What better way for PMA Magazine to celebrate its 2nd anniversary than to offer you its first hard copy of some of its articles along with the official audiofest program?

Owned by the Toronto and Montreal Audiofests, PMA Magazine is the third project we've launched to help promote the audio and video industries. PMA Magazine not only provides a showcase for brands, stores, and manufacturers, but also for audio enthusiasts like you who want to talk about their passion, their journey, their home audio setup, with like-minded people.

We invite you to subscribe to our free weekly newsletter by visiting pmamedia.org and get a chance to win a pair of Grado RS2x headphones worth $750.

We wish you an excellent visit at the audiofest 2022; 5 floors of listening rooms are waiting for you. Take your time; we're here for three days.

Thanks so much for your support!

PS: Please don't forget to keep silent during the listening sessions!

Sarah and Michel

Friday 11 a.m. – 8 p.m. Saturday 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. Sunday 10 a.m. – 5 p.m.

04 exhibitors

exhibitors

08 "No, I have the best system in the world!" #7

brands

brands 15 brands

floor plan

My (factory) trip to (the) MOON by Simaudio

29 An Interview with André Perry

Absolute Sound 353

Acora Acoustics Corporation Sutton C

All that Jazz L_7

Alta Audio Balmoral

Altitudo Audio Plaza B

Angela Yeung - Gilbert Yeung 353

Anne Bisson 2_3

Anthem Electronics 439

Apple Tree Hifi 443

ASONA Carlton, 2_2

Audio by Mark Jones Easton, 227

Audio Sensibility 2_6

Audioarcan 351 AudioExcellence Sutton C

AudioGroup Lobby

AudioNote UK 346 Audioville Lobby

Baetis Audio 437 Bluesound Plaza A

Bowers & Wilkins 343, 345

BSC Research 443

Cambridge Audio 358, 360

Cardas Cables Mayfair

Centre Hi Fi North Atmosphere

Charisma Audio 363

Classé 343

Coherent Speakers 437, Bristol A

Constellation Audio 441

see also floorplans on page 22 and 23

Corby's Audio Balmoral, Dixon, Bristol A Crown Mountain Imports 227 CryoClear 2_8

DALI Sutton A

Definitive Technology 341 Denon 339 e

Elac Audio 358, 360

Entracte Audio 353 Eon Art Mayfair

EQ Audio Sutton B

Erikson Consumer Home 347, 356 exaSound 441 Executive Stereo 219

f FiiO 2_4 Focal-Naim Canada Sutton B, 446

Galion Audio 354

Gershman Acoustics Mayfair, 333 Grado Canada Lobby Gramophone Audio Distribution 452 Gutwire 333

Hearken Audio 448

Heretic Loudspeakers Co. 363

i Innuos Carlton IsoAcoustics 446

JVCKENWOOD Canada Inc. Windsor

Kaleidescape Sutton B

KEF Lobby, North Atmosphere

Kennedy HiFi 446, Plaza A Kimbercan Knightsbridge

L'Atelier Audio 448

Lenbrook International Sutton A, Plaza A, 2_1, 2_10, 2_11

Lii Song Canada 354

Madly Audacious Concepts Inc. 354 Magnepan 450

Marantz 341, 345

MoFi Distribution 349 MOON by Simaudio The Lounge

Motet Distribution Bristol B Muraudio 441

NAD Electronics Plaza A, 2_1, 2_10, 2_11

Nexus International Inc Knightsbridge Nordost 337

Oracle Audio Technologies Mayfair

Paradigm 439 Pass Labs 333

PMC Bristol B

see also floorplans on page 22 and 23

Polk Audio 339

PSB Speakers Plaza A, 2_1, 2_10, 2_11

Saturn Audio Ltd. Balmoral

Simcoe Audio Video L_11 Sonic Artistry 337

Sound United 339, 341, 343, 345

The Sound Organisation Dixon Toronto Home of Audiophiles Ltd. 333 Trends Electronic 358, 360 Tri-Art Audio 423 Tri-Cell Enterprises 219

Vinyl Sound 325, 349 w

Weiss 333 Wynn Audio Corp. Carlyle

Zidel Marketing 349

thanks to our sponsor and its partners

Paul’s system is one of those rare audiophile systems; its composed entirely of gear of the same brand, in this case, made by venerable Scottish company Linn. Paul’s system is Linn’s 5.0 Katalyst Surround System. Did you think that Linn was mostly about turntables and analogue? Only in a nostalgic sense.

Before I get into the specifics of Paul’s system—and believe me when I say that you’ll probably want to try something that Paul suggests—I wanted to say a word about same-brand systems. If we believe that the fundamental principle we’re looking for when putting together a system is synergistic performance, what can be more synergistic than a system built with components designed to specifically work with each other. Of course, when I say this, I’m not referring to the same-brand Japanese systems we were subjected to in the 80s that were constructed of paper-thin metal casings and blew out distortion instead of music when you were barely outputting 30Wpc. I’m talking about the real, high-grade stuff.

Linn, of course, made its name with its LP12 turntable, and even though the company remains generally better

known for its analogue championing, the company has, while some people weren’t looking, and despite initially taking its sweet time to start making digital products*, been at the forefront of digital audio engineering. Linn will celebrate its 50th anniversary next year.

“Linn was one of the first, if not the first, companies to come out with digital streaming for high-end stereo systems.,” Paul said to me from Vancouver, B.C., during our Zoom chat. “They’re on the cutting edge of digital streaming. I received their new Klimax DSM/3 hub/ streamer two days ago, which set me back the price of a new Honda Civic. I’m selling off a couple of other pieces from my system to cover a good chunk of the cost. But wow, it’s sound quality is incredible.”

I asked Paul about the moment when he realized he had a thing for audio. When was it? “Grade 12,” he said. “My friend’s father had a stereo console with a Garrard turntable. He played Led Zeppelin—I think it was “Whole Lotta Love”—and the music started and the guitar came out of the left speaker and the bass out of the right one, it went back and forth… that was the moment I knew I was hooked. (laughs) It was far beyond anything

I’d heard before. After that, I started saving everything I could for a better music system.

“My first system came from my parents. They bought me a little Seabreeze suitcase record player, on which you could stack about 6 records on the spindle. I was 20 years old, with a stack of records of Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Bach. So here I was, playing my own music.”

“Maybe that’s where it all started from,” I suggested. “The seed was planted.” “Oh, yes,” he said. “It’s been an unbelievable journey since then.”

I asked Paul how happy he was with the current state of his system. He shook his head in disbelief. “It’s one of the best, if not the best, systems I’ve heard, of any system.”

How was it different from his previous “best” systems? “I had budgetary constraints,” he said. “I was doing a surround-sound system, so I had to do everything in fives. If I had just bought a stereo system from Linn, all its top components but just stereo, it would have been easier. So I had to start at a lower level. With surround, you can’t have the best cables for your speakers in the front and inferior ones for the centre channel and the speakers in the back. It’s got to be the same all around if you want to get the full effect. I was just building and building. The hobby is as much about listening to music as it is tweaking and improving the system.”

Did he regret having gone the 5.1-channel route?

“Absolutely not,” he said. “I have a lot of 5.1 surround music. I’m now able to stream music that I’ve ripped from my SACDs, CDs, and DVD-Audio, put it on to my network-attached storage device, stream it through my OPPO Blu-ray player in 5.1, and the sound quality is unbelievable. The thing about surround music compared to stereo is that it completely immerses me in the music. It’s completely surrounding me, not unlike standing where the conductor would stand in a symphony, or being on stage with the band. It adds another dimension to listening. It’s very detailed. I think if you could come out here, it would be quite a surprise.” I told him I accepted his invitation; going to Vancouver was already in the cards for me this fall, and I’d love to pass by.

Did analogue still play a part in his audio journey?

“I’m totally digital streaming now,” he said. “But I visit friends who have top-of-the-line turntables—SME, the Linn LP12 Klimax—and I can truly say that in the absence of hearing the very best recordings played on a really exceptional turntable, digital streaming has now reached the point that it’s better than what most people will ever hear on a turntable.”

He added: “Now, had you asked me what I thought about the matter five years ago, I would’ve said that, no question, a great turntable with a well-recorded LP blows the doors off of digital. But I can’t say that now. I think that over 90% of the digital streaming that I’m hearing on my system is better than the sound of most turntables I’ve heard, even with the same recordings, and even off Tidal, which has improved so much. I also have a very good collection of 24bit stereo and surround sound music.”

Did he have a theory as to why digital sounds so good now? “The big difference happened in the last two years, with digital audio switches and ethernet cables,” he said. “They’ve taken the digital edge out of the music. Now, digital can sound so analogue that I think most people would have trouble determining if the sound is analogue or digital.”**

I asked Paul if anything had changed in his approach to the hobby. “I do a lot of my own explorations now, when before I used to rely completely on the sales people for their knowledge. Now I learn on my own. Plus, I’m very active on forums, so I’ve learned a lot from other people there. The other thing that really changed my perspective is that I somehow developed expertise in doing room optimization through Linn’s Space Optimisation software included in the Klimax DSM/3. I started by using it on stereos of people who live nearby, and after I’d gone to about 20 people’s homes, I gained enough confidence to go to Europe to do it. So, I’ve travelled for a month at a time or more, gone to twelve or so different countries, visited over 110 homes, to tune up people’s stereos to make them sound better. I’ve learned so much from these people and got so much hands-on experience in working and improvising with different systems.

Did his process include acoustic treatments? “I encourage people to use room acoustic treatments,” Paul said. “Because you can have a much less expensive system that sounds better than a more expensive one if you’ve got the right room acoustics. Depending on the room, I highly encourage using diffuser panels, absorption panels, and especially, if needed, bass traps. Many places have an issue with the bass.”

I can now make a $15-20,000 system sound like a $30-40,000 system. I tune a person’s stereo like a piano tuner tunes a piano.

Did his process include acoustic treatments? “I encourage people to use room acoustic treatments,” Paul said. “Because you can have a much less expensive system that sounds better than a more expensive one if you’ve got the right room acoustics. Depending on the room, I highly encourage using diffuser panels, absorption panels, and especially, if needed, bass traps. Many places have an issue with the bass.”

Tweak recommendations? “The three major things that I recommend, that really make a difference to everybody’s system, are:

“#1, clean power. There’s a lot of noise that comes through the power lines. Not only that, but the different pieces of equipment you have in your stereo can generate noise that affects the other components. So having a power supply is important. I use a waveform correction device from US-based Environmental Potentials, an industrial company that provides equipment to the medical field. It’s been phenomenal in my system. Power cables are also very important, but…

"#2, you have to keep the power cables away from signal cords. I’ve got my signal cables wrapped in copper tape, because nearby power cords give off an EMI signal that runs the length of the cable. If you’ve got your ethernet cables, or interconnects, or speaker cables near a power cord, you’re sucking the life out of the music. I also use copper shielding around my components to mitigate magnetic interference.

“#3 is vibration control. Under my equipment, I use IsoAcoustic Iso-Pucks under a Baltic birch aviation plywood shelf made by a company in Finland. The shelf has 16 layers and is 8mm thick. It’s super light but rigid and it rejects vibrations. It improves the timing and the level of detail like you wouldn’t believe. Vibration control is key if you want to get the best.”

His favourite part of the hobby? “My background is as a scientist, so being an audiophile is a journey of discovery. And I’ve loved music since I was a young child. So combining the audio journey with music has been phenomenal. And the friendships I’ve made going to people’s homes in England or Wales or Germany, well, those friendships have taken on an even greater importance than listening to music and the hobby. You can’t buy that kind of friendship at a hi-fi store.” (laughs)

I asked Paul to name the most important lesson he’d learned from his journey. “Don’t be afraid to try new things. When you go on the audio forums, there are people who like to discover and tweak and try to optimize their system to get the most out of it. Then there are people who are vehemently opposed to the idea that anything could make a difference. I’m certainly not in the second camp.”

“And yet you’re a scientist,” I told him. “And still you believe in such things as better audio cables.”

“I absolutely have heard so much of a difference that that’s why I keep doing it,” he said. “I have very good hearing. I’ve travelled to all these different homes in Europe belonging to people who are experienced audiophiles, musicians, concertgoers, and here I am with no formal musical training, able to tune their system to the way they want to hear it. It’s not just me tweaking it, these people are part of the process. I want them to hear it the way they want to hear it. After all this, I can absolutely say that these tweaks or these improvements with cables, with power, with vibration control are, without a doubt, real. It’s like transforming a Volkswagen Golf into a BMW M5.”

His favourite components in his system? “The new Klimax DSM/3 system that just arrived. Then my surround sound speaker system. I have 23 speaker drivers in my surround system. Each has its own channel of amplification and DAC. It’s all digital crossovers, so there’s very little phase distortion between the drivers. That eliminates muddiness and lack of clarity in the music. The sound is just seamless.

“Next I’d say are my two Environmental Potentials HPS waveform correction devices. Those, in combination with the new Cardas Clear Beyond power cords, have taken my system to a place I couldn’t dream of 4 months ago. I’m in audio heaven.”

Can’t wait to hear it, Paul.

Associated gear (all prices in CA$ unless otherwise noted):

Linn Klimax DSM/3 hub/streamer $26,000

Front speakers: Akubariks $60,000

Surround speakers: Akudoriks $8000

Akurate Exaktbox (drives the Akudoriks) $9000

Centre channel speaker: Akurate 225 $4000

Akurate Exaktbox 6 $6500 (sends digital signals to the Akurate 225)

Akurate 4200 amplifier $8000

AC conditioners: Environmental Potentials HPS $2500

Vibration control: $various Isoacoustic Gaia, Orea, and Iso-Puck devices

Baltic Birch Aviation plywood shelf Approx. 36 Euros made in Finland

OPPO 203 Blu-ray player n/a

Ethernet cables: Cardas Audio Clear $350 each

Interconnects: Linn Silver RCA $600 (connected between the Exaktbox and centre channel speaker)

Power cords: $various Shunyata Alpha Digital, Cobra, Cardas Clear Beyond

Room acoustic treatment $various (Vicoustic Extreme Bass traps, Primeacoustic diffusers and absorption panels, ATS absorption panels)

Silent Angel Bonn N8 audiophile switches $various

and a Bonn Forester F1 linear power supply (connected to Paul’s NAS)

Further notes: Linn’s proprietary Space Optimization software mitigates room modes below 80Hz and uses Space Optimization + to adjust time of flight from each speaker driver to the listening position. Stereo music is streamed directly from Paul’s NAS or from Tidal HD.

*Linn’s first digital product was the Karik, which came to market in 1993, 11 years after CD’s introduction.

** Shades of MoFi, anyone?

1

432 EVO 448

a

Accuphase Bristol B, Plaza B, 325, 333

Acora Acoustics Sutton C

Acoustic Solid 219

Acoustic System International Carlyle

ADOT 452

Aesthetix Plaza B

Allnic Audio

Balmoral, Dixon, Bristol A

Alluxity Audio Plaza B

Alta Audio Balmoral Analysis Plus Carlton

Angela Yeung - Gilbert Yeung 353 Anthem 439

Apertura Carlton April Sound 448

Aqua Acoustic Quality 448, 452 Aragon Sutton B Arcam 347

Audeze L_11

Audia Flight 452 Audience Sutton B Audio Exklusiv 363 Audio Hungary 437 Audio Sensibility 2_6

AudioControl Plaza B Audiolab 356 AudioNote UK 346, Bristol B, Sutton C AudioQuest Easton

Audiosource L_11

Audiovector 353, Plaza B Aune Audio 2_2

Auris Plaza B

Baetis Music 437

Balanced Audio Technology (BAT) 349 Benz Micro 325

Berkeley Audio 219 Bird of Prey 448

BIS Cable 353 Bluesound Plaza A, 2_1, 2_10, 2_11, L11

Bob’s Devices 363

Bowers & Wilkins 343, 345 BSC Research 443

c

Cambridge Audio 358, 360

Cardas Cables Mayfair, 219, Sutton C Cayin Carlton, 2_2

CH Precision Easton

Charisma Audio 363

CHORD Electronics Dixon

Classé 343

Codia Acoustic Design 363

Coherent Loudspeakers 437, Bristol A Combak Harmonix 448

Constellation Audio 441

Critical Mass System Carlyle CryoClear 2_8 Crystal Cable Carlyle

DALI Sutton A

Dan Clark Audio 2_2

Dan D'Agostino Sutton C darTZeel 337 Decware 354 Definitive Technology 341 Denon 339

Dr. Feickert Analogue 349 DS Audio Bristol A Dual 356

e

Elac Audio 358, 360 Electrocompaniet Plaza B Elipson Plaza B EMT Carlyle

Entracte Audio 353 Eon Art Mayfair eSseCi Design 227 exaSound 441

f

FiiO 2_4

Focal Sutton B, 446 Furutech 2_6, 325 Fyne Audio 353, 452

Galion Audio 354

Gershman Acoustics Mayfair, 333 GigaWatt 363

Goldmund Carlyle GoldNote Plaza B, 325 Grado Lobby Graham Slee 351 Grandinote 443

Gutwire Cables 333

h

Harbeth

Harmonic Technology

Heed Audio

Hegel Carlton,

Heretic

HiFi Rose

HifiMan

HRS

i Icon Audio

Ideon Audio

iFi

Ilumnia

Innuos Carlton, Sutton

Integrity HiFi

IsoAcoustics

Isol-8

Isotek

Jean Nantais

Joseph Audio

JVC

k

Karan Acoustics Carlyle

KEF

Lobby, North Atmosphere

Kimber Kable Knightsbridge, Sutton B Kimber Select Knightsbridge

Kinki Studio 363

Koetsu 349

Kuzma

Balmoral, Dixon, Bristol A

Lii Song 354

Linn Easton

Lumin Bristol B, 2_6, Balmoral, 333, 443

Lyric Audio 354 m

M2Tech 2_2

Madison Audio Lab 363 Magnepan 450 m

Marantz 341, 345 Mark Levinson 347 Marten North Atmosphere

recent article

Fremer

TEST 1: Inserting one or more DIY aluminum foil records into an advertised ultrasonic record cleaning machine, after use, one should see even dimpling on the foil of the test record, from the edge of the record to the dead wax area.

LEFT: IMAGE AFTER TEST OF AN ALUMINUM FOIL RECORD INSERTED IN POSITION #2 OF 4 PROCESSED BY THE KIRMUSS KA RC 1 ULTRASONIC RECORD GROOVE RESTORATION SYSTEM .

RESULT: WITH A 70 KHz PASSIVE RESONANCE ADDED TO A 35KHz EXCITED SONIC BATH, NOTICE THE GENTLE, EVEN CAVITATION SEEN FROM THE RECORD’S EDGE TO THE RECORD’S DEAD WAX AREA.

ABOUT THE KIRMUSS KA-RC-1 NOT JUST SURFACE CLEANS, RESTORES! IT’S PROVEN SCIENCE!

TEST 2: Using a Cavitation Meter: A multi-record ultrasonic cleaning machine should see the same measured reading between records indicating even cavitation from the edge of the record to the dead wax area. (Just as with the DIY aluminum foil test.)

RESULT: WITH THE KA-RC-1, EVEN CAVITATION MEASURED BETWEEN RECORDS 1&2, 2&3, 3&4, AND RECORD 4 AND THE WALL OF THE SONIC’S BATH.

Using a spray, one first ionizes the record as both water and the record repel each other as they have the same charge. The ionizing spray is applied over several cycles as the induced charge washes off between cycles. Sonic action is attracted to the record, first removing films left over from prior record cleaning methods, then the release agent where pops reside CAUSED BY DUST BEING CEMENTED into the hot record as they are stamped. RESTORED RECORDS COME OUT VIRTUALLY DRY AS A RECORD REPELLS WATER! No air or vacuum drying needed. One sees a gain of 1.3 dB to 4 dB over floor. YOUR NEEDLE NOW RIDES IN THE GROOVES AS PRESSED!

No cavitation measured in this 40 KHz and 120 KHz advertised ultrasonic cleaner

Uneven, or no Cavitation measured between records

a DIY style

m

Massif Audio Design 337

Melco Audio 353, 452

Merging Technologies 337

Métronome

Carlyle

Meze Audio 2_2

MICHI Sutton B

Mission 356 Miyajima Laboratory 448

Modulum Bristol B

Monitor Audio Sutton B

MOON The Lounge

MSB Sutton C Muraudio 441 Musical Fidelity Sutton B

n

NAD Sutton A, Plaza A, 2_1, 2_10, 2_11

Naim Sutton B, 353, 446 Neotech 2_8

New Horizon Carlton

Nordost 337, Plaza B Norstone Sutton B, Plaza B, 443

o

Ocellia cables 448 Oracle Audio Technologies Mayfair

p

Paradigm 439 Parasound 443 Pass Labs 333

Pathos Acoustics Carlton

Pierre-Etienne Léon Carlton Playback Designs 219 Plixir Power 452

PMC Bristol B, Plaza B

Polk Audio 339

Portento Audio 227 Prima Luna 443 ProAc 227, Easton

PS Audio Knightsbridge

PSB Speakers Plaza A, 2_1, 2_10, 2_11

Pure Fidelity 351 Puritan Audio Labs 448, 452

q

Q Acoustics Plaza B Quadraspire Knightsbridge, Sutton B r

Rega Dixon, 353 Revel 347

Rotel Sutton B

s

Saturn Audio Balmoral, Dixon, Bristol A

Sbooster 2_6, Balmoral

Shanling 2_2

Silent Angel 2_6

SolidSteel 349, Easton

Sony L_11

SOtM 2_6, Carlyle

Spendor Dixon

Stack Audio 354 Stax 2_2

Stenheim 337

Swisscable 353

Synergetic Research Plaza B Synthesis Carlton

t

T+A North Atmosphere Tektron 437

Thales Carlyle Thomas Schick 349, 448 Thorens 356

Tidal Audio Carlyle Track Audio 227 Transrotor 443, Sutton C Tri-Art Audio 423, Plaza B Triangle North Atmosphere, Plaza B Trilogy Audio Systems 227 Tzar DST 448

u

Uberlight Flex Sutton C v Velodyne 356 Vimberg Carlyle Vivid Audio 219 w Weiss 333

Well Tempered Lab 363

Wharfedale 349 Whest 349 Wireworld Sutton B, Plaza B x

X-quisite Carlyle XLO Cables Bristol B y Yamaha 353

z

Zidoo Bristol B, Plaza B

Written By Claude Lemaire

Written By Claude Lemaire

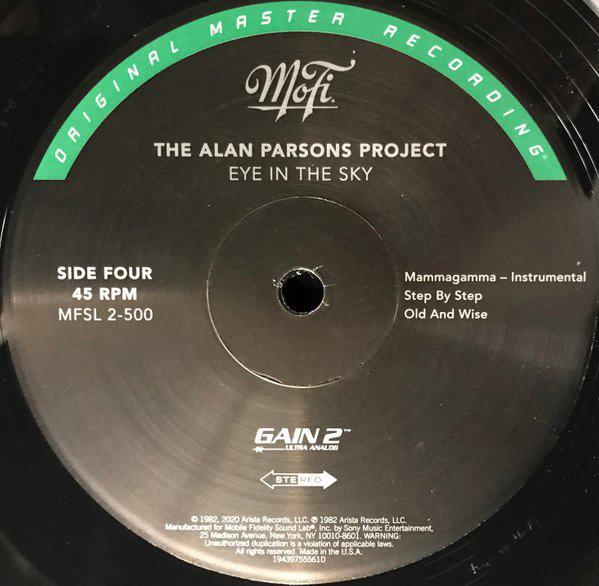

Global Appreciation: 9.6 / Music: B+ (8.7) / Recording: 9.7 / Remastering + Lacquer Cutting: 9.8 Pressing: 10 Packaging: standard, non-laminated gatefold / Category: soft rock, art rock, prog pop, prog rock. Format: Vinyl (2x180 gram LPs at 45 rpm).

Rare are the names that evoke as much respect in the fields of recording engineering and music creation as Alan Parsons.

It took a few tales of the imagination to get the motor running, but with Eric Woolfson, Andrew Powell, and a host of other musicians from Pilot and Ambrosia on board, there was no mystery as to where this train was headed.

Having cut his teeth at age twenty as an assistant engineer on none other than the Beatles's Abbey Road and Let It Be sessions, Parsons truly rose to prominence by engineering the landmark rock and audiophile favourite, Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon. Pink Floyd wished to keep him to work on Wish You Were Here, but Parsons had 'Projects' of his own in mind.

Inspired by writer and poet Edgar Allan Poe, the Alan Parsons Project's 1976 debut stood out among the progressive art rock world, at times drawing from symphonic impressionism. Not wanting to repeat the same formula, Parsons pursued a different direction with what would turn out to be his lifetime masterpiece— 1977's I Robot. Both albums were remastered at some point by MoFi, with the debut on their 200g ANADISQ 200 series in 1994, and the latter on three separate occasions: in 1982 for the regular LP, 1983 for the UHQR series, and in 2016 as its first double-45 rpm release.

As if that wasn't enough, two other versions of I Robot are already announced for future release in the form of MoFi’s UD1S "One Steps". 1978’s Pyramid would be the last great, complex work by the group, and strangely has never been remastered on double-45 rpm by anybody. MoFi, are you listening?

Eve followed in August 1979, and, like most progressive bands, Alan Parsons Project tried to adapt to their drastic dwindling popularity amid the emergence of new wave's shorter, simpler, and rawer music structure. Nevertheless, Eve spawned two hits—the incredibly infectious "Lucifer" and the devilish "Damned If I Do".

The turn of the decade saw the release of The Turn of a Friendly Card, which carried the radio hit single "Games People Play". The remainder of the album lacked memorable compositions and direction. Eye in the Sky was next in line and the last comeback before the steep decline in inspiration.

A 1/2" 30 IPS analog master was also run simultaneously at the time, perhaps as a parallel backup tape, considering mixing and mastering in digital was still in its early years back then. All recording and mixing were done at Abbey Road Studios in London, UK.

Warning: The following text may contain strong opinions. Reader discretion is advised.

By now you must be aware that since the last trimester, Planet "Audiophile" Earth has been gyrating around one singularity: the discovery of DSD256 within the Milky Way MoFi universe. Yes, a black hole has been sucking positive energy all around us, disrupting the normal flow of electrons and positrons in our daily lives. Here is my take on the whole antimatter:

First released in May 1982, it was the sixth of eleven albums the Alan Parsons Project released. Though much less complex than previous Parsons projects, it does contain the band's biggest hit—the title track. Naturally, Parsons produced and engineered the album, assisted by engineer Tony Richards. It was recorded on analog equipment, while mixed directly to digital tape with the digital master encoded by the then ubiquitous Sony PCM 1610 video tapebased system.

For us humans there are two things in life that are especially difficult to digest: the first is feeling deceived by a long-time partner in whom we put our trust; the second—and perhaps even harder for some to take—is having to admit that a preconceived conviction, as solid as it once seemed, may turn out to be unfounded. Each person will react differently but for me I was both shaken and stirred by the MoFi revelation. When such situations materialize, I try to search for a silver lining—and no, in this case I don’t mean a compact disc. Revisiting my vast collection of MoFi titles, I asked myself one simple question: Do they still sound as impressive as I found them in the past? And for the vast majority, the answer was a resounding yes! Of course, a few titles weren’t on the same sonic level as others, but that was always the case beforehand, just as with other competing labels. Granted, all this is a hard pill to swallow for some of us hardline analogue aficionados, but denying the truth would be merely lying to ourselves.

So what is that ray of sunshine stemming from Orion you may ask? Given how I and so many others have, for years, never detected any digital trace while playing our favorite MoFis, that sunny ray is the sudden realization that digital, in certain forms, can not only sound extremely transparent, but, dare I posit, maybe even surpass the sound of pure analogue when both technologies combine forces. Thinking about it, there is an analogy here with "analogue" film; yes, the film is moving in a continuous motion but it is, in a sense, projecting a series of individual frame-samples of an everchanging event, at a typical rate of 24 frames per second. Sound familiar? And does anybody look down on visual cinematic masterpieces such as Lawrence of Arabia simply because they’re played back via assembled frames?

The artwork follows MoFi's typical jacket presentation, which, when first introduced circa 2005, was superior to other remastering labels. Today, in 2022, the game has changed and MoFi faces strong competition from the likes of Tone Poet and Acoustic Sounds, which boast laminated gatefolds with beautiful internal photos.

As their source, engineer Krieg Wunderlich, assisted by Rob LoVerde, used the original 1/2" 30 IPS analogue master (not the original PCM 1610 digital master), which they converted to a DSD256 format. This was then passed through their analogue console to the cutting lathe. Plating and pressings were done at RTI in California and the records inserted in MoFi's standard HDPE inner sleeves, as well as a folded paperboard displaying the company’s releases. As usual with MoFi, the original label is replaced by their ubiquitous black one that now sports a green trim at the top. The vinyl was shiny, well centered, and dead silent throughout playback.

I do not have the original UK in my collection but do have a Canadian first press in mint condition bought when first released. It has a regular LP jacket but with a gold leaf for the eye motif. The matching green paper inner sleeve has the lyrics on one side and the credits on the flip side. Typical for the period, the vinyl is quite thin and floppy, probably around 120 grams, and both sides are visually similar with approximately a half-inch of dead wax.

On the other hand, MoFi's cover is a sturdy, non-laminated gatefold housing both 180g, 45 rpm-cut LPs, with lyrics and credits gold-printed on the interior. It would have been nice had they also added that gold leaf to the eye motif as a subtle clin d'oeil to the original artwork.

I always felt that the 1982 Canadian pressing was fairly good sounding and above average for that period. Studios were generally introducing more digital equipment and the music industry as a whole headed towards a higher level of dynamic compression before hitting the true loudness wars of the 1990s and beyond. That said, I did find that the tonal balance was close to neutral but a bit thin in the kick drum and bottom end, plus the upper mids were a bit too high in level due to some

over-compression, which discouraged cranking up the volume during listening. The soundstage was excellent and well balanced, as expected from an Alan Parsons production. Musically, I liked a lot the title track and its intro "Sirius", as well as the instrumental "Mammagamma", which resembles Pink Floyd's "Run Like Hell" from The Wall, but I felt the remaining songs lost my interest for some reason compared to Parsons’s earlier musical compositions.

relationship. It’s easy to distinguish the difference in timbre of the back vocals vs Woolfson's lead even during the overdubs. The quick snare roll after "I can cheat you blind" has that realistic snap, while the floor drum displays that thud you get with a firm tightened drum skin—these kinds of details are what separate the big boy remasterers from the rest. Just like MoFi’s previous I Robot double-45 rpm release, the tonal balance is full range and dead on, so much so that there is zero ear fatigue, sometimes leading to high volume levels over 90dB at the listening chair without me ever realizing it! Paradoxically the whole presentation sounds buttery smooth, yet the rhythmic fabric remains intact and the pace does

Simply put, this latest MoFi blows my mind and stomps all over the Canadian first press. From the onset, the first low vibration fades in and it is as if I energized my sub—the thing is I don't own a sub! Even at a low level you feel the deep low end and subsequent crescendo recalling the first time I witnessed the THX Deep Note intro in a wonderfulsounding THX-certified cinema. Then the famous Fairlight CMI-sampled clavinet riff-loop makes its entrance. This, in turn, is followed by the fade in of the powerful kick drum dead center stage that is punchier than in the Canadian first press. The guitar strikes’ every eight-beat intervals are more dramatic also; hi-hat comes in, then snare, and strings. It's as if the Romans are entering the Colosseum. The soundstage expands in all directions, the height seems to have no limit, my whole 700 square-foot basement audio room transforms into a virtual hologram awash in sound. Electric guitar enters and cuts in at just the right level, then fades out, leaving us with only the nearfield quick-panned synth delay over a black background sucking the air around us. We segue into the title track, and a huge sound bed appears that Goldilocks would pronounce as "just right", bearing the sonic hallmarks of JBL 4520 scoops sporting alnico woofers and horn lens tweeters playing in late-1970s discothèques. The snare has the perfect proportion of fast attack to get your foot tapping, and slow release to prolong the pleasure and create breathing space within the mix and rhythmic flow, i.e. what engineers call the ADSR sound parameters. The vocals come in at just the right level and warmth to communicate the singer's emotional disillusion and detachment regarding his

not slow down. The overall sound is full, warm, and lush, but never dull. Needless to say, I’m in ecstasy! "Children of the Sun" syncopates snare and hi-hat at breakneck speed with kick drum marking the metronomic pulse. It progresses into symphonic royalty and a military march that lets you feel the boots on the ground stomping on your doorstep.

Side B's "Gemini" melts in your ears as the celestial voice canon builds up with added reverb. The vocal envelope is truly heavenly and hints at the Beach Boys's Pet Sounds album. "Silence and I" starts out smooth at the piano, adds vocals and strings. Slowly the song structure gains grandiose heights, then abruptly shifts tempo the likes you'd find in a Riverdance musical, then switches to cinematic French horns which sound absolutely Romanesque and riveting in realism.

I won't elaborate regarding the sound of the rest of the album beyond saying it is one of the most uniform pop/rock recording and mastering jobs I have ever heard, with the lone exception of side C's "You're Gonna Get Your Fingers Burned", which, unfortunately, was highly compressed on the master, making it too loud and a touch fatiguing compared to the other tracks. Because of this, my only minor criticism is that MoFi did not lower the average level on this one to subjectively match the loudness level of the other tracks that are much more dynamic, to avoid my having to readjust the volume before and after the song plays.

“And I don't need to see anymore to know that...”

Musically, it doesn't seem to integrate well either, as if somebody suggested, "guys, we need a commercial guitar-driven pop-rock song in a hurry"—all of which explains my slight downgrade from a "perfect 10" in the rating section at the top of this article. I tried to imagine what a "One-Step" version could improve on, and the only thing that came to mind was to maybe have had a sliver more definition in the deepest bass, and even that difference could backfire given the delicate balance MoFi achieved here. So, MoFi, don’t even dare going down that route, and instead set your sights on Pyramid for future Parsons releases.

Alan Parsons – keyboards,

Fairlight programming, vocals

Andrew Powell – orchestral arrangement, conductor, and piano

Eric Woolfson – main vocal, keyboards (track 2, 5, 12 & 14)

Stuart Elliott – drums, percussion

David Paton – bass, lead vocal (track 3)

Ian Bainrson – acoustic & electric guitars

Mel Collins – saxophone

Chris Rainbow – main vocal (track 4)

Lenny Zakatek – main vocal (track 6 & 9)

Elmer Gantry – main vocal (track 7)

1. The truth will set you free.

2. Transparency is key.

3. DSD is subjectively transparent and does not impart a digital trace or aftertaste.

4. When sourced from analog, the use of a DSD file has the important benefit of preserving precious, historic, fragile magnetic tape from further degradation or, heaven forbid, serious damage from running the tape multiple times. It opens the remastering industry to a larger portfolio of music genres and the vaults of major labels who may object to lending their master tapes. In addition, it liberates the mastering engineer and label to experiment to the nth degree using the best EQ and cutting practices, without pressure or time constraints, to reach that pinnacle of sound reproduction we all yearn for.

5. In all manufacturing chains, everything is important, but in the realm of remastering an album and the final sonic product, the inclusion of DSD is way, way down the list of subjective sound alteration, and is negligible at most. By far, the most important factors are the sourced tape's sound and condition, its transfer, the mastering engineer's experience and sonic choices, the equipment (reel-to-reel tape decks, EQs, limiters, cutting lathes, etc.). There’s also the plating, fathers, mothers, stampers, and pressing plant. All take precedence over "is it truly AAA", or "could it be AADSDA", or whatever initialism one relies on when buying a record. I rely on my ears and they tell me this Eye in the Sky is a sky-high homerun!

Colin Blunstone – main vocal (track 10)

The English Chorale – choir vocals

Bob Howes – chorus master

Additional credits:

Produced by Alan Parsons Executive-producer – Eric Woolfson

Recorded 1981-1982 at Abbey Road Studios, London, UK

Engineered by Alan Parsons assisted by engineer Tony Richards Coordinator and Mastering consultant Chris Blair

Remastered and lacquer cut by Krieg Wunderlich, assisted by Rob LoVerde at Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab in Sebastopol, CA

Plated and Pressed by RTI, CA, USA

Art Direction by Roland Young

Sleeve Artwork by APB, Colin Chambers, and Hipgnosi

Photography by Keith W. Lehman

lire la version française ici

So, what have we learned here, fellow music lovers, vinyl collectors, and audiophiles?

I love meeting the top designers at an audiophilecatering audio company because they're always so passionate about what they do. Why else would they be involved in perfectionist audio, if not to fulfill a burning nerdy-esque desire to create an audio product people will hopefully love?

Dominique Poupart, Product Manager at MOON by Simaudio, is one of those passionate guys. I saw it as soon as he greeted me at the front door of MOON's facilities about a half hour drive from where I live. He glows with youthful exuberance and self-confidence. Talk about audio with him and you can see that flicker of intellectual curiosity in his eyes that tells you that his work with audio is never done—can never be done—and that he wouldn't have it any other way. His is a lifelong sacred commitment to advancing the audio arts.

I couldn't have asked for a better tour guide than Dominique to visit MOON’s facilities. He’s been with the company for 22 years, 15 of which he spent in the R&D department. He now oversees that department and its team of eight engineers / designers, who carry out his multi-faceted vision.

He's also humble in the way that a lot of successful designers I've met are. He readily admits that there's more than one way to skin a cat in electronics design, and that his vision, as much as he believes in it and is

committed to it, may not be for everyone. There are different (circuit) paths, he conceded, that can lead to audio truth.

There's no denying, however, that his vision is working. Since its inception as Sima in 1980, MOON has never been more vibrantly successful as it is today. The company's product line includes 26 different models sold in 45 countries, where exports are about evenly split between North America, Europe, and Asia.

I agreed in large part to do this factory tour because I've always liked the sound of MOON products throughout the years, including, most recently, the company's ACE all-in-one player that I featured in “Best audio systems for $10,000, #4”. Simply put, the ACE produced a level of sound quality—chunky, rich, clear, refined—that I didn't expect from an all-in-one product in the ACE’s price range.

The tour started with a literal spring in Dominique's step as he led me down the hallway to a cluster of corporate offices, where I met a few of the workers, some of whom, I quickly learned, played instruments. In another sign that chez MOON it’s not just about audio, but music, I later discovered that there was a long, narrow stage on the lower level, with a set of drums, a mike, and a piano, all set up to be played.

We then proceeded to another corridor, this one made of ancient stone rather than drywall, inside which stood three vertical glass displays exhibiting significant Moon products throughout the company's decadeslong history. That this small museum faced a window overlooking the company's service department was no fluke.

As per Dominique: "It's to show that we still offer service on every single model we've ever built."

At the end of the corridor, we entered into the most bustling part of the factory, a clean, well-lit area with workers at desks and endless rows of towering steel shelves filled with parts. Aside from the job of winding its transformers, which is outsourced to a local company according to Dominique's specs, MOON assembles all its electronic products in-house, most by hand, and, some, such as the circuit boards, with the help of robotic arms, an industrial steam-based oven, and a liquid metal soldering machine.

MOON has two robotic arms assigned to assembling its circuit boards, each handling a different aspect of the process. In the case of the first machine, the arm applies soldering paste to spots on the board designed to receive a surface-mount electronic component, such as a resistor or transistor. Electronic components— of which the company has 6000 different parts in inventory—are either surface mounted, i.e. soldered to the surface of the board, or through-hole mounted, i.e. whose leads go through the board and are soldered to the board’s underside.

Dominique said the boards used by MOON are hybrid, in that they use both surface-mount and through-hole components. However, given a choice, Dominique prefers to go the surface-mount route for its shorter signal path and faster and more precise application. The through-hole method is best suited for bigger components, such as some of their capacitors, that need to be more rigidly affixed to the board.

The second robotic arm is a pick and place machine equipped with reels—imagine movie reels—of strips overlaid with electronic components that are fed to the arm, which takes those parts and places and orients them inside the dabs of soldering paste on the board’s surface. After this, the boards are inserted into the industrial oven to help “bake in” the components into the soldering paste.

It's to show that we still offer service on every single model we've ever built.

Through-hole components are then installed by hand into the board, after which the board is placed on a conveyor that slides into a “selective soldering” unit where a small fountain of liquid metal is precisely controlled to solder the pins to the board for a specific time for each pin. Et voilà!

There’s something satisfying and reassuring in watching a mechanical arm glide with brisk purpose then stop on a dime, doing what it was programmed to do with seemingly perfect timing and precision. That doesn't preclude, however, testing by humans. Every completed board is subsequently verified and tested to make sure it works exactly right.

Walking through the rows of parts for the company's various products, and the products under various stages of being built, I was struck by how elegant and clean everything looked. I was also taken by how neatly packed the insides of some of the company's most luxurious and complexly-designed products were. Sexy indeed!

I asked Dominique which were MOON's biggest selling products. "The 340i integrated amp”, he replied.

The company is also known for its digital products, built around the company's MIND (Moon Intelligent Network Device") technology, now in its second generation, that allows not only hi-res streaming but intelligent control of a whole MOON chain. The second generation MIND platform, launched in 2018, is retrofittable on all Gen. 1 products.

The company also does all of its own chassis work in-house, from machining to screen printing model numbers on faceplates. Final assembly of all MOON products is done by hand, prior to which every piece of gear is people-tested—for voltages, distortion, noise. Once a product is given the green light, it is then burned in using the company's own dummy loads— look-wise, think cheat plugs—that simulate a speaker load. As Dominique described it, "The load appears to the amplifier as a loudspeaker playing very loudly." Most products are burned in for one night, but some, such as phono stages, which handle tiny amounts of current, can be burned in for a week. Still, Dominique recommends that the consumer burn in their new gear for several more hours to achieve optimal performance.

MOON also does all of its own chassis work in-house, from machining to screen printing model numbers on faceplates.

Dominique then took me to the lower level where I spotted the aforementioned instruments, along with several different brands of speakers—Magnepans, Rockports, Audio Physics, as well as the company's own new Voice 22 standmounts. MOON uses various speakers, Dominique said, to evaluate the sound of its equipment.

That evaluation happens mainly in the last place I visited—the company's official listening room, a lushlooking environment tastefully bedecked in carpet, a faux-stone wall, room treatments, and a comfy listening chair. Across from that chair was a spread of matching MOON products—a 780D streaming DAC

coupled to an external 820S power supply, a 850P preamplifier, and a pair of 888 mono amps. They were flanked by a pair of Dynaudio Confidence 60 speakers. Nordost cabling cabled everything together.

The sound was sublime—rich, refined, luxurious. It was a fitting and memorable end to my voyage to (the) MOON.

Merci, Dominique!

Merci, Dominique!

Written By Robert Schryer

Written By Robert Schryer

Founder of Quebec's fabled Le Studio music studio and recipient of the Order of Canada and an honorary doctorate from Laval University, André Perry has worked with a who's who of musical icons: John Lennon, Rush, Cat Stevens, The Police, the Bee Gees, Keith Richards, Roberta Flack, David Bowie, and the list goes on. More recently, he is co-founder, with sound engineer extraordinaire René Laflamme, of Fidelio technologies Inc., whose 2xHD recordings are known across the world for their combination of musical excellence and sound quality.

It all started humbly. Hailing from a modest background, André left home at age 14, equipped only with a conviction. As he told me in our phone interview*, "I knew exactly what I wanted to do and there was no way anyone could stop me.” Exactly what he wanted to do was music. With that as his North Star, André started working as a busboy in a nightclub to be around bands and, more specifically, observe the drummers. At 17, he formed his own band in which he drummed and sang.

Fast forward through his turns as an in-demand studio session player, a jazz band leader, and founder of two Montreal-area studio facilities that served local talent, and we arrive in 1974. It’s the year André built Le Studio, a mythical music studio that was ground zero for so much of the great music released in the 70s and early 80s. Today, Le Studio stands gutted and abandoned, a relic of the past—a sad irony when we consider how cutting-edge it used to be.

For one, it was the only studio in North America to use the Solid State Logic Mastersystem console, considered, still today, one of the world's finest consoles. Only one other existed at the time, at London’s Abbey Road Studios. Le Studio also introduced the digital recorder, first used on The Police's Synchronicity album.

Perhaps most innovatively, Le Studio wasn't located in any urban area. Far from it—literally. It was tucked in the Laurentian mountains of Morin Heights, deep in the woods, about 65km from Montreal—far from the noisy bluster of city life and the mechanics of business. It was in this cutting edge compound entrenched in nature that some of the world’s most famous artists and producers would embed themselves, sometimes for months at a time, to create the next big record, and many of them did just that. The 100 or so albums recorded at Le Studio have generated combined sales of over 330 million copies, and those are just the legal ones.

However, being isolated in the woods isn’t everything. "It's not because it looks beautiful outside that it's going to bring the hits," André tells me. "Music comes from inside the artists. From the soul. But our place had a vibe. We had a few groups that came and walked inside the hallway and saw these Platinum records on the walls and thought the magic was going to rub off on them. People had a tendency to think that because Le Studio was chic, comfortable, and had a great chef, that was the trick to success. It wasn't that. The artists worked very hard. They would come to the studio around noon and work until 2am. There was big money involved. We had acts that paid for 6 months. We had to turn down all kinds of people, including Elton John, because we had three groups booked for a year and a half.

"People felt good at our studio, but that didn't necessarily mean they were going to come out with a great record, just that the conditions were good. Le Studio was first to make use of plenty of glass which was considered taboo in acoustics at the time. We had large windows between the control room and studio, which created a new intimacy between the engineer, producer, and the musicians. We had wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling windows looking out on to

nature and a lake. There were curtains but they were only drawn once. This area in the studio became the ‘live’ part of the room and was sometimes used for drums—such as in the case of Rush—and for the string section for David Bowie.

"We were also one of the first studios to draw artists from around the world, the reason being that we were not associated with a particular sound or culture. Studios from Muscle Shoals, Nashville, L.A., N.Y., Chicago, London, etc. were mainly sought out for their particular sound. Also, our staff came from everywhere. It was like the United Nations, with engineers from the U.K., Canada, L.A., N.Y., which allowed us to blend into various cultures.

“We didn't have a sound, we had all the sounds. If you listen to the 100 albums that were recorded there, you'll find that they all sound different. The Bee Gees have a Miami sound, Rush has another sound, so does Wilson Pickett, and Chicago. That's because I always looked at the studio equipment not as equipment, but as an instrument. We would tune the studio to suit the artist. The Bee Gees did the overdubs at Le Studio, then wanted to go to Miami to do the mix so they could get the Miami sound. So, during the night, we retuned the whole studio—all the equipment, the echo chambers—to give the Bee Gees the Miami sound. We mixed one track at 7 in the morning. When the group showed up later, we played it for them and they said, 'F--k that! We're finishing the album here.

"We made the studio an international head space recording facility. We were avant-garde. And it's hard today to find that same recipe."

I ask André what his relationship was like with the artists. "Like I said, most of the studios were owned by major labels, which made the relationship between the artists and the studio more commercial," André says. "But I was one of the guys. I was a musician. I was an engineer. I was a producer. When they came to André's place, the rapport that they had with me wasn't like with the guy who owns a studio and sells studio time by the hour. Cat Stevens came and did his first record with us, got to know my wife and me, and he wrote a song for us, "Two Fine People". Rush did eight albums with us. So when they came, it was family. It was André's place. It wasn't a commercial place. And the artists owned it while they were there. So, of course you can't compare it to a standard type studio in a big city."

Did he find the artists, or did they find him? "There was no need to find them. Let me throw a number out. It's not precise but it'll give you an idea of the scope. At the time, the international recording community was about 2000 people who knew each other. That included management, record companies, and artists. Whether you liked it or not, this was a private club. So, in our case, it started with Cat Stevens who had just broken up with his girlfriend and was looking to isolate himself for his next project. But he didn't like working in city studios. He heard that we had a studio in the middle of the woods, so he gave me a call and said he wanted to try our studio for four days. He stayed four months and recorded three albums.

"After Cat Stevens, the word went out and, luckily, the artists that followed brought us the quality content and the hits. Before we knew it we had the Bee Gees, Brian Adams, Rush, Chicago, The Police, Asia, etc. But you have to deliver.

“We were always taking chances, being motivated to be the first at anything. Unlike now, at that time you could strive for having the edge on the competition. I was hanging out

with the guys at Solid State Logic, helping to develop new features in their consoles. When you listen to recordings that were done in that period, a lot of the colors and effects were created by using the console in combination with the instrument. Musicians would often do their overdubs while sitting in the control room with the producer and engineer.”

Did he use compression—that common studio technique of shaving off the extended frequencies to make the music sound louder? "Of course we used compression because it was a pop market. The music had to pop out of your radio. But the amount of it depended on the record. Listen to Rush's Moving Pictures and you won't hear it because we used very little."

I ask what he thought of CD sound at first. "I haaated it. I haaated it. Because the first thing I missed was the second harmonic. And since I always had a sound system that was a bit warm, I missed that 2nd order harmonic."

Were any of the artists problematic? "Only one," says André. "But I solved that in a sweet way. I don't want to mention his name because it won't serve a purpose. But he made a big scene because he thought our staff had stolen his wallet. And a couple of days later, the dry cleaner called and told him they'd found his wallet in the pants he'd sent to them.

"So I went to an art gallery in Montreal and bought a beautiful art piece. I brought it to him and said, 'You know, we're just not like that. You're not in New York, not in L.A., and it’s not the way we are.' And he stayed and finished the album. But that was about it. There wasn't any trashing or breaking stuff."

"So no fist fights?" I ask.

"No, no."

"I heard the neighbour found a drum cymbal in the lake next to you. Any idea how it ended up there?"

“(laughs) That must have been Rush," André says. "I had an idea one day to take a picture of the drums on a floating dock. If the neighbour found a cymbal in the water, it probably fell in and nobody wanted to go get it (laughs)."

Did he ever offer creative suggestions to the bands? "It depends. Because at the level that those guys were at and the careers that they were having, it would have been very delicate to do that. Maybe I'd do it through the engineers, who reported to me on the sessions. Maybe if it came to the sound, or the recording process, I would put my 2¢ worth. But I would not intervene during the group's session. I don't see how that would have been justifiable."

"No, because the kind of producer I am is to work around the artists and make the magic happen. Yes, there were tense moments, but they were between themselves. Any time you're dealing with creativity, you're bound to get into disagreements. And then there were groups that were so smooth. Rush. Nazareth. They were darlings. Chicago, too, who were really two groups, because they had a horn section and a rhythm section and they would record separately. They both had their own sense of humour and would crack jokes. They were a lot of fun.”

Considering the company he kept, did André ever get star struck? “No, no, no. I’m a jazz guy, man. Jazz guys don’t get nervous. No, we were professionals. We showed up and did the work.“

“So no creative disagreements with any of the artists?" I ask.