JournalofChildandFamilyStudies

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-025-03082-3

BrokenBonds:CaregivingStabilityAmongInfantsExposed PrenatallytoMaternalIncarceration

Accepted:6May2025

©TheAuthor(s),underexclusivelicencetoSpringerScience+BusinessMedia,LLC,partofSpringerNature2025

Abstract

Maternalincarcerationamongolderchildrenhasbeenlinkedtoadverseoutcomesduringchildhood.Lessisknownabout exposuretomaternalincarcerationprenatallyorininfancy.Caregiving-relatedfactors,particularlyinstabilityincaregivers, mayincreasechildren’sriskforpooroutcomes,butfewstudieshaveassessedcaregivingrelationshipsinthisvulnerable population.Thepurposeofthisstudywastoutilizeauniquecohortofinfantsexposedprenatallytomaternalincarcerationto investigatechildren’scaregivingexperiencesininfancy.Weanalyzedclosedandopen-endedsurveyquestionsfrom caregiversof57infantscollectedatbirthandwheninfantswerethree,six,nine,andtwelvemonthsoldtoascertainthe incidenceofchangeincaregivers,whychangeoccurred,andanypredictorsofchange.Wemappedinfants’ care arrangementsusingalluvialplots,calculatedtheincidenceofchangeincaregivers,conductedatextualanalysisofopenendedquestionsandusedCoxproportionalhazardsmodelstoascertainpredictorsofchangeinprimarycaregivers.Results revealedthatinfantsprimarilyremaininthecareofagrandparentorotherkin.Instabilityinprimarycaregiversaffectedone quarterofthesample.One fifthofinfantsexperiencedinstabilityinnon-maternalcaregivers.Theprimaryreasonschildren experiencedachangeinnon-maternalcaregiverswerechildwelfarerelated.Beingplacedwithakinshipcaregiveratbirth wasprotectivefordisruptioninnon-maternalcaregivingrelationships.Ourresultssuggesttheseinfantsareathighriskof instabilityinprimarycaregiving,potentiallypredisposingthemtoadversedevelopmentaloutcomes.Caregiversofinfantsof incarceratedmothersshouldbetargetedforenhancedsocialsupport.

KeyWords Incarceration Infanthealth Attachment Childwelfare

Highlights

● Childrenexposedprenatallytomaternalincarcerationareanunderstudiedpopulationatparticularriskforadverse developmentaloutcomesduetobothprenatalincarcerationrelatedexposuresandcaregivingrelatedpostnatalexposures.

● Thisstudyisthe firsttoprospectivelyassesscaregivingamongchildrenexposedprenatallytomaternalincarceration duringinfancy,acriticalperiodforchilddevelopment,withaparticularfocusoncaregivinginstability,including predictorsofinstability.Weusedavarietyofdescriptiveandanalyticalmethodstotriangulatechildren’sexperiencesof caregiving.

● Aquarterofchildreninoursampleexperiencedadisruptionincaregivingintheir firstyearoflife,anda fifth experiencedadisruptioninnon-maternalcaregiving.Caregivingdisruptionswereprimarilychildwelfare-related,but alsoincludedreunificationwithformerlyincarceratedmothers,andinformalmovesbetweennon-maternalcaregivers.

● Beingplacedwithakinshipcaregiveratbirth,includingaformerlyincarceratedmother,wasprotectiveagainst instabilityinprimarycaregivers.

* BethanyC.Kotlar bkotlar@hsph.harvard.edu

1 HarvardGraduateSchoolofArtsandSciences,Cambridge,MA, USA

2 BystroAI,Boston,MA,USA

3 EmoryUniversity,Atlanta,GA,USA

4 HarvardT.H.ChanSchoolofPublicHealth,Boston,MA,USA

5 JohnsHopkinsSchoolofMedicine,Baltimore,MD,USA

6 UniversityofMinnesotaMedicalSchool,Minneapolis,MN,USA

PrenatalandPostnatalIncarceration

TheUnitedStates(US)hasthehighestincarcerationratefor womenintheworld(Fair&Walmsley, 2022).In2022, approximately180,700womenandgirlswereincarcerated intheUS(Carson&Kluckow, 2023;Zeng, 2023).Ina 2016surveyofincarceratedwomeninstateprisons,58% wereparentswithminorchildren,andapproximately16% ofthesechildrenwereaged4yearsoryounger(Maruschak etal., 2021).Furthermore,anestimated4%ofwomenin stateprisons,and3%ofwomenincountyjailswere pregnantatadmission(Sufrinetal., 2019;Sufrinetal., 2020).Asubstantialbodyofresearchhasdocumentedthe targetingofmarginalizedracialandethnicgroupsandpoor peoplebythecriminallegalsystem(Alexander, 2012;Pettit &Western, 2004;Roberts, 1997).Indeed,Blackpregnant andparentingwomenhavebeenparticularlycriminalized (Sadler, 2021).Inaddition,incarceratedpregnantwomen aremorelikelytoreportmentalhealthissues,substanceuse, andexposuretotraumaticevents(Knight&Plugge, 2005). Bothstructuralmarginalizationandmaternalriskfactors predisposechildrenofincarceratedmotherstosubsequent developmentalissues(Dallaireetal., 2015).

Beyondthesepregnancyandpre-pregnancyriskfactors foradversechildhealthconsequences,maternalincarcerationduringpregnancyandinfancyishypothesizedtobe particularlydamagingtochilddevelopmentviaseveral pathways.Thecontextofincarcerationmaycompoundthe influenceofpre-incarcerationtrauma,substanceuse,and mentalhealthissuesonchildhealthoutcomesviaasuboptimaluterineenvironmentcharacterizedbysubstandard prenatalcare(FersztandClarke, 2012),poornutrition (Shlaferetal., 2017;Vitaglianoetal., 2024),andharmful practicessuchasshacklingorsolitaryconfinement(Jensen, 2021).Indeed,asmallbodyofliteraturehaslinkedpregnancyduringincarcerationwithadversebirthoutcomes, suchaslowbirthweightandpretermbirth(Howardetal., 2010;TestaandJackson, 2020).

Infantswhoareborntoincarceratedmothersmaybe exposedtofurtherriskfactorsforadversedevelopment. Whilesomefacilitiesallowwomenwhogivebirthduringincarcerationtoresidewiththeirinfantforayearor morepost-birth,theseprogra msarefewandrestrictedto asubsetofmotherswithshortersentences(Jensen, 2021 ; Kotlaretal., 2015 ).Mostinfantsbornduringtheir mothers ’ incarcerationareroutinelyseparatedfromtheir mothersshortlyafterbir thandplacedwithanonmaternalcaregiverlivingint hecommunity(Kotlaretal., 2025 ).Forinfantsbornduringtheirmothers ’ incarceration,additionalfactorsrelatedtomaternalincarceration mayleadtoadversedevelopmentaloutcomes,including risksassociatedwithchildren ’ scaregivingenvironments,likepovertyandcaregivermentalhealth,aswell

asdisorderedattachmentcausedbyunstablecaregiving relationships.

TheoreticalFrameworksforMaternal IncarcerationandChildWellbeing

ResearchershaveusedframeworksintegratingBronfenbrenner’sdevelopmentalecologicalmodel(Bronfenbrenner, 1979)andBowlby’sattachmenttheory(Bowlby, 1999)tounderstandhowpostnatalmaternalincarceration negativelyimpactschilddevelopment(Arditti, 2005;MurrayandMurray, 2010;Poehlmannetal., 2008).The developmentalecologicalmodelpositsthatchilddevelopmentisinfluencedbycomplexreciprocalrelationships betweenthechildandtheirsocialenvironment,which Bronfenbrennerproposedexistedatfourbroad,nested levels,themicrosystem,mesosystem,exosystem,and macrosystem,eachofwhichinteractwitheachotherto shapeachild’slivedcontextandthusdevelopment(Bronfenbrenner, 1979).Whileallfoursystemscomeintoplayto shapechilddevelopment,themicrosystem,orthesystems andgroupsthatdirectlyimpactthechild’sdevelopment, particularlythechild’sfamily,isespeciallyimportantin infancy.Attachmenttheoryarguesfortheimportanceofa warmandengagedprimarycaregivingrelationshipduring childhoodforhealthysocialandemotionaldevelopment overthelifecourse.Bowlbypositedthattheabsenceor disruptionofthisrelationshipcanleadtoadversedevelopmentaloutcomes,particularlyforsocialdevelopment (Bowlby, 1999).Withinthecontextofearlylifematernal incarceration,childrenborntoincarceratedmothersare deprivedtheabilitytodevelopastrongattachmenttotheir motherduetoearlylifeseparation(Jensen, 2021).Thus, stableattachmenttotheircaregiverduringtheirmothers’ incarcerationisanimportantpotentialpredictorofdevelopmentaloutcomes.

Maternalincarcerationduringtheprenatalandpostnatalperiodsthreatenstheinfant ’ sabilitytodevelopand maintainasecureattachmenttoaprimarycaregiverat everyleveloftheecologicalmodel.Atthemacrosystem, theUScultureofpunitiveresponsestocrimes,particularlysubstancedependence,hasshapedthecurrent criminallegalsystem.This systemisprimarilycharacterizedbythefrequentincarcerationofpregnantand postpartumwomenandforcedma ternal/infantseparation atbirth(Jensen, 2021 ;Kotlaretal., 2015 ).Inmoststates, incarceratedwomenarecon fi nedinprisonsandjails regardlessoftheirpregnancystatus.Furthermore,ifa womangivesbirthduringherincarceration,sheistypicallyseparatedfromhernewborn,whoisplacedwitha non-maternalcaregiverfortheremainderofthewoman ’ s incarceration(Jensen, 2021 ).

WithintheU.S.criminallegalsystem,incarcerated womenareconfinedattwodistincttypesoffacilities:jails andprisons.Carceralfacilitiesandtheirpolicies,while structurallybelongingtotheexosystem,infl uencethelower systemsbyconstrainingwhetherandtowhatextentthe motherisinvolvedwithherchild’slife.Althoughpolicies differbystatesandcounties,womenheldinjailareeither awaitingtrialorsentencingorareservingatermoflessthan ayear.Incontrast,womenconfinedinprisonshavetypicallybeensentencedtoatermofayearormore.Whethera motherisincarceratedatthecountyjailorstateprisoncould influencechildwellbeingbydeterminingthelengthofthe child’sseparationfromtheirmother(Poehlmannetal., 2008).Becausemothersincarceratedinjailstypicallyhave shortersentences,separationfromherchildisonaverage muchshorterthanformothersincarceratedinprison.Inthe caseofpregnancyduringincarceration,mothersmayserve ashortsentenceinjail,butbereleasedbeforethebirthof thechild.

Carceralfacilitiesalsodeterminetheamountofcontact infantsandtheircaregivershavewiththeincarceratedmother. Jailsareoperatedatthecountylevel,andthusarevariedin theircapacitytosupportvisitationandcontactbetweenan incarceratedmotherandherinfant(microsystem)orthe incarceratedmotherandherchild’scaregiver(mesosystem). Jailstypicallyhavefewerresourcesandpoliciesthanprisons surroundingfamilyvisitation,oftenforegoinginpersonvisitationentirelyinfavorofvideovisitation(Poehlmann-Tynan andEddy, 2019).Videovisitationiswoefullyinadequateto thedevelopmentalneedsofinfants,whorelyonphysical proximity,cleareyecontact,andserveandreturninteractions toformrelationships(Poehlmannetal., 2008).Thus,the facilityinwhichanincarceratedmotherisheldisakey exosystemlevelfactorinfluencingthedevelopmentofinfants exposedprenatallytoincarceration.

Beyondthepoliciesuniquetocarceralfacilities,maternal involvementinthecriminallegalsystemthreatensthe infant’sdevelopmentbyimpactingacaregiver’scapacity (whethertheprimarycaregiveristheinfant’smotherora non-maternalcaregiver)toprovideappropriateandstable careforthechild.Childrenwithincarceratedmothersare mostfrequentlycaredforbyotherrelatives,typically grandparents(RodriguezCarey, 2019;Glaze&Maruschak, 2008;Pendletonetal., 2021;Kotlaretal., 2025),although studiesassessingcaregivinginthecontextofprenatal exposuretoincarcerationassessedcaregivingretrospectively.Grandparentalcareofolderchildrenofincarceratedmothershasbeenassociatedwithmoremotherand childcontactandhigherlikelihoodofherfuturereuni ficationwithherchildrenthanothercarearrangements(Loper &Clarke, 2013),however,thiscomesataprice.Studies haveshownthatcaregiversofchildrenofincarcerated mothersstrugglewithpoverty(Pendletonetal., 2021),and

otheradversitiessuchasfoodinsecurity(Cox&Wallace, 2013),andhousinginstability(Shaw, 2023).Furthermore, thereisevidencethatfamiliesofincarceratedmothersare negativelyimpactedbyherincarcerationthroughlossofher income(Glaze&Maruschak, 2008),potentiallossofchild support(Ardittietal., 2003),andthesignificantcostoflegal finesandfeesandofmaintainingcontactwithanincarceratedmother(Sandiford, 2007).Inaddition,thestressof theincarcerationofafamilymembermayleadcaregiversto experiencepoormentalhealthorengageinharshparenting styles,whichhavebeenshowntoincreaseinternalizingand externalizingbehaviorsinschool-agedchildrenofincarceratedmothers(Dallaireetal., 2015).Inasampleof childrenbetweentheagesoftwoandsevenexperiencing maternalincarceration,Poehlmann(2005a)foundthat caregiversociodemographicriskfactorssuchaspoor health,lowereducationalattainmentandhighernumberof dependentspositivelypredictedlowercognitivescores,but thisrelationshipwasmediatedbyawarmandsupportive familyenvironment.However,thishasnotbeeninvestigatedinchildrenexposed prenatally tomaternalincarceration,whoexperiencecaregivingduringinfancy,a criticalperiodforchilddevelopment.

CaregiverStabilityintheContextof MaternalIncarceration

Onlyonestudyhasinvestigatedcaregivingrelationshipsof infants ofincarceratedmothers.Pendletonetal.,retrospectivelyinterviewed30caregiversofinfantsofincarcerated mothersinaMidwestprison(2021).Aquarterofcaregivers inthissamplereportedlivingbelowtheFederalPovertyLine (FPL)and37%reportedhavingtoworklessbecauseof assumingcareoftheinfant.Caregiversalsodescribedstress relatedtoenrollinginsocialservicesandworseninghealth duetocaregiverresponsibilities(2021).Whileexposureto household-leveladversitylikepovertyandcaregiverdistress candirectlyimpactchildren’sdevelopment,theseriskfactors mayalsoincreasethelikelihoodthatchildrenexperience instabilityinprimarycaregivers.

AsBowlbyasserted,disruptionsinprimarycaregiving relationshipscanpredisposechildrentoadversesocialand behavioraldevelopment(1999).Inthecontextofmaternal incarceration,changesinprimarycaregiverscouldoccurifa childismovedfromoneprimarycaregivertoanotherduring themother’sincarcerationeitherbychildwelfareorbythe child’scaregiver,ifthemotherresumesexclusivecareofthe childonherrelease,orifamotherwhowasreleasedbefore herchildwasbornorresumedcareofthechildafterher releaseisreincarceratedorrelapses,relinquishingcustodyof thechild.Thereisemergingevidencethatmaternalincarcerationduringthepostnatalperiodleadstoinstabilityin

primarycaregivingrelationships-abruptchangesinwho providescareforthechild-overandabovematernal separationatbirth.Asinglestudysuggeststhatcaregivingin thecontextofmaternalincarcerationfrombirthishighly unstable.Pendletonetal.,foundthatonly45%ofcaregivers interviewedhadretainedcustodyofthechildbeyondthe first yearoflifeandoftheseonlyaquarterhadmovedintothe careoftheirmotherafterherreleasefromprison.However, Pendletonetal.,werenotabletoassesswhythesechangesin non-maternalcaregiversoccurredduetoaretrospective design.Oneunderstudiedpossibilityforinstabilityinprimary caregivingthatoccursduringamother’sincarcerationischild welfareremoval.Researchershavedocumentedthedisproportionatenumberofchildwelfarecasesandchild removaloccurringinfamiliesminoritizedduetoraceand poverty(Kimetal., 2017;Roberts, 2022;Wildeman& Emanuel, 2014),whoarethefamiliesthataremostoften targetedformassincarceration.

Reuni ficationwiththeincarceratedmotheruponher releasemayalsobeasourceofinstabilityinprimarycaregivingrelationships.Evidencefromresearchwithincarceratedmothersofolderchildrensuggeststhatchildren rarelyvisitmothersduringtheirincarceration(Poehlmann etal., 2008).Forinfantsseparatedfromtheirmothersat birth,in-personvisitswiththeincarceratedmotherwouldbe theonlydevelopmentallyappropriatewaytobuildand maintaintheirrelationship.Thus,mostinfantswithincarceratedmotherswouldhavebeendeprivedoftheabilityto formasecureattachmentwiththeirmothers(Poehlmann, 2005b),andwouldinsteadhavebondedprimarilywiththeir non-maternalcaregiver.Ifformerlyincarceratedmothers assumeexclusivecareoftheirchildrenonuponrelease, childrenmaybeatincreasedriskofdisruptionsintheir attachmentrelationships.

Finally,infantsmaybeatriskofdisruptionsincaregiving inthecontextofreincarcerationorrelapseofamotherwho hasservedasaprimarycaregivereitherfrombirthorfora periodafterherreleasefromincarceration.Studiesonthe stabilityofmaternalcaregivingpost-incarcerationarerare.A singlestudyofmothersandtheirinfants,whohadresided togetherinaprisonnurseryduringthemother’sincarceration, foundthatonreleasefromprison,17%ofmotherswereno longertheprimarycaregiversoftheirinfantattheendofone yearduetorelapseorreincarceration(Byrneetal., 2012).

Abruptearlylifechangesinprimarycaregiversputs infantsatriskfordisorderedattachment,aknownriskfactor foradversecognitiveandsocialandemotionaldevelopment (Schuengeletal., 2009).Astudyofchildrenwhoparticipatedinaprisonnurseryprogramwiththeirincarcerated mothersfoundthatchildrenhadmoresecureattachmentas comparedtochildrenwhosemotherswereincarceratedafter theywereborn,duringinfancyortoddlerhood(Byrneetal., 2010),suggestingthatmaternalseparationplacesinfantsat

riskofdisorderedattachment.Evidencefromstudieswith olderchildrenhasalsoshownthatcaregiverchangesduring themother’sincarcerationputschildrenatfurtherriskof attachmentissues.Inastudyconductedinasampleof2–7year-oldchildrenwithincarceratedmothers,morenonmaternalcaregivinginstabilitywasassociatedwithahigher riskofinsecureattachment(Poehlmann, 2005b).

Thus,exposuretomaternalincarcerationintheprenatal andpostnatalperiodsrepresentsasigni ficantthreattochild andfamilywellbeingthathasthepotentialtoseverely disruptprimarycaregiverstabilityduringarecognized sensitiveperiodforthedevelopmentofattachmentrelationships.Yet,therehasbeenamarkedlackofresearchinto theprevalenceofdisruptedcaregivingoritspotentialpredictorsinthispopulation.Itisimperativetofullyunderstandcaregivinginthecontextofmaternalincarceration, particularlypredictorsofdisruptedcaregiving,tobuild evidence-basedpoliciesandprogramsthatcanprotect vulnerablechildrenandtheirfamilies.

TheCurrentStudy

Thepurposeofthisexploratorystudyisto fillacriticalgap intheliteraturebycharacterizingcaregivingrelationships forinfantsexposedprenatallytotheirmother’sincarcerationinthe fi rstyearoflifeandidentifypredictorsofcaregiverstability.Toachievethisgoal,wedrewdatafromthe BirthBeyondBarsStudy(BBBStudy),amixedmethods birthcohortofchildrenexposedprenatallytomaternal incarceration.Thisstudyrepresentsauniquedatasetthat includesassessmentsofinfantsofincarceratedandformerly incarceratedmothersandanynon-maternalcaregiversfrom birthuntil12months.Utilizingresponsesfrombothclosed andopen-endedsurveyquestionsfromthisdataset,we conductedalongitudinalanalysisofprimarycaregiving relationshipsoftheseinfantstoanswerseveralresearch questions.First,whocaredforinfantsintheir firstyearof life?Howwerecaregiversrelatedtotheinfant,andwhat sociodemographicriskfactorsweretheyexperiencingwhen theyassumedcareoftheinfant?Second,howoftendid infantsexperienceachangeinprimarycaregivers?Third, whydidanychangesinprimarycaregivingoccur?Finally, werethereanysociodemographicfactorsthatpredicted instabilityinprimarycaregivingrelationships?

Method Participants

Atotalof57infantsandtheirprimarycaregiverswere includedinthisstudy.WhilerecruitmentintheBBBStudy

isoccurringinthreestates(Maine,Pennsylvania,and Georgia),Georgiawaschosenasasingledatasourceasit hadthemostrobustdatacollection.Infantswhosemothers wereincarceratedinprisonorjailinGeorgiaatsomepoint duringtheirgestationwereeligibleforinclusion.Data collectionintheBBBStudyinGeorgiaisongoing,and researcherscurrentlyfollowchildrenuntiltheirthirdbirthday.Thecurrentstudyutilizesassessmentsconductedinthe firstyearofthechild’slifefromchildrenenrolledbetween August2020andMay2023.DatawerecollecteduntilMay 2024.Assessmentswereconductedbetweenbirthandsix weeksofage,andwhenthechildwas3,6,9,and 12monthsold.

Procedures

Thestudyteamapproachedalleligibleinfants ’ primary caregivers,eithermothers,fathers,ordesignatednonmaternalcaregivers,forenrollmentinthestudyduring pregnancyoratthebirthofthechild.Samplingtookplace incollaborationwithMotherhoodBeyondBars(MBB),a nonpro fi torganizationservingincarceratedpregnantand postpartumwomenandtheirfamiliesinthestateof Georgia.MBBstaffapproachedallparticipantsreceiving nonpro fi tservicesforenrollmentinthecohort.Nonmaternalcaregiversofchildrenborntowomenincarceratedinprisonwereapproachedbynonpro fi tstaffatthe birthinghospital.Formerly incarceratedmotherswere approachedbynonpro fi tstaffoverphoneattheirrelease fromprisonorjail.Primarycaregiversof86infantswere approachedduringthestudyperiod.Ofthe29familiesnot retainedinthestudy,eightinfantswereplacedintochild welfarecustodyfrombirthandtheirfosterparents declinedtoparticipate.Theremaining21families declinedtoparticipateorcouldnotbereached.Fiftyseveninfantsandtheirprimarycaregiversenrolledinthe studyand88%ofthesewereretainedinthestudyforone year( fi veinfantswerelosttofollow-upbeforetheir fi rst birthday).

InterviewswereconductedbyBKorbynonpro fitstaffat MBB.Allinterviewersweretrainedinthedatacollection instrumentbyBKandcompletedHumanSubjectsResearch training.Interviewerscollecteddataviaaguidedphoneor videointerviewcontainingapreliminarysemi-structured interviewfollowedbyaquantitativesurvey.Thechild’s currentprimarycaregiverparticipatedineachguided interview.Participantswerecompensated$25aftereach interview.Responsestoclose-endedsurveyquestionswere collecteddirectlyintoHarvardMedicalSchool’sResearch ElectronicDataCapture(RedCAP)system.Interviewswere alsoaudiorecordedandtranscribedverbatimtocapture open-endedquestionresponses.TheHarvardLongwood MedicalIRBapprovedtheBBBStudy(20-1215;21-1247).

Measures

CaregiverSociodemographicCharacteristics

Interviewersaskednon-maternalcaregiverstoidentifytheir relationshiptotheinfant.Fordescriptiveanalyses,we groupedrelationshipsbymothers,fathers,grandparents, othermaternalkin,otherpaternalkin,fosterparent,and non-kin.Wemergediterationsofsteporcommon-law relativeswiththeirrespectiverelativecategories.Two maternalgreatgrandparentswereincludedinthegrandparentcategory.Forlongitudinalanalyses,researchers groupedrelationshipsas “kin,” whichincludedallkinship categories,includingparents,and “non-kin”,whichincludedcaregiverswithnokinshiprelationshipwiththeinfant andfosterparentsnotbiologicallyrelatedtotheinfant. Therewerenoadoptiveparentsinoursample.

Inadditiontothecaregivers’ relationshiptotheinfant, interviewersassessedthefollowingsociodemographic characteristicsatbaseline:primarycaregiver’sage,sex, race/ethnicity,educationalattainment,householdincome, householdsize,andcaregiver’smentalhealth.Toassess educationalattainment,participantswereaskedtoreportthe highestlevelofschoolingtheycompleted.Weselected caregiverrace,poverty,andmentalhealthasimportant potentialpredictorsofinstabilityincaregiving.Allcaregiverseitheridentifi edasBlack/AfricanAmericanorWhite. Duetothedisproportionatechildwelfareinvolvementof Blackfamilies,weincludedidentifyingasBlackasa potentialpredictorofcaregiverinstability.Weclassi fied childrenaslivinginpovertyifthecombinedhousehold incomeandhouseholdsizefellbelowtheFederalPoverty Line(FPL).Specifi cthresholdswereuseddependingonthe yearinwhichtheinterviewoccurred.Interviewersassessed caregiverdistressthroughtheKessler6,a6-itemdistress instrumentwhichusesa5-pointLikertscaleandisscored between0and24(Kessleretal., 2003).TheKessler-6has highinternalvalidityasassessedthroughfactoranalysisand hasbeenvalidatedinavarietyofpopulations(Mewton etal., 2016).Weclassi fiedinfantsaslivingwithaprimary caregiverwithdistressiftherespondentscored5orabove ontheKessler6.Basedonavaliditystudy,scoresof5or aboveontheKessler6areclassifi edasmoderatedistress andscoresof13andaboveasseveredistress(Prochaska etal., 2012)

ChangeinCaregivers

Wedefinedachangeincaregiverasthecessationofcareby apreviouscaregiverthatwasperceivedaspermanentor lastedmorethanonemonth.Wedidnotincludeshortterm ortemporarychangesinprimarycaregivers,suchasrelocationofthechildduetothecaregiver’stime-limitedillness

orcompletionofarehabprogram.Whenaprimarycaregiverchangewasidenti fiedthroughstudyorprogrammatic activities,thestudyteamworkedtoidentifyandenrollnew primarycaregivers.Insomecases,intakeinterviews occurredwhenthechildwas3monthsoldorolder.Inthese instances,interviewerswererequiredtoindicatewhether theparticipanthadcustodyofthechildfrombirth,butcould notbereached,orwhethertheparticipantwasanew caregiverofthechild.Ifthelatterwasindicated,interviewerswererequiredtocompleteanopen-endedresponse detailingthecircumstancesofthechangeincaregiversas describedbytheparticipant.

Toascertainthereasonforchangesincaregivers,participantswereaskedatthebeginningofeachfollowup: “Are youanewcaregiverof[infantname]?” Ifrespondents answeredyes,interviewersthenasked “Whyareyou assumingcareofthischild?” and “Howdidyoubecomethe caregiverof[childname]”?Theageofthechildinmonths whenthenewcaregiverassumedcarewasalsorecorded.If newcaregiversrefusedstudyparticipation,weaskedMBB stafftorecordtheageofthechildinmonthswhenthechild leftthecareoftheirpreviouscaregiverandtherelationship ofthenewcaregivertothechild.

Analyses

CaregiverSociodemographicCharacteristicsatBaseline

Wecalculatedmeans,frequencies,andstandarddeviations (whereappropriate)ofinfantsexandrace/ethnicity;caregiverage,sex,race/ethnicity,relationshiptotheinfant,level ofeducation,andwhethertheyexperiencedpovertyor distressatintake.

PatternsofCaregiving

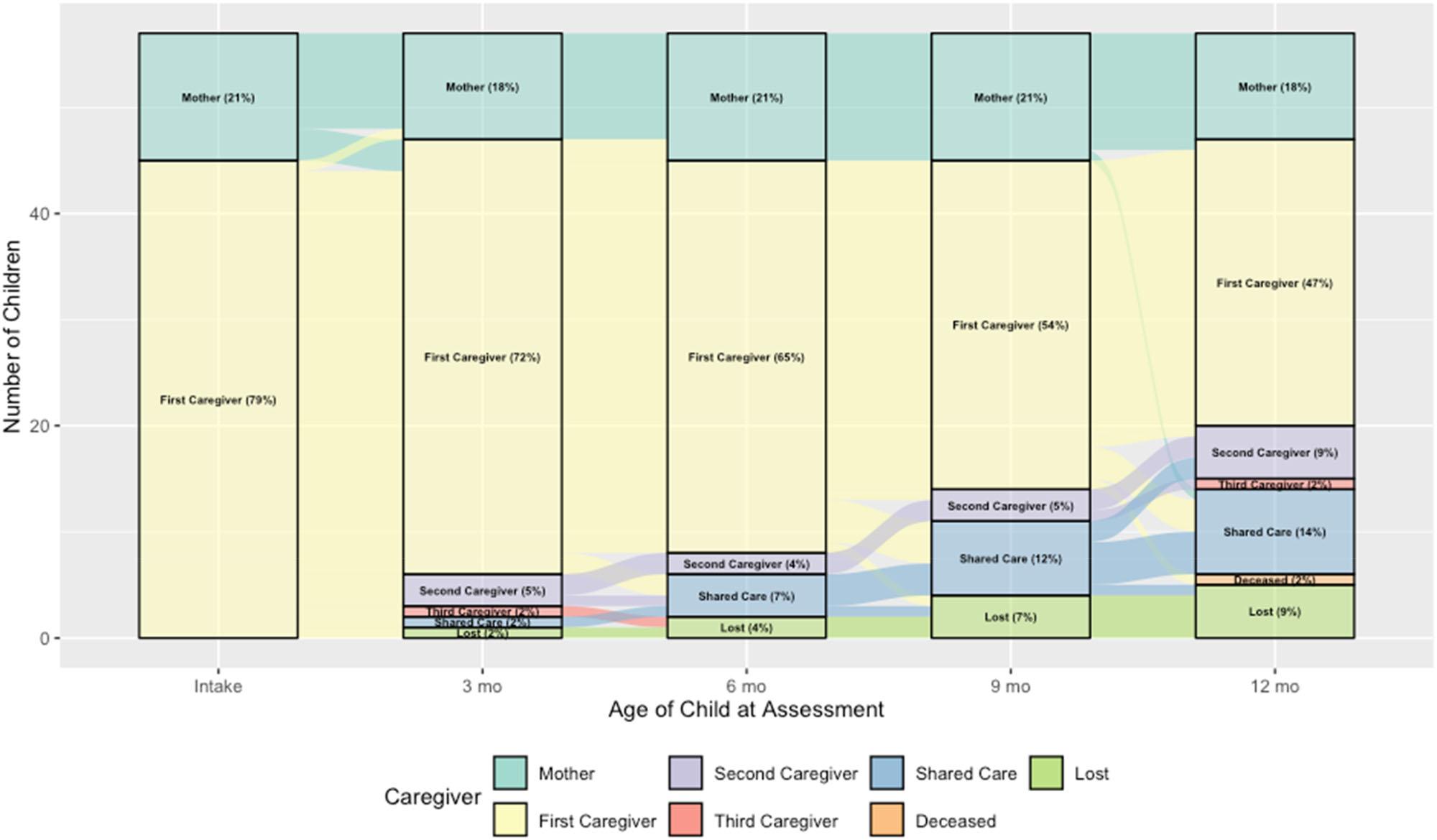

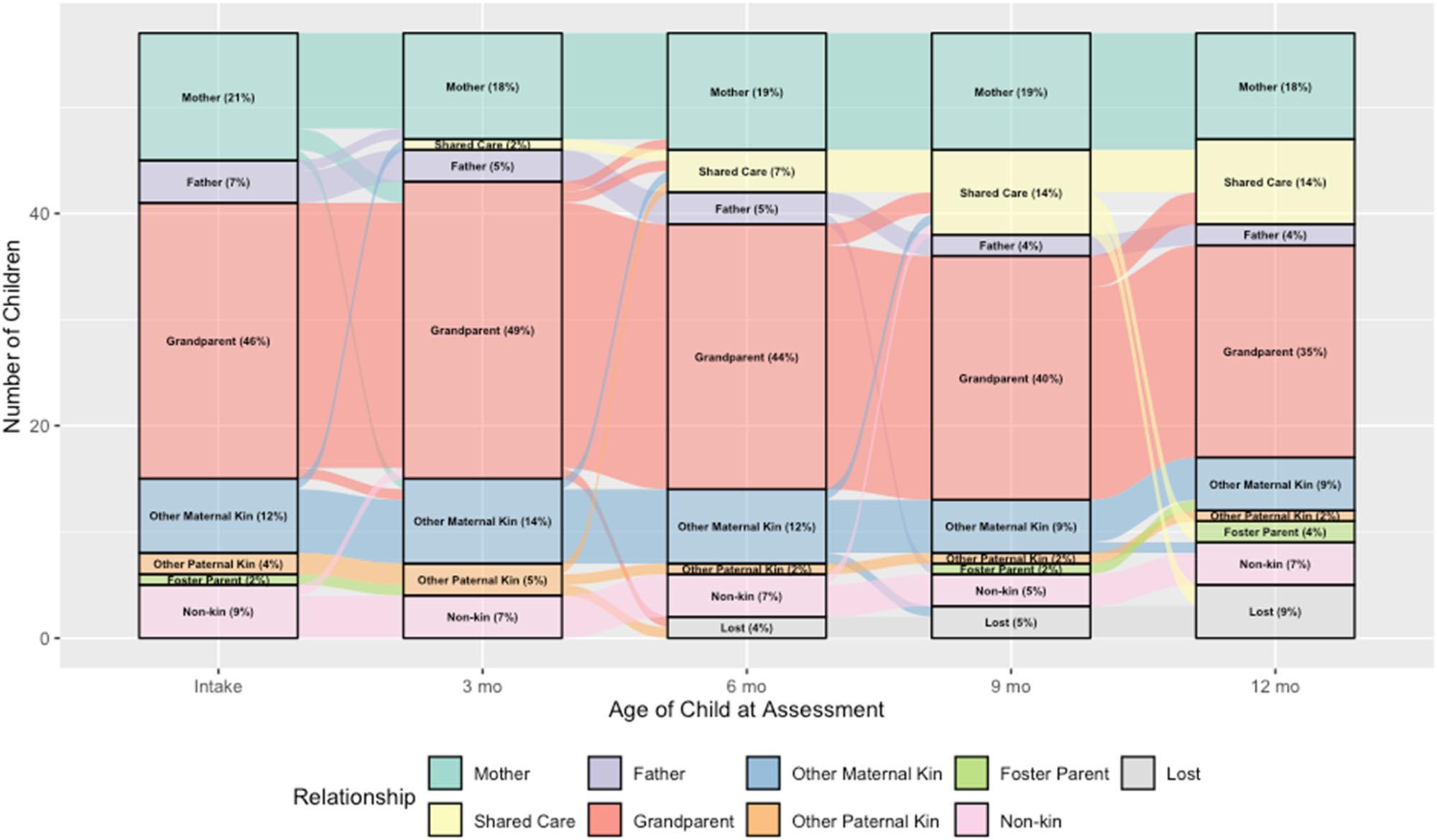

Tounderstandprimarycaregivingrelationshipsovertime, weplottedthetrajectoriesofcaregivingrelationshipsusing alluvialplots.Alluvialplotsusevariablewidthribbonsto visualizechangeincategoricalvariablesinlongitudinaldata (Brunson, 2020).Eachlinerepresentsonechild.Barsat eachtimepointrepresentthenumberofinfantsinthat category. “Flows,” orlinesthatmovefromonecategoryto anotherbetweentimepoints,indicatedinfantsthatmoved caregiversbetweentheassessmentperiods.

First,wecreatedanalluvialplotmappingthenumberof caregivingrelationshipsexperiencedbyeachchild.Inthis alluvialplot,wemappedwhetherchildrenwerebeingcared forbytheirmotheror first,second,orthirdnon-maternal caregiverateachtimepoint.Ifmotherswerereleasedand weresharingcarewiththeirchild’spreviouscaregiver,we denotedthisas “Sharedcare.” Tobetterunderstandthe relationshipsofcaregiverstotheinfantwethenmapped

kinshiprelationshipsofcaregiverstotheinfantovertime.In eachplottoaccountforattritioninfantslosttofollowup wereindicatedbythecategory “Lost.”

CaregiverStability

Toanswerourthirdresearchquestionrelatingtothestabilityofprimarycaregiversinthispopulation,wedescribed childexperiencesofchangeinprimarycaregiversoverthe firstyearoflifeintwoways.First,toquantifytheextentof primarycaregiverinstability,wecalculatedtheincidenceof changeinanyprimarycaregiverbetweenbirthandone year.Wealsocalculatedtheincidenceofchangeinnonmaternalprimarycaregivers.

ReasonsforChangesinCaregiving

Tocharacterizewhychangesinprimarycaregiversoccurred,weconductedatextualanalysisofresponsestothe open-endedquestionsposedtonewprimarycaregivers: “Whyareyouassumingcareofthischild?” And “Howdid youbecomethecaregiverof[childname]”?Wethen assessedrationalesforchangeinprimarycaregiverfortheir abilitytobegroupedintosimilarcategories.

PredictorsofCaregiverStability

Toanswerour fi nalresearchquestiononpredictorsof caregiverstability,weconductedaseriesofCoxproportionalhazardsmodels.Aswewereprimarilyinterestedin caregiverinstabilityduringmaternalincarceration,theevent wasdefinedasa firstchangeinnon-maternalprimary caregivers.Tounderstandpotentialpredictorsofthehazard rateofchangeinprimarycaregiversweran fi vemodels, fourassessingasinglepredictorofexperiencingatleastone disruptioninnon-maternalcaregiversandoneassessinga compositescoreofallfourpotentialpredictors.Totestfor proportionalityofhazards,akeyassumptionoftheCox model,weranaglobalSchoenfeldtestofscaledSchoenfeld residualsforeachmodel(Grambsch&Therneau, 1994).

Predictorswereselectedbasedonaliteraturereviewas wellassubject-matterknowledgeashavinghighlikelihood ofinfluencingwhetheracaregiverchoseorwascompelled torelinquishcareoftheinfant.Potentialpredictorsassessed werea)whetherthecaregiverhadakinshiprelationship withthechild,b)whetherthecaregiverlivedundertheFPL atthebirthofthechild,c)whetherthecaregiverexperiencedmoderateorseveredistressatthebirthofthechild, andd)whetherthecaregiveridenti fiedasBlackorAfrican American.Eachpotentialpredictorwasoperationalizedasa binaryvariable.

Thesemodelsarebasedon656totalperson-months.The medianlengthoffollow-upwas12months.Sixinfants

werecensoredbeforereaching12monthsoffollow-up. Fivecouldnotbereachedforfollow-upinterviews.The averageageinmonthsatwhichinfantswerecensoreddue toattritionwas6.6months.Onechilddiedat11months.

Results

CaregiverSociodemographicCharacteristics

Amongthe57infantsinthesample,themajoritywere female(n = 31,54.4%).Approximatelyhalfoftheinfants wereeitherBlack(n = 20)ormixedrace(BlackandWhite) (n = 8).Oneinfantwasidenti fiedasNativeAmericanor AlaskanNative,andoneinfantwasidenti fiedasBlackand Paci ficIslander.Atbirth,82.5%(n = 47)infantswerecared forbynon-maternalcaregivers.Teninfants(17.5%)were caredforbytheirformerlyincarceratedmothers,allof whomwerereleasedbeforethebirthoftheinfantfromjail. Primarycaregiversweremostlikelytobegrandparentsof theinfant(49.1%, n = 28),primarilymaternalgrandparents (75%).Ninewereotherrelatives(15.8%),again,primarily maternalkin(77.8%).Fourcaregivers(7%)werefathers. Sixcaregivers(10.5%)hadnokinshiprelationshipwiththe infant;oneofwhomwasafosterparent(16.7%),and five (83.3%)werefriendsoracquaintancesofthemother.These includedtwocaregiversthemothermetinjailandwere releasedpriortothebirthofthechildandonestrangerthe mothercontactedafterhearingshewaswillingtotake childrenofincarceratedwomen.

Mostprimarycaregiversidentifi edaswomen(89.5%, n = 51).Theaverageageofprimarycaregiverswas44 years(SD11.5),witharangeof24–71years.Overathird ofcaregiversidentifiedasBlack(38.6%, n = 22),withthe remainingidentifyingasWhite.Seventy fi vepercentof caregivershadahighschooldiplomaorless(n = 43)and overone-third(40.4%)livedundertheFPL(n = 23).Seven caregivers(12.3%)scoredinthemoderateorsevere depressionrangeontheKessler6.SeeTable 1.

CaregiverStability

Changesinprimarycaregiversoccurredwhenachildwas movedfromonenon-maternalcaregivertoanother,whena childwasmovedfromthecareofanon-maternalcaregiver tothesolecareoftheirreleasedmother,andwhenachild whohadbeencaredforbytheirmotherfrombirthwas movedtothecareofanon-maternalcaregiver.Duringthe firstyearofinfants’ lives,15(26.3%)infantsexperiencedat leastoneofthesedisruptionsinprimarycaregiving relationships.

Table1 Participantcharacteristics

Infants(n = 57)

Sex = Female31(54.4%)

Ethnicity = HispanicorLatinx5(8.8%)

Race

White26(45.6%)

BlackorAfricanAmerican21(36.8%)

MixedRace9(15.8%)

Unknown1(1.8%)

PrimaryCaregiversatIntake(n = 57)

RelationshiptotheChild

Mother10(17.5%)

Father4(7.0%)

Grandparent28(49.1%)

Maternal21(75%)

Paternal7(25%)

OtherKin9(15.8%)

Maternal7(77.8%)

Paternal2(22.2%)

Non-kin6(10.5%)

Fosterparent1(16.7%)

Averageage44(SD11.5)

Sex = Female51(89.5%)

Ethnicity

HispanicorLatinx2(3.5%)

Non-HispanicorLatinx53(93%)

Missing2(3.5%)

Race

BlackorAfricanAmerican22(38.6%) White35(61.4%)

EducationalAttainment

Somehighschool,nodegree6(10.5%)

GEDoralternativecredential7(12.3%)

Highschooldegree30(52.6%)

Associateorbachelor’sdegree7(12.3%)

Master’sorprofessionaldegree3(5.3%)

Missing4(7.0%)

LivingUndertheFederalPovertyLine

Yes23(40.4%)

Missing5(8.8%)

ModerateorSevereDistress

Yes7(12.3%)

Missing2(3.5%)

Duringthestudyperiod,sixteenmotherswerereleased fromprison.Themajorityofreleasedmothersreported livingwithandsharingcareoftheinfantwiththeirformer caregiver( n = 11,68.8%).However,fourmothers reportedresumingsolecustodyofthechildontheir release,contributingtothequarterofinfantswho experiencedatleastonechangeinprimarycaregivers.See Table 2

Eleven(19%)infantsexperiencedachangeinprimary caregiverotherthanreuni fi cationwiththeirformerly incarceratedmother,threeofwhichoccurredwhenachild wasintheirmother ’ scarefrombirthandwasmovedtothe careofanon-maternalcaregiverduringthestudyperiod. Fivechildrenexperiencedmorethanonedisruptionin primarycaregiver(7%).

Figure 1 illustratesthenumberofchildrenlivingwiththeir mother,or first,second,orthirdcaregiverduringthe firstyear oftheirlife.Several(n = 5)childrenwerelosttofollowup (indicatedinFig. 1 by “Lost”),andonechilddiedduringthe studyperiod.Thischild’scauseofdeathwasundetermined. Thenumberofchildrenonlyhavingexperiencedoneprimary caregiverdeclinedfrom79–47%betweenbirthandtwelve

Mothersreleasedinthe firstyear(n = 16)

AgeoftheChildatMother’sRelease

Lessthan3months2(12.5%)

4–6months6(37.5%)

7–12months8(50%)

CaregivingArrangementsPost-Release

Mothertooksolecustody4(25%)

Caregiverretainedsolecustody1(6.3%)

Motherandcaregiversharecaregiving11(68.8%)

months,whilethenumberofchildrencaredforbytheirmother (18%by12months)orinasharedcarearrangement(14%by 12months)increasedduringthestudyperiod.By12months, 9%ofchildrenwerelivingwithasecondcaregiverand2% withathirdcaregiver.Figure 2 depictscaregivers’ relationships tothechildinthe firstyear.Grandparentswerethepredominantkinshipcategoryateachtimepoint.Grandparents weremostlikelytolatershare carewiththeformerlyincarceratedmotheronherrelease(seered flowsfrom “Grandparent” to “SharedCare”).Inaddition, flowssuggestthata subsetofchildrenfrequentlymoveintoandoutoffostercare. Thepercentageofchildrenbeingcaredforbytheirmothers decreasedfrom21%atintaketo18%at12months.Carebyall otherkinmembersdecreasedby12months(fathersfrom 7–4%;grandparentsfrom46–35%;othermaternalkinfrom 12–9%;andotherpaternalkinfrom4–2%).Sharedcare betweenthemotherandthechild’snon-maternalcaregiver increasedfromnoneto14%by12months.Childrencaredfor bynon-kincaregiversdecreasedfrom9–7%whilechildren withfosterparentsincreasedfrom2–4%by12months.

ReasonsforChangesinCaregiving

Themostfrequentreasonforachildexperiencingachange fromonecaregivertoanotherwasreuni ficationwitha formerlyincarceratedmother,followedbychildwelfare

Fig.1 Alluvialplotofwhetherchildrenexperiencedtheir first,second, orthirdnon-maternalcaregiver;carefromtheirformerlyincarcerated mother;orsharedcarebetweenaformerlyincarceratedmotherandthe

child’scaregiverduringthemother’sincarcerationateachtimepoint. Childplacementfrombirthtooneyearofageinthebirthbeyondbars cohort, n = 57

Fig.2 Alluvialplotofthekinshiprelationshipofthechild’sprimary caregiver(mother,father,grandparent,othermaternalkin,other paternalkin,non-kin,orfosterparent)ateachtimepoint.Caregiver

removal.Twochildrenenteredfostercareduringthestudy period,andonewasmovedfromonefosterhometoanother fosterhome.Twoofthechildreninchildwelfarecustody experiencedasecondchangeincaregiverwhentheywere movedfromnon-relativefostercaretokinshipcare,andone childexperiencedremovaltochildwelfareaftertheywere informallymovedfromonecaregivertoanother.Theother changesinprimarycaregivingrelationshipsoccurredoutsideoffostercare.Inthreeinstances,non-maternalcaregiverstransitionedachildtoanotherperson’scareafterthey wereunabletocopewiththeircaregivingresponsibilities. Threechildrenwhowereintheirmother’scustodyfrom birthtransitionedtoanon-maternalcaregiveraftertheir motherhadrecurrenceofsubstanceuse,andoneafterthe motherwasreincarcerated.Onecaregiver,theinfant’s grandmother,diedduringthestudyperiod,andtheinfant wasplacedwithanothergrandmother.Anotherinfantwas movedfromacaregiverwithnokinshiprelationshipwith theinfanttotheinfant’sgrandmother’scare,amovethat wasmutuallyagreeduponbyboththe firstandsecond caregiver(seeTable 3).

PredictorsofCaregiverInstability

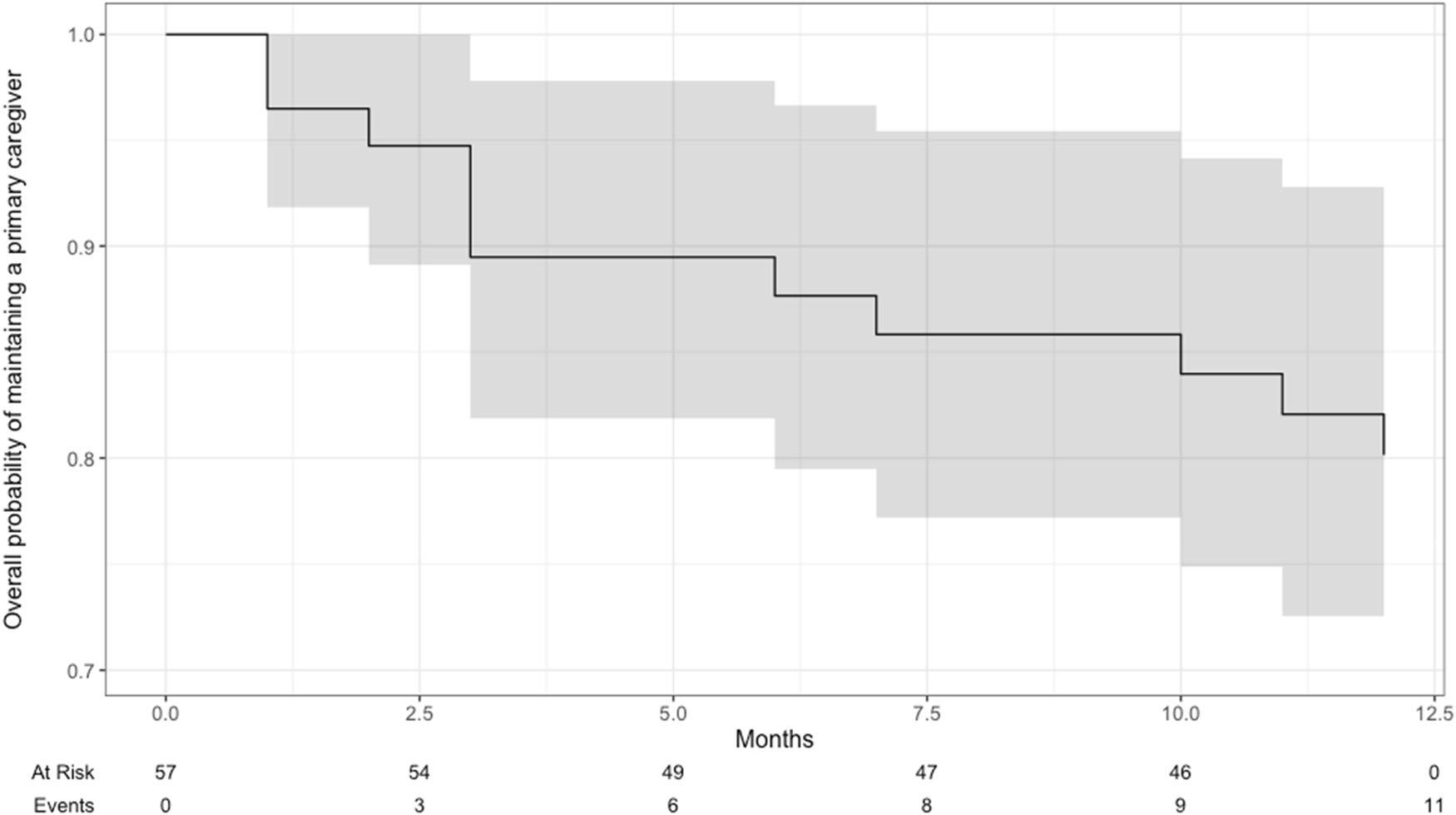

Theprobabilityofmaintainingasingleprimarycaregiverover thestudyperiod,excludingreunificationwiththemother,

relationshiptothechildfrombirthtooneyearofageinthebirth beyondbarscohort, n = 57.

droppedsignificantlyovertime,fallingto80%atthe12-month assessmentwave(seeFig. 3).ResultsfromtheCoxproportionalhazardsmodelssuggestthatplacementwithakinship caregiveratbirthisprotectiveagainstdisruptionsinprimary caregivingrelationships.Comparedtochildrenplacedwith non-kinshipcaregiversatbirth,thoseplacedwithkinhada lowerhazardratioofdisruption inprimarycaregivingof0.18 (95%CI0.05,0.60,p<0.05).Povertywasnotassociatedwith thehazardratioofdisruptioninprimarycaregivingrelationships.Comparedtochildrenwhoseprimarycaregiverswere notlivingundertheFPLatintake,childrenwhoseprimary caregiverswerelivingundertheFPLhadahazardratioof0.37 (95%CI0.08,1.72,p = 0.21).Distresswasalsonotpredictive ofchangeinnon-maternalcaregiving(HR0.44,95%CI0.06, 3.44,p = 0.4).Finally,acompositeriskscorecombiningall fourfactorswasalsonotpredictiveofchangeinnon-maternal caregiving(HR0.88,95%CI0.44,1.73,p = 0.71).Allmodels exceptthemodelincludingpoverty(p = 0.048)hadnonsignificantp-valuesontheSchoenfeldtest,suggestingthat hazardrateswereproportionalacrossfollow-up.SeeTable 4

Discussion

Toourknowledge,thisisthe firststudytoprospectively assesscaregivingstabilityforchildrenexposedprenatallyto

Table3 Reasonschildreninthe birthbeyondbarscohort changedprimarycaregiversin the firstyear

From1st–2ndCaregiver(n = 15)From2nd–3rdCaregiver(n = 4)

Formerlyincarceratedmotherresumedsolecare4Movedfromfostercaretokinshipcare2 Informallymovedtoanotherfamilymoreableto takeoncareresponsibilities

3Informallymovedtoanotherfamilymoreableto takeoncareresponsibilities

1

Removedtochildwelfarecustody2Removedtochildwelfarecustody1

Movedfromastranger’scaretograndparent’scare1

Movedtoanothergrandparentafterthe firstdied1

Movedtoanotherfosterparent1

Fig.3 KaplanMeierCurvedescribingtheprobabilityofmaintaininga primarycaregiverateachtimepoint.Confidenceintervalsaredisplayedingray.Thenumberofchildrenatriskandthenumberof

Table4 Coxproportionalhazardsmodelsofdisruptioninnonmaternalcaregiving(n = 57)

Explanatory variable Hazard ratio 95%CIp-valueLikelihood RatioTest

Poverty0.370.08,1.720.211.92,p = 0.2

Kinship0.18**0.052,0.60.0056.3,p = 0.01

Distress0.440.06,3.440.430.77,p = 0.4

Race(Blackor white) 0.680.20,2.310.530.4,p = 0.5

CompositeRisk Score 0.880.44,1.730.710.14,p = 0.7

Eachrowofthistablerepresentsaseparatelyrunmodel.

maternalincarcerationinthe fi rstyearoflifeoutsideofa prisonnurserysetting.Thisstudyfoundthatduringinfancy, acriticalperiodforthedevelopmentofattachmentrelationships,infantsfrequentlyexperiencedchangesincaregivingrelationships,primarilycausedbychildwelfare

eventsateachtimepointaredisplayedundertheplot.Kaplainmeier curveoftheprobabilityofmaintainingasingleprimarycaregiverin the firstyear

involvement.Whilecaregiversociodemographicriskfactorsdidnotpredictinstabilityinnon-maternalcaregiving, thecaregiver’skinshiprelationshiptotheinfantwasprotectiveofdisruptionsinprimarycaregivingrelationships.

Our findingscorroboratedPendletonetal.’sretrospective study,whichfoundthatcaregiversofchildrenbornto incarceratedmotherswerepredominatelygrandparentsor otherrelativesoftheinfant(2021).Inourstudy,fathersand fosterparentswereleastlikelytobetheprimarycaregivers ofinfantsinoursample.However,inthecaseoffoster parents,thisislikelyduetoselectionbias.Descriptive analysesrevealedthatgrandparentsfrequentlysharedcare withtheinfant’smotheronherrelease.Thismaybea particularlybeneficialstrategyforthemotherandherchild, allowingthemotherdedicatedtimetopursuetreatmentfor substancedependence,applyforjobs,andadjusttoher childcareresponsibilities,whilegivingthechildatransition periodbetweentheirtemporarycaregiverandtheirmother.

Whilewewereunabletoassesschilddevelopmentaloutcomes,ourresultsindicatethatgrandparentalcaremaybe protectiveofthemother’sroleinthefamilyinthecontextof maternalincarceration.

Reasonsforchangesinprimarycaregivingunrelatedto thereleaseoftheinfant’smotherwerediverse.Indeed,we identi fiedsevenseparatecausesfora firstmovefromone primarycaregivertoanother,sixofwhichwereunrelatedto thereleaseofthemother.Childwelfarerelatedcauseswere themostcited,particularlyinthecaseofasecondchangein primarycaregiver.Childwelfareremovalisacomplex phenomenon.Itisdif ficulttodisentanglethedevelopmental effectsofabuseorneglectfromthosecausedbythechild’s removalfromfamily(Doyle, 2013).However,researchers havehypothesizedthatthefrequentmovesassociatedwith childwelfareinvolvementmayatleastpartiallyexplainthe pooroutcomesassociatedwithfostercare(Doyle, 2013; Jacobsenetal., 2020;Newtonetal., 2000).Whenchildren areremovedfromfamilies,thereisevidencethatkinship careismoreprotectivetochildoutcomes,includingbehaviorandconnectedness,thannon-kinshipfostercare (Hassalletal., 2021;Winokuretal., 2014).Severalchildren inourstudywhowereinitiallymovedduetochildwelfare experiencedasecondmoveintokinshipcare.Itisunclear howmultiplemovementandkinshipcareinteracttopredict childoutcomes.

Furthercomplicatingthepicture,someadvocateshave arguedthatchildwelfareremovalmaybepartiallymotivatedbythedesiretopoliceminoritizedfamiliesratherthan tosupportthemincaringforchildren(Sankaranetal., 2019;Roberts, 2022).Likemassincarceration,thereis evidencethatchildwelfareinvolvementisfrequentlya resultoffamilies’ poverty(Huntington, 2007;Raz, 2017; Roberts, 2022).Evidencealsoconsistentlypointstoracial targeting,particularlyofBlackandIndigenousfamilies (Edwardsetal., 2021;Kimetal., 2017;Roberts, 2008; Roberts, 2022;Wildeman&Emanuel, 2014),inthechild welfaresystems.However,inthisstudy,acaregiver’sselfreportedracialidentitywasnotpredictiveofdisruptionsin primarycaregiving.Whilethisstudywasunabletoascertainwhychildwelfareremovaloccurred,moreresearchis neededtofullyunderstandthecomplexinterplaybetween maternalincarceration,caregiving,andchildwelfare involvement.

Inadditiontoformalizedchildwelfareremoval,we foundthatinfantsfrequentlyexperiencedinformalchanges incare.Inmostcases,theseinformalmovementswere describedasoccurringbecauseofthe firstcaregiver’s strugglestocarefortheinfant.Bothstudiesincaregiversof olderchildrenofincarceratedmothersandourownqualitativeresearch(Kotlaretal., 2024)havefoundthatcaregiversreportstrugglingwithphysicalhealth,mentalhealth, and financialwellbeingasadirectresultofcaregiving(Cox

&Wallace, 2013;Pendletonetal., 2021;Shaw, 2023). Despitethesedescriptive findingsandastrongtheoretical rationaleforselectingthesepredictors,povertyandcaregivermentalhealthatbaselinedidnotpredicttheriskofa firstchangeincaregivers.Theremaybeseveralreasons whywedidnotdetectaneffectinthecasethatoneexists. First,becauserationalesforchangesinprimarycaregiving weresodiverse,predictorsmayalsodependontheimpetus foreachmove.Especiallyifthiswerethecase,butalso generally,wemayhavebeenunderpoweredtodetect smallereffectsizes(only11 firstchangesinnon-maternal caregiversoccurredduringthestudyperiod).Second,there maybealagbetweenassumingcareofanewbornandany impactsofacaregivers ’ fi nancialormentalhealth,inwhich casemeasuringtheseriskfactorsatbaselineisnotproximal enoughtotheeventitselftobeausefulpredictor.Said differently,caregivers’ financialstatusand/ortheirmental healthmayhavedeclinedovertime – ultimatelycontributingtotheneedtomakeachangeincaregiving arrangements.Finally,othermeasuressuchasparenting stress,socialsupport,orneighborhoodcohesionmayhave beenmoreappropriatepredictorsof firstchangeincaregivers.Futurestudiesshouldcarefullyassesstheroleof sociodemographicriskfactorsoncaregiverinstability overtime.

Ouranalysesdiddetectastrongprotectiveeffectof beingplacedwithakinshipcaregiveratbirth,includinga formerlyincarceratedmother,ondisruptionsinprimary caregiving.These findingsaddtotheliteraturethatsuggests thatkinshipcareinthecontextofmaternalincarceration mayleadtomorefamilyconnectednessandcohesion, whichinturncanleadtomoreoptimalchildoutcomes (Bakeretal., 2010;Loper&Clarke, 2013).Theseresults alsopointtothetenuousnatureoftherelationshipbetween infantsandnon-kinshipcaregiversinoursample.Results fromourqualitativestudyofcaregiverrelationshipformationinthesamesamplefoundthatmotherstypicallychoose caregiversnotrelatedtotheinfantonlywhenallothernonfostercareoptionshavebeenexhausted(Kotlaretal., 2025).Indeed,threecaregiversinthiscategorydidnot knowthemotheratall,oronlyknewherforseveralmonths beforeassumingcareoftheinfant.Thissuggeststhata mother’srelationshiptoherinfant’scaregiverand/orthe caregiver’srelationshiptotheinfantmaybeapowerful motivatorinretainingcustody.

Theseresultshaveseveralimplicationsforchildwellbeing.First,theyprovidepreliminaryevidencethatinterruptedattachmentrelationshipsareaconsequenceof maternalincarcerationandthusmayindeedbeamediator betweenmaternalincarcerationandchilddevelopmental outcomes.Futureresearchshouldassesstherelationship betweenchangesinprimarycaregivingandattachment relationshipsasanoutcomeinthispopulation.Inaddition,

our findingssuggestthatchildrenborntoincarcerated mothersfrequentlyexperiencechildwelfareinvolvement. Whilethereisnotyetenoughevidenceonwhichtobase policyrecommendationsrelatedtochildwelfareforthis population,itisessentialthatresearchersandpolicymakers continuetoconsiderthewaysinwhichcyclesofcriminal legalandchildwelfaresysteminvolvementmaycontribute tonegativedevelopmentaloutcomesforchildren.Finally, whilestatisticalmodelsdidnotcorroboratearelationship betweencaregiversociodemographicfactorsatbaselineand changesincaregivers,descriptiveresultssuggestthat caregiversfrequentlyfeltoverwhelmedbytheresponsibility ofcaringforthenewbornofanincarceratedmother.We urgestatelawmakerstoconsiderprioritizingcaregiversof childrenwithincarceratedparentsforsocialsupportprogrammingtolessentheburdenplacedoncaregivers (Mihalec‐Adkins&Shlafer, 2022;Kotlaretal., 2024).

Limitations

Thisstudywaslimitedinseveralways.First,datacollection wasconstrainedtoasinglestate,limitingthegeneralizabilityofourresults.However,ourresultsprovidekey dataonprenatalexposuretomaternalincarcerationinthe SouthernU.S.,aregionwithhighwomen’sincarceration rates.Second,despiteahighbaselineresponse,therewas evidenceofselectionbiasduetotheunderenrollmentof childrenplacedfrombirthintochildwelfarecustody.The limitedenrollmentofchildrenplacedintothecustodyof childwelfareagenciesatbirthlikelymeansourresults underestimatetheincidenceofchangesinprimarycaregiversinthispopulation.

Conclusion

Thisstudyfoundthatchildrenborntoincarceratedmothers experiencedhighlevelsofinstabilityinprimarycaregivers. Instabilityinprimarycaregiverswasprimarilydrivenby childwelfareengagement,whilekinshipcare,particularly grandparentalcare,wasprotectiveagainstinstability.These findingsindicatethatstabilityinprimarycaregivingrelationshipsmayplayanimportantroleinthepathwayfrom maternalincarcerationduringinfancytochilddevelopmentaloutcomes.

AuthorContributions BethanyKotlarwasprimarilyresponsiblefor thestudyconceptionanddesignincollaborationwithallcoauthors. Materialpreparation,datacollection,andanalysiswereperformedby BethanyKotlar.The firstdraftofthearticlewaswrittenbyBethany Kotlar.AlexKotlarwastheleadonsoftwareandvisualization.All authorscommentedonpreviousdraftsandreviewedthe finaldraftof thearticle.

JournalofChildandFamilyStudies

Funding ThisprojectwaspartiallyfundedbytheHRSACenterof ExcellenceinMCHgrant,T03MC07648-12-06.BethanyKotlar’s workonthisprojectwasfundedbytheReproductivePerinataland PediatricEpidemiologyFellowship,T32HD104612.

CompliancewithEthicalStandards

ConflictofInterest Thereareno financialconflictsofinterestto declare.BethanyKotlarservedasanunpaidBoardmemberfor MotherhoodBeyondBarsfrom2019until2022.

EthicsApproval ThisstudywasapprovedbyHarvardLongwoodMedicalArea’sInstitutionalReviewBoardthroughIRB20-1215;21-1247.

InformedConsent Studyparticipantscompletedaninformedconsent processandconsentedtopublicationofunidenti fiabledata.

References

Alexander,M.(2012). ThenewJimCrow:Massincarcerationinthe ageofcolorblindness (Revisededition.).TheNewPress. Arditti,J.A.,Lambert-Shute,J.,&Joest,K.(2003).Saturdaymorning atthejail:Implicationsofincarcerationforfamiliesandchildren. FamilyRelations, 52(3),195–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17413729.2003.00195.x

Arditti,J.A.(2005).FamiliesandIncarceration:AnEcological Approach. FamiliesinSociety, 86(2),251–260. https://doi.org/ 10.1606/1044-3894.2460

Baker,J.,McHALE,J.,Strozier,A.,&Cecil,D.(2010). Mother–Grandmothercoparentingrelationshipsinfamilieswith incarceratedmothers:Apilotinvestigation. FamilyProcess, 49(2), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01316.x. Bowlby,J.(1999).Attachment. AttachmentandLoss (vol1,2nd edition).BasicBooks. Bronfenbrenner,U.(1979). Theecologyofhumandevelopment: Experimentsbynatureanddesign.(HarvardUniversityPress. Brunson,J.C.(2020).ggalluvial:Layeredgrammarforalluvialplots. JournalofOpenSourceSoftware, 5(49),2017. https://doi.org/10. 21105/joss.02017

Byrne,M.W.,Goshin,L.S.,&Joestl,S.S.(2010).Intergenerational transmissionofattachmentforinfantsraisedinaprisonnursery. Attachment&HumanDevelopment, 12(4),375–393. https://doi. org/10.1080/14616730903417011

Byrne,M.W.,Goshin,L.S.,&Blanchard-Lewis,B.(2012).Maternal separationsduringthereentryyearsfor100infantsraisedina prisonnursery:Maternalseparationsduringthereentryyears. FamilyCourtReview, 50,77–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17441617.2011.01430.x

Carson,A.,Kluckow,R.(2023). Prisonersin2022-StatisticalTables (305125;Prisoners).BureauofJusticeStatistics. https://bjs.ojp. gov/document/p22st.pdf

Cox,R.,&Wallace,S.(2013).Theimpactofincarcerationonfood insecurityamonghouseholdswithchildren. IDEASWorking PaperSeriesfromRePEc https://ffcws.princeton.edu/sites/g/ files/toruqf4356/ files/documents/wp13-05-ff.pdf

Dallaire,D.H.,Zeman,J.L.,&Thrash,T.M.(2015).Children’s experiencesofmaternalincarcerationspecificrisks:Predictionsto psychologicalmaladaptation. JournalofClinicalChildand AdolescentPsychology:TheOfficialJournalfortheSocietyof ClinicalChildandAdolescentPsychology,AmericanPsychologicalAssociation,Division53, 44(1),109–122. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/15374416.2014.913248

Doyle,J.J.(2013).Causaleffectsoffostercare:Aninstrumentalvariablesapproach. ChildrenandYouthServicesReview, 35(7), 1143–1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.03.014

Edwards,F.,Wakefield,S.,Healy,K.,&Wildeman,C.(2021). Contactwithchildprotectiveservicesispervasivebutunequally distributedbyraceandethnicityinlargeUScounties. ProceedingsoftheNationalAcademyofSciences-PNAS, 118(30),1. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2106272118 Fair,H.,&Walmsley,R.(2022).WorldFemaleImprisonmentList. WorldPrisonBrief. https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/ files/resources/downloads/world_female_imprisonment_list_5th_ edition.pdf

Ferszt,G.G.,&Clarke,J.G.(2012).HealthCareofPregnantWomen inU.S.StatePrisons. JournalofHealthCareforthePoorand Underserved,23(2),557–569. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2012. 0048

Glaze,L.,&Maruschak,L.(2008). ParentsinPrisonandTheirMinor Children.25. https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/parentsprison-and-their-minor-children-survey-prison-inmates-2016 Grambsch,P.M.,&Therneau,T.M.(1994).Proportionalhazards testsanddiagnosticsbasedonweightedresiduals. Biometrika, 81(3),515–526. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/81.3.515 Hassall,A.,JansevanRensburg,E.,Trew,S.,Hawes,D.J.,& Pasalich,D.S.(2021).DoesKinshipvs.Fostercarebetterpromoteconnectedness?Asystematicreviewandmeta-analysis. ClinicalChildandFamilyPsychologyReview, 24(4),813–832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-021-00352-6

Howard,D.L.,Strobino,D.,Sherman,S.G.,&Crum,R.M.(2010). MaternalIncarcerationDuringPregnancyandInfantBirthweight. MaternalandChildHealthJournal, 15(4),478–486. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10995-010-0602-y

Huntington,C.(2007).Mutualdependencyinchildwelfare. TheNotre DameLawReview, 82(4),1485.

Jacobsen,H.,Bergsund,H.B.,Wentzel-Larsen,T.,Smith,L.,&Moe, V.(2020).Fosterchildrenareatriskfordevelopingproblemsin social-emotionalfunctioning:Afollow-upstudyat8yearsofage. ChildrenandYouthServicesReview, 108,104603. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104603

Jensen,R.(2021).PregnancyDuringIncarceration:A “Serious” MedicalNeed. BrighamYoungUniversityLawReview, 46(2), 529–569.

Kessler,R.C.,Barker,P.R.,Colpe,L.J.,Epstein,J.F.,Gfroerer,J. C.,Hiripi,E.,Howes,M.J.,Normand,S.-L.T.,Manderscheid,R. W.,Walters,E.E.,&Zaslavsky,A.M.(2003).Screeningfor seriousmentalillnessinthegeneralpopulation. Archivesof GeneralPsychiatry, 60(2),184–189. https://doi.org/10.1001/a rchpsyc.60.2.184.

Kim,H.,Wildeman,C.,Jonson-Reid,M.,&Drake,B.(2017).LifetimeprevalenceofinvestigatingchildmaltreatmentamongUS children. AmericanJournalofPublicHealth(1971), 107(2), 274–280. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303545

Knight,M.,&Plugge,E.(2005).Theoutcomesofpregnancyamong imprisonedwomen:Asystematicreview. BJOG:AnInternationalJournalofObstetricsandGynaecology, 112(11), 1467–1474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00749.x

Kotlar,B.,Dawson,K.,Odayar,V.,Mason,E.,&Tiemeier,H. (2024). “Howamigoingtodoit?” Understandingthechallenges ofassumingcareofachildbornduringtheirmothers’ incarceration. HealthEquity, 8(1),731–737. https://doi.org/10.1089/ heq.2024.0098

Kotlar,B.,Yousafzai,A.,Sufrin,C.,Jimenez,M.,&Tiemeier,H. (2025). “Thesystem’snotgettingmygrandchild”:Aqualitative studyofcaregiverrelationshipformationforchildrenbornto incarceratedmothers. SocialScience&Medicine, 370,117881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2025.117881

Kotlar,B.,Kornrich,R.,Deneen,M.,Kenner,C.,Theis,L.,Von Esenwein,S.,&Webb-Girard(2015).Meetingincarcerated women’sneedsforpregnancy-relatedandpostpartumservices. PerspectivesonSexualandReproductiveHealth, 47(4),221–225. Loper,A.B.,&Clarke,C.N.(2013).ATTACHMENTREPRESENTATIONSOFIMPRISONEDMOTHERSASRELATED TOCHILDCONTACTANDTHECAREGIVINGALLIANCE: THEMODERATINGEFFECTOFCHILDREN’SPLACEMENTWITHMATERNALGRANDMOTHERS. Monographs oftheSocietyforResearchinChildDevelopment,78(3),41–56. JSTOR.

Maruschak,L.M.,Bronson,J.,&Alper,M.(2021). Parentsinprison andtheirminorchildren:SurveyofPrisoninmates,2016 (pp.8. U.S.DepartmentofJustice.

Mewton,L.,Kessler,R.C.,Slade,T.,Hobbs,M.J.,Brownhill,L., Birrell,L.,Tonks,Z.,Teesson,M.,Newton,N.,Chapman,C., Allsop,S.,Hides,L.,McBride,N.,&Andrews,G.(2016).The psychometricpropertiesoftheKesslerPsychologicalDistress Scale(K6)inageneralpopulationsampleofadolescents. PsychologicalAssessment, 28(10),1232–1242. https://doi.org/10. 1037/pas0000239

Mihalec‐Adkins,B.P.,&Shlafer,R.(2022).Theroleofpolicyin shapingandaddressingtheconsequencesofparentalincarcerationforchilddevelopmentintheUnitedStates. SocialPolicy Report, 35(3),1–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/sop2.25

Murray,J.,&Murray,L.(2010).Parentalincarceration,attachment andchildpsychopathology. Attachment&HumanDevelopment, 12(4),289–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/14751790903416889 Newton,R.R.,Litrownik,A.J.,&Landsverk,J.A.(2000).Children andyouthinfostercare:Disentanglingtherelationshipbetween problembehaviorsandnumberofplacements. ChildAbuse& Neglect, 24(10),1363–1374. https://doi.org/10.1016/S01452134(00)00189-7

Pendleton,V.E.,Schmitgen,E.M.,Davis,L.,&Shlafer,R.J.(2021). CaregivingArrangementsandCaregiverWell-beingwhenInfants areBorntoMothersinPrison. JournalofChildandFamily Studies.Advanceonlinepublication https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10826-021-02089-w

Pettit,B.,&Western,B.(2004).MassImprisonmentandtheLife Course:RaceandClassInequalityinU.S.Incarceration. AmericanSociologicalReview, 69(2),151–169. https://doi.org/10. 1177/000312240406900201.

Poehlmann,J.(2005b).Representationsofattachmentrelationshipsin childrenofincarceratedmothers. ChildDevelopment, 76(3), 679–696.

Poehlmann,J.(2005a).Children’sfamilyenvironmentsandintellectualoutcomesduringmaternalincarceration. JournalofMarriage andFamily, 67(5),1275–1285.

Poehlmann,J.,Shlafer,R.J.,Maes,E.,&Hanneman,A.(2008). Factorsassociatedwithyoungchildren’sopportunitiesfor maintainingfamilyrelationshipsduringmaternalincarceration. FamilyRelations, 57(3),267–280.

Poehlmann-Tynan,J.,&Eddy,J.M.(2019).AResearchandInterventionAgendaforChildrenwithIncarceratedParentsandTheir Families(J.M.Eddy&J.Poehlmann-Tynan,Eds.;pp.353–371). SpringerInternationalPublishingAG. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-3-030-16707-3_24.

Prochaska,J.J.,Sung,H.-Y.,Max,W.,Shi,Y.,&Ong,M.(2012). ValiditystudyoftheK6scaleasameasureofmoderatemental distressbasedonmentalhealthtreatmentneedandutilization. InternationalJournalofMethodsinPsychiatricResearch, 21(2), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1349.

Raz,M.(2017).Unintendedconsequencesofexpandedmandatory reportinglaws. Pediatrics(Evanston), 139(4),1. https://doi.org/ 10.1542/peds.2016-3511

Roberts,D.E.(2008).Theracialgeographyofchildwelfare:Towarda newresearchparadigm. ChildWelfare, 87(2),125–150. Roberts,D.E.(2022). Tornapart:Howthechildwelfaresystem destroysBlackfamilies andhowabolitioncanbuildasafer world.Firstedition.BasicBooks.

Roberts,D.E.(1997).Killingtheblackbody:Race,reproduction,and themeaningofliberty(1sted.).PantheonBooks. RodriguezCarey,R.(2019). “Who’sgonnatakemybaby?”:Narrativesofcreatingplacementplansamongformerlypregnant inmates. Women&CriminalJustice, 29(6),385–407. https://doi. org/10.1080/08974454.2019.1593919

Sadler,M.(2021).PolicingtheWomb.InvisibleWomenandthe CriminalizationofMotherhood. EstudiosPúblicos, 161, 199–206. https://doi.org/10.38178/07183089/1738200619

Sandiford,F.(2007).Doingtimetogether:Loveandfamilyinthe shadowofprison. LibraryJournal, 132(20),140–140. Sankaran,V.,Church,C.,&Mitchell,M.(2019).Acureworsethan thedisease?Theimpactofremovalonchildrenandtheirfamilies. Marquettelawreview, 102(4),1161.

Schuengel,C.,Oosterman,M.,&Sterkenburg,P.S.(2009).Childrenwith disruptedattachmenthistories:Interventions andpsychophysiological indicesofeffects. ChildandAdolescentPsychiatryandMental Health, 3(1),26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-3-26

Shaw,M.(2023).Financialstrain,thetransferenceofstigma,and residentialinstability:Aqualitativeanalysisofthelong‐term effectsofparentalincarceration. FamilyRelations, 72(4), 1773–1789. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12763

Shlafer,R.J.,Stang,J.,Dallaire,D.,Forestell,C.A.,&Hellerstedt,W. (2017).BestPracticesforNutritionCareofPregnantWomenin Prison. JournalofCorrectionalHealthCare, 23(3),297–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345817716567

Sufrin,C.,Jones,R.K.,Mosher,W.D.,&Beal,L.(2020).Pregnancy PrevalenceandOutcomesinU.S.Jails. ObstetricsandGynecology(NewYork.1953), 135(5),1177–1183. https://doi.org/10. 1097/AOG.0000000000003834

Sufrin,C.,Beal,L.,Clarke,J.,Jones,R.,&Mosher,W.D.(2019). PregnancyoutcomesinUSPrisons,2016–2017. American JournalofPublicHealth, 109(5),799–805. https://doi.org/10. 2105/AJPH.2019.305006

Testa,A.,&Jackson,D.B.(2020).IncarcerationExposureDuring PregnancyandInfantHealth:ModerationbyPublicAssistance. TheJournalofPediatrics, 226,251–257.e1. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.jpeds.2020.06.055

Vitagliano,J.,Shalev,T.,Saunders,J.B.,Mason,E.,Stang,J., Shlafer,R.,&Kotlar,B.(2024).ForgottenFundamentals:A ReviewofStateLegislationonNutritionforIncarceratedPregnantandPostpartumPeople. JournalofCorrectionalHealth Care, https://doi.org/10.1089/jchc.23.07.0063

Wildeman,C.,&Emanuel,N.(2014).Cumulativerisksoffostercare placementbyage18forU.S.children,2000–2011. PLoSONE, 9(3), e92785–e92785. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092785

Winokur,M.,Holtan,A.,Batchelder,K.E.&Winokur,M.(2014). Kinshipcareforthesafety,permanency,andwell-beingof childrenremovedfromthehomeformaltreatment. Cochrane DatabaseofSystematicReviews, 2014(1),CD006546. https://doi. org/10.1002/14651858.CD006546.pub3

Zeng,Z.(2023). JailInmatesin2022-StatisticalTables (304888;Jail Inmates).BureauofJusticeStatistics. https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/ ji22st.pdf

Publisher’snote SpringerNatureremainsneutralwithregardto jurisdictionalclaimsinpublishedmapsandinstitutionalaffiliations.

SpringerNatureoritslicensor(e.g.asocietyorotherpartner)holds exclusiverightstothisarticleunderapublishingagreementwiththe author(s)orotherrightsholder(s);authorself-archivingoftheaccepted manuscriptversionofthisarticleissolelygovernedbythetermsof suchpublishingagreementandapplicablelaw.