Iceland

COMMUNITY, CULTURE, NATURE — SINCE 1963

NATURE UNSETTLED

What is the value of Iceland’s wilderness?

MUSIC BJÖRK HOMECOMING QUEEN

The musician on her “mushroom album” Fossora.

SOCIETY

THE RIGHT TO BEAR ARMS

The remarkable surgery that changed Guðmundur Felix’s life.

Review

G et lo s t wit h i n th e c it y

CONTENTS

NEWS IN BRIEF 6

ASK ICELAND REVIEW 8

IN FOCUS

THE PRESCHOOL SYSTEM 10

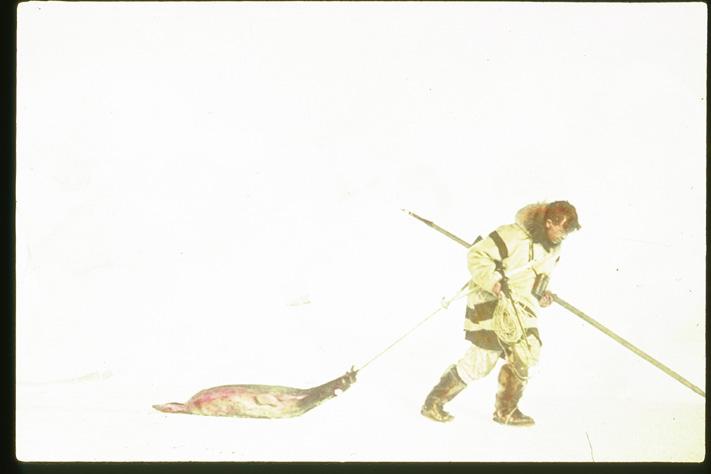

LOOKING BACK THE MIXED LEGACY OF ARCTIC EXPLORER VILHJÁLMUR STEFÁNSSON 72

FICTION

THREE MICRO STORIES BY ELÍSABET JÖKULSDÓTTIR 120

SOCIETY

IN HARM’S WAY 14 Iceland’s new addiction crisis and those battling it.

THE RIGHT TO BEAR ARMS 24

The remarkable surgery that changed Guðmundur Felix’s life.

MUSIC

HOMECOMING QUEEN 64 Björk on her “mushroom album” Fossora.

LOVE, BRÍET 32

Has rising to local fame changed the pop star?

LITERATURE

I WILL DANCE AGAIN 110

Writer Elísabet Jökulsdóttir on kidneys, creativity, and King Boredom.

FOOD HOME COOK 42

A voyage into Gísli Matthías Auðunsson’s taste of Heimaey.

COMMUNITY

GATHERING 98

Our journalist makes himself at home at a traditional sheep roundup.

NATURE

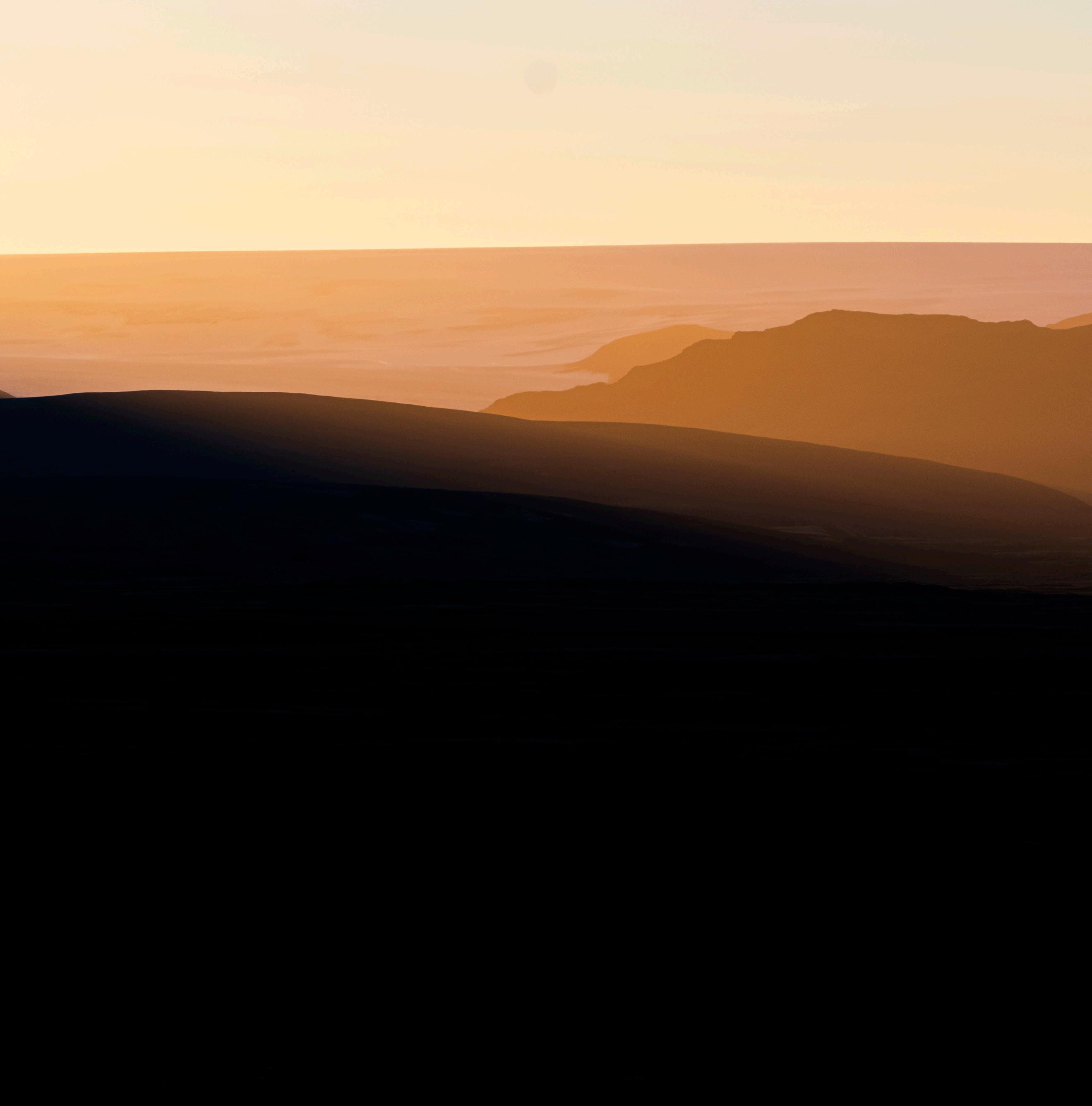

UNSETTLED 50

What is the value of Iceland’s wilderness?

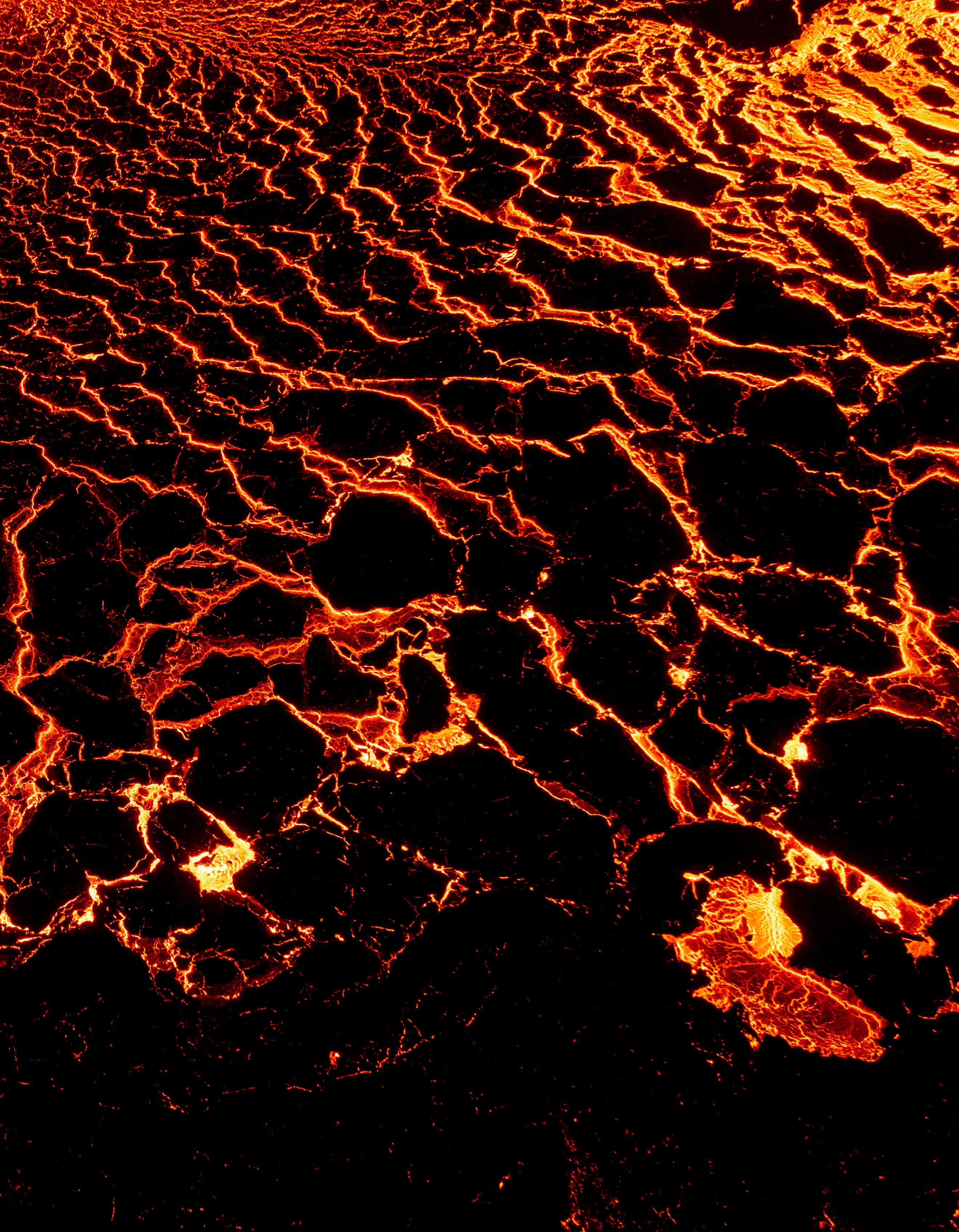

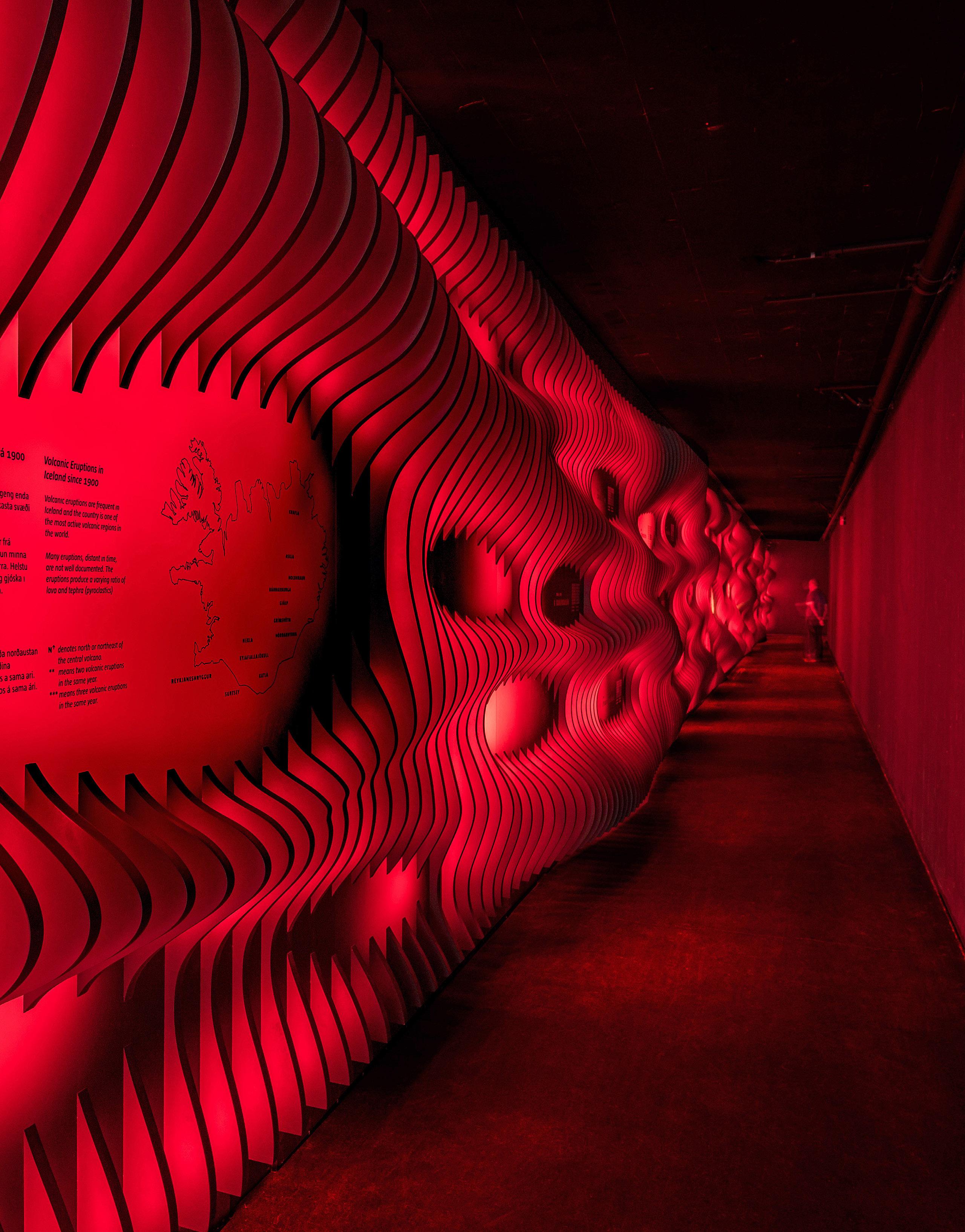

WHERE THERE’S FIRE 82

The volcanic reawakening of the Reykjanes peninsula.

CONTRIBUTORS

Editor

Gréta Sigríður Einarsdóttir

Cover

Golli

Kjartan Þorbjörnsson

Design

Daníel Stefánsson

Writers

David Timmons

Erik Pomrenke

Frank Walter Sands

Jelena Ćirić

Ragnar Tómas Hallgrímsson

Golli

Viðar Logi

Dartmouth College Library

Illustrator

COVER PHOTO: Golli. By Kjölur, between two glaciers.

Elín Elísabet Einarsdóttir

Translator

Larissa Kyzer

Copy editing

Jelena Ćirić

Proofreading

Erik Pomrenke

Zachary Jordan Melton

subscriptions@icelandreview.com

Advertising sales sm@mdr.is

Ltd.

(worldwide)

For more information, go to www.icelandreview.com/subscriptions

Head office MD Reykjavík, Laugavegur 3, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland, Tel.: (+354) 537-3900. www.icelandreview@icelandreview.com

No articles in this magazine may be reproduced elsewhere, in whole or in part, without the permission of the publisher. Iceland Review (ISSN: 0019-1094) is published six times a year by MD Reykjavík in Iceland. Send address changes to Iceland Review, subscriptions@icelandreview.com .

2 | ICELAND REVIEW FEATURES TABLE OF

icelandreview.com

photo

Publisher

& production

Photographers

Subscriptions

Print Kroonpress

5041 0787 Kroonpress NORDIC SWA N ECOLAB E L Annual Subscription

€72.

whale watching húsavík eco-friendly since 1995 www.northsailing.is call +354 464 7272 or book your adventure at Pick your favourite whale watching tour!

FROM

Travellers to Iceland often remark that it must be such a privilege to grow up surrounded by Iceland’s mountains and ocean views. In many ways, it is, but the thing about growing up anywhere is that you get so used to your surroundings, they start to feel eternal. When the mountains have always been there, it feels like they’ll always be there. There’s no sense of urgency to experience them.

In the early 21st century, all of a sudden, the eternity of Iceland’s highland was under threat. Kárahnjúkar in the mountains of East Iceland was a little-explored area that many had never heard of until plans were underway to dam a river, plunging the whole area into a lagoon to feed a hydroelectric dam.

To make matters worse, the majority of the power created by these drastic measures would be used to power a single aluminium smelter.

It had happened before. In the 1930s a whole valley in North Iceland, including seven farmsteads, went underwater. At the time, the wilderness felt like an endless resource, the desolate highlands useless until we harnessed its energy to light our homes and power our factories. In the 21st century, wilderness is facing extinction and the country’s mountainous interior represents more than an empty wasteland. A turning point in the way we view Iceland’s nature was the time when we realised there was a chance it would be taken away from us. It was at that time that Björk discovered she had an interest in politics because it affected something that was close to her heart. Author Elísabet Jökulsdóttir also took part in the fight to keep Iceland’s wilderness wild.

Guðmundur Felix is an Icelandic man who lost both his arms in an accident more than 20 years ago. Just last year, he had the world’s first successful double arm transplant surgery. While that’s impressive, even more impressive is the stoic serenity that he found when he realised his misery wasn’t due to the accident, but his resistance to accepting reality. It’s not until you recognise your reality for what it is that you can begin to change it. And through the music of pop star Bríet, our journalist also remembered what’s truly important.

In this issue, we asked scientists, politicians, and environmentalists about the price of Iceland’s wilderness, and admired the fiery side of its everchanging nature when a volcano erupted about a 45-minute drive from Reykjavík. We tasted the fresh herbs growing out of volcanic sand on the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago and caroused with the farmers of North Iceland celebrating the age-old tradition of drinking a lot after bringing their sheep in for the winter.

It’s life as it’s always been, transformed.

Editor Gréta Sigríður Einarsdóttir

Photography by Golli

Editor Gréta Sigríður Einarsdóttir

Photography by Golli

4 | ICELAND REVIEW

THE EDITOR ICELAND REVIEW · ISSUE 05 – 2022

Join the largest mobile network in Iceland SIM card | 5 GB data 5 GB 50 international min. | 50 sms 2.900 ISK 2.900 ISK SIM card | 10 GB data 10 GB Only data – No calls +354 800 7000 siminn.is / topup siminn.is / prepaid siminn.is siminn siminnisland For more information:

Inflation rates dropped in August to 9.7%, suggesting that this trend is beginning to cool and that housing prices may stabilise in the coming months.

01 Blönduós shooting

Tragedy struck the small community of Blönduós in North Iceland in late August when two people died, and one was injured in a shooting. In the early morning hours of August 21, a man entered the home of his former employer with a shotgun. The perpetrator shot the homeowner and his wife before the couple’s son intervened. The shooting resulted in the death of the woman and of the shooter. The father was rushed to the hospital in serious condition. The son was initially arrested for killing the attacker but was later released.

02 Market inflation

Inflation rates in Iceland had been steadily increasing since the summer of 2021, reaching 9.9% in July of this year. This increase has particularly impacted the housing market in Reykjavík. Supply already falling well short of demand, and the inflation caused what apartments had been available to skyrocket in price. The situation has been particularly dire with the influx of not only tourists but also foreign workers coming to Iceland to fill the holes in the tourism workforce, as well as Ukrainian refugees desperately searching for housing. Thankfully, inflation rates dropped in August to 9.7%, suggesting that this trend is beginning to cool and that housing prices may stabilise in the coming months.

03 Film industry funding changes

The upcoming series of HBO Max television show True Detective will be filmed in Iceland over a 9-month period for a budget of around ISK 9 billion [$64.8 million; €63.9 million]. The project entails the largest-ever foreign investment in culture in Iceland’s history. Minister of Culture Lilja Alfreðsdóttir says the project is proof that government initiatives are helping put Iceland’s film industry on the map.

In recent years, the State Treasury has reimbursed up to 25% of the costs incurred by film and TV productions in Iceland, and recently announced that the percentage would be raised to 35% for projects that qualify. Shortly afterwards, however, the local film industry was dismayed to learn that the government also plans to cut funding to the Icelandic Film Fund by onethird. Industry experts say the decision erases an ambitious 10-year policy for the local film industry drafted just last year, and argue there is room in the budget to support both international and local projects.

Photography by Golli

Words by Zachary Jordan Melton and Jelena Ćirić

6 | ICELAND REVIEW NEWS IN BRIEF

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 7 MÝ VAT N N ATURE B ATH S pre-book online at m y v at nn a tureb at hs . i s R E LA X E N J OY EXP E RI E NC E

As you may have noticed from driving around Iceland’s countryside, there are many sheep. Historically, sheep were put to pasture in the highlands during the summer and then, as the weather turned for the worse, they were gathered up to be housed in sheds on the farmstead.

Farmers still live by this seasonal pattern in Iceland, letting their sheep roam the countryside and then rounding them up in the middle of September, the end of Iceland’s summer.

These roundups, or réttir, will vary depending on the community,

Q2 What can you tell me about North Iceland?

Traditionally, Iceland was divided into four quarters: North, South, East, and West. This was of course a geographical division, but it also had important implications for the legal system in medieval Iceland. Each district had its own legal assemblies where local matters would be solved. More important matters, and issues of unclear jurisdiction, would be brought before Alþingi, the national assembly.

Today, Iceland is organised differently, but when people talk of “going North” or to other regions, the modern usage still conforms largely to the historical boundaries of these districts.

The largest settlement in North Iceland is by far Akureyri, with some 20,000 inhabitants. In fact, Akureyri is the largest settlement outside of the capital region. Akureyri is a charming town with a

but they all generally happen in early September. Your best bet is to check the agricultural and farmers’ newspaper, Bændablaðið.

Réttir are a time when an entire community comes together to pitch in. It’s a lot of hard work to collect and wrangle all of the livestock, but many communities will also have a big party afterwards, called a Réttarball. There tends to be plenty of singing, dancing, and drinking at these celebrations since it’s the last gasp of summer fun before the winter!

bustling but modest walking district. We recommend seeing the church, botanical gardens, and harbour. For winter visitors, Akureyri also has some excellent ski slopes.

Húsavík is also another small but important settlement. A historical fishing and whaling village, it remains an excellent place to go whale watching and is a very popular summer destination. North Iceland also has numerous natural features, such as Dettioss and Goðafoss waterfalls, lake Mývatn, the Dimmuborgir lava fields, and Ásbyrgi, an impressive horse-shoe shaped canyon near Húsavík.

Besides that, North Iceland is also known rather surprisingly for its summers, which are often warmer and clearer than in the capital region.

Q1 When and where are the September sheep roundups scheduled?

ASK ICELAND REVIEW

Photography by Golli Words by Erik Pomrenke

8 | ICELAND REVIEW

HIGH QUALITY HOUSES IN THE NORTH OF ICELAND

FNJÓSKÁ NOLLUR

A loft apartment with incredible views of the fjord.

1 bedroom, 1 bathroom, sleeps 2 (4)

HRAFNABJÖRG AKUREYRI

A very well situated, exclusive villa opposite Akureyri.

bedrooms, 3 bathrooms, sleeps 6

LEIFSSTADIR AKUREYRI

Exclusive villa in the vicinity of Akureyri.

bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, sleeps 8

VALLHOLT GRENIVIK

A spacious, luxurious house at the shore.

3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, sleeps 6

SÚLUR NOLLUR

A wonderful holiday house with an elegant interior.

1 bedroom, 1 bathroom, sleeps 4

KRÝSUVÍK NOLLUR

A convenient loft apartment on the Nollur farm in Eyjafjörður.

bedrooms, 1 bathroom, sleeps 4

and booking www.nollur.is

Photo: Thomas Seiz

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 9

4

3

2

Details

NOLLUR Húsavík AKUREYRI Vík Höfn Eskifjörður REYKJAVÍK

A rocky start

An announcement on the City of Reykjavík website advertises employment at the city’s many preschools. In addition to the rewarding work of childcare, benefits such as free lunch, a shortened work week, a swim pass, and prioritised placement for one’s own children on preschool waitlists are all enumerated. On paper, this sounds like an excellent offer, and one can imagine a parallel world in which working in Iceland’s preschool system is highly sought after.

However, this fall has been a chaotic one for preschools throughout Iceland. Teacher shortages, long waitlists, and inadequate facilities have combined to cause something of a crisis in childcare. At the time of writing, some 70 vacancies exist for positions in the preschool system, and 700 children aged 12 months and older remain on preschool waitlists in Reykjavík alone.

In August, parents brought their children to stage a “sit-in daycare” at Reykjavík’s City Hall in protest. Their statement was simple and forceful: if Iceland’s parents are to continue participating in the economy, then the city council must fulfill its promise of preschool placements for all children one year and older.

Preschools in Iceland

The preschool system in Iceland is the first level of public education, intended for children up to six years of age before they start their compulsory education. The current framework for preschools was laid out and reformed in the 2008 Preschool Act, which outlined the social role that the preschool system must play, in addition to the skills and values that must be taught to children in Iceland.

Icelandic preschools are also a very important source of employment throughout the nation, with around 5,500 full-time employees. Working in Icelandic preschools is common among

young people and recent immigrants, with many saying that one of the best ways to learn the language is by interacting with children. There are, however, problems with the current system.

Although preschool teachers must undergo a 5-year course of study, much of the work in many preschools is still performed by nonpedagogical staff. During a time of extreme staff shortages, many are wondering if a 5-year degree is necessary, or even if proficient Icelandic ought to be a requirement. Preschool positions also pay relatively low wages, providing little motivation to pursue a master’s degree. An obvious solution to the staffing shortage is, of course, to increase the wage and therefore make work in the preschool system more attractive. But given the large number of Icelanders and immigrants employed in preschools, even modest wage increases could lead to budget crises for municipalities.

Bridging the gap

Although the breaking point reached this year has raised particularly strong critique, the lack of preschool places has been a known problem for some time. In the last decade, the capital region of Iceland has seen tremendous population growth and infrastructure has struggled to keep pace. This growth is not only due to immigration, but to a steady increase in the birth rate, due in part to a COVID baby boom. From just 2020 to 2021 alone, the birth rate increased by 8%. Clearly, the current wave of children has not emerged from nowhere.

Since 2018, the city initiative Bridging the Gap (Brúum bilið) has aimed at a city-wide expansion of preschool capacity. The problem was arguably worsened when, in the last election campaign for Reykjavík City Council, promises were made that children would be guaranteed a spot in preschool from the age of 12 months.

The age at which children are guaranteed a spot in preschool

Photography by

Photography by

10 | ICELAND REVIEW

IN FOCUS The Preschool Dilemma

Golli Words by Erik Pomrenke 18,852 CHILDRENENROLLEDIN PRESCHOOLS 5,523 FULL-TIMEEMPLOYEES

Adventure Ground

ON THE SOUTH COAST

All in one place

From Reykjavík the Adventure Bus is the easiest way to an unforgettable adventure. Need a ride?

Adventure Ground Offered by: Mountain Guides & Arcanum

An exciting selection of outdoor activities in the beautiful south coast of Iceland. With regular departures from two dedicated Base Camps, less than 10 minutes driving distance from each other, you can fill your day with adventure.

Book your adventure now AdventureGround.is or call us +354 587 9999

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 11 Adventure Ground Sólheimajökull Mýrdalsjökull Skaftafell

Three

In the

of

Fríkirkjuvegur

Safnahúsið

12 | ICELAND REVIEW

Center

Reykjavík

Locations www.listasafn.is+354 515 9600 Listasafn Íslands National Gallery of Iceland Hús Ásgríms Jónssonar Home of an Artist

The House of Collections Bergstaðastræti 74 101 Reykjavík Hverfisgata 15 101 Reykjavík

7 101 Reykjavík

varies between municipalities, with many setting the age at two years, others at 18 months. Ideally, the age at which children are eligible for preschool will correspond to the end of the caregivers’ parental leave, but this is not often the case. Most Icelanders receive 6 months’ paid parental leave, meaning a couple raising a child will have up to 12 months of total leave, with 6 weeks of that total being transferable between the two.

With most preschools only beginning to accept children at 18 to 24 months, these final 6 to 12 months are a gap left in the childcare system. Solutions so far have proved to be a patchwork. Some parents will extend their leave, meaning they receive the same total pay stretched out over a longer period of time. Others rely on paid daycare services or the help of their wider family network to bridge the gap. Both of these solutions, however, favour higher-income natives with social support to raise their children, leaving many lower-income Icelanders and immigrants out in the cold. This gap between parental leave and preschool is the major reason the preschool system became a hot-button issue this last election cycle in the City of Reykjavík.

Increasing capacity

By 2025, the Bridging the Gap initiative plans to increase preschool capacity by at least 2,000, including opening ten new preschools in addition to numerous other expansions of existing preschools. However, the drive to expand capacity is only one part of the solution, and critics would say that it is unfeasible when enough qualified staff cannot be hired for the system as it currently is. Nor will the next graduating class of preschool teachers do much to meet demand, as the majority of pedagogy students pursuing degrees in child development and education are already employed in the preschool system.

Is the solution to simply shorten the training period for preschool teachers to produce new generations of educators more quickly?

Most educators would say no, and most parents would prefer their children being cared for by an educated and trained individual. And yet the question remains; what to do with all these children whose parents want to – or have to – return to work?

Consequences and fallout

In addition to the critical role played by preschools in the education and development of children in Iceland, the preschool system has also played an important role in furthering gender equity. No longer confined to the role of caregivers, Icelandic women have been free to pursue their careers, and, as the preschool system reaches a crisis point, many wonder whether it will force women back into domestic roles.

It is not clear what the solution is, and every proposal seems like a chess move countered with unforeseen consequences. Some new preschools have already opened this year, and some have been expedited into service to meet demand. Nevertheless, the staffing and facility shortage remains. What is clear, however, is that solutions to the preschool crisis will require long-term planning, not short-term reactions.

If preschool pedagogy is to require a 5-year degree, then it ought to be a wellremunerated position, securing a middle class standard of living. Both teachers’ wages and general social attitudes towards teaching as a profession need to be reconsidered. At the same time, authorities and municipalities need to plan ahead more carefully, taking demographic trends into account and making decisions at larger timescales than election cycles. Icelandic children – and children everywhere for that matter – deserve to be raised in safe environments rich in developmental, pedagogical, and psychological resources.

Of course, all of this will cost money. Where will it come from? Your guess is as good as ours.

Photography by Golli

by Erik Pomrenke

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 13

IN FOCUS The Preschool Dilemma

Words

ISK58.1BILLION TOTALCOSTOFPRESCHOOLS INICELAND ISK2.7MILLION COSTPERCHILD

In Harm’s Way

Words by Ragnar Tómas Hallgrímsson

Photography by Golli

Words by Ragnar Tómas Hallgrímsson

Photography by Golli

GUNNI MARÍS

On Thursday, November 25, 2021, I left a COVID testing clinic near the Kringlan shopping centre in Reykjavík. Stepping into my car, the phone rang and an unknown number appeared on the screen. I listened as the voice of an old acquaintance, meek but quietly upbeat, worked its way through the speaker. We had known each other through music, and as we exchanged pleasantries, my mind – always guessing at uncertainties –wondered whether he had some kind of a collaboration in mind. That notion was quickly dispelled.

Gunni Marís needed money.

He was getting back on his feet after rehab but because he was unvaccinated, the charity organisation Mæðrastyrksnefnd (Subvention for Mothers) was refusing him and his mother help. I assumed he was lying, and as we talked, tried to invent an excuse for being unable to help (while evangelising on the importance of vaccines). But he wasn’t asking for much: two or three-thousand króna. The modesty of the request so surprised me that I said “yes” almost immediately and was left thinking that he was clever; as opposed to asking a handful of people for generous donations – and being frequently rebuffed – he was, I conjectured, asking everyone he knew for small amounts.

I hung up and transferred the money.

A few weeks passed before Gunni Marís called again. Answering the phone and recognising his voice, I found myself wishing I had saved his number – so that I could have screened his call. Again, he asked for a meagre amount of money, to which I replied that I’d “consider it,” caveating this consideration with the sentence, “I can’t make a habit of this.” This time, I saved his number on my phone and, after some deliberation, transferred 3,500 króna into his account.

The final time that he called, sometime in spring, I did not answer. By August, he was dead.

A NEW OPIOID CRISIS

When asked if talk of a “new opioid crisis” in Iceland is an exaggeration, Dr. Valgerður Rúnarsdóttir, the Medical Director of SÁÁ (National Centre of Addiction Medicine), refers to the data: between 2010 and 2022, the percentage of patients being treated for opioid addiction at the Vogur detox centre and rehabilitation hospital rose (from 10.3% to ca. 30% of the clinic’s patients). These patients are twice as likely to relapse than others, and thirty-five of those who have sought treatment over the past five years have died.

“We know what’s happening because we see such a broad range of people. So, no – it’s not an exaggeration to say that a new opioid crisis is upon us.”

16 | ICELAND REVIEW

This does not necessarily mean, however, that the number of people struggling with substance-use disorder is on the rise, but rather that opioids are becoming more common among that subset.

“Often when people read a news article,” Valgerður explains, “citing statistics on drug-related deaths, for example, they think that these people are dying on the street. But that’s not the complete picture. Drug-related deaths can mean overdoses and suicides – but it can also mean that someone died in an accident and happened to be taking codeine tablets.”

According to the investigative journalism programme Kompás), 21,000 people are categorised as “long-term users of addictive drugs” in Iceland. Five-hundred people were prescribed Oxycontin in 2011. In 2021, that number had increased sevenfold, or 3,500.

As Valgerður notes, opioids relieve pain but they also produce a high, which is problematic for individuals who struggle with addiction: “Opioids are extremely useful in treating acute illnesses,” she says, “in palliative care, or surgeries, but when people are using opioids to treat chronic back pain, for example – you can say that the pendulum has swung too far in the wrong direction. In that case, almost every other form of treatment is preferable, whether exercise, physiotherapy, etc.”

“NO – IT’S NOT AN EXAGGERATION TO SAY THAT A NEW OPIOID CRISIS IS UPON US.”

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 17

Iceland is currently undergoing its second opioid crisis, sponsored, at least in part, by increased prescriptions. The first opioid crisis began at the turn of the last century; in the late 1990s, the directors of Vogur – seeing an increase in opioid use and opioid injections among patients – responded by establishing medication-assisted treatment in 1999.

While most people are familiar with Vogur’s detox and rehab facilities, which has beds for 60 patients and admits approximately 600 new patients annually, fewer will have heard of the clinic’s medication-assisted treatment (MAT for short). But it was this treatment, Valgerður maintains, alongside the adoption of a prescription database by the Directorate of Health, which helped stabilise the first crisis during the early aughts.

Since then, Vogur’s MAT has gradually expanded and currently treats 250 patients (most of whom have injected opioids or have suffered serious consequences as a result of their addiction). These patients receive methadone, buprenorphine pills, or injections, reducing their withdrawal symptoms and cravings for opioids.

“It’s an evidence-based approach, and there’s a low threshold for participation. We’d be seeing a much higher overdose rate if it weren’t for this programme. We also collaborate with other healthcare and social services to help people become sober. If we want to improve the lives of these people, these factors must be entwined.”

Although most of the patients in Vogur’s MAT are either sober or aspiring toward abstinence, there are also some who are not ready to quit. It is important to provide services to these individuals, and the City of Reykjavík, according to Valgerður, has greatly improved access to housing for this group of people over the past years. “Things are much better today compared to ten years ago,” she states, adding that besides offering treatment and other services, removing stigma is also vital.

“We’ve certainly seen a change in attitudes over the past 20 or 30 years – and especially in Iceland. If you’re employing someone who has a substance-use disorder, you tell that person to go to rehab. This isn’t necessarily the case in other countries.”

When asked if the rumour was true: that the only two offices in Iceland that have not had a representative at Vogur are the office of the President of Iceland and the Bishop of Iceland, Valgerður seems to insinuate that even those venerable offices have not been unaffected by addiction:

“I don’t want to generalise,” Valgerður says, and lets out a hearty laugh.

MADAME RAGNHEIÐUR

There are 1,000 intravenous drug users in Iceland, 600 of whom are clients of Frú Ragnheiður: a specially-equipped medical reception vehicle that cruises the capital area six evenings a week and operates according to the philosophy of “harm

18 | ICELAND REVIEW

“IT’S AS IF HE DOESN’T UNDERSTAND THAT TAKING DRUGS AWAY FROM THIS VULNERABLE GROUP OF PEOPLE IS A FORM OF PUNISHMENT. THE EFFECTS OF WITHDRAWAL ARE EXCRUCIATING.”

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 19

reduction;” focusing on the consequences and risks of drug abuse over abstinence. Frú Ragnheiður provides clean injection equipment, condoms, and advice on safe injection methods to prevent bloodborne diseases such as HIV and Hepatitis C –offering succour to Iceland’s most vulnerable habitual users.

“We’re seeing an increase,” Kristín Davíðsdóttir, Director of Frú Ragnheiður, observes, “both in terms of the number of individuals and the number of annual visits. I can’t say whether there’s an increase in actual users, but overdose deaths are definitely on the rise.”

Last year, drug-related deaths reached an all time high in Iceland (46), and to Kristín, our inability to prevent these deaths has something to do with the fact that we’ve adopted a one-size-fits-all approach to addiction treatment. “We need to improve access and offer a greater variety of options,” Kristín explains. “This is not a uniform group of people.”

As Kristín notes, Vogur is the only institution that offers withdrawal treatment in Iceland – and the waiting period for admission is overly long. According to data from the clinic, for those attending their first treatment, or if a long time has elapsed since their last treatment, the average waiting time is 2-4 weeks. For everyone else, it’s 2-4 months.

“And when you’re injecting yourself with opioids, every single day matters,” Kristín explains.

Besides offering a greater variety of treatment, another key to reversing the trend in overdose deaths is, as Valgerður

Rúnarsdóttir noted, removing the stigma placed on drug users – who are often reluctant to call the police for fear of the consequences. In this regard, the legislator can be of use.

This summer, a bill to decriminalise drug possession for personal use was shelved (ostensibly owing to lack of popular support, which was also the case in 2015), but as a compromise, the Minister of Health announced that a new bill would be submitted this winter. The new bill would repeal punishment for the “most vulnerable” people – but only in special instances and for a specific quantity. While the words sound reassuring, they appear to belie the minister’s lack of awareness regarding the realities of addiction, with the bill having raised several questions about implementation. Kristín, an advisor on the Minister’s work group, is critical of the entire process.

“We haven’t finished our work nor reached any conclusion. It’s hardly a fully formed piece of legislation. Nonetheless, the Minister of Health has appeared in the media stating that it’s not about ‘decriminalisation’ but about ‘removing punishment.’ But it’s as if he doesn’t understand that taking drugs away from this vulnerable group of people is a form of punishment. The effects of withdrawal are excruciating.”

Kristín believes that we’re pushing these people further to the extremes, which is the opposite of what we should be doing. Whenever the police are dispatched to intervene with people struggling with an opioid addiction, they often seize their drugs, taking it for granted that they’ve been obtained illegally.

“It would be like the cops barging into our homes and taking our prescription medicine,” Kristín explains. “No one judges these people as harshly as these people themselves. When they seek help from our institutions, they often become defensive. They’re afraid and insecure. Most have a history of trauma.”

Kristín maintains that we need to integrate various institutions within the system, the healthcare and the social system, for example, to make sure that we’re adopting a more holistic approach:

“To quote our clients: ‘you can’t sleep on the street without using drugs,’ so how are you supposed to stay sober when you don’t have a place of refuge?”

MENTAL HEALTH AND ADDICTION

Erna Hinriksdóttir is a psychiatric resident employed at the outpatient clinic at the National University Hospital of Iceland who also works shifts at the hospital’s psychiatric emergency department. Having initially planned on studying paediatrics, Erna was led into the field of psychiatric medicine by dint of chance and curiosity.

“I began working at the psychiatric ward as a medical student – and sort of got sucked in; it was fascinating, interacting with people dealing with these serious conditions, whether schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.”

As a former volunteer who used to ride along with Frú Ragnheiður (she still works on call), Erna was introduced to the practical benefits of “harm reduction” and has been a proponent of the approach since. Although still very much on the fringes, harm reduction is gradually making inroads into healthcare institutions in Iceland (the Laufey project within the

20 | ICELAND REVIEW

National University Hospital, for example.)

“The approach differs from that of rehab clinics and addiction wards where the message has usually been ‘Stay sober or get out,’ whereas harm reduction measures success along a different metric: helping an individual to stop using opioids intravenously, for example, or substituting opioids for something else,” Erna explains.

Given that there is a high rate of comorbidity between addiction and other mental illnesses, many of the individuals who seek help at the psychiatric emergency department are also struggling with substance abuse.

“The two often go hand in hand,” Erna observes. “Substance abuse is often conducive to mental illness. Likewise, those who are diagnosed with mental illnesses tend to seek relief by self medicating. When people are far gone, it affects their income, social network, housing, etc.”

For the system to better assist individuals struggling with opioid addiction, Erna believes that there needs to be acceptance of the fact that not everyone is prepared to quit.

“We need to help people unwilling to seek help at the hospital or other treatment centres or who are not yet ready to become sober. Ensuring that those who are using these drugs are not deprived of important resources – such as housing, interviews with social workers, etc. – because experience has taught us that if these resources are provided, these people are more likely to recover. I think we’re lacking this middle stage of

treatment for people who aren’t ready to quit but would like to curb their consumption.”

As far as more practical matters are concerned, Erna agrees that there needs to be a greater investment on behalf of the government. As has been widely reported, the mental health facilities in Iceland are greatly lacking, and there’s a shortage of psychiatrists and nurses. “Which is not something that you just pull out of your sleeve,” Erna admits.

Listening to Erna and other health professionals who are “on the ground,” so to speak, I get the feeling that the traditional view of addiction, that people who struggle with addiction are morally reprehensible agents responsible for their own travails, has been supplanted with the notion that they are a product of their circumstances (whether personal circumstances: genetics, physiology, trauma, etc. or societal ones), and that we, as a society, share some responsibility for those circumstances; no one willingly chooses to become addicted.

As far as recent developments are concerned, Erna, like most of her colleagues, is reluctant to generalise on the rise of opioid abuse in Iceland. She agrees, however, that we’re probably seeing similar trends to the mental health crisis among adolescents in the US.

“And it’s not just adolescents. The breakneck speed of our society, and new technology, which sets us up for constant comparison, appears to adversely affect our moods, leading to increased anxiety and depression.

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 21

“REST IN PEACE, FRIEND.”

THE FINAL TIME THAT HE CALLED, SOMETIME IN SPRING, I DID NOT ANSWER. BY AUGUST, HE WAS DEAD.

THE EULOGY

Gunnar Marís was, as his friend Jóhann Dagur Þorleifsson (Jói Dagur to his friends) observes, an outsized character and a “great friend to Icelandic hip hop.”

The two met in 2007, through rapper Gísli Pálmi, and quickly became close collaborators. “Gunnar Marís had this effortless talent for rapping, with many of the lyrics he recorded over my beats being improvised on the spot,” Jói Dagur recalls.

During those 15 years between their first meeting and Gunnar Marís’ untimely death, the latter was “in and out of the psych ward” and waged a long battle against addiction. Along with making music, he enrolled in the Icelandic Film School in 2013, subsequently landing minor roles in TV shows and independent films, while spiralling ever deeper into substanceabuse.

The two friends entered rehab separately in 2018, which was when Gunnar Marís finally managed a spell of sobriety. During that time, he seemed to have regained a sense of purpose and peace, which was why his relapse 18 months later – came “like a bolt out of the blue.”

“He returned to Vogur but walked out,” Jói Dagur explains. “He went to the psych ward. He tried detoxing a few times. All of it, to no avail … it’s difficult to help someone who doesn’t want help.”

On Friday, August 12, Jói Dagur bade his friend a final farewell. The funeral also marked the first time in 12 years that all nine members of their rap collective, 3. Hæðin, were convened beneath the same roof. The church was filled with friends and collaborators, among them rapper Erpur Eyvindarson (a.k.a. BlazRoca).

In his eulogy, Erpur recalled that he had met Gunnar Marís just over fifteen years ago, that he had been passionate about music, full of dedication and industry. Many would have written him off as “a dreamer,” but at the time, Gunni Marís had already won the Rímnaflæði rap competition, released a handful of well-regarded songs, and collaborated with big names from the Icelandic rap scene, including Helgi Sæmundur (Úlfur Úlfur), Forgotten Lores, Dóri DNA, and slew of other talented rappers who were gathered in the church on that day. Erpur noted that, time allowing, he probably would have belonged to that list of collaborators but that those plans faded in the past two or three years – like most all of the good things in Gunnar Marís’ life.

After recalling the deceased’s memorable brush with the law, Erpur shed light on the character of his late friend and the poison that had claimed his life.

“Gunnar Marís worried about more than his own skin. He wanted to reach people – even as a preacher. He found Jesus everyone now and then. But his Jesus was the one who overturned the tables of the money changers in the temples; the tables of those who believed that the sole purpose of living things is to sate the greed of those who own everything;

of those who start wars to sell weapons; and of those who manufacture addiction to sell us a vaporous key to a cage in which they’ve locked us …. who marketed much stronger opioids than had been previously seen here in this country – but that now are delivered in legal and more impressive packaging. You don’t have to be Jesus to want to overturn the tables of these money changers.”

Suggesting the high mortality rate of substance abuse among rappers, Erpur concluded his eulogy with a nod to those fighting to stay sober:

“To you, who remain, despite everything, alive. Jói Dagur and the rest of you, who manage to stay sober – we stand with you. You, who loved him dearest, and carry his memory – and keep his name alive – you have to live! Like they say in the Westfjords, ‘don’t you dare to die on me. If you die, I’ll kill you!’ You, who’ve plumbed the deepest valleys, now possess the greatest insight into an existence that other people don’t understand – unless they’ve dived off the cliff themselves. If pastor Þór hadn’t hidden the communion wine, I would raise a glass and toast to Gunni Marís, to some crazy stories, fine memories, and for all that he’s left behind: in lyrics, music, and expression. Cheers to the spirit, a different spirit than that which drowned you.

Rest in peace, friend.”

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 23

I’m sitting in a hotel lobby, scribbling some last-minute notes in my notebook before the interview. I look up and notice Guðmundur Felix Grétarsson entering so I raise a hand to let him know I’m here. He waves back, and I get up to greet him. He shakes my hand, and I introduce myself before he points to a small room where we can chat undisturbed. Nothing about this exchange feels remarkable to me, but Guðmundur Felix has a different perspective.

1998

Guðmundur Felix was working as an electronics engineer. He had two daughters, a four-year-old and another only three months. On January 12, he set out to do some work on a high-voltage transmission line. The line he was supposed to be working on was powered off, but on that fateful day, Felix reached out and touched a line that was very much powered on. Shocked by 11,000 volts, he fell 8 metres [26 feet]. He broke his back, fractured his neck, his ribs came loose, and his arms were set on fire. When he woke up, both his arms had been amputated at the shoulder.

Words by Gréta Sigríður Einarsdóttir Photography by Golli

24 | ICELAND REVIEW

The to 2013

Right Bear Arms

Drinking and using drugs to numb the pain was the destructive path Felix walked after his accident. “All of a sudden, I was faced with a life that I didn’t want to live,” he says. “Everything was gone. My relationship ended soon after the accident. Everyone around me was exhausted. I went from being this guy with a good job and his life ahead of him to being a helpless loser overnight. There came a point when I had to have a liver transplant to save my life, but I wasn’t eligible because of my addiction.”

“There’s no such thing as a short version,” Felix says when asked

straw. Then, a French culture festival in Reykjavík invited Dr. JeanMichel Dubernard to give a lecture at the University of Iceland. “I saw him on TV. I just started making phone calls all over town to find the guy. I called every hotel in the city until I found him at Hotel Holt and he agreed to see me.”

While Dubernard had the same misgivings about Felix’s case as the other doctors who had rebuffed him, he didn’t say no. “When everyone else had said ‘this isn’t possible,’ he said ‘I don’t know if this is possible. But whatever the answer is, I want to be able to give arguments to support it.’” So, in 2007, Felix dove head first into gathering his medical files. The next step was to translate everything into French. “I found some certified translators but they wanted to charge me an arm and a leg, so I went to the Ministry of Health. They said this wasn’t in their jurisdiction: they didn’t help with experimental procedures in other countries. Every door was closed until an acquaintance reminded me that Vigdís Finnbogadóttir used to be a French teacher before she became President. So I knocked on her door.” Vigdís connected Felix with a French paediatrician living in Iceland who was willing to help. With all the data sent to France, Felix waited for an answer.

2011

how he ended up in France two decades later, before launching into his tale. “I lost my arms in January 1998 but already in September, the team at the Lyon hospital performed the first successful double hand transplant. When you lose your arms, you keep an eye out for this kind of news.” Dr. Jean-Michel Dubernard was a pioneer in his field and the operation made headlines all over the world, but Felix didn’t speak any French. Later, one such operation was performed in China as well, “but I didn’t speak any Chinese either,” Guðmundur chuckles. “So when they perform a similar surgery in the US, a hand transplant, I reach out to the team who performed the surgery. That was in 2001.”

2001

A hand transplant is as complicated a process as it gets. The operation itself, where a horde of surgeons carefully stitch together skin, muscles, tendons, veins, and nerves, is only the first step. A potent drug cocktail of immunosuppressants is administered so the body doesn’t reject the new body parts, and the recovery means that nerves start to regrow, from the stitches and into the new limb, at glacial speed: only 1 mm per day. While waiting for the nerves to reach the muscles they should control, there’s the risk of atrophy due to inactivity. What Felix was asking the American doctors to do meant waiting for the nerves to regrow the full length of an arm. The likelihood of success was slim.

“I wanted the surgery so bad,” Felix tells me, “but nobody was doing anything of that scale at the time. Hands, sure there is such a short distance that the nerves need to grow, but a whole arm –forget about it. In the two years it would take, there wouldn’t be any muscle left in the hands.” So the American doctors politely brushed him off.

2007

Six years went by. Felix beat his addiction and had his liver replaced. He went about his life, learning to operate a car using his feet, to scratch his face by rubbing it against something, and drink from a

Felix is asked to come to France for further research. By that time, Dubernard was no longer the head of the team: he had retired and been replaced by Dr. Lionel Badet. Felix jumped on a plane for his first visit to Lyon, spending a week in the hospital where, he says: “They checked everything.” The results were promising, and next spring, Felix went for another week to be poked and prodded. By this point, the trips and hospital stays are taking a financial toll. When interviewed about his foot-operated car, the journalist presents a

solution. She would start a charity in his name. “I decided to run 10k in the Reykavík marathon. About 200 people ran with me to raise funds, it was an amazing experience.” While the credit card debt was now paid off, Felix was still waiting for an answer on whether or not the French doctors would perform the operation. “In September, I get an answer: ‘We’re ready to try this.’”

The doctors weren’t promising a miracle cure. They were describing a complicated surgery with a long recovery time and an intense rehabilitation process, for a slim chance of success. “Much like all other doctors, they didn’t know if the operation would work or if the nerves would grow, or if I would be able to do anything with the hands afterwards.” But there was a plan B. “There’s a muscle called the latissimus dorsi, on the sides of your back. When I first lost my arms, I had a stump and the doctors could use part of that muscle in

26 | ICELAND REVIEW

2013

“I look like a person again.”

Special sightseeing taxi tours

www.hreyfill.is

28 | ICELAND REVIEW At your service- Anywhere- Anytime

We specialize in personalized sightseeing day trips to the natural wonders of Iceland – for small groups of 4-8 persons We´ll make you a Comfortable Price offer! To book in advance: tel:+354 588 5522 or on

E-mail: tour@hreyfill.is All major credit cards accepted by the driver. Download the Hreyfill Taxi App The taxi app is FREE and available in iOS and Android. Book a taxi with ease 2013

place of a bicep, so I could move my elbow.” The doctors told Felix that if worst came to worst and the nerves wouldn’t grow, they had the option of repeating that operation on the right so he could at least bend the elbow and give him an option of better prosthetics. “Prosthetics need something to attach to. As it was, I couldn’t really use any.” With that option on the table, to Felix, the gamble was worth it.

For the doctors, one event from Felix’s medical history helped convince them. “An operation of this scale is dangerous and one huge risk factor is that all transplant patients, be it organ or limb replacements, need to take immunosuppressant medication for the rest of their lives. This drug, is, well, it’s poison, really. It keeps your immune system down, making it harder for your body to fight off infections and diseases. But I was already taking them because of my liver transplant.” Putting someone on immunosuppressants for life is not something you do lightly when the chances of success are so slim, but now, that wasn’t an issue. “As much as I felt sorry for myself when I was going through that liver transplant, it turned out to be a blessing in disguise.”

2012

Around Christmas, Felix gets told that in a few months’ time, he might get put on the transplant list. So he moved to Lyon. “The doctors warned me it might be a little premature but I wanted to find a place to live and get settled.” The next autumn, preparations began. “They needed to custom build an operation table and braces, prepare the whole team, and so on. But then everything grinds to a halt due to bureaucracy. “Such a surgery had never been done before, and the French authorities are super strict on regulations and procedures. They needed to rewrite tissue transplant regulations, taking my case into account. Every time they made changes, the institutions have six months to review the data before they approve

organ donor unless they specify otherwise, the same doesn’t apply to limbs. You always need special permission from the loved ones.” Even for Felix, that’s understandable. “The worst day of people’s lives isn’t the time to wrap their heads around something like an operation that’s never been done before. Of course, if you don’t get an organ transplant, you die, it’s a life-saving operation. You can survive without a limb, but your quality of life isn’t the same, and the effect an operation like this can have, there’s no way to describe it. It’s the difference between being alive and having a life.”

The first time he got the call, he was elated. “I thought it was finally happening. Then I got another phone call telling me ‘Sorry, family said no.’ The next time it happened, my hopes were a little more muted. I thought ‘here we go again.’” By this point, it had been 23 years since Felix lost his arms and he’d been living in France for eight years. He’d met his wife Sylwia, they’d gotten married and gotten some dogs, and moved into a small apartment in a renovated 18th-century mansion on the outskirts of Lyon. “The thing about waiting is that time passes, whether you’re waiting for something or not. France is a great place to live and waiting is a lot easier that way, even if it’s always at the back of your mind.”

2021

At 9:00 PM on a January night, Felix gets the long-awaited call again, telling him the hospital would know more the next morning. “And on the morning of January 12, 23 years to the day of my accident, I get the call telling me to get to the hospital and get ready,” Felix tells me. It was happening. “Then on the morning of January 13, a team of 50 people screwed on my new arms.”

2013

them. If it’s not completely accurate, you need to go through the same process again and wait another six months.” In the autumn of 2016, all i’s dotted and t’s crossed, Felix was put on the transplant list. Now the waiting begins.

2016

“I’m waiting for a phone call around the clock, always careful to keep my phone on me. I don’t take a vacation or travel too far from Lyon.” This is the case year-round except for six weeks in summer, when Felix is taken off the transplant list so his team of doctors can take a vacation. Then he gets a call. “At least three times, I got the call that they’d found a match. But in France, while everyone’s an

It was a 15-hour operation. And just like he had been promised and prepared for, that was only the start of it. “I’ve gained so much already and feel thankful every day but my God, it’s been hard. When I got my liver transplant, I was very sick. But as soon as I got the transplant, I felt so much better. This time, the surgery was just the beginning.” The pain is greater than he had imagined. “The first seven months were almost unbearable. The doctors connected nerves and veins, muscles, tendons, and skin. And this is all hanging from your sutures. Then when the nerves start to grow, they’re inside some sheaths. And that hurts like a m*****f****r because as they grow, they rub up against the walls.”

The doctors cautiously estimated that the nerves could take up to two years to regrow. In nine months, however, Felix could feel his hands. “We’re seeing much better results than people were even hoping for. They were keeping their expectations low, of course, making sure I didn’t have sky-high hopes. But the success is incredible.”

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 29

Felix is careful not to take the credit for everything on his journey, praising and thanking all the people who helped him and cared for him along the way. “I owe them so much, this isn’t something you do on your own.” His mother moved to France with him to take care of him, his wife and his father have shown immense support. “I’m so lucky in my friends and family. No matter how crazy my dreams were, they were with me all the way. Now that I can do more, my mom doesn’t need to take care of me as much. My father died this January, and they lived apart for 8 years because of this. But before he passed away, he saw me get my arms.” He also shares his success now with others. “I’ve been receiving message from all over the world, from every continent. From people who have lost limbs, or have loved ones who’ve lost limbs. All of a sudden, there’s hope. And that’s incredible to me, because I know what hope can do. All I had was one tiny note from a doctor who didn’t say no and that kept me going for years.”

2022

So how have new arms changed Felix’s life? “What you don’t realise is that when you lose your hands, you don’t touch anything and no one touches you. It’s like you’re living in a bubble.” Parent to an infant and a toddler at the time of his accident, hugging his children is what he missed the most. “All of a sudden, all that was gone. You just stand there and can’t do anything. And being able to touch things, hug my children and grandchildren again, this is just…” Felix trails off.

Then there’s his independence in everyday life. “I can take care of my own hygiene, brush my teeth, and go to the bathroom on my own. I can dress and undress myself, take a drink from a glass without a straw. I can eat with a fork or a spoon. When you’ve had to rely on other people for every little for years, these small things aren’t so small.” Finally, it’s a matter of self image. “I look like a person again. I can move my hands when I talk. I can scratch if I feel an itch. I can wear a watch!” Felix now enjoys using a smartphone without having to operate it with the tip of his nose or his tongue, making it very difficult to see the screen. “I can use things that are a matter of course and normal to most people, that up until a few months ago, I wasn’t sure I would ever be able to again.”

NOW

While he’s had remarkable success, there’s still a long way to go. “There are so many muscles in a hand that we never give much thought. Bending a finger takes one set of muscles but straightening it again means using a whole another set. At this point, I can’t straighten my fingers unless I push on the other side to support the muscle in the wrist.” Every week, Felix discovers new things he can do. “I held my dogs, that’s the most recent thing. I can clean the house: I put on a washcloth and pick up a brush and clean the house like a whirlwind. I tried drinking from a glass for the first time at the airport on my way here. When you haven’t been able to do it for years, it’s very different. Most people don’t think about scratching when they have an itch. You don’t know how many times you’ve scratched your face today. But not being able to do it and then being able to do it again, there’s nothing like it.”

My mind is still stuck on all the waiting. I ask Felix what he would have done if he had known how long the whole process would take. He answers without hesitation: “Just what I did when the accident happened, dive head first into addiction. We all learn as we grow older, but I had to learn a lot faster. Either I stopped feeling sorry for myself and shoulder some responsibility or I was staring into the bottom of a coffin.” When Felix was at the point when he needed a new liver, he’d been, in his own words, wallowing in self-pity for about three years. “I wasn’t really suffering from the results of the accident anymore, I was suffering because I didn’t want to come to terms with what had happened to me. All my misery was self-made. When I realised that, I also realised that I could change it. I could do plenty of things but I was laser focused on the things I couldn’t do. Life is easier this way. You see so much clearer. I didn’t want to get a liver transplant but if I hadn’t, I wouldn’t have arms.”

As I say goodbye to Felix and walk out into the sunlight, I lift my hand to block the glare, then catch myself absent-midedly scratching my nose as I walk down the street.

“What you don’t realise is that when you lose your hands, you don’t touch anything and no one touches you. It’s like you’re living in a bubble.”

30 | ICELAND REVIEW

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 31 LIVE MUSIC EVERY NIGHT HAPPY HOUR 4-7PM EVERY DAY Ingólfsstræti 3, 101 Reykjavík | Tel: 552-0070 | danski.is IcelandReview_182x120_DenDanskeKro.indd 1 5/7/2019 5:40:40 PM

LOVE,

WORDS BY RAGNAR TÓMAS HALLGRÍMSSON PHOTOGRAPHY BY GOLLI

BRÍET ON THE POWER OF MUSIC

THE BUS RIDE

For the first time in what felt like a long time, I was free. No obligation to stay inside, to put the kids to bed, to return home before some vaguely appointed hour – for it was understood that I was working, and I could not be held accountable for that work coinciding with an evening associated with good spirit and debauchery: it was Culture Night, and I was a man of culture.

But as more and more people piled onto the bus, I found that my excitement was supplanted by a sense of ruefulness. I felt low. Put off. Disinterested. And the thought arose that “none of it meant anything without her.” To be clear, this ruefulness was not the product of some unprovoked shift in brain chemistry but derived from the music in my ears; Bríet, a composer, chiefly of love songs, had two years ago released an album dedicated to the emotion of love (Kveðja, Bríet), which was now playing in my headphones

I had never listened to the album in its entirety and had not realised that all of it was dedicated, or so it seemed, to a single person, a single relationship – a single Daedalian feeling; for 36 minutes and 21 seconds, Bríet walks into that “subtlest maze of all” (i.e. love) and explores all the pathways and passages and high hedges and looming minotaurs, transporting the receptive listener alongside her – whose world then becomes the maze. And so it was that in spite of the fine weather and people and licence and anticipation, I felt incomplete. Destitute. Alone.

As the bus wound its way through the labyrinth of the city, I lost myself in that other maze and began to think my way through a recent epiphany, namely that music existed as an antithesis of stoicism: a philosophy availing itself of the insight that cognition is an integral component of emotion, and that by reframing strong and unwanted feelings, a person may succeed in mitigating them. By contrast, music – sitting at the opposite end of this peculiar spectrum – had the power to strengthen subdued but desired emotions.

And as I thought all of this, I began to feel that Bríet’s kind, for lack of a better word, must rank among humanity’s greatest benefactors. Moved by this feeling, I resolved to call my soon-to-be-wife and persuade her to accept her mother’s offer to babysit tonight. Because without her, none of it meant anything.

LAILA’S DAUGHTER

I first heard of Bríet in early 2017.

Her mother, who shared an office with me on Laugavegur, told me that her elder daughter was releasing her debut single. Gearing up for some polite insincerity, I smiled and feigned interest and, to my surprise – discovered that Laila’s daughter really could sing: that there was some there there

In the coming months, I interviewed Bríet a handful of times; stood in the audience as she performed live; and watched, alongside the rest of the country, as she won over an increasingly larger audience. This brought awards and record deals and a burgeoning sense of local celebrity, but through it all, she seemed warm and personable and never quite so down to earth as when she sat cross-legged in her mother’s sweat lodge in East Iceland and serenaded all the sweaty, overworked souls that had gathered there in the steaming tent.

And then I met her again that morning, before my bus ride.

Bríet was scheduled to soundcheck at Culture Night’s “big stage” (the one sponsored by national broadcaster RÚV) in front of Arnarhóll hill at 12:30 PM. Magnús Jóhann, one of Iceland’s most ubiquitous young session players, was sitting at his keyboard on the far side of the stage and killing time as the sound crew lugged equipment and electrical cords.

“Yes, speaking of Bríet,” Magnús remarked, “I don’t know… wait, what time is it?” He glanced down at his phone. “Yes, our soundcheck began two minutes ago.”

Fifteen minutes later, Bríet arrived with her agent, Soffía, who explained that they had walked almost all the way from the University of Iceland because the streets were closed for the day’s celebrations. Bríet, relaxed and in good cheer, hugged her fellow musicians and sauntered onto the stage.

She began by expressing frustration that a requested “side stage” had yet to be erected. Turning to Soffía, she asked: “Is this the smallest stage in the world? Who’s trying to save money here?”

Last year, Bríet booked the Eldborg auditorium at the Harpa Concert Hall – one of the grandest stages in the country – and put on, according to those who attended, a series of the most spectacular shows in Icelandic music: rumour has it that she made almost no money from the concert, preferring to recycle any foreseeable profit back into the spectacle itself.

As preparations continued and various people buzzed

“Is this the smallest stage in the world? Who’s trying to save money here?”

34 | ICELAND REVIEW

about the stage, Bríet – wearing jeans, thick-soled white sneakers, and a colourful sweater reminiscent of Biggie’s famous Coogi – leaned momentarily on her right leg, shifted her weight, and looked down at her feet. Her short, bleached curls protruded mane-like from beneath her bespoke black cap and her left hand dangled – like she was a hippie floating on a cloud of marijuana.

It was almost 1:30 PM by the time she actually started sound checking. I had taken my place at the bottom of the hill across from the stage and listened as she performed Fimm, a popular single from Kveðja, Bríet. Bystanders, their hair blowing in the cool wind, stopped to look on, some of them mistakenly believing that she was about to perform.

“I’d like a lot of reverb on the vocals. That’s like my input for you,” she said to the sound engineer across the stage. I wondered if she had changed.

FÁLKAGATA

Standing in a backyard on Fálkagata, I speculated which of the three doors led to Bríet’s apartment. I walked back and forth and tried peering through the windows – when the door

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 35

farthest from the street popped open, and a black-and-white collie came running toward the low picket fence. A man in a green Adidas hoodie followed suit.

“Does Bríet live here?” I asked, petting the collie on its head.

I knocked on Bríet’s door, and a voice called for me to “come inside.” The apartment was bohemian and snug, filled with flowers and knick-knacks, and an old blues record was spinning in the background. Rubin Pollock – guitarist of the Grammy-nominated band Kaleo and Bríet’s boyfriend – stood up from the sofa, introduced himself, and shook my hand. Bríet, who was sitting at the kitchen table getting her hair done, got up and gave me a hug. Her three colleagues – a makeup artist, a stylist, and a designer – said hello.

I told Bríet and Rubin that I had met their neighbour and that he had nothing but kind words, and they said that his name was Andri and that he was “great.” I suggested to Bríet a “quick chat now” before sitting down again somewhere more private next week. She replied that that “sounded fine” although it would be fun to talk now since so many of her

trusted colleagues were there. “That way all of us could talk,” she explained.

“OK, I’m outta here,” Ísak, the make-up artist, declared from the sofa, as everyone laughed.

Whatever suspicion I had harboured that Bríet's humility had been compromised by her success was quickly dispelled. It occurred to me that any gap between Bríet-then and Bríet-now was not a matter of personal devolution in the direction of haughtiness or entitlement but rather the formation of two separate identities, disparate but seemingly non-overlapping: the person and the persona. This insight owed not only to Bríet’s warm demeanour but also to my own experience as a musician, where the disparity of an exaggerated stage persona, whose charms would linger before and after performances (while I was still drunk), would serve to underscore the inadequacies of my private self in more quotidian contexts – and cause me not a small amount of mental anguish.

Bríet still visits her mother’s sweat lodge in the east as often as possible, and Laila continues to employ the

36 | ICELAND REVIEW

“I have more hands, more minds, more eyes, which is priceless – for there’s only so much you can do alone.”

same innocent subterfuge whenever her daughter’s there. Addressing the participants, Laila will say, “Now, I haven’t asked my daughter to sing,” and then, turning to Bríet, “but suppose you’d indulge us?”

I ask Bríet how her day began, and she redirects the question to Rubin.

“I prepared some oatmeal and tuna toast and made you eat,” he remarks.

“I have this tendency not to eat before shows,” Bríet explains, suggesting somehow the inequitable demands of women artists in music. “Which never fails to inspire this feeling of responsibility within Rubin; he wouldn’t let me leave the house without eating.”

The preparations for tonight’s big show have proved less than ideal. RÚV requested that Bríet close the evening by putting on a similar show as the one in Harpa, and Bríet agreed. But then that venerable institution’s organisers proceeded to veto all of her ideas. She had suggested, for example, beginning her performance with a theatrical entrance from the top of Arnarhóll: walking down through

the throng of people while singing. But that, the organisers replied – though not in so many words – was “too much of a hassle.”

“They weren’t trying to find any solutions,” Bríet explains while sipping her tea. “So I’ve been a little annoyed going into it. When I showed up today, and they hadn’t erected the side stage, I was frustrated; I just struggle when I’m asked to do something and then no one’s prepared to do the work.”

“Has anything changed since the start of your career?”

“No, I wouldn’t say so,” Bríet remarks. “The crowd’s gotten bigger, and there are more people around me. I have more hands, more minds, more eyes, which is priceless – for there’s only so much you can do alone. But I, sort of, know more … what I want. And where I’m going. The path is always becoming clearer. I can do new things, bigger things …”

“So you have a clearer vision and the courage to pursue that vision?”

“Well…” Bríet pauses, before saying rather emphatically: “No: I’ve always had a clear vision and the courage to follow through, but what’s changed is that people have begun to take

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 37

“I’ve always had a clear vision and the courage to follow through, but what’s changed is that people have begun to take me seriously.”

38 | ICELAND REVIEW

me seriously.” She chuckles. “‘Yes, perhaps you do know what you’re doing,’” Bríet remarks, imitating the once-sceptical members of her industry.

“You’re still sober?”

“Yes, not a sip of alcohol to this day.”

Her mother’s sobriety has probably played a part, although Bríet clarifies that alcohol has never really appealed to her.

“All that interests me is that which serves to broaden my horizons – and I don’t think there are many things that can do that besides oneself. But I don’t know. I’m not saying ‘never,’ either, just that other things offer so much. Like going to sweat ceremonies – and being on stage. That’s probably my way of getting high.”

We talk music briefly before segueing into writing. At last year’s Iceland Music Awards, Bríet was chosen Best Lyricist. In a somewhat controversial moment, while accepting the award, she turned to the camera, put up a middle finger, and declared: “That’s for everyone who asked me ‘Who writes your lyrics?’”

“Do you read a lot?”

“My friend does – and she offers plenty of recommendations. I just read Where the Crawdads Sing. It’s so good. Every word is just perfect. I’m currently reading Sápufuglinn and The Power of Now. But I don’t read much. I like to talk. That’s how I write.”

Bríet keeps a diary and often allows her consciousness to

stream through the typewriter. But there’s no fixed regimen. “It’s more when it comes to me,” she says. “Or when I have time. I usually don’t write a lot. Just a matter of jotting down emotions. And then when I’m in the studio, I’ll read it over and find some fragments that I like. I’ll discuss them with Pálmi, my producer, who’s very good at picking out good ideas.”

“Are you working on a new record?”

“Hmmmm… yes… well, I think so… just that – I don’t have anything to say.”

“What do you mean by that – that you don’t have anything to say?”

“There’s just no one overarching feeling. Which means that there’s no focus. I don’t have anything to say because I’m all over the place. It’s just this hodgepodge of songs. But I don’t know… we’ll have to wait and see…”

“So you’ve got songs?”

“No, not really. I’ve just been performing so much. Whenever I’m in the studio – I just fall asleep.”

“Does the thought of following Kveðja, Bríet strike you as overwhelming?”

“No, more that I’d like to write in English, but transitioning is hard. Because it’s hard to think in English when you’ve been thinking in Icelandic your whole life. My first songs were written in English, but everything is somehow a little less personal.”

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 39

40 | ICELAND REVIEW

THREADS

Walking down Fálkagata, struggling against the wind, I button up my coat and make that phone call that I had resolved to make. Speaking sincerely and sentimentally – I successfully coax my fiancée into joining me downtown.

The evening is a whirling carousel of people and music and vivid impressions. When Bríet finally takes the stage at just past 10:00 PM, we stand midway up the hill on Arnarhóll, agreeing that her entrance would have been greatly improved if she had gotten her way: if she had been allowed to descend from the statue of the old Viking through that impressive throng, like a vast colony of ants, gathered there on the hill. The concert is enjoyable and wellreceived and befitting the moment – but nonetheless, we imagine, still a far cry from her show in Harpa.

As the show slowly winds down, we –not wanting to get caught in the crowd – leave for our car before the fireworks begin, and I’m left with the impression that the evening would have meant so much less had I not listened to Bríet’s album on the bus ride to town; engaging with some emotionally abortive podcast, I would have convinced myself that my fiancée’s reluctance to join me for a concert downtown was understandable and advisable and probably more conducive to my getting work done.

Life is a maze, filled with dead-ends and anxieties and quotidian worry, which dull the senses and distract from what’s important. But there are threads lying unnoticed among its passageways. Woven together by the great benefactors of mankind.

“Because without her, none of it meant anything.”

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 41

HOME COOK

A voyage into Gísli Matthías Auðunsson’s taste of Heimaey

Words by Gréta Sigríður Einarsdóttir Photography by Golli

Up. Down. Up again. A fleeting moment of calm at the highest point. Down again, tourists whooping as the boat rolls in the waves. I, on the other hand, wasn’t enjoying that lurching feeling in my stomach as the boat dipped with the green-tinged waters. My face was turning a similar hue, and even when we reached solid ground, it took me a moment to recover. The ground in question is part of Heimaey, the largest island of the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago just off Iceland’s south coast, and I was here to talk about food.

The ferry ride is only about half an hour on most days and is generally a perfectly pleasant experience. Even the rough weather this morning hadn’t deterred a full boat of day trippers on their way to visit the islands, see the puffins, hear about the 1973 eruption, and, most importantly, taste the food. Vestmannaeyjar have been lauded as the country’s most exciting culinary destination outside the Reykjavík city centre, even though the volcanic island isn’t home to any agriculture. The islands are home to a high percentage of fishermen, though, and a chef called Gísli Matthías Auðunsson.

A FAMILY AFFAIR

“It’s way too big, I don’t know what we were thinking,” Gísli tells me as we look over the dining hall of Slippurinn, the popular restaurant he runs with his parents and his sister. This year marks the tenth anniversary of the spacious eatery. “It was really my mother’s dream, to start a restaurant in this building. She always thought the

building looked so grand and that it was sad it wasn’t in use,” Gísli explains as we look around the workshop-turned-industrial-chic restaurant. A family gathering turned into a business meeting and overnight, the family became restaurateurs, with Slippurinn opening its doors for the first time less than a year later. “We didn’t really have any capital to speak of and no investors. Each nail and every pipe were hammered and laid by my dad Auðunn and my sister Indíana. She has a master’s degree in visual art, as well as being a carpenter. He’s a jack of all trades, having spent more than 50 years at sea. My mother, Kata, had worked in restaurants before but I was just graduating as a chef.”

On the occasion of the place’s tenth anniversary, Gísli discovered a social media post he wrote on opening the restaurant. Despite all the changes, the ups and the downs, he was surprised at how well the original concept held up. “We wanted to make the locals proud, celebrate ingredients from around here, fully utilise our resources and work with the local flora. From day one, we’ve been using herbs and kelp from the island, and berries, when they’re in season.” His mom still grows the herbs they can’t pick wild in pots on her windowsill. The only thing that has changed, according to Gísli, is that each year, they try to do what they do a little bit better.

“

WE SERVE COD SKIN AS SNACKS. THE COD SKIN IS SALTED, DRIED, AND POPPED, SPRINKLED WITH ANGELICA.”

“

WE SERVE COD SKIN AS SNACKS. THE COD SKIN IS SALTED, DRIED, AND POPPED, SPRINKLED WITH ANGELICA.”

44 | ICELAND REVIEW

AMATEUR BOTANY

Slippurinn is very much a Vestmannaeyjar restaurant in the sense that the food they make couldn’t be made anywhere else. It’s only open during the summer season, when the chefs can rely on the fresh bounty of plants growing on the island. Even on a rainy afternoon, the island’s bounty looks luscious, green plants providing a striking contrast to the black sand from the 1973 eruption. “The feeling I want people to leave with is that this is the only place in the world where they can taste exactly this kind of food. We won’t offer a filet mignon with truffles and caviar, we don’t see that as unique.” Instead, Slippurinn focuses on seeing the value of the ingredients that are underutilised. “To me, that’s a real luxury,” Gísli says. “By now, we use over 80 herbs and plants from the islands in the kitchen and the food we make has developed based on the ingredients available.”

When they started out, Gísli really didn’t know too much about herbs. “Mostly we were using angelica, sorrel, and arctic thyme when it was in season. Maybe crowberries in the fall.” For the past decade, Gísli and his team of chefs have studied the plants that grow on the island, tasting them and figuring out which ones they can use. Take angelica, for example. “Early in the season, you can only use its leaves. As it grows, the stalks can be used, pickled and so forth. When the seeds appear, we gather those and make a sort of version of capers, use it for tea, and more. By the end of the

season, the root becomes, edible but at that point, the stalks have become too woody.” Gísli doesn’t claim to know every plant on the island. “But we’ve learned a lot. And we’ve had help, we’ve had botanists with us, and an expert in kelp. So we try to gather more knowledge as we go along.”

GOING LOCAL

This kind of cooking is relatively new to Iceland, no doubt spurred on by advances in new Nordic cuisine. Older cooking traditions were victims of the rapid urbanisation of the 20th century and much of the old ways of using nature’s resources were lost. “I think Icelanders are only just beginning to scratch the surface of what we could be doing. Restaurants could take another look around and find the value in things that others don’t see. There was a massive awakening when NOMA started, with their new Nordic cuisine. We’re influenced by that, 100%, and people, not only restaurateurs but also customers now see value in local cuisine. People are realising just how huge a part food is of each country’s culture and history.”

PARADISE LOST

Gísli has done his part to raise awareness of traditional cooking methods. “When I was involved in [Reykjavík restaurant] Matur og drykkur, we went deep in discovering old references to lost cooking

ISSUE 05 – 2022 | 45