The Lost Trail of Tiffany

St. Paul’s Episcopal’s Stained Glass and Mosaics Were Designed by the Master, So Why Is It Such a Secret?

By David O’Reilly

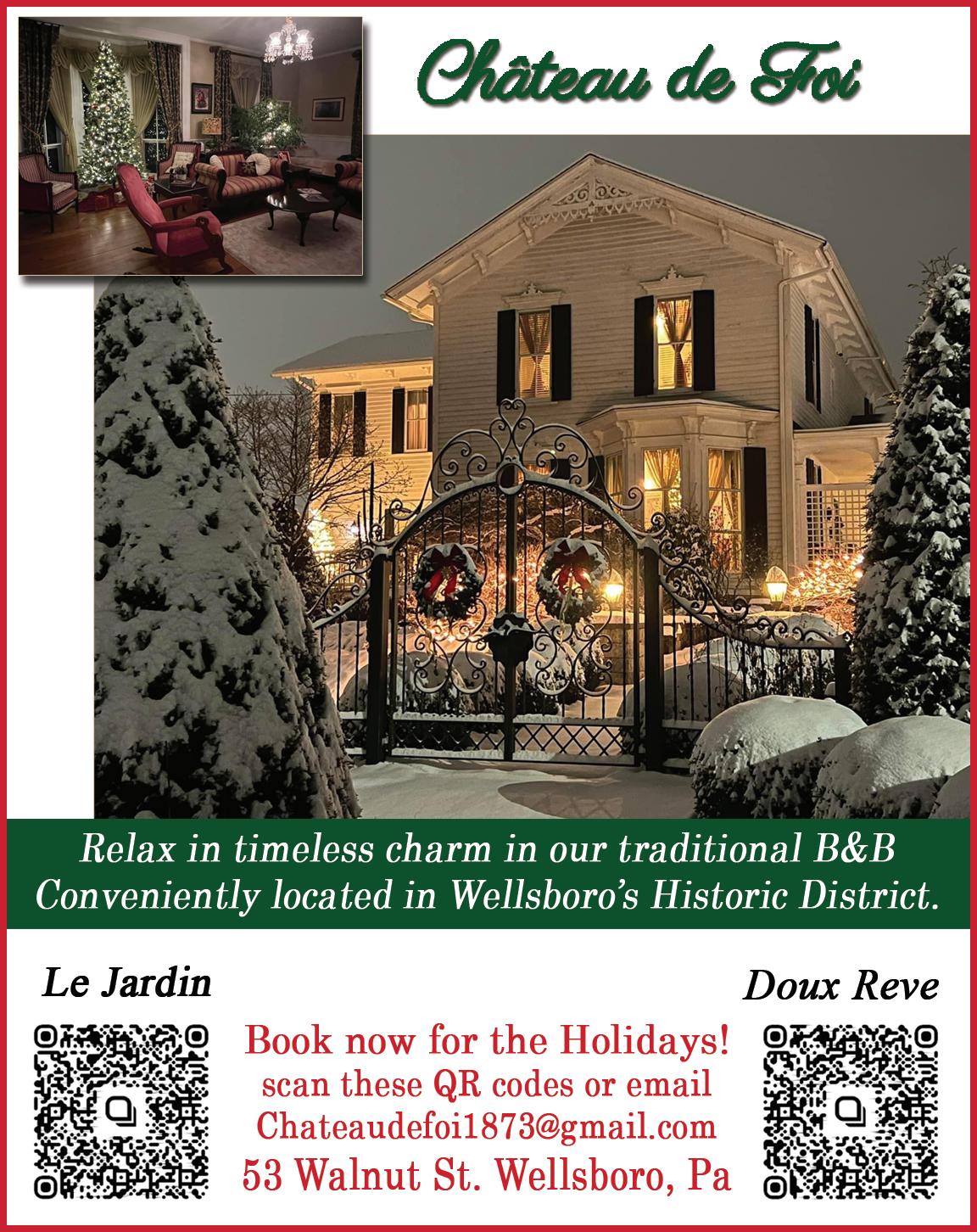

Perfecting the Art of the Gift Book ‘Em, Wellsboro (and All of PA)

St. Nick Doesn’t Jump Over the Candlestick

The Lost Trail of Tiffany

By David O’Reilly

St. Paul’s Episcopal’s stained glass and mosaics were designed by the master, so why is it such a secret?

Mother Earth

By Gayle Morrow

Singing Words

State

By Linda Roller

a pheasant in a pine tree.

Michael Capuzzo

Glory Hill Diaries By Maggie Barnes

By Curt Weinhold Sleigh bells and train whistles.

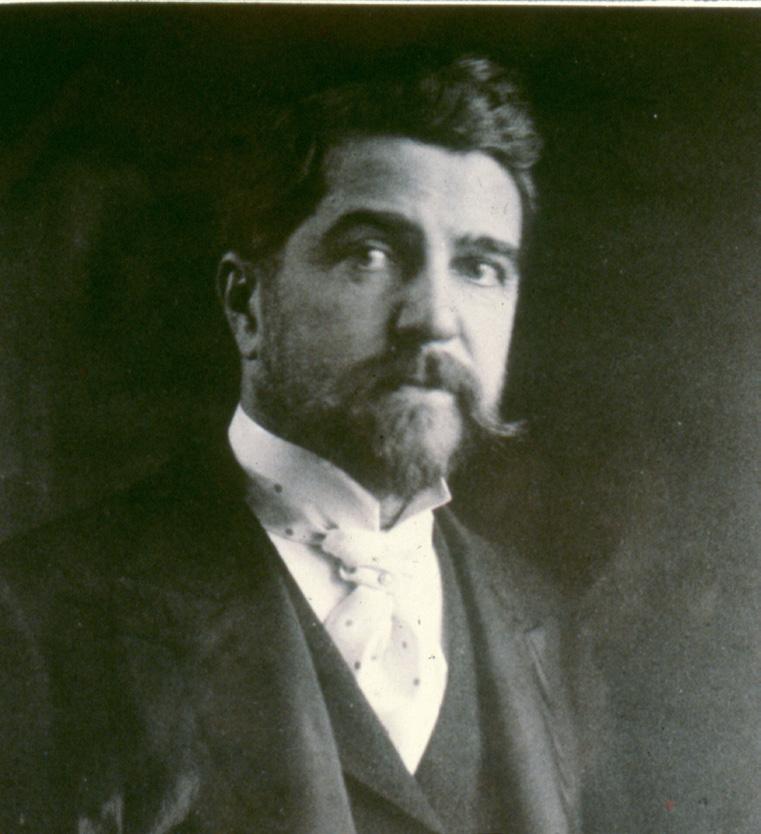

Cover photo by Wade Spencer. This page (top) Louis Comfort Tiffany c. 1888 Courtesy of The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, Florida; (middle) Pheasant © Linda / Adobe Stock; (bottom) Marjorie Maddox courtesy Marjorie Maddox .

mountainhomemag.com

E ditors & P ublish E rs

Teresa Banik Capuzzo

Michael Capuzzo

A ssoci A t E E ditor & P ublish E r

Lilace Mellin Guignard

A ssoci A t E P ublish E r

George Bochetto, Esq.

A rt d ir E ctor

Wade Spencer

M A n A ging E ditor

Gayle Morrow

s A l E s r EP r E s E nt A tiv E s

Shelly Moore, Shelley Shank

c ircul A tion d ir E ctor

Michael Banik

A ccounting

Amy Packard

c ov E r d E sign

Wade Spencer

c ontributing W rit E rs

Maggie Barnes, David O'Reilly, Linda Roller, Carolyn Straniere, Karey Solomon

c ontributing P hotogr AP h E rs

David O’Reilly, Karey Solomon, Carolyn Straniere, Curt Weinhold

d istribution t EAM

Dawn Litzelman, Grapevine Distribution, Linda Roller

t h E b EA gl E

Nano

Cosmo (1996-2014) • Yogi (2004-2018)

ABOUT US: Mountain Home is the award-winning regional magazine of PA and NY with more than 100,000 readers. The magazine has been published monthly, since 2005, by Beagle Media, LLC, 39 Water Street, Wellsboro, Pennsylvania, 16901, online at mountainhomemag.com or at issuu.com/mountainhome. Copyright © 2025 Beagle Media, LLC. All rights reserved. E-mail story ideas to editorial@ mountainhomemag.com, or call (570) 724-3838.

TO ADVERTISE: E-mail info@mountainhomemag.com, or call us at (570) 724-3838.

AWARDS: Mountain Home has won over 100 international and statewide journalism awards from the International Regional Magazine Association and the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association for excellence in writing, photography, and design.

DISTRIBUTION: Mountain Home is available “Free as the Wind” at hundreds of locations in Tioga, Potter, Bradford, Lycoming, Union, and Clinton counties in PA and Steuben, Chemung, Schuyler, Yates, Seneca, Tioga, and Ontario counties in NY.

SUBSCRIPTIONS: For a one-year subscription (12 issues), send $24.95, payable to Beagle Media LLC, 39 Water Street, Wellsboro, PA 16901 or visit mountainhomemag.com..

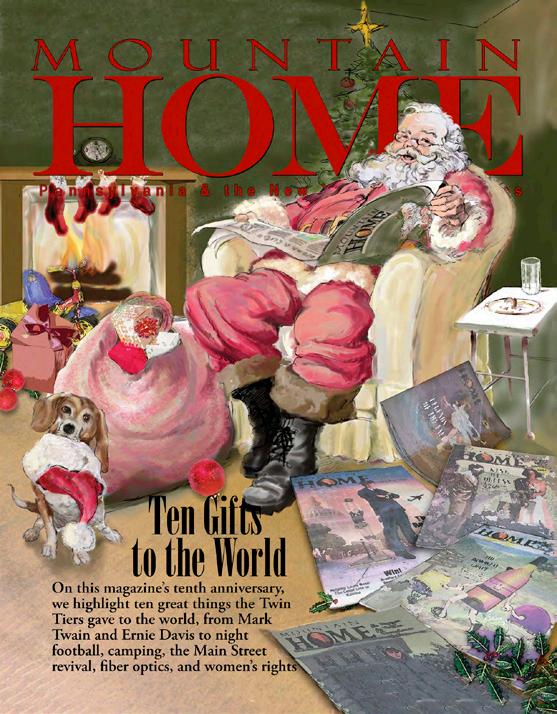

The Last Great Place

Happy Twentieth Birthday, Mountain Home!

By Michael Capuzzo

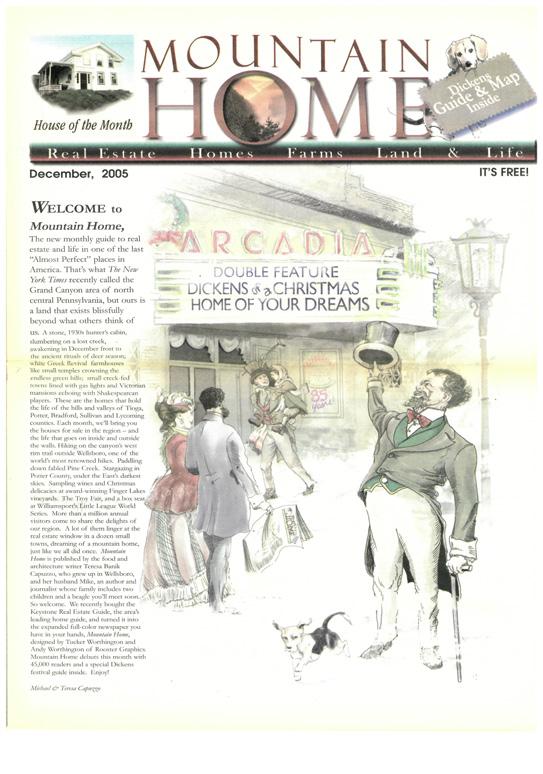

The Christmas holidays are a season of giving, so my wife gave me an assignment. It’s only fitting that Teresa Banik Capuzzo, the editor and publisher of Mountain Home, who made our company, Beagle Media, what it is, should take this space to write a column marking the twentieth anniversary of the magazine you have in your hands. But she was too busy putting this special holiday issue to bed, so the honor fell to me. It’s my pleasure.

In December 2005, while print was slowly dying all around us, including the Philadelphia Inquirer where we met, Teresa and I launched Mountain Home magazine in her hometown of Wellsboro to serve the Twin Tiers with its first full-color, monthly lifestyle magazine. Our big-city journalism friends thought we were crazy. But the late Tucker Worthington, the brilliant Wellsboro artist who sparked something in all three of us and designed every cover until November 2019, said it would be good crazy if we could capture arts and culture and winemaking and the parallel worlds of hunting and the outdoors, all through the history and people of our beautiful region.

A twentieth anniversary would be impossible without a shout out to associate editor and publisher Lilace Mellin Guignard, Teresa’s right hand at running the magazine; art director Wade Spencer; accounts manager/copy editor/office-runner Amy Packard; managing editor Gayle Morrow; circulation director Michael Banik; our brand new ad rep Shelley Shank; and our dozens of talented writers, artists, and photographers, including this month’s cover by our friend and former Inquirer colleague David O’Reilly.

None of us knew—before AI, politics, and corporate media that ruthlessly divide us by race and class and age and sex and geography—just how radical we were.

In the small house at 39 Water Street, our first office, we hung our “business model”—William Faulkner’s 1950 Nobel Prize speech that writers must once again write fearlessly about “the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing...the old verities and truths of the heart, the old universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed—love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice.” Faulkner goes on: “Until he does so, he labors under a curse…Until he relearns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man.”

The result: 100,000 readers in two states, more than 200 journalism awards, kudos from giants like Inquirer editor and New York Times managing editor Eugene Roberts, who had me teach what he called our “brilliant journalism” to his class at the University of Maryland.

Thank you dear readers, advertisers, Teresa, and God (not necessarily in that order) for twenty great years. Seriously, as a big-city journalist who fell in love with the country and a country girl, it’s been the great and humbling journey of my life to join with my wife to publish Mountain Home. What a ride it has been to tell your stories and share the meaning of our lives on this land together for 240 consecutive monthly regional magazines.

We are humbled by what you, our readers, have taught us as we tell your stories.

A Christmas Tale By DAVID CASELLA

“Dickens of a Christmas” Guide & Map

The Road and the Good Samaritan

asthewind

The Lost Trail of Tiffany

St. Paul’s Episcopal’s Stained Glass and Mosaics Were Designed by the Master, So Why Is It Such a Secret?

By David O’Reilly

Achildren’s choir is rehearsing a Christmas pageant before empty pews as Ramon Segers strolls up the central aisle of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Wellsboro. Ramon, then the parish’s acolyte, or altar server, pauses twothirds of the way up the red carpet. This is the spot, he explains, where acolytes stand for part of each Sunday communion service, holding open the book of the gospels for the priest to read aloud.

“Now, see that window there?” he asks, and points out a slender vertical window of golden glass high above the white marble altar. “Some mornings the sun comes through that and also from these,” and here he gestures to the large, multipaned windows high on the left and right walls, “and the light shines right onto the gospel.”

Might this be a perception enhanced by spiritual devotion? Perhaps. But those luminous windows—like all of St. Paul’s interior décor—are indeed worthy of marvel.

Fearfully and Wonderfully Made

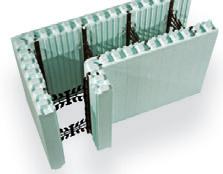

Completed in 1899 and seating three hundred and fifty, St. Paul’s bears the wry nickname “Cathedral of the North” around the Diocese of Harrisburg, a poke at its improbable grandeur here in rural, upstate Pennsylvania. And yet this stately, Romanesque stone “cathedral” fronting the town green is special for another reason.

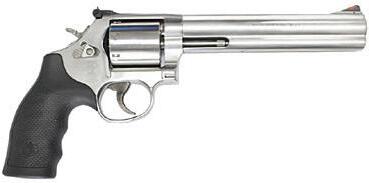

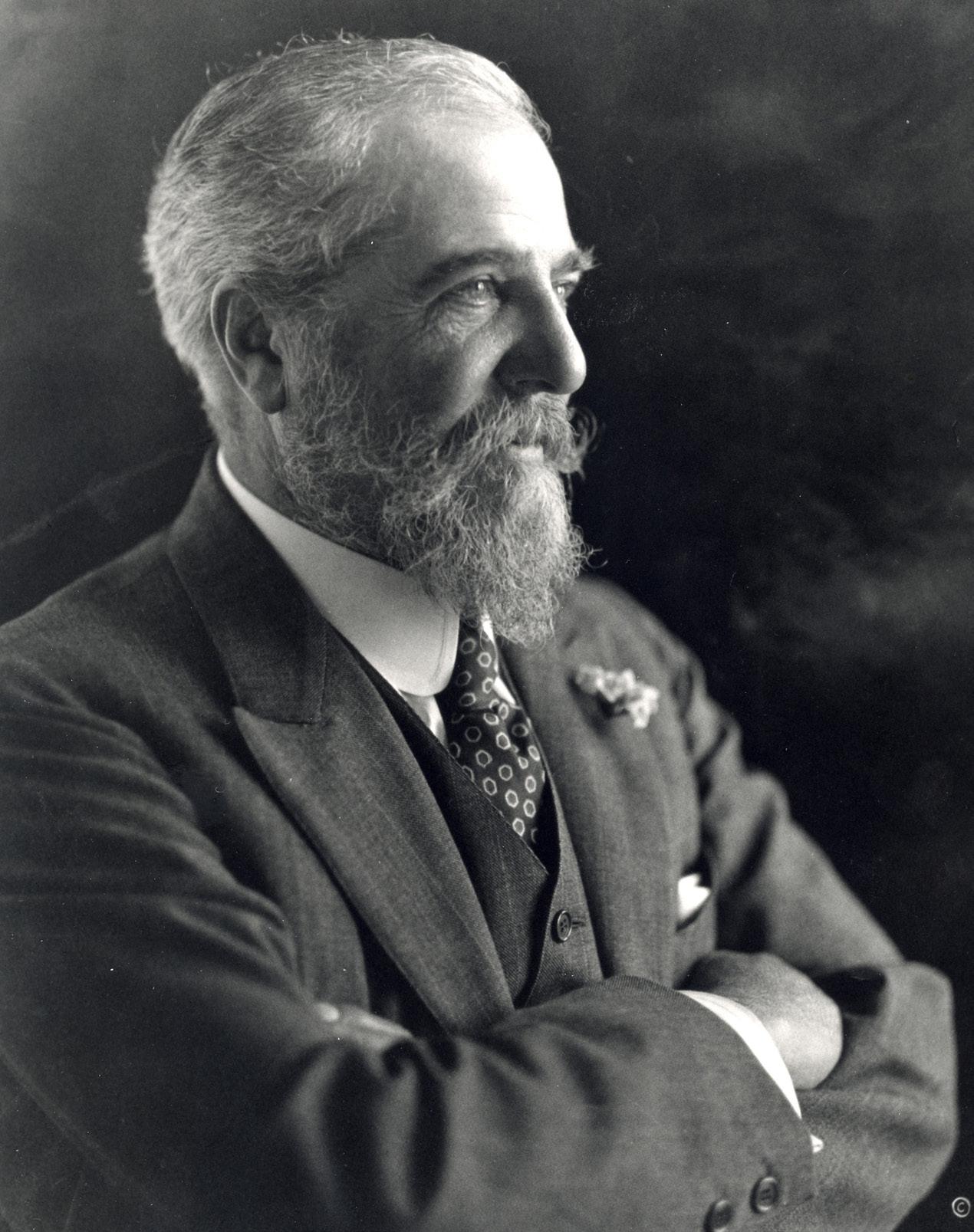

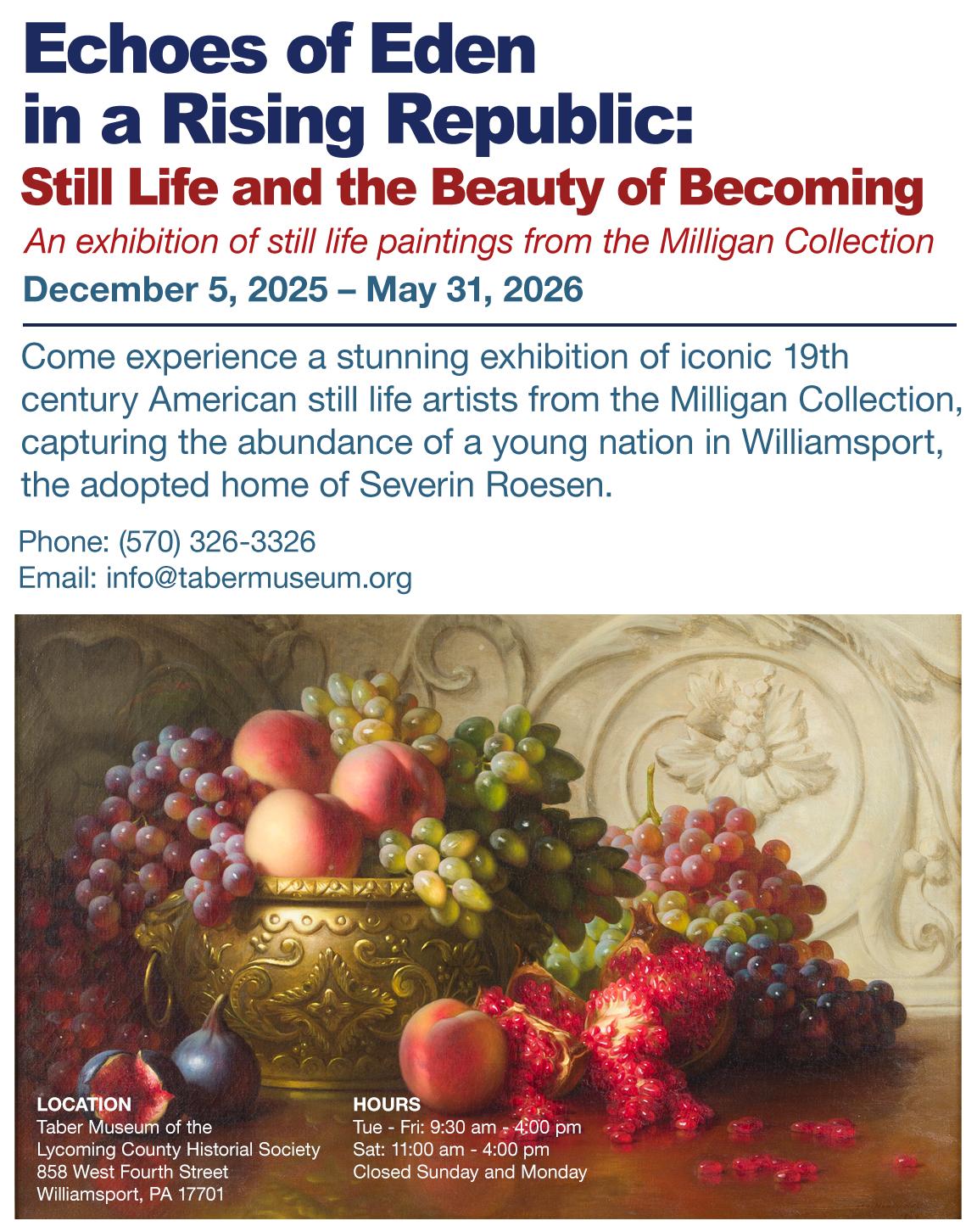

Its high marble altar and gilded altar screen, its chancel’s mosaic floor, the marble pulpit, the marble baptismal font, that vibrant, multihued rose window at the rear of the nave, and its ten majestic stained glass windows were crafted by the workshops of the legendary Louis Comfort Tiffany. While you may know him for his brilliantly colored stained glass windows and lamps, Louis was also a master of jewelry, pottery, furniture, textile, and photography who radically transformed the world of decorative art and design in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Wade Spencer

Father Millard Cook stands in the pulpit of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Wellsboro, which was designed by the studios of Louis Comfort Tiffany along with the altar, baptismal font, and mosaics throughout the sanctuary, making this one of the rare fully integrated Tiffany churches.

Tiffany continued from page 9

Name that Contains Multitudes

Louis Comfort Tiffany used his name to refer to work done by hundreds of artisans employed in his New York studios. Windows they designed, such as this one in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Wellsboro, are also called simply Tiffany.

And yet its unique status is virtually unknown outside its walls. An online search yields no published articles about the Louis Tiffany presence at St. Paul’s, which is referenced only once in a list of public sites decorated by Tiffany Studios. This story appears to be the first to shine a light on the parish’s many Tiffany treasures. Louis (pronounced Louie) might not have been born with a silver spoon in his mouth, but he was surely fed with one; his father was Charles L. Tiffany, founder of the iconic New York jewelry store. Surrounded by beauty and elegance as soon as he opened his eyes, Louis grew up to become a restless, visionary artist who “believed that beauty itself had called on him to create beauty using every material on the face of the earth,” says Jennifer Thalheimer, director of the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum in Winter Park, Florida, the world’s largest collection of Tiffany art. “And that’s what he set out to do.”

His shared reinvention of stained glass has a tangled history that we’ll visit below. Suffice it to say that starting around 1878 and continuing for six decades, Louis and his New York City workshops created legendary stained glass and other decorative objects for some fifteen hundred American churches and other public spaces. Nearly a third of those—435—were in New York State, with 186 in Pennsylvania. And yet only a handful of churches have ever possessed an array of Tiffany art as complete as St. Paul’s.

It was love at first sight for the Rev. Canon Gregory Hinton, who served as priest of St. Paul’s for twenty-four years. “I was there for an interview with the vestry,” he recalls recently, “and said I would love to see inside. So a vestry member escorted me in, and I was just dumbfounded by the beauty and majesty of it. It was something I always appreciated.” Father Hinton retired in 2018.

A Room with a View

What makes the sanctuary even more distinctive is that the windows at St. Paul’s don’t feature any of the gospel scenes typically associated with Tiffany Studios. No haloed saints, no winged angels, no transfigured saviors or trembling shepherds gaze down from the walls. Here you will find no mossy green forests, no coral sunsets melting into amethyst, no climbing wisteria or rippling mountain streams. And, with the exception of the rose window, they contain none of the saturated hues most people associate with Tiffany lamps and windows.

Instead, the seven large windows on the east wall and the three on the west are composed of hundreds of four-inch squares of parchment-colored glass, with every pane subtly different. Dappled here with pale gold, there with sky blue or amber, the overall effect suggests faint mother-of-pearl. Each window is also bordered by a repeating geometric pattern of ochre and sepia, and the two largest contain an encircled cross.

At first glance “they can seem very plain,” acknowledges Father Hinton. “But when the sun is shining, it’s like the fire of grace is shining through them. I would walk into the church in late fall and it almost looked like a conflagration on the other side. It would be really, dramatically moving.”

Courtesy of The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, Florida.

He was astounded back in 2000 when a glazier preparing to repair one of the smaller windows insisted it first be insured. “The appraisal came back $186,000,” he recalls, “so I can only imagine what it’s worth now.” (About $350,000.) And yet to esteem a liturgical object for its monetary value misses its point, he insists. The transcendent otherness of its artistry should “lift us from our everyday life and work and remind us we’ve entered someplace unique…It serves as a special intimation of almighty God in our lives.”

The Rev. David Perkins and then the Rev. Edward Erb followed Father Hinton as rector, and when Rev. Erb retired in January the parish sent word around the Episcopal Church USA that it was seeking a full-time rector “with a solid background in scripture and traditional liturgies.”

“We value traditional Sunday worship together above all other group activities,” they announced on their website. The announcement went on to say that St. Paul’s is “one of the rare fully integrated Tiffany churches,” and cited its “beautiful Vermont marble altar inlaid with Tiffany iridescent lustre glass mosaic” before moving on to the more substantive topic of church community. And so it was that on Sunday, October 19, senior warden George Osgood, the lay leader, stepped before about thirty-five mostly gray-haired congregants to announce that the vestry had chosen Rev. Millard Cook as the parish’s new priest-in-charge. “He’s sixty-two, single, and a Franciscan friar,” he said. “He’ll be here in two weeks.”

Reached a few days later in Harrisburg, where he’d been serving as a supply pastor for area parishes without full-time clergy, Father Millard—formerly a Roman Catholic priest—says he was impressed with the beauty of the interior. But what impresses him most is the number of parishioners—many of them new to the Episcopal Church and the parish—“who said they experienced a home at St. Paul’s. I consider that a healthy sign. It shows me that St. Paul’s not only professes to be welcoming and inclusive, but that they are.”

Where It Began

One might begin the story of St. Paul’s interior decoration from either of two points of origin. A conventional treatment would tell how the congregation emerged in 1838 from the remnant of a Quaker community founded in 1806. After decades worshipping in a former schoolhouse at Charles and Walnut Streets, it opened the doors to its current church, at Pearl and Charles Streets, in 1899, with all its windows by Tiffany Studios. The firm installed the new altar and likely the pulpit in 1914, while the baptismal font’s dedication date of 1916 suggests it arrived that year. Alas, a diligent search of the vestry’s records and contemporary newspapers revealed nothing of the parish’s plans to contract with Tiffany or what its aesthetic vision might be.

So let us instead fly back in time to Newport, Rhode Island. It’s around 1865, and we will peek into the simple clapboard house at 24 Kay Street where a gifted young muralist, John LaFarge, lies ill, perhaps poisoned by the lead and other toxic metals in his paints. And as we watch, a beam of sunlight illuminates a bottle in his room—legend says it was tooth powder—and LaFarge sits up, fascinated with how the colored glass scatters the light.

About age thirty, he resolves to learn glassmaking and is soon

Peace Work

A glimpse into the ecclesiastical department of the mosaic workshop where many of Tiffany’s elements for churches were created.

Tiffany continued from page 11

experimenting with “opalescent” glass, a traditional technique that embeds metallic oxides—cobalt for blue, nickel for violet, etc.—in molten glass to produce rich colors, but which had rarely been used in windows. LaFarge is soon creating astonishing new hues, but his great leap comes when he begins “plating” or layering sheets of opalescent glass of different hues and thickness and fusing them together. The combined effect is startling: a three-dimensionality that lends depth and realism to the images. This he further enhances by sometimes corrugating the exterior surface to simulate ripples in images of water and sunsets and meadows.

Until then, stained glass had been made by painting and firing colors onto clear blown glass. By layering and fusing opalescent glass, LaFarge had overturned a thousand years of stained glass tradition. And it was sometime in the 1870s that he made a fateful decision. He showed his novel techniques to a “sometime artist and decorator” thirteen years his junior: Louis Tiffany. Their relationship grew, and by 1880,

when LaFarge patented his technique, Louis was generating brilliantly innovative pieces that rivaled his friend’s.

But that same year Louis applied for a similar patent, and their friendship quickly soured. While LaFarge’s patent focused more on the materials of the glass and Tiffany’s on the layering of the plates, by 1882 LaFarge was preparing to sue Tiffany for patent infringement. What happened next is not clear, but the lawsuit never went to court. Some scholars surmise each of these geniuses realized he needed the other’s patent to make these new “American” style windows, and let the matter drop. Nevertheless, they remained bitter rivals.

LaFarge enjoyed a much-in-demand reputation as a muralist and stained glass maker, with clients that included industrialist Cornelius Vanderbilt, Harvard University, and Boston’s majestic Trinity Church. “He was an incredible artist. In some cases I prefer his work,” says Jennifer. “But he was a terrible businessman.” A moody perfectionist who personally oversaw every project (unlike Tiffany), he often overran budgets and deadlines and got into feuds with his

business partners. In 1885, his Manhattan-based LaFarge Decorative Arts Company collapsed, although he continued to take on commissions—including the two large stained glass windows at the First Presbyterian Church of Wellsboro, installed in 1895. Featuring intricate floral and geometric designs, they, like St. Paul’s, display no gospel scenes but are glorious in sunlight. Sadly, LaFarge died in 1910, deep in debt. Louis, on the other hand, was as gifted an entrepreneur as he was a designer. For the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair (technically the Columbia Exposition), his Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company simulated a breathtakingly beautiful full-scale chapel. Byzantine-inspired, it featured sixteen massive columns, six ornately carved arches, a marble altar, a pulpit, and a massive, eggshaped baptismal font, all covered in glass mosaic. If that were not enough, the thousand-square-foot “chapel” was illuminated by three brilliant stained glass windows and an eight-by-ten-foot electrified chandelier—powered by the thrillingly new alternating current—in the shape of a 3D cross.

Courtesy of The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, Florida.

Canyon Country Fabrics

HOURS: Tues, Wed. & Fri. 9-4; Thurs. 9-7; Sat. 9-3; CLOSED Sun. & Mon. 664 KELSEY ST., WELLSBORO, PA 16901 • 570-724-4163

For All Your Quilting Needs!

(570) 376-2351

Come see us this holiday season for Christmas trees and wreaths, rock salt and pet safe salt, Dry Creek wood pellets, and holiday gift ideas for your loved ones with 2 and 4 legs!

David O'Reilly

10977 Route 287, Wellsboro, PA Open Mon-Fri 7am-5:30pm, Sat 7am-2pm

The effect was so awe-inspiring that some visitors doffed their hats. Louis and his representatives went one step further: they presented him to visitors as the genius behind this stunning new style of stained glass, with no acknowledgment of LaFarge. Louis Comfort Tiffany was now the rock star of liturgical design, and at the height of his powers his New York studios would employ more than three hundred artisans.

He died at eighty-four in 1933, “but his business, which started about 1878, lasted until 1938,” Jennifer explains over the phone. “That’s a really long time to be in a business that depends on style.” She mentions that Louis’s celebrated 1893 chapel is on display at the Morse Museum. And by the way: she’ll soon be visiting the Corning Museum of Glass. She’d like to visit St. Paul’s.

Pretty, but Not Too Pretty

On a sunny October morning, Jennifer and her husband, Joe, arrive. Ramon (he’s now studying for the priesthood) welcomes them and escorts them to the vacant pastor’s office to show them the original framed design sketch of the altar signed by Louis himself. They then proceed into the nave, or central part of the church containing the pews. After glancing around—“My mind is everywhere,” she marvels—Jennifer turns her attention to the windows. Those uniformly square panes are what’s known as “quarry glass,” she explains, from the French carrè for “square.” “They were not inexpensive, but often temporary,” and typically installed as a placeholder until members of the congregation commissioned

Dip into History

Jennifer Thalheimer (left), director of the Florida museum with the world’s largest collection of Tiffany art, submerses herself in the details of the baptismal font with a wooden lid possibly made by Joseph Briggs. She explains that the turtleback medallion (right) on the front of the pulpit was made iridescent by fuming a mist of iron minerals over glass marbles.

more ornate memorial windows dedicated to themselves or a family member.

Still, some conservative congregations simply didn’t want the “distraction” of brilliantly colored or figurative windows and stayed with quarry style. And a snobbish congregation might disdain figurative windows on grounds that they had no need for gospel scenes to teach the unlettered. Quarry windows “could be a statement that says ‘We’re all educated.’”

Over at the pulpit she leans in to study the small glass squares, or tesserae, that face its six sides. What may appear blandly beige from afar reveals itself to be a mosaic of subtly varied, pearl-colored glass, fronted by a mosaic Maltese cross of pale pinks, lavenders, celery, and smokey blues, which she crouches to inspect. “What’s really interesting is the mortar,” she says. “It may be gilt. And they put a finish on so that it gives this beautiful, uniform tone.”

She then points out the palm-sized medallion at the center of the pulpit’s front-facing cross. Raised and round, the medallion is surrounded by what appear to be eight embedded marbles.

“This is called a turtleback,” she tells Ramon. “Tiffany liked to add visual interest, things that caught the light.” Ramon asks if the marbles are glass. Yes, she says, but “they were finished with an iridescent surface.” Tiffany artisans would “fume” a mist of iron minerals over the glass to replicate the iridescence of long-buried glass pieces found in ancient cities like Rome.

Next she lays a finger on the blue lapis and gold glass trim bordering the pulpit walls. The design is called Cosmati, she ex-

Wild Asaph Outfitters

Tiffany continued from page 15

plains. “It became associated with Tiffany,” but it’s named for an Italian family that developed such winding patterns in the thirteenth century. She steps back. “Look at how many patterns there are,” she marvels. “Yet they all blend beautifully.”

Moving forward, Ramon points out the mosaic tile floor of the chancel, in which the choir sits at service, and then they study the wooden, gothic-style communion rail. It might be Tiffany, she says, but his studio sometimes commissioned woodwork to subcontractors. They then approach the high altar, nine steps above the nave floor, which, like the pulpit, is surfaced with hundreds of multhued glass tiles, the tesserae.

“You can see the iridescence, how it captures the light and seems to be moving as you move,” she says, and yet marvels at its simplicity. “Just tile. No glass gems or anything else.” She then pulls out a magnifying glass to inspect the veined, beige marble of the altar and tall altarpiece, or reredos,

Sacred Patterns

Blue lapis and gilt glass create the intricate Cosmati that trim the pulpit (top left). The large Maltese cross on the front of the marble altar is made of amber, cream, and golden tesserae that echoes the smaller jade cross on the baptismal font and the quarry glass squares that make up the large sanctuary windows.

behind it. “Absolutely beautiful,” she says, before stepping back to admire the vast, arching altar screen filling the rear wall. Yet another Louis creation, its silvery foil surface is stencilled with interlocking swirls of green ivy and red berries.

As they stroll to the rear of the nave, Jennifer points up at the half-dozen circular wrought iron chandeliers. “The upper part, the chains and knobs, looks like Tiffany,” she says, “but the bottom does not.” She wonders if they might originally have held gas lamps, and Ramon mentions that in the 1940s the Rambusch Lighting Company of Jersey City, New Jersey, replaced them. Rambusch also repaired water damage to the altar screen in the 1980s, and this year replaced a marble pilaster, or rectangular column, on the altar piece at a cost of $74,000.

She is skeptical, however, of the origins of the large, wrought iron central chandelier. “That is not typical of what they [Tiffany Studios] would have produced,” she says,

“but you can never say never.”

The circular rose window high above the entry doors next catches her eye. Five green acanthus leaves on a blue field surround an inner circle containing a white disk that might represent a communion wafer. “This is interesting,” she says. “Rose windows are often figurative. They contain biblical stories or symbols or saints. So this tells me they [St. Paul’s] didn’t want in-yourface imagery…Even though they went for Tiffany, it seems they did not want a lot of symbols. They didn’t want anything gaudy.”

“Well, this town was founded by Quakers,” Ramon replies. “That might explain why everything is so simple. Or they may have wanted a more ‘Protestant’ aesthetic instead of the ‘high church’ look.”

“That makes perfect sense,” she replies.

At last they make their way to the baptismal font, positioned at the entry to the church to signify one’s entry into Christian faith. It, too, is of beige marble faced with

Lilace Mellin Guignard

(2) Wade Spencer

Full service quilt shop. Fabric, batting, thread, patterns, books, and classes. Longarm quilting service Classes Available—Call Today! (570) 529-7070

2351 Burlington Turnpike, Towanda 2 miles off Rt. 6 in Burlington heading toward Towanda. Hours: Tues-Fri. 10am-5pm; Sat. 10am-4pm

suesquiltcreations.com

Incontinence Supplies

Power Mobility

Compression Hosiery • Braces - Knee, Ankle, Arm • Mobility Equipment • Ostomy Supplies • Bathroom and Home Safety Equipment • Wound Care Supplies

Mother Earth

AHow many people do you think are down there? Too many.

And a Pheasant in a Pine Tree

By Gayle Morrow

partridge in a pear tree? Seven swans a-swimming? Around here? Probably not in December. A crow in a cornfield or a finch on a fence is more likely. But you won’t know until you and your binoculars get out there and start looking, will you? The National Audubon Society’s annual Christmas Bird Count is the perfect opportunity to spread your citizen-scientist wings and maybe astound the birding world with what you see.

I always thought the CBC was a oneday event—maybe Christmas afternoon you wander around outside for a while, notice the cardinals and juncos at the bird feeder, then head back inside to drink more eggnog. Nope. I probably had it confused with the Great Backyard Bird Count, which takes place on President’s Day weekend (and may or may not involve eggnog). This year the CBC, now in its 126th incarnation, runs from December 14 through January 5. It’s way more organized than I ever realized, which makes good sense if you want the collected data to be useful.

Back around the turn of the last century, some folks in North America partic-

ipated in a Christmas competition known as side hunts, a holdover from Victorian England and the continental aristocracy. There were sides—maybe geographic or familial—and participants shot as many birds and other living things as they could, with the goal of seeing which side could kill the most. Lovely, right? (Check out fieldethos. com/christmas-side-hunts/ for a quick overview.) Ornithologist Frank M. Chapman, an early-on member of the fledgling Audubon Society, had a better idea: Let’s see how many birds we can count instead of how many we can kill. The first CBC was on Christmas Day, 1900, and included twenty-seven counters counting birds in over twenty-five different places from Toronto to California.

Today there are thousands of people counting birds in thousands of locations in over twenty countries in the Western Hemisphere. My friend Kathy Riley, a member of the Tiadaghton Audubon Society here in Tioga County (tiadaghtonaudubon. blogspot.com) and a dedicated birder for fifty-plus years, explains that each count takes place in an established fifteen-mile-di-

ameter circle. Some areas have lots of circles and lots of participants, others not so many. (check out the CBC circle map at audubon.org). Depending on where you are (or where you might be willing to go), you’ll be assigned a circle. Kathy says it works best for at least two people to work together—one can drive and one can list the birds seen. Binos are helpful, as is a notebook and the field guide of your choice. The Sibley Field Guide and the Peterson Field Guide to Birds are popular. Your end-of-the-day results are given to the count compiler who is in charge of your circle, with those numbers eventually going to the National Audubon Society.

The best way to get started with the CBC is via the Audubon website or your local Audubon Society chapter. In addition to the TAS, check out lycomingaudubon.org, sevenmountainsaudubon.org, and cvaudubon.org. If the CBC whets your appetite for birding, you can get the free eBird app by Cornell Lab. It helps you identify what you’re seeing and contribute your information and sightings to a worldwide database.

’Em, Danno

Led by editor and poet Marjorie Maddox Hafer (center), regional poets included in the Keystone Poetry anthology pose with copies at the City of Asylum Bookstore in Pittsburgh. Book

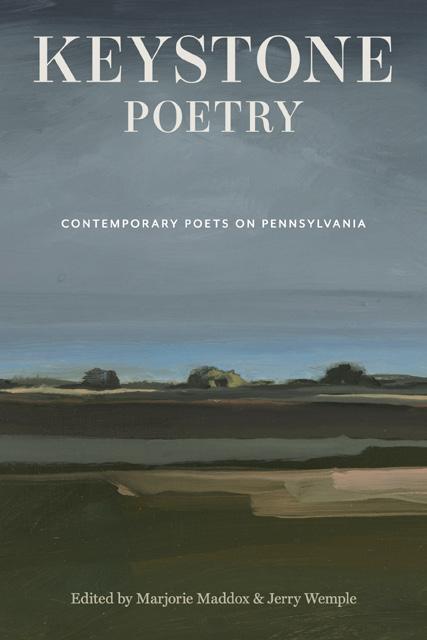

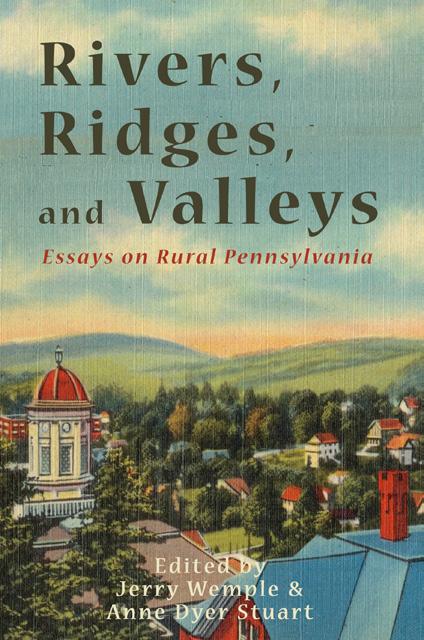

Singing Words ’Round the Keystone State A

Celebration of Regional Anthologies

By Linda Roller

“Bald Eagle Mountain is fringed with mist hovering over the trees like furry eyebrows…”

-Gloria Heffernan, “Sunrise on a Back Porch in Pennsylvania”

Aregional anthology, in the right hands, is a box of fine chocolates, and as welcome a holiday gift. The words will take you back to beloved memories or will show you another view of places you thought you knew. This year, two samplers of Pennsylvania’s creative writing have been released, generating new audiences and exposing long-time readers of regional work to new voices in unusual places. Keystone Poetry sings the song of Pennsylvania large and small, in all the dialects of a patchwork quilt state, while Rivers, Ridges, and Valleys focuses on that land often described—mistakenly— as an empty, one-note “T” stretching between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh and covering the entire northern half of the state. The voices are varied and are tended to lovingly by veteran writers and editors of poetry and

creative nonfiction in the Commonwealth. Jerry Wemple is an editor for both anthologies, along with Marjorie Maddox Hafer for Keystone Poetry and with Anna Dyer Stuart for Rivers, Ridges, and Valleys

Two anthologies in the same year seem a daunting task for Jerry, who is a full-time professor at Commonwealth University-Bloomsburg. While agreeing it was at times almost too much, and the process with each was different—the poetry tome is a twentieth anniversary edition—Jerry thinks the two books have many connections. “It’s an odd thing—lots of poets also write creative nonfiction,” he says. “The use of language to create images in both ties the two genres together.”

“The poetry anthology started as an idea five years ago,” explains Marjorie, professor emeritus at Commonwealth University-Lock Haven, and co-editor of Keystone Poetry. “The idea for this twentieth anniversary edition came from a discussion with one of the poets, Steve Myers, who teaches at DeSales University and who also was included in Common

Wealth, the 2005 anthology. Steve felt strongly that it was time for another anthology, something that Jerry and I had already been considering. But this was the nudge that I needed. I emailed Jerry, and we agreed to write and submit a proposal to PSU Press for a twentieth anniversary edition.”

This project, done over five years (the planned release date was always 2025), was to be substantially different from the original. Jerry notes that the number of poets increased. “We had between 700 to 800 submissions by over 300 poets, from which we selected 182,” including Mountain Home writers Lilace Mellin Guignard and Judith Sornberger. In Common Wealth, up to three poems were by a single author, but for Keystone Poetry, only one poem from an author was selected. Both Jerry and Marjorie stressed that this collection needed to include every area of Pennsylvania.

“Thus, we have poems about urban areas, but also about taxidermy, the names of bars, boilo, a roller coaster, hockey, Ricketts

See Singing on page 22

Courtesy

Marjorie Maddox Hafer

Trust That Spans a Century

For 100 years, Guthrie Orthopedics trusted partner in helping our community move better and live fuller lives.

Built on a foundation of excellence and driven by modern advancements, we’ve grown into an award-winning program with 19 clinics and a wide range of services—from joint replacements and sports medicine to rehabilitation and more.

Experience

every step of the way.

Liberty book Shop

Stop by and see what we bought this Fall! We have new books in every category—the shop is bursting with great books at great prices.

HOURS: Thurs & Fri 10-6; Sat 10-3 (or by appointment, feel free to just call)

Glen State Park—well, you get the idea,” says Marjorie. And, it needed to include world-shaping events that happened after 2005.

“You’ll find poems that address covid, the Tree of Life Synagogue massacre in Pittsburgh, the election, and gun violence, to name a few,” she adds.

Poetry is best as a performance, where the words are spoken and the breadth of the stanzas soar. Keystone Poetry is having an amazing statewide reading tour. Jerry notes that the initial readings were set up by PSU Press.

“They have a publicist that set up the first events much like the readings done for Common Wealth,” he says. But the two editors were delighted with the places and contributors that asked for regional readings. The tour has grown organically, and now there are dates for readings extending to May 2026. Events with fifty to seventy attendees have been held in every area of the state. “It’s exciting to hear accomplished poets writing about the places you live or have visited,” Marjorie says. Upcoming events are scheduled for Ursinus College, Grove City College, Gettysburg, “and a slew of virtual readings.”

In comparison, the development of Rivers, Ridges, and Valleys was lightning-quick. It was an editor at PSU Press who saw Jerry on a panel about regional writing and discussed a collection of essays.

“That got the ball rolling,” Jerry says. Some prose writers writing about rural Pennsylvania were contacted, and a general call was made through university listserves and social media. By the time the collection was selected and edited, the actual publication was not through PSU Press, but through Catamount Press, a division of Sunbury Press devoted to writing in northern Appalachia, so a good fit.

For this collection, Anne Dyer “AD” Stuart joined Jerry as an editor. AD hails from the southern states, and in talking about the “voice” of rural Pennsylvania, muses that even her native Mississippi no longer has one voice.

“So many of us are transplants from all over the place, and we bring our stomping grounds with us,” AD says. “Maybe every place is not losing a distinctive voice so much as gaining a choir. I think we sing to a place as much as it sings back to us. Maybe it’s not so much voice as it is subject matter, where those from a more rural area may have a different relationship with the land and notice their surroundings differently.” She notes that her family, including a husband from North Dakota, have established roots in rural Pennsylvania simply by working the land and raising animals on their farmette in Columbia County. That feeling of place echoes in the essays, including the two from Mountain Home writers Jimmy and Lilace Guignard.

In fact, the collection was nominated for Book of the Year by the Writers Conference of Northern Appalachia. Deborah Copley Reynolds, board member, notes that the book has already been through the first decision round and is on the long list for 2026 Book of the Year.

Find both Rivers, Ridges, and Valleys and Keystone Poetry in time for the holidays at your local bookstore.

Mountain Home contributor Linda Roller is a bookseller and writer in Avis, Pennsylvania. Singing

Local Artisans

(2) Courtesy James Beez States

Karey Solomon

Local Artisans

Carolyn Straniere

Glory Hill Diaries

Flaming Santa

By Maggie Barnes

“I’d say this looks properly festive.”

I straightened my aching back and surveyed our house, decked to the halls for Christmas. Lights and garland graced every window and the archway between the living and dining rooms. The collection of cloth Santas adorned every table. (Leaving room for the coasters. We aren’t heathens, you know.) A stout and sturdy evergreen glistened in the corner, and the Vienna Boys Choir harmonies were wafting through the air. On the front doorknob hung a ridiculously large set of jingle bells, guaranteed to rattle the windows with every jangle when the door opened.

“I bought the cutest candle,” I said to Bob while rustling through the shopping bag. I held it up to him. It was two pieces,

one a small resin fire truck and the other a figurine of Santa wearing a firefighter’s turnout gear and helmet. Santa had his arms in a circle, as if holding on to something.

“Santa’s truck is not properly equipped,” Bob said critically. “And it has a hole in the hose bed.”

I punched him in the arm.

“Stop being a chief for a moment! It’s adorable. See—Santa goes on the candle. As it burns, he slides down to the truck. Like the pole at the fire house. Cute, huh?”

Bob rolled his eyes and started stacking the empty totes together for the return trip to the garage. My husband was chief of our city’s fire department, a habit of public service he picked up from his parents, both devoted to the volunteer department in their

town. I looked forward to showing off my candle on Christmas Day.

And the day showed up quick, like it always does. I swear there were more days in December when I was a kid. It felt like 142 days of waiting before the magic dawn would appear. As an adult, some of that magic has morphed into an endless to-do list with more tasks than time, but it is still my favorite time of year.

My in-laws showed up two hours early, as was their norm. There was a fair amount of scrambling still going on, but the two of them simply got their coffee and settled into the living room to await the chaos of kids and presents. I showed Dad my clever candle, to which he replied, “That hose bed is no good with that hole in it.” Yes, sir, the

welcome to FINGER LAKES

apple did not even fall off the Barnes tree! Determined to not let their nay-saying diminish my joy, I lit the candle and set it on the hutch in the dining room.

We had a joyous morning, and shortly the living room looked like an earthquake’s aftermath, with wrapping paper, bags, ribbons, and essential instruction and warranty cards about to be accidentally pitched. Everyone was settling in for the day. The kids got a baseball gizmo they could throw a ball at and a voice would announce strike or ball. They hung it on the garage door. Complete with a brief version of the national anthem, the echo down our narrow driveway was loud enough to have the Murphy’s terrier standing at attention next door.

Bob was fussing in the kitchen as the kids piled in the door for drinks between innings, and my father-in-law was hunting up another cup of coffee. That’s when Dad turned around beneath that archway of garland and lights and matter-of-factly announced: “Fire.”

The top of the hutch had a singular, wide flame shooting skyward. Something red was dripping off the edge and onto the glass door below. I yelped. My step-daughter Angie shouted for her dad—I saw Bob glance around the corner and then raise one eyebrow.

This is life with Barnes men. Their level of composure borders on comatose. They simply refuse to respond to any crisis with an unleashing of wild emotion. They take action, calmly and without panic. I find this aspect of their character really irritating. I need a good, solid panic before I can address a situation. Yelling, flailing of arms, cursing—extra points if it is creative—and running around pointlessly is all part of my process.

Bob wordlessly smothered the flames with the kitchen extinguisher and assessed the damage to the hutch. There was a brief investigation into cause and origin, but I already knew the arsonist at work. Me. My adorable Santa candle had one design flaw. As the candle burned, Santa didn’t slide. He stubbornly clung to his position at the midpoint and the flame had no choice but to melt St. Nick into a grotesquely disfigured blob.

The next sound I heard was laughter, and I turned to find Dad, still in the same spot under the archway, sipping his coffee and chortling like an amused child.

“Dad!” I exclaimed, my heart still pounding in my chest, “Next time there’s a fire, could you raise your voice or something?”

He brushed my cheek with his knuckle, a gesture he often used to reassure me, and headed back to the couch and my comparably giggling mother-in-law. My husband tossed a kitchen towel over his shoulder and headed back to the roast beef. I stood alone with the smell of melted plastic in the air and the feeling that I had accidentally firebombed my own family on Christmas.

Mom and Dad are gone, but we still remember that day and Dad’s complete lack of reaction. It’s the way he lived his life—simply and without fuss. He was almost always happy. Never said a bad word about anybody. We really miss that laugh.

But life and family gatherings continue. I got the cutest doodad for this year…three angels that hang above four candles, and…

Maggie Barnes has won several IRMA and Keystone Press awards. She lives in Waverly, New York.

welcome to WELLSBORO

HOLIDAY

by Lilace Guignard

Sponsored by Dan Usavage in Memory of Karen

A 1940's radio show sets the stage for holiday songs, local history, humor, and heart—along with a festive Charcuterie for Two (must pre-order) and beverages for purchase—making this a night of cheer not to be missed! This Hamilton-Gibson Women's Project production is back by popular demand.

Edu c

Enlighten your mind. Heal your spirit Nourish your body. Transform your soul

• Functional Health Coaching

• Healthy Lifestyle Classes

• Cancer Prevention/Recovery Coaching

• Aromatherapy & Herbal Classes/ Consults/Products: Featuring “The Scentual Soul” - Fine Aromatherapy EOs and Product Line

Sheryl Henkin-Kealey, BS.Ed, CMA, Certified Holistic Cancer Coach Board Certified Health Coach

(570) 634-3777 • sycamorespirit@proton.me Visit www.TheSycamoreSpirit.com for class schedules! Facebook.com/TheSycamoresSpiritWellnessEducationCenter New Location: 55 East Avenue, Wellsboro

tesserated glass, and also features an amber and jade-colored Maltese cross. “The coloring is just beautiful,” she marvels, but what she finds particularly delightful is its broad wooden lid, which she lifts to examine.

“It’s likely by Joseph Briggs,” she says. An accomplished wood-carver, “he began sweeping floors for Tiffany, then moved to glass cutting.” He later became head of mosaics, a close friend of Louis, and ran the company after Louis retired.

Celebrating God in Nature and Beauty

As they approach the exit she takes one final glance over the whole interior. “Fascinating,” she murmurs, before she and Joe stroll over to the Green Free Library, once the home of Chester Robinson, a wealthy lumber baron. There they inspect a classic Tiffany glass door installed in 1903. Custom-made, it depicts a smokey blue vine and a tree with a sunset sky and hills in the distance, once the view behind this stately mansion.

This being a weekday, the handsome red doors of the Presbyterian Church next door are locked, and so they head back to Corning. What they have missed are not just the LaFarge windows but a splendid new stained glass window in the vestibule. A gift of the late violinist Al Lofgren, a member of the congregation, and installed in 1995, it depicts a dark green woods populated by a buck, a pheasant, an owl, a grouse, and a cardinal, with a stream coursing down its center.

Above it angels blow on trumpets, and the border displays horns, a drum, a lyre, a tambourine, bells, and musical notes. Created and installed by Willet Stained Glass Studio of Winona, Minnesota, it cost fifty thousand dollars.

“Al wanted something that would accentuate the idea that in nature God is praised, and the hills and wildlife are God’s,” explains the Rev. Bob Greer, pastor from 1992 to 2007. Along with the glorious figurative windows gracing Wellsboro United Methodist Church, created by Haskins & Co. of Rochester, they testify most eloquently to the truth that Louis Comfort Tiffany was just one of countless artisans, nearly all anonymous, who have long brought extraordinary beauty to the worship of God.

Still, Father Millard, who went around the nave on his first Sunday greeting each parishioner with a handshake and a “Peace be with you,” says he’s already captivated by the lambent glow of St. Paul’s windows, “which so lend themselves to quiet contemplation.”

“Who else [but Tiffany] could capture the magnificence of each individual pane?” he wonders. “As the sun moves around the church, every single panel will receive the light of the sun and its moment of glory,” much as divine grace can touch individuals at different times and places. In those seemingly plain “quarry” windows, he surmises, the congregants of St. Paul’s “may have found just what they were looking for.”

Award-winning journalist David O’Reilly was a writer and editor for thirty-five years at The Philadelphia Inquirer, where he covered religion for two decades. Contact him at davidcoreilly@gmail.com.

Susan Shadle

North East tradE Co.

BACK OF THE MOUNTAIN

Sleigh Bells and Train Whistles

By Curt Weinhold

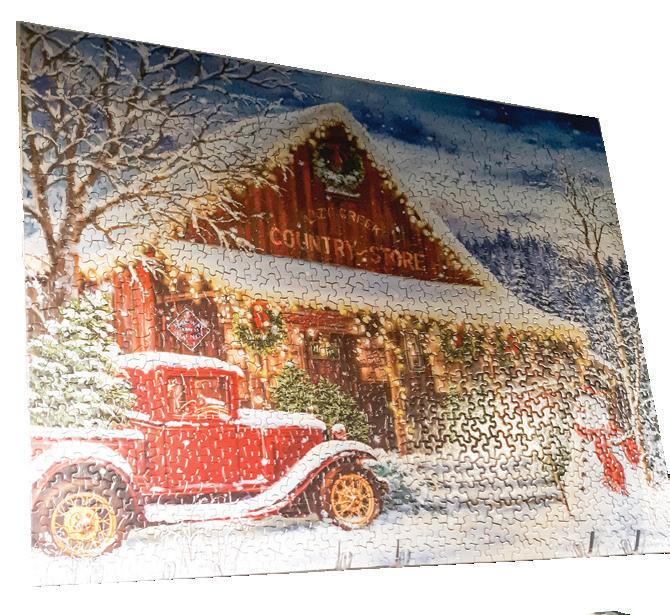

Heavy snow falls as Mike Berberich shuts the door of the Shay Locomotive shed at the Pennsylvania Lumber Museum near Galeton. After a day of skiing I visited the museum just prior to closing, knowing it would be photogenic in the new snow. Then along came Mike, aka “Iron Mike,” the former museum maintenance man. As he closed the door, I knew I’d captured a special moment for many, and especially for Mike.

The “Shay” was used as a logging locomotive in the day and is one of many exhibits. Santa himself will be inside the locomotive cab December 13 from noon to 3 for pictures with good little boys and girls.

We’re Here in Your Community.

UPMC Magee-Womens o ers general and specialized OB and gynecology care, solutions for pelvic floor and bladder issues, attention to pain you don't have to live with, and relief for menopause symptoms. We’re here to care for you.