Cine(so)matrix

Angela Melitopoulos

Angela Melitopoulos

Cine(so)matrix

Angela Melitopoulos

Angela Melitopoulos

Considered one of the most outstanding gures on the European artistic scene in recent decades, Angela Melitopoulos (Munich, 1961) addresses issues such as the migratory experience, popular struggles against predatory practices in industrial society, the capacity for resistance among minority groups, and the prevalence of magical thinking in contemporary culture. Her critical approach to these subjects cannot be separated from her re ections on the language of video and image, and the possibilities they a ord in constructing individual or collective identities. Taking Cine(so)matrix as a title, a term Melitopoulos coined in reference to her own practice, this exhibition held in the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía showcases the most signi cant projects undertaken by the artist from the late 1990s to the present day.

By featuring such a wide range of her work, the show makes evident how constant her will to experiment has been, as well as her willingness to collaborate with other intellectuals and creators. A display of multiscreen video installations re ects Melitopoulos’s interest in experimenting with ways of working with sound and visual stimuli that transcend the traditional cinematographic experience. The spatial design and use of multiple screens allows the artist to pursue a narrative style that endeavors to capture the nonlinear workings of human thought.

While constituting a technological challenge, putting on a show like this a ords us the chance to get to know the bulk of Melitopoulos’s work from the last few decades and identify the principal threads that connect her art to her broader investigation into video. The texts and essays gathered in this catalogue in turn help us to appreciate key aspects of her vision and navigate the various audiovisual experiments she’s performed in an already extensive career.

Miquel Iceta i Llorens Minister for Culture and Sport

Since studying at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf under Korean artist and video-art pioneer Nam June Paik, Angela Melitopoulos (Munich, 1961) has developed a practice based on rigorous artistic research and an expanded sense of what video is. As the Italian thinker Maurizio Lazzarato notes, Melitopoulos’s research, Bergsonian in nature, reached a watershed moment when she discovered “an atomic, molecular movement” in video technology that made a new sense of perception and way of shooting and editing video possible, one “necessarily di erent from cinema.” According to Lazzarato—with whom Melitopoulos regularly collaborates and whose essay Video loso a. La percezione del tempo nel postfordisme (1996) largely arose from his interest in her work—trying to capture and work with videographic images at the “molecular level,” in a sort of updating of the theories of philosophers such as Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, and Michel Foucault, became the principal leitmotiv of Melitopoulos’s work from then on. Her video essay Passing Drama (1999) is a seminal piece in this respect.

Melitopoulos starts out from the premise that we must appreciate that the world is forever “in course”: it is never there; it is not what it is, but what is happening, and it is therefore only ever revealed to us in fragments, more as an occurrence than a fait accompli or a thing in and of itself. The particular complexity, as well as the disruptive power and experiential and political essence of Melitopoulos’s work, resides in this, her “event-led gaze” a gaze that does not seek to create a representation of the world but rather make the world, as a process in course, run through her work. She does this based on her conviction that video technology, through the possibility of processing and recombining ows of captured images and sounds, can o er an experience of pure perception and serve to “speak of the e ects and processes that occur prior to representation and discourse.”

The artist has often compared her way of understanding and working with video to weaving, whereby she weaves ows as opposed to cotton or woolen threads. These ows might overlap or become tied in knots, creating an image that, as Lazzarato puts it, “is not just a point of detention but a moment from which other ows might depart.” Continuing with the textile metaphor, her works are like giant looms that constantly weave and unweave, requiring viewers to be receptive to and accepting of the fact that there isn’t only one way to relate to them, rather each viewing entails a di erent experience. Melitopoulos de nes this way of working with video, as well as the spatial form she gives her installations, with the procedural and the corporeal put center stage and the idea of displacement—in its multiplicity of senses—playing a fundamental role, as Cine(so)matrix

Passing Drama—which opens the exhibition and is, as mentioned above, a seminal work in terms of the development of her particular poetics—is a video essay about migrant memory that takes her own family history as a starting point: as part of the Greek minority in Turkey in the 1920s, her father’s family felt compelled to emigrate and move to Germany. The speci c way that migrants and refugees relate to their past, present, and future became a key component of her work after that, both as a theme and a methodology.

The procedural dimension and the idea of the journey—in the literal and gurative sense—became central to the projects she developed in the 2000s. It was during this period that she coined the

term “timescape,” a concept that would lend its name to a web-based, multiauthored project she took part in: Timescapes. The video installation Corredor X (2006) emerged as a product of this synergy: a collaboration between video artists and activists from Germany, Serbia, Greece, and Turkey, the work spoke of the impact major European Union transport infrastructure projects have on the land and communities in which they are developed. Melitopoulos’s contribution, Unearthing Disaster I (2013)—about the construction of an open-pit gold mine in Skouries, a forest in Greece— focused on capitalist processes and the unstoppable will to extract.

As Arantzazu Saratxaga Arregi notes, “Melitopoulos’s camera bears witness to the controlling gaze of the vigilant eye.” Her lm The Cell. Antonio Negri and the Prison (2008), which speaks of Antonio Negri’s trials, as well as his escape, detention, and subsequent liberation, exposes the control mechanisms that society prescribes not only to prisoners, but to everyone else besides. Throughout the work, structured as four interconnected chapters, Melitopoulos challenges the conventions of the biographical genre and explores the possibilities for nonlinear narration that the DVD format allows.

Seeking a form of audiovisual experimentation that transcended narrative norms, which she felt only served to legitimize capitalist, colonial, and patriarchal logics, Melitopoulos found herself drawn to Félix Guattari’s concept of “machinic animism.” This theory explores the potential for thinking with decentralized, nonanthropomorphic subjectivity by forming open relationships with all beings and things, as proposed by Walter Benjamin in his essay “On Language as Such and the Language of Man” (1916). Melitopoulos uses extracts from Benjamin’s text in her work The Language of Things (2007), in which she investigates and tries to recreate the “sensorial state of material communality with things” experienced in technology-dependent environments such as theme parks.

The video installations Assemblages (2010) and The Life of Particles (2012), produced in collaboration with Maurizio Lazzarato, are likewise based on the concept of “machinic animism.” In both works, Melitopoulos goes deeper in her experimentation with installations comprised of hybrid devices that allow for a spatial redistribution of sound and visual stimuli. In Brigitta Kuster’s words, these “installed assemblages” allow “audio-vision in motion to be introduced into the space in di erent forms,” enabling Melitopoulos to explore and create new “spaces of performative possibility.” The same goes for The Refrain (2015), which takes Deleuze and Guatarri’s concept of ritornello as its departure point in order to consider the importance of repeated gestures, chants, and words for communities ghting the US military presence on the islands of Okinawa (Japan) and Jeju (South Korea). By basing their resistance struggle on ritual, the inhabitants of both places express and thus preserve the emotional link they have with the territories they are being dispossessed of.

In the two most recent pieces that feature in the show, ZONKEY – Learning to Speak with Earth (2020–2023) and Matri Linear B (an ongoing research project that began in 2021), Melitopoulos further challenges the colonial notion of territory, the extractive culture it is based on, and the visual technologies that support it. The rst piece, a sonic research work developed alongside Kerstin

Schroedinger, seeks to generate a “listening device” based on the sounds that emerge from the rural landscape of the Pulkautal valley, in Lower Austria. The premise is that we need to rekindle our listening relationship to the land, a matrix of hearing and responding to our surrounds that (once again) conceives of landscapes as “speaking landscapes” or “agencies that make pronouncements we need to learn to read.” The same argument underpins Matri Linear B, an artistic investigation that is still underway but has so far produced two pieces—Surfacing Earth (2021) and Revisions (2022)—that feature here.

Through the ten works on display, Cine(so)matrix traces the course of Melitopoulos’s career from 1999 to the present day, making it the most ambitious retrospective of her work ever staged in Spain. By the same token, the exhibition further cements the artist’s relationship with the Museo Reina Sofía, which originated with the museum’s acquisition of Crossings (2017) and Déconnage (2012) for its video-installation collection. The rst work, originally devised for documenta 14 in Athens, featured in Episode 8. Exodus and Communal Life as part of the Museo Reina Sofía’s Communicating Vessels Collection, providing a re ection on the thorny issue of north-south relations in the context of the 2008 recession in Greece. The second work, an earlier piece, is a video essay about linguistic experimentation in Francesc Tosquelles’s psychiatric practice, a work made in conjunction with Maurizio Lazzarato and shown as part of the Museo Reina Sofía’s exhibition Francesc Tosquelles. Like a Sewing Machine in a Wheat Field (2022–2023). The present show seeks to deepen our understanding of Melitopoulos’s artistic practice by a ording us the opportunity not only to see some of her most signi cant projects but also appreciate how her singular way of working with space, sound, and the moving image rst took shape and evolved. Her belief in adopting a self-re exive approach to audiovisual and installation media—whereby a project’s method connects to its themes in an organic way—is duly emphasized, as is her use of procedural and collaborative dynamics. The exhibition is complemented by this publication, a collection of texts that allow us to delve deeper into key components of her work and see just how radical and wide-ranging her mission to challenge dominant narratives has been.

Manuel SegadeDirector of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

PASSAGES AND COLLECTIVE MEMORY

NEW SUBJECTIVITIES AND OTHER POSSIBLE FORMS OF RESISTANCE

ASSEMBLAGES AND ANIMISM

CONNECTIVE LANDSCAPES

Elisabeth von Samsonow, Kerstin Schroedinger, and Brigitta Kuster.

Conversation conducted and edited by Margarita Tsomou

Passing Drama, 1999, 66 mins.

Timescapes/B-Zone (2003–2006); Corridor X, 2006, 80 mins.

Crossings, 2017, 109 mins.

Angela Melitopoulos

Unearthing Disaster I, 2013, 36 mins.

The Cell. Antonio Negri and the Prison, 2008, 121 mins.

Déconnage, 2012, 100 mins.

The Refrain, 2015, 66 mins.

Maurizio Lazzarato

Assemblages, 2010, 71 mins.

The Life of Particles, 2012, 82 mins.

The Language of Things, 2007, 37 mins.

WHEN THE CAMERA EYE DESCENDS INTO THE DEEP EARTH AND SPEAKS IN THE LANGUAGE OF PARTICIPATION: MATRIXIAL WEAVING FOR POLITICAL AUTONOMY

Arantzazu Saratxaga Arregi

Matri Linear B. Part 1: Revisions, 2022, 103 mins.

Matri Linear B. Part 2: Surfacing Earth, 2021, 71 mins.

THE VIDEO PHILOSOPHER

Kerstin Schroedinger

ZONKEY – Learning to Speak with Earth, 2020–2023.

16 Conversation Elisabeth von Samsonow, Conversation conducted

26 Passing Drama

40 Corridor X

58

72 The Insistent Angela Melitopoulos

86 Unearthing Disaster

102 The Cell. Antonio

112

124The Refrain

138 La continuidad

Maurizio Lazzarato

148

Assemblages

158 The Life of Particles

170 The Language

The Refrain

184 When the camera and speak in the matrixial weaving

Arantzazu Saratxaga

200 Matri Linear

218 Matri Linear

234 The Video Philosopher Kerstin Schroedinger

238 Zonkey – Learning

Elisabeth von Samsonow, Kerstin Schroedinger, and Brigitta Kuster. Conversation conducted and edited by

Margarita TsomouTSOMOU: Let’s start with a situational genealogy, that is, with a description of our connection to Angela Melitopoulos and her work—because we meet up with Angela and the lms at the common “Crossings” of various paths . . .

KUSTER: My rst meeting with Angela was through her lm Passing Drama (1999). I had been in Berlin for about a year, traveling with groups, debates, and projects involved in art and politics, and in our shared at we had a VHS cassette of Angela’s recently nished lm. I don’t remember how we got hold of it, it was an informal cut, a sort of black copy, which quickly wore out because I watched the lm over and over again. To cut a long story short: Passing Drama represented at that time—and not only for me—an aesthetic and historical challenge. It was neither simply autobiographical—the topos of subjective, autobiographical narration in lm, especially with respect to minority experiences such as migration or queerness, was only just emerging at the time and shook certain attitudes in Germany toward history with a capital H—nor did it complete and correct an o cial historical narrative. Its fragmented way of weaving microsensations, cutting and connecting threads of temporality, rhythms, small melodies, and expanding durations, the way the lm enlarges textures, brings places, practices, and gestures into play; all of this struck me directly, without my really understanding why or what it was about. And since I couldn’t easily understand “it”—that is, the lm—I simply embarked on the sort of magical dream journey that the cinematic processuality in Passing Drama wrapped me in.

SCHROEDINGER: I have probably known Angela for the shortest time of us all, but very intensely. Of course, I was already familiar with her work before we met. Passing Drama was also very important for me personally in dealing with German history in the post-Nazi period. The link between autobiography and the historical and current political situation is striking, but so too is the link with traveling—or better said, with “being in movement.” This is something we have experienced a great deal together: going to certain places and relating to those places. We have been accompanying each other in this practice since 2019: this “network”—of worlds, people, or landscapes—that Angela weaves by moving from one place to another.

SAMSONOW: Yes, she swoops like an eagle into the center of the action. What was signi cant in our case was the discovery that our mothers had both looked at the same range of hills when they were children, and that we had actually then also gazed at the range of hills—the Samerberg hills (in Germany), to be precise—Angela’s mother comes from. That is a strong connection. Then there is this double story with her—the Greek father, a forced laborer interned in Austria, and the violent story of the migration of her paternal grandmother. And on the other hand there is this Bavarian story, which, even if it doesn’t seem that exciting at rst glance, gains depth with the solidarity inherent in Angela’s view of territorialization. These are the primal scenes of our friendship. And there is something like the “secondary literature” of the whole thing, namely the French intelligentsia, embodied by Eric Alliez and Maurizio Lazzarato, who were already collaborating back then and who met in my apartment in Vienna to write. They brought a woman with them: Angela. At that time, these thinkers were in the vanguard: in any case, maybe that was what they thought themselves. But anyway, we were there, and we had our own story. These were the frames in which we socialized. The poststructuralist nomenclature of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari and Toni Negri, Francesc Tosquelles . . . a constant temptation. My struggle to liberate myself from this consisted of relating my book Anti-Electra: The Radical Totem of the Girl to Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia That interested Angela: How did this Electra appear in this eld that these men had tried to comprehend? I am not an essentialist feminist, but there were thresholds to be crossed for both of us to move beyond this kind of structural temptation. This, then, was the machine opératoire (operative machine) in which we met and got to know one another.

TSOMOU: I also share with Angela, on the one hand, the postmigrant experience and being located in the place called Greece. This is not an identical equation, in the sense of an identity, but one that is mediated by the constant shifts in location in our biographies, which also connect us as embodied experiences. We are also constantly concerned with the question of how to understand, observe, and comprehend the world as nonmen. So that this nomenclature is displaced and no longer has the sole claim to be in a position to comprehend the world. These are methodological questions, more than anything else. Because a narrative that is as di erent as that of the lms is not even the narrative of a myth of origin, or as Brigitta said, not History with a capital H. Not another antithesis or statement.

KUSTER: Yes, exactly. I think it was this cinematic power that led me to Angela, because it was much more than the statements, but maybe more the linguistic sounds, that is, the oral scraps— at the same time a place of change and a source—the sounds, colors, durations, and in ections of the video generators used, which made me travel within the body of Passing Drama. This whole complex of the themes and experiences of the transgenerational chain of ight and migration, which is its subject, from the catastrophe in Asia Minor, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Second World War, deportation and forced labor, etc., to the so-called guest work of the Fordist welfare regime of Western Europe . . . All of this, however, is a story that is never represented, and certainly not told in a linear manner. It is more a suggestive passage, a journey on which one is sent as a spectator, with no clearly de ned starting points or points of return. The lm draws you into this complex by doing something with your perception, through its expansion and contraction,

through its substantiation of signs. Everything is in transition between forgetting, breaking o , and passing on. There is stu like nodes and superimpositions or even recursions all the time . . . I had never seen such a cinematic use of video as a medium of transmission, and it was maybe because I could hardly decipher it that it captivated me so much. Only much later did I realize that Passing Drama had set the tone at that time, radically challenging the conception that the majority society in Germany and Western Europe had of its own foundation and history.

TSOMOU: You, Elisabeth, once said that the lms had “cut open realities,” and Kerstin, you said that with respect to their production methods they follow orders that di er from conventional lm practice in terms of the starting point, how one lms and how one cuts . . .

SAMSONOW: This “cutting open realities” is a form of sublime interpretation at which Angela excels. She challenges the visible, and then something happens; that is, the world answers her. The world becomes extremely epiphanic when Angela is around. Things happen where you think: Who ordered that? Why is this person suddenly talking like that? He had never said anything, then suddenly he explains himself in detail in front of her camera. I don’t think you can explain that with the syntactic means of moving-image analysis. It is more a kind of psychonautism carried out with the aid of a camera. This is what makes these lms so powerful, this total a rmation of the social responsiveness of the world, a world with multiple agents: worlds, and villages, and landscapes and cities, and industries, and streets, and people, birds and bacteria.

KUSTER: They are immediate audiovisual cinematic transmissions. They are linked to memory, but also to the future, in a way that Maurizio Lazzarato has described as asigni cant semiotics. So there is a kind of lm reception that is not necessarily, or certainly not only, conscious viewing, understanding, and reconstruction of meaning.

SCHROEDINGER: Yes! Even in the run-up to their production, there is no form for these lms, they work by enabling complex situations to arise, which then become images. It is, if you like, a kind of order of chaosmosis. The lms become an invitation to the viewers to decide for themselves where to direct their gaze, that is, to arrange things themselves. Her audiovisual installations are usually not only about seeing an image—they are also cinematic and spatial situations into which one enters. One never experiences the same situation twice. This corresponds more to the representability of the world and also has a very musical aspect. She works with rhythms or melodies, as in a process of improvising music.

TSOMOU: Watching a lm with conscious understanding, as you called it, Brigitta, is often not easy given the plurality of viewing possibilities. Because, in addition to the multiscreen installations that Kerstin mentioned, there is rarely only one screen to be looked at but always at least two, plus the spatial division of the images within the room; they are not necessarily placed next to each other. The viewer is not told how to watch the lm, just as the interviewees are not told how to tell the story. There is a level of contingency that nds its order in the searching movement and the things that happen in that movement, rather than there being a discernible cause-and-e ect relationship with the narratives.

KUSTER: I could talk about Crossings (2017), where the indirect presentation, seeing lms en plein milieu, in the cross re of four picture walls or windows, takes one deeper into the earth in time and space. Usually, it’s the appearance of a sound—creaking, cracking, drilling, pounding, banging, rustling, scratching, sweeping, or a song—that makes one turn and move toward an image event, accept it or oppose it. Channeling, monitoring, cargoization, shipping, administration: “Where are we going?” “What has happened?” “Here we are in the land of passages.” When you watch Crossings, you actually have to dance.

SAMSONOW: I think that she actually started using the split screens at an important moment, that is at a point when, in philosophy, the linearity of the ow of consciousness was questioned for the rst time, and one suspected that this nonlinearity could be expressed through the copresence of various currents. In Angela’s work these processes are not identi catory but rather highly disidenti catory: you see that all of these people are singular. How they step in front of the camera and relate their own story within their own space.

TSOMOU: It is not always the same sort of knowledge that appears. It is very rare for the interviewees to appear out of their context in a classic interview situation, they are more often contextualized testimonies. The kind of knowledge that comes from someone having walked across a territory for twenty years is absolute expertise. It is not absolute truth.

SAMSONOW: As a result, her works are often epic, distended. It takes a while to see all of these screens, and one shifts into a comprehensive (?) state in which one develops a compacted understanding, with complex connections and di erent approaches that one pieces together oneself.

TSOMOU: These forms of seeing through the speci c materiality of the lms and the screens naturally also evoke speci c forms of content-related coupling between narratives, themes, and stories. There is, for example, the movement of migration, not only as history but also as a situational experience that is interwoven with the macrostructures of politics, if I understand you correctly, Brigitta.

KUSTER: Yes, the theme of migration is my second meeting ground with Angela, in the exhibition and research projects on the formation of the European borders and the history of migrations that we worked on together. Or questions of the remediation of stories of exile and their transposition into lm. When someone asks her why people migrate, Angela gives an original and astonishing explanation: to avoid becoming stupid. Migration is not merely a hike from A to B, that is, a displacement in space, but also an a rmation of the mobility of life, as opposed to the ction of stagnation. It is about the search for leaps and shifts in sensibilities (i.e., processes of being, forms of perception and creation as poiesis), which permit the formation of alignments. And what if there are no places of refuge, but only places from which to ee?

TSOMOU: Stories and scenes of migration recur constantly, from Passing Drama to Crossings, and I see other predominant aspects of Angela’s political argument that are reiterated: topics like

the capitalist accumulation and appropriation processes of megaprojects, often in connection with extractivist appropriation. From the Baghdad Railway in Corridor X (2006) to the gold mine owned by the Canadian group Eldorado Gold in Skouries in Northern Greece, or the gradual enclosure of territories in Lower Austria or Australia.

SAMSONOW: Absolutely. And her approach always involves a movement of integration. As with Skouries, the Matri Linear B series of lms integrated the narrative into interviews with the participants: How are you? And there too, Angela drew out of the farmers things that I had never heard in all the twenty years I have lived here. I already understood how they feel emotionally neutralized and that this is also a form of displacement, in spite of the fact that they still work on this land and that it belongs to them. This also means that the liberation of small farmers in the nineteenth century has been reversed by this capitalist EU-controlled operation of selfenslavement, even though they own the land. This was really a discovery in the lm. It was just as controversial as the research into Eldorado Gold in Skouries. It created an allegory of these global conditions, a form of antithesis, even: the erosion of this relationship of our farmers with their land, which belongs to them but with which they no longer have a direct relationship, is compared to that of the people in Australia who are ghting to protect their existing relationship with the land but do not own it. It’s incredible to show all this in juxtaposition.

TSOMOU: It is not self-explanatory that a lm about agriculture in Lower Austria and another about Aboriginal land relations in Australia should practically be part of the same series, given our anthropological gaze that determines who speaks to what and who belongs where.

SCHROEDINGER: I believe that the problem lies more in the separations within these territories. They are arti cially imposed. The lms show subtle connections, which maybe go further than the body. Matri Linear B is also very much about dryness, drought, or dust as a physical memory—and this is perceptible in both places, in Austria and in Australia. This is revealed visually, but one might remember how it feels when it’s dusty or dry, or too hot. This also has to do with the fact that the protagonists are not only human beings but also the landscape or the microcosms; the water that is lacking is a protagonist, or the fruits, or the blades of grass. And this reveals the contrast in values: in Lower Austria, the landscape is very beautiful, and the fruits and the archaeological discoveries attest to a kind of wealth that is being assigned increasingly less value. We could see in this a parallel with Aboriginal knowledge, which has been completely devalued by colonialism. And this can be connected with Passing Drama in that it is about genocidal stories that are expanded to a planetary scale. It is Angela’s desire to interview the local people that gives her access to this. Not to come up with a simple answer, but to listen to the “how”: how they describe why the world is so horrendous.

KUSTER: Yes, the layers of transmission that Angela works on communicate more by means of a ective links than through the chronological temporality of history. I think that after Passing Drama, Angela began working more intensely within the space. The gure of the archivist as an archaeologist, the interior of the earth, cosmic issues that might arise from the geological dimension of sedimentation, but also from dislocation, the sudden breaking o of a tectonic layer,

whereupon another layer appears in its place and creates bizarre formations . . . these preoccupations coincide increasingly with Angela’s installation research into agencement. Moving audio-vision is brought into the space in di erent ways, as Angela constantly explores performative “spaces of possibility.” One of the characteristic spaces she has created is certainly the vertical space, which falls and rises over three screens in Assemblages (2010), but there are also the journeys along the Balkan autoputs (in Corridor X and Timescapes/B-Zone). Then, I don’t know . . . Kerstin, Margarita, and Elisabeth, tell me how you see space in the Matri Linear B works . . .

SAMSONOW: These works were created in the context of the Reading the Earth research project, part of our The Dissident Goddesses1 project. It was very clear that this connection between geology and history had to be made, and now the historical moment had come to think in these terms. So, what if we have to take the earth into consideration in every one of our acts? The earth, as it were, as a plan, as a diagram, as an archive. That was the challenge: to imagine not a at layer beneath the earth’s surface but a vertical sequence of layers, to be read semantically. And that is why in the lm there are these attempts at reading with respect to the earth’s surface, cultivation, and archaeology, these attempts at reading that move into verticality and create images from it.

SCHROEDINGER: The music in ZONKEY was also developed in relation with the landscape. It was an attempt to communicate with the earth, a “Learning to Speak with Earth.”2 We thought about how one could contact the earth, through sounds and music. Then we began to work with miking. At rst we thought we would use the basement of Elisabeth’s house as a kind of sound room. If you look at the scaling, these pipes in the basement are arranged side by side, like organ pipes in Pulkautal. But it seemed too big an intervention, and we wanted to listen rst. We set up our instruments in Elisabeth’s basement, and we pointed the microphones toward the exterior and tried to hear what was coming, to respond to it. We were not trying to create music professionally but to nd out, rather like with camerawork, if it is in any way possible to communicate with the earth and to record what happens when we do so.

TSOMOU: I think that the music, which was composed through situational improvisations, bears a similar signature to the images. Elisabeth once said that the images had a pulsating quality. The music is not a soundtrack in the sense that the music is placed over the images; sometimes it is the music that guides an entire scene and it is not the image at all that directs one’s perception. The music is totally e ective, but as a voice that speaks for itself. I think the text also functions in this way. The text is not o -text in that sense. These are streams of consciousness

SCHROEDINGER: I would consider both to be comments, rather than information about the images. In Matri Linear B. Surfacing Earth (2021) the music is our voices. An accompanying comment or speech that happens physically. This means that our bodies are virtually inside the image, even if they are only occasionally visible. They actually determine the images.

TSOMOU: Yes, one can perceive the di erent sound sources, sometimes music but also, as Brigitta said before, cracking, hammering, digging through the earth, a hissing sound, and then the blades of grass that push themselves into the image, or the rocks. And then the construction sites and the

excavators, and over and over again these journeys, this looking out of the car window. All this creates improbable connections or links between the themes and the narratives: between Paleolithic forms of community and contemporary agriculture in Matri Linear B. Revisions, or between the history of gold in Lavrion in ancient Greece and extractivism in the gold mine of Skouries in Crossings

KUSTER: For example, Crossings takes up the questions of movements of ight, of poietic resistance in a longue durée3 of Europeanization on the one hand (through imperial wars, expropriation, accumulation, debt economy, civil war, uprisings, and exile), and on the other hand at the limits of historicity, in the visceral center of our hitherto exclusively planetary existence(s). It is about earth time, that is, the possibility of demarcating the territory of one’s own body from collective embodiments, as some decolonial feminists would say. Capitalism is never just a mode of production, as it says in one part of Crossings, but always also a mode of destruction. And you, you are always right in the middle of this “land of sorrow,” which is revealed cinematically primarily through tracking shots and journeys.

TSOMOU: Or in Corridor X, where the political macrolevel is combined with this whole panorama of subjectivation with which I am only too familiar: The autobahn route to Greece, from Germany, passing through Yugoslavia, along which we Greeks living in Germany all traveled every summer holiday, becomes a road trip. During this road trip we learn how this route became an instrumental pipeline of capitalist domination, playing a frontline role in neocolonial industry. So we drive along the route with her and learn on the way, through testimonies, about the post–Eastern Bloc period, the Yugoslav Wars, traveling to Bismarck’s Baghdad Railway and then back to her brother’s childhood memories of taking the same route. These are yet more layers, or bands, which are both autonomous and connected, side by side or one above the other, in a way that would have been improbable before.

SAMSONOW: It’s actually something like a stacked horizon. For Matri Linear B, Angela said early on that she envisioned a work in which horizons would appear to be stacked, like lines of ships. There is a track, then there is another interpretation, or a story about it. But this interpretation is never an instruction, never the kind of voice-over that usually runs over the images of documentary lms.

KUSTER: Indeed, there are often moments of synchronization, when pots and drums are banged, when singing and shooting happen at once and all the screens are on: but a woman’s voice already rises over and above all that.

SAMSONOW: In Déconnage, the use of the voice was very clear to me. There is an interview with Francesc Tosquelles shown on video, and Jean-Claude Pollack and I keep stopping the video and commenting. It is rather a monstrous triptych, since one is dead and the others are alive and we all speak to each other—but strangely enough also not to each other. It was weird, although at the same time it made sense, because we were responding to someone whose speech had already ended. Unfortunately, Tosquelles was no longer able to answer me. He thought that the best and most sensible thing would be if analytic dialogue took on a rhythm through the regular and

intermittent use of the word merde. We also did something regularly in the lm, maybe a merde, but a bit more prolonged. It’s about understanding or not understanding. Tosquelles’s radical acknowledgement of nonunderstanding made it possible for psychiatric clients to express themselves free from constraint and free from judgment, free from interpretative violence. He speaks with a heavy dialect that is almost impossible to understand, and this was bene cial for the psychiatric patients because they thought, “He’s a bit stupid, he doesn’t understand anything anyway.” So of course, in that respect, it is highly sophisticated how Angela then uses this very way of speaking in dialect. It’s such dazzling comedy, performing a scene with the talking head Tosquelles as three tableaux vivants

SCHROEDINGER: There is no explanation either, just continuous talking. That’s why it’s such fun to listen to and watch.

TSOMOU: It’s a bit like we were saying before. These are not statements. They are something else.

Endnotes

(1) The Dissident Goddesses network is an association of female researchers and artists who are interested in opening up access to paleolithic and neolithic female gurines discovered in Lower Austria in varied and experimental ways; see https://www.tdgn.at/

(2) Learning to Speak with Earth is a research project component of The Dissident Goddesses network; see https://www.tdgn.at/learning-to-speak-with-earth/

(3) Editorial note: A term that literally means “long duration” introduced by the French historian Fernand Braudel. It is used to indicate a perspective on history that extends further into the past than both human memory and the archaeological record so as to incorporate climatology, demography, geology, and oceanology, and chart the e ects of events that occur so slowly as to be imperceptible to those who experience them.

Single-channel video, stereo, 66 mins.

Color, aspect ratio 4:3

VO Greek, German

Subtitles available in English, German, French, and Spanish

The video essay Passing Drama renders a close listening of Angela Melitopoulos’s migration history that was handed down across three generations. “Drama” is the name of a small town in Northern Greece where refugees who had survived the Asia Minor Catastrophe settled down after 1923. Many of their children then became forced laborers in Nazi Germany during World War II and even later guest workers in Germany. Their history was shaped by Turkey, Greece, and Germany’s concealing of historical facts and by the need to forget the traumatic experiences of exodus of these rst and second generations of refugees: ssures and discontinuities gaped open in the transfer of memory, of knowledge, of habits of thinking and living. The forgetting of yesterday was interwoven with the forgetting of the day before yesterday and mingled with forgetting of today. But in their words and stories traces of a collective memory are embodied in their voices: because they uttered and repeated inextinguishable sentences—“sentences like stones”—in various circumstances, they crystallized into song lines about deportation, displacement, and ight. The memories of these migrants contain a truth that does not only apply to them. For what happened to them has also happened to us: a radical change in living one’s memory and one’s time.

The notation of forgetting is expressed in Passing Drama through a woven montage of images that are processed in di erent ways. The farther back in the past that the events took place, the more the image manipulation and montage were processed materially for the narrative. From the multiple manipulations of image speed, di erent degrees of “time abstraction” are attributed to the “generation” of the story accordingly.

Images of industrial looms appear repeatedly between sequences. These images not only provide sociological depictions (many refugees worked in the textile industry) but also function as a paradigm of the lm’s narrative construction.

History appears as industrial machinery that devours minorities on behalf of an invisible majority. In its narration structure, Passing Drama is neither documentary nor ction. Instead, it deals with the choice between polyvocality and unanimity, between shorter or longer vocal phrases, between open and closed logics of a story, which characterizes the refugee story in general. Trauma, dramatic escapes, and survival strategies determine the levels the story is perceived on as constitutive psychologies.

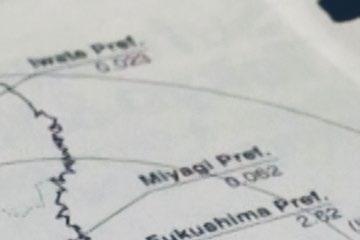

Concept for a collective nonlinear video-editing project between Germany and Turkey

Timescapes/B-Zone was a cooperative nonlinear montage project. Over the course of three years (2003–2006) a group of lmmakers, media activists, and artists from Turkey (the VideA Media Collective from Ankara, Oktay Ince), Greece (Freddy Vianellis), Serbia (Dragana Žarevac), and Germany (Hito Steyerl, Angela Melitopoulos) worked on a collective video database called Timescapes. This image database contained twenty- ve hours of pre-edited raw material on the authors” shared geography.

Initially, every author or author group produced footage for the database independently. The creators” editing rooms were connected via the internet. During the process of montage, edit lists could be saved on a shared web page. Consequently, the process of creation that included editing was simultaneously available from di erent geographical points. This spatial distance was translated into radically artistic ways of seeing becoming evident in the montage. Working via the internet dissolved the division between production and postproduction, between creation and reception: each author remained an active agent in the processing of their material and the inherent spatiality of imagery, and was able to work individually as well as intervene in the work of the others before it was exhibited. Because it depended on this exchange via the internet, Timescapes always entailed the risk of being criticized regarding plot development or composition (for the oversimpli cation of complex processes of subjectivity, for example). The negative matrix of the concept of Timescapes lay in documentary representation, which failed to work through the existing divergences between copy image and mnemonic image.

The videos of Timescapes/B-Zone comprise ve interlinking installations and two single-screen works. The works were all edited from the same data bank material, mostly consisting of the same images and sounds, but depicting—through montage —di erent perspectives on the becoming B-Zone of Southeastern Europe after the Yugoslav Wars.

At the moment of the outbreak of the wars in Yugoslavia in 1992, European Union member states agreed to build up Trans-European Networks (Maastricht Treaty of 1992).

The opening of borders to free passage of persons and goods which today helps to guarantee the economic and social cohesion of the European domestic market, is not only an instrument to spur growth and employment but it is the most important instrument of European eastward expansion which drives capital flow and points the way for future economic policies.

The Trans-European Networks projects have lead to the Pan-European Transport Networks (PETRA) and the TRACECA Programs connecting Europe with China.

These programs are valued to be one of the largest infrastructure projects of the world.

The Trans-European Networks (TEN) comprise three sectors: transport, energy and telecommunications. They primarily consist of ten corridors (Corridor 1-10).

Corridors are not only superhighways but also railway lines, harbours, waterways and pipelines.

The completion of the Trans-European Networks through public-private partnerships (cost estimation 400 billion Euros). It requires investment in research and development, international organizations of experts and the improvement of financial institutions in collaboration with the European Investment Bank.

Corridor X is an interpretation that focuses on the historic and contemporary signi cance of the socialist highway building project Bratsvo i Jedinstvo (Highway of Brotherhood and Unity) in former Yugoslavia. The work is a double-screen road movie recalling a travelogue that formed the collective memory of migration in Western Europe before the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s. The title refers to the 10th Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) Corridor, which is part of the TransEuropean Expansion Program begun in 1993. Departing from Munich via Salzburg, Ljubljana, Zagreb, Belgrade, Niš, Skopje, Veles, Thessaloníki, “Corridor X” was the classic migration route that, before 1990, migrants took in the summer to return to their home countries for holidays.

It highlights expansion through infrastructure projects by the European Union and recalls the socialist past in Southeastern Europe that included concepts of building infrastructure as active constituents of communality. Finally, it describes the situation of a territory where the conditions of mobility have fundamentally changed since 1991. These changes had an impact on how the Southeastern European territory is understood by migrant communities: until the outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars, the autoput (freeway) or the “Highway of Brotherhood and Unity,” had been a collective and transcultural memory-space, a collective traveling experience, an in-between zone or a space of sovereign experience.

In the war the “Highway of Brotherhood and Unity” was destroyed and became a front line in the war itself. After the war the European Union reconstructed the highway as part of the TransEuropean Transport Corridors. As Nebojša Vilić states in the lm: “Why did the EU destroy the highway in the rst place? To reconstruct it?” Ten years after the beginning of the Yugoslav Wars, when the project was recorded, the situation of mobility and migration had fundamentally shifted toward immobility.

The travelogue is composed of images of the travel along Corridor X to Greece and Timescapes data bank images from the Turkish video activist group VideA, which focuses on forced migration in Turkey, providing three case studies: the forced migration of Greeks in Turkey, the forced migration of villagers due to infrastructure projects, and the forced migration of Kurdish people from Hakkari, on the eastern border of Turkey, to Iran.

With raw footage from the Timescapes data bank by VideA (Video Collective Ankara), Freddy Viannelis (Athens), Hito Steyerl (Berlin), Angela Melitopoulos (Cologne)

Two-channel video and ve-channel audio installation, 80 mins. Color, aspect ratio 4:3

VO German, English, Greek Subtitles available in English, and Spanish

There was an idea of connecting people as well.

This place was full of oaks and pine trees

Este lugar estaba lleno de robles y pinos

This place was full of oaks and pine trees

Este lugar estaba lleno de robles y pinos

electrificación más soviética igual a revolución electrification plus soviet equals revolution

they were just puching them south.

Y simplemente los empujaban hacia el sur.

Nos gustaría que estos corredores estuvieran vivos.

We would like all these corridors to be alive.

The new Europe, yes?

La nueva Europa, ¿verdad?

We would like all these corridors to be alive.

The new Europe, yes?

La nueva Europa, ¿verdad?

In collaboration with Angela Anderson (for the images from Skouries, Oreokastro, Mithymna/Lesbos), Pascale Criton (music composition), Maurizio Lazzarato (text), Paula Cobo Guevara (schizoanalytical workshop, Pikpa refugee camp, Lesbos), and Oktay Ince with the Seyri Sokak Video Collective (archival footage Turkey)

Four-channel video and sixteen-channel audio installation, 109 mins.

Color, aspect ratio 16:9

VO English, Greek, Italian

Subtitles available in English, German, and Spanish

* Work not exhibited in Angela Melitopoulos. Cine(so)matrix (Museo Reina Sofía, 2023) exhibition. This work has formed part of the Museum’s Collection since 2018, and it was exhibited in 2022 as part of the Museum Collection’s reorganization, Communicating Vessels.

Crossings composes a narrative about war, forms of slavery past and present, and ecological disasters. It focuses on the delirious conditions of realities that emerge from the current debt crisis in Greece, where capitalism forces neoliberal deregulations and gives rise to civil war against the people. War, destruction, and the experience of a traumatic neoliberal reality is transmitted from body to body, from generation to generation, producing countless voices. These voices are intertwined—they form new groups of expressions.

The display of four screens and sixteen speakers forms a narrative through a linked series of scenes that create tensions and relations with each other.

The scenes include the closure of the borders between Greece and Macedonia in Idomeni in spring 2016, the brutal expulsion of refugees from the harbor of Piraeus, where an extremely vulnerable group of migrants had camped under a highway overpass. Trucks depart from ships there en route to the “Norths.” In these images, money and debt are shown as producing an asymmetrical power relation that ensures creditors retain power over debtors through a civil war “by other means.”

From the stones of the ruins of Corinth, where the money system was invented in ancient Greece, we shift our gaze to the disastrous image of a huge Canadian-owned factory operating in the midst of the pristine Skouries forest, preparing to extract gold from Halkidiki in Northern Greece, thereby transforming social, cultural, and natural societies into an industrial wasteland. During the construction of the mine, Eldorado Gold has already polluted the water and forest so much that the inhabitants” basic economic commons have been destroyed; their futures will be uncertain once this factory nally opens. “They push me to think of terrorism,” an activist voice says.

An experimental schizoanalytical workshop was held in the Pipka refugee camp in Lesbos. This workshop approached the intense traumatizing experiences of border crossing through the work of rendering negatively experienced a ects into speech acts. Crossings combines the audio recordings of this workshop with tracking shots through wire fences on Lesbos. Another workshop was held in Lavrion, where the successfully self-organized Kurdish refugee camp stands in sharp contrast to the destructive organization of EU-led Moria refugee camp.

Crossings follows the becoming-chaotic- eld of a multilayered crisis in Greece (migration, extraction, economy) that demands we rethink our subjectivities and habits.

“Now, now, now . . .” So begins my video essay Passing Drama (1999), the acoustic image of the story of the ight of my grandparents who, like millions of others, had to ee Asia Minor in 1922. For many of these people, the exodus did not end in Greece. Thousands of their children became forced laborers during the Second World War in Nazi Germany and, after the war, “immigrant workers” in Germany. Despite the ongoing denial of the genocides in the Ottoman Empire and in the Turkish Republic up until 1925, and despite the ongoing lack of a reappraisal of the military and political alliances of the German Reich with the Young Turks regime, I was not the only person impelled by these death and migration politics to begin documenting traces, sifting through archives all over the world and experimenting with di erent narratives, with nonlinearity, fragmentations, and image technologies.

In my essay I began to analyze the vocal melodies in the conversations I recorded, in order to work out how oral transmission is shaped from one generation to another. Over time, as I edited the recordings, I began to process the di erent qualities of repression and oblivion; that is, I slowed down and condensed my recordings and arranged them cartographically after generations of transmission.

The act of speaking played a major role in the interviews I conducted. The volitive, nonverbal aspects of the act of speaking, such as voice, intonation, gestures, volume, and body language, produced certain markers within this form of communication: beckoning gestures, heavily weighted phrases, sealed mouths, gestures repeated within victims” families, transmitted from one generation to the next, from one image to another, from one place to another. The text passages were selected from interviews not only for what they said but also for their linguistic melodies, which had become songlike through repetition.

Between 1909 and 1925, several million people were forced into exile from Asia Minor. The remembrance of the missing and of the unidenti ed dead spread throughout the entire world. This remembrance persists.

Passing Drama, then, is a memorial narrative of the exodus of refugees from Asia Minor, structured by the melody of language and electronic image editing. The memories handed down from generation to generation have been shaped by various migratory movements and temporalities. The lm deals with the canon of o cial historiography. Through the combination, layering, and rhythm of text, voice, and image, a metalevel of visualization is written into the editing process. These materializations of the processes of memory are repeated. Like the vocal melodies that unfold as refrains. In keeping with Mikhail Bakhtin’s ideas about dialogue, I regard the volitive elements in speech as revealing cartographic elements; that is, the voice re ects the interlocutor and something of the places and the ideas of the narrator:

The idea lives not in one person’s isolated individual consciousness—if it remains there only, it degenerates and dies. The idea begins to live, that is, to take shape, to develop, to nd and renew its verbal expression, to give birth to new ideas, only when it enters into genuine dialogic relationships with other ideas, with the ideas of others.1

Contextualization through linguistic melodies permits the reconstruction of an event that has been erased by producing a supplementary meaning that places the speaker within the space of the listener, who is addressed in the act of speaking through markers and intonations. These metalevels persist amid the uniformity of oblivion. Milliseconds in gestures, voices, or the repetition of isolated sentences become the texture of a suppressed story, one which the protagonists in Passing Drama assert is true, “which sounds like a fairy tale, but is a true story.” I consider these metalevels to be more real than the surface layers of an anthropocentric present because they also show the break in the narrative, the rupture in the continuity in the story, destruction and transformation of memories by war and ight. No individual stories remain. So I confront the form of the representational image, the nonlinear depicted time, and the in nitesimal elements of volitive perception.

During the three years I spent editing Passing Drama, the most di cult thing was to believe that it was possible to reconnect the fragmented vestiges of such a tragic story into a politically cohesive narrative.

The director of the Sinop Biennial censored Passing Drama in 2020, even though it was then more than twenty years old. Despite the hundreds of years of state death politics in Turkey and the Ottoman Empire, despite the ongoing dark alliance between Germany and Turkey, despite death politics at European borders and the erasure of history, despite the chaotic, unpredictable migratory ows, a few, increasingly rare, acts of witnessing persist and defy oblivion.

Passing Drama begins with the image of vehicles rushing by on a German motorway, lmed horizontally from the side. A voice says: “Now, now, now . . .” Each “now,” exactly a tenth of a second after the image-event of the car speeding past. Suddenly, the horizontally lmed motorway changes to a vertical image. One sees the gray surface of the road with its rhythmic stripes appearing ever nearer and dissolving faster and faster into its skimming details before suddenly transforming into a landscape. A mountain landscape composed of coarse pixels. They move backward and forward. The voice repeats:

Now

Now, now now …

machines, beating with shorter rhythms sensing the passing and so on.

Recording shifts from now to tape. Pushing buttons, past tensed buttons, in gardens of now. Repeating the past without interruption within the necessity to elapse a succession of moments identical to the moment before this way …

Repetition territory, looping for liberation, reading, rereading, reading, from now to the possible to the dreams …

Pasts intrude unremittingly into the oneiric present. Walter Benjamin’s present time is particle-like; it initiates ows and constructs connections between the unrecognizable and the recognizable.

The recording is a trace. Its border forms resonances that spread point by point until their lines create autopoietic layers, superimpositions, mixtures, giving rise to a musical refrain that one slowly begins to understand.

My works Passing Drama, Corridor X, The Cell, Déconnage, and Crossings are about the endless movement of the “great deterritorialized” populations in twentieth-century Europe—the culture of the postnational migrant proletariat. The problem of deterritorializing memory and of forgetting a ects us all, it determines the limits of our perception in general.

The Catalan resistance ghter and founder of institutional psychotherapy, Francesc Tosquelles, stated in an interview, shown in the video installation Déconnage (created with Maurizio Lazzarato, 2011), that war moves beyond and operates outside of the conventions of bourgeois reality. It “is more real than reality; it is hyperreal.” The insistent forms of forgetting through repression and

of the denial of exile, war, and genocide are disseminated throughout the world and become the machinery of a new type of remembrance that connects with other voices and crystallizes new cartographies. The recording/the record/depicted time does not so much represent as connect itself to and indicate a contiguous image.

“What happened?” is the central problem here, a question that eludes established genres and canons. A diversion in time’s being damned to linearity, against the exclusionary mechanics of representation, against the Freudian baseness of the family saga, against national epics, and against the individualistic personal stories of traumatized victims.

For all its density, the present as the densest form of the past cannot neutralize the insistent force of depicted time.2

In the illustration of nonlinear time in Henri Bergson’s book Matière et mémoire (Matter and Memory), the present moment is depicted as Point S, where there is a compact form of accumulated memory of time. The image piles up di erent pasts like layers—A1, A2, B1, B2 . . .— more distant pasts and less distant pasts. For Bergson, the present is the most compact form of past. And there are distended forms of memory time that try to update themselves in the present. A second that occurred years ago becomes an hour in the present. The forces of memory thrust themselves into the present. It is a struggle. This means that narratives can be more open or more condensed depending on these interrelations.

The repetitive and complex hearing of what is actually recorded triggers these di erent temporalities: a yesterday that is connected to the forgetting of the day before yesterday and to the forgetting of today, and, as Benjamin adds to Franz Rosenzweig’s phrase, produces new monstrosities. The recognition of an immediate, magically detailed reality implies connections to something that lies beyond the image, or beyond language. One must begin to think of connectedness as being an “outside” gaze upon the deadly histories of power.

Like the children in Arundhati Roy’s novel The God of Small Things (1997), who are not themselves present on the scene of the story but observe what is happening from outside, through a window: “The God of Loss. The God of Small things. He left no footprints in the sand, no ripples in the water, no images in mirrors.” He is the god of lost things, of personal and everyday things, not the god of history who cruelly forces the “small things” to follow his lead: “Things can change in a day.”3 The melodies of the horizons are landscape rhythms, loosely adapted from Sergei Eisenstein, which magically invoke the kinetic qualities of the camera eye. These metalevels add dynamic potential to the moving image. It could lead us from a detail into a panorama at any moment, or it could become the extraordinary, curative details of eye movement in Aby Warburg’s works. He was able to recognize crazy lists and collections as orders urging him to take more and more time. Time that o ers little, for it is taken from us and relentlessly closes the panoramic window, so that those who have dropped out of history can no longer recognize anything.

It is harder to honor the memory of the nameless than that of the famous. 4

My method of camerawork is relatively autonomous. To some extent it is a situationally based starting position that does not seek to orchestrate the outside but rather to occupy it processually. I became fascinated by the notion of “camérer” developed by the French reform therapists, poets, and militant researchers in the lm group that formed around Fernand Deligny and Josée Manenti, because their cinematic gaze conveyed re ections that refuse objecti cation and behave transversally as subjects. In this way they captured the poetry of the image and integrated this form of seeing into the organization of observation or, as they expressed it, they inhabited their surroundings with their camera.

Every camera image is there before it is captured. It exists as a concept, as a possibility within the process and, in the therapeutic psycho-neurological landscape research of the Deligny cinema group, becomes the image of the rhizome. The viewer’s position as object-subject disappears as a result of duration. The act of seeing articulates its own involvement in the world and produces a perception of intermediate images. A camera eye that inhabits the world does not force the world into representation. It encounters events rather than seizing them; it does not hunt them down but positions itself within that which is recognizable. It creates points of connection within the framework of the complex, vital movements that in uence us. The moment of recording is more important to me than the technical means employed, because what is recognizable depends on my possibilities of action. The greater these possibilities, the more autonomously I can produce images. The “passage,” which for Walter Benjamin, in his analysis of Baudelaire’s poem “Á une passante,” was the signi er of modernity, seems to have somewhat lost its meaning in the presence of “facts.” But modernity is clamorous. It is mesmerizing, a machine trance indicating the slowness of time and, like the exo-view of our own cognitive perspectives, inviting us to move, to change position.

In some of my works, passage is represented visually through the speed of a car journey (Timescapes, Corridor X, Unearthing Disaster). Conversations in cars, which connect us to the moving exterior during the journey, become the background to the statement. Corridor X (2006) integrates the moving background as a double-screen road movie of migrations between Germany and Turkey. On the former “autoput”—the “Highway of Brotherhood and Unity” in former Yugoslavia—fellow travelers who have become friends discuss European expansion, which was promoted by the same countries that agreed on a corridor infrastructure policy and has supported neoliberal policies since the 1993 Maastricht treaty. Transport routes, energy pipelines, and telecommunications technologies in ten so-called European corridors are nanced by “privatepublic partnerships.” Financial and technical know-how are developed along the length of these corridors. Local, autonomous economies are dying out, as became evident after the Yugoslav Wars and later in the wake of the Greek nancial crisis. For this reason, there are lines of continuity between EU expansion policies and the imperial policies of the German Reich in the late nineteenth century.

The Orient Express and the connecting Baghdad Railway were built along the “old” European axis that linked Germany to the Ottoman Empire. This imperial policy moved in the opposite direction of the migration of workers to Western Europe. The collective video editing project Timescapes/B-Zone sought, with this in mind, to address issues of infrastructural politics and the new European subjectivities developed prior to the collapse of the socialist states after the Yugoslav Wars. The idea was to create a joint video database for ve artists/groups working between Germany and Turkey and to invite each participant to use images made by the other participants in their narratives. This process shows what an image, in the absence of knowledge of the context in which it was made, might represent to others. The group, which experimented and organized workshops together for more than two years, addressed these questions. I wanted to understand to what extent the interpretation of my own memory images, which precede the creation of the image itself, is collective, and if those memory images can be shared. This question preoccupied me after the completion of Passing Drama because, as a result of the way that time duration is shaped during editing, a “geo-psychic” viewpoint is always apparent. When all the works were nally shown in a joint exhibition, it became clear to me that our collective memory is, above all, geographically and culturally imprinted. This means that the in uence of the media and societal powers aimed at our brains, our memory, and our attention is a particular, political form of government (noopolitik), which in uences us so strongly, beyond revolutions and individual experiences, that even well-armed image creators are unable to defend themselves from their perspectives.

By employing collective, nonlinear editing, one can geographically coordinate a collective “geo-psyche,” that is, understand at a geographical level the cultural memory that in uences our interpretation of images. So it is a constructed memory. Perspectives within Europe, for example between Germany, the former Yugoslavia, Greece, and Turkey, have hardly changed since the Second World War. In the minds of its inhabitants, “Southeastern Europe” is still considered a “B-zone,” a second-class Europe where experiments with new political operations are conducted in times of crisis. Southeastern Europe sees Germany as the initiator of a new, totalitarian nancial capitalism laid on top of on the history of German imperialism.

In 2022, in our research project “Industries of Denial,” Kerstin Schroedinger and I positioned Europe’s contemporary noopolitik5 in two parallel movements. Against the rushing background of a train journey, the sort often used as rear projection in lms, we talk about the denial and the vestiges of the genocidal eradications in Turkey. We discuss the macropolitical, industrial construction of the Baghdad Railway as a historical project of late nineteenth-century German imperialism and, more generally, infrastructure as a megamachine in postdemocratic countries. We also examine the resilient, connective cultural forces that have managed to escape from these totalitarian governments, or that have become invisible but continue to contradict these narratives.

Thanks to the alienation mechanisms created by the camera eye, I have been able to emancipate myself from the prefabricated viewing habits, prejudices, and false ideas arising from cultural and

geographical stigmatization. The analysis of the volatility of image documents and the composition and superimposition of sequences are “geo-psychic,” analytic, and therapeutic procedures; they convey a time landscape or cinematic cartography of the interspace, between inside and outside, between movement and earth memory.

For this reason, I call my works cine(so)matic cartographies. They are self-organized decentralizing processes in which structures (assemblages) can move into one another. The replay of the recorded moment, the time block experience of a passage, a transversal cut that is subordinated neither to index nor to machine; these elements embody the development of our mechanically animated subjectivity.

These procedures are crucial for environmental policy and for migrational autonomy.

Migration is a persistent aspect of the construction of global, political relationships. It expresses itself beyond the democratic nation-state as a growing symptom of its political exclusions. For Francesc Tosquelles, the right to migrate was a human right. He believed that our thinking directly follows our physical movement. The border regime of the nation-state, which limits and regulates this right, then, is also a way to regulate our thinking. I think that the con ict between nomadic (migrant) and sedentary cultures, as outlined in A Thousand Plateaus, becomes the battle eld of noopolitik in migration. Deleuze and Guattari speci cally postulated a distinction between nomadism and migration. One is a movement with a beginning and an end (migration) and the other a movement without beginning or end (nomadism). This distinction, however, has been criticized as an “ahistorical” representation. The dictum of nomadism, “One never gets anywhere,” today constitutes the matrix of migratory ows.

In my four-channel video and sixteen-channel audio installation Crossings, created within the context of documenta 14 (2017), various crises in European politics in Greece after 2015 are concatenated to form a chaosmotic level of construction. Crossings composes a narrative that tells of war, forms of slavery past and present, and ecological catastrophes in the form of a cartography. This cartography crystallizes the quasi-schizophrenic, delirious conditions of the realities that arose during the Greek debt crisis. Neoliberal deregulations, nancial operations, migration crises, and environmental catastrophes nearly forced the Greek government into civil war against its own people. “ There is no mode of capitalist production that is not at the same time a mode of destruction,” asserts a voice in the spatially composed exhibition area.

The scenes include the closure of the borders between Greece and Macedonia in Idomeni in spring 2016 and the brutal eviction of refugees from the harbor of Piraeus, where a particularly vulnerable group of migrants had camped under the bridge of the highway. Trucks depart from ships there en route to the “Norths.” These images introduce the political history of the monetization of the economy in ancient Corinth. Money and debt is shown as producing an asymmetric power relationship that ensures the continuation of creditors ’ power over debtors through civil war “by other means.” From the stones of its ruins we shift our gaze to the disastrous image of a huge Canadian factory operating in the midst of the pristine Skouries

forest, extracting gold from Halkidiki in Northern Greece, transforming societies, cultures, and the natural world into an industrial wasteland. Eldorado Gold Corporation has already polluted the water and forest so much that basic economic commons for the inhabitants has been destroyed; futures are closed o once this factory nally opens. “They push me to think of terrorism,” a voice says.

A long traveling shot and voices in di erent languages appear, throwing terms like love, hate, envy, or jealousy over the fences and beautiful landscapes of Lesbos. In a schizoanalytical group session, a group of refugees performs a workshop enabling speech acts that express the a ective experiences of their passages. The Moria refugee camp. Unexpected scenes. Fire in the camp, revolt in Lesbos and Oreokastro near Thessaloníki, the desperate struggle in Halkidiki where citizens block the roads to the forest.

The Kurdish refugee camp in Lavrion near Athens is organized on the basis of the articulate political manifesto of a radical egalitarian organization. Daily life in the Kurdish camp is organized through music and dance. The same songs appear in scenes of war in the Kurdish areas in Turkey. The spleen of history made the harbor of Lavrion the meeting point between South and North, between future masters and prisoners of war, forced to become enslaved workers for the biggest silver mine in the classical Athenian period. Deconstructing the myth of democracy in ancient Athens with the slave rebellions in the ancient silver mines in Lavrion in the second century BCE directs us back to Skouries and the neocolonial enterprise of Eldorado Gold orchestrated with the economic fasttrack programs of the European Union and the privatization of public water in Greece.

What constitutes the narrative of the second part of the cartography of Crossings is the dark prospect of the economic recon guration of Northern Greece into an industrial wasteland for the mining of gold, metals, and rare earth minerals. This unwanted future has for years enraged the local populations. They deploy their bodies against special police forces.

War, destruction, and the experience of a traumatic neoliberal reality is transmitted from body to body, from generation to generation, generating countless voices. These voices are intertwined “chaosmotically”—they form new groups of expressions. They create a spirited and dynamic memory, become a refrain of resistance and countermobility, and newly actualize a ects and narratives that migrate back to the capitalist center of German industrial production. These voices work at dissolving the established history of progress from within.

The screens and loudspeaker in Crossings form a chain of scenes, create a doubled or tripled event space, and recover a threefold possibility of perception. A complex, dynamic spatial sound system encourages the observer to move physically in the space so that their gaze can wander from one visual event to the next.

In Crossings one experiences superimposed crises that render visible the autonomy of migrations in the globalized society of control. Migration movements form the inner borders of nation-states. The transnational politics of the so-called postliberal society is the outermost

limit of the nation-state. It reacts directly to a migratory autonomy that is constituted as a continuous, creative movement within social, cultural, and economic environments. Escape comes rst!6 People’s e orts to ee necessitate the reorganization of the controls themselves; control regimes have to react to the new situations created by ight. This e ect of refugee movements does not act as an opposition to the state but produces a new subjectivity that experiences passage as a process, within which new strategies of perception are tested. These constellations do not only pertain to movements of ight. They can also be understood as a subversive and invisible politics that undermines the borders and death politics of sovereign national governments. Rather than a political re ection on the autonomy of migration, there is an overpropagation of antiquated and moribund national-historical narratives. Classi cations and devaluations of migrant and political groups are fueled and new evaluations established that depoliticize the law. Subversive mobility strategies push the state to transform itself beyond existing social commitments. The mobility of migration thus becomes the determining force of the capitalist system. Crossings dialogues with the hypotheses of Francesc Tosquelles, seen in our work Déconnage. Tosquelles’s proclamation of the “human right to vagrancy” is reminiscent of the Marxist historical foundations of the struggle against capitalism and its attempts to immobilize the proletarianized, impoverished, vagrant masses using punitive measures. Tosquelles justi ed his demand for the human right to freedom of movement through his psychiatric research on psychomotor activity and the nervous system in the city of Reus. This “myokinetic” research demonstrated that the brain’s reactions follow the body’s movements in time. In other words, as Tosquelles expressed it, our thoughts always follow our feet. This translates into a political manifesto against the modern mind-body dichotomy. This psychiatric research in Reus laid the foundations for resistance against the mechanisms of standardization in psychiatry, against diagnoses and pathologization, against con nement. This is also the foundation for resistance against the racism and colonialism that characterize modernity. Perception can be determined by “setting foot” somewhere, and this changes our way of thinking. It is a means of resistance against mechanisms of control and their institutionalized organization.

Tosquelles’s analytical model of geo-psychiatry has been described by Brian Massumi as a work of migration. Later, Fernand Deligny would reevaluate the hiking trails of autistic youths in the harsh and desolate landscapes of the Cévennes and turn them into examples of an itinerant migrant work, which for me later became a cine(so)matic cartography or, inspired by Arantzazu Saratxaga, led me to concepts of the matrixial, to a cine-matrixial cojointness, to the connectivity of a transhuman and transmedial reality.7 Not only does machinic animism reverse the perspectives in the subject-object patterns of modernity, it is also open to totemic landscapes of knowledge; it is autopoietic.

Nonlinear lm editing has received little attention with regard to migration and cartographic work. For me, it is both a thought mechanism and an avant-garde model for minority languages through which one can describe the processes of the experience of passage and the geographic and historical milieus in migration. The space of possibility within migrational autonomy and contemporary activist artistic practices intervenes in the transformation of the sociopolitical landscape. It functions through connectivity as a machinic animus. Just as motion triggers the