The Ginsberg collection

The Map Centre contains the world’s most extensive collection of printed maps of Norway, the Nordic countries and the High North. The oldest of these maps are from 1482, and the newest from the late 1800s. As a collection, these maps represent both a history of the geographical epistemology of the Nordic countries and a comprehensive account of the development of the maps and the subject of geography.

Most of what is found here is part of the Ginsberg collection, which consists of approximately 2000 maps, atlases and older geographic books and travelogues. In the Map Centre, this material is supplemented by selected maps and literature from the National Library’s wider collections. The National Library’s collection of maps contains approximately 150,000 maps. All maps printed in Norway after 1882 are preserved here, since the legal depositing scheme became a legal requirement that year. The National Library’s collection of maps also contains a number of older and international material.

The National Library of Norway’s Map Centre opened on 2 September 2019.

Heinrich Bünting: “Heele Jordenes kretz affmålningh liik ett Klöffuerbladh” from Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae, Stockholm, 1595

The texts are written by Benedicte Gamborg Briså and Erling Sandmo

Design: Superultraplus Designstudio

Print: Erik Tanche Nilssen AS

Printed maps of Norway and the High North, 1482–1845

The oldest printed map of the Nordic countries was created at a time which today seems strange and far away, and it shows a region unknown to the cartographers themselves. In the far north, the world appears to extend beyond the limits of geography and is surrendered to darkness and cold.

They did not know it at the time, but those who drew and studied these maps were about to gain a new and wider view of the world. They were at the threshold of what would become the great European powers’ Age of Discovery. For those who were discovered, it marked the beginning of very different histories.

The High North, too, was unknown land. Maps show us how this region was explored and mapped. Many of the Dutch sailors who passed the Norwegian coast were pursuing more distant goals, but the knowledge they acquired along the way lay the foundation for new maps of the landscapes they passed.

Like people in other regions explored by the major European seafaring countries, the people in the far north were well acquainted with their surroundings. What was remote for others was near for them. However, the maps provided new perspectives and a new distance to the familiar.

Around 1400, it became increasingly popular among European intellectuals to study classical Antiquity. The many hundreds of years that separated them from this distant past were mockingly written off as the ‘Middle Ages’. The present time was to become the rebirth of Antiquity, the Renaissance. Cartography was decisively shaped by the Renaissance, when geographers rediscovered the Greek Ptolemy’s work Geografia. It was a series on map projects and cartography written at Alexandria around 1st century and translated from Greek into Latin in 1406, so it could be read by all scholars and learned men.

The Christian world map of the Middle Ages portrayed God’s creation and plan and were not meant to be exact replicas of the physical world. Jerusalem was the centre of the world and, consequently, of the world map, and the maps were typically drawn with east – where the sun rises – at the top. Ptolemy’s Geografia was completely different. It offered a system of latitudes and longitudes that made it possible to locate cities accurately on the map. This system could also be used to identify smaller areas as part of the entire world, as the system of latitudes and longitudes applied everywhere. The Ptolemaic maps placed north at the top and had no centre.

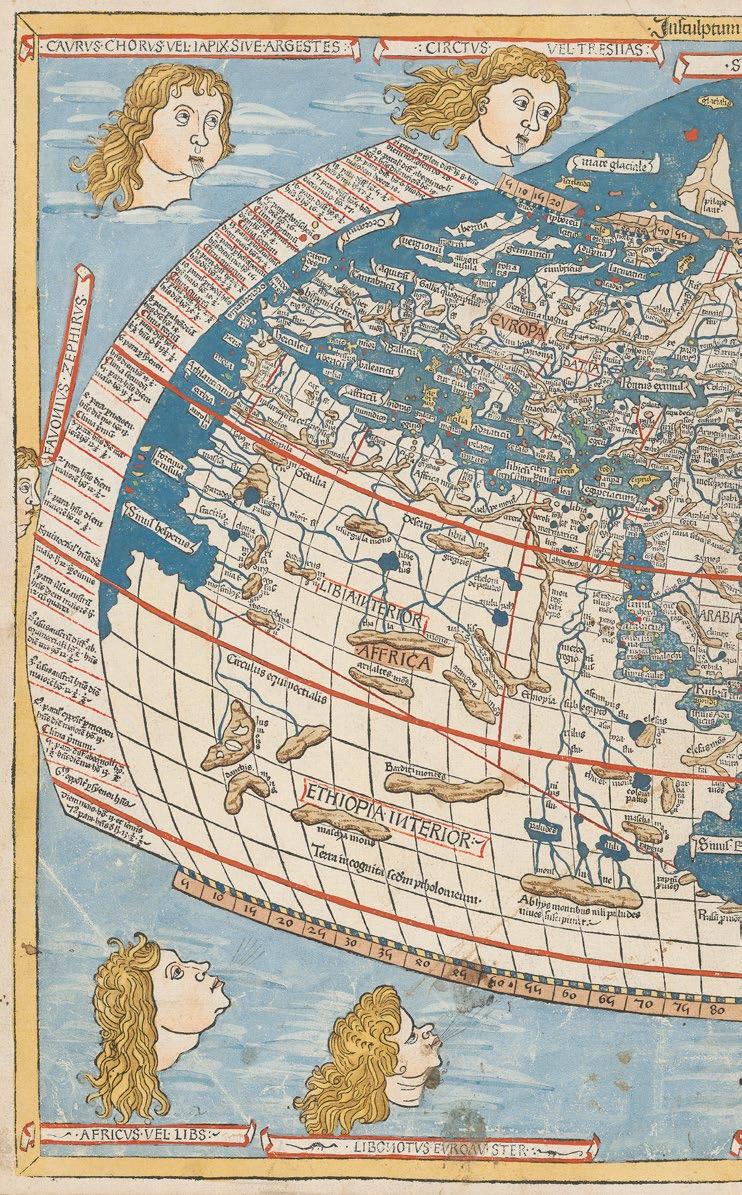

1.1 World map from Ptolemy’s Geografia, edited by Nicolaus Germanus, published by Leonhart Holle, Ulm, 1482

The rediscovery of Ptolemy’s work led to copies of his Geografia being spread throughout Europe. Following the invention of the art of printing, his treatise also became available as a printed book. Although Ptolemy represented something new to the Europeans of the 1400s, it quickly became clear that his knowledge was not complete. Northern Scandinavia, for example, is not included in his Geografia. So new information was added when the book was published in Ulm in 1482, such as the Scandinavian Peninsula to the world map, extending halfway beyond its top frame. The frame is the Arctic Circle, correctly placed at 66 degrees latitude.

For the astronomers of antiquity, the polar nights and midnight sun were a logical consequence of the spherical shape of the Earth. Since they knew the circumference of the Earth, they could calculate the placement of the Arctic Circle – even though they were not familiar with the countries located there. The 1482 edition was the first to place the correct countries under the Arctic Circle.

1.2 Map of the Nordic countries from Ptolemy’s Geografia, edited by Nicolaus Germanus, published by Leonhart Holle, Ulm, 1482

The editor of the 1482 edition supplemented Geografia with various regional maps of areas not mentioned by Ptolemy. These newly drawn maps were referred to as tabula novae, which means ‘new slates’. The map of the Nordic countries from 1482 – the first printed map of the Nordic countries – is one such map. In Norwegian map history, the year 1482 is therefore significant, as this was the first time that Norway appeared on a printed map.

On this map, Norway is depicted with fjords, mountains and islands and the Norwegian city names include Oslo, Stavanger, Bergen, Nidaros and Trondenes. Trondenes is located outside Harstad and was a chieftain’s farm during the Viking Period and a trading post and the religious centre of Northern Norway throughout the Late Middle Ages.

1.3 Ptolemy’s Almagest, published by Johannes Regiomontanus, Venice, 1496

Throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the geocentric worldview prevailed: the Earth was a sphere and the centre of the universe, with the sun, moon and planets orbiting around it. This worldview harmonised well with the Church’s representation of the world in which the Earth was the centre of God’s creation. The geocentric worldview is reflected in many illustrations in books from the 15th and 16th centuries, such as in this edition of Ptolemy’s astronomical manual Almagest from 1496.

In 1543, Copernicus asserted that it was the sun, not the Earth, which was the centre of the universe. Copernicus’ heliocentric model was not graciously received by the Church and his book was banned. A little less than a hundred years later, Galileo Galilei supported Copernicus’ view and was condemned to lifelong house arrest. But contrary to what many believe, no one has ever been condemned for claiming that the Earth is round, as this has been the prevailing view as far back as we have records.

1.4 Jean Sacrobosco’s Sphaera mundi, published by Bonetus Locatellus, Venice, 1490

The geocentric worldview was portrayed both in writing and in the form of models made of metal rings. These models were scientific tools and referred to as armillary spheres. The name originates from the Latin armilla, which means ‘armband’. Armillary spheres were astronomical instruments used to make calculations. Both the Chinese and the Greeks most likely made armillary spheres several hundred years before the start of the Common Era, but none of them have survived. The science of astronomy is depicted here as a woman called ‘Astronomia’. She is flanked by Urania, the Greek muse of astronomy, and Ptolemy, holding his book Geografia. Astronomia is holding both an armillary sphere and an astrolabe, a flat and portable version of the instrument.

1.5 Ptolemy’s Geografia, published by Girolamo Ruscelli, Venice, 1564

The Greeks knew that the Earth was round. To portray its spherical shape Ptolemy recommended drawing maps in conic

projection, which means tapered towards the top. Ptolemy also indicates latitude and longitude coordinates for 6,300 city names from the world known to the Greeks. But it was not Ptolemy who invented longitudes and latitudes, as Greek knowledge was based on Persian, Indian and Babylonian knowledge. It is not known exactly when the idea to divide the planet into longitudes and latitudes developed, as it was a long process with numerous dead ends and detours.

This 1564 edition of Ptolemy’s Geografia includes a pedagogical illustration in which the section of the planet covered by Ptolemy’s map is marked with longitudes.

1.6 “Tabula Moderna Prussie. Livonie, Norvegie et Gottie” from Ptolemy’s Geografia, published by Johann Reger, Ulm, 1486

The publisher of the 1482 edition of Ptolemy’s Geografia, Leonhart Holle, ran into financial problems and ended up selling the printing blocks to Johann Reger, who reprinted and re-published the work in 1486. The map of the Nordic countries in the two Ulm editions is virtually identical in both, yet with a significant difference. When Reger reprinted the map in 1486, he gave it a title. This title is used – albeit in ever shorter versions – for all maps of the Nordic countries in Ptolemy’s publications until the year 1541.

The Ulm maps were printed in black, so the maps that have colours, were hand-coloured. The bright blue colour is characteristic of the 1482 version, while brown is most common in the maps from the 1486 edition.

1.7 Map of the Nordic countries from Ptolemy’s Geografia, Ulm, 1482–1486

Johann Reger not only acquired the printing blocks, but also the printed stock from Holle. This copy is a hybrid: it was printed for the 1482 edition, but given the new 1486 title, written by hand.

1.8 “Tabula Moderna Prussie. Livonie, Norvegie et Gottie” from Ptolemy’s Geografia, published by Marco Beneventanus, Rome, 1507

The map of the Nordic countries in the Ulm editions established a precedent for the design of the map and it was not

until well into the 1500s that major changes and improvements were made. Until that time, all maps of the Nordic countries were found in Ptolemy’s publications or publications inspired by his work – all of which were based on the map of the Nordic countries in the Ulm editions.

This is the first map of the Nordic countries printed from an engraved copperplate, also known as copperplate printing. All previous maps were woodcuts, i.e. printed using carved wooden blocks.

1.9 “Tabula Moderna Norbegie et Gottie” from Ptolemy’s Geografia, ed. by Martin Waldseemüller, Strasbourg, 1513

The title of this map is based on the title of the map of the Nordic countries published in Ulm in 1486. However, the editor, Martin Waldseemüller, chose to omit Prøyssen and Livonia from the title. Livonia was a designation for an historic region that is today’s Latvia and Lithuania.

1.10 Map of Northern Europe from Hartmann Schedel’s Liber Chronicarum, Nuremberg, 1493

The Scandinavian Peninsula contains few place names. Instead, the cartographer has chosen to include two words associated with the north: wildlappen, often used in reference to the Sami people, and mitnacht, which designates the Polar nights.

1.11 Map of Northern Europe from Johann Schönsperger’s Liber Chronicarum, Augsburg, (1496) 1497

Hartmann Schedel’s historical work was so popular that Johann Schönsperger published an abridged version as early as 1496. The maps are printed from woodcuts in both Schedel’s original publication and Schönsperger’s version. In Schedel’s edition, all place names are carved into the wood blocks, while Schönsperger used movable type.

1.12 World map in Hartmann Schedel’s Liber Chronicarum, Nuremberg, 1493

The Medieval Christian world map showed the world in both time and space. Jerusalem was at the centre, surrounded by pictures portraying Biblical events in the cities where they took place. These were holy places where in the deepest sense the events were still present.

Ptolemaic geography did not have a centre, only a mathematical system of coordinates. The geography no longer carried religious meaning, but many maps from the 1400s and 1500s could still have space for time. On this map from Hartmann Schedel’s extensive chronicle of the world, we see Noah’s sons Sem, Kam and Jafet encircling the world they had populated after the flood. Readers interested in the stories from the Christian Medieval maps could read them in the book. The map only showed the world portrayed by Ptolemy, and Northern Scandinavia is not included. Southern Sweden is only barely visible as a small island called Suena.

1.13 “Tab Nova Nor & Goti” from Ptolemy’s Geografia, published by Laurenz Fries, Strasbourg, 1522

Since the Ulm publication in 1482, it had become customary to place Greenland north of Norway, attached to Northern Scandinavia by a land bridge. On Laurenz Fries’ map, a text is printed on this land bridge in Latin which tells that the regions shown on the map “... are rich in precious furs that are transported to western ports. [...] The faces of the wild inhabitants resemble the Samoyed.” Samoyed is the name of an ethnic group of indigenous peoples who live in Siberia and Fries is probably referring to the Sami.

1.14 “Tab Nova Nor & Goti” from Ptolemy’s Geografia. Laurenz Fries’ edition published by Michael Servetus, Vienna, 1541

After Laurenz Fries’ death, Michael Servetus re-published Fries’ edition of Ptolemy’s work in 1535 and 1541. Servetus was a physician who had also studied theology, law and several languages. He was a Protestant and condemned by the Catholic authorities in France, so he fled to Calvinist Geneva, where his rejection of the Trinity was also poorly received. On orders from the Protestant reformer Jean Calvin, Servetus was burned at the stake for heresy in Geneva in 1553. The two publications of Fries’ Ptolemy edition contributed to the case against him. One of the charges was that he had written on the back of the map of the Holy Land that the land was largely barren. But this comment had been included in the book since Fries’ first edition in 1522 and was not written by Servetus. Many of Servetus’ books were burned together with him, so maps from these books are relatively rare.

The notion that the world was previously believed to be flat is a modern myth that originated around the year 1800. This myth reflects both the belief of that time that the Middle Ages were ‘dark’ and unenlightened and the hero worship of Columbus.

In Columbus’ time, the fact that the Earth is round had served as a presupposition for astronomy, navigation and the Church’s worldview for more than a thousand years. So whether or not the Earth was round or flat was not an issue prior to Columbus’ journey. Uncertainty about Columbus’ plans pertained to the length of his journey, as no one had ever sailed so far across open sea and the fear was that he would run out of food and water. Nor were there any historical sources indicating that the shape of the planet had been up for debate in other epochs. There are only two historical ‘flat earthers’ known – both lived in late Antiquity and neither were influential at their time.

Knowledge of the spherical shape of the planet is reflected in old world maps that depict the Earth as round, albeit in various ways.

Cornelis de Jode: “Hemispherium ab aequinoctiali linea ad circulum poli artici. Hemispherium ab aequi noctiali linea ad circulum poli antarctici”, Antwerp, 1593

2.1 “Orbis typus universalis …” from Ptolemy’s Geografia, edited by Martin Waldseemüller, Strasbourg, 1513

In 1507, Martin Waldseemüller published the oldest known map using the name America. The name was chosen as a tribute to Amerigo Vespucci, the first to claim that the newly discovered country was its own continent. In retrospect, Waldseemüller must have had his doubts about this decision since, on later maps, he calls the continent Terra Incognita (‘unknown land’) or omits the name altogether, as in this case. However, the name America had already become associated with the land mass.

A thousand copies of the world map from 1507 were printed, but only one has survived. It was found at Wolfegg Castle in Germany in 1901 and purchased by the American national library for ten million dollars in 2003. During a formal handover ceremony in 2007, Angela Merkel declared that U.S. contribution to the reconstruction of Germany after World War II and the subsequent friendship between the two countries was the reason that Germany approved the export of the map to the United States.

2.2 Gerard de Jode: “Vniversi orbis sev terreni globi in plano effigies”, Antwerp, 1578

The title states that the map illustrates the Earth as a flat surface, depicted as a person. With a bit of imagination, the map resembles a face, thus visualizing the English expression ‘the face of the Earth’.

2.3 Nina Brown Baker: Historien om Christofer Columbus, Oslo (1952) 1991

Washington Irving’s Columbus biography from 1828 is considered one of the main sources of the myth that the Earth was once believed to be flat. The book has some of the same intrigue found in today’s Hollywood action films: Columbus is the hero, the underdog and the only one who understands that the Earth is round – making it possible to reach India by sailing westward. At the same time, Church scholars are given the role of narrow-minded, old-fashioned men who believe that the Earth is flat. The perception that most people in Columbus’ time believed the Earth to be flat, lingers on, as in Nina Brown Baker’s children’s book about Columbus.

2.4

Johann Ruysch: “Vniversalior Cogniti Orbis Tabula” in Ptolemy’s Geografia, edited by Evangelista Tosinus, Rome, 1508

In the Ptolemy editions, it gradually became commonplace to include both a contemporary world map and a map by Ptolemy that includes neither America nor the Scandinavian Peninsula. This is a modern world map from 1508. At the time, the High North had yet to be explored and it was not known how the various regions were connected. Unlike the Ulm maps, where Greenland is linked to Northern Scandinavia, Johann Ruysch chose to connect Greenland to Asia.

Atlases of the sea were popular in the Mediterranean region in the 1400 and 1500s, when ships were the most important means of transport, making them necessary for most trading activities. Isolario was a book of islands published four times between 1528 and 1547, intended as an illustrated guide for sailors. It describes island names, folklore, cultures, climate and history. In addition to island maps, Isolario also contains a world map that shows the Earth as a flattened sphere, a map of Europe and a map of the High North. These were intended as overview maps to aid the reader.

The back of the map of the North contains a map of North America – the first printed map of America. The Azores are also depicted, as well as Asmaide and Brazil, two mythological islands in the Atlantic. The latter originates from Irish myths about an island covered in fog except for one day every seven years, when the island became visible, but could still not be reached.

2.6 “Typus orbis descriptione Ptolemæi” from Ptolemy’s

Geografia, Laurenz Fries’ edition, published by Michael Servetus, Vienna, 1541

Between 1522 and 1541, Laurenz Fries’ version of Ptolemy’s Geografia was published in no fewer than four editions. In the mid-1500s, the exploration and mapping of America were well underway and Ptolemy’s maps – which did not include America – were ultimately considered historical maps, as they showed knowledge of the world in Ptolemy’s day and age. This is clear from the title of the map, which translates to ‘The world according to Ptolemy’.

2.7

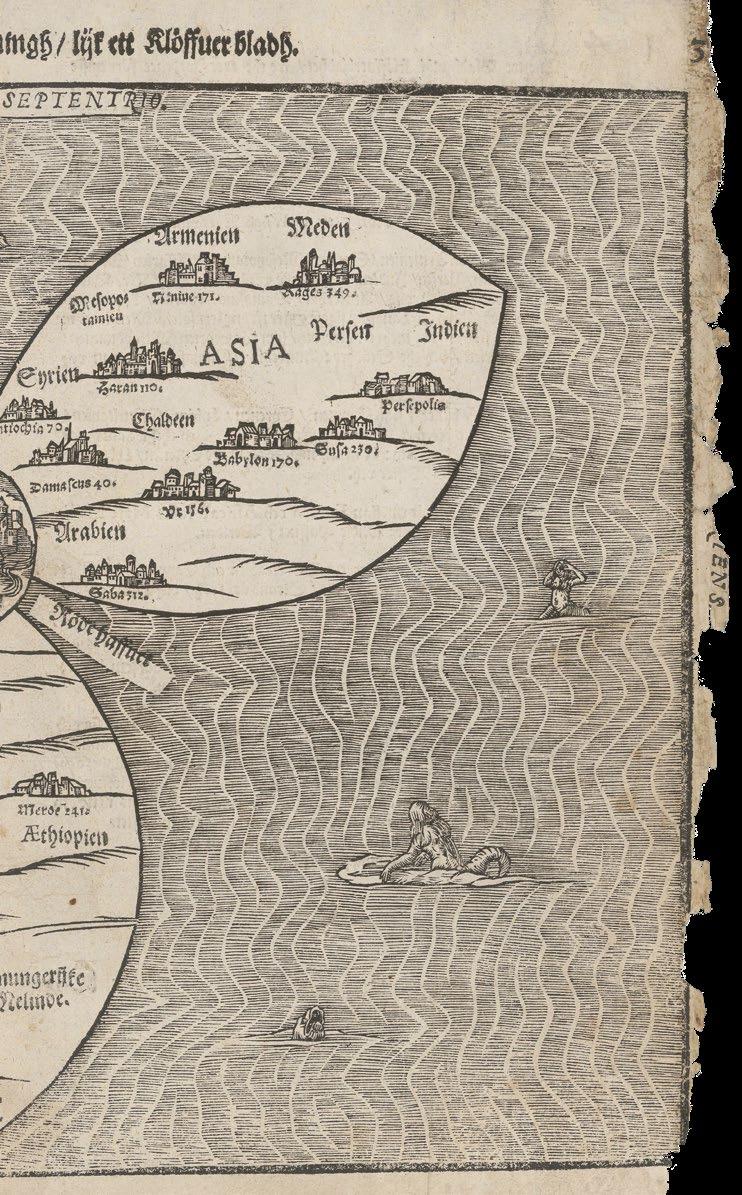

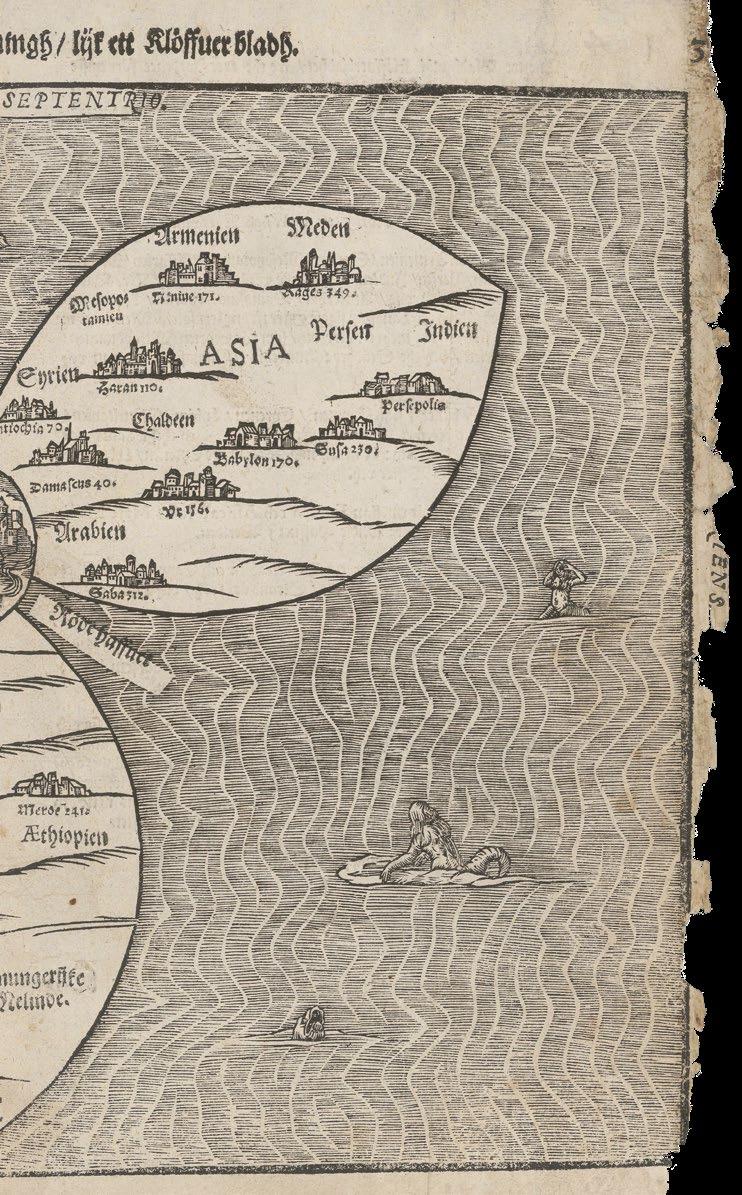

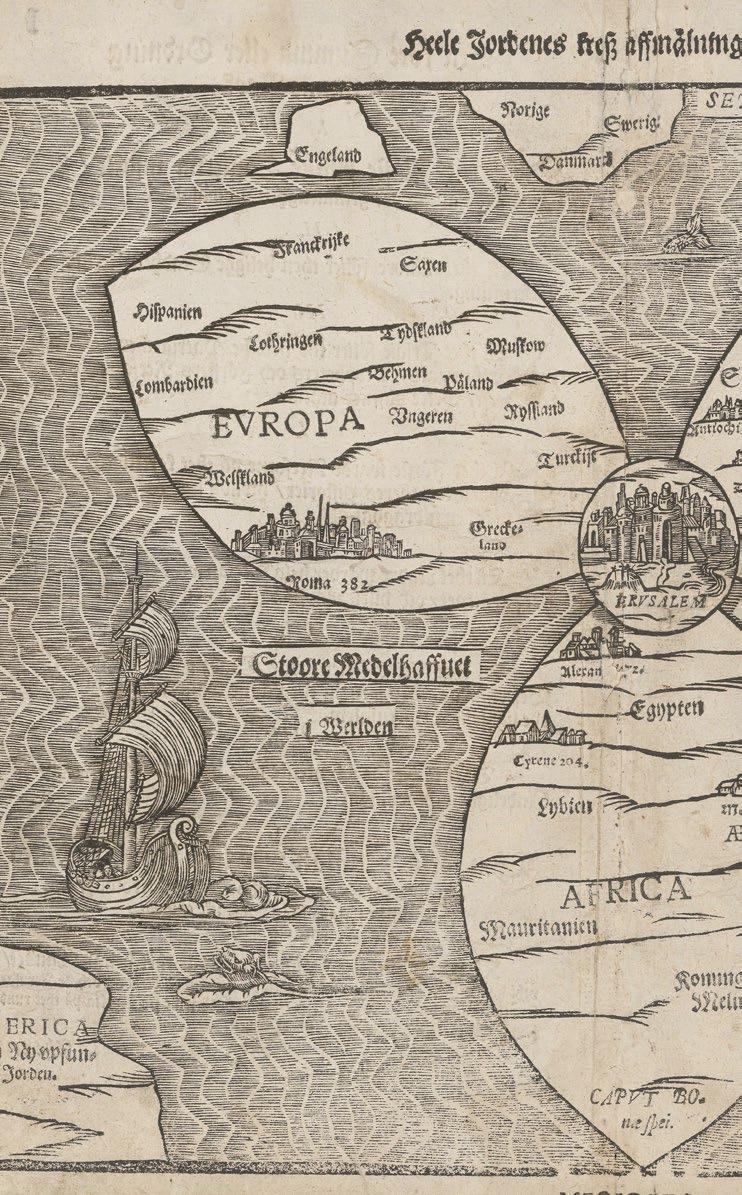

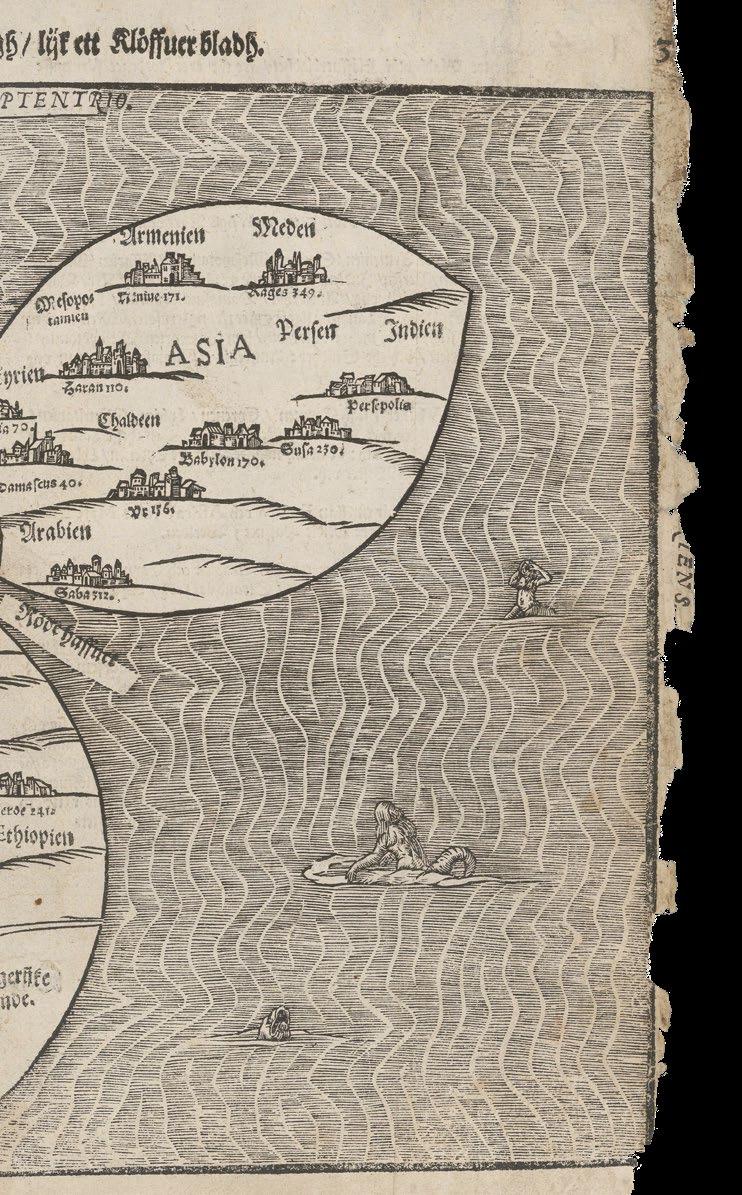

Heinrich Bünting: “Heele Jordenes kretz affmålningh

liik ett Klöffuerbladh” from Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae, Stockholm, 1595

Heinrich Bünting was a professor of Theology in Hannover who published the book Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae in 1581, a geographical account of the Holy Land, seen through the journeys of biblical characters. The book quickly became popular and was translated into several languages.

The map from Bünting’s book shows the three parts of the ancient world – Europe, Asia and Africa – connected by Jerusalem, the centre of Christianity. Bünting combines this medieval symbolic geography with the new Ptolemaic geography. America is shown at the bottom left corner, while Scandinavia is placed at the very top in the north, separate from Europe. The intention is probably to show that the northern countries extend beyond the Arctic Circle, Ptolemy’s outer geographical limit.

This Swedish edition differs from the original in that Norway is also named as part of Scandinavia.

2.8 Illustration for the Book of Daniel in the Gustav Vasa Bible, Uppsala, 1541

This map originates from the Gustav Vasa Swedish version of the Bible from 1541. It shows one of the apocalyptic dreams of the prophet Daniel, portrayed in the seventh chapter of the Book of Daniel, where four beasts ascend from the sea to rule the world. Daniel’s dreams were of major importance for the writing of history in the Middle Ages, especially since they appeared to explain world history as a series of epochs. The map shows the world without America, which was unknown to Daniel.

The picture was printed for the first time in 1530 in Luther’s pamphlet Eine Heerpriedigt wider den Turcken, “On War Against the Turk”, published in Wittenberg by Hans Lufft. In it Luther links Daniel’s dream to Islam and the threat from the Ottoman Empire. A powerful Ottoman army had besieged Vienna only one year earlier. The army is shown at the centre of the map, hidden in the mountains of West Asia.

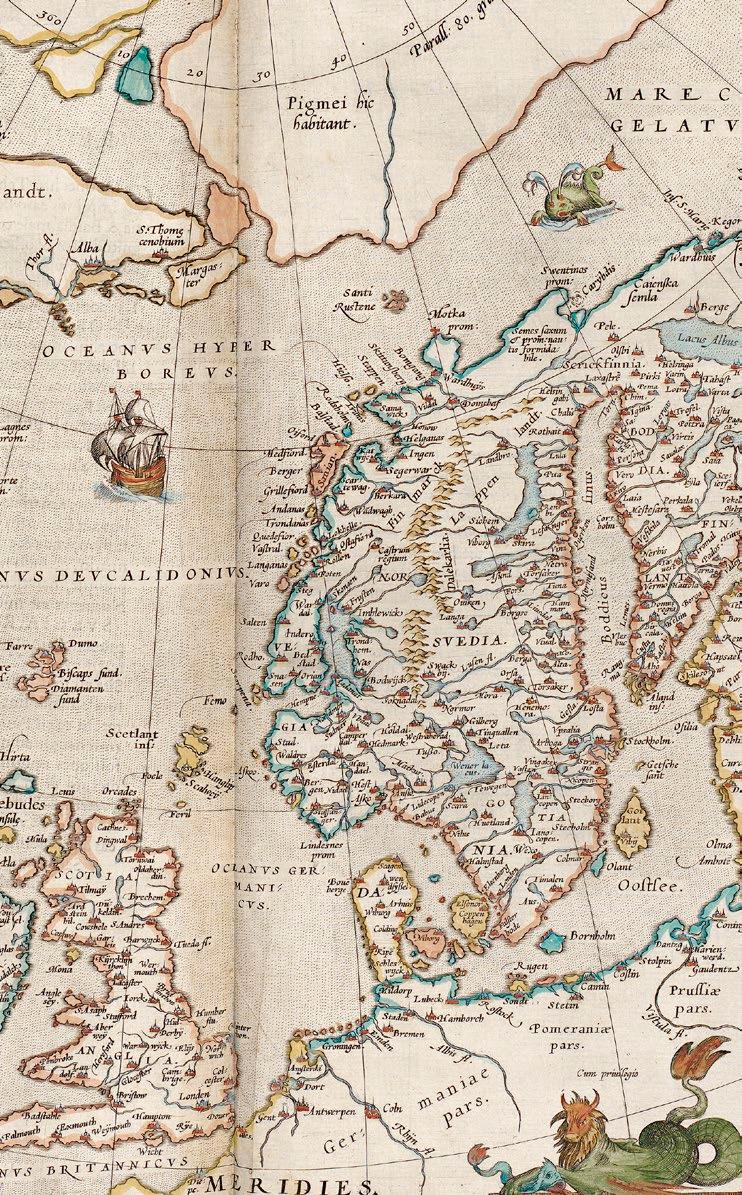

2.9 Cornelis de Jode: “Hemispherium ab aequinoctiali linea ad circulum poli artici. Hemispherium ab aequi noctiali linea ad circulum poli antarctici”, Antwerp, 1593

Here the planet is divided at the equator, so that the map shows the northern and southern hemispheres, with the North Pole and South Pole at the respective centres. This manner of portraying the planet is called double hemisphere polar projection.

The Great Bear constellation contains the smaller Big Dipper constellation, which is used to point out the North Star. The Greek word for ‘bear’ is arktikos. The area around the North Pole was named after the bear and therefore called the Arctic. The names Arctic and Antarctic reflect knowledge of the spherical shape of the Earth: Arctic in the north and the opposite – anti-Arctic, i.e. Antarctic – in the south.

2.10 World map in Ptolemy’s Geografia, published by Bernardus Sylvanus, Venice, 1511

This world map from 1511 is the first known map produced using heart projection. Multicoloured printing of maps was not common until the 19th century. Most coloured maps until this time were hand-coloured. Attempts were made to create two and three-coloured printed maps in the early 1500s, but the colours were used only on lines and letters, not surfaces. Multicoloured printing was technically complex and therefore expensive, so most printers who attempted it ultimately gave up. In the 1511 edition of Ptolemy’s Geografia, the maps are printed in black and red.

2.11 “Orbis descriptio” in Ptolemy’s Geografia, published by Girolamo Ruscelli, Venice, 1574

In geometry, a circle is divided into 360 degrees. The Earth is therefore also divided into 360 degrees of longitude. The word ‘geometry’ originates from Greek, with geo meaning ‘earth’ and metria ‘measurement’. In other words, geometry means ‘measurement of the earth’.

But where on the planet do you start counting to these 360 degrees? In other words, where is 0 degrees longitude? The westernmost known region in Antiquity – Ptolemy’s time – was the Canary Islands and, since ancient times, this is

where the 0 degree of longitude, called the Prime Meridian, was placed. The title tells us that the map is a description of the Earth. It divides the planet into a western and eastern hemisphere, with the Prime Meridian at the Canary Islands.

Antonio Salamanca’s world map is a combination of double hemisphere and heart projection, referred to as double heart projection.

The number 360 can be seen at the bottom of the left half and can be followed northwards through the Canary Islands. In other words, the map also uses the Canary Islands as the Prime Meridian.

Various Prime Meridians were established later on. Several maps use the Cape Verde islands, while others designate the Azores and the English eventually came to use Greenwich. At the International Meridian Conference in Washington in 1884, Greenwich was established once and for all as the official Prime Meridian.

Christiania also joined the battle to be the world’s starting point. In the late 1820s, mathematician and astronomer Christopher Hansteen established a Prime Meridian with its starting point at the Observatory on Solli plass. It was called the Christiania Prime Meridian. Hansteen established the position of Christiania by calculating the exact location of the Observatory. Prior to his painstaking efforts, neither Christiania nor Norway had been correctly positioned on the map.

This copy has been Hansteen’s working map, since the notes are in his handwriting. Before the Observatory was built, Hansteen lived at Madame Niemann’s property in Pilestredet. At the bottom, he has converted a minute of arc into the Norwegian ell, which Hagelstam’s maps also indicate. Hansteen used the same ratios to convert the distance from Gamle Aker Church, the Observatory and Oslo Cathedral and to Madam Niemann’s pavilion, i.e. the pavilion in his own garden.

The standard textbook in astronomy for three hundred years was De sphaera, written in the early 1200s by Jean Sacrobosco, a professor of Astronomy at the University of Paris. The word ‘sphaera’ comes from the Greek word sphaira, which means ‘ball’ or ‘globe’, and Sacrobosco’s book contains numerous illustrations that show how to navigate the round globe.

Sacrobosco’s book was written by hand, and copies spread throughout much of Europe. After the art of printing was invented in the 1450s, a printed edition of De sphaera was quickly published, in 1472. Over the next two hundred years, more than eighty editions of Sacrobosco’s book were published under different titles and supplemented with the various publishers’ explanations and comments. Many books on astronomy and navigation also include illustrations based on Sacrobosco’s work.

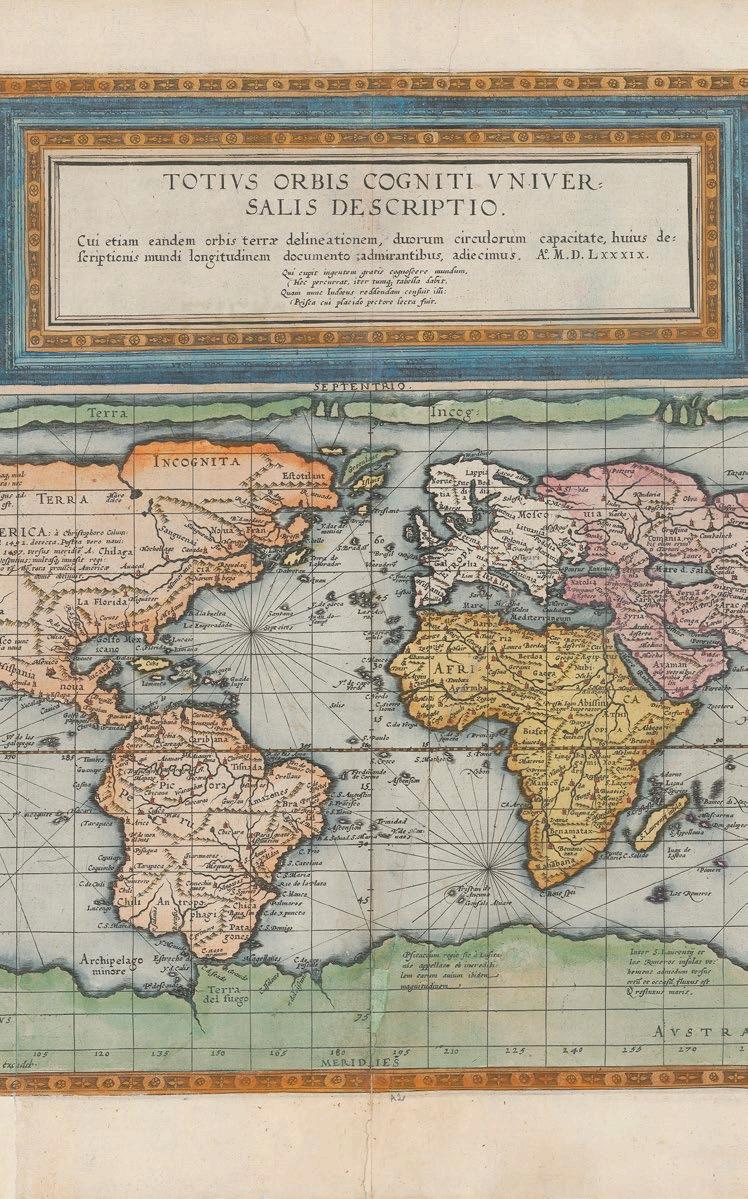

Cornelis de Jode: “Totius Orbis Cogniti Universalis Descriptio”, Antwerp, 1589

In 1569, Gerard Mercator introduced a map projection which would later be called the Mercator projection. It is still commonly used in a modernised version. In the Mercator projection, the degrees of longitude do not meet at the poles, but are linear horizontally, so that the degrees of longitude and latitude create a right-angled grid. It is easier to navigate using a map in the Mercator projection than a map on which the degrees of longitude are curved and meet at the top and bottom. Simplifying navigation was indeed Mercator’s intention with the development of this type of projection. However, maps in this projection make the northern and southern areas appear disproportionately large.

Willem Blaeu’s world map is made in Mercator projection and surrounded by illustrations, with allegories of the moon and the known planets at the top. The planets beyond Saturn could only be seen with a telescope, which is why they were not discovered until after this map was made. The order shows the geocentric worldview, which places the sun between Venus and Mars. We now know that this is where the Earth is located. The four elements are shown on the left and the four seasons on the right.

At the bottom are the Seven Wonders of the World, which were tourist attractions even in Antiquity.

From the left: the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Mausoleum at Halikarnassos, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia and the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Blaeu chose to use the names of the Roman gods instead of the Greek ones and the Temple of Artemis is therefore presented as the Temple of Diana and Zeus as Jupiter.

The majority of the old maps that have survived until our own time were precious objects in their own right. They were not

made to be brought for journeys, but for study and reflection indoors. An exception were the navigation books, which served as manuals for sailors. Lucas Waghenaer’s books and subsequent publications also included maps.

Lucas Waghenaer, Willem Blaeu and Jacob Colom all published such books. The ships of the Dutch East India Company always carried one of Blaeu’s navigation books on board. Blaeu and Colom were direct competitors and their books were conspicuously similar, usually with a title page showing men teaching each other the art of navigation and map drawing. The scene here at sea refers to Exodus 13, where the Israelites received God’s guidance in the form of a column of fire. Here Colom was also referring to himself: his name means ‘column’.

Oronce Fine was a Professor of Mathematics at the Collège Royal in Paris and editor of publications of the works of Euclid and Sacrobosco. Fine also wrote books about astronomy, cosmography and mathematics, as well as doing the illustrations in them. The illustration with the ship was inspired by Sacrobosco and shows how the Earth’s curvature makes it possible to see only what is above the horizon.

Robert Dudley was the illegitimate son of the Earl of Leicester, a favourite of Queen Elizabeth. Dudley was a scientist, mathematician, ship architect and navigator – not to mention an adventurer. At the age of 20, he joined an expedition to the West Indies, where he combined voyages of discovery with the plundering of Spanish ships. Shortly after returning home, he fell out of favour and was exiled abroad. Dudley moved to Florence, where he spent thirty years in the service of the Grand Duke of Tuscany. His sea atlas Dell’ Arcano del Mare – “Mysteries of the Sea” – was published in 1646. In addition to nautical charts, the sea atlas contains texts on shipping, with such topics as maritime law, shipbuilding, navigation and astronomy.

Dell’ Arcano del Mare is the first sea atlas in which all maps are portrayed in Mercator projection. Unlike many of his fellow cartographers, Dudley made the maps from scratch, which is why they are not the most accurate ones.

by Valk and Schenk, Amsterdam,

In Cicero’s book The Dream of Scipio, written in the 50s BCE, the world is described as a sphere divided into climate zones. Cicero based his work on Aristotle, who established five climate zones: the equatorial zone, which was hot and uninhabitable; the zones north and south of the equatorial zone, which were temperate; and the zones in the north and south, which were so cold and inhospitable that they were called zona frigida.

In the 400s, Macrobius wrote a commentary on The Dream of Scipio, illustrated with maps of the climate zones. Macrobius’ work had a profound influence and was read and copied for more than a thousand years. Macrobius’ maps do not often show coastlines, only a round planet schematically divided into climate zones.

Cellarius’ cosmic atlas reflects the 17th century’s knowledge of the universe and the Earth, including this map with the climate zones of the eastern hemisphere. When the map was made, trading had become global and the division into climate zones was therefore no longer a theoretical model, but provided practical information.

At the end of the 1500s, the Dutch Republic developed into a major cultural and economic power. In the 1590s, three Dutch attempts were made to find the Arctic Northeast Passage, a navigable route north of Scandinavia and Russia and to the East. This would make it possible to avoid the long route around Africa. Today, we refer to these three expeditions as the Barents expeditions, after the navigator and cartographer Willem Barents. Barents was a key player in the planning and execution of all three expeditions and the leader of the third.

Gerrit de Veer took part in the second and third expeditions and wrote a diary of both, supplemented with information from the first journey. The Barents expeditions were dramatic, particularly the last one, when the ship froze in the ice on the northeastern side of Novaya Zemlya and the crew had to spend the winter in a house made of driftwood and planks from the ship. Of the crew of seventeen, twelve men survived the hardships and returned to Amsterdam. Willem Barents died during the return journey.

De Veers’ travel diary was published as early as 1598, the year after the crew from the final expedition returned home. The book became a bestseller and was published in several languages.

4.1 Lucas Waghenaer: “Generale Paschaerte van Europa” from Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, Leiden, 1584–1585

This map is dated 1583 and was first published in Lucas Waghenaer’s Spieghel der Zeevaerdt in 1584–1585. 1583 is also the year Dutch merchant ships began sailing regularly to Arkhangelsk in the White Sea. The sea and coast northeast of Norway were still considered an unknown area when this map was made, and Waghenaer did not include the White Sea, as the map only extends to the middle of the Kola Peninsula. The areas that were to be sailed through by the Barents expeditions were therefore – literally – beyond the borders of the map, i.e. outside the world they knew.

4.2 Petrus Plancius: “Europam ab Asia & Africa segregant Mare mediterraneum”, Amsterdam, 1594

The small map at the top right is a detailed map of Novaya Zemlya. The text under the map states that in July 1594, ships travelled to this area by order of the Dutch authorities – but that they had yet to return. The ships referred to here are the first of the three Barents expeditions.

4.3 Map of the Nordic countries in Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s travelogue Voyagie, ofte Schip-Vaert, Franeker, 1601

The first Barents expedition in 1594 managed to navigate to the Kara Sea through the strait separating Novaya Zemlya from the mainland. The dotted line shows the route they sailed.

Their success was met with tremendous enthusiasm in the Netherlands and, in 1595, a new expedition with seven ships was prepared. The ships were loaded with merchandise, and craftsmen such as goldsmiths and diamond cutters were also on board. The second expedition had a clear economic goal. The Dutch authorities sent commercial agents who were to establish trade offices and make trade agreements. Jan Huygen van Linschoten was one of these agents. Once again, the expedition succeeded in navigating to the Kara Sea, but due to the ice conditions, they were unable to sail further eastwards and had to turn around without having achieved their goal.

4.4 Gerrit de Veer’s diary, published by Theodore de Bry, Frankfurt, 1601

On the first expedition in 1594, the Dutch had their first encounter with polar bears. The men did not realise just how strong polar bears are and believed they could capture one alive by hauling it in with a rope. But the polar bear responded far more offensively than expected and climbed onto the boat. The men had a stroke of luck when the rope they managed to get around the polar bear’s neck became stuck in the rudder and the bear fainted halfway up the side of the boat. It could not have been particularly tempting to keep the polar bear alive, since only the bearskin reached Amsterdam.

4.5 Gerard Mercator: “Septentrionalium Terrarum description” from Atlas sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura, Duisburg, (1595) 1602

Many of the maps from the 1500s show a North Pole continent divided into four sections. The origin of this notion is a now lost work from the 1300s called Inventio fortunata, written by an author whose name we no longer know. Inventio fortunata is only known from Ruysch’ world map from 1508, which mentions it in a short text placed at 90 degrees latitude, and from Gerard Mercator’s correspondence with John Dee, an adviser to Elizabeth I of England. Ruysch’ map can be seen in Theme 2 of the exhibition, Variants of the world.

The first known map of the North Pole shows a North Pole continent divided into four sections. It is inserted at the bottom corner of Mercator’s world map from 1569. Only a few copies of this map have survived. When Mercator made the North Pole map for his atlas, he based it on this insert map.

4.6 Gerard Mercator: “Septentrionalium Terrarum descriptio” from Atlas sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura, Duisburg, (1595) 1628

Spitsbergen and Bear Island were discovered by Willem Barents in 1596, which is why they are not included on Gerard Mercator’s North Pole map from 1595. After Mercator’s death, cartographer Jodocus Hondius bought Mercator’s printing plates and made changes to the plate for the North Pole map, removing sections of the North Pole continent to make room

to engrave Spitsbergen and Bear Island. They are called t’Nieuland – ‘The new land’ – and Beeren eylandt – ‘Bear Island’ on the map.

Hondius also upgraded Novaya Zemlya with hard-earned knowledge from the Barents expeditions. Barents’ winter camp on Novaya Zemlya is referred to on the map as t’ Behouden huys, ‘the safe house’. This information is found on maps for almost the rest of the 1600s. Hondius published the first of his 15 editions of Mercator’s atlas in 1606 with the updated version of the North Pole map.

4.7 Lucas Waghenaer: “Universe Europeæ Maritime” from Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, Antwerp, (1591) 1596

In the early 1590s, Dutch trade was in full swing in Finnmark, on the Kola Peninsula and in the White Sea. Lucas’ Waghenaer’s map of Europe from 1583 does not show the White Sea, which is why it was replaced in 1591 with an updated map of Europe that extended further east, so as to include the new and important northernmost trading areas. Dutch maps from the 1500s were a consequence of trade conducted by the Dutch along the coast, which is why they provide detailed information on coastal areas and little information on inland areas. The maps show places to stop during transport, not unlike today’s underground maps.

4.8 Cornelis Doedsz: “Tabula Hydrographica”, published by Claes Jansz Visscher, Amsterdam, (1589) 1610

The first edition of Cornelis Doedsz’ map was published in 1589 and only one copy has survived, bound in a copy of Lucas Waghenaer’s Spieghel der Zeevaerdt from 1596. The book is owned by the British Library. The map shown here is one of two known copies from the second edition from 1610.

As the Dutch became better acquainted with the area around and east of the North Cape, geographic knowledge developed quickly and the improvements from Waghenaer’s map of Europe from 1583 to Dodsz’ are clear. As the title indicates, “Tabula Hydrographica” is a nautical chart. The chart was the best of its time and shows Europe’s northern coastal areas far more accurately than previous charts.

4.9 “Barents Map”, published by Cornelis Claesz, Amsterdam, 1598

The survivors from the winter on Novaya Zemlya brought Barents’ map sketches back to the Netherlands. The printed result is commonly called the “Barents Map”. The expedition discovered Svalbard and Bear Island and the “Barents Map” is the first to show these islands. The dotted line shows the route sailed by the third expedition. The map also shows the winter camp on Novaya Zemlya.

Barents was among those who believed that the North Pole continent did not exist. Pack ice was considered a coastal phenomenon and Barents argued as follows. If the North Pole were not a continent, there would be no pack ice north of Novaya Zemlya, but open navigable sea. Even though Barents’ ship became frozen in the ice, the expedition contributed to the demise of the notion of a North Pole continent. Most maps made after the “Barents Map” show the Arctic as an open sea. The Barents expeditions did not find a northern sea route to the East and, in that sense they were unsuccessful, but they contributed to better maps and greater knowledge of the High North.

4.10 Gerrit de Veer’s travel diary, published by Cornelis Claesz, Amsterdam, 1600

After a lengthy debate, the Dutch authorities decided against sending a third expedition. The City Council of Amsterdam was trading independently at this time and sent off two ships in 1596, with Willem Barents as the expedition leader. All three expeditions were continuously exposed to polar bear attacks. Gerrit de Veer’s diary mentions numerous encounters. On 17 June 1596, de Veer writes:

“With two boats full of people, we fought for a very long time and nearly destroyed all our weapons before we managed to overpower the bear. We called the island close to where this occurred Beyren Eylandt.”

In other words, this is the bear which gave name to Bear Island.

After the discovery of Svalbard and Bear Island, only Barents’ ship sailed on. The aim was to reach the East by

sailing north of Novaya Zemlya. However, the ship became trapped in the pack ice on the east side of Novaya Zemlya in August 1596.

4.11 Gerrit de Veer’s travel diary, published by Levinus Hulsius, Nuremburg, 1602

Willem Barents’ crew built a house on Novaya Zemlya, but the chimney was so ineffective and the smoke was so bothersome that the men sometimes did not light a fire. De Veer writes that this resulted in a “... two-finger thick layer of ice on the inside walls and as much even in the berths where we slept”. They even heated up the ship’s cannonballs on the fire and used them to warm their beds.

4.12 Map of Novaya Zemlya in Gerrit de Veers’ travel diary, published by Cornelis Claesz, Amsterdam, 1598

This is the first map of Novaya Zemlya drawn by someone who had actually been on the northern tip of the island. The dotted line shows the route sailed by the crew – in two small open boats – from the winter camp they had built to the trading outpost Kola in the Murmansk Fjord. Barents died during the return journey, probably of scurvy, and he is buried somewhere along the coast of Novaya Zemlya. Of the crew of seventeen, twelve men survived the hardships and returned to Amsterdam.

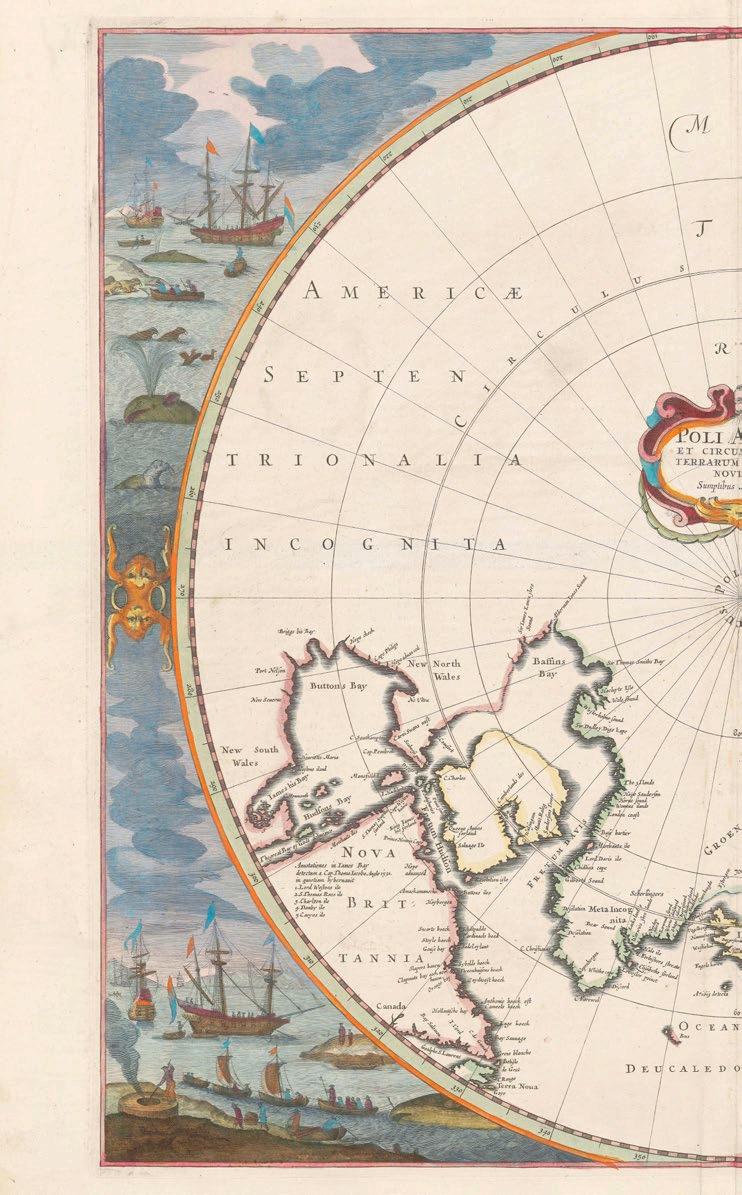

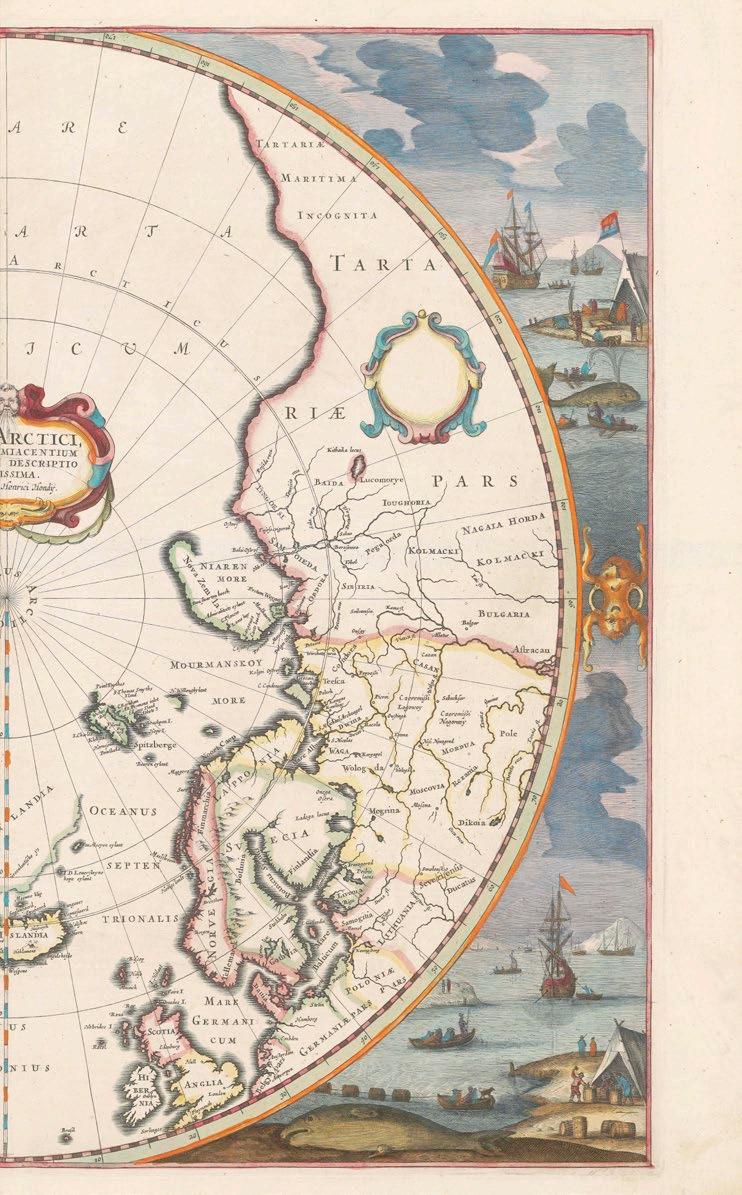

4.13 Henricus Hondius: “Poli Arctici, et Circumiacentium

Terrarum Descriptio Novissima”, Amsterdam, 1636

After the third Barents expedition’s discovery of Svalbard in 1596, it became clear that there were large populations of seals, whales and walruses around the archipelago. Systematic whaling at Svalbard began in 1612. Whales could be used for a variety of purposes. Whalebone was used to make parasols and corset staves and whale blubber was boiled into oil for use in lamps. This oil was also an ingredient in soap production and in preparation processes for textiles and leather. The boiling of oil took place out in the open at the whaling stations on Svalbard. By the 1600s, the idea of a North Pole continent divided into four quarters had been abandoned, and the North Pole is consequently shown here as open ocean.

4.14 Map of Spitsbergen from Samuel Purchas’ Purchas his pilgrimage: or Relations of the world and the religions observed in all ages and places discovered, from the creation unto this present, London, 1625

The English priest Samuel Purchas was an avid collector of travel diaries, which he published as a series of ‘pilgrimage travels’ between 1613 and 1625. Together they comprised a large illustrated account of the diversity of creation, everywhere and at all times. This map is from Purchas’ last book and is equipped with images of hunting and whaling. The work of creation was considered to be at the disposal of mankind. Several later cartographers based their work on Purchas, but corrected an obvious mistake. Purchas stated on the map that it showed Greenland, but this is of course not the case. Purchas claimed that the model for the map was drawn by the whaler Thomas Edge. The third largest island in the Svalbard archipelago is named Edge Island after him, but it is not connected to Spitsbergen as shown here.

4.15 Illustration in Cornelis Gijsbertsz Zorgdrager’s

Histoire des pêches: des découvertes et des établissemens des hollandois dans les mers du nord, Paris in the year IX [1800/1801]

Beginning in 1690, Cornelis Gijsbertsz Zorgdrager sailed for many years as the captain of Dutch whaling ships in the oceans around Greenland. Experience taught him that much of what was heard and read about whaling and the High North was incidental and unreliable. This was his claim in his book on whaling, published for the first time in 1720. There he presented knowledge he could vouch for personally, together with simple and accurate maps without sea monsters, but with spectacular pictures of a perilous existence – which could, for example, make it necessary to fight bears with a knife.

Zorgdrager’s book was a lasting success and was translated into several languages. This French edition was published in the year IX according to the French Revolutionary calendar, i.e. 1800–1801.

The great sea voyages in the late 1400s – like the discovery of America and the rounding of the southern tip of Africa – showed that the world encompassed far more than the Europeans had believed. In addition, regions that they had only heard about in the past were now more easily accessible. This led to an increased need for descriptions of sailing routes in new areas and marked the start of the systematic mapping of the world.

Large scale map production was also a result of the art of printing and, in the case of Norway, a consequence of the blooming of Dutch trade and the accompanying production of printed maps at the end of the 1500s. Dutch merchants traded along the Norwegian coast and shared geographic information on arriving home. In other words, Dutch cartographers did not travel to Norway to map the country, but for reasons of trade. Trade was conducted by ship, so the Dutch focused on the coast and not the inland areas. This is clearly reflected in the maps, which primarily contain coastal names.

Johannes van Keulen: “Paskaart van de Kust van Noorwegen Beginnende van de Wtweer Klippen tot aan Swartenos …”, Amsterdam, approx. 1685

In 1584–1585, what is considered the world’s first printed sea atlas was published: the Dutchman Lucas Waghenaer’s Spieghel der Zeevaert (“Mirror of Navigation”). This sea atlas contains a map of Europe and 44 maps of European coastal areas, three of which show the coast from Jæren to Båhuslen. These were the first local maps of the Norwegian coast and show places that were important outports at the time or small, flourishing trading posts. The sea atlas also contains both descriptions of sailing routes and drawings of the coast as seen from the sea. These drawings provided sailing marks and checkpoints along the way.

Waghenaer’s sea atlas was a resounding success and updated, revised and expanded versions were published in Latin, French and German, in addition to Dutch, over the next thirty years. The city names and information on Waghenaer’s map were used repeatedly by numerous other cartographers and, until the mid1700s, sea atlases were often called waggoner after him.

5.1 Lucas Waghenaer: “Hydrographica Septentrionalis

Norvegiæ partis descriptio …” from Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, Leiden, 1596

The insert map at the far left shows Vardøya with Vardø and the 14th century Vardøhus Fortress. This was one of the regular ports of call for merchant vessels sailing further east, for instance to Arkhangelsk. The other insert map shows the island of Kildin, directly east of the Murmansk Fjord on the northern part of the Kola Peninsula. For several hundred years, Kildin was the most important port and trading post on the Murmansk coast.

5.2 Lucas Waghenaer: “De Custe van Noorweghen […] van Mardou tot Akersondt” from Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, Leiden, 1585

5.3 Lucas Waghenaer: “De Custe van Noorweghen […] van Mardou tot Akersondt” in Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, Leiden, 1586

The story of European knowledge of Norway is often hidden in the changes made between the various versions of a map. Printing plates, which were made of copper, were re-engraved when cartographers received updated or new information about an area. Two versions of Lucas Waghenaer’s maps of the Norwegian coast from present-day Arendal to Båhuslen are shown here.

Map no. 5.2 is from 1585. It shows Akershuys and An∫loo, i.e. Akershus Fortress and Oslo, indicated above one of the large fjord branches on the right side of the map. Compared to the map in the book, which is from 1586, it is clear that the printing plates were re-engraved to include Bunnefjorden and Nesodden and that Oslo is positioned correctly, innermost in the bay. These two maps were printed with the same printing plate, but show Oslo in two different places – from inaccurate in 1585 to accurate in 1586.

5.4 Lucas Waghenaer: “Die zee Custe van Noorweghen tusschen der Noess en Mardou …” from Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, Leiden, (1585) 1596

Unlike the Hanseatics in Bergen, who largely purchased fish from Norwegian fishermen and merchants, the Dutch sailed along the Norwegian coast and traded directly with the farmers. In the mid-1600s, around four hundred Dutch ships travelled the Norwegian coast, some of them several times in one season. As a result, it was easy to find transport to the Netherlands, and many Norwegians emigrated to the Dutch cities to find work. Some stayed, while others worked there periodically while young. Agder in particular saw many young men travelling abroad. In some small towns, as many as one in three young men emigrated. These movements resulted in many Norwegians returning home with new habits, clothes, objects and knowledge.

5.5 Lucas Waghenaer: “Custe van Noorweghen, tusschen Berghen, ende de Iedder …” from Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, Leiden, (1588) 1590

In 1588, Lucas Waghenaer included this map in his sea atlas for the first time. One year later, a long text was added to the originally empty backside of the map, telling about trade along the coast and about the powerful German Hanseatic League’s office in Bergen. It also mentions the length of the longest and shortest days of the year in Bergen, 18 hours and 6 hours respectively.

5.6 Lucas Waghenaer: “Beschrijuinge van Noorwegen” from Thresoor der Zeevaert, Leiden, 1592

This map shows the Norwegian coast from just north of Bergen, around the southernmost point of Norway, Lindesnes (Noeβ) and to Langesundsfjorden.

5.7 Lucas Waghenaer: “Beschrijuinghe vande Oost costen van Noorweghen, tlandt van Noordtoosten” from Thresoor der Zeevaert, Leiden, 1592

The Norwegian coast from Langesundsfjorden to Skåne in Sweden is shown here. Oslofjorden and Oslo (Anslou) can be seen to the far right.

5.8 Lucas Waghenaer: “Beschrijuinge van tgeweste van Noortwegen, ghelegen tusschen Dronthen ende Bergen …” from Thresoor der Zeevaert, Leiden, 1592

Lucas Waghenaer’s sea atlas Spieghel der Zeevaerdt was a tremendous success and its sequel, Thresoor der Zeevaert, was published in 1592. This atlas is not as tall, but is quite wide. All of the maps are centre spread, making the maps unusually long. This format is referred to as oblong. The Norwegian coast from Trondheim (Dronten) to Utvær, the westernmost archipelago in Norway, is shown here.

5.9 Gerard van Keulen: “het Eyland Wardhúÿs”, hand-drawn, approx. 1720

Gerard van Keulen was a mathematician, engraver and cartographer, and it was under his management that the family’s map publishing company developed into a world-leading publisher of nautical charts. Van Keulen also drew a large number of maps by hand – 758 of his hand-drawn maps have been registered to date. These were intended for practical use while sailing and the fact that so many have survived indicates that the production must have been extensive. This map of Vardøya with Vardø and Vardøhus is one of Van Keulen’s hand-drawn maps. Vardø is shown on several old maps, but usually as a map insert on a map of a larger area. This is the earliest known map devoted solely to Vardøya. The island’s location is indicated under the title: 70 degrees and 35 minutes north latitude. This is quite accurate, as the correct location is 70 degrees and 22 minutes north. The fortress, however, is placed on the wrong side of the island.

Willem Blaeu, who had studied with astronomer Tycho Brahe, moved to Amsterdam in 1599. He made navigational instruments and later both globes and maps. Blaeu’s reputation led to his appointment both as the Dutch Republic’s official cartographer and as the cartographer for the Dutch East India Company, which had a monopoly on trade with the East. His task was to gather all available information and maps in order to summarise and expand their information. The voyages were

to be as safe as possible, so the Company’s skippers were provided regularly with new and updated maps. His occupation and access to insider information did not prevent Blaeu from gaining a foothold also in the commercial map market.

Blaeu’s Het Licht der Zee-vaert – “The Light of Navigation” –was the successor to Waghenaer’s sea atlas and is considered to be the beginning of what is known as the Golden Age of Dutch cartography.

5.11 Johannes van Keulen: “Paskaart van de Kust van Noorwegen Beginnende van de Wtweer Klippen tot aan Swartenos …”, Amsterdam, approx. 1685

In the 1600s, it was not uncommon to show an area’s resources and commodities on the maps, especially in the maps’ cartouches, the decorative frames surrounding the title. The Norwegian export of timber is documented from the Middle Ages and onwards, but experienced its heyday in the 1500s and 1600s. The export was so extensive that large parts of the Norwegian coast were nearly deforested. The main market was the Netherlands, where timber was needed to build houses in the expanding cities, for furniture and ships, and for ports and canals. Illustrative of Norway’s important role as a timber exporter is that the Dutch Royal Palace, built as Amsterdam’s City Hall in the mid-1600s, is built on 13,659 piles of Norwegian spruce.

5.12 Johannes van Keulen: “Paskaert Voor een gedeelte van de Cust van Noorwegen Beginnende van Oxefoort tot aen Gottenborg”, Amsterdam, approx. 1680

The cartouche shows various types of animals, including a bird of prey with a catch in its claws. Nowadays, the gyrfalcon is the least known of the old Norwegian export goods. Nonetheless, Norway was a major exporter of trained gyrfalcons for hundreds of years. This export is known to date back to the 900s. Trained gyrfalcons were very expensive, making them status symbols often given as gifts between kings and princes. Norwegian gyrfalcons were not only exported southwards in Europe, but also to such faraway places as the Middle East and Africa. In the rest of Europe, birds of prey were associated with Norway.

Both DanishNorwegian and international interest in the indigenous peoples of the northernmost regions of Scandinavia was intense from the mid1600s. New editions of Olaus Magnus’ book The history of the Nordic peoples were given title pages that showed the Sami in clearly recognisable attire. Johannes Schefferus’ Lapponia (1673) attracted much attention and was translated into several languages. Scientists like Carl von Linné, Pierre Louis Maupertuis and Maximilian Hell all travelled to Lapland to study natural phenomena and later posed for portraits in Sami dress.

The northernmost land areas were not only interesting as ‘untamed’ and consequently as a Nordic America, but were remarkably rich in natural resources. The maps even provided information on the origin of both the precious ermine and far more everyday dried fish.

Frederick de Wit: “Norvegiæ Maritimæ. Pascaert van Noorwegen streckende van Elsburg tot Dronten”, Amsterdam, approx. 1690

6.1 Herman Moll: “A New Map of Denmark and Sweden”, London, 1727

The cartographer Herman Moll worked for English, German and Dutch clients. On this map of the Danish and Swedish kingdoms, he devotes considerable space to the Sami people, “the most remarkable people in Europe”. The pictures on the right show scenes of both religious and everyday life. They reflect a strong ethnographic curiosity, more exoticising than judgemental. Moll’s emphasis on how the Church is Lutheran is particularly striking: this was a time when the Danish-Norwegian mission was as its most intense. Only one generation had passed since the last witch trials were held in Finnmark, a process that linked the Sami religion closely to heathenism and sorcery.

6.2 Plates from Knud Leem’s Beskrivelse over Finmarkens Lapper, deres Tungemaal, Levemaade og forrige afgudsdyrkelse, Copenhagen, 1767

Views of the Sami religion as heretical and dangerous were part of several witch trials in the late 1600s. In the early 1700s, the state launched a mission offensive, with Thomas von Westen as its first major leader. Von Westen took the initiative to appoint the young theologist Knud Leem as missionary priest in Porsanger and Laksefjord. Leem later became a professor at the Seminarium Lapponicum at Trondheim Cathedral School, where teachers and missionaries were educated to work among the Sami.

During the ten years he spent in Finnmark, Leem carried out extensive linguistic and ethnographic studies. His magnum opus, Beskrivelse over Finmarkens Lapper, deres Tungemaal, Levemaade og forrige afgudsdyrkelse (“A Description of the Sami of Finnmark, their language, lifestyle and past idol worship”), was published in 1767. It is a typical Enlightenment text, intended to promote both knowledge and the proper faith. The hundred illustrations are diagram-like, but have a sober, almost mystical quality. These coloured plates are based on the book illustrations.

Themes:

XXXV Work and meals in a tent

LXXXV Sacrificial meal

CXVII Sami missionary with guide travelling in a snowstorm

6.3 Frederick de Wit: “Finmarchiæ et Laplandiæ Maritima”, Amsterdam, approx. 1680

The cartouche here shows merchants in Nordkalotten, the Cape of the North. The man with the red fur-lined coat represents an important Nordic export article, ermine. Ermine is the white winter fur of the weasel. Every black dot is the tip of a tail and a large number of ermine skins were needed to make such a fur lining. Ermine was a popular and expensive luxury item, and in many parts of Europe it would be affordable only for nobility and royalty.

6.4 Frederick de Wit: “Norvegiæ Maritimæ. Pascaert van Noorwegen streckende van Elsburg tot Dronten”, Amsterdam, approx. 1690

This cartouche is decorated with fish hung to dry. The drying of food is one of the oldest known preservation methods and, for hundreds of years, dried fish was the most important Norwegian export. During the Catholic fast of Lent, eating fish is permitted, and this led to considerable demand for nonperishable dried fish. In Europe, dried fish was formerly often called stockfish because it was dried while hanging from wooden racks – from stocks.

6.5 Le Stockfish Norvegién, Directorate of Fisheries in Bergen, 1900s

“The country would not be inhabitable for Christians if the fish catches, which are plentiful, did not entice people to settle here, for this species of fish, which is usually called stockfish, is so valuable that, for the sake of its goodness, it is exported to nearly all foreign Christians.”

From Archbishop Erik Valkendorf’s Finmarkens Beskrivelse, approx. 1520

The first maps exclusively devoted to Norway were published in the early 1600s. Until then, map produc tion had been driven by two motives: the search for a northeast passage to Asia and the endeavour to facilitate maritime trade. The mapping of Norway as a whole country reflected more systematic geographic and historic interests.

It was only natural to obtain this knowledge also from those who lived in Norway. Foreign cartographers eagerly devoured accounts from scholars who had stayed in the country, and the central authorities in Copenhagen collected evergrowing information on the conditions in the northern part of the kingdom. In the 1700s, the acquisition of information took the form of broad surveys – and of mapping. From 1773, the administration and defence of Norway were facilitated by a separate national mapping department. Norwegian mapping of the country now also included mapping of nature and history and was the work of wanderers, historians, artists and others driven by curiosity and enjoyment rather than by strategic interests.

Jan Janssonius: “Nova et accurata Tabula Episcopatuum Stavangriensis …”, Amsterdam, (1636) 1644

A Danish source from the 1600s informs us that Laurids Scavenius, Bishop of Stavanger, drew a map of his diocese in the year 1618. The map was most likely hand-drawn and has been lost over the years. However, Jan Blaeu must have been familiar with the map because he credits Scavenius in the cartouche of his map of Stavanger diocese. Blaeu’s map has therefore come to be known as the “Scavenius Map”.

In Scavenius’ time, the Stavanger diocese included Valdres and Hallingdal rural deaneries This means that Scavenius’ original map must have been a map of Southern Norway, as is Blaeu’s map. But Blaeu’s version shows that, in terms of content, the map is only a diocese map; the cities of Oslo and Bergen are shown, but there are no details in the surrounding areas. Telemark lay beyond Scavenius’ jurisdiction, so the area is shown as a patch of white. Telemark remained a white spot on the map for almost a hundred years afterwards.

7.2 Jan Janssonius: “Nova et accurata

Episcopatuum Stavangriensis …”, Amsterdam, (1636) 1644

Jan Janssonius was Jan Blaeu’s main competitor, and for several decades the two men copied and surpassed each other in their publications of maps and atlases. Janssonius made his version of Scavenius’ map four years before Blaeu, but without crediting Scavenius as Blaeu did. The fact that both Blaeu and Janssonius used Scavenius’ map as a model indicates that the map was known by cartographers in Amsterdam at the time.

The Dutch were more interested in the lumbershipping port in Son than in Oslo and for several hundred years they referred to Oslofjorden as Zoen vater. Janssonius’ map is the first to use the name Oslofjorden –twelve years after Oslo had changed its name to Christiania.

In 1598, a miniature atlas was published with the Dutch title Caert-Thresoor, “The Treasury of Maps”. The atlas became

extremely popular and was published in numerous editions and languages by a series of – mainly Dutch – editors and publishers until 1650.

With regard to Norway, the atlas is appropriately named, as the French 1602 edition was the first to include a map of Norway – the world’s first printed map of the country alone. Prior to this, there was no map specifically of Norway, only of the Nordic countries. The map of Norway was made by Barent Langenes and is entitled “Norwegia”. In French, the miniature atlas in which it is found is called Thresor de Chartes.

7.4 Title page of Thresor de Chartes, published by Cornelis Claesz, Leiden, 1602

The men around the table on the title page of the atlas Thresor de Chartes are surrounded by objects associated with knowledge: a terrestrial globe and a celestial globe, an astrolabe, a Jacob’s staff, an hourglass – and books. A map of America is hanging on the wall. The men are presented as knowledgeable and well-informed: this is an atlas which contains reliable knowledge about the world.

7.5 Jan Blaeu: “Norvegia Regnum” from Atlas Maior, Amsterdam, 1662

Willem Blaeu’s son, Jan Blaeu, published his Atlas Maior in eleven volumes in Latin in 1662. The atlas had 3,000 pages of text and 600 maps, and it was the most expensive written work of the 1600s, yet so popular that in the course of the next ten years, it was published in Dutch, English, German, French and Spanish, in addition to the first edition. This map from Atlas Maior is the first printed map of Norway in large format. Finnmark was not officially Norwegian until the border treaty between Norway and Sweden was signed in 1751, which is why it is not included here.

7.6 Jonas Ramus: “Delineatio Norwegiæ Novissima” from Norriges Kongers Historie, Copenhagen, 1719

Abraham Ortelius stated that those who want to understand history correctly must know the places where it was enacted. Among those who were inspired by this notion about geography as ‘the eye of history’ was Jonas Ramus, priest in

Norderhov. He wrote a series of religious and historical works, often detailed and lengthy. This map belonged to his history of the Norwegian kings and included city names from historic documents. As far as we know, Ramus’ map is the first printed map of Norway made by a Norwegian cartographer. To posterity Ramus has been less known than his wife Anna Colbjørnsdatter, famous for having tricked the enemy Swedish soldiers into getting drunk before they lost the battle at Norderhov in 1716.

7.7 Ove Andreas Wangensteen: “Kongeriget Norge afdeelet i sine fiire Stifter …”, Hamburg, 1761

Ove Andreas Wangensteen’s map of Norway was the first printed map of the country made by a Norwegian cartographer to be widely circulated. The map contains a small oddity. It was published ten years after the signing of the NorwegianSwedish border treaty, but shows the border at one point according to the Swedish territorial claim which was that the border should pass through Lake Femunden. During the border negotiations, Norway had prevailed in this matter and the border was drawn between the highest mountains east of Femunden. In other words, Norway was larger than depicted on Wangensteen’s map. Two years later, in 1763, Wangensteen published a map of Akershus diocese on which the Femunden error was rectified.

7.8 Ove Andreas Wangensteen: “Aggershuus stift”, Hamburg, 1763

On this map, Ove Andreas Wangensteen has placed the border in the correct place, namely east of Femunden. The cartouche on the right side contains a list of symbols of the various types of mining operations found in the diocese: gold, silver, copper, iron and lead.

7.9 O.J. Hagelstam: “Geografisk, militarisk och statistisk Karta öfver hela Sverige och Norrige”, Stockholm, 1821

Prior to 1814, the Swedes did not have direct access to geographic information about Norway, and in particular not to information about military conditions. During the war years just prior to 1814, however, the Swedish mapped strategically

important areas of their neighbouring country. These maps were drawn by hand and are now kept in the Swedish Military Archives.

The Swedish formal access to such information changed when Norway entered into a union with Sweden in 1814. This map of the Nordic countries was published in 1821 and shows the military and civil divisions of both countries down to the very last detail. A list of various senior state officials and civil servants is also shown. According to the publicity for the map, it contains “a complete overview of the entire political organisation of both brother kingdoms”). The map also includes information on everything from mountains, mines, maritime pilots and transport routes to climate and botany. Norway had never before been mapped so thoroughly.

7.10 Erik Pontoppidan: Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie, Volume 1, Copenhagen, 1752

Erik Pontoppidan wrote the two-volume work Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie while he was Bishop in Bergen. The book is considered the main Norwegian product of the Enlightenment, but it is also a continuation of Olaus Magnus’ history about the Nordic peoples. ‘History’ still means knowledge about the world as it is and Pontoppidan only wrote about the past in order to explain customs and beliefs in the present. The bulk of the work is an examination of all elements of Norwegian nature, from the air and water to flora and increasingly advanced animals.

Bergen adorns the title page of the first volume and is also shown on this plate. Pontoppidan did not reproduce any maps of Norway, but included several panoramic views with geographic information. The mountains of Fløyen and Ulriken surrounding Bergen are identified by numbers 14 and 15.

7.11 Erik Pontoppidan: “Tvende Slags Norske Søe-Orme” from Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie, Volume 2, Copenhagen, 1753

Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie attracted considerable interest at the time and was quickly translated into German and English (The Natural History of Norway, 1755). Foreign visitors often read the book before and during their visits to Norway. As a scientific work, however, it soon

became outdated. Erik Pontoppidan based his classifications on the system used by the French natural historian George-Louis Buffons and not on that of Carl von Linné’s, which would turn out to be the foundation of future botany.

Another reason for Erik Pontoppidan’s sinking status was his open interest in what common people told him. He dismissed stories about monsters as superstition, but made an exception for mermaids and mermen, sea serpents and the enormous kraken. He had never seen any of these himself, but he had heard so many credible stories about them that he saw no reason to doubt their existence.

7.12 Christian Jochum Pontoppidan: “Det sydlige Norge”, Copenhagen, 1785

For a long time, cartography had been a military skill. In 1773, the 34-year-old Christian Jochum Pontoppidan was appointed drawing master at the Danish Landkadetkompagniet (Land Cadet Corps). By then he had been in foreign military service for 15 years. The Norwegian Border Survey was also established in 1773. Today, it is called the Norwegian Mapping Authority.

Pontoppidan’s two maps of Norway were the most accurate to date and he published a book for each which described in detail how he made the maps. His greatest advantage was that the government actively facilitated the work and gave him access to both the Survey’s completely new trigonometric surveys and all existing maps. The maps were excellent, but perhaps it is the government efforts involved that truly make these maps an event in Norwegian map history.

The map was published in two parts with an interval of ten years. The map of northern Norway is map no. 7.13.

7.13 Christian Jochum Pontoppidan: “Det nordlige Norge”, Copenhagen, 1795

7.14 P.A. Munch: “Det sydlige Norge”, Christiania, 1845

Peter Andreas Munch was first and foremost a historian, famous for his studies of the Norwegian Middle Ages and his publications of the sources to ancient Norwegian history. He was also a talented illustrator and cartographer. Munch’s belief in the significance of geography for history was a

traditional one. The concept of geography as ‘the eye of history’ was common in the 1700s and influenced among others the historian and cartographer Jonas Ramus. But Munch built on a broader knowledge base than Ramus; his maps were based on scientific surveys and were accurate depictions of the physical landscape to an entirely different degree than those of his predecessor.

7.15 Kirstine Colban: “Cart over Lofodens og Vesteraalens

Fogderi i Nordlands Amt, med dets Øer, Strømme og Sunde”, Kirkevaag in Lofoten, 1814

Kirstine Colban was Norway’s first female cartographer. At the age of 24, she made this map of Lofoten and Vesterålen. Her father was Erik Andreas Colban, a priest in Lofoten and Vesterålen, and the map was included in his book An Essay on the Description of Lofoden and Vesteraalen Bailiwick, published in Trondheim in 1818.

7.16 P.A. Munch’s map of Hardangervidda in Indberetning om hans i Somrene 1842 og 1843 med Stipendium foretagne Reiser gjennem Hardanger, Numedal, Thelemarken m.m., hand-drawn, 1842–1843

His wanderings over Hardangervidda could be called a highlight in P.A. Munch’s career as both geographer and historian. The result was his large Report on His Journeys through Hardanger, Numedal, Telemark, etc., on Stipend in the Summers of 1842 and 1843, and several hand-drawn detailed maps of a known, yet academically little explored area. The experiences from his wanderings became part of Munch’s ideas about the landscape as the physical imprint of history. This very specific understanding made him aware of the need for accurate maps. Hardangervidda retained a special place in Munch’s heart. A telling example is a letter in which he tells about his journey from Vienna to Rome in 1858–1859:

“The entire road from Civita Vecchia to Rome instinctively reminded me of parts of the road across the Dovre mountain range or certain parts of Hardangervidden, such as the large Thormodsflaaet: the same emptiness, the same absence of signs of life and human activity.”

7.17 Thomas Hans Heinrich Knoff’s map of Finnmark, hand-drawn, 1749

Finnmark was not officially part of Norway until the border treaty between Norway and Sweden was signed in 1751. Until then, the border conditions in the northern part of Scandinavia and Russia were very unclear and the inhabitants in some areas were taxed by several countries.

Knoff’s map of Finnmark was drawn in preparation for the border treaty to be signed. Prior to the treaty, the entire Norwegian-Swedish border from south to north was surveyed, discussed and negotiated. The same applied to the border with Finland, which at this time was part of Sweden.

Knoff’s map contains a wealth of place names, naturally including many in the Sami language. In Finnmark, Tana was chosen as the border river, giving Norway the large areas of Kautokeino, Karasjok and the part of Utsjok which lies to the west of Tana. The Sami division into siidas, communes that claim, exploit and manage rights in a region, had previously been the closest thing to borders on the Northern Cape. Utsjok was one such siida, and Knoff mentions it in the explanatory text on the map, spelled as Utziocki.

Lorentz Diderich Klüwer was a Norwegian subordinate officer who fought in the battles against the Swedes when the army of Charles XII attempted to take Trondheim in 1718. Klüwer was later promoted to lieutenant-colonel and commander of the Nordenfjeldske Ski Corps and in the 1760s he drew several maps showing the Swedish entry into Trøndelag and the fatal retreat which ended with thousands of Caroleans freezing to death in the Tydal Mountains.

This map shows the retreat routes taken by the Caroleans. The areas where they were caught in the storm are marked with black clouds. The reference letter ‘E’ next to the clouds at the upper right refers to the overnight stops of the army and under the ‘E’ in the frame a text informs the reader that three hundred men froze to death here.

Klüwer’s maps, drawn several decades after Charles XII’s attempt to take Trondheim, are the first detailed maps of the inland areas in Trøndelag.

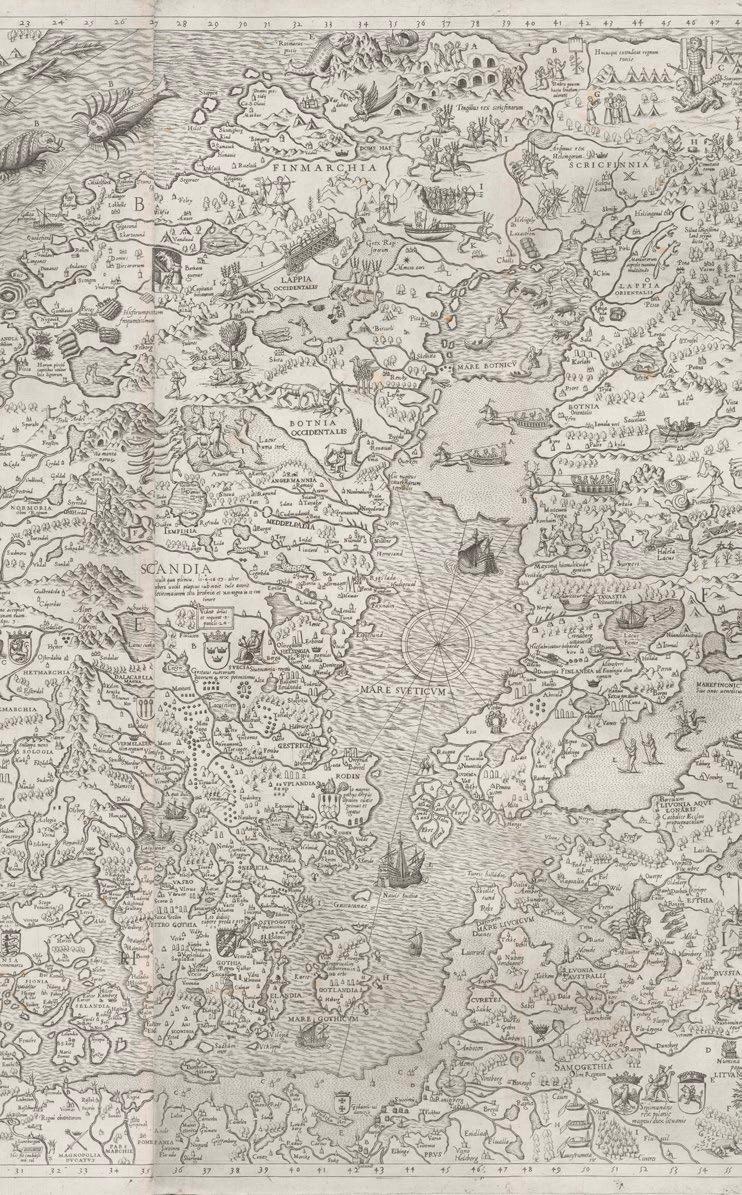

The learned priest Olaus Magnus left Sweden in 1523 as an envoy for the new king, Gustav Vasa. He was to ask the Pope for approval of the appointment of his brother Johannes as the new archbishop. However, after a few years it became clear that Gustav’s religious sympathies leaned more towards Lutheranism and Olaus remained in exile on the continent to champion the cause of the Catholic Church. The Pope eventually appointed Johannes and, later on, Olaus as archbishops for the Swedish Catholic Church, but neither of them ever returned home and no one has held this title since.

Olaus published a map in Venice in 1539. It was called “Carta Marina” and showed the Nordic countries, the North Sea and the Baltic Sea regions. His major work, The history of the Nordic peoples, a broad presentation of geography, customs and animal life in the Nordic countries, was published in 1555. The book contained hundreds of illustrations, many of which were drawn from the map’s abundance of details. The Nordic countries were little known to continental readers and both the map and book attracted considerable

attention. Motifs from the map, especially Olaus’ numerous and spectacular sea monsters, appear in a wide array of other historical sources to 16th and 17th century history.

Olaus was typical of the Renaissance in his concern with the connections between his own time and Antiquity. He derived much of the material he used from classical writers such as Aristotle, Strabon and Pliny the Elder.

Sebastian Münster’s Cosmographia – a description of the entire world – was published for the first time in 1544 and is one of the earliest examples of Olaus’ popularity. At this time, five years had passed since the publication of “Carta Marina”, and The history of the Nordic peoples was still a work in progress.

This illustration shows animals and sea monsters in the Nordic countries, most of which are easily recognisable. Münster also included some of Olaus’ more exotic land animals. According to Olaus, the wolverine, shown in the middle of the top edge of the illustration, has such a voracious appetite that it eats until it can barely move. To continue moving, it must push itself between two trees in order to relieve itself. This was a warning against gluttony, one of the seven deadly sins.

Today, the title of this book, The history of the Nordic peoples, is misleading. In the 16th century, ‘history’ did not primarily refer to what had already taken place, but to knowledge about the world as it is. Olaus does write about heroes from the past, but he is primarily concerned with the Nordic countries in the here and now: rich in natural resources, with fantastic animals and brave and knowledgeable people. The book was written in Latin, but translated into various other languages in the 1500s and 1600s.

Olaus wanted to teach his readers that the unknown North was rich and strong, and that the region was part of an old Christian fellowship rooted in Antiquity. This was his way of showing what could be lost in this fellowship if Lutheranism was to be victorious in the north.

A peculiarity in this first edition is that it includes a map of much lower standard than “Carta Marina”. The book was not primarily concerned with geographical precision.