Lighted Cornerslegacy vol. 42

Mount St. Mary’s University 16300 Old Emmitsburg Road Emmitsburg, MD 21727 301-447-6122 lightedcorners@msmary.edu msmary.edu/lightedcorners www.twitter.com/lightedcorners www.instagram.com/lightedcorners Volume 42 Spring 2023 Lighted Corners vol. 42 legacy

Policy Statement

Lighted Corners recruits its staff in September and opens for submissions in November. Students from across the university submit works that reflect diverse perspectives and themes. After removing the names of the contributors, the Lighted Corners staff reviews submissions. The editors make final selections and design the layout for the magazine by striving to create a union between word, image, and theme. All Mount students, regardless of major, are welcome to join the staff and submit their work for possible publication.

Production

Lighted Corners partners with Valley Graphic Service in Frederick, Maryland. 350 copies are printed by the company. The Spring 2023 issue is printed on 100# Gloss Cover and the inside is 70# Uncoated Opaque Text. The magazine body text is set in Baskerville, headers are set in Source Serif Variable, and title is set in Superclarendon. Lighted Corners is created using Adobe Creative Cloud. Editor-in-Chief Claire Doll and Design Editors Emma Edwards and Ashley Walczyk worked collaboratively on the layout of the magazine.

About

Lighted Corners is an annual literary and arts magazine that publishes poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, fine art, and photography created by students of Mount St. Mary’s University. Lighted Corners holds memberships with the Columbia Scholastic Press Association and Sigma Tau Delta.

The undergraduate student population of Mount St. Mary’s is 1,898.

The Lighted Corners logo was designed by Rachel Donohue, C’21. Rachel was a long-time Design Editor and served as Editor-inChief for Volume 40.

Awards

The Columbia Scholastic Press Association is an international student press association, founded in 1925, whose goal is to unite student journalists and faculty advisers at schools and colleges through educational conferences, idea exchanges, textbooks, critiques, and award programs.

Gold Medalist 2021, 2020, 2019, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2012, 2008

Silver Medalist 2018, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009

Gold Crown Award 2022

Silver Crown Award 2021, 2014

Gold Circle Awards

2022 to Rebekah Balick, Victoria Tyler, Megan Ulmer, 2021 to Rebekah Balick, Claire Doll, Rachel Donohue, Emmy Jansen, Kayla Jones

2020 to Tess Boegel, Gigi Gaston, Jazlyn Ibarra

2015 to Shannon Gilmore

The William Heath Award is an honor earned by the student who demonstrates outstanding achievement in creative writing. For more than twenty-five years, Dr. William Heath taught American literature and creative writing at Mount St. Mary’s University.

Claire Doll 2023

Betsy Busch 2022

Our contributors have earned recognition in Delta Epsilon Sigma’s undergraduate writing competition. DES is a national scholastic honor society established in 1939 for students of Catholic universities and colleges in the United States.

Claire Doll 2023 First Place in Short Fiction for “Of Summer and Salt Tears”

Claire Moberly 2023 Second Place in Poetry for “Snallygaster”

plain china: the Best Undergraduate Writing is an ever-growing anthology featuring young writers and artists on a national level. The following pieces from Volume 41 of Lighted Corners have been selected for plain china.

“The Dawn” by Tess Boegel

“Swimming Lessons” & “Sitting Under Starry Skies” by Claire Doll

“Los Pensamientos de la Llorana” by Alyssa Pierangeli

“Staring at my Bookshelf” by Angela Vodola

Editor-in-Chief

Design Editors

Fiction Editor

Assistant Fiction Editors

Claire Doll

Emma Edwards & Ashley Walczyk

Erin Daly

Hannah Perry & Devin Owen

Creative Nonfiction Editor

Assistant Creative Nonfiction Editor

Gabe Vilches

Jenna Scalia

Poetry Editors

Assistant Poetry Editor

Alyssa Pierangeli & Margaret Stine

Kayleen Dominguez

Art Editor

Assistant Art Editor

Anna Martinelli

Ana Purchiaroni

Public Relations Manager

Kayla Jones

Faculty Adviser

Staff

Dr. Tom Bligh

Therese Boegel, Amaya Bowman, McKayla Collins, Hailey Fulmer, Kaitlyn Gaskins, Rachel Hoerner, Cyre Hooper, Sarah King, Tess Koerner, Kayla Lijewski, Sarah Miller, Maureen Pham, Eileen Rosewater, Kelechi

Udom, Nina Wilkinson

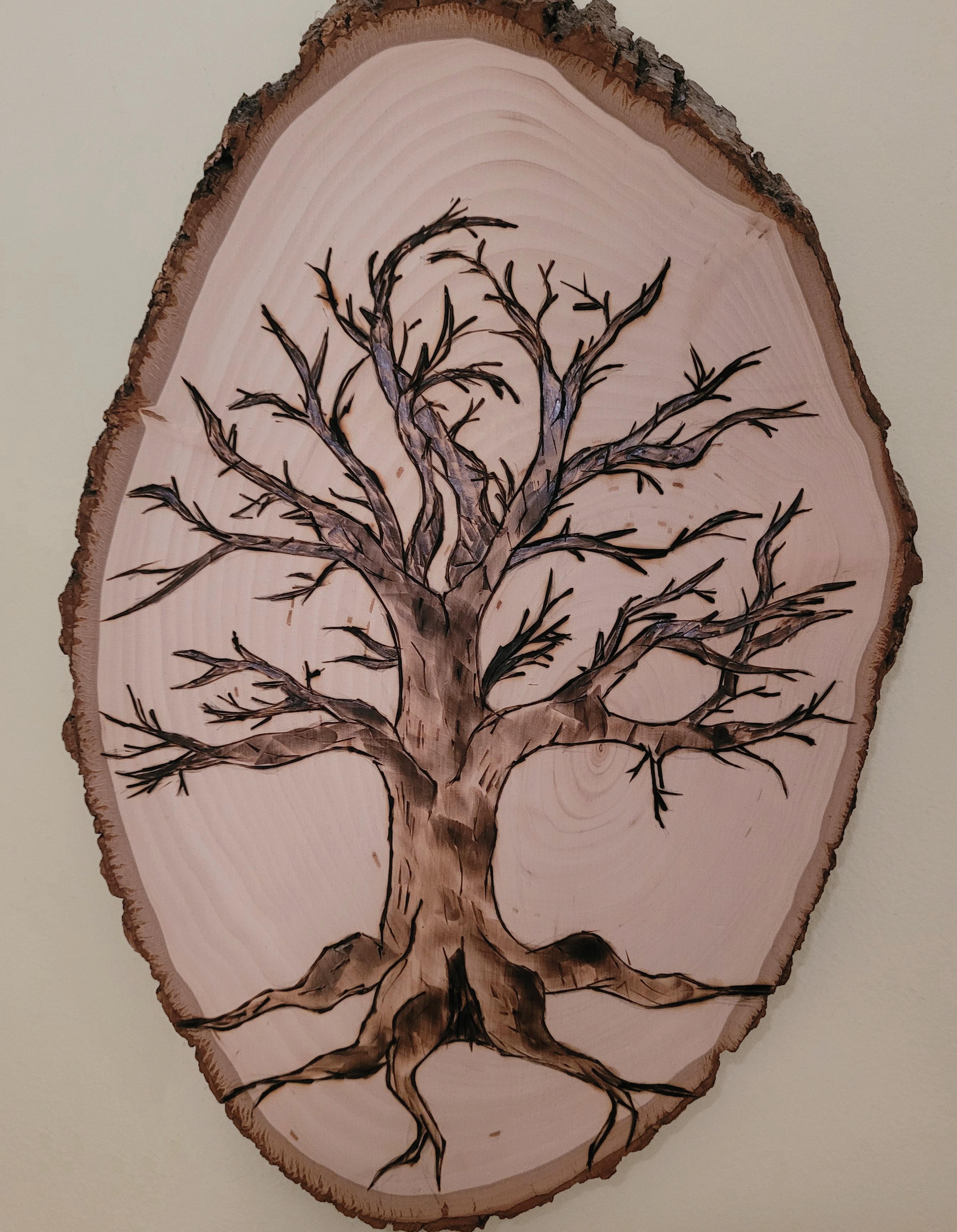

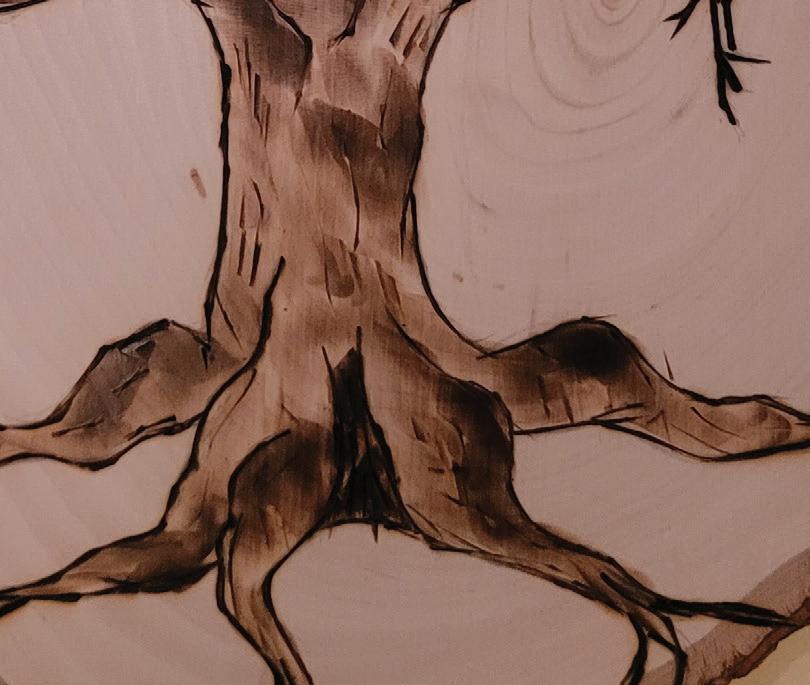

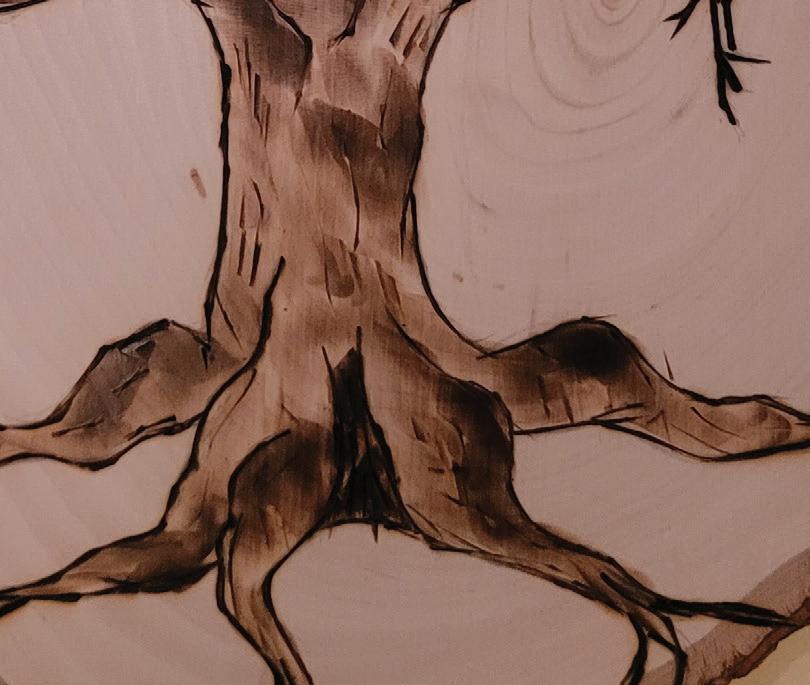

First Love by Frances Fisher

Pyrography on Wood

First Love by Frances Fisher

Pyrography on Wood

Contents Fiction 13 18 27 38 50 58 70 Creative Reporting the Weather Joanna Kreke Into the Darkness Kayla Lijewski What I Should Have Said Ashley Walczyk The City of Two Rivers Joanna Kreke Nonfiction Poetry Another Home Angela Vodola Eleven Fifty-Eight Joshua Aybar Pearl Claire Moberly There Came a Day Jenna Scalia Sisterhood Eleanor Fisher Old Soul Eleanor Fisher

Cloud Racing Eleanor Fisher Blueberry Pancakes Claire Doll The Broken Conversation Ashley Walczyk An Unopened Voicemail Erin Daly Zygomatic Arch Erin Daly The Cashier Tess Koerner The People We Meet Claire Doll First Love Frances Fisher Lovers Emma Edwards Tree of Life Frances Fisher Devious Little Ghosty Frances Fisher An Austrian Mountain View Frances Fisher Not Allowed Eden Blottenberger Growth Christopher Woodburn Madonna and Child Helen Hochschild Copy of Towaco and Mother Helen Hochschild 24 35 48 66 7 16-17 29 39 40-41 52-53 60-61 64 82-83 14 15 16 21 22 26

Visual Art

Cover Photo

“Descent” by Robert Prender

Early Summer

Insipid Inspiration

Margaret Stine

La

Ana Purchiaroni

Snallygaster

Claire Moberly

Wait and Wonder

Hannah Perry

As She Stands in the Mirror

Amaya Bowman

Festivities of a Full Moon

Jane Allman

Seasonal Impression

Sarah Johnson

A Villanelle for a Villain

Kayla Jones

A Modern Sonnet

Morgan Sturgill

Violins

Angela Vodola

Matty’s Poem

Eden Blottenberger

Wandering

Waterfront

Jaden

Dolores

Morning

Proverbs 3:56

Dolores Hans

Heritage

Dolores Hans Streets

Eden Blottenberger

Gata

Colton

Every Day

Dominguez

Loving Stillness Annabelle

Live

Kayleen

Spirit

Johnson Photography Citrus Sunset Jenna Scalia My Very Own Sakura Eileen Rosewater The Bay Janelle Ramroop Furry Friend Emma Edwards Nature’s Magician Eileen Rosewater Mark 10:27

Hans Life Robert Prender

Sarah

Dolores

Beauty

Colton

Room

Annabelle

Cabin

McNeal-Villafana

4:18-19

1 John

Hans

Rosary

Emma Edwards

Robert Prender

Drops of Heather

Jenna Scalia

Jeremiah 29:11

of Toledo

Emma Edwards

Prender

Canal Erin Daly Power

McNeal-Villafana City Center Emma Edwards Rockface Erin Daly 34 37 40 43 45 46 47 51 53 54 61 62 65 68 81 12 15 19 21 22-23 24-25 26 34 36 42-43 44 47 49 54-55 56-57 59 62-63 66-67 68-69 72-73 80 Author & Artist Statements 84-85

Formation Robert

Venice

Jaden

Editor’s Note

Art is a legacy.

The sound of a pencil kissing paper is music; the smell of fresh ink is captivating. Art leaves legacies so everlasting, so permanent, that we almost forget about them.

I fell in love with creative writing when I was young. Since then, I have left legacies all around me: stories made of construction paper with stick figure characters; poetry, written in cursive, on a café napkin; daily journal entries for my high school writing class (thank you, Ms. Thrailkill). When we write or draw or paint, we create legacies, little pieces of ourselves that last forever. Whether this art exists as a poem spoken to the moon, or as a delicate carving etched into a tree, or as a voicemail forever left unopened, it is, simply put, a legacy. An impact we’ve created that remains for the rest of time.

But a legacy can also be a moment, an experience that holds onto us for as long as our memory wills. Something that exists only in one course of time, one version of the universe. Legacies are the people we meet, the places we travel, the formations in mountains and the petals on cherry blossoms. Of course we are influenced by all the moments and experiences over the course of our lives, but what about the legacies we leave behind? The impacts we make on things and people and places all over the world? How come we always seem to forget these legacies?

I am inspired by our cover photo “Descent” by Robert Prender. At first glance, it appeared to me so simply: a lighted corner. I thought, how perfect, it goes with the magazine! We don’t quite see the sun, but we know it’s there. We see its legacy, dappled on the building of a narrow streetway in Spain. A legacy so simple, so beautifully comprehended. Now, this photo leaves a legacy on us.

I want to thank so many souls for leaving a legacy on me and this magazine: Dr. Bligh, our wonderful adviser, for nurturing Lighted Corners and allowing the students of Mount St. Mary’s to build their legacies; Robin and the Valley Graphic Service team for printing this journal with a heartfelt willingness to support our community; Dr. Mitra, Dean Zygmont, and Provost Creasman for bringing light to our magazine; Erin Tinney, for your knowledge and kindness in helping us; and of course, the amazing Lighted Corners staff, composed of creative students who have left pieces of their hearts and souls in this journal.

In this edition of Lighted Corners, we invite you to follow the legacies our authors and artists leave behind. Snapshots of the Alps, the story behind a family. Our most personal and human experiences, left in this journal, left as a legacy. The creators of these works will go on to do amazing things—becoming wandering spirits in this world—but for now, in spring of 2023, they leave a legacy in Lighted Corners.

Claire Doll

Claire Doll

Editor-in-Chief

Editor-in-Chief

Citrus Sunset by Jenna Scalia

Photography

Citrus Sunset by Jenna Scalia

Photography

Cloud Racing

Eleanor Fisher

When we were young, our favorite game was cloud racing. The five of us would meet up in the old field by the edge of the woods on bright, windy days and wait for massive clouds to roll overhead, bringing their shadows with them. As soon as a shadow touched the edge of the grass, we ran for the trees at the far side, trying to touch the old oak, or at least get as close as we could before the wind blew the cloud across the field and the shadow enveloped us. We spent many a day together that way, running back and forth, collapsing in breathless laughter in the grass at the base of the oak. We were inseparable— you and I, the siblings next door, and the kid down the road.

But we all had our own clouds to race and our own shadows to outrun. The four of us are grown up now, or at least people want us to be, and everyone is going or already gone. The kid down the road is into shady things now, with shady people, and the cops are often outside his house. Wherever he’s going, it’s nowhere good. The girl next door moved away after her brother died, and no one has heard from her.

You’re going soon, too, to bigger and better places, and I’m happy for you, I really am. I just wish we could sit in the grass under the old oak and pretend it’s not next to a parking lot now, pretend our lives are like they were before when we had smaller clouds to race.

13

Another Home Angela

Vodola

Caught in the current of growing old, driving to and from another home. I revel in the season I am leaving; fully living, but still grieving.

Tears come quickly but stop the same way, leaving the parking lot on the last day. Stuck at the red light that never ends, considering the thought of turning left.

Merging into cautious traffic on 15, with countless grocery truck Hail Marys, the cows that bring a smile to my face, and the zebra that still seems out of place.

The field next to where I got pulled over, the Burger King sign I thought was lunar, the house I wish I had grown up in, and the bridge that threatens flat tires again.

The parking lot where we talked for hours on end, the walking path where I still called you friend, the Valentine’s chocolates we kept in your car, and the grass we lay in to look at the stars.

Though, I recall this time last year, now, it is because I am happy, somehow, and some divine kindness has led me to this, so I’ll return in springtime to another home I miss.

14

Eleven Fifty-Eight

Should I turn in my homework late?

The night is young, yet I am tired. Is it wrong for my fatigue to abate with sweet slumber? That is what I have heard.

Try-hard “academics” often spout the lie, deriding the “weak” who require sleep. “One or two cannot hurt,” says I to me. Grades recover. Much like the herd of sheep

that has begun to leap into my dorm, filling my head with fog to block my thoughts. Likewise, my desire for my blanket’s warm embrace holds what thinking the fog allots.

Tonight, I give myself the gift of rest. This final factorial deserves my best.

15

Joshua Aybar

My Very Own Sakura by Eileen Rosewater | Photography

Claire Moberly Pearl

Gemstones are scattered across the skies, flung out to the farthest reaches of space. They are sparks in the darkness, burning bright, and constellations give them a shape.

We connect the dots with pins and strings and obsess over making lovers stay; holding onto our tangled chains and rings to keep each other from floating away.

There are no rings for Venus or Mars, but you know my love is forever sure. I can’t hang your form in the distant stars, but every moment with you I’ll treasure.

You’re worth more than all the gold in the world; this one is your oyster, precious pearl.

Lovers by Emma Edwards Watercolors on Watercolor Paper

Lovers by Emma Edwards Watercolors on Watercolor Paper

Blueberry Pancakes

Claire Doll

While driving, he stole a glance at his daughter. She was looking out the window, a slight breeze weaving through her brunette hair. Her eyes were blue: a heart-stopping, breathtaking blue, the kind that makes people tilt their heads and squint and say, what a beautiful blue your eyes are.

“Would you like to stop for ice cream?” he asked. He pictured it in his mind: the two of them, sitting at a picnic table, sharing a large cone with soft serve swirled on top.

Without meeting his stare, she shook her head.

“Alright,” he said. “That’s okay.”

So he kept driving until the road narrowed, until he could see water on both sides of his shoulders. To his left was the ocean, appearing as just a thin line of blue below the horizon. But still, it was there, sea foam sparkling under the sun. To the right, where Ella sat, was the sound side. Less exciting, but beautiful, with deep, shallowy waters and dancing cattails along its edges. Rolling the windows down slightly, Ryan breathed in the thick salt air.

He finally parked behind a diner. June, eleven-thirty, the sun beaming high in the sky, and he stepped out of the car and opened his daughter’s door. He offered to take her hand, and she declined.

“Where are we?” she asked, but

it sounded more like a sentence, a statement that broke out of her mouth in a dark monotony.

Ryan sighed. “Lunch,” he said.

They both walked inside, Ella first, and they were greeted by the loud and blaring smell of pancakes. Sugar swelling in the air, blueberries, strawberries, and chocolate dancing along with it.

“I thought you said this was lunch,” said Ella.

Ryan carefully ignored her and smiled at the hostess. “Two, please.”

“Right this way.”

A small booth, tucked in the corner of the diner, next to a window overlooking the coastal highway. A small vase of fake blue flowers placed in the corner. Two menus, sitting across from each other, waiting to be opened.

Ella thumbed through the pages of the menu, tucking a strand of hair behind her ear. She looked at her father with a blank stare, blue eyes like slivers of the summer sky. “I don’t know what I want.”

“That’s alright,” he told her, trying hard not to smile at the softness and confusion in his daughter’s voice. He wanted her to have that voice forever, to always be the little girl that could never make up her mind about what pancakes to get. Life, and its most simple problems.

Then a waitress approached them,

18

wearing her hair pinned half up, half down. Her eyes landed on Ryan, and as she smiled, age lines pressed into her skin. “Oh, my.”

Ryan grinned back and glanced at Ella, who was too distracted by the list of breakfast specials to notice the interaction. “Hello.”

“Ryan,” the waitress said, disbelief in her voice. “It’s been ages. How are you?”

He exhaled and smiled. “Hanging in there.”

“And is this—”

“Ella,” Ryan finished, gesturing towards his daughter, who was now looking up at the waitress with confusion etched on her face. “This is Ella.”

“Oh, my. You are beautiful, my dear,” she said, clamping a hand to her mouth. “And your eyes. Just like your mother’s.”

“How do you know my mother?” Ella blurted, her words running together; she sounded as though she had been attacked.

Ryan then placed his hand on Ella’s. “When your mother and I went here for our honeymoon,” he spoke slowly, “we would come here every day for lunch.”

The waitress nodded and lightly laughed. “I would serve them every day for lunch.” She turned back to face Ryan, her expression softening. “How are you holding up?”

Ryan sighed, letting out a breath of despair, and the silence surround-

ing him was enough for the waitress to press her lips together and nod. She looked at Ella, who stared blankly down at the table.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered. “I’ll be back with two waters.”

“Could we also have a large stack of blueberry pancakes?”

19

The Bay by Janelle Ramroop Photography

The waitress smiled knowingly, nodded, and walked away.

“Dad,” Ella said once she had left. “You went on your honeymoon here?” Disgust colored her voice.

Ryan grinned to himself. “We weren’t rich. This town had a beach, so we went.”

She raised her eyebrows, stunned. “And you had a good time?”

He nodded. “The best.” Looking out the window, at the bustling highway with rows and rows of traffic, at the seagulls soaring through the air, at the

Ryan smiled and drank in the sight of his daughter, thirteen, with wavy locks of hair and eyes blue like the surface of the ocean at sunrise, eyes like her mother—

Marie, your eyes are beautiful. —and pale, snowy skin. The image of a young girl, growing slowly, the way sunlight fills the world at dawn, the way the tide ebbs and flows like a heartbeat. She looked tired, perhaps from the three-hour car ride, but Ryan knew that exhaustion and grief had rooted themselves deep into her eyes, into

restaurants and hotels taking up every street corner, he continued. “It wasn’t always like this.”

And then there it was, her eyes sparkling—a desire, a longing for more. She tried to hide it with the creasing of her forehead, the tightness in her posture, but still, she spoke. Only four words, but enough to make her father’s heart leap. “What was it like?”

her body, enough to steal the brightness away from a girl. Still, she stared at her father with a sense of wonder, of longing. Ryan inhaled the diner air and was taken back to June, many years ago, to watching the tie-dye sunset from the balcony, to eating ice cream on picnic tables, to blueberry pancakes, with maple syrup drizzled on top.

20

The image of a young girl, growing slowly, the way sunlight fills the world at dawn...

There Came a Day

Jenna Scalia

There came a day when I stopped throwing wishes in wishing wells, when I stopped swinging as high and sliding down slides.

There came a day when I stopped believing in fairytales, when I stopped believing in happily ever after.

There came a day when I dressed up my dolls for the last time; when I held them up in their house once more before it was replaced with a bookshelf.

There came a day where I stopped looking for frogs to kiss, when I began to lose hope in finding a prince.

There came a day where I grew up; I put down the dolls, the hair clips, and the oversized shoes and slipped on a fitting pair.

I picked up a pen and began to write. I chose a song and began to sing. I found my voice and began to speak.

But the other day, I threw a wish in a well; I swung high on a swing and slid down a slide. I almost believed in fairytales.

There will come a day again.

Furry Friend

Emma Edwards Photography

Sisterhood Eleanor Fisher

All my conversations with my sister are in the car now, with a boy band soundtrack and snacks waiting at the end. She checks the map and passes my water, and somehow, it’s easier to ask about her mental health or her boyfriend or her allergy struggles when I’m driving. We ramble and navigate and trade advice as the miles roll by, and it’s our little world in the car.

All my visits with my sister involve cooking now, with promises of cookies and brownies and turnovers at the end. She comes over to use my kitchen, and I braid her hair while the food bakes.

I’m bad at French braids and pie dough, but she doesn’t mind. We talk about our week and share our delicious triumph, and I make her promise to text when she gets home.

All my favorite moments with my sister have changed now, with the same thread running through from beginning to end. We dye each other’s hair where once we played with mom’s makeup, and we play arcade games instead of dolls. We go to college together as we once went to kindergarten, and she helps me choose my wedding gown like we played dress up. She’s still my first friend, beyond doubt and change.

22

Nature’s Magician by Eileen Rosewater Photography

23

Reporting the Weather

Joanna Kreke

I don’t know why I remember standing in front of my house, umbrella in hand as I reported what was happening. The rain started falling the night before. As I opened my eyes the next morning, I still heard the tick-tick-tick hitting my window. It wasn’t a downpour—it was slow and steady and just as damaging. I begged my dad to take me to see the creek in front of our house, and after a few minutes of continuous, “please, please, pretty please,” he finally caved.

The creek had overfilled its banks and was leisurely swirling through the soccer field on the other side. Massive puddles blanketed the park. I stomped through them, kicking muddy water in the air and twirling my umbrella. It was one of the few times in my life I had rainboots that fit and kept my socks dry. After a few minutes, my dad said, “Alright, let's go.” But I wasn’t done being outside. We crossed the street. He went inside. I didn’t.

The Weather Channel was my favorite channel. I was fascinated with the awesome power that weather held over us. I had seen Weather Channel people clad in their blue “Weather Channel” jackets getting pelted by rain, hail, and wind, as they reported what was happening. I wanted to be just like them. I held my umbrella in one hand and held a microphone in my other. In my head, I heard a voice say, “Now, let’s turn to

Joanna who’s over in Frederick, Maryland. What’s happening over there, Joanna?”

I waited a moment, just like they do on TV. “It’s a lot of rain, Jim.” Pause for the obligatory laughter. “It has been raining here for nearly 36 hours, and there is no sign of letting up.” I pretended the camera shifted to the flooded creek. “The creek has overfilled its

banks, but it doesn’t look like any houses are majorly affected.” I had no idea what that meant, but it was something I heard a bit on the Weather Channel. I crossed the street and began reporting on how high it was.

“Joanna Claire! Get back here right now!” It startled me, and I jogged back to my front yard. It wasn’t the first time I did it, and it wouldn’t be the last.

Mark 10:27 by Dolores Hans Photography

Old Soul

Eleanor Fisher

My love was born in the wrong century. His car is older than me, but he drives it with pride, a new cassette for every ride. Museums are the places that he thrives.

He belongs to the era of steam trains, with shrill whistles, massive machinery, and blaring horns. He loves to explain history, reciting from memory.

He could tell you the lives of stars long gone more easily than what he did today. At work he listens to twenties jazz songs, and he sends love letters when I’m away.

Although my love is a man out of time, I am blessed that he joins his life to mine.

26

Life by Robert Prender Photography

The Broken Conversation

Ashley Walczyk

Coal mining was not an easy job, but one an immigrant could easily get. There were risks with mining the coal lying within Mount Washington—also known as “Coal Hill.” Miners were never guaranteed a tomorrow. They prayed that their day’s work could end at home with a nice dinner and their families.

One miner in particular was hoping to return home soon. His round hat— which had his lantern attached to it— fell into his eyes from the sweat on his forehead. He pushed it up, wiping away the residue on his denim trousers. His cotton-white shirt was stained with the dirt and stench that came from being down in the mines. His boots were dirtied with soot and mud, and sometimes, human blood.

Ludwik remembers the times when mining was easy, and when mining was difficult: from the dangerous conditions to the caves collapsing, he remembered it all. The pocket watch he carried from his time in the Polish military ticked and tocked. He had an hour left down in the mines, which settled his nerves only slightly. No one ever knew what happened in the mines in five minutes’ time. He sighed, picked up the pickaxe he spent his wages on, and continued back to work in the mine.

Ludwik grew up in a small village. He rarely talked about his life back in

Poland and never made any attempt to go back after 1934. His life was here in America. Communication with his mother and father happened in the 20s and 30s, but when the new war started, the letters disappeared. He wondered how his parents took the news of his brother’s passing: a young boy, his brother, getting shot by a German soldier at the beginning of the Great War.

The miners slowly began to pack up their pails and tools. Ludwik kept on mining, pounding at the harsh rock underneath his feet. One wrong clang, and the manmade cave could come crashing down on them, trapping them in their own tomb. He knew the consequences, but he kept on mining. He had a job to sustain. President Roosevelt made it clear that this war will need fueling; and because of the Depression, many immigrant workers had to sacrifice their jobs to make room for those who mattered. And yet, the Pole kept on mining.

Although the job was dangerous, he wanted to go home to his family and observe them, but he felt embarrassed for not understanding their language. A much more intimidating task to him, but he would never admit that. All around him, the miners chatted—English and Irish accents filled the caves—but it was hard to listen to while the pickaxe hit the hardened earth.

With a day’s work ending, he packed

27

up the lunch pail his wife had made him, gathered his tools, and trudged home, letting fatigue settle into his muscles. He worked long hours, too long, he always thought. His day started in the morning and ended late at night. Ludwik was content with life; he lived with his wife, his children, and within a town small enough that he remembered where to go and what street to go down. They didn’t have much, but it was enough.

He followed along the main stream of water, Chartiers Creek, which lied on the southeast side, next to the main

kids nor his wife.

Along with the language barrier, Ludwik had to make sure he was making enough to support his growing family. The first child to be born was a baby girl named Jean in 1924. Next came Vesha, then Patricia, who wanted everyone to call her Patty, and finally, a boy named Louis. There were six mouths to feed, and unfortunately, on a miner’s pay: three-hundred-twenty-five dollars annually, a quarter an hour.

His door, which was made of chestnut wood, opened as he turned the brass

road. The little town of Canonsburg was known as a coal-mining town, providing recourses for the war on the other side of the world. The hours became longer, but jobs became scarcer. This place seemed to use manpower instead of machine-power. Ludwik continued up the street to the upside of town.

He passed the school and thought of his children, learning things that he had no access to as a child. They read literature of the grade, but also did math and arithmetic. Ludwik, despite not knowing American history himself, was proud of his children for learning more about the country they were natural-born citizens in. He never taught them Polish.

The house spoke in English; the children and their mother were fluent in the language. His journey from Poland to America was not questioned by his

handle. His wife, Katherine, was in the kitchen when he entered the small house, preparing a chicken from the local farm, de-plucking and de-clucking it. He kissed her cheek before putting the pail on the unused counter.

Katherine didn’t remember what Poland was like. She came with her family as a baby, cradled against her mother’s chest as they left the immigration island. Her native tongue had not yet developed, but she understood what her parents whispered in their late-night conversations when she and her siblings were supposed to be asleep. How else could she have cursed out her husband several times in his native tongue?

Katherine was the wife of a Polish immigrant, although that wasn’t uncommon at the time. They had met in the same small town they currently resided

28

They didn’t have much, but it was enough...

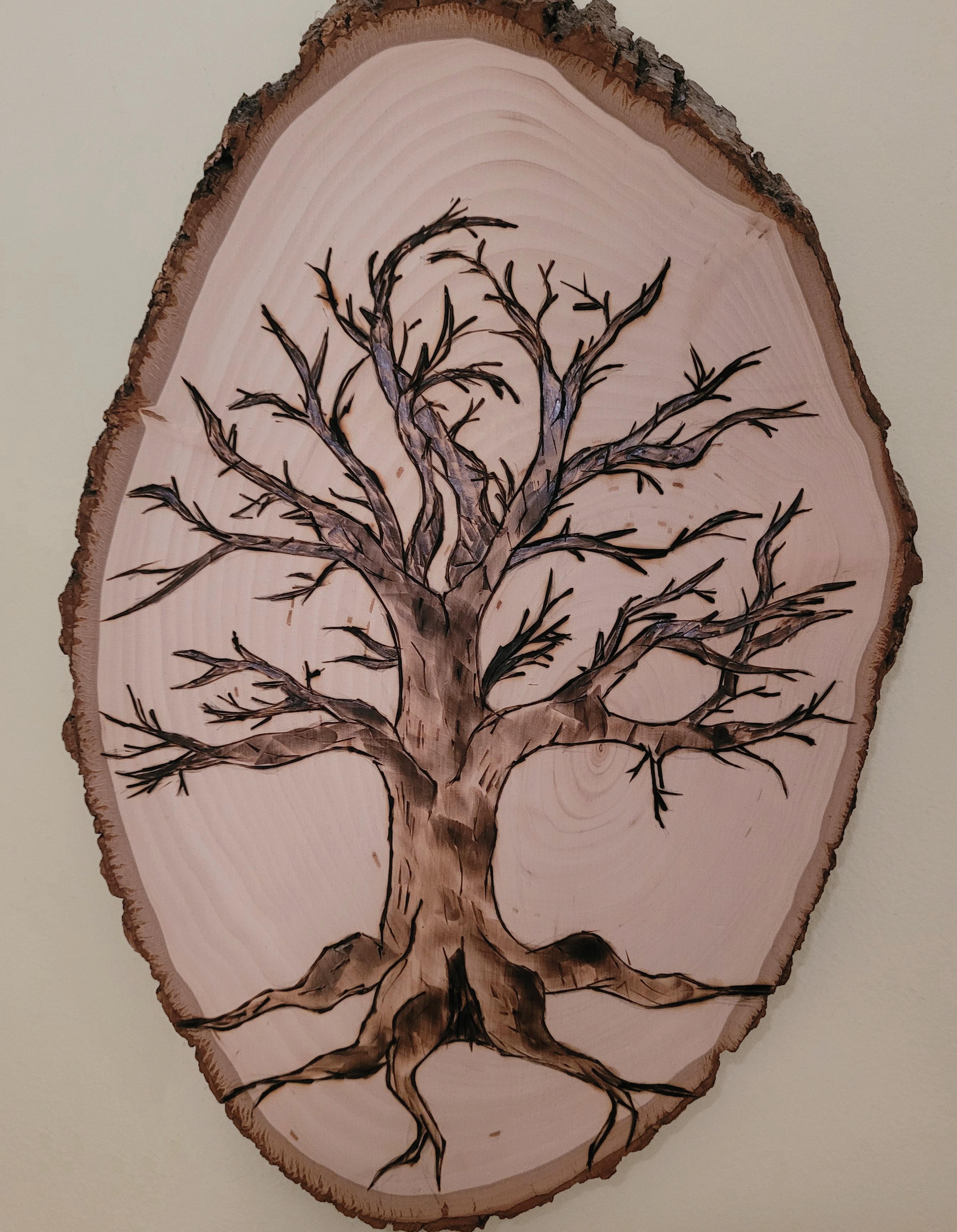

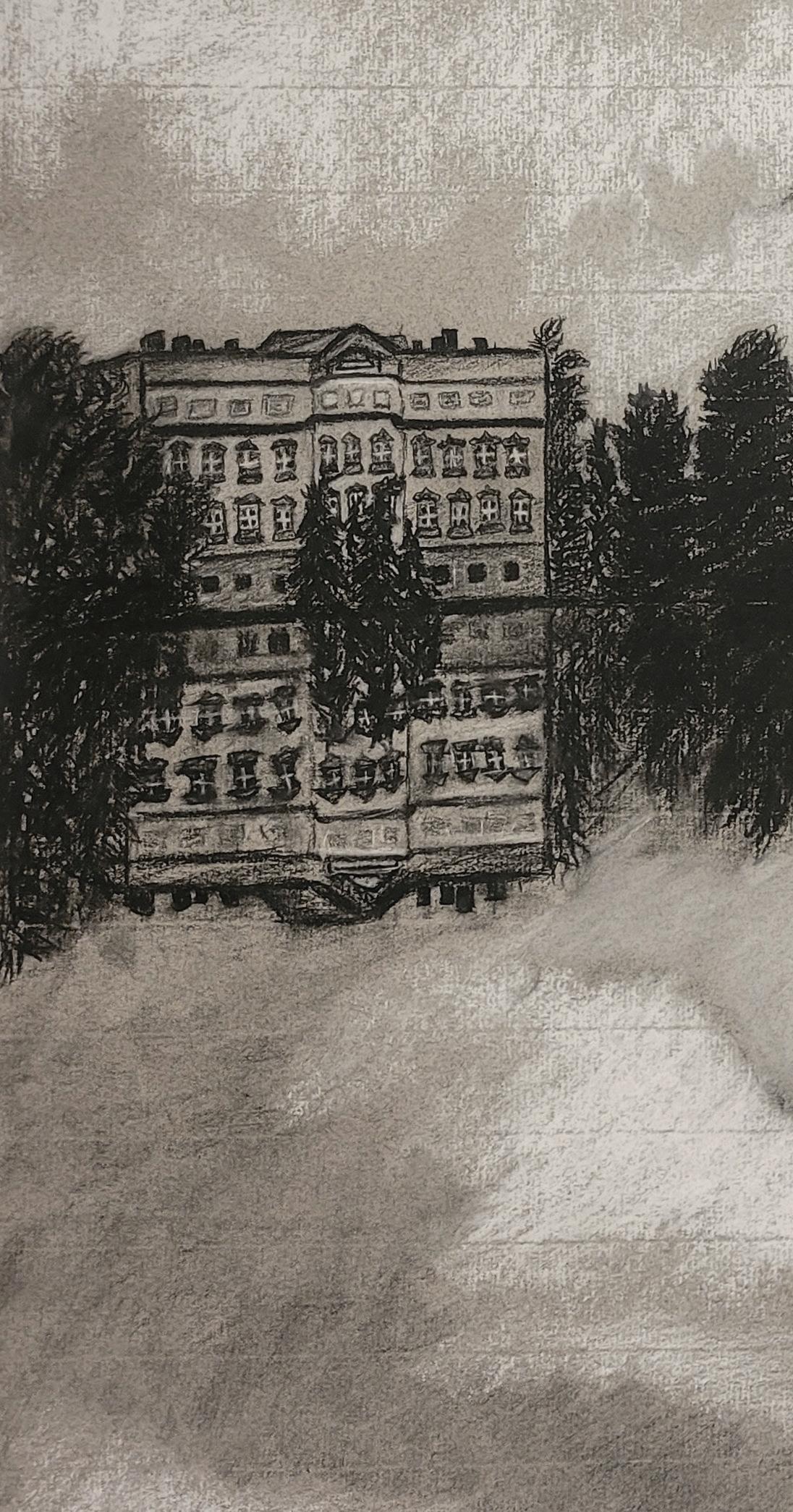

Tree of Life by Frances Fisher

Pyrography on Wood

Tree of Life by Frances Fisher

Pyrography on Wood

in, finding each other on the street. She understood Polish because of her parents, and he kept quiet, mortified at the intimidating surroundings. She helped him find his way up the streets and kept him in for dinner afterward.

Her parents were excited when they first met, pushing for the two to get married before he went back to Poland. They went on a couple of dates. The first one was a simple dinner date, just for the two of them. He spoke in Polish with her, and she understood for the most part. Eventually, the dates turned more romantic and loving, the two gradually growing closer due to their shared culture. But Katherine hoped he would speak in English eventually.

When they married, they promised each other to live the American Dream, promised that their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren could have the same opportunities as all the other children of American descent. He never went back to Poland after his third daughter was born.

Footsteps were heard down the hall. The children were running and shoving, shouting at each other before entering the room. Ludwik smiled and greeted them each with a kiss on the head. Katherine placed the now-roasted chicken in the center of the dining room table, on top of her nicer tablecloths. The others she kept away for when she wanted to roll out the dough for homemade noodles, so as to not ruin the wooden tabletop.

“Children,” Katherine called into the living room, “…father is home… time… dinner.”

One by one, they raced each other into the dining room and to their designated seats. There was a competitive streak within all of them, made clear by the shouts of “winner” and “loser” following the impromptu race. Ludwik did not say anything but allowed himself to relax to the chorus of his children. His wife chastised them for being loud, but he didn’t understand. Besides, his family’s bantering was better than the clashing of steel against rock.

They had their prayer, followed by a small silence before Louis, the youngest, spoke up. “got… today… worked hard…” These were the only words that Ludwik picked up.

“…you… well… good… hear…” Katherine responded.

“Well… got… on my…,” Patty spoke.

“And I got—”

“…and I got—”

“I have—”

30

“I did—”

Their voices grew louder and louder with each accomplishment they acknowledged. Katherine scolded them on table etiquette while Ludwik sat back in his chair. He did not understand what she wanted from them, but he was too embarrassed ask. He shifted in his chair.

He tried learning English; his wife was his first teacher. It proved to be much more difficult to set aside time to practice and study with the mining and the children. Eventually, the schedule was unknown between the two, and sharing five minutes with each other was never guaranteed. He wanted to understand the smallest bit of English to be able to communicate to his wife and children the love he had for them.

When dinner finished, Louis and Patty helped with the dishes. Ludwik still sat in the dining room, watching Vesha and Jean complete their homework. The chores today were of the lighter load, which gave them time to work on whatever they needed to, in preparation for tomorrow’s eight-hour day at school. Ludwik observed each pencil stroke, each curve and line, and each dot. The characters on the paper seemed familiar, but the order was foreign.

Katherine continued on in the kitchen, putting away what little leftovers they had into their small icebox. Ludwik wanted to get her a bigger one since the storage of food was always a struggle. He hoped his next pay was slightly better than the one before, but it never was. He watched his two younger chil-

dren bound their way into the living room, pulling out checkers to play. Ludwik taught them to play, grunting and smiling to tell the kids their next move. He watched Katherine in the kitchen, washing the dishes in the sink and putting them on the rack to dry. His heart swelled.

When it was time for the young children to go to bed, Katherine pulled them from the board, guiding them to their rooms. They dressed and got ready for bed, then were tucked in by their mother before closing their eyes and awaiting sleep. When she returned, she reminded the older two about how late it was getting. They groaned before quickly finishing up their schoolwork and heading off to bed. Ludwik was alone with his wife for the first time since the early morning hours of that day.

“Hov vas day?” Ludwik asked, Polish accent thick in his broken English.

“…think…would help… you spoke… children… English,” Katherine said, picking up her crocheting needles,

31 The Broken Conversation

resuming her hat for Vesha.

Ludwik frowned. He understood some bits, and knew she was correct in saying it “would help,” but the language was so complicated. Katherine shrugged, resuming her crocheting. They sat in silence for what seemed to be a long time. Sighing, Ludwik started speaking in Polish.

Katherine frowned, lifting her head from the half-made hat towards her immigrant husband. “What… you say?”

“I say no-ting,” he muttered, remembering the word his son used when talking to his older sisters. It was a constant use for Louis.

“…not ‘nothing’. I know… you… upset… you speak… that language… tell me… you said,” she scolded

“I am mad!” he bellowed, standing up from the chair. Katherine sat, not flinching at the sudden outburst. “I no speak to children. I know little vords. I no help!”

“Ludwik,” Katherine said, putting the hat on the table, “to be… to talk… them, you… practice.”

He swore at her in Polish, throwing his hands up in the air. “All I do i’ ‘it and I liten. I no help!”

Katherine, calmly, stood to meet her husband at eye-level. His hands—the same hands that articulated the words he spoke to her—rested at his side now.

“…you remember… promise?” she asked him. “…you remember… to give children… the life…never had?”

He nodded, sitting back down in his chair. His hands rested on his forehead,

covering his eyes, as his elbows rested on the table. Katherine scolded her children about the mannerisms, but she never did with him. “Ludwik,” she said, walking over to rest her hands on his rough shoulders, trying to rub the pain away.

“It i’ hard,” he exclaimed. “I no ‘peak Englich. I know little, but no much.”

“…kids help you. Children… be able to… help… parents…” she said, rubbing his shoulders. “…for you…time is now.”

He sighed, pushing his head to rest against his wife’s stomach. Maybe it was time for him to rely on his children. He wasn’t young, only in his fifties, but if God wanted him to rely on his children for help, then he must accept. “Okay.” ...

Time had passed since the broken conversation. Ludwik woke up in the morning, kissed his wife on the cheek, and got up to get ready for his mining job. Katherine awoke not too long after and starts to prepare his lunch and breakfast for the children. Ludwik came into the kitchen, greeted his wife with a “good mo’ning,” before grabbing his lunch and telling her to kiss the children goodbye for him.

He worked long hours in the mine, but with a renewed vigor. He wasted no time packing his belongings when seven o’clock rolled around, hurrying to get home to his awaiting family. Dinner was a success, the children conversing over pasta—handmade egg noodles of their

32

mother’s—and their father chiming in to ask about the meaning of a word, or with simple praise for his children’s success.

The night included chores, schoolwork due for the children the next day, and a type of family bonding during English practice with his children. The children asked for help with mathematics, which neither parent could help with, but them asking helped Ludwik to understand their needs a bit more.

Homework concluded quicker than

census. He wrote out his name, his wife’s and children’s names, occupation, citizenship, and monthly salary. The census was only a few lines long to fill out, but how proud he was to understand the language, for the most part.

“Your name goes here,” his eldest said.

“Lud-vik,” he responded.

“Yes, and we practiced this… write out your name on this… paper… put in on this paper after.”

And Ludwik did that, until he got

Time had passed since the broken conversation...

usual. With the English lessons at night, the children took turns, rotating every other night or two during the week. Tonight was an exception, for they finished everything early. Ludwik, although not the best, did learn more words in English, like garage key and shit. They came out sounding like “grats-key,” and “chit,” but it was progress.

He also learned to write in English as well, being able to write the 1950

frustrated, throwing his pen down and scoffing. His daughter, with her cursive handwriting, went on to finish the census, asking him in English what she should put down. Besides, it wasn’t completely illegal to have children fill out the census for immigrants. Old habits died hard, especially with a tongue that was not native to the land.

33 The Broken Conversation

Early Summer

Eden Blottenberger

I would chug the ink in my comics to feel the emotion I did— like the best high you’ve ever gotten, drunk on the past, vomiting up the future.

Have you ever sat at a pond in the dark? Stars tracing the water in waves, you breathe the mist off the lake and think— that hit from the past would set in differently now, wouldn’t it?

It’s easy to appreciate being alive when you’re dead, a love song written to avoid getting deeper into the black water. With each set growing colder, the ink stains your hands. Now I’m six feet deep in before, choking on words from yesterday.

What if you could roll your history into a blunt? Pack the past into a pill and snort it? If you took an X-ray of my head, there’d be a mouthful of ink and a gallon of pond water.

Waterfront Beauty by Annabelle Colton Photography

Into the Darkness

Kayla Lijewski

At ten years old, I find myself lying in a hospital bed, awaiting the unknown. It’s surgery day. Harsh light blinds my tired eyes as I’m wheeled into a room buzzing with energy; machines beep, people rush around, and the familiar scent of sterility overwhelms my senses. My mom comes into view with a warm smile and soft eyes, trying to hide her nerves the best she can. She looks down at me, squeezing my hand and comforting me before I’m put under anesthesia for twelve hours.

“It’ll be okay,” she says. “You’re just going to sleep for a while, and then I’ll be right here when you wake up.”

My mom has always been a light in my life, but soon I’ll be wheeled away from her into an overwhelming darkness. It’s okay though—I’m used to it.

Masked nurses and doctors weave in and out of my vision, causing nerves to jolt through my body. Where do I look? How much longer will this take? What is everyone doing? They start talking to me, staring down with everything hidden but their compassionate eyes. They’re trying to make me smile and laugh. I don’t want to, though, and I think they know that. I can’t seem to think of anything to calm my nerves, but it’s okay—I’m used to it.

With my mom by my side, I feel the tugs against my arm that tell me it’s almost time for surgery, and my life is going to change forever. The doctor pulls at the tube connected to my IV, getting ready to give me the anesthetic. I see the large syringe filled with a crystal-clear liquid being connected, followed by the familiar salty taste as the saline enters my veins and consumes my senses. My heart beats fast as I think about what’s to come. I’m anxious and oblivious to all that might follow this moment, and the truth is: everything is not okay. I may be used to it, but I’m just a kid.

The doctor unhooks the saline and replaces it with a syringe filled with milky-white liquid. As it connects to my tube, I stare at the ceiling, seeing my mom in my field of vision. The doctors start telling me jokes, trying to lighten the mood, but their voices start to muffle. My vision goes hazy, and my senses start slipping away. Everything that was clear a second ago is now fuzzy and obscure. Until it isn’t. Until everything goes completely black, and I’m entering a state of unconsciousness with no recollection of getting there. Until I wake up in another small room, cast in a soft glowing light, mind foggy from twelve hours of sleep, and everything I was used to in the past six years doesn’t exist anymore.

35

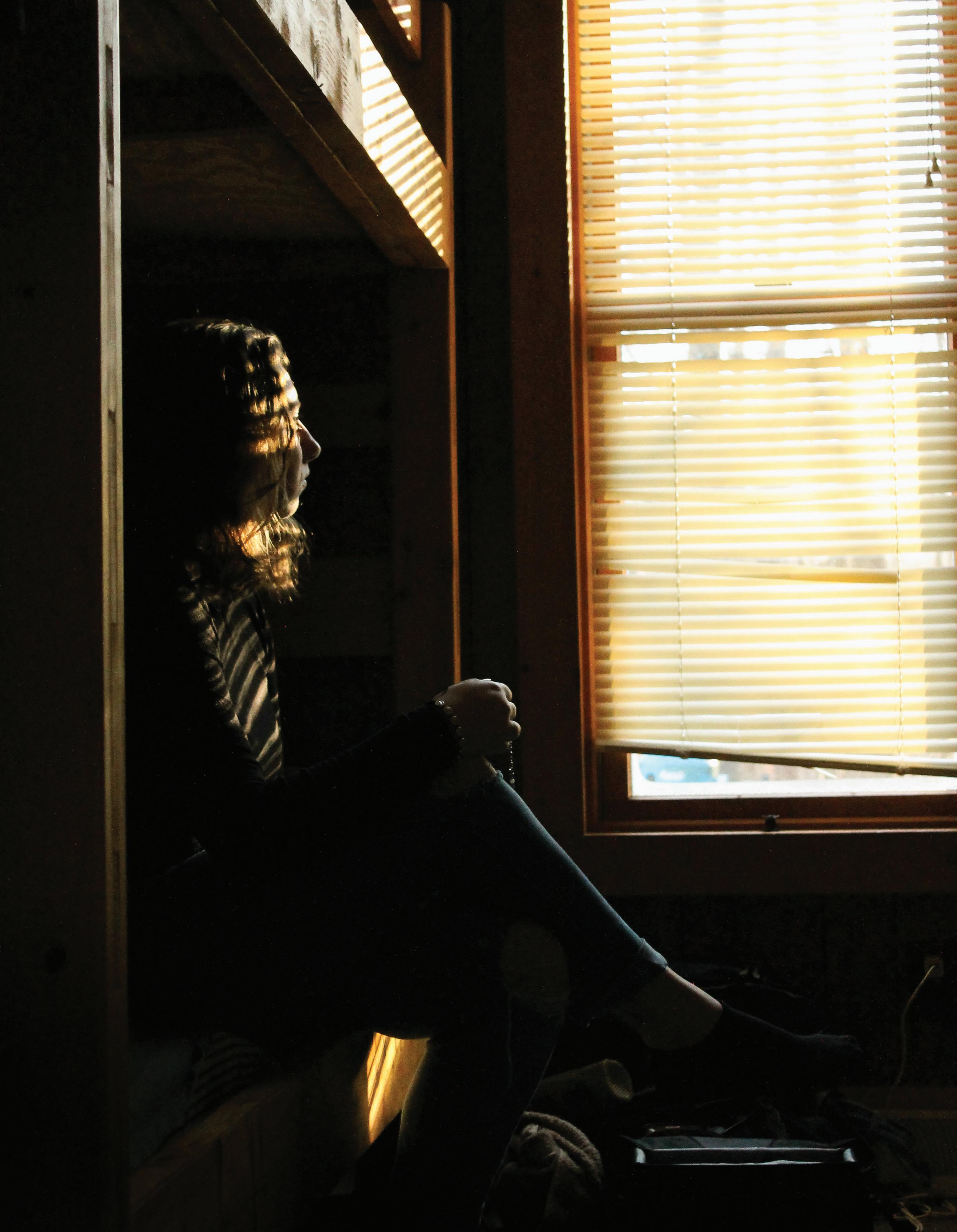

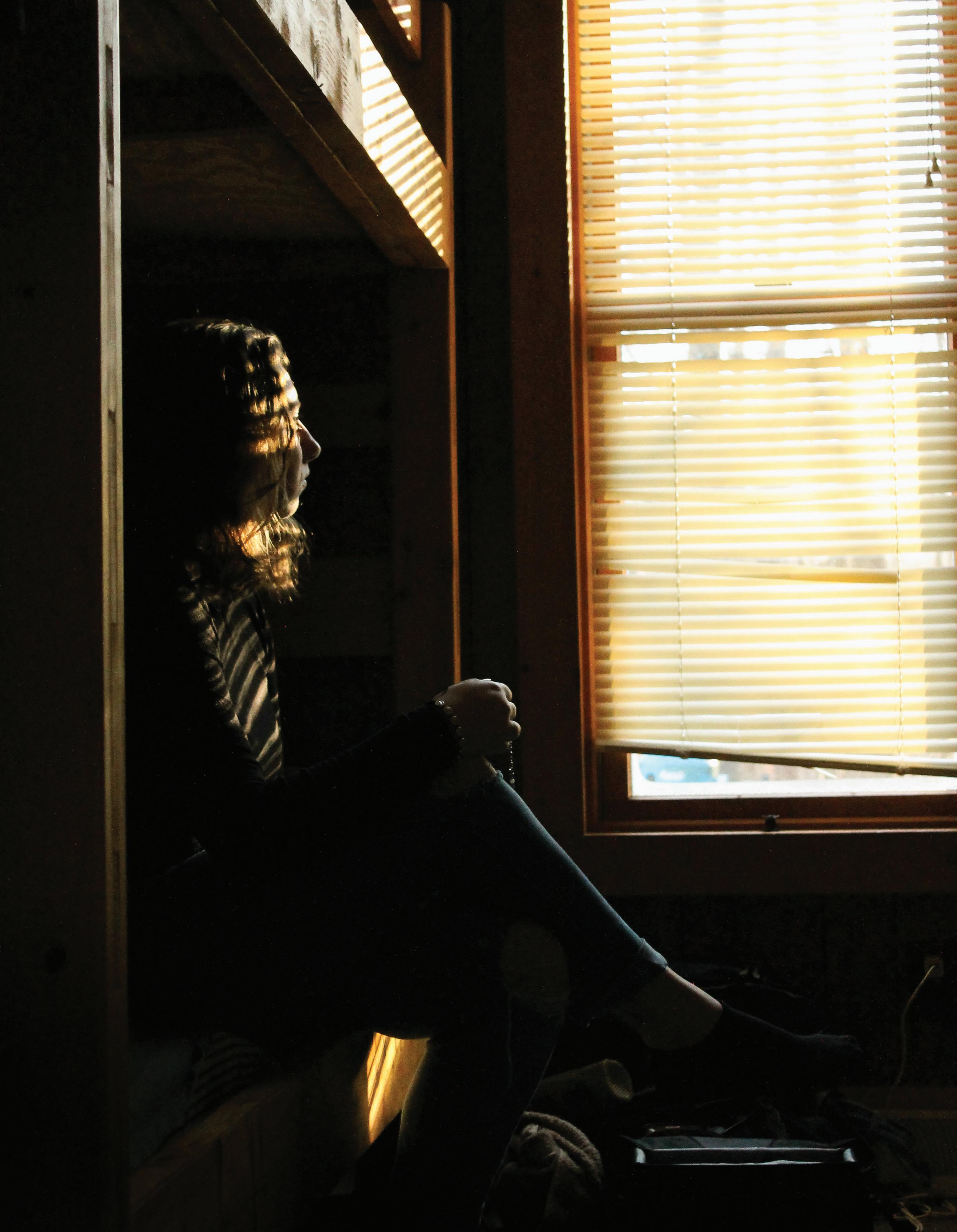

Cabin Room by Jaden McNeal-Villafana Photography

Cabin Room by Jaden McNeal-Villafana Photography

Insipid Inspiration Margaret Stine

A blank page, begging to be filled with words, remains empty. A mind empty of thoughts could create a world teeming with life. A room decorated with furniture remains devoid of sound.

Why does the pen not write? Why does the imagination fail? Why does the author still wait for inspiration?

The ticking of the clock breaks the silence. The pen begins to write. Inspiration flows, cascading like a waterfall, covering every surface it seeks.

The author, like an artist to a masterpiece, is satisfied.

37

A room decorated with furniture remains devoid of sound...

An Unopened Voicemail

I have always been afraid of forever. Terrified, actually. I remember the first time the magnitude of the word really struck me. I was sitting in my thirdgrade religion class. Ms. Larson, my teacher, was extremely religious. Anytime someone said, “Oh my God” they had to stand in front of the class and say the Act of Contrition. And when we heard a siren outside, she stopped the lesson and we all had to say three Hail Mary’s for whoever was in trouble. And she had this fiancé who she was engaged to for five years because she was still considering being a nun and…

Sorry. This isn’t important. What I want to say is one day we were talking about death, and she said that it was actually a good thing because it meant we would get to live forever with God. That our life on Earth was only temporary, and it was our life in

Heaven that was everlasting. But we had to be careful because if we were sinners, our forever would be spent suffering in Hell. After hearing that I obsessed over it for weeks, months, years. I was so convinced I was a terrible person because my best friend and I had been really awful to a girl in our class the year before and she changed schools and I felt so guilty. I knew that forever for me meant a horrible fiery punishment. I’m sorry. I know this doesn’t really make sense I just…

I just wanted to explain why when you got down on one knee asking, then two knees begging, praying for me to be with you forever, I had to say no. You can’t really have forever in this life, there’s only now and the next life. And forever feels like being shackled and in pain and I won’t, I can’t promise… Anyway, I’m sorry.

38

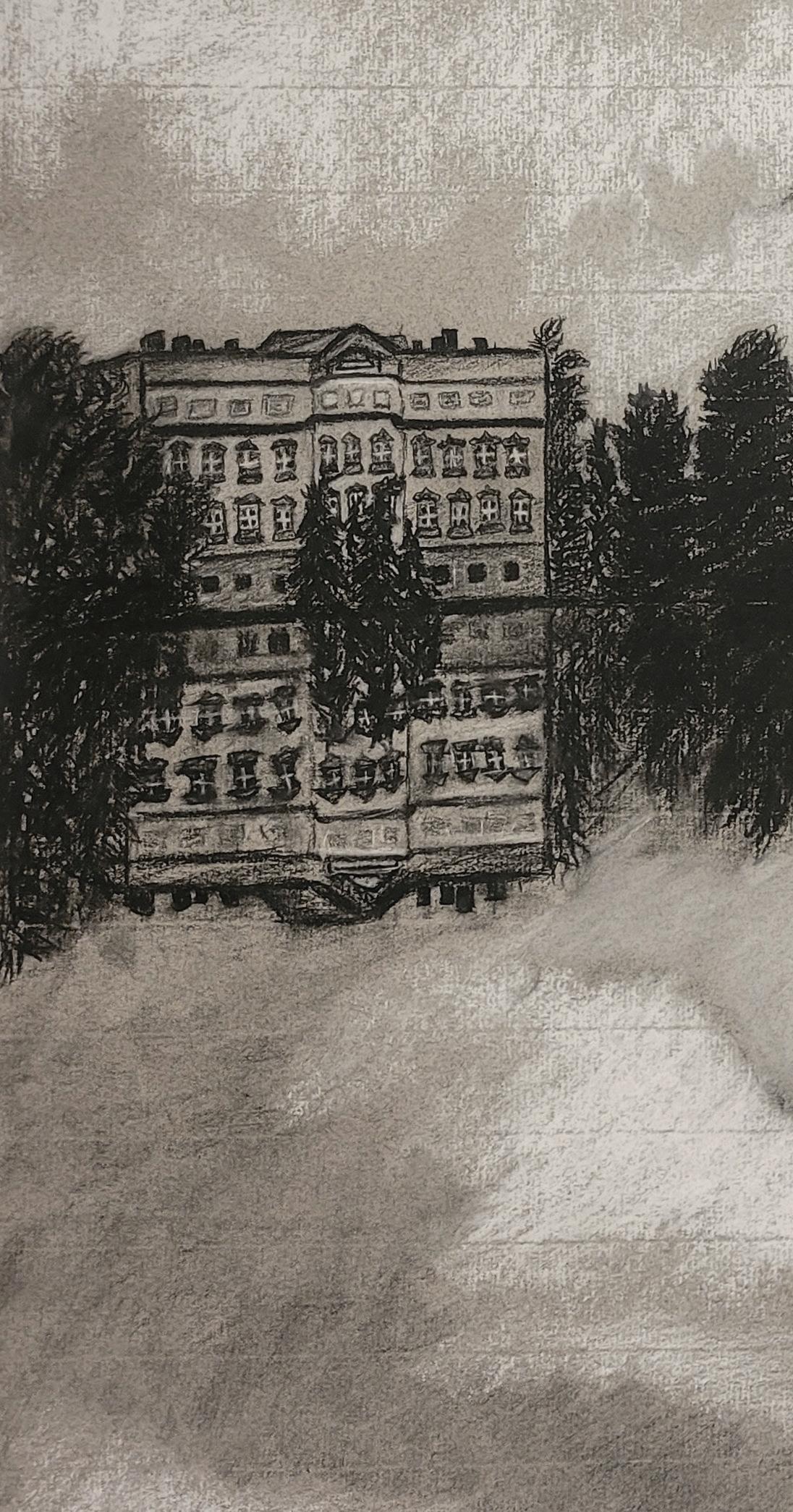

Devious Little Ghosty by Frances Fisher

Reverse Charcoal on Matte Board

Devious Little Ghosty by Frances Fisher

Reverse Charcoal on Matte Board

La Gata Ana

Purchiaroni

Nobody knows the story of La Gata. It’s not a common folktale or urban myth. As a child mi mama would whisper the tale under bundled up sheets and soft glows of lamplight.

Where is my chupon?

The one that I always sucked on to soothe me.

The one that caused the gap between my teeth.

La Gata snatched it.

The black cat with green eyes that stalks under cars and prowls at night. She snatched your chupon without a trace. You probably dropped it during your terrible twos tantrum.

That’s when she snatched it with one clawed paw.

Her nail like a hawk’s talon hooked to it with one swift swoop.

She had an accomplice, El Raton. With his big ears and long tail. His nose could sniff out little girls who tried to look for it. He ate it, gobb led it up, and left no crumbs. Don’t check under the car; you won’t find it.

40

La Gata y El Raton have done away with it. Now you have no chupon. You will just have to manage. La Gata took it. El Raton ate it. And they are onto the next little girl with a gap, between her teeth and a fear of the dark.

41

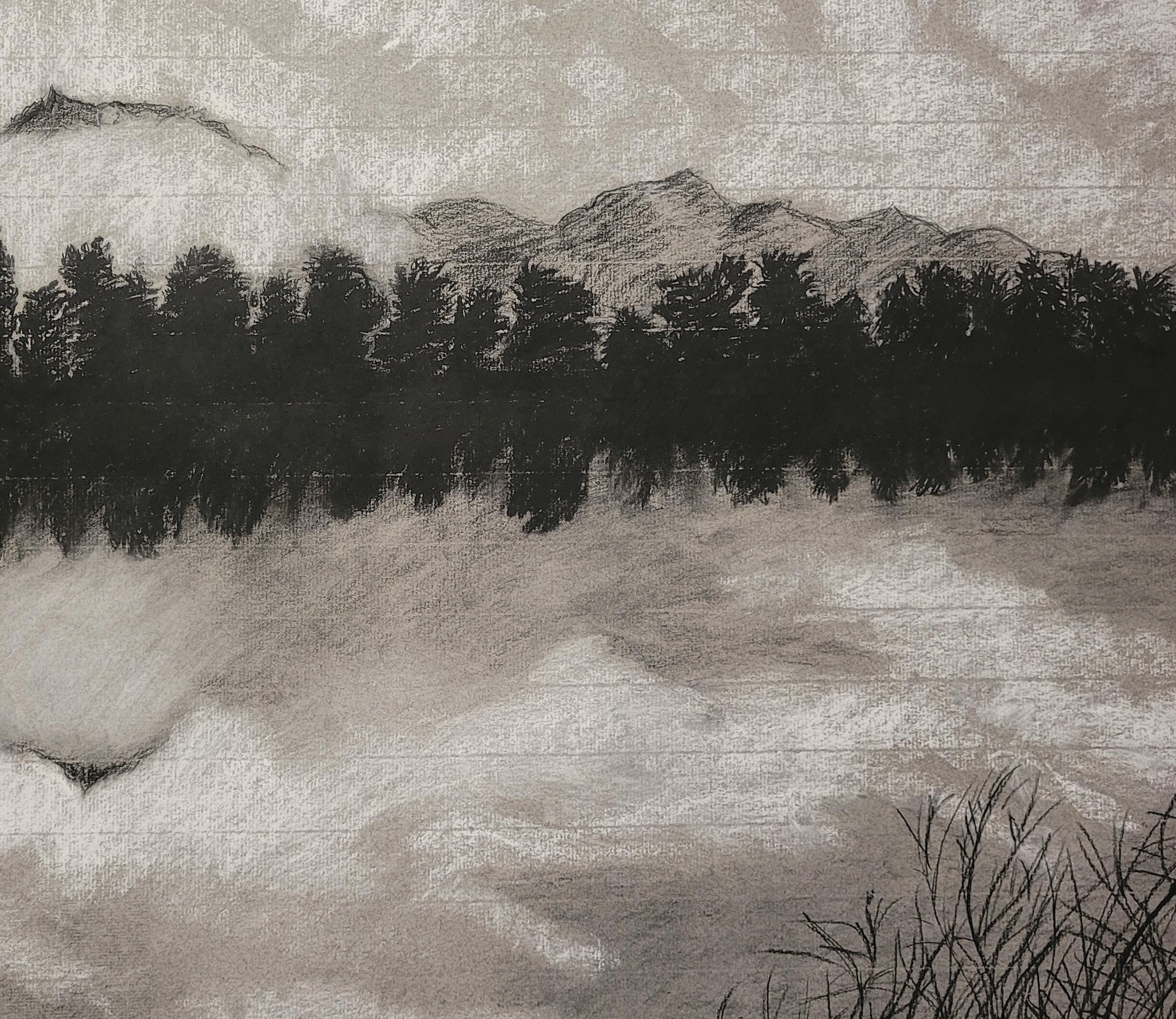

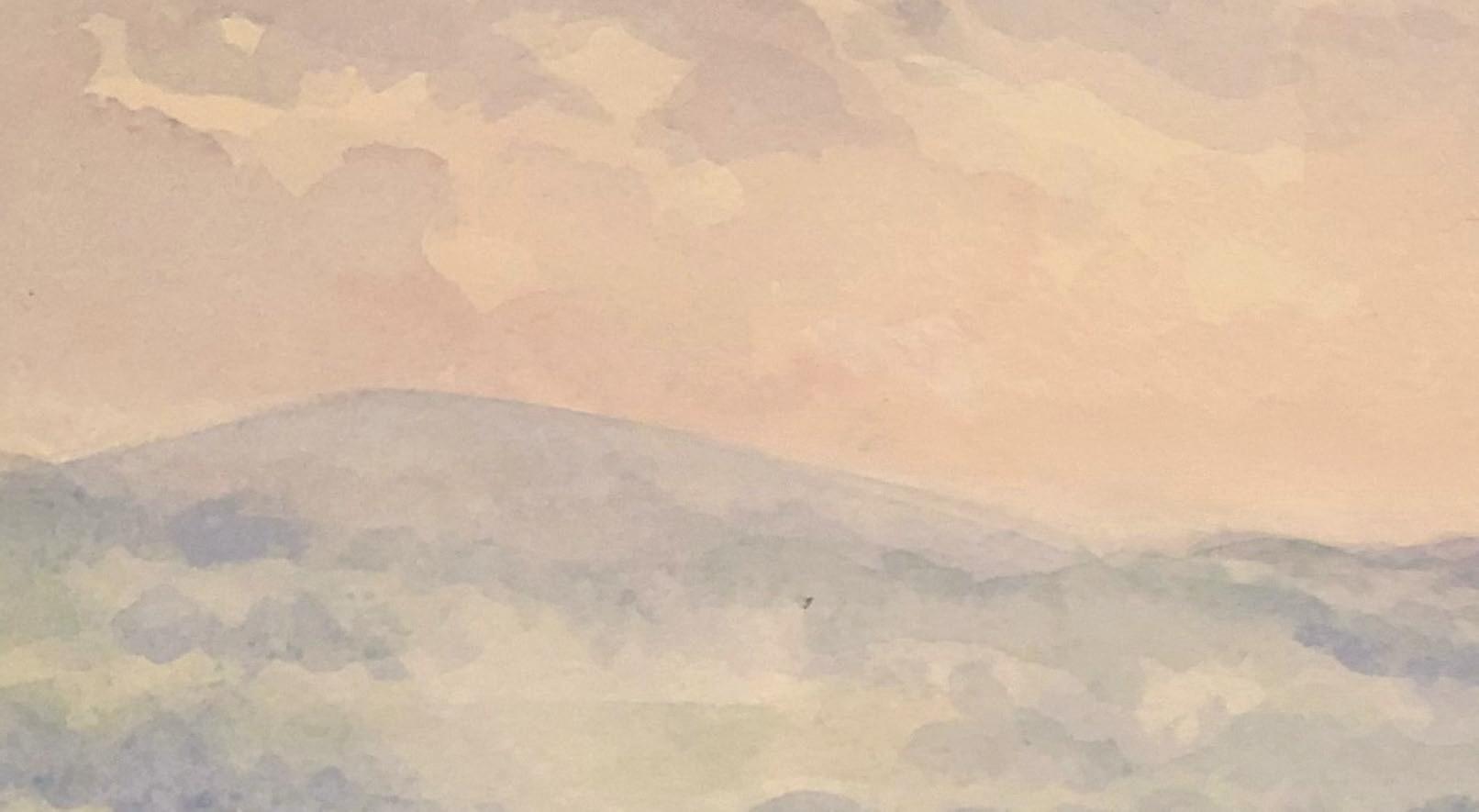

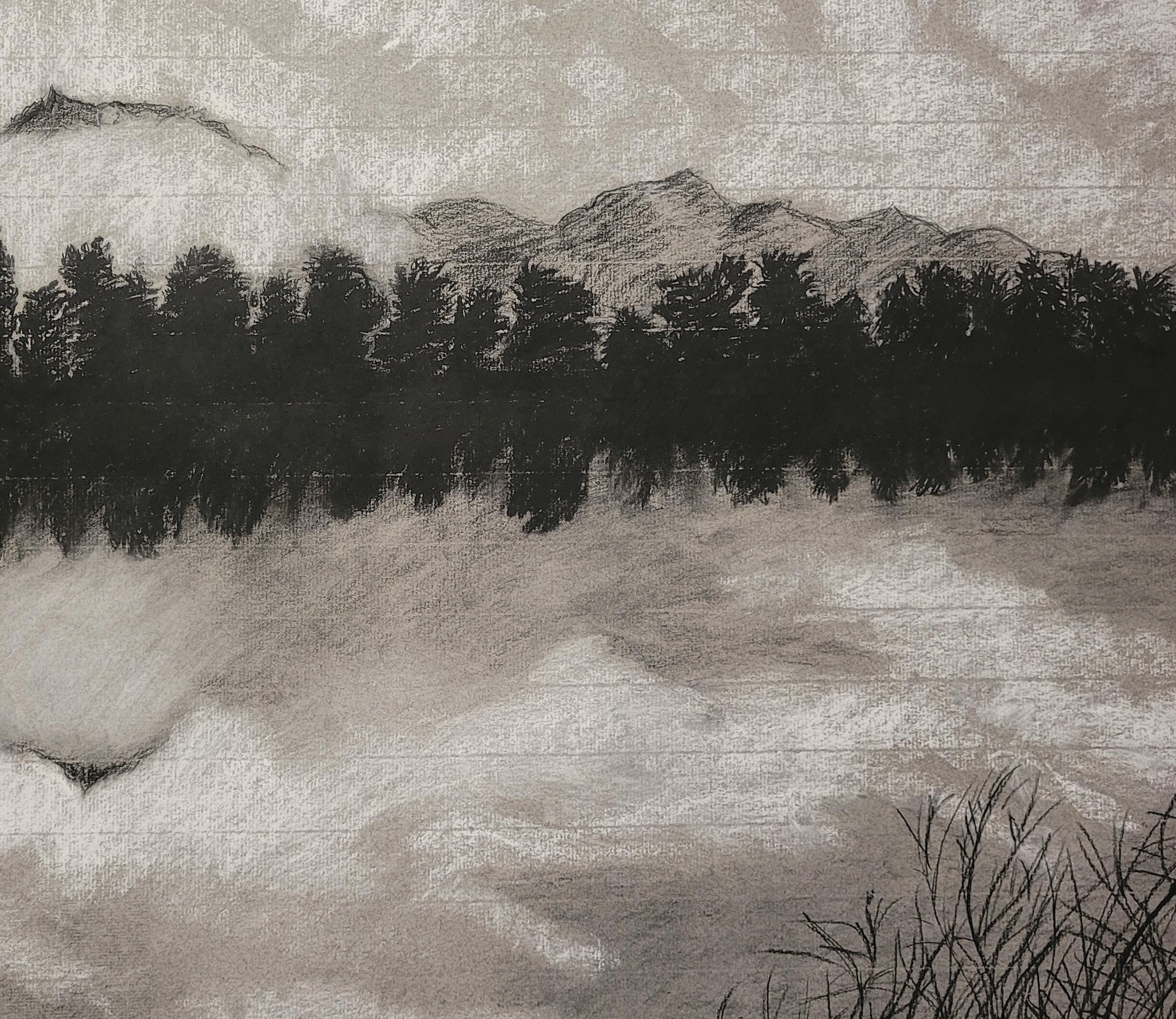

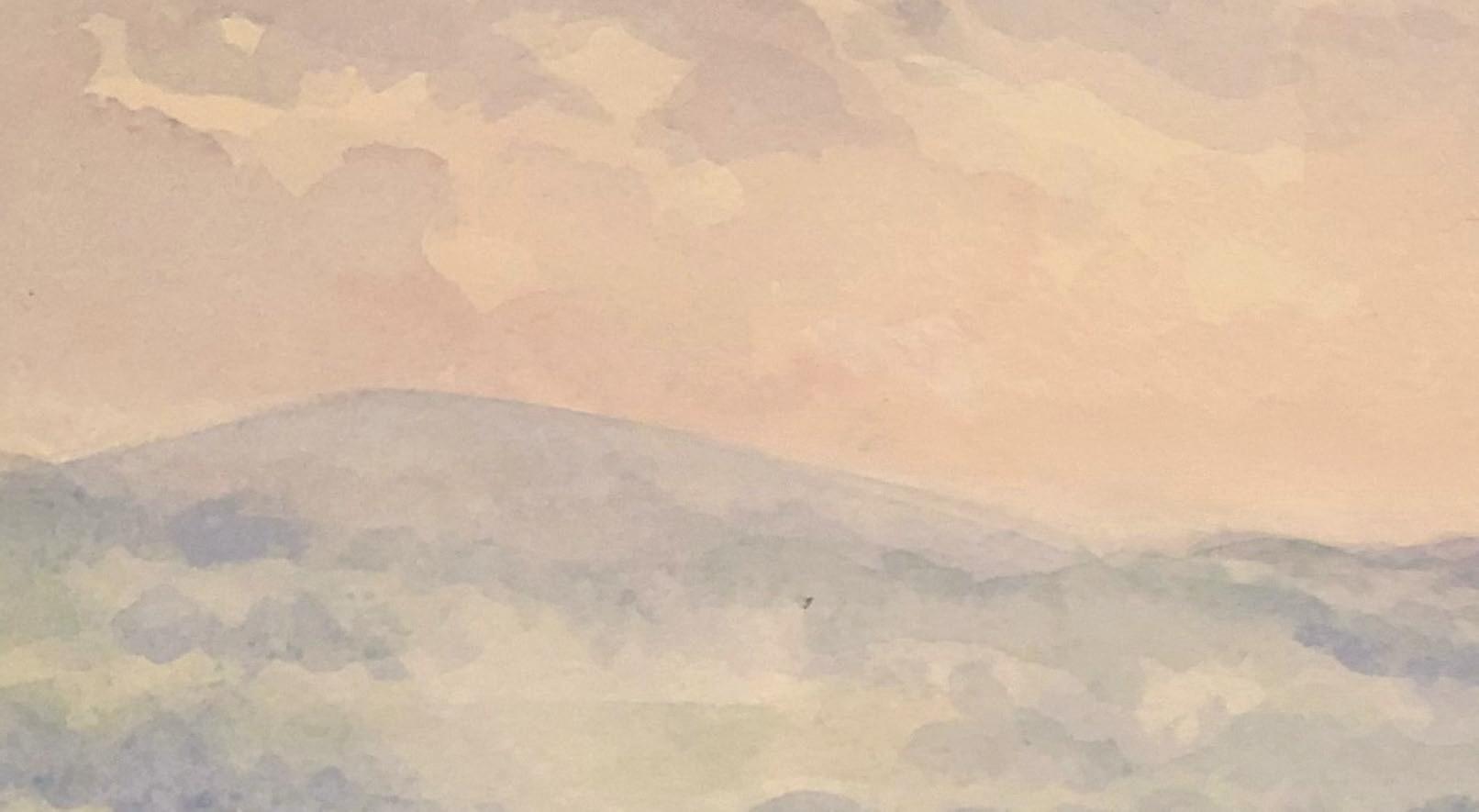

An Austrian Mountain View by Frances Fisher Black and White Charcoal on Gray Drawing Paper

1 John 4: 18-19 by Dolores Hans Photography

1 John 4: 18-19 by Dolores Hans Photography

Snallygaster Claire Moberly

Seventeen-thirty. Whipping winds whisper the secrets of the night to small German children snuggled tight in their beds. Soaring overhead, the “Schneller Geist” stretches its wings over the mountains near Frederick, shirking from painted stars on the barns. What rules in the dark is afraid of the light, and the Quick Ghost casts a shadow over trees, sheep and people. Its eye, red like the blood it drains, scans the valley below.

Two hundred years pass, and the county has changed; more people, new tongues, but the same old fears. The Snallygaster’s wings, larger than ever, now block out the stars it once hid from as its razor-sharp teeth cut through the smoky night. The shadow spreads, covering paper front pages, a Crampton’s Gap nest, the dreams of farmers and children and even the president. A man plummets over a cliff, bled and scorched, and a whistling screech echoes in the valley below.

Nineteen-thirty-two. Whipping winds whisper the legend of the Snallygaster. It’s spread far and wide, drawing curious eyes to the sky hoping to see the shadow soar from the mountains near Frederick. Flying too close to the stars, the Snallygaster finds moonshine beaming out from the ground. Screeching, it slips out of darkness, seeks out the still in Frog Hollow, and circles the spot. What rules in the dark should not go near the light; caught up in the still’s spirit and blinded by the shine, the Snallygaster spirals down into the valley below.

Morning Rosary by Emma Edwards Photography

Morning Rosary by Emma Edwards Photography

Wait and Wonder Hannah

Perry

Always, she is ever watching as time passes by. Leaves change colors as if saying goodbye. Wandering willows wave hello as she looks up from down below.

The rainwater bellows across the ground, and nobody is around to make a sound. Secret longing strikes her heart, neither crying nor sighing at what will come.

Her memory cap remembers the dawn; the darkness drives doom into her soul. Only hope can penetrate through, sparking a flame that has been renewed.

She roamed the shelves in aspiration, looking for a stay-at-home vacation. Singing quietly in the sky, is that a bird flying by?

Those were the days she recalled, as the trouble had been resolved. As she glances out the window, the whole world awaits; she waits and wonders for her new embrace.

45

As she glances out the window, the whole world awaits...

As She Stands in the Mirror

As she stands in the mirror, her eyes shedding tears, she’s begging to be thinner, negativity ringing in her ears.

Her eyes shedding tears, thinking “never pretty enough,” negativity rings in her ears— but she stays tough.

Thinking “never pretty enough,” it is beauty she expects. But she stays tough, trying to find all her perfects.

It is beauty she expects. She’s begging to be thinner, trying to find all her perfects as she stands in the mirror.

46

Amaya Bowman

Festivities of a Full Moon

Jane Allman

I showed the moon my breasts last night; I stood fulfilled in her mysterious light. Gazing upwards with a euphoric grin, we both held confidence in our skin. Blemishes, marks, scratches, and scars matched her craters, adorned by the stars.

Proverbs 3:56 by Dolores Hans Photography

What I Should Have Said

Ashley Walczyk

We know this…

But we also know that you are in a better place. You are no longer suffering from the pains of the world. You are living, happily living, with God in His Kingdom. Jesus Christ helps you, the Holy Spirit guides you, and God loves you. And God gave us the gift of loving you, too. You were loved, dear cousin; you will be forever loved.

Pain.

I cannot help but feel the anguish settling deeper into my heart. The emptiness of the hole you left cannot be filled, nor can it be replaced. You have caused immense grief for the broken hearts in the room, but we cannot be mad at you. We can only forgive you. You were suffering, so you did what you thought best. Someone in here might be thinking, “I should have seen the signs.” Another is saying, “I should have done something to help you.”

Help you…

We cannot help you now. Not physically, that is. He lives on in each and every one of us. The memories we hold dear to our hearts; let it be known that he was loved. He still is loved. He is loved by a mother, a father, a sister, a grandmother, a grandfather, and many aunts, uncles, and cousins. That is why we grieve. We do it because the holes in our hearts cannot be filled; we know this.

Forever loved…

I ask of everyone to remember him in a different light. A light that God now sees him: happy. Let us remember the good times with him. The smiles, the laughter, the good feelings we all share. He was the light in our lives, the one who pushed us to do things we never thought to do, and the one to encourage us to be the best. Remember him the way that he would want you to.

Remember him…

This is not a simple goodbye. It is filled with grief and sorrow. But remember that this goodbye is only a “see you later.” For I believe that he will be there at the gates in the Kingdom of Heaven. His bright smile and light will return to us. And although we won’t feel it now, we will feel completed once more.

Goodbye, dear cousin.

Love you always and forever. Until we meet again.

48

If you are struggling with suicidal tendencies, please contact the National Suicide Hotline: 988.

Heritage by Robert Prender Photography

49

Zygomatic Arch

I didn’t mean to say it.

I had just awoken from a state of blissful comfort. As I left the realm of dreams, my senses returned to me one by one. I smelled your favorite brand of cigarettes, acrid but reassuring all the same. I heard the low mutterings of the TV, still playing in the empty living room. I tasted the bitter sweetness of red wine in the back of my mouth, received secondhand from your deft tongue. I felt your calloused fingertips gently running from my temple, down to my jaw, then up across my cheekbone, over and over. I didn’t dare open my eyes, afraid I would see what I always did. You, slowly leaving the bed and getting dressed, your figure tense and your motions stilted, your eyes already regretful.

Instead, I let your soft wanderings of my zygomatic arch keep me in the place between fantasy and reality, where I was not fully in control of my heart or my mind.

Three little words and suddenly your exploration stopped, two fingers still on the side of my skull.

Fear, sharp and shocking, pierced

my gut, and I was no longer half-asleep. I kept my eyes closed, now worried less about seeing you leave than about seeing the mocking condescension that graced your features whenever I did something particularly stupid.

I was not supposed to get attached or get sentimental. I was supposed to pity her, not envy her. But why must I be the emotionless one? What does she have that I do not? A house, a ring, a promise that is so often broken. Ten years of loving memories, maybe, but time as a measurement is meaningless when it comes to you, when I feel like every brief moment amounts to decades.

I know I am not alone in this sentiment: you can make people feel like they’ve always known you, simply because they meet you and wish they always have.

Then you resumed your careful ministrations, but now it felt different. It felt like goodbye. Still, I refused to open my eyes.

“I love you,” I said.

“I know,” you replied.

50

Seasonal Impression

Sarah Johnson

The season turns over, and I don’t know if it’s ever been quiet enough to hear this chaos before;

I’ve been so distracted by the outside that I didn’t realize my mind was making duplicates.

I will never get my girlhood back; foolishly, I gave it willingly, not knowing how long I would mourn her.

I tried to turn back time and it wasn’t enough; I’ve become my own worst enemy. How can I swear off self-hatred and still feel like this?

There’s a house on East Fourth Street I’ll never see again; this isn’t what I meant on my request for a quiet life. The intent was multicolored stiches of various stages, scratchy wool skirts of a hundred years.

But watch me settle, arthritic fingers in a drafty museum, as you stare up at me; I hate the person I see myself becoming. I’m learning that I can’t change you, but it’s changing me.

51

I will never get my girlhood back; foolishly, I gave it willingly...

Digital Art

Not Allowed by Eden Blottenberger

Not Allowed by Eden Blottenberger

A Villanelle for a Villain

Kayla Jones

Kayla Jones

Your negligence took his life, and all you’re getting is a slap on the wrist. All you had to do was stop, look left and right.

Remembering him feels like being stabbed with a knife. I still remember the last time we kissed. All you had to do was stop, look left and right.

Your negligence took his life— pay attention, and he, on his bike, you could have missed. All you had to do was stop, look left and right.

You’ve brought to us much strife; your “punishment” has us beyond pissed. All you had to do was stop, look left and right.

Your negligence took his life. This pain, this grief, this weight, I wish I could relinquish. All you had to do was stop, look left and right.

You are the villain of our lives. In my heart, the hatred I harbor for you is a cyst. Your negligence stole his life, when all you had to do was stop, look left and right.

53

A Modern Sonnet

Morgan Sturgill

The object of the man’s desire: flattering women dressed like whores for him to use until he bores and counts the ones he can acquire.

She holds her figure to the fire, sculpting herself to something he adores, hiding her suffering behind closed doors, selling her soul to the highest buyer.

She is not his muse. He is just a dude. He fills himself with booze. She keeps him longer with a nude. For sex and thrill their hearts subdued; a better love, they both refuse.

Drops of Heather by Jenna Scalia

Photography

Jeremiah 29:11 by Dolores Hans Photography

Jeremiah 29:11 by Dolores Hans Photography

The Cashier

Tess Koerner

an 80-something-year-old woman talk about her grandson for whom she would be perfect. The old woman’s tremoring hands fumbled with her phone as she showed pictures of her grandson: there he was with the same expression at prom, graduation, and at his uncle’s funeral. The cashier nodded politely and pretended that she just found the man of her dreams. After she took her last bag of groceries, the old woman slipped the cashier a wrinkled receipt where she scribbled her grandson’s phone number on the back. With a wink and a smile, she left the cashier saying, “I’ll be proud to call you my granddaughter.” The cashier tossed the receipt in the wastebasket under her register as soon as the woman left.

At 11:43 a.m., the cashier endured the shriek of the child who vomited on his mother’s chest. The mother yelled at the cashier to make herself useful. She panicked and ran to the bathroom to get paper towels, but when she got back to the checkout, the puke-covered mother was whipping her new Toyota Fortuner out of the parking lot.

At 3:27 p.m., the cashier informed a customer that she will not accept the $100 bill that feels like it was printed at the public library. If the feel of the paper didn’t give it away, the deformed face of Benjamin Franklin did. Before

she could say anything else, the customer covered her face as she ran out of the store. When the cashier told the store manager about the incident, he said, “I thought I trained you better than to let her get away.” He told her to take her 15-minute lunch break.

At 3:49 p.m., during the cashier’s lunch break, she sat in her dad’s 2003 Subaru Forester eating half of a turkey and ham sandwich. Ever since the store manager would make a point to stop in whenever she would be eating in the breakroom asking, “where’s my hug,” she had taken her break in the car. Her timer went off and she wiped the tears from her eyes.

At 5:19 p.m., the cashier watched the toy car, previously located in aisle seven, find its way into a little boy’s pocket and leave the store. The cashier could not help but smile big enough only for herself to see.

At 7:02 p.m., the cashier checked out a customer who couldn’t decide which wine to get for the dinner party he was now late to. The cashier told the man that she prefers the red wine. The cashier didn’t tell him that she has four empty bottles of it in her trashcan at home or that she’d never been invited to a dinner party before.

At 8:54 p.m., the cashier helped a customer locate a pint of red sherbet, Tabasco, and spray cheese for his

58

pregnant wife at home. As he hurriedly threw the items on the belt, he called the cashier a lifesaver and said, “I hope they don’t have you working too late.” The cashier laughed and said, “No, I’m here ‘til 9:30.” She didn’t tell him that she works past the hospital’s visiting hours or that she hasn’t been able to visit her dad in a week.

At 9:37 p.m., the cashier clocked out and sat in her car. She drove to her

apartment, changed out of her uniform, and lay in bed thinking about the future. She didn’t know what her future held because every time she thought about it, she couldn’t picture herself as anything other than a cashier. She fell asleep knowing that tomorrow would look the same as today and so on and so forth, till the days blended together, only being present for the unimportant glimpses into other people’s lives.

59

Streets of Toledo by Emma Edwards Photography

Violins Angela Vodola

A film I forget, I sat next to you, in the chairs that remind me of those church pews. A few years later it was the scene of the crime; I read about it while wasting my time. But we didn’t know back then what would happen, gobstoppers fell to the pit with the violins, and all that was silent suddenly made sound, the noise of our innocence hitting the ground.

Like the band closet conversations we shouldn’t have had, I sat with the cobwebs in the far back, and saw the two blondes talking up a storm. Unaware of the outside scenes of horror, because of the lies they told us that day, as if we wouldn’t find out in some way. The bald man was silent, avoiding the truth, hoping he and the violins could rescue our youth.

Now I envy your innocent eleven, my years of hell contrasting your heaven. With nothing taken from me except everything I was, I still feel guilty for not losing enough. And the violins played too loudly behind the names of the angels crowding our sky. I still envy your innocent eleven; I’m still jealous of your insignificant violins.

Growth by Christopher Woodburn Acrylic Paint on Canvas Paper

61

Matty’s Poem

Eden Blottenberger

People are full of so many things: rolling landscapes of lead, yellow skies of light. Canyons of insecurity and lakes of affection, clouds made of love and stars made of suspicion. So, what does that mean for you? If even the simplest person has streams, then you have rivers. Clear water laden with petals and koi, a symposium of spring and leaves and sun, who looks at me and says, “You are someone.”

Questions and anxiety brim your mind, spilling out of your eyes sometimes. Though, there are storms and the shaking of your hands, they serve to water the countryside within. You grow through your thoughts, nurturing the sprawling landscape inside, becoming a better man each and every time.

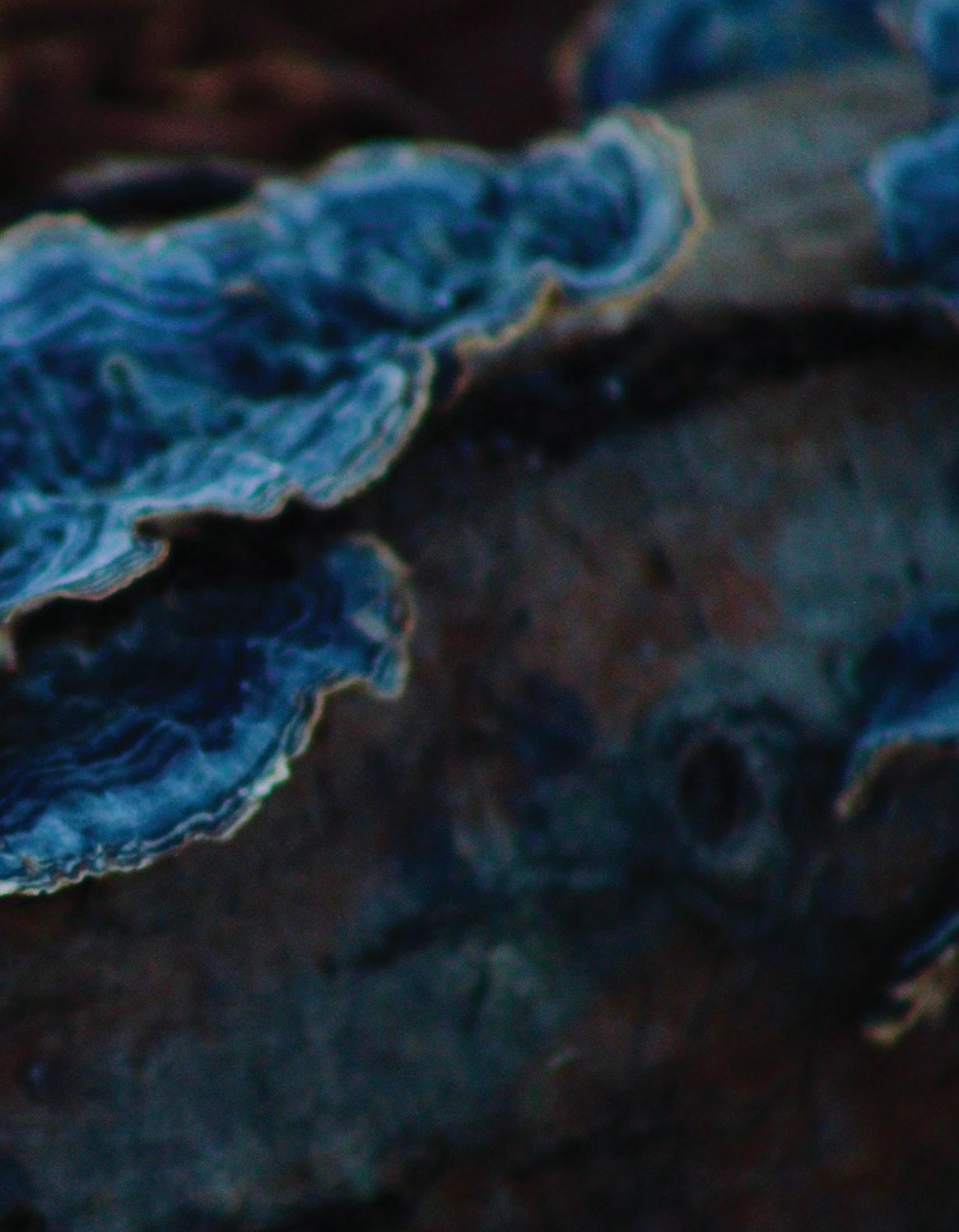

Formation by Robert Prender Photography

Formation by Robert Prender Photography

Loving Stillness

Annabelle Colton

Be still.

Hear the calling of the wind— the silence as it surrounds you. See the roaring of the fire— the brilliance as it enlightens. Smell the wondrous freshness of air— the scent as it rejuvenates. Touch your own heart; prepare it for wondrous gifts and say nothing.

I will whisper stories in your ears, transform the world before you, offer you the most fragrant flowers, connect My heart with yours, and make known to you My love for you.

Be still for Me.

Madonna and Child by Helen Hochschild Acrylic Paint on Canvas

65

The City of Two Rivers

Joanna Kreke

In between Lansing and farmlands, in between soybean fields and corn fields, in between something and nothing, off to the side of Ionia County is Portland, Michigan.

The city of two rivers. Where the sky never ends. Where stars shine brighter. Where everyone keeps their doors unlocked. Home of no more than 5,000 people. A main street stretching two city blocks, dotted with small busnesses, empty buildings, and a Sunoco. An antique shop. A second-hand shop. A shop where you buy paintings. An empty parking lot. A single hotel that once was a Best Western, but is now family-run and doesn’t have a hot tub.

It’s a drive-through town, the kind that has more businesses to the side than in the heart. Where cars from bigger cities with bigger names stop for a quick bite. Where there’s only a McDonald’s and a Wendy’s and a BIGGBY’s near the grocery store off the exit.

Where the family resemblance between other American towns in uncanny. Where a castle can be seen from the highway. It’s a town with the Wheel in the middle of nowhere. Bowling, bar, and restaurant. Where my grandpa sat in, drinking a beer, during the Super Outbreak of 1974 instead of the shelter with the rest of the family. Where we met with my mom’s family. Where we got socks from the vending machine

with bowling pins and a bowling ball on them. It’s a town with luscious plants in the summer and barren emptiness in the winter. Where the last suburbs built were with the G.I. Bill in the 50s. Where my

66

mom broke her foot during basketball practice and told no one. A town where my grandpa’s bench resides, right by the river, name engraved in a gold plaque next to his son’s name.

Where my mom asked my dad to stop at the cemetery. Where she stood in front of two headstones in the snow and

wind. Where my grandpa’s name is engraved next to his son’s name. My Uncle Chuck who sneezed in morning Mass, dressed in his school uniform, and got detention. My Uncle Chuck who never finished high school or puberty. My Uncle Chuck who was born with a smile on his face and a hole in his heart.

A town with a water tower that stands over my grandma’s last home before she was put in a home, her memory fading. It wasn’t the home my mom grew up in—she pointed that house to us once—but I forgot where it was. A town my grandma was born and raised in. A town she lived and raised her seven children. Where she worked and volunteered. Where she read her favorite books. Where she passed on her love of books to her children who in turn passed it onto theirs. A town where she spent her last days. Where her name is engraved beside her loving husband. Where she’s buried next to her son. Where her casket is surrounded by dirt and the remains of her parents and inlaws and siblings.

A town where we all came together under a canopy, dressed in black with tears on our cheeks and the hot summer sun on our backs. Where the afternoon rain met the sun. Where I saw the brightest rainbow in my life and felt her presence. A town where a piece of my heart lives, clenched and stuck in my throat. Where I’m at home. Where I’m a stranger.

67

Venice Canal by Erin Daly Photography

Live Every Day

Kayleen Dominguez

Don’t let age stop you, they say. Everybody grows old but you only live once, so live every day.

The tombstones in the ground lie in dirt and stone, maybe even growing mold. Don’t let age stop you, they say.

Maybe our souls live another day? That’s what some people are told. But you only “live” once, so “live” every day.

Our skin and bones decay. On top of that, we lie cold. Don’t let age stop you, they say.

It’s weird when we turn old and grey. Our life almost feels uncontrolled. But you only live once, so live every day.

Why celebrate if we know we can’t stay? Because it’s what we’re told. Don’t let old age stop you, they say, because you live once, so live every day.

68

69

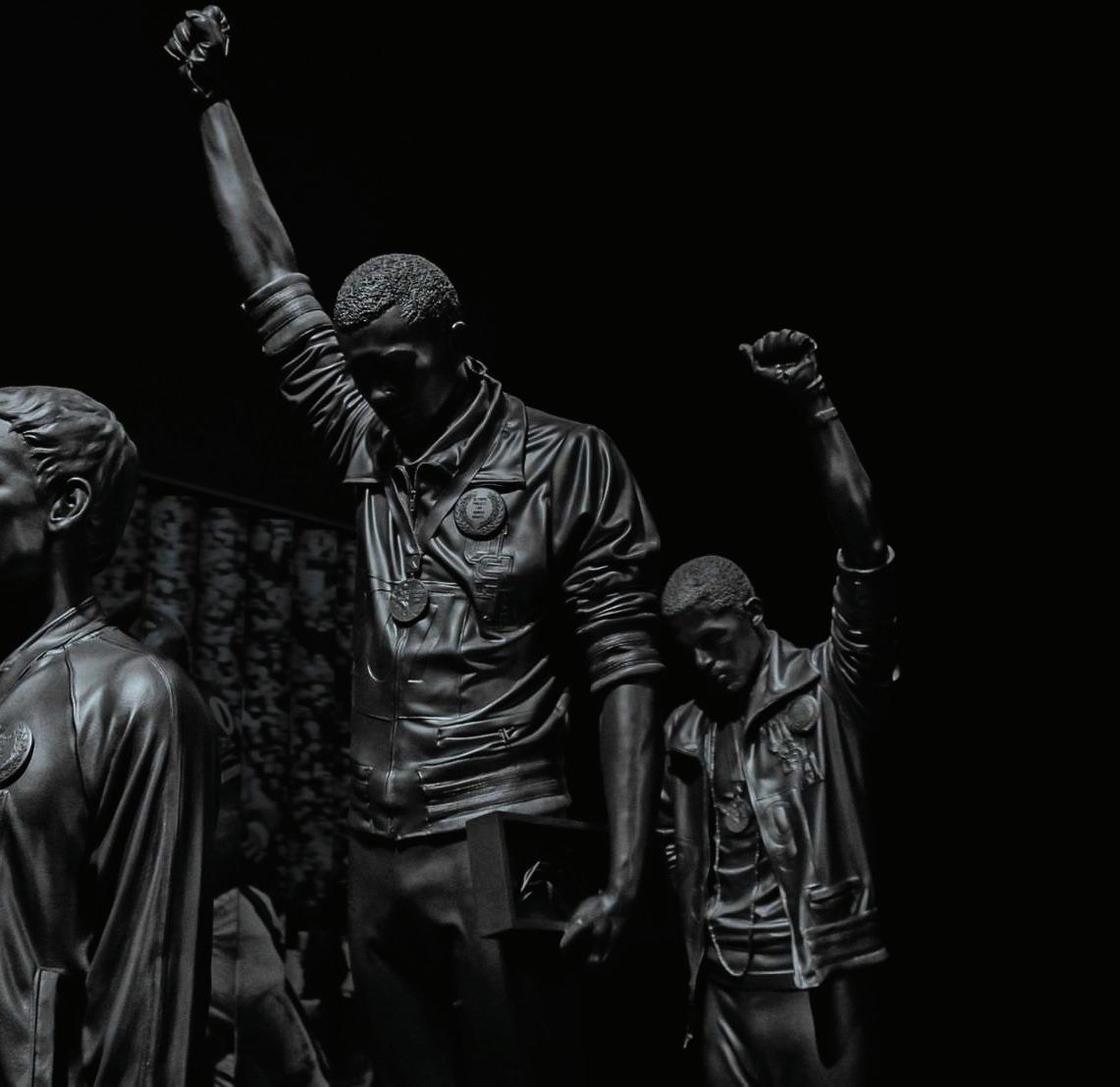

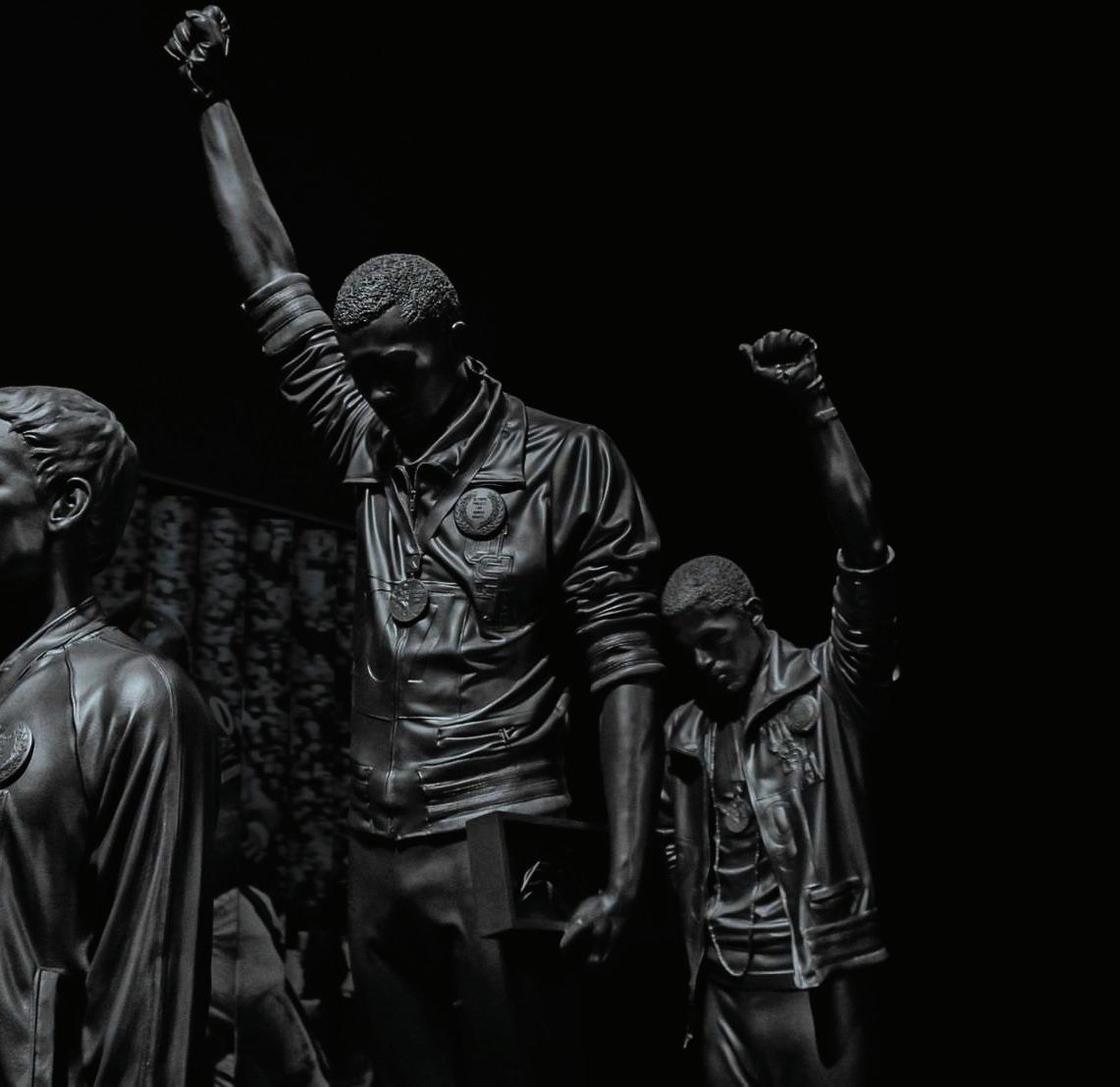

Power by Jaden McNeal-Villafana Photography

The People We Meet

Light rain fell as if it had all the time in the world. Paradise, Wesley thought as he watched from the riverboat’s window, the world framed in glass. The world passing by as if in a film. The world changing scenery every day. And today, it was London: gray and chilly and beautiful, the skyline thinly coated in a veil of mist.

Then he noticed a girl.

She stood along the windows of the boat. Brunette hair, with wavy locks that unraveled out of her bun the way one told a story, with precision and beauty. Blue-gray eyes, like sea glass reflecting the sky. A jawline so sharp it could cut metal, and pale skin colored like snow, fitting in with the blue dress she wore beneath her black peacoat.

She was the most beautiful girl he had ever seen.

Of course, Wesley had thought that about every girl he saw for the past three months while traveling around Europe. But there was something about the way this certain girl side-glanced him, the sparkle in her stare, the way those turquoise eyes ebbed and flowed like the water beneath them. His lips curled into a smile.

To his surprise, she turned away from him.

Wesley walked closer to the girl and propped his elbows on the boat’s railing.

“Beautiful weather, is it not?” he

asked, grinning, watching the rain dot the window.

The girl’s stare flickered back and forth until she pressed her lips together and pointed her gaze back out at the river. “Funny.” Something deep and dark pulled at her voice, despite the light British accent that shaped her words.

“Hmph,” Wesley grunted. He watched the sky and realized there was not much of it to watch; a stretch of gray met all sides of the horizon, and the river’s current ebbed in a harmonious rhythm. “What brings you to London?” he finally asked after a beat of silence.

The girl turned to face him, and in an instant, Wesley’s heart fell. Her eyes, something out of a fairytale, held glints of silver, weighed down by a film of pure sadness. Up close her skin was paler, with hollowed-out spaces where her cheeks should be and bags tugging at her eyes. “Do you always talk to strangers on riverboats?” she asked.

Wesley wondered what she had been through, where she was going. “No,” he replied, a half-smile tugging at his lips. “You’re just so beautiful, I couldn’t help it.”

The slightest hint of a grin in the girl’s face—then, a frown. “What brings you to London?”

Wesley loved this question. He loved lying, pretending that he was

70

someone he wasn’t, because chances were, he would never see the people he encountered again. Like in Paris, when he would tell other tourists that he was a doctor. Or the rich owner of a mansion. Or a prince. However, with this girl, he felt the sudden and dire need to tell the truth. “I’m a travel writer,” he said. “I do freelance writing and whatnot.” He adjusted the straps of his backpack and smiled, thinking of the hostel he slept in last night outside of London.

“That’s lovely,” replied the girl.

“It’s called The Travels of Wesley Parkton.”

“Wesley,” she repeated, smiling with her eyes. “I’m Charlotte.”

“Charlotte,” he said, and the name sounded like music, the way the first syllable was stressed, how the rhythm of the letters flowed like a song. “Charlotte, when we dock, can I buy you a cup of coffee?”

Silence once more, a silence filled with the thick salt breeze. Then, a small hint of laughter. “Okay,” Charlotte said,

She was the most beautiful girl he had ever seen...

“You sound sarcastic.”

Laughter bubbled out of the girl, sounding like summer and bright skies and warmth. “I promise, I’m not.” For the first time in their conversation, she smiled fully, as if her lips were always meant to part upwards. “Where have you traveled?”

“Oh, you know. Every place that’s so fantasized in America. France, the Netherlands, and Belgium. Now the U.K.”

“Wow. You see, I could never do that.”

Wesley leaned closer. “You should join me.”

The girl laughed again. “No, thank you.”

“Fine,” he said, backing away. “Can I write about you in my book, then?”

“You’re writing a book?”

looking down at the water, her hollowed cheeks tinged the color of roses. “That sounds good.” ...

A translucent fog settled over the city of London as Charlotte and Wesley disembarked. The River Thames, deep gray, caught sparkles from the sparse rays of sunlight, and a slight chill from the water soaked the air. April, midday, and London was as beautiful as ever.

“Do you know any cafés?” Wesley asked as they joined the throng of tourists shaking out umbrellas and locales stepping out of sandwich shops with takeaway bags. Their path was carved out right next to the river as they passed by the skyline, Big Ben and London Bridge and every building in between.

“There should be one down here,” she said, glimsping ahead. “It’s

71

really nice. Right next to a pub, with a telephone booth in the front.”

Café Paul appeared before them, nestled between a pub and a bookshop. The door was painted a bright blue, the smallest hint of budding spring flowers planted by the windowsills. “Here it is,” said Charlotte. She smiled, and it was so pure and innocent and filled with the kind of light that glittered before the sunrise at dawn.

Inside, the café bustled with the afternoon crowd and smelled of bold coffee beans and warmth. Choosing a table overlooking the streets, Wesley pulled out Charlotte’s chair for her. “What kind of coffee would you like?”

“An Americano is fine.”

“No cream or sugar?”

“No, thank you.”

Wesley nodded and ordered an Americano and a vanilla latte, bringing both back to the table. “Black coffee, huh?”

Charlotte took a sip. “Yeah.”

“Interesting.” He longed to know more. “Do you live in London?”

She shook her head.

“Are you here on holiday?”

“No,” she finally said, and then grinned slightly. “Can’t we just enjoy our coffee?”

Half-smiling, Wesley nodded. “Yes, of course.” He sipped his latte, the bitter vanilla warming him from the spring chill. “How did you know about this café, then?”

She looked up. “I’m sorry?”

72

The People We Meet

73

City Center by Emma Edwards Photography

“The café. You seemed to know exactly where it was. Yet you don’t live here, and you’re not on holiday.”

Charlotte couldn’t help but smile. “Okay. What do you want to know?”

Wesley stared into her eyes and wanted to reach his hand to hers, wanted to go home with her and make her dinner even though he had no home and didn’t know where he would sleep that night. However, sitting at the Café Paul holding a vanilla latte, he grinned.

“Anything.”

“Well, I love to read. In college I studied English and business, although I hated business and just wanted to read. Last year I graduated, and like you, I’m a writer.”

Wesley nodded. “And what do you write?”

tell.”

“You’re a travel writer,” she said. “From America, I assume?”

Wesley nodded. “Although I don’t say that anymore.”

“Why’s that?”

“There wasn’t much left for me there. Family, I mean.” Wesley kept his mouth open to say more, but nothing, no stream of words left his mind. Instead, he focused his eyes on Charlotte, the pang of an undefined emotion eating away at his heart.

Before he could say anything else, she spoke. “I’m sorry.”

When he laughed, it sounded forced. “Don’t be. I love travelling. Today, London is my home.”

“What do you write about?”

her coffee...

“Fiction.”

“Will you write about me?”

“It depends. Will you write about me?”

“I already said I would.”

“Okay. I will too.”

Two smiles, two pairs of sparkling eyes, and the smell of coffee.

Charlotte cupped her Americano. “What about you?”

Wesley tossed his head back as if to laugh, but instead a smirk curled at the edge of his lips. “There’s not much to

Wesley sipped his latte. “Oh, you know. The things I see, the people I meet.”

Charlotte smiled, dimples pressing into her skin. “So, you don’t know where you’re headed to next?”

“Depends. Where are you headed?”

Laughing, she looked down. “I’m not sure at the moment.”

“Charlotte, if I may ask, why are you here?” he repeated, speaking more sincerely.

It began to rain, sprinkles of mist

74

A beauty captured in the way she smiled while watching the sky or sipping

dotting the windowpane. It was funny, Wesley noticed, how people didn’t suddenly grab for their umbrellas in London. He watched people on the streets let the rain braid into their hair, let the drizzles soak their clothes. He couldn’t imagine the skies blue—only gray.

“My sister died,” she finally said, and the sentence alone caught Wesley by surprise, because he didn’t even think she would respond. But she did, the words penetrating the air, her eyes sad and tearing up because her sister died.

Wesley couldn’t help but stare. Stare at the pure grief—that’s what it was— planted deep in her eyes, spreading to every part of her body. Stare at the light strands of hair poking from her bun. Stare at the beauty she held so naturally, despite the drained skin and deep eye bags and thinned face, a beauty captured in the way she smiled while watching the sky or sipping her coffee.

“I’m so sorry,” he finally said.

“It’s okay. Truly,” said Charlotte. “That’s why I’m here. Her funeral is today.”

“Oh,” said Wesley. “Did you need to get going, then?”

Folding her napkin, Charlotte shook her head. “It’s in Windsor.”

Wesley’s eyes widened. “Windsor?”

“Yes.”

“And you’re here.”

“Yes.”

Creasing his eyebrows in disbelief, he wrapped his hands around the mug.

“May I ask what you’re doing all the

way over here?”

Charlotte smiled sadly, like she had expected this question all along. “I don’t want to go.”

“Why not?”

“I just can’t,” she admitted, and her voice sounded light and shallow as if she were about to cry.

“I see.”

“Her name was Grace. She was my best friend.”

Wesley nodded; he wasn’t sure what to ask or what to say. Her hardly knew this girl and had now learned all about her suffering. “I’m so sorry.”

“It’s okay. I just wanted to take a daytrip here, that’s all.”

“Why London?”

Charlotte smiled. More hair fell out of her bun. She cursed softly and undid her hair, sending brunette waves across her shoulders. “I did grow up here, with Grace. Lived in a little flat, just ten minutes from this area. We moved once my father relocated his job.” He could tell she was reliving the memories as she spoke.

“How did she—”

“Car wreck.”

“Oh.”

A beat of silence passed. “She was younger, as well. Still in college. Isn’t that crazy?”

Wesley ignored the lightness in Charlotte’s voice. “You should be at her funeral.”

“I didn’t want to go,” she argued. “Plus, it was this morning. It’s over

75 The People We Meet

now.” Charlotte looked over her shoulder at a couple sitting at a table next to them, then flickered her eyes back towards Wesley.

“What about your family?” he asked.

“They will be okay.”

“They probably need you.”