2024/05/16 – 2024/07/07

2024 MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA MEMORI ARTEAN EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA

ERKIZIA

AIR AIR

XABIER

BURNED

BRÛLÉ

Artist / Artiste : Xabier Erkizia / https://erkizia.audio-lab.org

Exhibition / Exposition :

Installation / Montage : Iñigo Telletxea

Violinist / Violiniste : Maite Larburu

Audiovisual / Audiovisuel :

Audiovisual production / Production audiovisuelle : Aritz Lazkano, Garaxi Taberna Director of photography / Directeur de la photographie : Ekain Albite

Image assistant / Assistant Image : Laia Erkizia

Sound / Son : Xabier Erkizia

Studio / Studio : audio-lab.org

Speech / Discours : Garaxi Taberna, Zaineh Kamel

Acknowledgements / Remerciements : Oier Plaza, Mazen Kerbaj, Carlos F. Cardoso, Zaineh Kamel, Raed Yassen, Hiba Abu Nada, San Telmo Museoa, Astra-Lobak, Museo d’Historia de Sabadell, Museo de Bellas Artes de Álava

Curators / Conservateurs : Ismael Manterola, Andere Larrinaga, Mikel Onandia

Catalogue coordinators / Coordinateurs de catalogues : Iratxe Momoitio Astorkia, Idoia Orbe Narbaiza

Translations / Traductions : Bakun

Graphic design / Conception graphique : goikipedia / info@goikipedia.com / www.goikipedia.com

Edited by / Édité par : Gernika Peace Museum / Musée de la Paix de Gernika

Dates of the exhibition in the Gernika Peace Museum

Dates de l’exposition au Musée de la Paix de Gernika : 2024/05/16 – 2024/07/07

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ

MEMORIARTEAN PROJECT / PROJET MEMORIARTEAN 6 COLLABORATIVE WORK BETWEEN MHLI AND THE MUSEUM 8 COLLABORATION ENTRE LE MHLI ET LE MUSÉE LOOKING BACK 10 REGARDER EN ARRIÈRE ABOUT US / QUI NOUS SOMMES 12 GERNIKA PEACE MUSEUM 14 MUSÉE DE LA PAIX DE GERNIKA HISTORICAL MEMORY IN IBERIAN LITERATURES (MHLI) 18 LA MÉMOIRE HISTORIQUE DANS LES LITTÉRATURES IBÉRIQUES (MHLI) XABIER ERKIZIA MARTIKORENA 20 FOREWORD / AVANT-PROPOS 22 WHAT DOES WAR SOUND LIKE? 24 QUEL BRUIT FAIT LA GUERRE ? EXHIBITION / EXPOSITION 28 INTRODUCTION: 30 INTRODUCTION: CONDUCTING AN ARTISTIC RESEARCH 34 LA RECHERCHE ARTISTIQUE - THE MYTHOLOGY OF MUSIC / MYTHOLOGIE DE LA MUSIQUE 34 - THE HOWLS OF FACTORIES AND THE VOICES OF DANGER / 36 LES HURLEMENTS DES USINES ET LES VOIX DU DANGER - SOUNDS THAT FALL FROM THE SKY / DES SONS TOMBÉS DU CIEL 38 - THE TRUMPETS OF JERICHO / LES TROMPETTES DE JÉRICHO 40 - BOMBS IN THE MOVIES / DES BOMBES DE CINÉMA 42 OBJECTS / OBJETS 44 THE GERNIKA SIREN / SIRÈNE DE GERNIKA 46 THE SAN SEBASTIÁN SIREN / SIRÈNE DE SAINT-SÉBASTIEN 48 TWO TWIN SIRENS / DEUX SIRÈNES JUMELLES 50 BIBLIOGRAPHY / BIBLIOGRAPHI 52 PREVIOUS EXHIBITIONS / EXPOSITIONS PRÉCÉDENTES 56 INDEX SOMMAIRE

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ

20 24

MEMORIARTEAN PROJECT

PROJET MEMORIARTEAN

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

MEMOR RTEan

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 8

COLLABORATIVE

WORK BETWEEN MHLI AND THE MUSEUM

The MemoriArtean project, which started in 2022, is the result of a collaboration agreement between the Gernika Peace Museum and the MHLI (Memoria Histórica en las Literaturas Ibéricas/Historical Memory in Iberian Literature) research group from the University of the Basque Country-UPV/EHU.

This is not the first time the two organisations have worked together. From the moment the MHLI group first participated in the sessions on poetry and memory at the 6th Gernika International Art and Peace Seminar in 2015, to its contribution to the recent virtual round table debate organised by the museum, the two organisations (Gernika Peace Museum and the MHLI) have shared a common aim: to explore and research our conflictive memory of the past.

This is the motivation behind the MemoriArtean project, which will, over the next few years, embark on the joint organisation of exhibitions and seminars aimed at disseminating the work of young Basque artists who have worked or wish to work on this specific topic.

If you are a Basque artist and have an interesting proposal linked to this topic, please contact us so that we can take your idea into account for forthcoming exhibitions and projects.

museoa@gernika-lumo.net

COLLABORATION ENTRE LE MHLI ET LE MUSÉE

Le projet MemoriArtean débute en 2022, fruit de la collaboration entre le Musée de la Paix de Gernika et le groupe de recherche de l’Université du Pays Basque UPV-EHU, MHLI (la Mémoire Historique dans les Littératures Ibériques).

Jusqu’à présent, les collaborations ont été ponctuelles entre le Groupe de Recherche MHLI et le Musée de la Paix de Gernika. De la participation à la VIe Rencontre Internationale d’Art et Paix de Gernika, dans les sessions sur la poésie et la mémoire organisées en 2015, à la table ronde virtuelle organisée par le musée récemment, etc. Les deux organisations (le Musée de la Paix de Gernika et le MHLI) partagent l’objectif de vouloir connaître et étudier la mémoire conflictuelle du passé.

Ils mettent donc en place à cette fin le projet MemoriArtean, qui permettra dans les années à venir l’organisation conjointe d’expositions, de séminaires, etc. dans le but de faire découvrir le travail de jeunes artistes basques qui ont travaillé ou veulent commencer à travailler sur ce thème.

Si vous êtes an artiste basque et vous avez une proposition intéressante à ce sujet, contactez-nous afin que votre éventuelle participation soit prise en compte pour les prochaines expositions ou projets.

museoa@gernika-lumo.net

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024 9

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 10

LOOKING BACK

“With this image designed for the MemoriArtean (Memory+Art) project, we want to take our gaze back, towards our past, as happens when we press the “rewind” button ( ). A critical look at our memory, framed in a temporal and artistic framework, which leads us -in reverse clockwise motion- to revisit our past, to reread the pages of our traumatic history, interpreted by a generation of youth artists.”

REGARDER EN ARRIÈRE

“Avec cette image conçue pour le projet MemoriArtean (Mémoire+Art), nous voulons ramener notre regard vers notre passé, comme cela se produit lorsque nous appuyons sur le bouton “rembobiner”( ). Un regard critique sur notre mémoire, cadré dans un cadre temporel et artistique, qui nous amène -en sens inverse des aiguilles d’une montre- à revisiter notre passé, à relire les pages de notre histoire traumatisante, interprétées par une génération d’artistes jeunes.”

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024 11

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ

20 24

ABOUT US

QUI NOUS SOMMES

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

GERNIKA PEACE MUSEUM

The Gernika Peace Museum opened its doors in The Gernika Peace Museum opened its doors in 1998; therefore, this year, 2023, marks its 25th anniversary. It is a thematic museum dedicated to the culture of peace and the memory, that is inspired by the tragic bombing of Gernika on April 26, 1937.

The permanent exhibition is structured around four axes:

1- What is peace?

A wide selection of ideas, concepts, thoughts and points of view in relation to peace -particularly a contemporary idea- in which peace, to solve conflicts, flourishes in terms of relationships between human beings.

2- What is the legacy that the bombing of Gernika left us?

A reading of the history of Gernika-Lumo and the Spanish Civil War, the air bombardement of Gernika, and the exemplary lesson about peace taught to us by the survivors of this tragic event through their reconciliation with their attackers.

3- The bombing narrated by the people who lived it The witnesses of the bombing of Gernika tell us what happened to them by audiovisual material. This exhibition shows testimonies collected at different historical moments, those compiled by William Smallwood “Egurtxiki” in the 70s and those compiled in 2018 by Gogora, the Institute for Remembrance, Coexistence and Human Rights of the Basque Government.

4- What about Human Rights in the world today?

We take a look at the world through Picasso’s Guernica using human rights as prism to study the current state of peace in the world today.

The Museum has organized several conferences and seminars related to Art and Peace and Art and Memory.

Art and Peace is a project and working line created in Gernika-Lumo (Bizkaia, Euskadi), in the year 2000 by the Gernika Peace Museum Foundation, the Gernika Gogoratuz Foundation and the Gernika Culture House. This joint project has resulted in several international exhibitions and 7 international congresses addressing a wide range of artistic languages (photography, theater, music...). https://www.gernikagogoratuz. org/arte-y-paz/

As for the theme of Art and Memory, there have been several international conferences and seminars organized by the museum in recent years.

These are the books published by the museum and its collaborators, after holding these congresses and meetings:

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 14

MUSÉE DE LA PAIX DE GERNIKA

Le Musée de la Paix de Gernika a ouvert ses portes en 1998 ; cette année, 2023, fête donc son 25e anniversaire. Il s’agit d’un musée thématique dédié à la culture de la paix et à la mémoire qui s’inspire du tragique bombardement de Gernika, le 26 avril 1937.

L’exposition permanente du musée est structurée autour de quatre axes :

1- Qu’est-ce que la paix ?

Vous y trouverez un large éventail d’idées, des concepts, de pensées et d’opinions différentes sur la paix. Une idée contemporaine que la paix, celle qui sert à résoudre les conflits, ressortira particulièrement positive dans les relations entre les gens.

2- Quel héritage nous a laissé le bombardement de Gernika?

Vous y trouverez une explication de l’histoire de Gernika-Lumo et de la Guerre Civile espagnole, de l’épisode du bombardement et une leçon exemplaire de paix que nous transmettent les survivants sur la réconciliation entre les victimes et leurs agresseurs après un évènement si tragique.

3- Le bombardement raconté par ceux qui l’ont vécu Les témoins du bombardement de Gernika nous racontent ce qu’ils ont vécu à travers le contenu audiovisuel. Cette exposition présente des témoignages recueillis à différents moments de l’histoire, ceux compilés par W. Smallwood “Egurtxiki” dans les années 70 et ceux compilés en 2018 par Gogora, l’Institut de la Mémoire, la Cohabitation et de Droits de l´Homme du Gouvernement Basque.

4- Que se passe-t-il actuellement avec les Droits de l’Homme dans le monde?

Un regard sur le monde à travers le “Guernica” de Picasso, à l’aide d’une réflexion sur les Droits de l’Homme (comme prisme) pour observer l’état actuel des droits de l’homme dans le monde.

Le Musée a organisé plusieurs conférences et séminaires sur l’Art et la Paix et l’Art et la Mémoire

Art et Paix est un projet et une ligne de travail créés à Gernika-Lumo (Bizkaia, Pays Basque), dans l’année 2000 par la Fondation Musée de la Paix de Gernika, la Fondation Gernika Gogoratuz et la Maison de la Culture de Gernika. Ce projet de travail commun a donné lieu à plusieurs expositions internationales et 7 rencontres internationales abordant un large éventail de langages artistiques (photographie, théâtre, musique...) https://www. gernikagogoratuz.org/arte-y-paz/

Quant au thème d’Art et de la Mémoire, plusieurs conférences et séminaires internationaux ont été organisés par le musée ces dernières années.

Voici les livres édités par le musée et ses collaborateurs, après avoir tenu ces congrès et rencontres :

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024 15

ABAUNZA, RICARDO; MOMOITIO, IRATXE (coord.) (2000): Berradiskidetzerako artea, Arte hacia la reconciliación Art towards reconciliation. Catálogo de la exposición. Gernika-Lumo. Museo de la Paz y Ayuntamiento de Gernika.

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA (2005): Museos por la Paz. Una contribución al recuerdo, la reconciliación, el arte y La Paz. Actas del V Congreso Internacional de Museos por la Paz. https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/v_congreso_museo_de_la_paz

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; Arte y Derechos Humanos (2007). Colección: Museoak, Bakea eta Giza Eskubideak Bilduma I ISBN: 9788493619008 https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/artea_eta_ giza_eskubideak

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; DIA-TEKHNÉ: Diálogo a través del arte (2010). Colección: Museoak, Bakea eta Giza Eskubideak Bilduma II. ISBN: 9788493619615

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/dia_tekhne_katalogoa

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; La Embarcada Artivista: arterapia y artivismo. (2016). Colección: Museoak, Bakea eta Giza Eskubideak Bilduma III. ISBN: 9788494537912

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/embarcada_itsasoratze_ artibista

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; Memoriarako artea - Arte para la memoria (2017). Colección: Gernika-Lumoko Historia Bilduma; XI. ISBN: 9788494537929

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/libro_arte_para_la_ memoria_-_fundacion_museo_de_la

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; Memorias de guerra, proyectos de paz. Violencias y conflictos entre pasado, presente y futuro (2017) Colección: Gernika-Lumoko Historia Bilduma; XIV. ISBN: 9788494537967 https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/memorias_en_red

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; Memorias de piedra y acero. Los monumentos a las víctimas de la Guerra Civil y del franquismo en Euskadi 1936-2017 (2018). Colección: Gernika-Lumoko Historia Bilduma; XII. ISBN: 978849453795

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/libro_piedra_y_acero

MOMOITIO ASTORKIA, IRATXE (Coord); Arte, Memoria y espacio público (2019) Ajuntament de Granollers. ISBN 978-84-120353-4-6. https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/arte__memoria_y_espacio_ pu_blico_baja

GERNIKA GOGORATUZ; MemoriaLab, encuentros ciudadanos para la construcción social de la memoria (2019). Red Gernika. https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/redgernika_memorialab_n18_cas

FORO DE ASOCIACIONES ET ALII; Afaloste, Convivencia al pil-pil. Laboratorio gastronómico-social (2020)

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/afaloste_libro_ def_20cas_05_11_2020

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 16

ABAUNZA, RICARDO; MOMOITIO, IRATXE (coord.) (2000): Berradiskidetzerako artea, Arte hacia la reconciliación Art towards reconciliation. Catálogo de la exposición. Gernika-Lumo. Museo de la Paz y Ayuntamiento de Gernika.

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA (2005): Museos por la Paz. Una contribución al recuerdo, la reconciliación, el arte y La Paz. Actas del V Congreso Internacional de Museos por la Paz.

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/v_congreso_museo_de_la_paz

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; Arte y Derechos Humanos (2007). Colección: Museoak, Bakea eta Giza Eskubideak Bilduma I ISBN: 9788493619008

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/artea_eta_giza_eskubideak

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; DIA-TEKHNÉ: Diálogo a través del arte (2010). Colección: Museoak, Bakea eta Giza Eskubideak Bilduma II. ISBN: 9788493619615

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/dia_tekhne_katalogoa

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; La Embarcada Artivista: arterapia y artivismo. (2016). Colección: Museoak, Bakea eta Giza Eskubideak Bilduma III ISBN: 9788494537912

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/embarcada_itsasoratze_ artibista

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; Memoriarako artea - Arte para la memoria (2017). Colección: Gernika-Lumoko Historia Bilduma; XI. ISBN: 9788494537929

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/libro_arte_para_la_memoria_-_ fundacion_museo_de_la

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; Memorias de guerra, proyectos de paz. Violencias y conflictos entre pasado, presente y futuro (2017) Colección: Gernika-Lumoko Historia Bilduma; XIV. ISBN: 9788494537967

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/memorias_en_red

FUNDACIÓN MUSEO DE LA PAZ DE GERNIKA; Memorias de piedra y acero. Los monumentos a las víctimas de la Guerra Civil y del franquismo en Euskadi 1936-2017 (2018). Colección: Gernika-Lumoko Historia Bilduma; XII. ISBN: 9788494537950

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/libro_piedra_y_acero

MOMOITIO ASTORKIA, IRATXE (Coord); Arte, Memoria y espacio público.(2019) Ajuntament de Granollers. ISBN 978-84-120353-4-6

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/arte__memoria_y_espacio_pu_ blico_baja

GERNIKA GOGORATUZ; MemoriaLab, encuentros ciudadanos para la construcción social de la memoria (2019). Red Gernika.

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/redgernika_memorialab_n18_cas

FORO DE ASOCIACIONES ET ALII; Afaloste, Convivencia al pil-pil. Laboratorio gastronómico-social (2020)

https://issuu.com/museodelapazdegernika/docs/afaloste_libro_ def_20cas_05_11_2020

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024 17

HISTORICAL MEMORY IN IBERIAN LITERATURES (MHLI)

MHLI (Historical Memory in Iberian Literatures) is the UPV/EHU research group that aims to analyse the artistic representations of historical memory. Since 2013 it has been a consolidated research group made up of 17 members, and to date it has carried out projects and actions funded by the UPV/EHU, the Basque Government and MINECO (www.mhli.net). Since 2013, the research team has been led by Mari Jose Olaziregi Alustiza.

The research group brings together experts from different disciplines (specialists in philological and literary studies, art history, cultural anthropology, etc.) and although its research topic is Basque culture, it has significant external collaborators from the Iberian and international spheres. Thus, experts in the different official languages of the Iberian Peninsula find ways of comparison with Basque cultural expression, always with the representations of historical memory as the main goal.

Among the many projects it has carried out in recent years are the studies on Franco’s censorship, collected in two volumes published in 2019 and 2020 (in the monographic issue of the journal Euskera and in the prestigious publishing house Peter Lang); the seminars on memory and education, held in 2021 at the Palacio Miramar and published in a book in 2022; the congresses on memory or the contributions to the EDIRED macroproject (CSIC). MHLI is a dynamic group that explores the artistic manifestations of the conflicts that have shaken the Basque Country. Its next activity will be the international congress Gernika(k)/ Guernica(s), to be held on 13-14 June in Gernika.

Some of the collective works of the MHLI research group:

AYERBE, MIKEL (Koord.), 2021, Euskal edizioaren hastapen ikerketak. Bilbo: EHU (https://mhli.net/euskal-ediziogintzaren-hastapen-ikerketa/)

GANDARA SORARRAIN, Ana. (arg.), 2022, Euskal liburuaren frankismo osteko zentsura (1975-1983). Bilbo: EHU.

MHLI, 2019, Joan Mari Torrealdairen txokoa (https://mhli.net/joan-maritorrealdairen-txokoa/)

OLAZIREGI, MARI JOSE & OTAEGI, LOURDES (ed.), 2019, Literatura eta Zentsura. Memoria eztabaidatuak, Euskera 63, 2.2 (2018) (ale monografikoa)

OLAZIREGI, MARI JOSE (Koord.), 2019, Euskal edizioaren mundua, (https://mhli.net/project/el-mundo-editorial-vasco-estudio-historico-de-laevoluciondel-campo-s-xix-xxi/ ).

OLAZIREGI, MARI JOSE & OTAEGI, Lourdes (ed.), 2020, Literatura y Censura. Memorias contestadas. Berlin: Peter Lang.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 18

LA MÉMOIRE HISTORIQUE DANS LES LITTÉRATURES IBÉRIQUES (MHLI)

MHLI (Historical Memory in Iberian Literatures) est le groupe de recherche UPV/ EHU qui vise à analyser les représentations artistiques de la mémoire historique. Depuis 2013, il s’agit d’un groupe de recherche consolidé composé de 17 membres, qui a mené à bien des projets et des actions financés par l’UPV/EHU, le gouvernement basque et MINECO (www.mhli.net). Depuis 2013, l’équipe de recherche est dirigée par Mari Jose Olaziregi Alustiza.

Le groupe de recherche réunit des experts de différentes disciplines (spécialistes des études philologiques et littéraires, de l’histoire de l’art, de l’anthropologie culturelle, etc.) et, bien que son thème de recherche soit la culture basque, il compte d’importants collaborateurs externes issus de la sphère ibérique et internationale. Ainsi, les spécialistes des différentes langues officielles de la péninsule ibérique trouvent des points de comparaison avec l’expression culturelle basque, ayant toujours comme objectif principal les représentations de la mémoire historique.

Parmi les nombreux projets qu’il a menés à bien ces dernières années, citons les études sur la censure franquiste, rassemblées dans deux volumes publiés en 2019 et 2020 (dans le numéro monographique de la revue Euskera et dans la prestigieuse maison d’édition Peter Lang) ; les séminaires sur la mémoire et l’éducation, organisés en 2021 au Palais Miramar et publiés dans un livre en 2022 ; les congrès sur la mémoire ou encore les contributions au macroprojet EDIRED (CSIC). MHLI est un groupe dynamique qui explore les manifestations artistiques des conflits qui ont secoué le Pays basque. Sa prochaine activité sera le congrès international Gernika(k)/ Guernica(s), qui se tiendra les 13 et 14 juin à Gernika.

Quelques travaux collectifs du groupe de recherche MHLI :

AYERBE, MIKEL (Coord.), 2021, Euskal edizioaren hastapen ikerketak. Bilbo: EHU (https://mhli.net/euskal-ediziogintzaren-hastapen-ikerketa/)

GANDARA SORARRAIN, Ana. (eds.), 2022, Euskal liburuaren frankismo osteko zentsura (1975-1983). Bilbo: EHU.

MHLI, 2019, Joan Mari Torrealdairen txokoa (https://mhli.net/joan-maritorrealdairen-txokoa/)

OLAZIREGI, MARI JOSE & OTAEGI, LOURDES (eds.), 2019, Literatura eta Zentsura. Memoria eztabaidatuak, Euskera 63, 2.2 (2018) (ale monografikoa)

OLAZIREGI, MARI JOSE (Coord.), 2019, Euskal edizioaren mundua, (https://mhli.net/project/el-mundo-editorial-vasco-estudio-historico-de-laevoluciondel-campo-s-xix-xxi/ ).

OLAZIREGI, MARI JOSE & OTAEGI, Lourdes (eds.), 2020, Literatura y Censura. Memorias contestadas. Berlin: Peter Lang.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024 19

XABIER ERKIZIA MARTIKORENA

Lesaka, 1975

https://erkizia.audio-lab.org/

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 20

Sound artist, freelance researcher, artistic producer, curator and listener, over the past 30 years, Xabier Erkizia has worked in many different fields, always in projects linked to hearing and sound production. In the musical world, he has worked both alone and with a long list of collaborators, always with hybrid and experimental music. In cinema and the performing arts, he has worked as a sound designer on over 100 films and shows, receiving awards for some, and in 2021 he premiered his feature film O GEMER.

His sound installations and other works have been exhibited in a range of different festivals, cultural centres and museums all over the world.

As a curator, he co-directed the ERTZ Bertze Musiken festival (19992017), directed the sound department at the Arteleku contemporary art production centre (2002-2014) and has curated a wide range of other events, seasons and exhibitions, both at home and abroad. He is a member of the AUDIOLAB association.

He also works in the field of education, teaching at the EQZE film school and occasionally collaborating with other schools and universities.

Artiste sonore, chercheur indépendant, réalisateur artistique, curateur et auditeur. Ces 30 dernières années, il a travaillé dans de nombreux domaines sur des projets liés à l’audition et la production sonore. Dans le domaine de la musique, il a travaillé aussi bien en solo qu’avec une longue liste de collaborateurs, toujours avec des musiques hybrides et expérimentales. Dans le monde du cinéma et des arts de la scène, il a exercé en tant qu’ingénieur du son sur plus de 100 films et spectacles, ayant reçu des récompenses pour certains d’entre eux. En 2021, il a sorti son long métrage O GEMER.

Ses installations sonores et d’autres travaux sont exposés dans divers festivals, centres culturels et musées du monde entier.

En tant que curateur, il a été co-directeur du festival ERTZ Bertze Musiken (1999-2017), a dirigé le département sonore du centre de production d’art contemporain Arteleku (2002-2014) et a exercé en qualité de commissaire à d’autres événements, cycles et expositions nationales et étrangères. Il est membre de l’association AUDIOLAB .

Par ailleurs, il travaille dans le domaine de l’éducation, à l’école de cinéma EQZE et occasionnellement en collaboration avec différents établissements scolaires et universités.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

21

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ

20 24

FOREWORD

AVANT-PROPOS

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

WHAT DOES WAR SOUND LIKE?

Xabier Erkizia has tried to answer this question in the exhibition currently on display at the Gernika Peace Museum. The artist noticed that our collective imaginary associated certain noises or sounds with war. For example, the glissando made by bombs when launched from attack aircraft. But where does that sound come from? Is it the real sound that bombs make upon falling? Or is it an acoustic invention developed by filmmakers to help dramatise this moment? Artists can be viewed as surgeons of the images, volumes, spaces and sounds of society. In this case, the artist has painstakingly explored and analysed this process of dissection, finding both well-known parts of the examined object and unexpected ‘tumours’. War has been represented in many different ways, and although most of these representations (and the best-known ones) use the visual medium, other aspects of this depiction (sound representations, for example) are of somewhat more obscure origin. For centuries, humans have depicted war using different artistic disciplines (sculpture and painting, for example) that have endured the test of time. Our eyes are quick to pick up on visual cues, and nowadays, anyone can recreate a war scene thanks to the imaginary developed through photography and cinema. But it is no simple task to trace the historical representations of war that involve other senses.

These questions are much more difficult to answer: What does war taste like? What does war feel like? What does war sound like? For this reason, right from the very beginning, Xabier Erkizia’s work in this exhibition appeared to us to be as difficult as it was novel and interesting. Indeed, the Gernika bombing commemoration ceremony held every year uses the very siren that rang out that fateful day to warn the townsfolk of approaching danger. And this siren formed the starting point of the research work carried out by Erkizia. His archaeological explorations take us back to the mythological sirens of classical antiquity, those half-women-half-bird creatures whose singing would lure sailors to their doom. Indeed, in Greek mythology, singing was thought to herald tragedy. Centuries later, following the Industrial Revolution, a mechanical device developed for a very different purpose was given the name ‘siren’. Its main function was to serve as an acoustic signal marking the time or indicating shift changes in factories. Schools also used sirens for the same noisy purpose. Little by little, this acoustic timepiece spread to other areas outside the labour market, and once people realised how useful it could be to warn of impending danger, its sound became inexorably linked to war. During the Spanish Civil War and World War II, sirens were systematically used to warn of imminent danger and tell civilians to find cover or take refuge in shelters.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 24

QUEL BRUIT FAIT LA GUERRE ?

Xabier Erkizia a tenté de répondre à cette question dans l’exposition qui est présentée au Musée de la Paix de Gernika. L’artiste pressentait que l’imaginaire collectif identifiait certains bruits ou sons à la guerre. Par exemple, le glissando que font les bombes lâchées des avions d’attaque. À propos, d’où vient ce son ? Est-ce le son réel que font les bombes en tombant, ou est-ce une invention sonore du cinéma pour dramatiser la chute d’une bombe ? On peut considérer que les artistes sont les chirurgiens des images, volumes, espaces et sons de la société. Ici, l’artiste s’est arrêté en détail sur le processus de dissection : il a trouvé des parties de l’objet examiné déjà connues et aussi des « tumeurs » inattendues. D’une part, la guerre a été représentée de façons très différentes, le plus souvent visuelles (les plus connues), mais elle en a également eu d’autres (les sonores) dont les origines et l’évolution sont méconnues. Dans les disciplines artistiques qui ont perduré dans le temps, que ce soit la sculpture ou la peinture, l’être humain a rendu la guerre visible pendant des siècles. Les yeux sont rapides et privilégiés pour retenir une représentation. De plus, n’importe qui peut reconstituer la scène d’une guerre grâce à l’imaginaire créé par la photographie et le cinéma. Mais il n’est pas aussi simple de tracer le parcours historique des représentations de la guerre qui sollicitent d’autres sens.

Voici des questions bien plus difficiles à répondre : Quel goût a une guerre ? Quel toucher a une guerre ? Quel bruit fait une guerre ? Pour cette raison, le travail de Xabier Erkizia dans cette exposition nous a semblé dès le début aussi difficile que novateur et intéressant. En effet, les cérémonies de commémoration du bombardement de Gernika utilisent la sirène qui a sonné ce jour-là en signal d’alarme et là était le point de départ de cette étude. La recherche archéologique d’Erkizia nous amènera au personnage mythologique de la sirène de l’Antiquité classique : un être mi-femme et mioiseau qui, par son chant, conduisait les marins au désastre. Le fait est que, dans le récit mythologique grec, le chant présageait la tragédie. Bien plus tard, après la Révolution Industrielle, un appareil mécanique avec d’autres utilités a été identifié par le nom de sirène. Sa fonction principale était celle d’un signal sonore d’horaire ou des changements d’équipe de travail. Dans les établissements scolaires, il est arrivé avec la même fonction bruyante. Progressivement, cet outil sonore aux fonctions horaires est passé du monde du travail à d’autres domaines. Il est devenu utile pour alerter du danger et c’est pourquoi la sirène est restée inexorablement associée à la guerre. Durant la guerre d’Espagne et la Seconde Guerre mondiale, la sirène était systématiquement employée pour alerter du danger imminent et inviter les civils à se mettre à l’abri ou à se cacher dans les refuges.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024 25

However, the artist did not stop at analysing the well-known sound of an airraid siren, he also started wondering whether there were any other sounds that we commonly associate with these attacks, which is how he started analysing the sound of falling bombs. Does this sound also come from mythology, like the sirens themselves? It seems that the dominant mythology of the 20th century has been cinema, which is where we find the other war sound analysed in the exhibition. Those who have lived through an air raid talk about the sound of sirens and the explosions of the bombs themselves, but none of them, not even the survivors of the Gernika bombing, ever mention the whistling sound made by those bombs as they fall from the sky. Xabier Erkizia carried out a study to determine who first decided to turn the glissando into a sound of war, and when and how they did so. During and after World War II, the Hollywood film industry produced a great number of war films and had to invent an audiovisual language for that genre. And this is the language that has remained embedded in our minds as an illustration of war. It does not matter whether or not it is true, since just like the sirens of Greek mythology, the image and sound of tragedy are codified.

Finally, the title of the project, ‘burnt air’, deserves a special mention. We asked earlier what war smelt like. Synaesthesia is an interesting descriptive exercise used by one witness to the Gernika bombing. Since the bombs dropped on the town were designed to set it alight, the townsfolk saw and felt the sky burn, provoking temperatures hot enough to singe the very air. The exhibition encourages us to understand and feel the scope of the destruction wrought.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 26

Ismael Manterola, Andere Larrinaga, Mikel Onandia

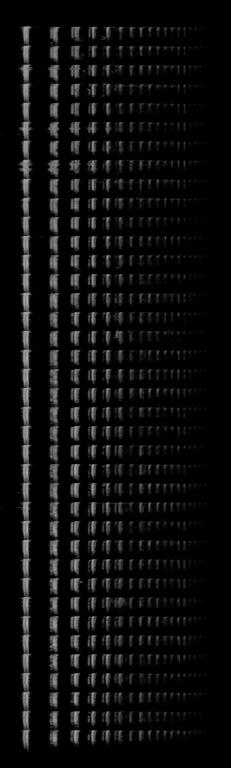

GREAT BRITAIN GRANDE BRETAGNE 1945

GERMANY ALLEMAGNE CA. 1940

DENMARK DANEMARK 2011

DONOSTIA - SAN SEBASTIÁN 2008

FRANCE FRANCE 2022

NORWAY NORVÈGE 2012

Toutefois, l’artiste ne s’est pas simplement contenté du fameux son de la sirène, il s’est demandé s’il existe d’autres sons du bombardement pour retrouver le bruit émis par les bombes lâchées. Peut-être vient-il de la mythologie, comme la sirène ? Le grand mythologue de la seconde moitié du XXe siècle semble avoir été le cinéma, qui est le lieu où l’on peut trouver l’autre son de guerre analysé dans la présente exposition. Les témoins des bombardements, même ceux de Gernika, parlent du son des sirènes et des explosions des bombes, mais ils ne parlent jamais du sifflement des bombes tombant du ciel. Xabier Erkizia a réalisé une étude pour savoir quand, comment et qui a décidé de transformer le glissando en un bruit de guerre. Pendant et après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, le cinéma de Hollywood a produit de nombreux films de guerre et a dû inventer un langage audiovisuel adapté à ce genre, de sorte qu’il s’agit exactement du langage qui est resté gravé dans notre esprit pour illustrer la guerre. Peu importe que ce soit vrai ou faux, à l’instar des sirènes de la mythologie grecque, l’image et le son de la tragédie sont codés.

Enfin, le titre de ce projet interpelle : air brûlé. Dans un premier temps, nous nous sommes demandé quelle est l’odeur de la guerre. La synesthésie est un exercice de description intéressant d’un témoin du bombardement de Gernika. Comme les bombes lâchées sur Gernika avaient pour objectif de mettre le feu, les gens ont vu et senti le ciel s’embraser, atteignant une température suffisante pour brûler l’air. Cette exposition nous invite à connaître et sentir la mesure de la destruction.

Ismael Manterola, Andere Larrinaga, Mikel Onandia

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024 27

SWITZERLAND SUISSE 2016 ISRAEL ISRAEL 2023 SINGAPORE SINGAPOUR 2020 PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES 2020 CHILE CHILI 2015 CHINA CHINE 2008 GERNIKA GERNIKA 1936 - 2024

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ

20 24

EXHIBITION

EXPOSITION

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

INTRODUCTION

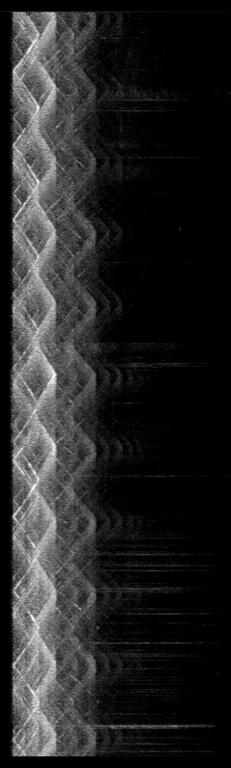

The fact that World War II has been dubbed the ‘War of Noise’ is no mere coincidence. During the Great War, many different technologies based on sound and the phenomenology of sound were invented, built and used: earphones, microphones, sonar, radar, loudspeakers and, of course, radios, which for the first time in history became a fixture in almost every household and played a key role in the trenches on both sides of the conflict. They were first used in the Soviet Union, then in Germany, afterwards throughout Europe and then the rest of the world. Our current sound culture is based on the mass-scale use of radio during that period. We live in the music of those devices.

The terrible attack suffered by Gernika in 1937 was a laboratory for sounds that subsequently reached their maximum expression during the ensuing world war. The technological noises and howling heard in this small town were soon to deafen all of Europe. Among them is one sound that was heard in Gernika for the first time in history, but has since become part of the collective memory of the entire world, mainly thanks to cinema. For the first time, the prototype of the German Junker87 bomber, which took off alongside the Condor Legion, carried a sound device that has gone down in history as a Jericho trumpet1. This noisy device was basically a siren that emitted a howl the sole aim of which was to instil even more fear into the population that was about to be bombed. Unlike in previous aircraft, as the Ju87 (or Stuka) dive bomber (which was able to make vertical turns) gained speed, the siren installed inside it sang out even louder, generating a fatal kind of music that was a harbinger of death.

Although many documents about these noisy artefacts have survived down the years, historians have been unable to find any examples of the objects themselves, causing them to gradually become one of those stories that make up the mythology of modern warfare. The Hollywood film industry, however (whether for strategic or aesthetic purposes) has etched their howl indelibly into our universal memory, although not quite in way we might expect. Regardless of whether or not their stories were set during that terrible conflict, many action movies that were shot after the end of World War II turned the atrocious cry that had sung out all over Europe into the sound of small planes or aircraft, most likely with the sole aim of enhancing the dramatic effect of the sequence and enhancing the sensation of danger. Consequently, for those of us lucky enough not to have had bombs dropped on us from the sky, the death howl invented by the Nazis is now nothing more than the noise made by the engines of the aircraft of

1. Paradoxically enough, according to the Old Testament, it was the Israelites who destroyed the walls of the city of Jericho, today located in Palestine, blowing powerful trumpets as they did so. This is the origin of the name given to these howling sirens.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 30

Le fait que la Seconde Guerre mondiale était appelée la « Guerre du bruit » n’a pas été anodin. Pendant la Grande Guerre, de nombreuses technologies différentes basées sur le son et la phénoménologie sonore ont été inventées, construites et utilisées : casques, microphones, sonars, radars, haut-parleurs et, bien entendu, les radios, qui sont arrivées dans tous les foyers pour la première fois de l’histoire et ont joué un rôle essentiel dans les tranchées de différentes couleurs et idéologies. D’abord, elles ont été employées en Union Soviétique, ensuite en Allemagne, puis partout en Europe, et enfin dans le monde entier. Notre culture sonore actuelle repose sur les utilisations massives de cette époque-là. Nous vivons dans la musique de ces appareils.

Le terrible bombardement vécu par Gernika en 1937 a été un laboratoire de bruits qui a connu son développement maximum dans l’après-guerre. Les bruits et cris technologiques employés rendraient toute l’Europe sourde quelques années plus tard. Parmi eux, il en est un que l’on entendit pour la première fois dans l’histoire à Gernika et qui fait partie depuis de la mémoire collective du monde entier, principalement grâce au cinéma. Pour la première fois, le prototype de l’avion allemand Junker Ju B87, qui a décollé avec la légion Condor, était équipé d’une technologie sonore que les livres d’histoire appelleraient « les trompettes de Jéricho »1. Apparemment, ce dispositif consistait en une sirène qui émettait un cri dont le seul but était d’effrayer encore plus la population à bombarder. Contrairement à d’autres avions antérieurs, au fur et à mesure que le modèle Ju B87 (ou Stuka), capable d’effectuer des rotations sur son axe vertical, volait à de très grandes vitesses, la sirène installée sur l’avion criait de plus en plus fort, produisant une musique horrible qui annonçait la mort.

Si l’on a conservé d’abondants documents sur ces objets bruyants, il ne reste néanmoins pas un seul exemplaire de l’appareil à la disposition des historiens, et au fil des décennies, c’est devenu une de ces histoires passées dans la mythologie des guerres modernes. Le cinéma de Hollywood, en revanche, qui sait si stratégiquement ou pour des raisons esthétiques, a éternisé à jamais ce cri dans la mémoire universelle, et pas comme nous pourrions l’espérer. Beaucoup de films d’action tournés après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, situés ou non pendant la guerre, ont fait du cri atroce qui a traversé l’Europe entière le son de tout petit avion ou aéroplane, sans doute dans le seul objectif de donner plus de dramatisme aux scènes d’action. Pour simplement accroître la sensation de danger. De ce fait, pour les personnes comme nous qui, par chance, n’ont pas été bombardées du ciel, le hurlement de la mort inventé par

1. Paradoxalement, l’Ancien Testament raconte que les Israélites ont abattu les murs de la ville de Jéricho, qui se trouve encore aujourd’hui en territoire palestinien, en jouant des trompettes retentissantes. D’où le nom donné à ces sirènes hurlantes.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

31

INTRODUCTION

yesteryear. What was originally designed as a weapon has been turned by the world of film into nothing more than an epic score.

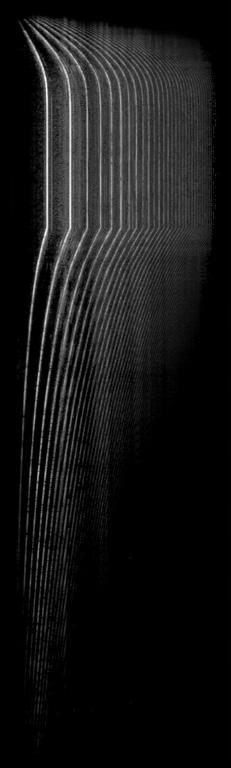

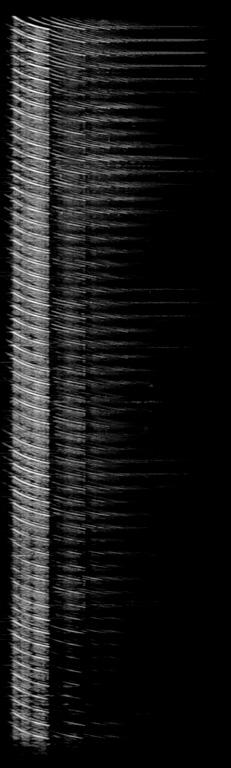

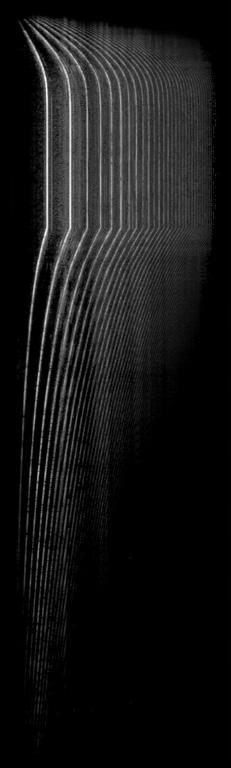

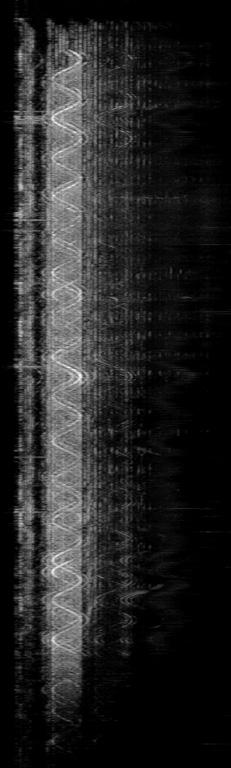

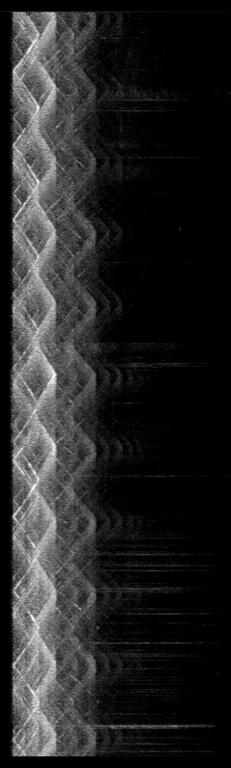

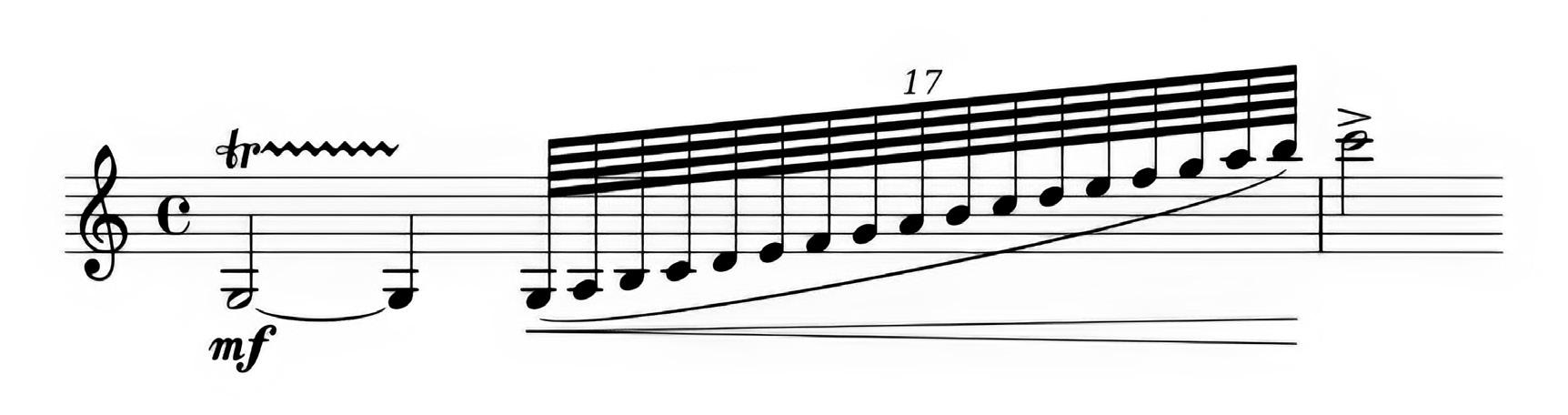

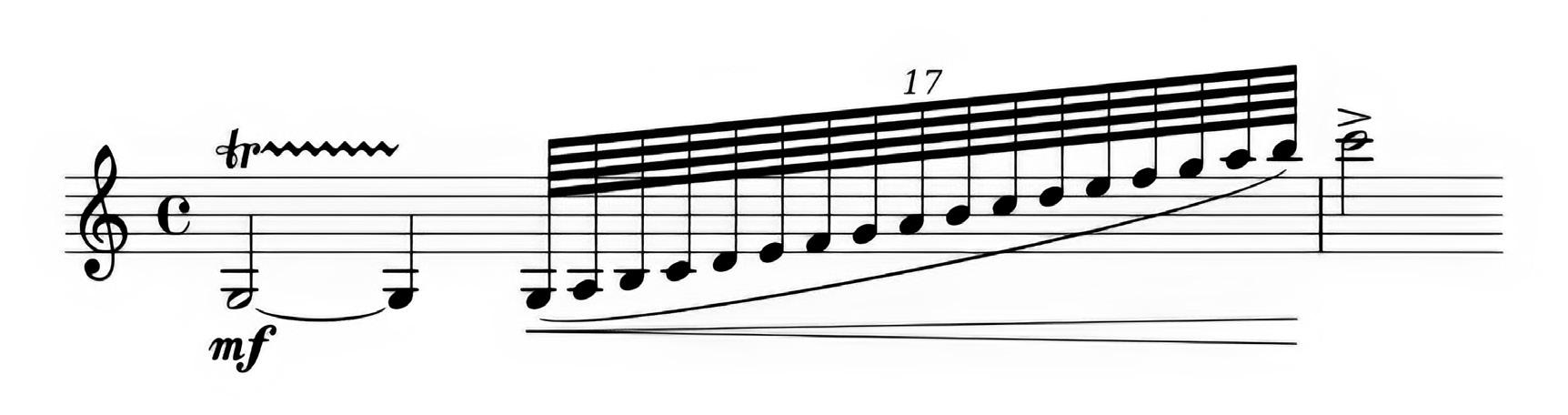

But the story of this death howl does not end here. During the course of the war, the glissando² sounds made by the trumpets of Jericho somehow went from being the siren sounded by approaching bombers to being the whistling of the bombs themselves, constituting (alongside other siren glissandos of World War II) this century’s soundscape of war. And ever since, in our imaginary, planes roar and bombs whistle.

The exhibition uses these two sounds as a starting point for a broader piece of research, exploring first their musical origin (we should not forget that sirens were originally invented as musical instruments, and only later adapted to fulfil other social and warning functions), followed by their mythological references (sirens, sacred sounds, etc.) and finally, their use during the 20th century. By analysing the technological timeline of the past century (sirens, bombs, planes, etc.) and their audiovisual representations (cinema, drawings, animations, videogames, etc.), the research project proposes a kind of forensic analysis of the glissando. The aim is to translate the hackneyed adage ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ and to explore the wealth of narratives hidden behind a single sound, while at the same time building an artistic essay around it. The goal, therefore, is not to generate more sounds (although this is, to some extent, inevitable), but rather to generate new questions by listening critically to certain sounds that are already familiar to us.

2. Playing a glissando on a musical instrument involves gliding from one note to the next, either up or down a scale, rapidly and by sliding your fingers.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 32

les nazis n’est que le bruit de moteur des vieux avions d’antan. Ce qui était une arme à l’origine, le cinéma en a fait une musique épique.

Mais l’histoire de ce hurlement ne s’est pas arrêtée là. Tout au long de la guerre, les sons de glissando2 des trompettes de Jéricho ont passé de la sirène des avions au sifflement des bombes, et celles-ci ont façonné, avec d’autres glissandi des sirènes pendant la IIe Guerre mondiale, le paysage sonore de la guerre du siècle. Depuis, dans notre imaginaire, les avions ronronnent et les bombes sifflent.

Cette proposition d’exposition vise à inclure ces sons comme point de départ d’une étude plus large, en commençant par leur origine musicale (il convient de rappeler que les sirènes ont été inventées à l’origine pour être des instruments de musique, et qu’ensuite elles ont adopté d’autres fonctions sociales et d’alarme), en passant par des références mythologiques (sirènes, sons sacrés...) et en finissant au XXe siècle. Tant à travers la chronologie technologique du siècle (sirènes, bombes, avions...) que ses récits audiovisuels (cinéma, dessins animés, jeux vidéos...), le présent travail de recherche propose une sorte d’analyse médico-légale du glissando. Il s’agit de traduire la phrase répétée trop de fois « une image vaut mille mots » et de faire découvrir la richesse des récits qu’un seul son peut contenir, en même temps qu’un essai artistique est rédigé sur lui. En conséquence, le but n’est pas de produire plus de sons (même si cela arrive forcément), mais de susciter de nouvelles questions en écoutant d’un œil critique quelques sons que nous connaissons déjà.

2. Faire un glissando avec un instrument de musique consiste à faire une échelle ascendante ou descendante pour passer d’une note à une autre ; la distance entre notes se jouerait rapidement et en glissant les doigts.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

33

CONDUCTING AN ARTISTIC RESEARCH

Author unknown. The Siren Vase c.480 BC-470 BC. Greece. The British Museum.

Auteur inconnu. Le vase de la Sirène v.480 BC-470 BC. J.-C., Grèce. The British Museum.

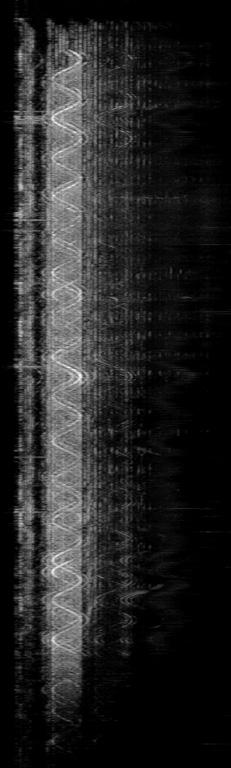

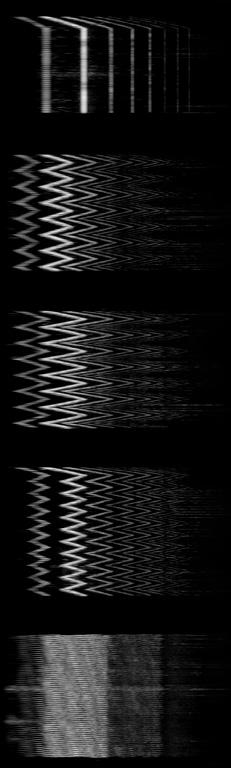

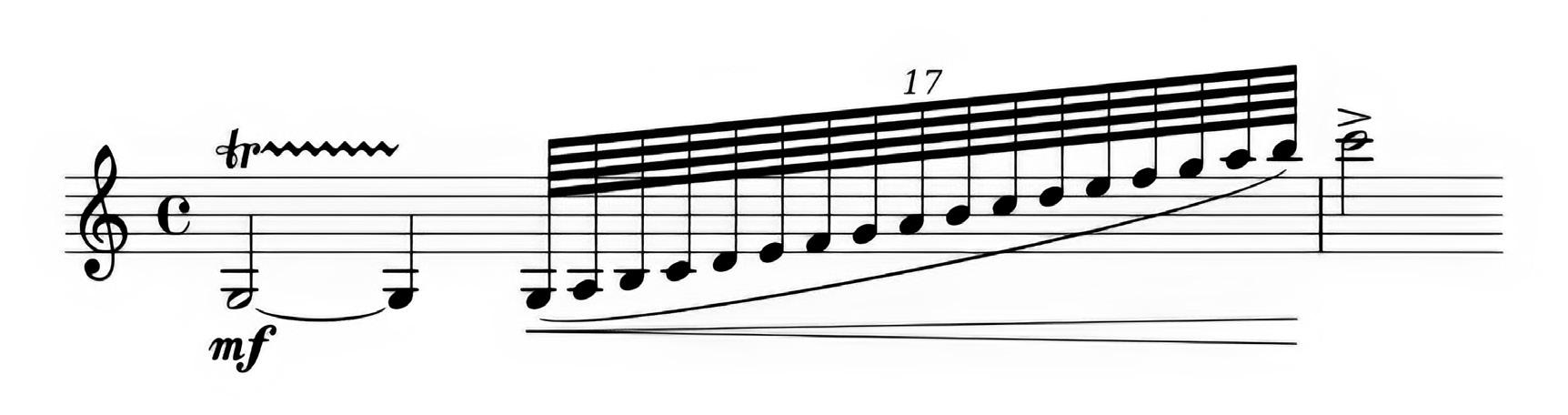

THE MUSIC OF THE MYTHOLOGY

‘Siren’ is not only the name of a monster from classical Greek mythology. Indeed, the mythological being that we imagine today when we think of a mermaid (the word for siren in Spanish also means mermaid) has very little in common with the shrill-voiced bird-women that Homer describes in the Odyssey. Like in all legends from different eras and different places, only a few howls and voices have endured, along with an ancestral warning about the devastating consequences of letting such voices penetrate our psyche. Be careful what (or who) you listen to, because no matter how invisible it may be, it has the power to lure you towards the abyss. Homer was by no means the only one to leave us this written warning, although he may well have been the first (as far as we know, at least). Since then, sirens remain intact in our collective imaginary, as do their songs, which oscillate (in the oddest of ways) between terror-inducing screeches and marvellous melodies impossible to resist.

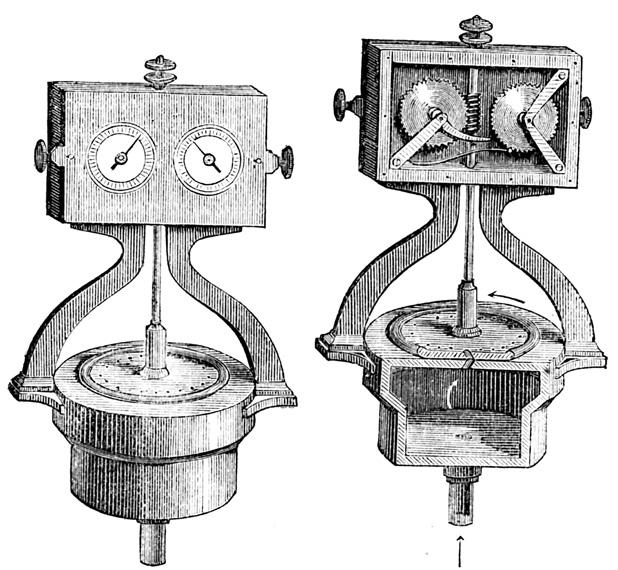

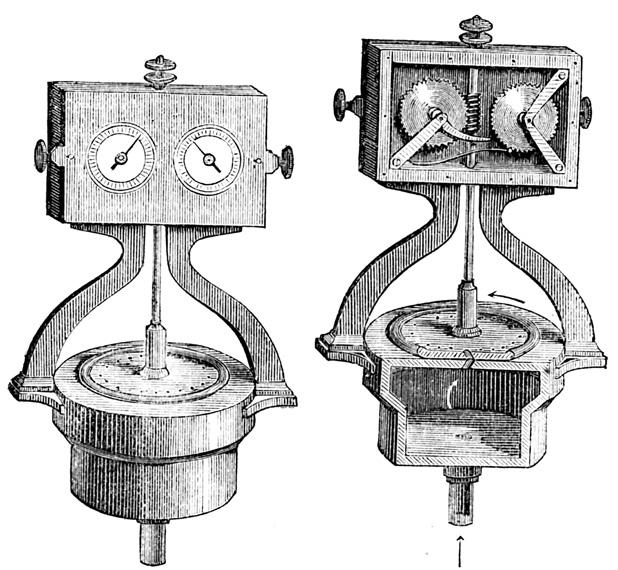

Paradoxically, when the French physicist and engineer Charles Cagniard de la Tour invented the mechanical siren in 1819, he combined both the screeching and the music into what, at first at least, was designed as an innovative musical instrument. His invention had one advantage over the other musical instruments of the era: it was able to create long glissandos, modulated streams of notes with no specific scale or tune, that were extremely strange yet strangely compelling. What he could not have known was that, in just a few years’ time, his innovative instrument would no longer be used to make music, but rather to sound alarms. And worse still, it would later be used to instil utter terror, just like the original screeches of the mythological sirens.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 34

LA RECHERCHE ARTISTIQUE

LA MUSIQUE DE LA MYTHOLOGIE

Sirène est le nom d’un monstre de la mythologie classique grecque, mais pas seulement. Le personnage mythologique que nous imaginons aujourd’hui, cet être mi-humain mipoisson, n’a pas grand-chose à voir avec les femmesoiseaux criardes décrites par Homère dans l’Odyssée. Comme dans toutes les légendes recueillies à des époques et en des lieux différents, seuls des hurlements et des voix ont perduré. Et par-dessus tout, une sorte d’avertissement ancestral sur les conséquences dévastatrices de laisser ces voix entrer dans nos oreilles : Attention à ce que nous entendons, car, aussi invisible soit-il, il a le pouvoir de nous pousser vers l’abîme. Homère n’est en aucune façon le seul à nous avoir laissé ce message écrit, mais en revanche sans doute le premier que nous connaissions. Depuis, les sirènes restent intactes dans notre imaginaire collectif, et surtout, son chant désolant, qui oscille, comme le mélange le plus étrange, entre des hurlements qui nous suscitent la terreur et la musique la plus merveilleuse qui nous procure du plaisir.

Paradoxalement, lorsque le physicien et ingénieur français Charles Cagniard de La Tour a inventé la sirène mécanique en 1819, il a combiné à la fois le hurlement et la musique pour montrer aux gens ce qui au début devait être un instrument de musique innovant. Son invention avait un avantage par rapport aux autres instruments de son époque : sa sirène, comparée aux autres instruments de musique, offrait la manière de faire des glissandi longs, des va-et-vient modulés de notes sans échelle ni accord particulier, qui étaient extrêmement étranges mais très frappants. Ce qu’il ne savait sans doute pas, c’est qu’au bout de quelques années, son instrument de musique innovant ne serait pas utilisé pour jouer de la musique, mais servirait d’alarme. Pis encore, qu’il serait utilisé pour susciter une peur extrême ; comme le faisaient, à l’origine, les hurlements des sirènes mythologiques.

Author unknown. Engraving an early siren. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, no. 270, November 1872.

Auteur inconnu. Gravure d’une sirène ancienne. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, nº 270, novembre 1872.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

35

Luigi Russolo; intonarumori. L’arte dei rumori. Italia, 1913. Luigi Russolo; intonarumori. L’arte dei rumori. Italia, 1913.

Author unknown. Chrysler siren factory plant in Detroit, Michigan, c.1952. Walter P. Chrysler Museum. Auteur inconnu. Usine de sirènes Chrysler à Détroit, Michigan, vers 1952. Musée Walter P. Chrysler.

THE HOWLS OF FACTORIES AND THE VOICES OF DANGER

Over the ensuing century, the first mechanical sirens from the eighteen-hundreds underwent a series of technical and aesthetic transformations. With the exception of the Russian and Italian futurists, few saw any advantage to exploiting the siren’s potential as an original musical instrument, and the industrial revolution soon found a use for it as a functional acoustic signal in factories that were becoming larger and larger by the day. Sirens and their shrill glissando wails were (and still are) perfect for that very specific set of conditions, being of robust construction and capable of generating a sound that passes through all frequencies in the ears of those it is designed to alert. Everyone, even those without perfect hearing, can hear a siren. They almost seem to establish the rules for the limits of human hearing.

Sirens soon proved their efficiency in comparison with the other social acoustic signals that were used during that period (bells, distress rockets, etc.) and quickly spread throughout the modern world, which was immersed in a gradual process of industrialisation. Initially used as an acoustic timekeeper, marking shift changes for factory workers, they soon became a warning signal also, perhaps due to the solemnity and gravitas they bestowed on the message they conveyed. As they spread to other social areas, sirens were mainly used to warn of serious risks and threats outside the workplace, such as fires, evacuations and accidents, and were also installed on ambulances, police vehicles and fire engines.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 36

Author unknown. The siren

Spain. ca. 1936

Auteur inconnu. La sirène. Espagne. ca. 1936.

LES HURLEMENTS DES USINES ET LES VOIX DU DANGER

Les premières sirènes mécaniques du XIXe siècle ont subi au siècle dernier des transformations techniques et esthétiques successives. Au-delà du potentiel d’être un instrument original (sauf dans le cas des futuristes russes ou italiens), la révolution industrielle a trouvé rapidement un usage de la sirène comme signal sonore fonctionnel qui serait utile dans les usines, lesquelles devenaient de plus en plus grandes et bruyantes. La sirène et son glissando remplissaient et continuent de remplir les caractéristiques nécessaires dans une situation comme celle-là : elle est stridente, de fabrication robuste et provoque un balayage de fréquence puissant dans les oreilles qui doivent l’écouter. Elle est conçue pour être entendue par n’importe qui, quelles que soient ses capacités auditives. Il semblerait que les sirènes établissent un modèle des limites de l’audition humaine.

Dès ses débuts, elle a montré une grande efficacité par rapport à d’autres signaux sonores de ce caractère social de l’époque (cloches, fusées) et elle s’est répandue à grande vitesse dans le monde moderne, qui s‘industrialisait peu à peu. Dans un premier temps, elle a servi de marqueur sonore pour fixer les horaires des équipes de travail, et sans doute en raison de la solennité et de l’importance que cet usage lui a donnée, elle est bientôt devenue un signal d’urgence, développant par là même sa fonction sociale. Ainsi, au fur et à mesure que l’usage des sirènes s’est étendu à d’autres sphères sociales, elles ont servi principalement à alerter de dangers graves hors du domaine professionnel : incendies, évacuations, accidents, ambulances, agents de police… ou bombardements

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

37

Author unknown. Federal Thunderbolt siren test. Minneapolis, 1952.

Auteur inconnu. Essai de la sirène fédérale Thunderbolt. Minneapolis, 1952.

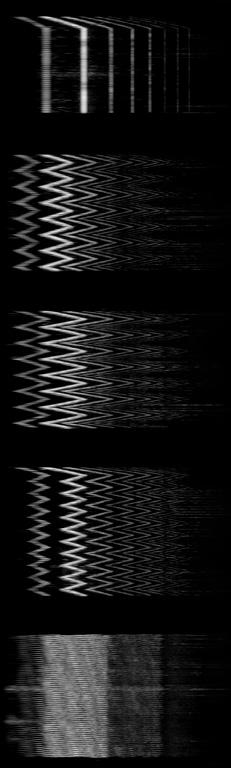

SOUNDS THAT FALL FROM THE SKY

Over the past century, the glissando of the siren’s wail has spread quickly throughout most countries in the world, and with the possible exception of the petrol engine, is perhaps the most universally-recognised globalised sound. A shrill screech, the sound made by sirens has become one of the ‘sacred voices’ defined by R. Murray Schafer. It is a sound that goes beyond the human scale, taking on enormous dimensions and automatically signifying impending atrocity. It is a macro-sound capable of simultaneously instilling both respect and fear. And almost without realising it, we have learned to interpret it in the same way as our ancestors interpreted the roaring of thunder claps or the booming of erupting volcanoes. Even though most of us, and particularly those living in large cities, may think we have become accustomed to all manner of noise, the grave, abstract music of the siren still seduces and oppresses us in equal measure. It still unnerves us. The key to this seemingly intrinsic power may stem from its abusive use of frequencies and volume, although it may equally be due to the acoustic trauma generated by its use during the armed conflicts of the 20th century. Just like those atavistic sounds we call sacred, following World War II, which for the reasons outlined here has often been dubbed the ‘War of Noise’, the sound of war sirens has become inextricably entwined in our minds with danger from the skies, as if referencing some ancient god. It is also the anticipated echo of sudden and inevitable death; a threat to our survival; a prelude to the terrifying symphony of bombs.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 38

DES SONS TOMBÉS DU CIEL

Au siècle dernier, le glissando du hurlement de la sirène est un des sons qui s’est répandu le plus rapidement dans la majorité des pays du monde, et l’on pourrait dire, avec l’autorisation du moteur à essence, qu’il constitue le son mondialisé le plus universel. Comme il s’agit d’un cri toujours strident, la sirène a trouvé sa place parmi les sons que R. Murray Schafer a qualifiés de « voix sacrées ». C’est un son qui dépasse l’échelle humaine, il peut prendre des proportions énormes et, automatiquement, des sens atroces. Un méga-son capable de forcer le respect et la peur dans une même mesure. Et nous, presque sans nous en rendre compte, avons appris à le comprendre avec la même logique que celle avec laquelle nos ancêtres entendaient les grondements du tonnerre et les éruptions de volcan. En particulier dans les grandes villes, même si nous pensons nous être habitués sans problème à son esthétique, la musique abstraite et grave de la sirène est capable à la fois de séduire et d’opprimer soudain nos oreilles avec la même intensité. Elle nous agite encore. La clé de cette puissance, qui semble intrinsèque, pourrait venir de l’abus des fréquences et volumes, ou encore des traumatismes sonores causés par leur présence dans les conflits de guerre que nous avons connus au XXe siècle. À l’exemple de ces sons ataviques que nous appelons sacrés, probablement après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, appelée « Guerre du Bruit » pour les raisons évoquées ici, les sirènes de guerre nous parlent des dangers venant du ciel. Comme s’il s’agissait de dieux ancestraux. En outre, elles sont les échos préliminaires à une mort soudaine et inévitable. Des menaces à la survie. Des préludes aux symphonies terrifiantes des bombes.

Author unknown. Secret acoustic weapon called ‘The Whistle’ from Bell Labs.

Auteur inconnu. Arme acoustique secrète appelée « The Whistle » des laboratoires Bell.

Auteur inconnu. Test de sirène d’alarme. Chicago ca.1944.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

39

Author unknown. Alarm siren test. Chicago ca.1944.

AURELIO ARTETA ; Part of the Triptych of the war (1937-1938).

Scene called “The Front”. Photographic archive of the Museum of Fine Arts of Alava. Provincial Council of Alava. © of the photograph Museum of Fine Arts of Alava.

AURELIO ARTETA ; Partie du Triptyque de la guerre (19371938). Scène intitulée “Le front”. Archives photographiques du musée des Beaux-Arts d’Alava.. Conseil provincial d’Alava. © de la photographie Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Alava.

THE TRUMPETS OF JERICHO

In the Old Testament, Joshua describes the battle of Jericho, the first battle fought in the conquest of Canaan by the Israelites. According to this ancient text, upon finding the gates of Jericho closed against them, the Israelites sounded their trumpets and not only broke down the gates, but also the walls protecting the city. The mere sound of their trumpets caused the walls of the city to collapse.

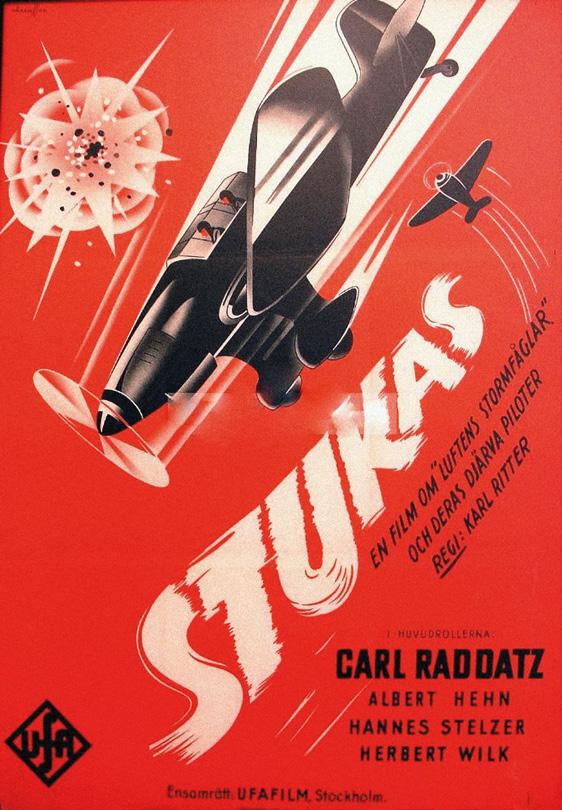

This passage is probably the first reference to acoustic weaponry in written history. It should therefore come as no surprise that research into the acoustic weapons invented and used by the Nazis during World War II has uncovered many such references. Indeed, the Junker B87 dive bombers (known across Europe as Stukas) used during that conflict carried a device named after those same biblical trumpets used by the Israelites at Jericho. Unlike all previous models, Stukas were able to fly vertically. Taking advantage of this novelty, the German army came up with new attack techniques based on selective bombing, with the aim of implementing their battle strategies in a more precise, efficient manner. One of the most macabre protocols established around these aerial weapons involved the mounting of sirens underneath their wings, with the sole purpose of instilling fear into the target population. In comparison with the factory sirens that were familiar to those under attack, Stuka sirens were even shriller and much more strident. They were acoustic knifes with a wicked edge. The discomfort produced by these awful noises was so great that even the pilots complained. But it was precisely this ability to perturb and unsettle that turned them into the principal icons of the soundscape of World War II.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 40

LES TROMPETTES DE JÉRICHO

Dans l’Ancien Testament biblique, Josué décrit la guerre de Jéricho. Il y raconte principalement l’épisode de la conquête de Canaan par Israël. D’après ces anciennes écritures, trouvant les portes de la ville fermées, les Israélites ont sonné les trompettes et ont pris d’assaut non seulement les portes, mais aussi les murs qui protégeaient la ville. Au simple son, les murs de la ville se sont écroulés.

Ce passage est sans doute le premier témoignage des armes acoustiques qui apparaît dans l’histoire écrite de l’être humain. Nous ne serons donc pas surpris de trouver des références et des noms de ce type dans l’étude sur les armes acoustiques inventées et utilisées par les Nazis durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Plus précisément, nous pouvons trouver la mention de Jéricho sur les avions Junker Ju-B87 (connus dans toute l’Europe sous le nom de Stuka) utilisés dans cette guerre, ici convertie en technologie. Ces avions, à la différence de tous les autres modèles jusque-là, avaient la capacité de voler en piqué. Exploitant cette nouveauté, l’armée allemande a conçu de nouvelles techniques d’attaque basées sur des bombardements sélectifs, afin de mettre en œuvre ses stratégies de guerre de façon plus précise et efficace. Parmi les protocoles macabres établis autour d’eux, les Allemands ont installé sous les ailes de ces avions des sirènes avec la simple fonction, apparemment, d’instiller la peur parmi la population. Comparées aux sirènes d’usine que les pays sur le point d’être bombardés prenaient comme un avertissement direct, les sirènes de Stuka étaient encore plus stridentes et nuisibles. Des couteaux de son. Tel était le malaise que produisaient ces bruits, même les pilotes d’avion les censuraient. C’est justement cette capacité à nuire qui les a transformés en icônes majeures du paysage sonore de la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Author unknown. Photo of a Junker B87 aircraft that bombed Maestrazgo. Auteur inconnu. Photo d’un avion Junker B87 qui a bombardé le Maestrazgo

Roger Viollet. Stuka aircraft bombing France, 1940. Roger Viollet. Avion Stuka bombardant la France, 1940.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

41

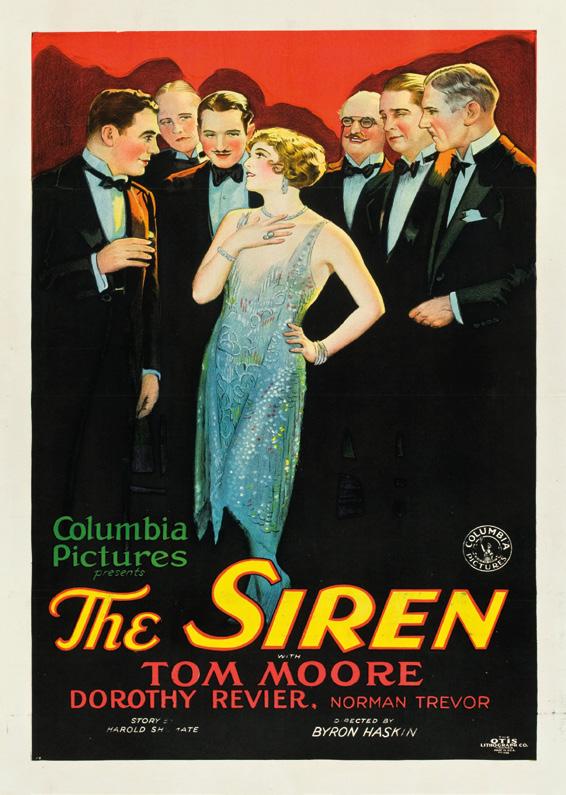

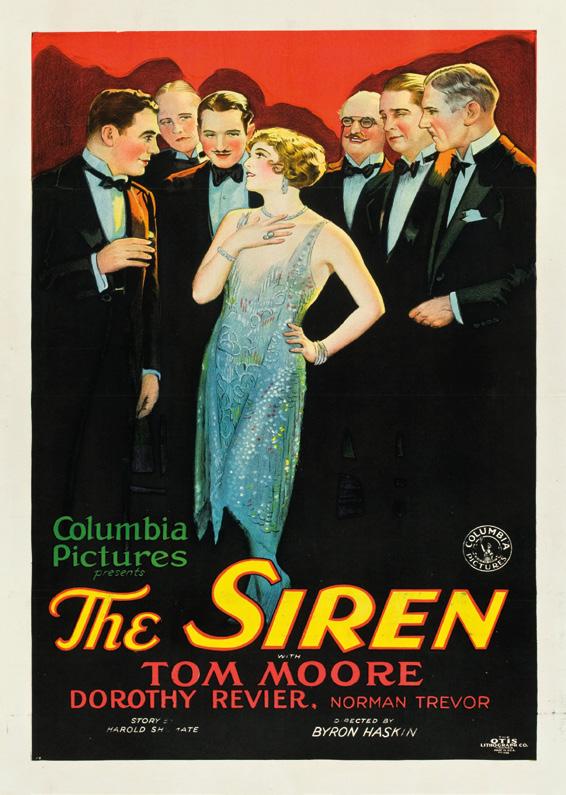

Author unknown. Poster of the film. The siren (Byron Haskin, USA, 1927).

Auteur inconnu. Affiche de film. La sirène (Byron Haskin, USA, 1927).

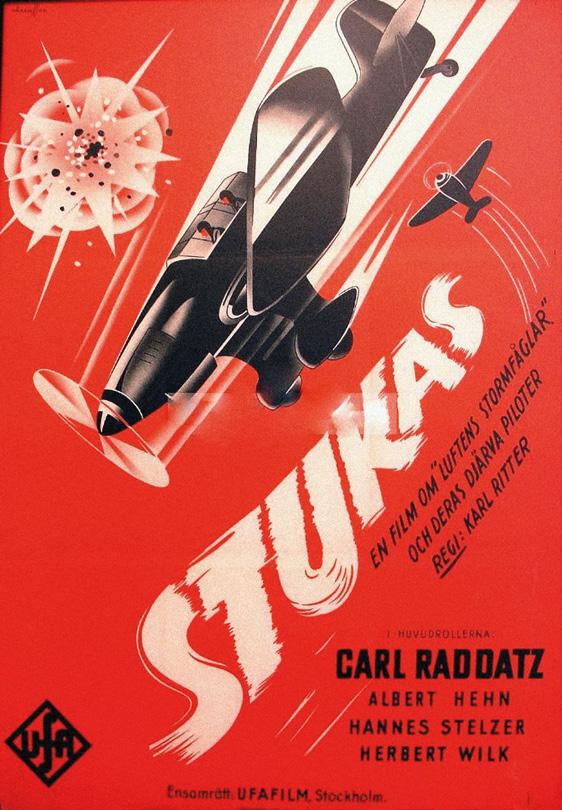

Author unknown. Poster for the film Stukas (Karl Ritler, Germany, 1941).

Auteur inconnu. Affiche du film Stukas (Karl Ritler, Allemagne, 1941).

BOMBS IN THE MOVIES

After the end of World War II, and as the modern conflict known as the Cold War was brewing, the trenches shifted towards other fronts, surpassing physical boundaries to access the symbolic plane. As is so often the case in armed conflicts, as the real explosions died down, the sound of guns and bombs became mere notes in the scores of new altercations based on stories and tales. The Hollywood film industry learned to exploit better than anyone the powerful influences of the noisy music of war. Prompted by the propagandistic aim of spreading the winning narrative throughout the world, these sounds, which had instilled terror in so many during the war itself, were used by filmmakers for their own dramatic ends, until eventually, with the passing of time and the dissipation of the shadow left by the horrific conflict, these cinematographic depictions became hegemonic tales incorporated into recent history. This strategic movement was so effective that our modern-day ears are unable to distinguish between what really happened and the dramatised fictions we see on our screens. Almost like a joke told in very bad taste, the aesthetics of Hollywood imposed the screeching of the Stuka bombers on all aircraft on both sides of the conflict, with the sole purpose of offering audiences a more powerful and terrifying cinema experience. As a result, we have learned that the sound of all aircraft from that era is the roar of the acoustic weapon invented by the Germans. In other words, cinema imposed the Jericho trumpets on all war planes on both sides, thereby obscuring their original meaning and use and consigning them to oblivion.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 42

DES BOMBES DE CINÉMA

Après la fin de la guerre, et alors que s’amorçait le conflit moderne appelé « guerre froide », les tranchées se sont déplacées vers les autres fronts, passant du niveau physique au niveau symbolique. Comme c’est souvent le cas dans tous les conflits, au fur et à mesure que les explosions se taisaient pour de bon, les sons des tirs et des bombes sont devenus les notes des partitions de nouveaux affrontements basés sur des narrations et des récits. L’industrie cinématographique de Hollywood en particulier a exprimé mieux que personne les fortes influences de la musique bruyante de la guerre. Animés par l’objectif propagandiste de partager le récit du vainqueur au monde entier, les cinéastes ont utilisé ces sons, terrifiants durant la guerre, à des fins dramatiques. Puis, au fil des années, l’ombre de la guerre s’éloignant, ces représentations cinématographiques sont devenues des récits hégémoniques de l’histoire récente. Ce mouvement stratégique s’est révélé si efficace qu’il nous est impossible, avec nos oreilles actuelles, de faire la différence entre ce qui s’est réellement passé et la fiction dramatisée du cinéma. Comme une mauvaise blague, l’esthétique de Hollywood, toujours dans l’objectif d’offrir des dramaturgies plus puissantes et terrifiantes aux spectateurs, a imposé aux avions de tout bord les hurlements des avions Stuka. Si bien que ce que nous avons appris comme étant le son des avions de l’époque, c’est le rugissement de l’arme acoustique inventée par les Allemands. En d’autres termes, le cinéma a imposé les trompettes de Jéricho à tous les avions de guerre, sans tenir compte des camps, enterrant totalement leur sens originel et leur utilisation. En les oubliant.

Author unknown. Poster for the film Feuertafe/Bautism of Fire (Hans Bertram, Germany, 1936) Cinema Bilbao. Bilbao, 1940. Auteur inconnu. Affiche du film Feuertafe/Bautisme du feu (Hans Bertram, Allemagne, 1936) Cinema Bilbao. Bilbao, 1940.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

43

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ

20 24

OBJECTS

OBJETS

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

GERNIKA SIREN

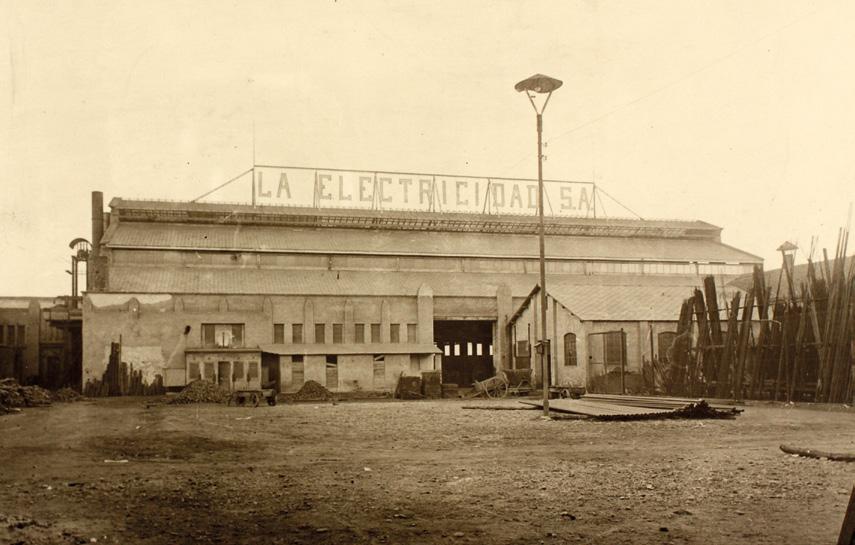

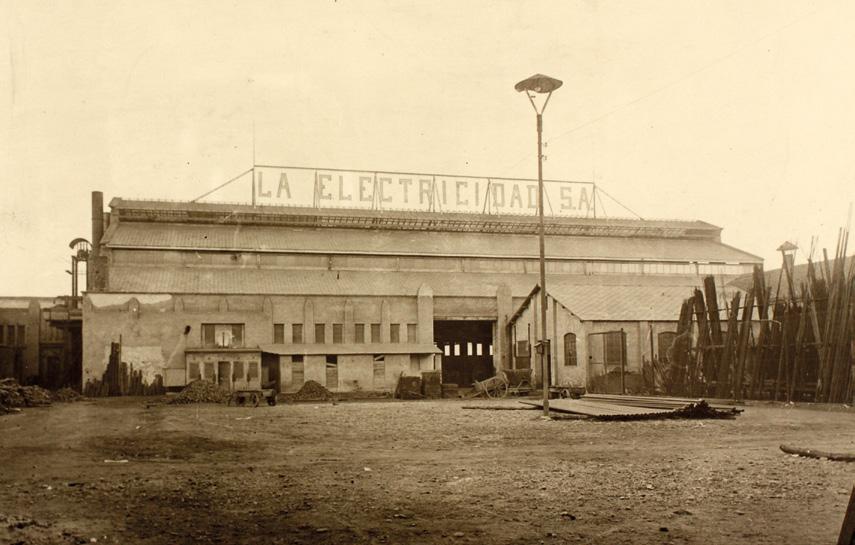

Vertical type air raid alarm siren manufactured by LESA. This is probably the same model manufactured for the Unceta y Cía. Sabadell, September-November 1936. (Author unknown/AHS).

Sirène d’alarme anti-aérienne de type vertical fabriqué par LESA. Il s’agit probablement du même modèle fabriqué pour l’Unceta y Cía. Sabadell, septembre-novembre 1936. (Auteur inconnu/AHS).

This is the siren that, in 1937, warned of the approach of the aircraft that bombed the town that fateful 26 April. It was discovered by a group of youngsters in the Astra building, an old arms factory that still conserved its former name even after the old abandoned edifice was transformed into a cultural centre.

Years later, the Lobak and Gernikazarra associations embarked on a research project to determine whether or not the siren was indeed the same one that sounded that terrible day. After pursuing all surviving references, they contacted the Sabadell History Museum to confirm whether or not it had been manufactured by a local company.

This enabled them to confirm that the siren had indeed been manufactured by what had been one of the leading companies in that Catalonian city (long since closed down), La Electricidad S.A. (LESA), between the summer and winter of 1936, and had subsequently been sold, through a Bilbao-based distributor, to the Astra plant. It is impossible to know, however, whether it was purchased to mark shift changes in the factory or in anticipation of the echoes of war that reached the town just a few months later. Since the completion of the research project, the siren has been used every year on the anniversary of the Gernika bombing, as well as during other commemorative events.

Object on loan from ASTRA-LOBAK for the purpose of this exhibition

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ

46

SIRÈNE DE GERNIKA

Il s’agit d’une sirène qui, en 1937, a donné l’alerte sur les avions venus bombarder Gernika le 26 avril. Elle a été découverte par plusieurs jeunes de la localité dans le bâtiment Astra, un ancien atelier d’armes qui porte encore aujourd’hui le nom de l’entreprise, quand le bâtiment abandonné a été converti en un centre culturel en 2005.

Des années plus tard, les associations Lobak et Gernikazarra ont cherché à déterminer si cette sirène était la même que celle entendue ce jour tragique. Pour ça, d’après les références que gardait la sirène, elles ont contacté le Musée d’Histoire de Sabadell afin de confirmer qu’elle avait été réalisée par une entreprise locale.

Ainsi, on a pu confirmer que la sirène fut construite entre l’été et l’hiver 1936 par l’une des plus grandes entreprises de la ville catalane, la société La Electricidad S.A. (LESA), aujourd’hui disparue, pour être ensuite vendue par l’intermédiaire d’un distributeur de Bilbao à l’usine d’Astra. Nous ne savons pas si la sirène fut achetée pour mettre en place les horaires du personnel ou pour lutter contre les échos sonores de la guerre qui arriveraient directement quelques mois plus tard. Depuis, la sirène est utilisée à l’anniversaire du bombardement de Gernika et à d’autres cérémonies d’hommage.

Objet prêté dans le cadre de cette exposition par ASTRALOBAK.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

ASTRA shelter (Gernika) with the siren at the top. (Photo Hibai Agorria) Abri d’ASTRA, Gernika avec la sirène en haut. (Photo Hibai Agorria)

Siren of Gernika with production number 44.020. (Photo Hibai Agorria)

Sirène de Gernika avec le numéro de production 44.020. (Photo Hibai Agorria)

47

Advertising of LESA alarm sirens. LESA Magazine (EC Electricity) No. 2, March 1937 (Author unknown, AHS).

Publicité pour les sirènes d’alarme LESA. LESA Magazine (EC Electricity) n° 2, mars 1937 (auteur inconnu, AHS).

TWIN SIRENS (GERNIKA AND SABADELL)

During* the war years, the workshops of the company La Electricidad S.A. in Sabadell were to be put at the service of the war industry, specialising in the manufacture of anti-aircraft alarm sirens. Thus, one of these sirens was acquired between September and November 1936 by the gun factory Unceta y Cía of Gernika. This siren was the one that sounded on that fateful 26th April.

Another siren with similar characteristics to the one in Gernika, but a little more powerful, was acquired and installed a few months later on the roof of Sabadell Town Hall (where it remains today).

Today, these two sirens, full of historical and technological memory and of great heritage value, serve to unite both cities (Gernika-Sabadell) in their claim for peace, reconciliation, solidarity, justice and social equality.

* GENÍS RiBÉ MONGE (Comisario). Párrafo extraído del artículo de la exposición “Sabadell-Guernica 1936-1937: Dues sirenes quasi germanes” (Any I Número 0. Sabadell 18 de maig 2017) gracias a la colaboración del Museo d’Historia de Sabadell.

https://issuu.com/museusabadell/docs/diari_sabadell_guernica

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 48

DEUX SIRÈNES JUMELLES

(GERNIKA ET SABADELL)

Pendant* les années de guerre, les ateliers de l’entreprise

La Electricidad S.A. de Sabadell vont être mis au service de l’industrie de guerre, spécialisée dans la fabrication de sirènes d’alarme antiaérienne. C’est ainsi qu’entre septembre et novembre 1936, l’usine de canons Unceta y Cía de Gernika acquiert une de ces sirènes, celle qui retentit ce funeste 26 avril.

Une autre sirène aux caractéristiques similaires à celle de Gernika, mais légèrement plus puissante, a été achetée et installée quelques mois plus tard sur le toit de la mairie de Sabadell (où elle se trouve encore aujourd’hui).

Aujourd’hui, ces deux sirènes, chargées de mémoire historique et technologique, et d’une grande valeur patrimoniale, servent à unir les deux villes (GernikaSabadell) dans leur revendication de paix, de réconciliation, de solidarité, de justice et d’égalité sociale

* GENÍS RIBÉ MONGE (commissaire). Paragraphe extrait de l’article “Sabadell-Guernica 1936-1937 : Dues sirenes quasi germanes” (Année I Numéro 0. Sabadell 18 mai 2017) grâce à la collaboration du Museo d’Historia de Sabadell.

https://issuu.com/museusabadell/docs/diari_sabadell_guernica

LESA factory, Sabadell, 1920s (Unknown author, AHS).

Usine LESA, Sabadell, années 1920 (auteur inconnu, AHS).

Sabadell siren in its original location, installed in August 1937 on the roof of the Town Hall. It has the production number 25.673 (Cese Prat/Ajuntament de Sabadell). Photo Genís Ribe Monge/Ajuntament de Sabadell-Museu d’Historia de Sabadell.

Sirène de Sabadell à son emplacement d’origine, installée en août 1937 sur le toit de l’hôtel de ville. Elle porte le numéro de fabrication 25.673 (Cese Prat/Ajuntament de Sabadell). Photo Genís Ribe Monge/ Ajuntament de Sabadell-Museu d’Historia de Sabadell.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

49

SAN SEBASTIÁN SIREN

A tiny cannon clock with a lens mounted on a marble stand engraved with a numbered circle (from 1 to 7 and from 1 to 10). At midday, when the sun was at its highest, the sun’s rays passed through the lens into a small orifice (ear) in the cannon in which a small amount of gunpowder had been placed, triggering its detonation at twelve o’clock sharp.

In the centre of San Sebastián, an air-raid siren sounds every day at 12 o’clock midday. However, the origin of this siren is not, as one might think, associated with war, but is rather social in nature. The newspaper El Pueblo Vasco, which used to have its headquarters in Garibay Street, set up the siren in 1930 to inform its workers that lunch hour had arrived. When the Spanish Civil War broke out, the newspaper moved to other premises, but the siren remained, now under the care of a watchmaking firm called Relojería Internacional.

But the origins of this social sound-based message that today forms an integral part of the life of all citizens of San Sebastián are much older. From 1878 to 1880, in Gipuzkoa Square, very close to the street in which the siren is located, a small mechanical cannon used to sound at 12 o’clock midday.

In 1905, the cannon disappeared without a trace. A new one was made, but the residents of the area did not like it as much and it was soon removed from the city centre, to be replaced by the siren.

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 50

Object on loan from the San Telmo Museum for the purpose of this exhibition.

Objet prêté dans le cadre de cette exposition par le Musée San Telmo.

SIRÈNE DE SAINT-SÉBASTIEN

Cadran solaire petit canon à loupe sur socle de marbre où apparaît gravé un cercle avec des chiffres (1 à 7 et 1 à 10). À midi, lorsque le soleil atteignait son zénith, cette loupe concentrait les rayons du soleil en un petit trou (oreille) du canon où l’on déposait une portion de poudre pour déclencher sa détonation à midi.

Au centre de Saint-Sébastien, une sirène antiaérienne se déclenche tous les jours à midi. Cependant, l’origine de cette sirène n’est pas belliqueuse comme on pourrait le croire, mais sociale. Le journal El Pueblo Vasco, situé à l’époque dans la rue Garibay, l’a installée en 1930 pour informer ses employés de l’heure du déjeuner. Au début de la Guerre civile, bien que la rédaction du journal changeât d’adresse, la sirène resta au même endroit, confiée aux soins de la boutique Relojería Internacional.

Mais l’origine de ce message sonore social que les habitants de Saint-Sébastien ont pleinement assimilé dans leur vie de tous les jours est encore plus ancienne. Entre 1878-1880, à côté de la rue où se trouve aujourd’hui la sirène, sur la place de Gipuzkoa, un petit canon mécanique indiquait midi.

En 1905, le petit canon a disparu sans laisser de trace. Un deuxième a été installé, mais apparemment il ne plaisait pas autant aux voisins, si bien que le canon a disparu une fois pour toutes du centre de la ville, remplacé par la sirène.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

51

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ

20 24

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

AUDINT - VVAA; Unsound: Undead, Berlin, Urbanomic/Art Editions, 2019

ABU HAMDAN, Lawrence; Dirty Evidence, Milano, Lenz Press, 2022.

BIRDSALL, Carol; Nazi Soundscapes: Sound, Technology and Urban Space in Germany, 1933-1945. Amsterdam, Amsterdam Univerity Press, 2012

BULL, Michael; Sirens (The Study of Sound), London, Bloomsbury, 2020

CARRUTHERS, Bob; The Stuka: Trumpets of Jericho, London, Coda books, 2012

GOODALE, Greg; Sonic Persuasion: Reading Sound in the Recorded Age, Chicago, University of Illinois Press, 2020

PROCHNIK, George; Listening to sirens, Cabinet magazine, 2011 https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/41/prochnik.php

VERNNOIJ, Eveline; ORCALLI, Angelo; FABBRO, Franco; CRESCENTINI, Cristiano, Listening to the Shepard-Risset Glissando: the Relationship between Emotional Response, Disruption of Equilibrium, and Personality (en cursiva), Udine, Front. Psychol. Sec. Cognition Volume 7, 2016

WEIZMAN, Eyal; Arquitectura forense: Violencia en el umbral de detectabilidad:, Lugo / A Coruña, Bartlebooth, 2022

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 54

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024 55

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ

20 24

PREVIOUS EXHIBITIONS EXPOSITIONS PRÉCÉDENTES

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

MEMORIARTEAN 2022

CATALOGUE / CATALOGUE (ENG/FR)

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ 58

MEMORIARTEAN 2022

CONFRONTING DISMANTLED MEMORIES: REMEMBRANCE AND CIVIL WAR

The topic of the Spanish Civil War and its consequences has proven an unusual one for many artists working after the end of Franco’s dictatorship. With a few notable exceptions, the silence imposed by the so-called ‘transition to democracy’ seems to have been internalised by the art world until relatively recently. The artists participating in the Confronting Dismantled Memories: Remembrance and Civil War exhibition now break this silence, turning their gaze back to what happened during the war and to the silence which engulfed a large part of the population on the losing side, who suffered the consequences of the ensuing dictatorial regime for 40 long years.

Through images, videos, performances and photographs, etc., the exhibition reflects their desire to examine the pain and injustice experienced, tackle unresolved issues and pay tribute to the victims, in the hope that art can alleviate some of the suffering felt and help society understand that memory is a thread that joins the present to the past.

FACE AU SOUVENIR DÉMANTELÉ : MÉMOIRE ET GUERRE CIVILE

La question de la Guerre Civile espagnole et ses conséquences ont été étranges pour un grand nombre d’artistes qui ont travaillé après la fin de la dictature de Franco. Le silence imposé par ce que l’on appela la « transition vers la démocratie » semble avoir été compris, à quelques exceptions près, dans le monde de l’art jusqu’à il y a quelques années à peine. Les artistes qui participent à l’exposition Face au souvenir démantelé : Mémoire et Guerre Civile brisent ce silence, tournent leurs regards sur ce qui s’est passé pendant la guerre et sur le silence dans lequel baigna une grande partie de la population victime de la guerre dans le camp des vaincus et de ceux qui subirent les conséquences du régime dictatorial pendant 40 ans.

Grâce aux images, vidéos, performances, photos, etc., l’exposition dévoile le souhait de réfléchir sur la douleur, l’injustice, les questions en suspens, les hommages aux victimes, etc. dans l’espoir que l’art puisse aider à atténuer la douleur et communiquer au public que le fil de la mémoire relie le présent au passé.

MEMOR RTEan EL ARTE DE LA MEMORIA 2024

59

MEMORIARTEAN 2023

CATALOGUE / CATALOGUE (ENG/FR)

BURNED AIR AIR BRÛLÉ

60

MEMORIARTEAN 2023

THE BOMBING OF THE BASQUE LITERATURE