Collections: A Maritime Treasure Trove

MYSTIC SEAPORT MUSEUM MAGAZINE

is a publication of Mystic Seaport Museum.

PRESIDENT

Peter Armstrong

CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD

Richard W. Clary

EDITOR

Sherri K. Ramella

editor@mysticseaport.org

DESIGN

Susan Heath

CONTRIBUTORS

Walt Ansel

Sarah Armour

Debra Schmidt Bach, PhD

Jenny Carroll

Liz DeArruda

Bridget Delaney-Hall

Michael Dyer

Elysa Engelman, PhD

Chris Freeman

Katherine Hijar, PhD

Katharine Katin

Brian Koehler

Tim Kusterbeck

Mirelle Luecke

Shannon McKenzie

Makenzie Metivier

Margaret Milnes

Laura Nadelberg

Nick Parker

Leah Prescott

Maribeth Quinlan

Krystal Rose

Rebecca Shea

Allison Smith

Quentin Snediker

Erin Spiegel, Delamar Hotel Collection

PHOTOGRAPHY

Tom Daniels

Delamar Hotel Collection

Dan Harvison

Brian Koehler

Tim Kusterbeck

Joe Michael

Mystic Seaport Museum Archives

Andy Price

Jos Sances

Ken Wilson ON THE COVER

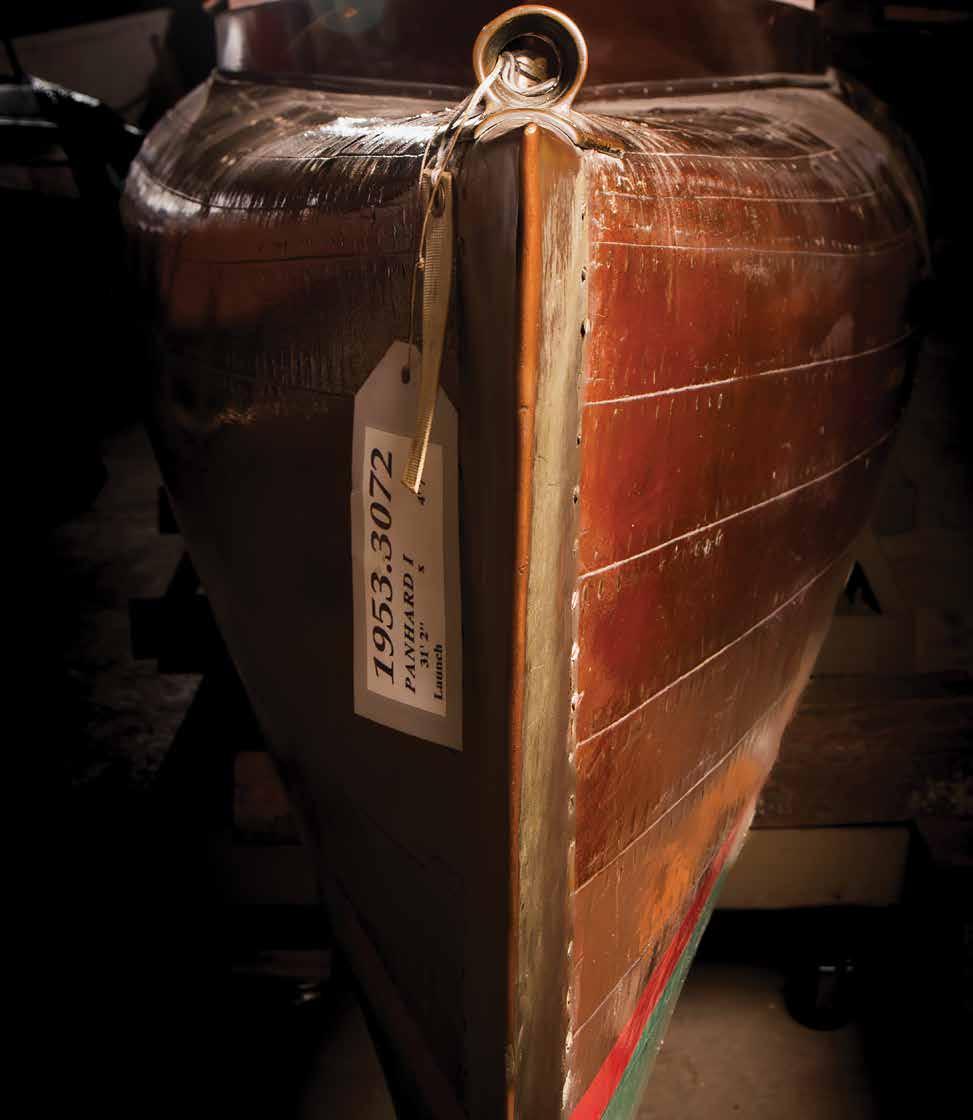

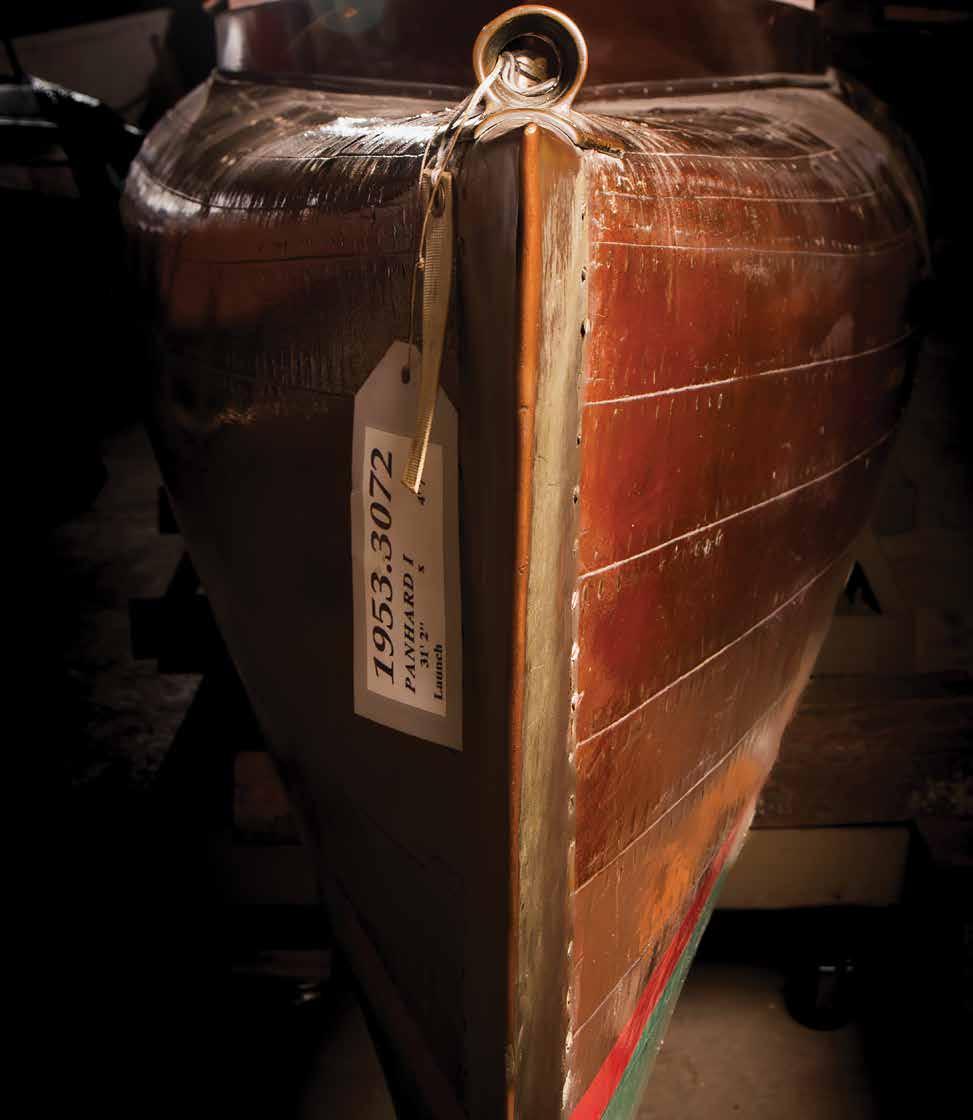

The bow of Panhard I , an exceptional 1904 gasoline launch by Elco, looms out of the dark in Museum storage. Panhard I will be featured in the upcoming exhibition of the American Watercraft Collection in the new Wells Boat Hall.CONTACT

V isitor Information : 860-572-0711

A dministration : 860-572-0711

A dvancement : 860-572-5365

M embership : 860-572-5339

P rogram Reservation : 860-572-5331

M useum Store : 860-572-5385

V olunteer Services : 860-572-5378

P lease go to the Museum’s website for information on spring and summer schedules.

MUSEUM NEWS

Work Continues on Emma C. Berry

L. A. Dunton Restoration Progresses

Wells Boat Hall: American Watercraft Collection

Now Open! Delamar Mystic

Visitor Research Impacts Visitor Experience

Treworgy Planetarium Lobby Remodel

The Museum’s Far-reaching Impact

The Summer of the Morgan

Summer Charters on Classic Yachts

Sensory-Inclusive Programming

FEATURES

75 Greenmanville Avenue

Mystic, CT 06355-0990

www.mysticseaport.org

5

5

12

AIMing Ahead: The American Institute for Maritime Studies

Monstrous: Whaling and Its Colossal Impact

SPECIAL: COLLECTIONS

Our Collections: A Maritime Treasure Trove

..........

16

Unlocking the Past: Providing Access to the Museum’s Collections

Cataloging History

Science Shines a Light on Collections

A Sea Chest, a Lamp, and Hope for the Future

The Mystery of Wanderer: A Vessel of Beauty, Deception, and Dark Legacy

Whaling Journal Sparks Scrimshaw Question

Blubber Hooks: A Whaling Era Innovation

A Figurehead: Uncovering the History of Iolanda

Wail on Whalers: With Artist Felandus Thames

Silver Creatures from the Sea

Seas of Style: Ocean Liner Posters

Collections, Ever-evolving

Optimists Join the American Watercraft Collection

UPCOMING EVENTS

31

12 16

31

Jos Sances (b. 1952), Screenprint, Here is the Sea, 2019

A Message from the President

Throughout this spring issue you will encounter stories related to the over two million objects within our collections. Many of these items have journeyed across the seas, but all have traversed time, continually unveiling their secrets to scholars, academics, and you and I.

While the term “relevancy” is often overused within the museum world, it is truly fitting when an object from the past helps us understand the present. Take, for instance, Captain Thomas Norton’s weather reports written aboard the Charles W. Morgan during its inaugural voyage in 1841. He could never have imagined that, 184 years later, scientists would study his records to explore the implications of climate change.

The task of curating, cataloguing, and digitizing these invaluable items resides with the dedicated team at our American Institute for Maritime Studies (AIMS). We have invested significant resources into AIMS, recognizing the potential for these collections, archives, and libraries to uncover insights that not only preserve our maritime heritage but also maintain its enduring relevance in today’s world.

The Museum’s relevance does not lie just in the historical objects it preserves. It is also deeply rooted in the connections we build with our visitors. In this issue you will hear from just one of the countless individuals whose life trajectory has been altered by their experience at the Museum—whether through our Conrad Camp, the Brilliant sailing program, or the inspiring activities in the planetarium or trade shops. For these individuals, the Museum’s impact runs far deeper.

If you are considering supporting the work of the Museum, whether through your time or philanthropy, please remember that we are not just keepers of history, but active participants in it. In a world that often feels fragmented, history reminds us that we all can touch and change people’s lives for the better, even if we don’t realize it—even when you are just writing down the weather.

Peter Armstrong

BRILLIANT VOYAGES are

back!

After a major nine-month-long maintenance project, Brilliant is ready for another great season! In addition to our beloved teen trips this summer, we are excited to welcome adult sailors aboard for a lineup of unforgettable voyages this fall, including day sails and two extended trips.

Here’s a sneak peek of what awaits you this fall:

Day Sails from Mystic: Sail on Brilliant in Fishers Island Sound. Learn the basics of schooner sailing or simply take in the sights!

Voyage to the Chesapeake Bay: Sail non-stop from Mystic, Connecticut, to Baltimore, Maryland, experiencing inland, coastal, and offshore sailing, along with overnight passages and assigned watch duties—ideal for experienced sailors or those seeking a challenge.

The Great Chesapeake Bay Schooner Race: Be part of one of the East Coast’s largest schooner gatherings! Race 126 miles from Annapolis to Norfolk, taking watch and contributing to the thrilling competition.

Get ready to join Brilliant for a memorable sailing season! Register at www.mysticseaport.org/brilliant .

Work Continues on Emma C. Berry

L. A. Dunton Restoration Progresses

The shipwrights working on the Gloucester fishing schooner L. A. Dunton are making steady progress. The original sheer has been restored by raising the bow 3 ½ feet and the stern 2 ½ feet. The framing timbers at the bow, comprised of the stem, knee, and knightheads, have been replaced with longlasting live oak fastened with bronze drifts and bolts. The crew is preparing the forward section of the hull for reframing by removing every third plank and installing fairing battens. A new 17-inch square by 18-foot rudder post is being shaped from white oak in the pole barn. The Dunton’s new transom is being designed, and white oak logs are sawn weekly for frames and planking.

From 1969 to 1971, Maynard Bray and shipwright Arnold Crossman, a descendant of Noank boat builders and fishermen, led the Museum’s restoration of the Emma C. Berry to its original sloop configuration. The 1866 Noank well smack, and National Historic Landmark vessel, had been donated to the Museum by Slade Dale of Bay Head, New Jersey, in 1969, and at the time was rigged as a schooner. Following the restoration, the vessel was exhibited in the water until the 1990s when required re-topping was completed by shipwright Kevin Dwyer. The vessel was then sailed as a sloop for the first time since the 1870s.

Five years ago, during a routine haul-out, the Berry’s original keel was found severely weakened by rot and worm damage, and poor deck drainage caused significant deterioration. These issues led to the Museum’s third restoration project, funded by a National Park Service grant. Due to COVID-19, work was delayed until May 2024, when the Berry was placed in the Henry B. du Pont Preservation Shipyard. Shipwrights Trevor Allen, Lloyd Meads, and Nathan Adams began work in fall 2024. In phase one, they replaced the keel, deadwood, 1/3 of the floor timbers, and three planks on each side. The hull’s weight was transferred to offset posts, and iron bolts were repl aced with bronze. The bottom was re-caulked and made watertight. Phase two will address the deck, bulwark planks, and cap rails, and a new mast will be built. The Berry is scheduled to relaunch in fall 2025.

Master model maker and shipwright Roger Hambidge has devoted time to ensuring the Dunton’s restoration is accurate. He built two ¼" scale plank-on-frame models and holds the most knowledge locally about the L. A. Dunton, having started his involvement in 1975. Historic photos of the young Dunton

tied to the Boston ice plant revealed its true sheer, which Roger used to create line drawings of the vessel’s shape. He also referenced the shipbuilder’s registered length of 104.3 feet, noted in the ship’s documentation, to determine the bow drop from hogging. Roger’s accurate Dunton lines were faired and converted to a CAD 3D model by Walt Ansel, Director of the Henry B. du Pont Preservation Shipyard.

Wells Boat Hall: American Watercraft Collection

The construction phase of the Rossie Mill renovation to create the Wells Boat Hall is well underway with completion expected in July. Thanks to generous donors at every level, we’ve raised nearly 60% of our $15,000,000 campaign goal. We’re aiming to finish the campaign soon to start installing the exhibition. Curator Pieter Roos is collaborating with design firm CambridgeSeven to finalize the exhibition plans.

The exhibit will feature 170 watercraft and 100 engines in an open floorplan exhibit hall, divided into fifteen thematic zones like Learning to Sail, Work on the Water, Beach and Board Boats, and Sailing for Pleasure and Speed. Some boats will be stacked, as in the previous storage area of the mill, with each exhibit carefully interpreted through text, images, and in many cases video. The exhibit will explore the complex and fascinating story of American watercraft. Notably, vessels like Miss Budweiser, Analuisa, Tango, and Annie will have significant interactive audio-visual displays.

To learn more about this project or to make a gift of support to help bring this vision to reality go to www.mysticseaport.org/wells-boat-hall or call the Advancement team at 860-572-5365.

Years ago, I learned to sail at Mystic Seaport [Museum] at the Conrad camp. My family was visiting the Museum from Huntington, Long Island, and heard about the camp from an announcement made on Sabino and decided to enroll me. It really put me on a path that changed the direction of my life.

Years later, my family was going through some hard times financially due to unexpected and protracted job loss. We looked into the Brilliant scholarship opportunity for families experiencing financial hardship and for the first time ever, we applied for financial assistance. We received a financial grant that allowed me to have this experience at a time when I would not have been able to otherwise. I am writing this letter to report on the aftermath of that gift.

My time as a Brilliant sailor changed my life in many ways. Overall, it deepened my ties to the sailing community and solidified that sailing would be a part of my life. I am currently a student

THE MUSEUM’S FAR-REACHING IMPACT

at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida, and a member of Eckerd College Search and Rescue (ECSAR), a college maritime rescue program. I am employed as a sailing instructor at the college’s Waterfront Center. I work summers at Florida Seabase camp in Islamorada Key teaching sailing. My experience as a Brilliant sailor directly led to all of these endeavors.

If the Conrad camp was the first step on this path, the Brilliant experience led me further down it. And without the generosity and financial support I received at a pivotal time in my life, I don’t see how I could have accomplished any of these things. Thank you for providing support at a time when it was truly needed. I am truly grateful.

Tim Kusterbeck, CONRAD and BRILLIANT summer camper

THE SUMMER of the Morgan

We’re excited to announce the “Summer of the Morgan” in celebration of the Charles W. Morgan’s 184th birthday. Preparations began in March with the downrigging of the Morgan to reduce its weight aloft and windage before being hauled ashore at the Museum’s Henry B. du Pont Preservation Shipyard for a classic “shave and a haircut,” which included a thorough cleaning, fresh paint, and zinc replacement. After the refresh, the Morgan was returned to Chubb’s Wharf and re-rigged.

The Summer of the Morgan officially kicks off Memorial Day weekend with the opening of Monstrous: Whaling and Its Colossal Impact, an exhibition exploring the history of American whaling and its profound impact on our region and nation. Visitors can enjoy a variety of new programs and activities both on board the Morgan and throughout the Seaport Village all summer. Explore a new walking tour of our campus focusing on the impact of the whaling industry from 19th-century through to today.

The walking tour includes the rare opportunity to visit the ship’s hold, normally off-limits to the public. Everyday visitors will enjoy newly imagined onboard activities and storytelling by our skilled interpreters and volunteers. Watch a Morgan-inspired film in the Meeting House, participate in a family scavenger hunt and activities with a souvenir handout, and capture the memories with a selfie photo op with the Morgan as backdrop. Celebrate the Morgan’s 184th birthday on July 19–20 with live music, expert talks, special shows in the Treworgy Planetarium, and cake! Don’t miss the Museum’s annual 24-hour reading of Moby-Dick on board the Morgan and more throughout the summer.

This marks the beginning of a multi-year plan to ensure the Morgan shines for the Museum’s centennial. We look forward to welcoming you aboard!

AIMing Ahead: The American Institute for Maritime Studies

Last fall, the Museum announced the launch of the American Institute for Maritime Studies® (AIMS), an initiative consolidating the Museum’s scholarship in maritime studies and coupling it tightly to other core museum activities including collections care and access, curatorial work, exhibitions, intellectual property, and publications. The goal of AIMS is to elevate the position of Mystic Seaport Museum as the home of the nation’s leading maritime research facility and academic institute.

AIMS strengthens the Museum’s graduate and undergraduate programs and services through fellowships, internships, visiting scholar programs, conferences, and

guest speakers, under the aegis of the newly created Department of Research and Scholarship. This department will build partnerships with institutions of higher education, including a new relationship with the Ruth J. Simmons Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice at Brown University, as well as nurture and strengthen long-term close partnerships such as those with Williams College and the University of Connecticut.

The Museum’s scholarly initiatives continue to advance “productive scholarship” by inviting outside experts to enhance exhibitions, collections research, and publications. With two issues of Mainsheet, the Museum’s multidisciplinary journal of maritime studies, now distributed (Issue 1 on social maritime histories, Issue 2 on ocean technology and economies), editorial work for the third issue on maritime archaeology challenges is underway. Each issue features peerreviewed, academic articles, while also supporting emerging scholars by waiving submission and publication fees. Shorter pieces like photo essays, book reviews, and poetry complement the longer articles. An external editorial board includes maritime curators, scholars, and staff from museums and universities worldwide, and

ensures the journal’s high standards.

AIMS represents a significant step forward in the Museum’s path to enhancing current scholarship around maritime histories and to telling stories that have been passed from generation to generation, recognizing that skills, knowledge, and customs around our maritime heritage have often been passed down through oral tradition and hands-on training and experience.

In addition to being the nation’s premier location for maritime scholarship, with the formation of AIMS, the Museum is committed to making collections (including objects, artwork, manuscript and library materials, rare books, oral histories, charts and maps, ships plans, and photographs) more accessible for researchers and for the general public. This involves the vital behind-the-scenes work of dozens of staff who dedicate their days to employing best practices in museum stewardship while cataloguing, inventorying, photographing, researching, digitizing, and housing Museum collections.

By integrating the G. W. Blunt White Library, the Museum’s scholarly programs, and the Collections Research Center, the AIMS staff, volunteers, and interns explore topics related to maritime cultural connections,

art, historical, and current issues through a contemporary lens. This will broaden their research through robust connections with national and international universities and museums, including the Smithsonian Institution through the Museum’s status as a Smithsonian Affiliate.

AIMS endeavors centered on research and scholarship partnerships are already bearing fruit. In January the Museum hosted one of three national convenings organized by the Minnesota Marine Art Museum. “A Nation Takes Place” brought together artists, writers, curators, scholars, community organizers, and art professionals to further discussion, knowledge sharing, and cultivating networks to address new and emerging scholarship, curatorial practices, and artistic expression that centers Indigenous and Black voices within the marine art and maritime genre. Later this spring, the Minnesota Marine Art Museum will host the Oceanus exhibition featuring artwork by Alexis Rockman, owned and traveled by Mystic Seaport Museum.

In April, AIMS co-sponsored the three-day convening “Seeqan Sessions: Light, Growth, and Preservation” with the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center and Brown University’s Ruth J. Simmons Center

for the Study of Slavery & Justice. Focused on water, watersheds, and oceans, the event brought together scholars, artists, youth, and advocates to explore waterways, culture, and resilience. AIMS staff from exhibitions, curatorial, and research and scholarship are meanwhile working with colleagues across the institution on planning for Museum programs and activities to mark the upcoming 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Staff are also leading research efforts by Williams-Mystic students and winter workers from other departments that could contribute to an institutional history Centennial for Mystic Seaport Museum itself in 2029-2030, including biographical research into Marion Dickerman, long-time Director of Education at Mystic Seaport Museum from 1945 to 1962, and one of the three “Graces of Val-Kill,” along with her life partner Nan Cook and Eleanor Roosevelt. AIMS’ new management staff appointments reflect the Museum’s commitment to experienced leadership. Leah Prescott, MLS, returns as Senior Library Administrator after 18 years at the Getty Research Institute, Georgetown University Law Library, and Harvard Law Library. Dr. Debra Schmidt Bach, formerly of The New-York Historical,

becomes Director of Exhibitions, bringing fresh and dynamic ideas. Michael P. Dyer, MA, renowned in the maritime museum world for his accomplishments at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, joins as Curator of Maritime History and Instructor in the Frank C. Munson Institute. Krystal Rose continues as Director of Collections, while Mary Anne Stets oversees intellectual property, business development, and publications. Additionally, I have transitioned from the Exhibitions department to lead the new Department of Research and Scholarship. Through these collective efforts and coordinated work, we are all playing our part in advancing AIMS’ prominence in maritime studies, maritime museums, and beyond. We AIM high to advance forward, building on the legacy of those who came before us and who laid a strong foundation of collections, research, scholarship, and stewardship for us to continue into the next generation.

Elysa Engelman, PhD, Director of Research and Scholarship, American Institute for Maritime Studies

Starboard view of Charles W. Morgan at Mystic Seaport Museum, 1950, taken by William Avery Baker (1986.16.1882).

Monstrous: Whaling and Its Colossal Impact

Open from May 24, 2025, to February 16, 2026, Monstrous: Whaling and Its Colossal Impact will illuminate the history of American whaling and its impact on our region and nation. The gallery will pair a monumental mural, aptly titled Or, The Whale, created by artist John Joseph “Jos” Sances, with assemblages of the enormous tools used during American whaling voyages. Viewed together, the mural and artifacts provide material insight into the colossal efforts undertaken during commercial whaling voyages to extract the highly prized blubber and spermaceti that became so vital to Americans during the nineteenth century. Monstrous capitalizes on the Museum’s extensive whaling holdings and will consist almost entirely of artifacts, documents, and photographs from the Museum’s Curatorial and Library Collections.

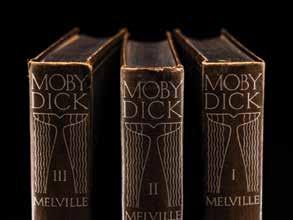

Jos Sances is a printmaker, muralist, and activist based in the San Francisco Bay area. In Or, The Whale, he meditates on the ways in which American economic and technological innovations of the past three centuries have impacted human and natural resources. Like many writers and artists, Sances was influenced by Moby-Dick and the original illustrations created by Rockwell Kent for his 3-volume

edition of the novel published in 1930. Or, The Whale is composed of 119 scratchboards fabricated from eucalyptus covered with kaolin (a fine clay) and black ink. Together, the panels morph into a life-size silhouette of a sperm whale surrounding scenes drawn from the history of American capitalism. Sances divides these scenes into thematic neighborhoods that probe such topics as the Pequot Massacre of 1637 and the exploitation of Native Americans; Transatlantic Slave Trade and systemic racism; women’s suffrage; civil rights, attitudes toward immigrants and refugees; issues around wealth disparity, and the real and human costs of mining, oil drilling, and deforestation. Or, The Whale will be accompanied by a video of the artist describing the work and ThingLink technology which provides visitors with digital access to additional content. Sances will be on hand at the Museum for the exhibition opening.

The Museum holds hundreds of artifacts and documents that attest to the unprecedented demand for whale oil in the United States from the 1820s to 1920s. The sheer size of the Museum’s most gigantic whaling tools calls to mind the enormous costs expended in the pursuit of whales and their precious blubber. Rotund iron trypots,

Jos Sances (b. 1952), artist, detail from Scratchboard mural, Or, The Whale, 2018-20

elongated harpoons and darting guns, piercing cutting-in tools, and massive blubber hooks will be displayed alongside models of whaling ships, logbooks, examples of commercial whale oil, historical photographs, and other whaling memorabilia. Monstrous will contextualize the ways in which these tools were utilized with vivid illustrations of whalers in action. Capitalizing on the extent of the Museum’s collections, Monstrous will feature paintings and lithographs that bear witness to the life-threatening dangers whalers faced while pursuing these formidable mammals.

Monstrous gives Mystic Seaport Museum the opportunity to share a selection of revelatory historic photographs that precisely document whale hunting and blubber processing. Remarkably, unmoored whaling ships doubled as floating oil processing factories. Scenes of “cutting-in” and “trying out” are two of many processes chronicled in the Robert Cushman Murphy and H.S. Hutchinson & Co. Collections. Viewing images of these labors alongside the actual tools depicted in the photographs emphasizes the staggering risks whalemen took to quench the American hunger for whale oil. Tryworks furnaces operating on the decks of whalers boiled blubber in twohundred-gallon iron cauldrons. Monstrous will feature two trypots as well as the tryworks tools (including a ladle and strainer) that are discernable in these descriptive photographs.

the numbers of barrels of oil taken from each conquest.

Monstrous will show an array of consumer products, including those made from whale oil, teeth, jaw bones, or baleen. These artifacts include ephemera from a New Bedford emporium that sold whale lubricant for sewing machines; a small flask of ambergris (1985.75.2), the waxy substance from whale intestines prized for its use in perfumes; baleen dress stays; and early sperm oil lamps. Sailors on long whaling voyages carved and engraved scrimshaw from whale teeth and pan bones. Intricate scenes incised into or sculpted from whale teeth became trophies, homecoming gifts for loved ones, and sailors’ tools. Along with raw and decorated whale teeth, Monstrous will exhibit multiple examples from the Museum’s incomparable scrimshaw collection—folding swifts, knitting needles, boxes, corset busks, and even a rare lathe and frame saw.

Such a portentous and mysterious monster roused all my curiosity.

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick (chapter 1), 1851

Whale oil is non-drying and non-corroding. National demand for the substance was unprecedented by the midnineteenth century, when Americans clamored for the lubricant for fine instruments like navigational equipment and sewing machines, and as an illuminant for lamp fuel. The cultural and economic significance of whale oil is suggested in two unparalleled artifacts to be featured in the exhibition. A box of sperm whale oil samples taken by Capt. Fred H. Smith and his wife Sallie between 1875 and 1878 while on the bark Ohio includes 26 vials of oil taken from whales caught during the three-year voyage. Interestingly, Smith and his wife kept an accounting of the samples still visible today on the underside of the box lid. Equally edifying is a new acquisition—a journal from a sperm whaling voyage penned between 1860 and 1864 on the New Bedford bark Stella Included in its pages are financial accounts, songs and poems, descriptions of shipboard discipline, samples of whale skin, and an inventory of whales caught during the four year journey. One page shows 31 tiny whales inked by whale stamps with cut-outs that record

Monstrous will conclude by recounting some of the lesser-known stories of the many different men and women who embarked on whaling voyages. Whaling crews were multicultural and included an international roster of (primarily) men from many backgrounds. The Museum’s historic whaling photographs attest to the diversity of whaling crews, as does a stately portrait of Antoine DeSant (1815-1886), an accomplished Cape Verdean whaler who settled in New London in 1860. Women, too, participated in whaling voyages, as wives and mothers, but also as navigators, correspondents, nurses, managers, and log keepers. These women include (Charlotte) Lottie Church (Capt. Chas. S. Church), the last woman to sail on the Charles W. Morgan during its active whaling career. Lottie Church embarked on her first whaling voyage in 1909, when she signed on as an “assistant navigator.” An active shipmate, she also kept the ship’s log and assisted her husband in managing the crew. Whaling and Its Colossal Impact will open in the Collins Gallery on May 24, 2025.

Debra Schmidt Bach, PhD, Director of Exhibitions

a. Trypot, ca. 1890, (1970.51); b. Blue whale fetus, 20th century, (1939.1198); c. Jos Sances (b. 1952), artist, Detail, Or, The Whale, 2018-20; d. Unidentified artist, Engraved sperm whale tooth with scene, Battle of Lake Champlain— Macdonough’s Victory, ca. 1850, (1941.412); e. Cornea from blue whale eye, 1937, (1945.292); f. Whale stamp, mid-19th century, (1939.1904); g. Robert L. Evans (active 1986-99), Cutaway model of Whaling Bark Charles W. Morgan, 1987, (1999.122.1ab); h. Herman Melville (18191891), author; Rockwell Kent (1882-1971) designer and illustrator, Moby-Dick: Or, The Whale, 3 vols. (Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1930), G. W. Blunt White Library

OUR COLLECTIONS: A Maritime Treasure Trove

Mystic Seaport Museum is home to one of the most comprehensive collections of maritime artifacts, archives, and resources in the world. In the first decade of the Museum (1929–1939), then known as the Marine Historical Association, the founders and staff welcomed a broad array of materials into the collection. These early items, which included books, chests, relics, models, prints, photographs, scrimshaw, and of course our first vessel, the sandbagger, Annie, all shared one thing in common—a connection with the sea. Now, with over two million objects, the Museum’s collections are a treasure trove for understanding the rich history of life on and around the sea.

Home to the Museum’s collections of art, objects, small watercraft, and archival resources, the American Institute for Maritime Studies (AIMS) unites the G. W. Blunt White Library, Exhibits Department, Curatorial operations, Department of Research and Scholarship, and Intellectual Property operations. Accessible to maritime researchers, students, staff, and visitors, AIMS holds more than two million examples of maritime art, scrimshaw, ship models and half-models, textiles, tools, photographs, and 1.5 million feet of historic and contemporary maritime-related film and video footage. The Library, part of these broader collections, houses books and periodicals, manuscript collections, ship plans, oral history interviews, and historical and contemporary charts and maps.

The Department of Research and Scholarship (DRS), created in 2024, plays a critical role in leveraging the Museum’s scholarly resources to advance maritime scholarship. The combined collections and research efforts preserve the voices, experiences, and innovations of those who have shaped our maritime heritage, offering a valuable resource for scholars, educators, and the public alike.

Drawing from the full range of AIMS resources—including collections, curatorial expertise, research, and archival materials—the Exhibits Department crafts compelling narratives into engaging and informative exhibitions. The result is a captivating and educational journey through maritime history, fostering a deeper connection to the stories of the sea.

At Mystic Seaport Museum, we believe that the sea connects us all, and every document, artifact, book, and object in our collection has something to teach or a story to tell. The following pages highlight just a few objects from the Museum’s collections and the work that is done behind the scenes to care for them. We invite you to visit the Museum and discover your connection to the sea— your sea story.

Leah Prescott, Senior Library Administrator

The G. W. Blunt White Library is more than just a repository of knowledge; it is a gateway to discovery. Each year, researchers, enthusiasts, and families from around the globe visit the Library in search of answers, inspiration, and connections. With dozens of requests each week, our goal is to provide seamless and tailored access to our extensive and diverse collections by assessing each inquiry, identifying materials, and ensuring visitors can navigate all aspects of our collections, empowering visitors to embark on their own meaningful research journey.

The Museum welcomes a diverse audience, including maritime enthusiasts; scholars and academics; law students investigating maritime law and topics such as workplace conditions aboard ships; boat owners and model makers seeking inspiration and technical details for their historic and modern projects; genealogists uncovering family histories tied to maritime endeavors; students at all levels from middle school to PhD candidates; local people who take advantage of their proximity to this wealth of history; and staff from all departments who utilize our collections to support their work. From technical studies of vessel design and global maritime trade over centuries to the social, cultural, and historical aspects of life at sea and the environmental studies of weather patterns and climate through historical logbook data, each research topic provides a glimpse into the diverse ways our collections are utilized. Library staff guide researchers to explore our extensive holdings, including books and rare books, logbooks, diaries, personal accounts, blueprints, schematics, photographs, paintings, ship models, artifacts, and periodical publications that chronicle maritime history and developments over centuries.

Perhaps the most rewarding moments are those when visitors discover a direct connection to the past. Recently, we had the privilege of hosting a family descended from Silas Talbot, a figure with an impressive Naval career, including his command of the USS Constitution. This collection is rich with documents that illuminate key issues such as impressment, privateering, and the American Revolution. Connecting families with significant pieces of history and acknowledging the role their ancestors played on the front lines is truly special.

A nine-year-old boy from Australia—passionate about sailboats, sailing, model making, and maritime literature—inquired about ship plans, eager to build his own boat. He discovered that Atkins’ plans provided an excellent starting point. After selecting a design he loved, he reached out to us for further information. It was truly rewarding to witness his enthusiasm and dedication to his craft. These visits are often memorable and, at times, even emotional for both visitors and Museum staff. It is our honor and privilege to help facilitate these powerful reunions and passions, offering a tangible link to the past.

“A nine-year-old boy from Australia . . . inquired about ship plans, eager to build his own boat.”

Over the last year, our team has helped visitors access materials that link them to cherished artifacts: a ship model crafted by an ancestor, a logbook documenting a relative’s voyages, and photographs capturing moments of personal history. These discoveries not only deepen our visitors’ understanding but also highlight the enduring relevance of maritime heritage through valuable information and connections as they find their own sea story. Visitors from across the world can stay engaged with our collections at research.mysticseaport.org and discover their personal connection to the sea.

Staff of the G. W. Blunt White Library

Cataloging History

Maintaining a large collection at Mystic Seaport Museum relies heavily on thorough documentation. After an object is accessioned into the collection by the registrar, the next step is cataloging. Cataloging involves recording detailed information about each object in the museum’s collection. These records bring together everything we know about an item, making it easily accessible for both museum staff and the public through our online collections database. The goal is to create a comprehensive profile that not only captures the essence of each object but also highlights its significance.

To achieve this, a cataloger first explores the object’s provenance, or history of ownership. Provenance can instantly change the significance of an object. For example, we have a sextant in our collection made by E. & G. Blunt (2006.50.1). While we have many navigational instruments by this maker, the context of this particular sextant is elevated when we learn it once belonged to Captain James A. Hamilton, the captain of the Charles W. Morgan during its sixth and most profitable voyage. This object’s value isn’t just about its function as a navigational instrument but also the rich stories it connects to—its use on the Morgan, its link to the captain and crew, and even our library, which honors a Blunt family member. This sextant is currently on display in the Treworgy Planetarium. Not every object comes with such clear provenance, so research plays a key role in cataloging. When an object arrives, we begin a search for any details that might shed light on its history—such as names, dates, locations, inscriptions, and maker's marks—often starting with a simple Google search. As we gather more information, we refine our search. With the wealth of online resources available today, we can dig deep into an object’s history. Often, the research for one object uncovers connections to others, linking together different pieces of maritime history.

Some objects, however, pose more challenges. Maker’s marks on older objects may be worn away, names might be misspelled or hard to read, or an item may be so niche that little information is available. In these cases, consulting with colleagues is invaluable. The collective knowledge of our staff often leads to intriguing conversations about shipbuilding, maritime trade, marine biology, engineering, and life at sea. It’s all about putting the right minds together to learn more about the objects in our care, and our staff is always eager to share their insights.

Catalog records are used in many ways across the Museum. They help inspire new exhibits, spark ideas for educational programs, and play a critical role in caring for and preserving our collection—and the stories each object holds—for future generations. Our online database makes these records available to the public worldwide, supporting research efforts and advancing our mission to be a steward of maritime history. The Art and Objects collection at Mystic Seaport Museum reflects the diverse story of the American maritime experience, and maintaining a detailed catalog is an essential part of our work.

Jenny Carroll, Collections Cataloger

A Sea Chest, a Lamp, and Hope for the Future

More than two hundred years ago, Irish immigration to the United States was beginning to increase. British rule in the nation worsened economic disparities and increased levels of poverty, pushing struggling Irish men, women, and families overseas in hopes of a better life. The most severely impoverished Irish citizens and families would not have been capable of raising the funds needed for this migration, a taxing journey, with a seafaring portion that could last approximately 30–70 days. These early migratory vessels were less than luxurious, and aside from conditions aboard, Irish migrants were at further risk—British war vessels present in the region posed the threat of impressment (forced enlistment into military service).

Early in the 19th century, a young James McKiernan of County Cavan took up work as a sailor. Those who worked aboard vessels spent expansive stretches of time at sea, far away from the comforts of their home and family. The possessions needed for survival, work, and passing the time between tasks, would be packed away in a sea chest. The chest belonging to James McKiernan is a stunning example of what Irish sailors used during this era. Constructed using a historic technique, one large piece of pine was carved into to create a rectangular-shaped opening for the chest.

Upon raising enough funds to cover the migration James McKiernan began his journey overseas—this time, as an emigrant, instead of an employed sailor. For this voyage, he again packed up his pine sea chest, potentially housing items such as his alcohol lamp for cooking. Irish citizens immigrating to America carried with them few worldly possessions, often bare necessities and some items of sentimental value. But this is

not to say that the Irish arrived on American shores empty handed—Irish tradition and culture, a spirit of freedom, and an essence of fervent dedication was carried overseas in abundance.

McKiernan immigrated to America well before the establishment of the Ellis Island immigration center, and even prior to Ellis Island’s precursor, Castle Garden. Additionally, according to Ireland’s National Archive, the Irish emigration papers for the McKiernan couple—and a large share of other important Irish papers and documents from 1787 to 1823—were likely held by the Customs House in Dublin. In 1921, the Customs House was targeted by the Irish Republican Army and was subsequently burned. Each document perished. Despite the lack of entrance papers for McKiernan, historical document repositories contain information showing that, upon his arrival, he and his wife Susan decided to make Connecticut their new home in the Yalesville area of Wallingford. Not long after James and Susan, their son Bernard McKiernan began his voyage to America, joining them in Yalesville. The McKiernans joined a bustling Irish community in New Haven. There, Bernard was involved with the John Mitchel[l] Literature and Debating Society.

Mitchel[l] was an advocate for Irish freedom and editor for the Irish Citizen newspaper. Historians note that, in later years, a debating society of this name was a covert sect of the Na Fianna Eireann—an Irish nationalist group advocating for Irish freedom from British rule.

Perhaps, the foundation for this transition was laid by Mitchel[l] and his fiery speeches, and the nearby Fenian Brotherhood (New Haven), a nineteenth-century Connecticut-born branch of the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

When paper records are scarce or absent, the presence of material items—such as McKiernan’s sea chest—become ever the more significant in uncovering stories of migration, perseverance, and connection. The sea chest is part of the Museum’s permanent collections.

Makenzie N. Metivier, Collections Assistant

ABOVE: The McKiernan family’s alcohol cooking lamp, also referred to as an alcohol stove. Though alcohol cooking lamps had gained popularity long before, this particular model would have been used by the McKiernan’s in the early 20th century, living and working in Connecticut (1959.1078).

LEFT: A pine sea chest belonging to James McKiernan, an Irish sailor who immigrated to the United States early in the 19th century. The chest is made in a “dug-out” style, with all but the lid being carved from a single, large, piece of wood, rather than by joining panels of wood to form the chest (1959.1074).

As I wandered through the vault of the Museum’s Collections Research Center, my eyes were drawn to a striking painting of a schooner-yacht, its sails billowing as it raced across the horizon. The image seemed alive, as though the very wind filling its sails was spilling out beyond the frame, whispering a forgotten story waiting to be told. Wanderer is no mere ship—it is a vessel of innovation, prestige, beauty, betrayal, and war, carrying a legacy that claims all who are drawn to its dark past. Nearby, a finely crafted chair caught my attention—its intricate carvings and luxurious materials silent yet evocative—the very seat Captain Thomas B. Hawkins likely occupied aboard Wanderer. Captain Hawkins’ jacket—perhaps the one he wore as master—hangs nearby. One can almost imagine Captain Hawkins in his blue wool tailcoat, New York Yacht Club gold buttons gleaming, seated on deck, gazing at the sea.

Launched on June 19, 1857, from W. J. Rowland’s shipyard in Port Jefferson, New York, Wanderer quickly gained fame for its luxury and craftsmanship. Under Captain Hawkins—a respected mariner and boat designer born and based in Setauket, Long Island—the schooner yacht became renowned for its sleek design and exquisite details. Commissioned and owned by Colonel John D. Johnson, the vessel was celebrated as a marvel of shipbuilding—built for both

speed and elegance.

The gleaming deck and lavish interiors symbolized Johnson’s wealth and taste, including a $1,400 upholstered chair, a stunning display of opulence. As a “luxury racing yacht,” Wanderer became a status symbol at the New York Yacht Club. But the vessel’s journey soon took a darker turn.

When Colonel Johnson sold the yacht to William Corrie, a smooth-talking Southern gentleman and a recent New York Yacht Club member, Wanderer was unexpectedly repurposed for an illegal mission: the slave trade. Behind Corrie was Charles A. L. Lamar, a radical Southern secessionist who secretly purchased the yacht and orchestrated the operation. Lamar sought to bypass the 1808 US ban on the international slave trade, using Corrie as a front to carry out his plan.

In 1858, Wanderer set sail under the flag of the New York Yacht Club, cloaking its dark mission in respectability. Its goal was to sail to Africa, procure enslaved people, and bring them to the South. On November 28, 1858, the yacht successfully landed approximately 407 enslaved Africans on Jekyll Island, Georgia. This illegal voyage marked one of the last known slave shipments to the US, provoking national outrage and reigniting abolitionist movements.

Wanderer’s involvement in the slave trade exposed the deepening divide between North and South. In the North, where

The Mystery of Wanderer: A Vessel of Beauty, Deception, and Dark Legacy

slavery had been abolished, the yacht’s mission was seen as a moral affront. In the South, it became an act of defiance against federal law—symbolizing resistance to abolition. The yacht became a focal point in the national debate over slavery and the looming Civil War.

Today, Wanderer is largely forgotten, viewed as a curiosity rather than an object of admiration. Yet its story remains a powerful reminder of the complex ways in which wealth, ambition, and power have shaped American history. What began as a masterpiece of shipbuilding and a symbol of elite status became, through a series of fateful decisions, an emblem of one of the nation’s darkest chapters. Mystic Seaport Museum preserves significant artifacts and archival materials from the life of Captain Hawkins. The painting of Wanderer is a part of the Museum’s permanent collections. For more information, visit the Long Island Collection page on the Mystic Seaport Museum Collection Research Center website. The Long Island Collection is generously supported by the Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation, which funds the study of Long Island’s history and its role in the broader American experience. For further details, visit www.rdlgfoundation.org.

Kate Katin, Curator of the Long Island Collection

Oil painting of Wanderer (right) under sail with New York Yacht Club burgee flying. Artists Joseph B. Smith and son William, c.1857, (1997.129.1A).

Whaling Journal Sparks Scrimshaw Question

Last September, the Museum acquired a whaling journal from Eldred’s Auction in East Dennis, Massachusetts. The journal itself is unremarkable, being an abstract of a sperm whaling voyage to the Indian Ocean on the bark Stella of New Bedford with Frederick Hussey as master, 1860-1864. Abraham T. Sanford (1818-1895), cooper, kept the journal. Where it gets interesting, is that Sanford was a collector of songs.

Most of the volume, along with several loose manuscript sheets, is made up of song lyrics. Included is one which Sanford himself claims to have penned called “The Nantucket Whaler.” It includes a stanza suggesting that once ashore right whalemen (Brazil boys) must take a back seat to sperm whalers (Cape Horners) in the eyes of Nantucket lasses:

Who stand all in the entry with their whale bone sticks so neat

For to let Cape Horners pass with their jaw bone canes complete

And through these halls go dancing and through halls so fine

You Brazil boys may follow but leave your sticks behind.

The truly outstanding part of the Sanford journal are two pieces of whale skin tucked into the pages. One of the pieces is roughly square, the other has been cut out in the exact shape of the spermaceti whale engraving first published in James Colnett’s book, A Voyage to the South Atlantic and Round Cape Horn into the Pacific Ocean (London: W. Bennett, 1798). In all likelihood the whale skin profile was traced directly from the illustration in the volume. At 8 inches long and 2 inches across the flukes it is nearly exact. On this voyage the Stella cruised on the Coast of Chile, the Coast of Peru, and the Galapagos Grounds. As Colnett’s voyage famously cruised these very grounds, the likelihood is high that the master had a copy of Colnett onboard for reference and that Sanford copied his whale from it.

The big question is whether or not this whale skin cut-out constitutes “scrimshaw”? As it is a piece of art made by a whaleman from materials obtained on a whaling voyage, it certainly fits that part of the definition. It being entirely unique with no comparable antecedents, Sanford’s whale skin profile could thus serve to broaden the definition of the art form as it is commonly understood.

Very few scrimshaw whalebone (baleen) “sticks,” or canes are to be found in museum collections. Compared to the stiff and sturdy skeletal bone from the jaw of a sperm whale, whalebone was too flexible to make a good cane. Plus, whalebone had great market value, too much to be so frivolously employed, so what exactly Sanford means in his song lyrics is unclear. “Whalebone” was the market (and general vernacular) word for baleen and his use of it in direct relationship to Brazil Banks whalers is definite. From his viewpoint, the important part of the story is that right whalers were not admired on Nantucket. Unlike New Bedford or New London, both important right whaling ports, Nantucket whalers made their fortunes primarily from sperm whaling. The Brazil Banks were a very productive right whaling ground and while that may have been OK to a New London girl seeking a suitor, the Nantucket girls, according to sailor’s lore, seem more particular.

Michael Dyer, Curator of Maritime History

ABOVE: Journal kept onboard the bark Stella of New Bedford, Frederick Hussey, master, Abraham T. Sanford, cooper, keeper, May 31, 1860-April 5, 1864. Log 2000.

RIGHT: Whale skin sperm whale profile (2025.7).

A FIGUREHEAD: Uncovering the History of Iolanda

When visitors first enter the Figureheads and Shipcarvings exhibition in the Wendell Building, many gasp at the sight of the large white figure looming into view from the corner of the room. Mounted on a reconstruction of a ship’s prow, this female figurehead once graced the same position on the steamship Iolanda. When the 310-foot-long ship was built in 1908, the vessel was the world’s second largest private yacht. Although the figurehead is seven feet tall, it was dwarfed by the massive yacht. A blend of tradition and modernity, the Iolanda looked old-fashioned with its schooner rig and clipper bow but was powered by a coal-fueled steam engine that could propel it at a speed of twelve knots, burning around 30 tons of coal per day. Broken up in 1958, the Iolanda is survived by photographs, ship models, interesting stories, and not one, but two figureheads. Unlike most figureheads from previous centuries whose origins are shrouded in mystery, extensive documentation exists for this twentieth-century carving.

Figureheads were already a thing of maritime past when the steam yacht Iolanda was built in 1908. When the Iolanda’s original owner, Morton F. Plant, chose to have a figurehead made for the vessel, he was no doubt inspired by romantic notions of a glorious, seagoing past. The Iolanda’s neo-classical figurehead depicts a stately woman in a flowing, neo-classical dress. Her left arm is bent close to her chest in a gesture of determination, while her right arm hangs at her side. Her position recalls those of traditional figureheads mounted on hulking Spanish galleons, majestic British naval ships, and speedy American clippers, no doubt appealing associations for a wealthy and powerful American railroad, steamship, and hotel magnate like Plant. She looks as though she is charging forward, guiding the ship Iolanda into its next adventure.

During preparation for the installation of Iolanda and the other figureheads in Figureheads and Shipcarvings in 2020, additional information was uncovered about the artifact, the ship from which it came, and its journey to the Museum. The figurehead in the Museum’s collection is actually a replacement, carved and installed after the original figurehead sustained significant damage in a Pacific storm. A Mr. Meadows of Shirley, England, fashioned the replacement figure in the early 1930s, creating a copy nearly identical to the original, with slight changes, including to its face and the tilt of its head. The original figure is also more slender, and there are some subtle differences in the carving of the folds of the garments.

While the replacement figurehead (right) made its way to Mystic Seaport Museum in 1959, and has been here ever since, during that same period the original figurehead mysteriously surfaced in a California antiques shop. From there, it journeyed to Seattle, Washington, where it spent many years hanging above the entrance to Trader Vic’s tiki-themed bar and restaurant. It now resides at the Museum of History and Industry in Seattle.

Visitors to the Figureheads and Shipcarvings exhibition can learn more about the Iolanda—including the origins of the vessel’s name after Princess Iolanda—and see the figurehead in direct relationship to a detailed ship model of the yacht, showing its relative size in-scale with the original vessel. Mirelle Luecke, co-curator of “Figureheads and Shipcarvings ”

Figurehead from the steamship Iolanda, currently in the Figureheads and Shipcarvings exhibition (1959.212).

Wail on Whalers: With Artist Felandus Thames

Wail on Whalers (portrait of Amos Haskins), a recently acquired piece now in the Museum’s permanent collection, is a work of art that demands a closer look. Hanging in the Museum’s exhibition Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea at nearly eight feet tall, it is a monumental work of portraiture at first glance. Viewed more closely, the viewer’s gaze shifts as the thousands of small beads intricately strung to create the work come into clearer sight. The colorful complexity of its composition makes the work a dynamic tribute to its central figure—Amos Haskins (1816–1861), an Aquinnah Wampanoag master mariner and whaling captain—and to all the Black and Indigenous mariners who found freedom at sea.

Wail on Whalers is a new piece by New Haven artist Felandus Thames, commissioned for Entwined before the exhibition’s opening in 2024. As he sought inspiration for the piece, Thames searched for stories of Black and Indigenous mariners that were grounded in autonomy, prosperity, and power. Haskins’ story of resilience in the face of adversity on land and at sea stood out to Thames. Haskins first went to sea as a teenager and signed aboard his first whaleship as second mate on the brig Chase in 1841. Within ten years, he took command as captain of the bark Massasoit, becoming one of very few Indigenous men to achieve the rank of whaling master in the 19th-century American whale fishery. Thames explained,

During my research, I came across narratives detailing a conspiracy aimed at sabotaging his progress. . . . One such account involved Amos embarking with an all-white crew who deliberately deserted him after the initial port, seeking to derail his efforts. Undeterred by this setback, Amos took matters into his own hands, recruiting a predominantly black crew from the town to successfully complete his mission.

Wail on Whalers (2024.95)

In addition to capturing Haskins’ story, the motifs and medium of Wail on Whalers pay homage to Thames’ Black and Indigenous heritage. Haskins’ portrait is set against a brilliant backdrop of colorful designs that evoke patterns found in Victorian, Dutch, American Indigenous, and African fabric arts. Thames drew inspiration from the tradition of quilting, which has been part of his family for generations. “The matriarchs of my maternal lineage were quilters and echoes [of] that cadence permeated their interiors. Their homes were an embodiment of that aesthetic philosophy, fragments of the past entwined with the new,” Thames explains.

The thousands of beads used to render Wail on Whalers also speak directly to both Thames’ practice and to the themes of power and sovereignty. Thames spoke to his choice of material, saying,

Since beads were commonly used as a form of currency among Africans and Indigenous cultures, ultimately, I am arguing that these figures and their stories all have currency. As a philosophy, I am bound to the notion that a key role of the “Artist” is to point or bear witness to things in the world with value. It’s up to the viewer to impugn meaning.

You can visit Wail on Whalers in Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea, on view in the Stillman Building until early 2026. After that, it will find a home in the Museum’s collections vault and be available to future curators and scholars for study and display.

Entwined: Freedom, Sovereignty, and the Sea is generously funded by the Just Futures Initiative of the Mellon Foundation as part of the Reimagining New England Histories project. Mystic Seaport Museum also gratefully acknowledges our project partners, Brown University and Williams College, and our community advisors whose collective voices, knowledge, creativity, and wisdom are foregrounded in this exhibition. We also thank Felandus Thames for contributing to this article.

Bridget DeLaney-Hall, Associate Curator of Maritime Social History

SILVER CREATURES from the Sea

Among the silver objects in the collections is this little inkwell, which exemplifies the unique artistry of German American artisan Carl Schon. This unique object, now on display in the exhibition Sea as Muse, is crafted from the shells of a sea urchin, a scallop, and a periwinkle, all covered in silver plate and assembled to form a desktop object that is both decorative and useful. It is just one example of a much larger body of work that made Carl Schon a noted craftsman in his day.

Trained as a jeweler, Schon found inspiration for his decorative arts career at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, when he was twenty-nine years old. He was captivated by a display of works by the Paris silver manufacturing company, Christofle. Many of these objects were adorned with decorations modeled on natural forms: meandering branches and leaves, complex flowers, beautiful young women in sinuous poses. The work exemplified the highest degree of artistic design and skill and reflected a wide popular interest in nature as an inspiration for graphic and interior design, furniture, and decorative arts. Schon was both enchanted and inspired to celebrate the beauty of nature in work of his own. Although he did not possess the artistic or technical training of the Parisian silversmiths, Schon did have passion, knowledge of metallurgy, and ingenuity. After settling in Baltimore around the turn of the twentieth century, he began experimenting with applying silver plating to vegetables and plants, including ears of corn and bamboo roots.

Schon finally found lasting success in the plating of deceased sea creatures, which he purchased from around the world. His work received acclaim for its innovative technique and the novelty of the objects he produced. While traditional silver artisans replicated natural forms or transformed them into stylized designs, Schon created a new approach, using a layer of precious silver to preserve nature’s creations as they were found and then assembling them into useful objects. Just as every sea creature was unique, so every item that he created was also one of a kind.

Visitors to Schon’s shop in Baltimore could find silvery sea creatures of all kinds adorning a wide variety of objects. His main business continued to be jewelry design and fabrication, but he was noted for his household wares. In addition to inkwells and other desk accessories, Schon assembled the shells of sea creatures to create lamps and chandeliers, bookends and boxes, hairbrushes and hand mirrors, candlesticks, trays, and many more creations—even a shoe-scraper made from two sea horses. In advertisements for his wares, he promised that there was something for every pocketbook. Available, too, were luxury goods for the complicated elite rituals of home entertaining: a variety of dishes and spoons to serve bon-bons, olives, crab meat, salt, and more. He even fashioned seashells into trophies for boating and yachting competitions. Schon was (and remains) best known for jewelry made from silver-plated seahorses. He fashioned small ones into bracelets, brooches, and pendants, all sold at relatively affordable prices.

The charm of Schon’s innovative work helped him prosper in spite of his lack of training in advanced silversmithing techniques. One writer compared Schon’s work to that of the most highly regarded gold- and silversmith of European history, proclaiming that “[t]he skill of Benvenuto Cellini himself seems to be rivaled by [Schon’s] modern processes of silver plating the exquisite shells.” While perhaps that is an overstatement, there is no doubt that Carl Schon’s work—including the sea urchin inkwell at Mystic Seaport Museum—continues to awe and amaze.

Dr. Katherine Hijar, Curator of “Sea as Muse ”

Over the past decade, the Museum’s collections have significantly expanded in the area of material culture related to ocean liners. Two major donations—one from Linda Witherill, highlighted in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of this magazine—and strategic acquisitions by Museum staff have enriched the collection with thousands of postcards, hundreds of photographs, letters, paper ephemera, and a variety of 3-D objects. These items are all remnants of a bygone era when ocean liners were the dominant mode of transatlantic travel, offering luxurious palaces on the sea for the wealthy and a means of escape and opportunity for emigrants seeking new lives elswhere, especially in the United States.

Among the most visually striking pieces in this growing collection are the vibrant posters used to advertise these vessels and their respective shipping lines. As colorful and decorative as the lavish ships they represented, many of the posters were created by renowned graphic artists and represent a wide range of styles, from the flowing elegance of Art Nouveau and the bold geometric shapes of Art Deco to the simple sophistication of Midcentury Modern design.

A recent donation added nearly forty ocean liner posters to our collection. Collected and donated by Museum volunteer Dr. Christopher Morren, this acquisition includes highlights from the 1950s and 1960s, an era that saw a decline in the popularity of ocean liners due to the burgeoning commercial airline industry. As a young boy, Morren would often stop by various shipping company headquarters in New York City on his way to choir practice and request posters to add to his collection. Among the standout pieces he donated are two bold posters from the Holland-America Line, both designed by Dutch graphic artist Reyn Dirksen (1924-1999), who also created posters for the Europe-Canada Line and the Royal Interocean Lines. One poster, advertising the SS Maasdam and SS Ryndam, showcases the iconic yellow, green, and white funnel of the Holland-America line towering above the deck, with lifeboats elegantly arranged below. During this era, ocean liners played a significant role in post-war European immigration to the United States. The SS Ryndam, in fact, carried two immigrants from the Netherlands—Edward and Alex Van Halen—who would go on to become rock legends in the 1980s band Van Halen. Another Dirksen poster, promoting the construction of the SS Statendam, showcases the lines of the ship’s plan, which roll up partway across the poster, revealing an image of the completed vessel. The word “achievement,” rendered in all lowercase, foreshadows the ship’s later success as a favorite for transatlantic crossings.

Among other highlights in the Morren donation are a series of lively posters from the Grace Line, advertising Caribbean and South American cruises aboard the line’s famous “Santa” ships. These posters showcase colorful and detailed artwork by marine artist Carl G. Evers (1907-2000), whose work is also represented in other areas of our collection. Another standout is a series of posters for the Cunard line, most of which present a more traditional style of ocean liner advertising. These posters promote well-known ships like RMS Mauretania, RMS Caronia, MV Britannic, and a stunning depiction of RMS Queen Elizabeth at night, beneath a sapphire sky of twinkling stars.

A recent acquisition by the curatorial staff adds even more visually striking posters to the collection, including examples from the Holland-America Line, the United States Lines, the American Export Lines, and the Red Star Line. The two Red Star Line posters both date from the turn of the century and feature eye-catching Art Nouveau designs. One poster, by Belgian artist Henri Cassiers (1858-1944), shows three women in brightly colored dresses and hats standing on the shore, watching a Red Star Line ship pass by. Two small children accompany them, one of whom is playing with a toy model of a sailing ship—a nostalgic nod to an earlier era when sail-powered vessels ruled the seas. Considering their fragile and ephemeral nature, it is a miracle that many of these posters survived. It is our goal to continue to collect and preserve these remarkable pieces, ensuring that we document an era when ocean liners ruled the seas.

Krystal Rose, Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs

Collections, Ever-evolving

The Museum has been acquiring new materials regularly since its founding in 1929, resulting in an enormous and constantly expanding collection that can be divided into four main categories: general (consisting of art and objects), archival, watercraft, and film and video. As the Museum has grown and changed, so has the scope of what we collect. When new material is added to our collection, it goes through the accessioning process, which is to record the item in order of its acquisition and formally and legally add the piece to the collection. Without officially accessioning an object, there is no way in which a museum can prove legal ownership of it. Though new material is sometimes acquired through purchases, gift donations are by far the most common. We receive donation offers on an almost daily basis but obviously cannot take everything presented. Therefore, every offer is carefully considered by an internal Staff Collections Committee that meets monthly. This group looks at a variety of factors: how the offered gift supports our mission, what is currently in the collection, within which areas we would like to see the collection grow, the quality of the object, and most importantly, the provenance of the object. Provenance, or the record of ownership, can be one of the most important factors when considering whether to accept an object for acquisition. The more robust an object’s provenance, the more useful it can be to a museum and the more desirable it is for the collection.

As we work to refine our collections, it sometimes becomes necessary to deaccession objects. Deaccessioning is the formal act of legally releasing an object from the collection. This is a standard and healthy practice in every museum’s collections policy. The process is not taken lightly, and many different factors come into play when considering an object for deaccession. There are specific instances in which objects would be suggested for deaccession, including if it is no longer relevant to the collection, or if it is an inferior duplicate of something else in the collection. Regardless of the reason an object is chosen for deaccession, it will ultimately go through a very rigorous review process.

The processes of accessioning and deaccessioning are vital to the responsible management of museum collections. While accessioning ensures that new acquisitions are properly integrated and preserved, deaccessioning allows museums to refine their collections, improve their focus, and address practical concerns. Both processes require careful consideration, adherence to ethical standards, and a commitment to transparency and accountability. Through these practices, Mystic Seaport Museum can continue to fulfill our mission of inspiring an enduring connection to the American maritime experience.

Laura Nadelberg,

Registrar

Optimists Join the American Watercraft Collection

In 1947, designer and boat builder Clark Wilbur Mills (1915-2001) was asked by members of the service club Optimists International of Clearwater, Florida, to design a small, simple, and inexpensive to build dinghy for young people to create a maritime equivalent of the “Soap Box Derby.” Mills came up with the now ubiquitous Optimist dinghy. Mills was inducted into the National Sailing Hall of Fame in 2017.

The Optimist was originally intended to be built by home builders over a weekend from only two sheets of plywood. The rig was a simple cat with a sprit sail with wooden spars. Today, Optimists are one of the most popular sailing dinghies in the world. Over 150,000 are officially registered with the International Optimist Dinghy Class Association (IODA), with many more not registered. As many as 500,000 are thought to exist worldwide. Optimists are recognized as an International Class by the organization World Sailing as a “World Sailing Learn to Sail Boat.” They are sailed by sailors under 16 years old in over 200 countries. Over 80% of Olympic boat skippers learned to sail and many world-famous championship sailors began in Optimist dinghies.

Over the years, several Museum staff have expressed interest in collecting an example of this popular watercraft. Then, in 2024, as plans began for the Wells Boat Hall exhibition, by uncanny coincidence watercraft volunteer Peter Dickenson and I had been discussing this on the very day that Ben Fuller, former Mystic Seaport Museum Curator and renown small craft expert, emailed to ask if we were interested in an early Optimist—this boat #35 Doujigger II (2023.115). It was built in 1947, the first year they

were offered, and is a rare survivor. Optimist Doujigger II is historically significant due to its original construction and years of use, and being in remarkably good condition, it is likely the best we may ever find.

Naturally it followed that the Museum should also have a fiberglass Optimist to complement this early example. Two more were secured, Wind Steeler #9176 (2024.54) and It’s It (2024.60).

In 1960, newer fiberglass boats were designated International Optimist Dinghy (IOD), governed by the International Optimist Dinghy Association, with minor design changes and added flotation for safety. Today some are even fit with foiling dagger boards.

Optimists are still being built worldwide by a number of companies in both fiberglass and wood. Several YouTube channels offer instructional videos for the home builder. In 1947 it was estimated to cost around $50 to build a plywood boat. Today a new fiberglass Optimist runs about $4,000.

All three of these boats will be featured in the upcoming exhibit planned for the Wells Boat Hall. The exhibit will be divided into Sixteen “neighborhoods” grouping boats with a common theme. One “neighborhood” will focus on learning to sail. It will contain the Optimists and other boats like a Beetle Cat, Penguin Class dinghy among others that are commonly used for training. Wind Steeler will be compared to Doujigger II, the early wooden boat, and It’s It will be a interactive play boat nearby for kids to get in and play.

Quentin Snediker, Clark Senior Curator for Watercraft

UPCOMING

MAY

JUNE

JULY