The motif of family is one held universally sacred. It has complex meaning in every culture throughout generations, holds power in ways that are both overt and subversive.

Family is tied to our history, our foundations…a controversial and centralized, much sought after ideology/theory/theology in our current era…and is an ever shifting tide and ongoing legacy of our future.

Family is complicated… sometimes a feared, activating source of pain and trauma… it can be healing, a sanctuary…it is both nuclear and sometimes, more significantly, chosen and covenantal.

Extended and ongoing, exclusive and protected.

A closet of secrets, a mirror maze, a circus.

A well of warmth, honored and treasured, nostalgic, desired, and yearned for. It’s formative in its presence, especially in its absence. It’s a comedy, a mess, a tragedy, a drama, and ultimately, a most beautiful pillar and cornerstone of humanity.

Just in case anyone was wondering…

*motif: Sketchbook strives to be a safe and honest gathering of any/all authentic creative expression — from the seeds of ideas to the fully blossomed. It does not represent the views of Evergreen Baptist Church of LA.

January Lim | Editor | Photographer | Writer | Artist | Video Editor

Mide Kolawole | Co-Editor | Writer

Eric Lui | Project Manager | Writer

Daniel Lee | Project Manager

Arthur Au | Writer

Kennah Brydon | Writer

Randi Brydon | Writer

Lovelyn Chang | Writer

Abby Chen | Guest Artist

Ellory Chien | Writer | Artist

Bruce Chow | Writer | Photographer

Melanie Mar Chow | Writer

Kevin Doi | Featured Writer

Kobi Doi | Zine Artist

Alex Eng | Artist

Wendy Lew Go | Writer | Artist

Julia Hendrickson | Artist

Abby Kim | Writer

Julie Kim | Writer

Brianna Kinsman | Writer

Jang Lee | Artist | Writer

Layout Design by Isabel Bortagaray | isabortagaray

Soo Ho Lee | Writer

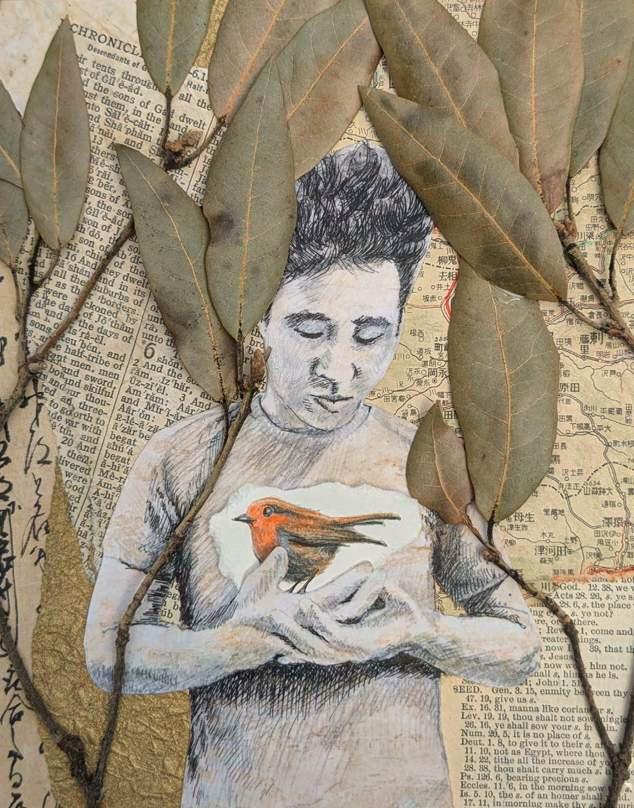

Eric Lige | Featured Artist

Lauren Meares | Voice Actor | Music Composer

Jon Moy | Writer

Janette Ok | Featured Writer

Maya Olson | Photo Editor

Julie Ono | Writer

Nicola Patton | Writer

Quincy Sakai | Artist

Alex Shippee | Writer

Marian Sunabe | Writer | Artist

Eric Tai | Artist

The Open Door | Featured Art

Mitch Valine | Writer

Mika Walton | Guest Contributor

Joel Yoshonis | Voice Actor | Audio Engineer

Liz Yoshonis | Voice Actor

| Alex Eng

The Cat | Quincy Sakai

Tangerines | Eric Tai

The Magpie and the Tiger II | Jang Lee

Sowing. Heritage | Brianna Kinsman

Surfaceline | Brianna Kinsman | Artwork by Eric Tai

Circles | Abby Kim | Artwork by Eric Tai

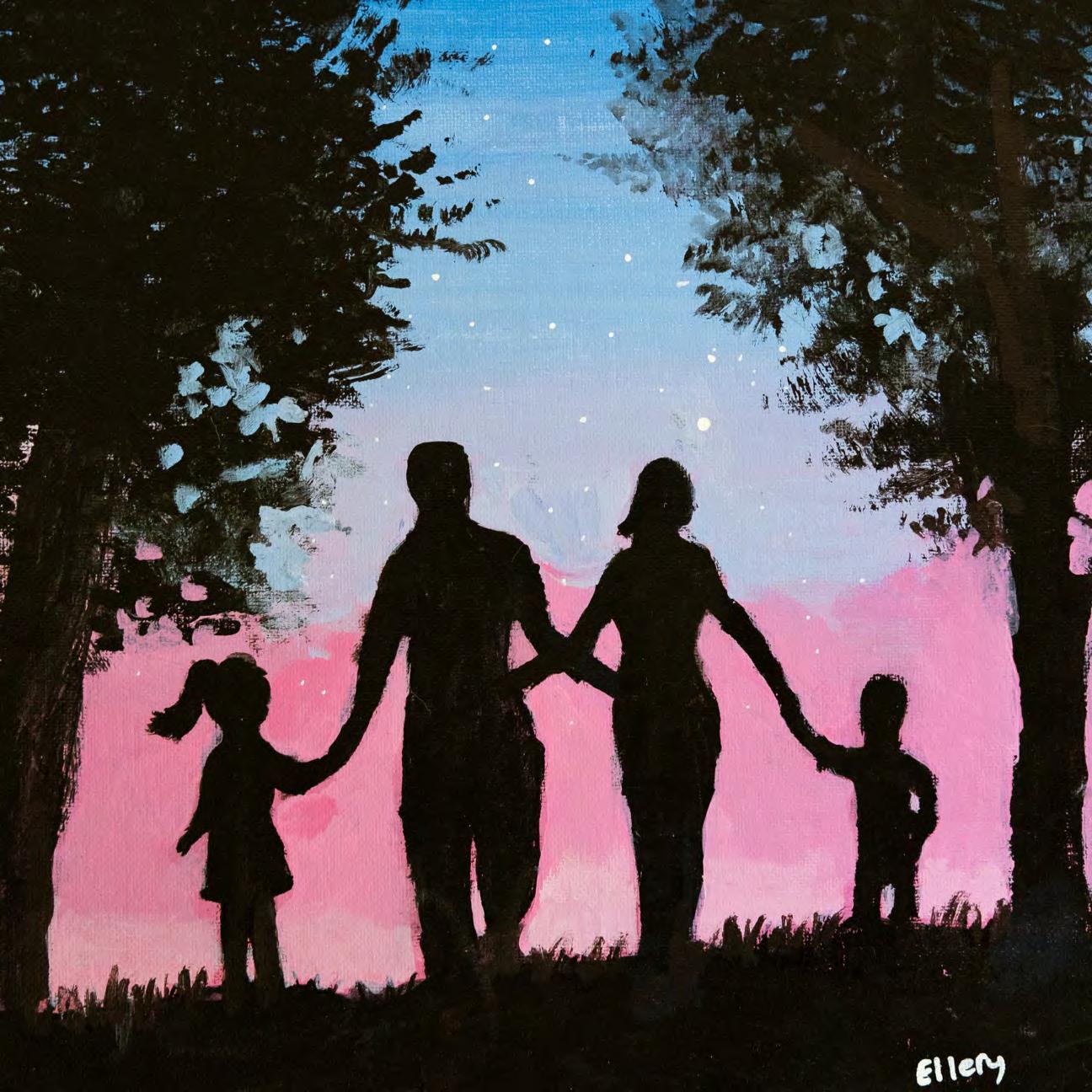

Family | Ellery Chien

Chosen | Wendy Lew Go

Wish Fish Family | Wendy Lew Go

Eaton Tabiji Eggshells | Released Me | Wendy Lew Go My Grandpa isn't Dead | Jang Lee

Gillian & Bernard Garcia | Written by Eric Lui & January Lim

A Conversation with Eric Lige | An Interview with January Lim

Telling Time | Julie Kim

Filling in the Blanks | Julie Kim

Regrets| Soo Ho Lee | Artwork by Abby Chen

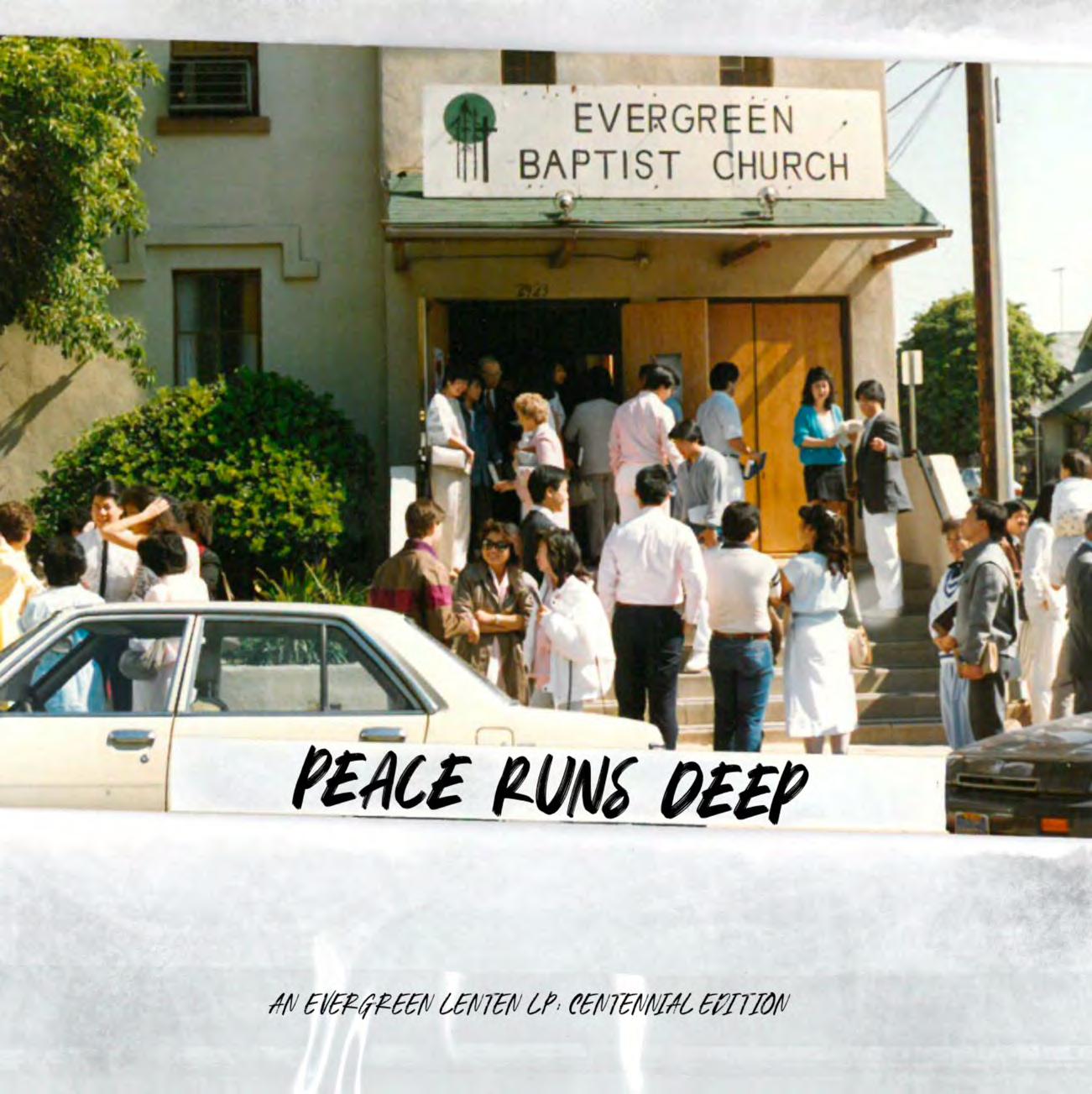

Peace Runs Deep | Art by January Lim

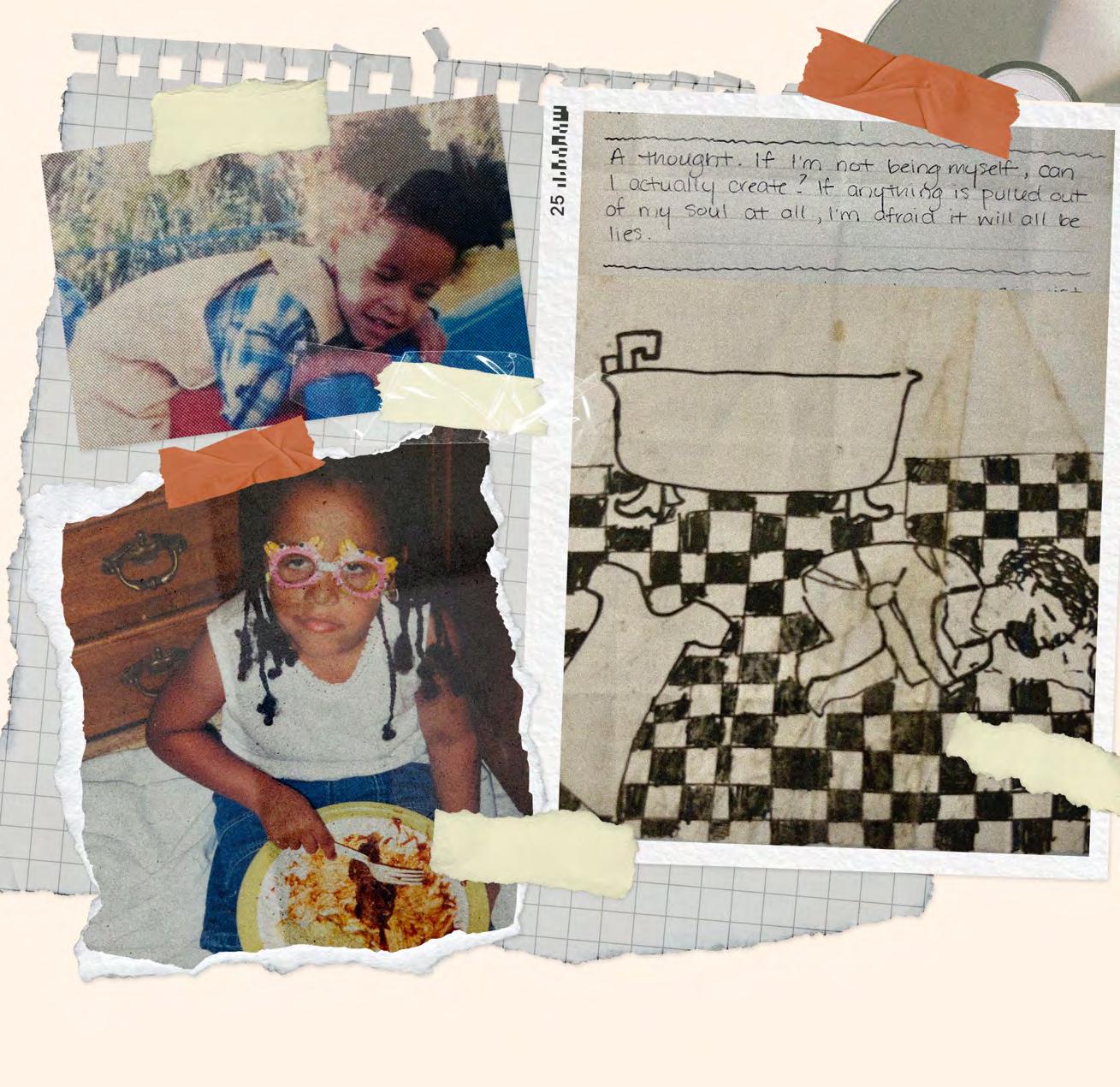

Snapshots of My Life | Kennah Brydon

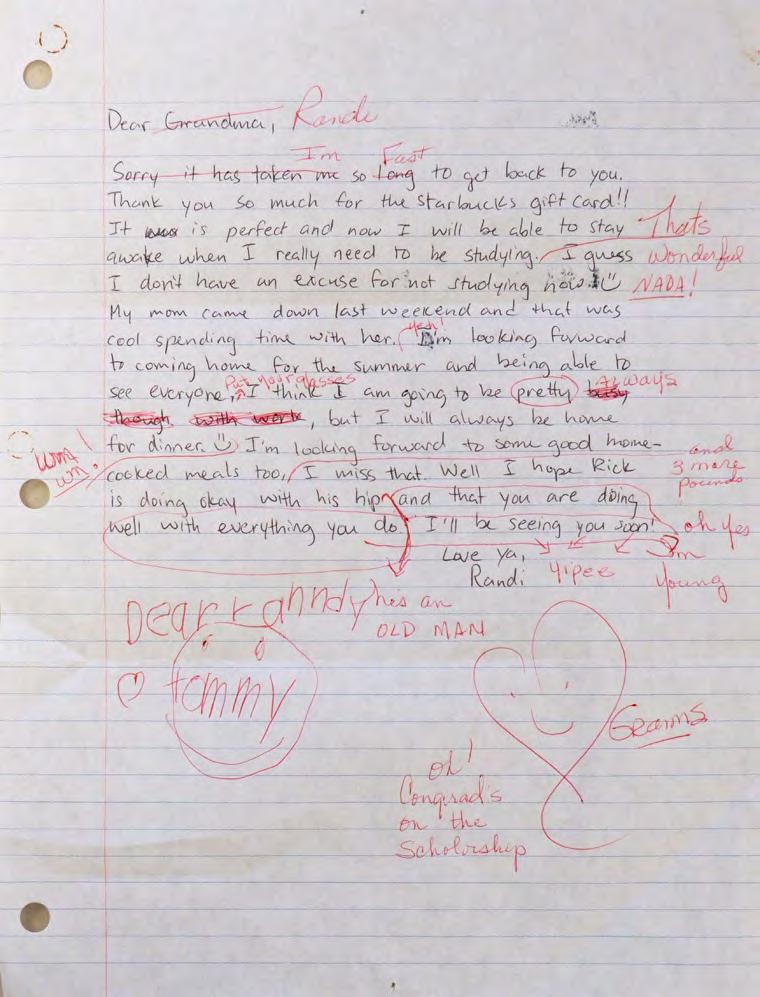

Dear Grandma | Randi Brydon

Chosen Family | Arthur Au

Journal Entries | Mide Kolawole

Of Sons and Farmers | Alex Shippee

Coming Home Again | Marian Sunabe | Artwork by Kenji Ono

The Convenantal Family| Nicola Patton | Artwork by Jang Lee

An Asian American Interpretation of Luke 14:25-33 | Janette H. Ok

Redeeming out cloud of Witnesses | Kevin Doi

| Artwork by Marian Sunabe

Altadena Strong| January Lim

Poppies & Peas: Milka's Orchard | Mika Walton

Photos by January Lim

Kings and Chronicles| Jon Moy

Conversations with a Child | Lovelyn Chang

Artwork by Quincy Sakai

“Ohana means family, nobody gets left behind or forgotten.”

Melanie Mar Chow | Artwork by January Lim

Siblings | Julie Ono

Ebí | Mide Kolawole

We'll Talk Soon | Kobi Doi

Saying Goodbye to Dad | Bruce Chow

Wild Geese | Mitch Valine | Artwork by Quincy Sakai

By Abby Chen

This piece was inspired by an Instagram reel I saw a while back—I tried finding it again but couldn’t. It made me think about how most Chinese parents show love in indirect ways, and how that shaped how I express love too. Recently I’ve been struggling with mental health in college, and my parents flew from LA to the East Coast multiple times just to check on me. Only now do I really see how much they care. This work is about that realization—about their quiet love and the time I didn’t fully appreciate until it was all I needed.

I wanted to visually represent how family should look like. I had a couple ideas, but I settled on representing how a parent would protect their child. When I was little, any time I felt scared I'd usually just go to my mom or dad. I felt safe around them because it felt like there was a sort of assurance that they'd be able to protect me. In this piece, the dove is protecting her children from some sort of evil, represented by the black bird in the back.

By Alex Eng

By Eric Tai

By Jang Lee

The Magpie and the Tiger II is part of a series which draws inspiration from Hojak-do a traditional genre of Korean painting which features a magpie and tiger. In Korean folk tale, the magpie outwits the stronger tiger, contrasting the outward appearance of power with underlying cunningness.

Inspired by the "doubleness" of the magpie, each element in this piece implicitly challenges and compliments the other—a testament to the dichotomies and contradictions that shape my own histories.

By Brianna Kinsman

In some future history, I am the woman with hair the color of the moon spilling over the rim of her shoulders.

the woman barefoot in the carrot patch who is most at home digging her toes into humus carpets, as if she too were made of root and earth.

the woman teaching children the uses of mushrooms and nettle, letting them to teach her how to grow wildly again, as we all start out, like the coiling watermelon vines that love to climb anything they can reach.

but today, I am the granddaughter with hair the color of soil tied above her shoulders, learning from moon-haired women when to harvest mushrooms, and how nettle leaf can heal, and where to plot the carrot patch, and curling my fingers around things just out of reach.

I am — the daughter, and granddaughter, and great-grandaughter of folks who know the touch of the earth — inheritor of growing things.

By Brianna Kinsman Artwork by Eric Tai

the thin line of your half-smile reaches across the table challenging me to cross it

but I’m not the one being tested turn over your paper begin the exam: count our conversations — the ones we never had

add up the things that no one said and the silences that said everything

the past we cannot speak of multiplies into the present

what happened in those first days? do you remember the maple roots that were footpaths? the quiet October rain? the Sundays drunk with cartons of chocolate milk?

you killed a snake once finding it tangled and tired in the garden netting I imagined you felt regret

you dug the hole where we buried Blaze you stayed beside me let me be sad and silent in the woods behind the house

you cried for the first time in my memory when you dropped me off at college you talk more now and so do I

recover your courage as you draw the rising waterline over your head as you sink into the new equation

then find me in the depths— fearfully move your fingers over my face trace my outline on purpose

balance the proof but erase some things too

I’ll let us forget so we can resurrect who we want to be

By Abby Kim Artwork by Eric Tai

Connected and continuous

Protected, bound by space and time

A pattern, a rhythm

That holds us together in sacred breath of life

Sometimes harmonious and whole

Sometimes bent and stretched

A circulation of codependence

A revolution of history

A cycle of trauma

A series of stories formed into legacies.

Sometimes our circles may be broken

Bruised and battered, hostile and hurt

Shunned and shattered

Unable to mend themselves into a whole again

But broken circles can be reformed,

Redeemed and reshaped into something new, alive

A shape of connection

Strong enough to stand against the test of time.

One circle may grow, while another shrinks

Our circles may overlap, finding links

Between our boundaries

Between our differences and commonalities

Between the vulnerabilities of our fragile humanity.

Our circles of connection

Show who we are

Whether they are given, found, treasured, pursued

Or rejected, lost, buried, disowned

Our circles of family bind us to our identity

Our circles tell our individual and collective story.

By Ellery Chien

Family is your roots the ones to give your name,life without them would never be the same. Family is a hug a hug that never fades Family is your treasure Care for them like jades when you need help or don't know what to do Family will help and stick with you like glue. Stories are shared connections are made love and laughter will never ever fade. family is the place where your story starts family is always close heart to heart Family grows and it shows from the love the care and the kindness that is family.

By Wendy Lew Go

beyond the blood box that did what it knew so caged by its own baggage trajectory doomed to seed damage throughout generations

absent all we longed for our lingering lament wanders smoldering lands of heartache memories sharp and cutting stitched into our being without consent we cannot tear them out

where do we belong?

surely there are someones gathering somewhere bearing bright threads of connection creating a warmth of family beautifully sewn with ripped and raw edges

honest stories speak unafraid mending together celebrating together woven by the One who chose us long before we chose each other we are family beyond the blood box we belong

beloved by One whose door opens wide to a house of welcome home for all.

This school of Wish Fish are reimagined from my many old paintings. What we may think is the end (a finished painting) is not necessarily so! It's simply raw material for what will be next. By releasing what no longer serves, and keeping what wants to be brought forward, we can reimagine, partnering with God in making all things new. This newness includes our families, whether by birth or by choice, differences and all. Wishing you the love and belonging found in the very best reimagining of family.

Media: Old art, scanned and digitally collaged.

©2025 Wendy Lew Toda W i S h F I s H F a m I l y

The Eaton Tabiji Eggshells were created in the aftermath of the Los Angeles fires, to express the devastation that seemed to be everywhere, much of which still remains. They are a prayer of stubborn hope, the blues and greens speaking of new life emerging right in the middle of all that has been reduced to ashes. When family relationships break and burn, we find ourselves in a similar devastation. Forgiveness can feel impossible, yet if we lean into that gift, layer by slow layer, over time something beautiful can grow, in the same way a pearl forms around a hurtful grain of sand.

Media: Eggshells, charcoal powder, acrylics, pearl, tears ©2025 Wendy Lew Toda

By Wendy Lew Go

Frosty daughter was I till the challenge to forgive pinned me with unblinking kindness hot war in my head commenced the clock held its breath turning ever deeper shades of blue awaiting the outcome I surrendered

Forgiveness won opening decades of a slow turning softening into unfamiliar freedom to love you I would forgive you all over again sometimes I still do, like yesterday when you kept grabbing the wheel of my life you haven't changed but I have happy in my own lane free to release you to be you instead of the Dad I thought you should be no more wanting what cannot be given it was never given to you, so how could you know?

By Jang Lee

aching hips, stuttering hips

histories peering under damp shingles, moss: slick, glistening. It was always there.

Yesterday, I found last week's histories: in a cage, screaming. with aching hips, stuttering hips.

histories peeled off my body like tangerine skin (slick, glistening), & piled between liminal steps outside my home

By Jang Lee

when mother gave birth to i’m twelve again & this me she forgot to give birth time my screams to my mouth & it burrowed kill my screams drip like into the walls of her soft vermillion tipped fingers laced butter stomach (lightly salted, around vocal chords & organic, pasture-fed). it squeeze! this time my screamed greyscale screams mother gave birth to my & gastric acid screams but mouth exploded in ears she why didn’t you hear me? shrills wished had not been born. plow into her ears, voice tears open until cherries decrescendo until hungry wished they could be crimson no more but what’s beneath like me & inside is pretty the plastic of an antiseptic possibility, a carcass. voice?

Written by Eric Lui & January Lim

The partnership of Gillian and Bernard Garcia—from their first meeting in the Philippines, to their lives as married seminarian students in Pasadena, California—has been nothing short of an amazing collaboration. Together, the Garcias have sought to host others through empathy, gather the collective needs of their community, and minister to any and all who feel lost and alone.

Gillian Eliza Colcol-Garcia was born and raised in the Philippines where she spent her childhood in the capital of Manila. She fondly describes the Philippines as a “gateway to Asia. It’s a melting pot of cultures! Honestly, the capital is kinda like LA;

whatever you have here, they have it there, thanks to American media and neocolonialism. [Except] the traffic is ten times worse haha! One thing I loved about growing up in the Philippines was the sense of community. We’re all a [part of a] collective in the motherland, and you are taught about the value of hospitality and mutuality [from] a young age.”

“OnethingIlovedaboutgrowing upinthePhilippineswasthe senseofcommunity.”

Gillian’s nuclear family is composed of her parents, older brother of ten years, and her younger sister. Her father has worked as a professor and dean at a university in the Philippines and her mother has extensive work experience in community development. Gillian remembers her parents as always supportive of her and her siblings. When asked about a family member who has majorly influenced her life, Gillian mentions her grandfather, Daniel Colcol, who was one of the 250,000 Filipino men recruited by the USA to join its army during WWII with a promise of US citizenship. He later spent decades fighting to claim the benefits that the US government had promised him and his fellow Filipino soldiers.

“My lolo thought that he was some sort of a shaman…when I was born, he did this little ritual and prophesied over me.” Her parents do not remember exactly what he said but they did mention that he saw “stars on [her] head.” Her grandfather’s vision has always provided Gillian with comfort and confidence. “My lolo inspires me to be resilient; I hope I am making him proud [through] my endeavors.”

Gillian is a graduating Masters of Divinity student at Fuller Theological Seminary where she also works as the Program Coordinator of Fuller’s Asian American Center. Since 2024, Gillian has also been serving as a pastoral intern at Evergreen

“Myloloinspiresmetobe resilient;IhopeIammaking himproud[through]my endeavors.”

Baptist Church of Los Angeles—the church’s first intern since before the COVID pandemic. Working with the Youth and Children’s Ministry, Gillian can be seen hanging out with teens or running around with (sometimes chasing after) the toddlers Sunday mornings.

Gillian’s husband, Raoul Bernard Garcia is a 1.5-generation Filipino American. Bernard was born in the Philippines but migrated to the US in 1991 where he was raised in the San Gabriel Valley, namely Azusa and Glendora.

Growing up as a Filipino American was not necessarily always pleasant.

“As part of a working-class immigrant family,” Bernard remembers, “I felt ‘other’-ized in both areas [of my ethnicity]. At the time, Azusa was under-resourced and over-policed, which contributed to the racial tension prevalent in the city. One incident I experienced involved being physically attacked by a local gang while I was playing basketball with friends. Being one of the few minoritized students at Glendora High— which included being called racial slurs on my first day at the school—my experiences further reinforced this sense of otherness.”

As Bernard and his three siblings were raised by his mother, Bernadette, he looks to her as a profoundly influential figure in his life. She migrated to the US from the Philippines, seeking a better life her four children. Bernard recalls that “prior to remarrying, she was a single mother who took on three jobs simply to survive and make ends meet. My mom worked simultaneously as a sales associate for a 99-cent store, a care-

taker for the elderly, and a receptionist at a garments firm. Her sacrifice and dedication have made a lasting impact on me.” Like Gillian, Bernard is also a student at Fuller Seminary, pursuing his MDiv degree. In addition to his academic pursuits, Bernard works as a data analyst for the International Justice Mission.

The Garcias have been happily married for 6 years and currently reside in Azusa. They first met in Manila when Bernard moved there to pursue an internship with an NGO. After over a year of living in Manila, a mutual friend introduced Bernard to Gillian.

“Upon our initial introduction,” Bernard explains, “the mutual friend said, ‘I’ve been wanting to introduce you two because I thought you would be so perfect for each other.’ Feeling embarrassed, I apologized to Gillian, expressing how awkward this was. Our friend tried to salvage the conversation by pivoting from a potential romantic interest to setting up a meeting for a possible organizational partnership.” Putting awkwardness aside, Gillian and Bernard grabbed coffee the following week during which he gave her a presentation of his work—and the rest is history. That must have been one hell of a presentation!

When asked about her side of the story, Gillian keeps it simple and sweet. “Bernard and I were set up by a mutual friend just a month before he was set to go back to LA. I guess I was such a gem that he decided to stay so he could date me.” She claims she is kidding, but we suspect this is closer to the truth than not.

“Wevaluemutualityin our marriage, we care about the same issues, and we consider our partnershipasministry.”

As a couple, Gillian and Bernard are passionate about getting involved in grassroots Filipino American community organizing groups. Their pursuits have included meeting with Rep. Judy Chu, lobbying to gain her support for the Philippine Human Rights Act volunteering in the recovery efforts for the California wildfires, and informing Filipino migrant communities of their rights as workers to avoid exploitation by their employers.

The couple’s love for the wellness of the collective is also a major driving force in their relationship to the Church. Church ministry has always been a focal point for the Garcias’ partnership. Gillian explains that “it was at my childhood church

[that] we were introduced to each other, and as newlyweds, we served as co-pastors at another church community. One of the things that I love about Bernard is that he is very supportive of me. He pushes me to be the best version of myself and comforts me when I’m down. And I do the same for him. We value mutuality in our marriage, we care about the same issues, and we consider our partnership as ministry.”

This collaborative dynamic of mutuality seems to infuse both Gillian and Bernard’s definition of family and church. “I would define family as not only the people we are related to by blood but also the people we have committed to do life with,” Bernard says as Gillians wholeheartedly agrees. “Sometimes, our egos get the best of us, and we hurt each other,” Gillian candidly shares. “But being part of a church community allows us to experience what it means to belong to Christ—to practice grace, kindness, and self-sacrifice. I am grateful for every church community I have been a part of, even if I have experienced hurt…like the Southern Baptist church that raised me [during] my Sunday school days to my most recent church before coming to Evergreen LA that provided me with community when I had just moved to LA.”

And what about her current church space? When reflecting on her relatively short time being a part of Evergreen LA, Gillian notes that the church has been healing for her both as a worshipper and as well as a pastoral intern. “Working with children and youth allows me to see how our kids are doing these days, and it’s such a privilege for me to show up as their big sis (or their auntie!). I also enjoy getting to know our Primetimers and hearing their stories of wisdom. This community is such a unique space; it gives me hope about the future of the intergenerational church.”

Bernard shares honestly about dealing with the challenges of the church as a place of inclusion.“In my former congregational context, class and race dynamics posed significant challenges to experiencing full inclusion into the church family. While some leaders were intentional in fostering a truly inclusive community, many members of the dominant culture were resistant to change and to embracing new younger and ethnically diverse attendees in the fullness of our identities.”

As real and widespread as this sort of face value inclusivity is, Bernard also reiterates that not all churches are like this. He adds that “Evergreen LA has provided a hospitable and inclusive environment where the intentionality of community building and embracing people in the fullness of their identity—especially in their Asian Americanness—has helped in fostering a sense of belonging to the church family.” He adds that part of the hospitality he feels from Evergreen has been how the church staff and family have welcomed him and Gillian. “The intentional efforts of our pastors have played a significant role in creating this atmosphere. For instance, Pastor January expressed an intention to incorporate celebrating Filipino culture into our services, especially during Filipino American History Month; Pastor Jason took Gillian and me out for dinner at a local Filipino restaurant; and Pastor Jonathan treated us to breakfast at a restaurant closer to our place of residence in Azusa.”

The current social climate has definitely been a challenging time when it comes to community building and learning to live as an inclusive family. When asked what he thinks is a main challenge for him, Bernard mentions the difficulty of living through and managing layers of difference. “Although in community, differences will always arise and resolutions may never be achieved, differences can be managed in a way that preserves relationships. To combat this challenge, I intend to practice more compassionate listening—to learn the stories and pains that have shaped a person. I hold onto the words of James Baldwin as a principle: ‘We can disagree and still love each other, unless your disagreement is rooted in my oppression and denial of my humanity and right to exist.’”

“Differences can be managedinawaythat preservesrelationships.”

Gillian adds a different perspective on the difficulty of living as family. “I find it challenging to find the balance of taking care of myself while also looking out for my community. Bernard and I are both involved in the Filipino American community organizing space, and when we show up to an activity or protest, we also show up as representatives of the church. What I am learning lately is that I cannot give what I don’t have; sometimes I tell myself it’s okay to put myself first—to breathe, observe Sabbath, process my grief, and recuperate so I can show up and serve my community well. I think anything that allows us to be human is a good spiritual practice to build resiliency; for me, that’s getting enough sleep, regular exercise, and spending time with loved ones.”

Looking toward the future, Gillian hopes to continue pursuing her pastoral calling. “I hope to get ordained, serve my community as a pastor and advocate, and co-struggle with activists, migrants, and laborers here in LA.” While aligned with his partner on pursuing further ministry, Bernard adds, “I’ve also been considering pursuing a Ph.D. in theology with an emphasis in ethics, but this is likely further down the line.”

As a final word of blessing, Gillian encourages us, “For those who feel like they don’t fit the mold or are still searching for home, [allow me to] borrow the words of Father Richard Rohr, ‘You already belong!’”

We are looking forward to Gillian and Bernard’s next steps in life as they continue to build a world of familial belonging for all those in need.

“IcannotgivewhatIdon’t have...anythingthatallowsus tobehumanisagoodspiritual practicetobuildresiliency.”

January Lim

January: Hey Eric, thanks so much for agreeing to share your story with Motif! Could you introduce yourself to our readers?

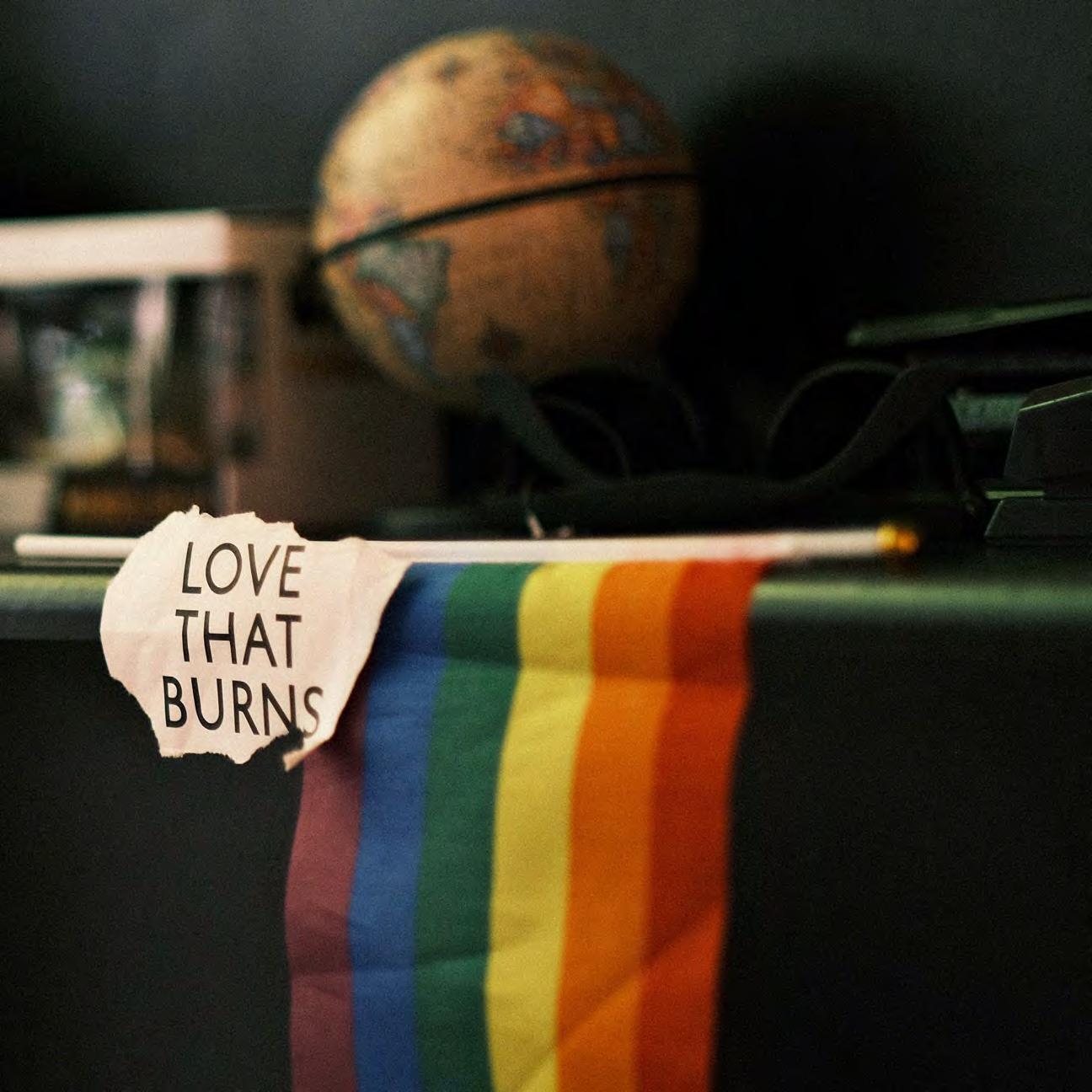

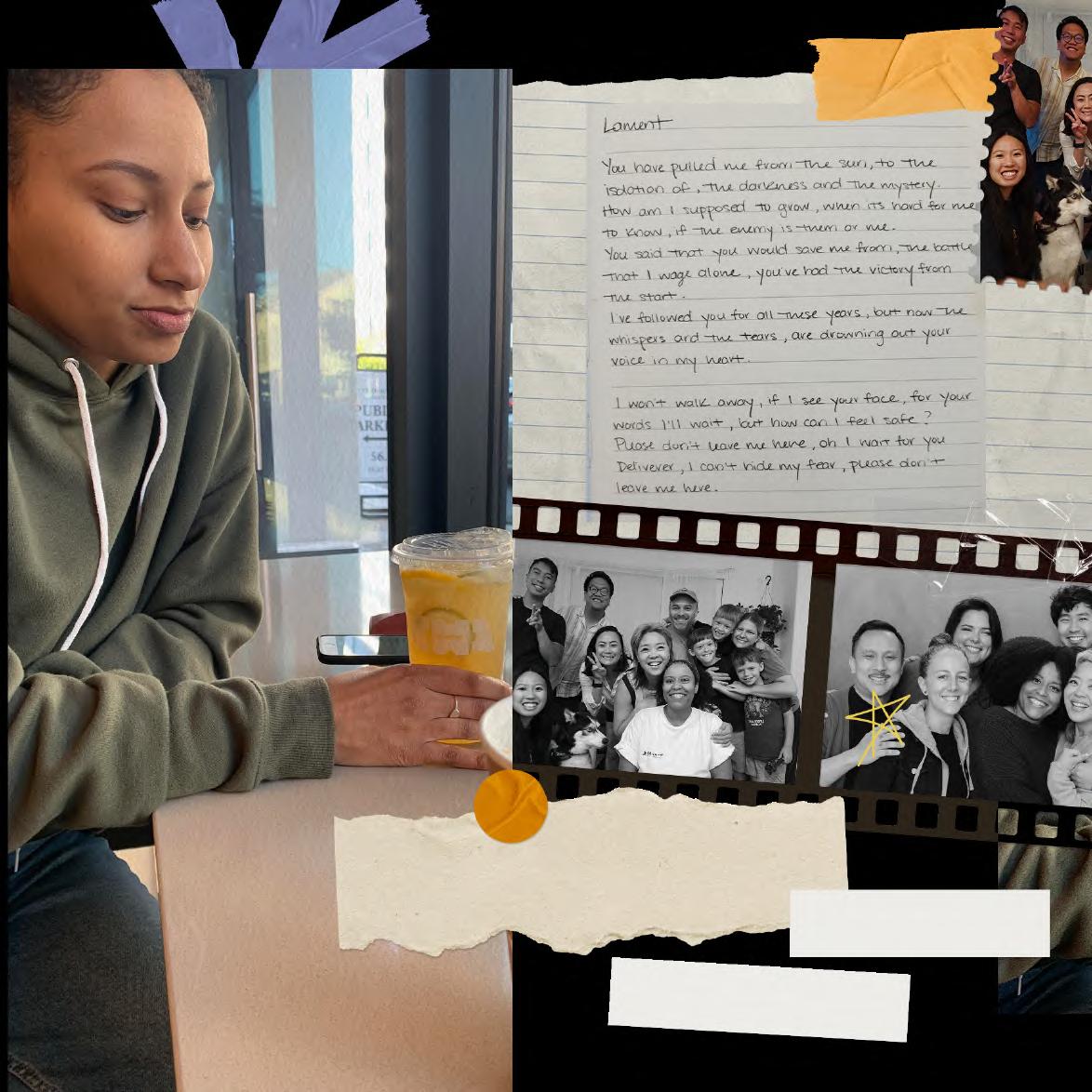

Eric: Hello, I’m eric jamal lige (lowercase usage is intentional as inspired by bell hooks). I’m a gay Black man and identify as cisgender. My identity’s been both a journey and a gift, and it continues to shape how I move through the world.

I am an African American recording artist, songwriter and faith leader who lives at the intersection of Black joy, queer liberation, and sacred truth-telling. I use music, story, and

faith as vehicles to drive people toward hope, healing, and belonging. I currently serve as the Creative Experience Director at Newsong Church in Santa Ana, California. I’ve lived in San Diego for 25 years, but as one of my friends likes to joke, I move around Southern California like it’s my neighborhood.

January: Haha! I love that. And currently, how do you define your vocation and/or career?

Eric: I’m called to help people fully embrace who they are and find a sense of home and belonging. Through music, story,

I create spaces where all people can heal, grow, and move toward the most whole version of themselves.

and connection, I create spaces where all people can heal, grow, and move toward the most whole version of themselves. I believe our individual freedom is tied to each other’s, and that true belonging makes room for mutual flourishing.

January: Beautiful. This issue’s theme is a complicated, layered, and beautifully complex one of “family.” What value has family held in your life? How has the idea of family shaped and formed you?

Eric: Family has always meant a lot to me, even when it’s been…a lot. I grew up in America’s Deep South—born in Birmingham, Alabama, and raised in Lake Charles, Louisiana, moving back and forth between the two states throughout my early years. Family wasn’t just the people inside our house or blood relatives. It was church folks, cousins, neighbors, and the aunties and uncles who weren’t technically related but were always around. These were the people who showed up when it mattered—whether we needed a ride to school, a sudden place to live as we fell upon hard times, or a good pep talk—and the ones who also knew exactly how to get on my nerves. That was part of the “family” deal.

My immediate household was mostly my mama, two older brothers, and my little sister. There were times when stepfathers were part of the picture, and seasons when one or both of my brothers lived with other relatives or friends. Whoever took them in, whether already related or not, became family. So when I talk about family, it’s layered. The people who raised me didn’t all share a last name or live under the same roof, but they shaped me just the same.

From that mix, I learned the power of what many African Americans call Black joy. Not just happiness, but that deep, rooted joy that knows how to rise in pressing times. Joy that

shows up in cracking jokes, storytelling, and sharing food together. There was always food. Sunday lunches after church, family & friend cookouts, folks dropping off plates just because. That rhythm of gathering and feeding each other is still in my bones. Even now here in Southern California, I host what I call my “lunch bunch” after church on Sundays. Everyone’s welcome. No one’s turned away if they can’t pay. That’s family to me. And we look out for each other. That’s the part that I still carry.

January: I love how you mention that family always meant food! And that joy is often tied to sharing time around a table. What were some difficult aspects of living into family for you?

Eric: Yeah, those early years weren't all easy. As I grew into myself, especially as a gay man, I realized there were parts of me that didn’t feel welcome—not at many of those tables, not in church, not even in the little in-between moments. Very early on I learned how to read a room. How to stay small to stay safe. I carried that for a long time. And I’m still on this healing journey towards wholeness.

One memory that’s stayed with me happened in Birmingham during a church-filled Sunday. Our house was crowded, and one of the seasoned women, someone I saw as an ‘auntie’, was chatting with some of the younger folks about dating. Then she turned to me and asked rather directly and loud enough for other people to hear, “Do you like boys or girls?” I froze. I had no words, no safety, no real way to respond. She had helped nurture me in many ways, especially as my mom was away working, but at that moment, I knew there were limits to what she could hold as it related to that part of my identity.

I think this is why my chosen family has become so important to me. Over the past year, a small group of friends from (or connected to) my faith community have become that for me. We show up for one another. We’ve built our own kinda table. It may not be literal, but the connection is real where we share meals, laughter, relatable memes via social media/ text and the kind of soul-deep conversations most of us never had growing up. There’s no shrinking here. No code-switching. Just space to be. It’s not perfect, but it’s real. It doesn’t

erase where I come from, but it’s shaping where I’m headed. And I’m challenged in the best kind of ways by my chosen for myself.

January: Are there any particular chosen or nuclear family members that have had a major impact on you? Either positive or negative?

Eric: My mom is one of the most faith-filled people I know. Even when I’ve struggled with my own matters related to faith, I return to moments of watching her live out her spiritual values—not always in prescribed ways, but in sincere ones that were most meaningful for her in whatever season of life she was in. There were times she stopped attending church—not out of total resistance, but out of self-preservation. Simply put, I see now she was protecting her spirit. Her love for Jesus and people never wavered. When my siblings and I would tease her about not going to church, she’d say (and still says), “Baby, I am the church!” She would reference a Bible passage which speaks of our bodies being the spiritual dwelling places of God’s Spirit. We may not have been gathered in a church building but we always had a house full of people. And where the “two or three” or more were gathered, we had food, laughter, and deep spiritual conversations . Seeing how my mama loved and cared for people shaped how I treat people when we’re all gathered together in community. That made me more mindful of who might be missing in our shared spaces and more intentional about being inclusive.

“The people who raised me didn’t all share a last name or live under the same roof, but they shaped me just the same.“

On the flip side, I had a stepfather who impacted me in a very different way. He taught me responsibility—not because he modeled it, but because he did not. His choices, especially

around alcohol, brought financial instability and chaos into our family in ways which could have been avoided. Those choices led to us having to move around way too much which landed my mom and siblings in situations where we’d have to turn to family or community for living support. I’ve made better decisions in my adult life because of those challenges and hardships brought upon us due to my former stepfather’s choices including alcoholism.

January: How would you describe "family" in this current season of your life? In what ways has it evolved for you?

Eric: Family looks different now than it has in any other season of my life. I live in one city, work in another, and I’m still finding my bearings after leaving a faith community I was part of for over a decade. It’s been a season of starting overrebuilding, reconnecting, figuring out where and with whom I can root myself again. Some days I feel a little displaced. Not just geographically, but emotionally and spiritually too.

Alex and Abi are two close, trusted friends who have been there with me through it all. They live in a different city, so it takes effort to stay close. And if I’m honest, I can be prone to isolation, especially in this kind of transition and in these strange and unusual times we are all living in at the moment. Community here in Southern California doesn’t move like it did back home in Louisiana or Alabama. Folks are busy. Spread out. It’s easy to feel forgotten if you’re not already in someone’s rhythm. But Abi, Alex and I communicate daily and make space for each other. They truly are family to me.

January: Can you share your background with music and how your career has grown throughout the years?

Music has been part of my life for as long as I’ve been alive and breathing. We heard it around my mama’s house, my grandmama’s home, church, school, on the streets, in the stores, and for me, in my imagination. Before I could name it, I would imagine myself on stage singing to crowds of people and inspiring them through song and story. I role played this in my mama’s home when everyone left the house. And I used broomsticks as if they were microphone stands.

I listened religiously, endlessly to the music of Shirley Caesar, Luther Vandross, and Whitney Houston. They were three of my absolute favorites throughout my childhood. Then in ninth grade I was introduced to the music of inspirational singer-songwriter Babbie Mason. And her music took up space in ways that profoundly shaped my love and passion for singing and songwriting. Up until the age of 17, singing was a hidden talent for me and no one in the family knew I loved singing as much as I did. Then, at 17, a music leader at church approached me and said, “I heard you can sing! Is it true?” That conversation led to my first solo at a youth event in Birmingham—and yes, I sang a Babbie Mason song, “Show Me How To Love”. From there, things took off.

A couple years later, I joined a touring band based in Michigan and spent a year traveling the country. When I got back to Birmingham, I started singing regularly at church and picking up gigs. That eventually led me to a small Christian college in San Diego. I toured with one of the school’s vocal groups, recorded my first solo album Surrender in 2009, and a follow-up Sole Desire in 2012.

In 2014, I launched The Ethnos Project Collective—a global network of musicians making intercultural music through audio & video recordings and live performance rooted in faith, hope, and justice. We’ve recorded three studio projects and performed internationally. Between solo work, collaborations, and leadership roles, I’ve now released or produced 14 recording projects, including, as musical worship director, overseeing a live recording of the Urbana 18 LIVE worship album in front of over 10,000 university students.

These days, I’m more mindful about where and with whom I make music. I want to be in spaces that reflect what I believe—love, justice, and the kind of hope that holds space for everyone.

January: Thank you for sharing that with us. Your music is such a powerful gift that you so generously give to those around you! What is your relationship to it and how has it been “kin” to you?

Eric: When I think about my relationship with music, I’m reminded of my personal moments of grief, loneliness, transformation, questioning, reckoning, and all of the “things” of life - good, bad, and indifferent. In every moment someone has created a song that has held me and been with me every step of the way. Even in my dreaming, exploring, resting, and just ‘being’, music has stayed with me. And I’ve stayed with it. We’ve been faithful to each other. And I am just grateful for the folks who said yes to their call to create music that will continue to transform lives long after we humans have said our last goodbye.

One thing I wanna note is, because of where I am in my life journey now, I am mostly drawn to songs created by and for folks on the margins. I want to hear the heartbeat of the composer through the rhythm, story, and flow of their song. I love all forms of music but there are certain musical renderings I feel most at home with. Those are the songs that tend to stick around for a long time and those songs feel like “family” to me because they are so familiar to me.

The music I choose or write has to make space. Space for joy, for protest, for lament, for healing. Space for questions we’re still carrying. Space for people to show up as they are. And that’s what makes it feel like family. It holds me when I need holding. It tells the truth. It doesn’t shy away from the hard conversations. And it keeps evolving with me.

January: Describe a future Eric Lige—surrounded by family. What does that family look like?

Eric: The future version of me—the Eric Lige I’m still becoming—is me being at home with my person whoever that might be. (I’m in manifesting mode, so if you’re reading this... stop playing and come say hi!) I see myself with someone who is fully loved by me and embraced by both the family we’ve chosen for ourselves and the family that has chosen us unconditionally.

I can see me and us surrounded by a kind of family that feels like rest, laughter, and freedom when we’re all together in a shared space. A future version of eric lige ensures that there is a seat at the table for all who have found the strength, courage to show up. I see it as a table of belonging in a space built by love.

That wellspring in me has never run dry. And when I imagine that future, I come back to the heart of why I do what I do: I live to inspire, uplift, encourage, challenge, and call people toward love. Because God is Love.

And like one of the songs I sing says, “Love is calling out to everyone…” So the real question is—are we making room at our table for those still searching for their chosen family?

January: Thank you so much for sharing your story with us, friend.

“The music I choose or write has to make space. Space for joy, for protest, for lament, for healing. Space for questions we’re still carrying. Space for people to show up as they are. And that’s what makes it feel like family. It holds me when I need holding. It tells the truth. It doesn’t shy away from the hard conversations. And it keeps evolving with me.“

By Julie Kim

The sound of water running in the sink wakes me up. It’s the morning, and I’m not sure why I’m not getting dressed or quickly eating breakfast on the way to school. When I call out, umma walks into the room, lies down in bed, and pulls me close.

“You didn’t go to work?” I ask.

“I didn’t need to be in early,” she responds. She puts a cold palm to my forehead and flips it over. I have never been alone at home in the morning with my mom. When I realize this is the first time she has ever been only mine, I am in the mood to tell her about a hundred things: my classroom with the colorful stickers on the carpet, the girl with hair just like the fur on her big brown dog, the boy Tyler who likes to kiss many girls during recess.

I say nothing about being the last student to leave class since we started practicing with clocks. I don’t tell her that the back of my head gets prickly when the teacher tells the students next to me to help me with my work – how one day she yelled at me and sent me to sit in the corner and face the wall all afternoon when I asked these same students a question about the assignment. Umma looks over at the clock on the other side of the room. She gives me one more kiss on the forehead and says, “We’ll have breakfast and then you’ll go to work with me today.” I pull at her shirt but she doesn’t notice as she gets up.

Ever since the class learned how to read clocks, our teacher makes every effort to give us practice. Most days at the end of class she orders us to stand, put away our chairs, and wait by our desks. One by one she dismisses us but only after we correctly read the time that she manually set on the clock in her hands. For weeks this has been our exit quiz. I don’t know how my classmates answer so fast and so well. When it is my turn, I always fumble the first attempt.

“6:45?”

“Try again.”

“5:45?”

“Good. You are dismissed.” That was the first time I gave the right answer in just two tries.

The big hand clicks away and the small spell of our slow morning dissolves. I look back at the clock, but I don’t see what umma sees. I’m only six years old and still very bad at telling time. I know enough, though, to know that ever since we came to Ame rica, there has never been enough of it.

By Julie Kim

remebered

My mother talks a lot. I _______ seeing her in group settings with other adults and wondering how it could be that every time I walked past them, a cluster of anywhere between six to fifteen people, my mother was always the one talking and making the group break out in laughter. And maybe for this reason, until recent years my mother was uncomplicated to me.

Between all our big and small conversations, I came to believe that I already knew everything there was to know about her. I believed everything she said just the way she said it. I paid little attention to the difference between her words and her ways. In that sense, my mother was a mystery shrouded behind a curtain of words.

nothing out of the ordinary.” Some days she added that she hadn’t even been aware of his absence. “I don’t even remember how old I was when he left,” she added as proof.

“Did you ever wonder if he misses you? Your family?” I asked.

“What’s the point in wondering after that?”

I believed her each time. And so it was that I grew up thinking fatherlessness was no big deal, no worse than spring allergies.

Then one day, I told my mom about a new friend I had made at school. “What do her parents do?” she asked me.

“Maybe you get your knack for literature from your grandfather.”

Who? I never knew either of my grandfathers. I knew nothing about my mother’s father–not his name, not even his face.

“I think he had a degree in literature from… I can’t remember. Some university in Tokyo.”

After years of hearing that he wasn’t a part of her life and therefore mine, the news that I perhaps partially owed my aptitude for literature to this man was incomputable. What did this man mean to us? What did he leave behind other than absence?

I knew ______________________

she grew up without a father

I knew that she always spoke about it as something insignificant or even natural. Several times I asked her, “Did you ever miss your dad growing up?”

“No,” she responded. “So many families were missing fathers in those days. It was

“I don’t know,” I answered. “She doesn’t really know her dad.” As I shared more about my friend, my mother grew tearful and said, “Everyone has a story.”

A few years ago when I was just a couple weeks shy of graduating from college, my mom said something completely foreign:

And then I understood—as a literature major, I primarily study people. I examine their histories, contexts, and the manifestations of their pasts in their present. I forecast futures and weigh their interiority against their words and actions, or (more interestingly, personally) their silence and suppression. I look for lies. I’m trained to think about what it means when a character says “Yes” as they put a finger on

a scar, or what it means when they smile at the end of the paragraph. I contrast this smile to all other smiles that appear throughout the story looking at its contexts, motivations, and revelations. This kind of reading was especially important as modern stories introduced more and more unreliable narrators—that’s it. My mother is an unreliable narrator.

Suddenly the person before me seemed so very unfamiliar. She outgrew the outline of “mom,” of 엄마 , and became a somebody , a somebody with a self before motherhood and before marriage. A girl with a mother and a memory of a father. A human with questions, fears, and pain that she didn’t always know how to work through. I see her as a little girl. She had not chosen fatherlessness, but there she was: a little girl of maybe five, six, or seven whose father was there one day and gone the next.

I _____ had asked her about her father many times. Had she asked her mom about him, too? What were those conversations like? Did she–could she–ever walk away satisfied with the response? Was I hearing the deflections and matter-of-factness that she herself had heard? If I can’t even begin to understand her relationship with her parents, how much more was I missing about her?

where we start as 1 tiny cell and become trillions. Their voices shape our consciousness. She was the first thing, and once the only thing, that we know. She was everything and the first thing.

But we emerge much later in their lives, after their building blocks are set. Barring accidents and tragedies, generally we watch them pass on to death as we inevitably continue living. They are there for our beginnings, and we are there for their ending. And because I am forever shut out of her beginnings, I could never know her the way she knows me.

Korean

all around my mother’s many words. I see that maybe she hoped to fill the void left from her fractured family with one of her own, or that she struggles to get through some days, or that she’s carrying all sorts of emotions and experiences that predispose her to tearfulness. Filling in these blanks allows me to learn something new about the world that lives inside her.

Everyone has a story. My mothers is a brilliant one. And though essential, I am just one character in it. To love her is to read her with care. I take my time to fill in the blanks and step closer and closer to her. myself

For many _____ immigrant parents born in the years before, during, and shortly after the war, emotions are often lodged in murky places. This is only reinforced by the violence of migration. Deflections and matter-of-factness are standard tools of communication. And when we manage to get past the first lines of defense, when emotions do emerge, we often find that they have been tampered with. Instead of grief, we are given aggravation. Instead of remorse, spite. The issue of rage is sometimes that at all but fatigue. Loneliness. Injury with no safe, soft place to land.

The mother-daughter relationship has an inverse shape. My mothers are the womb

My mother told me that all her life she just wanted to be a mother and a wife. Sometimes she says she’s fine but can’t seem to get out of bed. She cries when I tell her about something I saw or learned that day. Suddenly I saw shadows and spaces

By Julie Kim

On the first day of American school, my teacher seated me next to a Korean-speaking student named Amy. Like me, Amy is five years old and she had the monumental task of being my translator. When the teacher made waa-ree-grr sounds, I looked to Amy who led me to the carpet for reading time. When the teacher passed out sheets of paper, Amy made sense out of the scribbles, pictures, and lines.

I spent most of my afternoons in the homes of a rotation of other Korean children whose mothers were home. It helped to live in a massive complex with hundreds of units. Word must have gotten around the Korean immigrant social networks because we were slowly making Korean the unofficial language of the playground as children and mothers congregated to play and share news and tips for breeding good, studious children. These mothers picked me up from school with their children. They made us lunch and sat us down for homework. When we were done, they allowed us to run over to the playground or the pool.

But Amy’s mom did things a little differently. She picked us up from school, fed us, supervised our homework, and then allowed me to play while she sat five-year-old Amy down for more studying. Amy was doing something like fourth grade math at the time, while I had barely enough interest to finish my double digit addition problems. I watched Amy cry on several occasions because her mother was so demanding. She studied with a pencil in one hand and a tissue in the other. Not only did she rarely permit Amy to play with me (which was a shame because when given the chance Amy was a fierce, fiery Pink Ranger), she also yelled and smacked Amy’s back when she wanted more focus, more effort, more application from her.

Like me, Amy had an older sister. Amy’s sister was three, four, or possibly five years older than us. She was tall and quiet. She smiled a lot and liked to play games with me when I was done with my homework. She was nothing like my sister, who was eleven at the time and always with friends talking trash, discussing boys and bands and boy bands, or chucking handballs into walls and unleashing pure animal rage in the court. Amy’s older sister didn’t have many friends. While Amy studied fractions and long division, her sister and I learned how to play boardgames all wrong. One day, we opened up Chutes and Ladders without bothering to read the instructions and instead added an element of rock, paper, scissor to move our pieces. Amy overheard us and shouted out a warning, only to have her mother hiss at her.

I knew something was different about Amy’s older sister, not because she played with me more than Amy or my sister did, but because she could

hardly talk and sounded strange when she did. I wish I could tap back into my young mind and recall how I made sense of her disability. All I remember is that I adored her, and her being strange didn’t really matter to me. Back then, different was just different, not any better or worse. Amy and I were different, too. She was so good, studious, and obedient. Similarly, Amy’s mom and my mom were, in terms of archetypes, on opposite ends of the spectrum. My mother wanted nothing more than to play, have fun, and give her daughters space to explore all sorts of experiences–laughing with friends, visiting new places, even falling in love. Her best intentions and philosophies for raising children were, unfortunately, perpetually interrupted by her long and frequent workdays. Most of what I remember about my mom while I was growing up was wanting more of her.

Amy had plenty of her mom—perhaps a little too much. But Amy was like two daughters to her mother: the precocious second-born who followed her mother to the land of fractions and the fill-in firstborn who would be smart and strong enough to survive in this world and make a way for both herself and her disabled sister.

Amy was also two students: one striving to learn and please her teacher with her work, and at the same time, another student leaning over to make sure her immigrant peer was not falling behind. She was a five-year-old leading another five-year-old through her first days in America. She was two different children: an American-born California sunbright child of promise who entered an anxious post-war Korea of vicious competition when she was in her parents’ home.

The Korean immigrant mothers around me often had an old-world disaster preparedness mindset. If I were to die today, your older sister would be your mother. (And don’t forget the cash hidden in the mattress.) I’ve often heard my mom say this to me to invoke a spirit of interdependence and the hierarchy that comes with birth order in Korean families. It bestowed responsibility and authority upon my older sister, and as the youngest, my duty was to follow. We all have our assigned roles in a family like mine. So naturally I wonder how often Amy’s mean mother thought about her own eventual absence. What would obligation and survival look like for Amy and her sister? When I think about that, Amy’s mom stops being so scary and mean in my mind.

Written By Soo Ho Lee

Artwork by Abby Chen

“Let’s get started, shall we?”

She’s attractive. Definitely took the time to do the no makeup makeup look, which I know, after waiting for my wife, takes a good bit of time. She’s dressed professionally but not suggestive, impressive but not sexy. A fine but firm line. She must know men like her style.

“Start where? My childhood?”

“If you want. Whenever or wherever you want to begin from.” I wonder how comfortable she is with silence. Do therapists secretly wish for their patients to wait out the clock? Every second in silence is paid just as much as every second that’s filled with chatter. It’s more awkward but requires less effort. Of course, if the patient feels that these hours are a waste of time and money, then they wouldn’t continue such costly ventures. Thus, cutting the therapist’s income stream.

Then again, I’m the one who feels uncomfortable with silence in front of strangers. And she’s a stranger.

“My father was pretty much absent ever since I can remember. And whenever he came around, he only talked about himself, business, money, and his wish that I follow in his footsteps. He felt like a stranger then and even now after his recent death from the freak drunk accident. My father, he liked to drink. I always thought an accident was bound to happen, given how much he drinks and drives. But this time—the one time that’s life-threatening—it wasn’t his fault. The other driver was drunk and went 50 through a red light. T-bone. Instant death, they told

me, right at the intersection. I didn’t say or even think thank god for a quick death or questioned why. I just thanked the doctor.

“I actually wanted him to suffer a bit. Maybe die on the way to the hospital. Not necessarily survive. Not so that I could have last moments with him. But that he would spend his last moments with regret. And I know he has regrets because I have regrets about him.”

She’s holding a pad but doesn’t write, as if to give the impression that I have her full attention. She’s also silent. Doesn’t ask any follow-up questions.

“They’re not regrets about wanting to spend more time. You know, to make up for lost time. Not regrets that I had a shithead of a father—which, I’ve learned to accept that he’s not the worst of them all. Just the normal amount of shittiness, which is okay, I guess. Not regrets that we could’ve cleared the air between us and fixed what we never really had. Just regrets. Regrets that he was my father and that I was his son. Of this particular hand we’ve both been dealt.”

“But not everything?”

“No, not everything. I am who I am because of my life—things that happened and things I chose to make or allowed to happen. And a part of my life was him, however rarely he came by.”

“Do you like who you are now?”

“I-...yes and no. I mean, mostly yes...”

We’re silent. This silence feels thicker. Did I not want to answer this? Was I caught off guard? I’ve answered this to my friends and family before: “I like me. I feel like I’m not a terrible guy, given how shitty life can be.” And I mostly believe it. But something is stuck in my throat with her in front of me. Do I…want to impress her? But with what? My articulate trauma-dump? My refined ‘woe is me’ speech? My cool, collected disconnect to my own story?

“I do like who I am. I don’t necessarily like how I got here, sometimes. But I also don’t think it’s worth thinking otherwise. Everything that happened happened. I can’t change the past or even other people. I can barely change myself—only how I might react to one thing at a time.”

She holds our silence. Her eyes don’t show a hint of adoration, surprise, boredom, or disgust. Neither does she look empty, devoid of feelings. She’s just looking at me. She sees me.

“How’s therapy?”

“It was okay. Just first session stuff. Childhood and dad, mostly.” My wife approaches and strokes my arm gently. She places a light but tender kiss on my cheek.

I smile softly and lock eyes with her for a few meaningful seconds before I return a kiss on her lips.

I first saw her stifling her laughter. Her face gleamed as her friend shared recent blind date fiascos. All the way from across the room with the speakers blaring, I could hear my future wife’s cackles and snorts in my head. They were so adorable. She was so adorable. I grinned like an idiot. And that just so happened to be the exact moment when she saw me in-between her laughs. Of. Course.

But she held that eye contact longer than when two strangers accidentally lock eyes and awkwardly break. Like when you pull up next to a car at a red light and both of you turn and see each other. She held it just a second longer than normal. That extra second gave me the boldness to drink 2-3 more shots that would generate the courage I needed to approach her. Only fools rush in without some alcohol courage. Or is it that only

fools rush in with only alcohol confidence? Either way, I knew I’d rather look like a fool than miss my chance.

I fumbled for words, and she’d guess to fill in blanks and gaps in my inebriated speech. I’d chuckle nervously and she’d smile coyly. She later told me that at first, she barely understood what I was saying.

“So, why’d you stay with me?”

“Mm, because I wanted to? I mean it was a funny situation, and you were still funny. Plus, the longer we were together, the better I got at filling in the blanks. “

It’s true. True then and true now. She’s good at filling in my blanks. And our silences—not only with words.

She welcomes me warmly. She picks up her notepad, and I notice there’s writing on it this time. Does she write after our meetings? Her memory must be good. She takes a quick glance down and looks up.

“You didn’t mention your mother last time. Could we start there?”

“Yeah, sure. My mom was great. We weren’t close-close, like talking about life and such, but she was there. We never had any major fights or disagreements. Or at least not significant enough for me to remember. She generally supported what I did, and I rarely did things she frowned upon. She died of cancer a few years ago. Cervical. She went peacefully.”

“Did you have regrets then?”

“Just the usual stuff. Wish she didn’t have cancer. Wish she had more time so she could see my kids—if my wife and I ever decide to have them. At least she met my wife, and didn’t hate her. Didn’t seem to love her either, though. They were cordial.”

I’m reminded of dad.

“I don’t have the same kind of regrets as I do with my father. I don’t know. For some reason, I have a harder time accepting his death than my mom’s, even though I loved my mom more. It’s as if I’m more at peace with her passing than my father’s death.”

I rub my hands together.

“My father was torn when he heard of mom’s death. They were separated but not divorced then. Only time I saw him wailing like a maniac was at the funeral. People approached him and pitied him—the majority of them didn’t know my parents were separated. That pissed me off. Why do people who don’t deserve pity always seem to get it?”

“Honey, do you remember mom’s funeral?”

“Yeah, why?”

“Did I cry?”

She looks at me amused.

“You don’t remember? You were wailing. People came up to me and your dad to offer condolences because they felt they shouldn’t bother you.”

Memory is a tricky thing. To remember is to let the present be obsessed with the past. In recreating the past in our minds, however, we’re prone to mistakes. Mistakes that can be colored by anger, bitterness, regret. And a vicious cycle can emerge: a maddening event, a seed of regret, a tainted memory, an unexpected trigger, a tarnished remembering, a deepening regret, an infuriating reminder, a guttural regret, and so on. Regret and memory can feed on each other and sometimes go so far as to mis-remember what actually happened.

I remember now. People did approach my father at my mom’s funeral, not because they pitied him more but because I was inaccessible. I don’t know when I started remembering it wrong. But I did.

I’m more quiet than usual. She doesn’t prod.

“I don’t know what to talk about.”

“That’s okay.”

“I know I have to—I mean, should—talk, but I don’t really have much to say.”

She nods silently in agreement. We spent the rest of the hour talking about work, marriage, friends, and any future vacations planned. Pretty surface-level stuff. She didn’t push anything dee-

per or steer in a certain direction.

Yet, in the back of my mind, I’m thinking about dad. His constant absence casts this distant, egotistical figure in my mind. Like a shadow on the wall, it looms large, but it isn’t really him. It’s more menacing than my memories of my mom. It’s thickening. Suffocating. Why does absence haunt people’s imagination and memories so much more? Why does your absence fill our silences with regret that I have a hard time defining?

God, I mean, why couldn’t you be better? How were you okay with whatever little or shit we had between us? Why didn’t you fucking try, like mom did?

“Mom. Do you regret your life? Marrying dad? Moving to America? Having me? Staying with dad for as long as you did?”

These are the most direct and intimate questions I’ve ever asked her. I sat with her in silence when she had chemotherapy. Sometimes, I’d read a book and she’d doze off. Other times, I downloaded the latest Korean drama for her to catch up on. But this felt like this might be one of our last cogent, private conversations we could have.

She’s silent. She twitches her mouth as if she’s chewing every word.

“I don’t regret having you.”

She doesn’t say any more. She looks with her tired but beatific eyes and sees me. She squeezes my hand, and in that squeeze she says plenty.

"posed, poised" grae fee

Dearest Grandmother,

It has been over a decade since I’ve seen you. As I sit to write, I can’t even think of what I would say if I saw you now. It feels weird to think about catching up with someone who knew me all my life, but never fully got to experience and know me as an adult.

I’d like to think you would be proud of who I have become. I have all the things I should have at this point—a career, a spouse, a house! You wouldn’t believe what they cost these days. I have you to thank for much of my success. There are many ways in which you prepared me for life, through the way you lived and the lessons you taught me. You worked hard, lived humbly, and loved well. You instilled in me values that I hold close—responsibility, kindness, honesty, financial responsibility, selflessness. Of course, I’m a work in progress, but the foundation was set and modeled in our family.

I thought for so long that our family was near perfect. I only have good memories from my childhood—of eating ice cream sandwiches, playing darts, pool, and pinball, doing some light gambling on the penny slot machine, learning to drive out in the desert before I was tall enough to reach the pedals. I’m thankful for the environment that was maintained to protect us kids. As an adult, I can see why some things are kept secret even within family and how hard it must have been to put aside issues for the sake of keeping the peace.

I’ll admit, at times it felt like anything less than perfect in our family was a disappointment, that actions that were not in line with expectations would bring shame to our family name, something that was especially fragile in a small town. Going away to college, I felt excited to explore what the world had to offer. One of my fondest memories of us is when you took me shopping for all of my dorm essentials. It felt like a shopping spree, even if we were just at Walmart.

During college I came home less and leaned into new relationships. I started out strong attending church and small groups, finding some friends, but inevitably ended up gravitating to the new freedom of being away from home. Soon, making it to church at 10:30 was out of the question, since waking up by 10 was a challenge. I made it to my second semester before I started drinking.

In my sophomore year, I had a crush on one of my friends. We got closer as the year went on and by the summer we were in a secret relationship. Throughout this time, I struggled with what I learned growing up in church. This was a sin, but all I felt was love for a person. Our secret began eroding the other friendships around us. I would often fight with Alicia because she knew I was hiding something.

This all coincided with your cancer progressing; each time I went home and saw you, I could only think about how I was living a life you wouldn’t approve of. My avoidance wasn’t just the pain of seeing you die, but also the pain of having to confront my decisions. You were nearing the end and we all went to your house and shared what you meant to us. I broke down crying as I spoke, in the back of my head knowing I was a disappointment. A couple weeks later I called to tell you I love you and that I’ll see you soon, knowing that wouldn’t be here on earth. You passed just after I hung up the phone.

Everything felt broken around me and it felt like I caused it. I decided it was best that I step away for a while. I studied abroad in England for the second semester of my junior year. It was truly the best thing I did in college. I visited 13 countries and shared it with some of the best people. Still, I struggled with my secret. Does God really condemn gay people? How can it be wrong to love someone simply because we are the same gender? Living with this secret, I began to feel deep shame. I thought of you and how I had let you down. I let God down, after all he had blessed me with, how could I go against him? I returned home and left the relationship in the past, knowing there was no future for us.

Life went on and time began its healing process. I graduated college, got a job, mended friendships, and got back to church. I found community within church, a chosen family that I navigated the craziness of young adulthood with. And, in the most traditional way of finding a mate, I found my future spouse.

I met Kennah at Bethany Church in 2016. We talked one night after young adults group and quickly connected over our love for travel. We saw each other sporadically at church and occasionally served together when I was on the tech team and she was on the worship team. I found myself wanting to spend more time with her. I remember someone saying she was gay, and I was curious about that, because she was still at church. She was the first gay Christian I had ever met; I honestly didn’t know they existed. My feelings for her began to grow, but I still believed it would be wrong to pursue anything. I shared how I was feeling with trusted friends. I was afraid of where this could lead. Kennah challenged me to read about other theologies, pray about it, and see where God would lead me. This opened a whole new world for me. I never felt that gay people were an abomination. We were taught to love the sinner and hate the sin, but I never felt there was anything to hate. I watched videos of so many gay Christians living a life for God, as evident in the good fruit they bore. These stories resonated with me. I know you’re probably feeling a lot of emotions at this point, but I’m sharing this with you because I want you to know more of who I am today.

After accepting that I was gay, I shared with my close friends and eventually family. I am lucky that the people I love did not shut me out. While they may not agree with the theology, they chose to love and support me. It took many years, open, honest conversations, and commitment to each other as we navigated it all together.

After disclosing our relationship to our church leaders, Kennah and I were asked to step down from all areas of serving within the church, ultimately leading us to leave Bethany. In Summer 2017 we found Evergreen. It is a church where we felt at home from the first time we went, a place that felt familiar in its teaching of the bible and comforting in its acceptance of us as a couple. We began serving in different ministries, building relationships, and committing to our church family. In 2021 we became the first gay couple to be married by an Evergreen pastor, a dear friend of ours. Our parents and siblings were at the wedding and they continue to build relationships with both of us, which is a true testament to their love and commitment to us. Together we have built a robust chosen family of friends past and present, that consistently do life with us. Our nuclear families have also grown exponentially as our siblings and cousins have kids. It’s been one of our greatest joys to be part of these kids’ lives. Every night we go to bed feeling like the luckiest people in the world.

I don’t know what life would have been like if you were still here. I often think I wouldn’t have had the courage to fully be myself. But there have been snippets of hope that I cling to:

1. I’ve watched my mom truly love me and Kennah. She calls Kennah her daughter, visits us often, and does countless acts of service that show her love for us. Since you raised her, I can only imagine you would treat me similarly.

2. I’ve seen you love others you didn’t agree with, especially in our family. Despite differences in beliefs, you consistently showed up and supported those people.

3. You’ve visited in my dreams. In one dream I knew you had already passed, but we were at a gathering and I saw you there. Kennah was with me and I was so excited for you two to meet. You were excited to meet her too. You and I embraced and started dancing. It felt like God sent you to tell me you accept and celebrate us.

I definitely hit the jackpot with you as my grandma. I miss you, I love you, and I’ll see you soon.

Love,

Your favorite granddaughter, Randi

ARTHUR AU

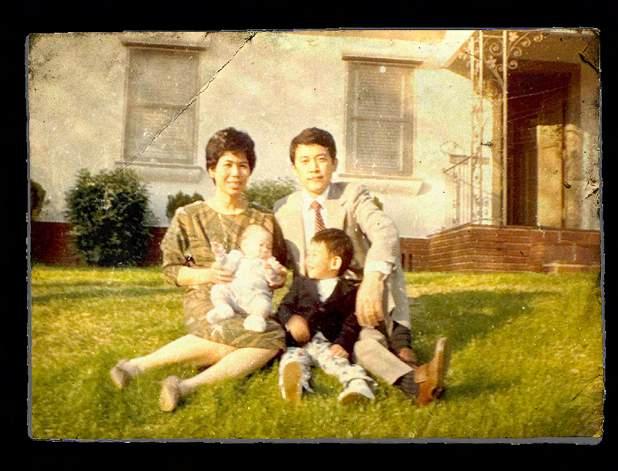

My name is Arthur Au. My given Chinese name is 欧安信 (Au Ān-sìn). I was born in 1985, the first son of Taiwanese immigrants.

My parents brought me up speaking Taiwanese at home so I could communicate with my grandmother. By 1987, my nuclear family consisted of my 阿媽 (paternal grandma),爸爸 (dad), 媽媽 (mom) and弟弟 (younger brother). I have fond memories growing up in my grandma’s house in Alhambra. I watched my grandma pay attention to details and aesthetic – sewing, mending and tailoring clothes. I saw my dad juggling responsibilities, working full-time while attending night school. I saw my mom cleaning, cooking, and taking care of us. When I was about to turn five, we moved out of my grandma’s house into my parent’s new home in Covina.

In Taiwanese, I was frequently called koai gín-á for being a good and obedient child. I was polite and well-behaved in public; gentle and kind to my younger brother. I felt special whenever people praised me for my good behavior. It deeply formed me, and I learned to keep following rules and not cause any trouble.

On Sundays, I went to church. My family attended Evangelical Formosan Church of Los Angeles (EFCLA), where many other 1st and 1.5 generation Taiwanese families gathered for faith and community. I attended Sunday school, children’s choir and learned all the stories in the Bible – who Jesus is, and that God loves me. My dad also volunteered in Children’s Ministry while I was in it. Values for faith and family have always played an important role in my life, and I’m grateful for my mom and dad.

I knew I was ‘gay’ from a very young age. I didn’t have the exact word to call it, but I knew I was different, or special. I kissed a boy on the cheek in my 2nd grade class. But as care-free and out-going as I started, I slowly pulled back when I experienced bullying. I was made fun of for my mannerisms, for running “like a girl” and the way I talked. I always felt safe and comfortable being with girls and didn’t share much of the same interests with other boys. When I heard kids make gay jokes, or say “that’s so gay”, etc. I thought something was wrong with me that needed to be fixed. I also thought to myself, “Hey, I’m a Christian; I’m not gay”. Finding belonging and connection with all the complex aspects of my identity was challenging. Throughout my teenage years, I was reserved, shy, and kept my thoughts and feelings to myself. No one must know. “I’m ok… no problem… I’m alright.” But I loved the piano. It was a sanctuary and a way for me to escape and relieve stress.

The summer after graduation, I moved back home and eventually found a full-time job as a R&D Lab technician. I actively served at my home church’s English ministry, Harvest LA and played piano for the worship team. It was a good season of my life where I felt connected and found joy in serving at the church. I was content and happy with my job and life. In 2010, I decided to go forward with a five-year medical school program in China. I was surprised at how my parents blessed me to go, and I had enough savings to cover the first few years there. Looking back, I sensed God leading me to go to China, but it wasn’t for the reason of becoming a doctor. This was my first time studying far away from home.

In 2003, I went to college at UC Riverside. In my 4th year, I discovered alcohol. “Fun drunk” Arthur could once again be that care-free person. I didn’t have to worry or stress out any more about what people thought of me. I got used to balancing so many things that it felt like I was living two lives – church Arthur and fun Arthur. I purposely kept them separate.

By the grace of God, in May 2007, I was given a wakeup call that changed my plans for my 5th year. The promotion as a student Assistant Resident Director that I was looking forward to was withdrawn because of an unfortunate situation involving drinking while on duty. But even through the loss and disappointment, I somehow knew everything was going to work out because God was watching out for me.

The experience expanded my worldview, and I got the privilege of meeting different people from across the world. After my four years in China, I finished my 5th year back in the US hospital system, where I did my clinical rotations in Phoenix, Arizona. It was a grueling and difficult year, but also a very special one for me to experience a level of vulnerability and intimacy that I had never experienced before through a small group with Harvest Bible Chapel. I knew I only had one year there, so three friends and I dove in, connecting deeply with purpose and intention. (Looking back, I could have also come out to this group, but I wasn’t ready.) God took me on a journey to prepare me for my coming out journey. The Lord needed to teach and show me that my identity wasn’t in my career, my test scores, or my reputation, but simply that I am a child of God. I carried the weight of expectations – from my family, my friends and even my church community. I wasn’t afraid of letting myself down, but I was terrified of letting others down.

In 2018, my college friend called me up one day to share about his dating relationships and heartaches. He asked me, “Do you ever get lonely?” That was the question that finally started the conversation about sexuality. I came out to my mom and dad shortly after. During this time, my parents knew something was weighing on my heart. I knew on my end that my parents needed to hear from me that I was still a Christian who loves God. I heard from my parents what I needed from them: I was still their son, and they still loved me. My parents asked me to give them time to process, and out of honor and respect, I did. After three months, I felt the Holy Spirit prompting me to write a letter to the church. After I seeing my thoughts written down on paper, coming out felt much more real. I shared the letter with my church family in early 2019 while leading worship on a Sunday morning.

For my child-self: my nuclear and extended family who raised me and loved me. Who allowed me to enjoy being a kid, feel happy, carefree, safe and protected.

For my college-self: my biology major friends who I studied with, my mentor and staff that I trained with, ate with, and celebrated with, my small groups that I prayed and worshipped with.

For my 25-year-old self in China: my friends that I found to be like family away from home, as we ate, studied, exercised, shopped, partied, and did ministry with.

For my 29-year-old self in Arizona: my roommate and small group that taught me what community is and how to live out having Jesus be the center. It has been the physicians that trained me and the medical students that encouraged and helped me succeed.

For my 30-year-old self: EFCLA and Harvest LA as I returned to ministry, leading worship, a small group, and being a deacon. My Friday night fellowship group who walked with me as I engaged in conversations about sexuality.

For my 34-year-old self: Evergreen Baptist Church of Los Angeles, (EBCLA), The Open Door, my home group, and the Worship Arts and Tech Ministry. All sacred spaces for me to find queer Christians and allies who support and encourage me to live authentically.

Alexander Shippee, for his love and commitment to build a life with me. I’m excited for what chosen family looks like in this next season.

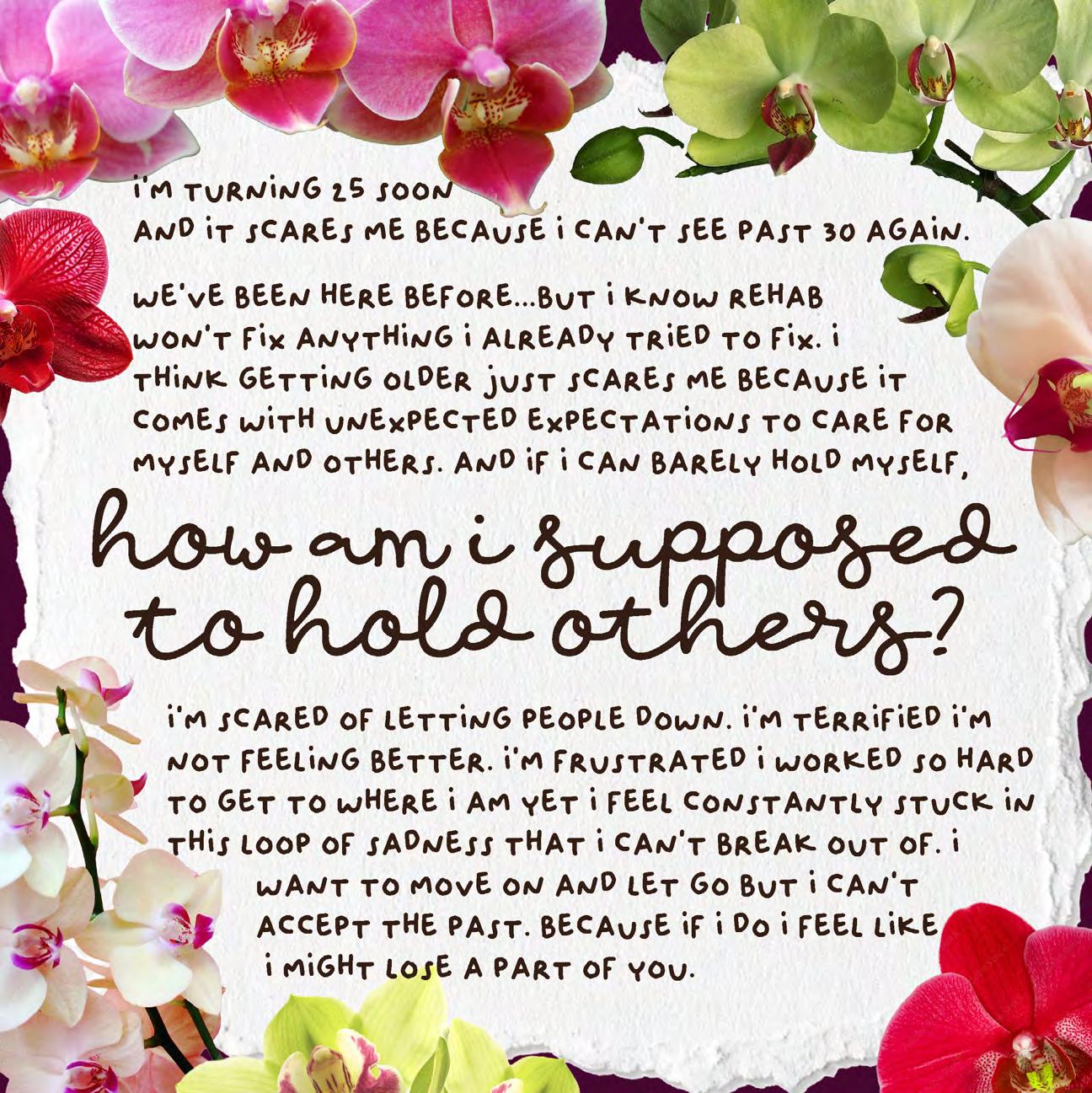

Dear friends and family,