SPRING/SUMMER | 2024

FIND YOUR SEA STORY IN OUR SUMMER CAMPS The best chapter of summer. For more information or to register for a summer camp or sailing program, visit www.mysticseaport.org/summercamps or call 860-572-5331.

MYSTIC SEAPORT MUSEUM MAGAZINE is a publication of Mystic Seaport Museum.

PRESIDENT

Peter Armstrong

CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD

Michael Hudner

EDITOR

Sherri K. Ramella

editor@mysticseaport.org

DESIGN

Susan Heath

CONTRIBUTING DESIGN

Heather McGuigan

CONTRIBUTORS

Sarah Armour

Peter Armstrong

Christina Connett Brophy, PhD

Ashlyn Buffum

Emma Burbank

Lydia Downs

Chris Freeman

Bill Gardner

Chris Gasiorek

Scott Gifford

Akeia de Barros Gomes, PhD

Kendall Guarneri

Amanda Keenan

Arlene Marcionette

Sophia Matsas

Shannon McKenzie

Maria Petrillo

Jeremy Sachs

Nancy Seager

Allison Smith

Kendall Wallace

Chris White

Osman Can Yerebakan

PHOTOGRAPHY

Bill Gardner

Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation

Joe Michael

Mystic Seaport Museum Archives

Andy Price

Jeremy Sachs

ON THE COVER

Sail reflection on the Mystic River during the Museum's summer sailing program. Photo taken by Joe Michael.

CONTACT

Visitor Information: 860-572-5315

Administration: 860-572-0711

Advancement: 860-572-5365

Membership: 860-572-5339

Program Reservation: 860-572-5331

Museum Store: 860-572-5385

Volunteer Services: 860-572-5378

Please go to the Museum’s website for information on spring and summer schedules.

The Log

Find Your Sea Story Video Series

American Institute for Maritime Studies

Mainsheet Launches

Keeping Brilliant Brilliant

The Susan Constant

Economic Impact Study

Wells Boat Hall

75 Greenmanville Avenue

Mystic, CT 06355-0990 www.mysticseaport.org

Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea A Story, by the Water and From Above

SPECIAL: FIND YOUR

Finding a Sea Story

Adversity to Inspiration: A MAP Sea Story

A Brilliant Sea Story

Life's Greatest Lessons Learned at Sea Catch a Wave

The Buckingham-Hall House The Cooperage

The Charles Mallory Sail Loft

Stories from the Collections

The Letters of William Peter Powell

The Admiralty Model of HMS Burford

The Packard Sketches—A Sea Story Mystery Solved! Asherah: The Reinvention of Underwater Archaeology

The Little-Known Story of Evinrude A Fine Line

CONTENTS VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE................................. 4 MUSEUM NEWS .............................. 6

................................. 11 FEATURES 12

MEMBERSHIP

16

SEA STORY

UPCOMING EVENTS 31 12 22

10

29

A Message from the President

From the tale of the fish that got away to the epic saga of Moby Dick, from the "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" to Jack and Rose looking for love on the Titanic, stories of the sea have inspired, influenced, and shaped our lives.

Mine began before I was born when a 16-year-old man followed his older brother into the British Merchant Navy, serving six years and later marrying my mom. Although my father spent only a brief time at sea, its legacy was never forgotten, and when he was an 80-year-old man and nearly blind, I would drive him to the mouth of the River Tyne on the northeast coast of England to watch the boats come in and to hear his sea stories. He had not gone to sea for 60+ years, but his memory was rich with stories of meeting Neptune when he “crossed the line,” painting the mast from the bottom up and sliding down through the paint, and getting his obligatory tattoos of a ship and an anchor in New Orleans. The influence on his life was as strong as the day he left his mother for the first time and embarked on his first adventure.

When Mr. Bradley, Mr. Cutler, and Dr. Stillman met on Christmas day in 1929 to sign the papers of incorporation of the then Marine Historical Society, they could not have known that it would grow into the largest maritime museum in America and that Mystic Seaport Museum would play host to over 260,000 visitors a year. But I am guessing they did know the importance of the message they wanted to tell the future and that every one of those visitors would find some connection with the sea.

At the Museum, we ask visitors to “find their sea story,” as everyone has one. In this edition of Mystic Seaport Museum Magazine, I hope you will find the stories of others entertaining and compelling, and then discover or rediscover your own sea story.

4 / View from the Bridge

Peter Armstrong

Peter's father, John Frederick Armstrong, "always a man of the sea," standing on the Skye Bridge at the Kyle of Lochalsh, Scotland.

Peter at 2 years old in his favorite sailor suit.

Show The 32ndAnnual June 28-30, 2024 TICKETS ON SALE NOW. FOR MORE INFORMATION VISIT www.mysticseaport.org/woodenboatshow

The Log—Now Available Digitally

An integral part of the Mainsheet: A Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies publication initiative was the goal to digitize the archived printed copies of The Log of Mystic Seaport for increased and broader public access. The Log ran from 1948 to 2004 and was included with a Museum membership. At its height, this publication was circulated to over 25,000 Members. It included articles of interest on all things maritime, including shipbuilding, history, maritime society and justice, architecture, art, and even invasive species! It is a fantastic resource to remind us of who we are and where we began as an institution. It is also a record and celebration of many of the great thinkers and experts who have come through Mystic Seaport Museum since the middle of the last century. We extend our gratitude to Paul O’Pecko, former Vice President of Collections and Research, who worked with a team of volunteers and staff over the last two years to achieve this goal! All issues of The Log of Mystic Seaport are now available for download.

To view issues of The Log, visit mysticseaport.org/thelog

Find Your Sea Story Video Series

As part of the Museum’s Find Your Sea Story campaign, we will be launching a mini documentary series that delves into the rich tapestry of human experiences connected to the sea. Each episode takes viewers on a voyage, revealing the profound and enduring connections between individuals and the ocean whether through tales of immigration, cherished family narratives, sailing and boating, inaugural moments on the water, or transformative experiences at Mystic Seaport Museum. The first story is told on page 16 and the accompanying video will be available starting June 7 at www.findyourseastory.org. Future episodes may be viewed here as well.

To subscribe or view more of the Find Your Sea Story series, as they become available, visit us at www.findyourseastory.org.

6 / Museum News

LAUNCH OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR MARITIME STUDIES

We are pleased to announce the launch of the American Institute for Maritime Studies at Mystic Seaport Museum, which will be focused on education, research, scholarship, and community engagement. Scholars and thought leaders throughout the maritime world will now have many new opportunities to engage with the Museum and our collections replete with fascinating stories just waiting to be told.

To lead this endeavor, thanks to a very generous gift from William and Antonia Cook, a new position has been created, the William E. Cook Vice President of the American Institute for Maritime Studies. Akeia de Barros Gomes, PhD, has been appointed to this position and charged to integrate our flagship education programs—the Frank C. Munson Institute for Graduate Studies and Internship Program and the Paul Cuffe Memorial

Fellowship—with our collections and the G. W. Blunt White Library to develop the American Institute for Maritime Studies.

At Mystic Seaport Museum, we believe that the sea connects us all and that every object, artifact, and document in our collections has a tale to tell. Time and time again, deep research and thorough scholarship enables us to conjure the very voices and perspectives of the people who lived the tale. We look forward to welcoming you to the American Institute for Maritime Studies!

MAINSHEET LAUNCHES

Mystic Seaport Museum is thrilled to announce the print and online release of the first issue of Mainsheet: A Journal of Multidisciplinary Maritime Studies. Each issue will be themed, and the inaugural issue focuses on maritime social history. It contains original scholarship from leaders in their fields, including “Liquid Motion: Reimaging Maritime History Through an African Lens” by Kevin Dawson; “Our Lady of the Workboats: Solidarity and Spirituality on the Bay of All Saints” by Alison Glassie; “Dragon Ships to the Dawnland: Eugène Beauvois and the Vinland Viking Expeditions in the Nineteenth-Century Settler Imagination” by Alice C. M. Kwok; “Extracting Global Maritime Weather Data from New England Whaling and Portuguese Navy Logbooks (1740–1960)” by Timothy D. Walker and Caroline C. Ummenhofer; and “The Narraganset Chief, or the Adventures of a Wanderer: Recovering an Indigenous Autobiography” by Jason R. Mancini and Silvermoon Mars LaRose. We are deeply proud of this exquisitely designed work packaging a powerful photo essay from the International Transport Workers’ Federation seafarers’ photo contest with special features such as poetry and reviews of books and exhibitions. The journal is open access online, with no fees charged to the authors. We encourage Museum Members and other readers to purchase the print edition and subscribe to upcoming issues to support this model of open scholarship. The second issue (pictured) focuses on maritime technologies, livelihoods, and economies, and the third will explore undersea archaeology.

Details on how to purchase and subscribe, as well as calls for papers for future issues, are available at www.mysticseaport.org/mainsheet.

Museum News / 7

Keeping Brilliant Brilliant

After nine decades of active use and 70 years delivering positive youth development through sail education, the beloved schooner Brilliant is ready for some extra attention. Beginning in the fall of 2024 a major project will address aging structure that is original to the vessel and aging equipment that has reached the end of its serviceable life. The engine and bronze fuel tank will be pulled from the center of the vessel to access frames that are de-lignified down low in the center of the vessel. New frame sections will be installed, and bronze strapping will reinforce the joints. A new fuel tank and engine will be installed, aligning with the Museum’s Low Carbon Transformation initiative, and Brilliant will be ready to set sail again in the summer of 2025. This work will set the stage for Mystic Seaport Museum to expand the Brilliant program to encompass more blue water voyaging in the decade ahead. With the Museum’s shipyard booked with projects into 2026, and after careful consideration, Rockport Marine in Rockport, Maine, was selected to complete this complex, multi-faceted, and time-sensitive project.

We are seeking $3,000,000 in philanthropic support to make the necessary repairs, augment the endowment, and fund future voyages beyond New England waters. If you would like to support this effort, please contact the Advancement office at 860-572-5365 to make your contribution to “keep Brilliant brilliant.”

Museum Awarded Susan Constant Contract

The Museum’s Henry B. du Pont Preservation Shipyard has been selected to complete a multi-year restoration project on the Susan Constant, the flagship of Jamestown Settlement's three square-rigged vessels designated in 2001 as the “official fleet of the Commonwealth.” A re-creation of the largest of the three ships that carried English settlers to Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, the ship is a centerpiece at Jamestown Settlement, a museum of 17th-century Virginia, representing a tangible link to America's colonial past. Constructed in 1990 at Jamestown Settlement, the 120-ton cargo vessel measures 116-feet long and is square-rigged with three masts, a main deck, a ‘tween deck, and a hold. The design, materials, and construction methods closely mirror those of the 17th century. The vessel will arrive at Mystic Seaport Museum in June and for the next two years. Museum shipwrights will work to replace compromised framing, rebuild the beak head and gallery, replace all of the planking above the waterline, re-caulk the planking below the waterline, replace iron work, and paint the entire ship. The restoration is expected to extend the exhibition life of the Susan Constant for 20 to 30 years, allowing Jamestown Settlement interpreters to bring to life the story of the four-and-a half-month voyage from England to Jamestown for decades to come.

8 / Museum News

“. . . making the waterfront alive, being able to have people actually come and go out and sail a boat or bring their own boat to the marina and all kinds of events that have been happening.”

The Museum commissioned a Community and Economic Impact Report to understand our financial and social contributions to the local community. The geographic data received gives us a better understanding of visitor interests, characteristics, and reasons for coming to the area, which allows us to craft Museum offerings to better suit visitors’ needs and interests. Survey respondents were asked about the Museum’s commitment to the local community and results show that we are a symbol of community enrichment— combining education, economic growth, and cultural depth. The top three benefits were access to a park-like setting by the Mystic River, hosted community activities, and educational offerings. Especially noted was the Henry B. du Pont Preservation Shipyard which represents artisanship, history, innovation, and boosts economic and cultural influence. This data will allow us to better describe the work and influence we have in the region, especially as we look for funding opportunities.

Key Insights

· Of the quarter million visitors to the Museum each year, about one third came to Mystic specifically to visit Mystic Seaport Museum.

· The economic impact of the Museum on the region is profound, contributing $49.2 million to GDP.

· Visitor engagement and spending at the Museum significantly drives its economic impact.

· Beyond its economic contribution, the Museum is a cultural and educational hub.

· On average, each visitor spends a total of $472 during their trip: food and beverage 33%, lodging 28%, retail 14%, attractions 12%, transportation 9%, recreation 3%, and other 1%.

41% OF OUR

ARE FROM OUT OF STATE 561 TOTAL MYSTIC

MUSEUM JOBS SUPPORTED IN THE COMMUNITY (Full

$15.2 MILLION TOTAL INITIATED TAXES Federal: $6.3 million State and Local: $8.9 million $34.6 MILLION TOTAL WAGES AND SALARIES PAID

Museum News / 9 ECONOMIC IMPACT STUDY

$50.1 MILLION VISITOR SPENDING + OPERATING EXPENDITURES

VISITORS

SEAPORT

and Part-Time)

Overview of the Economic Impact of Mystic Seaport Museum

NAVIGATING HISTORY: THE CAMPAIGN FOR WELLS BOAT HALL SETS SAIL

Deep inside the Rossie Mill at Mystic Seaport Museum lives the American Watercraft Collection, the largest and most diverse small craft collection in the country. However, few have had the opportunity to experience the Museum’s signature collection and learn from this 3-D encyclopedia of the American maritime experience. Until now.

We are thrilled to announce a transformative endeavor is underway—a capital campaign to bring the captivating stories of this collection to the public. This ambitious initiative, fueled by passion and a commitment to preserving our maritime heritage, aims to raise $15 million to establish the Wells Boat Hall, an exceptional exhibition space that will allow future generations to continue to explore their own sea stories.

The proposed Wells Boat Hall exhibition promises to be a voyage through time, showcasing an array of vessels that have played pivotal roles in shaping the narrative of the United States. From the imaginative origins of Indigenous watercraft to modern day racing boats, this exhibition will be an immersive experience for visitors of all ages.

Thanks to incredibly generous donors, including Stan and Nancy Wells, for whom the space is named, the Wells Boat Hall campaign has already raised over $7 million. This support will fund the continued restorationof the Rossie Mill and the development of the exhibition of our diverse collection of American watercraft. Museum leadership envisions an interactive exhibition that not only showcases the vessels but also tells the stories of the sailors, explorers, and innovators who relied on these watercraft to traverse vast waterways.

“This project has been a long time coming, and I’m delighted to see so many Museum and community members get behind it,” Museum Board Chair Michael Hudner said. “By investing in Mystic Seaport Museum and in projects like this one, we’re protecting our collections for the future—one that meets the needs of our modern visitors. We’ve come so far already. This is the next step.”

Mystic Seaport Museum has always been a beacon of cultural enrichment, and the Wells Boat Hall will further the Museum’s mission by creating an educational and entertaining experience. Visitors can expect to encounter meticulously curated canoes, historic fishing boats, illustrious vessels, and iconic boats that once plied the rivers, lakes, and oceans that define the American landscape.

“Mystic Seaport Museum has dreamed of having an indoor display facility for more than forty years. We are pleased to help make that dream come true with the Wells Boat Hall, where the many stories in the Museum's small vessel collection will be revealed.”

—Stan and Nancy Wells

The campaign is so much more than financial support; it's an invitation for the community to be a part of preserving a crucial aspect of American heritage. Donors will have the opportunity to leave a powerful legacy by supporting the conservation efforts and ensuring that future generations can appreciate the maritime legacy that has shaped the nation.

The Campaign for Wells Boat Hall is a call to action for all those who appreciate the importance of preserving history. Some of life’s most important lessons can be learned at sea, and donations will make it possible for the sea stories in the Museum’s watercraft collection to emerge from the shadows for generations to come. As the campaign sets sail, we invite everyone to be part of this exciting journey.

For more information or to support the Campaign for Wells Boat Hall, please contact the Advancement office at 860-572-5365 or advancement@mysticseaport.org.

10 / Museum News

Existing Rossie Mill South facade Existing garden wall Existing South Elevation View 1 4 = 1'-0" (As seen from Rossie Pentway) Existing corner of Mill remains untouched Elevator is approached straight-on (walking north) and exits in same direction into Mill Grand Stair Frame-roof with plywd. sheathing, insul. bd. and TPO membrane Stonepanel® mounted to cast-in-place concrete frame with metal interlocking channel system WELLS B O A T H A L L Wood brightwork sign-band, engraved gold-leaf lettering (bows slightly as marquee) B A3.1 A A3.1 A D C A3.1 A3.1 A3.1 A A 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 75 76 79 80 Oldcastle Tower glazing (see Window Schedule & Details) Cricket roof between Tower and Sawtooth

Wells Boat Hall architect renderings and interior concepts by Cambridge Seven.

THE MEMBERSHIP BUILDING: A Cherished Retreat

In 1810, a charming house stood proudly on Water Street, a site of community and maritime heritage. After the hurricane of 1938, in which the house suffered significant damage, the stones from the house found new life in the Museum’s Membership Building, serving as a poignant reminder of our roots and the enduring legacy of those who came before us. Each stone was carefully photographed in the correct positions so they could be reassembled. Although not an exact replica, the building is reminiscent of the original structure. Other individuals contributed to the authentic early-American atmosphere. James H. Allyn donated the stones and bricks that would become impressive fireplaces inside, while C. Fred Hewitt donated the doorstone that now greets Members who pass through the doorway in search of refreshment, respite from weather, or the simple fellowship that membership fosters.

Fast forward to 1965, a pivotal year that saw the opening of the Membership Building to Members. At that time the Museum, known then as the Marine Historical Association, positioned the building next to the original entrance to the Museum. It quickly became a cherished retreat—a sanctuary where Members could relax, unwind, and establish lifelong connections. It's not just a building; it's a warm embrace of history and camaraderie, a space where tales of the sea intertwine with the bonds of friendship. Over the decades, the Membership Building has evolved into more than just a physical structure; it has become the beating heart of our Museum family. Within its welcoming walls, Members gather to unwind, share stories, and forge lasting bonds rooted in a shared passion for maritime heritage and our beloved Museum.

The building pays homage to Mildred Courtney Mallory, who dedicated many hours of her life to Mystic Seaport Museum and the Marine Historical Association. Due to her drive to have membership play an important role in the Museum’s future the membership base steadily grew. By 1941, there were 225 Members. The future of the Membership Building is filled with endless possibilities for what has grown to more than 11,000 Members, thanks to an idea born out of Mildred’s devotion to the Museum!

The building is a reminder of the resilient spirit that has carried the Museum through the ages, and it continues to be a beacon guiding us towards new adventures, new friendships, and new memories waiting to be made. The Membership Building lounge is open to Members and relies on volunteer support.

To become a Member or volunteer, please email membership@mysticseaport.org. We look forward to welcoming you!

Membership / 11

Embarking on a New Story

Please note, as a member of the Black community, I will use “we” and “our” in this article. I was Lead Curator on the exhibition for Mystic Seaport Museum, however the exhibition was created in collaboration and consultation with Black and Indigenous community members. Design and fabrication was done by SmokeSygnals, an Indigenous design firm. This is an exhibition of our stories told in our perspectives.

In April, the Museum premiered not only a new exhibition, but a new perspective on maritime histories. Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea is the culmination of a three-year Mellon Foundation-funded project in collaboration with Brown University and Williams College. The larger project, Reimagining New England Histories, seeks a deeper understanding of the histories of colonialism, racialized slavery, and dispossession in New England. Entwined highlights that Black and Indigenous maritime histories are larger than these topics. The exhibition tells a story of these traumas without tragic end, focuses on kin and community, and imagines, “How would the maritime history of the Dawnland (New England) be told if it had always been told through Black and Indigenous perspectives? In collaboration with Black and Indigenous community members, Entwined seeks to tell the maritime history of the Dawnland the way our ancestors would want the story told. The stories are told in their honor.

The title Entwined captures the way the maritime histories of Dawnland Indigenous peoples from many nations and Africandescended peoples from many kingdoms became intertwined when Africans were brought to the Dawnland during the era of slavery. The narrative is one that positions colonialism, racialized slavery and dispossession as the context for Black and Indigenous maritime encounters, but not as the sum of our story. The primary narrative

is of Dawnland and African maritime histories before European encounter, the story of African-descendants encountering the Indigenous nations of the Dawnland, and provides an understanding of how our millennia-old maritime traditions and creative adaptations enabled us to survive the disruption of colonialism.

Did you know that despite being separated by the Atlantic, many sub-Saharan African societies had a similar spirituality regarding water, ancestors, and canoe-making as that which exists throughout tribal nations in the Dawnland? tribal nations in the Dawnland? In honor of these similar traditions, the centerpiece of the exhibition will be a muhshoon (Pequot)/Aklo (Togolese), or dugout canoe, that was created during a 10-day residency with four canoe-makers that are Mashantucket Pequot, Mashpee Wampanoag, Togolese, and Ghanaian. While the muhshoon/aklo is a piece of contemporary art, it was created using the traditional method (on both sides of the Atlantic) of burning out a tree trunk rather than digging it out with tools. Visitors to the exhibition can also see video footage of the canoe being constructed and reflections of the artists involved.

In addition to traditional African and Dawnland belongings (objects), the exhibition features a reproduction of an attic space. The attic highlights that while enslaved and indentured people often had to live in attics throughout the Dawnland—with their frigid winter temperatures and stifling summer heat—these uncomfortable spaces also provided a degree of privacy and refuge. This re-created attic space features an eighteenth-century spirit bundle that was discovered under a floorboard in Newport, Rhode Island, in 2005. The bundle demonstrates not only the creative adaptation

of the enslaved, but the maintenance of African spirituality.

There is also a traditional wetu (Dawnland Indigenous dwelling) and an Eliot Bible. The Eliot Bible was translated into Algonquin language and printed by a Nipmuc man Wowaus (James Printer) in order to convert Algonquin-speakers to Christianity. The Bible is featured in the exhibition not to tell the story of conversion, but to tell the story of reclaiming Indigenous languages. Centuries after the Eliot Bible was produced, it was utilized to reclaim Algonquin languages throughout the Dawnland.

The final highlight of the exhibition is a room of Black and Indigenous contemporary art. Visitors will have access to interviews with artists featured in the exhibit to understand how their work honors their histories and ancestors and how their contemporary art makes the statement, “We are still here,” and reclaims Black and Indigenous freedom, sovereignty, and the sea.

Akeia de Barros Gomes, PhD, William E. Cook Vice President of the American Institute for Maritime Studies

RIGHT: Staff with a figure representing the Deity Eshu. Yale University Art Gallery Charles B. Benenson, B.A. 1933, Collection

In the dawnland, early enslaved Africans and their descendants likely called on Eshu for guidance and justice. Unable to create figures like this one for fear of punishment, they had to be creative and secretive in making materials and offering prayers to Eshu.

FAR RIGHT, TOP: Aboriginal cooking pot, circa 500 BCE. Connecticut State Archaeologists, Office of State of Archaeology

While simple, the tools of Indigenous tribes were effective. Both in the Dawnland and throughout the African continent shell tempering technology in ceramics resisted fragmentation in the production of the vessel.

FAR RIGHT, BOTTOM: Ceramic sculpture of whale tooth art, by Courtney M. Leonard, Shinnecock Ceramic, 2015.

12 / Feature ENTWINED

Entwined seeks to tell the maritime history of the Dawnland the way our ancestors would want the story told.

The

stories are told in their honor. ”

NTWINED Feature / 13

”

A STORY, BY THE WATER AND FROM ABOVE

The winds are rough on the excursion from which I am typing these words—up and down we go, chasing the unclarity of the horizon ahead. The destination sits far off, across the Atlantic, towards northwest Europe. I am on an aircraft, en route to Amsterdam to connect to Milan. The turbulence we’re experiencing over Canada is not unlike the rough sea, challenging the stubborn vessel with its precarious blows. I know that “easy” has rarely been a part of any voyage. For me, the journey started in the seashore city of Antalya, on the Mediterranean part of Turkey. Growing up a ten-minute walk from the sea, I took the coastal life for granted. I might have even envied those who lived in Istanbul where the sea was equally prominent but so was the culture and its expressions.

Looking back today, I see an unparalleled privilege in the ease and the heat, the reach and the breeze. The way the seagulls glide onto the surface and get back up or the boats dot the dark blue water in the afternoon carving visions that linger in memory and eventually settle for good. And there is yakamoz—a word in Turkish, without direct English translation, meaning the moon’s reflection onto the sea at night. There is hardly any better painting than a bulbous yakamoz on a July night when the full moon washes the dark sea with a liquid silver hue.

In terms of the journeys, the move to New York from my hometown sixteen years ago is the biggest that I have ever embarked on—one that I doubt will be overshadowed by any other. Over the years, I have zigzagged the Atlantic countless times, traversing the capricious waters from thousands of feet above in an airplane, with an anticipation of reaching home of which the definition or the address has only become growingly vague. Living an ocean apart from my hometown perhaps gives me a more day-to-day awareness of distances. Between the physical reality of the mundane and the memories embedded in the cerebral, there is a slippery state of belonging, both here and there. Here I am crossing the ocean again, when the waves of the sky are rough on our vessel.

I returned from another journey a day ago, from Mystic, Connecticut, where I spent a week at Mystic Seaport Museum in early April. New England weather was still indecisive about standing on our side or acting mischievous, constantly showing her different face much to our helpless curiosity. Throughout the week, my visits to the Museum’s various departments slowly revealed the sea’s entanglement with

storytelling. From the whale-slaughtering expeditions to greedy invasions in search of new lands, the sea has witnessed some of the starkest realities of humankind. My time at the Museum indeed urged me to see the boats’ sculptural aspects, not only through their formalist heft in energetic geometries but also with their static silence that contains depth of narrative. Exploring the collection that includes over five hundred boats in a plethora of sizes, I witnessed their rough compositions

“Born and raised by one sea and living surrounded by another one in New York, I can rarely imagine a life far from it. The sea, for me, is a reminder of what awaits in the invisible, beyond the horizon line, as well as beneath the surface. My sea story stems from this curiosity for other tales, far or near, prompted by my urge to get near to them to listen.”

in which elegance rests. Painted by the countless strokes of the sea, their canvases were elaborately worked, primed with the wind and finished with salt. Their silence was eerie and their stillness hypnotizing. Retired to the land, they contained a sculptural completeness, both in shape and soul. They no longer ushered us across the ocean or to the next town, but they always gestured ahead, affirming that a destination awaits.

After spending most of my life moving back and forth between continents, the liminal

space of travel has gained resonance itself; the in-between state has claimed its own poignancy. My travel experiences on aircrafts may have lacked the romantically lingering ease of a sail, a pace that demands savoring the journey. The exposure to the Museum’s boat collection, however, let me imagine. What intrigued me was not only the upcoming exhibition space dedicated to displaying some of their boats in the collection—I also mused on the countless stories enveloped inside each vessel. Before some of them go on view in the inaugural exhibition next year, I witnessed their calm resonance outside of the spotlight. Tired might be one attribute to describe them in their retreat, but their sculptural afterlives defy any sign of wear. Like lines on a face, their signs of time only tug them towards timelessness. As a constant traveler myself, I strive for the sea stories that inhabit each of them: how different are they from mine? Are the greatest and the bleakest human stories similar in core even when they are decades or centuries apart? There are many documented experiences, including a Cuban family escaping to Miami or a Museum visitor recognizing her grandfather’s boat decades later. The vessels, however, are silent witnesses to many untold or forgotten human tales as well. War, love, ambition, curiosity, or even greed and violence drove many crafts ahead, and as my exploration into the collection has proven, always a grander human element awaits to be discovered. Between the wooden cracks and chipped paint lies more to discover, most of which will perhaps never see daylight.

My sea story is still an unfinished book, an open-ended journey with more and more chapters being added as curiosity for places and people guides my way. Born and raised by one sea and living surrounded by another one in New York, I can rarely imagine a life far from it. The sea, for me, is a reminder of what awaits in the invisible, beyond the horizon line, as well as beneath the surface. My sea story stems from this curiosity for other tales, far or near, prompted by my urge to get near to them to listen. The sea is a carrier, just like the sky or the land, it tugs and hauls our stories, from the bleak to the hopeful, when the destination means an end or a beginning. Having never lived away from the sea is a reward, a grounding and calming prize that re-assures the existence of stories out there in the sea, buried, floating, or hovering above. Osman Can Yerebakan, Writer in Residence

Feature / 15

16 / Find Your Sea Story

FINDING A SEA STORY

My sea story started long before I was born and I didn’t truly find it, until very recently. This past October I had the great fortune of meeting Admiral James Stavridis at the Museum’s America and the Sea Award Gala which honored him for his many contributions to the American maritime culture.

His words when accepting the award are what truly impacted me. He reflected upon his grandparents' immigration from Smyrna— once a Greek city and now Izmir, Turkey—aboard a fishing vessel. It was a difficult journey clouded with heartbreak and uncertainty. Seventy years later, he returned to that area as a Captain in the US Navy. As he stood aboard a US Naval ship looking to where his grandparents once fled, he said it was a full circle moment for him. I sat there listening to him and I couldn't help but draw connections from his story to my own. Both of my grandfathers fled that area in the 1920s with their families to find refuge in Greece. The journey nearly ended the life of my paternal grandfather, my pappou Tony, who was just six months old at the time. His survival is where my sea story begins.

My grandparents and parents eventually immigrated to America, barely knowing the language and with nothing to their name. What they had was an incomparable work ethic and a fierce commitment to family. My pappou Tony was a craftsman and worked as a carpenter. I remember visiting my grandparents as a child, spending weekends at their house in Norwalk, Connecticut, where my grandfather had his woodshop. The sounds of a saw and the smell of fresh wood instantly take me back to that place. It’s a part of my very existence.

own. I never could have imagined that that fateful journey across the sea by my ancestors could decades later lead to me becoming the head of marketing and communications for the largest maritime museum in the nation. Just as Admiral Stavridis felt, I too feel that I have reached a full circle moment in my family’s sea story. As I work daily to manage communications plans and marketing strategies, sometimes I think about what it must have been like to live my grandparents' life—crossing the sea into an unknown world and working tirelessly to provide the basic necessities for their family, never too proud to do what was needed.

“Both of my grandfathers fled that area in the 1920s with their families to find refuge in Greece. The journey nearly ended the life of my paternal grandfather, my pappou Tony, who was just six months old at the time. His survival is where my sea story begins.”

My pappou Tony outlived all my grandparents and died five years ago at the age of ninety-four. He never got to visit me here, but when I miss him, I walk down to the woodshop in the Shipyard, I take a deep breath, and feel as if he's right there by my side looking at all the incredible work being done at this Museum. He would have loved it here. I can picture him taking his daily walk along the river, perusing the boats, and ultimately finding his way to the shipyard woodshop so he can tinker with all of the tools. He would most certainly drive the shipwrights mad with all his recommendations.

That is my story. In the following pages you'll read additional sea stories from individuals and about items from the Museum's collections, buildings in the Village, and vessels in our Shipyard. My hope is that you will be compelled to explore the Museum to learn, discover, reveal, and find your sea story. In doing so, I believe you'll also find that the sea connects us all.

Through my grandparents’ and parents’ examples of perseverance, dedication, and hard work I have been able to forge a path of my

Sophia Matsas, Vice President of Marketing and

Communications

Find Your Sea Story / 17

Adversity to Inspiration: A MAP Sea Story

When she was young, Camila Lee Santos Rivera feared the ocean and its almost endless expanse. But her feelings have changed: “When I think about the ocean, the first thing I think of is peace and how being around it makes me calm.”

Camila is a participant in the Mystic Seaport Museum Maritime Adventure Program (MAP), which provides experiential maritime education opportunities anchored in positive youth development to under-resourced young people. Camila’s journey from ocean adverse to inspired is an example of the success for the program. Through exposure to maritime experiences like sailing, rowing, navigation, and boat construction, MAP participants build their skill sets, employability, and self-confidence. Recently, Camila joined an additional ocean-related extracurricular program that is aiding in her future career options, becoming a cadet with the Navy Reserve Officer Training Corps in her school. Camila shared, “In the future, I would like to get involved with the Coast Guard and Navy. Those two branches are ocean-related and most of what you do is on a Navy/Coast Guard vessel. For example, the Navy has ships and underwater craft for exploration and research. And the Coast Guard patrols America's coasts and international waters using cutters, aircraft, and intelligence to detect, intercept, and disrupt dangerous and illegal activities such as drug smuggling and human trafficking on the water. I feel like in the future, if I

accomplish my goal, [the ocean] is going to be a big part of my life, because the [Museum] put meaning to it, and I felt welcome.”

In the Museum’s Maritime Adventure Program, Camila has taken on a leadership role. Her natural charisma easily helps her stand out and inspires other students to follow her example. Camila, in working through her uneasiness with the sea, has found a niche for herself that now provides leadership opportunities and a sense of calm. Her success in the programs she's involved in shows just a few ways that the ocean can create opportunities and define a sense of self through risk, adventure, and reflection.

Kendall Wallace, Program Coordinator, Maritime Adventure Program

“I feel like in the future, if I accomplish my goal, [the ocean] is going to be a big part of my life, because the [Museum] put meaning to it, and I felt welcome. ”

18 / Find Your Sea Story

Camila Lee Santos Rivera learns powerboat handling in the Museum's Maritime Adventure Program.

A BRILLIANT SEA STORY

When eighteen-year-old Brooke Foran stepped aboard Brilliant, she had already decided that she would make a career out of sailing, but by her second day on board, Brooke was seasick. That night she wrote in her journal that she was worried she might not be cut out for sailing after all. The next day, however, she had gotten comfortable with schooner sailing and she wrote, “I don’t care how seasick I get, I’ve never been this content in my life.”

Brooke had been accepted to Maine Maritime Academy but deferred her enrollment in favor of finding a job on a schooner.

“The trouble was, I didn’t really know how to go about getting a job on a boat, so I ended up messaging different boats on Instagram.” Her eagerness paid off and she was hired on the classic schooner Tyrone, where she spent a season sailing as a deckhand. After sailing on Tyrone, Brooke was hired as a deckhand on the recently restored schooner Ernestina-Morrissey, a fishing schooner originally launched in 1894. On Ernestina, Brooke voyaged from New Bedford, Massachusetts, to Galveston, Texas, and back again, a trip of more than 5000 miles. Brooke laughed when she talked about all that she learned on Ernestina, what it’s like to sail around the abandoned oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, and how she now knows for a fact that the Atlantic in March is “really unpleasant,” and through it all how much she enjoys voyaging on sailboats. “Brilliant set a tone for my career,” Brooke said of her time aboard the Museum's schooner. “It showed me what sailing and voyaging can be like.”

On schooner Brilliant, the goal is to pass along as much of the vessel operation as possible to the young sailors aboard so that when their voyage is over, they take with them a real sense of ownership, a sense of self, and a sense of belonging. Students tell us that this “realness” is what makes their time on board so special.

Brooke is now enrolled at Maine Maritime Academy where she is pursuing a degree in Marine Transportation Operations and an Unlimited Tonnage Third Mate License. Brooke also sails on the Arctic schooner Bowdoin, Maine Maritime’s traditional sailing vessel.

Stories of self-discovery, skill development, and belonging are repeated every year on Brilliant and it is exciting to witness season after season young people discovering and uncovering character and skill while sailing aboard the Museum’s special schooner.

Sarah Armour, Captain, Schooner BRILLIANT

Find Your Sea Story / 19

Brooke Foran bending on Schooner Ernestina-Morrissey's mainsail

Life's Greatest Lessons Learned at Sea

In my junior-high-school years I became enamored of the sea adventure tales of one Howard Pease, an American writer of adventure stories. The lure of the sea grew—exotic ports, foreign languages, tough work, and an array of characters (some of them nefarious!). But I had to wait until the summer before my senior year in college, in June 1963, for my first trip to sea.

Ships out of New York needed extra hands in the summertime; so, at age 19, this rather sheltered, naïve, only-child got his merchant marine credentials (Z-card) and showed up at the National Maritime Union Hiring Hall on 7th Ave and 13th Street in New York City. I got a job on the SS Santa Elena—a small Grace Line passenger ship headed out that very afternoon to ports in the Western Mediterranean and Tangiers.

On my way to the ship, I was overjoyed to be on my own in the world—independent for the first time—with a very cool summer job. I was going to see the world—and get paid for it! I eagerly reported for work. Then, as I looked through a porthole as the ship pulled away from the pier it dawned on me that the Statue of Liberty was heading in the wrong direction! That day I learned how euphoria can be easily tempered

by abject fear! But I learned to pull my own weight and to show respect for my bunkmates, all of whom were full-timers aboard the Santa Elena

My thirteen voyages on merchant ships, in the summers of 1963 through 1967, were my introduction to the worlds of international business, foreign languages, labor unions, the federal government, behavior in the workplace, and the vicissitudes of the sea. Not to mention my introduction to the beauty and wonders of Southampton, Lisbon, Gibraltar, Tangiers, Barcelona, Cannes, Naples, the Baltic countries, the Caribbean, and South America!

“ My thirteen voyages on merchant ships . . . were my introduction to the worlds of international business, foreign languages, labor unions, the federal government, behavior in the workplace, and the vicissitudes of the sea. ”

Fast-forward to the summer of 1969, as a cadet at the Naval Officer Candidate School in Newport, Rhode Island, I visited Mystic Seaport Museum for the first time. And there, tied up at the pier, was the Charles W. Morgan. Now nearly 60 years later, I proudly volunteer my time at Mystic Seaport Museum. Mon dieu, if I thought being a Merchant Seaman in 1963 was demanding, I’m now learning what it was like—in 1863! And I love sharing that insight with Museum visitors!

Jeremy Sachs, Mystic Seaport Museum Volunteer

20 / Find Your Sea Story

Museum Volunteer Jeremy Sachs next to the whaleship Charles W. Morgan at Mystic Seaport Museum in 1969.

I grew up within minutes of Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, and my summers centered around going to the beach at Ocean View on the bay and Virginia Beach on the ocean. In the late 1960s, we had the good fortune to build a modest cottage in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, right across the street from one of the best surf spots in the area. It was a magical time on the Outer Banks as the area was still an undiscovered jewel as a vacation destination for swimming, surfing, and relaxing on the beach.

My brothers and I started surfing in the 1960s, and the Outer Banks offered some of the best waves on the East Coast, especially after Labor Day. Fall provided a double bonus as the air and water temperatures were still delightful and the summer crowds had left. The phrase “catch a wave and you’re sittin’ on top of the world,” from a Beach Boys song, captures the exhilaration of surfing. When I would “drop in” (catch) a wave the surrounding world

catch a wave and you’re sittin’ on top of the world

vanished, and it was just me on my board, interacting with the swirling and crashing water. The ultimate and most exciting experience was to “get tubed,” where the lip of the wave pitched out and curled over my head encasing me in a fleeting, watery

tunnel. The Outer Banks often experienced large and dangerous surf, and the iconic Coast Guard life-saving stations provided a reminder that the ocean can be a perilous place, but the joy in a moment of surfing drew me back time and time again.

After graduating from college, I moved to Connecticut and fell in love with the waters off New England, which offered a very different saltwater experience than the Outer Banks. I took up fishing and I’ve enjoyed over 45 years of boating in and around Fishers Island Sound. The sea is an ever-changing environment that never ceases to provide joy and relaxation, and the feel of the sand between my toes and the smell of the seaweed laden saltwater transport me instantly back to my days at the beach. I hope to never live far from the ocean’s shores.

Find Your Sea Story / 21

Museum Member and Volunteer Bill Gardner surfing in the Outer Banks of North Carolina in the 1960s.

Bill Gardner, Mystic Seaport Museum Member

Built in 1758 as the home of Lydia and Samuel Buckingham and purchased in 1833 by William Hall, Jr., son of William Hall, Sr., a New York import merchant, the Buckingham-Hall house sat on land in Old Saybrook for nearly 200 years on a road leading to North Cove at the mouth of the Connecticut River. Historical accounts describe the mouth of the River as being rich in bass, chequit (weakfish), eels, and crabs, the flats abundant with clams, and the River and creeks alive with shad and salmon, advantages Algonquin Nehantic people recognized long before the arrival of Europeans. Deep harbors also supported a prosperous shipping trade with the West Indies. From the home’s windows the Halls witnessed 19th-century life in all its variety: farmers moving goods to market, coastal and foreign trading ships sailing up and down the river, and travelers passing down the road to the ferry. Though access to the river made goods from New York readily available, most of the foods and the fabrics needed for daily life were produced on the farm.

When construction of a new highway bridge across the Connecticut River threatened this structure with demolition in 1951, it was removed from harm’s way and gifted to the Museum by the Connecticut Highway Department in exchange for the promise of preserving it, and this handsome example of colonial architecture was barged up the Mystic River to its new home on the river’s edge where it sits today.

Since that time, thousands of visitors have been welcomed through the gracious double-door entry. Inside, guided by the expertise of Interpretation staff and with the curiosity and willing imagination of visitors, conversations turn naturally to topics of domesticity and women’s roles. In the Buckingham home, as in all households at that time, unless Lydia Buckingham could depend on family help or could afford hired or indentured help or had slave labor, the demands of providing food (and clothing) fell on her shoulders, consuming nearly all her time and energy.

By the early 1800s, lifestyles of women and men, especially along coastal areas, were responding to myriad changes and Lydia's kitchen would see the effects in new ways of food preparation and preservation, new utensils and even in the types of foods served to family and guests. Gathered by the massive fireplace (the masonry of the original 1600s house), the kitchen is the perfect setting to talk about what is simmering in the pot.

18th and 19th-century life in this coastal home was filled from dawn to dusk, season to season, with hard work, business transactions, and the voices of visiting friends and relatives. The kitchen with its huge hearth is now the site for open-hearth cooking demonstrations, and the garden in the back is the source for much of the fresh produce. Quilting and weaving are practiced in the house, and 19th-century dressmaking classes are also hosted. From its original setting along the river’s edge at the mouth of the Connecticut River to the banks of the Mystic River, the Buckingham-Hall house serves as an example of coastal family life in early New England.

Nancy Seager, Research Assistant

The Buckingham-Hall House

22 / Find Your Sea Story

Museum Interpreter Aidan Evenski performing cooking demonstrations in the Buckingham-Hall House.

The Cooperage

The Cooperage exhibit sits in the recreated 19th-century sea port village along the Museum’s waterfront. The building, former ly a barn that was part of the Greenman Brothers’ property, was moved to its current location almost directly across from the stern of the typical features of a cooperage: a hearth large enough to work in while firing casks, a crane with a block and tackle and chine hooks, and a loft for storage. The building was opened to the public as a Cooperage in 1964. The trade of coopering, like the building itself, is central to the sea stories told at Mystic Seaport Museum.

Coopering dates to ancient times and was an essential trade in the maritime world. In New England, coopered items were a vital element in life both on land and at sea. Wooden containers made from staves and hoops served many storage purposes. They were found in homes in the form of buckets, washtubs, and butter churns, just to name a few. Aboard ship they held provisions, various kinds of cargo and, on certain fishing and whaling vessels, the catch. A quick look around the Museum waterfront will reveal the many ways that coopered items were used in the whaling and maritime shipping industries.

Casks were the standard shipping container of the 19th century. Not only were they sturdy and able to be made watertight, but the shape—with the widest section in the middle—allows a cask to roll easily. A single person can move large amounts of weight with relative ease. Coopers made casks that could carry liquids, such as whale oil, water, molasses, or spirits, in a process known as wet coopering. They also made slack casks designed to hold dry goods like apples, potatoes, and manufactured goods. On a ship such as the Charles W. Morgan, casks held the oil rendered from whales. The Museum’s whaleboats on exhibit contain an array of other coopered items used in the whaling industry, including line tubs, a water breaker, a piggin, and a lantern keg—essential items for any whaleboat in the 19th century.

Large, intermodal shipping containers eventually replaced casks as the shipping container of choice. Containerization began in earnest in the 1950s and 60s and rapidly transformed the waterfront and the shipping industry. In those same decades, Mystic Seaport Museum was planning to open the Cooperage as an exhibit on campus. By the mid-1960s, coopering was a vanishing craft, and the Museum had to look far and wide to find someone with the skills to teach the next generation of coopers. Today, Museum staff carry on the tradition of making handmade coopered items, including casks, buckets, and whalecraft for the Museum, keeping those historic skills alive.

Maria Petrillo, Director of Interpretation

Find Your Sea Story / 23

Trade Specialist Sam Pierson planing a barrel stave in the Cooperage.

The Charles Mallory Sail Loft

Charles Mallory had only recently left his apprenticeship in New London when he arrived in Mystic and set up business as a sailmaker in 1816. Twenty years later, in 1836, Mallory was expanding his investments into whaling and shipbuilding, and it was at this time that he purchased what is now known as the Mallory Sail Loft. The loft was most likely built in the early 1830s, but the exact date of construction is unknown. Charles Mallory went into partnership with William N. Grant soon after, and the business of Mallory and Grant, Sailmakers, lasted until 1852. In 1853, the loft was rented to Isaac D. Clift, Mallory’s son-in-law.

Charles Mallory was part of Mystic’s booming shipbuilding industry during the mid-19th century. Mystic shipyards produced more vessels than almost any other port of a similar size in Long Island Sound. Sailmaking and canvas work, along with many other ancillary trades, were essential to the success of the local shipyards. Sailmakers designed, built, and repaired sails for the many vessels that were launched and outfitted in Mystic—vessels that included anything from small, local fishing smacks to large, three-masted clipper ships bound for California.

The shipbuilding industry in southern New England declined after the 1870s and was replaced by manufacturing. The sail loft was no longer needed, and the building was used briefly as a hoop-making shop and a coal-storage business. The loft was

eventually sold to the James F. Lathrop Company in 1928. After many years serving as a storeroom for the Lathrop Company, Walter Lathrop offered the loft to Mystic Seaport Museum in the 1950s to preserve the historic structure and save it from demolition. The Mallory loft was lifted off its foundation, floated down the river, and established on its current site in 1951. The dedication to preservation can be seen in the fact that not only was the wooden structure moved, but also the stone foundation was carefully disassembled, labeled, and then reassembled on the current site.

Today, the Mallory Sail Loft continues its life as a working sail loft. Mystic Seaport Museum staff continue to use the original loft space to repair and construct sails for the Museum using traditional skills and materials. Most recently, the Museum awarded the Interpretation Department a Mallory grant to fund a sailmaking course in the loft. Sailmaker Mark Shriner from the Orkney Islands traveled to Mystic Seaport Museum to teach six staff members to draft and sew sails using both traditional and modern methods. Staff who participated in the class are working toward expanding the loft's capacity to construct sails and teach classes to students of all ages. The legacy of sailmaking continues in the Mallory Sail Loft today.

Maria Petrillo, Director of Interpretation

Museum Interpreter Jim Mortimer constructing sails in the Mallory Sail Loft.

24 / Find Your Sea Story

Stories from the Collections

The Museum’s collections are rich with sea stories. Many of the artifacts representing those stories can be seen in the Museum’s exhibitions, but some stay hidden in the vaults awaiting the opportunity to shine. Artifacts such as a surgeon's medical kit and Irving Johnson's homemade compass are representative of the many stories tucked away.

The Museum recently acquired a fully equipped ship’s medical chest that dates to the mid-nineteenth century. Twenty-eight of the thirty-five bottles are attributed to Epes Sargent of 31 Old Slip, Up Stairs, New York, whose father was a shipmaster. Included in the mahogany chest’s many compartments are herbs that we still see today such as chamomile flowers, cinnamon, and spearmint, as well as other substances that have been phased out of medical practice such as mercurial ointment, purging pills, and sulfur powder. The other medical equipment in the chest includes two teacups, a brass balance with weights, a cow-horn spoon, and a crystal mortar and pestle. The most intriguing items can be found in a hidden compartment in the bottom of the chest—several handwritten prescriptions dating to 1854 as well as one mysterious envelope simply labeled “Poison.”

In 1930, Sir Thomas Lipton competed in the America’s Cup Race on his yacht, Shamrock V, losing to the yacht, Enterprise. For the

The Letters of William Peter Powell

In the 1820s, the American Seamen’s Friend Society (ASFS) was established with the mission of improving the “social and moral condition” of sailors. The Society opened “sailors’ homes” for sailors to stay in while they were on shore between voyages, which served as reputable alternatives to seedier boarding houses and brothels frequented by sailors. In the manuscript collections in the Museum’s G. W. Blunt White Library, we have the archives of the ASFS, including records from the Colored Sailors Home in New York. The Colored Sailors Home was specifically for non-white sailors. Sailors may have had a degree of equality at sea, but ashore, nonwhite sailors were subject to segregation and prejudice.

In this collection are letters from William Peter Powell, Sr., the steward of the Colored Sailors Home in the 1860s. Though his feet remained on land, he gave sailors of color a safe and welcoming place to stay when

voyage back home, world renowned sailor Irving Johnson joined the crew as first mate. Upon entering the Gulf Stream, they encountered a hurricane that created waves strong enough to break the deck bolts that secured the binnacle sweeping it, and the steering compass, overboard. Using parts of other broken compasses found aboard, Irving rigged a makeshift compass and mounted it on the steering-gear box. To see the compass at night, the crew devised a wick from sail twine and a canvas case to keep the wick dry and protected from the wind, and they used this homemade contraption for the remainder of their nineteen-day journey back to London, despite the flame going out several times a night!

These and thousands more sea stories are part of the Museum's collections.

they came ashore. His letters to the board of the Society describe the challenges his boarders faced before arriving at his door: prejudice, beatings, swindlings, and muggings. In one particularly memorable letter, he describes how he left the United States temporarily in order to have his children educated in England, because “owing to the prejudice against Color” in New York, they did not have equal access to quality schooling.

Even in the North, in the company of abolitionists, Powell had to repeatedly advocate for resources for his boarders. He describes their exemplary behavior despite violence committed against them, being forced to justify to the board why they should spend money to house and feed these men. Through these letters, we watch him carefully balance the desire to tell the board members the truth of what it means to be a Black sailor on shore with the need to maintain a polite tone in order

to get what he and his boarders need. Powell’s connection to the sea came in the form of caring for those who traversed it, standing up for them again and again in the face of a country that was content to toss them aside. His letters are a treasure in the Museum’s collection because they provide a remarkably unique and poignant snapshot of a moment of turmoil in US history and illustrate what it was like for a Black community leader to navigate at that time. It can be easy to fall into the trap of simplifying history, and collections like this remind us of its complexity and challenge our expectations.

More sea stories from historically silenced voices can be experienced in Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea, now open in the Stillman Building.

Emma Burbank, Registrarial and Research Assistant

Find Your Sea Story / 25

Homemade Compass Accession Number: 1975.21

Irving Johnson

Lydia Downs, Collections Assistant and Deaccession Specialist

The Admiralty Model of HMS Burford: A very British Artifact with an American Connection

Sometimes, objects in museum collections are shrouded in the stories we are told or that we read in early catalog records. On occasion, some of those stories are not completely true. Such is the case with my understanding of the history of a wellknown model of the HMS Burford, which came into the Museum’s collection in the 1970s.

When I offered to write about this iconic British Admiralty Board model and its American connection, my understanding of its story was that it was presented to its first commander, Admiral Edward Vernon, when it was built in 1722. I was told that George Washington’s half-brother, Lawrence Washington, served as a British Navy lieutenant on HMS Burford under Admiral Vernon and that Lawrence admired his commanding officer so much that he renamed the family home in Virginia, Mount Vernon, after him.

When I dug into the history of this model, I was surprised to learn that some of the story I had known for years was not quite

true! Further investigation revealed that the model was likely crafted several years after the Burford was built (the second of three consecutive 70-gun third rate ships so named). Burford’s first commanding officer was not Vernon, but rather a Captain Charles Stewart. Admiral Vernon did not command Burford until 1739, a few commanders later, and was technically commanding a squadron of ships using the Burford as his flagship. It was at this time during the War of Jenkin’s Ear that Vernon gained fame for the capture of the great treasure port of Porto Bello from Spain, in what is now Panama, making good on his boast of using only six ships to accomplish the task.

Lawrence Washington came on the scene when Vernon attacked the Spanish city of Cartagena, in what is now Colombia, in 1741. Lawrence received a commission as a British Army (not Navy) captain serving in a Virginia colonial regiment that fought in the aforementioned war. On the way to Cartagena, he was posted to Vernon’s new flagship, HMS Princess Caroline, where he likely

first met the admiral. Lawrence must have made an impression, since shortly after he received an appointment as Captain of the Marines aboard the flagship. He served with distinction under Vernon, even though the Cartagena expedition ultimately proved a disaster. Lawrence did in fact, admire Admiral Vernon enough to name his family home “Mount Vernon.” However, he never did serve on HMS Burford.

The early history of the Burford model is murkier. It was crafted sometime between 1722 and the 1750s, likely for Admiral Vernon. It resided with the Vernon family until 1929 when it was sold at Sotheby’s to the Morgan family (of J.P. Morgan fame) who donated it to Mystic Seaport Museum, where it is a centerpiece of the Museum’s ship model collection.

Chris White, Collections Manager

26 / Find Your Sea Story

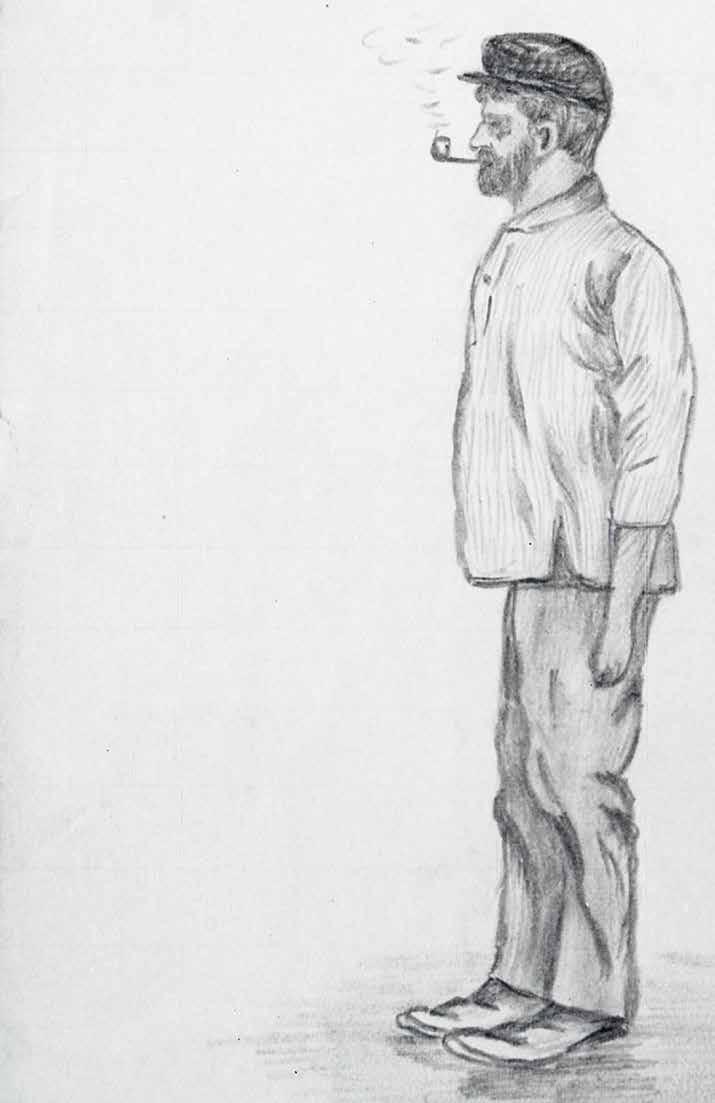

The Packard Sketches— A Sea Story Mystery Solved!

The Down Easter Benjamin F. Packard, a three-masted 244-foot vessel built in 1883, sailed cargo around the world until the vessel was retired in 1927. Irreparably damaged in the hurricane of 1938, the vessel was going to be scuttled in Long Island Sound when Mystic Seaport Museum Secretary Carl C. Cutler wrote a passionate plea to Museum President C. D. Mallory to bring the ship to the Museum as its first tall-ship acquisition. While Cutler’s plea was unsuccessful, he and Mallory reached a compromise. The beautifully crafted aft cabin featuring Italian marble, satin sofas, and exotic woods was disassembled and preserved by the Museum. The pieces were kept in storage until 1975 when they were reassembled, and the cabin was put on exhibit. The Museum reached out to the public to find additional artifacts, and Elbert C. Mansur, who collected Packard materials, responded. He allowed the Museum to photograph drawings done by a crew member known only as Dean. The photographs hung unnamed in the exhibit for nearly fifty years, until a recent search through crew lists and genealogical research revealed the names of eight individuals in the drawings: Davis N. Dean, George Oya, Edward McDonough, W. Martin, Ed or J.R. Jackman, Patrick Flynn, John Miller, and Joseph Patrick. Davis Newton Dean, a 19-year-old from Mandan, North Dakota, is the artist. Dean left his quiet hometown to seek adventure during the Klondike Gold Rush and sailed aboard the Benjamin F. Packard from May 1898 to March 1899. Three weeks into the voyage, Dean jammed his finger into a brace block, the injury nearly costing him his hand, and he was out of commission for nearly two months, which is most likely how he had the time to draw his compatriots.

The Packard was under the command of the infamous Captain Zaccheus “Tiger” Allen, who controlled his crew through brutality and neglect. As a result, the voyage from Tacoma to Hong Kong was marked by tragedy. George Oya, the Japanese

cook, died from an unknown gastrointestinal illness without medical attention. We now know that this is the cook Dean drew that “gave up the ghost.” Dean’s illustration of Ned McDonough is Edward McDonough, a native of New Orleans, who was shanghaied. McDonough stood at the helm when Harry Paige, a young epileptic sailor, fell from the rigging into the sea. McDonough tied a rope around his waist and was about to jump overboard to save Paige, but Captain Allen stopped him and refused to turn the ship around or throw out a life ring because he claimed that he did not see Paige reappear on the surface. After the Packard arrived in New York, newspapers chronicled McDonough’s reports from the mates of savage beatings and Captain Allen’s heartless inaction regarding Harry Paige.

Captain Allen discharged the entire crew upon reaching Hong Kong, except for Dean, whom he trusted. Dean continued his sailing adventures after leaving the Benjamin F. Packard. A year later, on the ship Cyrus Wakefield, Dean would meet the same fate as Paige, drowning at sea after falling from the rigging. Dean was a beloved shipmate, and newspapers reported, “he was a great favorite with everybody on the ship, and officers and crew have not yet recovered from the shock caused by his death.”

With continued research we hope to learn the stories of the remaining sketched individuals. The quarters of the Benjamin F. Packard where Dean and Captain Allen once stood are open to visitors on the second floor of the Stillman Building. The sketches can be viewed in the exhibit and on the Museum's website at www.mysticseaport.org/packardsketches

Amanda Keenan, Interpreter

Find Your Sea Story / 27

Dean's sketch of crewmate Edward "Ned" McDonough.

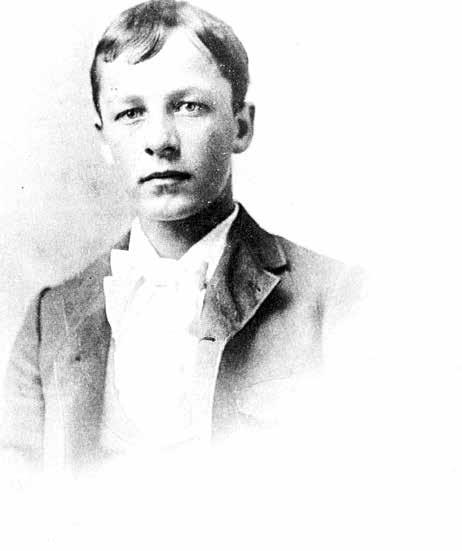

Davis Newton Dean, sketch artist

Asherah: The Reinvention of Underwater Archaeology

Dr. George Bass, a young PhD student immersed in the study of archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania in 1959, found himself faced with an extraordinary opportunity. Invited to lead an excavation off the coast of Turkey, where a Bronze Age ship lay submerged, he faced a challenge. In those days, conventional wisdom deemed true archaeological exploration underwater as an impossible feat. But Bass, undeterred by skepticism and fueled by intrigue, accepted the challenge with determination. Learning to scuba dive specifically for this archaeological exploration, Bass ventured beneath the waves and quickly realized the limitations imposed by conventional diving gear. The efficiency of locating and mapping shipwrecks, along with the application of traditional archaeological techniques underwater, were severely hampered. Yet, from these challenges emerged a revolutionary idea: a two-man submarine. The concept of a submersible promised to address various concerns. It would extend the duration of dives, remove depth limitations, and provide a centralized control

for archaeological supervision. Thus, the decision was made, and in 1963, the University of Pennsylvania commissioned the construction of Asherah, named after the Phoenician sea goddess, to undertake the world's first scientific shipwreck investigation.

Constructed by the Electric Boat Division of General Dynamics in Groton, Connecticut, Asherah was launched on May 28, 1964, marking a milestone as the first commercially built American research submersible. With its compact size, weighing 4.5 tons and powered by rechargeable batteries, Asherah could navigate depths of up to 600 feet and move with agility similar to a helicopter.

Joined by Asherah, the team embarked on groundbreaking scientific expeditions. From exploring a Bronze Age wreck off the southern coast of Turkey to documenting an ancient Byzantine shipwreck near Yassi Ada in 1967, Asherah's capabilities revolutionized underwater archaeology. Utilizing innovative techniques such as underwater aerial photography and stereoscopy, Dr.

Bass and his team pioneered new methods of site mapping and shipwreck identification.

Despite the vessel’s many contributions, Asherah was not without its own limitations. Navigation equipment was lacking, visibility was limited, and operation was complex. These challenges, coupled with soaring insurance premiums, led to the University of Pennsylvania's decision to sell the vessel in 1969.

Nevertheless, Asherah's legacy endures as a testament to the transformative impact it had on underwater archaeology. The vessel’s pivotal role in reinventing archaeological exploration beneath the waves propelled the industry forward, laying the groundwork for future discoveries. Today, Asherah is on display at Mystic Seaport Museum as a symbol of innovation and exploration in underwater archaeology.

Sherri Ramella, Editorial Director

28 / Find Your Sea Story

The Little-Known Story of Evinrude

Our personal sea stories all start somewhere, and while mine does not start in an Evinrude boat, it was in a similar size and shape vessel where I had my first command at sea somewhere around the age of eight on a Michigan Lake. I think it is this connection that has always made the Evinrude one of my favorites in the Museum’s collection—not to mention that the Evinrude story also starts with ice cream!

A row against a headwind while crossing a Wisconsin lake in the summer of 1906, with ice cream in hand for the future wife of mechanic Ole Evinrude, resulted in a shared melted ice cream and the inspiration for a quicker ride—the outboard motor. Of course, many mariners are familiar with the Evinrude Outboard, but the lesser-known part of that history is the Evinrude boat.

Many of Ole Evinrude’s early outboards were placed on small vessels of the time which were designed to be rowed from the center of the boat where the hull was made fullest with the ends narrowing. Fitting an outboard onto this design proved difficult, and the narrow stern did not have the buoyance to support the very heavy early outboard motors. Ole’s solution to this was to market a series of small boats designed with a fuller stern with a reinforced transom and stern sheets designed for seating of

the motor operator. As the advertising stated, “a rowboat designed for outboard detachable motors.”

The Evinrude boat in the Museum’s collection is serial number 3308, likely produced in 1916, and at the time sold for about $80. The sturdy vessel is constructed of white oak and cypress and spent most of its life on a New Hampshire lake before being donated to the Museum by Leon Cote in honor of his father.

Evinrude’s boat design has impacted the way we travel on the water nearly as much as the outboard motor itself. The wide transom and increased buoyancy aft have become standard for nearly all power-driven vessels. My first command at sea at age eight might not have been as successful without Evinrude's significant changes in boat design! I wonder what Ole Evinrude would think of today’s large outboard powered vessels with multiple 600 horsepower outboards on the transom—a big step from the 3-horsepower motor that would have been used on the original Evinrude boats.

Chris Gasiorek, Senior Vice President of Watercraft Preservation and Programs

Find Your Sea Story / 29

Evinrude vessel in the Museum's small watercraft collection.

A FINE LINE

One hundred and one years ago Butler “Butts” Whiting kitted out his Star Class hull with a WWl airplane wing. Morris Rosenfeld & Sons were there to photograph it. Whiting recognized the immense power and efficiency of the fixed wing in that it allowed tremendous lift and reduced forward friction. However, according to a story in the “Hurrah’s Nest” from The Rudder in 1923, the power of this rig was challenging to master in a Star, which is not surprising as the vessel was not designed to integrate such aeronautics. “While it cannot be said that the rig is perfect, there are great possibilities for its modification in the future—but then, we do not care to prophesy.” (The Rudder, September 1923, p. 31)

Prior to Whiting, W. Starling Burgess, who is better known for his extraordinary accomplishments in yacht design, including the America’s Cup 1930s J-Class winners Enterprise, Rainbow, and Ranger, was building and flying airplanes. In 1909 Burgess piloted the first airplane in New England, and in 1915 he was awarded the Collier Award for his “air yacht” with John Dunne, the Burgess-Dunne Model BD-1, a hydro plane that reflected his understanding of hydrodynamics in hull design and aerodynamics in lift.

A century later, we have seen some incredible “possibilities for its modification” in both yachting and commercial vessels, which exploit the fine line between flying and sailing for speed and efficiency. In racing, the new generations of racing vessels from the America’s Cup and Sail GP represent the height of aeronautical technology, exploiting wing technology in fixed rigs and hydrofoils. In 2013, we saw America’s Cup multi-hull foiling AC72 with fixed wings the size of a Boeing 747-400 reaching speeds of 45 miles per hour. Sail GP F50 has more recently been recorded at over 60 miles per hour.

The America’s Cup has always been a hotbed for technological innovation with some of the more successful design elements percolating into other industries. One of the most obvious at the moment is the influence on modern hybrid shipping designs as companies race to find solutions to strict new regulatory lower-carbon requirements. To complement alternate fuel sources, sails are being revisited as an auxiliary or primary power to achieve these goals. In 2023 the cargo vessel Pyxis Ocean, retrofitted with two 123’ foldable rigid sails called WindWings, traveled from China to Poland by way of Brazil and Tenerife to prove the

sails could reduce fuel consumption by 20%.

It is likely new technology cultivated for the 2024 America’s Cup in Barcelona will influence the next generation of shipping’s efforts to decarbonize. After three America’s Cups of foiling multi-hulls with fixed sails, AC sailing has for the second time returned to monohulls with soft sails in the AC75. With ballasted canting T-wing foils, a t-wing rudder, and looking like a cross between a Klingon war ship and a praying mantis, these rockets reflect the AC motto: “AC75: Designed to Fly.” The past is the future.

Somewhere “Butts” Whiting and Starling Burgess are smiling—they saw this coming a mile away.

Christina Connett Brophy, Senior Vice President

Pyxis Ocean is an MC Shipping Kamsarmax vessel retrofitted with two WindWings®— large solid wind sails developed by BAR Technologies— installed vertically to catch the wind and propel the ship forward, reducing the fuel needed to travel at the same speed as a conventional ship. ©Cargill

Butler "Butts" Whiting, airplane-wing-rigged boat. Morris Rosenfeld & Sons, 1923 negative #1984.187.10231F