Soledad Sevilla: Rhythms, Grids, Variables is the title of the exhibition the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía has dedicated to Soledad Sevilla (Valencia, 1944), the winner of the 2020 Velázquez Prize for the Plastic Arts and one of the most firmly established creative voices in contemporary Spain.

The retrospective draws us into an oeuvre that spans six decades, highlighting the connections between her different phases as an artist.

A poetic element has consistently played a key role in the work of Soledad Sevilla. Hers is a poetics of subtlety, shot through with the work of other artists, ranging from great masters of baroque painting like Velázquez and Rubens to twentieth-century artists like Mark Rothko, Agnes Martin, or her friend Eusebio Sempere. This comprehensive review of Sevilla’s creative journey invites us to plunge into the most audacious and experimental facets of an oeuvre that employs abstraction to give visual form to a unique conception of everyday reality.

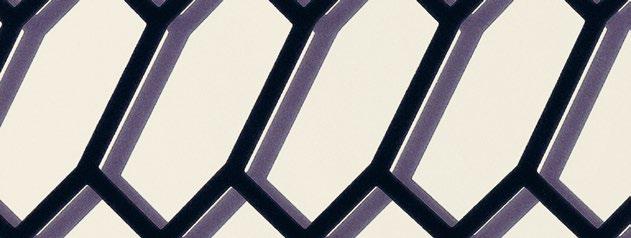

Geometry and the repetition of visual patterns form the foundation of an artistic language increasingly centered on the use of reticular

grids and the search for a certain vibratory effect. Sevilla’s residence in Boston in the early 1980s marked a watershed in her career. It was then she designed her first installation projects, which foreshadow the emotional dimension of her later work.

In her most recent work, an architectural sensitivity is combined with a beautiful approach to nature and a reflection on time that leads into minutely precise and hypnotic series, shown to the public for the first time in this retrospective.

The exhibition is complemented by this catalogue, with essays by Paula Barreiro, Yolanda Romero, Antonio Cayuelas, and Isabel Tejeda, the show’s curator, that explore different aspects of the artist and her work. We also extend our gratitude for these valuable contributions to the team at the Museo Reina Sofía in collaboration with that of the Comunidad de Madrid, for enabling such a complete, rigorous survey of the magnificent oeuvre of Soledad Sevilla.

Ernest Urtasun Domènech Minister of Culture

Soledad Sevilla: Rhythms, Grids, Variables , the exhibition devoted to the artist Soledad Sevilla, brings us closer to the universe of one of the most interesting figures in the history of recent art. We are speaking of one of the leading representatives of geometric abstraction in Spain and one of the most internationally reputed Spanish artists. From geometry to light, her work, always highly personal, seeks poetry in a beauty that has conceptual roots.

Curated by Isabel Tejeda, the show surveys Sevilla’s artistic universe from the 1960s onward, with works linked to the Universidad de Madrid’s celebrated Centro de Cálculo (Computing Center), to her most recent production, where she pays tribute to her friend and fellow artist Eusebio Sempere.

The 1960s saw essential changes brought about by, among other things, new technologies. To process those changes, centers devoted to investigating the dialogue between technology, art, and science took on great importance. In Spain, it was in this context

that the Universidad de Madrid’s Centro de Cálculo was founded. In Soledad Sevilla’s case, it proved fundamental. Thanks to the use of the computer, she fashioned the voice that would henceforth accompany her. Not content with this, she took this voice to the United States in a process of spatial and aesthetic investigation that continues today.

This exhibition reflects the interest of the Comunidad de Madrid in disseminating and celebrating the work of great contemporary artists.

We wish to thank the artist for her investigative work, her tireless labor, and her unflagging commitment to painting, and also the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía for its dedicated, rigorous efforts to ensure visibility for the most suggestive and personal artists of our time.

Isabel Díaz Ayuso President of the Comunidad de Madrid

The exhibition Soledad Sevilla: Rhythms, Grids, Variables presents a chronological survey of the career of Soledad Sevilla, a prolific and heterodox artist whose work is sustained by a concept of art uniting judgment and emotion, reason and sensibility. The show highlights how Sevilla’s work, which springs from a lyrical understanding of formal experimentation, is deeply concerned with beauty and intuition, and how it vindicates the ability of aesthetic creation to confront us with “liminality and the inapprehensible,” to shake us and transport us to a “threshold” where time remains suspended for an instant and our relationship with reality is transformed. Through a selection of over a hundred works, the exhibition shows the coherence and circularity of the artist’s evolution, something she herself points to when she states she has been painting the same picture all her life. This assertion requires qualifi cation, as the curator of the exhibition, Isabel Tejeda, points out, since her work should be viewed as a continual toing and fro-ing, a tireless refl ection on the same questions in a “Heraclitean” sense, that is, as if returning to a permanently fl owing river. This idea is explored in Yolanda Romero’s essay, which suggests that Sevilla’s career can be read as a “vast universe governed by the principle of change, where one event already includes the beginning of the next” in a constant mutation that has allowed her to “transit freely from the geometric to the expressive, from the permanent to the ephemeral, from light to darkness, and from reason to emotion,” remaining on the margins of dominant, sometimes stagnant, trends.

Soledad Sevilla began her career in the mid-1960s, a time when the Spanish art scene was opening up to geometry. As Paula Barreiro explains in her essay, the artist then started to define her artistic language, concentrating on “rational experimentation with form by means of geometric abstraction.” Her involvement with the Universidad de Madrid’s Centro de Cálculo (Computing Center) allowed her to pursue research on the principles of combinatorics, seriality, and the module, fundamental for her later work.

Although she always kept up ties with the heterogeneous group of geometric artists, Sevilla soon set aside the use of the computer as an artistic tool because it did not allow her to develop the type of investigation of geometry that interested her. From the end of the 1970s, this investigation led her, in Barreiro’s words, to the “breaking of the bounds of the plane by the line and its interaction with space.” In this respect, her residency in Boston between 1980 and 1982 proved a crucial experience, as it was there that she conceived her first projects that hinged on spatial intervention and contained performative connotations. Those projects anticipated her later incursion into the installation format, such as MIT Line and, especially, Seven Days of Solitude, where she first introduced the processual, memory, and the cultural specificity of place to her work.

In Boston, she also produced pictorial series such as Keiko and Belmont, in which she imbued her pictures with an atmospheric and vibratory quality that was to be one of the principal hallmarks of her mature work. They are the direct precedent of two of her most emblematic projects of the mid-1980s: Meninas, in which

she focuses her investigation on how space is configured through an immaterial element like light, and Alhambras, articulated, as the artist herself explains, around three themes born of her “contemplating the world of the Alhambra: the magic of portals, the magic of reflections, and the magic of shadows.”

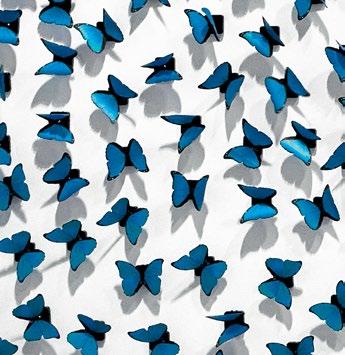

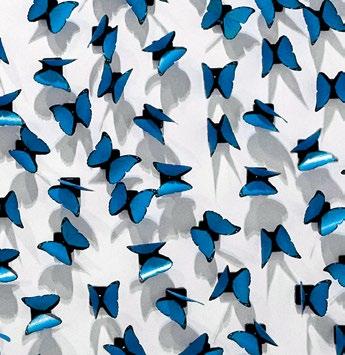

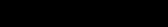

These two series put the seal on the growing importance that Sevilla had started to attach in her work to poetics and the installation. Indeed, this exhibition includes a re-creation of El tiempo vuela (Time Flies), in which a thousand paper butterflies revolve unceasingly in a suggestive metaphor for the inexorable passage of time and the fleetingness of life, and Donde estaba la línea (Where the Line Was), conceived by the artist specifically for this show. In it Sevilla carries out an intervention in the Museum’s Sabatini Building with cotton threads, a material she has used in earlier installations like Fons et Origo and Toda la torre (All the Tower), whose choice, as Isabel Tejeda emphasizes, is informed by an “underlying gender reading.”

Soledad Sevilla’s installations have sometimes constituted the starting point for a new pictorial cycle, as is the case of En ruinas (In Ruins), which originated in Mayo 1904–1922, produced at the Vélez Blanco Castle, in Almería. This fully abstract series reflects the influence of Mark Rothko on her oeuvre and anticipates the interest in landscape and nature that was to mark her work from the late 1990s onward. Such interest also surfaces in works like Apamea and Insomnios (Insomnias), as well as in more recent

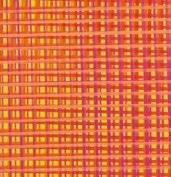

projects such as the sculptures Arquitecturas agrícolas (Agricultural Architectures) or the series Nuevas lejanías (New Distances) and Luces de invierno (Winter Lights), where she paints the diffuse landscapes seen through the transparent plastic sheeting of the tobacco drying sheds on the fertile plains of Granada.

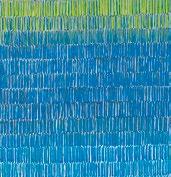

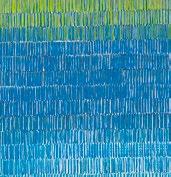

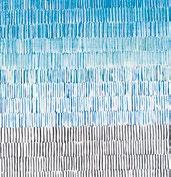

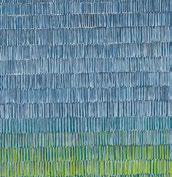

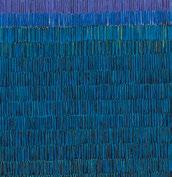

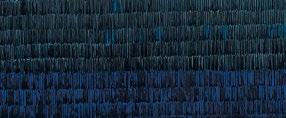

Along this path of to-ing and fro-ing, Soledad Sevilla’s current production reviews some of the artistic concerns of the beginning of her career. This process of revisiting has led to a reencounter with Eusebio Sempere, an artist she has always greatly admired and with whom she maintained a close friendship ever since first meeting him in 1967. She pays homage to Sempere in this exhibition with a small gouache by the artist belonging to her personal collection, which has given rise to her most recent series, Horizontes (Horizons), Horizontes blancos (White Horizons), and Esperando a Sempere (Waiting for Sempere), revealed to the public for the first time in this exhibition.

The exhaustive survey of Soledad Sevilla’s career offered by this retrospective shows how the artist has constructed a hybrid oeuvre punctuated by continuous transformations but at the same time characterized by an unequivocal internal unity. The exhibition furthermore demonstrates that in her quest to generate “an experience of the liminal” and incorporate a poetic drive in her practice without renouncing experimental rigor, Sevilla has traced a path of her own, making her a fundamental figure in the Spanish artistic landscape of recent decades.

Manuel Segade Director of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Invading and Extending to Infinity: Soledad Sevilla and the Other Side of the Line

Paula Barreiro López

A Book without Words

Yolanda Romero Gómez

A Conversation with Soledad Sevilla Kevin Power

Mediating between Emotion and Judgment: Soledad Sevilla

Isabel Tejeda Martín 118

Threads of Light: A Studio for Soledad Sevilla

Antonio Cayuelas Porras

List of Works

The direct message has never interested me. I want a little more subtlety, arriving at things in a different way. 1

—Soledad Sevilla

After nearly a decade of informalist existential introspection, the 1960s unveiled a new interest in geometry in Spain. Scientific processes, industrial materials, and the study of the phenomena of perception fostered and were associated with a break with the traditional models of artistic reception through the activation of the viewer. While realism and new figuration continued their ascent, a new generation of artists explored the intersections between geometric abstraction, visual perception, and mathematics. This path was aligned with the international revaluation and recognition that was being won by optical-kinetic abstraction through exhibitions like The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York (1965), distinctions like the awarding of the grand prizes to Victor Vasarely at the São Paulo Biennial (1965) and to Julio Le Parc at the Venice Biennale (1966), and the creation of new sites dedicated to the interconnections between art, science, and cybernetics, such as the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1967.

It was at that point that the Valencian Soledad Sevilla finished her art studies at the Sant Jordi Academy of Fine Arts in Barcelona (1964) and moved to Madrid. She rapidly concentrated on rational experimentation with form by means of geometric abstraction. In the late 1960s, Sevilla defined a project of analysis and introspection in which the line became a fundamental element of her work.

2 For an overview of the geometric abstraction movement in Spain in the second half of the 1960s and its precursors, see Paula Barreiro López, La abstracción geométrica en España (Madrid: CSIC, 2009).

3 Soledad Sevilla, untitled, in Sempere. Soledad Sevilla. Líneas paralelas, exh. cat. (Madrid: Fernández-Braso Galería de Arte, 2019), 24.

4 Sevilla, interview.

5

Esteban García Bravo and Jorge A. García, “Yturralde: Impossible Figure Generator,” Leonardo 48, no. 4 (2015): 368.

6 See Enrique Castaños Alés, Los orígenes del arte cibernético en España. El Seminario de Generación Automática de Formas Plásticas (Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2000), 187–90.

The presence of Soledad Sevilla in Madrid in the mid-1960s, a consequence of her marriage to the architect José Miguel de Prada Poole, allowed her gradually to join an artistic scene that was opening up once more to geometry. Exhibitions like Op Art at the Galería Edurne (1966), the Salones de corrientes constructivas (Salons of Constructive Trends, 1966), and Arte objetivo (Objective Art, 1967) revealed the existence of a new interest spurred on by the work of young artists like José María Yturralde, Elena Asins, Julián Gil, Lugán, and Julio Plaza.2 Sevilla shared projects and exhibitions with them while facing the difficulties of combining an artistic career with raising her two children in a clearly patriarchal context.

It was between 1968 and 1969, while she was holding her first solo exhibitions at the Galería Trilce in Barcelona and the Galería Juana Aizpuru in Seville, that she started to collaborate with some of the networked movements that were seeking to integrate scientific processes into artistic practices, such as Antes del Arte in Valencia and the Seminario de Generación Automática de Formas Plásticas (Seminar for the Automatic Generation of Plastic Forms, SGAFP) at the Centro de Cálculo (Computing Center) of the Universidad de Madrid. Feeling that in Spain there was a lack of “a body of thought, an intellectual corpus” for artists, she found that the Seminar situated her in an inspiring context of comradeship and reflection. 3 “Mentally,”

Sevilla explains, “I fitted in very well with a type of discourse that interested me more than another—which didn’t interest me at that stage—of copying nude ladies and doing landscapes.” 4 Moreover, this experience allowed her to join a network of established figures, like Eusebio Sempere, and young artists, like Jordi Teixidor, José Luis Alexanco, Manolo Quejido, and the aforementioned Yturralde and Asins.

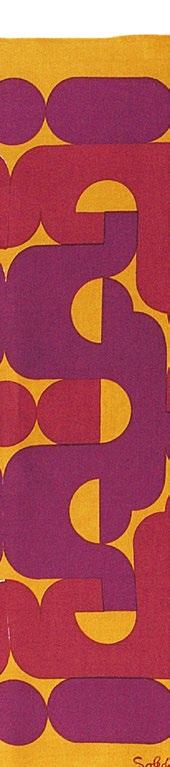

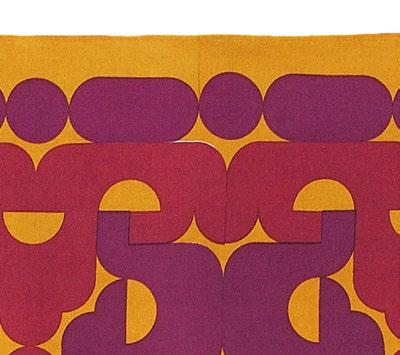

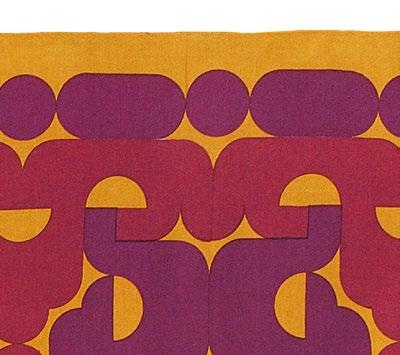

One of the principal objectives of the Seminar at the Centro de Cálculo was to use the computer to assist in the production of artworks. Thanks to an IBM computer, algorithms were created to generate works that were printed on a continuous roll of paper. 5 Nevertheless, the translation of the work into binary code in fact went beyond the use of the computer itself and laid the scientific foundations for the creation of artworks based on geometric structuralist orders, the binary use of color, and the superimposition of modular forms, as Soledad Sevilla’s work demonstrates. Her artistic production, based on the principles of combinatorial analysis, was directly related to her participation in the SGAFP, and she viewed her works as fully-fledged objects of research. 6

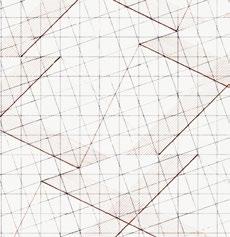

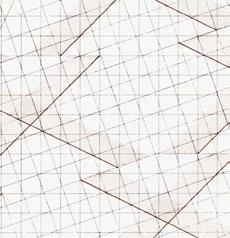

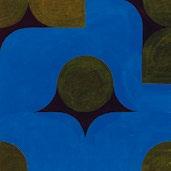

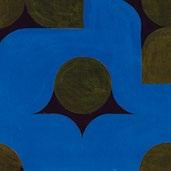

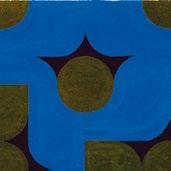

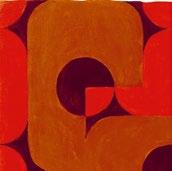

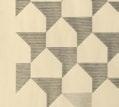

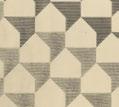

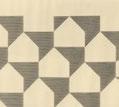

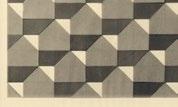

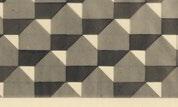

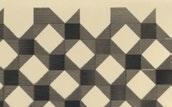

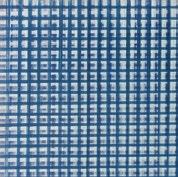

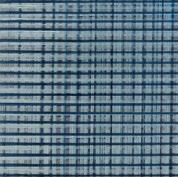

The module was one of the possibilities most frequently explored by the artists in the Seminar owing to its ease of systematization and computerization. The artist would establish a set of rules that would govern the creation of form in the work. Sevilla started with a single module that she rotated and upon which she superimposed others, creating axes of symmetry. Unlike one of her colleagues,

7 José Miguel de Prada and Soledad Sevilla, “Texto para el catálogo Generación automática de formas plásticas” (1970), reproduced in Carmen González de Castro, Yolanda Romero, and Soledad Sevilla, Soledad Sevilla. Transcurso de una obra, exh. cat. (Granada: Instituto de América de Santa Fe, 2008), 125.

9

Sevilla, interview.

10 See Naomi Oreskes and John Krige, Science and Technology in the Global Cold War (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014).

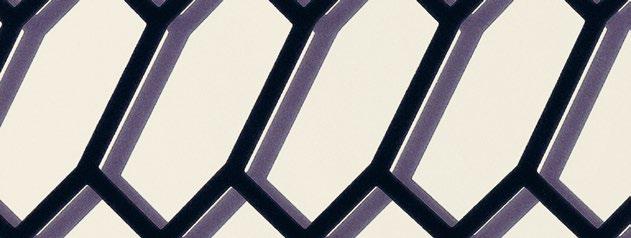

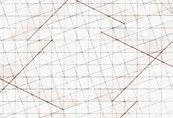

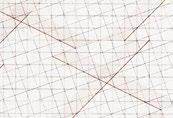

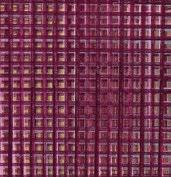

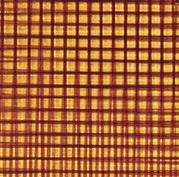

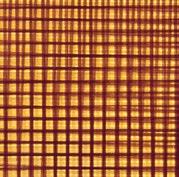

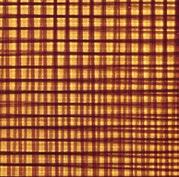

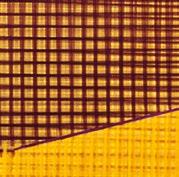

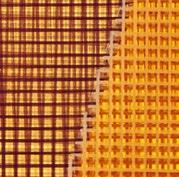

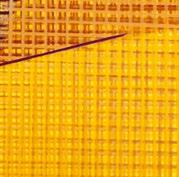

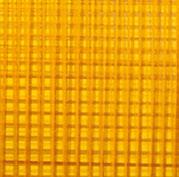

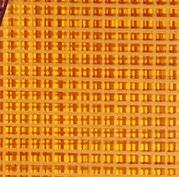

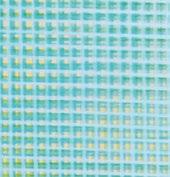

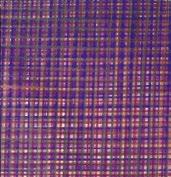

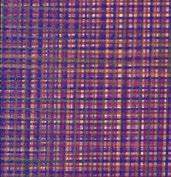

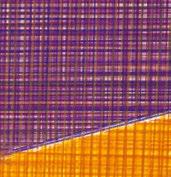

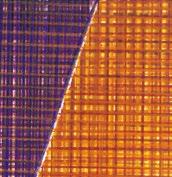

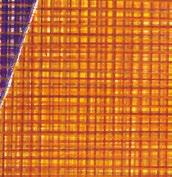

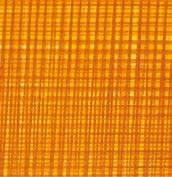

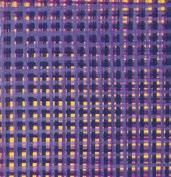

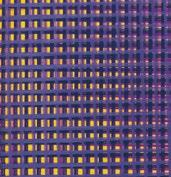

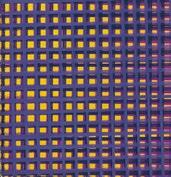

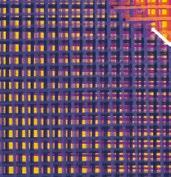

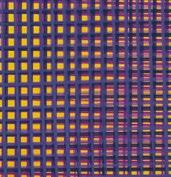

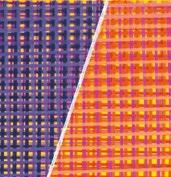

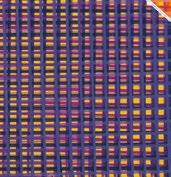

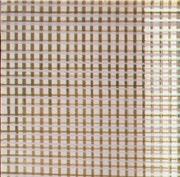

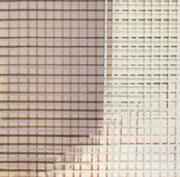

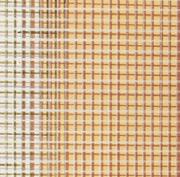

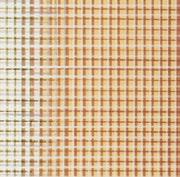

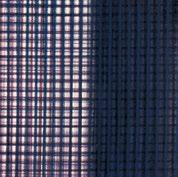

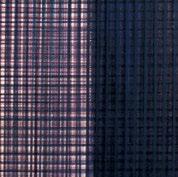

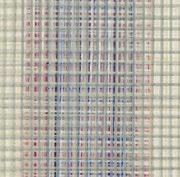

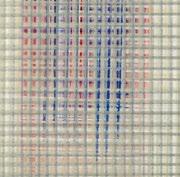

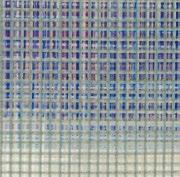

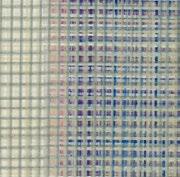

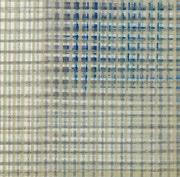

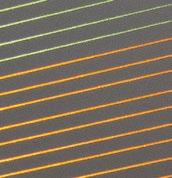

Manuel Barbadillo, who combined and ordered the modules by placing one after the other, Sevilla mounted and superimposed them, exploring the configuration of a “static rhythm.”7 Nevertheless, her careful use of color and, above all, of industrial materials accentuated the vibratory possibilities. Made of methacrylate, the module rotated and the geometrical repetition of the form, with its transparency and superimposition, generated new tones and soft luminous and visual effects [pp. 28, 29].

This investigation allowed her to develop a project in a dialogue with her geometric colleagues and brought her visibility as an artist in a difficult context, for besides the sluggishness of the art market at that time, she was prevented from advancing at the same pace as her companions by the fact she was a woman, the demands of bringing up her children, and the patriarchal context of late Francoism: “Not only did I not yet have a gallery,” she explained later, “but of course I wasn’t even able to exhibit. Moreover, when all my colleagues like Delgado, Yturralde, and Teixidor were already famous, I—and I can assure you it was the persecution of women—was not even allowed to exhibit. I was seen as a housewife with two children, who also happened to paint.”8 In spite of the difficulties, her contribution to the cybernetic exhibitions that arose from the networks at the Centro de Cálculo was far from tangential, and Soledad Sevilla established herself as one of the geometric artists of her generation in a field where relations between art and science were adjusting to technological advances.

The experimentation and scientism that attracted Sevilla’s interest kept pace with an international tendency to seek synchronization between art and “the age of speed.” 9 Responding to the scientific and technological logic that governed the bipolar confrontation of the Cold War, scientific progress had been accelerated and considerably spectacularized by the space race. In contrast to the horror of the annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, the 1960s displayed a renewed technological confidence. With the coming of the nuclear era, not only had production multiplied, pushing Western economies toward a welfare state dependent upon a consumer society, but the development of computing and cybernetics had become the engine of an unprecedented arms (and space) race with the object of ensuring control of new areas for territorial, ideological, and cultural colonization. 10 Sensitive to the radical mutations of the moment, abstraction attuned itself to the new rhythm of progress to integrate the scientific and technical advances of the new “jet age.”

Inserted within the technocratically inclined scientific logic that characterized advanced societies, well suited to the propagandistic opening up and developmentalism of Franco’s regime, geometric abstraction in Spain demonstrated not only that it belonged de facto to international aesthetic trends but also that it shared their concerns, taking part in a search for emancipating solutions to

Invading and Extending to Infinity: Soledad Sevilla and the Other Side of the Line

11

Ernesto García Camarero, prologue to Catalogue of The Computer Assisted Art Exhibition Held in Madrid in the Palacio Nacional de Congresos on the Occasion of the European Systems Engineering Symposium, exh. cat. (Madrid: Palacio Nacional de Congresos, 1971), 9, http://prev.elgranerocomun.net/ Foreword-1971.html.

12 Soledad Sevilla, “Texto para el catálogo The Computer Assisted Art,” reproduced in Soledad Sevilla. Transcurso, 126. On the frictions between technological optimism and a sector of the anti-Francoist Left, see Paula Barreiro López, “Antes del Arte in Spain (1968–1969): Merging Art, Science and Politics in the Heat of the Cold War,” Leonardo 53, no. 3 (2020): 299–303, https://doi.org/10.1162/leon_a_01889.

13 Rosalind E. Krauss, “Grids,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985).

14 José Díaz Cuyás, ed., Encuentros de Pamplona 1972. Fin de fiesta del arte experimental, exh. cat. (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2009) 140–47.

15 Sevilla, interview.

16 Castaños Alés, Los orígenes, 187.

17 Sevilla, interview.

the alienation provoked by the technical-industrial-capitalist complex. Against critiques of the machine as an instrument for social control, the investigators at the Centro de Cálculo defended its use for “a renaissance of mankind which, similar to that which took place in the 16th century, will be supported by an advanced technology.”11

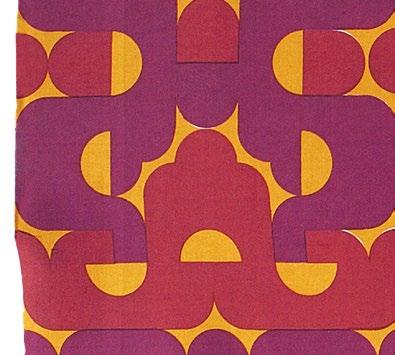

Sevilla took part with her colleagues at the Centro de Cálculo in various exhibitions that wove connections between science, art, and technology on the basis of the ideology of progress. One of them was The Computer Assisted Art show that was held during the 8th European Systems Engineering Symposium, organized in Madrid by IBM in 1971. The artist presented her investigation on “rhythm and its influence on the form of the rhythmic object” by means of a first-order module that she had started to study then but that she would continue working on throughout the 1970s.12 The seriality of the module led it to evolve rapidly into the grid, which was, as Rosalind Krauss was to observe years later, the emblem of the most advanced modernity.13

In 1972, the Pamplona Encounters permitted Soledad Sevilla a controlled internationalization of her work through her participation in the exhibition Arte computado (Computed Art), where the Centro de Cálculo group joined together with Latin American artists like Hugo Demarco, Rogelio Polesello, and Waldemar Cordeiro, as well as the experimental musicians John Cage and Iannis Xenakis, with whom they shared both the billing and the venue.14 The Encounters were an initiative that reversed the os-

tracizing of geometric trends in Spain in the second half of the 1960s and helped associate them with an international artistic scene marching at the same pace. Nevertheless, Sevilla recalls that she experienced the event far from the spotlight, shut up inside Prada Poole’s pneumatic dome where she devoted herself to its complex maintenance.15

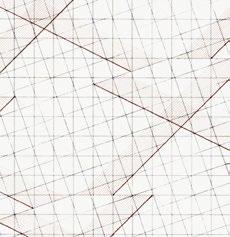

Her participation at the Centro de Cálculo was crucial for establishing the direction of her work, both because of the rich weekly debates and discussions and because it defined the geometric parameters of her production thereafter. The computer allowed her to work on the basis of an “exhaustive system of the possibilities of combination” from a given module, reaffirming her view of painting as a process of research first and foremost. 16 However, it also showed her the limits of a technology and medium that were still unprepared for the autonomous work of the artist, as they required the constant assistance of the computer technician: “With the machine, something happened: I realized that it wasn’t really my system, because I saw it was extremely slow. They would give me something and I would think I could do it much more quickly by hand.” 17 Even so, Sevilla devoted part of her time at the Centro de Cálculo to laying the foundations for her future output. Her investigations based on combinatorial analysis and modular problems led to her concentration of the line, creating meshes of hexagons or geometric forms in grids structured by an agile rhythm that would form the backbone of her composition.

18

Robert Morris, “Notes on Sculpture,” in Continuous Project Altered Daily (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993).

19

Soledad Sevilla, “Análisis y desarrollo de una red bimorfa compuesta por dos polígonos regulares de cuatro lados,” in Forma y medida en el arte español actual, exh. cat. (Madrid: Sala de Exposiciones de la Dirección General del Patrimonio Artístico, Archivos y Museos, 1977), 134.

20

Castaños Alés, Los orígenes, 188.

21

Sevilla, Sempere

22

Dan Cameron, “Soledad Sevilla. Entrevista,” in Dan Cameron and Mar Villaespesa, Soledad Sevilla. Toda la Torre, exh. cat. (La Algaba: Ayuntamiento de La Algaba, 1990), 3.

23

Soledad Sevilla, “Permutaciones y variaciones de una trama. Análisis perceptivo,” reproduced in Juan Bosco Díaz-Urmeneta Muñoz, Esperanza Guillén, and Yolanda Romero, Soledad Sevilla. Variaciones de una línea, 1966–1986, exh. cat. (Granada: Centro José Guerrero, 2015), 23.

The results were presented in the group exhibition Forma y medida en el arte español actual ( Form and Measure in Contemporary Spanish Art ) in 1977. Sevilla—one of four women artists selected for the exhibition along with Asins, Carmen Planes, and Pilar de la Vega—presented her work on network analysis. Employing “precise laws and rhythms” whereby repeated two-dimensional polygons are superimposed on a grid, Sevilla formed a structural base with an expansive logic. The works offered the viewer a perceptive experience of thought that reaffirmed the sculptor Robert Morris’s dictum that simplicity of form does not imply simplicity of experience. 18 Art, as Sevilla explained in the exhibition catalogue, “enclosed within fixed, immutable laws, can adopt infinite variations without departing from them, and with a single repeated theme can obtain very diverse formations.” 19 This work was directed toward a practice of the sensible that responded to what had become a strong certainty after her time at the SGAFP: “the experience [at the Centro de Cálculo] showed me that it wasn’t my medium: geometry interested me, but not depending upon the machine, the computer, technology. I preferred a geometry that we might call softer and more emotive.” 20 Nevertheless, she was also able to find this type of geometry at the SGAFP thanks to her exchanges of experience with Sempere. She coincided at the Seminar with him, and as her career advanced, she shared with him a lyrical understanding of formal experimentation in specific series and joint projects. 21

By the end of the 1970s, Sevilla had come to see the exercise of geometry as consubstantial not only with emotion but also with the breaking of the bounds of the plane by the line and its interaction with space. What triggered this step was a stay in Boston with a grant from the US-Spanish Joint Committee. This allowed her to cross the Atlantic and measure herself against a context relatively unexplored until then by Spanish artists, with certain exceptions like Antoni Muntadas, a close friend, and José María Yturralde, who had been a Juan March scholarship holder at MIT in Boston only a few years earlier.

“I studied and executed work on space for the first time in the USA,” Sevilla explains. “After concluding my development of vertical and horizontal lines and the sum of the two, the grid, I gradually incorporated the other figures that had formed part of my visual work, but without spatial interruptions, so that the work could be endless. The idea was that it should completely envelop the viewer, extending over the walls, ceiling, and floor.”22 The artist stated that the theoretical basis for this work had been laid while she was studying at Harvard University and had gained familiarity with CAVS at MIT, where her husband was teaching. However, the embryo of these interests lay in her 1970s investigations into grids and combinatorial analysis, which had allowed her to work, as she explained in her statement for her grant application, with “two-dimensional configurations extendible to infinity by repetition or transformation.”23

Invading and Extending to Infinity: Soledad Sevilla and the Other Side of the Line Paula Barreiro López

24

Soledad Sevilla, letter from Soledad Sevilla to Symor Slive, Harvard, January 14, 1982, reproduced in Yolanda Romero, ed., Soledad Sevilla. Instalaciones (Granada: Diputación Provincial de Granada, 1996), 25.

25 Sevilla, “Permutaciones,” 45.

26 “Master of Science in Visual Studies, Program,” 1978–79, reproduced in Elizabeth Goldring and Ellen Sebring, Centerbook: The Center for Advanced Visual Studies and the Evolution of Art-ScienceTechnology at MIT (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019), 67.

27

“I make sure that the events manifesting themselves in the course of the development are of a diverse nature, so that the viewer would be totally enveloped in that inconclusive, infinite space.”

Soledad Sevilla in Yolanda Romero, “Los inicios. 1968–1980,” in Soledad Sevilla. Transcurso, 23. Originally quoted in Soledad Sevilla, Soledad Sevilla. Tramas y variaciones. Memoria. 1979–80, exh. cat. (Madrid: Edikreis, 1981), n.p.

28 See Mar Villaespesa, “Memoria. Soledad Sevilla 1975–1995,” in Rosa Queralt and Mar Villaespesa (dir.), Memoria. Soledad Sevilla, 1975–1995, exh. cat. (Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura, 1995), 27, and, recently, Isabel Tejeda, A contratiempo. Medio siglo de artistas valencianas (1929–1980) (Valencia: IVAM, 2018), 166.

Expansion to infinity predetermined the possibility of a leap from the canvas into space, to the environment and the installation, whose actual materialization occurred after her return to Spain. However, there were several projects from her American years that pointed in this direction. Seven Days of Solitude, a proposal sent to the Fogg Museum in Cambridge (Massachusetts) in 1982, set out an intervention with white chalk on the floor of the courtyard of the cloister at the museum on the basis of oblique white lines with a strong optical effect [p. 120]. The large format and the fusion of the line with the space formed part of the artist’s interests, as she explained in her letter of introduction to the director of the museum, while implying a processual sensibility: the chalk would disappear as the visitors walked over it, like American Indian sand painting.24 While Sevilla expressed a sense of being disconnected from the US artistic scene she had joined and a need to return to her origins with her series Meninas (1981–1983) [pp. 76-83], the work she did in Boston demonstrates on the other hand a clear confluence with the processual, minimal, and post-minimal US tradition. In her grant application statement, the artist had already recognized herself in the work of Sol LeWitt, Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland, Dan Flavin, and Walter De Maria,25 and such an influence has persisted throughout her career, as demonstrated by her 2022 tributes to the painter Agnes Martin. In the meantime, Sevilla’s investigation in the United States brought her close to the practices taking place at CAVS. Under the direction of the former founder of the Zero Group, Otto Piene, the value of environmental art started to be recognized

in academic and experimental programs. From at least the academic year 1978–1979, a specific module formed part of the program of the Master of Science and Visual Studies and included investigations in sculpture and environmental painting, sculptural architecture, public leisure installations, celebrations, kinetic art, and so forth.26 Since the middle of the decade, such guidelines had fed, for example, Yturralde’s passage from the plane to the space with flying geometric structures during his stay at CAVS between 1975 and 1976.

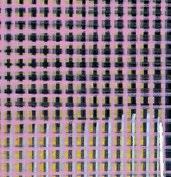

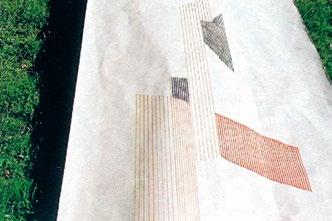

The enveloping dimension of space developed by Sevilla was in tune with such practices, which responded to a clear intention to affect the viewer.27 However, they also came from a practical need to visualize work produced on paper, as demonstrated by the photographs of the so-called MIT Line (1980), which displayed the rolls of paper of up to twelve meters with geometric grids that Sevilla had been working on for months, unfurled on the outer walls of MIT buildings and on the ground in the gardens [p. 128]. The continuous and expansive line of the work practically demanded breaking the bounds of the frame to penetrate real space, even if only to allow itself to be perceived.

I think that rather than distancing her from previous orthodox suppositions, as has been presumed,28 this step is of a piece with a drift toward environmental art, installation, and processual practices of many other geometric artists like the aforementioned Yturralde, but also Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark, Jesús Rafael Soto, and the minimalists themselves (as Michael Fried shrewdly observed as

29 Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood” (1967), in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 148–72.

30 Alexandre Alberro, Abstraction in Reverse: The Reconfigured Spectator in MidTwentieth-Century Latin American Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 4.

early as 1967).29 Perhaps inadvertently, however, Sevilla’s use of the line to break bounds during her MIT years shared in a transformation inherent to many of the geometric artists. For them, as Alexandre Alberro explains, “the artwork ceases to be stationary object accessible to immediate and exhaustive viewing (that is, seen in its entirety) and invites an embodied reception located in space and time. The artistic experience becomes a transitional phenomenon, prompting the spectator to relate with others and with an environment that surrounds and envelops her.”30 Sevilla’s US projects gave birth to the processes that ended up fully materializing upon her return to Spain in installations like the one for the Shakespeare Space at the Teatro Español in Madrid (1984), the Estratos (Strata) project (1985) for the courtyard of the Casa de la Cultura in Málaga, and her work for the group exhibition 8 de marzo (March 8, 1986) at the Colegio San Agustín in Málaga.

Invading and Extending to Infinity: Soledad Sevilla and the Other Side of the Line

1 Richard Wilhelm, I Ching: El libro de las mutaciones, trans. D. J. Vogelmann (1977; Barcelona: Edhasa, 2023), 12. Originally published as I Ging, das Buch der Wandlung (Munich: Eugen Diederichs Verlag, 1960).

2 The show I curated in 2015 at the Centro José Guerrero in Granada, Soledad Sevilla. Variaciones de una línea, 1966–1986, was the first monographic exhibition on this period in the artist’s career. For further information, see Juan Bosco Díaz-Urmeneta Muñoz, Esperanza Guillén, and Yolanda Romero, Soledad Sevilla. Variaciones de una línea, 1966–1986, exh. cat. (Granada: Centro José Guerrero, 2015).

3 Wilhelm, I Ching, 68.

4 Reproduced in its entirety in DíazUrmeneta Muñoz, Guillén, and Romero, Soledad Sevilla, 20–45.

Seen in retrospect, Soledad Sevilla’s career could be envisaged as a vast universe governed by the principle of change, where one event already includes the beginning of the next and where transformations succeed one another constantly. Every cycle includes its opposite, and change is viewed as the sole possible reality. Occurrences are interconnected, with night enclosed inside day and winter inside summer. Mutation is the only immutable thing. This philosophical and vital principle can be found in the I Ching or Book of Changes , a Chinese work of oracular wisdom whose reading, in the form of a religious ritual, has accompanied Soledad Sevilla for many years. In origin, the I Ching is a book without words, a finite succession of nonlinguistic signs (sixty-four hexagrams) with infinite meanings. Its reading and application are similarly unlimited and universal. It can be interpreted as a cosmogony or a poetic book and, as such, an untranslatable one. 1 In my view, this ancient text sheds a great deal of light on the artistic practice of Soledad Sevilla, who has moved for more than six decades through a creative universe in constant mutation governed by a duality in which opposites coexist, transiting freely from the geometric to the expressive, from the permanent to the ephemeral, from light to darkness, and from reason to emotion.

The Geometric

It is well known that Soledad Sevilla’s beginnings in the field of geometric abstraction go back to the Centro de Cálculo (Computing Center) of the Universidad de Madrid and to the Nueva Generación and Antes del Arte groups. This was the context in which the artist began her reflections on the problems and conditionings of spatial perception and the interrelation of forms, which she started to develop in her earliest works.2 We must refer back to those germinal moments, which began in the late 1960s and were projected throughout the following decade, in order to understand her later development. From the start, Soledad Sevilla devised a system based on only a few elements: first the hexagon and somewhat later the square. From these basic modules, she obtained others by displacement, symmetry, or turning them 45, 90, or 180 degrees. Together with such modular forms, which spread over the different formats and artistic media in a suggestion of infinite multiplication, the artist also experimented with linear elements arising from the suppression or addition of parts of the reticular figures she was using. In the line itself, “the world of duality appears, as established simultaneously with it are above and below, right and left, front and back; in a nutshell, the world of opposites.”3

In “Permutaciones y variaciones de una trama” (Permutations and variations of a web),4 [pp. 60, 61] the statement with which she applied for a grant from the US-Spanish Joint Committee to study in the United States from 1979 to 1982, the artist succinctly explained

5

Díaz-Urmeneta Muñoz, Guillén, and Romero, Soledad Sevilla, 45.

6 “MIT Line consisted of the action of spreading large rolls of paper over the outer walls of some of the buildings and the lawns of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, on which the artist had worked with different geometric webs (similar to those included in the series of drawings Keiko and Stella), and may be considered her first installation.” Yolanda Romero, “Notas a las variaciones de Soledad Sevilla,” in Díaz-Urmeneta Muñoz, Guillén, and Romero, Soledad Sevilla, 15.

7 Her practice of incorporating her vision of the work of other artists begins with this series but also accounts for later sets of works like Los toros (The Bulls) (1988–1991), based on Guido Reni’s Atalanta and Hippomenes (1618–1619); Los apóstoles (The Apostles), whose origins lie in The Twelve Apostles by Rubens; and her more recent homages to Agnes Martin and Eusebio Sempere.

the bases of her creative process in the 1970s. In the same text, however, Sevilla stresses her wish to begin new investigations, moving from the two-dimensional plane to the three-dimensional space, from painting to installation, in order to incorporate the public: “owing to the physical characteristics of the work I propose, the viewer would be totally enveloped by this inconclusive, mysterious, and unattainable space.”5

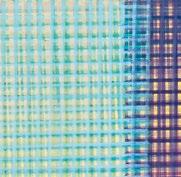

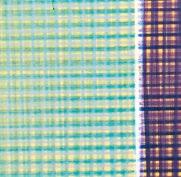

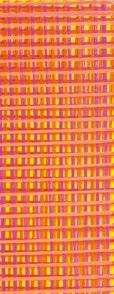

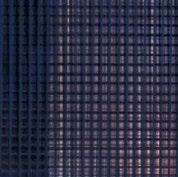

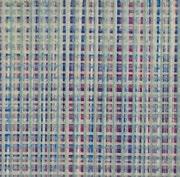

As she foresaw, it was her period in the United States that allowed her to close one cycle and open others. In Boston, she produced the series Keiko [pp. 62, 63] and Stella (1980), based on a reiterative use of the line. The title of the second series was a tribute to Frank Stella, one of her artistic referents along with Sol LeWitt, whose work she was able to gain firsthand knowledge of thanks to her stay in North America. There, almost without realizing it, she embarked on her first spatial action, MIT Line (1980),6 [p. 128] as well as her first drawings of superimposed quadrangular grids, entitled Belmont (1980) [pp. 74, 75], a clear prelude to the two series that would mark her production in the early 1980s, Meninas [pp. 76-83] and Alhambras [pp. 84-95].

On various occasions, Soledad Sevilla has explained that the origins of these two series lie in the classes she attended at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and at Harvard

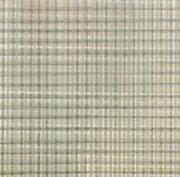

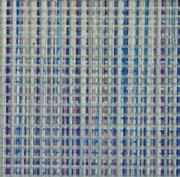

University. Just when the physical distance from her own culture was greatest, her interest was aroused by one of the key works of the history of Spanish painting, Velázquez’s Las Meninas 7 Soledad Sevilla’s way of viewing this painting is centered on its space, that enigmatic place where the scene is set, which is configured through the immaterial element of light. She recreates this space in her work by means of superimposed grids of squares, a technique already essayed in her Belmont series drawings. This technique of showing by concealing, allowing a painting, an architectural form, or a landscape to be glimpsed or intuited through grids or lattices, was to guide many of her future works. Meninas also introduces a new approach to color, an element that now comes increasingly to the fore in her oeuvre. These are colors that seek vibration and whose purpose is to dispel and soften the rigidity of the geometric composition, configuring an indefinite and mysterious space of the kind she mentions in her Boston statement. Finally, Meninas also helps her to systematize a working method materialized in series that deploy various formats. Smallformat work, generally on paper, is the starting point that allows her to formalize ideas, while the medium-sized format acts as an index or route map. However, her true interest lies in large-format work owing to its expansive and enveloping nature.

In a single picture, I don’t say everything I want to say. I need more pictures, more moments. It’s hard to develop ideas. They are rather like a book, a novel structured in chapters, in phases. There is something to

8 Yolanda Romero, “Una conversación con Soledad Sevilla,” in Soledad Sevilla. El espacio y el recinto, exh. cat. (Valencia: Institut Valencià d’Art Modern [IVAM], 2001), 15–17.

9 Oleg Grabar, The Alhambra (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978).

be told there, and you have to do it step-by-step. It takes time for me to make the image I’m producing into the one that interests me, and once that image is drawing near or starting to resemble what I want to achieve, there still remains the whole task of developing it, perfecting it, and exhausting it . . . Suddenly, though, there comes a moment when you say: “I’m bored. I can do this now: it’s come out.” And when it comes out, I’m no longer at all interested in carrying on with it.8

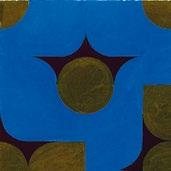

The Meninas, developed between 1981 and 1983, were followed by her next series, the Alhambras, on which she worked from 1984 to 1987. In the case of the Alhambras, it was the classes taught at Harvard University by Oleg Grabar,9 a specialist in ancient Islamic art, that aroused Soledad Sevilla’s interest in the architecture of the Nasrid palace. In 1984, she stayed for the first of many times at the artists’ residence of the Fundación Rodríguez-Acosta in Granada, where she produced the initial drawings and small-format paintings that would later serve as a guide for the large pieces in this series. Four years later, the Alhambras were presented to the public at the Galería Montenegro in Madrid, the Galería Palace in Granada, and the Fundación Rodríguez-Acosta. In the catalogue of that show, the artist reviewed the series in these terms:

In the work I have carried out over the course of four years, I have tried to reflect the mark left on me by both the superficial and the profound aspects of the architecture of the Alhambra. Visible forms and frames of mind have constituted the raw material amalgamated in

10 Soledad Sevilla, “La Alhambra,” in Carmen González de Castro, Yolanda Romero, and Soledad Sevilla, Soledad Sevilla. Transcurso de una obra exh. cat. (Granada: Instituto de América de Santa Fe, 2008), 129–30. Originally published in Francisco Calvo Serraller and Soledad Sevilla, Soledad Sevilla. La Alhambra, exh. cat. (Madrid: Galería Montenegro, 1987), n.p.

11 Grabar, The Alhambra, 57.

12 Grabar, The Alhambra, 114.

the paintings I have produced during this period, which are centered on three themes that have arisen from contemplating the world of the Alhambra: the magic of portals, the magic of reflections, and the magic of shadows. All of them are transformed into space, and an attempt is made to render this space on the canvases through mists, insinuations, and lights.10

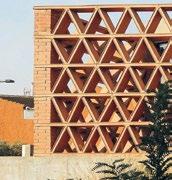

Soledad Sevilla identified three parts of the Nasrid monument with each of these three themes respectively: the Golden Room, the Court of the Myrtles, and the Court of the Lions. The first is a monumental entrance to the palaces of Muhammad V comprising two portals of exactly the same shape and size that act as an essential fulcrum, as they can either lead visitors out of the precinct or provide an entrance to the majestic Court of the Myrtles. A poem inscribed on the wall identifies the wall as a “gate where [roads] bifurcate and through [which] the East envies the West.”11 As Grabar has pointed out, the Golden Room “is a gate, but it is also a trap, for it does not indicate the correct direction to take.”12 For the artist, this world of forking paths, entrances, and gateways symbolizes the mysterious and the hidden: that which is only glimpsed without being completely shown.

The next architectural setting, the Court of the Myrtles, is reached, if we make the “right” decision, via a passage at an angle to the Golden Room. It is structured around a large pool of water that becomes a mirror reflecting the surrounding architecture. The still water of these ponds, an essential element of the Alhambra as a

whole, interests the artist not only because of the illusory world of the mirrored reflection but also because of the organic world of nature, which was gradually to appear in her work in various ways. The last of the spaces Soledad Sevilla cites is the famous Court of the Lions, flanked by a succession of rooms with honeycomblike muqarnas domes creating a rhythmic effect of illuminated and shaded areas. This world of shadows and chiaroscuro is precisely one of the interests reflected in the paintings she dedicates to the Court of the Lions, which capture the succession of columns and the interstices of light and darkness that outline them.

It is not surprising that Soledad Sevilla should have felt in tune with this indescribably beautiful place, which she spent many days visiting and studying. The geometric composition that organizes its architecture, with the rectangular court as the fundamental module organizing the space of all three of the areas mentioned, and its ornamental program, largely based on modules in series that could be infinitely repeated, were already to be found in many of the exercises on grids from the start of her years in Madrid. The Alhambra, however, contributed above all a poetic and emotional element to her work, opening a new path in her creative process that distanced her from the cold premises of minimalism, still discernible in her Meninas. When Soledad Sevilla decided to paint this architecture, she was not aiming at a formal representation of it. Her goal was, on the one hand, to capture those magically enveloping spaces, which change as they are lit by the sun or the moon (hence the nocturnal and daytime versions common to nearly all

the works in this series), and, on the other, to reflect the specular condition of reality, that world of mirrors that disrupts and inverts the sense of things and is made possible thanks to the motionless waters of the pools. It is curious to see how the titles she gave her pieces themselves intensified this relationship with the poetic after her Alhambras. Her 1960s and 1970s works had no titles. After her stay in the United States, a more personal note became apparent: Stella or Mondrian, in homage to artists she admired; Keiko, the name of a Japanese friend; Belmont, the residential neighborhood where she lived in Boston and whose colors she tried to capture in her paintings; and even Meninas, which she distinguished merely by naming them.

The Alhambras, on the other hand, are singularized with titles derived from the poetic inscriptions that cover different parts of the architecture of the Alhambra, many of them the work of the Nasrid poet Ibn Zamrak. After this series, poetry and painting became inseparable in her oeuvre: “I always try to transform the themes into a result that will arouse emotion visually, that will be poetic, and if that disappears, it is not my intention.”13

A few months after the presentation of the Alhambras in Granada, the Sala Montcada of the Fundación ”la Caixa” played host to her installation Fons et Origo (1987) in Barcelona. Very early on, Sole-

14 For more information on this aspect of Soledad Sevilla’s work, see Yolanda Romero, ed., Soledad Sevilla. Instalaciones (Granada: Diputación provincial de Granada, 1996).

15 This installation was presented within the framework of the Plus Ultra project, curated by Mar Villaespesa and produced by BNV Producciones at the Vélez-Blanco Castle (Almería) as part of Expo ’92.

16 In Fons et Origo, she used a sound composition by the artist Lugán. El poder de la tarde (The Power of the Evening, 1984) included a recording of birdsong.

17 Romero, “Una conversación,” 15.

18 Romero, “Una conversación,” 11.

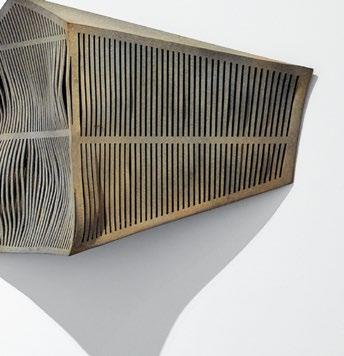

dad Sevilla experienced a special desire to make a reality of the space suggested in her paintings through installations.14 While MIT Line—linked, as indicated above, to her series of drawings Stella and Keiko—may be regarded as her first approach to the experience of the installation, Fons et Origo must be understood as an extension of the series of paintings inspired by the Nasrid monument, a reconstruction of the magical and unreal ambience that appeared on her canvases, and the first in a succession of installations formed by threads that trap and reflect the space and the light, which thus become the central theme of her investigation. On many occasions, her installations can be seen as the end of a pictorial cycle, a three-dimensional expression that completes a set of paintings. In perhaps rather fewer cases, the installation is the starting point for a new cycle, as in the project for the Vélez-Blanco Castle, Mayo 1904–1992 , 15 which served as the stimulus for the series of paintings En ruinas (In Ruins, 1993–1994) and Vélez Blanco (1995). From the start, the installation became a space of experimentation for Soledad Sevilla where she could add new elements to her work, such as sound,16 the organic (water, earth, fire, ice, vegetation), or industrial materials (copper, netting, wires), but also a space for interacting with all the senses of the viewer, who no longer uses only sight to approach her work but also touch, hearing, and even smell: “For me, an installation is light, the light that comes in through the windows, it is the smell that invades a space, it is sound, it is something immaterial that is creating an atmosphere.”17 Moreover, in installations, the artist

allows herself to be more figurative and narrative, something she avoids in painting. It is only in this format that the abstractionfiguration dialectic common to so many artists of her time is resolved without contradictions.

For Soledad Sevilla, however, the installation represents above all the ephemeral condition of art in contrast to the permanence of traditional formats like painting or sculpture: “I am often weighed down by the accumulation of elements and objects, and in that sense the ephemeral is perfect: it happens and disappears. The fact that the installation is produced in a time and space, and that afterward only the memory remains, adds a highly suggestive poetics to it.”18 Over the course of her long career, she has embarked on nearly a hundred spatial interventions. Some might be considered subtle versions of the same element, but it is undoubtedly more appropriate to think of them as new works, since each one is deployed in a different place with its own conditioning factors, and all reveal very different approaches. The most illustrative case is that of her installations of cotton threads, which she has produced from the 1990s to the present and which transform the light into delicate metaphors of day or night. Some are linked by their location in a singular historic building, such as Toda la torre (All the Tower, 1990) in the Tower of Los Guzmanes in La Algaba, near Seville; Somni recobrat (Recovered Dream, 1993) in an old palace in Palma de Mallorca; and, more recently, De la luz del sol y de la luna (On Sunlight and Moonlight, 2021), mounted at the Museo Patio Herreriano in Valladolid. Flashes of light filtered

19 Designed for the Galería Soledad Lorenzo in Madrid, it comprises two parts: an initial section with two crisscrossing clusters of copper wires, and a final part in the form of an apse where the vertically taut filaments release drops of water like a fountain of rays of light. This was the first version of a cycle whose titles were taken from the name of the city where each piece was presented.

20 This installation was produced at the Casa Horno de Oro in Granada for the aforementioned exhibition Soledad Sevilla. Variaciones de una

21 The courtyards can be seen today in a gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

through filaments, this time made of copper, are also featured in de La hora de la siesta (The Hour of the Siesta, 1990), Soledad la que recita la poesía es ella (Soledad the One Reciting the Poetry Is Her, 1991),19 which incorporates water, and Casa de oro (Golden House, 2015), where the artist transformed the courtyard of a Moorish house in Granada’s Albaicín district with the parallel planes formed by 1,300 orange copper filaments, which surrounded viewers with reflections that changed based on their position and the time of day.20

Soledad Sevilla’s spatial interventions play with the perception of the public and require an active spectator, quite unlike the immersive experiences of today that enhance passivity. In the Vélez-Blanco Castle, a historic building in the province of Almería whose Renaissance courtyards were removed and sold to a US collector, the artist literally invited us to create/imagine that place collectively.21 Upon entering the huge bare courtyard, the viewer at first saw nothing, but as night fell, some projections slowly began to summon up the missing arcades. This perceptual game highlighted the fragility of that unreal architecture and required a collaborative public who would help to construct the space [p. 97]

In the 1990s, after the experience of Vélez-Blanco, Soledad Sevilla’s pictorial work started to drift toward emptiness in a search for

radical abstraction. The geometric grids become less apparent, and the lines fade away until they literally vanish. This departure was already announced in Atropellar la razón (Riding Roughshod over Reason, 1991) [p. 133], which made way for two of her most abstract series of paintings, Vélez Blanco and En ruinas. Evident in these works is the inspiration the artist drew from the walls removed from the castle’s courtyards, which had impressed her so deeply on her first visit, as well as the influence of the work of Mark Rothko. The format of some of these works necessitates a corporeal action on the part of both the viewer and the artist herself. They are paintings to be explored (some are more than seven meters long) that evoke the monumentality, the ruin, or the restrained poetry of the walls, factors that became the catalyst for the different series and installations Sevilla produced up to the early 2000s.

Paradoxically, these extreme formats, which call for a great physical effort on the part of the artist, originate in her need to use a technique, oil painting, that would allow her to paint more slowly after her 1996 health crisis. The works of this period also incorporate a temporal dimension. The walls that interest the artist—the ruins of the castle in Almería, the Arab walls of Granada, the abandoned tuna fishery of El Rompido—have been modified by time and therefore have a memory. However, while the wall is initially impenetrable, especially in Vélez Blanco, her paintings start to be invaded in the mid-1990s by a rhythmic accumulation of brushstrokes, as we can see in En ruinas II (In Ruins II,

22 Romero, “Una conversación,” 17.

23 Various versions of this installation, shown for the first time in Spain at the Galería Soledad Lorenzo in 1998, have been presented in different Spanish cities.

24 Antonio Machado, “A una España joven,” 1915, in Poesías completas (Madrid: Publicaciones de la Residencia de Estudiantes, 1917), series 4, 7:256.

25 A version of this installation was produced for the Centro de Creación Contemporánea de Andalucía (C3A) in 2019 under the title La salvación de lo bello (The Salvation of the Beautiful).

26 This retrospective exhibition was held in 2001 at the Centre del Carme in Valencia, managed by the Institut Valencià d’Art Modern (IVAM). The show, which I curated, began with her first geometric works, showed her most recent series, and included the installations Con una vara de mimbre (With a Willow Switch) (2000) and El Rompido (2001).

1995) [pp. 98-99] and Díptico de Valencia (Valencia Diptych, 1996) [pp. 100-101]. It is the presence of nature that has transformed the emptiness of these walls by appropriating them. What she has called a “vegetable magma” compacts the surface of the canvas, gradually revealing an opening, a chink of light.22 As on previous occasions, these new pictorial cycles, vegetable walls and “insomnias,” were soon transmuted into installations. The contained vibration of canvases like Apamea (1999) [pp. 104-105] and Insomnio madrugada (Early Morning Insomnia, 2000) [pp. 142-143] found release in a three-dimensional work, El tiempo vuela (Time Flies, 1998) [pp. 108-111], which incorporated real movement and sound.23 This installation, made up of a thousand butterflies screen-printed on paper that revolve incessantly on a clockwork mechanism at a one-second rhythm, conveys to the viewer the emotion produced in the artist by a wall covered with ivy stirred by the breeze. However, the butterflies are a metaphor: the process of metamorphosis that turns the caterpillar into a butterfly in the final phase of its life symbolizes the inexorable passage of time, an idea reinforced by the line of poetry by Antonio Machado inscribed in white enamel on the wall: “y es hoy aquel mañana de ayer” (“and today is that tomorrow of yesterday”).24 Time seen as a motor that transforms nature was a question Soledad Sevilla had previously addressed in one of her first installations, Leche y sangre (Milk and Blood, 1986). On that occasion, she covered the walls of the Galería Montenegro in Madrid from floor to ceiling with thirty-six thousand red carnations that faded as the days

went by, offering glimpses of the white walls.25 Like a contemporary vanitas, the faded flower also refers to death and the fleetingness of life. The installation El Rompido (2001) similarly reflects the artist’s emotional connection with landscape and nature. The ruins of the tuna fishery in the small village of El Rompido (Huelva) exercised a powerful influence over Sevilla, which explains not only the origin of the Insomnios series (2000) but also that of the installation that closed her exhibition for the Centre del Carme in Valencia, Soledad Sevilla. El espacio y el recinto (Soledad Sevilla: Space and Precinct).26 The intervention occupied two opposing spaces that functioned as negative and positive by reproducing the effect of a crack in the wall in different ways. In the first, the crack was constructed with an opaque material, bronze. In the second, by contrast, a cracked and broken wall constructed with the aid of light allowed a glimpse of the reality existing behind the wall: a ruined alleyway overgrown with plants. El Rompido and Insomnios marked the end of a cycle that almost coincided with the start of the new century. From then until now, Soledad Sevilla’s creative career has continued with its tireless exploration of her most intimate concerns, which persist in different forms in each new cycle. For in that book without words that constitutes the artist’s creative universe, every sign, every work, can be read in an infinite number of ways, and, as the I Ching shows us, its reading, equally limitless and universal, can be interpreted as a cosmogony, as a poetic and, as such, untranslatable book. Therein lies its grandeur.

Atmosphere, Languid Aura _______ 1985–1986

from an interview first published

Kevin Power: Let’s begin returning to the late 1960s and early 1970s. I’d like you to situate yourself in that context and talk a little about what it was you defined yourself within and what it was you defined yourself against. [. . .]

Soledad Sevilla: As far as I was concerned there were no outside influences. We all had very little information and I myself almost none at all. At this time I was more concerned with being a housewife and a mother, since my children were very young, than with being an artist. Of course I never lost sight of my activity as an artist, but inevitably all the rest weighed on me. [. . .] All of this was, of course, a reaction against what I had been taught at art school where everything was totally academic and conservative. They made you go through a whole series of canons—figuration, landscape, drawing, etc. In short, it was the type of education that was completely useless as far as I was concerned. What I was looking for was a colder and more technical art as compared to what might be called a highly domestic art.

K. P.: I’d also like to know something of the significance of the Centro de Cálculo in the Universidad de Madrid between 1969 and 1971.

S. S.: Yes, Elena Asins, Gerardo Delgado, Eusebio Sempere, José María Yturralde, José Luis Alexanco were all there. [. . .] What we were trying to do with Ernesto García Camarero, the director of the course, was to make ar t with the computer. The objective was to produce, as the title of the course makes clear, automatic visual forms. It was a matter of researching, or rather of producing a piece of work, so that the computer could intervene directly or form part of the creative process. This possibility appealed to me, since it was utterly different from all that I had been taught. It was a particularly rich experience. [. . .] However, I was already quite sure that it was not my medium and that its only value was as a form of research. [. . .] It was rather a visceral reaction on my part, which most probably I did not even analyze very deeply. I was simply lacking something, the education I had been given at art school was failing me, I saw there were important aspects missing from that education. In time I would decide on the path to follow; actually it wasn’t long before I abandoned that colder aspect I first thought was my aim and realized my field of work was something much more personal.

K. P.: I believe you became involved in a project on synergy with the Asociación Española de Biofísica.

S. S.: Yes, in a project called “Palpebronasal Motor Synergy,” which I did on one of my journeys to the Sahara desert with my ex-husband, who was a member of the association. Another member asked me to carry out there some research for him, for he wanted to prove this theory of his about a face muscle that moves involuntarily when one blinks. According to him, this was something atavistic common to primitive cultures that contemporary man has lost, but which existed in prehistoric people, who employed their sense of smell in order to defend themselves from their enemies. So this man wanted me to carry out a statistical study on the desert nomads, and I did it by observing them, asking them to blink and taking notes on the movement of this little muscle. But synergy had nothing to do with my work, this was just collaborating with this person who had asked me to do so.

K. P.: You go to the States in the 1970s and it is there in Boston that you begin to turn toward the concept of installation. What was it that specifically influenced you to turn in this direction and what were the principal interests that you carried over from your painting to the installation pieces?

S. S.: [. . .] I felt the need to analyze my personal development in this geometrical world I was immersed in, the need to redefine what stage of my research I had reached and why and how I had gotten there. I wanted to go back in time and, starting at the very beginning, identify all the elements that had taken part in my work so that I could develop them without any spatial interruptions, in such a way that they might extend in space and you could move from one element to another naturally, instead of getting the impression of their being independent pictures. Rather than that I wanted these elements I had been working with—especially the irregular hexagon—to succeed each other in space.

K. P.: Your first installation was MIT Line (1980).

S. S.: Initially I did not consider MIT Line an installation. As I said before I simply needed to unroll those rolls of paper there in order to get a global view of my work. But, on the other hand, the fact is that there are some photos of that experience. What I mean is that, even if it was just at a subconscious level, I might have been considering this as an action or installation.

springtime, late in the afternoon, and I lay on a bench in San Lorenzo Square. I looked up and saw the branches of the trees and the intensity of the colors and the light of Seville, and I heard the sound of birds. I was deeply moved, so I decided to do this installation. I covered the gallery ceiling with vine branches and added a red light through which I tried to materialize the light of spring in Seville, and I also recorded the birdsong heard in the city.

K. P.: You followed this, as you said before, with the even more dramatic and poetic Leche y sangre (Milk and Blood, 1986). [. . .]

K. P.: Then [following your project Espacio Shakespeare (Shakespeare Space, 1983)] came Estratos (Strata) in the Casa de Cultura in Málaga, where there is a movement of depth on the plane of the floor. What was your point here? What were the strata that you intended to explore?

S. S.: There was a big controversy in Málaga at that time over the fact that this building that housed the Casa de Cultura had been built on top of some archaeological remains. What I did once again was a drawing on the floor, or rather a photomontage, in order to draw attention to this polemical situation underneath the foundations. I called it Estratos because various stages of the history of mankind had been superimposed on one another. Our own contemporary world appeared on top of some Roman ruins. Initially we intended to have this project published in a journal, but in the end this was never done.

K. P.: Up until this point your works were classically formalist in their conception and the human metaphors were not explicit although they were manifestly present. However, with El poder de la tarde (The Power of the Evening, 1984) your poetic vein now openly assumes its voice. [. . .] The world now invades space, and life contaminates, stains, energizes ideas. [. . .] Was this a conscious rejection of excessively formalist ploys or was it something organic, intuitive that could no longer be kept out?

S. S.: [. . .] So El poder de la tarde was my first installation properly speaking, and the intention behind it was more poetic, through the use of the light, the sound recorded in Seville, the branches, and so on. One day I was working on a catalogue with Gerardo Delgado in his studio in Seville when we went out for some reason. It was

S. S.: [. . .] It was a sort of protest installation in my view. At that time, when I returned from the United States, the kind of work I was proposing, this cold, objective, geometrical work, which had nothing to do with the strong, violent, rabid expressionist figurativism that was in fashion then, was hard to understand. These were also the important years when Spanish art was starting to gain international recognition, which meant more opportunities to show your work, sell it, and have a greater international projection, but this was something I was excluded from. That is why I decided to do this installation using carnations. The use of the carnations was not connected to revolution or anything of that kind but to the simple fact that they are flowers and as such are not subject to changing fashions, which is as it should be in art: each artist should make use of what he fancies, be it lines, flowers, or whatever. The quality of the work should reside in the work itself and be independent of current trends or of whatever society happens to admire at that particular time. So the carnations represented my idea of what art should be.

K. P.: What we were talking about regarding Leche y sangre also appears, for example, in Toda la torre (la noche, el día y el cielo) (All the Tower [Night, Day, and Sky], 1990) that you conceived in the Tower of Los Guzmanes. In this piece light evidently defines space. The threads of cotton are like beams of light coming into or existing within a room. You exploit the spaces to bring forth different moods of day and night—mystic but not theatrical?

S. S.: I wanted to superimpose natural light onto the representation of light. That is why I included those flashes of light that burst

from the windows or seared diagonally across space. It was a way of representing light through other elements. The fine cotton wool provided me with what I sought, as it is both subtle and real, both evanescent and, at the same time, present. When we were children at my grandparents’ house in Cuenca, we had to have our siesta in this huge room that opened onto a patio. The light of those summer afternoons, with the dust motes dancing in it, streamed in through the cracks in the doors and windows, and my sisters and I would play with the rays of sunlight that filtered into the dark room. I now try to recapture all those memories and they undoubtedly become part of the elements I use in my work. In the Tower of Los Guzmanes I covered what used to be the roof and which was now open to the sky with a blue canvas to get the blueish atmosphere that enveloped the spectator. The night was represented by the ray of light that faded into the pond, and the day was the warm space, the flashes of light that burst in, the sounds of summer. It was a conscious dramatization of some elements related to the poetics of day, night, and sky.

K. P.: You continue along much the same lines in Soledad la que recita la poesía es ella (Soledad the One Reciting the Poetry Is Her) that you presented in the Galería Soledad Lorenzo, where you make use of a copper wire instead of cotton thread. Was that merely a practical or functional change or did it have some other purpose and meaning?

S. S.: Before that I had done the installation in Crete, La hora de la siesta (The Hour of the Siesta), for the Minos Beach Art Symposium, which was in the open air and was to last for six months. I decided to use copper instead of cotton so that it lasted longer. As I was very pleased with the way it worked out in Crete, with those very special vibrations that are created when light falls on copper, I used it again in this other installation. Another reason was that the internal element had water sliding down vertical threads, and this would not have been possible had I used cotton wool. The effect was prettier in Crete because the light was natural and gradually changed throughout the day. The effect of the lighting on the work was different depending on the angle at which the sun struck it. [. . .] The three elements I wanted to play with in Soledad la que recita la poesía es ella were smoke, fire, and moving water. I wanted to do a piece about women and love, and I thought it was impossible

to paint it, because these are subjects that, both in literature and music, have been very productive, but in the visual arts are very difficult to represent. I simply would not know what to paint. I chose those elements as symbols of the female world. The moving water represented fertility, smoke was seduction, and fire was the physical act of love.

K. P.: Speaking of your work, you note in an interview: “I try to convey a sensation of penetration, of depth, of something that transports you to some other place. I try to eliminate as many details as possible and limit myself to the absolute minimum so that the essential can be seen. I do not feel satisfied when the result is excessively figurative. It is not easy to get to the point I want to reach. And that’s why perhaps I tend to insist on the repetition of certain themes. Sometimes I need to return to the same ideas in order to purify them.” This sounds like a variation on, or new version, of Mies van der Rohe’s “less is more.” At what point do you feel you have excluded enough? At the point when you are about to slip into the void?

S. S.: What you have just said is a perfect summary of my intentions. Using the minimum amount of elements I try to convey the maximum number of sensations. Of course there comes a point where you run the risk that the piece would come to nothing.

K. P.: La hora de la siesta is saturated in the lore and culture of the Mediterranean and this becomes even more evident in Nos fuimos a Cayambe (We Went to Cayambe, 1991) where you focus on your love of bullfighting. [. . .] Could you talk of your interest in bullfighting and what it was that moved you to present the image in this way? Could you also explain where the title of the piece comes from?

S. S.: This is one of the installations in which I come closest to being a sculptor, something I always say I am not. I have been very fond of bullfighting ever since I was a child. I was doing the series of paintings on bullfighting, and what struck me in particular in bullfights was the “suerte de varas,” the stage of the corrida when the picador uses his lance on the bull. For the first time after having attended thousands of bullfights I saw this through the eyes

of an artist, especially all those capes standing erect together. I thought it was a beautiful image and decided to use the capes and the red rags in this series because it is very interesting to see how such a flimsy element allows you to face a situation as intense as confronting a bull, and, besides, I find it exemplary, as a philosophy of life, that people can run such a risk armed only with art, intelligence, and beauty. [. . .] I have always said that I learn a lot about human behavior in a bullfight. In the ring everyone is committed to everybody else, and I suppose this must be due to the fact that death is always present and tragedy might occur at any moment. The title comes from an excellent text by Juan Luis Panero, which I requested permission to use in the catalogue of the exhibition of the bullfight series. He tells in this text of how he and Domingo Dominguín’s widow visited Dominguín’s grave in Cayambe, a village in the high plateau of Bolivia where Dominguín committed suicide. According to Panero, Dominguín’s was “a suicide in a profounder sense than anyone else’s,” since it occurred far from his world, far from the bull, far from any warmth. [. . .]

K. P.: Would you agree that the acrylic works that you did to accompany this piece are also very much about the movement of the cape, about the ritual dance they perform throughout the corrida?

S. S.: I intended to use the capes and red rags and deprive them of movement. In the end somehow the space came out of this. The only thing I knew while I was doing the paintings with these elements was that I didn’t like what I was doing, till I did the final tryptic, where I portrayed the empty space and a wall that was intended to represent the burladero, the boards behind which the bullfighter takes refuge from the bull, and I must say I did like this painting. But, despite this, I was never totally satisfied with the series. I was thinking about space, but the incongruity was that, when I thought about it, I brought in some static isolated elements, instead of something really spatial. For the installation I did different groupings of capes, and the one I liked best was the one I called “Zurbarán,” where all the capes were yellow, since it reminded me of the monks Zurbarán painted.

of what I want to do?” You continue drawing particular attention to the importance of this series arguing that it produced significant changes in your character and in your attitude as a painter. You specifically mention the fact that the works that constitute the series seem to have little to do with each other in a formal sense and are as such evidence of a major rupture in what has been the normal course of your work. It is also an unusually lengthy series on which you were working for approximately four or five years. Could you talk a little about this process and what was so significant about it for you, particularly what changes it produced in your attitude as a painter? [. . .]

S. S.: I never have a very clear idea of what I want to do. I start with a feeling, a vague idea of something that is going through my mind, but I don’t know how to get it into the painting, how to expose it there in concrete terms. I gradually work it out through painting until I get the hang of it and hit on the colors, shapes, and size of the series. It is the creative process itself that reveals it to you. The work on this bullfighting series was particularly lengthy, and as I was saying I probably set out from a mistaken premise. I think the smart thing to do would be to go back over that series. When a cycle is over and you get a perspective on it, it is easier to see where mistakes lie.

K. P.: It hardly needs saying that the progression of the Meninas , the Alhambras , and Nos fuimos a Cayambe seems like a spe cific involvement with “the Spanishness of Spanish art or Spanish culture.” [. . .] I think it is also clear enough that the installation in the Vélez Blanco Castle (1992) in Almería can be seen in similar terms. [. . .]

K. P.: What is it that you mean when you said in this context: “How can I discover the mystery of life if not through painting the mystery