Maia Cruz Palileo

Days Later, Down River

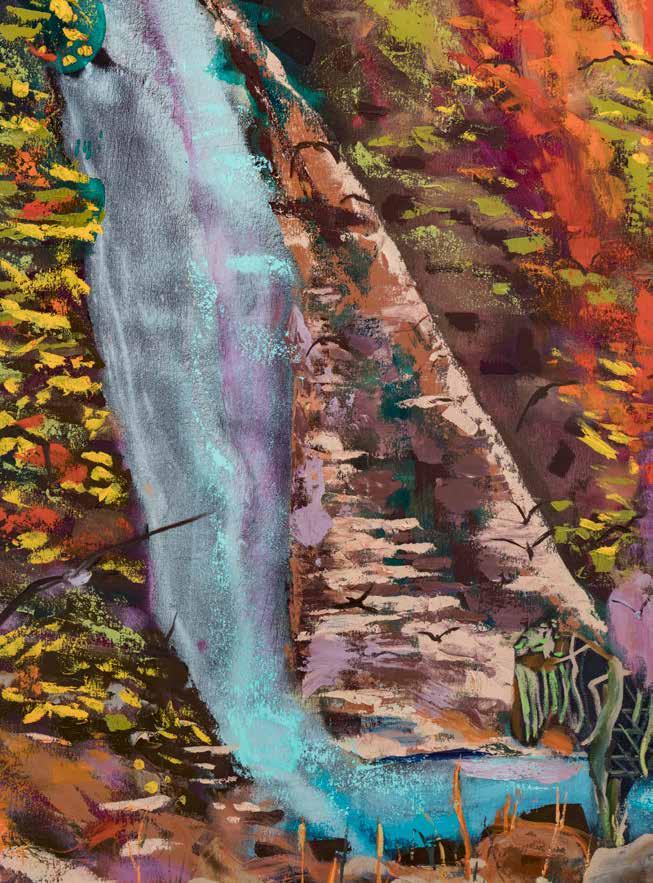

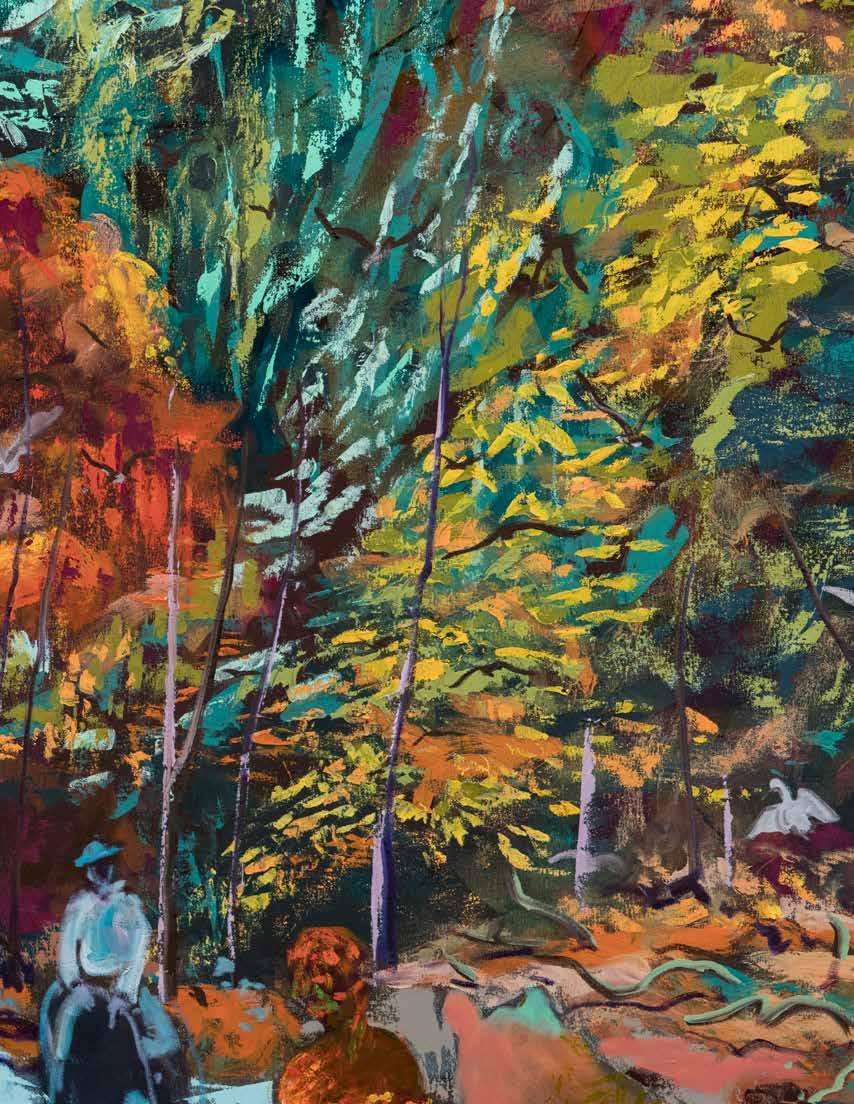

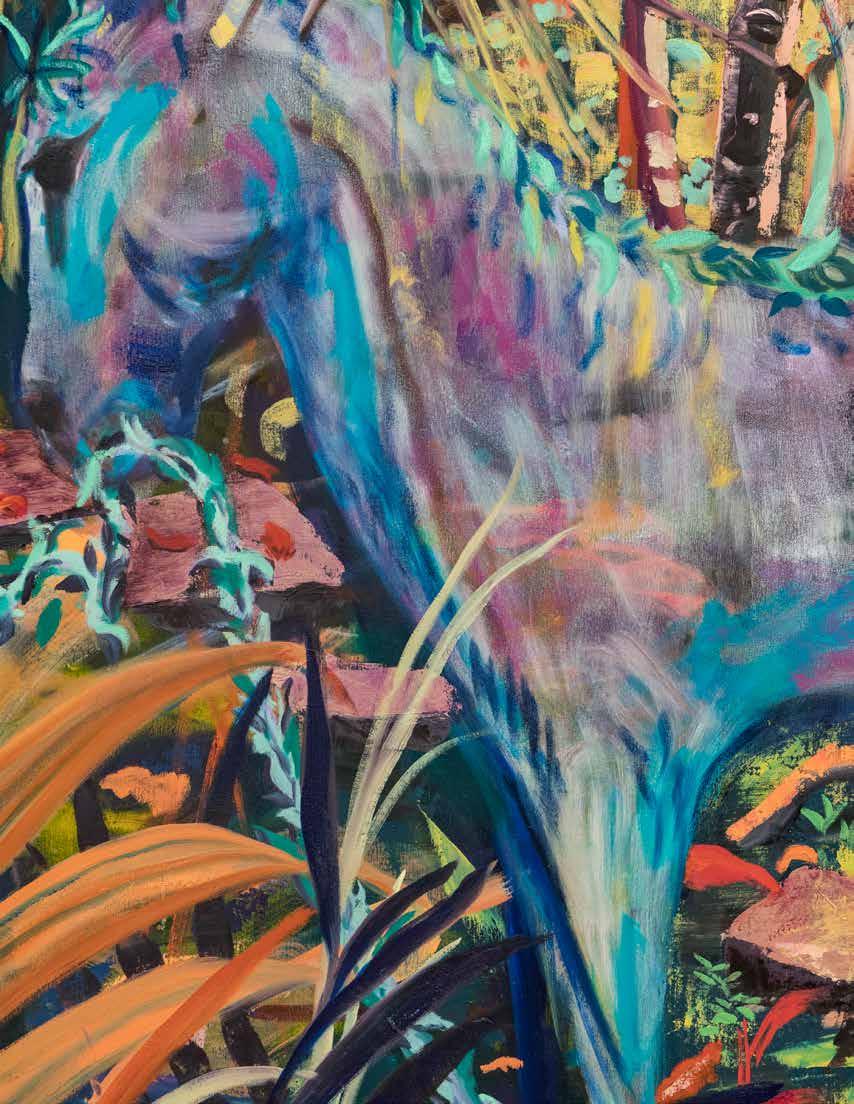

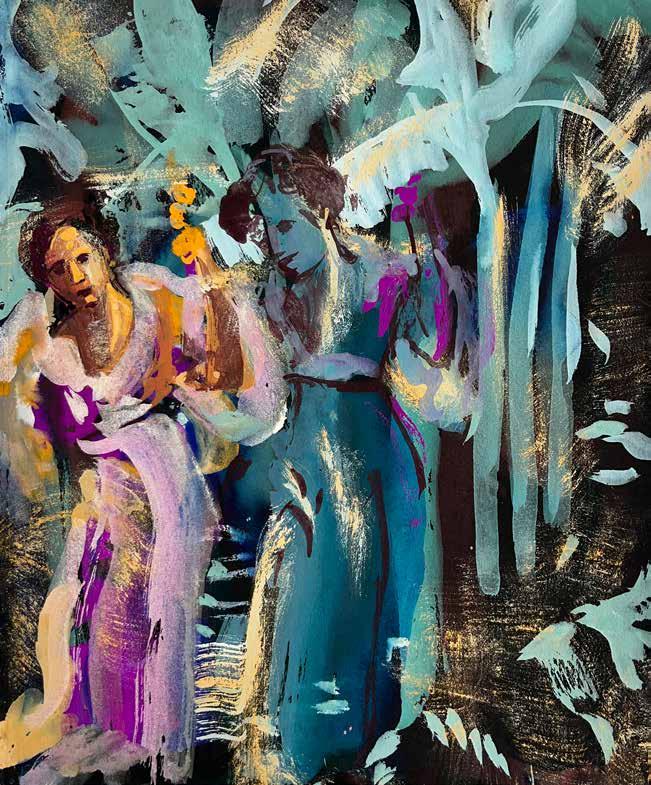

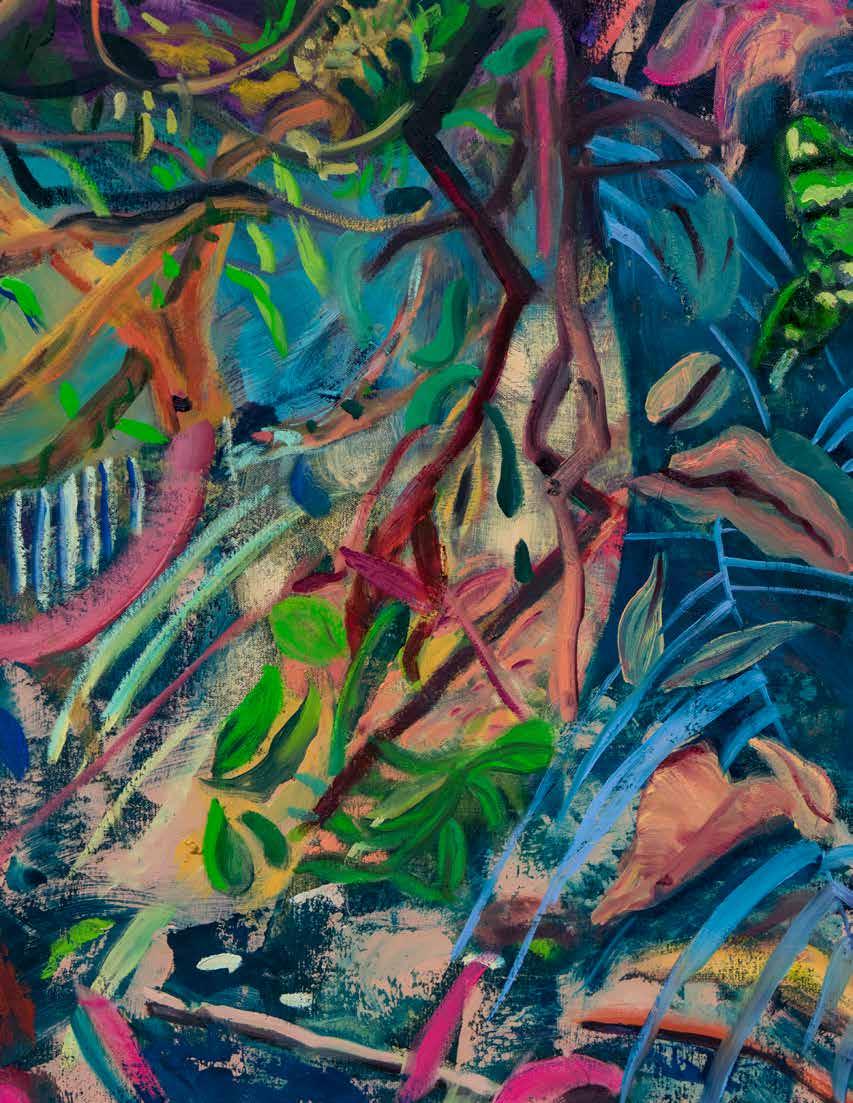

Front and back cover: Days Later, Down River, 2023 (detail)

Front and back cover: Days Later, Down River, 2023 (detail)

April 1 - May 26, 2023

Introduction by Alyssa Brubaker

Interview between Michael Darling and Ashlee Jacob

Designed by Megan Foy

Edited by Staci Boris

Photographed by Robert Chase Heishman

This catalogue was published on the occasion of Maia Cruz Palileo’s third solo exhibition at Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

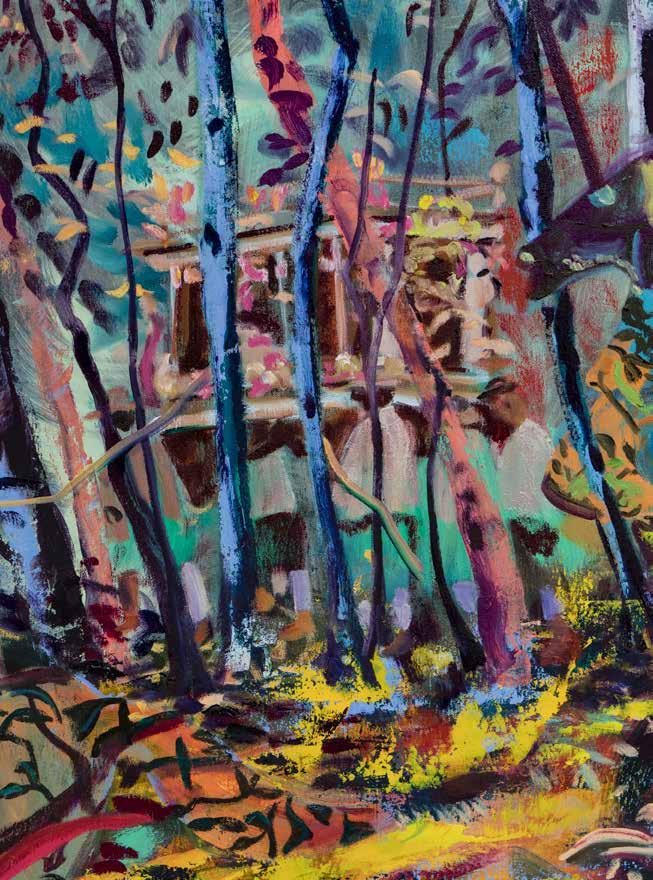

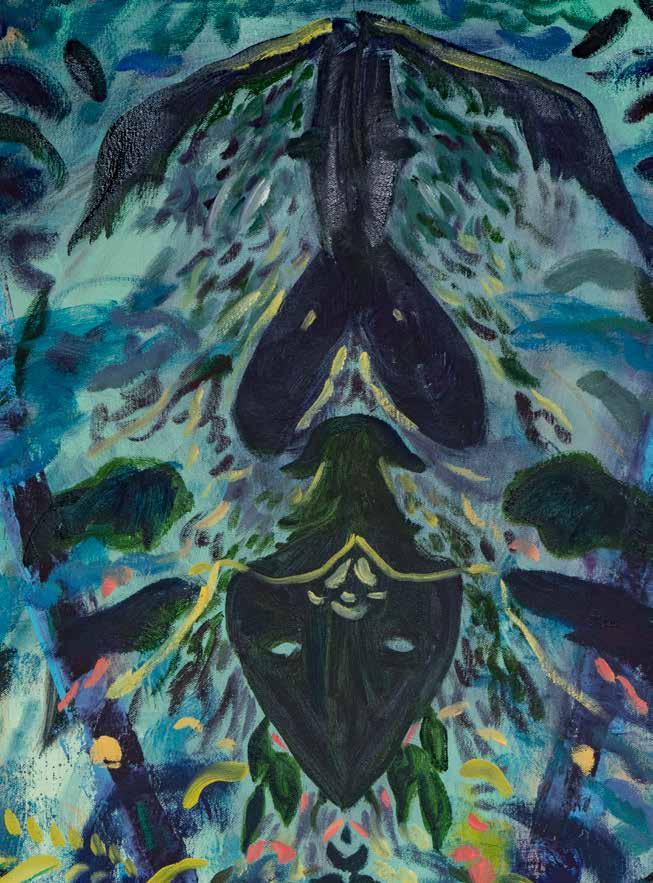

Maia Cruz Palileo is a multidisciplinary artist whose paintings, installations, sculptures, and drawings navigate themes of migration and the persistence of tacit knowledge in the face of assimilation. The works on view map an archival, geological, and spiritual topography of the Palileo family’s homeland—the Philippines—and are inspired by their recent residency at the University of Michigan, which houses one of the largest collections of Filipino artifacts in the United States. Building off their past research at the Newberry Library in Chicago and personal family archives, Palileo explores the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library’s photographic archive of Frank C. Gates—a professor of botany at the University of the Philippines (1912-1915)— and objects from the University’s Museum of Anthropological Archaeology’s Philippines collection. By incorporating research from these various archives, their paintings recontextualize stories, portraits, and images to resuscitate and remove from the exploitative gaze of the ethnographic image.

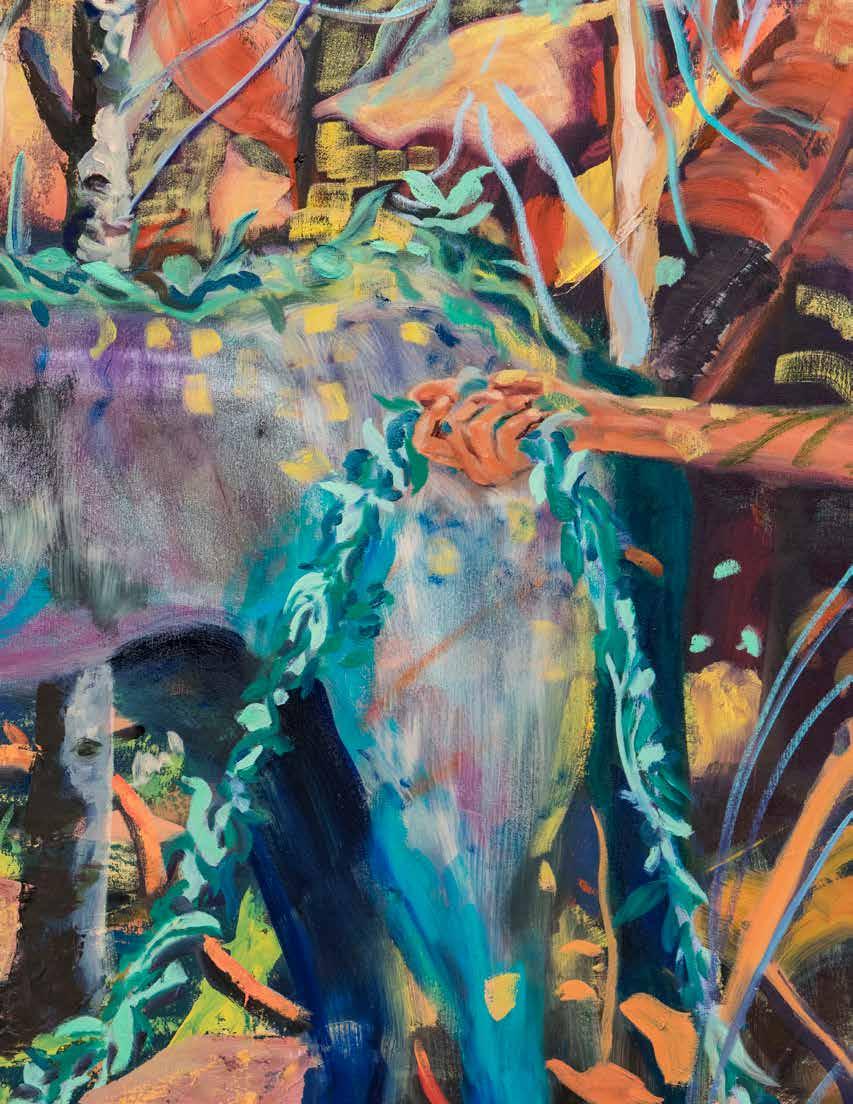

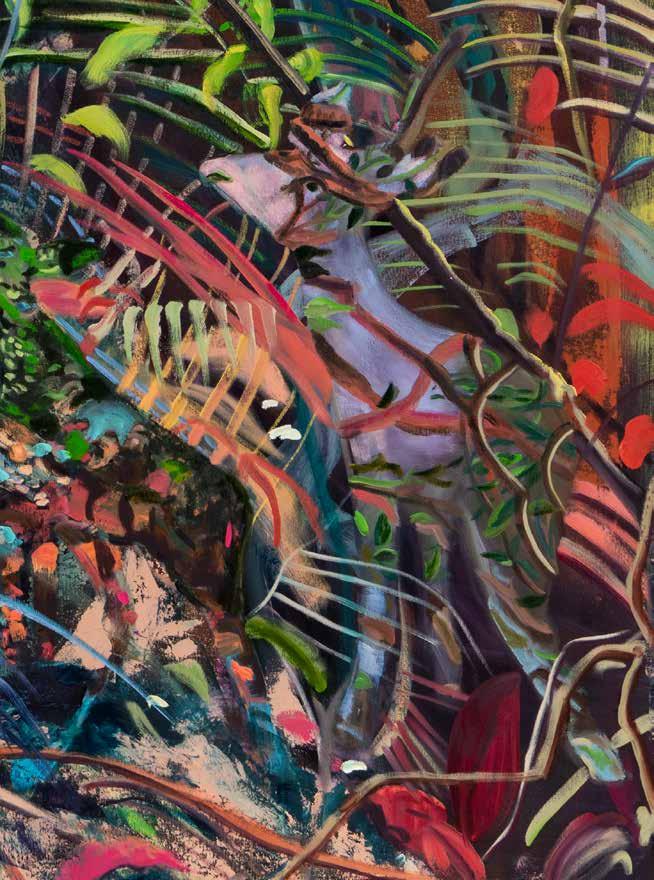

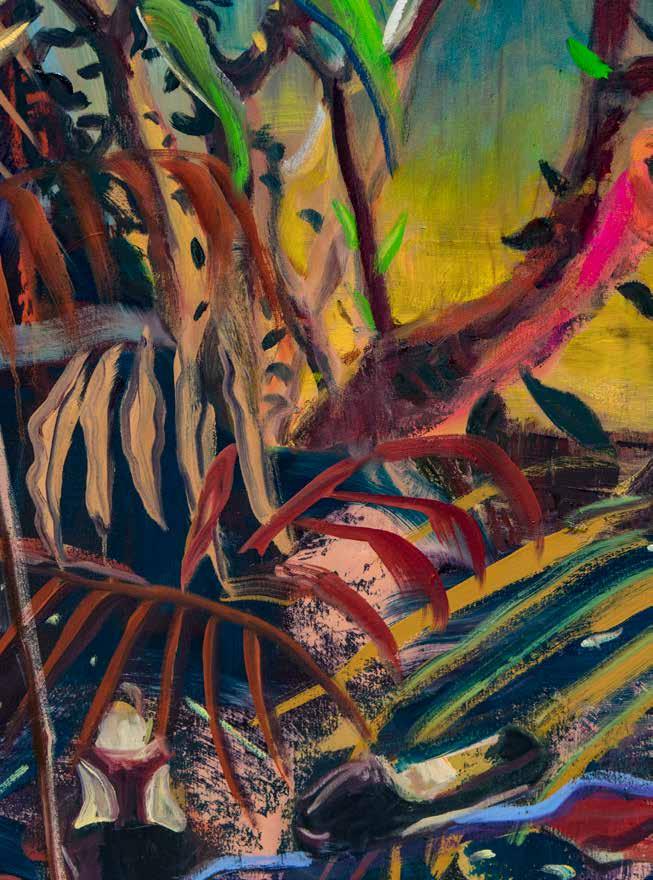

While at the archive, Palileo discovered photo albums of Mount Makiling and Mount Banahaw, dormant volcanoes in the Laguna region of the Philippines. Each mountain is a birthplace of legend; Mount Makiling is the home of the protective spirit Makiling, whose legend was written about by national hero José Rizal, and Banahaw is a sacred mountain for spiritual pilgrimage. These albums served as a portal into the artist’s familial relation to this land, making connections to artifacts in their personal collection of family photographs, blessed amulets, and oral histories. As with volcanoes, they propose history as a site where perceived extinction and dormancy can be uncovered to reveal activity and potential. Memorializing the legacy of invisible histories, dense layers of foliage reveal mysterious figures shrouded by overgrowth and shadow. Parasitic liana vines further complicate the canvas. Native to tropical forests, these rapidly expanding woody vines are increasingly shady, choking rainforest trees, and competing for resources. In contrast, when Rizal writes of the

mountain forests in Mariang Makiling he describes, “Tall trees with straight and mossy trunks, among whose branches the vines weave most beautiful laces embroidered with flowers.” Palileo renders the liana’s proliferation, interlacing the visible and invisible through layers of paint, echoing the selective means through which history is presented.

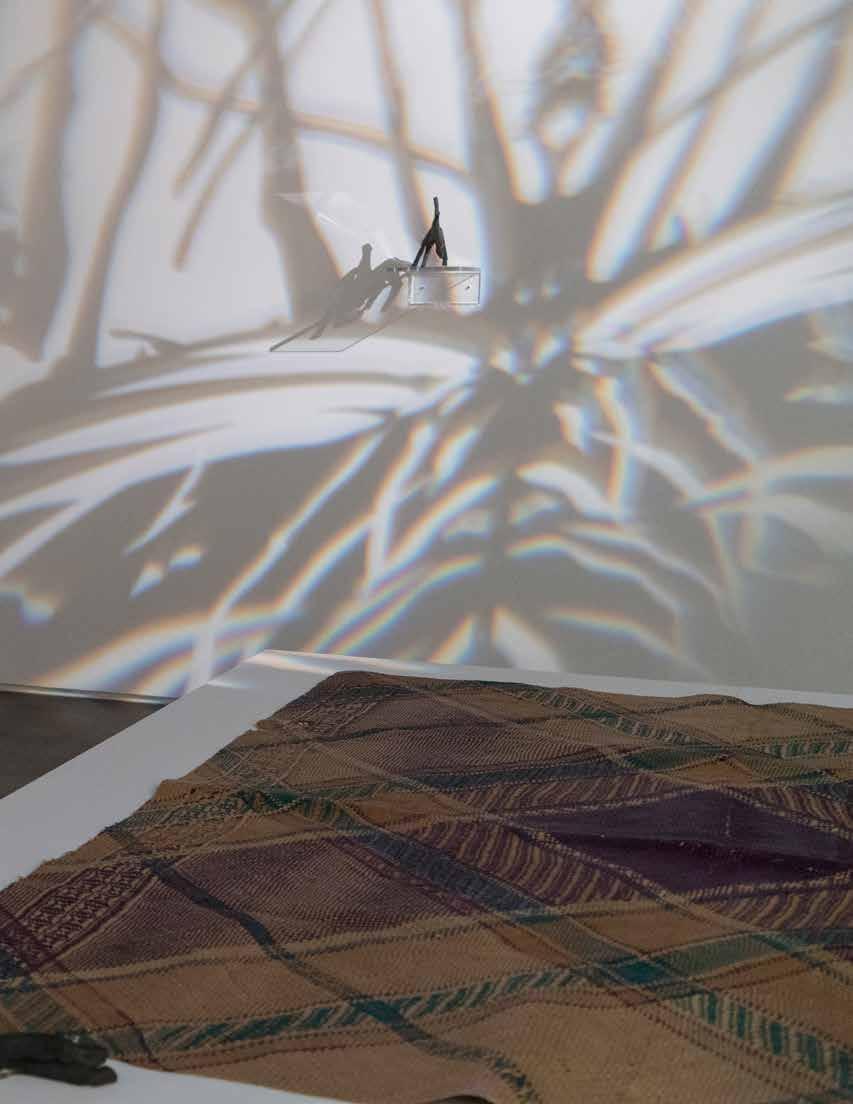

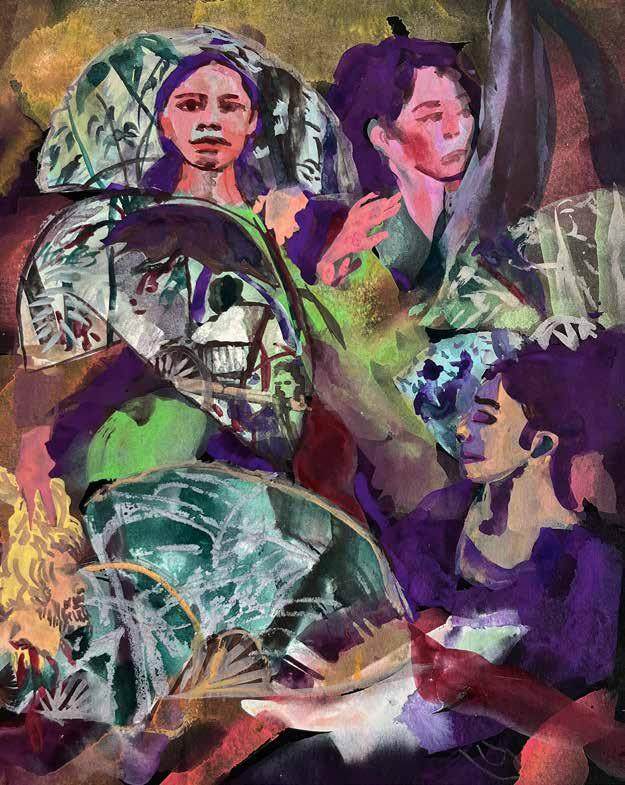

Translating these documents into a creative medium, Palileo cuts out archival images and reassembles them into panoramas where figures occupy mirrored and layered landscapes, offering new dimensions that intertwine ancestry, flora, and fauna. Transferring collaged black-and-white photographs into a vibrant palette, they pollinate a reimagined terrain in paint—an act of becoming where brush strokes render their homeland anew with self-possession and agency. At the center of the exhibition is a banig, a century-old woven mat loaned from the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology; an object used as a place for daily rest and gathering. Surrounded by projections of tree canopies and hand-sculpted clay figures, their foraged memories and histories honor the Filipino heritage that endured during the colonial era. Days Later, Down River uses installation, painting, projection, and ceramic to destabilize fixed narratives from the imperial occupation of the country, reframing artifacts into imagined sacred realms for their ancestors, and inviting viewers the chance to walk into Palileo’s imaginative spaces.

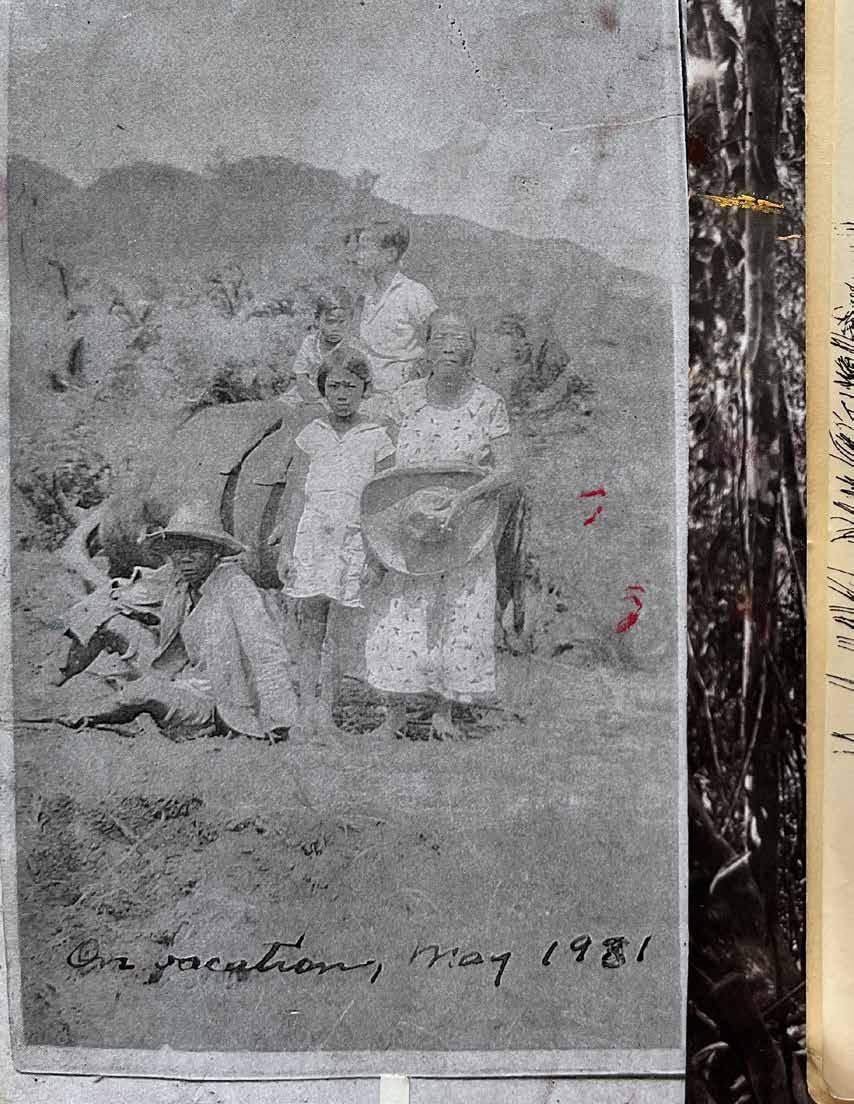

From Edna V. Palileo’s (the artist’s grandmother) family album

From Edna V. Palileo’s (the artist’s grandmother) family album

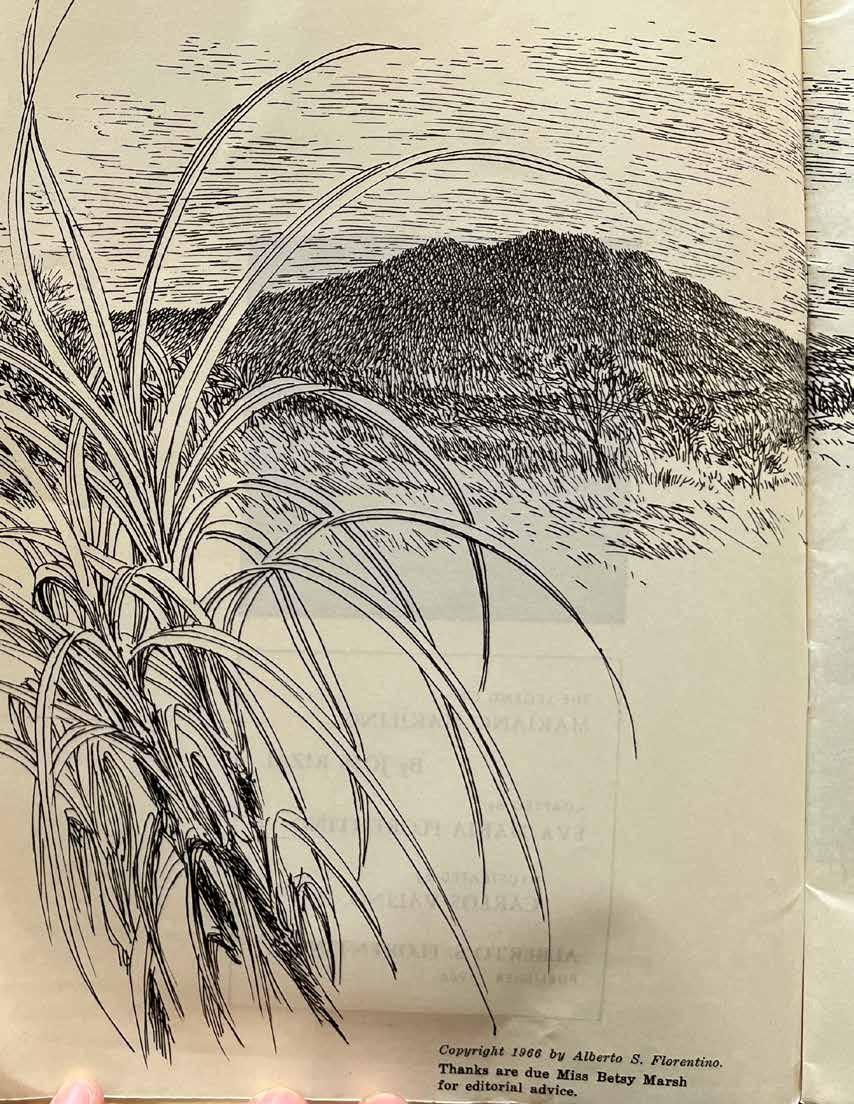

The Legend of Mariang Makiling by Jose Rizal, illustrated by Carlos Valino, Jr.

The Legend of Mariang Makiling by Jose Rizal, illustrated by Carlos Valino, Jr.

The banig is a traditional handwoven mat of the Philippines predominantly used as a sleeping mat or a floor mat. Depending on the region of the Philippines, the mat is made of buri (palm), pandanus or reed leaves. The leaves are dried, usually dyed, then cut into strips and woven into mats, which may be plain or intricate.1

The banig was the first object Maia encountered in UMMAA’s archives during their fellowship summer of 2022. The fellowship is a part of the project, ReConnect/ReCollect: Reparative Connections to Philippine Collections at the University of Michigan, a two year project that is funded by the Michigan Humanities Collaboratory exploring the colonial history between the United States and the Philippines.

The below excerpt is from Maia Cruz Palileo’s interview with Sophia Liu for Surging Tide Magazine published online April 2023.

Sophia Liu:

Thank you for understanding the need for representation in the arts, especially accurate representation that is not simplified and generalized from a Western gaze. Who or what spurred you to approach art as a way to recontextualize your history and defy the single narrative that white America has manufactured?

Maia Cruz Palileo

I appreciate being asked this question because 20 years ago, when I was making paintings of my aunties and my grandmas, this was not a question that was being asked. I know it was a conscious decision to paint people from my family, but to be honest, back then this conversation was not being had in my graduate school critique sessions. I needed to find something that I felt deeply connected to and what that ended up being, in the beginning and still today, were my familial connections and experiences of loss, death, grieving, and memory. Those themes are personal, and they’re also familial and historical. In examining my own family ties and my own longing to connect with departed family members, I was led to do a lot of research. I was going through the archives and I saw people who were photographed in these archives. They had this kind of knowing look in their eyes that I was searching for something that I could connect with. What I saw in the photographs and what I chose then to represent in my paintings was resilience, which went counter to the narrative that has been written about all these colonial photographs.

They didn’t describe the fierce look in someone’s eye; they were the opposite. It was interesting to see something that I saw in the pictures and then to read what was written about it because they were completely opposing. I took these figures and removed them from this context and put them into a new context, which I guess it’s similar to the banig, which I took out of the archive. But, on the other hand, the banig is torn and has creases and shows its wear and tear over the years. The archival images are similar. They still carry the residue of all the years they’ve been housed in the archives.

“What I saw in the photographs and what I chose then to represent in my paintings was resilience, which went counter to the narrative that has been written about all these colonial photographs.”

A conversation between Michael Darling and Ashlee Jacob

A conversation between Michael Darling and Ashlee Jacob

The following is a transcribed conversation between curators/collectors Michael Darling and Ashlee Jacob, which occurred in April 2023 at the dining table in their Chicago home. Darling and Jacob are early supporters of Palileo’s practice, having been first introduced to their work in 2019. Seated in their dining room next to one of Maia’s early paintings that was acquired from their first solo show, Darling and Jacob discuss their early adoration of Maia’s work and what it means to have a stake in an artist’s success.

Michael Darling: So as a prelude to talking about Maia Cruz Palileo’s work, maybe we should clarify how we approach buying art. I love being there at the beginning of an artist’s career, similar to how I love reading debut novels. There is a thrill to seeing new voices emerge, and if I’m lucky enough to be able to bring an artwork into the house to live with it, it feels like I’m witnessing history.

Ashlee Jacob: I have artist parents who would trade with their artist friends so I grew up in a house surrounded by art. For me it just feels natural to want to have art surrounding me. I guess I want to recreate that energy on my own aesthetic terms.

MD: When we walked in the door of Monique’s to see Maia’s work the first time, during the opening of their solo show in 2019, we reacted instinctively to it. It was beautiful but we could also sense its importance and we both bought paintings that night. I didn’t know what it was about, but I wanted to learn.

AJ: I was drawn to the magical realism of the compositions and Maia’s particular alchemy of light. I also think the exhibition title, “All the while I thought you had received this,” gave us a contextual clue; for me, it implied a state of in-betweenness or a protracted journey, and how these experiences were part of a post-colonialist narrative.

MD: I felt that more complicated reading of the work came later for me, after reading about Maia, seeing more works by them. Living with the works too made them unfold and reveal themselves over time.

AJ: There are multiple layers to my appreciation: I liked it, I bought it, but I was also challenged by it. I was attracted to the spatial ambiguity of the work. In our larger painting, The Parlor (2019), light and space are very complicated.

MD: We’ve put that painting near a window where light comes in sideways which not only mimics the way light comes in on the right side of the painting, but it also creates changing light conditions throughout the day. We are sitting at our dining table looking at it right now.

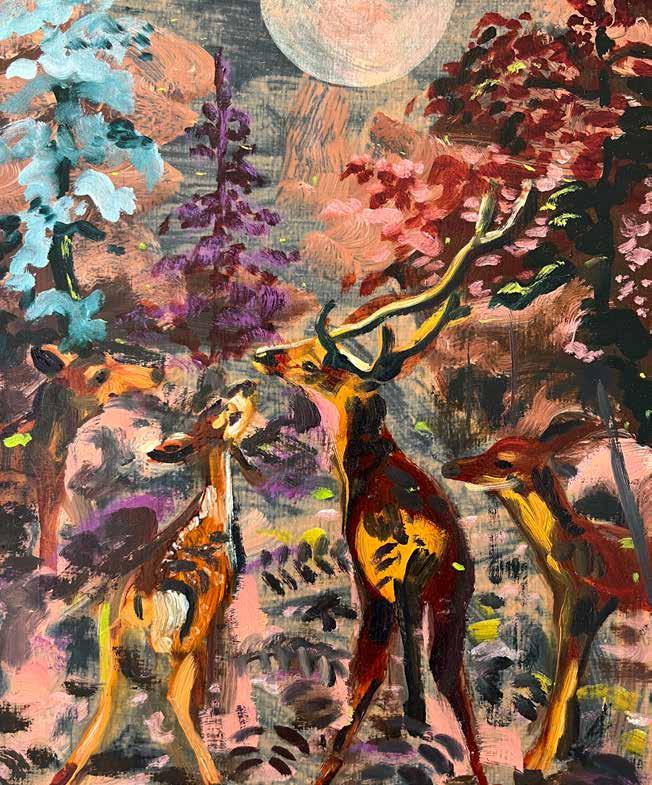

AJ: We saw the reference photo for the deer in the painting in the exhibition catalogue, Long Kwento—a baby deer as a pet being cared for by two people.1 But in

the painting the orientation of the deer is flipped—evidence of Maia’s use of cut outs and collages? We sometimes wondered if it was a dog, but the photo confirms where it came from. In the source image, I also noticed a tiled floor receding into the darkness which shows up in the painting as an interior. And what about the mysterious rope that stands on its own, like a coiled cobra? Probably also based on a detail from one of the archival photos they use?

MD: I was struck by the idea of “colonial haunting” in Justin de Leon’s essay in Long Kwento and this painting has that—a genteel white group sitting in a luxe interior, what looks a ghostly, perhaps Filipino personage appearing in the upper right, exerting itself on the interior.2 Not to mention the deer, perhaps a symbol of indigenous nature ready to reclaim this space? The ground plane of the floor is also disorientingly off-kilter which also gives the scene a sense of impermanence.

AJ: When I was young and staring at book covers long enough I would will myself to see things there—this painting does that for me too.

Maia Cruz Palileo, The Parlor, 2019 oil on canvas over panel, 48 x 33 in.

The Parlor, 2019 installed in the home of Michael Darling and Ashlee Jacob

Maia Cruz Palileo, The Parlor, 2019 oil on canvas over panel, 48 x 33 in.

The Parlor, 2019 installed in the home of Michael Darling and Ashlee Jacob

MD: Yes, it is impossible to exhaust this painting, it keeps on giving and giving. A hallmark of great art, no doubt. In fact, for me, Maia accomplishes that rare feat of technical mastery of their medium, sheer beauty that lures you in, and then really serious content that is both deeply personal and accessible. So many artists have one or another but rarely all three.

AJ: In that great Long Kwento, de Leon talks about silence as understood by the Lakota: silence is a place, a space to evolve and grow.3 That resonated with me. It also reminded me of something Julie Mehretu once said about the ambiguity of the blurred imagery she uses, that it creates the potential for futurity.4 I remember times when I would sit on my porch at night in Chicago and when I was silent and chill, I would start to pick up on so many different bird calls and communication going on above or below the flow of big city life. I find meditation difficult, but this idea of a generative silence seems like a way for me to tap into that, right?

MD: Yes, I love what happens when I achieve that stillness in meditation and what starts to emerge sensorially in that state.

AJ: In front of Maia’s new paintings, many of which are dense with foliage, I find myself getting lost and almost require quietness to penetrate them and appreciate them. You know that’s why I hate looking at art at openings! When my mom worked at the Terra Foundation when they still had gallery spaces, I was able to look at American landscape paintings when no one else was around and got to understand them in a way I never would have if it was during regular open hours with the general public.

MD: We attended a talk at the gallery with Maia and curator Kim Nguyen and we happened to be seated next to one of those big jungly paintings and were able to let it wash over us a bit. I sensed a really sophisticated mix of surface activity or foreground and then these tunnels of space that invite your eye to push deeper into the

painting. Maia said that is an aim of theirs in the talk, and I always thought that was an important tool for painters to use to ensure a long and complicated digestion of the picture, one that not as many artists these days actually use.

AJ: So in addition to all that beauty you are talking about, there is a distinct political aspect to the work. Let’s talk about the concept of “reparative work” that Maia and Kim have spoken about.5

MD: Yes, part of Maia’s practice involves a lot of deep research, going to libraries and archives to see pictures and documents about the Philippines, especially ones describing the colonial imprint on the country. Those photographs and other ephemera are incorporated into the paintings, essentially bringing back histories that may have been forgotten through the generations.

AJ: Or that material shores up stories they have heard from their family and grounds it in a larger, shared Filipino history. But they have said that research is emotionally draining too, so much of what they found was deeply disturbing and violent, they became self-aware of “what being in an archive does to a body.”6 Maia is basically putting their body and psyche on the line to bring these stories forward and I feel very humbled and fortunate to even be witness to that work. It makes me hyper aware of your and my privileged position as viewers of this labor.

MD: Wow, yes, totally. Along those lines, Maia also said something powerful about their artistic practice, that “embodiment is everything” and “how do I digest it, have it pass through my body.” 7 That kind of approach really makes me think differently about their practice—this isn’t someone just making pretty paintings, it’s a hardcore and super serious cultural undertaking.

AJ: Yes, Maia’s work reminds me that history is non-linear and that there are multiple stories compacted on top of each other. But whose story is told and which narrator is prioritized are crucial to keep in mind.

MD: You are so right, that really comes through in the work. Thank you for that insight!

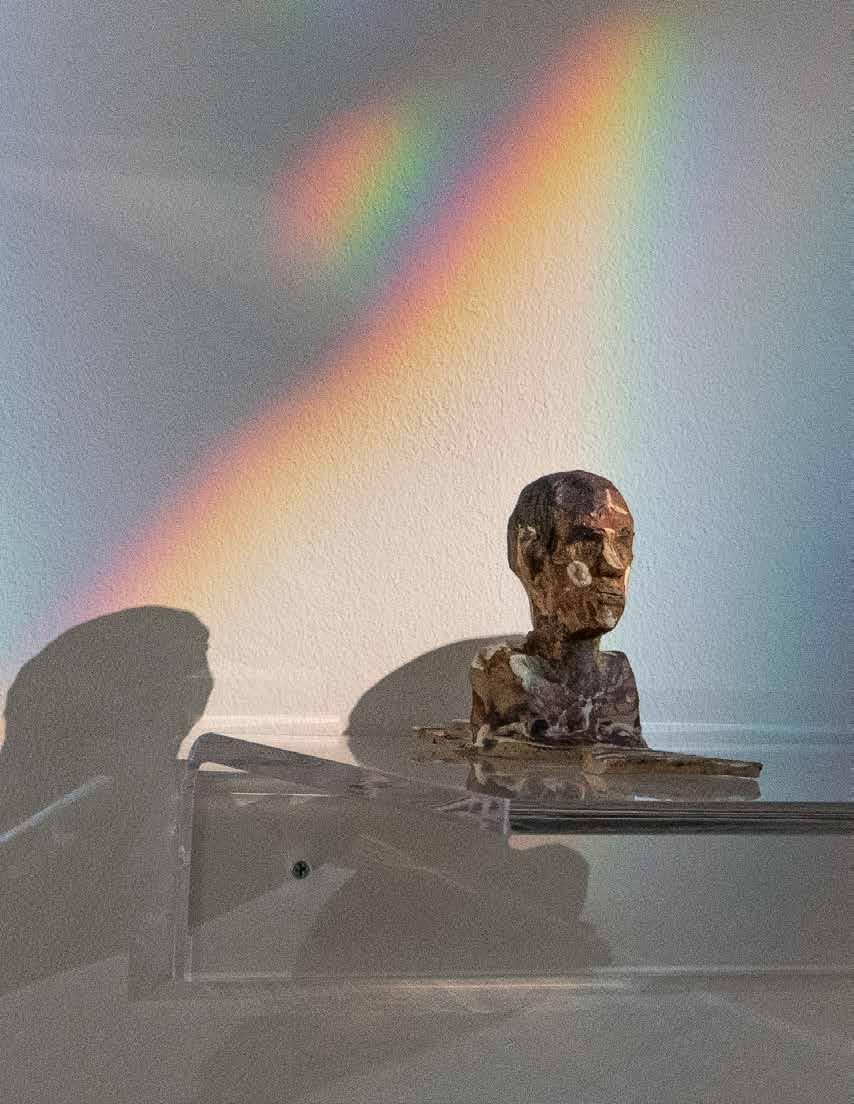

Horse & Rider, 2023

ceramic, oxide

8 x 11 x 3 in

20.3 x 27.9 x 7.6 cm

Ouroboro, 2023

ceramic, oxide

7 x 5 x 2 in

17.8 x 12.7 x 5.1 cm

Kapwa, 2023

ceramic, oxide

9 1/2 x 6 x 6 in 24.1 x 15.2 x 15.2 cm

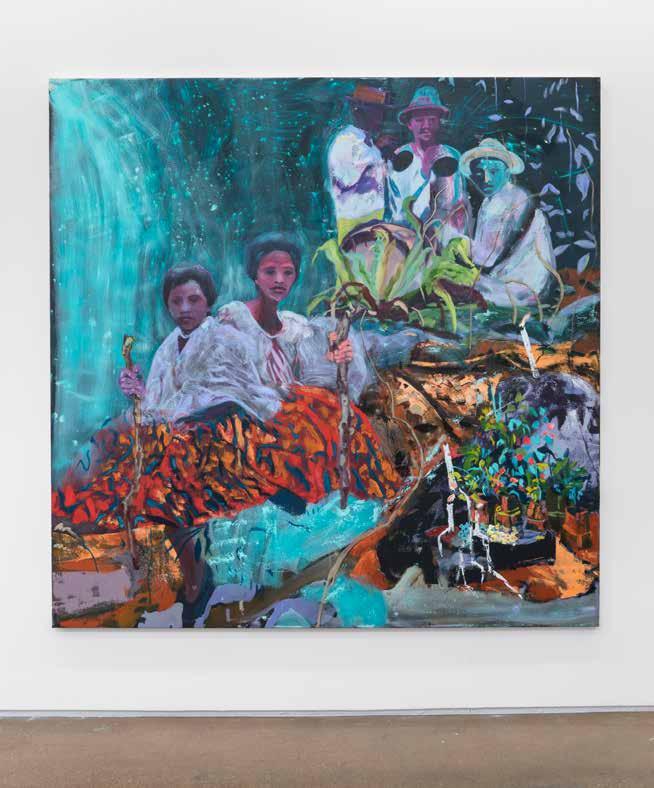

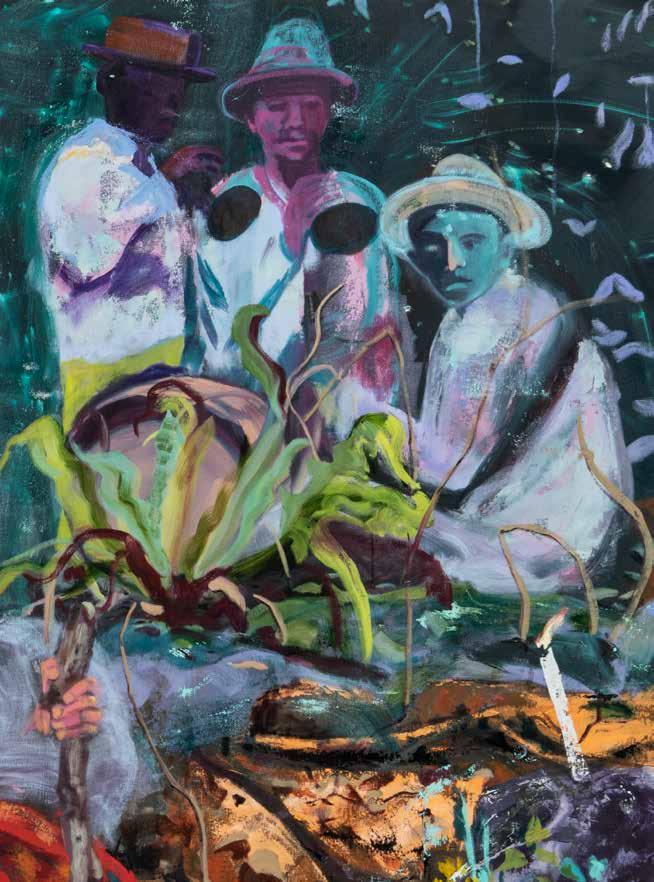

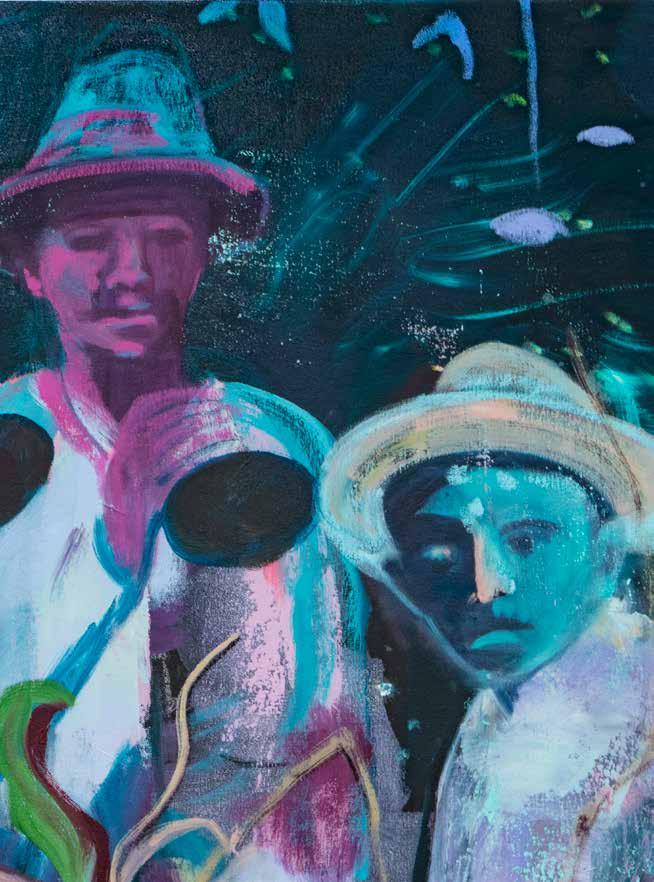

Days Later, Down River, 2023

flashe and oil on canvas

84 x 108 in

213.4 x 274.3 cm

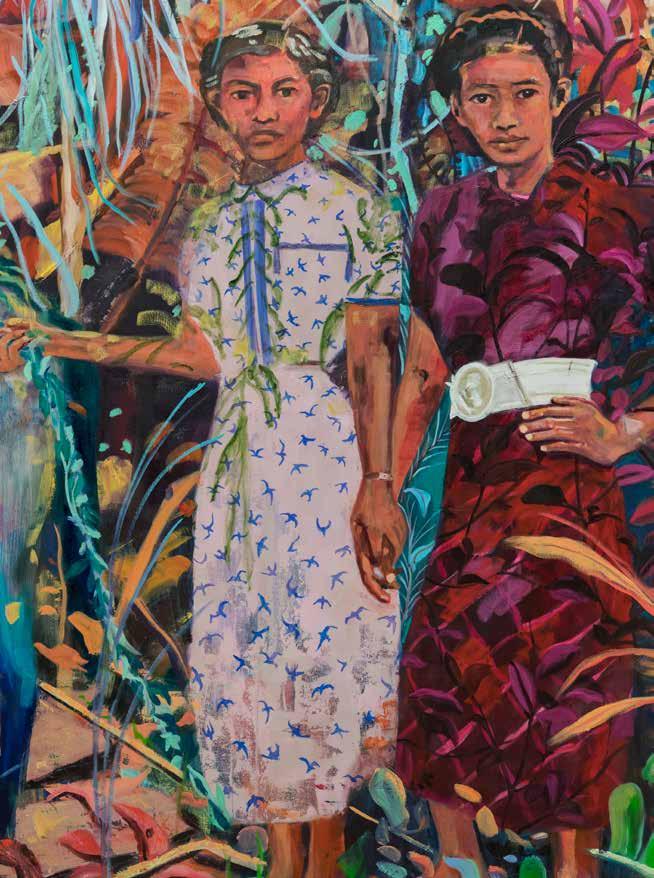

It Was Said They Could See Each Other’s Memories II, 2023 flashe and oil on canvas

84 x 84 in 213.4 x 213.4 cm

It Was Said They Could See Each Other’s Memories I, 2023 flashe and oil on canvas

84 x 84 in 213.4 x 213.4 cm

To Gather Together, 2023

flashe and oil on canvas

213.4 x 274.3 cm

After Wandering For Much Time, 2023

Maia Cruz Palileo (b.1979, Chicago, IL) received an MFA in sculpture from Brooklyn College, City University of New York, Brooklyn, NY (2008) and BA in Studio Art at Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, MA (2001). Palileo has had solo exhibitions at the Kimball Arts Center, Park City, UT (2022); the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, CA (2021); the Katzen Arts Center, Washington D.C. (2019); moniquemeloche, Chicago, IL (2019); Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, NY (2018); Taymour Grahne Gallery, New York, NY (2017); and Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space, New York, NY (2015). Palileo has been featured in recent group exhibitions at The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC (2023); National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C. (2022); Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA (2022); San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA (2022); Jeffrey Deitch Gallery, Los Angeles, CA (2022);

The Rubin Museum of Art, New York, NY (2018); and the Bureau of General Services Queer Division, New York, NY. Forthcoming exhibitions include a group exhibition at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, NE (2023).

Their work is in the collections of The San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA; The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC; The Speed Museum, Louisville, KY; and The Fredriksen Collection at the National Museum of Oslo, Norway. Palileo is a recipient of the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program Award, NY (2022); NYFA Painting Fellowship (2021); Jerome Foundation Travel and Study Program Grant (2017); Rema Hort Mann Foundation Emerging Artist Grant (2014); Astraea Visual Arts Fund Award (2009); Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant (2018); and Joan Mitchell Foundation MFA Award (2008). Palileo has participated in residencies at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Madison, ME; Lower East Side Print Shop, NY; Millay Colony, Austerlitz, New York; and the Joan Mitchell Center, New Orleans.

Michael Darling is Co-Founder and Chief Growth Officer at Museum Exchange, an art philanthropy start up. He was formerly Chief Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and also held curatorial positions at the Seattle Art Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. He holds both a PhD and MA in art and architectural history from UC Santa Barbara and a BA in art history from Stanford University.

Ashlee Jacob is a patron of the arts and other social-impact projects. She is the founder of Victoria Press, a publisher of bespoke art books. Collaborators have included Ellen Berkenblit, Richard Kern, Fortnight Institute, and Anton Kern Gallery. She holds a BA in art history from the University of Kansas.

Banig c. 1903-1905

woven mat

The Morse Philippine Collection University of Michigian Museum of Anthropological Archaeology

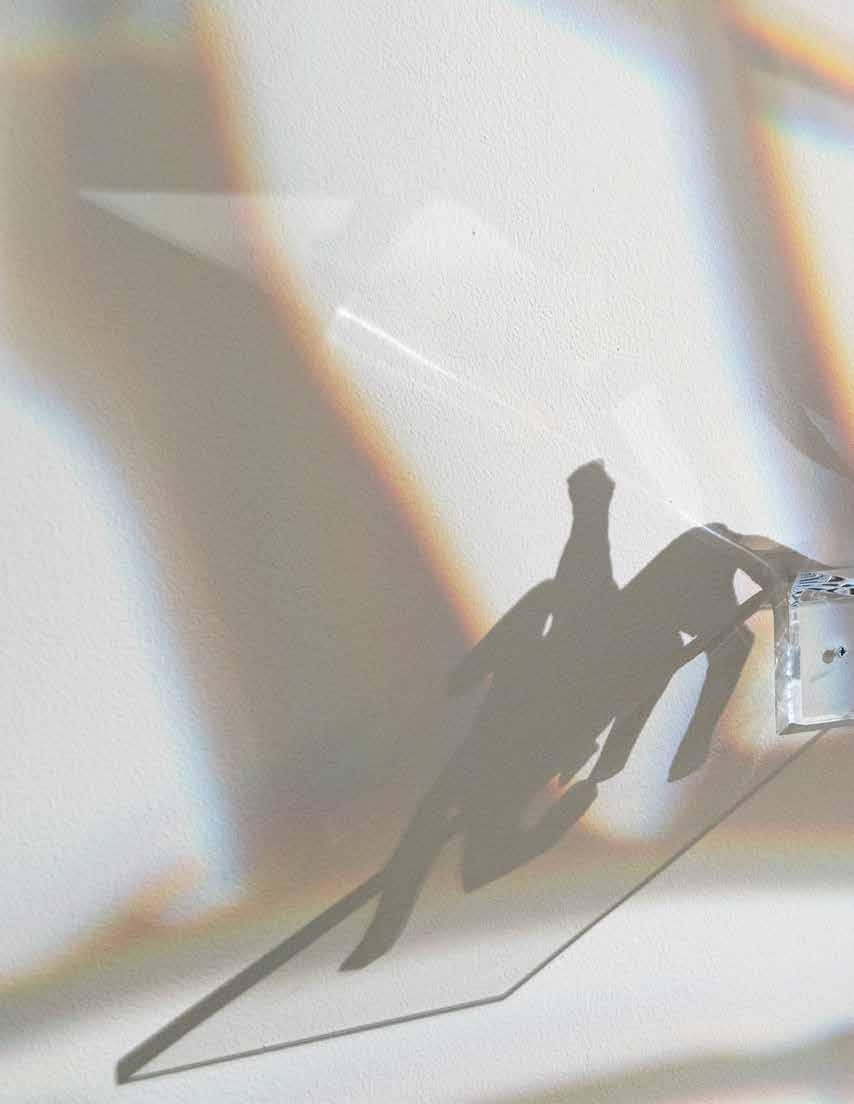

Diwata with Snake, 2023

ceramic, oxide

5 x 10 1/2 x 3 in

12.7 x 26.7 x 7.6 cm

Diwata with Striped Pants, 2023

ceramic, oxide

6 x 12 x 4 in

15.2 x 30.5 x 10.2 cm

Horse & Rider, 2023

ceramic, oxide

8 x 11 x 3 in

20.3 x 27.9 x 7.6 cm

Flores, 2023

ceramic, oxide

7 x 11 1/2 x 6 in

17.8 x 29.2 x 15.2 cm

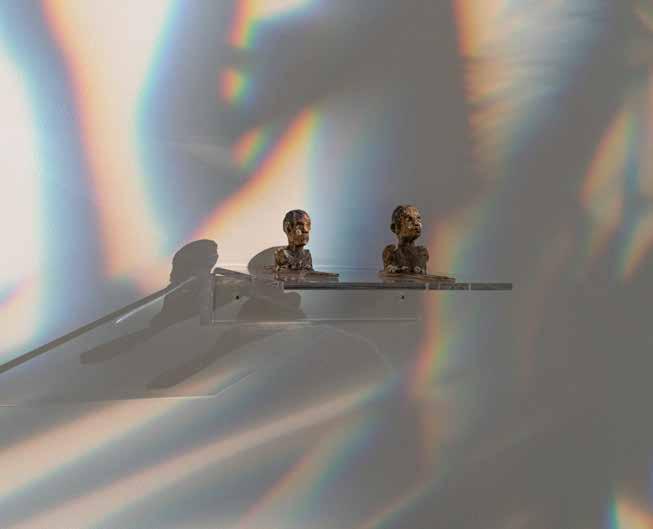

Swimmer I & II, 2023

ceramic, oxide

5 x 7 x 3 1/2 in

5 x 7 x 4 in

12.7 x 17.8 x 8.9 cm

Kapwa, 2023

ceramic, oxide

9 1/2 x 6 x 6 in

24.1 x 15.2 x 15.2 cm

Ouroboro, 2023

ceramic, oxide

7 x 5 x 2 in

17.8 x 12.7 x 5.1 cm

Rising Moon, 2022

oil on panel

16 x 12 in

40.6 x 30.5 cm

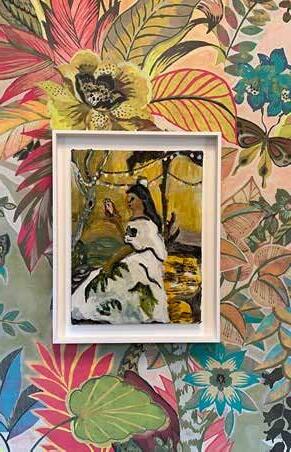

Veiled Dancer, 2022 gouache on paper

15 x 11 in 38.1 x 27.9 cm

19 1/2 x 19 5/8 in (framed)

Fire Dancer, 2022 gouache on paper

15 x 11 in 38.1 x 27.9 cm

19 1/2 x 19 5/8 in (framed)

Fan Dancers, 2022 gouache on paper

15 x 11 in 38.1 x 27.9 cm

19 1/2 x 19 5/8 in (framed)

Drummer, 2022 gouache on paper

15 x 11 in 38.1 x 27.9 cm

19 1/2 x 19 5/8 in (framed)

Coconut Field, 2022 gouache on paper

15 x 11 in 38.1 x 27.9 cm

19 1/2 x 19 5/8 in (framed)

Santiago de Galicia, 2022 gouache on paper

15 x 11 in 38.1 x 27.9 cm

19 1/2 x 19 5/8 in (framed)

Asos (dogs), 2022 gouache on paper

7 1/2 x 11 in 19.1 x 27.9 cm

12 x 15 5/8 in (framed)

Days Later, Down River, 2023 flashe and oil on canvas

84 x 108 in 213.4 x 274.3 cm

It Was Said They Could See Each Other’s Memories I, 2023

flashe and oil on canvas

84 x 84 in 213.4 x 213.4 cm

It Was Said They Could See Each Other’s Memories II, 2023

flashe and oil on canvas

84 x 84 in 213.4 x 213.4 cm

To Gather Together, 2023

flashe and oil on canvas

84 x 108 in 213.4 x 274.3 cm

The Slow Course of Water, 2023

flashe and oil on canvas

84 x 84 in 213.4 x 213.4 cm

The Sleeping Mountain, 2023 flash and oil on canvas

84 x 96 in 213.4 x 243.8 cm

After Wandering For Much Time, 2023

flashe and oil on canvas

84 x 96 in 213.4 x 243.8 cm

All artworks by Maia Cruz Palileo, unless otherwise noted

pp. 12–13, 14–15, 18–19, 20–21, 25, 28–31: Artist photo collages using reproductions of various photographic archives from the Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. Courtesy of the artist.

p. 16: Reproduction of photograph from Edna V. Palileo family album. Courtesy of the artist.

p. 17: Artist photograph of The Legend of Mariang Makiling by Jose Rizal, illustrated by Carlos Valino, Jr. Courtesy of the artist.

pp. 22–23: Banig, c. 1903-1905, from the Morse Philippine Collection, University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology. Accession #278. Photo: Robert Chase Heishman

pp. 29 right, 30: Collection of Michael Darling and Ashlee Jacob. Photo: Michael Darling and Ashlee Jacob

p. 142: Photo: Ligaiya Romero

p. 143 Photo: Michael Darling and Ashlee Jacob

Monique Meloche Gallery is located at 451 N Paulina Street, Chicago, IL 60622

For additional info, visit moniquemeloche.com or email info@moniquemeloche.com