Antonius-Tín Bui

There are many ways to hold water without being called a vase

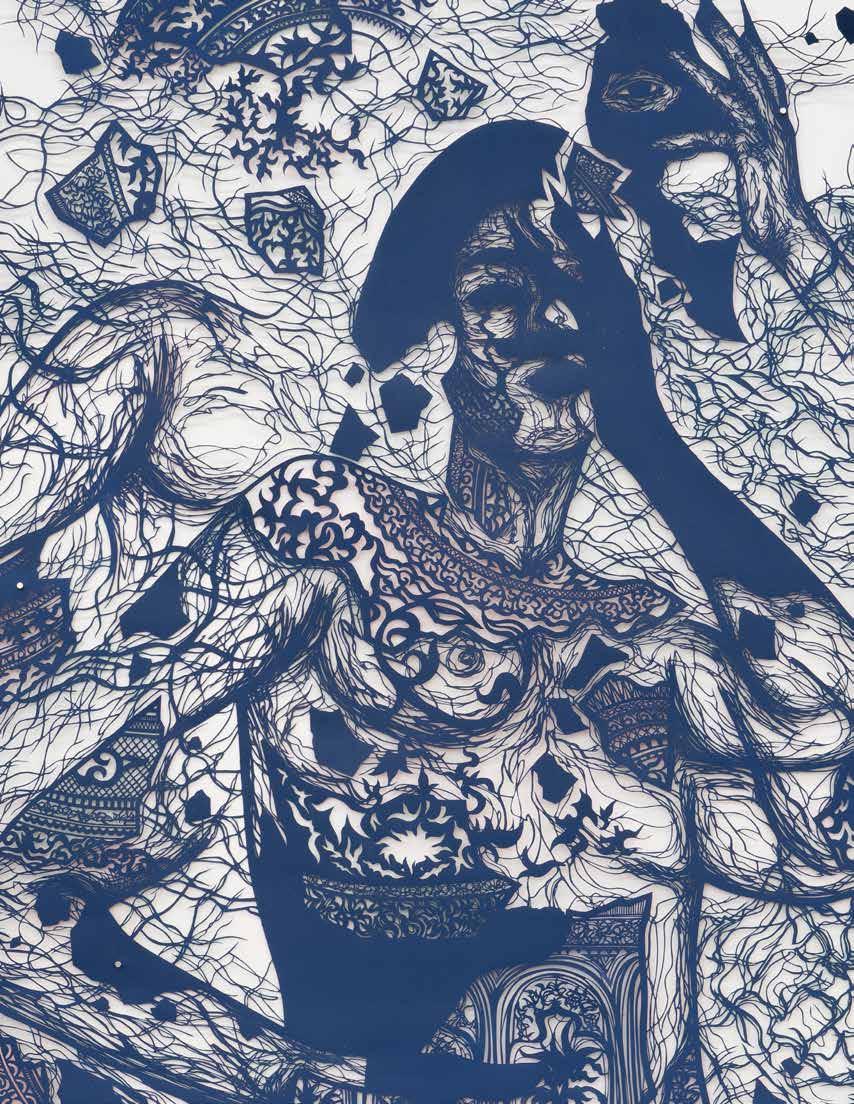

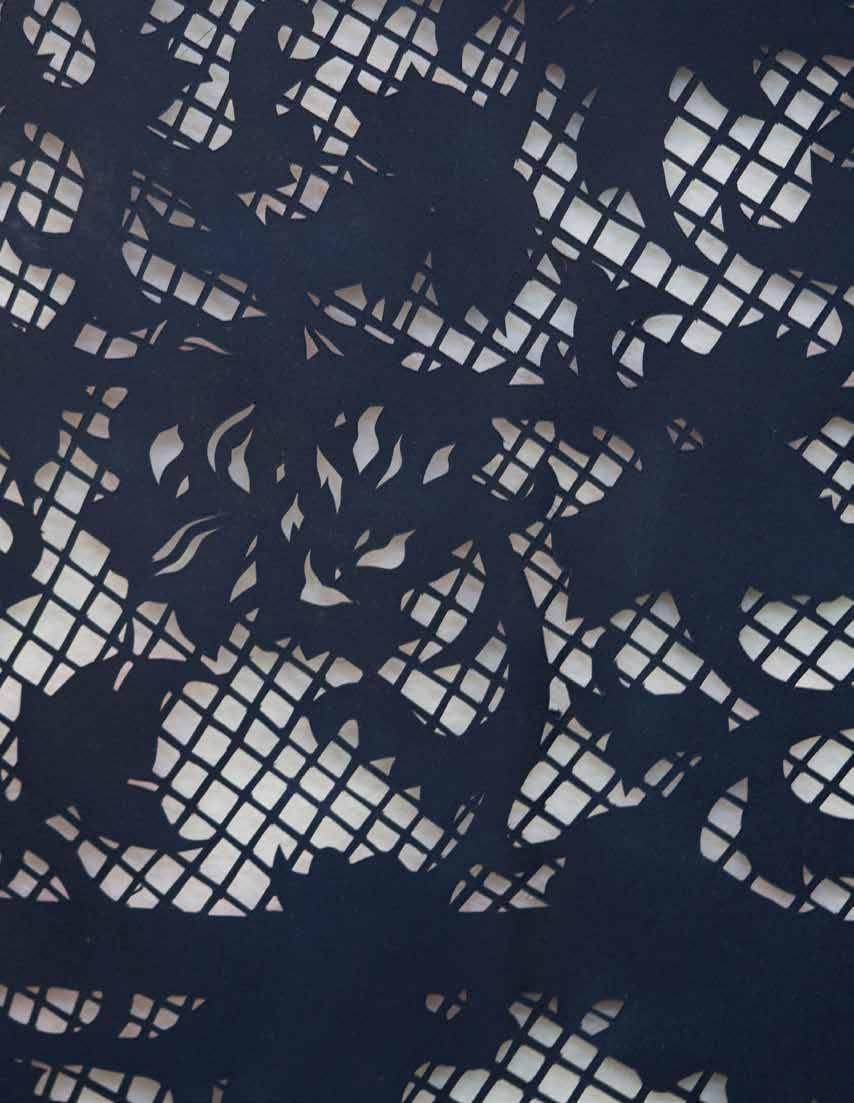

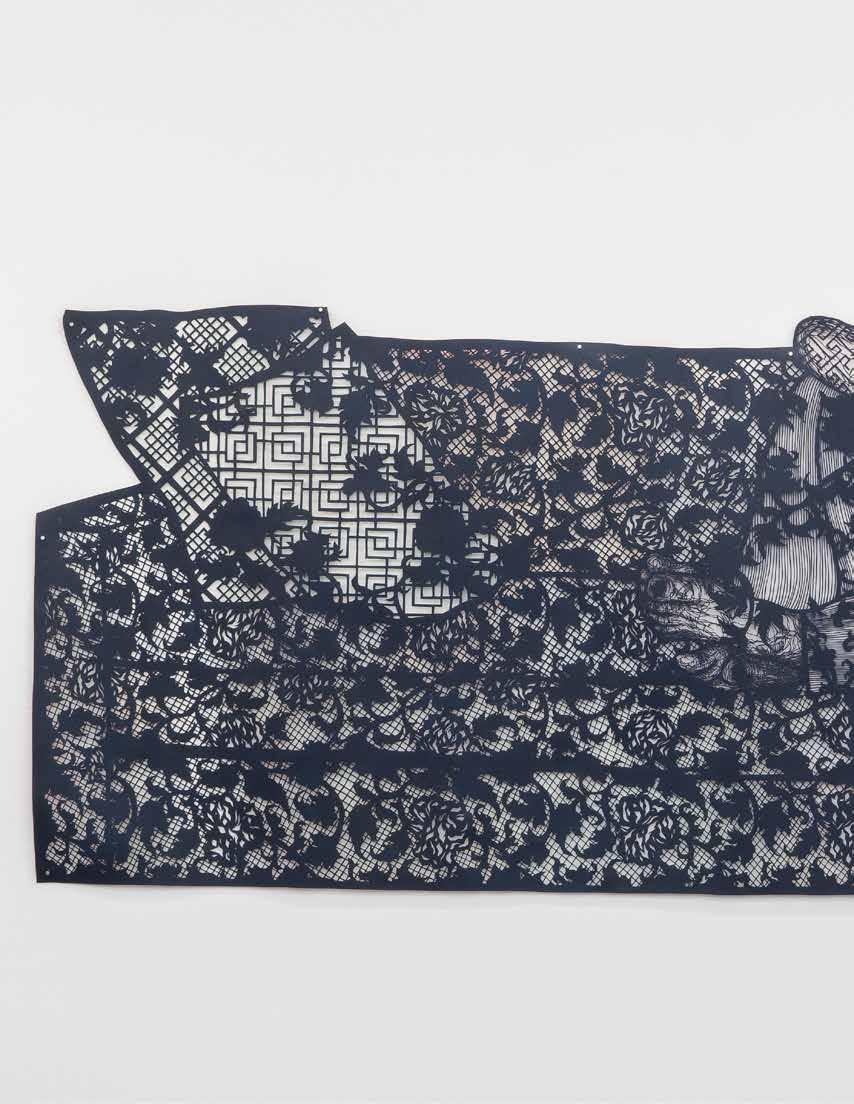

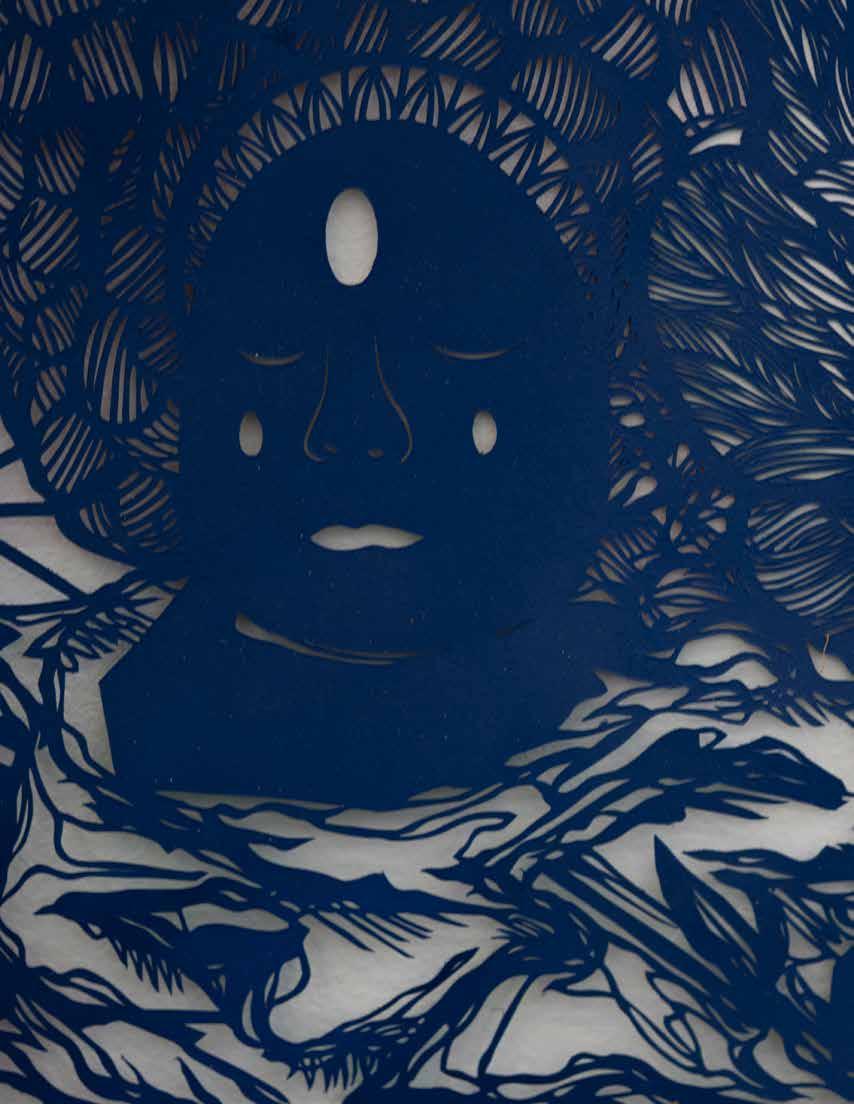

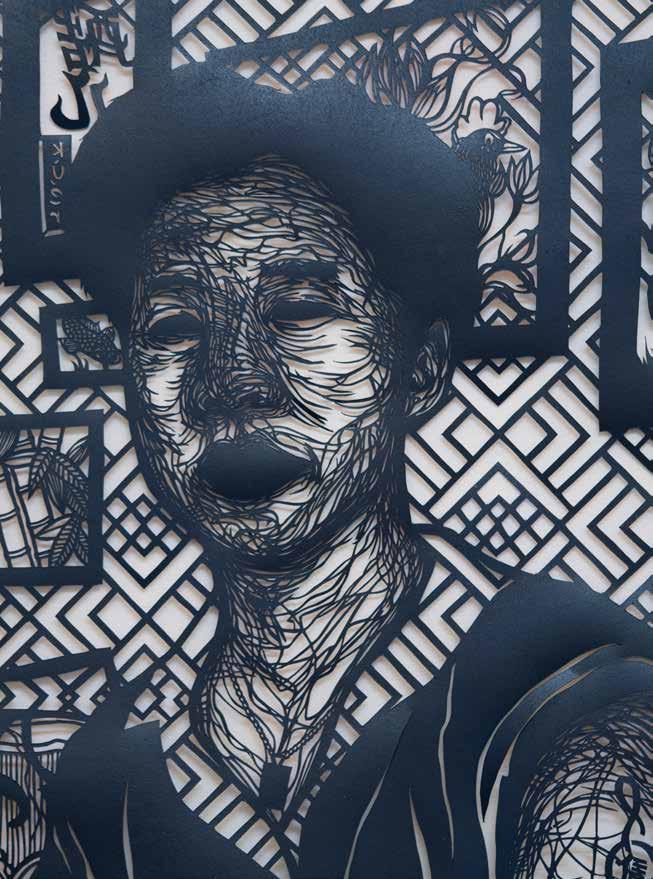

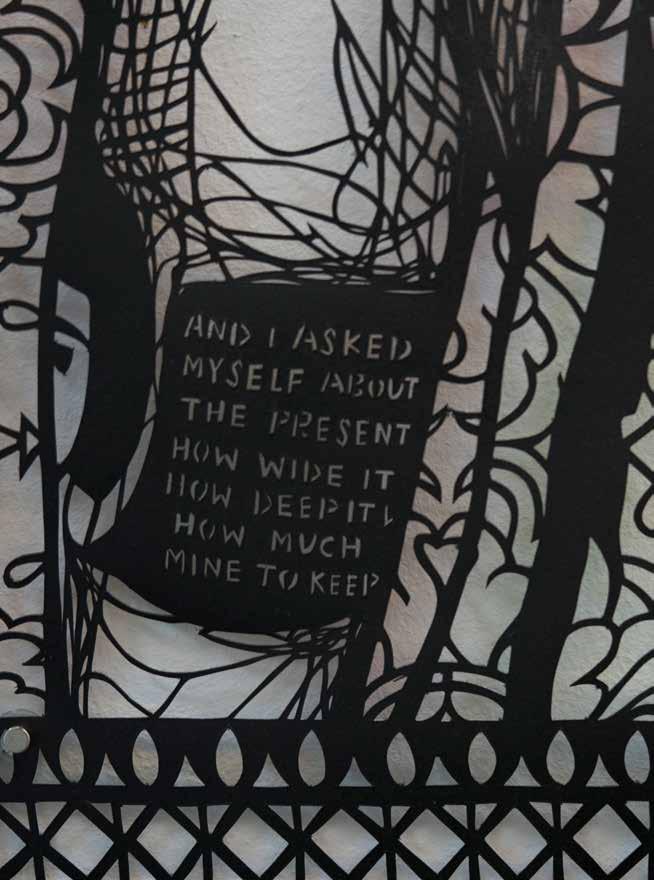

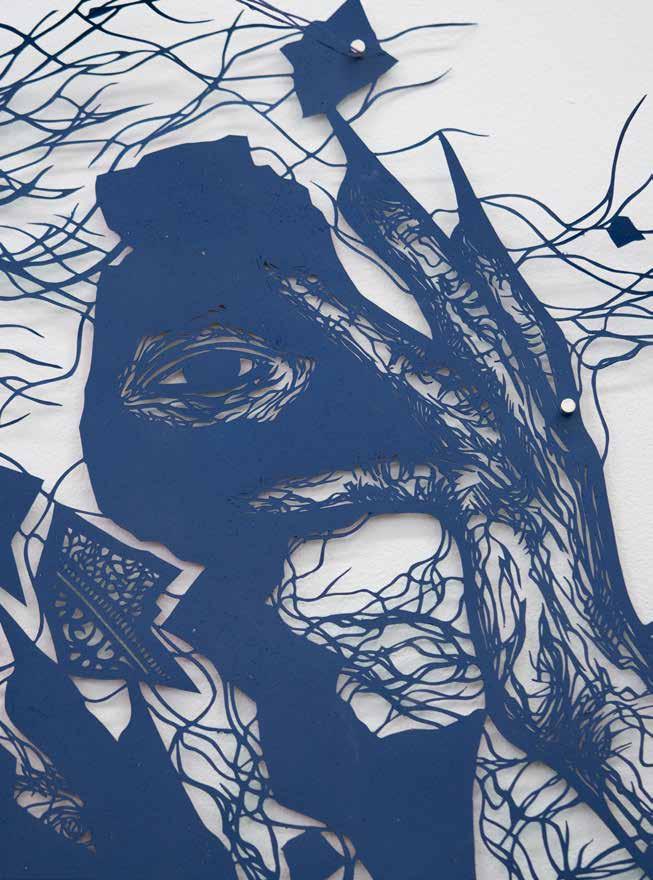

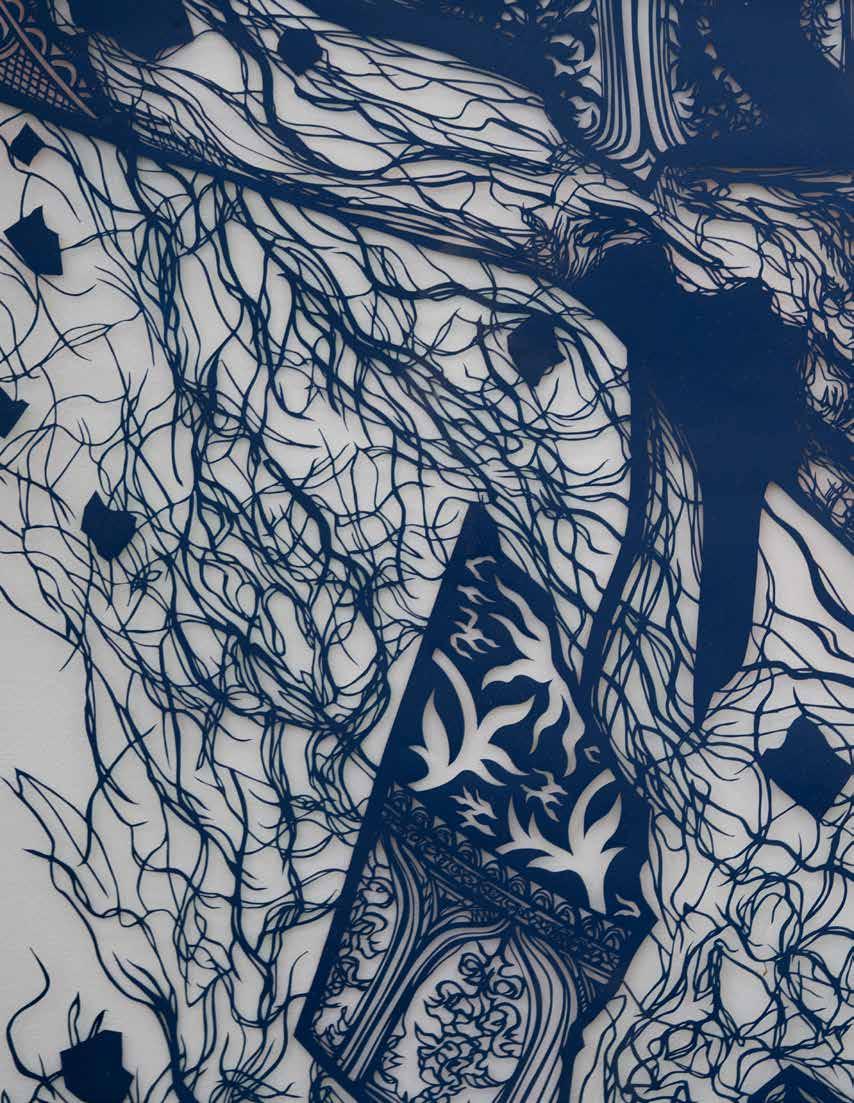

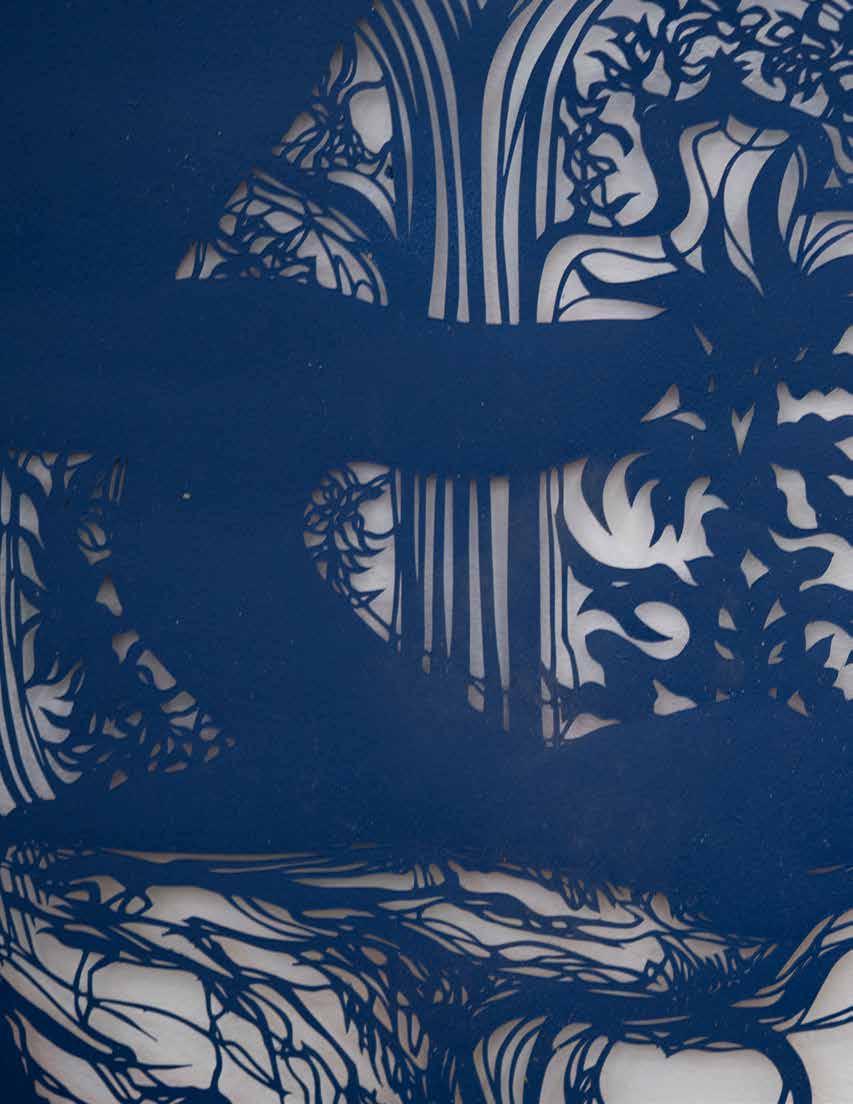

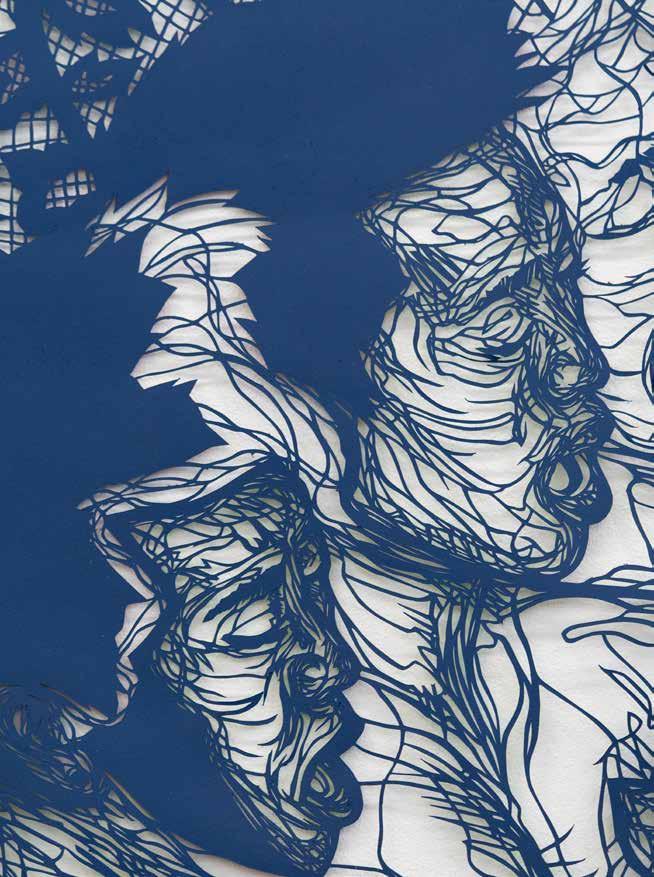

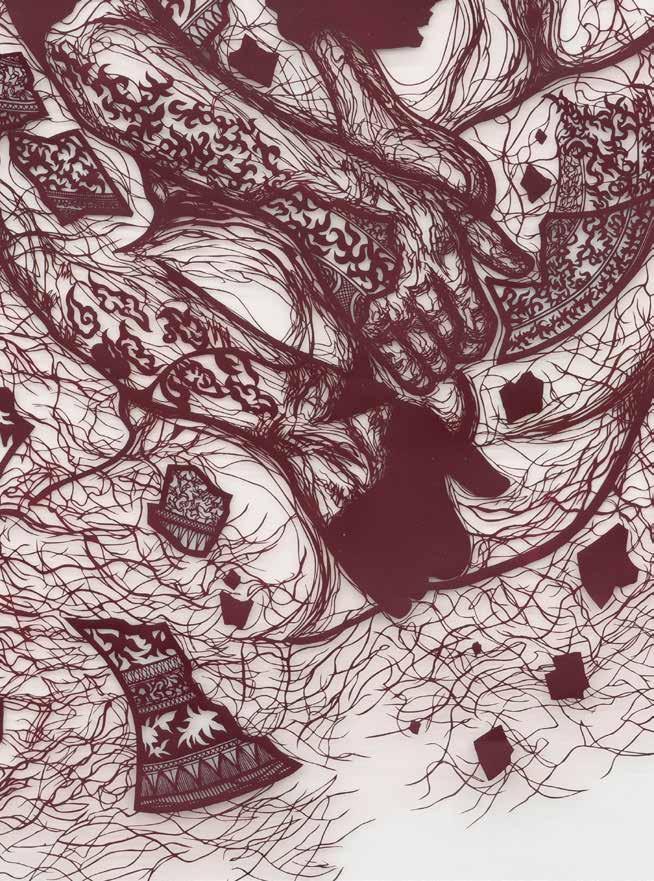

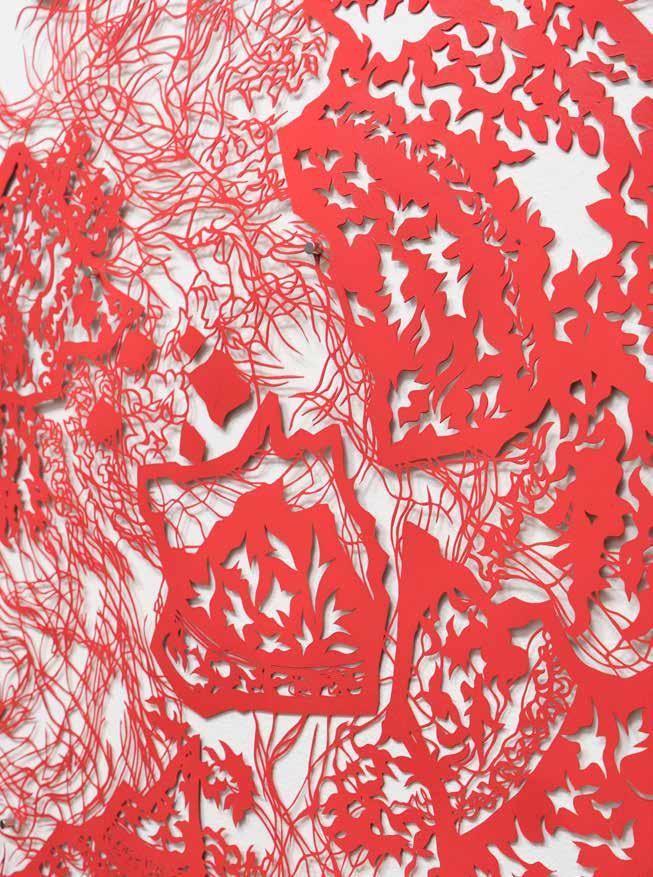

Front and back cover: There are many ways to hold water without being called a vase. To drink all the history until it is your only song., 2022 (detail)

There are many ways to hold water without being called a vase

Front and back cover: There are many ways to hold water without being called a vase. To drink all the history until it is your only song., 2022 (detail)

There are many ways to hold water without being called a vase

Monique Meloche Gallery

June 9-July 29, 2023

Introduction by Alyssa Brubaker

Essay by Francesca Gavin

Designed by Megan Foy

Edited by Staci Boris

Photographed by Robert Chase Heishman

This catalogue was published on the occasion of Antonius-Tín Bui’s second solo exhibition at Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

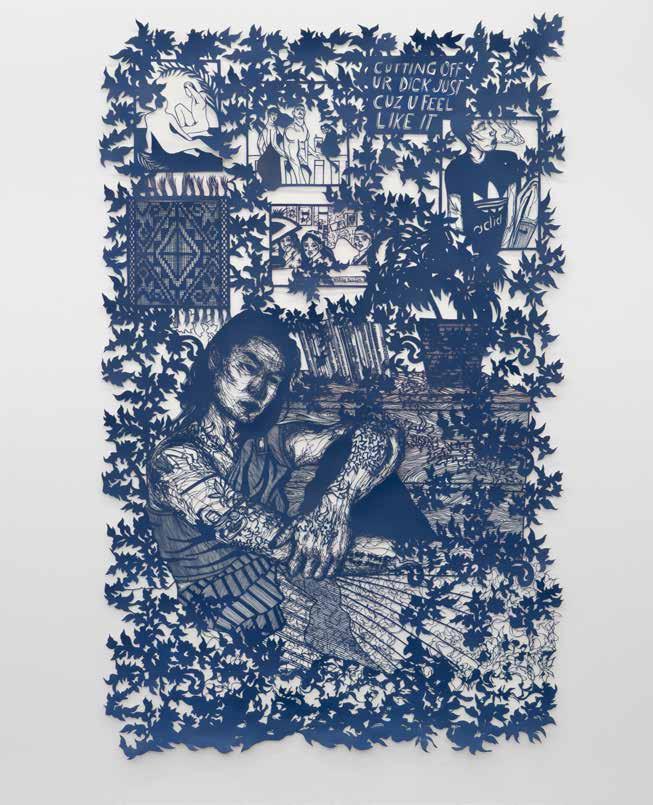

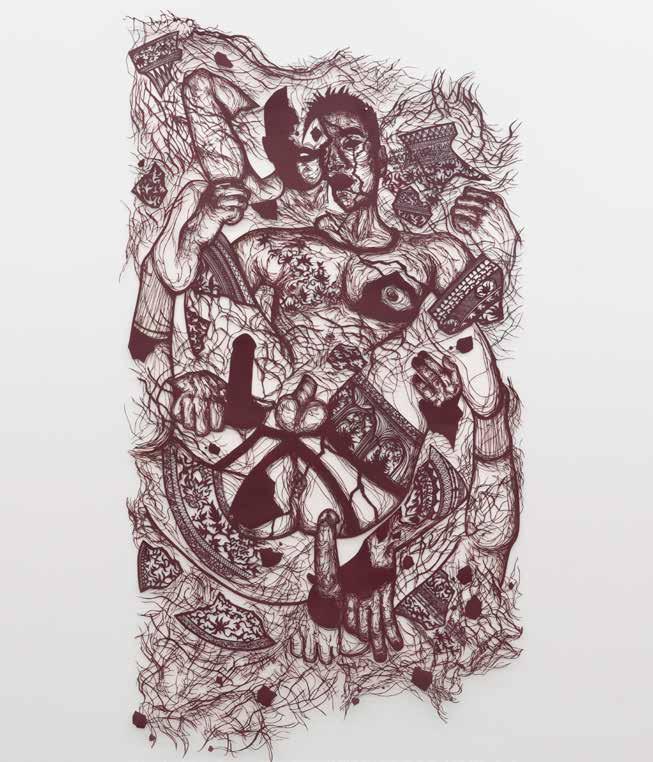

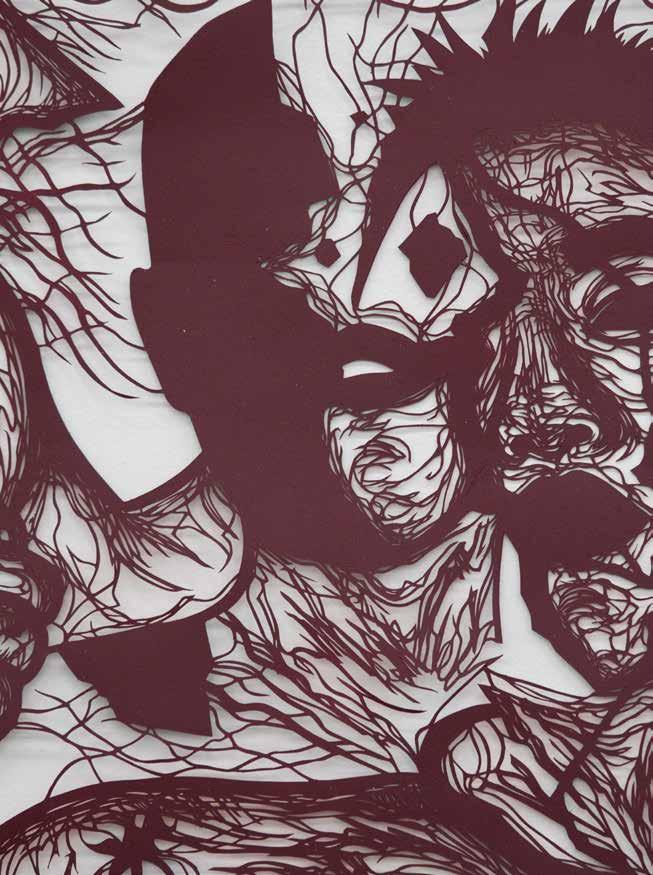

With an intuitive sense of beauty and precision in practice, the exhibition offers the artist’s new series of hand-cut works on paper, portraits of individuals and artifacts that have shaped Bui’s exploration into their Vietnamese heritage, the poetics of queerness, gender fluidity, the politics of identity, and reshaping silence. Their works are a panorama of metamorphosis, portraits that bear witness to whole beings in their myriad complexities which are carved in precious detail to communicate each person’s unique journey of breaking and becoming—rejecting stereotypes, shame, and internalized racism experienced by the AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) community by depicting scenes of intimacy, sexuality, and emotional release with nuance, sanctuary, and, in moments, ecstatic eruption.

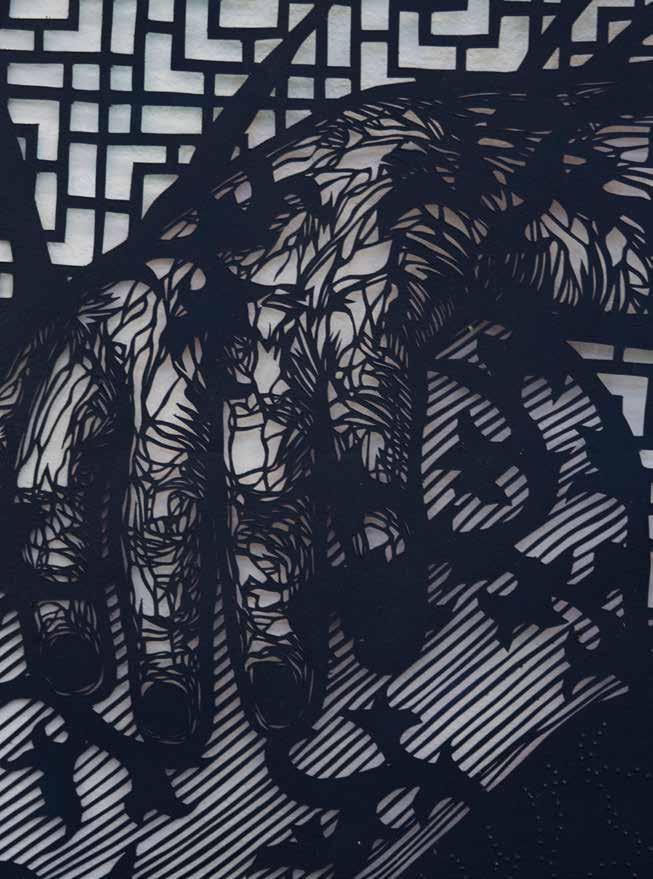

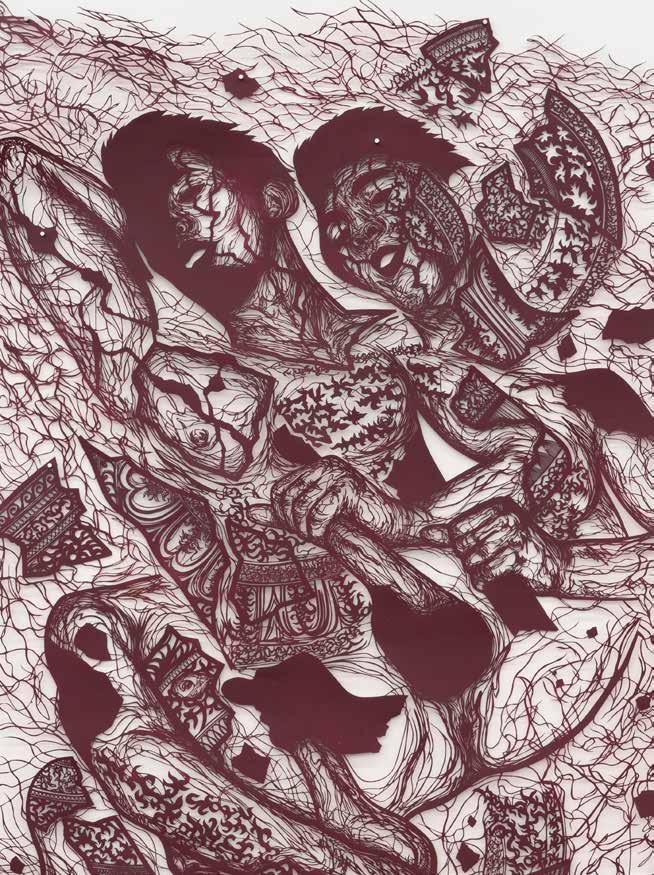

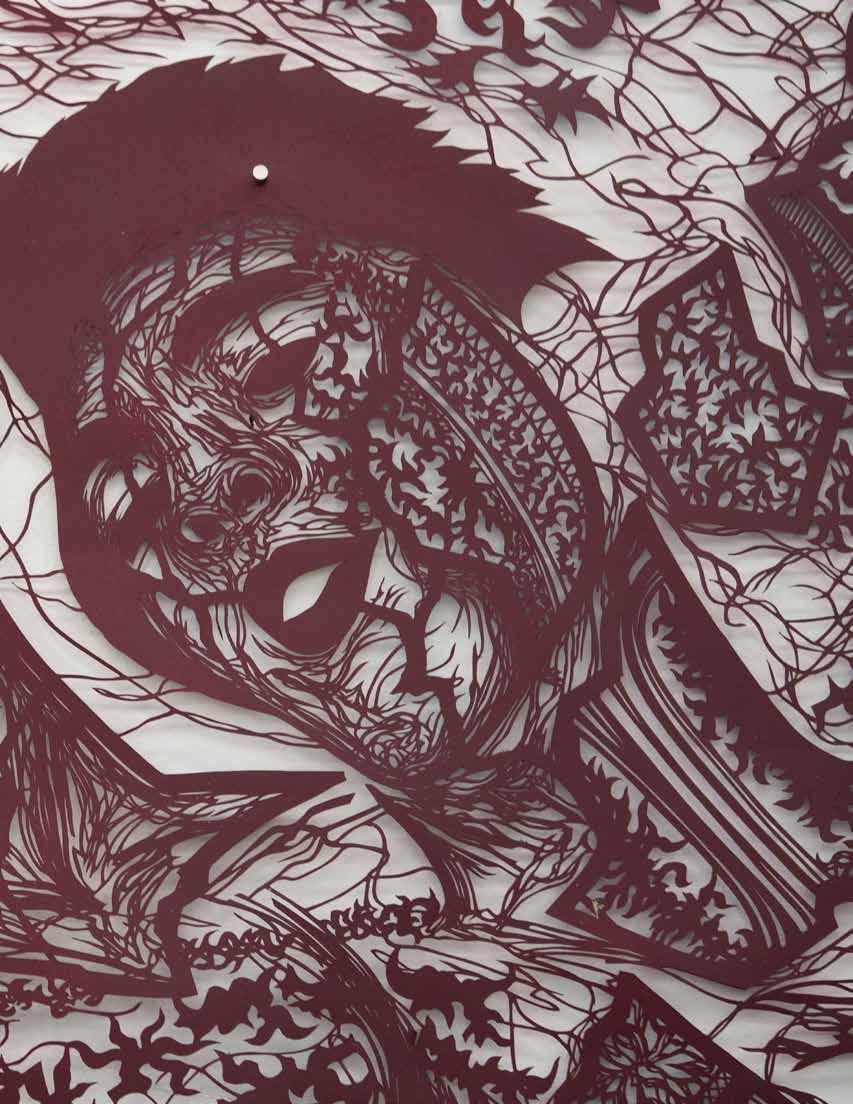

Between both galleries, Bui interlaces personal subjects with archival objects, featuring images of friends, relatives, artists, porn stars, historic figures, and deceased creatives. Among these portraits are Nicholas Oh and Ayoung Yu, artists Bui has collaborated with for many performances, and Anthony Veasna So, the queer Cambodian American writer—individuals who provide Bui with a sense of possibility and guide them towards future understandings of themself. Other works present images of exploded vessels, fragments of ceramic vases from Asian art collections that Bui activates to confront Western institution’s historic practice of siloing Southeast Asian cultural narratives by emphasizing porcelain, resulting in an overgeneralized Orientalist perspective of the past. Further contending with the history of Orientalism, a series of new works explores Asian American masculinity and sexual representation with an examination of gay male pornography. Challenging the role the pleasure of porn plays in securing a consensus about race and desirability, Bui renders the association of bottomhood with Asian submission, abjection and anonymity. By depicting pornographic depictions of Asian men, Bui highlights and reclaims the mainstream media portrayal of Asian men as effeminate and asexual, restoring their power and autonomy by rendering them breaking through traditional vessels and shattering stereotypes. Bui shatters these vessels and subjects and reassembles them, tapping into the messiness, tensions, and trappings of visibility. In homage to each subject, Bui likens the hand-cut works to Joss paper: a ceremonial parchment burned as an ancestral offering in pan-Asian culture. To them, the act of burning symbolizes “the delicate dance between negative and positive space, presence and absence, and how so

much of our formulation is through what we reject or take away.” Instead, they propose “purging societal projections of who we should be, burning away expectations, unlearning our ideas of gender and sexuality.”

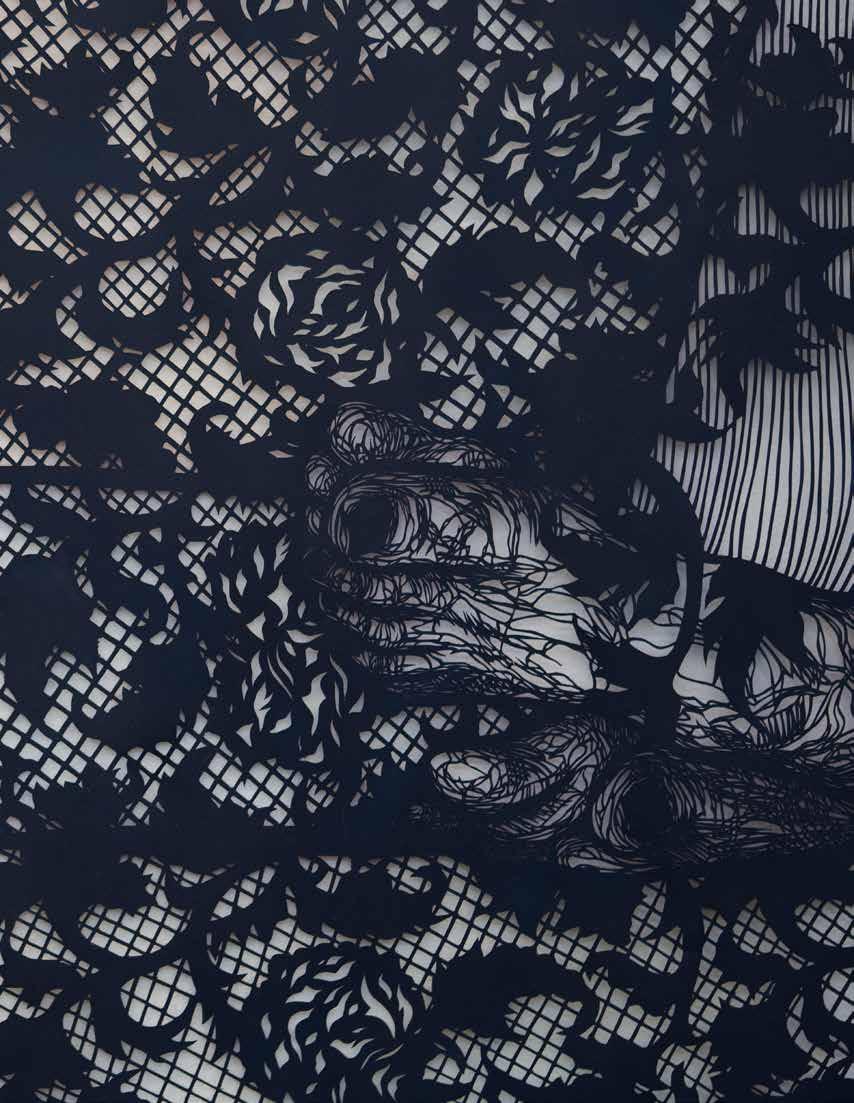

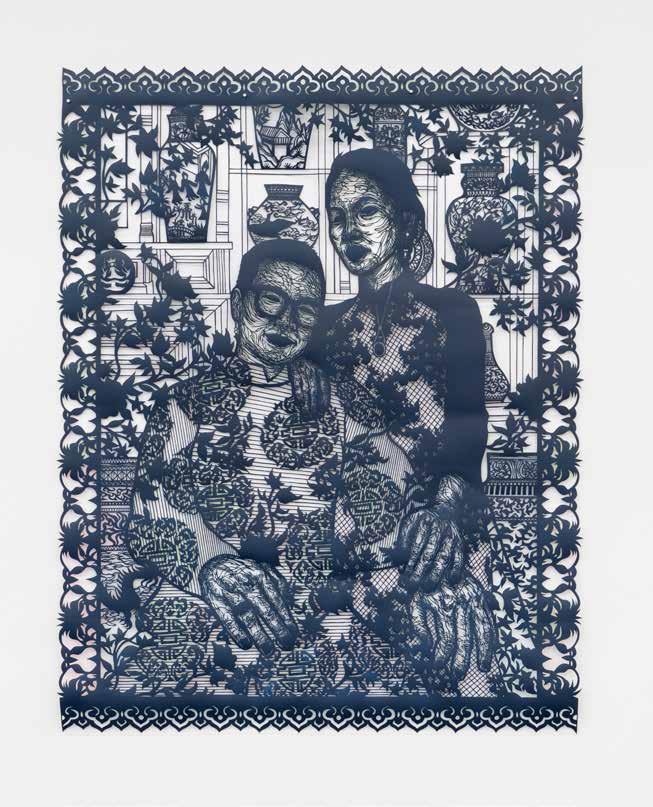

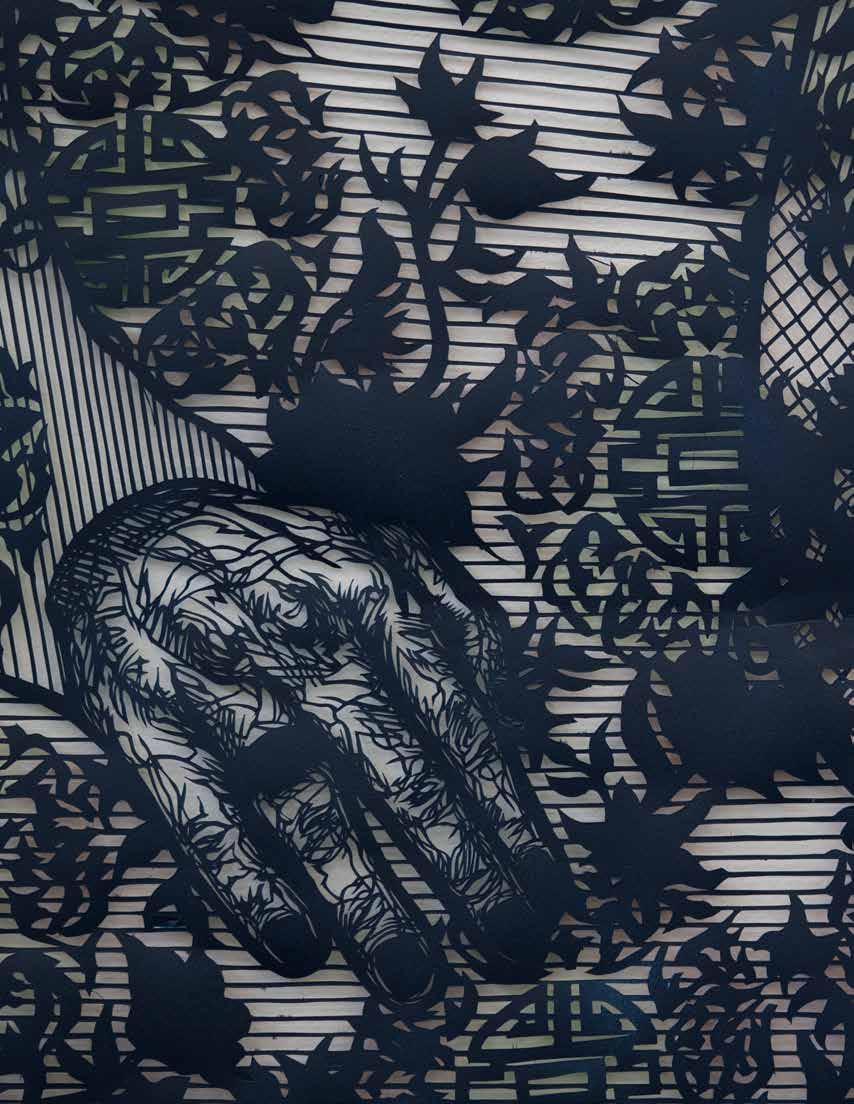

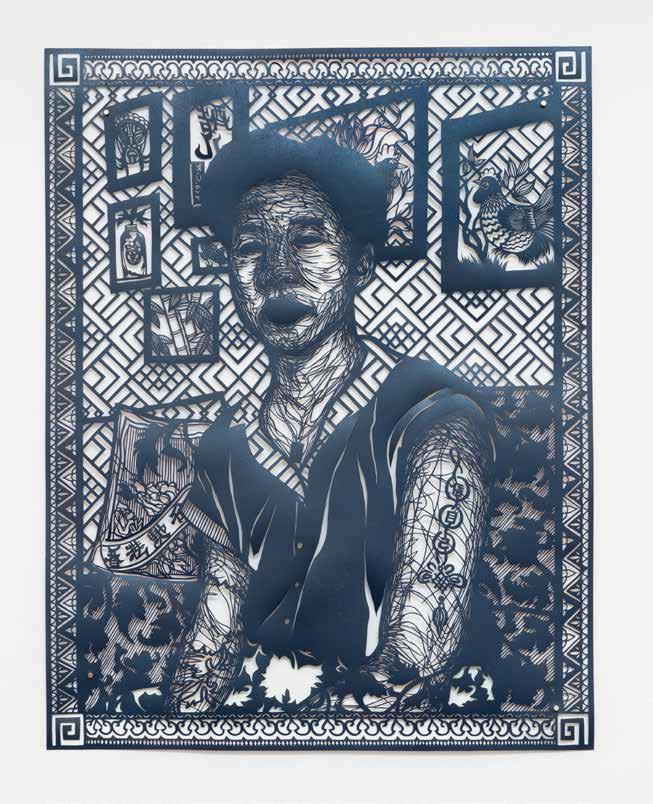

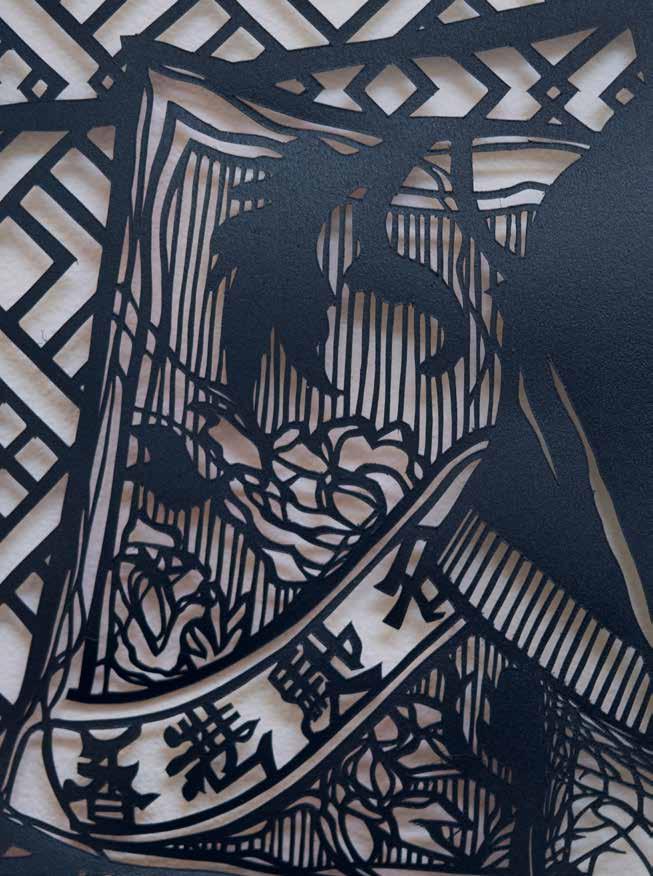

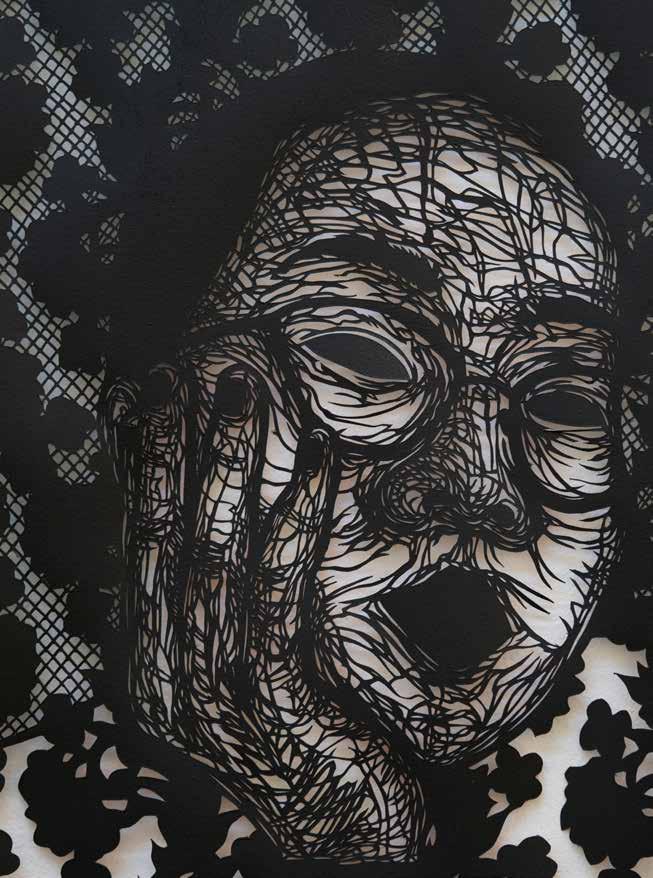

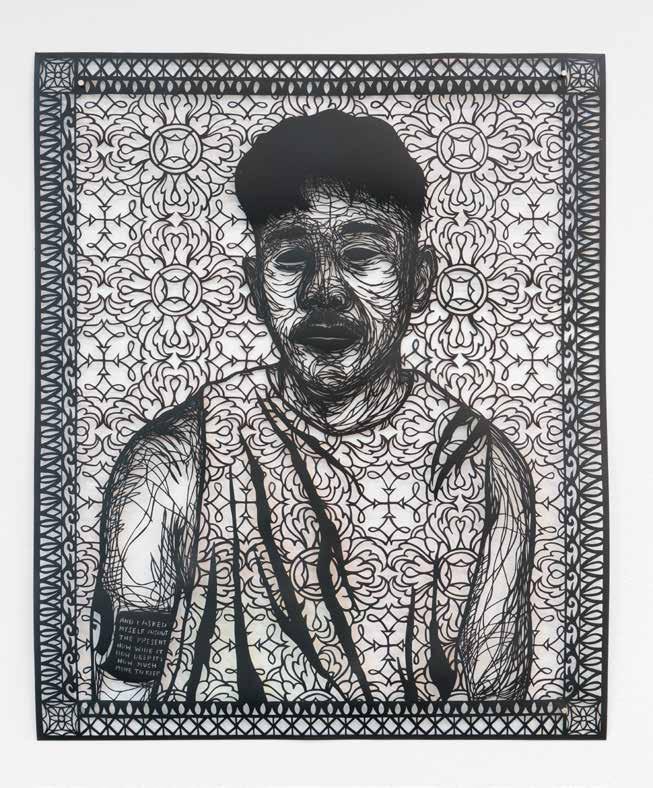

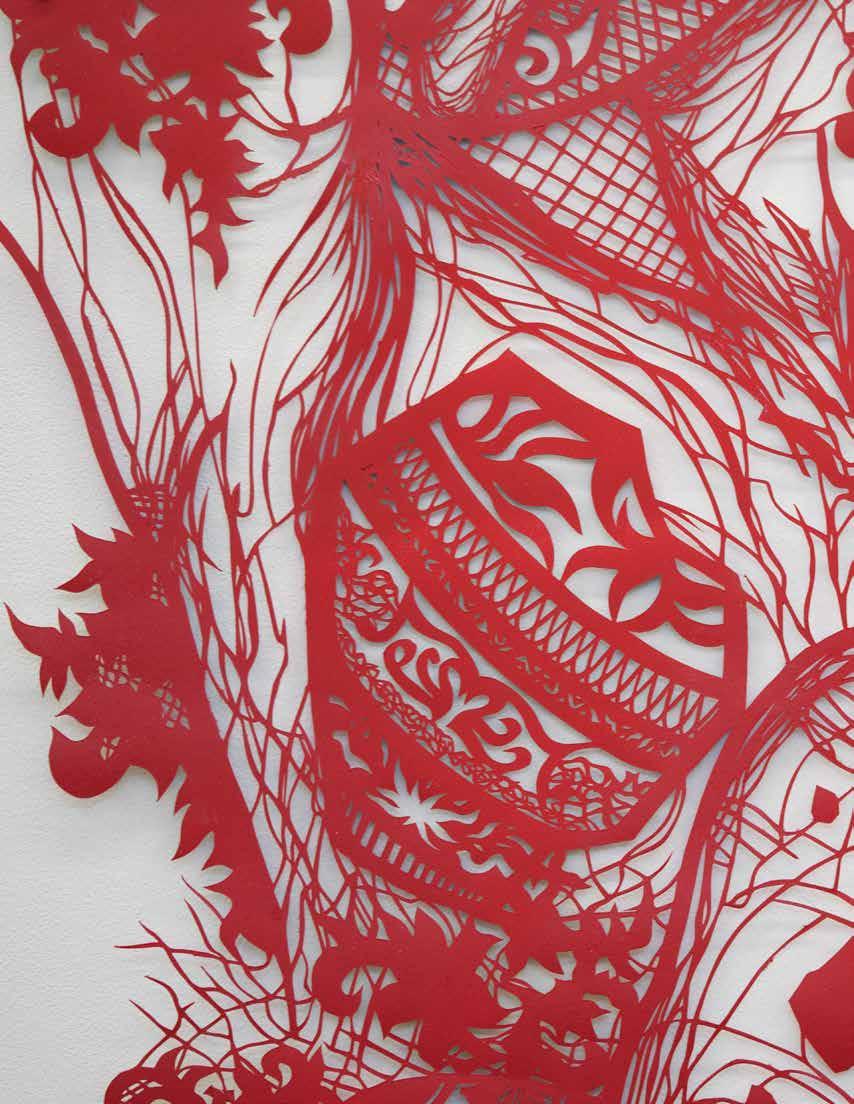

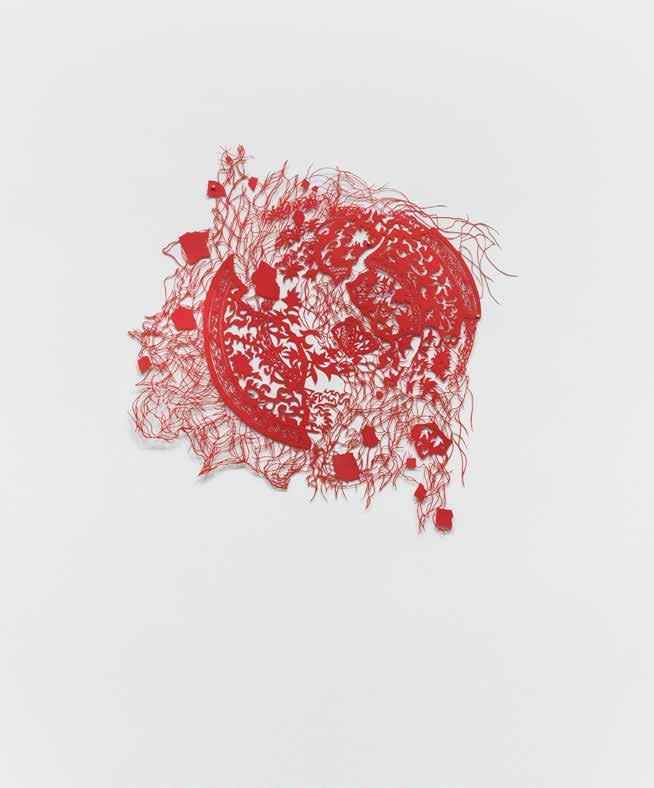

Bui creates each work from a single sheet of paper. First, with their instinctive hand, they render a composition on the page’s verso in colored pencil and marker. When the drawing is finished, the surface reveals a cartography of patterns, outlines, and silhouettes which they then incise with a scalpel until the image is revealed on the paper’s front side. With each work, the process of cutting is a means of engaging with their subject, the technical demands of the work offering them deep time to reflect on their relationships—presently or posthumously—and emulate intricacies of their kaleidoscopic lives. Each muse is settled in an interior space such as their home or studio, or an imagined landscape that incorporates details from their upbringing and heritage with natural elements—a garden of Eden of their own creation. Once the cut-out is complete, they glaze the paper with black, red, or blue paint, a palette that encourages the works to stand out from the wall and cast a phantasmagoric shadow. While Bui’s first solo show featured untreated paper, this series plays with symbolic connections to color, such as blue painted porcelain or traditional red paper cut-outs displayed for good luck during Lunar New Year. Ambitious in their scale, these works physically and conceptually hold space, portraying Bui’s monumental subjects in all of their divinity—a latticework of queer representation that celebrates their loved ones as they evolve over the course of their lives.

The exhibition is named after a verse from Franny Choi’s poem Orientalism Part I which reads: “There are many ways to hold water / without being called a vase. / To drink all the history / until it is your only song.” In their family’s native Vietnamese, the word núóc is a homonym meaning both water and country. Honoring the term’s fluidity, Bui considers how water, and by extension the ocean, is a vessel of human movement for diasporas, migrants, and refugees, referencing their own family separating from their motherland and coming to call a new country home. Like precious fragments from a shipwreck, Bui is interested in the beauty and suffering which inform a multi-conscious existence, aspiring to find a more honest dynamic between interiority and exteriority—releasing a burst of joy from the sum of their parts.

Antonius-Tín Bui describes their approach as poly-disciplinary, riffing on the refusal to be pigeonholed. “I tell people that my work is as nonbinary as myself,” they playfully observe. Their work ranges from performance to intricate portraits made from cut paper, textile to ceramics, printmaking to installation. Across everything, there is an energetic lightness and freedom in their approach. This is work that blends the politics of queerness, the Vietnamese diasporic experience, and gender fluidity with a sense of intuitive beauty and highly developed craft.

Bui was brought up in the Bronx, studied at Maryland Institute College of Art, and is based in New Haven, Connecticut. They have exhibited extensively across the United States, and more recently, their first experience in an art fair context at Independent New York with Monique Meloche. A spectrum of cut paper pieces includes representations of vessels and portraits of queer and trans Asian-Pacific and Asian-Americans they are best known for. “I’ve been more invested in exploding the figures, reassembling them, tapping into the messiness,” the artist explains. “The tensions and the trappings of visibility, especially as portraiture by queer and trans artists of color, is just more and more consumable these days.” To contrast this, Bui layers them against intricate patterns evocative of Southeast Asian motifs that emerge from lace into complex nets that trap or release the depicted figures.

The portrait pieces are based on specific people, rather than abstracted ideas. Most are figures intimate to the artist, such as friends, relatives, artists, organizers, and creatives, though historic characters and porn stars are sometimes subjects. “Regardless of my relationship to them, I think they provide me a possibility. They remind me of my identities and fluidity, expanding the contours of who I can be. Many of them have aided me in my own transition, have helped me realize how I wish to continue to evolve and express myself. They all teach me to dream bigger than I’m ever able to do individually.”

The portrait format and role of pose accidentally play with the heritage of art history. Photographs taken by the artist of their community are often the starting point for these pieces. “I really enjoy the photographic process as a performance in itself. The subjects being so vulnerable, and how it takes time to get to that moment of stillness of them feeling at ease, no longer bothered by the gaze of the camera.” A number of these works are of couples, depicted as melding into each other and at ease. A reflection of intimacy.

Even if at times drawing from photographic material, there is a surprising level of experimentation and freedom in Bui’s process, considering how intricate the results are. “I call them a nonlinear dance between drawing, improv, and

mistakes, because my hand slips quite a bit. I’ve learned just to go with the flow,” Bui enthuses. “I really am enjoying the labor of it all.” The works begin as white – and sometimes stay white, playing with shadow, silhouettes and shape. Others are painted with blue or red – referencing everything from porcelain or the American flag to the color red as a symbol of opulence in Asian culture. “I tell people I’m going through my eternal blue era right now,” Bui jokes. The blue vessel pieces often draw on extensive research on Asian objects that exist in museum collections, as well as symbolic ideas around emotion. Bui notes there is a sense of resistance to “the sexual objectification of Asian femmes, or the sexual castration of Asian men. Oftentimes, we’re denied an interiority and valued more for the objects, the culture, the historical artefacts that we’ve left behind. The blue is a reclamation of that aspect.”

Bui sees both the performance and decorative aesthetic aspects of their work as a reflection of their Vietnamese heritage. “I’m not a trained dancer whatsoever. But I did grow up in a very performative household, not only going to church every single Sunday but also altar serving frequently as well. My parents

would also have these large gatherings. And every time my uncles got really drunk, they asked all the kids to put on fashion shows. Looking back was perplexing, absurd, and beautiful”, the artist recalls. “We all created personas in preparation for the talent, runway, and interview portions.”

There is a direct eroticism in a number of recent works. The sexual content in these works is in no way accidental but is a response to Bui’s awareness of being consumed visually and perpetuating myths around Asian bodies. Rather than reinforce available sexual stereotypes, Antonius presents an alternative. Many of the characters depicted are individuals admired by or known by the artist, who approaches them with sensitivity and complexity. These works are a “monument to the qualities of community members, our divinity, but at the same time not wanting to overlook the internalized racism, body image issues, sexual shame, and challenges the AAPI community experiences in forming healthy relationships,” they explain. “Being able to explore the boundaries of my sexuality and understanding how people read me, I was thinking a lot about the emasculation of Asian men and the stereotypes portraying them as weak, feminine.”

Bui’s characters can be sexually powerful, as the work presents their muscle and skin. “I continue to portray queer and trans folks predominantly because my sense of self and embodiment has been changing so rapidly and continues to evolve. I’m obsessed with the porosity of our skin. Yes, something that is. It’s a barrier of protection, but still so fluid, and absorbs all of our environments. I’m realizing that the delineation of where body and background start and end is becoming looser.”

There is both a sense of intimate personal politics as well as large socio-political statement in Bui’s work. Yet there is nothing didactic here. This feeling of a nuance can also be seen in their performance works. Past pieces have included collective monument interventions such as their annual intervention

at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall. “Since the monument’s erection, every single non-living object that is left at the base is collected and archived by the government. People leave these objects behind as a way to remember their loved ones who had fought in the war/were lost in the war. Motorcycles, wardrobes, metals, family albums. But there’s no monument that really recognizes and tries to reconcile with the Southeast Asian perspective of the war,” Bui points out. “Me and my group, the Missing Piece Project, engage with the monument every single April 30 - which is considered the date of the end of the war. We leave objects collected by our own community members as a way to reclaim our past experiences, history, and memories. It’s been really complicated yet rewarding to dream of a monument collectively.”

In a number of the artist’s delicate cut out portraits, they depict the subject’s faces breaking, fusing portraiture and their images of vessels into a single piece in some way. It is something reflected in the title of the exhibition at Monique Meloche. The title There are many ways to hold water without being called a vase comes from Franny Choi’s poem “Orientalism Part One.” (Many of Bui’s work’s titles are also taken from poems.) Choi’s text examines the experience of being an Asian woman with a white partner and having to address the histories and complexities their bodies represent. “I’ve been thinking a lot about how Orientalism dehumanizes and exoticizes Asian cultures and continues to reduce us to caricatures and shallow generalizations,” Bui explains. “Breaking away from that requires us to see beyond those distortions, rejecting the notions that we are static and unchanging. I’m hoping to embrace this dynamic, evolving breaking. A lot of broken pieces are painted red, referencing cut paper decorations around Lunar New Year or Asian interiors.” In these works, Bui is shattering and destabilizing received stereotypes and representing them as possible sources of joy. As opposed to seeing breaking as a negative action, these are images around reconfiguration and the joy in unsettling and self-interrogation.

Bui repositions the clichés and stereotypes of Vietnam in the American and global imagination, creating work imbued with a fusion of ideas around beauty and politics. There is balance between the intimate and the public. The result is work that fragments and bursts apart expectations, that reforms the way we see the world.

The work of love becomes its own reasons, 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint 52 x 112 in 132.1 x 284.5 cm

Not everything floats. I am trying to learn which parts of me to let sink., 2022 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

92 1/2 x 60 in

235 x 152.4 cm

like the ocean, having been the ocean long before we arrived, each wave newborn and buried at once; like us, standing breathless at the edge, astonished by our own lungs., 2022

hand cut paper, ink, and paint

77 1/2 x 60 in

196.8 x 152.4 cm

A silence settles that isn’t so silent, 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint 52 x 41 in 132.1 x 104.1 cm

There are answers hiding in the white noise, in the heartbeat of a house., 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

33 1/2 x 26 in 85.1 x 66 cm

A mystery is a story. A story is a mirror. A mirror is a poem. A poem is a pattern. A pattern is repetition. Repetition is emphasis. The emphasis being the reason for repetition. Repetition is also a break in a pattern. Breaking a pattern is the reason for a poem. A poem is a mirror I use to look not at but into myself. My story. Mystery., 2023 hand cut paper, ink and paint

32 x 22 in 81.3 x 55.9 cm

If the stars have, as they say, been dead for millions of years by the time their light reaches us, then it follows that my retinas are a truer thing to call sky., 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

29 3/4 x 24 1/2 in

75.6 x 62.2 cm

There are many ways to hold water without being called a vase. To drink all the history until it is your only song., 2022 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

86 x 42 in

218.4 x 106.7 cm

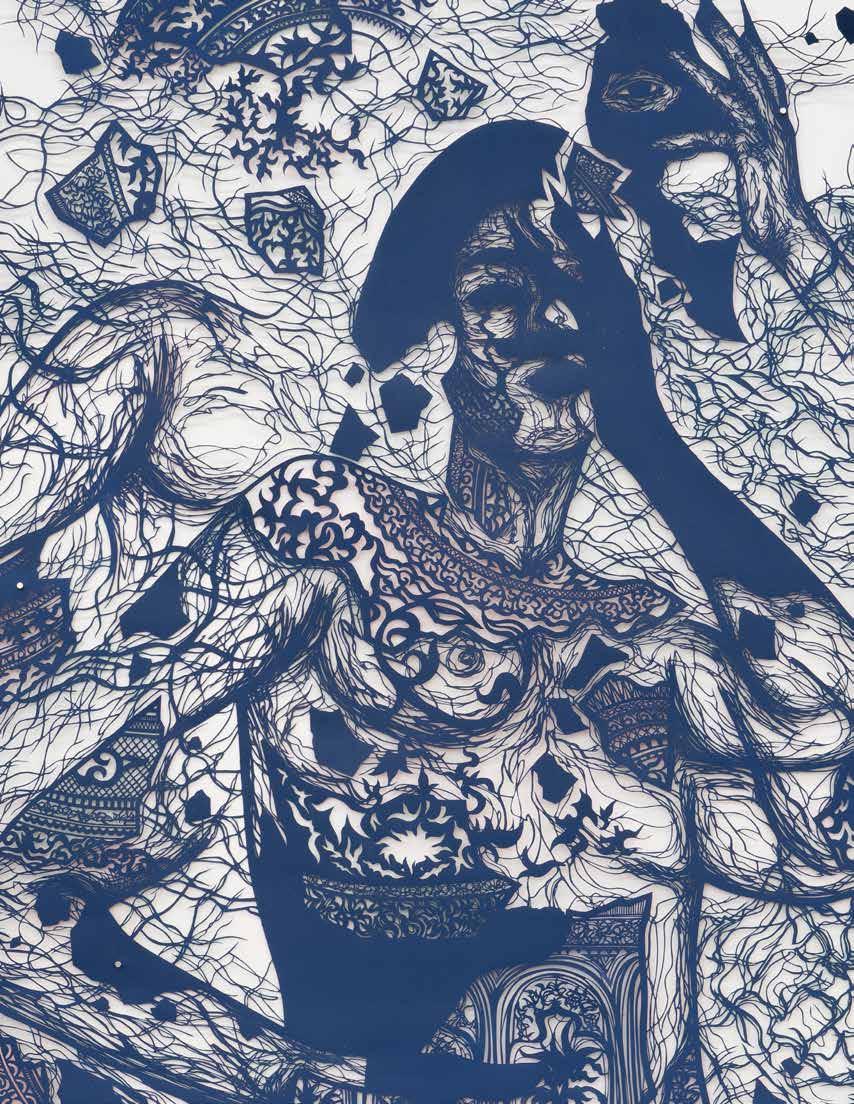

Body called itself Master. Body named itself Free. Body bought its own freedom. Body sold itself to the top. Body broken glass all by itself. Body spills all the light. Body all the light. Body only dark when it wants to be., 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

80 x 42 in

203.2 x 106.7 cm

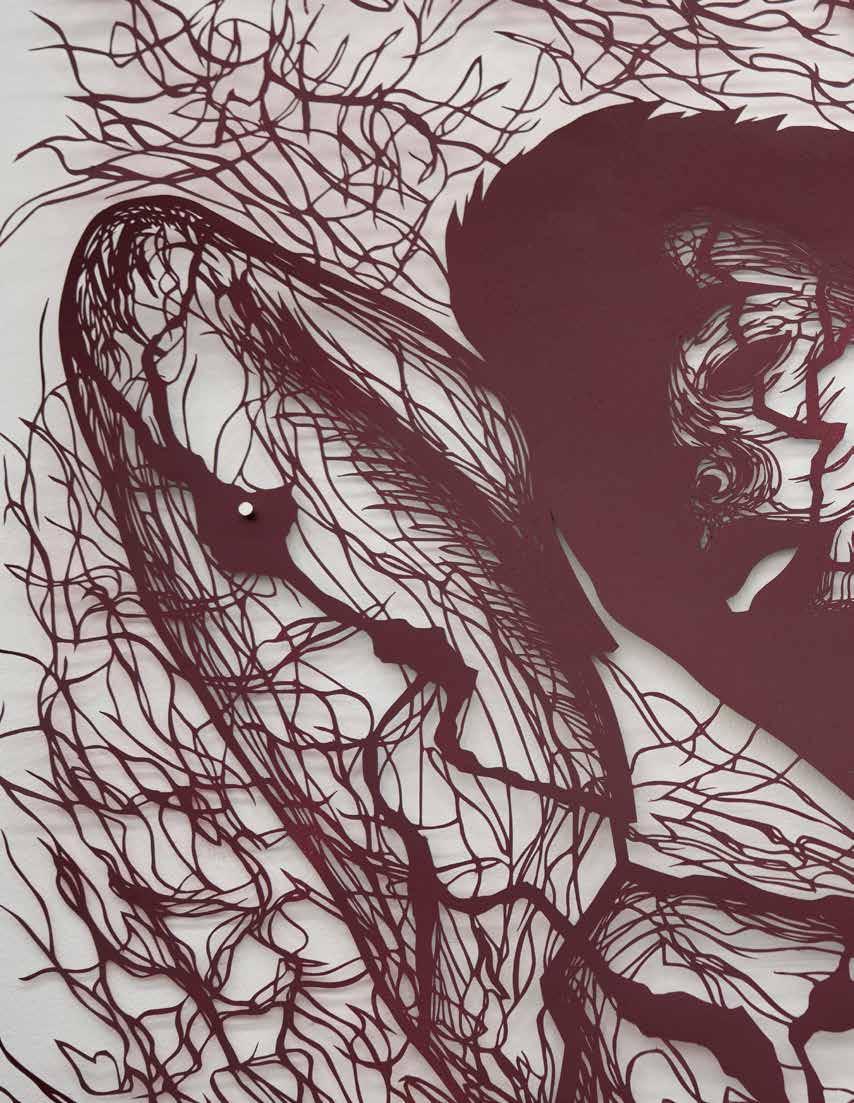

Mending in a daybreak that casts every shadows except your own, 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

83 x 42 in

210.8 x 106.7 cm

Because I stopped apologizing into visibility. Because this body is my last address. Because this mess I made I made with love. Because only music rhymes with music. Because I made a promise., 2022 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

83 x 42 in

210.8 x 106.7 cm

Silent & unkissed - that’s how I wanted you to suffer, too, boy who wouldn’t look at me. Seeing you run so beautifully on the track that afternoon, I wanted you to suffocate, breath-starved from all the miles you’d run away from me., 2022 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

80 x 42 in

203.2 x 106.7 cm

In Between Deaths, 2022 hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

31 1/2 x 27 1/2 in 80 x 69.8 cm

There’s Nothing Left Here for You, 2022 hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

33 1/2 x 32 in

85.1 x 81.3 cm

Antonius-Tín Bui (b.1992, Bronx, NY) (they/ them) received their BFA from Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, MD (2016). Bui has had recent solo exhibitions at moniquemeloche, Chicago, IL (2021), Hudson D. Walker Gallery, Provincetown, MA (2020), and Laband Art Gallery, LMU, Los Angeles, CA (2019); Lawndale Art Center, Houston, TX (2018). Bui’s work has recently been included in exhibitions at the Wende Museum, Culver City, CA (2023); Artspace, New Haven, CT (2022); Arlington Art Center, Arlington, VA (2022); Orange County Center for Contemporary Art, Sacramento, CA (2022); the McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX (2022); Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, New York, NY (2022); USC Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena, CA (2021); Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, Houston, TX (2020); Blaffer Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, TX (2019); and National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C. (2019).

Their artwork is in public collections including the Eaton Workshop, Washington D.C.; Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, Little Rock, AR; Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington D.C.; and the Pennsylvania College of Art & Design, Lancaster, PA. They are a recipient of The Outwin Boochever Prize (2021) and MICA Alumni Grant (2018). Bui is a fellow of the 2022 Queer|Art|Mentorship program, and has received additional fellowships from James Castle House, Boise, ID (2022); Kimmel Nelson Center for the Arts, Nebraska City, NE (2022); Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown, MA (2019); Yaddo, Saratoga Springs, NY (2019); The Growlery, San Francisco, CA (2019); and Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, Houston, TX (2018). Bui lives and works in New Haven, CT.

Francesca Gavin is a curator and writer based in London. The Editor in Chief of EPOCH review, a contributing editor at The Financial Times HTSI, Twin and Beauty Papers and a regular contributor to publications including Frieze, Cura, and Kaleidoscope. Gavin was the co-curator of the Historical Exhibition of Manifesta11 and is the author of ten books. She has a monthly radio show Rough Version on NTS Radio on art and music.

Not everything floats. I am trying to learn which parts of me to let sink., 2022 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

92 1/2 x 60 in 235 x 152.4 cm

The work of love becomes its own reasons, 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

52 x 112 in

132.1 x 284.5 cm

A silence settles that isn’t so silent, 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

52 x 41 in

132.1 x 104.1 cm

Like the ocean, having been the ocean long before we arrived, each wave newborn and buried at once; like us, standing breathless at the edge, astonished by our own lungs., 2022 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

77 1/2 x 60 in

196.8 x 152.4 cm

There are many ways to hold water without being called a vase. To drink all the history until it is your only song., 2022 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

86 x 42 in 218.4 x 106.7 cm

There’s Nothing Left Here for You, 2022 hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

33 1/2 x 32 in

85.1 x 81.3 cm

Mending in a daybreak that casts every shadows except your own, 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

83 x 42 in

210.8 x 106.7 cm

In Between Deaths, 2022 hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

31 1/2 x 27 1/2 in 80 x 69.8 cm

Body called itself Master. Body named itself Free. Body bought its own freedom. Body sold itself to the top. Body broken glass all by itself. Body spills all the light. Body all the light. Body only dark when it wants to be., 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

80 x 42 in 203.2 x 106.7 cm

A mystery is a story. A story is a mirror. A mirror is a poem. A poem is a pattern. A pattern is repetition. Repetition is emphasis. The emphasis being the reason for repetition. Repetition is also a break in a pattern. Breaking a pattern is the reason for a poem. A poem is a mirror I use to look not at but into myself. My story. Mystery., 2023 hand cut paper, ink and paint

32 x 22 in 81.3 x 55.9 cm

Silent & unkissed - that’s how I wanted you to suffer, too, boy who wouldn’t look at me. Seeing you run so beautifully on the track that afternoon, I wanted you to suffocate, breath-starved from all the miles you’d run away from me., 2022 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

80 x 42 in 203.2 x 106.7 cm

Because I stopped apologizing into visibility. Because this body is my last address. Because this mess I made I made with love. Because only music rhymes with music. Because I made a promise., 2022 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

83 x 42 in 210.8 x 106.7 cm

There are answers hiding in the white noise, in the heartbeat of a house., 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

33 1/2 x 26 in 85.1 x 66 cm

If the stars have, as they say, been dead for millions of years by the time their light reaches us, then it follows that my retinas are a truer thing to call sky., 2023 hand cut paper, ink, and paint

29 3/4 x 24 1/2 in 75.6 x 62.2 cm

Monique Meloche Gallery is located at 451 N Paulina Street, Chicago, IL 60622

For additional info, visit moniquemeloche.com or email info@moniquemeloche.com