Arvie Smith Crossing Clear Creek

Front cover: Crossing Clear Creek, 2024 (detail)

Back cover: Tell Mama All About It, 1991 (detail)

Arvie Smith Crossing Clear Creek

Monique Meloche Gallery

February 8 - March 22, 2025

Introduction by Alyssa Brubaker Essay by Dr. Kiara Hill Edited by Staci Boris

Photographed by Bob. Designed by Julia Marks

This catalogue was published on the occasion of Crossing Clear Creek, a solo exhibtion at Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago

©2025

moniquemeloche is pleased to present Arvie Smith: Crossing Clear Creek, the artist’s second solo exhibition with the gallery. Smith is a 2024 recipent of the Guggenheim Fellowship in Fine Arts, with an artistic career spanning over four decades. His ongoing passion for advancing social and racial justice is reflected through his narrative paintings depicting historical and contemporary policies, influencers, bigotry, and institutional white supremacy, transforming the history of oppressed and stereotyped segments of the American experience into lyrical two-dimensional master works. While the works’ emotional rage, burden and determination are expressed through movement, color and sound, Smith has historically shelved his own underlying agony, revelations and the impact of living in Black skin—an element at the core of his work that has been rarely disclosed until now. At 86 years old, Smith has made the courageous shift from public to personal, bringing his own history into dialogue with the current conditions.

Crossing Clear Creek presents an autobiographical body of work that portrays a significant time in the artist’s life, revealing memories of events and emotions he experienced in his youth during his migration from Jim Crow-era rural Texas to South Central Los Angeles, a city laden with violent crime and gang activity that would become the center of the Civil Rights Movement. Here, Smith shapes an intimate journey of identity, resolve and deliverance, a story he has never shared or acknowledged in its entirety. This new personal narrative led Smith to receiving the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, a mark of distinction that emphasizes the importance of the recipient’s unique vision and artistic voice, serving as the impetus for his solo exhibition.

The exhibition’s title Crossing Clear Creek is explicit and metaphoric. Clear Creek, a body of water that runs through Roganville, Texas–Smith’s hometown–must be crossed in order to travel from the “Black side of town to the white.”

Grounding the exhibition, Smith’s massive two-part painting of the same name presents hopeful crossers on horseback pulling a chariot, eyes forward toward the winding path of a perceived better future as symbolized by a large white castle in the distance. Metaphorically, Smith addresses the state of the country and how the shifts in systems and policies affect people’s lives. His subjects are women and people of color, representing the marginalized groups who become pawns, creating tension and uncertainty as the ruling leaders play the cynical game of give and take. For the artist, Crossing Clear Creek symbolizes the transition of himself and his siblings from their early years in the South to a land where the promise of better times remained elusive.

Art has been an ever-present facet of the artist’s life. From copying Michelangelo’s Renaissance masterpieces in his grandfather’s single room elementary school in Roganville, to becoming the self-proclaimed “school artist” at his high school in Los Angeles, to being dissuaded from applying to art school by a racist receptionist, Smith reflects that his early development in art ran parallel with his formation as a Black citizen—”as a child, I understood that the Black man’s life is disposable; as an adult, I understood that I could use art as a means of comprehending and explaining what it is like to be a person of color in America…The recognition conferred on me by the Guggenheim Fellowship in Fine Arts is the most meaningful artistic honor of my lifetime. This acknowledgement and support led me to create this body of work. I embarked on this exhibition with a heightened sense of significance and purpose.”

Bare Witness by

Dr. Kiara Hill

“If time had a race, it would be white. White people own time. It’s in the way we narrate history, in the way we attempt to shove the negative truths of the present into the past, and the way that we argue that the future that we hoped for is the present in which we are currently living.”1 – Dr. Brittney Cooper

In her 2017 TED Talk, “The Racial Politics of Time,” cultural theorist Dr. Brittney Cooper meticulously elucidates the ways that time, and more specifically, the Western construct of time, distorts our understanding of how white supremacy shapes the lived experiences of marginalized groups. When social regression is falsely presented as social progress, the violent effects of systemic oppression on vulnerable populations are obfuscated and, at times, justified to support the illusion of forward movement. For Black folks specifically, this has meant grappling with the longstanding effects of anti-Black

1 “Cooper, Brittney. ‘The Radical Politics of Time’ TED, Mar. 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kTz52RW_bD0&t=141s

The Switch, 2024, oil on canvas, 60 x 48 in (detail)

racism, which, when indicated, are met with skepticism and exasperation despite the persistence of racial tensions. Cooper characterizes these tensions as “clashes of time and space” that leave us unable to discern the past from the present—resulting in lost time for Black people: loss of memories, time spent with loved ones, dreams, healthy quality of life, and at times, the optimism that things will ever get better. However, if we are to learn anything from our elders, it is that the will to survive requires us to see ourselves as agents that defy time by refusing to forget—a sentiment that fuels the practice of Portland-based figurative painter, Arvie Smith. If there’s one lesson to be gleaned from his latest body of work, Crossing Clear Creek, it is the understanding that memory is resistance. The refusal to adhere to any construct of time that is predicated on the negation of one’s history and lived experiences is how you reclaim your power.

Like Cooper, Smith is acutely aware of the fact that white people own time, which is why for the last sixty years, his practice has centered on revealing the historical, social, and cultural forces that animate and camouflage the pernicious nature of systemic racism. Having spent his early life in Texas and being only three generations removed from slavery, Smith has lived long enough to understand that time is nonlinear: the past is never just the past, the future is never divorced from the present, and oftentimes, the illusion of progress is just that, an illusion. An axiom he articulates through ambiguity rather than didacticism, Smith employs movement, color, and a kaleidoscope of historical and contemporary references in what he has described as his most personal paintings to date. While his work throughout the years has been informed to some extent by his lived experiences, this newest series closely examines the insidious effects of racism by revisiting “clashes of time and space” in Smith’s early life; moments that have indelibly shaped his perceptions of race, gender, and anti-Blackness.

To be clear, these paintings shouldn’t be read as literal or linear representations of these experiences—rather as variations on memories, an approach inspired by the poetry of Langston Hughes:

“I didn't want to be totally literal. I was reading some Langston Hughes poems, and he talked about variations on a dream. Well, mine is variations on my life because I’m not putting it in a linear kind of context. I'm kind of jumping all around, but it's all me, and I'm trying to get inside of me, to figure out, what are the things I really remember?”2

If the construct and narration of time is, in fact, white, then how does memory, and more specifically the act of refusing to forget, reveal and subvert this idea? In this case, memory serves to contextualize historical events alongside moments of “lost time” and personal discovery, allowing viewers to better understand the cyclical nature of white supremacy, which Smith illustrates through recurring motifs that include a carousel, slave ship, American flag,

2 “Smith, Arvie. “Interview.” Conducted by Dr. Kiara Hill, 21 Jan 2025.

The Reading, 2024, oil on canvas, 72 x 60 in (detail)

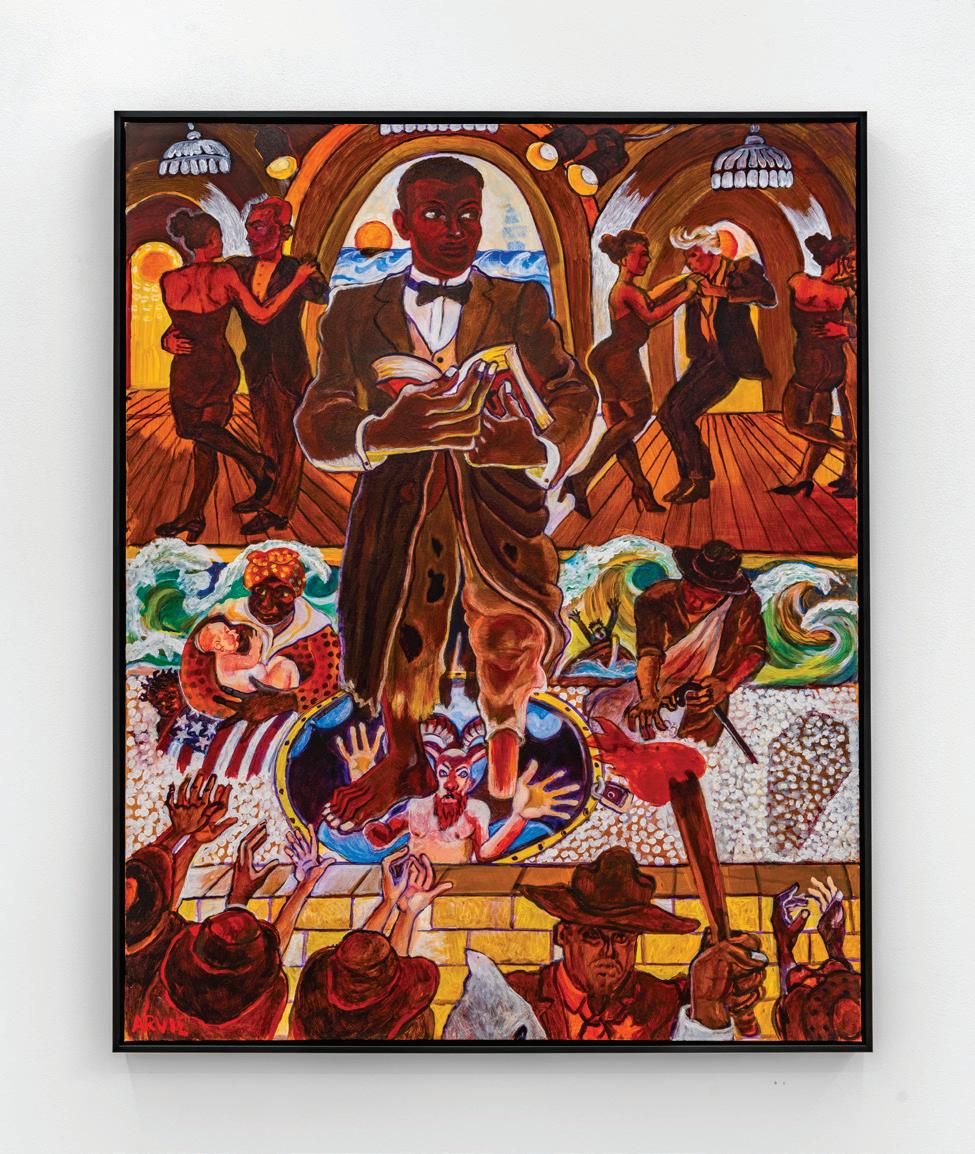

and Jim Crow-esque figures. Paintings like The Switch and The Reading give us context for his early years as a young boy navigating the ills and contradictions of segregation in Clear Creek, TX. In both works, he employs his distinctive warm color palette and brilliant use of symbols to articulate the aspirations of many African Americans— himself included—who endeavored to leave the Jim Crow south in search of a better life, only to discover that the land of “milk and honey,” in Smith’s case South Central Los Angeles, was not exactly void of the racial discrimination and violence that prompted their migration. Ole School, Stage Door, and Mr. Wilson’s Barbershop reflect Smith’s teenage years in Los Angeles. Here, his command of light and shadows conveys the precariousness of life for Blacks living in urban spaces during the 1960s. Gang violence, police brutality, prostitution, and drug use were just some of the issues Smith witnessed and experienced while living in the “ghetto.” Additionally, his inclusion of Tell Mama All About It, which he painted over 30 years ago, tackles police brutality from another perspective: his sister’s— who was sexually assaulted by a police officer. Unfortunately, the sexual abuse of poor Black women by LAPD officers was a recurring narrative for young women in his neighborhood, an issue that persists today at alarming rates.3 Smith deftly articulates the prevalence of this experience by juxtaposing the image of a Black woman, whose melancholic expression conveys a palpable angst, shielding her

3 Morris, Linda and Borchetta, Rolnick, Jenn. “Taking Action to Stop Police Sexual Violence.” ACLU, American Civil Liberties Union, 19, Oct. 2023, https://www.aclu.org/news/criminal-law-reform/taking-action-to-stop-olice-sexual-violence.

Accessed 10 Feb 2025

3 Morris, Linda and Borchetta, Rolnick, Jenn. “Taking Action to Stop Police Sexual Violence.” ACLU, American Civil Liberties Union, 19, Oct. 2023, https://www.aclu.org/news/criminal-law-reform/taking-action-to-stop-police-sexual-violence. Accessed 10 Feb 2025 19

Tell Mama All About It, 1991, oil on canvas, 67 x 87 in (details)

crotch, alongside the unfazed disposition of a headless white man in a power suit. As if to say, be it a police uniform or a business suit, unchecked power leads to corruption, corruption engenders violence, and despite the amount of time that passes, there are some wounds that never fully heal.

Due to discriminatory housing and employment policies, Blacks and other minority groups were relegated to poverty-stricken areas, which made them more susceptible to various forms of police brutality and restricted their access to quality schools, social services, and adequate housing. Many of these areas have since become

targets for gentrification efforts, resulting in the displacement of countless historic Black communities across the country. Nevertheless, despite these circumstances, historic institutions like the Blackowned Dunbar Hotel, one of the focal points of Stage Door, and the presence of street-corner music groups and Black businesses offered some reprieve amidst a turbulent racialized landscape.

As a child, Smith’s grandmother used to tell him to “watch the signs,” a theme he explores in the painting Maleyka, which translates to “angel” in Fulani. Smith is a descendant of the Fulani peoples of Nigeria, which he learned after taking a genealogy test. As a spiritual person, he believes there are unseen forces—like his grand-

Maleyka, 2024, oil on canvas, 60 x 48 in (detail)

mother—who guide and protect him. He has imbibed and imbued this sentiment through the illustration of a supernatural Black femme, whose soft gaze is averted, as she calmly hangs from a trapeze, whilst holding a peregrine falcon—the fastest bird in the world—a symbol he uses to represent the speed at which Black people have come out of slavery. For Smith, she represents a kind of calmness and reassurance. Motion, achieved through an array of flowing lines and kinetic symbols, is used to emphasize her rootedness despite the energy and symbols of subjugation that surround her. To this day, Smith attributes his keen sense of discernment to his grandmother—a gift that has sustained him as he’s traversed the highs and lows of his life and longstanding career as a Black artist living and working in what was once considered a whites-only state.

Given the polarizing socio-political climate, the diptych Crossing Clear Creek serves as both a meditation on the present moment and a premonition of what’s to come. This contemporary istoria4—a compositional approach likely informed by Smith’s technical train-

4 Allegorical narrative painting with intricate composition involving multiple figures. Term coined during the Renaissance period by Leon Battista Alberti in his seminal treatise on painting, De pictura (1455).

Crossing Clear Creek, 2024, oil on canvas, 72 x 120 in

ing in Renaissance art—metaphorically unpacks multiple themes: women’s rights, the impact of racial discord on people of color, the rise of white nationalism and Donald Trump, and the arduous migration across Clear Creek River from rural East Texas to South Central Los Angeles, undertaken by Smith, his siblings, and his mother. In this piece, the subversion of time is conveyed through a mix of contemporary and historical figures that include the Loch Ness Monster, Donald Trump, a hand maiden, and his signature Jim Crow-esque character. Istoria paintings from the Renaissance period typically include a figure whose gaze directly communicates with the viewer. In this case, the frightened expression of the horses as they traverse the unstable bridge communicates a grave warning: if we fail to attend to the exigencies of yesterday and today, the consequences will be dire for us all.

Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé, “Dancing in an Enclosure: Activism and Mourning in the Puerto Rican Summer of 2019” Small Axe 26, no. 2 (2022): 23. José Esteban Muñoz, “The Sense of Watching Tony Sleep,” in After Sex? On Writing Since Queer Theory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 142.

Arnaldo Cruz-Malavé, Queer Latino Testimonio, Keith Haring, and Juanito Xtravaganza: Hard Tails (New York: Routledge, 2007), 95.

Crossing Clear Creek, 2024 (detail)

Smith’s invitation to bear witness to deeply personal moments in his life can be interpreted as a kind of call to action to pay attention to what is happening around us: “Nothing happens by chance; everything is by design.”5 Despite efforts to rebrand age-old white supremacist beliefs through catchy slogans like “Make America Great Again,” Smith reminds us how endemic racism and anti-Blackness have always been to the fabric of America. While “time” may not be on our side, history is, and we must preserve that history so that future generations will never forget it. In the wise words of writer Zora Neale Hurston, “If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.” May we take a lesson from Arvie Smith and never give them that satisfaction.

5Smith, Arvie. “Interview.” Conductd by Dr. Kiara Hill, 21 Jan 2025.

Crossing Clear Creek, 2024 (detail)

Installation Views

Maleyka, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 48 in 152.4 x 121.9 cm

Tell Mama All About It, 1991 oil on canvas

67 x 87 in 170.2 x 221 cm

The Reading, 2024 oil on canvas

72 x 60 in 182.9 x 152.4 cm

The Switch, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 48 in 152.4 x 121.9 cm

The Sun Do Move, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 48 in 152.4 x 121.9 cm

Crossing Clear Creek, 2024 oil on canvas

72 x 120 in 182.9 x 304.8 cm

Mr. Wilson’s Barber Shop, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 72 in 152.4 x 182.9 cm

Ole School, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 48 in 152.4 x 121.9 cm

Stage Door, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 48 in 152.4 x 121.9 cm

In an artistic career spanning over 4 decades, Arvie Smith transforms the history of oppressed and stereotyped segments of the American experience into lyrical two-dimensional master works. His paintings use common psychological images to reveal deep sympathy for the dispossessed and marginalized members of society in an unrelenting search for beauty, meaning, and equality. Smith’s work reflects powerful injustices and the will to resist and survive. His memories of growing up in the Jim Crow South add to his awareness of the legacy that the slavery of African Americans has left with all Americans today. His intention is to solidify the memory of atrocities and oppression so they will never be forgotten nor duplicated.

Smith (b.1938, Houston, TX) holds an MFA from the Hoffberger School of Painting, Maryland Institute College of Art and a BFA from Pacific Northwest College of Art. Smith studied at Il Bisonte and SACI in Florence in 1983. He has had solo exhibitions at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Salem, OR (2022); moniquemeloche, Chicago, IL (2025, 2022); Jordan Schnitzer Museum, Portland, OR (2022); and Disjecta Contemporary Art Center, Portland, OR (2019). His work has been included in group exhibitions at the Venice Biennale, IT (2022); Galerie Myrtis (2019); UTA Art Space, Beverly Hills, CA; Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR (2017); and Upfor Gallery, Portland, OR (2020). Smith’s work is included in the group exhibition When Langston Hughes Came to Town at the Nevada Museum of Art, Reno, NV (May 2025), and will participate in the Baltimore Museum of Art x Sherman Family Foundation Residency in Camden, Maine, which was founded in 2024 (Summer 2025).

Smith’s work is held in the permanent collections of the Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR; Delaware Museum of Art, Wilmington, DE; Reginald F. Lewis Museum, Baltimore, MD; Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Salem, OR; Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK; Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon, Eugene, OR; the Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art, Asbury, NJ and the Pierce and Hill Harper Arts Foundation, Detroit, MI. Smith is a 2024 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow of Fine Arts. Smith lives and works in Portland, OR.

Dr. Kiara Hill is the James DePriest Visiting Assistant Professor of Art History in the Schnitzer School of Art + Art History + Design at Portland State University. She teaches courses on African American art and socially engaged art in the Art and Social Practice MFA Program. Hill earned her B.A. in Mass Communications at Sacramento State University, her M.A. in Women’s Studies at the University of Alabama, and recently completed her Ph.D. in Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts. Her research focuses on Black women artists and cultural workers. Hill is also a curator of African American visual art and culture and curator-in-residence at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr School Museum of Contemporary Art (KSMoCA).

Exhibition Checklist

Maleyka, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 48 in 152.4 x 121.9 cm

Tell Mama All About It, 1991 oil on canvas

67 x 87 in 170.2 x 221 cm

The Reading, 2024 oil on canvas

72 x 60 in 182.9 x 152.4 cm

The Switch, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 48 in 152.4 x 121.9 cm

The Sun Do Move, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 48 in 152.4 x 121.9 cm

Crossing Clear Creek, 2024 oil on canvas

72 x 120 in 182.9 x 304.8 cm

Mr. Wilson’s Barber Shop, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 72 in 152.4 x 182.9 cm

Ole School, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 48 in 152.4 x 121.9 cm

Stage Door, 2024 oil on canvas

60 x 48 in 152.4 x 121.9 cm

Monique Meloche Gallery is located at 451 N Paulina Street, Chicago, IL 60622

For additional info, visit moniquemeloche.com or email info@moniquemeloche.com