the MOMus magazine

No 3 ---- Q3 2025

No 3 ---- Q3 2025

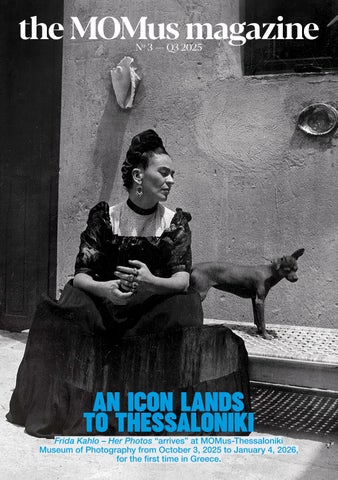

Frida Kahlo – Her Photos “arrives” at MOMus-Thessaloniki Museum of Photography from October 3, 2025 to January 4, 2026, for the first time in Greece.

To the MOMus

COVER CREDITS

Frida Kahlo with xoloitzcuintle dog in the Blue House, by Lola Álvarez Bravo, ca. 1944. Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Archives

An exhibition by:

Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Archives. Bank of Mexico, Fiduciary in the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museum Trust

The MOMus Magazine is a quarterly publication available free of charge at MOMus museums in Thessaloniki and Athens, as well as at selected distribution points and online. Any reproduction, redistribution, or adaptation of the magazine’s content, whether in full, in part, summarized, paraphrased, or otherwise rendered by mechanical, electronic, photocopying, or recording methods is strictly prohibited without prior written consent from the publisher, in accordance with Law 2121/1993 and applicable international legal provisions in Greece.

This is a somewhat unusual editorial for me. When I began writing it, just before the end of this administration’s term, I felt a strong urge to reflect on our accomplishments and feel considerable pride in all we’ve achieved. Yet, much of this success is thanks to the support of individuals, organizations, and companies that stood next to us because they believed in our vision and goals. They became committed partners in our efforts to establish MOMus as a real cultural reference point.

I won’t attempt to name everyone. The circle of MOMus’ friends has grown wide. But I would like to extend my sincerest gratitude to a few who have supported us consistently and meaningfully. To Aegean Airlines, that not only carries our art across the globe but also hosts this publication in its lounges, offering us the chance to share its brilliance. To Deloitte, for showing us how corporate social responsibility can be both impactful and engaging, and Eurobank, whose support substantially strengthens our museums’ curation and artistic programming. To water supply and sewerage company EYATH S.A., whose initiatives set the benchmark for sustainable development and environmental responsibility. To the Ioannis Latsis Foundation, for backing, on the ground, our initiative to offer art as a source of comfort and hope to oncology patients and their loved ones. And to Zoe Papageorgiou, a low key yet loyal ally in our strategic planning, who has stood by us with dedication over the years. To each of you, I offer my heartfelt appreciation.

As with all global cultural institutions, our needs continue to grow. Private sponsorships are increasingly essential in meeting the demands of our time. That’s why I encourage you all to reach out to me directly so that together, we can explore new and creative ways to sustain and expand the work of MOMus.

In closing, I want to focus on something really important. A true cultural landmark for us, the city, and a gentle reminder of the role of a large state museum. It isn’t, nor should it be to promote new artists or directly display local productions. Artists develop, experiment, and mature outside institutional frameworks, in independent spaces, workshops, and through creative dialogue with society.

When the occasion calls, it’s our duty, through historical awareness and accountability, to select artistic voices that deserve to be heard and documented for future generations. Accordingly, MOMus has the honor and privilege of hosting the world-renowned Costakis Collection, and bears the responsibility of presenting works of such scale; works that converse with global art history and constitute essential points of reference for the culture of the future.

The upcoming Frida Kahlo exhibition, opening this October at the MOMus–Museum of Photography, marks one such defining moment. Kahlo is far more than a celebrated artist. She is perhaps the most influential contemporary figure, a global icon of resilience, identity, and feminist expression. The exhibition Frida Kahlo – Her Photos, presented in partnership with the Frida Kahlo Museum Casa Azul in Mexico, is of the kind that is not readily importable into Greece. We are confident the public will warmly embrace it, and that it will become a cultural landmark for the city. We look forward to welcoming you and sharing this exceptional experience together. n

MOMus president

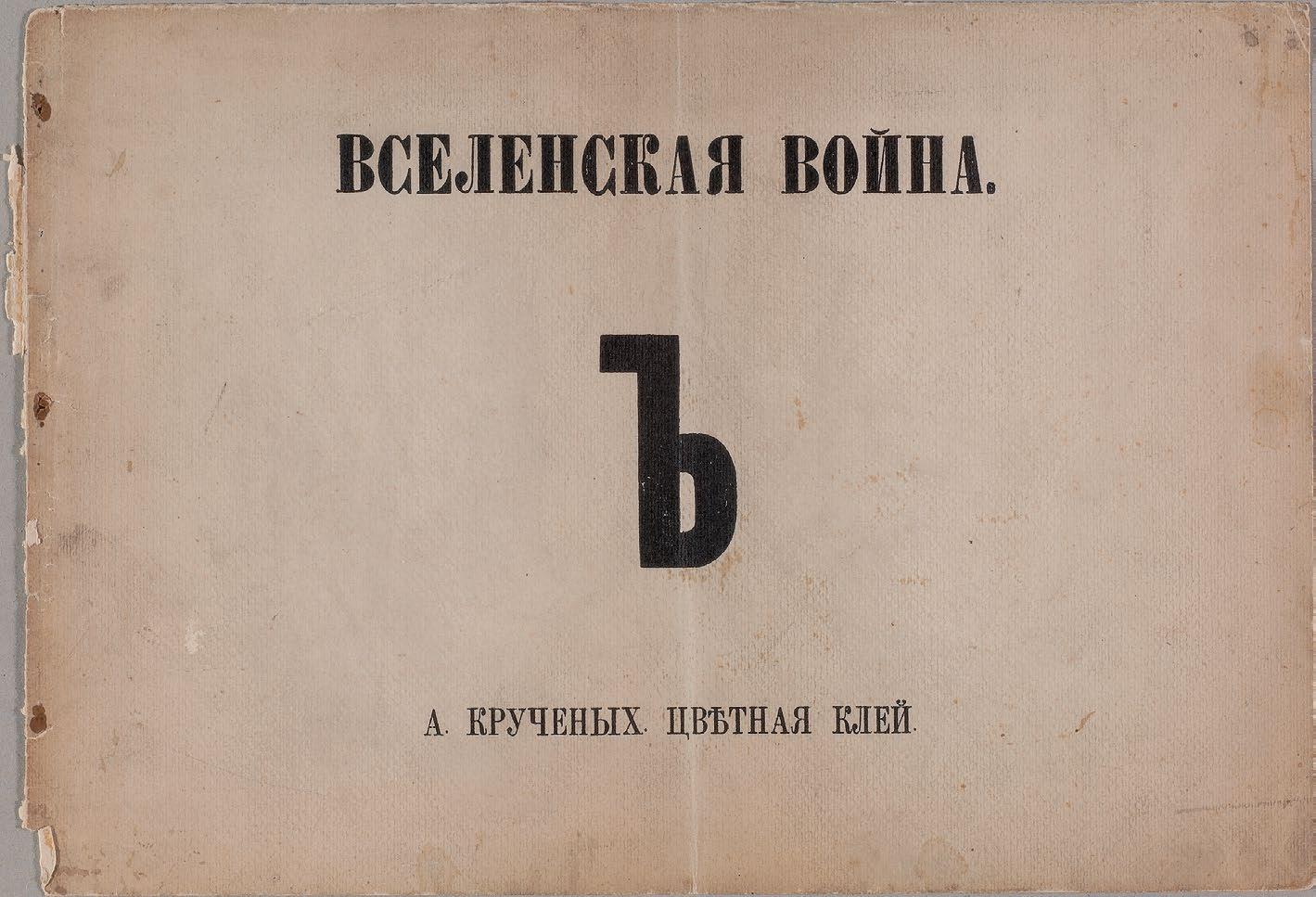

The timeless condemnation of war and the power that art has to always express the unspeakable in a revealing way and, at the same time, to give hope and function as a field of creation and survival in the darkest periods are just some of the semiotic bases of the exhibition “Universal War. The artistic Avant-garde on the World War I front. Works from the Costakis Collection” which is presented from June 15th to October 25th, 2025 at MOMus-Museum of Modern Art, at the Moni Lazariston, in Thessaloniki.

On the occasion of the 111th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, the exhibition covers the period from 1914 to 1918 and explores how Avant-garde artists in Russia, responded to the greatest war in human history and its escalating outcomes until 1920.

The “Great War” was largely perceived as the final act of the Old World. World War I in the Russian Empire, as in the rest of the world, abruptly disrupted the flow of history and caused a rupture in artistic consciousness, especially in the philosophy of the avant-gardists of all forms of art. At the same time, while there were critical concerns and fear over the devastating consequences for life and the economy, artists of that time were seized by a revolutionary mentality that did not fear breaking with the past. Great samples of this artistic renaissance were artistic movements such as Cubo-Futurism, Suprematism, the early Constructivism of Tatlin, and its influence on the Dadaists were born; irrational poetic writing and atonal music also developed.

From the satirical images of 1914 to the transrational writing of Aleksei Kruchenykh and the non-objective art of Kazimir Malevich, Liubov Popova, Ivan Kliun, and others, and from the mystical writings of Velimir Khlebnikov and Pavel Filonov, aimed at exorcising war, to the tragic figures of amputee soldiers portrayed by Solomon Nikritin, the exhibition emphasizes the apocalyptic nature of the war and conveys strong anti-militarist messages.

As an epilogue to the exhibition, the work “Seeing Against Seeing” by the photographer and researcher Alexey Yurenev is presented. It is the result of a dialogue between Ernst Friedrich’s 1924 anti-war manifesto “War Against War!” –in which he compiled graphic photographs of World War I’s aftermath to expose its brutality– along with thousands of portraits from World War II era. Artificial Intelligence (AI) trained to be fault evoke timeless portraits of war violence and evidence of the psychological terror it causes.

Curated by: Maria Tsantsanoglou, artistic director, MOMus-Museum of Modern Art-Costakis Collection. Assistant curator: Angeliki Charistou, art historian, MOMus curator. n

WHERE & WHEN: At MOMus-Museum of Modern Art-Costakis Collection (Moni Lazariston, Thessaloniki) until October 25th, 2025. Before your visit, please check the MOMus website (www.momus.gr) for latest updates.

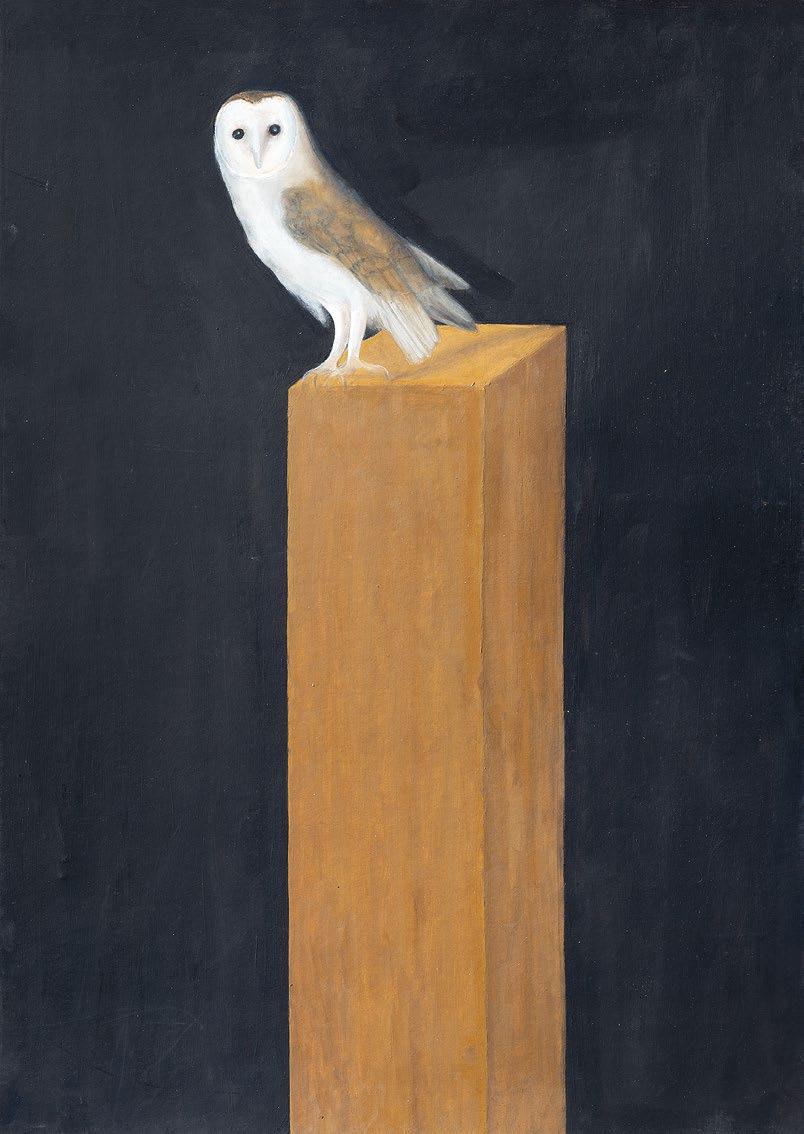

Above and below: Aleksei Kruchenykh (b. Olevka 1886 – d. Moscow 1968), in collaboration with Olga Rozanova (b. Melenki 1886 – d. Moscow, 1918). Universal war, 1916. Four printed pages and 11 paper and fabric collages on paper, 22 x 33 cm each.

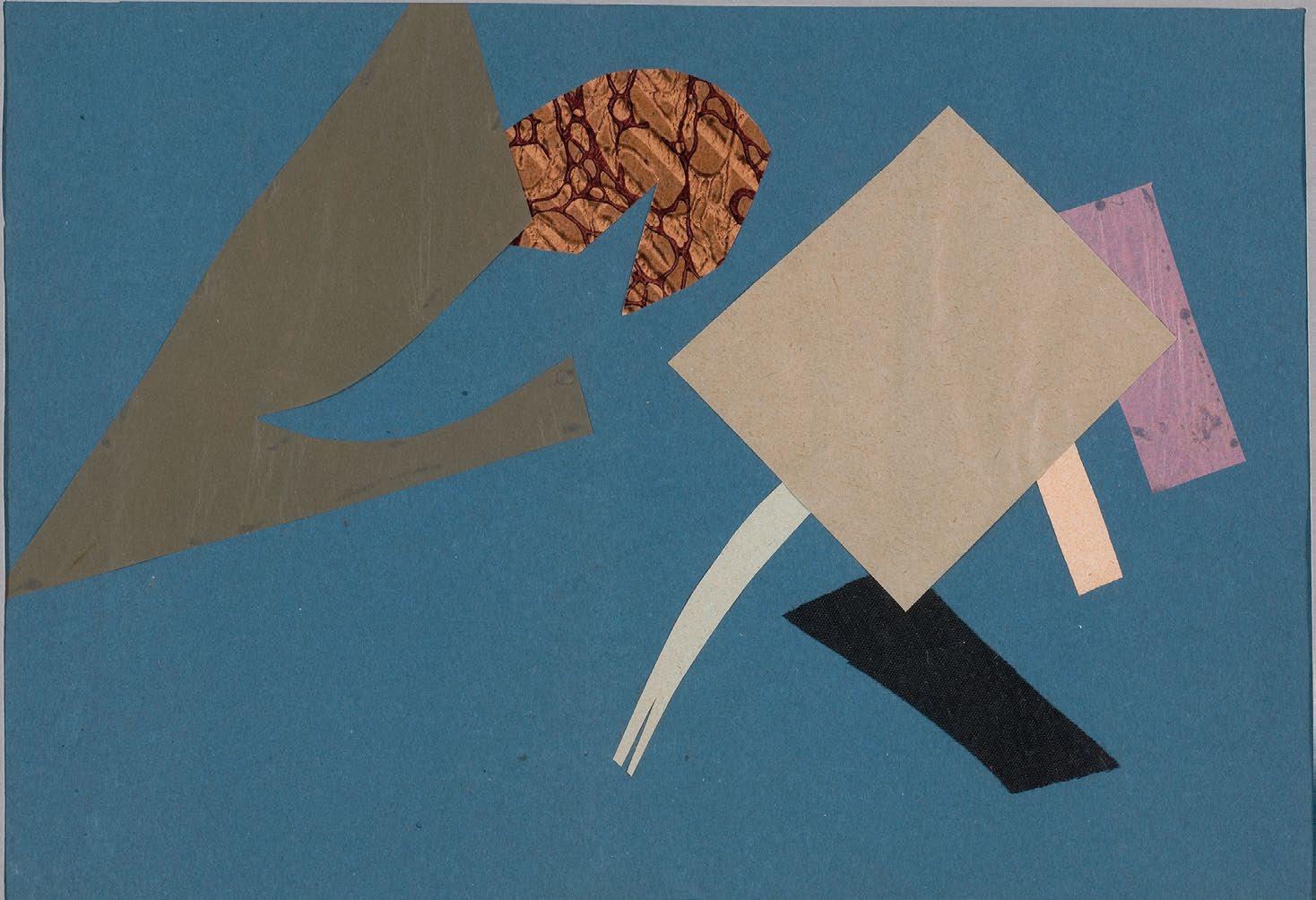

Acknowledging that the keenest observers of the world are either painters and artists, or scientists, the exhibition “The king is naked” puts the quote from Andersen’s well-known fairy tale at its center, identifying the acclaimed painters Vasilis Vasilakakis, Vangelis Gokas, and Ilias Papailiakis as its core protagonists.

In an age obsessed with images yet intent on merely skimming through them, three painters have chosen to observe the world from a state of stillness – not in reaction, but in reverence to the image. Vasilis Vasilakakis (b. 1968), Vangelis Gokas (b. 1969), and Ilias Papailiakis (b. 1970) present their work in a single exhibition, pursuing an artistic dialogue that allows a conversation of textures, deep shadows, and colors, bringing together three leading figures of contemporary Greek painting, united, yet distinct. Each has pursued his own path, yet all share a common denominator: a devotion to painting as a spiritual practice as well as a deeply philosophical endeavor.

The exhibition is, therefore, an attempt to stage a quiet rebellion of painting, against those who repeatedly proclaim its demise, only to be refuted time and again, and in celebration of its unique power to conjure new images and represent things that always escape our initial gaze.

Curated by: Yannis Bolis, Areti Leopoulou, art historians, MOMus curators. n

(λεπτομέρεια).

Vasilis Vasilakakis, “Owl mourning over the ruins”, 2024-2025. Oil on cardboard, 35 x 400 cm (detail).

Photography: Stratos Kalafatis.

WHERE & WHEN: At MOMus-Museum of Contemporary Art (TIF-Helexpo premises, Thessaloniki) until September 14th, 2025. Before your visit, please check the MOMus website (www.momus.gr) for latest updates.

Ilias Papailiakis, “My heartbeat on the opposite shore”, 2024. Oil on canvas, 400 x 1.000 cm.

Crux Galerie. Vangelis Gokas, “The hand”, 2011. Oil on canvas, 50 x 70 cm. Courtesy: Crux Galerie.

Katerina Keleki has been greeting thousands of visitors at the MOMus Museum of Contemporary Art for over two decades. From daily interactions with guests, and its permanent and temporary collections, her role as the museum’s receptionist is interesting and interactive.

I’m from Thessaloniki, born right here in the city’s center. In 2004, I started working at what was then the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art. It was my first job. It was February. But I still remember the warm welcome I received from my colleagues. At the time, the museum was closed to the public as temporary exhibitions were being set up. Time’s flown since then and the space’s function has changed significantly, especially after the gift shop’s recent renovation. Also, when I started, many tasks were done manually; today, most have been digitized. My role has grown as well. I not only handle logistical matters. I have other responsibilities and I’m given room to take personal initiative.

I studied Computer Science, specializing in Networks, at a public vocational school, and I’ve always enjoyed working with technology and online in general. My job at the museum, while different, is equally engaging. I supervise the exhibition spaces, assist with events, and support visits from schools and various groups. Through my role, I’ve gained a strong understanding of how a cultural organization operates and was able to grow professionally. I usually get to work by bus. Sometimes my husband drops me off, or I carpool with a colleague who lives near me. I like listening to music, watching classic Greek films, and I love volleyball. I’ve played on teams for many years.

Among the items in our gift shop, the collectible ceramics by Alexis Akrithakis and the beautiful silk scarves featuring iconic works from the collection to me personally, stand out the most. I appreciate how these pieces can bring a part of the museum experience into visitors’ homes.

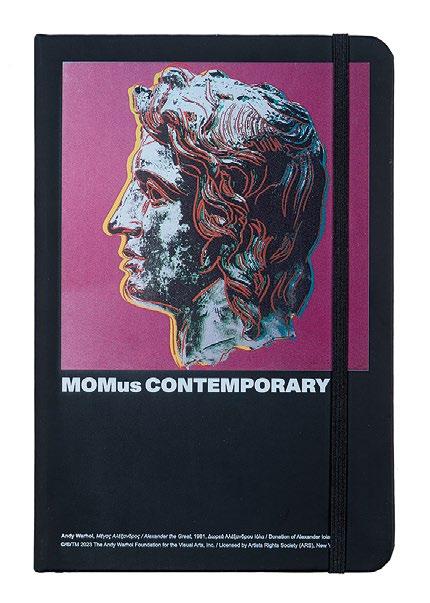

My favorite exhibit is Andy Warhol’s Alexander the Great. It captivates me because it shows how art can take materials from antiquity and transform them into something contemporary. Through the recurring presence and dominance of this image, I see both a prediction of today’s digital world and a strong connection between art and technology. This relationship inspires me profoundly. I’m also moved by the reactions of children when they visit the museum. Once, during an educational game, a child raised his hand and commented “This looks like Instagram filters” referring to Warhol’s piece. It was such a sharp observation and reminded me how children, with their fresh perspective, make remarkable connections. The greatest joy I find in my work comes from the satisfaction on visitors’ faces. There is nothing more beautiful than hearing visitors, adults or children, engage with a piece, ask questions, and feel inspired. I also love when they come to the shop to buy gifts, wanting to deepen their connection with the museum. It’s the constant interaction with visitors and colleagues that keeps the work alive. It never grows dull or repetitive.

Finally, I’m a big fan of football team PAOK. If this team were an artistic movement, then surrealism would be the perfect fit. Just as surrealism defies logic, football team PAOK follows no predictable path. From astonishing victories to dramatic defeats, it constantly transcends common sense. Surrealism also puts forward emotion and the unconscious, similarly to the Toumba Stadium, which releases a kind of energy one only feels with their heart. If that isn’t surrealism, then what is? n

“There is NOTHING MORE BEAUTIFUL than hearing VISITORS engage with a piece, ask questions, and feel INSPIRED.”

Zoe Psarra Papageorgiou, member of the Board of Directors of the Papageorgiou Foundation, shares her favorite exhibits from the permanent collections of MOMus, recalls the moment when art advocate Maro Lagia presented her vision for the museum’s establishment to former Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis, and discusses the role of culture in Thessaloniki in today’s world, a cause she continues to actively support.

Let’s get straight to it: which is your favorite exhibit from the MOMus permanent collections and why?

I could spend hours wandering through the permanent collections, but my heart always returns to the works of Takis particularly his Signals. There’s something about their enigmatic silence that captivates me, as if they pulse with a hidden energy, communicating with the invisible. I also need to mention the Lens and the iconic sculpture at the entrance: Zongolopoulos’s Umbrellas. Every time, it invites you to pause, to engage, to see it differently.

Is there an exhibition that stands out most vividly to you?

Zoe Psarra Papageorgiou, Board Member of the Papageorgiou Foundation.

A few days ago, I visited the exhibition The King is Naked, which left me with the best impressions. Vasilis Vasilakakis, Vangelis Gokas, and Ilias Papailiakis joined forces in a sincere, shared dialogue about the essence of the image in today’s era.

Can you share a story from MOMus that you’ll never forget?

I’ll re-mention art advocate Maro Lagia, the woman who, with her struggles and unquenchable passion, sparked the birth of Greece’s first museum of contemporary art. After the 1978 earthquake, at an event in Palataki, she shared her vision with Konstantinos Karamanlis, who replied ironically, “I’ll give you a penny if he gives you a single piece.” The former Prime Minister was referring to artist Alexander Iolas, Maro’s

good friend, whom she had met at the Zoumboulakis Gallery. However, Iolas, witnessing the moment, reacted and in 1984 gifted his friend and the Macedonian Center for Contemporary Art ten works by Takis, which he had acquired by exchanging five Picassos.

With Maro’s determination and a dedicated group of art lovers by her side, a museum was created that breathed new life into Thessaloniki, proving that the impossible is possible. Recently, this story became better known when Maro Lagia was honored for her contribution.

After the pandemic, MOMus significantly strengthened its outward outlook by opening its spaces and organizing various events. How do you view the modern role of museums?

Absolutely in tune with the way MOMus has chosen to operate. You see, the true role of a museum is measured by how active it is within its society and how effectively it opens itself up to new horizons. Every museum is a living organism, which is why it must constantly evolve and promote cultural development from every angle. It should be both of its time and ahead of it, instead of a mere custodian. It needs to stand out as an inspirer, a destination for thought and emotion. A place that is open, accessible, and polyphonic.

At its core, the contemporary role of a museum is deeply anthropocentric, strikes a chord and co-shapes the future even when that future is contradictory, complex, or difficult to interpret. That is why I deeply appreciate MOMus’s refusal to become complacent and its commitment to investing in the future.

What more do you expect from MOMus? What would you like to see happen?

What I hope and expect is that it will continue to operate with the same consistency and imagination as a dynamic cultural hub and as an organization that listens to society’s needs and responds with boldness, quality, and inclusion. To maintain its momentum in public discourse, to strengthen cooperation with new voices and remain outward looking. To surprise, provoke emotions, and offer space for both reflection and action.

How do you assess the level of cultural production in Thessaloniki today? Are there areas where it particularly stands out?

We all know that the multiculturalism of our city is what gives it extraordinary interest. As a crossroads of cultures, it has a cultural heritage that sets it apart and continues to fuel its contemporary artistic production.

In recent years, I have witnessed praiseworthy activity: festivals, initiatives by young artists, and dynamic institutions unafraid to experiment. There is talent, enthusiasm, and, above all, the unique artistic energy of a city that unites cultures.

And a completely personal question which I saved for last. We know the Papageorgiou Foundation supports culture in general and MOMus in particular. What is your objective?

Our objective at the Papageorgiou Foundation is multi-layered. Specifically in the field of culture, we actively contribute to and support society’s development, viewing it as a cornerstone of every modern city. Through our partnership with MOMus, we aim to highlight Thessaloniki’s potential, promoting a city open to all its people’s voices. For us, culture is both a bridge that unites the individual and the collective and a tool to co-shape a better tomorrow. n

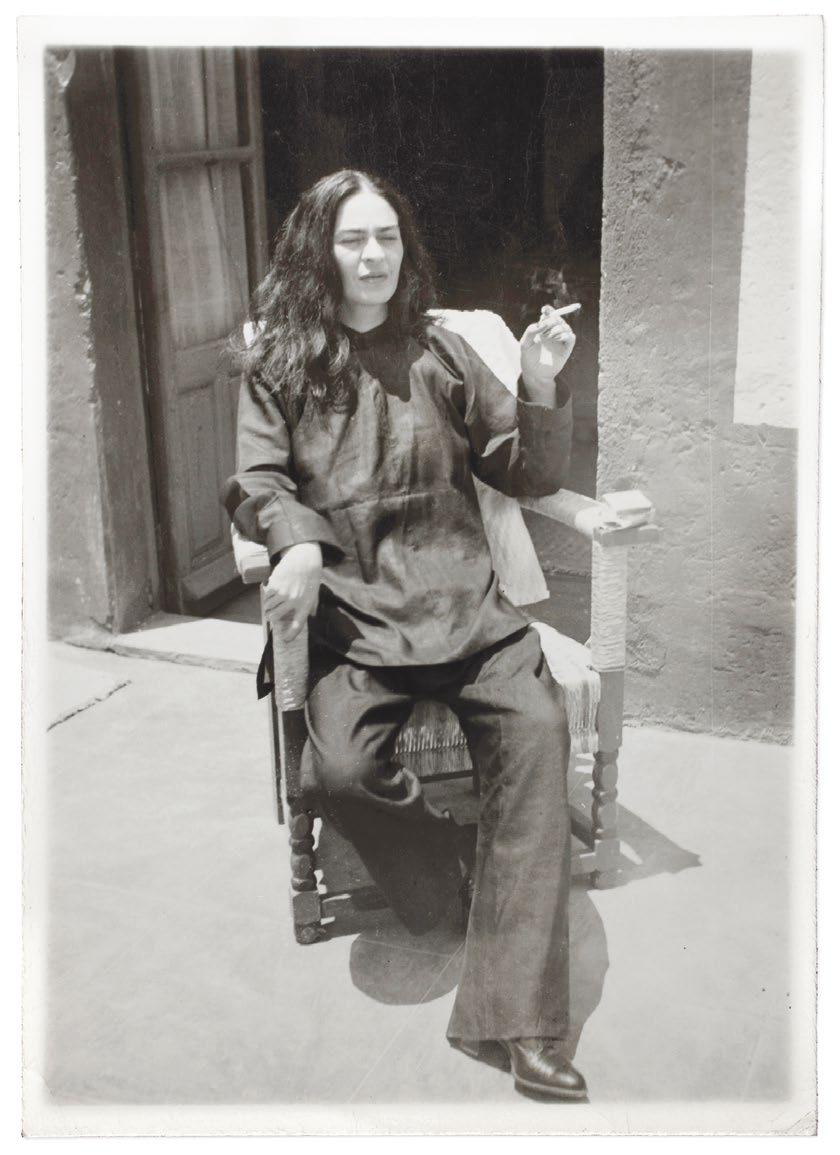

Frida Kahlo “arrives” at MOMus-Thessaloniki Museum of Photography from October 3, 2025 to January 4, 2026, for the first time in Greece, as the next stop in the list of more than twenty cities where the exhibition Frida Kahlo – Her Photos has been presented internationally.

AN EXHIBITION BY:

The exhibition reveals the intimacy of the great Mexican artist and offers a new perspective on the turbulent life of one of the most mysterious and emblematic figures of Latin-American art.

Despite the importance of photography to Frida, a major part of her collection of photographs was hidden away from the public for several decades. When she died, in 1954, her husband, Diego Rivera, donated their house –known as the Blue House, in Mexico City– to the Mexican people, so that they could turn it into a museum about Frida’s life and work. This was the beginning of what is nowadays the Frida Kahlo

Museum, one of the most popular museums in the world.

Although Diego gave Frida’s artworks and objects to the museum, he asked to lock a part of them away from people’s curious eyes. That is the main reason why this personal archive, which included more than six thousand photographs, some drawings, letters, medicines and clothes, was closed for five long decades. A Blue House’s bathroom was the chosen place to save those treasures, and therefore gained an almost mythical aura.

It was only in 2003 that the numbed archive was opened. A selected part of the newly found photographs was transformed into this exhibition, curated by Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, a well-known Mexican photographer and historian of photography in Mexico. Frida Kahlo – Her Photos exhibition shows 241 unpublished photographs that represent diverse periods and people in Frida’s life and which were also objects of her personal affection.

It was only with the discovery of Frida Kahlo’s photographic archive that it became evident that the origins of many of her charismatic works lie in photographic composition. Her self-portraits, for example, were highly inspired by the portraits her father took of himself. Pablo Ortiz Monasterio adds that the collection of photographs itself, the way it has been grouped and worked on, constructs a portrait of Frida. Consciously or not, through an immense diversity of photographs, carefully kept, cherished and intervened, the artist reveals the complex fragmentation of her own identity. n

Επάνω,

Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Archives.

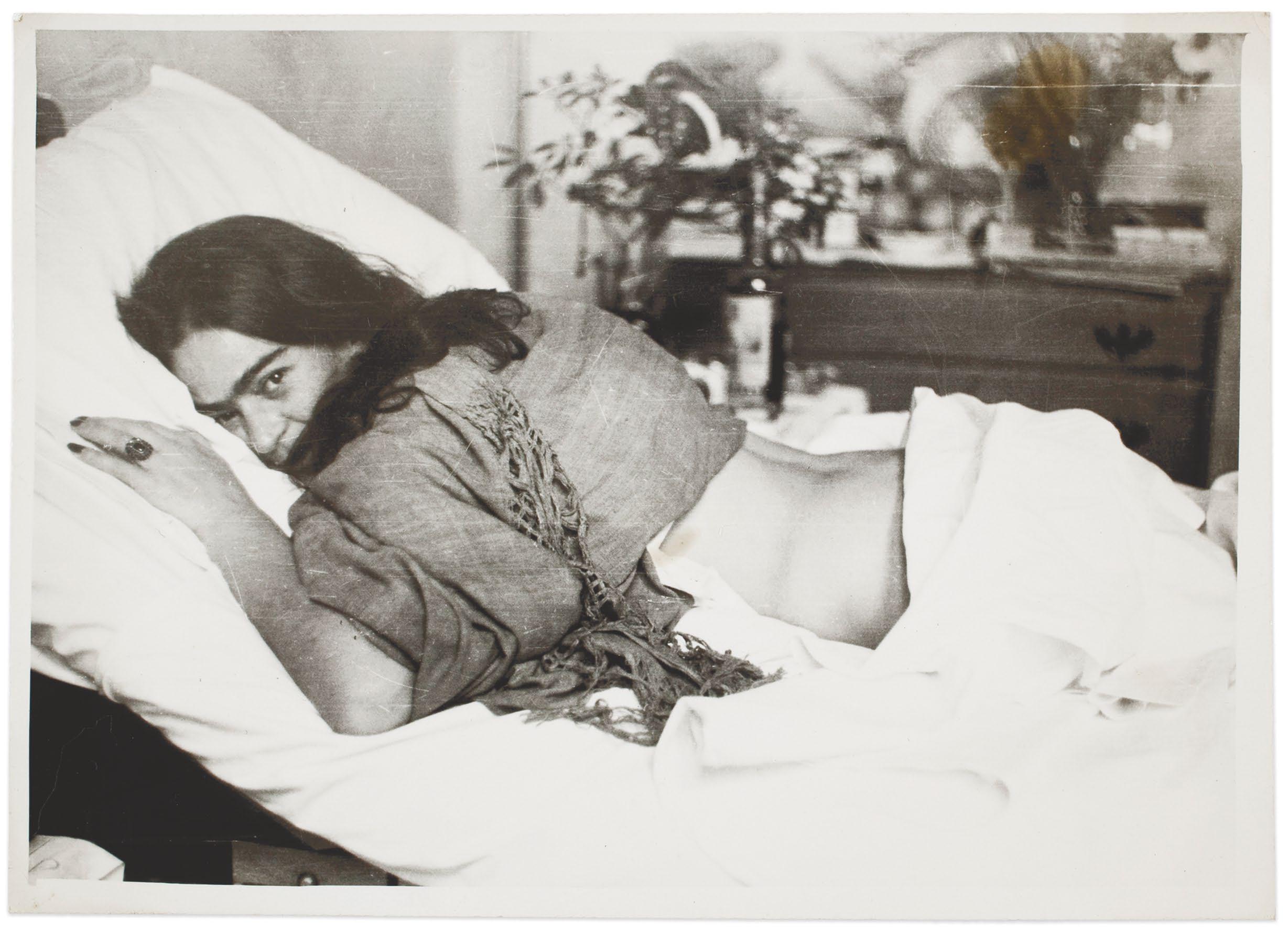

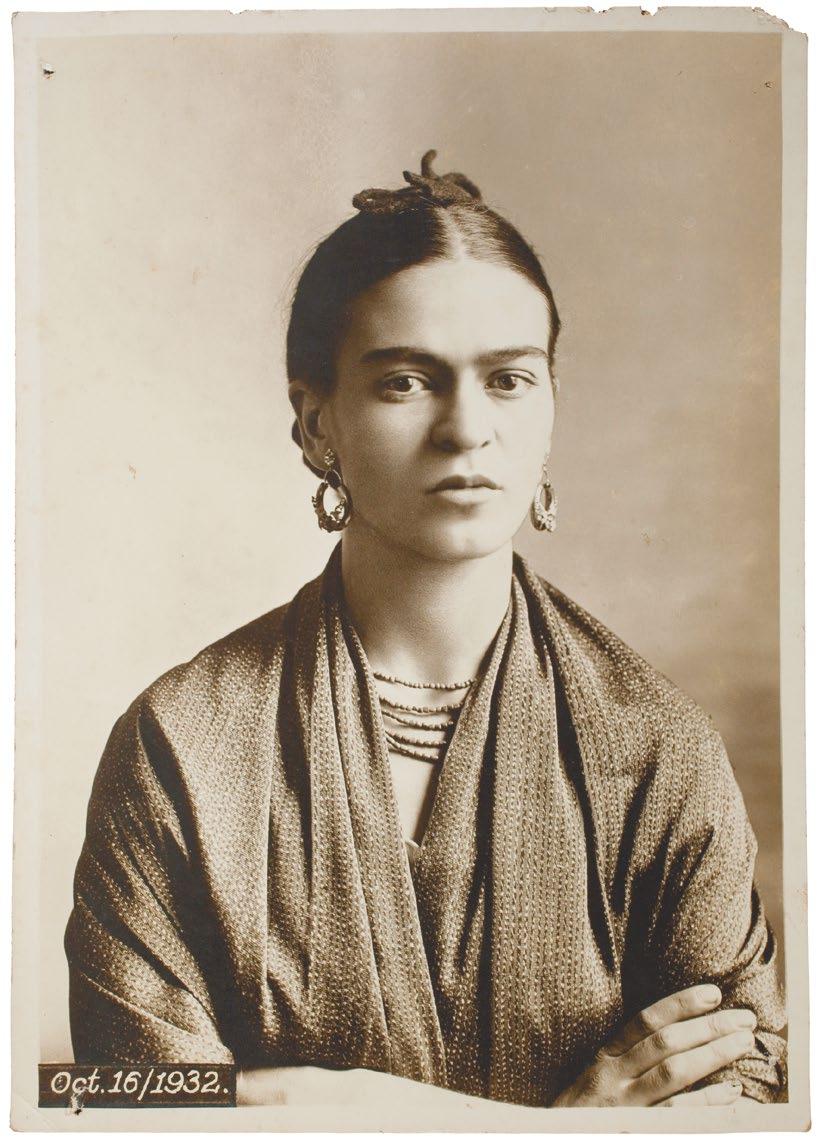

Above, on the left:

Frida Kahlo, by Guillermo Kahlo, 1932.

Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Archives.

Επάνω, δεξιά:

Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Archives.

Above, on the right: Frida Kahlo after an operation, by Antonio Kahlo, 1946.

Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Archives.

1946.

Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Archives.

On the right:

Frida Kahlo with the doctor Juan Farill, by Gisèle Freund, 1951.

Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Archives.

An interview with Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, curator of the Frida Kahlo – Her Photos exhibition, uncovers new perspectives on Frida Kahlo’s life, personality, and artistry. Through meticulous curation and deep engagement with the photos, Pablo reveals how Frida’s personal narrative is crafted, highlighting her resilience, complexity, and the intimate story behind her public image.

Papadimitriou

Could you explain your approach to working with Frida Kahlo’s photographic archive? How did you select the images and create a narrative around her life? It was more a process of listening and observing, really letting the archive –the group of photos– stand out on its own. Then, we started building “islands” or thematic groups. For example, Guillermo Kahlo, Frida’s father, is part of the origins and his importance helped clarify why Frida painted as she did. We published all the self-portraits we could find, which became a chapter distinct from the “Origins,” though her father is present there too. Essentially, it felt like Frida was “speaking” through the photos, and we were just “reading” her world –her desires, failures, and achievements– and translating that into a book and an exhibition. I could speak for days on this; I became obsessed.

From the thousands of photos in the archive, how many did Frida take herself? Surprisingly, she only signed five photographs herself. Four were clearly signed by her, and there’s one sent to Diego Rivera with a note on the back about a dog she was dreaming with him. That makes five confirmed photos taken by Frida. The rest are by other photographers

– but, collectively, these images offer an incredible insight into her life.

Did the photos reveal anything about Frida’s sexuality or relationships? Were there any explicit or suggestive images? There weren’t explicit sexual photos, but there were subtle clues. For instance, there is a photo where lips are printed on glass – possibly Frida kissing someone, but we don’t know who. She also had close female friends she referred to as “Las del sindicato,” meaning “girls from the union,” indicating she was open about her affection for women. Editorially, we included a photo of Frida napping with a friend, which isn’t sexual, but could suggest intimacy. So, yes: she was daring, but I didn’t find anything compromising or scandalous in the archive.

How much do you think your own perspective shaped the narrative around Frida in the book and exhibition? There is always some authorship when you curate an archive; you decide what to include and what to leave out. But we always kept Frida at the center, not me. People don’t read photographic books like literature; they look at images, compare, and interpret. We tried to select photos that expressed her biography, her personality, and her way of organizing her own life story. We also collaborated with other experts to include their perspectives. So, yes: my view is there, but it’s a collective effort aiming to reveal Frida authentically.

You mentioned Frida altered some facts about her life. Could you give us some examples of how she shaped her own biography? One example is her birthyear. In reality, she was born in 1907, but changed it to 1910 –the year of the Mexican Revolution– to make her story more compelling. She even altered or erased writings on the backs of photographs to fit this constructed persona. It’s a way she took control of her narrative, showing how conscious she was about her identity and public image.

Did you obtain any new insights about Frida’s character from working so closely on the archive? What stands out is her boldness and complexity. She confronted pain directly –whether physical or emotional– and expressed it openly in her photos and writings. She was both fragile and strong – fragile in the vulnerability of her images, but strong in how she chose to document and reinterpret her life. The archive reveals a woman deeply engaged in constructing her story, unafraid to show all sides of herself.

What would you describe as the most important takeaway from this archive for those who seek a better understanding of Frida Kahlo? That Frida was not just the iconic artist we see in popular culture; she was a woman who rewrote her life’s narrative with courage and nuance. The archive shows Frida to us as a real person – vulnerable, daring, and thoughtful. It invites people to see beyond myths and connect with the true spirit of Frida. n

In today’s Thessaloniki where past, present, and future are in constant dialogue an iconic work of art is preparing to come to life, once more. Umbrellas by renowned Greek sculptor Giorgos Zongolopoulos is entering a new chapter. This celebrated hydrokinetic sculpture, which unites the movement of water, the harmony of form, and the allure of sound, will soon be restored and renewed in recognition of its artistic significance.

KEIMENA/ΤΕΧΤS

team, Now

At the top of the page and on the right: “Umbrellas” at MOMus-Museum of Contemporary Art.

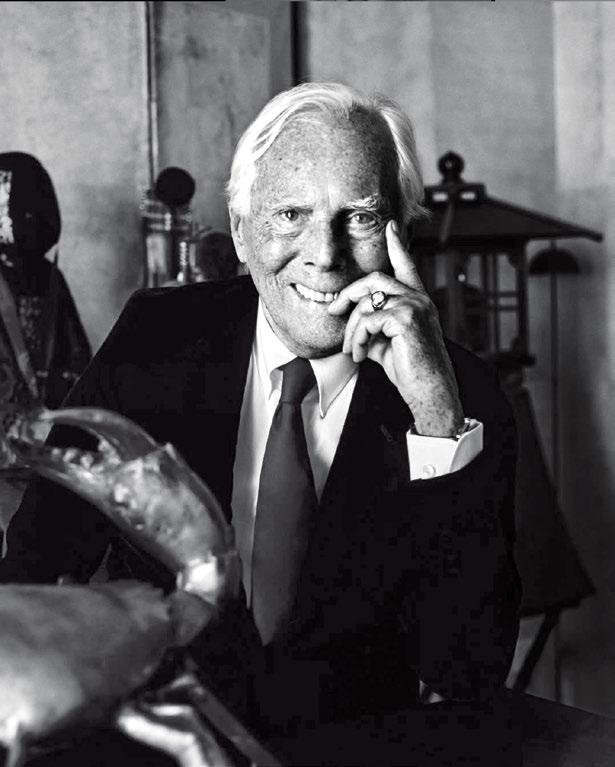

Above: Konstantinos Ignatiadis (1958, Greece), George Zoggolopoulos’ portrait, 1992. Photograph, 42x42 cm. Donation by the artist (2006).

© MOMus-Museum of Contemporary Art-Macedonian Museum of Contemproary Art and State Museum of Contemporary Art Collections.

The Umbrellas, which grace the exterior of the MOMus–Museum of Contemporary Art, located on the wider site of the Thessaloniki International Fair-Helexpo (TIF), is set to undergo full restoration through a comprehensive maintenance program. This initiative is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Thessaloniki Water Supply and Sewerage Company EYATH S.A., in strategic collaboration with the Metropolitan Organisation of Museums of Visual Arts of Thessaloniki (MOMus). A key partner in this effort is the Papageorgiou Foundation, which together with Deloitte Greece, funded the essential preliminary cleaning of the sculpture’s stainless-steel surfaces.

The upcoming restoration includes the complete repair and upgrade of the hydrokinetic mechanism, along with enhancements to the hydraulic systems, to make sure the sculpture continues to offer a unique, immersive experience. The work will be carried out by a team of specialized professionals, under the supervision of the George Zongolopoulos Foundation, in order that the Umbrellas return renewed to the city’s audience.

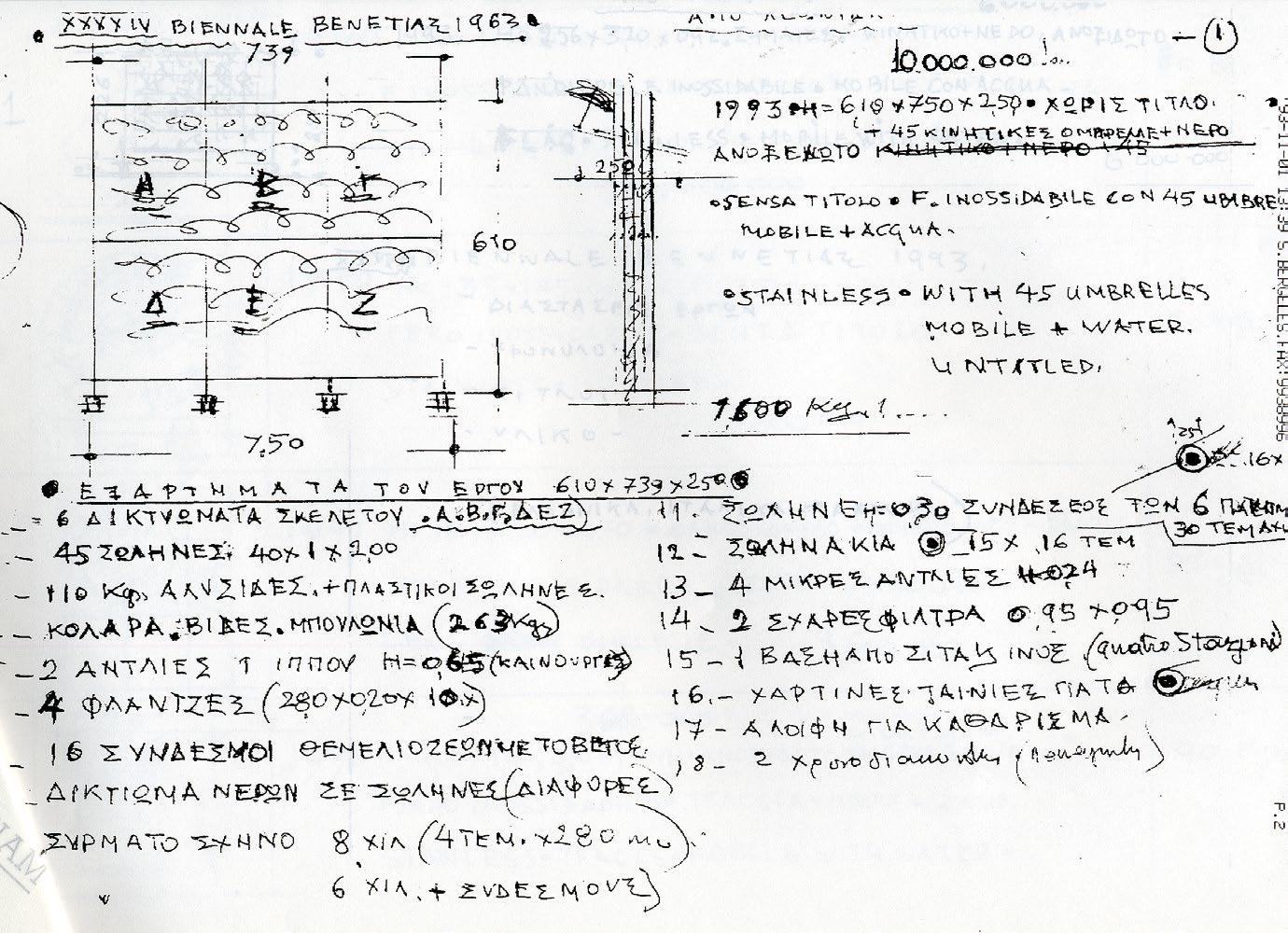

Sculptor Giorgos Zongolopoulos installed the large-scale, stainless steel hydrokinetic sculpture Umbrellas on the waterfront at the entrance of the MOMus–Museum of Contemporary Art (then the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art) during his first solo exhibition in Thessaloniki in 1993. The installation was also presented as Greece’s national entry at the 45th Venice Biennale, and then later erected in its current location. The site was personally selected by the artist, who oversaw the installation in a collaborative effort with the engineering department of the TIF and the School of Architecture and Engineering at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, which also contributed to its design and construction. Initially loaned to the museum until 1995, the sculpture was briefly moved to a private collection. However, in 1996, its acquisition was secured thanks to the support of collector Prodromos Emfietzoglou and businesswoman Annie Michaelidou guaranteeing its permanent return to the museum’s collection.

Umbrellas by Giorgos Zongolopoulos is among the most iconic works of contemporary Greek sculpture. The hydrokinetic version, housed at the MOMus–Museum of Contemporary Art, reflects the artist’s evolving vision and his deep interest in fusing art with technology. In this work, water becomes a central element alongside movement and sound to create a dynamic interaction with the natural environment. It highlights flow and transformation, while also enriching the immersive side of art.

Giorgos Zongolopoulos (1903–2004) was born in Athens and studied sculpture at the Athens School of Fine Arts under Thomas Thomopoulos. In 1937, he became acquainted with the work of Charles Despiot. Beyond sculpture, his work also includes painting and architecture. Throughout his career, he collaborated with leading figures in the Greek arts scene, including Dimitris Pikionis, Patroklos Karantinos, and Konstantinos Parthenis, and received numerous distinctions and awards for his work.

Zongolopoulos was intensely interested in the relationship between sculpture and the surrounding space. Influenced by the kinetic art movement of the late 1950s and 1960s, he explored the transformation of static forms through the continuous flow of water. The artist’s work is marked by this constant evolution of form, material, media, and spatial interaction. Through an imaginative and pioneering use of movement, shape, and sound, he created a dynamic dialogue between his sculptures and their environment, a vision fully manifested in the Umbrellas. n

Handwritten notes by George Zoggolopoulos. © Archive MOMus-Museum of Contemporary Art.

“Collaboration between business and the arts is not a privilege” underlines Agis Papadopoulos, Chairman of the Board of Directors of EYATH S.A.

Allow me to begin our conversation with a very important development: the sponsorship by Water Supply and Sewerage Company EYATH S.A. to restore Giorgos Zongolopoulos’s iconic sculpture Umbrellas, located outside the MOMus–Museum of Contemporary Art, on the grounds of the Thessaloniki International Fair-Helexpo. This work is often overlooked in comparison to Zongolopoulos’s more well-known sculpture of the same name on the Nea Paralia. What inspired you to fund this initiative?

By supporting culture and the arts, EYATH S.A. reconfirms its commitment to the local community by giving back to our fellow citizens. Beyond that, for a company like EYATH S.A., the restoration of an iconic work such as the hydrokinetic Umbrellas, uniting water movement, harmonious form and sound underscores the vital role engineering plays in the cultural sphere. I believe that restoring its function will help it receive the attention and recognition it truly deserves.

As President of the Water Supply and Sewerage Company EYATH S.A., how do you view the role of major companies and organizations in relation to the arts? Are collaborations between the business world and artistic creation a privilege or, rather, a necessity?

And in what ways could companies like EYATH S.A. act as catalysts in a broader effort to introduce more art into our daily lives?

The environment we live in shapes every aspect of our daily lives. The work of a water supply company or, more broadly, any business doesn’t happen in isolation. It takes place within the urban landscape, serving people who live, work, socialize, and collectively shape that very environment. This symbiotic relationship with our environment becomes far more effective when societies are both environmentally conscious and culturally engaged.

Through sustainable resource management and a strong sense of social responsibility, large companies can reduce risk, build resilience, and safeguard their future. That’s why Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has rightfully become a key element in modern business strategy.

For this reason, I don’t see partnerships between businesses and artistic creation as a privilege.

Yes, it’s cost intensive. But it also represents a valuable non-financial investment. I believe this is something we’ve come to understand quite well in the Greek business landscape.

You have a distinctly technocratic background. With a degree in Mechanical Engineering from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, you were a professor for 27 years in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, a chartered member of the Energy Regulatory Authority, a national expert at the European Commission, and, in recent years, a board member of the German-Hellenic Chamber of Commerce and recently elected Chairman of the Board at EYATH S.A., among many other roles. These are only a few of your many credentials that highlight your title as a technocrat. There’s an urban myth that technocrats are indifferent to art. What is your own relationship with artistic creation?

First off, I don’t entirely agree with the “technocrat” title. Whether you’re a university professor or managing a large organization, these roles require putting people at the center; be it your students or the organization’s staff, all working toward a shared goal. This isn’t a purely technocratic role in its narrow sense, but rather involves the effective use of resources, scientific methods, and technology to achieve objectives that ultimately serve people.

“I’ve never understood why an ENGINEER couldn’t have a PERSONAL CONNECTION to art.”

I’ve also never understood why an engineer couldn’t have a personal connection to art. The works of Monet, the architecture of Konstantinidis, or the classic albums of Pink Floyd are guided by principles of aesthetics and balance. These are principles that aren’t so different from the laws of thermodynamics or mathematics, which themselves embody harmony and reveal fundamental patterns.

I assume that this sponsorship for the restoration of the Umbrellas is not EYATH S.A.’s first time supporting the arts. The question is will it be the last? Are there any plans going forward for the company to take a more active role in the broader fields of art and culture?

At EYATH S.A., we believe that cultural sponsorships have the greatest impact when they address genuine needs whether those of cultural institutions or the wider community. We focus on targeted initiatives that deliver real value, offering practical and measurable solutions to actual challenges.

All our efforts are guided by two fundamental principles: avoiding waste and steering clear of over-promotion.

Let me share two examples that illustrate the philosophy behind how we operate. In collaboration with architect Prodromos Nikiforidis, we designed the fountains installed along Nea Paralia to be both aesthetically harmonious with their surroundings and fully functional. Despite initial concerns, the public embraced them with enthusiasm and respect. Over the past year, these fountains have provided thousands of visitors with free drinking water, helping reduce plastic bottle consumption and

waste. We are now extending this initiative to Egnatia Street as well.

Similarly, we invited young street artists to create art on the facades of the pumping stations on Kassandrou and Analipseos Streets. These buildings have been revitalized, and since then, problems like visual pollution from posters and tagging have disappeared.

We carefully listen to real needs and respond accordingly, not for publicity, but because we believe this is how we can truly contribute to improving our city and maximizing the social impact of our work. n

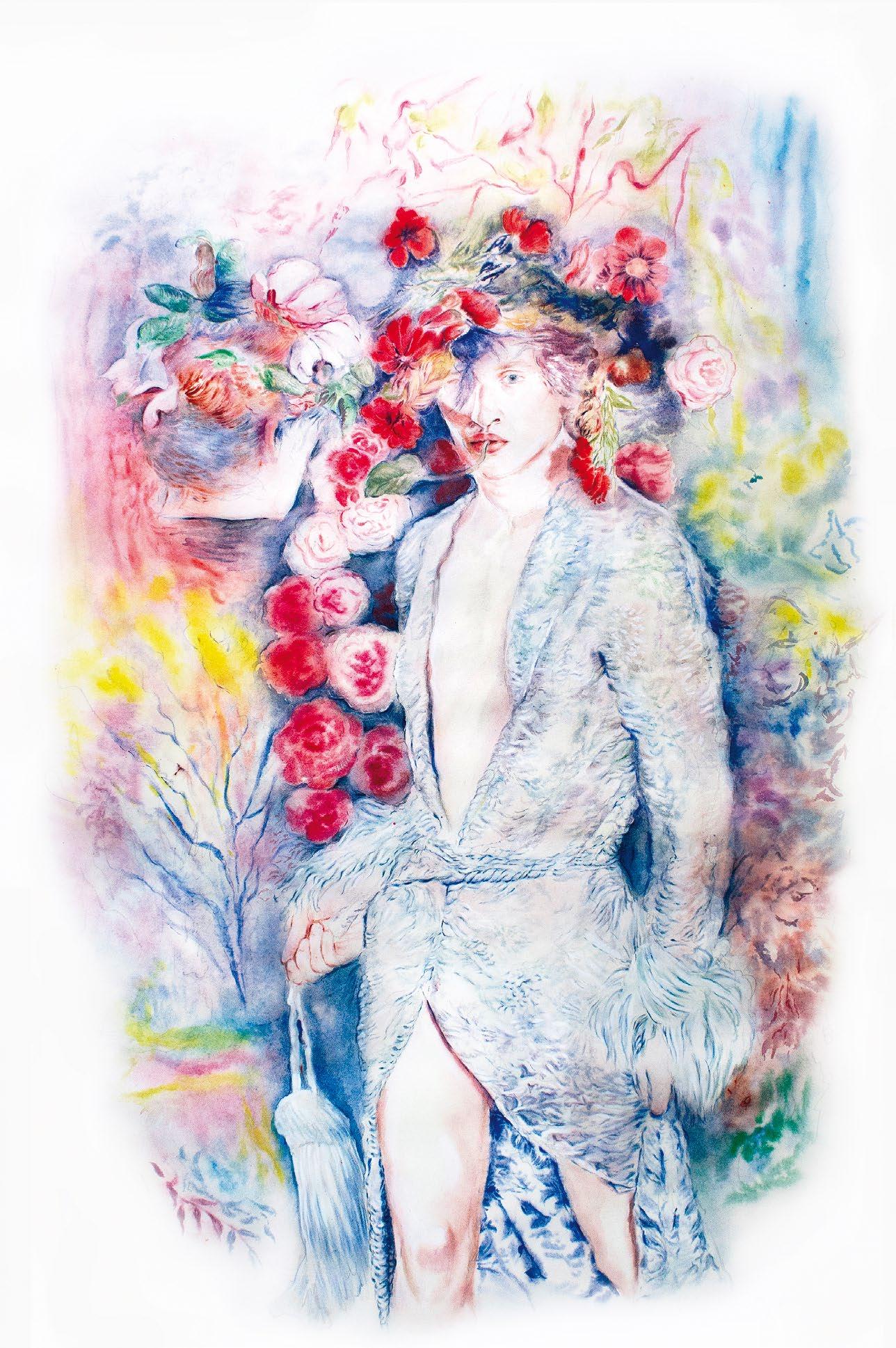

The unification of art through the abolition of gender, nation, and any identity consciousness in Marianna Ignataki’s artistic work is both the aim and the omnipresent purpose of her work. Fashion often follows on the same paths. KEIMENA/ΤΕΧΤS

Marianna Ignataki was born in Thessaloniki, Greece in 1977. She studied Architecture at the Technische Universität in Vienna (Austria) and Visual Arts at the School of Fine Arts of Saint-Etienne (France). Between 2010-2017 she was based in Beijing (China). She now lives and works between Berlin and Athens. She has presented thirteen solo exhibitions to date and she has participated in a number of group shows in Europe, China and the USA.

Working primarily in drawing, painting and sculpture, Marianna Ignataki’s practice enables her to enter a vague, subliminal world, filled with images of her own mythology. Her work ranges from minimalistic scenes and portraits to exaggerated, kitsch, Rococo inspired compositions.

It explores themes of identity and the perception of self, the other side; a dream that turns to nightmare, the attraction to terror, the fascination with carnival, the freedom and the ambiguous feelings provoked by the use of masks. The works are mainly anthropocentric, with female or ambiguously-gendered protagonists that resemble witches, animals or hybrids. Often, an unspecified or even perversive eroticism is implied, one that does not concern sexuality in the sense of sexual act but the mental state of erotic desire; our instincts, or a hidden dark side. These vague, surrealistic scenes, play with the notion of the absurd and combine seemingly heterogeneous elements which are subtly linked through compositional elements. By adding unexpected details with a sense of dark humor, the initial meaning of seemingly normal scenes is inverted or perverted, resulting in ironic, bizarre and grotesque situations. n

Μαριάννα

Boy You Turn Me – Never on Sundays, 2021.

Androulidaki Gallery,

Marianna Ignataki, Boy You Turn Me – Never on Sundays, 2021. Watercolor, gouache, color pigments, graphite and colored pencils on paper, 109x71 cm. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki Gallery, Athens.

More for the artist on her webpage, http://mariannaignataki.de/

2025. Giorgio Armani, Spring/Summer 2025 collection.

Armani

Giorgio Armani has created a style that has, with remarkable consistency, continued to explore countless variations and possibilities over the years. In expressing a precise vision – down to the most minute detail, it is a style in the truest sense of the word: a way of being and presenting oneself, certainly incorporating clothing and accessories, but also including gestures, ways, behaviours and attitudes; something that goes beyond the sum of its parts, and well beyond what one wears.

Convinced that ethics and aesthetics must coincide, Giorgio Armani expresses fundamental and enduring values through style. He does so by creating timeless pieces that, enhanced by precious materials and artisanal craftwork, resist the whim of fleeting trends with their pure and essential design. Clothes that favour a fluidity that is as much lightness in their constitution as it is a natural progression in the fusion of masculine and feminine codes, in order to convey an alluring and personal femininity and a soft and conscious masculinity.

Giorgio Armani embraces a concept of inclusion that is rooted in the mind, first and foremost, rejecting mainstream status symbols in favour of strong personalities and bright figures, to whom he presents creations that stand the test of time because they originate from the idea that less is more, namely from the conviction that good design has no expiration date and has nothing to do with irresponsible consumption. Style thus becomes a sustainable way of life.

Giorgio Armani articulates his unique vision through the extreme discipline garnered by his uncompromising nature: firstly, with himself in his relentless pursuit of continuous improvement; but above all through his independence, a founding and arduously defended quality, the only way to guarantee free and individual expression – a kind of authenticity that has turned style into a lifestyle. n

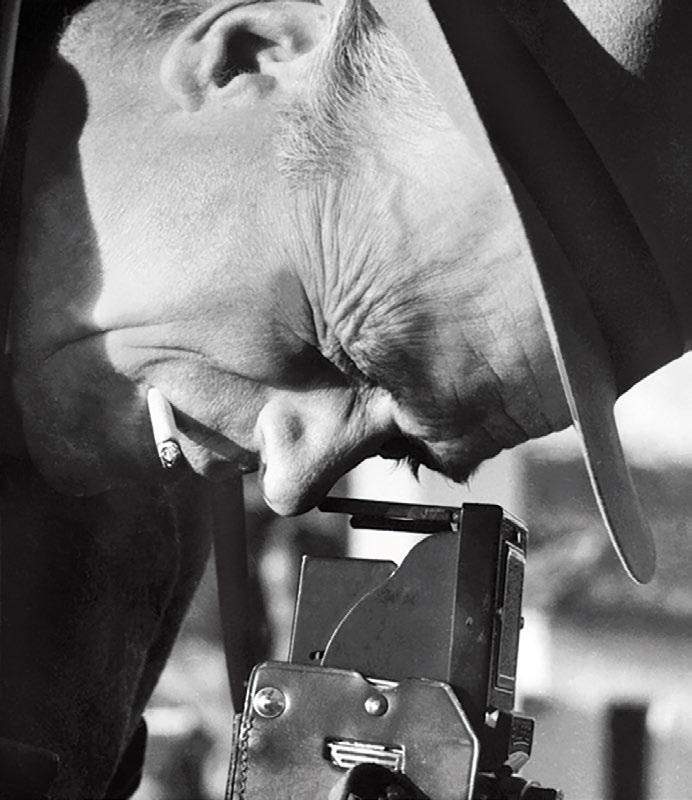

If you could invite a famous artist to dinner, with a top chef preparing the menu, who would you choose? And what would you serve? In this issue, MOMus “invites” photographer Dimitris Letsios (1920-2008) to dinner, drawing inspiration from his artwork “Porta-Panagia, Trikala,” and taps into the creative imagination of Manolis Papoutsakis, chef and co-owner of restaurants “Charoupi” and «Deka Trapezia» in Thessaloniki and «Pharaoh» in Athens, to prepare the menu.

Σημαντική

An important figure in postwar Greek photography, Letsios (1920-2008) depicted mainly the landscape and common people of Thessaly, with an emphasis in the Pelion mountain, as well as Volos, his city of birth. His work runs the traditions and popular art of the countryside in architecture, costumes, and rituals during the postwar period, that were gradually marginalized by modernity.

His early ecological interests during the 60s led him to depict the landscape after the drainage of lake Carla. In his work, Letsios has also consistently attempted to record the life and perseverance of the post-war countryside woman, most often in conditions of deprivation and absolute poverty. n

What would chef Manolis Papoutsakis* make for Dimitris Letsios?

Garlic resting on the counter. Ready to be braided just as women once braided their hair. Skordalia garlic puree, lemony rabbit, braided string beans. A Greek dish, local ingredients, carefully measured. Simplicity, art, and deliciousness; a language our kitchen should always understand. It’s the language of our tradition: inspiring and guiding, it sets us apart. This recipe is a tribute to the women who braid garlic. We owe them a lot. n

1

1

6

1

Ingredients

1 rabbit, cut into portions

1 kg long string beans

500 g potatoes

6 cloves garlic

Juice of 3 lemons

4 tablespoons aged vinegar

200 ml white wine

1 teaspoon oregano

300 ml extra virgin

olive oil

100 g all-purpose flour

Salt

Pepper

Instructions

Trim the string beans and blanch them in boiling salted water for 2 to 3 minutes. Cool them quickly in ice water to keep them crisp. Secure the top ends of three string beans on a toothpick and braid them together. Secure the bottom ends again with a toothpick. Repeat this with all the string beans. Marinate the braids with the juice of one lemon, 20 ml olive oil, salt, and pepper.

Season the rabbit with salt and pepper, then dredge it well in flour. In a saucepan, heat 150 ml of olive oil and sauté the rabbit until it takes on a nice golden color. Add the 2 cloves of garlic, chopped, and finish with 2 ta

τη ρίγανη, 100 ml νερό, χαμηλώνουμε πολύ τη φωτιά και μαγειρεύουμε με καπάκι για 40 λεπτά, χωρίς να ανακατεύουμε.

Βράζουμε τις πατάτες ξεφλουδισμένες. Αλέθουμε το σκόρδο σε μπλέντερ μαζί με τον υπόλοιπο χυμό λεμόνι, το υπόλοιπο ξύδι και το υπόλοιπο ελαιόλαδο. Πατάμε τις πατάτες ώστε να γίνουν ένας λείος πουρές και προσθέτουμε το μείγμα που αλέσαμε. Αλατοπιπερώνουμε, αναδεύουμε καλά και δοκιμάζουμε.

Αφαιρούμε τις οδοντογλυφίδες από τα φασόλια

blespoons of vinegar, the white wine, and the juice and zest of 1 lemon. Add the oregano and 100 ml of water. Reduce the heat to very low, cover the saucepan, and cook for 40 minutes without stirring.

Boil the peeled potatoes. In a blender, grind the garlic with the remaining lemon juice, vinegar, and olive oil. Mash the potatoes until smooth, then stir in the garlic mixture. Season with salt and pepper, mix well, and taste.

Remove the toothpicks from the string bean braids and arrange them in a neat row, trimming any excess. Brush a little of the rabbit sauce over the beans. Place the rabbit pieces on top of the braids. Dot with spoonfuls of the garlic puree around the dish, then pour the sauce from the pot over everything.

For a smoother sauce, strain it through a sieve. If the sauce is too thin, remove the meat and reduce the sauce over high heat until it thickens. n

Discover a refined dining destination in the heart of Thermi, Thessaloniki. At Shelbys, every plate tells a story, crafted with precision, passion and premium ingredients. Savor perfectly grilled meats, indulge in gourmet creations, and explore a handpicked wine list that ranks among the city’s finest. From the first bite to the last sip, excellence is served.

SCAN QR CODE TO SEE THE MENU

menu-shelbys gr

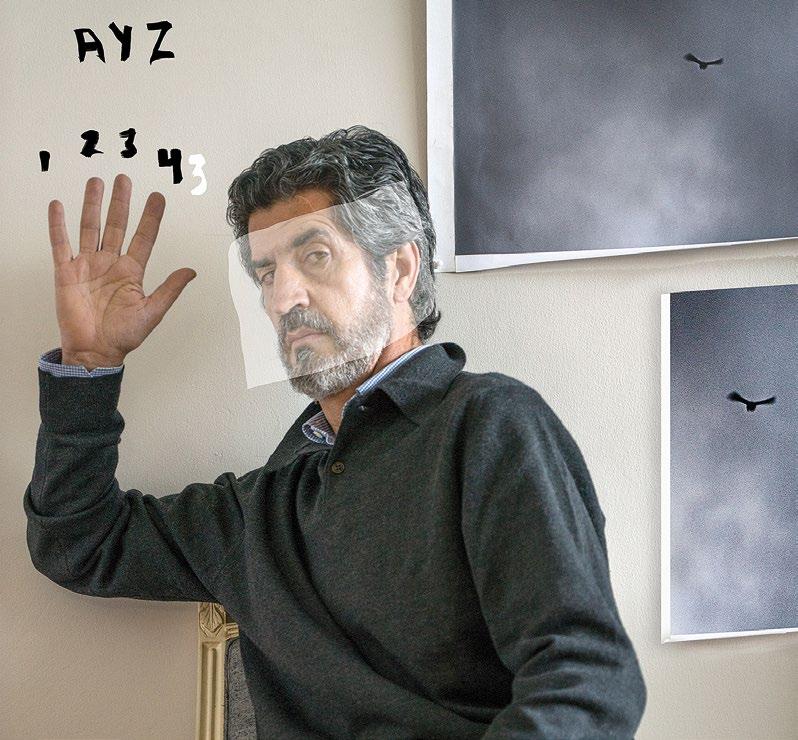

For architect and visual artist Giorgos Ouzounis (Super G), contemporary explorations of the post-human condition, neo-materialist feminism, transhumanism, queer theory, and ecological thinking are fields of inquiry, reflection, and creative expression, reimagined through emerging technologies in his own digital universe.

ΣΥΝΕΝΤΕΥΞΗ/INTERVIEW

Iόλη Φωκίδου/Ioli Fokidou

ΦΩΤΟΓΡΑΦΙΑ/PHOTOGRAPHY: Περικλής Μεράκος/Pericles Merakos

Your journey began in Thessaloniki. How did your path unfold from there? And how important is the city, the place where your journey started, to you today?

I was indeed born and raised in Thessaloniki, where I also studied Architecture but in recent years, I’ve been living and working in Athens as both an architect and a visual artist, mainly focusing on 3D rendering.

For me, Thessaloniki remains a consistent point of reference. No matter what happens, it’s a place of stability that I know well, and that’s familiar. It’s where I first encountered the visual arts, and the city continues to be a personal refuge largely due to its scale and rhythm. That said, I don’t imagine myself living there permanently, at least not for now.

As an architect, has your relationship with space and design influenced your visual work? And if so, how?

MOMus (www.momus.gr)

WHERE & WHEN: George Ouzounis participates in the exhibition “Technofetishism: Whip it into Shape,” hosted until August 31st 2025 in MOMus-Experimental Center for the Arts (Warehouse B1, Pier A’, Port) in Thessaloniki. Before your visit, please check the MOMus website (www.momus.gr) for latest updates.

ταυτότητες. Το ρεύμα αυτό απορρίπτει παραδοσιακούς δυισμούς, όπως «φύση/πολιτισμός», «σώμα/νους», «άνθρωπος/τεχνολογία». Τονίζει ότι τα πάντα βρίσκονται σε συνεχή αλληλεπίδραση –υλικά, σώματα, περιβάλλοντα, τεχνολογίες–

αυτήν τη φάση αρχίζω να συγκεντρώνω υλικό, εικόνες, αναφορές

My initial interest in architecture was more theoretical than practical. I was always drawn to what space says about how we live, and what we aspire to become rather than just its physical construction.

Architecture gave me the tools I now consider fundamental to my practice especially in digital photorealism and spatial representation. Still, I gradually felt that the architectural framework didn’t fully accommodate the expressive needs I had. That’s when I began shifting toward a more visual and artistic practice.

Through my work, I learned to work with diverse materials, to design with precision, and to focus on detail, all of which naturally carried over into my visual work.

Most of my pieces have a scenographic quality and a strong “fixation” with realism and meticulous representation. They often resemble realistic installations even though they exist entirely in digital space.

Equally, my education in architecture also opened the door to theoretical fields that continue to shape my thinking. Concepts around ecology, post-human and the body, have become central to how I approach my work and right now form the core of my artistic language.

Art allows for many forms of expression. How did you arrive at your own? Where do you see your work heading?

A major turning point for me was encountering the philosophical movement of New Materialism. It really shaped how I approach complexity in the contemporary world — especially the interconnectedness between bodies, materials, technologies, and identities.

New Materialism challenges binary thinking: it rejects separations like nature/culture, body/mind, or human/ technology. It insists that everything is in constant interplay. Materials, organisms, environments; none can be understood in isolation from the others.

For me, every creative process begins with research, whether theoretical or visual. I collect references, images, objects, and ideas that resonate. From there, I move into the production phase, primarily using 3D scanning, a method based on photogrammetry that allows me to transfer real-world objects into digital space. Think of it as a three-dimensional photograph. I scan bodies, organic or artificial forms, or use existing digital models as a foundation.

These items become the raw material I build on, edit, transform, add or subtract depending on what I want to express. The final compositions often blend personal experience with speculative or imaginary scenarios. They function as experimental spaces where identities, situations, or desires can be reimagined or reshaped. In that sense, my work embodies transformation both in theory and form. It moves fluidly between what we see as opposites: analog/digital, physical/virtual, organic/ technological.

Ultimately, what I’m after isn’t just imagery or form but a kind of visual thinking. A way of reflecting on and renegotiating how we understand the body, matter, and our evolving relationship with the world around us.

How much have you experimented with different techniques and how much do you apply new technologies to your work? Has artificial intelligence brought a new era to art?

New technologies are an integral part of my work. They help me practically. For instance, I can scan objects much faster and more accurately or create 3D models starting from just a photo.

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools greatly facilitate

processes that previously required time and technical expertise. However, its presence doesn’t imply that everything is simple or innocent. As in other fields, the use of AI technologies in art raises questions such as is it ethical towards other creators or environmentally friendly? It can often reinforce existing inequalities in the way it visually represents situations.

I think of the fantasy that developed at the dawn of the internet and cyberfeminism: the idea of a technology that does not reproduce existing patterns of power, but offers ways of escape, liberation and redefinition. A technology that can be fluid, illusory and collective. Yet reality often shows the opposite. From social media to dating apps and AI assistants, technology seems more gendered, sexist and controlled than ever, designed to be addictive and primarily serve profit.

I believe we need to invent new fantasies (beyond the dystopian scenarios of technology that dominate pop culture, such as in the Black Mirror series) and start imagining it in a positive way, giving it new content and possibilities. Through my own practice I try to articulate exactly this: environments and bodies that suggest other ways of being, instead of merely existing.

Tell us about the group exhibition at MOMus in which you are participating, your own works and how they fit into the concept of “Technofetishism.”

The exhibition at MOMus, curated by Eirini Papakonstantinou, is a very important initiative, and not only because it deals with an absolutely contemporary theme, but also because it approaches new technologies in a theoretical, political and socially situated way. Technofetishism to me is a very precise tool when reflecting on our relationship with technology. It speaks of a desire that contains dependence, pleasure, guilt and often –covert or overt – danger. It’s not just usage, but something that nestles within us, like a fantasy or obsession.

I am displaying four of my works at the exhibition, but I will focus on Intimate. It shows a man bound with shibari ropes, suspended from a mechanical arm. The scene remains open to interpretation. It is not clear whether he is in a state of pleasure or whether a limit has been crossed. The work explores how changing relations of power and intimacy with technology can open up new avenues for erotic expression. My interest here is the possibility of creating new forms of connection – even through mechanical or digital means – without losing awareness of the dynamics they bring. My stance isn’t technophobic, but a position that recognizes the complexity of our relationship with technology; a relationship that is at once physical, imaginary and often ambiguous. n

“TECHNOFETISHISM to me is a very precise tool when reflecting on OUR RELATIONSHIP WITH TECHNOLOGY. It speaks of a desire that contains dependence, pleasure, guilt and often –covert or overt – danger.”

Take a piece of MOMus with you. At the end of your visit, stop by our museum gift shops and discover gifts, publications, prints, office supplies, jewellery, ceramics, clothing, accessories, and collectible items, with high artistic value in every piece.

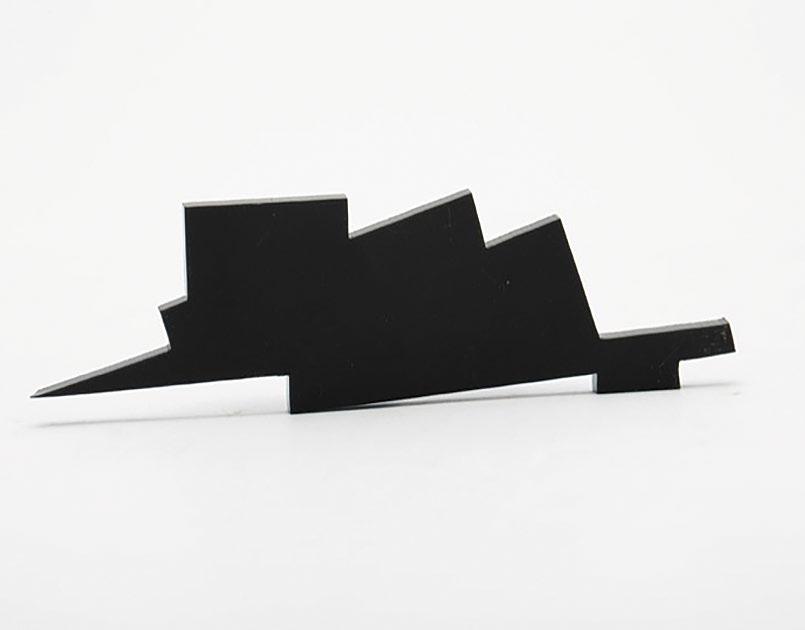

MALEVICH BROOCH.

Plexiglass brooch, laser-cut, featuring a shape from Kazimir Malevich’s Draft for a Suprematist Composition (undated), part of the Costakis Collection at the MOMus–Museum of Modern Art.

Plexiglass

ΠΛΕΞΙΓΚΛΑΣ «OVERSHADOW».

«Overshadow» (2017)

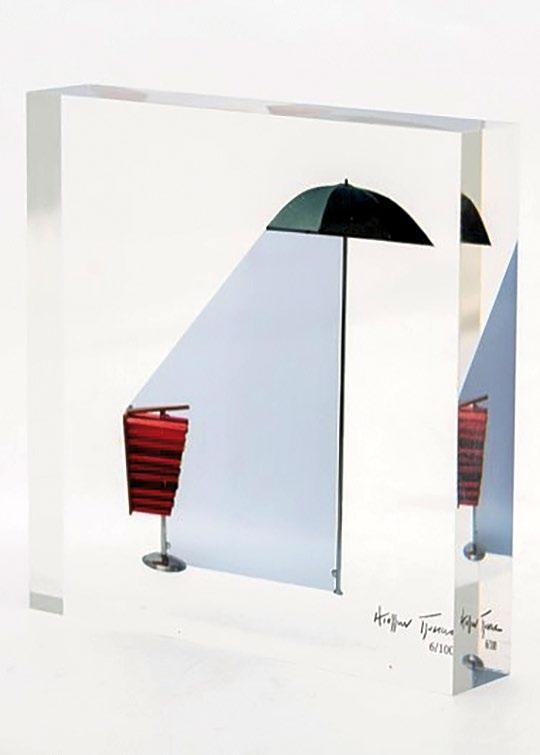

OPTIPLEX MAM “OVERSHADOW.”

Print of Apollon Glykas’ “Overshadow” (2017) on the inside of a special plexiglass construction, from the exhibition “Syzygy. Solid Light & Timeless Motion.”

Τιμή/Price:

Μυλωνά. Now available at the MOMus-Μuseum

Alex Mylona gift shop.

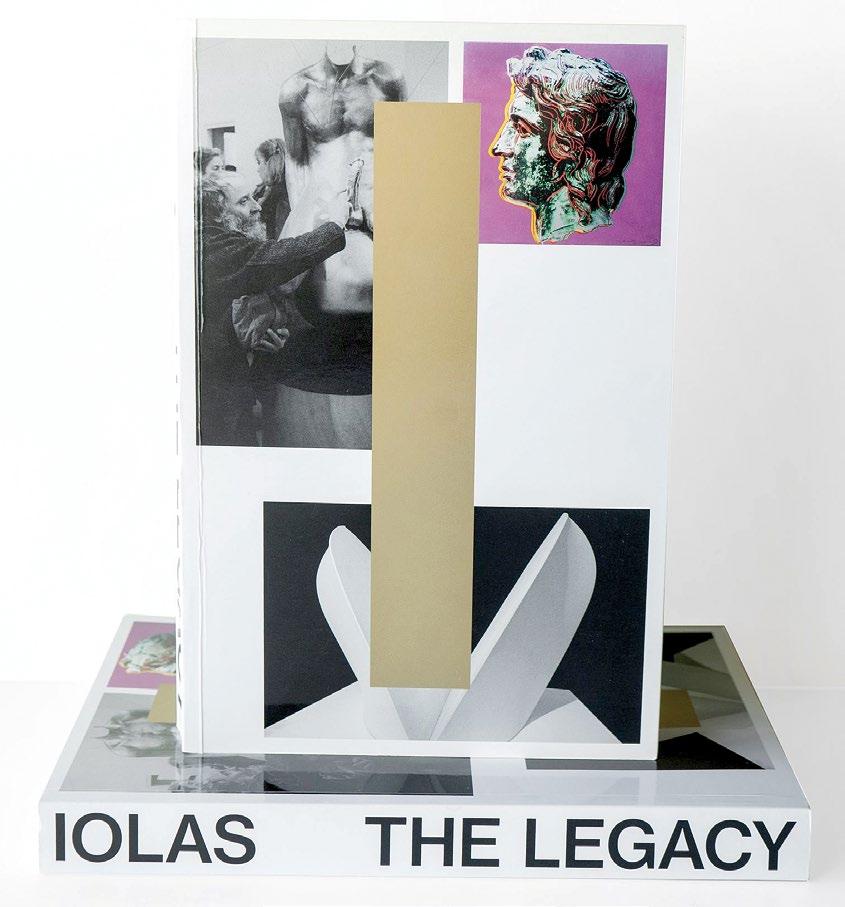

title, held at the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art (now MOMus–Museum of Contemporary Art) from October 6, 2018, to March 31, 2019. Thirty years after his death, a tribute exhibition was organized in honor of Alexander Iolas, accompanied by the corresponding catalogue titled “Alexander Iolas: The Legacy.” Through theoretical texts, research and archival material—including historical photographs and letters— the catalogue highlights Iolas’s artistic and social activity and network, his personality and engagement with contemporary art, and especially his revealing relationships with a wide array of artists, vastly different from one another.

CATALOGUE. The reissue of the emblematic catalogue that accompanied the exhibition of the same

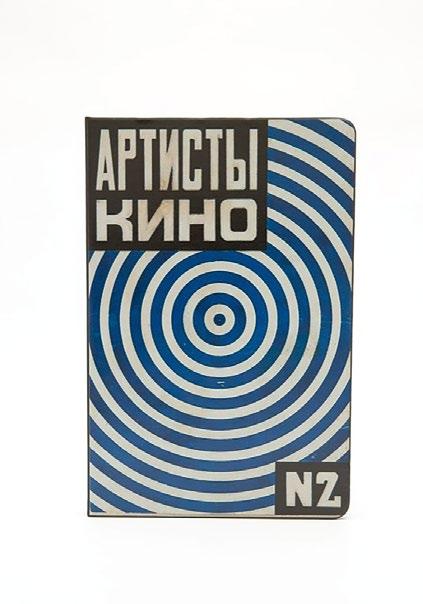

NOTEBOOK LYUBOV POPOVA. Hardcover notebook with an elastic band featuring Liubov Popova’s “Design for Cover of Magazine Film performers vol. 2” (c. 1922) from the Costakis Collection.

10

Now

Now available at the MOMus–Museum of Contemporary Art gift shop.

NOTEBOOK “ALEXANDER THE GREAT.” Hardcover notebook with an elastic band featuring Andy Warhol’s artwork “Alexander the Great” (1981). Τιμή/Price: 10 ευρώ/euros

Now

at the MOMus–Museum of Contemporary Art gift shop.

REFLECTIVE BRACELET.

Available in four vibrant colors: silver, yellow, blue, and pink.

Τιμή/Price: 2

CERAMIC MUG. Handmade ceramic coffee mug inspired by the work of Ivan Kliun from the Costakis Collection at MOMus–Museum of Modern Art. Created by Giorgos Vavatsis.

Now available at the MOMus–Museum of Modern Art gift shop.

«ANDRÉ KERTÉSZ.

MOMus-Thessaloniki Museum of Photography. The Thessaloniki Museum of Photography, in collaboration with Agra Publications, has co-produced an album about one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century, André Kertész (Hungary 1894-USA 1985). The publication was released on the occasion of the photographer’s major retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Cycladic Art, following the corresponding exhibition in Thessaloniki. The volume consists of 216 pages with introductory texts by Platon Rivellis, as well as 140 selected photographs by Kertesz, strictly chosen from his entire oeuvre, which have had a drastic influence on 20th century photography.

Τιμή/Price: 20 ευρώ/euros

MIRROR OF A LIFE” CATALOGUE.

Catalogue of the exhibition of the same name. It includes works from the corresponding exhibition hosted at the

Now available at the MOMus -Museum of Photography of Thessaloniki gift shop.

HAIR TIE.

Hair accessory based on Ksenia Ender’s “Untitled” (1924-26) from the MOMus-Museum of Modern Art Costakis Collection. Oversized hair tie that can be worn in the hair or on the wrist as a bracelet.

Made of cotton fabric with satin texture.

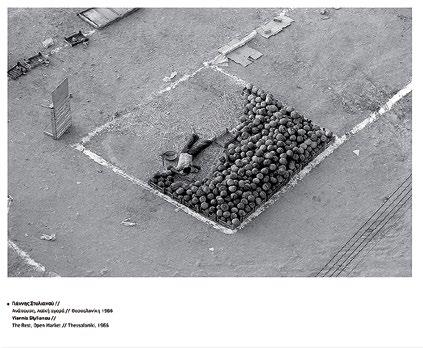

POSTER ABOUT HUMANS “THE REST, OPEN MARKET.” Digital print on museum-quality paper of Yiannis Stylianou’s artwork “The Rest, Open Market” (1966).

Τιμή/Price:

the MOMus-Museum of

of Thessaloniki gift shop.

KLIUN FOLDED FAN. Folding paper fan with a bamboo base based on Ivan Kliun’s “Untitled” (1919-20) from the Costakis Collection of the MOMus-Museum of Modern Art.