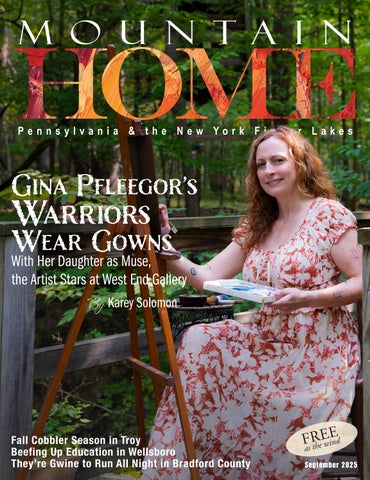

Gina Pfleegor’s Warriors Wear Gowns

With Her Daughter as Muse, the Artist Stars at West End Gallery

By Karey Solomon

Fall Cobbler Season in Troy

Beefing Up Education in Wellsboro

They’re Gwine to Run All Night in Bradford County

FREE as the wind

By Carol Cacchione

By Linda Roller

By Lilace Mellin Guignard

By Maggie Barnes

Stephen Foster’s “Doo-Dah” lives on in Bradford county.

Gina Pfleegor’s Warriors Wear Gowns

By Karey Solomon

With her daughter as muse, the artist stars at West End Gallery.

By Karin Knaus

Local smashburgers a smashing success at Wellsboro Area High School.

By David O’Reilly

Troy’s own cobblers give their customers happy feet.

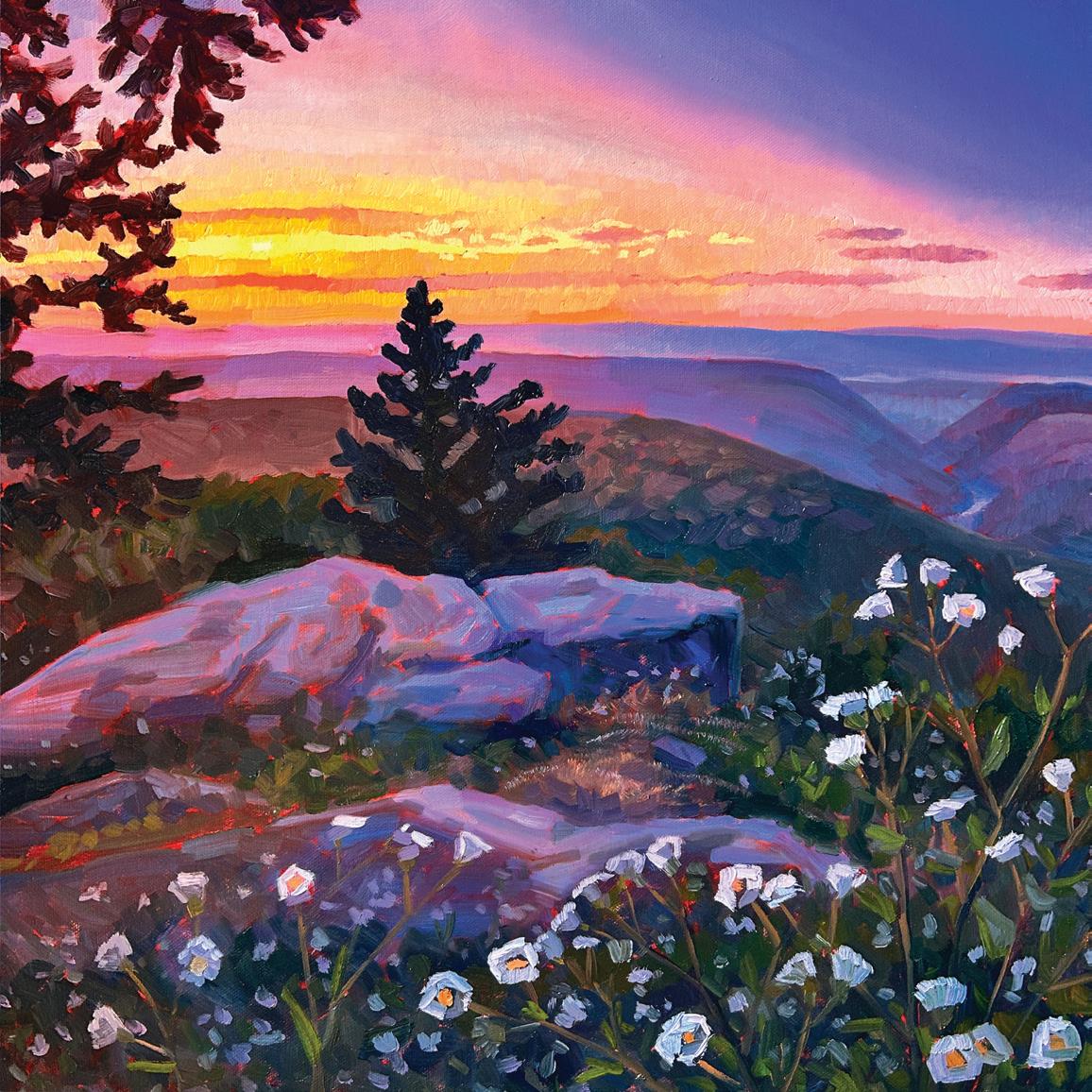

Cover photo by Wade Spencer. This page (top) Gina Pfleegor courtesy West End Gallery; (middle) Hillstone Farms by Cameron Clemens; (bottom) Jack Kuyper by Wade Spencer.

mountainhomemag.com

E ditors & P ublish E rs

Teresa Banik Capuzzo

Michael Capuzzo

A ssoci A t E E ditor & P ublish E r

Lilace Mellin Guignard

A ssoci A t E P ublish E r

George Bochetto, Esq.

A rt d ir E ctor

Wade Spencer

M A n A ging E ditor

Gayle Morrow

s A l E s r EP r E s E nt A tiv E

Shelly Moore

c ircul A tion d ir E ctor

Michael Banik

A ccounting

Amy Packard

c ov E r d E sign

Wade Spencer

c ontributing W rit E rs

Maggie Barnes, Karin Knaus, David O’Reilly, Linda Roller, Karey Solomon

c ontributing P hotogr AP h E rs

Maggie Barnes, Cameron Clemens, Linda Stager d istribution t EAM

Dawn Litzelman, Grapevine Distribution, Linda Roller

t h E b EA gl E

Nano

Cosmo (1996-2014) • Yogi (2004-2018)

ABOUT US: Mountain Home is the award-winning regional magazine of PA and NY with more than 100,000 readers. The magazine has been published monthly, since 2005, by Beagle Media, LLC, 39 Water Street, Wellsboro, Pennsylvania, 16901, online at mountainhomemag.com or at issuu.com/mountainhome. Copyright © 2025 Beagle Media, LLC. All rights reserved. E-mail story ideas to editorial@ mountainhomemag.com, or call (570) 724-3838.

TO ADVERTISE: E-mail info@mountainhomemag.com, or call us at (570) 724-3838.

AWARDS: Mountain Home has won over 100 international and statewide journalism awards from the International Regional Magazine Association and the Pennsylvania NewsMedia Association for excellence in writing, photography, and design. DISTRIBUTION: Mountain Home is available “Free as the Wind” at hundreds of locations in Tioga, Potter, Bradford, Lycoming, Union, and Clinton counties in PA and Steuben, Chemung, Schuyler, Yates, Seneca, Tioga, and Ontario counties in NY.

SUBSCRIPTIONS: For a one-year subscription (12 issues), send $24.95, payable to Beagle Media LLC, 39 Water Street, Wellsboro, PA 16901 or visit mountainhomemag.com..

Gina Pfleegor’s Warriors Wear Gowns With

Her Daughter as Muse, the Artist Stars at West End Gallery

By Karey Solomon

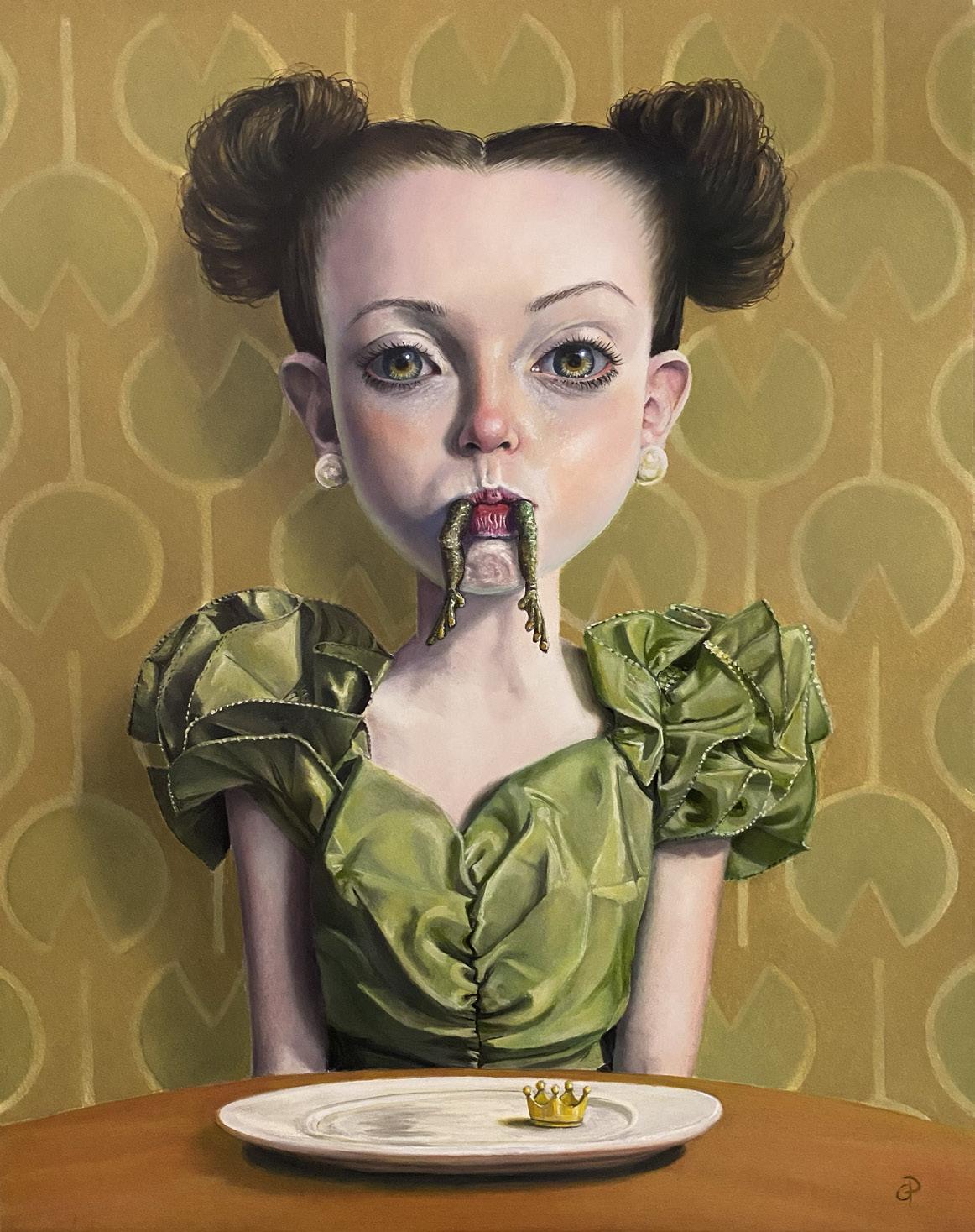

Consider Plot Twist, the first painting in Gina Pfleegor’s online gallery of work: a young girl in a fancy gown sits at a table.

Before her is a plain china plate holding a tiny crown. Frog legs hang from between the girl’s pursed lips. The girl looks resolute, even slightly annoyed. Perhaps this is because the model, Gina’s daughter, Emma, then fourteen, had to pose for some time in a fancy dress holding baby carrots (frog leg surrogates) in her mouth. Despite a trip to Starbucks, Emma’s usual “payment” for modeling for her mother, Emma afterwards remarked dryly that she greatly prefers not having props in her mouth.

Pop Go the Paintings

Gina Pfleegor’s style of popsurrealism—with daughter Emma as the model for her damsels—proves to be both popular and provocative.

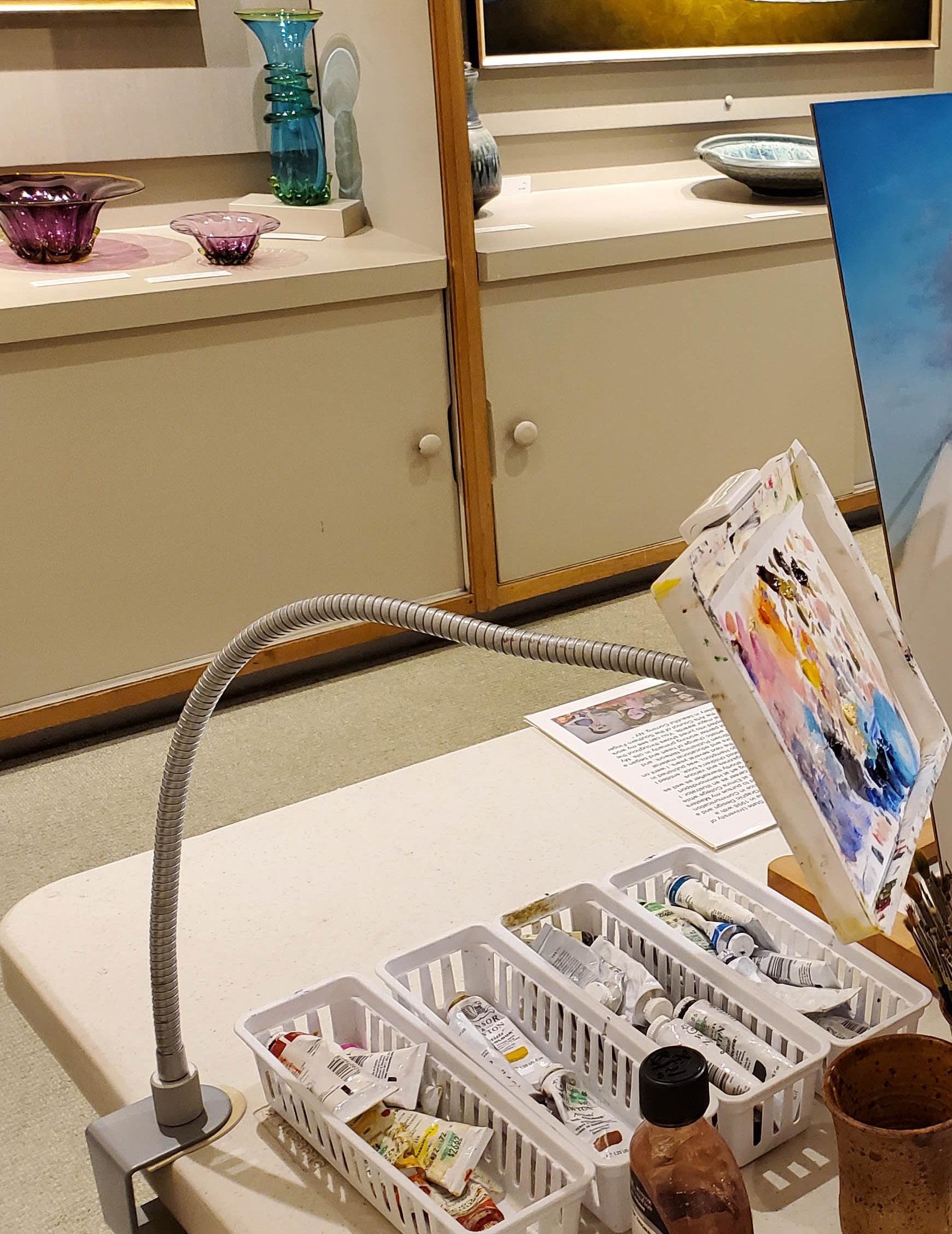

Courtesy West End Gallery

Warriors continued from page 6

The painting won the Four Columns prize from the Arnot Art Museum at its regional show, and it’s one of two times (so far) Gina has attained it. When Plot Twist was exhibited at the West End Gallery in Corning, owner/director Jesse Gardner bought it. “I almost have a shrine to it at home,” Jesse says. “It means a lot on so many different levels. Her artwork is powerful. She has a lot to say.”

Fun, fantasy, and empowerment are central to Gina’s paintings. Clearly the work of someone who loves what she does, her work invites the observer into an often-surreal universe that somehow makes perfect sense. Find that universe at the West End Gallery (12 West Market Street, Corning) during its Spotlight show featuring Gina, Trish Coonrod, a still life painter, and Bruce Baxter, an interpretive, Impressionistic-style painter, three treasured artists with very different techniques. The show opens September 5 and will run through October 9. Each of the artists will come in to do a live painting demonstration during the show (dates and times to be announced on the gallery’s website, westendgallery.net).

Tell Me a Story

Whether a standalone piece like Plot Twist (top) or illustrations for a children’s book, Gina Pfleegor’s paintings tell a tale.

“It’s a good opportunity to meet the artist if you haven’t already met them,” Jesse says. “And to get a better understanding of the creative process. It’s not just oil paint and canvas, it’s the decades of experience the artists have learned from.”

Control This!

Gina has always expressed herself via drawing and painting, devoting hours at a time to art even before she could read. “If you’re interested, you do it more often. I did it all the time. It might take a certain level of natural ability, but there’s a lot that can be learned.” There’s a smile in her voice whenever she talks about her art.

Her first teacher was her mother, a landscape painter who taught Gina to work in watercolors, convinced the oils and the solvents involved in using oil paints gave off fumes too toxic for a young person. Her great-grandmother was also a watercolorist. In college—she attended SUNY at Fredonia—Gina majored in drawing, but admits, “I hated painting with a passion.” When she tried, her professors told her she had to “loosen up” and criticized her work as being too controlled, too “tight.” “I hated loosening up,” she says now. “I didn’t want to do that, and now I’ve found success at what they told me not to do.”

After Gina began teaching art in the Hammondsport School District in 2001, where she’s spent her entire teaching career, she began sending her resumé to children’s book publishers. At the time she thought she might want to write a children’s book, and this was her way of testing the waters. The powersthat-be loved her drawings but asked her to instead paint the illustrations they needed. Could she paint as well? “Of course,” Gina answered them, thinking, I’m going to learn [oil painting] right now!

Luckily, the East Corning artist had resources nearby. “It’s such a strong arts community,” she says. “It’s a great place for artists to live. We have so many different kinds of arts and artists in this area.”

(2) Courtesy Gina Pfleegor

As a mostly self-taught painter, she took a class at 171 Cedar Arts Center with Dustin Boutwell, who teaches oil painting and was the 2015 and 2019 recipient of the center’s Bob Kinner Faculty Award for Teaching Excellence, to confirm she knew the techniques. By then the composition of oil paints had changed, and the solvents had become virtually odorless. Over the course of five years, she illustrated ten children’s books, beginning with I Like Gum, by Doreen Tango Hampton (Shenanigan Books, 2007).

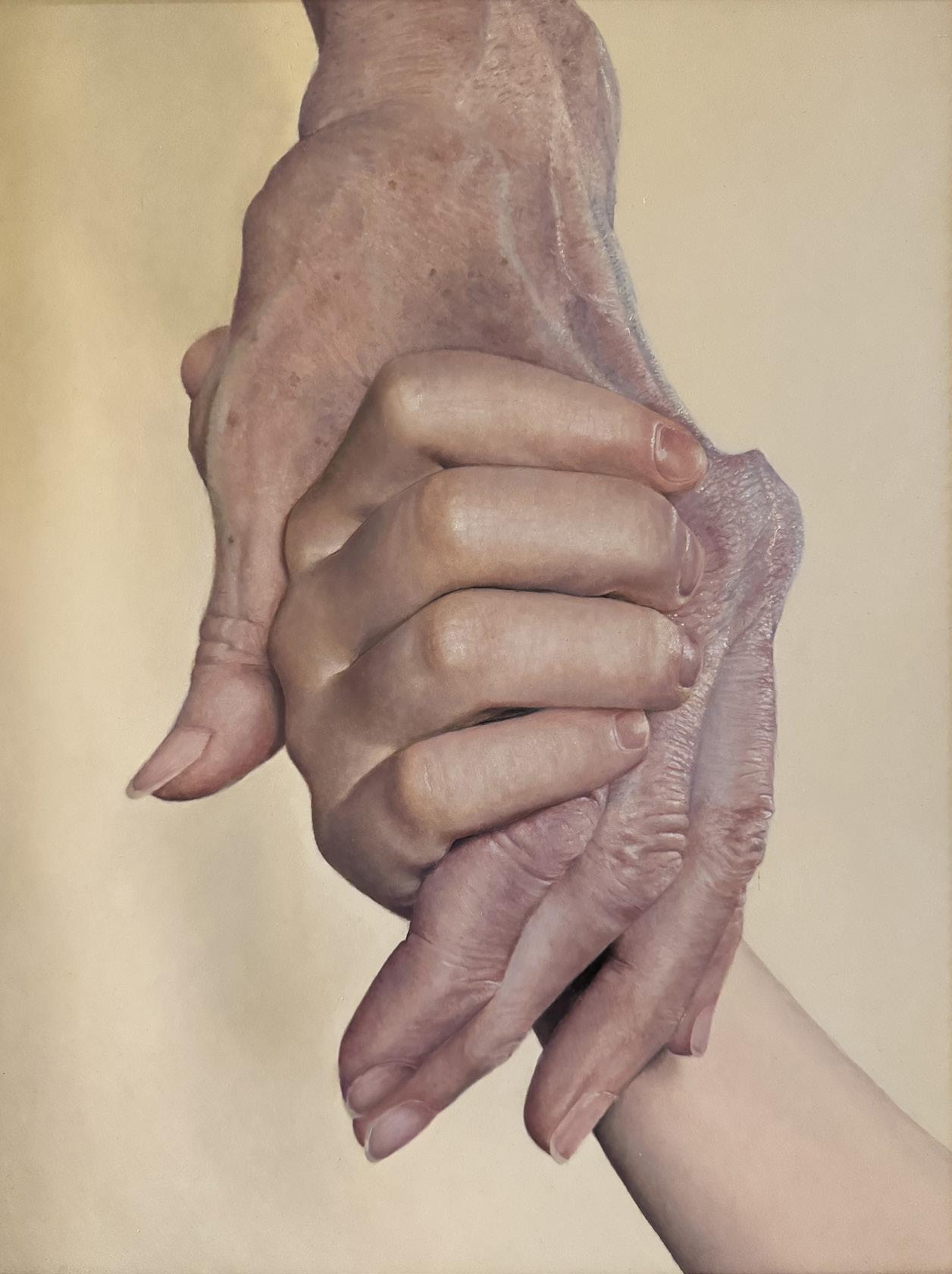

Book illustration revealed an enjoyment of painting faces, and she turned from illustration to more portraiture. The birth of her daughter, Emma, gave her a perfect model. But her home and studio were soon burgeoning with paintings she couldn’t bear to sell. Instead, she painted photorealistic still lifes, sometimes larger than life and “detailed to a T,” as Jesse says.

“Her talent was always evident. Then five or six years ago she started to do something different, a pop-surrealism,” she continues. “We could just see when she did this shift, she blossomed and found her voice as an artist. We could see that she had tapped into something, something she’d been looking for, for years. And when she found her artistic voice, the voice was beautiful.”

The term pop-surrealism is often applied to images painted in a flat, graphic style. But Gina’s brand is seasoned with the depth, skill, and precision of classic, Old Masters paintings. “Combining the photorealistic style with a surrealistic look reflective of my days doing illustration gives me the best of both worlds,” Gina says.

“She puts her thumbprint on it, makes it hers,” Jesse says of Gina’s unique style. “When you see one of her paintings, you know it’s a Gina Pfleegor.”

Changing her style “from hyperreal to surreal means I can change things or alter how old she is,” Gina explains. The characters in her paintings range from young girls to young adults, their faces reflecting a variety of moods, hair, eyes, costume, and expression. Surrealism also offers an opportunity to use the elements in a painting to tell more of a story, both an overt one and one more subtle for the viewer who spends a little time with it. It also allows Gina to concentrate on subtleties like the quality of light.

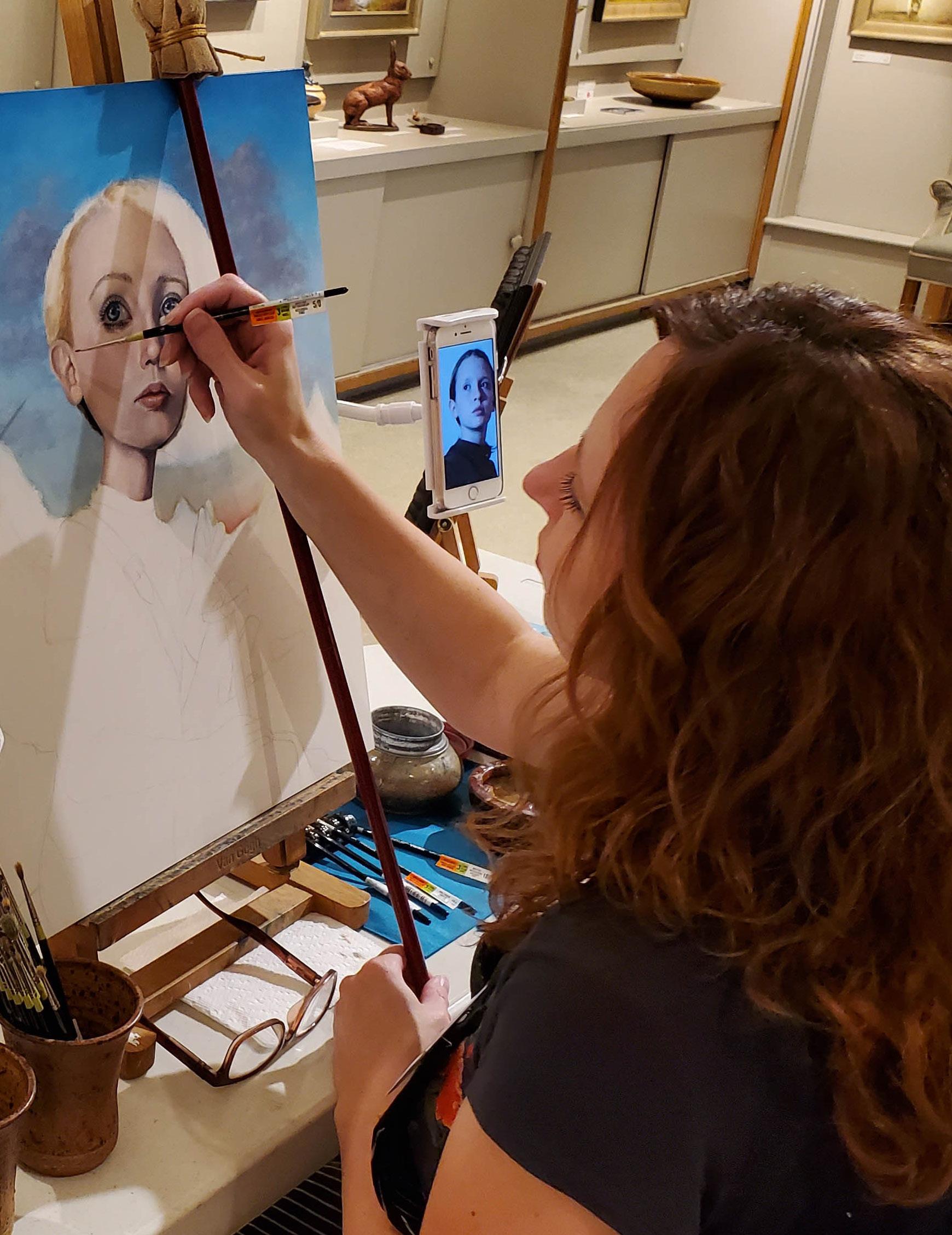

The Eyes Have It

Gina Pfleegor consults a tablet with a photo of her daughter, Emma, so she can enlarge details, seen here as she works on the eyes for All the King’s Men

Artistic Determination

As she notes in her artist’s statement, “In my more recent series of paintings, I found myself drawn to a subject I know well, that balance of feeling strong yet feminine as a woman in our society today. Attempting to depict a sense of authenticity regarding what this can often feel like, I use symbolism to show that we can be both without sacrificing the other. Sensual can be strong, determined can be vulnerable, and sometimes warriors wear gowns into battle.”

Gina, too, wears determination. She’s always painted several hours a day when she isn’t teaching. She keeps an easel at the back of her classroom for non-teaching downtimes.

She says it’s good for her students to see work in progress and to learn about what goes into creating a painting. She teaches kids in grades eight through twelve; in recent years she’s found herself

teaching students whose parents were in her classroom during her initial years as an instructor. One of her early students even went on to teach art in another nearby district. Her pupils have been among those who have encouraged her to enter her paintings in contests, both local and worldwide. And they’ve cheered for her when she won prizes and recognition.

In her classroom, students can watch her work, learn how she applies a technique she’s discussed with them, and ask questions. “They can see I’m right there with them in the trenches of doing these things,” Gina says. When asked whether she has a favorite, she laughs, “They’re all my favorite student!”

Her home studio is a tidy, minimalistic, quiet space where she can work for longer stretches of time. No wild creative messes to be found here. The walls and floors are neutral beige, the paints and materials, costumes and props are tucked neatly away when they’re not in use. On one side of the room, there’s a photo setup where Emma sometimes poses in costumes gleaned from a Salvation Army

thrift store. Mother and daughter work mostly harmoniously, though Emma’s been heard to mutter, “How long is this going to take? Please tell me I don’t have to do an outfit change.”

Gina calls Emma her muse and says she instinctively adjusts her head and body into the look Gina’s hoping for. Their mother-daughter collaboration seems intuitive. “She knows the look I want, the angle I want. I know she’ll get it,” Gina says, adding with a sigh that she’s not quite sure what she’ll do after this year when Emma graduates from high school and goes on to college.

From Emma’s point of view, “It’s not too complicated,” she says. “She [her mother] usually has a pretty good idea of what she wants me to do, and I’ve gotten used to it.” Gina’s instructions for posing tend to be subtle, like, “This is the vibe,” Emma reports. “There was one she did of me as a mermaid. That one was really cool. But it was less in the posing and more like she turned me into a mermaid.”

Lilace Melllin Guignard

Courtesy Gina Pfleegor

Warriors continued from page 9 See Warriors on page 12

A Sense of Styles

Her current favorite painting is one she recently posed for. Ruffled features a young woman and a raven, which was on the easel when I visited. “I don’t know if I have a super-metaphorical reason [for liking the painting],” Emma says. “I just like ravens.”

The Process and the Product

After photos are taken, Gina works from those. Even then, there can be frustrations. Occasionally, if Gina feels a painting-in-progress on the easel diverges too sharply from the plan she had in mind—and interestingly, Gina comes up with the title for a painting long before the first paint is squeezed onto her palette—she’ll ruthlessly return the offending part to white and start over. When she wasn’t satisfied with the expression on the young woman’s face in Ruffled as she first portrayed it, she painted over it and began again. That kind of exactitude can mean redoing many days of work. When looking closely at her finished pieces, the complexity in layers of color and shape are evident.

Gina’s art is, in fact, meant for close perusal. Consider All the King’s Horses in the soon-to-open Spotlight show and you’ll see those horses quietly cavorting in the background, barely visWarriors continued from page 10

Don’t Call Me Honey (left) and Within Reach display Gina Pfleegor’s range.

ible beneath the gold-dusted patina, a small distraction from the girl seen in the central space of a cracked egg. Or another where butterflies flood into flight through the door a young child has casually opened in her midsection. Or the bees flying in the background of Don’t Call Me Honey, a depiction of a sharp-shouldered young woman warrior resolutely holding a sword.

“I definitely have a general theme of…I don’t want to say women’s empowerment or women’s experiences—that’s not what I thought of setting out to do but it sort of evolved,” she says. “It comes up again and again, the balance of femininity and strength.”

While Gina admits to consciously adding symbolic elements to her work, and being gratified when a viewer, reviewer, or purchaser recognizes them—“Cool, they got that!”—she can also be astonished when someone draws a new meaning from a painting. For instance, the purchaser of an earlier painting of a woman blowing dust that transforms into birds winging away was captured by the visual representation of her grown children who had left the nest to embark on lives of their own.

Her work has earned notable awards. In addition to the

(2) Courtesy Gina Pfleegor

The Lintel Things that Matter

Thomas Putnam stands in the front doorway of the Hamilton-Gibson House holding the book that’s at the center of his upcoming one-man show.

Long Overdue

Thomas Putnam Returns in the One-Man Show Underneath the Lintel

By Carol Cacchione

Imagine a librarian, leading a life of quiet monotony, checking in books that have been returned through the overnight slot at a library in Hoofddorp, Holland. One day he finds in the bin a tattered Baedeker’s travel guide, 113 years overdue. Rather than reshelving the book, he surprises himself by embarking on an around-the-world quest— from a laundry in London to a transportation building in Germany to a post office in Dingtao, China, and from there to New York and Australia and beyond. His journey takes him across several continents and two millennia in search of the person who borrowed the book. And, more importantly, to find out why it took so long to return.

That’s the premise of the play Underneath the Lintel, by Glen Berger, a Hamilton-Gibson Productions staging on September 26 to 28 and October 3 and 4 at the Warehouse Theatre in Wellsboro.

“It’s a twisty mystery of a tale,” says Thomas Putnam, paraphrasing a line from the play. He’s the artistic director and founder of the community theater company also known as HG, and he’s reprising his 2008 role as the librarian. It’s a one-man show that resonates with him.

The librarian is the sleuth. He collects

clues in his travels: significant scraps that point to the identity of the perpetrator of the long-overdue-book crime. A pair of well-worn trousers, a used tram ticket, a veterinarian’s report on a lost dog, a love letter, a receipt cryptically signed only with the initial A followed by a period. Whether it’s a man, a myth, or a miracle he’s chasing, the librarian is ultimately on a journey of self-discovery.

As the lights come up, the librarian— looking a bit like TV’s rumpled detective Lieutenant Frank Columbo—shuffles onto the stage. The set is pared down to a chair and a chalkboard, a screen for showing slides, and a slide projector. He carries a battered suitcase. Inside it are the clues, or what he calls “the evidences.” They are each meticulously researched, catalogued, and labeled with an identification number. After all, the librarian is adept at these skills by virtue of his profession.

Around his neck on a cord he wears a date stamper which contains, in the librarian’s words, “every date there ever was.” He elaborates on its significance for the audience, spinning the mechanical dials. Everyone’s birth date is in the stamper. Death dates, too. We’re just not aware of them yet.

Apocalyptic disasters take place on any given day, as do commonplace fatal mishaps. “Still. We shall proceed,” he says, a catchphrase repeated throughout the play. Life goes on, as has HG since its inception thirty-five years ago.

Thomas, born and raised in Pontiac, Michigan, spent every summer of his youth in Wellsboro, where his mother, the daughter of Dr. Jesse and Alma Webster, grew up. It was his grandmother Alma who persuaded him to come to Tioga County in 1974 to earn his degree in education at what was then Mansfield State College. He found jobs after graduation in both public and private schools, and loved teaching.

And then, in 1991, he and some friends decided to start a community theater.

“I wanted to be in plays, I wanted to direct plays, and there was nothing around at that time as far as community theater in Tioga County,” Thomas explains. “We organized our first theater in a little church on Route 6 east of Wellsboro. It was a former farm implements building. There was a room in front for the church, and a huge garage in back where the tractors and machinery used to be serviced. There were big

See Librarian on page 16

Pennsylvania Lumber Museum

(814) 435-2652 lumbermuseum.org

bay doors we could open up. We bought some scenery lights. A guy in Mansfield who ran a boxing gym gave us a platform we pushed down to one end for a stage. We borrowed folding chairs from the chamber of commerce. The first play we did was The Miracle Worker.”

He laughs, remembering all the power washing it took to get the machine oil off the floor before they could stage that first production. But there was an immediate payoff. “It was summertime. We kept the garage doors open during the play and poured lemonade at intermission.”

Thomas and his theater company (named for his maternal grandmother Alma Hamilton Webster and his paternal grandmother Clara Gibson Putnam) wandered around Tioga County in search of a permanent home. They staged productions at local elementary and high school auditoriums. They performed in the old Davis Furniture building and the county courthouse in Wellsboro, and at Mansfield University.

Eventually they set down roots at the Warehouse Theatre, now part of Wellsboro’s Deane Center for the Performing Arts. The old brick building was once a car repair garage, reminiscent of the old farm implements building where HG got its start. The first play they staged at their new home was Underneath the Lintel.

“The artistic planning committee wanted to bring back some plays from the past to commemorate our thirty-fifth season,” Thomas says. Lintel with its cast of one seemed to be a good balance following Annie, HG’s summer musical with its cast of over fifty. A bit of a mystery, though, surrounds “the evidences”—all the scraps the librarian, AKA Thomas in that first staging, uses to determine who borrowed the Baedeker. They are nowhere to be found.

“I know we had them in a box in the back room,” Thomas says. “I remember saying to myself, ‘Will we ever use them again?’ I just don’t remember what the answer was.” Like the librarian, ever in search of clues.

Near the end of the play, the librarian tells the audience he deliberately carved the words “I WAS HERE” with a sharp letter opener on his work desk at the Hoofddorp library, lest he be forgotten. Thomas Putnam has metaphorically carved those words on the community theater he founded.

“The librarian, in spite of all that happens along his journey, is determined to find worth and beauty in life, and to be remembered,” Thomas says. “There are other things in my life I’m particularly proud to have accomplished, but I suppose HG is how most people will remember me.”

He pauses for a moment. “Still. We shall proceed.”

There will be time for a lively give-and-take dialogue between the audience and Thomas and his stage crew after each performance. Run time is approximately seventy-five minutes with no intermission. For tickets, visit the HG webpage at hamiltongibson. org or hgp.booktix.com.

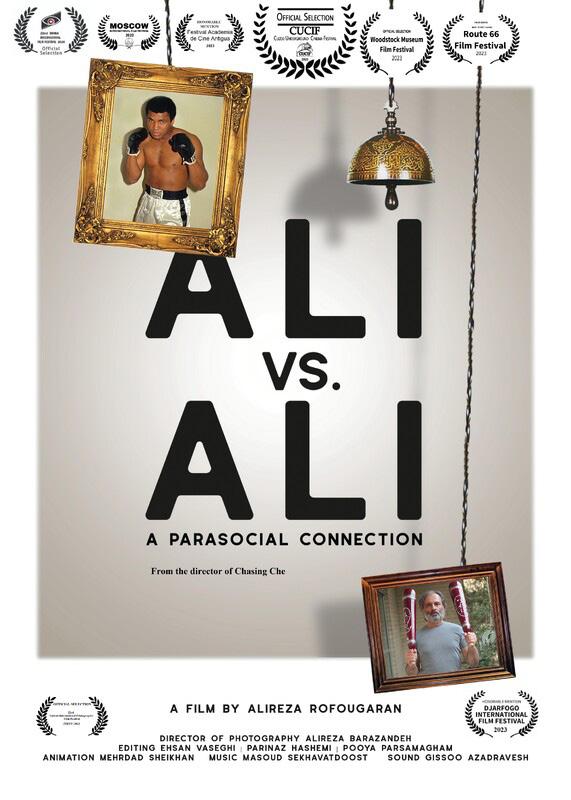

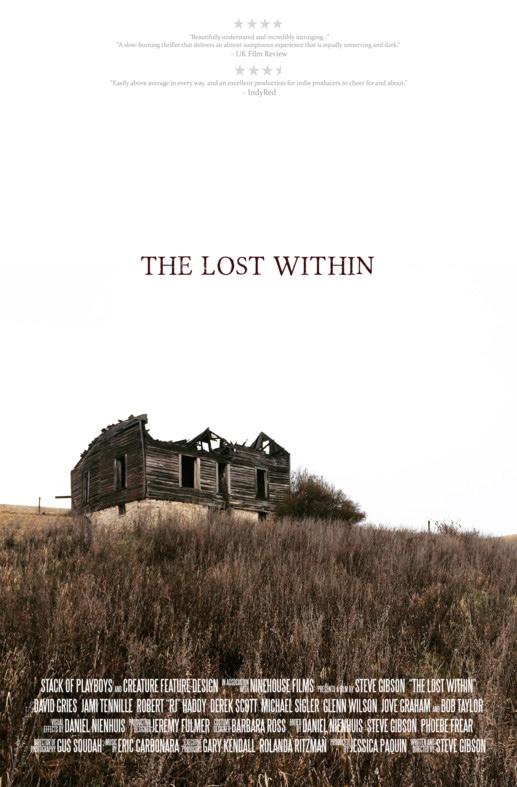

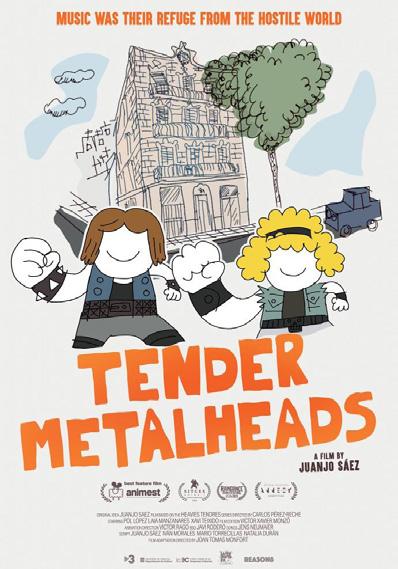

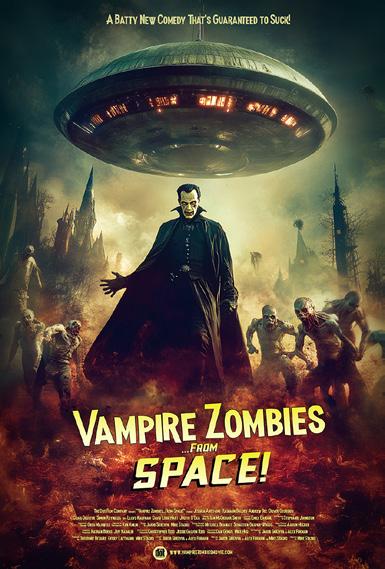

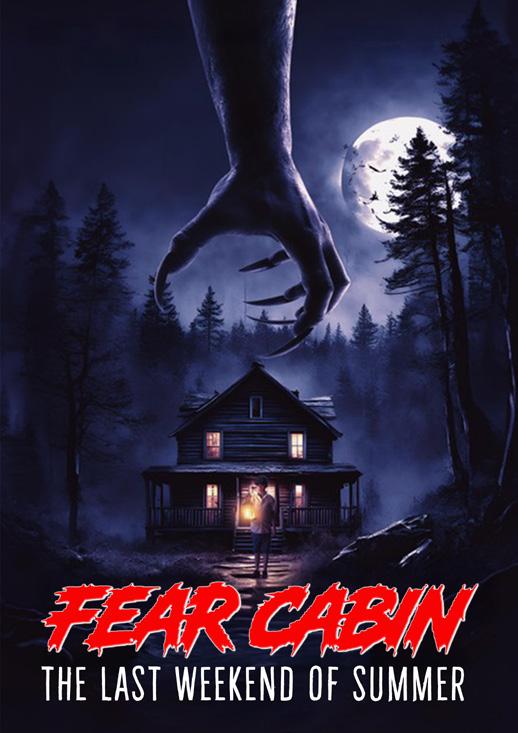

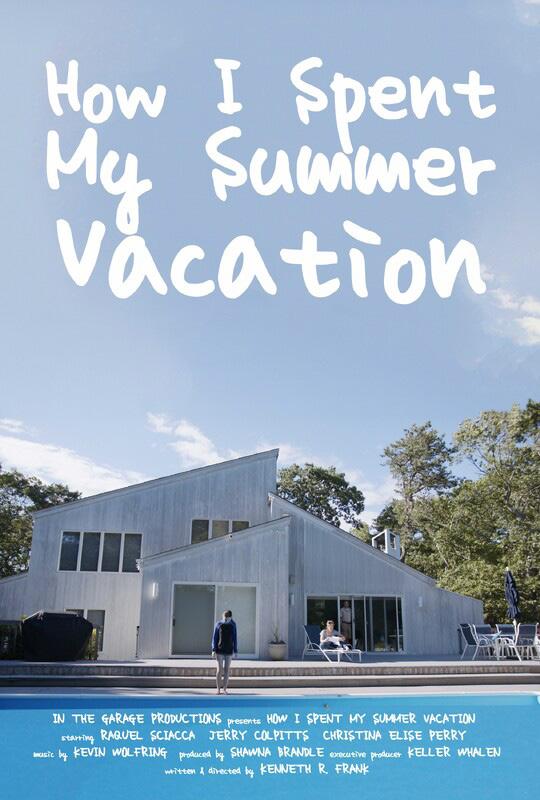

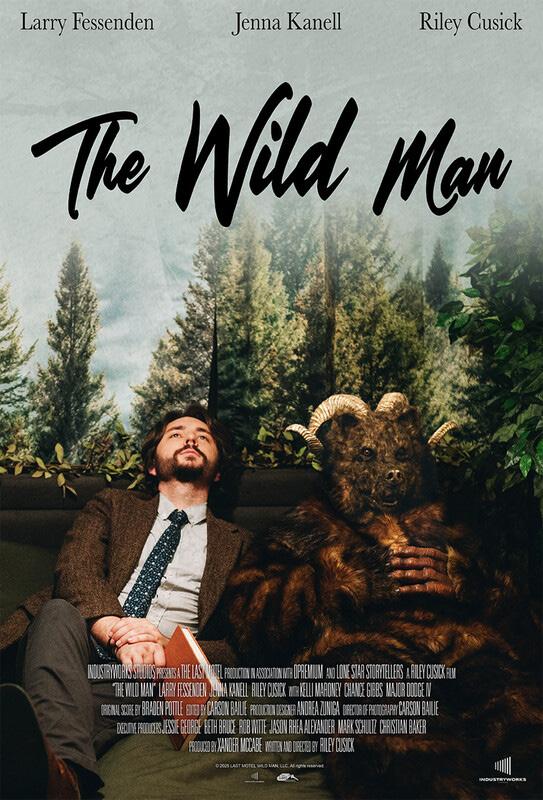

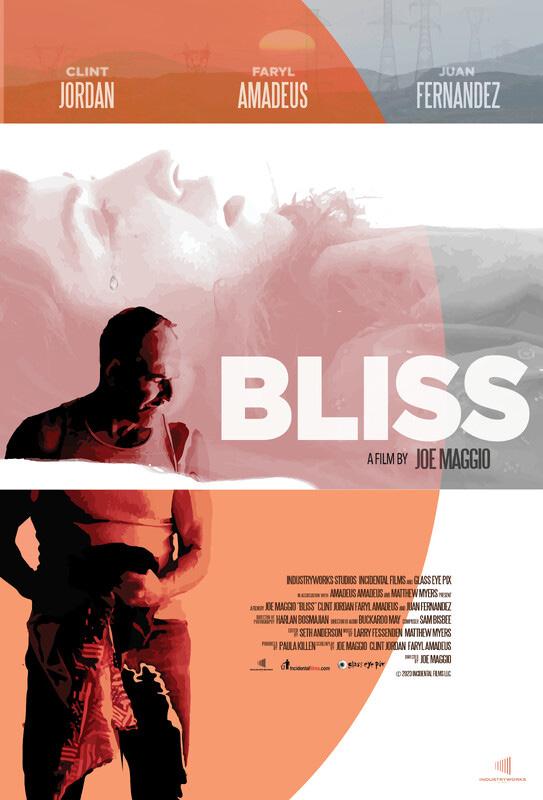

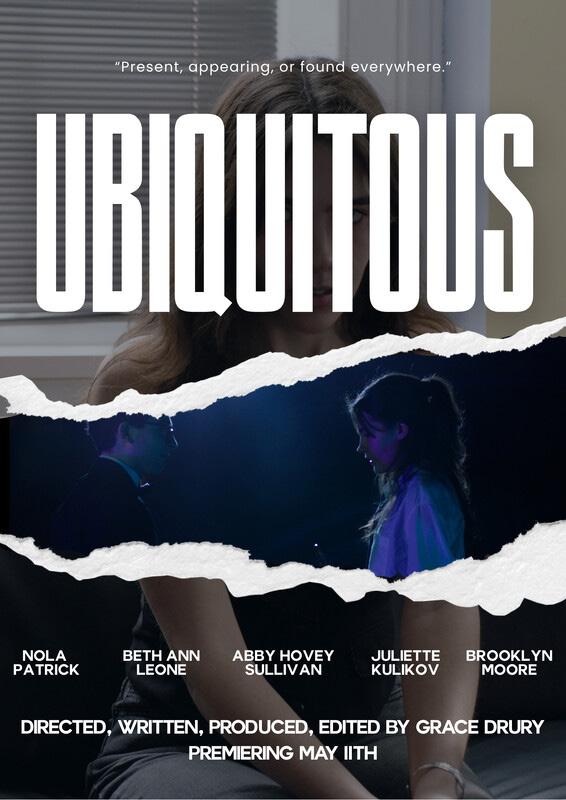

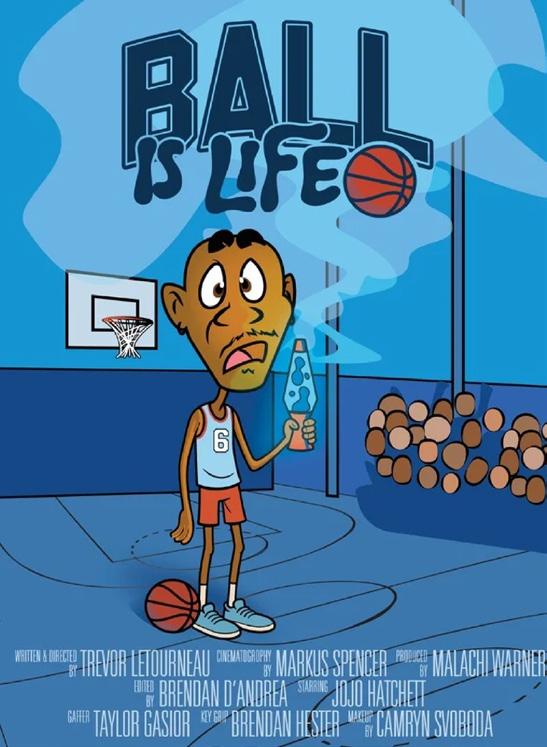

Sure. You can go to the Sundance Film Festival, or South by Southwest, Telluride, even Cannes. Chances are, you’d see celebrities from the film world and beyond. But for an experience seeing movies done by independent filmmakers from all over the world and as close as your own backyard, set your sights, and buy your movie snacks, right here in Lycoming County for the Susquehanna Film Festival, September 19 to 21 at the District Cinema in Muncy. Film festival promoter, film producer, and musician Tim Yasui is no stranger to either the international world of film or to the Williamsport area, where he grew up.

“For years I had attended the Cannes Film Festival in France, the Berlin Film Festival in Germany, the Hong Kong Film Festival, and the Toronto Film Festival in Canada, amongst others, and it has always been a dream of mine to one day build my own film festival,” he says.

But it was producing Cocaine Werewolf

By Linda Roller

Film producer and Lycoming County native Tim Yasui launches a festival to showcase new, local, and international filmmakers. Action!

Bright Lights and Red Carpets Susquehanna Film Festival Premiers in Muncy

(see our July 2024 issue) with director Mark Polonia of Wellsboro that turned the dream of building a film festival into a reality right here. Tim explains, “After [Cocaine Werewolf] wrapped, I booked the world theatrical premiere at the infamous Arcadia Theater right there in downtown Wellsboro and we sold out the venue. After the Wellsboro premiere, I pitched Cocaine Werewolf to Mike Dipson who owns the District Cinema at Lycoming Valley [the old mall in Muncy], and we had another successful screening there. It was an eye-opening experience for me, as I had previously mainly been booking our films in Hollywood, New York City, San Francisco, Austin, and other larger markets. I found it so easy and enjoyable to work with the central Pennsylvania theaters that I thought it would be cool to host a film festival there.”

Jordan Musheno, general manager at the District, didn’t know Tim before the showing of Cocaine Werewolf, but he knew the Polonia brothers, and knew that screen-

ing did well, thereby paving the way for a bigger event. The District will be the venue for the entire film festival.

“We are dedicating two screens for this event on Friday through Sunday, with the awards ceremony in one of the auditoriums Sunday night,” Jordan says, adding there would be lobby space for displays and other activities surrounding the festival. “We have more flexibility, as we are locally owned. And we want to bring new film experiences to our audience.”

The call for films began in January 2025, and there were new applications until just recently.

“We received over 100 submissions,” Tim says. “In addition to eleven of the films being shot right here in Pennsylvania, we will be showing films from Japan, India, Spain, Iran, South America, and Canada—it will truly be an international festival.” Pennsylvania films are highlighted, with a special

book Shop

category for “Best PA Film,” but a few of the regionally produced films chose to compete with the world in the documentary category.

There are also categories for best student film, giving aspiring moviemakers a large venue to show their creativity in an early effort, and best short film. Those categories are not always represented in other festivals.

“There is a nice combination of both first-time filmmakers and veteran filmmakers, so I’m pleased with the balance that we’ve obtained,” Tim says. “The only rules we had were no extreme political films encouraging violence of any kind and no pornographic content, as we want families to be able to attend and enjoy our films.”

Many of the screening selections are yet-to-be-released films making their exclusive North American premiere

The awards ceremony will be open to the public and will mark the festival’s conclusion on Sunday, September 21, at 7 p.m. Award categories include Best Student Film, Best Pennsylvania-Made Film, Best Documentary, Best Short Film, Best Drama, Best

Horror, Best Comedy, and Best Animation. A panel of independent judges will evaluate the submissions to determine winners.

If that’s not enough for movie buffs, this is the second film festival starting in the Williamsport area this year. Both Tim, with the Susquehanna Valley Film Festival, and Cory Baney, who was the director for River Valley Film Festival in downtown Williamsport, had been planning and working on their respective projects for years. By coincidence, both were ready to launch in 2025.

Lycoming Arts President Debi Burch notes that there is a new energy to the Pennsylvania Film Office.

“The fact that Governor Shapiro opened up additional tax credits for film [making] in the state is one of the factors in bringing filmmakers to our area.” Debi says the interest that both festivals have generated in the area, including the strong attendance at the River Valley event, is helping the entire region be noticed by filmmakers nationwide.

“This is certainly new for our area, and unusual to have two festivals in Williamsport. But it speaks to the state of film in Pennsylvania, and the recognition of this

area as a location for productions,” she says, adding that Lycoming County has hosted an international event for decades—the Little League World Series. The network of service industries necessary for that annual event can also certainly cater to traveling film crews. From Williamsport, it is a short distance to many different types of scenery perfect for the creation of settings for a wide range of films. It’s a filmmaker’s dream location. Certainly, that is Tim’s dream, as one of his goals for the festival is to experience the success that he had with Cocaine Werewolf again in his beloved Lycoming County, and to encourage other filmmakers to explore the Pennsylvania Wilds.

Find up-to-the-minute details at Susquehanna Film Festival’s Facebook page. To purchase tickets for a single film, a oneday pass, or an all-inclusive festival pass, visit thedistrict.dipsontheatres.com.

Mountain Home contributor Linda Roller is a bookseller and writer in Avis, Pennsylvania.

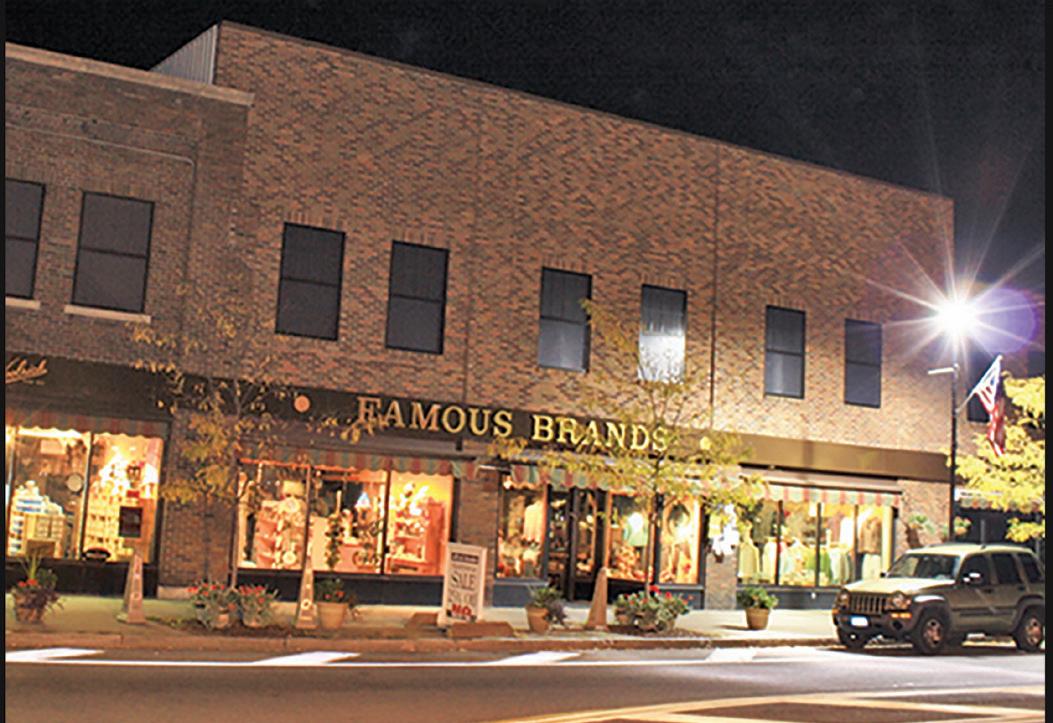

Beefing Up Education

Through PA Beef to PA Schools, Hillstone Farms provided local high quality beef to Wellsboro Area High School in 2024-25 and hope to this coming school year. Jessica Webster (left) teaches science at WAHS and often works at their Wellsboro store; brothers Todd, WAHS wrestling coach, and Garrett (l to r) run the farm.

Hillstone Beef Gets an A+

Local Smashburgers a Smashing Success at Wellsboro Area High School

By Karin Knaus

The high school cafeteria in America often gets a bum rap. Maybe being forced to take a vegetable rubbed you the wrong way. Perhaps the public school sloppy joe could never compete with Mom’s. Or perhaps you were on the receiving end of the wrath of a frustrated cafeteria worker.

Thanks to a collaboration between local school districts and Wellsboro’s Hillstone Farms, some local students’ memories of the cafeteria will likely be a lot tastier in the years to come.

If you live in or around Wellsboro, you’ve certainly heard of Hillstone Farms (see our June 2016 and June 2022 issues), and you’ve probably enjoyed the beef produced there in one of the myriad local restaurants that serve it. Truly, Hillstone’s Webster family has connections in the Wellsboro community and its school district that run deep.

I met up with Todd and Jessica Webster, fittingly, at the beef show at the Tioga County Fair in August. Todd Webster is an easygoing, sharp-witted everyman who graduated from Wellsboro in the late ’90s. He grew up on the land he now farms, and, after earning an animal science degree at Penn State, he moved to Vermont and gained some experience with meat inspection. He eventually returned to work with his dad, Tim, on their sprawling family beef farm outside of town. Today Todd and his brother, Garrett, who joined the team after graduating from Penn State with his own ag degree, run the farm. Sadly, Tim died very unexpectedly in 2022 as the result of a farm-related accident.

Todd’s wife, Jessica, herself a Wellsboro alum, manages the downtown face of Hillstone Farms in their Main Street storefront. There, they sell homemade baked goods like scones and Jessica’s famous sourdough

bread, locally sourced products like Painterland Sisters yogurt and Innerstoic ciders, and of course, their beef in a number of cuts. Their kids are even in on the business, selling their own handcrafted products like homemade granola. The business continually expands its offerings, most recently by selling skincare products made with the beef tallow from their animals. After teaching in Mansfield for a few years, Jessica returned to her local roots in 2017 to teach biology and earth and space science at Wellsboro Area High School.

This connection to their home school district goes back a generation, too, as Todd’s mom, Karen, was also a teacher in the Wellsboro Area School District for more than thirty years. She even taught this author the rules of football and a unit on table manners in ninth grade. All this is to say the Webster family’s impact on the WASD community is a big one.

Wade Spencer Cameron Clemens

So, when Katrina Doud, director of food and nutrition in the district and no stranger to sourcing locally when she can, learned of a grant program through the PA Beef Council, she knew just whom to call. She reached out to Hillstone Farms, and the Webster family was interested. They applied to be suppliers through the program.

The PA Beef Council’s PA Beef to PA Schools program works to connect schools and their food service programs to local beef producers. The idea is designed to increase the beef in school lunches while supporting local farms and decreasing food insecurity for the people in our communities.

Started by the PA Beef Council, additional funding for the program comes from the state’s Department of Agriculture and other partners, including some larger farm donors. According to Todd, one dollar for every animal shown at places like our own county fair also goes into this pool of funding. The beef Hillstone Farms provides to local school districts is paid for in half by these PA Beef Council funds, and half is paid by the school district.

Todd explains that there are a few key requirements to be a supplier. The beef has to be Pennsylvania beef, it has to be processed by an inspected USDA facility, and the supplier has to be able to deliver the beef to the school. “That was easy, because Jessica works there,” says Todd. Last year, Hillstone provided Wellsboro with fifty pounds of beef each month.

During the 2024-2025 school year statewide, this program served 120 school districts in forty-eight counties on a monthly basis. Twenty-six farms were able to serve their beef to a total of more than 220,000 students statewide. In addition, the program hosts PA Beef Days, which increases the number of school districts served over the course of the school year to 300 during those special events when local beef is served for lunch.

As a wrestling coach for the district, Todd was also able to witness firsthand the impact their product had. He recalls that on the day the cafeteria served Hillstone smashburgers—a cafeteria sellout—he rode the bus to a wrestling match with a group of athletes who’d enjoyed the treat that day. Students raved so much, Todd joked he was worried they might not make weight for the competition.

The Hillstone Farms family hopes to be able to participate in the program again this year, but as of press time, the state budget had not yet been passed, so it’s not a sure thing that the money will be there. Hillstone has also recently provided some beef to Galeton and Southern Tioga school districts through the same program.

The Websters are humble about their part in connecting their product to the district. Jessica points out they are invested in the Wellsboro Area School District—not just because they attended or have kids there, but for their nieces and nephews, and friends’ kids, too. Todd says he would love to see more school districts participate, and that they all have local beef producers who could get involved. It’s not just about business to them. At the end of the school day, it’s about what’s best for kids. Says Jessica, “It’s getting good food back into the schools.”

Nessmuking About

Lobster Monster of the Woods

By Lilace Mellin Guignard

On a Friday afternoon well into late summer, I realize I have no plans after work. Finally, a free evening! Texting a friend who a month earlier had offered to take me mushroom hunting, I ask if it is too late (and hot) in the season.

She quickly responds that she and her partner in grime have been collecting chanterelles out their backyard where it is shady and are heading out this day to finally harvest a chicken of the woods they’d been letting grow. “We also found a delicacy back there, a mushroom that gets turned into a different kind of mushroom by another mushroom.” Can I be at their house at 4:30? Indeed, I can.

Mushroom hunting is not a hobby someone should charge into since several deadly mushrooms can be found in our woods, and I chose my guides carefully. I’ll call them Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum. Let me be clear: this is not a how-to column. Perhaps this is a why-to column—or a why-not-to column, depending on how you feel at the end. I am instructed to wear shoes I don’t mind getting muddy, so I show up in shorts and calf-high muck boots/

waders I’ve never worn before. Wal-Mart specials. Tweedle Dee looks at me and asks if I want to borrow a water bottle or take a beer. She’s zipping up a small backpack. I say, “I thought we were walking in your backyard?”

“We’re starting in the backyard.”

“How long will we be gone?”

“A few hours.”

I accept both the water bottle (she puts it in her pack) and the beer. I expect that, too, to go in her pack but Tweedle Dum pops the top on his and says, “This way we’ve drunk them by the time we get to the forest.” A little liquid bread sounds good, since I skipped lunch. Then out the yard and down a hill we go into the wilds of Wellsboro.

The grass is really high, but they’ve more or less tramped a trail. Tweedle Dum charges ahead, while I slide around in my boots. Near a pond’s edge the footing becomes slippery and uneven. A little lightheaded, I’m thinking a beer on an empty stomach wasn’t the smartest move. I fall a bit behind, but he waits inside the edge of the woods where the temperature drops.

There has been enough moisture that in hemlock woods this thick mushrooms have been able to thrive. Yesterday the rich soil and dried beech leaves were dotted orange with chanterelles.

Both my guides pause and look around. Apparently, they were expecting more orange, but they laugh. Tweedle Dum explains that we are competing with critters and weather. “I’ll take a small mushroom versus nothing the next day,” he says. “Younger mushrooms taste better. Chicken nugget size.”

“Sometimes we don’t find anything,” says Tweedle Dee. Mushrooms there the previous day can disappear like Brigadoon. Instead of seeds, mushrooms release spores as fine as the fog that cloaks the fictional Scottish town. When they land in a hospitable place they germinate and create the mycelium. This is the hidden soul, what you can’t see that makes the mushroom a mushroom. That which we call mushrooms are the fruit that some fungi produce. Depending on your perspective, that fruit’s purpose is either to produce spores or be the centerpiece of your favorite cream sauce.

(3)

Lilace Mellin Guignard

Lobster mushroom

Chicken of the woods

A haul of chanterelles and lobster mushrooms

After dispersing the spores, the mushroom dies back—but it’s not really dead. The mycelium waits unseen for an opportunity to rise again. Their lifespan is infinite, though they can be killed.

By letting the large cluster of chicken of the woods grow one more day, Dee and Dum were taking a risk, and it pays off when we reach the log with the meaty orange fans. My guides pull out serrated knives and bags. “Chicken and biscuits tonight!” Tweedle Dum crows. He’ll batter and fry it.

Nearby they show me some old chanterelles, ones that are soft and spongy after releasing their spores—but, look, there are some we can gather. They point out what to look for underneath and how to pull the stem apart to be sure I’m getting chanterelles and not jack-o-lanterns, which will make a person sick. I borrow a knife to collect some, sawing the stem above the ground rather than plucking it, to leave the mycelium intact to fruit again.

“Lobster!” Tweedle Dum shouts. He reaches underneath a bulge in the forest floor duff and gently tilts it, brushing of the dirt and needles. The orange is more vibrant than any of the other orange mushrooms today, almost red liked cooked lobsters with white flesh inside, but how did he know it’d be there? “Look for shrumps,” he says. Around us are hemlock trees and ghost pipes, a non-edible non-photosynthesizing fungus distinctive for its translucent colorlessness. Their presence is a tip-off that lobster mushrooms might be hiding under dirt humps because they are both parasitic and need similar conditions to thrive.

Most mushrooms, including chanterelles and chicken of the woods, are saprophytes, feeding off decay and reanimating, like zombies. Ghost pipe and lobster mushrooms are parasitic, making them more like the aliens in my monster analogy. Nothing to be afraid of! Lobster is a good monster, at least from a human perspective. Hypomyces lactifluorum spores look for Russula brevipes, which like to grow in symbiotic relationship with conifers like hemlock, and form an orange mold that inverts the cap into more of a trumpet shape and turns the bland or bitter white mushroom into a tasty treat. Around us we can see some of both.

Finally making use of my waders, I slosh through a marsh, squealing when a snake swims by, almost get a boot sucked off, and claw up the rise across from my friends. Ah, here, on land far away from the ocean or the seafood section in Wegmans, I find my first lobster and give a yell. The size of my palm and a deep orange, it is firm and easy to brush the dirt from. Underneath are ridges instead of gills. After adding it to my bag, I gather a few smaller ones nearby.

Later, standing over a cast iron skillet in my kitchen, amazed, I inhale the unmistakable smell of seafood from the chopped pieces of lobster mushroom sizzling in butter. Across town, Tweedles Dee and Dum are frying up “chicken” filets, saving their “lobster” for tomorrow’s pasta. The feasts and fun of monster, er, mushroom hunting have hooked me, and I can’t wait to venture out with my friends again soon. Depending on the weather and our timing, we should be able to forage for these through early fall. Tweedle Dee told me that once the leaves start falling, it’s harder to spot our favorite orange ground mushrooms in the autumn carpet.

But that won’t stop us from trying. After all, local lobster is worth the effort.

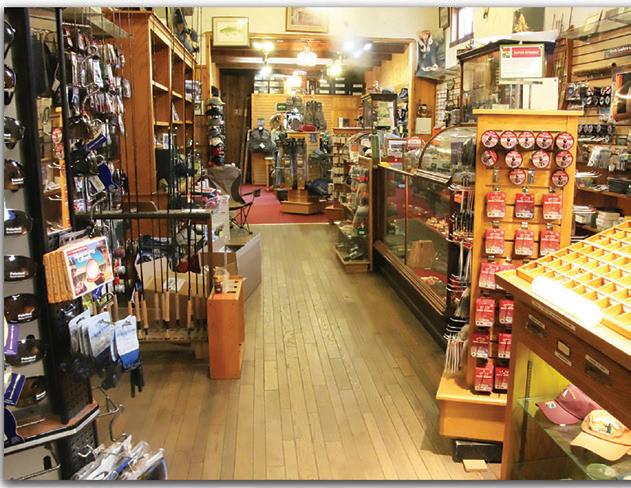

Run Tackle Shop

Soul Mates

At Armenia Mountain Footwear, they do more than match people to shoes; Jen Casler (left) helps fit shoes for people with specific foot issues, and her father Jack Kuyper (above, left) and husband Kirt Casler craft padding, supports, and patches for new and well-loved pairs the old fashioned way.

If the Shoe Fits

Troy’s Own Cobblers Give Their Customers Happy Feet

By David O’Reilly

The name of their store—Armenia Mountain Footwear—seems to say it all. They sell shoes, right?

Indeed they do. But the sight of co-owner Kirt Casler with a needle and leather thread in hand, stitching a boy’s baseball glove, suggests this is no ordinary shoe store. The boy has a big game coming up and his glove “needs some repair,” explains Kirt, who points out the frayed seams. “The family asked if we could fix it and we said yes.”

Kirt’s father-in-law takes a puff on his corncob pipe and leans back at his workbench.

“Yeah,” says Jack Kuyper, eighty-six. “We shouldn’t, but we do everything.”

Yes, Armenia Mountain Footwear is also an old-fashioned, family-run cobbler shop. It repairs and replaces heels and soles, tongues and bootstraps, and can keep a good pair of shoes or boots going for years.

But Armenia Mountain’s “everything” takes shoe repair to still another level. The

two generations who run the store out of a grand white house on Canton Street in Troy are what’s known as pedorthists, or orthopedic shoemakers. A dwindling breed, they modify and reshape footwear for customers whose feet—and hence their shoes—need special attention. The smiling public face of this side of the “everything” is Jen Casler, Jack’s daughter and Kirt’s wife, who learned the pedorthist trade at her father’s side.

“Dad wanted to help people with their foot problems,” explains Jen, fifty-nine. “But he couldn’t afford to go to the school in Chicago that taught [pedorthics], so he studied out of books.” Here she pulls three books from a shelf: Contemporary Pedorthics, The Human Foot, and Professional Shoe Fitting. Jack founded the store in 1972 after a decade building and selling log homes. Jen and Kirt bought the business from her parents in 2001.

“Then I got demoted,” Jack says with a laugh. “I used to be the shoe man. Now I’m

the glue man.” A devoted trout fisherman, he still works at the shop two days a week. With his white hair, that corncob pipe, and a long leather apron, he looks like a cobbler out of central casting.

He lifts up a gray-green boot. It looks like any out-of-the-box boot until he points out a three-inch thick layer of black rubber running full length above the heel and sole. It’s for a man with one leg shorter than the other who “injured it in a motorcycle accident.” Jen then points out a pair of beige, nearly round, thick-soled shoes. Kirt modified them for a customer with profound diabetic neuropathy, and Jen added arch supports and interior padding.

A few minutes later she’s demonstrating how the “skiver” and “five-in-one cutter” work—both machines are nearly a century old—when Kirt lets her know that “Denny’s here.”

(2) Wade Spencer

412

412

Shoe continued from page 26

She heads out to their capacious fitting room, where dozens of hiking boots, cowboy boots, dress shoes, and walking shoes line the shelves. (Most of the product line qualifies as “sensible.”) Denny Boyd, seventy-five, looks up from a long, pew-style bench and gives her a big smile. Jen greets him warmly and hugs Denny’s wife, Vicky. As Jen seats herself on a low fitting stool, Vicky explains that in 2009 Denny, a truck driver, had a “paralyzing stroke” on his left side so profound that doctors told her he would “never get out of bed—and never know me.”

And yet Denny not only recovered his speech and mobility, he chops wood and walks regularly from their home in Leroy to Sunfish Pond atop Barclay Mountain, a four-mile loop. But his left foot lost size with the stroke, and so today he’ll need extra padding and lifts to make the left half of his pair of new Carolina hiking boots fit properly.

Jen asks if the left foot is giving him any pain. He says no, and she measures both feet with a tape measure.

“Jen has helped him so much,” says Vicky. “They know more about his feet than I do.”

Armed with his measurements, Jen heads back to the workroom and twists the knob on a giant Rolodex. “Our Amish computer,” she jokes. “Look. I have a card on him.” Sure enough, it shows Denny bought his first footwear here in 1987, and that they added a “diabetic heel lift” to it for extra cushion. The card also notes that Denny likes only one extra pad on the tongue of his shoes, so to “snug up” his new left boot Jen must also add padding to the sole. She removes the full-length arch support that comes with the boot, traces it on a rectangle of eighth-inch-thick crepe, and cuts it out. Next she runs its through a machine that feathers or skives its perimeter so that it lies snugly inside the boot.

She emerges with the modified footwear, puts it on Denny, and tightens the laces.

“It’s still slipping,” he says.

“Not a problem,” says Jen, who takes it back to the workroom, pulls out the crepe, and replaces it with a sixteenth-inch-thick liner of cork. He tries it out but shakes his head and asks her to tighten the laces.

“All right,” she says with a laugh. “I’m going to do it with all my might.”

Again he takes them for a spin but thinks the left is still slipping.

“How about you try them for a few days?” she asks. He agrees, and he wears them to the checkout counter. Jack comes out to greet them, and they chat.

“We’ll see you in a week if we need to,” Denny tells Jen, and they head out the door.

“It might take two times and it might take ten,” says Jen as she restores Denny’s updated card to the Rolodex. “But that’s the only way to do it.”

Award-winning journalist David O’Reilly was a writer and editor for thirty-five years at The Philadelphia Inquirer, where he covered religion for two decades. Contact him at davidcoreilly@gmail.com.

Gwine to Run All Day

Racers in 2024 beginning the footrace that commemorates the notorious and melodious horse race of yore.

Sixty Years of Camptown Races

Stephen Foster’s “Doo-Dah” Lives on in Bradford County

By Maggie Barnes

AStephen Foster composition from 1850 and a run through the woods in Bradford County. What’s the connection? Well, the song was “Camptown Races,” one of the gems of the minstrel era of American music. It’s a raucous ditty about transient workers who get up a horse race to wager on using a five-mile track near Camptown around 1840. Such gambling was considered immoral, giving the song a naughty tone that the public loved. A slightly bizarre tale ensues including a cow on the track that gets flipped on a horse’s back, and a horse who gets stuck in a mud hole—“Can’t touch the bottom with a ten-foot pole.” And we can only speculate as to the motivations of the crooning “Camptown Ladies.” Foster was known for

his lively rhythms and bouncy lyrics that were ideally suited to the minstrel shows of the time.

Stephen Foster was born in Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania (a neighborhood in Pittsburgh, not the borough in Tioga County), on the Fourth of July, 1826, which is fitting considering his songwriting career celebrated much about life in America. He spent time in Bradford County and was educated at academies in Allegheny, Athens, and Towanda. His brother, William, was an apprentice engineer in Towanda, met a man there learned in music, and suggested to Stephen that he should train with him. It’s not a stretch to imagine that the brothers may have visited Camptown during this time, providing the inspiration for “Camp-

town Races,” which was written in 1850. There’s even a historical marker near Wyalusing. Stephen attended college briefly, at Jefferson College in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. But like so many naturally talented individuals, organized education was not a priority for him. He visited Pittsburgh on break from school and simply never went back.

Sixty years ago, folks around the area wanted to commemorate their claim to fame and the Camptown Race 10k and 5k runs were born. They are always the Saturday after Labor Day, September 6 this year, in the same general area where the song takes place. A foot race seemed much easier to manage than one with horses. And the committee developed the idea to use the

Maggie Barnes

event not only as a celebration of Foster, but as a real community booster. Organizer Irene Melly says the Camptown Civic Club hosts the race as a fundraiser.

“The money allows us to support things like the school backpack program, the food pantry, the library and museum, and such,” she says. Now that’s something to sing about.

“Nature runs” or “trail runs” are a whole different animal from flat track races. After starting on a paved road, about 2.8 miles of the route takes runners right into the woods on what were once logging roads, uphill and down, dodging tree roots and loose rocks. There’s even a stream to get across, so forget about your feet staying dry. In 2024 it rained heavily, a drenching that produced what one volunteer called “a fun mess.” Undaunted, the nearly 100 runners stretched and warmed up in the deluge, with a couple commenting that they might as well get muddy, too. Everyone gathers at the starting line and the church steeple plays “Camptown Races,” with folks singing along. The gun fires and off they go! Lots of kids blast off in the 5k division with the boundless enthusiasm of youth. Older runners try to find the right rhythm. The finish brings runners to the green space where vendors, food, and live music await them.

“The first section wasn’t bad,” a runner said as he peeled off mud-soaked sneakers to the absolute delight of his children. “But the trail section was really challenging.” Another runner commented that the switch in terrain demands a mental 180 as well. “Road racing is all about pacing, breathing well, and keeping your stride. The trail course is all about simply trying to stay upright!”

For the sixtieth anniversary of the Camptown Race (find it at the intersection of Route 409 and Route 706), the organizers wanted to do something special. They added a new challenge—a two-person relay option. The first runner has the flat, grassy portion of the trail. The anchor person picks up the natural trail, complete with dirt, mud, trees, and elevation change. Assuming the pairs assign the faster runner to the first half, and the stronger runner to the second, there could be some impressive times this year.

Stephen Foster wrote some of his most celebrated songs in the Keystone state: “Camptown Races” (1850); “Nelly Bly” (1850); “Ring de Banjo” (1851); “Old Folks at Home” (1851), known also as “Swanee River”; “My Old Kentucky Home” (1853), which became the state song of Kentucky; “Old Dog Tray” (1853); and “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair” (1854), written for his wife, Jane. Despite never having lived in the South, many of Foster’s songs had southern themes.

Foster died in 1864 at the tragically young age of thirty-seven, and mystery surrounds his death to this day. His writing partner found him in a hotel room with a laceration to his neck. He had been down with a fever, so it is possible he fell, and the cut was accidental. Some theorize he tried to take his own life. Nothing definitive was ever established. But the people who come to the Camptown Race 5k and 10k are there to celebrate his life and lift their voices in song, along with their feet.

Details can be found on Facebook or through race sites such as runsignup.com.

Maggie Barnes has won several IRMA and Keystone Press awards. She lives in Waverly, New York.

HAMILTON-GIBSON PRODUCTIONS

Four Columns prizes, she was also a finalist in the international Beautiful Bizarre Art Prize, an annual prize competition that celebrates diversity and excellence in the representational visual arts.

Rick Pirozzolo, director of the Arnot Art Museum, says “One can always see Gina’s clever eye and precise hand in her painting. Her work is arresting, be it in the witty wink of Plot Twist [Four Columns prizewinner in 2023] or the arresting precision of Within Your Reach [winner of the 2016 Four Columns prize]. She’s a boss of creativity and talent.”

Looking Forward

Gina’s been offered more opportunities for exhibits and shows, but these need to wait until she retires from teaching, a bittersweet milestone currently five years away. “This is the last group of eighth graders I’ll follow through to graduation,” Gina says wistfully.

But she’s looking forward to painting fulltime and continuing to evolve as an artist. Which also means the evolution is an on-going process. With Emma’s graduation next year, she won’t be around as much to model for her mother. It’s possible, then, that Gina’s future art may move in an as-yet-unknown direction. For those captivated now by her paintings and the way they encourage the viewer pause and consider, the direction promises to be an unexpected and intriguing adventure.

“There’s something about her work, a very distinct style and flavor,” says Jesse. “All her paintings are a story, they have deep meaning, sometimes it’s subtle, sometimes it’s very apparent. There’s something more going on there, something symbolic. It was just beautiful to watch her when she discovered that. I could even see an extra sparkle in her eyes.”

Karey Solomon is the author of a poetry chapbook, Voices Like the Sound of Water, a book on frugal living (now out of print), and more than thirty-six needlework books. Her work has also appeared in several fiction and nonfiction anthologies.

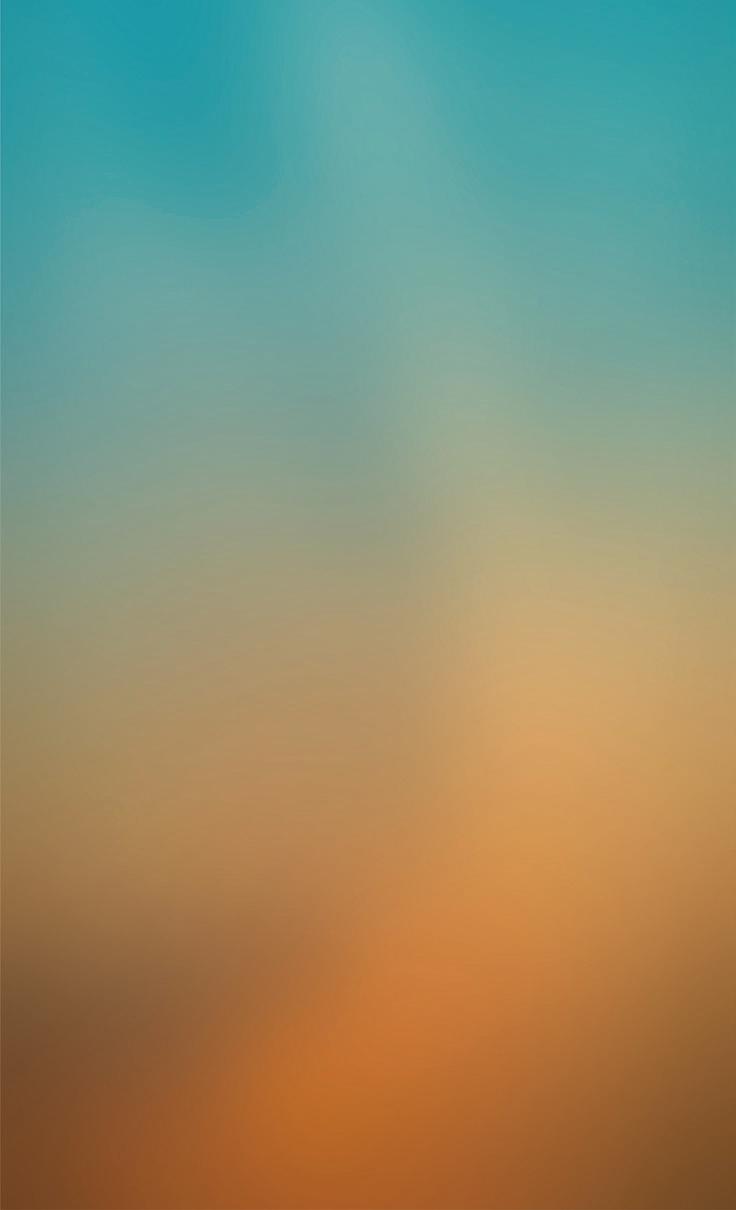

BACK OF THE MOUNTAIN

Fall Makes Its Entrance

By Linda Stager

At 6:51 p.m. the last of the summer light turns the field golden, the unmistakable hue that happens as summer begins to fade. The air tonight is cooler, quieter.

As a photographer, I know to expect the light to change. The tone of my photos will turn warmer, and my colors will, like the leaves around me, morph from summer greens to fall’s burnt oranges and sienna browns. To me, September is a prelude of the palette to come, the overture before autumn takes the stage. It’s a time of anticipation as well as a time to pause. This night reminds me of that.

75 Years CELEBRATING OF CARE

Join Guthrie on Thursday, September 11 for a historic community celebration honoring 75 years of care, compassion and community.

For 75 years, Troy Community Hospital has been more than just a place of medicine –it’s been a place of memories. As babies took their first breath and neighbors became family, generations have turned to care they can trust.

Guthrie is proud to serve the Troy community and to recognize the many years of service caregivers have provided, forming a legacy of healing and hope.

Learn more at www.Guthrie.org/75Years