lighted vol. 43 currents corners

lighted corners

Cover: “Free Bird” by Trinity Sandacz Photography

lighted corners

vol. 43 currents

Mount St. Mary’s University

16300 Old Emmitsburg Road

Emmitsburg, MD 21727

301-447-6122

lightedcorners@msmary.edu

msmary.edu/lightedcorners

www.instagram.com/lightedcorners

currents

Volume 43 Spring 2024

Policy Statement

Lighted Corners recruits its staff in September and opens for submissions in November. Students from across the university submit works that reflect diverse perspectives and themes. After removing the names of the contributors, the Lighted Corners staff reviews submissions. The editors make final selections and design the layout for the magazine by striving to create a union between word, image, and theme. All Mount students, regardless of major, are welcome to join the staff and submit their work for possible publication.

Production

Lighted Corners partners with Valley Graphic Service in Frederick, Maryland. 300 copies are printed by the company. The Spring 2024 issue is printed on 100# Gloss Cover and the inside is 70# Uncoated Opaque Text. The magazine body text is set in Georgia, headers are set in Didot, and titleset in Lao MN. Lighted Corners is created using Adobe Creative Cloud. Editor-in-Chief Claire Doll, Design Editor Emma Edwards, and Fiction Editor Erin Daly worked collaboratively on the layout of the magazine.

About

Lighted Corners is an annual literary and arts magazine that publishes poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, fine art, and photography created by students of Mount St. Mary’s University. Lighted Corners holds memberships with the Columbia Scholastic Press Association and Sigma Tau Delta.

The Lighted Corners logo was designed by Rachel Donohue, C’21. Rachel was a long-time Design Editor and served as Editor-in-Chief for Volume 40.

Awards

The Columbia Scholastic Press Association is an international student press association, founded in 1925, whose goal is to unite student journalists and faculty advisers at schools and colleges through educational conferences, idea exchanges, textbooks, critiques, and award programs.

Gold Medalist 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2012, 2008

Silver Medalist 2018, 2013, 2011, 2010, 2009

Gold Crown Award 2022

Silver Crown Award 2021, 2014

Gold Circle Awards

2023 to Eleanor Fisher, Ana Purchiaroni, Kayla Jones, Ashley Walczyk, Helen Hochschild, Frances Fisher, Robert Prender, Claire Doll

2022 to Rebekah Balick, Victoria Tyler, Megan Ulmer

2021 to Rebekah Balick, Claire Doll, Rachel Donohue, Emmy Jansen, Kayla Jones

The William Heath Award is an honor earned by the student who demonstrates outstanding achievement in creative writing. For more than twenty-five years, Dr. William Heath taught American literature and creative writing at Mount St. Mary’s University.

Claire Doll 2023

Betsy Busch 2022

Our contributors have earned recognition in Delta Epsilon Sigma’s undergraduate writing competition. DES is a national scholastic honor society established in 1939 for students of Catholic universities and colleges in the United States.

Erin Daly 2023 Second Place in Poetry for “Heavenly Bodies”

Claire Doll 2023 Second Place in Short Fiction for “Dear Gracie”

plain china: the Best Undergraduate Writing is an ever-growing anthology featuring young writers and artists on a national level. The following pieces from Volume 41 of Lighted Corners have been selected for plain china:

“The Dawn” by Tess Boegel

“Swimming Lessons” & “Sitting Under Starry Skies” by Claire Doll

“Los Pensamientos de la Llorana” by Alyssa Pierangeli

“Staring at my Bookshelf” by Angela Vodola

our team

Editor-in-Chief

Design Editor

Assistant Design Editor

Fiction Editors

Assistant Fiction Editors

Creative Nonfiction Editors

Assistant Creative Nonfiction Editors

Poetry Editors

Assistant Poetry Editor

Art Editor

Assistant Art Editor

Public Relations Manager

Faculty Adviser

Staff

Claire Doll Emma Edwards

Anna Dang

Erin Daly & Ashley Walczyk

Hannah Perry & Sophi Toth-Fejel

Gabe Vilches & Hailey Fulmer

Amaya Bowman & Christopher Derocher

Margaret Stine & Kayleen Dominguez

Tamara Olobo

Robert Prender

Dolores Hans Kayla Jones

Dr. Tom Bligh

Joshua Aybar, Rachel Hoerner, Sarah King, Tess Koerner, Kayla Lijewski, Veronica Marchak, Maureen Pham, Clover Satchell, Jenna Scalia, Gavin Schisler, Kelechi Udom “Percy Jackson”

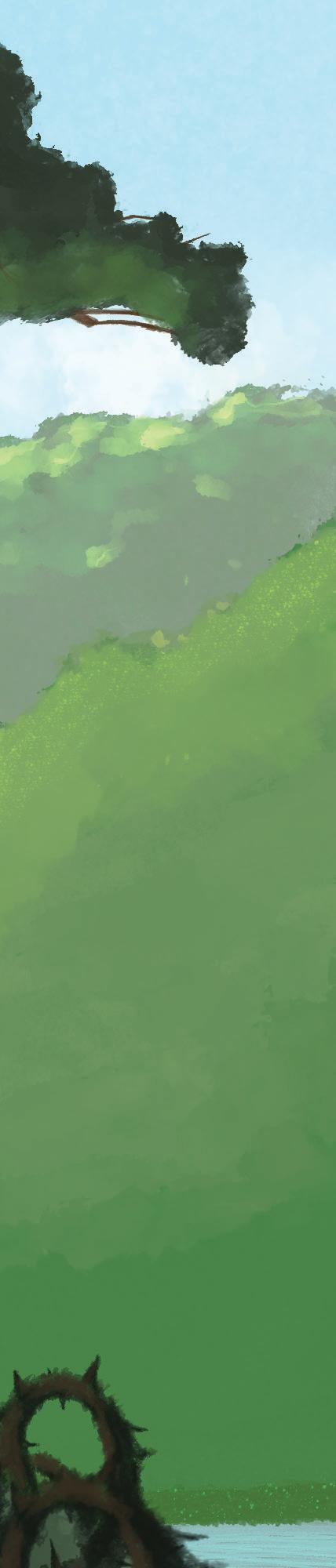

on

by Aubrey Preske Oil

Canvas

editor’s note

One of my earliest memories is of the sea. It’s late summer in Ocean City, Maryland, and I’m standing at the fringes of the first ocean I’ll ever know. Foamy water trickles between my toes, crashing onto the sand, then suddenly reels backwards. Beside me, my father holds my hand, and my mother lies on a towel nearby. My sister stands knee-deep in the tide, and I am four or five, somewhere in between, a mess of tangled hair and sunburnt skin. I watch how the waves are constant, a promise; there is never a moment that the water will not return back to the ocean.

Don’t we do the same? Life is but a stream of currents, pushing and pulling us in different directions, yet we always retreat back to the sea. We return to our mothers and fathers, to lost loves, to memories tethered to our past. Our oceans are vast, filled with heartache, but familiar, what we long for when the world outside grows cold and strange. We are humans, containing memories as countless as the peaks in the ocean waves, and the power of a single current can bring us back or force us into something new.

I’m twenty-two now, no longer the little girl standing on the shore of Ocean City. The currents of my life have led me here, as an aspiring writer, leaving my words in Lighted Corners; I am eternally thankful that for four years, my writing has found a home in this journal. That, once each spring, poetry, prose, and art marry to create an intricate display of student voices. For me, creative writing is a love; it’s something I find myself reaching towards when all else feels far in this giant world, something I can call my own. No matter where the currents take me after college, I’ll never let writing go.

For that, I want to thank our adviser, Dr. Bligh. His unwavering support for his students and Lighted Corners is absolutely inspiring, and I am so grateful for his leadership and devotion to creative writing. Thank you to Dr. Mitra and the Mount St. Mary’s English Department for constantly celebrating the beauty of the English language. Thank you to Robin and the Valley Graphic Service team for printing Lighted Corners with dedication, to Mr. Joe Paciella for your continuous help with the magazine, and thank you to President Trainor, Dean Zygmont, and Provost Creasman; I cannot express how grateful I am for a college that supports the literary arts. And lastly, thank you to my staff, and to the writers and artists that make up this magazine. Each one of you is a talented, worthy person whose currents will lead you to amazing things. Thank you for leaving a piece of yourselves here.

In Volume 43, we reflect on the currents that move us through regret and loss, but also toward hope and adventure. Through lyrical poetry and imaginative art we dive deep beneath our surfaces, exploring our beautiful depths, our darkest trenches. We invite you, like the seagulls on our cover, to glide above the push and pull of our ocean tides, our reaches and returns to what we know and love: our mothers, our childhoods, our imagined worlds. Be moved by these pieces the way you might be moved while swimming in the ocean under a wide, summer sky.

Editor-in-Chief

Claire Doll

Abe and His Sushi and His Baskets • 46-53

Joshua Aybar

I Cry into My Bowl of Spaghetti • 58-59

Tess Koerner

Invisible Strings • 61-69

Kayla Jones

Dear Gracie • 80-85

Claire Doll

Boiling Point • 87

Erin Daly

Freezing Point • 88

Erin Daly

Untitled Ocean • 96

Erin Daly

Mausoleum • 98-101

Savannah Laux

c o n t e n t s fiction creative nonfiction poetry

Nanny • 17

Emma Edwards

Heartbeats • 24-28

Claire Doll

Plays from my Diary • 40

Tess Koerner

Pretty Copper Rings • 42-43

Abigail Jarrett

My Hair and Me • 73-76

Rayelle Weir

Exposure • 92

Abigail Jarrett

On Growing • 102-103

Claire Doll

Considering Summer • 14

Margaret Stine

Life in the Classroom • 18

Amaya Bowman

Mother’s Sonnet • 20

Jane Allman

Blooms of Time • 23

Kiara Ramirez

Waves of Emotion • 30

Sarah King

Ode to the House with the Outgrown Peach Tree • 33

Kiara Ramirez

You Cannot be Mine • 34

Joshua Aybar

Upon the Conquest of Coffee • 36-39

Anna Dang

Fantastical Truth • 44

Annabelle Colton

Milk • 54

Sasha Shandrenko

Forest Trail • 60

Sarah King

Pearls, Rejected • 7o

Jane Allman

Forever Still • 79

Krissy Roots

Growing Old Together • 91

Kayla Canfield

In the Company of Wasps • 95

Kayla Canfield

photography

Free Bird • Cover

Trinity Sandacz

The Storm • 12-13

Caliann Dietz

Grandma’s Porch • 16

Emma Edwards

Born to be Wild • 18-19

Trinity Sandacz

Emma in Flowers • 22-23

Alexandra Eastman

Mist Opportunity • 32

Dolores Hans

Mountains • 36-37

Kevin Ryan

Catedral de Sevilla Spire • 40-41

Robert Prender

Fuinneog Bhinn Éadair • 42-43

Tess Koerner

Good Old Days • 48-49

Caliann Dietz

Catedral de Sevilla • 56-57

Robert Prender

Onism • 58-59

Jenna Scalia

Balance • 60

Robert Prender

Morning Stroll • 62-63

Alexandra Eastman

Cornucopia • 70-71

Tess Koerner

Rights • 72

Kaitlynn Lowman

Tools of an Artist • 78

Caliann Dietz

When We Were Young • 80-81

Dolores Hans

Ocean Air • 93

Hailey Fulmer

Beloved Facade • 94

Dolores Hans

Moon • 96-97

Caliann Dietz

I measc socracht na sléibhte • 100-101

Tess Koerner

Good Old Days • 104-105

Dolores Hans

visual art

Percy Jackson • 7

Aubrey Preske

Stoneware • 15

Emma Edwards

Birds • 21

Emma Edwards

A Slope of Yellow and Blue • 25

Anna Dang

Alaskan Seaside • 30-31

Alexandra Eastman

Called in a Dream • 35

Anna Dang

St. Michael the Archangel • 45

Anna Dang

Kira • 54-55

Aubrey Preske

Dawn • 86

Aubrey Preske

The Other End • 90-91

Annabelle Colton

Next page: “The Storm” by Caliann Dietz Photography

“like

as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

so do our minutes hasten to their end.”

60

William Shakespeare, Sonnet

Considering Summer

The field of flowers is endless— warm breeze, hot sunbeams; it is summer.

Margaret Stine

The flowers grasp your ankles, stems reaching for a touch, petals leaning for a kiss. You trudge on— is this not life?

In the middle of the field, you stop. You are surrounded by beauty that words are unable to express. Why try? The flowers don’t seem to mind, brushing against you, whispering secrets you cannot understand. The sun looks down in pity.

Flowers

14 lighted corners

“Stoneware” by Emma Edwards Ceramic and

Nanny

Emma Edwards

A cardigan hangs in my closet with colorful birdhouses stitched into it. Soft, navy buttons tell me it has been well loved. I picked it out of a faded bin filled to the brim with her clothes before I moved back to Maryland. The smell was familiar for only a few days, like sleepovers on her couch, tucked in with blankets that have comforted generations before me.

creates the breeze that makes it ring its mournful tune; before dawn, the mourning dove duets with the hollow, rusted metal.

A short poem is pinned to my bulletin board. On the backside is a photo of her. She wears a bright beaded teal, beaming, matching her wild, well-kept garden. When I remember her, I hear buzzing hummingbirds sipping sugar water

before dawn, the mourning dove duets with the hollow, rusted metal

A bluebird figurine now sits on my bookcase, plucked from its perch amongst swallows and cardinals in her kitchen windowsill. My mother claimed it for me when I told her I wanted it, before the frenzy of extended family swooped in to treasure away the rest of her belongings. It sings a sweet tune if all is quiet.

A set of wind chimes hang outside my doors. The long move from her porch to mine must have made them tired; they are corroded, a dull brown against the rich, firtree green that acts as their background. A painted mountain range

“Grandma’s Porch” by Emma Edwards Photography

from the back porch railing. I smell strong coffee in modest white mugs with muted gold rims. I feel the soft summer breeze as it strokes my hair, putting me to sleep on the beloved wooden porch couch. I see her compassionate wrinkled hands, busy setting the strong oak dining room table for the next twenty-some person meal.

By the finches that ate seed from the feeder in her backyard, always well stocked; by the flowers that stretched their necks to see into her living room windows; by the crisp mountain air that dried her blankets on century-old clotheslines; by the sun who woke up every day to greet only her, she was well loved.

17 currents

Life in the Classroom

Pencils, crayons, and caffeine: the teacher’s life for me.

Children laughing and crying and singing and learning. One’s peeing in the corner, one’s yelling my name. Miss B., MISS B., I am going insane. It’s my passion, it’s an art, I tell myself.

My hair thrown in a bun, tossed books on the shelf.

I feel like there’s no time to myself.

It’s glamor, it’s grace, but in reality, it’s just sneezes to the face. I love my job, I really do, but sometimes I get through the day and just say PHEW. At least I did it, I say to myself. Being a teacher, you don’t get much time to yourself. Kids screaming and yelling might seem like a lot, but the product of their success is worth all the snot.

Amaya Bowman

“Born to be Wild” by Trinity Sandacz Photography

Mother’s Sonnet

Jane Allman

Under your eye, my quick youth gleamed galore with those pink star-studded slippers that kept my tiny toes encased, safe through my door which you’d quietly crack, to see I slept.

Beneath the blankets, knitted by Nana and piled on by you, I squirmed and shrunk into cocoons of comfort. Pajamas plaid with matching set in your heirloom trunk. I met adolescence on sleepless nights with long-lasting lacerations, white to red. Here I faced budding woman’s lonesome plight and by morning you cleaned my stained bed.

Mother you’re mine, your nourishment innate. We bleed, graciously gifted to create.

20

corners

lighted

Edwards Charcoal on Canvas

“Birds” by Emma

22 lighted corners

Blooms of Time

Kiara Ramirez

In the quiet dusk of my childhood room, where shadows danced upon the walls with glee, memories linger, like flowers in full bloom.

A haven of dreams, where I'd find my way to zoom through realms of make-believe, wild and free, in the quiet dusk of my childhood room.

Stuffed animals gathered, their faces a gentle gloom, witnesses to secrets shared just with me; memories linger, like flowers in full bloom.

As time unfurled, my heart began to assume the changes that life would inevitably decree, in the quiet dusk of my childhood room.

Now, as I stand on the precipice of gloom, surveying the artifacts of who I used to be, a new chapter unfolds, in a different room.

The walls may change, and the space may resume, yet, in my heart, the essence remains free. A new chapter unfolds, in a different room. Memories linger, like flowers in full bloom.

“Emma in Flowers”

by Alexandra Eastman Photography

23 currents

Heartbeats

Claire Doll

I’m five.

The world is bigger than I could ever fathom, and right now, we’re driving in a town far away from home. I watch the sky change patterns from the car window; bright blue turns to scattered clouds turns to streaks of winter sunlight. I fall asleep, then wake up to Dad parking the car in front of a small strip of stores. When I ask Mama where we are, she says, “It’s a surprise.”

She unbuckles me from my car seat and the air here, at this surprise, feels different. It is colder, sharper, even at the very end of February.

I cannot read very well, so when we walk into a store between the Chinese restaurant and a barbershop, I blink and follow Mama. I’m small and scared, holding onto my mother’s hand, suddenly breathing in the smell of dogs as she opens the door.

Puppies.

So many puppies, crowded in little cages, a melody of barks swelling like a symphony. There are big puppies, scratching at the walls of their crates, letting out deep barks with their begging black eyes. There are smaller puppies, squealing and whining.

And then there is you.

You’re tiny, golden brown and

black, with eyes big and twinkly. Ears, triangular and pointed. Your nose perfect, your paws delicate and small. As you sit in the corner of your crate, you look right at me, wearing an expression of fear. It is as if we are the only two people— creatures—in this store.

When Mama and Dad ask me which puppy I like, which one I want to keep and take home and grow up with, I choose you.

We name you Toby, after the country singer, Toby Keith.

We teach you the basic things: how to sit, how to raise your paw. When you lie down, you stretch your arms and legs, you curl your tongue in a yawn, you perk your ears up, then fold them back. I go to school and tell all my friends about you. His name is Toby, I say to them. He’s a silky terrier. He’s my best friend. They tell me best friends can’t be dogs, only people. I don’t believe them for a second.

We do everything together. We go on walks and watch movies. We run outside and you dash into the garden beds—it’s May, and you get lost in the flowers—and I wait anxiously for your return. When I play teacher or doctor, I pretend you are my student, my patient. I believe you can talk, so I go on and on about my friends, about my “A Slope of Yellow and Blue” by Anna Dang Acrylic Paint on Canvas

24 lighted corners

second-grade science class, and recess today. You don’t talk back yet, but it’s okay. I know you will. I dress you up in American Girl Doll clothes and take your pulse with my toy stethoscope and I can hear your heartbeat, a beautiful thud, thud reminding me that you are here, that you are mine.

“You do realize he’s just a dog, right?”

Just a dog. The words sting, because you’re a pet, Toby.

Doesn’t that make you more than just an animal?

you look up at me with those twinkly brown eyes,

I’m eleven, and you are lost.

Through my tear-streaked vision, I hang the posters around my neighborhood. The sky is fully blue, but hints of the sunset stretch into the clouds. It is summer. It will grow darker later, but still.

I had left the gate open, and by some animal instinct, you ran out. Sometimes I forget you have those—instincts.

I wonder what called you to leave. Do you not love me? Is that why? Have I been a terrible owner, best friend, companion? Or do you find more homeliness in the darkness of the forest, under the slowly changing leaves?

Do you even know what home is?

As I roam the neighborhood, one of my neighbors—a boy in my class—walks up to me.

“Hey,” he says. “What is wrong with you?”

“Toby went missing,” I manage to say. I hand him a poster.

He rolls his eyes and laughs.

He leaves, pretends like I’m crazy. Suddenly I wonder if you even love me, or if you really are what Henry said. Just a dog. I find myself crying now for a different reason, because if you were just a dog, it makes sense that you would wander into the backyard, into the unknown, exposed to all elements. If you were more than that, you would have stayed. You would have looked at the open gate and turned away.

We find you later that night, snacking on a pile of dog treats we had left by the mailbox. I am relieved when I see your perfect little nose and smile, but the happiness quickly fades when I think about how you are just a dog.

I’m sixteen, and I hate boys (except for you). I’m crying on the edge of my bed, a box of tissues on my side table, and you jump up and nestle next to me. Your nose fits right in the crook of my elbow, and as my tears fall on your fur, I wonder why you’re doing this because all my life, you’ve been just a dog.

26

corners

lighted

I’m eighteen, and moving to college. In my little dorm room, I place a photo of you on my desk. Apparently, when I was six, I used to take your heartbeat (how silly of me?) and pretend I was your doctor. Anyway, that is the photo I chose to display of you, because you’re looking up at me in the kind of way that transcends everything people say about you being just a dog.

I’m nineteen. Mom notices blood on the floor—it’s yours.

You don’t eat or drink and you have a mass growing in your mouth, full of blood that drips everywhere. You spend the early days of December coiled in bed, hurting.

Mom says you’re suffering.

I take philosophy in college, and we learn that suffering reveals beauty. It’s an anguishing experience that makes you more human, except you’re not human. Does that mean that it’s all for nothing?

getting married and having children and grandchildren, after I’ve had more pets (none that will be like you, of course), and after I’ve grown old and gray, I will go onto the afterlife and you might not even be there, after all these years, because you were just a dog.

I wonder why your life begins and ends at a small strip of stores.

The veterinary clinic in our little town lies just before the main street. Mom, Dad, and I take you that evening to “put you down.” I hate that phrase. Like we’re killing you. Although, in a small way, we are.

You’re confused. You look up at me with those twinkly brown eyes, and suddenly I’m five again, and you’re my everything. But I’m twenty, and you’re dying. And I’m not. I’m far from it. You don’t know what’s happening, but you know something is different. You watch

For a while, we wait inside of this small room with no windows— just a medical examination table and a counter. We wait for so long that I think you’ve already died, that and suddenly, I’m five again, and you’re my everything.

That your suffering is natural, that God would allow it because that’s just the way things are? That your suffering is not even suffering, because you don’t have a soul?

That’s the thing that hurts me the most—I do not know if you have a soul. So when I die years and years from now, after I’ve lived a life of college and finding a career and

the sky change above you. You rest your head on my shoulder. It’s cold outside. No one talks as we walk into the clinic. It’s an unspoken sadness, lingering.

27 currents

we’ve died with you and that this is purgatory. But then the vet comes in. She says some kind words to us, then talks about the shot she’s going to inject into your body.

You’re terrified. You’re shaking next to me, your eyes darting back and forth. At the little girl who dressed you up in skirts. At the girl who held a stethoscope to your heart. At the girl who always cried, the girl who then left home every fall and spring, the girl who you ran to first.

Do you remember all of that?

In these last few moments of your life, I wonder if everything I believed about you was wrong, because you are so full of fear, of raw and human fear.

“He’s going to yelp a little,” says the vet, and then she combs through your gray-and-black fur until she finds the perfect spot, right next to your spine.

Then it’s in.

You let out the loudest, most gut-wrenching squeal, and I feel hurt by the amount of pain and shock you must be feeling. The sting of a sharply cold needle, the

eyes watching you from all angles. I begin to cry and it feels uncontrollable, sobs escaping my mouth as my vision blurs. I wipe away the tears, holding my hand to my mouth.

But then it only lasts long enough for you to hurt. The exhaustion of a fifteen-year-old life veils upon you as you turn limp and close your eyes, and I wonder if you’re going through that flashback that people experience before they die. I’m holding your paw, stroking your back. You’ve stopped shaking in fear, and I like to think that the pain is draining away, that a warm sensation of peace is overtaking your body, what once belonged to you.

I wish I had my stethoscope to listen to your heartbeat, to the thud, thud, to the sounds of my five-yearold laughter and your fierce barks. To the sound of your collar tags as you ran towards me. To your paws against hardwood floors.

Then to your final breath. To the piercing beat of silence. To the quiet cries in the windowless room.

28 lighted corners

then to your final breath. to the piercing beat of silence. to the quiet cries in the windowless room.

Waves of Emotion

Sarah King

The waves on the beach, their melodic hum— they remind me of things out of reach, of my dear Mommom, and how their crashes mist my cheek, and how the sun warms my skin. It takes me back to that day, so to speak, when the mist was tears running past my chin, and you were not there to give me a hug like you always had been there to do. But I stand in front of this rug of sand, embracing all that is blue, for now I have this happy-sad place where I can remember you and your embrace.

30 lighted corners

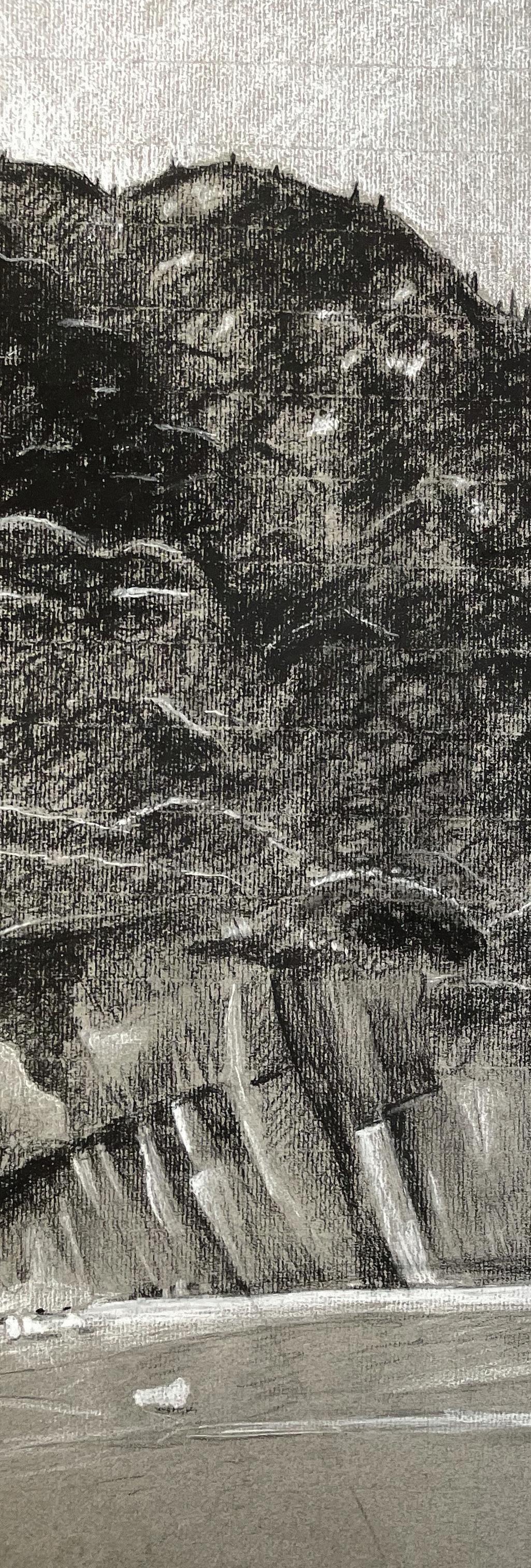

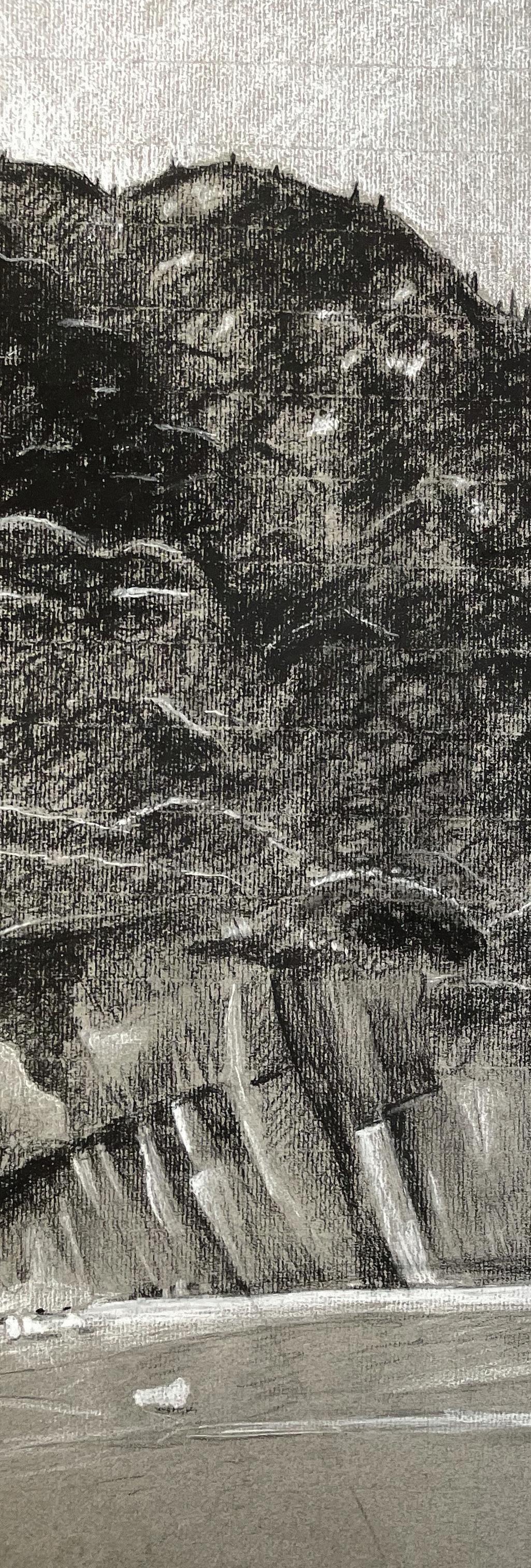

“Alaskan Seaside” by Alexandra Eastman Black and White Charcoal on Gray Paper

31 currents

Ode to the House with the Outgrown Peach Tree

Kiara Ramirez

Where a peach tree was born and flourished on the porch, a table of puzzles done every weekend, the daily paper being read; where the kitchen once smelled like sopa de frijoles y arroz, the telenovela in the background from the living room, where an old lady braids the little girl’s hair—

to the basement, where the little girl played in her plastic kitchen, the little crib where she put her baby to sleep; to the room upstairs, watching Thumbelina as she ate breakfast in bed, the little girl walking with her grandpa to his mechanic shop a few blocks over, where they spent most of their afternoons,

until it was sundown and they walked back home, to eat sopa de frijoles y arroz, to the house that no longer belongs to the little girl, the house where the peach tree no longer has peaches; the house she is losing memories of, cannot even recognize— the house the peach tree has outgrown.

by Dolores Hans Photography

33 currents

“Mist Opportunity”

You Cannot be Mine

Joshua Aybar

How can you be mine, you pretty little thing?

Your eyes are too precious, your smile too pure. You cannot be mine.

You pretty little thing, you cannot be mine. Your face is too hopeful, your laugh is happy. You did not get these from me.

So, you cannot be mine, unless I’ve forgotten a bygone age when my eyes felt wonder, when my smile never left, when my laughter was real, when I was like you.

34 lighted corners

Waterfront Beauty by Annabelle Colton Photography

“Called in a Dream” by Anna Dang Digital Art

Upon the Conquest of Coffee

Anna Dang

‘Twas morning light, 1683 of Jan Sobieski’s victory; and Christendom’s banner wav’d on high against the Turks retreating nigh. Their spoils rent all o’er the field, Vienna’s guard caus’d them to yield; but Jan, the king, in his long stride, soon chanç’d upon a tent offside. The soldiers there had gather’d true, murm’ring spite of some dark brew. “Away with it! the potion bred to fight all night with us,” they said. Jan Sobieski push’d through the crowd. “What cause so early your din so loud?”

corners

lighted

His soldiers bow’d, and to him conferr’d, “Your Majesty, we shall affirm: in Turkish lands, Ethiopia east, there grows a plant, the Nether’s beast. Our comrades in th’ bosom of Christ must each day slave for Ottoman heist, to harvest, grind, and blend these beans into a drink by th’ Devil unseen.

They call them kaffers, insult and drool, and name this ‘coffee’ for their suff’ring cruel.

How else it be, that they fight without end? Only this drink, by the Devil’s own hand.”

So, King Jan open’d that burlap sack and saw the powd’r of coffee beans cracked. How does it, then, have fragrant smell, when this curs’d growth comes straight from Hell? “No, no,” he said, “we cannot say. Instead, we’ll ask the pope and pray.”

currents

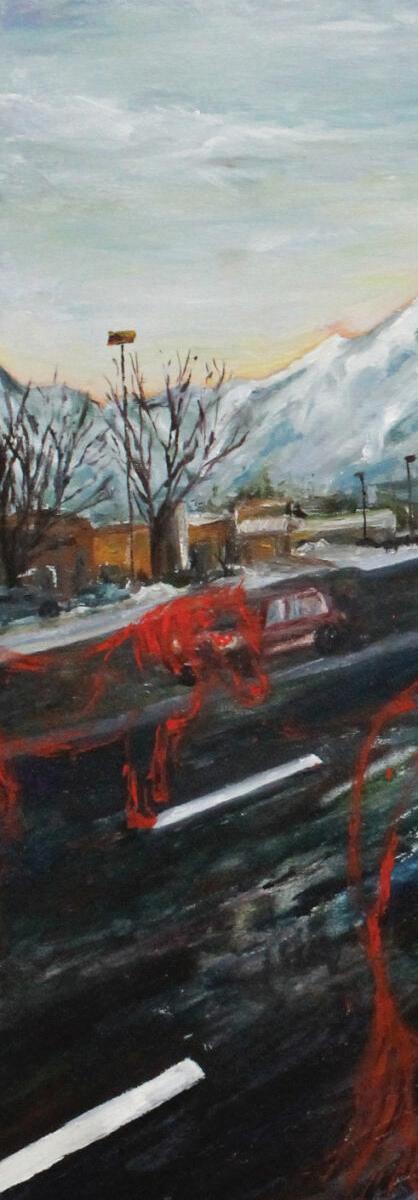

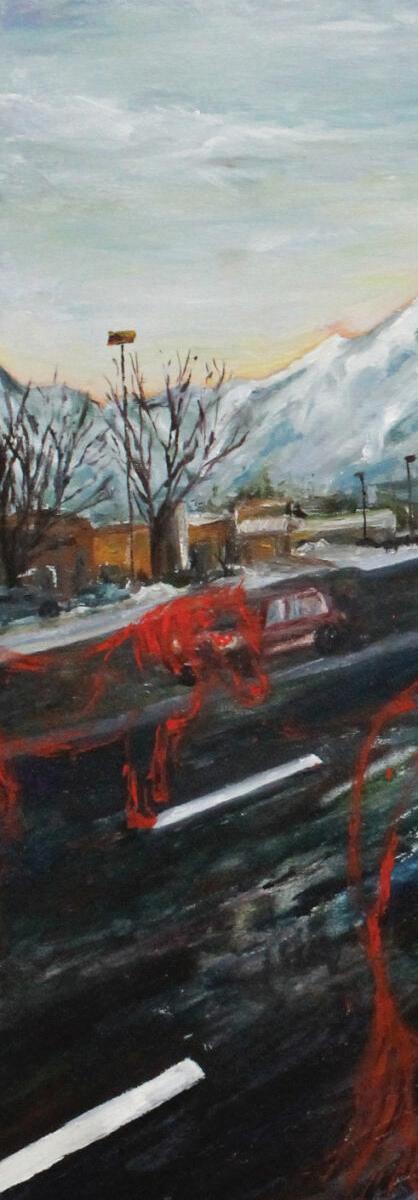

“Mountains” by Kevin Ryan Photography

To Rome he marched with th’ roast of death and yet still aw’d at its sweet scent. The ships soon dock’d on Italian shore, the load of coffee brought from store. The people turned away their sight in hateful fear of th’ Turkish blight.

King Jan persisted, and with his troops, he soon enter’d the Vatican’s coop.

Card’nals, Bishops, Monsignors all, majestic array’d in St. Peter’s hall.

‘Til ascending, upon the throne, Pope Clement sat and welcom’d Jan home. “Hail, King Jan, by th’ Madonna’s hand, Hero who ‘ath sav’d our Christian land. By grace of God, in Our Lady’s stay, What brings you back so soon this day?”

“Your Holiness, I beseech thee hear, to heed my request in Christ so dear.

The coffee I’ve brought, as thus we’ve known, has come from Turks, by Christians sown. The Devil’s Drink, ‘tis thus recall’d, but I’ve no pow’r to so outlaw.”

Card’nals and Bishops all lik’d the plan, but Clement calmly rais’d his hand.

“What is this strange query, King Jan? I must try first, before a ban.”

Then all the court was in disarray at Clement’s radical words that day. What was the Holy Father’s intent? ‘Twas Satan’s fruit—give no consent!

a cup was brew’d, the black drink pour’d,

“Then how shall we discern it well if Satan true brought them from Hell?

Let God be judge, but as His Magistrate I must discern of coffee’s state.”

A cup was brew’d, the black drink pour’d, its fragrance o’erflowing out the door.

Jan and the court, with bated breath, all watch’d him drink the roast of death.

For one moment did silence reign. For one moment, all was restrained. Then Clement’s eyes lit up like flares, and he rais’d the goblet and declar’d, “The Devil’s Drink is too good to waste! We’ll cheat him with baptism now, make haste! For infidel pow’r the Lord has slain, and as we’ve won, we’ll stake our claim. Card’nals! Bishops! Monsignors here, join me in Heav’nly joy so clear, to share a blessing o’er this cup, and to the Lord, we’ll offer up.

Now you, King Jan, O noble knight, ye who have sav’d us from our blight, go out and claim the spoils of war, and cut good Ethiopia’s cords. We shall take the coffee for our own, and save our brothers from Ottoman zones.”

And soon thereafter, in Rome so fair, by Clement’s verdict in the square, from hill and dale the folk came out to Europe’s very first coffeehouse.

its fragrance o’erflowing out the door.

Plays from My Diary

Tess Koerner

Tucked away in the back of my closet, my high school diary sat with your name amidst my poorly practiced cursive. You were listed on the first page, not in the expected role of lover, but in the role of classmate #2. The setting: a cramped English lit classroom. Cheap copies of A Tale of Two Cities and Pride and Prejudice lines the windowsill on the far wall with their spines cracked and brittle. Wooden desks with scribbled profanities on the inner corner are arranged in staggered rows to prevent us from chatting. Our names are written on the whiteboard next to characters from Macbeth. By Act II, I figured that you dreaded reading as Lady Macbeth, with your head buried in the ridiculously heavy textbook as you spoke. I perfected my best attempt at a gurgled English accent as one of the Witches to make you smile.

Page after page of each entry was you: the two months you experimented with berry red lipstick— which always smudged on your teeth by the time class got out—the book summaries you’d give me after wondering what you’d been reading before class, the classes where you let your curls fall naturally after weeks of straightening

them. Complaining about exams became talking about your favorite Harry Potter book. Inviting you to join my lunch table became seeing if you were free on Saturday. Pointing at the stars outside of your car became asking if you could kiss me.

From then on, the role of star-crossed lovers always fit us better.

40 lighted corners

“Catedral de Sevilla Spire” by Robert Prender Photography

“Catedral de Sevilla Spire” by Robert Prender Photography

Our walking tour of sights of the 1916 Rebellion was memorable for a single reason. Our tour guide, Lorcan Collins—a quippy fellow who knew his stuff but had an unfortunate knack for quoting bumper sticker logic—noticed my rings at the statue of Jim Larkin. They’re from Bosnia, I said, acting only half so thrilled as I felt that he’d noticed them and asked about them to boot. Bosnia, says he, I have a very good friend from Bosnia. A refugee, so she was. He then quickly glossed over a tale of the time he and his friend smuggled this Bosnian girl back into her country during the war because her mother was ill and without them, she wouldn’t have been allowed to return to Ireland. This was before 9/11, he said; it’s much different now. Now, they’d never get away with it but back then, they bribed

Abigail Jarrett

Abigail Jarrett

and charmed their entire way across Europe quite stoned. They only had a little trouble with “the fascists” in Croatia because they weren’t keen that their friend shouldn’t have a passport, but eventually their Irish charm prevailed, and they finally made it to Bosnia. He said he never really thought about the danger until years later. I guess the marijuana wore off. You know, I think I’ll give her a call, he said with a smile, and I was left to marvel at the size of the world and just how cool people can be, and wondering where in the world they get the balls for these stunts.

In Bosnia, I met people from all over the world—well, mostly Australians, because the flight anywhere is something like twenty-four hours—who up and travel to Europe for months at a time with only a backpack, their passports, and enough cash to keep them from starving. They have only the vaguest outline of a plan, and make the rest up as they go along. They hop trains and planes and buses with the ease of Rick Steves. They meet in hostels long enough to share an adventure, a smoke, and a recommendation before skipping along to the next city.

That kind of adventure used to seem like a dream to me, something I could never do but always wished I could. A dream which I would say to friends and family, “one day,

that’ll be me” and they believed me, but I didn’t really because it scared the hell out of me. In fact, before Ireland, I had come to the unpleasant realization that many of my dreams had gone unrealized and that maybe being an adult is accepting that they won’t.

It’s not true. It’s funny to think that I’m that person now—the person with half-buried memories of the places and scenarios I’ve stumbled into while half drunk, and stories prompted by spotting a pretty copper ring on a random girl’s finger bought in some faraway place. I tell my stories to gaping mouths, to oohs and ahs and laughter. I’ve done what my mother, my grandmother, and myself three months ago could only dream about. I hardly recognize myself.

“Fuinneog Bhinn Éadair” by Tess Koerner Photography

Fantastical Truth

The world is full of fantastical stories. Of fairies, dragons, and unicorns, friendship, betrayal, and love. Yet, have you ever heard of that story?

That fantasy story of a god and a mortal?

If you have not, let me tell you of a god who loved life back.

Annabelle Colton

He was a valiant one, the most triumphant of the skies, the most beautiful of them all, as strong as he was wise. But take heed and remember still, he was the one in whom love was fulfilled.

He loved a young woman, a mortal in tears and spat upon. Wondrously beautiful but daily she cried, for she was cursed to die.

And he desired that it were not so.

He rushed down from the sky to heal her, to proclaim his overflowing love for her. He suffered and died, purchasing immortality for her with his life.

The woman was freed of her deadly curse, her humiliation and ill fortune reversed. In magnificence, the god arose and triumphed over death, and the woman loved him back—he who gave her new life’s breath.

Have you ever heard of that story?

The story of a god and his beloved? Of the eternal love within his heart that radiates forevermore?

Indeed, the world is full of fantastical stories. Indeed, this is our fantastical story. This is our fantastical truth.

Morning Rosary by Emma Edwards Photography

“Saint Michael the Archangel”

by Anna Dang Watercolor Paint on Watercolor Paper

44 lighted corners

Abe and His Sushi and His Baskets

Abe Schuman stood at his window, scratching at his ankle monitor, returning his neighbor’s glare with a smirk. Gerald Snyder was taking a break from learning how to use the wheelchair lift in their new minivan. Little Jeanine had gone back inside, most likely embarrassed by her new chair.

Abe opened his window.

“Nice day isn’t it, Gerald?” he said.

Gerald continued to glare through his glasses, crumpling the instruction packet in his left hand.

“Really, a great day for a bike ride,” Abe said, now leaning on the windowsill, “and I know how you Snyders love your bikes.”

Gerald started to walk forward but turned when a voice called him inside his house.

“At least you could have fixed my car!” Abe yelled after him.

A Mercedes pulled into Abe’s driveway. It parked next to his front stairs, cockeyed in the empty lot. Out stepped a tall, lean-muscled man, his kippah held onto his loose brown curls by a large hand. His wedding ring reflected the sun into Abe’s eyes.

“Hello there, Abraham,” he said, brushing flecks of lint off his

Joshua Aybar

blue athletic-fit suit.

Abe shuffled from the window to the door, hastily scratching at his unruly beard and thinning hair. He slowed himself, took a breath, and cracked open the door.

“What, Isaac?” he said.

“I have the sushi you wanted. They were out of yellowtail, but they had white salmon, which I remembered is your second favorite if I’m not mistaken.” Isaac held up a brown paper carry-out bag.

“So, you actually don’t have the sushi I wanted, just some sushi I now have to eat to not be rude.”

“I mean, technically, you’re not incorrect, but I figured you’d want something.”

“The something I want is the thing you neglected to get. If I must, I will eat this, but only out of courtesy to you.”

“I appreciate it,” Isaac said as he walked through the door. Abe had opened just enough for his brother to squeeze through.

Abe shuffled around the house, quickly rinsing off two plates from the pile of dishes in the sink, not caring to dry them off or remove the stuck-on pieces of food. When he put the sushi on them, the soft pieces of fish stuck to the scraps, and each bite had a chunk of gunk

46 lighted corners

hidden on the bottom.

Abe watched his brother’s eyes as they wandered the room, eventually stopping on an old piece of woven fabric that had been stuck in a cabinet door to wedge it shut.

“Is that the kippah mom made for you?” Isaac asked.

“Hmm? Oh, that old thing?” Abe said. “Yeah, I guess it is. I had totally forgotten about it.”

“She loved you, you know.”

Abe shot up from his seat. “You know that’s a lie!” he said. “That bitch always loved you and despised me! She worshipped the ground you walked on, and she never gave me so much as a loving glance!”

“Abraham, relax.”

“Don’t call me that”

“It’s your name.”

“My name is Abe. If you can’t handle that, then get the fuck out.”

Abe just stared into Isaac’s eyes, waiting for a response. Isaac still remained seated, seemingly undisturbed by Abe’s outburst. He always did this.

Just give in, thought Abe. Come on you prick, just give in.

“I never understood why you do this, Abe,” said Isaac, between bites of sushi.

Abe continued to stare at his brother. No matter what Abe got good at, Isaac could always pick it up right away. He even used chopsticks better than Abe did, and Isaac didn’t even eat sushi that often.

“Fuck you.”

Isaac then stopped chewing. Slowly, he swallowed his bite.

“Abe, why?” he said, voice calm.

“Why can’t we just have a peaceful little meal? It’d be good for you.”

“Oh, oh, I see. You also know what’s good for me. Look at that, my lawyer brother also got his medical doctorate. Congratulations, Dr. Schuman!” Abe was hyperventilating. He stood across the table, drooling and glaring at Isaac.

“Abe—”

“Don’t ‘Abe’ me, you prick!” Abe was leaning on the table now.

“Just cool down. There’s no reason to be so hostile.”

Abe reached his hand out and grabbed Isaac’s plate, throwing it against the wall. He tried to speak, but rage choked him. All he could do was point angrily at the door.

Isaac put up his hands, stood up slowly, and walked to the door.

“I’m sorry to leave you like this, Abraham,” he said. Isaac stopped and turned, realizing his mistake. “Sorry, I meant—”

He was cut short by a plate crashing into his face. Abe had another one in his other hand, and he hit Isaac across the left side of the head, sending porcelain shards across the foyer. Isaac staggered. This was the first time Abe had ever gotten the jump on his brother. He followed the plate with punches. Abe poured years of jealousy and regret into each blow.

Two large palms simultaneously

47 currents

lighted corners

hit Abe in the chest. He stumbled backwards, fell onto his table, and rolled off into a pile of broken dishes and scattered raw fish. He

looked up at Isaac. Tears rushed to Abe’s eyes as he realized Isaac’s kippah had not even moved. Isaac looked down at Abe, who could see

“Good

Old Days”

by Caliann Dietz Photography

48

sadness in Isaac’s eyes. Isaac moved to help him up. Abe swatted the hand away.

“Get. The fuck. Out. Now,” he said. “You’ve done quite enough.”

Isaac sighed, brushed himself off, and turned to leave. Before he got out the door, he hesitated, half turning around, but he continued out the door, leaving Abe in a pile in the dining room.

Abe pulled himself to his knees and looked through the window to see Isaac leave. He tried to think of something clever with which to cut him, thus winning the fight, but nothing at all came to him. Isaac had beaten him again. There was no point in going against the norm. Abe flopped back down in the pile of destroyed sushi and cried himself to sleep.

When Abe awoke, it was dark outside. The clock said it was 11:00 p.m. He pulled himself to his feet and looked out his window.

Gerald Snyder was at his usual nightly post, drinking beer after beer in a lawn chair in his driveway, staring at Abe’s house. Abe waved two middle fingers in the window, making licking gestures with his tongue to match the disrespect of the fingers. As usual, Gerald just sat there, seething.

Abe, brushing the shards of porcelain out of his hair, pulled the chunks of sushi off his clothes. He went to the bathroom, brushed his teeth, and went to bed. He lied there for hours, staring at his ceiling. His thoughts wandered to his fight with Isaac.

49 currents

I had him, Abe thought. Why can’t I win? Even if I go at it with every advantage, he still beats me.

These thoughts repeated themselves over and over again, until Abe drifted to sleep.

His dreams carried him to his childhood. He and Isaac were about to run a race. Their mother counted down from three, and Abe ran when she said “two.” He shot ahead, and reached the halfway point across the yard before his mother was done counting. He saw the finish coming closer. Four more steps. Three more steps. Two. One. Then Isaac shot by him, finishing just ahead.

Their mother scooped Isaac up, congratulating him. Their father sat on the patio, shaking his head.

“You can’t cheat your way through life, Abraham,” he said. “The hard workers will always beat you.”

Abe woke up.

He found an outfit from a pile of grimy clothes in need of a wash. He walked into the kitchen and set about making eggs for breakfast. Something outside caught his eye. Abe went over the window and saw a new car in the Snyders’ driveway. It had rental agency stickers on the back windshield.

Gerald and a man that could only be Gerald’s brother, albeit heavily tattooed, far more muscular,

and sporting a buzzcut, walked outside and got luggage out of the trunk. Abe smiled and opened the window.

“Ah! It’s Tweedle-Dum and Tweedle-Dumber!” he said with laughter.

The Snyder brothers looked up. Gerald glared at Abe, but his brother leaned over and whispered something, and he went inside. Abe and the brother held eye contact for a moment, then the new Snyder smiled, waved, and followed Gerald inside. The smell of burning eggs pulled Abe away from the window.

The eggs had caught fire as Abe’s unclean pan had dripped grease into the burner. He ripped the pan from the stove, sending flaming eggs flying through the air. He ran around the kitchen, found a fire extinguisher, and sprayed the fire. After a moment, he was picking up eggs and wiping some of the white foam off of them. Abe had gotten used to eating food seasoned with fire extinguisher foam.

Abe took his plate over to his still messy table. The smell of raw fish left to sit out overnight filled the room. He put his plate down, then he went to the basement to get his basket weaving supplies. He was almost out, so he made a mental note to tell Isaac to pick up some willow strands from the craft store.

Abe had been working with straw recently, but he wanted to experiment with something stiffer.

50 lighted corners

He sat at the table, eating burnt, chemical-soaked eggs, and weaving his last straw basket. He had to work efficiently, as he did not have much straw left. He’d made the first few two large. This final basket took him three hours to make, but it was small. It was more of a straw purse than a straw basket. Abe finished his breakfast and took the basket to the basement to add to the pile of baskets he had been accumulating amongst the old furniture and keepsakes. There were eighteen baskets now, not counting this new addition. He threw it on the pile.

I need to clean this place out, he thought. Could make a good workshop if I get rid of all the broken shit.

Abe walked back upstairs. He sat down at the table in his still destroyed dining room. He thought about cleaning, but dismissed it. Instead, he stared out the window, watching a robin build its nest. The bird used a technique not dissimilar to his own basket weaving. Abe smiled when he saw she was using some of his discarded straw. As the robin finished her nest and flew away, Abe went outside to get a closer look. He was careful not to touch it, but he took pictures of it from every angle. He then went back inside and began sketching them out as basket designs.

Abe stayed at his table sketching for hours. He came up with

thirteen different design ideas, six of which were viable. It was dark when he stopped. He sat back and looked at his work, and a smile danced across his lips. It was amazing what a man could perfect when confined to his house.

Fuck you Isaac, Abe thought. You’ll never be creative enough to outdo my baskets. Take the rest, but I still got you on baskets.

Chuckling to himself, Abe went to bed. He glanced out the window, but didn’t care to engage the Snyder brothers sitting in their chairs drinking beers and staring at him. He didn’t think about the fight with Isaac, or the neighbors’ glares. Only baskets occupied his mind. Until he fell asleep.

Abe dreamed of his mother teaching him basket weaving. She told him he had talent like no one else she had seen, and that he was the only one in their family that cared to let her teach them. They laughed together, and she showed him new techniques.

Then his subconscious pulled him to that phone call. The one that brought the news of her death. Abe pretended not to care, but it broke him inside. They had had their differences, but they had also shared many little moments together. The day it happened, Abe stumbled out the door, dropping an empty whiskey bottle. The noonday sun beat down on him as Abe got in his car.

51 currents

corners instead, he stared out the window, watching a robin build its nest. . .

52

lighted

His kippah became a handkerchief for the sweat on his face. The key turned, and the car flew backwards.

CRUNCH!

Then came the screams. The scream of a little girl in pain. The screams of a mother and father in anguish. The scream of a man who didn’t know what to do anymore.

Eyes blurred, Abe looked into his rearview to see a mangled pink bike and a growing red puddle.

Abe shot awake, covered in a cold sweat. He wiped a tear from his left cheek and the beginning of another from his right eye.

“It’s not my fault,” Abe told the darkness.

After finding his composure, Abe stumbled to his kitchen for water. As he sipped his water, he looked out the window. The Snyders’ chairs were empty. He put down his empty cup and headed for bed, but stopped when he heard water running.

Goddammit, he thought. The hose again.

Abe walked out the back door, then everything went black.

He awoke in his basement. The air was hot, stuffy, and hazy. His head throbbed, and there was blood coming from a gash behind his left ear.

He was sweating profusely. Did I just sleepwalk down the wrong stairs? Abe thought. Why is the heat blaring like this?

Abe rose to his feet and started up the stairs. When he got to the door and tried to open it, it did not budge. He tried again, and again it didn’t move, as if it was being blocked. Abe leaned on the door for rest, and realized it was hot. Only then did he smell the raging grease fire.

He ran back down the stairs in time to see embers float down from the ceiling. They landed on the old wooden furniture, and some of them caught. Abe sprinted around the basement, beating out any fires he could, but the air only grew hotter and hazier. It was getting hard to breathe. He looked around and saw the fires reach his baskets. The pile became a bonfire, and it consumed the surrounding furniture. He backed away and began to pry open the three-inch basement window. When he removed the dirty pane, Abe could see out into the neighborhood. Fresh air reached his lungs. He looked out and saw the Snyders sitting in their driveway drinking beer. Now, however, for the first time in a long time, Gerald was grinning.

Abe didn’t bother to call for help.

53 currents

Milk

Sasha Shandrenko

In the cup I find moments curdle; time is not kind, never sound of mind, able to be left behind.

The cow is aphonic, but it'd say, Don't let what was once mine waste away. Sip the milk, for it won't stay— Good for now, but only for today.

Next Page: “Catedral de Sevilla”

by Robert Prender Photography

54 lighted corners

“Kira” by Aubrey Preske Oil Paint on Canvas

I Cry into My Bowl of Spaghetti

Tess Koerner

My salty tears make up for the salt I had forgot to sprinkle in the boiling water. It’s missing something— garlic, maybe? I continue to eat it anyway through my blurred vision, knowing that you’ve always hated my cooking as much as my tears. I’ve tried so hard to be the perfect little housewife for you: lay out your ironed suit before your drive to the office; make the coffee and eggs to your liking; follow your mother’s recipe for torcetti down to the dough’s double twist; scrub the spot I missed on the tiled kitchen floor with sweat dripping from my upper lip. But my cleaning was never spotless, and my cooking didn’t remind you of your mother’s.

On my birthday, you made me bake my own cake. It’s not your fault that your secretary forgot to pick one up. I was turning 30 and hadn’t given you what you truly wanted. It was the subject of most night’s arguments. You had wanted nothing more than for me to say I had already gotten the best birthday present I could’ve asked for. You wanted me to pull out the stick, with its two bright pink lines, smiling for your approval, and say the magic words: “We’re pregnant.”

“Onism” by Jenna Scalia Photography

With tears streaming down both of our faces, we would embrace each other until you held my face

58 lighted corners

in your hands and kissed my head ever so gently, as if I was our child. I would’ve finally been spotless in your eyes. Deep down I know that your love is contingent, conditional, subject to change. Whatever you want to call it, I’d always be striving

for perfection. But I can’t help myself from yearning for that love. No matter how ephemeral.

But instead, my 30th birthday ended with you saying the red velvet cake I made was dry. I guess my tears in the batter went untasted.

59 currents

Forest Trail

Sarah King

They told me walk only where they permit, the leaf-covered pathway; it will guide me if I find it.

I put too much faith in my own wit; I have lost my way today. They told me walk only where they permit.

I feel like crying as I sit, searching for God as I pray; it will guide me if I find it.

I remember the past when I was bit by this truth, and yet I still choose to disobey. They told me walk only where they permit.

With shadows creeping soon all will be unlit, how can I stay on the path in such disarray? It will guide me if I find it.

I think by now the truth has hit, I fear that in this forest I shall forever stay. They told me walk only where they permit. It will guide me if I find it.

“Balance”

by Robert Prender Photography

Invisible Strings

Kayla Jones

That car must have been under a tree, I think as a Toyota Corolla drives past me. Indeed, there seems to be more bird shit than blue paint covering it. I laugh softly and continue basking in the warm sunlight of the new spring. It’s the first decent day we’ve had in a while. Rather than staying cooped up in my office, I decided to take a stroll around the park across the street. The cool breeze runs teasing fingers across my skin, pushing my hair back from my face like the gentle caress of a faceless lover. The fresh air feels good after spending the morning in a small office with one window that faces the side of another building.

I’m not the only one enjoying the day: there are many people here, most of them with children who are probably too young to be in school. I see groups of teenagers, no doubt skipping whatever classes they’ve deemed unworthy of their precious, youthful time.

I sink down on a wooden bench. It’s painted a beautiful blue-gray and has a little golden plaque nailed to the back:

In memory of my darling Willow, who loved this bench.

I can see why Willow loved this bench. It has a perfect view of the park: trees just beginning to sprout leaf buds on the tips of their branches; the dog park where three small dogs chase a bigger one; the little playground teeming with children squealing and laughing. It’s even in a spot where the sun shines more than it hides behind the trees, which is what I enjoy most about this bench. When I sit, the wood is already warm, and I can tip my head back a little to let the sunlight kiss my cheeks.

This bench is also perfect for people-watching, something I always enjoyed doing with my mom in high school. Some days, when we were bored on a rainy Saturday, we would go to the mall, get some Chinese food from the food court, and just sit and watch the shoppers. We had a game where we would try to come up with stories about people. Sometimes it was easy to guess their stories; other times we made them outlandish. There was once a man with a very nice, trimmed, dark beard wearing a bright red dress.

Mom laughed, leaning over to say, “Emma, look. A crazy crossdresser seeking attention.”

“I actually saw a woman and a little girl wearing the exact same

61 currents

dress a few minutes ago,” I countered. “I bet the little girl wanted to match with her parents, and she’s got him wrapped around her little finger, so of course he obliged.”

Mom didn’t care much about my theory, though while she was looking for more “crazies,” I saw the man meet up with the woman and the girl, who was carrying a stuffed swallow bird, the U-shaped tail clutched in her tiny hands. The girl grinned and ran up to him, squealing in delight, and I smiled.

I then think about my own father, losing him when my parents divorced, then when he died. Although I had Mom, she was never a mother, at least the kind that loved me or spent time with me. She was a bully and she hurt my father. If she were here right now, she’d curse Willow for how hard this bench is.

Thoughts of the past are interrupted when a group of teenagers noisily comes this way. Two are on rollerblades, three on skateboards, and one on a bike. The biker has a speaker attached to the handlebars and is blasting music. I smile as I recognize the reggae band Iration. They’re all grinning and talking amongst themselves. As they pass, I catch a snippet of the boy nearest to me: “I’ve heard that human bodies can bounce six feet into the

“Morning Stroll”

by Alexandra Eastman Photography

62 lighted corners

63 currents

air when they hit the ground. Did hers bounce or was there, like, not enough altitude, not enough momentum and speed?”

my way to my car, I’ll be there in twenty.”

I stare after her, my hand resting on my stomach while the clickclick of her heels quickly drowns away. If that small snippet wasn’t enough birth control, I don’t know what is. I’ve never wanted kids, but hearing Miss Business Mom’s own dilemma has only solidified that further. Has she ever sat on a bench in the middle of a park and let the

has she ever sat on a bench in the middle of a park

A shudder racks through my body at the casualness with which he said it. With them zooming past and the music blasting, I’m unable to hear his friend’s reply; I’m not sure I even want to hear it. What I do hear is a woman walking in shiny black heels talking animatedly on the phone, her pencil skirt straining against her attempt at taking long strides. I admire the black and white blouse she wears, and the perfection of her hair, pulled up and out of her face in a very professional way. I wish I could pull off an outfit like that. She’s a businesswoman, that’s clear from the way she dresses, but her voice is also very commanding, belonging to someone used to giving orders and having them followed exactly as she wants them. Her eyes are wild with annoyance, heels click-clacking against the pavement.

“No, Karissa,” she snaps, and I realize that her tone is more irritated than animated. “You cannot glue the feathers to your sister.”

She pauses, letting Karissa speak. “No. Karissa, I swear to God—where is Nana? Rissa, give the phone to Nana—Mom? Lock her in her room—no, she’ll be fine. I’m on

warm sun kiss her skin on the first day of spring? She may not have done it in a while, may not even be thinking about how nice the weather is today, but the people she walks past certainly are.

An old couple, likely in their late seventies or early eighties, strolls with their soft, wrinkled hands clasped comfortably. When he catches her looking at him, he stops walking to press a loving kiss upon her brow. She leans into it like he’s the sun and she needs his warmth and strength, and my chest tightens at the ghost of someone’s loving lips on my own brow. I thought Ben and me would have made it as far as this couple here. I was so sure of it—of us. Maybe if I could just be a little more openminded about things, then I could fall asleep to his warm body and soft snoring instead of in a cold bed in an empty room.

64

corners

lighted

The old couple smiles warmly at me as they pass by. “I love your sweater,” the woman says to me. “The little birdies are adorable.”

Pride swells inside my chest like an inflated balloon as I look down at the sweater in question, the three swallow birds seeming to fly across my chest as I shift. “Oh, thank you. My grandmother made it for me for Christmas. We both really love birds.”

resuming his monologue of the beautiful world around them, and I marvel at how easy it is for people to reveal pieces of their own stories to complete strangers. That lady didn’t ask where I got the sweater, she merely complimented it; yet, I so easily surrendered that piece of my life to her. How often do I do that?

I can hear my mother scoffing at me from wherever her soul is:

and let the sun kiss her skin on the first day of spring?

She smiles sweetly, the corners of her bright, young eyes crinkling. “How lovely! Homemade gifts are always the best. My granddaughter just turned six, and she’s already starting to get into knitting and crocheting. Her father got into it when he was a young boy, too, and is teaching it to her. Right now, she’s—oh, what is Louise making again?”

“I believe she’s making gloves. She made us each a scarf last time,” he adds. “Nothing crazy, just a solid color.” He flashes a proud grin now. “Mine was a bright pink. She said it matched my ‘happy personality.’ I feel rather inclined to agree.”

A small laugh bubbles out of me at the image of Ben teaching kids how to play guitar or build complex things out of Legos. “That’s so adorable! Maybe someday I’ll see some of her stuff on Etsy.”

They continue on, the man

“A whiny over-sharer, that’s what you are. Someone who spills her life story to anyone who will listen. It’s a wonder you managed to snag Ben and keep him this long.”

Ben. The thought of him wipes away my mother. He is my greatest love. We’ve been together three years now and have never had any serious disagreements until now, and it’s my fault. He’s been staying with his brother across town for three weeks, and I’m still sitting on this bench. The sun arches over me.

A little girl runs past, her hair pulled into two high pigtails tied together with robin’s egg-blue ribbon. But suddenly I see the two small, straight lines on that white stick. As the girl shrieks with joy, I reel in the all-consuming fear that threatens to swallow me whole again. I felt it when I saw the two lines; it was like hearing I’ve been fired, or we’re being evicted. While I gasped with

65 currents

horror, Ben gasped with happiness, surely feeling like he’d just won the lottery.

Of course, I’m going to go through with the pregnancy, but— raising a child? Now that I must make the decision, I’m not sure I’m ready for that. I’ve barely begun my new job at The Swallow Magazine, and Ben is still fighting to start up his new music shop, but he’s having a hard time with getting people to know he’s here. When I showed him the test, my words nearly incoherent from the crying, he said to me, “It’ll be okay. We will be okay. And this baby will be okay.”

I only stared in shock. How could he possibly want to have a child right now? There is too much uncertainty in our lives. What if the music store doesn’t work out and he’s left unemployed, and we must rely on my measly paycheck? What if I lose my job, too? Or what if we can only rely on how much the

store can sell? And then there’s the issue with the horrible, dark world we live in. And how long would we stay in this rundown town? What is the best school district? What if I forget to pack the kid fruits and veggies in their lunch and the teachers start thinking I’m a bad mom?

What if my kid hates me?

I can’t even count how often I told my own mother that.

Yet, envy always stabs me in the heart when I see Ben’s parents together, laughing and hugging with no animosity between them. They have no idea how lucky they are— Ben has no idea how lucky he is.

A loud squeal catches my attention. A very tiny baby boy is walking awkwardly from a woman to a man. The man scoops the boy into his arms and tosses him into the air. He catches the baby and holds him close. “Dude, you did it! You just walked!”

The woman comes closer and kisses the man. “We have a child who can walk! Oh, God. We need to really baby proof the house now.”

“We’ll worry about that later. Right now, I think we need to celebrate!” He tosses the baby again, and the young boy shrieks with adorable baby giggles.

Once again, my hand rests on my stomach. I suppose Ben does have a point when he tells me I don’t have to be like my mother. I know how I wouldn’t want to treat my kids, and whatever my mom

66 lighted corners

would have done I’ll just—not do that. I’ll be supportive like my dad was. I won’t put them down for trying or forgetting. I’ll teach them how to read and write, teach them about birds. Ben will teach them all he knows about music and fishing and useless-but-entertaining movie trivia. My grandma will make them adorable little sweaters and maybe teach them how to knit and crochet their own scarves and gloves. And I can’t deny that a small part of me does want to start a family with Ben. And watching our kids take their first steps? Say their first words? See them smile when I tell them “I love you” as many times as it takes for them to never once doubt that their mother does, indeed, love them—

I know none of those people, yet the new parents and old couple make me feel—well, excited is not quite the right word, but certainly more optimistic than I have felt before. I wonder what story the people around are making up for me. Do they know I’m a pregnant woman who’s terrified of becoming a horrible mother like the one she had to grow up with? Or do they merely see a quiet, young woman going on a walk through the beautiful park?

Later when I get off work, as I walk to my car, I pull my phone from my purse and dial Ben’s number. Movement catches my eye. Turning, I watch as a bird leaps

from a branch hanging over my car. A swallow bird, I recognize from its tail, resembling the ends of a stingray egg sack. I stop walking and watch it fly away until Ben answers the phone, his voice pulling me from my daze.

“Hey.” It’s short and clipped, as if my call is the biggest thing bothering him. It probably is. I don’t blame him.

I finish the walk to my car and reach for the handle. “Hi, Benny. Can we talk when I get home—oh, God, damn it! What the hell?”

“What?” Worry fills his voice now. It’s been ages since I’ve heard anything but anger from him, and hearing the worry in his voice is like finally finding water after being stranded in the desert. “Are you okay?”

“Yeah,” I say with a sigh. “There’s bird shit on my car door handle, and I didn’t see it until I grabbed it.” My mother would be

67 currents

rolling her eyes and telling me how dumb I am for not paying more attention to my surroundings. But Ben—

“You—oh my God.” He starts laughing, and suddenly I’m drowning in the oasis I’ve stumbled upon. I haven’t heard his beautiful laugh in so long, so rich and deep and purely from the bottom of his stomach. So open and carefree. The laugh of someone who loves without

set it on the center console, cringing at the mess on my hands.

“You’re very—ditsy is a bit mean, but you can be spacey sometimes, especially when birds are involved. You lose yourself in a daydream, and it’s hard to get you to come back to me.”

The amusement in his voice fades. I sit back and look at the tree next to me and sigh. “Benny, I’m really sorry. What I’ve done to you

hearing the worry in his voice is like finally

hesitation, without guarding a fragile heart. “How did you not see it?”

I pin the phone between my ear and shoulder and go around to the passenger side door to get in that way, keeping the dirty one stretched far away so as not to get the goop on my clothes. I make sure to check all over the handle for bird poop. “I wasn’t paying attention! There was a swallow that flew—oh, shit. The swallow was sitting on the branch right above my car.” I tilt my head back. “The swallow is the one who did this!”

Benny laughs again, and I can’t help but laugh with him, shaking my head at the bird poop covering my fingers. “Em, I really—this is so on brand for you.”

“On brand? What? What do you mean!” I laugh again, grabbing a handful of napkins from the glove box. I put the phone on speaker and

is—it hasn’t been fair.”

“Em, no. I’m sorry. I’ve been pressuring you, and that isn’t right. It’s your body, your choice.”

“Yes—sort of. I think it should mostly be up to us. You and me. And I’ve thought a lot about it and about what I want.”

“You have?” There’s a small trace of apprehension laced through those two little words. A vice clamps painfully around my heart knowing it’s my fault he’s worried about my next words.

I rest my clean hand on my belly. I swear I can feel the little baby move, like someone tugging on an invisible string to make a small fluttering feeling like a bird testing out its new wings. “I don’t want this baby—” His breath hitches and I smile. “—Unless you swear it will be spoiled absolutely rotten with love.”

His silence drags on. I wait

68 lighted corners

patiently for him to mull over my words—then I yank the phone away when he starts cheering loudly. His voice gets distant, and I hear a faint thump-thump-thump like he’s jumping around. “Yes!” he yells. “I’m going to be a dad! A dad!”

Giggling, I finish wiping the shit off my hand. I better get used to this. I make a mental note to buy lots of gloves to wear for the next few years when I change diapers.

jostled a bit. “Emmy, baby, listen to me. Listen to me. You are not your mom. You are going to be the best mommy in the history of best mommies. Our child is going to adore you and look up to you and want to be just like you. You’re going to teach our baby how to recognize birds zipping by, I’m going to teach him how to play Led Zeppelin and Lynyrd Skynyrd.” I laugh again, using a clean napkin to dab at the

finding water after being stranded in the desert.

“Yes, Benny dear, you’re going to be a dad. You’re going to be the best dad ever. We’re going to dress up with him or her, we’re going to watch their first steps, we’re going to put pretty ribbons and bows in her hair. This baby will never doubt that we love him or her.”

There’s a shuffling sound on his end, like he’s just jumped back onto the bed and the phone is

tears falling down my face. “We got this, Emmy.”

I nod, feeling even from here his warm hands on my cheeks, his guitar string scars scrapping comfortingly against my skin. “We got this, Benny.”

69 currents

Pearls, Rejected

Jane Allman

Her words were hollow and bordered with lace. I revealed my pearls, through her squints and big blinks. She hasn’t the courage to encounter my true face.

Before I confessed, I considered our place: a Catholic retreat, at nighttime by two shared sinks. Her words were hollow and bordered with lace.

I thought that treasure would slow our rash pace, but those sentences compelled her calling jinx. She hasn’t the courage to encounter my true face.

My pearls she advised me that night to efface; bastard beads of amoral, dangerous links. Her words were hollow and bordered with lace.

Months passed and she had luxury of taking new taste, her tongue loosened by aleberry drinks. She hasn’t the courage to encounter my true face.

Today she claims she had always preached grace, but I remember the night she made me shrink. Her words were hollow and bordered with lace; she hasn’t the courage to encounter my true face.

by Tess Koerner Photography

by Tess Koerner Photography

70 lighted corners

“Cornucopia”

71 currents

“Rights” by Kaitlynn Lowman Photography

“Rights” by Kaitlynn Lowman Photography

My Hair and Me

Rayelle Weir

The hair that sits on top of my head sometimes falls down my back and other times at the nape of my neck, shrinkage. A thousand and one black, curly follicles that cover the whole twenty-three-inch circumference that is the dome of my head. For all the hair that rests on this scalp of mine, I understand the heartburn my mother faced when she was creating me. From the time I was a one-year-old, or maybe even younger, my mother has been taming the beast that resides up top. It was as if she was preparing for battle when it came to wash-day Sundays, a dozen rat-tail combs snapped all over the carpets of our house, dryers lying in disarray as if they are almost seeing the light, and empty containers of Blue Magic hair grease all over as if they were bombs dropped. It could be seen as comical, if my tender-headedness didn’t make me cry during every style change. Despite the fact, my mother’s calloused hands have always been taming the beast, and there wasn’t a weekend where they weren’t. Until I decided to put an end to it.

I was in the fourth grade when I decided to take on the responsibility of doing my hair. This is also when I started to develop a hatred for it, too.

It was the week of picture day, and not only did we have to take class pictures, but we also had to do individual portraits. For this occasion, I asked my mother to straighten my hair, despite her wanting to style it differently. It was spring, the grass was a bright shade of emerald green and the clear blue sky that rested above me gave the sun full access to release an overwhelming amount of heat into the atmosphere. My class’s pictures were set for after lunch, and recess was around 1:15 p.m., while my portraits were set for 1:35 p.m. This meant that I had twenty minutes to keep my hair as intact as possible before standing in front of a flashing camera. Knowing this, I decided that I wouldn’t participate in recess, and the sweat-filled festivities that came along with running up and down outside. Instead, I sat outside in a pocket of shade, gifted by the sharply constructed corners of the school building, but even the humidity found me.

Just when the silver whistle screamed the end of recess, I entered the building and made a strategic beeline for the nearest bathroom. Neglecting the blast of cool air, I turned to face the set of mirrors that rested on the wall across the sinks. I stared at the reflection in the mirror, almost

73 currents

screaming, because who I saw was not me. The person in the mirror shared the same clothes as I did, even went as far as copying my glasses, but the hair that rested on her head was not mine. My once tail-bone hot combed hair was no longer silky straight and flowing flawlessly down my back. Instead, it was a frizzy mess that rested just barely in the middle of my back. As I stared at that the monstrous sight, I couldn’t help but to let out a shaky breath. I even went as far as running my fingers through it to see if that would be of use. Instead, my fingers got stuck. Eyes watering and lips quivering, I knew that picture day was over. I left the bathroom, no longer feeling the cold air while making my way to my classroom. Before entering, I grabbed my hoodie from my locker and put it on.

I was in the fourth grade when I decided

Ruckus from inside seeped out into the hallways as the doors began to open. Students were either talking, running, or simply not paying attention, all while teachers yelled in an attempt to regain a sliver of order. My teacher guided our class towards our designated area, which was two groups away from being next. Seated in the backrow, I waited, watching and sulking, and then suddenly heard the clicking and clacking of my teachers’ heels. Turning my attention away from nothing in particular, I watched as my teacher made her way over to me.

Walking into the classroom, I found my way to my seat with my head down and fingers fiddling together, anxious about what was underneath my hood. Once my teacher noticed we were all in our seats and ready to go, she lined us up in alphabetical order. I walked to the back of line, thankful that my last name began with “W” so no one could question my change in mood. Our journey to the cafeteria was quiet and almost too quick.

She was a tall, dark-skinned lady sporting a hot pink pantsuit paired with sparkling 6-inch heels. Her current hairstyle of the month were box braids wrapped in a tight low bun. Reaching where I was, she took the open seat that was to my right and scanned my appearance from head to toe, stopping at the hood that covered my head.

“What’s the matter?” she asked, her tone laced with concern. She sat there, waiting for a response that never came. I looked down at my feet and slowly started to peel the covering from my head. Removing the hood, I glanced up and she looked back at me with sympathetic eyes. Releasing a sigh, she said nothing and took my hands,

74

corners

lighted