölderlin, Ibsen, Olav H. Hauge, and even Christian mystics. A key example of this theological turn is Jean-Luc

Marion’s Création (Creation), delivered as the inaugural Fosse Lecture in 2025, which places Fosse’s writing within a broader phenomenological and theological tradition. The field of scholarly research on Fosse is now too expansive to be surveyed in a brief overview, as the everlengthening Fosse bibliography clearly testifies.

Today, Jon Fosse is read not only as a dramatist or novelist, but as a literary thinker whose writing opens spaces for reflection on being, voice, grace and transcendence. His oeuvre – prose, drama, poetry and essays – has become fully integrated into an academic landscape shaped by intermediality, spirituality and transnational aesthetics. What the research reveals is not only the range of Fosse’s work, but its unique capacity to resonate across disciplinary, cultural and philosophical boundaries – to stage literature itself as a form of silent thought.

This volume represents the first major effort to bring a diverse collection of critical perspectives on Jon Fosse’s authorship to an international audience. While it seeks to engage with global scholarly discourse on Fosse, it also provides a distinctly Norwegian perspective, illuminating his institutional habitus within national literary history – both as a formative influence on Norwegian prose and literary theory in the 1980s and as a key figure in the transformation of modern Norwegian drama in the 1990s.

We therefore open the first part of the volume with Arild Linneberg, historian of literary criticism and essayist. His recollections of professional collaboration, theoretical discourse, and his engagement with Fosse’s essayistic work provide a rare insight into the institution of Norwegian literary studies in the 1980s – an institution that was instrumental in shaping Fosse’s trajectory as a writer. The first section of the volume offers an in-depth investigation into the aesthetic foundations, thematic complexities, and linguistic characteristics of his distinctive style. Linneberg opens the discussion by examining Fosse’s rigorous engagement with aesthetic theory, situating his work within broader literary traditions and exploring the philosophical depth underpinning his prose.

In “Writing as Insight,” Tom Egil Hverven examines Fosse’s Gnostic influences as a lens for interpreting Septologien (Septology). His background as a literary critic and theologian informs his approach, offering original perspectives on the novel’s aesthetic negotiations of spiritual inquiry and literary form. Christine Hamm follows with a comparative analysis of Boathouse and Septology. Her interrogation of masculinities, social dynamics, homosocial bonds, and existential anxiety in Fosse’s depictions of rural men uncovers new and intriguing depths within an important, yet often neglected, thematic strand of his works. Rebecca Boxler Ødegaard investigates the meaning and rhythm of Fosse’s linguistic peculiarities through a close reading of Fosse Prize recipient Hinrich Schmidt-Henkel’s German translation of Trilogien (Trilogy). Her detailed comparison of the literary devices used to achieve poetic effects in Nynorsk and German sheds light on Fosse’s style in both languages. Marius Wulfsberg’s “The Wonder of Literature” turns to Fosse’s recent story A Shining and explores how rhythm, narration, and the polyvocal articulation of the word “kva” (“what”) shape the literary experience of his work. Through an analysis of boredom, bewilderment, voice, and repetition, Wulfsberg shows how Fosse’s prose stages the unfolding of meaning as an open-ended event – where language itself becomes both subject and enigma.

Jon Fosse’s influence on contemporary theatre is undeniable. In collaboration with major European theatre directors such as Claude Régy and Thomas Ostermeier, his dramatic works have reshaped conceptions of language, silence, and presence on stage. Fosse’s literary minimalism and rhythmic style find their fullest expression in theatre; his exploration of existential themes, human isolation, and the unspoken tensions between characters resonates on a global scale.

The second part of this volume investigates Fosse’s contributions to dramatic art, his evolution as a playwright, and the international reception of his works. We begin this section with Kai Johnsen’s personal essay on his correspondence with Jon Fosse during the critical period when Fosse transitioned to writing for the theatre in Bergen. Kai Johnsen has been one of Jon Fosse’s key partners, having directed eleven world premieres of his plays between 1994 and 2014. In the

spring of 2023, he passed on his personal Fosse archive to the National Library in Oslo. Johnsen’s chapter highlights important, and to some degree previously unknown, documentation from this archive, whilst also sharing personal anecdotes from the period he refers to as The Great Fossefall (literally, “Waterfall”, a play on Jon Fosse’s surname, which means “waterfall”). His insider perspective offers valuable insights into the influences and decisions shaping Fosse’s early dramatic works and serves as an academic prelude for researchers exploring Fosse’s turn to theatre worldwide.

Frode Helmich Pedersen follows with a close reading of Someone is Going to Come. Pedersen’s detailed analysis of realist interpretations illuminates how even Fosse’s simplest lines generate profound tensions between desire and manipulation. His analysis offers new insights into the emotional and literary depth of Fosse’s work and clarifies the distinct characteristics of his dramatic style.

Trond Haugen investigates Fosse’s early poetological reflections on writing, arguing that these meditations played a crucial role in his international breakthrough with director Claude Régy in France. The reception of Quelqu’un va venir (Someone is Going to Come), the play that introduced Fosse to the peaks of French theatre in 1999, suggest that Fosse’s fusion of theoretical reflection and dramatic method resonated with French audiences, and became instrumental in elevating his work onto the global stage.

Drude von der Fehr’s contribution, “Metaphysics in the Everyday”, provides a close reading of I am the Wind , one of Fosse’s most philosophical plays. Her analysis explores how ordinary experiences within Fosse’s theatre acquire metaphysical significance, revealing layers of existential meaning that take on new urgency in a world increasingly threatened by climate catastrophe.

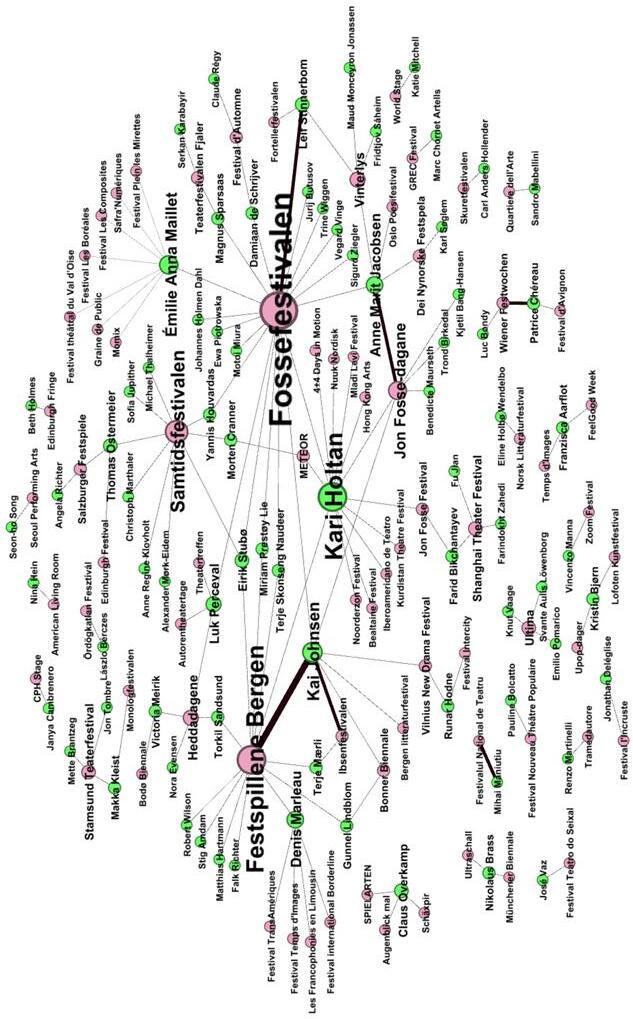

Jens-Morten Hanssen’s chapter engages in a dialogue with Haugen’s, shifting the focus to Fosse’s global reach through an investigation of the festival system and the theatrical networks that have sustained his international reputation as a playwright. By employing digital humanities methodologies, Hanssen examines the institutional mechanisms behind Fosse’s worldwide success, uncovering the

theatrical infrastructures that have propelled his works onto the global stage. Finally, Benedikte Berntzen introduces English readers to the Fosse Archive at the National Library of Norway, offering a glimpse into the archival materials and documents that contextualise Fosse’s oeuvre and provide crucial insight into resources available for future research.

Due to various constraints, The Voices of Jon Fosse does not include a dedicated section on Jon Fosse’s poetry or children’s books. However, several chapters, and particularly those by Linneberg and Hverven, touch upon his poetry in ways that demonstrate the interconnectedness of his literary production. Jens-Morten Hanssen discusses the increasing adaptation of Fosse’s children’s books for the theatre after the turn of the millennium. Rather than a shortcoming, we view this as an invitation to savour the transferable value of the literary analysis of Fosse’s style across genres.

So, what have we learned about Fosse’s literature? At the very least, nothing that can be reduced to a few closing remarks; this volume does not aim to map out Jon Fosse’s entire authorship, summarise the full scope of current research, or champion any one theoretical approach. What it does offer is a series of in-depth engagements with his work – guided by curiosity, critical insight, and a shared recognition of the singularity of his voice. His books continue to call upon us to reflect on what literature is and to negotiate the promise, event, and wonder of his writings. Ultimately, the secret of Jon Fosse’s literature remains. Only in the act of reading does literature begin to reveal itself.

Aarseth, Asbjørn . 1988. “Scripsi Scripsit. En replikk til Jon Fosse”. Norsk litterær årbok 1988: 140–146.

Bjørneboe, Therese . 2003. “Jon Fosse på europeiske scener”. Samtiden 2003(1): 101–115.

Bordemann, Suzanne . 2013. Jon Fosses frühe Dramen und ihre Rezeption in norwegischen und deutschsprachigen Medien. Peter Lang.

Fehr, Drude von der . 1994. “Det ‘fenomenale’ som leserprosjekt i Jon Fosses Stengd gitar”. Skrift 1994(1/2): 57–74.

Fehr, Drude von der , and Jorunn Hareide , eds. 2004. Tendensar i moderne norsk dramatikk. Samlaget.

Fosse, Jon . 1981. “Han”. Studvest (36): 9–10.

———. 1982. “Han”. Vinduet (3): 41–42.

———. 1983. Raudt, svart. Samlaget.

———. 1985. Stengd gitar. Samlaget.

———. 1986. Engel med vatn i augene. Samlaget.

———. 1987. “Tale eller skrift som romanteoretisk metafor”. Norsk Litterær Årbok 1987: 171–188.

———. 1989. Naustet. Samlaget.

———. 1989. Frå telling via showing til writing. Samlaget.

———. 1995. Melancholia I. Samlaget.

———. 1995. Namnet. Samlaget.

———. 1996. Melancholia II. Samlaget.

———. 1999. Draum om hausten. Skodespel. Samlaget.

———. 1999. Gnostiske essay. Samlaget.

———. 1999. Nokon kjem til å komme. Samlaget.

———. 2000. Morgon og kveld. Samlaget.

———. 2002. Dødsvariasjonar. Skodespel. Samlaget.

———. 2004. Det er Ales. Samlaget.

———. 2004. Gnostiske essay. Reissue. Samlaget.

———. 2007. Andvake. Samlaget.

———. 2007. Eg er vinden. Skodespel. Samlaget.

———. 2012. Olavs draumar. Samlaget.

———. 2014. Hav. Skodespel. Samlaget.

———. 2014. Kveldsvævd. Samlaget.

———. 2019–2021. Septologien. Samlaget.

———. 2020. Slik var det. Monolog. Samlaget.

———. 2023. “A Silent Language” (Nobel Prize lecture).

https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2023/12/fosse-lecture-english.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2025.

———. 2023. Kvitleik. Samlaget.

———. 2024. Einkvan. Samlaget.

Griffiths, Paul J . 2023. “A Life of Repose in the World to Come”. Commonweal Magazine, vol. 150 (4): 49.

Hjorthol, Geir . 2023. Kontrapunkt: om litteraturens musikk i Jon Fosses Septologien I. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Jakobsen, Rolv Nøtvik . 1997. “Det namnlause. Litteratur og mystikk”. Norsk litterær årbok 1997: 225–238.

Karlsen, Ole . 2000. “‘Ei uro er kommen over meg’. Om Jon Fosses Naustet (1989) og den repeterende skrivemåten”. Edda 3: 268–279.

Langås, Unni . 1998. “Intet er hans stoff. Om Jon Fosses dramatikk”. Edda 3: 197–211.

Marion, Jean-Luc . 2025. Création. National Library of Norway.

National Library of Norway. 2021. “Fosse-bibliografien” (Fosse bibliography). https://www.nb.no/bibliografi/fosse/. Accessed 19 May 2025.

National Library of Norway. n.d.-a “Bibliografi over norsk litteraturforsking” (Bibliography of Norwegian Research in Literature). https://www.nb.no/ bibliografi/littforsk/. Accessed 19 May 2025.

National Library of Norway. n.d.-b “Norske og nordiske tidsskriftartikler” (Norwegian and Nordic index to periodical articles). https://www.nb.no/bibliografi/ norart/description. Accessed 19 May 2025.

NobelPrize.org. “Jon Fosse – Facts – 2023”. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/ literature/2023/fosse/facts. Accessed 4 June 2025.

Sarrazac, Jean-Pierre . 2012. Poétique du drame moderne. Seuil.

Seiness, Cecilie . 2009. Jon Fosse. Poet på Guds jord. Samlaget.

Stueland, Espen . 1996. Å erstatte lykka med eit komma. Samlaget.

Tveito, Finn . 1992. “På sporet av den tapte vestlandstid”. Edda 1: 66–78.

2. A Unity, However Hidden: On the Origins and Promise of Jon

Arild Linneberg

“… the essay’s innermost formal law is heresy”

Theodor W. Adorno , “The Essay as Form”, 1958

In the late 1980s Jon Fosse encouraged me to make a selection of the essays which Theodor W. Adorno published in four volumes between 1958 and 1974 under the title Noten zur Literatur (Notes to Literature) (Adorno 2019). In 1991, therefore, a volume with selected essays translated into Nynorsk , (New Norwegian), was published under the title Notar til litteraturen (Adorno 1991). Jon Fosse was one of the translators, and he chose to translate Adorno’s essay on “Punctuation marks”. In his first collection of his own selected essays, Frå telling via showing til writing (From Telling via Showing to Writing) (1989), Jon had already written about Adorno’s philosophy of non-identity as well as Adorno’s aesthetic theory.

It was no surprise that Jon was interested in Adorno. In his own essays, Jon often recalls that he found his way to writing through music, through rock music. He used to play guitar in a band, and in his youth, music was more important to him than words. In school he did not like to read, he was especially afraid of reading aloud. In an autobiographic note to the title essay “From Telling via Showing to Writing”, he tells us that he was so afraid that he ran out of the

classroom to avoid reading when the teacher had asked him to read a text out loud.

However, he began to experience that music had its own language, another language, a musical language that does not communicate in the way the normal everyday language does. It was a way of communicating meaning without words, a meaning void of normal meaning, all the same not void of meaning, but communicating a void filled with meaning.

Adorno’s essay on punctuation marks (Adorno 1958) dealt with musical phrasing in language. I remember Jon told me that his way of understanding Adorno’s writing was to listen to Adorno’s language, the music in his language. It was the musicality in Adorno’s language that was the key to understanding Adorno’s philosophy of art, he said. That was a clever observation. Adorno called his work Ästhetische Theorie (Aesthetic Theory); it was a theory that was aesthetic, artistic, in its own form. Jon even encouraged me to translate Adorno’s Ästhetische Theorie from German into Norwegian, and during my eight years at work on this translation (see Adorno 1998, 2021), he was one of my main private interlocutors and consultants.

In 1989 he asked me to write an afterword to his first volume of selected essays, mentioned above, From Telling via Showing to Writing. According to his own preface, he had considered publishing only three of his essays in this volume: one about linguistics and poetics, “Mellom språksyn og poetikk ” (“Between Language Perspectives and Poetics”) (1986), and two on the theory of the novel, “Tale eller skrift som romanteoretisk metafor” (“Speech or Writing as Metaphors in the Theory of the Novel”) (1987), and the title essay “From Telling via Showing to Writing” (Fosse 1989).1

In the 1980s Jon and I worked together at the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of Bergen, and for several

1 The first two essays mentioned are not included in the English edition of essays, An Angel walks through the stage and other essays , translated by May-Brit Akerholt, Dalkey Archive Press 2015. All three essays published in Fosse 1989.

years we also were neighbors, each living in our own small flat in two apartment blocks in the Bergen suburb of Åsane. In addition to Adorno, Jon read and wrote about Jacques Derrida and Mikhail Bakhtin (see Derrida 1967, Bakhtin 1973) – and about several literary philosophers and theoreticians – from Viktor Shklovsky and Roman Jakobson via Georg Lukács to Wayne C. Booth, Gérard Genette, Roland Barthes, Julia Kristeva, Hélène Cixous, Harold Bloom and many others. It is a sort of tradition that some of the most important writers of novels, poetry, drama and fiction have also written about literary theory, that they even were literary theoreticians. In the classical tradition, such literary theoreticians ranged from Horace to Boileau, in modern times from T. S. Eliot, E. M. Forster and Bertolt Brecht to Umberto Eco and Jon Fosse. To me, Jon Fosse is one of the most important writers who is also an impressive theoretician of literature.

The breadth of his reading, and writing, of literary theory and philosophy of literature, is remarkable. He is not afraid of establishing cross-connections nearly everywhere – connections of similarities, but above all connections of differences.

Adorno, Derrida and Bakhtin are cornerstones in his philosophy of literature. However, Jon always transforms what he reads into an integral part of his own way of thinking. I remember being very surprised when he first talked to me about Derrida. It was in the late 1980’s. The most important in Derrida’s thinking is his concept of God, Jon said. What do you mean? I asked. You see, Jon answered, and then he explained to me the relationship between Derrida’s philosophy of the supplement and the gliding of signifiers and what he called God: that nothing in the universe is fixed, it is always changing, in movement, and this movement is God. 2

What Jon said about this, was almost a revolution; he saw connections that very few, if any, had seen. The connection between

2 See “Speech or writing as metaphors in the theory of the novel”, “From telling via showing to writing”, and “Skrivarens nærver” [“The presence of the writer”, not translated into English].

Derrida’s philosophy and theology would become an issue, but at the time Jon recognised it, it was not. And as far as I know, no one had ever mentioned a possible link between Derrida’s potential theological assumptions and Bakhtin’s theory of the novel, of the novel’s novelness. Jon established an interrelation between Derrida’s deconstructive philosophy of the supplement and Bakhtin’s theory of the novel’s polyphony, its multivoicedness: The meaning in language utterances and the meaning in a novel is never fixed, it is always ambiguous, and in that sense also ironic. Jon even discovered a connection between Derrida’s deconstruction, Bakhtin’s semiotics and Wayne C. Booth’s The Rhetoric of Fiction (1961). In this sense his essays on literary theory and his philosophy of the novel were eclectic, although in the best Aristotelian sense: that to see similarities is recognition. And, as the Norwegian philosopher Georg Johannesen wrote, if you see similarities, you do not have to explain them. Jon often mentions Georg Johannesen, who was a Norwegian poet and the first professor of rhetoric in Norway. He too worked at the University of Bergen. In Georg Johannesen’s philosophy of rhetoric, irony was the central trope (see Johannesen 1981, 1987). I think it was Johannesen’s foregrounding of the rhetoric of tropes, concentrating on irony as the fundamental trope both in everyday language and in literature, that paved the way for Fosse’s most important definition of the novel, not only as irony in the linguistic sense, but as irony as an attitude to the world. Moreover, it was not merely in the Socratic sense in the way Søren Kierkegaard analysed Socrates’ world view, but in a quite unique way, a Fossean way to regard the novel as negative mysticism .

I remember that I held some lectures at the Academy of Writing in Bergen on Viktor Shklovsky’s Theory of Prose (1925) and Georg Lukács’ Theory of the Novel (1920). Jon was one of the founders of the academy, at the same time as he was assistant professor at the Department of Comparative Literature at the University in Bergen. Jon pointed to a surprising connection between Viktor Shklovsky and Georg Lukács, between Shklovsky as a founder of the linguistic turn in literary theory and in the philosophy of language, and Georg Lukács, who used Jon’s own term for the novel as irony in a theological

way: “the writer’s irony is a negative mysticism in a world without God” (Lukács 1971, 90). Some years later Jon’s own concept of the novel as negative mysticism would lead him to Harold Bloom. However, in Jon Fosse’s universe, not only philosophers and thinkers of a different kind are combined, but all sorts of different subjects and objects appear. Like in the old tradition of essays from Erasmus Roterodamus via Michel de Montaigne to Walter Benjamin – and in Norway from Aasmund Olavsson Vinje to Ole Robert Sunde and Rune Christiansen – no detail seems too small to be treated with attention. Jon Fosse’s first collection of non-fiction prose is composed mostly of texts about other authors and thinkers in addition to and in connection with a presentation of his own poetics. The order of the essays is chronological; the formative principle of combining things and keeping things together, is the evolution of subjects in his own writing in the six years’ period from 1983 until 1989. This starts with an essay on social realism and modernism and ends with two essays, first the title essay and lastly a short piece on the 1989 Swedish translation of Peter Handke’s 1986 Die Wiederholung (Repetition). Fosse ends his review of Handke with a discussion of the impossibility of telling. A son asks his father to tell the story of his life, but the father finds it very difficult above all because he has killed an Italian during the First World War. The father cannot find the right words to tell his story, so he simply says: It is impossible to tell it, you must write it! In this subtle way the last essay in this first volume of his selected essays ends with the book’s main theme: the road from the impossibility of telling to the necessity of writing.

Jon Fosse’s next and last collection of essays has the title Gnostic Essays (Fosse 1999). This book is not composed chronologically in the same way, although the first essays were written in 1993 and the last one in 1999. The book is divided into five sections with different subjects: Visual , Theoretical , Personal , Literary, Theatrical . I will return to aspects of this second volume of essays later on and especially to the meaning of its title: Gnostic Essays.

More than 25 years after Fosse’s second and last collection of essays was published in 1999, this work suddenly appeared to me in a new light. In one of the final essays, “Old houses” (Fosse 2015), he wrote that everything he had written in recent years, was written in his writing room in an old house with a view to the sea, to the fjord or to the ocean (Fosse 2015, 101).

I had moved from Bergen to an island on the West Coast not far north of Sognefjord. In the meantime, Jon had bought himself a boat, a double-ended motor launch of a type called a snekke in Norwegian, and a cottage with a boathouse in Dingja, a small place near the mouth of Sognefjord.

I was very surprised when I found that Honoré de Balzac’s novel Séraphîta , first published in 1834, was set in a Norwegian fjord called “Stromfjord”. It is quite obvious that this fjord resembles Sognefjord. Balzac never visited the place, but he may have seen paintings by the Danish painter Johannes Flintoe (1787–1870) or the Norwegian J. C. Dahl (1788–1857). Balzac’s descriptions of the area looked like they were based on paintings like Flintoe’s Old Birch Tree by the Sognefjord (1820) and J. C. Dahl’s Winter at the Sognefjord (1827).

How could Balzac otherwise have described this Norwegian landscape without having been there or having seen these or similar paintings? All the same it is an interesting coincidence that Balzac’s story Le Chef-d’oeuvre inconnu (The Unknown Masterpiece) was first published in 1831. It is a story about the painter Maître Frenhover, who worked for ten years to create what he believed was a masterpiece, but when his friends finally got to look at it, they saw nothing of the kind. The painting was a failure. It had some fascinating, beautiful details, but all in all it was only a chaotic mess of colours. It is a story about the relationship between the artist’s work and the reasonable assessment of the spectator, Giorgio Agamben writes in his analysis of the story (Agamben 1999, 9).

To Paul Cézanne Balzac’s story showed the fundamental and problematic correspondence between art and reality, the problem of depicting reality in art (Ashton 1991, ch. 2). Whatever Maître

Frenhover saw, he was not able to depict accurately. There was no direct correspondence between his perception and his painting, he had seen something he was not able to describe. The mess of colours, despite having some beautiful details visible, was a sort of cosmos without any visible meaning, the meaning was hidden, not for the creator of this universe, but for everybody else.

Three years after The Unknown Masterpiece , Balzac published Séraphîta . This novel was the third in the row of Balzac’s series of three philosophical novels at the beginning of The Human Comedy (1829–1848). 3 The three philosophical novels have the same main subject: Emanuel Swedenborg’s mysticism. In Séraphîta , an angel, both man and woman, is sent down to Earth from Heaven – to an area on the Sognefjord coast. Seraphita and Seraphitus, a hermaphrodite being, shows us the mystery of sex, but also at the same time the hidden unity of the universe. It may be worth mentioning that the two paintings of Flintoe and Dahl, especially Flintoe’s painting of the old birch, also symbolise the hidden unity of the universe: the absolute.

Jon Fosse took a great interest in painting, he even wanted to be a painter, he tells us in an essay in the opening of Gnostic Essays (Fosse 1999, 14). Indeed, the first of this book’s five parts deals with painting and painters. Briefly summarised, his point of view is that there is something we cannot see behind what we see. This unseen is the mystical, the absolute unity, name it God. To me, having read Balzac anew in the context of Jon Fosse, it was exciting to notice that Fosse points to Cézanne as the most fascinating painter – especially as we know the impact Balzac’s novel about Maître Fenhover had had on Cézanne. According to Balzac, his novels on mysticism formed the basis for his later and more realistic novels in The Human Comedy. “Det mystiske i det konkrete” (“The mystery of the concrete”) is the title of one of Fosse’s essays in Gnostic Essays. 4 According to Fosse, all his

3 The first of the kind was the short story Les proscrits (1831), the second Louis Lambert (1832).

4 See also Aagenæs 1999. “The Mystery of the Concrete” is not one of the essays translated into English in An Angel Walks through the Scene (Fosse 2015).

novels are realistic, but they also at the same time incorporate the mystical, Fosse says. The mystery of the concrete, and even Swedenborg’s mysticism, is important in the modern literary tradition, from Balzac to Baudelaire, from Baudelaire to August Strindberg, from Strindberg to the French surrealists, and because of these authors also for Walter Benjamin. Swedenborg was of fundamental importance to Strindberg, for instance, in his work A Dream Play (1902). Strindberg and his mysticism paved the way for French surrealism, Louis Aragon’s Paris Peasant (1926) is unthinkable without Strindberg and his mystical, surrealistic Fairytales (1904). 5 André Breton mentions Swedenborg’s mysticism as a precursor in his Manifest of Surrealism (1924), and Walter Benjamin was deeply influenced by Strindberg and Aragon in The Arcades Project, which he wrote between 1927 and his death in 1940 (Benjamin 1982). 6 Jon Fosse’s writings, especially in his essays, further develop this literary and philosophical tradition.

The common denominator is the mystery of the concrete, the mysticism of everyday life, as Walter Benjamin called it. To Fosse, this mystery of the concrete seems to be connected to the Norwegian landscape, or, rather, that is where he finds it, and especially on the coast and in the fjords. In his essay “For the sun to rise”, he even locates Wittgenstein in this landscape (Fosse 2015, 105–109), where Wittgenstein built a cottage with a view to a fjord and sat there thinking and writing in solitude surrounded by the everlasting mountains. Wittgenstein sat there, “waiting for the sun” and thinking about “the area of the inexpressible” (Fosse 2015, 107). To Fosse, Wittgenstein was a mystic waiting for the light, to be enlightened.

Fosse wrote an essay on Nynorsk , “his beloved New Norwegian” (Fosse 2015, 36–40). The version of the Norwegian language he uses is one of the two officially recognised in Norway. The roots of Nynorsk go back to the language historically spoken in rural Norway. Today it is used mainly in the country’s southern and central areas, particularly

5 See Linneberg and Sund 2018 and https://walterbenjamin.no.

6 See Linneberg and Sund 2017.

along the Norwegian West Coast. Some 10–15 percent of the Norwegian people, around 500 000, use Nynorsk as their primary language of written communication.

Although based on old traditions, Nynorsk is called new because it was constructed as a written language standard in the latter half of the nineteenth century (after 1850) and developed by some of the most important Norwegian linguists and authors. Nynorsk has a very strong literary tradition. From a linguistic point of view, this is Jon Fosse’s tradition, and this tradition also has had a deep impact on his way of thinking.

Many early Nynorsk authors wrote not only about Norwegian nature, but about the mystery of the concrete. Arne Garborg (1851–1924), Ivar Mortensson-Egnund (1857–1934), Olav Nygaard (1884–1924) and others combined a materialist realism with mysticism in their works. The mystery of the concrete, the invisible behind the visible, is also fundamental in Fosse’s novels, as outlined in his essays, and not least in his theory of the novel.

Dog and angel – and Georg Lukács’ Theory of the Novel Dog and Angel is the title of a collection of poems that Jon Fosse published in 1992. The title was strange. What is the meaning of the combination of these two words? I asked myself when I wrote a review of the book. We know what a dog is, and whether we believe in their existence, or not, we have an idea of what angels are or represent as something holy, divine.

One of the poems goes like this:

Ingenting overtyder meg meir om Guds nærvær enn fråveret av mine døde venner. Gud er mine døde venner.

Gud er alt som forsvinn.

God kunst er guddommeleg: god kunst er delaktig i det ubestemmelege, som er Gud, i det bestemmelege.

Utan døden ville Gud vere død.

Alt seier at Gud er. Ingenting seier at Gud finst.

Kvifor skal Gud finnast? Gud som er?

Å finnast er å vere borte frå Gud

for at Gud skal kunne vere og dermed for at alt skal kunne vere (Fosse 1992, 64).

Nothing is, to me, more convincing about God’s presence than the absence of my dead friends. God is my dead friends. God is everything that disappears.

Great art is divine: great art participates in the indeterminate, that is God, in the determinable. Without death God would be dead.

Everything tells us that God is. Nothing tells us that God exists. Why should God exist? God that is?

To exist is to be away from God so that God could be so that everything could be. 7

In the history of the relationship between man and animals, something strange takes place in the northern parts of Europe at the beginning of the nineteenth century. There are mythical stories about the St Bernard breed of dog, which could find and save people who were lost in the wilderness. The dog was called “a saving angel”. Dogs became angels, saving human beings: the dogs were profane angels, a symbol of the secularisation of the hidden transcendent powers.

In the poem quoted above, God is absent, but present in his absence, present in the material world around us. That could be a plausible meaning of the collection’s title Dog and Angel . In this respect the poem is almost an emanation of Fosse’s enigmatic theory of the novel around 1990.

In an essay on Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory, “Art as the Precondition for Philosophy” (Fosse 1989), Fosse discusses art as enigma for the first time. 8 As his point of departure, Fosse takes a chapter in Adorno’s work concerning the enigmatic character of art, truth content and metaphysics (Adorno 2021, 308–333). Here Adorno argued that art is always enigmatic, works of art are enigmas without answers. An

7 My translation.

8 This essay is not included in An Angel Walks through the Stage and Other Essays (Fosse 2015).

absence of meaning points at a meaning that lies beyond normal meaning, i.e. an absent meaning that cannot be communicated. In the 1980s Jon and I often discussed Adorno’s philosophy and his aesthetic theory, and I remember Jon pointed to a more or less hidden connection between Viktor Shklovsky and Adorno. This was because Shklovsky also claims that an enigma hides in art as the basic layer of aesthetic language. To Shklovsky the defamiliarisation of reality, the strangeness of art, is enigmatic. The essence of art’s language is enigmas that make us see the world in a new way. To Jon Fosse both these theoretical views lie at the heart of his conception of art and of the relation between art and reality.

Among Fosse’s extended reading of literary theory and theories of the novel, one book made a special impression, and in this book only one sentence stood out as exceptional. I have already mentioned both the book and the sentence. The book was Georg Lukács’s The Theory of the Novel (1971), and the sentence was that “the writer’s irony is a negative mysticism to be found in a time without God” (Lukács 1971, 90). Maybe it is time to ask what this sentence implies both in Lukács’s and in Fosse’s thinking?

The sentence stands at the centre of the concluding section “Irony as mysticism”, in Lukács’s chapter 5, “The historicophilosophical conditioning of the novel and its significance” (Lukács 1920, 1971). Although Fosse only quotes this sentence from the book, his discussion of the implications of the sentence in fact follows Lukács. “For the novel, irony consists in this freedom of the writer in his relationship to God, the transcendental condition of the objectivity of form-giving”, Lukács wrote (1971, 92). The writer “can see where God is to be found in a world abandoned by God” (1971, 92). Lukács concluded by stating that for this reason the novel was “the representative art-form of our age: because the structural categories of the novel constitutively coincide with the world as it is today” (1971, 93). Among these structural categories were “the detour by way of speech to silence” in a world of “empty immanence” (1971, 91, 92).

Like Lukács, Fosse considers the novel to be a representative art-form of his time, and he had already further developed at least

three of Lukács’s conclusive categories (silence, transcendence, and the objectivity of form-giving) in his own poetics before quoting Lukács on negative mysticism.

For some years, Fosse was a member of the Norwegian Society of Friends (Quakers), to whom silence is, in a way, more important than words. In an essay he mentions Samuel Beckett as one of his favourites, and in Beckett we find a similar scepticism towards the spoken language, and language as such, as among the Quakers. In Aesthetic Theory Adorno describes Beckett’s art – and all great art – as “close to silence” or “close to being silent”. The reason for this silence is that we “cannot tell” what cannot be told. We cannot say much about transcendent matters. Adorno calls the transcendent truth in art “an interrupted transcendence” and “a blocked transcendence”. We have no admittance to the absolute, but art points in the direction of something unknown that we call transcendence (Adorno 2021, 245).

Adorno’s discussion of silence and transcendence comes very close to Fosse’s view as sketched above, or maybe the other way around, Fosse’s view comes very close to Adorno’s. To both Fosse and Adorno, it is the musicality of language that allows us to “hear” silence, not only because sound and silence are the basic components of music, but because the language of music and the musicality of language do not refer to an external reality in the same way as everyday language and the language of concepts do. For that reason, Adorno describes the language of art as “a language that is similar to language, but is not language” (“Sprachähnlichkeit der Kunst”). This is quite similar to Fosse’s discussion of art’s language in his essay “From telling via showing to writing”, where he describes his way from rock rhythm to writing (Fosse 2015, 14–21).

The play Namnet (The Name) (Fosse 1995) tells a simple story: a young couple, expecting a child, have no place to live, and they move in with the woman’s parents. The drama’s plot, however, is more complex. The conflict centres on the problems of communication between the characters and how difficult it is to express feelings and thoughts in everyday language. I think the play’s title, The Name, alludes to Fosse’s discussion of Walter Benjamin’s philosophy of language in an essay

called “The Deepest Need for Speechlessness”, written in 1990, but first published in 1999 in Gnostic Essays and translated to English in An Angel Walks Through the Stage and Other Essays (Fosse 2015, 28–32).

Jon Fosse here considers Benjamin’s essay “On Language as Such and on the Language of Man” (1928) to be “at once the most comprehensible and most incomprehensible notion [of language] I have ever read” (2015, 29). Benjamin’s theory of language is “a mystical language theory”, language itself becomes “messianic ” (his emphasis) (2015, 30).

Fosse ends the essay with a beautiful quotation from Benjamin, stating the duality of language, that language is both what can be communicated and what cannot be communicated: “In all grief, there is the deepest need for speechlessness” (2015, 31).

Benjamin’s philosophy of language is deeply rooted in Jewish mysticism, Kabbalah, and focuses on the name. The lost identity in the relationship between utterance and meaning corresponds with Derrida’s and Bakhtin’s theories of language as presented by Fosse in his first collection of essays in 1989. In 1995 Derrida’s text On the Name was also published in English. In three essays Derrida considers the problematics of naming, alterity and transcendence, and this work lays open the connection between deconstruction and negative theology: Kabbalah.

“The breaking of the vessels”, Kabbalah and deconstruction

Gnostic Essays opens with an epigraph from Harold Bloom, and one of the essays in the book has the title “Bloom, Canon, Literary Quality, Gnosis”.9 It is reasonable to assume that the title of this volume of essays points at Bloom. Fosse only quotes one line from Lukács’s Theory of the Novel , although the main aspect of his own theory of the novel takes its point of departure from Lukács’s definition of the genre as “negative mysticism” (see also Hagerup 1999). That being so he does not quote many sentences from Bloom either; the most important and extensive quotation is in the last part of the essay on gnosis. According

9 First published in Vagant , 1998, Fosse 2015, 102–105.

to Fosse, Bloom writes in Omens of the Millenium: The Gnosis of Angels, Dreams, and Resurrection (1997) that “the gnostic insight – or the ‘direct acquaintance of God within the self” – should be sought neither in the empirical nor in the intelligible world, neither through the senses nor in concepts”, it must be sought “in between these, in a between-world we may only access through good art’s pictorial presentation”.10 Fosse goes on, stating that to Bloom “it is literature which first and last has given him the gnostic insight he presents as his wisdom, his gnosis” (Fosse 2015, 103). The connection between Lukács and Bloom is a strange constellation in Fosse’s philosophy of literature. Yet it is not as strange as it may seem. The connecting line is Jewish mysticism.

In Kabbalah and Criticism (1975) Harold Bloom presents his deconstructive philosophy of literature and its theological basis. According to the book’s prologue, Kabbalah and Criticism contains the following chapters. The first chapter of the book offers the “primordial scheme”: Kabbalah . In this chapter Bloom deals with the fundamental aspects of Kabbalah, from God’s creation of the world, Ein Sof and tzimtzum , to the recreation of a new world order, through tikkun . In the next chapter, “the scheme is related, in detail, to a theory of reading poetry”. Bloom’s concepts in his theory of interpretation are directly diverted from and related to the kabbalistic scheme of interpreting the Torah. “A manifesto for antithetical criticism, based on this theory, constitutes the third and final chapter” (Bloom 1975, 12).

Bloom also establishes a link to his two works The Anxiety of Influence (1973) and A Map of Misreading (1975 b), connecting them to the kabbalist way of interpreting texts, because in Kabbalah every interpretation in the tradition – and Kabbalah means tradition – is a contribution to a new way of seeing the tradition and keep it alive by reshaping it. From this point of view even The Western Canon. Books and School of the Ages (1994) could also be seen as a continuation of Kabbalah and Criticism .

10 I have changed the English translation’s (Fosse 2015) ‘intelligent’ to ‘intelligible’ and ‘presentation of the figurative’ to ‘pictorial presentation’.

It is not difficult to see Bloom’s writings as a main source for Fosse’s theoretical exercises. To mention some of Fosse’s basic concepts, such as writing, irony, deconstruction, theological mysticism, Gnosticism – they are all there also in Bloom’s main works as well. To what degree Fosse was familiar with the kabbalistic grounding of Bloom’s literary theory, I don’t know. But it is of no importance, when pointing to Bloom, Jon Fosse is pointing at a theory with Kabbalah as a fundament. “The primal act is that God taught, the primal teaching is writing ” (Bloom 1975, 80), Bloom writes, and adds: “Kabbalah is a theory of writing ” (Bloom 1975, 52). “Kabbalah, if viewed as rhetoric, centres on two series of tropes: first – irony”, he also writes (Bloom 1975, 73).

As mentioned above, Fosse saw the theological implications of Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction already in De la grammatologie (1967), and in Kabbalah and Criticism , Bloom underlines the connection: “More audaciously than any developments in recent French criticism, Kabbalah is a theory of writing (…) Kabbalah speaks of writing before writing (Derrida’s trace),” he says, and continues to talk about “the brilliance of his Grammatology” in this context (Bloom 1975, 52).

In the commentaries to Kabbalah and Criticism , it is common to mention the poets that Bloom discusses, such as John Ashbery and Elizabeth Bishop. However, Bloom also discusses Kabbalah in interpretations of the works of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Wallace Stevens. In my opinion, even more important in this work are the philosophers he mentions and their kabbalistic influences. In addition to Derrida and French poststructuralist criticism, Bloom points to fundamental kabbalistic features in psychoanalyses, semiotics, critical theory and, not least, in German idealism. He interprets kabbalistic features in the works of Sigmund Freud and Thomas Kuhn; he discusses the parallels between Charles S. Peirce’s semiotics and the fundamentals of Kabbalah in the models of Cordovero, Luria and Gershom Scholem; and he even sees the Frankfurt School’s

negative dialectics in the light of Jewish mysticism: in the philosophy of Marcuse, Adorno and Horkheimer.11

“Hegel,” Bloom writes, “was impressed by what he knew of Kabbalah”, and Hegel knew “creation as the breaking of the vessels” (Bloom 1975, 90). As Gershom Scholem has shown in Zohar: The Book of Splendor (1949), the breaking of the vessels is the central kabbalistic figuration of God’s creation of the world. To create the universe, God withdraws from the world, and with his contraction, the world falls apart into broken vessels, that contain evil, but also glimpses of light, traces of God. To gather these glimpses of light is man’s task on Earth, tikkun, to create a better and different world anew by rearranging the fragments of reality.

I mention this not only because it lies at the heart of Bloom’s gnostic version of Kabbalah and is therefore a central layer of Fosse’s way of thinking, but because this reveals a hidden connection between the two main theorists in his essays: Harold Bloom and Georg Lukács. The breaking of the vessels is also hidden between the lines in Lukács’ Theory of the Novel , referring to Hegel’s presentation of the breaking of the vessels in 1807 in Phenomenology of Spirit (1977). Hegel’s German term for this is “Lichtwesen”. He tells the story of God’s creation of the world, the divine Lichtwesen : “Light disperses its unitary nature into an infinity of forms and offers up itself as a sacrifice to being-for-self, so that from its substance the individual may take an enduring existence for itself” (Hegel 1977, 420). To Lukács, “the irony of the novel is the self-correction of the world’s fragility”, i.e. of the dispersion of the light.12 In the novel, the parts are “united” in “the structure of the novel’s totality” (Lukács 1971, 75–76). This is the novel’s atheistic mysticism, the negative mysticism in a world without God. The world has fallen apart, in the novel the parts are united in a new totality. Moreover, by following Hegel’s dialectical scheme for the development of history, Lukács already subscribes to the hermetic tradition of mysticism in German idealism (Magee 2001).

11 See also Linneberg 2021.

12 I owe this perspective to Agata Bielik-Robson (2020).

In this context we could have interpreted Jon Fosse’s novel Melancholia (1995), about the painter Lars Hertervig, “the painter of light”, living in a dark world of depression and melancholia. But that is another story.

The essay as form is characterised by its “cross-connections between elements, something for which discursive logic has no place”, Adorno says. In these cross-connections between elements we find “a unity, however hidden , in the object itself”. This unity is created when the essay “approaches the logic of music, that stringent, and yet aconceptual art of transition” (Adorno 1958, 45, my emphasis). His conclusion is that “the essay’s innermost law is heresy. Through violations of the orthodoxy of thought, something in the object becomes visible which it is orthodoxy’s secret and objective aim to keep invisible” (Adorno 1958, 47).

In the cross-connections between the elements in Fosse’s essays we find a unity, however hidden, not only between Georg Lukács (German idealism) and Harold Bloom, but between the Frankfurt School’s Adorno, Benjamin and Marcuse, Bakhtin’s semiotics and Derrida’s deconstruction. Through violations of the orthodoxy of thought, something becomes visible: a negative theology, based on the mysticism in Kabbalah and Gnosticism, which it is orthodoxy’s secret and objective aim to keep invisible.

This unity, however hidden, constitutes the origins and promise of Jon Fosse’s essays.

One of the very last essays in Gnostic Essays has the title “The Demoniacal Writer” (Fosse 2015, 115–116). Fosse writes about Ibsen:

The better you want to be, the more stupid and evil you are, the Ibsenite wisdom seems to say.

And if Norwegian politicians had understood this in their eagerness to make Norway to something as disgusting as a “leading country” (…) it would have been better to live in this land. (…) But Norway, the land of goodness, has to this day not understood Ibsen, the demoniacal writer. Instead, they have made him a spokesman for a lot of “isms”, like

“feminism”, although there never existed a less constructive author than Ibsen. It is nearly impossible to misunderstand more.13

Because, Fosse continues, “what you find in Ibsen’s works is pure destruction. A destruction that is liberating, and that could make us wiser and better as human beings, because it gets us out of the idiot-like condition, that unavoidably makes things worse.” Further, he quotes the former prime minister of Norway, Gro Harlem Brundtland, who, during the Olympic Games at Lillehammer in 1994, famously said: “It is typical Norwegian to be good”.

“If this had been uttered in a play of Ibsen”, Fosse writes, “it would have been revealed, to all who understand, that in effect it means the opposite: it is typically Norwegian to be evil”.

In gnostic philosophy, the demiurge is an evil sovereign who rules over lower powers. The kabbalist Franz Kafka, who Fosse has translated into Norwegian, said that this world was the worst and most evil of all worlds. However, according to Kafka’s antinomic mysticism based on Sabbatai Zevi, this negation points to another world. A better world (see Adorno 1982).

When Jon was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, I sent him an email to congratulate him. In his reply he once again talked about his attraction to the fjords on the Norwegian west coast, especially Sognefjord.

I look out of the window, I see the “fingers of light” from Heaven down to Earth, the sun flowing through the sky, glittering on the water, and I don’t have to refer to Zohar. The Book of Splendor to say that so is, to me, Jon Fosse’s answer to the world’s evils also in the light of his essays.

13 My translation.

Aagenæs, Bjørn . 1999. “Det konkrete i essayet. Om Gnostiske essay av Jon Fosse”. Vinduet (Vinduet.no) 12 November 1999, accessed 5 June 2025, https://www. vinduet.no/kritikk/det-konkrete-i-essayet-om-gnostiske-essay-av-jon-fosse.

Adorno, Theodor W . 1958. Noten zur Literatur (I), Suhrkamp Verlag. See Adorno 2019.

______. 1982. “Notes on Kafka”. In Prisms, 243–271. MIT Press.

______.1991. Notar til litteraturen. A selection of Adorno’s Noten zur Literatur. Translated into Norwegian by Arild Linneberg, Jon Fosse et al. Samlaget.

______. 2019. Notes to Literature. Translated by Shierry Weber Nicholson. Columbia University Press.

______. 1998. Estetisk teori. Translated by Arild Linneberg. Gyldendal.

______. 2021. Estetisk teori. Translated by Arild Linneberg. Revised edition with an introduction. Vidarforlaget.

Agamben, Giorgio . 1999. The Man Without Content. Stanford University Press. Ashton, Dore . 1991. A Fable of Modern Art. University of California Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail . 1973, 1984. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. University of Minnesota Press.

Benjamin, Walter . 1982. Das Passagenwerk. Suhrkamp Verlag.

______. 2017. Passasjeverket I–II. Translated by Arild Linneberg and Janne Sund. Vidarforlaget.

Bielik-Robson, Agatha . 2020. “The Void of God, or the Paradox of the Pious Atheism: From Scholem to Derrida”. European Journal for Philosophy of Religion, 12 (2): 109–132.

Bloom, Harold . 1973. The Anxiety of Influence. Oxford University Press.

______. 1975. Kabbalah and Criticism. Seabury Press.

______. 1975b. A Map of Misreading. Oxford University Press.

______. 1994. The Western Canon. Books and School of the Ages. Harcourt Brace & Company.

______. 1997. Omens of the Millenium: The Gnosis of Angels, Dreams, and Resurrection. Riverhead books.

Derrida, Jacques. 1967. De la Grammatologie. Éditions des Minuits.

_____. 1995. On the Name. Stanford University Press.

Fosse, Jon. 1986. “Mellom språksyn og poetikk. Forteljing med sleivspark etter Kjartan Fløgstad”. Vinduet (3): 54–59.

______. 1987. “Tale eller skrift som romanteoretisk metafor”. Norsk litterær årbok 1987: 171–188.

______. 1989. Frå telling via showing til writing. Samlaget.

______. 1992. Hund og engel. Samlaget.

______. 1995. Namnet. Samlaget

______. 1999. Gnostiske essay. Samlaget

______. 2015. An Angel Walks Through the Stage and Other Essays. Translated by May-Brit Akerholt. Dolkey Archive Press.

Hagerup, Henning. 1999. “Etterord. Jon Fosse – en negativ mystiker?” In Fosse, Gnostiske essay, 265–278.

Handke, Peter. 1986. Die Wiederholung. Suhrkamp Verlag.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. 1977 [1807]. Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated by A.V. Miller. Oxford University Press.

Johannesen, Georg. 1981. Om den norske skrivemåten. Gyldendal.

______. 1987. Rhetorica Norvegica. LNU.

Linneberg, Arild. 1989. “Jon Fosse – skrivern”. Afterword to Fosse, Frå telling via showing til writing, 165–173.

______. 2021. “Det gåtefullt estetiske: Estetisk teori og det estetisk gåtefulle”. Introduction to Adorno, Estetisk teori, 7–113.

Lukács, Georg. 1971 [1920]. The Theory of the Novel: A Historico-Philosophical Essay on the Forms of Great Epic Literature. Translated by Anna Bostock. The Merlin Press.

Magee, Glenn Alexander. 2001. Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition. Cornell University Press.

Scholem, Gershom. 1949. Zohar: The Book of Splendor. Schocken Books.

Shklovsky, Viktor. 1991 [1925]. Theory of Prose. English edition. Dalkey Archive Press.

Sund, Janne and Linneberg, Arild. 2017. “Innganger og utveier. Passasjer om Walter Benjamin og Passasjeverket”, Passasjeverket I. Translated by Arild Linneberg and Janne Sund, 13–107. Vidarforlaget.