JournalofChildandFamilyStudies

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-025-03120-0

I’llmakesureheknowsyou:Amixedmethodsstudyofcaregiver facilitatedcontactbetweenincarceratedpostpartummothersand theirinfants

B.Kotlar 1 ● K.Piontkowski2 ● J.Lao2 ● H.Tiemeier2 ● J.Poehlmann3

Accepted:16July2025

©TheAuthor(s),underexclusivelicencetoSpringerScience+BusinessMedia,LLC,partofSpringerNature2025

Abstract

Anestimated1000birthsoccurtoU.S.womenincarceratedinprisonseachyear.Inmostcases,newbornsareseparatedfrom theirincarceratedmothersatbirthandplacedwithnon-maternalcaregivers.Althoughinfantsrequirefrequenttouchand interactiontoformattachments,separationafterbirthprecludessuchconnections.Moreover,frequentlyusedmethodsof contactbetweenincarceratedmothersandtheirchildren,likelettersandphonecalls,areinadequatetobuildattachments. Whilestudieshaveassessedcontactbetweenincarceratedmothersandtheirolderchildren,nonehavecharacterizedcontact betweenincarceratedwomenandtheirnewborns.Thegoalofthisstudywastodescribecontactbetweenincarcerated womenandtheirinfants(frombirthuntil4months)andidentifybarrierstocontacttoinformpoliciesthatwouldpromote developmentallyappropriatecontactduringinfancy,asensitiveperiodforbondingandattachment.Datawerecollectedfrom 39caregiversofchildrenborntoincarceratedmothersinGeorgiawhoareparticipatinginanongoingbirthcohortstudy.We extractedcommunications-relatedquantitativeandqualitativedatafrominterviewsatintakeandwhenchildrenwere betweenthreeandfourmonthsold.Resultsindicatedthatnoinfantsunderfourmonthsvisitedtheirmother.BarrierstoinpersonvisitingwereCOVID-19relatedpolicies,distancefromthefacility,andbeingontheapprovedvisitorlist.Themost frequentmethodofcontactwasphonecalls(85%).Twokeythemesemergedfromqualitativedatathatfurthercharacterized caregivers’ experienceswithcommunication: “Mothers’ desireforconnectionandcollaboration” and “Caregivers’ strategies forresilienceinthefaceofbarriers. ” Whilebothmothersandcaregiversdesiredmother/infantcontactandworkedto establishit,institutionalbarriersweresignificant.Thequalityofcontactbetweenincarceratedpostpartumwomenandtheir infantswasinadequatetofacilitateattachmentrelationships.Policiesandprogramsshouldfacilitatedevelopmentally appropriatevisits.

Keywords Incarceration ● Attachment ● Mother-infantinteractions ● Postpartumwomen

Highlights

● Infancyisasensitiveperiodforthedevelopmentofattachment.Infantsofincarceratedmothersareathighriskofnot forminganattachmentrelationshipwiththeirmothers.

● Thisstudyutilizedamixedmethodsapproachtocharacterize39infants’ contactwiththeirmothersincarceratedinprison inGeorgia.

● Despiteadesirebymothersandthecaregiversoftheirchildrentofacilitatecontact,noinfantsvisitedtheirincarcerated mothers.

● Barrierstovisitsincludedalengthyapprovalprocess,COVID-19relatedvisitingpolicies,anddistancetothefacility.

● Criminallegalreformisneededtoreduceincarcerationduringthepostpartumperiodandprisonsshouldreformvisiting policies.

* B.Kotlar bkotlar@hsph.harvard.edu

1 HarvardGraduateSchoolofArtsandSciences,Cambridge,MA, USA

2 HarvardT.H.ChanSchoolofPublicHealth,Boston,MA,USA

3 UniversityofWisconsin-Madison,SchoolofHumanEcology, Madison,WI,USA

TheUnitedStates(U.S.)hasthehighestrateofwomen’s incarcerationintheworld(Fair&Walmsley, 2022). Between1978and2007,women’sincarcerationrates increasedby560%(Heimeretal., 2023).Asof2022,there were87,784womenincarceratedinstateorfederalprisons, a4.9%increasefromtheyearbefore(Heimeretal., 2023; Carson&Kluckow, 2023).TheU.S.istrulyuniquein women’sincarceration;theU.S.populationmakesuponly 5%oftheworld,butaccountsfornearly30%ofincarceratedwomen.TheU.S.women’sincarcerationrateis over10timesthatofthesecondmostincarceratingNATO countries,Portugal(Kajstura, 2018).TheU.S.isalsounique inthedecentralizednatureofitscriminallegalsystem. Women’sincarcerationratesbystaterangefromOklahoma at281per100,000toRhodeIslandatjust29per100,000, comparabletoAustralia(Kajstura, 2018).Thesefactors makecomparisontoothercountriesdif ficultandoutsidethe scopeofthismanuscript.Thus,wemustfocustheintroductionontheU.S.carcerallandscape.

MassincarcerationofwomenintheU.S.hascontributed tothephenomenonoffrequentexperiencesofpregnancy andbirthduringincarceration.Anestimated2–4%of womenwhowereincarceratedinprisonswerepregnantat admissionandroughly1000womengivebirthduringtheir incarcerationeveryyear(Sufrinetal. 2020;Sufrinetal., 2019).Incarceratedpostpartumwomenandtheirchildren areahighlymarginalizedgroupathighriskofadverse healthanddevelopmentaloutcomes.TheU.S.criminal legalsystemsystematicallytargetsgroupsminoritizedby raceandincome(Alexander, 2012;Pettit&Western, 2004; Roberts, 1997).Incarceratedwomenalsofrequentlyreport chronicphysicalandmentalhealthconditionsandexposure toviolenceandotherformsofvictimizationpriortotheir incarceration(Knight&Plugge, 2005).Prisonconditions duringpregnancysuchaslackofaccesstoqualitymedical careandharmfulpracticessuchasshacklingandsolitary confinementmaycompoundpre-incarcerationstructural riskfactorstofurtherjeopardizeoptimalinfanthealth. Indeed,thelimitedliteratureonhealthoutcomesforinfants exposedprenatallytomaternalincarcerationsuggestthat incarcerationmaybeariskfactorforlowbirthweightand pretermbirth(Howardetal. 2010;Testa&Jackson, 2020)

Forinfantsbornduringtheirmother’sincarceration, earlymaternalseparationmaythreatentheirdevelopment, andespeciallythedevelopmentofattachmentrelationships. Infancyrepresentsaunique,sensitiveperiodinchild developmentduringwhichmultiplesystemsarerapidly maturing(Nelson&Bosquet, 2000).Thisperiodis importantforthedevelopmentofanattachmentrelationship.Infantsareevolutionarilydriventoremaininclose contactwiththeirprimarycaregiver,typicallytheirmother, andthroughdailyinteractionsformarelationshipinwhich theyseekcomfortfromtheircaregiverandusethemasa

securebasefromwhichtoexploretheirenvironment (Bowlby, 1982).Researchonmaternal-infantbonding, oftenconsideredaprecursortoattachmentanddeveloping inthe firstseveralmonthsoftheinfant’slife,hasidenti fied touch,closecontactthroughrockingandfeeding,andfrequentface-to-faceinteractionasessentialtoformthebond thateventuallycanleadtosecureattachment(Gholampour etal. 2020,Muziketal. 2013).Whilethefoundationofthe attachmentrelationshipisbuiltduringinfancy,asthechild develops,thisrelationshipisconsideredessentialforthe child’semotionalwellbeing(Bowlby, 1982).When attachmentrelationshipsaresecure,infantscanexploretheir environmentswithoutunduefearordistress(Waters& Cummings, 2000).Incontrast,whencaregiversareunable orunwillingtorespondappropriatelytoinfantdistress,or wheninfantsareseparatedfromtheircaregivers,especially repeatedly,infantsmaydevelopinsecureordisorganized attachmentrelationships,whichhaveknownnegativeconsequencesforbehavioraloutcomes(Benoit, 2004).

Earlylifeseparationbetweenamotherandherchildis oneimportantaspectofmaternalincarcerationhypothesized tobeparticularlydamagingtochildren’sbehavioralhealth throughthepathwayofdisruptedattachmentrelationships (Arditti&McGregor, 2019;Poehlmannetal., 2010). Researchhasshownthatolderchildrenwithincarcerated mothersareathighriskofinsecureattachmentrelationships withboththeirmothersandtheircaregiversduringtheir mother’sincarceration(Poehlmann, 2005a).Inaddition, childrenwhoparticipatedinaprisonnurseryprogram, specializedcarceralprogramsthatallowinfantstoco-reside withtheirmotherinthefacility,weremorelikelytohavea secureattachmentrelationshipwiththeirmotherscompared tochildrenwhosemothersenteredincarcerationduringtheir child’sinfancyortoddlerhood(Byrneetal. 2010).This suggeststhatseparationinandofitselfputsinfantsatriskof insecureattachment.Researchintoexperiencesofinfants borntochildrenwithincarceratedmothersnotonly experienceseparationfromtheirmothersbutmayalso experiencesubsequentlossofprimarycaregivingrelationshipsatahighrate.Pendletonetal.foundthatofchildren borntowomenincarceratedinprison,45%werenolonger livingwiththecaregiverwhotookthemhomefromthe hospital(2021).Similarly,Kotlaretal.foundthat19%of infantsexposedprenatallytomaternalincarceration experiencedseparationfromanon-maternalcaregiverin their firstyearoflife(2025a).

ContactBetweenIncarceratedMothersand TheirChildren

Unfortunately,prisonnurseryprogramsandcommunitybasedalternativestoincarcerationforpregnantand

postpartumwomenarerare(Jensen, 2021).Mostinfants bornduringtheirmothers’ incarcerationwillexperience separationfromtheirmotherwithindays.Theseinfants mustbecaredforbysomeoneotherthantheirmother, typicallyagrandparent(Kotlaretal. 2025b;Pendletonetal. 2021;RodriguezCarey, 2019).Mothersmustrelyontheir infants’ caregiverstonavigateprisonpoliciesandcompetingprioritieslikeworkandcareforotherchildrento facilitatecontactbetweenthemotherandherinfant (Poehlmannetal. 2010;Tasca, 2016).Thequalityofthe relationshipbetweenthemotherandherchild’scaregiver hasbeenshowntoinfluencetheamountofcontactincarceratedmothershavewiththeirchildren(Loper&Clarke, 2013;Poehlmannetal. 2008).Whileformanyincarcerated mothersthisrelationshipwillbeprimarilybasedon experienceswithherchild’scaregiverpriortoherincarceration,maintainingaconstructivecoparentingalliance withthechild’scaregiverwillalsodependonherabilityto beincontactwiththecaregiverduringherincarceration (Loper&Clarke, 2013).

Amother’sinabilitytomaintaincontactwithherinfant hasrepercussionsforherwellbeingaswellastheinfant’s. Researchwithincarceratedmothersofolderchildrenhas shownthatmothers’ abilitytomaintaincontactwithchildrenisassociatedwithmorepsychologicalwell-being (Houck&Loper, 2002;Loperetal., 2009;Poehlmann, 2005b;Tuerk&Loper, 2006).Frequentcommunication betweenanincarceratedmotherandherchildrenhasbeen showntoreduceparentingstress(Houck&Loper, 2002) andincentivizethemothertoworktowardreleaseand reuni ficationgoals(Arditti&Few, 2006).Thisisimportant asmanymotherswillbereleasedwithinthreeyearsoftheir child’sbirth(Butcheretal., 2017;U.S.SentencingCommission, 2018),andmostincarceratedmothersreport resumingcustodyofatleastsomeoftheirchildrenonor aftertheirrelease(Fessler, 1991;Thompson, 2021).Thus, contactbetweenanincarceratedmotherandherinfanthas thepotentialtoinfluencewhethermotherscansuccessfully parenttheirchildinthefuture.Indeed,studieshaveshown thatasignificantpredictorofreunifi cationbetweenformerly incarceratedparentsandtheirchildrenistheabilityto maintaincontact(Charlesetal., 2023;Snyderetal. 2001).

ContactBetweenPostpartumIncarcerated MothersandTheirInfants

Infantsbornduringtheirmothers’ incarcerationareconstrainedintheirabilitytodevelopapositiverelationship withtheirmother.First,infantsseparatedatbirth,incontrastwitholderchildrenofincarceratedmothers,willnot haveestablishedapostnatalrelationshipwiththeirmother fromwhichtobasefutureinteractions.Ofequalimportance,

infantsaredevelopmentallyconstrainedastothetypeof contacttheycanengagein.

Lessthanhalfofmothersincarceratedinprisonreport receivingavisitfromtheirchildren(Mumola, 2000). However,thisresearchhasexclusivelyfocusedonolder, typicallyschool-agedoradolescent,children.Reported barrierstoin-personvisitsincludethedistancetothefacility aswellasthecaregivers’ andmothers’ reluctancetoexpose childrentoacarceralenvironment(Tuerk&Loper, 2006). Forthosewhodovisittheirincarceratedmothers,research findingsaremixedastowhethervisitsarebeneficialto children(Poehlmannetal. 2010).In-personvisitswith meaningfulandqualityinteractionsareassociatedwith improvedchildattachmentandadjustment,betterfamily relationships,decreasedparentingdistressforincarcerated parents,andimprovedparentingskillsinparentsofchildren betweentheagesof2and18(Dallaireetal., 2012; Poehlmann, 2005b;Beckmeyer&Arditti, 2014).Despite thesemixedresults,in-personvisitsofferthemostdevelopmentallyappropriateformofcontactbetweeninfantsand theirincarceratedmothers,asinfantsrequiretouch,sustainedeyecontact,andclose,reciprocalinteractionstoform bonds(Gholampouretal. 2020,Muziketal. 2013).

Videochat,conductedremotelyorwithinthecarceral facility,isanotheremergingformofcontact,whichhas beencriticizedforitsinherentlimitationsintermsoflackof physicalcontactbetweentheincarceratedmotherandher children(Ardittietal. 2003;Poehlmann-Tynanetal., 2015). However,littleresearchexistsontheimpactofvideochat onmaternalandchildrelationships.Onesmallstudyfound thatwhilechildrenaged2to6yearsoldengagedwiththeir incarceratedparentduringvisits,theywerefrequentlydistractedwhenparticipatinginvideovisitsatthecarceral facility(Poehlmannetal. 2015).Infantsaredevelopmentallyevenlesslikelytosustainattentionlongenough tohavemeaningfulcontactwithincarceratedmothersduringvideovisits.

Phonecallsandlettersarethemostfrequentlyused methodsofcontactbetweenolderchildrenandtheir incarceratedmothers(Shlaferetal. 2015;Stringer& Barnes, 2012 ).However,tostatetheobvious,infants cannottalkonthephoneorreadorwritealetter,andeven videochathaslimitationsforinfants(SkoraHorgan& Poehlmann-Tynan, 2020 ).Thus,frequentinpersonvisiting wouldbetheonlydevelopmentallyappropriatewayfor infantstodeveloparelationshipwiththeirmothers.Despite boththeimportanceofcontactbetweenmothersandtheir infantsandthedevelopmentalconstraintsuniquetoinfants, noresearchtoourknowledgehasattemptedtocharacterize thetypeandqualityofcontactbetweenincarcerated mothersandtheirinfantsinthecontextofmaternal separationatbirth.Understandingcontactbetweenincarceratedmothersandtheirinfantsinearlylifeisimperative

toinformprisonandjailpoliciessurroundingvisitingand otherformsofcontact.

TheCurrentStudy

Thegoalofthecurrentstudywasto fillthiscriticalgapin theliteraturebydescribingcontactbetweeninfantsborn duringtheirmothers’ incarcerationinprison,theircaregivers,andtheirincarceratedmothers.Theprimaryresearch questionsaddressedbythisstudyare:1.Whichtypesof communicationareutilized?2.Whatwerebarriersto contactingeneralandtoinpersonorvideovisitsspeci fically?and3.Whatstrategiesdocaregiversemployto facilitatecontactbetweentheincarceratedmotherandher infant?Toanswerthesequestionsthisstudytookthefollowingapproach.First,wefocusedonassessmentsconductedbetweenbirthandwhenthechildwasfourmonths old,hypothesizingthatearlyinfancyrepresentsbotha particularlychallengingandimportantperiodformother/ infantcontact.Speci fically,wefocusedoninfantsbetween birthandfourmonths,astheseearlymonthsareconsidered tobecriticalinforminghealthymaternal-infantbonds throughbehaviorssuchastouch,smell,andinteractionwith infants(Gholampouretal. 2020).Becauseoftheimportanceoftactileconnectionformaternal/infantbonding,we definedhigh-qualitycontactasin-personvisits.Second,we utilizedamixedmethodsstudydesign,analyzingboth quantitativeandqualitativedatatotriangulateascompletea pictureonmother/infantcontactaspossible.Finally,we focusedoncaregiverreportsofcontactininfancy,recognizingthatcaregiversrepresentimportantgatekeepersto mother/infantcontact.

Methods

DataCollection

ThisstudyuseddatafromtheBirthBeyondBarsStudy (BBBStudy),anongoingmixedmethodsbirthcohortof childrenexposedprenatallytotheirmother’sincarceration inprisonorjailinthreestates(Georgia,Maine,and Pennsylvania).Mothersornon-maternalcaregiversofa childthatexperiencedmaternalincarcerationatsomepoint duringtheirgestationareeligibleforenrollmentintheBBB Study.ThecurrentstudydrawsdatafromtheGeorgiasite asithasthemostrobustsamplesize.InGeorgia,theBBB StudyisconductedincollaborationwithMotherhood BeyondBars(MBB),anonpro fitthatsupportspregnantand postpartumincarceratedandformerlyincarceratedwomen andtheirfamilies.MBBstaffapproachedalleligible infants’ primarycaregivers,eithermothers,fathers,or

designatedcaregivers,forenrollmentinthestudyduring pregnancyoratthebirthofthechild.Non-maternalcaregiverswereapproachedatthebirthinghospitalwhenthey assumedcustodyoftheinfant.Intakeinterviewsoccurredat enrollmentoftheinfant,typicallywhenheorshewasless than2monthsoldandfollow-upinterviewsoccurredwhen theinfantwasbetween3and4monthsold(interviews occureverythreemonthsintheBBBStudytocloselytrack childdevelopment).Interviewsincludedasemi-structured portionandaguidedsurveywithclose-endedquestions. QuestionsweredevelopedbasedonareviewoftheliteratureandtheexpertknowledgeofresearchersandMBB staff.Allinterviewsoccurredoverthephone.Caregivers werecompensatedfortheirtime.TheBBBStudyiscovered undertheHarvardLongwoodMedicalAreaIRB(20-1215, 21-1247).

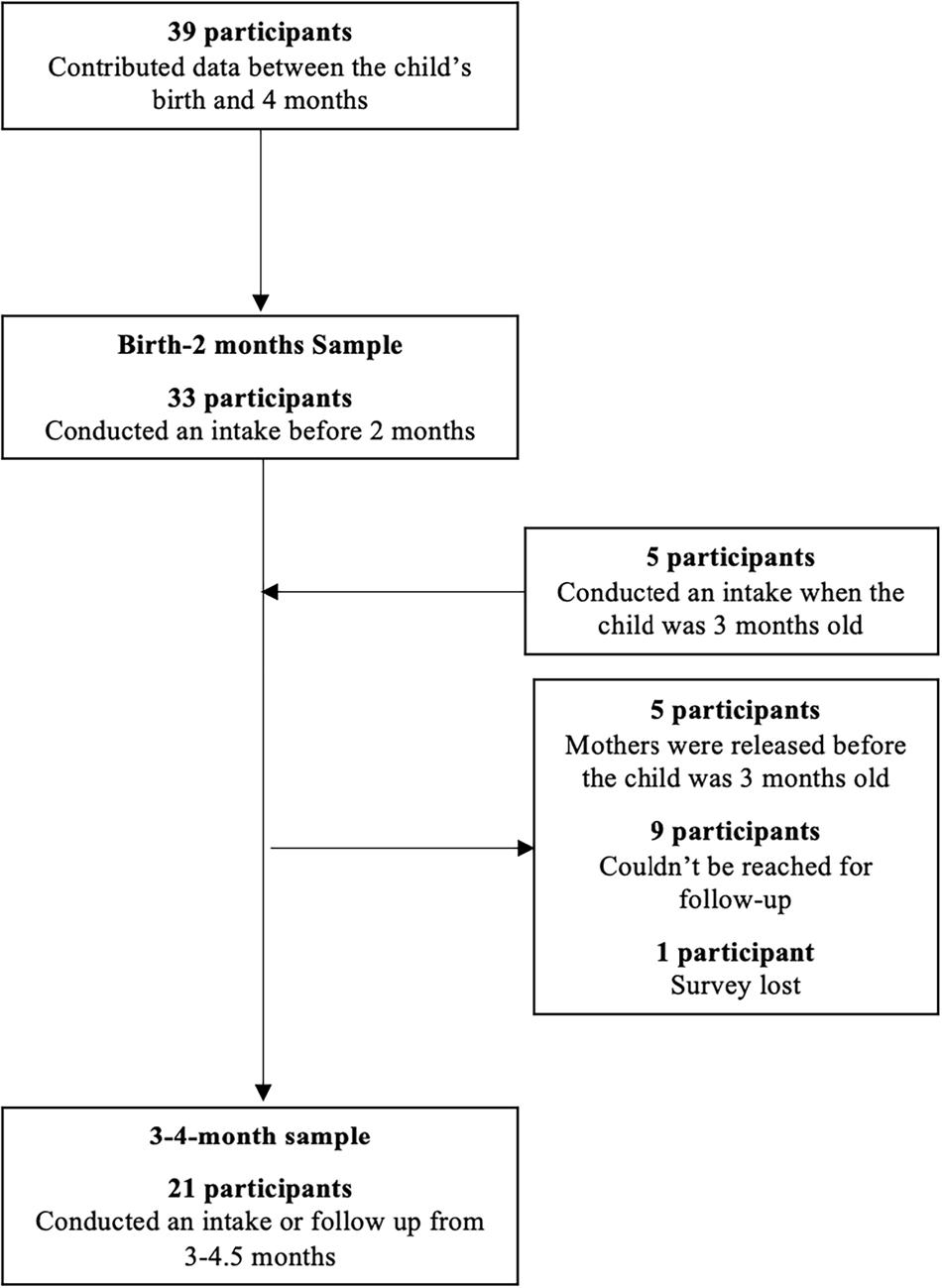

Forthecurrentstudy,wedrewdatafromintakeandfollowupinterviewsconductedwithnon-maternalcaregiversthat occurredbetweenAugust2020andJune2023.Intotal,39 caregiverscontributeddatatothisstudy.Weextracted communications-relatedclosed-endedsurveyresponsesand responsestocommunications-relatedopen-endedquestions. Datafromopen-endedquestionswereincludeduntilsaturation wasreached,at39interviews.Wedefinedsaturationas interviewsyieldingnonewthemesorrelevantcontentfor existingthemes(Hennink&Kaiser, 2022).Wegroupeddata intotwotimeperiodsbasedontheageoftheinfantatthetime oftheassessment,frombirthuntiltheinfantwastwomonths andwhentheinfantwasthreetofourmonthsold.Intotal, quantitativeandqualitativedatafrom33caregiverswho completedinterviewsbeforethechildwastwomonthsoldand 21caregiverswhocompletedinterviewswhenthechildwas threemonthstofourmonthsold wereincludedinthisstudy’s sample.Ofthe33caregiverswhocompletedinterviewsbefore thechildwastwomonthsold,15(45%)returnedforthe interviewatthreetofourmonths,while6(15%)childrenhad caregiverswhoparticipatedinonlyoneinterviewwhenthe infantwasbetweentheagesof3and4monthsold.Withinthe birthtotwomonthssample,19(58%)ofchildrenwereless than1monthold,8(24%)were1monthold,and6(18%) were2monthsold.Inthethree-to-four-monthsample,16 (76%)were3monthsoldand5(24%)were4monthsold.See Table 1.Fiveintakeinterviewsoccurredwhenthechildwas threemonthsold.Three-monthinterviewsfrom fivecaregivers whocontributeddataatintakewerenotincludedasthemother wasreleasedbeforethefollow-upinterviewoccurred.Ten caregiverswhocontributeddataatintakecouldnotbereached forafollow-upinterview.Onesurvey filewaslost.SeeFig. 1

Afewearlysemi-structuredintakeinterviews(n = 5) conductedbyonestaffmemberwere flaggedaslowindata quality.Thisstaffmemberdidnotconductfurtherinterviews,andallcaregiversinterviewedduringthistime (n = 12)wereapproachedtobere-interviewed.To

Table1 Semi-structuredinterviewquestions

Intakeinterviews(N = 33)

Howdidtheamountofcontactyouhadwith[mother’sname] changewhenshewasincarcerated?Why?

Howdidthelevelofcontactwith[infantname]’smotherchange afteryoubroughthimorherhome?Why?

3-monthinterviews(N = 21) Probingquestionsinitalics

Howfrequentlyhaveyoubeenincontactwith[infantname]’s mothersincewelasttalked?

Couldyoutellmeaboutmakingsharedparentingdecisionswith [infantname]’smother?

Whatisespeciallyhardaboutmakingsharedparentingdecisions?

HowhasCOVID-19impactedyourabilitytoshareparenting decisionswith[infantname]‘smother?Whathasbeenpositive aboutmakingshareddecisions?

Howdoes[infantname]reactto[infantname]‘smotherwhile communicatingoverthephoneorvideo?

Does[infantname]displaysignsofaffectionformotheroverthe phoneorvideo?Howis[infantname]interactingwith[infant name]‘smotherascomparedtothelasttimewespoke?

Additionalquestionsaskedincaregiverextendedinterviews (n = 12)

Thinkingaboutthe firstthreemonthsof[infantname]’slife,howdid youinvolvehisorhermotherintheirlife?

Whatdid[infantname]’smotheraskyouthatyoudidn’twantto sharewithherabout[infantname]?

Inthe firstthreemonthsof[infantname]’slife,didyouhaveavideo callwithhis/hermotherwithhim/herthere?Ifyes,whatwasitlike?

Whatwasespeciallychallengingaboutcommunicatingwith[infant name]’smotherduringthe firstthreemonthsofhis/herlife?

capitalizeontheadditionaldatacollectionopportunity, additionalquestionswereaskedduringtheseinterviews. Theseextendedin-depthinterviewswerealsoincludedin thequalitativesample.

QuantitativeMeasures

CaregiverSatisfactionwithAmountofCommunication. Duringtheintakeandfollow-upinterviews,caregiverswereaskedtoranktheirlevelofsatisfactionwith theamountofcommunicationtheymaintainedwiththe motherduringherincarceration.Interviewersasked caregivers, “ howsatis fi edareyouwiththeamountof contactthatyou ’ vehadwith[infantname] ’ smother? ” Responsechoicesincluded:extremelysatis fi ed,somewhatsatis fi ed,neithersatis fi ednordissatis fi ed,somewhat dissatis fi ed,orextremelydissatis fi ed?Responseswere categorizedonaLikertscalefrom0to4,with0being extremelydissatis fi edand4beingextremelysatis fi ed.

ModeofCommunication. Duringtheintakeandfollow-up interviews,caregiverswereaskedtosharewhatmodesof communicationtheyutilizedwiththemother.Thefollowingoptionswereprovided:sendingletters,calling,

emailing,sharingphotographs,sharingvideomessages,and other. “Other” promptedanopen-endedtextresponse, whichcaregiverswereaskedtodescribe.Selectingmore thanonetypeofcommunicationmethodwaspermitted.

BarrierstoCommunication. Duringboththeintakeand follow-upinterviews,caregiverswereaskedtosharewhat barrierstocommunicationtheyhavefacedwhentryingto contactthemotherduringherincarceration.Thefollowing optionswereprovided:nomoney,nokioskaccess,tablets notworking,schedulingdif ficulties,makesmomtoosad, makescaregivertoosad,momthinksrelationshipisbad, caregiverthinksrelationshipisbad,noprivacy,COVID-19 policies,andother. “Other” promptedanopen-endedtext response,whichcaregiverswereaskedtodescribe.Selectingmorethanonebarrierwaspermitted.Tabletsreferto smarttabletsoccasionallymadeavailabletoincarcerated peopleinGeorgia.Kiosksrefertothedevicethroughwhich videovisitsareinitiated.Thesewereaddedtotheanswer choicesbasedonadvicefromstaffatMBB

QualitativeMeasures

Duringthesemi-structuredportionoftheintakeinterview, non-maternalcaregiverswereaskedtodescribehowtheir

relationshiptothechild’smotherchangedduringher incarcerationandaftertheypickedthechildupfromthe hospital.Probesforthesequestionsfocusedontheamount andtypeofcontactwiththeincarceratedmother.During follow-upinterviews,caregiverswereaskedaboutthe amountofcontactwiththeincarceratedmother,whether andhowtheyweresharingparentingdecisionswiththe mother,andhowtheinfantreactedtothemotherwhenin contactwithher,ifatall.Caregiverswhoparticipatedinthe extendedin-depthinterview(n = 12)werealsoaskedhow theymaintainedcontactbetweentheinfantandtheir mother,whattheysharedabouttheinfantwiththemother, andanybarrierstocommunicationwhiletheinfantwas threemonthsandyoungerandtodescribeanyexperiences within-personvisitsorvideochatswiththeincarcerated motheriftheseoccurred.SeeTable 2 forsemi-structured interviewquestionsateachassessment.

DataAnalysis

Toanswerourresearchquestions,weanalyzedboth quantitativeandqualitativedata.Quantitativedatawasused todeterminethefrequencyatwhichavailablemodesof communicationwereutilizedduringeachbroadtimeperiod,howfrequentlytypicalbarrierstocommunicationwere experiencedateachtimepoint,andthelevelofsatisfaction reportedbycaregiversregardingtheamountofcontactwith theincarceratedmother.Communication-relatedquantitativemeasuresandcaregiverdemographics(age,sex,race/ ethnicity,relationshiptothemother,povertylevel)were extractedfromthesurveysoftwaretodescribefrequencies andmeansforeachtimeperiod.Datafrombothsamples wereimportedintothestatisticalsoftwareRStudio (2023.06.0 + 421).

Qualitativedatawasusedtocontextualizedescriptive quantitativeresultsandtodeeplydescribecaregivers ’ experiencesfacilitatingcontactbetweenincarcerated mothersandtheirinfants.Todoso,researchersanalyzed semi-structuredinterviewtranscriptsfromcommunicationrelatedqualitativeportionsofinterviewsconductedshortly afterthebirthofthechildandwhenthechildwasthreeto fourmonthsold.Toyielddescriptionsofcaregivers ’ experiences,qualitativetranscriptswereanalyzedusinga thematicanalysisapproachasdescribedbyBraun&Clarke (2006).Theanalysisteamconsistedofadoctoralstudent (BK),amaster’slevelresearcher(KP),twograduatestudentsandanundergraduatestudenttrainedinqualitative methodsandthecontextofmaternalincarcerationfrom birth.TheteamwasledandsupervisedbyBK.Researchers developedacodebookofinductiveanddeductivecodes throughintensivereadingofsixtranscriptsandweeklyteam discussion.Twoindependentcoderscodedeachcaregiver

Table2 Distributionofselectedcharacteristicsofcaregiversof childrenborntoincarceratedmothersatintake(birthto2months) andfollow-up(3to4months)

Intake(birthto2 months)sample Follow-up(3to4 months)sample

n = 33 n = 21

CategoricalVariable n (%) n (%)

25–355(15.2)2(9.5)

36–4511(33.3)8(38.1)

46–558(24.2)7(33.3)

56–657(21.2)2(9.5)

65+ 2(6.1)1(4.8)

Missing01(4.8)

Ethnicity

Non-Hispanicor Latino/a 31(93.9)20(95.2)

HispanicorLatino/a2(6.1)1(4.8)

Race

White21(63.6)9(42.9)

Black12(36.4)12(57.1)

Belowthefederalpovertyline

No24(72.7)13(61.9)

Yes9(27.3)7(33.3) Missing01(4.8)

Caregiver’srelationshiptothemother Noformal relationship 4(12.1)1(4.8)

Friend5(15.2)4(19)

Otherrelative9(27.3)9(42.9)

Parent11(33.3)6(28.6)

Partner4(12.1)1(4.8)

InfantAge

Lessthanonemonth19(57.6)0 Onemonth7(21.2)0 Twomonths6(18.2)0 Threemonths016(76.2) Fourmonths05(23.8)

Modesofcommunication

Letters14(42.2)6(28.6)

Calling29(87.9)18(85.7)

Emailing15(45.5)9(42.9)

Photos23(69.7)15(71.4)

Conductedvideo visitswithmomand infant 02(9.5)

Videograms9(27.3)6(28.6) Other4(12.1)5(23.8)

Sharedphotographsofmomwithinfant No24(72.7)7(33.3) Yes9(27.3)8(38.1)

Table2 (continued)

Intake(birthto2 months)sample

Follow-up(3to4 months)sample n = 33 n = 21

CategoricalVariable n (%) n (%)

Missing06(28.6)

Communicationbarriers

Nomoney4(12.1)2(9.5)

Nokioskaccess5(15.2)2(9.5)

Tabletdon’twork01(4.8)

Hardtoschedule5(15.2)2(9.5)

Makesmomtoosad3(9.1)0

Makescaregivertoo sad 1(3)0

Momthinks relationshipbad 00

Caregiverthinks relationshipbad 01(4.8)

Noprivacy2(6)0

Other9(27.3)4(19)

Satisfactionwithamountofcommunication

Extremely dissatisfied 3(9.1)1(4.8)

Somewhat dissatisfied 3(9.1)0

Neithersatisfiedor dissatisfied 00

Somewhatsatis fied15(45.5)9(42.9)

Extremelysatis fied12(36.4)11(52.4)

transcriptusingthecodebook.Codingwasthenreviewed bythewholeteamandanydiscrepancieswereresolved throughteamdiscussion.Todeveloppreliminarythemes, excerptsbelongingtoeachcodewerereadanddiscussedby theanalysisteam.Codeswerethengroupedaccordingto theresearchquestionanddescribed.Fullcodinggroup descriptionswerethendiscussedtodeveloppreliminary themes.Themeswerevalidatedthroughexpertreviewand memberchecking.Resultsweresharedwithstafffrom MBB,whoservedasexpertreviewers.Resultswerealso sharedduringavideomeetingwith fi vecaregivers,who providedfeedback.Researchersintegratedfeedbackinto preliminarythemestodevelop fi nalthemes.Caregiver pseudonymswereusedwhenrelevantquoteswereincluded inthemedescriptions.

Tocontextualizeandprovidenuancefordescriptive quantitativeresults,researchersconductedasubsequent inductivereadingoftranscripts.Duringthisreading, researcherslinkedanswerstoquantitativequestionson modesofcontactutilized,barrierstocontact,andsatisfactionwiththeamountofcontacttomoreextendedcaregiver

narrativesprovidedduringopen-endedquestionsorsurroundingclose-endedquestions.Thesequoteswerethen reviewedbyresearcherstoyieldadditionalinsightsinto quantitativeresults.

CaregiverDemographics

Becausecaregiversampleswereslightlydifferentineach timeperiod,wecalculatedcaregiverdemographicsseparately.Inthebirthtotwomonthssample,mostcaregivers werenon-Hispanic(31,94%)andwhite(21,64%).The relationshipbetweencaregiversandmothersspannedblood relatives,includingparents,siblings,aunts/uncles,etc.,to friends,partners,andthosewithnorelationshipwiththe mother.Caregiversweremostlikelytobeparentsofthe mother(11,33%),whiletheleastrepresentedrelationship typewasthemother’spartner(4,12%).Theaverageageof caregiversinthesamplewas47.6[SD11.3]yearsold,with themajoritybetweentheagesof36-45(11,33%).Atotal of9(27%)caregiversreportedlivingundertheFederal PovertyLine(FPL)whichisameasuresetbytheU.S. HealthandHumanServicesbasedonaverageincomeand householdsizetodetermineeligibilityforcertaingovernmentbenefitsprograms

Caregiversinthethree-to-four-monthtimeperiodwere morelikelytoidentifyasBlack(12,57%),andwereprimarilynon-Hispanic(20,95%).Caregiverrelationshipsto theinfantweresimilaracrosstimeperiods,with(6,28.6%) identifyingasparentsofthemother.However,fewerpartnersofthemothercontributeddatatothethree-to-fourmonthtimeperiod(1,4.5%).Slightlymorecaregivers reportedlivingundertheFPL(7,33%).

Results

CommunicationStrategies

BetweenMothersandCaregivers

Themostcommonmodeofcommunicationbetweencaregiversandmothersafterbirthwasphonecallingatboth timeperiods(29,88%betweenbirthandtwomonths,18, 86%betweenthreeandfourmonths).Mothersmostfrequentlyinitiatedcallsduetocarceralpoliciesregarding phonehours.Eightcaregiversinthebirthtotwomonth sampleandthreecaregiversinthethreetofourmonth sampleprovidedextendednarrativecontextualizingthe popularityofphoneconversations.Theseparticipantsclarifiedthatwhiletheywouldhaveappreciatedotherformsof communication,contactthroughphonewastheeasiestto accessandthemostconvenient.AsPatriciasaidwhen askedwhyphonecallswereherpreferredmethodof

Fig.2 Communicationtypeat intake(birthto2months)and follow-up(3–4months)

contact, “it’sjusttheeasiest[method]…shewouldcallmy cellphoneormyson.” Whilecallingwasperceivedaseasy andlow-barrier,caregiverswhoelaboratedonthischoice frequentlyexpressedfrustrationwithhavingtowaitforthe mothertoinitiatecontact,whichmadeintegratingcallsinto theirlivesdifficultandprecludedcontactregardingmore urgentissues.Theinabilitytoschedulecallsledtomany missedconnections.Valeriedescribed: “SosometimesI catchhercalls.SometimesIdon’t.SometimesI’msleeping orI’moutandIdon’thearitinmypocketbook.” Inaddition,caregiverswerefrustratedbythelackofabilityto reachthemotherifneeded.AsSarahshared, “I’dsayIwish wecouldbeabletocallherifweneededto.Ihatethatpart. Thatwedon’tgettotrytogetaholdofher,ifweneedto.” Sendingphotographswasthesecondmostcommon communicationmethodusedbycaregiversatbothtime periods(23,70%betweenbirthandtwomonths;15,71% betweenthreeandfourmonths).Atotalof9(27%)caregiversreportedsendingvideomessagestothemotherduringtheirincarcerationbetweenbirthandtwomonths,while 6(29%)reportedthisbetweenthreeandfourmonths.See Fig. 2.Othercommunicationstrategiesusedbycaregivers includedemailing(15,45.5%betweenbirthandtwo months;9,43%betweenthreeandfourmonths)and sendingletters(14,42%betweenbirthandtwomonths;6, 28.6%betweenthreeandfourmonths).However,participantsdescribedthesemethodsasmorelaborintensivethan

phonecalls,oftenrequiringoutsidehelpfromfamily membersorfromMotherhoodBeyondBars(particularlyfor sendingphotographs).

BetweenMothersandTheirInfants

Nocaregiversreportedfacilitatingvideochatsbetweenan incarceratedmotherandherinfantbetweenbirthandtwo months,whileonly2caregiversreportedthisbetween3and 4months(9.5%).Denise,oneofthesetwocaregivers, sharedthatshetriedtoholdvideovisitsatleastoncea monthbecauseoftheimportanceofinteractivecontactfor her,herfamily,andtheincarceratedmother.Nocaregivers ineithertimeperiodreportedtakingtheinfanttovisittheir motherin-personwhileincarcerated.

BarrierstoContact

Caregiverswereaskedtoreportbarrierstocommunication ingeneralonthequantitativesurvey.Themostfrequently reportedbarrierstocontactbycaregiversbetweenbirthand twomonthsonthequantitativesurveyincluded financial issues(4,12%),schedulingdif ficulties(5,15%),andcontactmakingthemothertoosad(3,9%).Manycaregivers providedotherbarrierstocommunication(9,27%), includingnotbeingontheapprovedcalllist,alackof internet/cellservice,andthemothernotwantingtotalkon

thephone.Inthethree-to-four-monthperiod,otherbarriers (4,19%)tocommunicationwerethemostfrequently reported,includingthecaregiverbeingtiredafterwork,the highcostofcalling,andthelimitedtimeallowedonthe phone.Schedulingdif ficulties(2,9.5%), financialbarriers (2,9.5%),thecaregiverthinkingtheirrelationshipwiththe motherispoor(1,4.8%),andalackofkioskaccess(2, 9.5%)werealsoreportedasbarrierstocontactbycaregivers inthe3–4-monthtimeperiod.

Qualitativedatacontextualizedthesebarriersandilluminatedwhichweremostimportantforeachmodeof contact.

SendingPhotosorVideoMessages

Caregiverscitedtechnologicalliteracyastheprimarybarriertothisformofcommunication.Manycaregivers reportedsendinginpicturesthroughMBBduetodifficultiestheyexperiencedontheirend.Othersdescribeddif ficultyunderstandinghowtosendvideomessages.For example,Bethstatedwhenexplainingwhyshehasn’tsent videomessagesorphotosoftheinfanttotheincarcerated mother: “I’mverycomputerilliterate,myphone,Italkand text.Andthat’sit.” Inaddition,onecaregiver,Katherine, describedtheprison’srestrictionsonthetypesofphotos caregiverswereallowedtosendasabarrier:

“Ican’tsendherpicturesofher firstbath,orthevideo. Icouldn’tdodiaperpictures.I’mnotallowed.Andwe understandthereasonsforallofthis,right?Butit takesthings[away]andthat’sheartbreaking.”

Phonecalls

Inadditiontoissueswithschedulingcallsdescribedabove, themostsalientbarrierdescribedbycaregiverswasthecost ofcalls.Infact,mostcaregiversreportedthatmotherscalled frequently,typicallymoreoftenthanthecaregivercould handle financiallyorlogistically.Dianeshared: “She[the mother]wascallingeverysingleday.Attimes,wewere like, ‘[infant’smother],ohmygosh!’ Because ohmy lord!That’sexpensive!” Althoughalmostallcaregivers reportedthatphonecallsfromthemotherwerea financial burden,manyworkedtomakesurethattherewasenough moneyinthesystemtoallowthemothertocallatleast severaltimesaweek.David,whileacknowledgingthe financialstrainonhisfamily,said: “Wetrytokeepasmuch moneyaspossiblesoshecancallwhenshewants.” Two caregiversreportedhavingtoasktheincarceratedmotherto calllessfrequentlybecauseofthesigni ficantcosttothem.

Dawnsharedthatshetoldtheincarceratedmother: “you gottastopcallin’ somuch.Ican’taffordit.”

VideoVisits

Intheabsenceofaccesstoin-personvisits,severalcaregiversattemptedtoestablishvideovisits.However,the technologyrequiredtoinitiateavideovisitwasasignificant barrier.Caregiversstatedthateithertheydidnothavea desktopcomputer(requiredtousethesoftware)orthatthey werenottechnologicallyliterateenoughtousetheoption. Wandasaidthatshecouldnotdovideochatbecause “it doesn’tworkonaphone.Itdoesn’tworkonaphoneoran iPad.Youactuallyhavetohavealaptoporadesktop.It doesn’tworkonaChromebook.Wefoundoutthehard way.” Whilenotreportedbyotherparticipants,onecaregiver,Kelly,statedthatwhilesheknowsthatMBBstaff encouragevideochats,shefeelsthatshewouldn’tbeableto fitthemintoherbusylifestyle.

InPersonVisits

Inthissample,45caregiverinterviews(83%)wereconductedwhileCOVID-19pandemicvisitingrestrictionswere stillineffect,beforetheywereliftedinJuly2022.COVID19pandemicrelatedpolicieswerefrequentlycitedasa barriertoin-personvisitswiththemother;40%reported visitingbeingsuspendedduringthemother’spregnancydue totheCOVID-19pandemicwhenthechildwasundertwo monthsold.Likewise,nocaregiversinthethree-to-fourmonthtimeperiodwereabletotaketheinfanttovisitthe mother,with4(18%)reportingtheCOVID-19pandemicas thereasonforthelackofvisits.

Duringthepandemic,theGeorgiaDepartmentofCorrections(GDOC)implementedvisitingpoliciesinlinewith theabilitytogetvaccinated.Thus,childrenundertheageat whichvaccinationswereavailablewerenotallowedtovisit. ThesepoliciesendedinJuly2022.Otherswhowere interviewedlaterdiscussedtheirdistancefromthefacilityor afacility-speci fi cpolicyallowingonlyadultstovisitas primarybarriers.

Gettingontheapprovedvisitorlistwasalsodiscussedas abarriertoin-personvisiting.TheGDOCcurrentlyrequires bothcaregiversandinfantstobeonanapprovedlistto participateinin-personvisits.Caregiversreportedasignificantlagtimebetweenwhentheyassumedcareforthe babyandwhentheyortheinfantwereplacedonthe mother’sapprovedlist.Caregiversarerequiredtovisita notarytocompletethispaperwork,whichMBBstaffreport asamajorbarrierwhenalsocaringforanewborn.Furthermore,delaysonthecarceralfacilityendwerefrequently

reported.Severalcaregiversdiscussedthisdelaybeing incrediblyfrustrating.Kellystated:

DoyouknowthatI’mstillnotapproved?LikeI’mstill notapprovedtoputmoneyonherbooks,doanything. We’regoingoneightweeks.Ihavenobackground.I havenonothing.I’veneverbeenintrouble.I’vesent everybitofmypaperwork,mysocialsecuritycard, mydriver’slicense,everythingthattheyaskedmefor. Isenteverybitofthattothem.Literallyit’sbeen five weeks.AndwhenIcalledupthere,theysaidit’sdone quarterly.What?!

Furthermore,caregiversreportedthatcarceralpolicies willnotallowanyoneonprobationorparoletobeplacedon anapprovedvisitinglist.Thisisasignifi cantbarrierforthe severalcaregiverswhowerejustice-involvedthemselves. Lessfrequentlydiscussedbarrierstoin-personvisits includeddistancetothefacilityandmothersandcaregivers ’ preferencesagainstinpersonvisitsforchildren.Denise sharedthatacombinationofcartroublesandabusyschedulecoupledwithaseveralhourdrivetotheprisonpreventedherfromtakingtheinfanttovisittheincarcerated mother.Mariasharedthatshedidn’tfeelaprisonwasan appropriateplaceforchildren,stating: “I’lltellyouwhatI think.Ithinkit’snottherightplacetotakechildren.” Cynthiawantedtobringthemother’schildrentovisither, butthemotherdeclined,sayingshedidn’twantherchildren tovisit.

CaregiverSatisfactionwithAmountofContact

Atotalof27(82%)ofthe33caregiversinthebirthtotwo monthssamplereportedbeingsomewhatorextremely satis fiedwiththeamountofcontactwiththeincarcerated mother.Similarly,20(95%)ofthe21caregiversinthe three-to-four-monthsamplewereeithersomewhator extremelysatis fiedwiththeamountofcontactwiththe incarceratedmother.Fifteencaregiverselaboratedonwhy theyweresatisfiedornotsatis fiedwiththeamountof contact.Mostcaregiversreportedthattheyweresatis fied becausetheincarceratedmotherwascontactingthemata highfrequency,uptomultipletimesaday.Indeed,caregiversthatrespondedthattheyweredissatis fi edorsomewhatdissatisfiedoftenelaboratedbysayingthatcontactwas curtailedbyinstitutionalorschedulingbarriers.Sarah,who describedherexperienceas “aboutinthemiddle,” acknowledgedduringherthree-monthinterviewthat “we can’tcontactheras-well,asmuchaswe’dlike.” Extended responsesalsorevealedthatwhilethemajorityofcaregivers reportedhighsatisfactionwiththeamountofcontact,they feltthatthetypeofcontactthattheywereabletoachieve (primarilyphonecalls)wasnotthetypeofcontactdesired.

Forexample,Brendareportedonthequantitativequestion thatshewas “extremelysatis fied” withtheamountof contactwiththeincarceratedmother,butwentontosay: “I wishwehadanoption Ifshewasinthecountythatwe’re livinginwecouldFaceTimewithherandthatwayyou knowtheycouldseeeachother[and]thatkindofstuff,so, thatwouldbeideal”

QualitativeThemes

Thethematicanalysisyieldedtwobroadthemesthatdeepenedcontextualizedquantitative fi ndingsdescribedabove: “Mothersdesireforconnectionandcollaboration” and “Caregiversstrategiesforresilienceinthefaceofbarriers. ” 87%ofparticipantscontributingdatatothebirthtotwo monthtimepointand100%ofparticipantscontributing datatothethreetofourmonthtimepointprovidedcontent thatledtothedevelopmentofthesetwothemes.

Mothers’ DesireforConnectionandCollaboration

Caregiversdiscussedthatmothersdeeplydesiredtobein contactwiththeirinfantsandfrequentlyattemptedtomake contact.Thebarriersdescribedabovemeantthatformost mothers,phonecallsweretheonlyformofreal-time communicationtheycouldhavewiththeirinfant.Caregiversalmostuniversallyacknowledgedthemother’sdesire toseeandtouchtheirinfant,adesiretheyregrettednot beingabletofulfillduetoinstitutionalbarriersorthe busynessoftheirownlives.Bethsharedthatpolicies restrictingvisitswereasourceofsigni ficantstressforthe mother:

Notbeingabletosee[her]isthebiggestchallenge. Youknow,ifIcouldtakehimonceaweekandvisit her,Ithinkthatwouldbeagoodthing.Itwouldwork. Imean,Icouldworkitinmyscheduleaswellasit wouldgiveherhope… evenrightnowI’mhaving problemsbecausesheisverydepressed.Shewantsto seeherbaby.She’safraidshe’sgoingtoforgetwhat thebabylookslike.Allshewantstodoishold herbaby.

Unabletoseetheirinfantsinperson,caregiversreported thatmothersaskedforphotos,shortvideoclips,orvideo chatswiththeirinfants.Thefewcaregiversthatwereableto dovideochatsinthe firstthreemonthsstatedthatmothers werethrilledtoseetheirinfants.Bethsaid: “She[the mother]loves[videochats].Shecallsrightafterwardsand [says]thathishairlookedlikethat…askingdifferentthings. She’sverydetailed.”

“I’llmakesureheknowsyou:” caregivers’ strategies forresilienceinthefaceofbarriers

Whileacknowledgingthattakingtheinfanttovisitthe motherwouldbetheidealwayforthemotherandinfant tobond,caregiversworkedhardtopursueotherstrategies tofosterconnectionbetweentheincarceratedmotherand herinfant.Thesestrategiesincludedputtingthemother onspeakerphonesotheinfantcouldhearhervoice, sharingmilestonesandotherinformationabouttheinfant, sendingpicturesorvideosoftheinfanttothemother,and talkingaboutandshowingpicturesofthemothertothe infant.Caregiversstatedthattheywantedtheinfantto hearthemother,andthattheinfantrespondedtothe mother ’ svoice.Rhondasharedthatwhenthemother called,andthebabywasawake: “ I ’ llputher[theinfant ’ s] faceuptoitandthen[theinfant]goeslaughin ’ andstuff. Andshe[themom]says ‘ Yeah,[it ’ s]Mama!What ’ s Mama ’ sbabytalkingabout? ’ Andthenshe ’ lljustscream outatyou. ”

Inadditiontolettingtheinfantheartheirmother’svoice, caregiversreportedusingphonecallstokeeptheincarceratedmotherabreastoftheinfant’sdevelopment.Dawn describedatypicalphonecall:

“Iwilllethertalktoheronthephone.I’lllet[child’s mother]talktothebaby,andlether thebabyhear hervoice,andjust[tellher]differentmilestoneslike, youknow,liftin’ herheadupandmovin’ aroundand eyecontactand,youknow,justthingslikethat,her development.”

Whilemostcaregiverssharedthattheytriedtotellthe mothereverythingabouttheinfant,somedescribedbeing carefultoonlysharepositiveinformationoutoffearof upsettingthemother.Amysaid: “SomethingsIknowwill makehersad,soItrynotto[share].Justlike,youknow, howbabieschangesoquickly,Idon’treallytalktoher aboutthat.Buteverythingelse,wetalkabout.”

Caregiversalsosentinpicturesandshortvideoclipsof theinfantsothattheirmothercouldseetheinfant’sgrowth overthe fi rstthreemonths.Stacyreportedthatpicturesand videomessagesweretheprimarywaythatshekeptthe infant’smotherinvolvedinthe fi rstthreemonths.

Finally,afewcaregiversmadesuretoshowtheinfant picturesofthemotherandtalkaboutthemother,despitethe infant’syoungage.Davidusedtheincarceratedmother’s pictureasascreensaverontheirtelevision.Jasmine describedthewaysinwhichshetriedtoensurethatthe babywouldknowhismother:

“Ijustbasicallytellherthat,youknow,I’llmakesure heknows[you].I’llshowhimpicturesandthingsto explaintohim,notsomuchofwhat’sgoingon,but howshewantedtobehere,butwiththedecisionsshe madeshecan’tatthismoment.Sothatwhenshegets

homeshewillbeafamiliarfacetohim,soitwon’tbe sohardforher Shewantsmetomakesureheknows whosheis.”

Discussion

Thismixedmethodsstudyfoundthatcaregiversand mothersmostfrequentlyachievecontactthroughthephone andthatphoneisalsothemost-utilizedmethodfor remainingincontactwiththeinfant.Phonecontactoccurred quitefrequently.Mostcaregiversreportedcallsatleastonce aday.Noinfantsinoursamplewereabletovisitmothers andonlytwoinfantsexperiencedvideovisitswiththeir mothers(ResearchQuestion1).WhiletheCOVID-19 pandemicwasasignifi cantbarriertoin-personvisitsprior to2022,similarto fi ndingsinotherresearchwithincarceratedindividualsduringthepandemic(Charlesetal., 2022),visitingalsodidnotoccurforinfantsbornafter pandemic-relatedvisitingpolicieswereremoved.This findingsuggeststhatotherinstitutionalbarriersalsoprevent visits.Indeed,caregiverscitedthelengthyvisitapproval processesandotherinstitutionalfactors(distancetothe facility,policiespreventingjustice-involvedfamiliesfrom visiting)asobstaclestoin-personvisits,inlinewithprior researchwithincarceratedparents(Jensenetal. 2023) (ResearchQuestion2).Thetwothemesidentifi edinour thematicanalysis: “Mothersdesireforconnectionandcollaboration” and “Caregiversstrategiesforresilienceinthe faceofbarriers” illustrateadeepdesirefrommothersand caregiverstofacilitatematernal/infantcontactandsignificantcaregiverinvestmentinthisgoalhinderedbysevere institutionalbarriers.Caregiversvaluedconnectionbetween incarceratedmothersandtheirinfantsandworkedtokeep moneyavailableforfrequentphonecalls,sendpicturesand videomessages,and,whenpossiblegiveninstitutional barriers,initiatevideovisits(ResearchQuestion3).

Asdescribedintheintroduction,manyincarcerated motherswillbereleasedwithinthe firstthreeyearsoftheir children’slives.Indeed,15%oftheinfantsinourstudy reuni fiedwiththeirmotherbeforetheywerefourmonths old.Lackofcontactbetweenincarceratedmothersandtheir infantsthreatenstheformationofahealthymaternal/child relationshippostrelease.Whilethisstudywasunableto assesstheimpactoflackofinpersonorvideovisitson maternal/infantrelationships,otherstudieshavelinkedearly lifematernalseparationduetoincarcerationtochildren’s insecureattachmentrelationshipswiththeirmothers(Byrne etal. 2010;Poehlmann, 2005a).Theresultsofourstudy suggestthatinfantsborntoincarceratedmothersmayhave evenlesscontactthanolderchildrenwithincarcerated mothers.Thisseverelackofcontactmayputinfantsbornto

incarceratedmothersatevengreaterriskoflaterattachment issues.

Ourstudyhasimportantimplicationsforbothstateand carceralpolicies.Thecourtshaveruledrepeatedlytodefer toprisonandjailadministratorsinsettingvisitingpolicies (Boudin,Stutz&Littman, 2013).Thus,visitingreformis primarilyatthediscretionofcarceralfacilityadministrators. Thisstudyfoundthatsignifi cantinstitutionalbarrierstoin personandvideovisitshavebeenimplementedbycarceral facilities,suchaslengthypaperworkrequirements,exclusionofjustice-involvedlovedones,andCOVID-19related visitationpolicies.Giventhedocumentedimportanceof visitsformaternal,child,andfamilywellbeing,weurge DepartmentsofCorrectionsandothercarceralfacilitiesto developandmaintainpoliciesthatpromotehigh-quality contactbetweenincarceratedmothersandtheirinfants.In additiontorecommendationsdevelopedforschool-aged childrenvisitingtheirincarceratedparent(PoehlmannTynan&Pritzl, 2019),weofferseveralinfant-speci fic recommendations.First,ourstudyfoundthatvisiting approvalprocessessignificantlydelayedtheabilityfor childrentoseetheirmothers.Thus,theseprocessesshould bestreamlinedtopreventlengthydelaysinapprovalfor bothinfantsandcaregivers.Infantsbornduringtheir mother’sincarcerationarealreadyknowntotheDepartment ofCorrections;requiringthatcaregiverssubmitmultiple infant-relateddocumentstobringtheinfanttovisitaddsan unnecessaryburdentocaregivers.Inaddition,carceral facilitiesshouldworktodevelopvisitingprogramsunique toincarceratedmothersofinfants.Weofferseveral recommendationsfordevelopmentallyappropriatevisits. First,caregiversreporteddiffi culty fi ttingvisits,whichoften occurseveralhoursawayfromtheirhomes,intotheirbusy lives.Carceralfacilitiesshouldoffervisitinghoursasfrequentlyaspossible,particularlyduringweekendsand holidays,sothatcaregiverscanmoreeasily fi tvisitsinto theirbusyschedules.Second,whileourstudywasnotable toassessthequalityofin-personvisitsasnoneofthe caregiversachievedavisit,werecommendthatfacilities keepinmindthedifferencesbetweenschool-agedchildren andinfantswhendevelopingvisitationpolicies.Facilities shouldholdvisitsbetweeninfantsandtheirmothersina separateroomspeci ficallydesignedforthispopulation.This roomshouldhaveaccesstodiapers,rockingchairs,changingtables,cribs,andothersoftspacestofacilitatecomfortableandnaturalparentingactivities.Policiesshouldnot onlyallow,butencouragephysicalcontactbetweenmothers andinfants,includingbreastfeedingifthemotherdesires.

Ofcourse,theneedforinfant-friendlyvisitingpolicies wouldbegreatlyreduced,ifnoteliminated,ifstatesfocused oneffortstodecarceratepregnantandpostpartummothers. Community-basedalternativestoincarcerationaregaining tractionasapolicyinterventionthatpromoteseducationand

rehabilitationoutsideofcarceralfacilities.Statesshould considercommunity-basedalternativesforpregnantand postpartummothersasaninterventiontopromoteboth maternalandinfantwellbeing.

Althoughthisstudywasabletocontributetothesparse literatureoncontactbetweenincarceratedmothersandtheir childrenbydescribinginfants’ contactwithincarcerated mothers,moreresearchisdesperatelyneeded.Future researchshouldcontinuetoassesscontactbetweenincarceratedmothersandveryyoungchildren,particularlyin otherstatesandinjailsorimmigrationdetentionfacilities.It isparticularlyimportanttoassesspotentialpredictorsof lackofcontactbetweeninfantsandtheirmotherstodesign effectivesupportprograms.Critically,researchersshould alsoidentifyandevaluateinfant-friendlyvisitingprograms outsideofprisonnurseriestoprovideanevidence-basefor thispopulation.Finally,futureresearchshouldassessthe impactofcontactbetweenmothersandtheirinfantson attachmentandotherdevelopmentaloutcomes.

Whilethisstudywasthe firsttoourknowledgeto describecontactbetweenincarceratedmothersandtheir infantswhowerenotinaresidentialnurseryprogram,ithas severalimportantlimitations.First,wewereunableto assesstheimpactoflackofmaternalcontactonattachment orotherinfantoutcomes.Second,wewereunableto includemotherperceptionsofcontactduringtheirincarceration.Finally,thisstudywasgeographicallylimitedto Georgia,threateningthegeneralizabilityofour findings.

Conclusion

Contactbetweeninfantsbornduringtheirmother’sincarcerationandtheirmothersisseverelylackingandwoefully inadequatetoinfants’ developmentalneeds.Caregiversare preventedfromfacilitatinghighqualitycontactbetween infantsandtheirmothersbyseveralinstitutionalbarriers. Basedonour fi ndingsthatinstitutionalbarrierspreventinpersonvisitsbetweenincarceratedmothersandourinfants, weurgecarceralfacilitiestoimplementpoliciestoease accesstovisits,includingsimplifyingpaperworkrequirementsandexpandingvisitinghourstopromotedevelopmentallyappropriatevisitsbetweenincarcerated mothersandtheirinfants.Visitationpolicyreformis particularlyurgentastheU.S.incarceratessuchalarge percentageofwomen,particularlywomenwithyoung children.Statesshouldconsiderpassingcommunity-based alternativestoincarcerationforpregnantandpostpartum motherstopromotehealthymaternalandchild relationships.

Authorcontributions BethanyKotlarwasprimarilyresponsiblefor thestudyconceptionanddesignincollaborationwithallcoauthors.

Materialpreparation,datacollection,andanalysiswereperformedby KimberlyPiontowskiandBethanyKotlar.The firstdraftofthearticle waswrittenbyBethanyKotlar,KimberlyPiontowski,andJennifer Lao.Allauthorscommentedonpreviousdraftsandreviewedthe final draftofthearticle.

Funding ThisprojectwaspartiallyfundedbytheHRSACenterof ExcellenceinMCHgrant,T03MC07648-12-06.BethanyKotlar’s workonthisprojectwasfundedbytheReproductivePerinataland PediatricEpidemiologyFellowship,T32HD104612.

Conflictsofinterest Thereareno financialconflictsofinterestto declare.BethanyKotlarservedasanunpaidBoardmemberfor MotherhoodBeyondBarsfrom2019until2022.

Ethicsapproval ThisstudywasapprovedbyHarvardLongwood MedicalArea’sInstitutionalReviewBoardthroughIRB20-1215;211247.

InformedConsent Studyparticipantscompletedaninformedconsent processandconsentedtopublicationofunidenti fiabledata.

References

Alexander,M.(2012). ThenewJimCrow:Massincarcerationinthe ageofcolorblindness(Revisededition.).TheNewPress. Arditti,J.A.(2003).Lockeddoorsandglasswalls:Familyvisitingata localjail. JournalofLossandTrauma, 8(2),115–138. https://doi. org/10.1080/15325020305864.

Arditti,J.A.,&Few,A.L.(2006).Mothers’ reentryintofamilylife followingincarceration. CriminalJusticePolicyReview, 17(1), 103–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403405282450

Arditti,J.A.,&McGregor,C.M.(2019).Afamilyperspective: Caregivingandfamilycontextsofchildrenwithanincarcerated parent.InJ.M.Eddy&J.Poehlmann-Tynan(Eds.), Handbook onchildrenwithincarceratedparents:research,policy,and practice (pp.117–130).SpringerInternationalPublishing. https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16707-3_9

Beckmeyer,J.J.,&Arditti,J.A.(2014).Implicationsofin-person visitsforincarceratedparents’ familyrelationshipsandparenting experience. JournalofOffenderRehabilitation, 53(2),129–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2013.868390

Benoit,D.(2004).Infant-parentattachment:Definition,types,antecedents,measurementandoutcome. Paediatrics&childhealth, 9(8),541–545. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/9.8.541

Boudin,C.,Stutz,T.,&Littman,A.(2013).Prisonvisitationpolicies: A fifty-statesurvey.YaleLaw&. PolicyReview, 32(1),149–189. Bowlby,J.(1982). Attachmentandloss.2nded.BasicBooks. Braun,V.,&Clarke,V.(2006).Usingthematicanalysisinpsychology. QualitativeResearchinPsychology, 3(2),77–101. https:// doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Butcher,K.F.,Park,K.H.,&Piehl,A.M.(2017).ComparingApples toOranges:DifferencesinWomen’sandMen’sIncarcerationand SentencingOutcomes. JournalofLaborEconomics. https://doi. org/10.1086/691276

Byrne,M.W.,Goshin,L.S.,&Joestl,S.S.(2010).Intergenerational transmissionofattachmentforinfantsraisedinaprisonnursery. Attachment&HumanDevelopment, 12(4),375–393. https://doi. org/10.1080/14616730903417011.

Carson,E.A.,&Kluckow,R.(2023).Prisonersin2022 – statistical tables(No.307149). BureauofJusticeStatistics https://bjs.ojp. gov/document/p22st.pdf

Charles,P.,Muentner,L.,Gottlieb,A.,&Eddy,J.M.(2023).Parentchildcontactduringincarceration:Predictorsofinvolvement amongresidentandnonresidentparentsfollowingreleasefrom prison. SocialServiceReview, 97(1),169–213. https://doi.org/10. 1086/723450.

Charles,P.,Muentner,L.,Jensen,S.,Packard,C.,Haimson,C.,Eason, J.,&Poehlmann-Tynan,J.(2022).IncarceratedDuringaPandemic:ImplicationsofCOVID-19forJailedIndividualsand TheirFamilies.Corrections(2377–4657), 7(5),357–368. https:// doi-org.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/10.1080/23774657.2021. 2011803

Dallaire,D.H.,Ciccone,A.,&Wilson,L.C.(2012).Thefamily drawingsofat-riskchildren:Concurrentrelationswithcontact withincarceratedparents,caregiverbehavior,andstress. Attachment&HumanDevelopment, 14(2),161–183. https://doi. org/10.1080/14616734.2012.661232

Fair,H.,&Walmsley,R.(2022). WorldFemaleImprisonmentList. WorldPrisonBrief https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/ files/resources/downloads/world_female_imprisonment_list_5th_ edition.pdf.

Fessler,S.R.(1991).Mothersinthecorrectionalsystem:Separation fromchildrenandreunificationafterincarceration.[Doctoral dissertation,StateUniversityofNewYorkatAlbany].ProQuest DissertationsPublishing.

Gholampour,F.,Riem,M.M.E.,&vandenHeuvel,M.I.(2020). Maternalbrainintheprocessofmaternal-infantbonding:Review oftheliterature. SocialNeuroscience, 15(4),380–384. https://doi. org/10.1080/17470919.2020.1764093

Heimer,K.,Malone,S.E.,&DeCoster,S.(2023).Trendsinwomen’s incarcerationratesinUSprisonsandjails:Ataleofinequalities. AnnualReviewofCriminology, 6(1),85–106. https://doi.org/10. 1146/annurev-criminol-030421-041559 .

Hennink,M.,&Kaiser,B.N.(2022).Samplesizesforsaturationin qualitativeresearch:Asystematicreviewofempiricaltests. SocialScience&Medicine, 292,114523 https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.socscimed.2021.114523

Houck,K.,&Loper,A.(2002).Therelationshipofparentingstressto adjustmentamongmothersinprison. AmericanJournalof Orthopsychiatry, 72(4),548–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/00029432.72.4.548

Howard,D.L.,Strobino,D.,Sherman,S.G.,&Crum,R.M.(2010). MaternalIncarcerationDuringPregnancyandInfantBirthweight. MaternalandChildHealthJournal,15(4),478–486. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10995-010-0602-y

Jensen,R.(2021).Pregnancyduringincarceration:A “serious” medical need. BrighamYoungUniversityLawReview, 46(2),529–569. Jensen,S.,Pritzl,K.,Charles,P.,Kerr,M.,&Poehlmann,J.(2023). Improvingcommunicationaccessforchildrenwithincarcerated parents. Contexts, 22(1),76–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 15365042221142847

Kajstura,A.(2018). Statesofwomen’sincarceration:theglobal context2018.RetrievedMarch7,2021,From https://www. prisonpolicy.org/global/women/2018.html

Knight,M.,&Plugge,E.(2005).Theoutcomesofpregnancyamong imprisonedwomen:Asystematicreview. BJOG:AnInternationalJournalofObstetricsandGynaecology, 112(11), 1467–1474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00749.x.

Kotlar,B.,Kotlar,A.,Jimenez,M.,Sufrin,C.,Yousafzai,A.,Shlafer, R.,&Tiemeier,H.(2025a).BrokenBonds:CaregivingStability AmongInfantsExposedPrenatallytoMaternalIncarceration. JournalofChildandFamilyStudies,1–14. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s10826-025-03082-3

Kotlar,B.,Yousafzai,A.,Sufrin,C.,Jimenez,M.,&Tiemeier,H. (2025b). “Thesystem’snotgettingmygrandchild”:Aqualitative studyofcaregiverrelationshipformationforchildrenbornto

incarceratedmothers. SocialScience&Medicine,117881. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2025.117881

Loper,A.B.,&Clarke,C.N.(2013).Attachmentrepresentationsof imprisonedmothersasrelatedtochildcontactandthecaregiving alliance:Themoderatingeffectofchildren’splacementwith maternalgrandmothers. MonographsoftheSocietyforResearch inChildDevelopment, 78(3),41–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/ mono.12020

Loper,A.B.,Carlson,L.W.,Levitt,L.,&Scheffel,K.(2009).Parentingstress,alliance,childcontact,andadjustmentofimprisonedmothersandfathers. JournalofOffenderRehabilitation, 48(6),483–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509670903081300 Mumola,C.J.(2000).Incarceratedparentsandtheirchildren.U.S.Dept. ofJustice,OfficeofJusticePrograms,BureauofJusticeStatistics. Muzik,M.,Bocknek,E.L.,Broderick,A.,Richardson,P.,Rosenblum, K.L.,Thelen,K.,&Seng,J.S.(2013).Mother–infantbonding impairmentacrossthe first6monthspostpartum:Theprimacyof psychopathologyinwomenwithchildhoodabuseandneglect histories. ArchivesofWomen’sMentalHealth, 16(1),29–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0312-0 .

NelsonC.A.&Bosquet,M.(2000).Neurobiologyoffetalandinfant development:Implicationsforinfantmentalhealth.InC.H. Zeanah,Jr.(Ed.), Handbookofinfantmentalhealth,(2nded.,pp. 37–59).TheGuilfordPress. Pendleton,V.E.,Schmitgen,E.M.,Davis,L.,&Shlafer,R.J.(2021). Caregivingarrangementsandcaregiverwell-beingwheninfants areborntomothersinprison. JournalofChildandFamily Studies, 31(7),1894–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-02102089-w

Pettit,B.,&Western,B.(2004).Massimprisonmentandthelife course:RaceandclassinequalityinU.S.incarceration. American SociologicalReview, 69(2),151–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 000312240406900201

Poehlmann,J.(2005b).Representationsofattachmentrelationshipsin childrenofincarceratedmothers. ChildDevelopment, 76(3), 679–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00871.x

Poehlmann,J.(2005a).Children’sfamilyenvironmentsandintellectualoutcomesduringmaternalincarceration. JournalofMarriage andFamily, 67(5),1275–1285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17413737.2005.00216.x

Poehlmann,J.,Shlafer,R.J.,Maes,E.,&Hanneman,A.(2008). Factorsassociatedwithyoungchildren’sopportunitiesfor maintainingfamilyrelationshipsduringmaternalincarceration. FamilyRelations, 57(3),267–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17413729.2008.00499.x

Poehlmann,J.,Dallaire,D.,Loper,A.B.,&Shear,L.D.(2010). Children’scontactwiththeirincarceratedparents:Research findingsandrecommendations. AmericanPsychologist, 65(6), 575–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020279

Poehlmann-Tynan,J.(2015).Children'scontactwithincarceratedparents: Summaryandrecommendations.InJ.Poehlmann-Tynan(Ed.), Children’scontactwithincarceratedparents:Implicationsforpolicy andintervention(pp.83–92).SpringerInternationalPublishing/ SpringerNature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16625-4_5

Poehlmann-Tynan,J.,&Pritzl,K.(2019).Parent-childvisitswhen parentsareincarceratedinprisonorjail.InJ.M.Eddy&J. Poehlmann-Tynan(Eds.), Handbookonchildrenwithincarceratedparents:Research,policy,andpractice (2nded.,pp. 131–147).SpringerNatureSwitzerlandAG. https://doi.org/10. 1007/978-3-030-16707-3_10

Poehlmann-Tynan,J.,Runion,H.,Burnson,C.,Maleck,S.,Weymouth,L.,Pettit,K.,&Huser,M.(2015).Youngchildren’s behavioralandemotionalreactionstoplexiglasandvideovisits withjailedparents.InJ.Poehlmann-Tynan(Ed.), Children’ s

contactwithincarceratedparents:Implicationsforpolicyand intervention (pp.39–58).SpringerInternationalPublishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16625-4_3

Roberts,D.E.(1997). Killingtheblackbody:Race,reproduction,and themeaningofliberty.1sted.PantheonBooks.

RodriguezCarey,R.(2019). “Who’sGonnaTakeMyBaby?”:Narrativesofcreatingplacementplansamongformerlypregnant inmates. Women&CriminalJustice, 29(6),385–407. https://doi. org/10.1080/08974454.2019.1593919

Shlafer,R.J.,Loper,A.B.,&Schillmoeller,L.(2015).Introduction andliteraturereview:Isparent-childcontactduringparental incarcerationbeneficial?InJ.Poehlmann-Tynan(Ed.), Children’scontactwithincarceratedparents:Implicationsforpolicy andintervention (pp.1–21).SpringerInternationalPublishing/ SpringerNature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16625-4_1.

SkoraHorgan,E.,&Poehlmann-Tynan,J.(2020).In-homevideochat betweenyoungchildrenandtheirincarceratedparents. Journalof ChildrenandMedia, 14(3),400–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 17482798.2020.1792082

Snyder,Z.K.,Carlo,T.A.,&Mullins,M.M.C.(2001).Parenting fromprison:Anexaminationofachildren’svisitationprogramat awomen’scorrectionalfacility. Marriage&FamilyReview, 32(3-4),33–61. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v32n03_04

Stringer,E.C.,&Barnes,S.L.(2012).Motheringwhileimprisoned: Theeffectsoffamilyandchilddynamicsonmotheringattitudes. FamilyRelations, 61(2),313–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17413729.2011.00696.x

Sufrin,C.,Jones,R.K.,Mosher, W.D.,&Beal,L.(2020).Pregnancy prevalenceandoutcomesinU.S.jails. ObstetricsandGynecology, 135(5),1177–1183. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000003834

Sufrin,C.,Beal,L.,Clarke,J.,Jones,R.,&Mosher,W.D.(2019). PregnancyoutcomesinUSprisons,2016-2017. AmericanJournalofPublicHealth, 109(5),799–805. https://doi.org/10.2105/ AJPH.2019.305006

Tasca,M.(2016).Thegatekeepersofcontact:child–caregiverdyads andparentalprisonvisitation. CriminalJusticeandBehavior, 43(6),739–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854815613528 .

Testa,A.,&Jackson,D.B.(2020).IncarcerationExposureDuring PregnancyandInfantHealth:ModerationbyPublicAssistance. TheJournalofPediatrics, 226,251–257.e1. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.jpeds.2020.06.055

Thompson,M.(2021). Motherhoodafterincarceration:Community reintegrationformothersinthecriminallegalsystem.(Routledge,Taylor&FrancisGroup.

Tuerk,E.H.,&Loper,A.B.(2006).Contactbetweenincarcerated mothersandtheirChildren:Assessingparentingstress. Journalof OffenderRehabilitation, 43(1),23–43. https://doi.org/10.1300/ J076v43n01_02

UnitedStatesSentencingCommission.(2018).Quickfacts:Female offenders, fiscalyear2018. https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/ files/pdf/research-and-publications/quick-facts/Female_ Offenders_FY18.pdf

Waters,E.,&Cummings,E.M.(2000).Asecurebasefromwhichto explorecloserelationships. ChildDevelopment, 71(1),164–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00130

Publisher’snote SpringerNatureremainsneutralwithregardto jurisdictionalclaimsinpublishedmapsandinstitutionalaffiliations.

SpringerNatureoritslicensor(e.g.asocietyorotherpartner)holds exclusiverightstothisarticleunderapublishingagreementwiththe author(s)orotherrightsholder(s);authorself-archivingoftheaccepted manuscriptversionofthisarticleissolelygovernedbythetermsof suchpublishingagreementandapplicablelaw.