MOMus – Thessaloniki Museum of Photography visits the Corinthian hinterland and invites both locals and visitors to explore the impact of human activity on

MOMus – Thessaloniki Museum of Photography visits the Corinthian hinterland and invites both locals and visitors to explore the impact of human activity on

To the

The MOMus Magazine is a quarterly publication available free of charge at MOMus museums in Thessaloniki and Athens, as well as at selected distribution points and online. Any reproduction, redistribution, or adaptation of the magazine’s content, whether in full, in part, summarized, paraphrased, or otherwise rendered by mechanical, electronic, photocopying, or recording methods is strictly prohibited without prior written consent from the publisher, in accordance with Law 2121/1993 and applicable international legal provisions in Greece.

Θεσσαλονίκη,

Thessaloniki. A city that carries centuries-old heritage where Ottomans, Romans, Jews, and Macedonians once crossed paths, now faces its greatest challenge: to find a modern identity.

At MOMus, we envision a Thessaloniki with a dynamic urban culture, where new ideas flourish, and are put to the test. A place with no limits, a wealth of opportunities and quality of life. At MOMus, we want to support our city, challenge conventions and sow the seeds to create a modern, mixed and tolerant culture. In Picasso’s words, “every act of creation is first an act of destruction.” It’s within this process that we see art as the essential ingredient the new Thessaloniki needs.

Looking back, we’re humbled by our many small successes that, together, have taken us to new heights. We’ve improved our internal organization, strengthened our finances and upgraded our work environment. We've revamped our infrastructure and visitor experience, staged major exhibitions abroad and brought big names to Thessaloniki, Kabakoff, Nelly's and the inimitable Pablo Picasso to name a few. Above all else, we’ve regained people’s trust with actions that express our new vision — a vision that is deeply connected to how we, the people of MOMus, see our contribution in elevating the city, and the responsibility this entails.

With the MOMus magazine, we’re seeking new ways to reach a wider audience, and bring more people closer to us. We want you to travel with us, discover new partners, supporters and other travellers — and along the way build a community that adores modern culture.

Like many of us in Greece, contemporary art was unknown territory to me; I felt I didn’t understand it. Until, in 2012, on a trip to Tokyo, I stumbled upon the National Museum of Modern Art, which was then hosting the "Jackson Pollock: A Centennial Retrospective" exhibition. His works absolutely captivated me and, as they say, the rest is history. We hope the MOMus magazine will inspire more people to join us, and I hope you’ll be among those lucky enough to stand before a piece of art that truly speaks to you. n

Epaminondas Christophilopoulos

MOMus president

Γιούλα & Όλγα Παπαδοπούλου, «I am I», 2024. Βίντεο/εργαλεία AI. Above: Gioula & Olga Papadopoulou, «I am I», 2024. Video/AI assisted. Εικόνα/Image:

ΕΚΘΕΣΗ ----- «ΕΙΜΑΣΤΕ

EXHIBITION ----- “WE ARE ALL MADE OF STARS”

The exhibition focuses on new media, digital art, and contemporary technologies within visual art practices. “We Are All Made of Stars” comes from the understanding that humanity is intrinsically connected to the universe, made from the same elements as the vast, mysterious cosmos, and that all living beings are equal, sharing the same rights within our earthly world.

The main objective of the exhibition is to present the work of visual artists, both emerging and established, who are inspired by the latest developments in science and technology. These include space travel and exploration, the discovery of new worlds and future human habitation. At the same time, “We Are All Made of Stars” aspires to provoke reflection on crucial and complex social, political and economic issues that are timeless in human culture, as well as to communicate any form of contemporary art that involves technology in its completion to a wider audience.

Featuring over 30 works by Greek and international artists, “We Are All Made of Stars” is the result of a collaboration between MOMus – Experimental Arts Center and various festivals, cultural institutions, fine arts schools, and artistic platforms dedicated to promoting digital art and new media.

Curated by: Domna Gounari, MOMus curator. n

WHERE & WHEN: At MOMus – Experimental Center for the Arts (Warehouse B1, Pier A, Thessaloniki Port) from December 12th 2024 to February 23rd 2025. Before your visit, please check the MOMus website (www.momus.gr) for latest updates.

MOMus

Artwork by Rania Emmanouilidou at MOMus

Museum Alex Mylona.

Hybrid creatures and femininities inhabit special worlds and claim freedom of existence in Rania Emmanouilidou’s exhibition, Under the Radar, at MOMus – Alex Mylonas Museum. Representing successive generations that make up the modern world, these evocative creatures “conquer” the museum space.

A Generation Xer, Emmanouilidou observes how cultural realities, and social identities change almost daily. Her work, developed over more than two decades, addresses themes of gender, identity, politics, and ecology, with an ever-present focus on the body. This body, historically, socially, and culturally inscribed, emerges in her art as marked, hybrid, transformed, and performative.

Drawing inspiration from the internet, pop culture, music, fashion, and art history, Emmanouilidou narrates a unique personal mythology where her enigmatic figures deconstruct traditional gender roles and disrupt the linear view of time.

The exhibition is the fourth and last stop in the Museum’s tribute-exhibition series entitled “Four Artists, Four Attitudes”, which features women artists and curators.

Curated by: Thouli Misirloglou, artistic director of MOMus – Museum of Contemporary Art. n

WHERE & WHEN: At MOMus – Museum Alex Mylona (5 Agion Asomaton square, Thissio, Athens) from November 14th 2024 to January 26th 2025. Before your visit, please check the MOMus website (www.momus.gr) for latest updates.

(Paul Zepdji,

Underwood & Underwood).

View of the city of Thessaloniki from the Trigonion Tower, Ano Poli, 1900. Silver print (Paul Zepdji, ed. Underwood & Underwood).

Children and elegant ladies, men in traditional fustanella attire and uniformed officers, and scenes of rural and urban life from the mid-19th century take center stage in an exhibition focused on the fascinating history of stereoscopy as a photographic technique. This captivating art-technique is celebrated in the exhibition Stereoscopy, a joint effort by MOMus – Thessaloniki Museum of Photography and the Museum of Photography of the Municipality of Kalamaria “Christos Kalemkeris”.

Stereoscopy, introduced as an invention in England in 1841, quickly gained traction after 1850, first in France and then across Europe and America. This innovative method became a cultural phenomenon with loyal followers. Until the early 20th century, stereoscopic photographs were a popular form of entertainment and leisure for the rising middle class in Western Europe.

Low cost and easy to reproduce, stereoscopic images became one of the earliest mass media, which would eventually introduce the likes of postcards and, later, the moving image.

Curated by: Kalliopi Valtopoulou, historian-museologist of Photography Museum of the Municipality of Kalamaria “Christos Kalemkeris”. n

WHERE & WHEN: At MOMus – Thessaloniki Museum of Photography (Warehouse A, Pier A, Thessaloniki Port) from October 4th 2024 to February 16th 2025. Before your visit, please check the MOMus website (www.momus.gr) for latest updates.

1961.

Gosznak. Layr Gallery, Βιέννη. Anna Andreeva, design for the scarf “1/2 of the Moon”, 1961. Ink and gouache on special Goznak paper. Layr Gallery, Vienna.

EXHIBITION “COLLECTIVE THREADS: ANNA ANDREEVA AT THE RED ROSE SILK FACTORY”

A fully detailed and documented retrospectiveexhibition on the work and life of Anna Andreeva (1917-2008), the Soviet textile designer who worked in the design collective at the Red Rose Silk Factory in Moscow from the 1940s to the 1980s, is the core narration line of the exhibition under the title “Collective Threads: Anna Andreeva at the Red Rose Silk Factory”.

The exhibition includes Andreeva’s drawings, sketches, and historic fabric samples, as well as photographs, film clips and other documentary materials from the Red Rose Factory collective, Soviet fashion magazines and exhibitions. It is complemented by large-scale contemporary reproductions of Andreeva’s textiles that viewers are invited to touch.

The exhibition presents Andreeva’s work in dialogue with the Russian avant-garde from the Costakis Collection of MOMus – Museum of Modern Art. It includes several textile designs from the 1920s, as well as works of art that inspired industrial design in the early Soviet years, which were saved thanks to the tireless efforts of collector George Costakis.

Curated by: Christina Kiaer, expert in Soviet Art History, professor of Art History, Northwestern University, USA.

Assistant curator: Angeliki Charistou, art historian, MOMus – Museum of Modern Art – Costakis Collection. n

WHERE & WHEN: At MOMus – Museum of Modern Art – Costakis Collection (21 Kolokotroni Str., Moni Lazariston, Thessaloniki) from December 7th 2024 to April 27th 2025. Before your visit, please check the MOMus website (www.momus.gr) for latest updates.

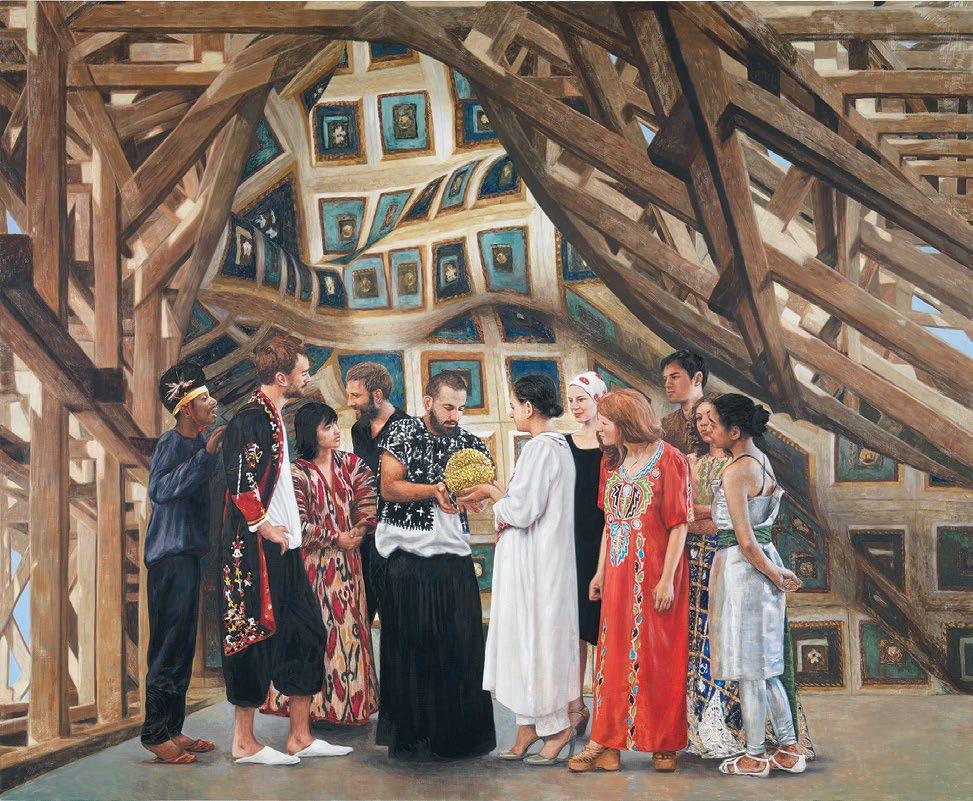

Antje Majewski, «The Donation» (2024), 2009. Λάδι

290×355 εκ. Copyright: Antje Majewski/VG Bild-Kunst, Βόννη 2013. Courtesy: Antje Majewski; neugerriemschneider, Βερολίνο. Antje Majewski, “The Donation” (2024), 2009. Oil on canvas, 290×355 cm. Copyright: Antje Majewski/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2013. Courtesy: Antje Majewski; neugerriemschneider, Berlin.

The exhibition FUTURE PERFECT is organized by the IFA (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen) and includes films, photographs, sculptures, objects, paintings, and collages by sixteen artists living and working in Germany.

The title of the exhibition refers to the tense of the verb that expresses the idea of completing an action in the future: something will have been. From this perspective, the exhibition questions if the future can already be perceived as a finished past. How do artists explore visions of the future and speculations about the course of history, and in what ways can we overcome established and reliable ways of thinking?

The ability to speculate, to name intentions, expectations, and fears, and then to make these the basis for action is what holds societies together. Today, the future is considered a critical concept, even though the near future is hard to predict, despite the rapid pace at which things move in the digital age. The exhibition develops reflections on the promises the future brings. What positions do the artists take regarding the use of material, form, imagination, plot, or narrative? How do they reconsider the past? Where do they find possibilities for taking action?

Curated by: Angelika Stepken, director of Villa Romana (Florence), and Philipp Ziegler, head of the Curatorial Department at ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. n

WHERE & WHEN: At MOMus – Museum of Contemporary Art (154 Egnatia Av., in the TIF-Helexpo premises, Thessaloniki) from January 23rd to March 30th 2025. Before your visit, please check the MOMus website (www.momus.gr) for latest updates.

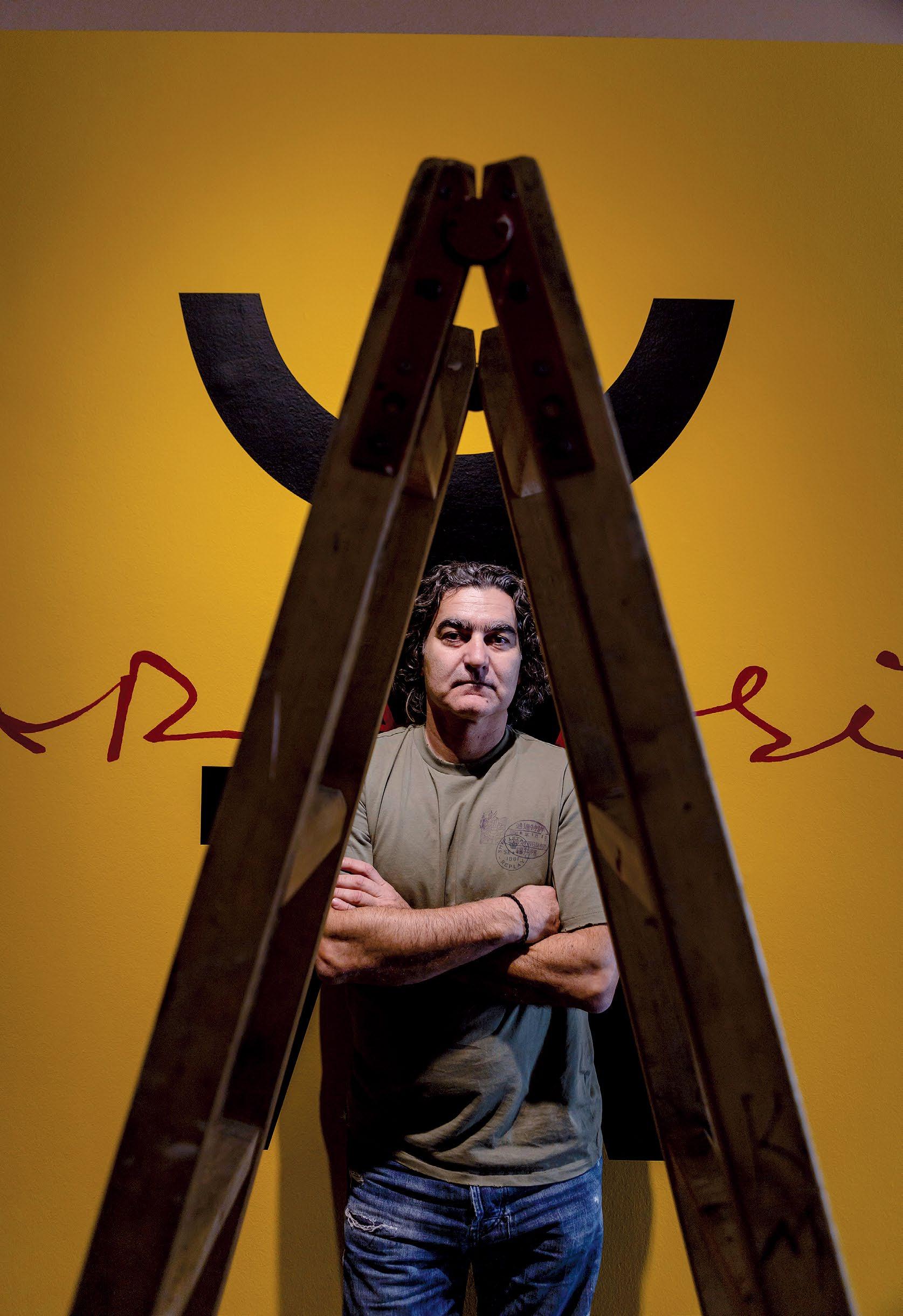

Kostas Kosmidis is a skilled and hands-on electrician and maintenance professional. And, for 23 years, he’s been installing lighting displays for MOMus exhibitions in Greece and internationally. A member of the Thessaloniki Vespa Club, he also appreciates Russian Constructivism.

I was born and bred in Stavroupoli, a suburb of Thessaloniki. My father worked as a foreman and mechanic in a factory producing Italian sanitary ware, and my mother was a nurse at the Psychiatric Hospital. My sister, who was more artistically inclined, pursued singing and painting. I, on the other hand, attended a vocational high school where I studied Electrical Engineering and Automation.

At fourteen, I was recruited by Aris Sports Club. A talent scout spotted me rollerblading at the beachside town of Kallikrateia, where my family and I were vacationing, and decided to approach me with an offer. I played football for five years but eventually stopped after I broke my teeth in an incident. After that, I started working on streetlight installation projects, and in 2001, I was hired by the State Museum of Contemporary Art where I worked as an electrician. Back then, the museums had not yet merged into what we now call MOMus. My responsibilities included the Contemporary Art Centre at the port of Thessaloniki, which today is the Experimental Centre for the Arts. In the early days, there were only a few of us, and we did everything — setting up, carrying, packing. My first exhibition was Vladimir Tatlin’s, held at

“LIGHTING is crucial when presenting art. There are countless subtle variables to consider, such as the MATERIAL, e.g. porcelain or paper, the work’s YEAR OF CREATION, and certainly the ANGLE the artist or curator wants to highlight.”

the port. I wasn’t nervous about that one. My stress level really hit the sky during another port-based exhibition, inaugurated by the then Minister of Culture, Vangelis Venizelos. I was setting up the microphones, and when I turned one on, a ship’s radio broadcast came through. The frequencies weren’t blocked and got mixed up, making the microphones entirely unusable.

I was fortunate to spend my first three years working alongside Professor Yiannis Eliades, an external collaborator responsible for exhibition lighting. He often suggested that I study the lighting used in shoe and clothing shop window displays around the city. This is what sparked my passion for lighting. Lighting is crucial when presenting art. There are countless subtle variables to consider, such as the material, e.g. porcelain or paper, the work’s year of creation, and certainly the angle the artist or curator wants to highlight.

Safety is also critical to ensure the artwork is protected from potential damage caused by excessive light exposure. Ultimately, the primary goal remains the same: to captivate the viewer and draw them closer to the creator’s physical work.

To date, I’ve been involved in over five hundred exhibitions, both in Greece and internationally. I’ve learned to appreciate diversity, creativity and have developed the patience needed to collaborate effectively with artists. Over time, we’ve built mutual understanding and trust, while striving to find the right balance. Many of them have become close friends, including Giorgos Tserionis and Leda Papaconstantinou. I remember Leda’s incredible projection work, which I believe was part of the 2nd Biennale. Using three projectors, we installed her artwork onto waterproof sails, floating above water. Bienniales are a major undertaking for us. Not only are they demanding — they also spread across several locations.

For the museum, I’ve had the opportunity to travel extensively, although not on my beloved Vespa. One memorable experience was setting up the MOMus pavilion in Frankfurt four years ago at Germany’s largest book fair. After 23 years, the memories are countless and impossible to capture in a few words. I can’t recall them all. What I can say for sure is that I feel fulfilled and happy.

My favorite work? “Construction in White” or “Robot” (1920) by Alexander Rodchenko, from the Costakis Collection. I’ve seen it countless times, yet every time it feels remarkably avant-garde to me. n

In October 2018, only one month before the law establishing the Metropolitan Organisation of Museums of Visual Arts of Thessaloniki – MOMus was enacted, the State Museum of Contemporary Art hosted a landmark exhibition of the Costakis Collection at the Sakip Sabanci Museum in Istanbul.

The Sakıp Sabancı Museum is a model of excellence, renowned for its exceptional architecture, planning, and the dedicated team that maintains its status as a cultural powerhouse in Istanbul. We were preparing to present Turkey’s first comprehensive exhibition on the Russian Avant-Garde, working closely with the museum’s highly cultivated and forward-thinking Director, Nazan Ölçer, to meticulously plan every detail: the selection of works, thematic sections, collaborators, and the catalog.

A few weeks before the opening, Nazan shared with me that Yiannis Boutaris was an old and dear friend of hers, and she hoped to invite him to the event, trusting he could make the time to attend. We reached out to him immediately. Boutaris was genuinely delighted, more so by reconnecting with Nazan than by the invitation itself.

In short, he immediately said “yes”. Boutaris flew in for less than twenty-four hours, and Nazan treated the entire Greek and Turkish team to kebabs at the best restaurant in the city. During the meal, someone from the Turkish team, aware of Yiannis Boutaris’ reputation and work in Thessaloniki, jokingly said, “We want you as mayor of Istanbul.” Boutaris laughed and replied, “No, there’s no way. I really like Istanbul, but it’s too big. A different scale entirely.”

At the exhibition opening, Boutaris leaned in and whispered in my ear, “So, all these works belong to us?” I replied, “Yes, and these only make up a fifth of the collection, albeit they are some of the most significant pieces.” He listened intently throughout the tour. It became clear to me that while he was aware of the Costakis Collection’s existence, it was only in Istanbul that he truly grasped its immense value and the importance of having it managed by a museum in Thessaloniki. He was, of course, very happy to have reunited with his friend, Nazan Ölçer. He expressed a strong willingness to collaborate, even suggesting the Yeni Mosque as a venue for exhibitions featuring the Sakip Sabanci Museum’s exceptional collections. Although both parties agreed, the collaboration never came to fruition. A few months later, municipal elections took place, and Boutaris was not a candidate.

As he was leaving, he turned to me and said, “Let me know about what you do with the Costakis Collection” as if, for the first time, he realized that something he had known existed held far greater value than he had initially thought. It wasn’t just the economic value, rather its historical and aesthetic significance that adds cultural value to Thessaloniki. He then took the tie featuring a design by artist Knenia Ender (from the early 1920s) and put it on.

Since then, every time we’d cross paths, he’d ask if we were planning exhibitions abroad and suggested, “Why not bring the art world to Thessaloniki, rather than just taking the collection abroad?” He was absolutely right and this is the direction we’re moving towards: establishing Thessaloniki as Greece’s foremost city for contemporary culture. We have the resources, and sometimes it takes a revelation—like the one Boutaris experienced in Istanbul—to truly recognize the potential. n

Above, left: Yiannis Boutaris pictured alongside Nazan Ölçer, Director of the Sakip Sabanci Museum.

Above, right: Yiannis Boutaris at the opening of the “Costakis Collection: Drawing the Future. Drawings on art, architecture and design” exhibition, sporting a patterned tie inspired by a Ksenia Ender design, a piece from the Costakis Collection. Αριστερά:

Κολλάζ, 1924-26. MOMus

On the left: Ksenia Ender, “Untitled” (decorative pattern), Collage, 1924–1926. From the Costakis Collection, MOMus – Museum of Modern Art.

Επάνω:

2018). Above: a snapshot of the exhibition “Costakis Collection: Drawing the Future. Drawings on art, architecture and design”, held at the Sakip Sabanci Museum in Istanbul, October 2018.

Can roses inspire a Soviet designer at the height of her career from the 1940s to 1980s— and a Hong Kong-born, London-based designer crowned as Global Fashion Icon of the Year in 2022? Reality answers with a categorical “yes.”

Andreeva’s core narrative on display: The “Collective Threads: Anna Andreeva at the Red Rose Silk Factory” retrospective exhibition will document the life and work of Anna Andreeva (1917-2008), the Soviet textile designer celebrated for her Red Rose Silk Factory design collective in Moscow from the 1940s to the 1980s.

Curated by Christina Kiaer, the exhibition will run from December 7, 2024, to April 27, 2025, at the MOMus–Museum of Modern Art–Costakis Collection in Thessaloniki, Greece.

The Red Rose Silk Factory, named after the German revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, served as the meeting point for a female design collective that shaped the fashion and material culture of late Socialism. The exhibition showcases Anna Andreeva’s abstract, geometric, cosmic, space-age, and cybernetic patterns, putting the spotlight on her individual talent whose inventiveness often soared above the work of her comrades. It also explores how Andreeva navigated around the censorships imposed by Party authorities at the time.

The exhibition portrays Andreeva as a successful and enthusiastic contributor to the Soviet Union’s planned economy during the Cold War. It also features her designs inspired by popular, traditional and patriotic themes, alongside her state commissioned works to commemorate historic events, such as Yuri Gagarin’s first manned spaceflight in 1961 and the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympics.

On display: Andreeva’s drawings, sketches, and historic fabric samples, together with photographs, film clips and other archives from the Red Rose Factory collective, Soviet fashion magazines and past exhibitions. Finally, visitors are invited to touch large-scale contemporary reproductions of Andreeva’s textiles. n

«New Year’s», 1961. ANNA ANDREEVA, sketch for shawl with red roses and film strip border, titled “New Year’s”, 1961.

Haute Couture et de la Mode.

Haute Couture Week

Robert Wun is a London-based fashion label that presents storytelling collections through modern artistry and craftsmanship, exploring narratives of visibility and liberation in fashion.

Born in Hong Kong, Robert was discovered by Joyce Boutique after showcasing his graduate collection at the London College of Fashion in 2012. After 2 years working as a freelance designer, Robert launched his own label in 2014, focusing on custom-made collections, with a fresh take on shoes and accessories, and unique tailoring inspired by the worlds of cinema and nature.

The brand made its runway debut in Paris in January 2023, with the support of Bruno Pavlovsky at Chanel. Robert became the first designer from Hong Kong to be included in the Haute Couture Calendar and is also a Guest Designer at The Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode. His Spring/Summer 2023 Couture collection made the closing show of the official Haute Couture Week.

Robert was awarded the Grand Prix at the ANDAM Fashion Awards 2022. In 2023, he was recognized as one of the most influential figures in the fashion industry by both Vogue Business 100 and Tatler Asia. Having dressed artists like Beyoncé, Celine Dion, Lady Gaga, Adele, Cardi B, Florence Pugh and Billy Porter, the designer went on to be commissioned by The Royal Ballet, the Hunger Games Movie Series and Director Wong Kar Wai. n

If you could invite a famous artist to dinner, with a top chef preparing the menu, who would you choose? And what would you serve? In this issue, MOMus “invites” Russian artist and writer Nikita Alekseev (1953-2021) to dinner, drawing inspiration from his artwork “Tomato” (1953), and taps into the creative imagination of Sotiris Evaggelou, executive chef of the Makedonia Palace hotel, to prepare the menu.

Δράσεις», που πραγματοποίησε περισσότερες από 120 δράσεις, και ένας από τους διοργανωτές του Αρχείου Νέας Τέχνης Μό -

σχας. Το 1982 ίδρυσε στο διαμέ-

ρισμά του στη Μόσχα τη γκαλερί «ΑΡΤART», όπου πραγματοποιήθηκαν καινοτόμες καλλιτεχνικές δράσεις. Από το 1987 έως το 1993 έζησε στη Γαλλία.

Nikita Alexeev was an artist and author born in Moscow. He studied at the Institute of Graphic Arts and, from a young age, became interested in contemporary Western art, modern poetry, emerging trends in visual arts, and music. He quickly became a part of Moscow’s circle of conceptual artists. He was a founding member of the “Collective Actions” group, which organized over 120 actions, and was one of the organizers of the Archive of New Art in Moscow. In 1982, he established the “ARTART” gallery in his Moscow apartment, which served as a venue for innovative artistic activities. From 1987 to 1993, he lived in France. Throughout his career, Nikita Alexeev published articles, essays, and his memoirs in books, as well as in print and online media. n

Δωρεά του καλλιτέχνη. Περισσότερα εδώ: https://www.momus.gr/collections

Η ενότητα «Πλατωνικός Έρως» παραπέμπει στο Συμπόσιο του Πλάτωνα και τις νεοπλατωνικές θεωρίες για το «Είδος» ως το

πρότυπο του συνόλου των σκέψεων, των εννοιών, των πραγμάτων και της αντανάκλασής τους. Μιας αντανάκλασης, η οποία εμφανίζεται ελλιπής και βυθίζεται

ολοένα και βαθύτερα στο τέλμα

του υλικού κόσμου, υποφέρει και

επιδιώκει να ενωθεί εκ νέου με το πλήρωμα του «Είδους». Με τον τρόπο

αυτό προκύπτει ο «Πλατωνικός Έρως». Ο καλλιτέχνης επιλέγει διάφορα ζεύγη αντικειμένων για να απεικονίσει αυτήν τη θεωρία, τα οποία χωρίζονται σε τρεις

of Contemporary Art MCA.SMCA.C329.

Donation of the artist. For more: https://www.momus.gr/en/collections

The section titled “Platonic Eros” refers to Plato’s Symposium and the Neoplatonic theories about the “Form” as the archetype of all thoughts, concepts, things, and their reflections. This reflection, which appears incomplete and sinks deeper into the abyss of the material world, suffers and seeks to reunite with the fullness of the “Form”. This process gives rise to “Platonic Eros”. The artist selects various pairs of objects to illustrate this theory, categorizing them into three groups: the natural (stone, seashell, branch, tomato, carrot), the utilitarian (knife, fork, spoon), and the personal (toothbrush, wallet, key). Thus, during their presentation, there are two identical painted objects, in this particular case, two designs featuring a tomato. Between this pair of designs, the supposed “Form” of them is physically suspended, which is represented as an actual tomato. n

When I first saw the painting with the tomato, I thought of creating a dish with different types of tomatoes in various compositions. However, after learning about the artist’s emotionally vested personal exploration of the relationship between the signifier and the signified, I decided to prepare a dish that is purely Greek –considering that in Greece the signifier and the signified are one and the same. n

Εκτέλεση Instructions

1

600

2

2

2

1 sea bass, approx. 1,300 g

600 g spinach

600 g Swiss chard

2 bunches nettles

2 bunches Mediterranean hartwort

2 bunches garden chervil

3 ripe tomatoes, chopped

4-5 shallots, peeled

100 ml olive oil

Zest of lemon

Salt, pepper

Bake for about 25 minutes. n Υλικά (για 4 άτομα) Ingredients (serves 4)

Καθαρίζουμε

και τα στραγγίζουμε σε μεγάλο τρυπητό.

Σε ένα ταψί

Rinse the herbs thoroughly, then drain in a large colander.

In a baking dish, add the olive oil, chopped spring onions and shallots and heat until they soften.

Add the tomatoes and cook until they begin to wilt. Then stir in the herbs.

Keep stirring until the mixture develops a shiny appearance, and finally place the fish on top.

Season with salt and pepper, add lemon zest, and cover the dish with a damp piece of parchment paper.

Stereoscopy at MOMus – Thessaloniki Museum of Photography features works from the photography collection of the Municipal Photography Museum of Kalamaria

“Christos Kalemkeris.” Curated by Kalliopi Valtopoulou, the exhibition gives the audience an opportunity to explore original stereographs and stereoscopes, reviving a once-forgotten photographic technique.

KEIMENO/ΤΕΧΤ

Papaioannou, curator, MOMus – Thessaloniki Museum of Photography.

Stereoscopy, one of the earliest technological innovations in 19th-century photography, remains relatively unfamiliar to the general public. Introduced in 1850 by British scientist Sir David Brewster, following the unsuccessful attempts of Charles Wheatstone in 1832, the technique uses pairs of photographs taken 6–7 cm apart – the approximate distance between human eyes. When viewed through a stereoscope, a device designed to ensure the left eye sees only the left image and the right eye only the right, these paired images combined produce the illusion of three-dimensional depth.

Stereoscopy was a revolutionary innovation in the rapidly industrializing 19th century where photography would become a technical medium of modern culture. The exhibition Stereoscopy, featuring works from the Municipal Photography Museum of Kalamaria “Christos Kalemkeris” and curated by Kalliopi Valtopoulou, will be on view at MOMus – Thessaloniki Museum of Photography from October 2024 to February 2025. It offers visitors a rare chance to discover original stereographs and stereoscopes, with the aim to trigger interest in this now-forgotten technique. The exhibition also examines how stereoscopy was practiced in Greece between 1850 and 1920, as revealed through numerous examples. Stereoscopy had reached Greece via foreign photographers and travellers, who initially set out to captured important monuments and landmarks. These photographs were intended for so-called “armchair tourists” to experience the world at a distance through photography. This period also coincided with the height of co -

lonialism, during which photography became a tool for documenting, categorizing, and ultimately exerting control over the world. It also catered to a growing Proto Tourism movement and played a key role in the rise of the visual encyclopedism. This trend gradually led to the exhaustive consumption of the world through images, a process both spectacular and deceptively painless.

It would be a mistake to assume that stereography was confined solely to the landscapes of distant lands. In reality its scope was much broader, including subjects such as architecture, astronomy, advertising, industry, medicine, archeology, geology, zoology, wars, prisons, technological advancements, celebrities, theater, and sports, just to name of a few of its many conventional and imaginative themes. Meanwhile, erotic and pornographic imagery would also carve out a niche in the latter half of the 19th century. In the age of Victorian austerity, an age marked by high collars and long skirts

a clandestine trade in pornographic images quietly thrived on the side, where the illusion of three-dimensionality seemed to heighten the allure of forbidden nudity.

The popularity of stereoscopy was so immense that the London Stereoscopic Company, founded in 1854 by George Swan Nottage, adopted the motto: “No home without a stereoscope.” True to this claim, the company amassed half a million customers within its first two years of operation. Stereoscopy consequently emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as one of the earliest forms of mass media. However, its prominence waned during the interwar period as public attention shifted to illustrated newspapers, magazines, and the captivating allure of cinema.

The widespread interest in stereoscopy nonetheless gave way to the establishment of companies dedicated to producing, processing, and marketing these captivating images. Among the most renowned was the American firm Under-

Exhibition view: Stereoscopy. From the Photography Collection of the Municipal Photography Museum of Kalamaria “Christos Kalemkeris” currently at MOMus – Thessaloniki Museum of Photography (Warehouse A, Pier A, Port of Thessaloniki).

wood & Underwood, which, by the 1890s, was already producing and distributing millions of stereoscopic images.

The 19th century brought many surprises to the large book of the history of photography. With the exception of holography and select 3D films, it wasn’t until much later that the fascination with three-dimensional imagery would reemerge. At the dawn of the 21st century, amidst the rise of the digital era, this fascination is reignited. In an age of panspermia and successive technological revolutions, three-dimensional imagery would once again take center stage in applications like virtual and augmented reality.

The quest to shift from two-dimensional representation and venture into immersive three-dimensional and virtual experiences remains a open. As technology evolves at an unprecedented pace, the future of imagery is unpredictable, with the possibilities of digital exploration continuing to expand and redefine the visual landscape. n

Anna Andreeva’s silk fabrics in dialogue with the Costakis Collection: How Soviet textile art preserved its avant-garde legacy despite the censorship of Socialist Realism.

σχεδια-

υφασμάτων, αντλούσε έμπνευση από την επαναστατική

“Collective Threads: Anna Andreeva at the Red Rose Silk Factory” at MOMus – Museum of Modern Art. The first international retrospective exhibition on the life and work of Anna Andreeva (1917-2008).

The exhibition looks back on the evolution of the textile industry in the Soviet Union following the avant-garde era, and presents the work of Anna Andreeva, a renowned Soviet artist and textile designer at the “Red Rose” silk factory in Moscow from the 1940s to the 1980s. Named after German revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, the factory served as a site of collective female design labor.

Andreeva was a pioneer in textile design, drawing inspiration from the Russian avant-garde revolutionary period. Her focus was on form, line, and color, as well as themes like space exploration, cybernetics, and electricity. Her holistic approach to the production process naturally positioned women as modern individuals deeply connected to the spirit and issues of the era. The exhibition also highlights Andreeva as a dynamic and successful designer during the Cold War, showcasing her later works, which served as tools of cultural diplomacy. These pieces not only reflect the era’s expectations but also commemorate significant events,

The TEXTILE INDUSTRY in pre-revolutionary Russia was among the MOST ADVANCED globally, with over 800 factories operating nationwide. However, following the end of the CIVIL WAR (1918-1921), many factories were SHUT DOWN, and this led to a sharp decline in textile production.

such as cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s first manned space flight in 1961 and the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

The exhibition presents Andreeva’s work in dialogue with avant-garde pieces from the Costakis Collection. Born in Moscow in 1913 to a Greek family, George Costakis became fascinated by the experimental art of the Russian Empire and early 20th-century Soviet Union in 1946 when he first laid eyes on a painting by Olga Rozanova (1886-1918).

He connected with the families, close friends, and acquaintances of the artists, as well as with the surviving artists of the time. Over the course of more than three decades, he meticulously gathered works from the avant-garde period, creating a remarkable collection that preserved this crucial chapter of 20thcentury European art history from destruction and obscurity.

The exhibition features a substantial collection of textile designs from the avant-garde period, alongside works by artists who influenced industrial design in the early Soviet years— masterpieces that were preserved thanks to Costakis’ relentless efforts.

MOMus – Museum of Modern Art showcases a

large collection of works by Andreeva, who, with both boldness and determination, stayed true to the path of artistic experimentation.

The textile industry in pre-revolutionary Russia was among the most advanced globally, with over 800 factories operating nationwide. However, following the end of the Civil War (1918-1921), many factories were shut down, and this led to a sharp decline in textile production.

In 1923, the sector began its recovery thanks to the establishment of a Textile Design and Production department at the VKhUTEMAS Higher Artistic and Technical Studios. The school aimed to upskill artists in new technological techniques, equipping them to apply their creative ideas in industrial environments.

Examples of such artists include Lyubov Popova (1889-1924), Varvara Stepanova (1894-1958), and Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956) who took part in textile design projects. Stepanova, with prior experience in graphic design and having worked in the textile industry, collaborated closely with Popova, whose most dedicated work in textile design took place between 1923 and 1924. During this time, they both contributed systematically to the First State factory. Popova created geometric, often minimalist designs, her primary concern being how these would resonate with Russian working women. She passed away in May 1924 at the age of 35, making her textile designs part of the final creative phase of her life.

In an article about the posthumous exhibition of her work, held in Moscow in 1924–1925, art critic and poet Ivan Aksyonov wrote that, just two days before her untimely death, and despite her tragic hardships, Popova fondly recalled with satisfaction that her fabrics were in high demand among the working class, viewing this as a triumph of new art over the aesthetics of the past. In their obituary for Popova, the editors of LEF (Left Front of the Arts) magazine, with Vladimir Mayakovsky as editor-in-chief, wrote: “Popova was a constructivist-productivist not only in words, but in deed. When she and Stepanova were invited to work at the First State Cotton-Printing factory, no one was happier than she was.”

In 1924, Osip Brik, writer and editor-in-chief of LEF, states: “It is true that artwork, and factory or workshop work, are still separate. The artist is still an alien in the factory. People react suspiciously to him, they do not let him get close. They do not trust him. They cannot understand why he must know the technical processes, why he should have information of a purely industrial nature. His business is to draw, to make drawings—and it is the business of the factory to choose suitable ones from among them and stick them on ready-made manufactures.” Popova and Stepanova aimed to immerse themselves fully in the textile production process, going beyond the conventional role of designers. Rather than merely creating patterns, artists of the new textile industry preferred to immerse themselves in the entire production cycle— from the initial weaving stages up to the final steps of advertising.

Popova aptly remarked that “The era that humanity has entered is an era of industrial development and therefore the organisation of artistic elements must be applied to the design of the material elements of everyday life, i.e. to industry or to socalled production.”

In 1924, Mikhail Matiushin, a professor at the GINKHUK (State Institute of Artistic Culture) in Leningrad (formerly Petersburg, now Saint Petersburg), also focusing on textiles, introduced the concept of integrating organic design into the applied arts. While Moscow-based artists embraced the fusion of art and production as an extension of constructivist principles based on geometric form, avant-garde artists in Leningrad took a different approach, preferring to capture the dynamic, continuous motion of nature. Persistent criticism of metaphysical and theosophical ideas prompted Matiushin to investigate how organic art could be adapted to serve practical, utilitarian purposes.

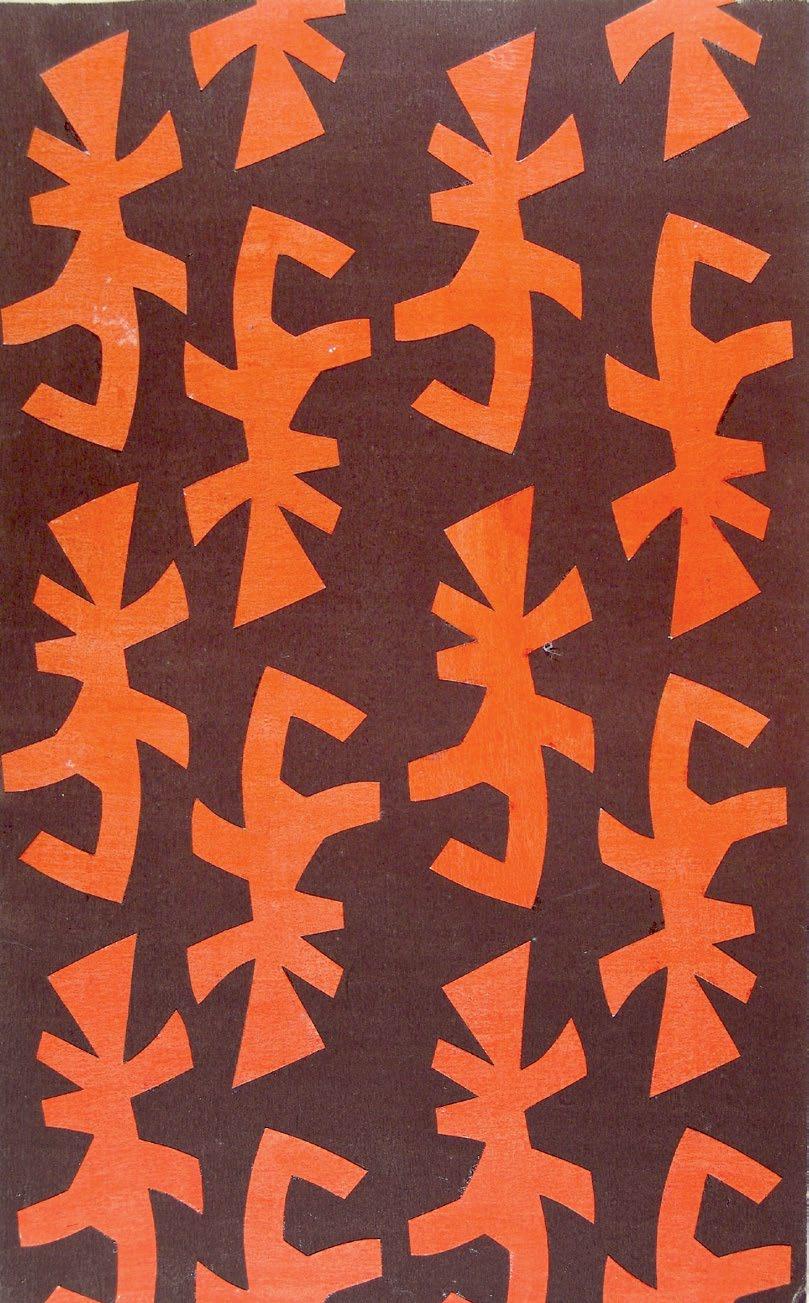

Xenia Ender (1895–1955) was an artist deeply in-

Liubov Popova, textile design, 1923-1924, gouache on paper.

«Sanatoria» (Kurortnaia), 1964(;). Anna Andreeva, textile design “Sanatoria” (Kurortnaia), 1964(?).

1940. Anna Andreeva wearing a blouse made from a pattern she designed. Late 1940s.

1970. Below: Anna Andreeva, fabric “Molecules». Silk textile, printed 1970.

spired by nature. In the 1920s, she served as a research assistant in the Organic Culture Department of the State Institute of Artistic Culture (GINHUK), where she explored spatial experimentation under the guidance of Mikhail Matiushin. In 1924, she exhibited her work at the 14th Venice Biennale. Ender was intrigued by organic forms, colors, and light, portraying nature as a dynamic, everevolving entity. She designed decorative panels and incorporated organic motifs into her patterns, often using collage techniques to create repetitive floral designs. Many of her textile designs are now preserved in the Costakis Collection.

The textile design and constructivist aesthetics of the new era also had a strong influence on fashion design. In contrast, during the Belle Époque (late 1870s–1914), fashion in both the Russian Empire and Europe idealized women as delicate and ethereal, reinforcing this image through clothing styles of the time.

In the 1920s, women in the Soviet Union advocated for gender equality, asserting their right to share equal roles with men in politics, the arts, and the workforce. During this period, avant-garde artists, both male and female, aimed to integrate art into everyday life. This vision extended to clothing design, where new styles and innovations in textile design emerged together. Garments featured clean geometric forms and utilized simple, durable materials, prioritizing practicality and comfort over luxury. Latvian artist Gustavs Klučis created clothing tailored for workers

On the right: Liubov Popova, costume design for “The Magnanimous Cuckold” (translated by Ivan Aksenov), directed by Vsevolod Meyerhold. GosTIM, 1922, photograph, 11,9x8,8cm. The costume was initially created as clothes for the actors of the studio and later used in a play. @MOMus – Museum of Modern Art – Costakis Collection.

and athletes, while Russian artist Varvara Stepanova specialized in designing sportswear. Russian-born Alexander Rodchenko developed new principles to improve the functionality of workwear, and Russian artist Lyubov Popova designed rehearsal costumes for actors, prioritizing freedom of movement. Ukrainian-born artist Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953) designed practical, lightweight, yet warm clothing specifically for outdoor workers. Similarly, Ukrainian Alexandra Ekster (1882–1949) and Lyubov Popova created garments that blended femininity with practicality and ease of movement. Russian designer Nadezhda Lamanova focused on functional attire for everyday life, including workwear for both indoor and outdoor labor as well as sports activities. Constructivism marked a transformative era in fashion history, leaving a lasting impact on how fashion and design are understood today.

The exhibition was organized in partnership with the Andreeva Estate in Basel and the Layr Gallery in Vienna. It is curated by Christina Kiaer, a renowned expert in Soviet art history and a professor of art history at Northwestern University in Chicago. n

(Excerpts from Maria Tsantsanoglou’s text in the bilingual catalogue “Collective Threads: Anna Andreeva at the Red Rose Silk Factory”).

MOMus – Thessaloniki Museum of Photography visits the Corinthian hinterland and invites both locals and visitors to explore the impact of human activity on nature, and reflect on how we, humans, influence the urban, social, and ecological environment.

Raising environmental awareness and advancing dialogue on the challenges and needs for our planet’s future are a central focus here at MOMus. In this direction, and seeing the environment from all its angles, a team at MOMus – Thessaloniki Museum of Photography in cooperation with the Municipality of Sikyonia, Corinth created an interactive educational program featuring a photography exhibition, learning resources, and a digital app. Uni-ting photography and environmental awareness under a common lens, this program extends its reach beyond the museum’s walls.

As part of this effort, Maria Kokorotskou (museologist, theatre/drama teacher and education curator at MOMus), Maria Kehagioglou (political scientist and museologist), and photographer Antonis Vlachos visited the Corinthian hinterland this past October. Their destination was the picturesque village of Mosia in the municipality of Sikyonia, tucked at an altitude of 800 meters on the western slopes of Mount Gerontios. At the local school, the team received a hospitable welcome as they introduced EcoFrames – PhotoGames, an educational activity giving students from the region the opportunity to discuss environmental issues, using photographic works from the museum’s archive, currently displayed at the school.

Over three days, students of all levels across Corinth participated in interactive and experiential sessions, using QR codes and specially designed learning resources. Delivered in collaboration with the municipality of Sikyonia, Corinth, the program also welcomes residents and visitors. Open to the public free of charge on weekends until April 27 2025, EcoFrames – PhotoGames invites its audience to explore themes of the natural and social environment through the art of photography. As we wrestle with climate crises, social isolation, and a weakening connection to nature, this initiative is profoundly relevant.

Its debut in a remote mountainous region is what makes EcoFrames – PhotoGames stand out, together with an educational program that not only supports the area but also empowers the local community to explore and express their creative potential in fields like photography and sustainability. n

34-year-old visual artist from Thessaloniki, graduate of the School of Fine Arts at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, and a doctoral candidate at the Department of Audio and Visual Arts at Ionian University, Vasilis Alexandrou seeks inspiration in the rapid societal changes of our time.

What is the value of art today?

I believe that the term “value” has become distorted, as it’s often directly tied to profit. In terms of “moral value” we’re living in times where it feels lost and seems to fade further with each new generation. Consider this: 10-15 years ago, there were people in this country who never had to purchase water. It was a free resource with no price tag, something that was always available to drink without question.

In a sense, the value of art lies in its role as a means of communication within society – and thankfully, it doesn’t have a price tag. Surely, there’s the art market, which is driven by profit – and in this regard, as it evolves, we see the very concept of art being distorted. Nevertheless, art remains a powerful language of communication.

What inspires you?

(Smiles). Anyone who embarks on the creative process – and especially after dedicating years to it – identifies a central question they wish to investigate. Something that captivates them, that ignites an “itch.” A concern that arises from society and life itself but becomes that very “catalyst” that drives them to engage in artistic expression.

What is then the central question you explore in your work?

I wish it were that simple. It’s not something I can sum up in a few words. It’s an ongoing discussion, ever evolving,

“Anyone who embarks on the CREATIVE PROCESS – and especially after dedicating years to it – identifies a CENTRAL QUESTION they wish to investigate. Something that captivates them, that IGNITES an ‘ITCH’.’’

much like the changes happening in society which I experience firsthand. These changes are currently a source of concern that I encounter daily. Take this neighborhood we’re in right now (i.e. Olympos Street), where various parades, funerals, and all sorts of national traditions frequently take place. I try to see such events from a different angle, turn them on their head, understand how they function, and how national identities are formed.

What is your favorite material?

Plasticine is an incredible material. However, there comes a point when the material itself is no longer the focus. Personally, I work with whatever materials are available. I don’t have a single favorite. What truly drives me is finding the most conceptually fitting way to express my idea. I use a wide range of materials, from digital media to metal and wood.

What are you currently working on?

I’m preparing several group exhibitions in Athens with friends and collaborators – some from the Ionian University and others with whom I’ve built artistic relationships. One topic that stands out and concerns us deeply is the post-internet era.

In other words, what we’re experiencing today? Or rather soon. I believe we’re currently in a transitional, post-digital phase. The internet has lived through its adolescence phase. People are now turning to each other – something we saw especially during the pandemic, which was likely a pivotal moment. n

She’s someone who treats flânerie as an art for refined living and perhaps sees museums as natural havens that satisfy a refined lifestyle. Journalist, radio producer, and the founder of Thessaloniki Walking Tours, a group dedicated to discovering the city’s cultural routes and public history, Evi Karkiti, meets every expectation.

Given your profession and temperament, you wander around Thessaloniki extensively. When did you first hear about MOMus?

I believe it was in 2018, the year the initiative was launched. This was before the pandemic hit, and swept everyone, globally, off their feet. It felt like a different world back then. But the pandemic also made one thing clear: the pressing need for collaboration, something the post-pandemic future would only confirm as essential. I remember thinking: “this is a risky bet,” and a real challenge for those working on the project in a city that, at the time, lacked (and perhaps still does) a strong culture for cooperation, one that’s built on shared skills, and a common vision.

Do you remember your first visit to a MOMus museum, either in Thessaloniki or Athens?

What impression did it leave on you?

If I’m not mistaken, I had visited the former State Museum of Modern Art that was hosting a temporary exhibition on the Costakis Collection titled “Restart.” It was a powerful experience—not only because it revealed Costakis’ dedication and

“We love to think that BEAUTY can save the world, this idea of an ALTERNATE REALITY DEEPLY ROOTED in the human condition.”

determination to rescue significant artists from obscurity, but also for offering a glimpse into that fine, blurred line where the world shifts, often unnoticed, before our eyes.

Something else that struck me was how the visitor could sense not only the “dialogue” between Avant-garde artists of visual creation and other art forms—a fascinating area in and of itself—but also the profound influence that scientific innovations at the time had on these creators.

Like many cultural journalists, I followed the journey of the Costakis Collection until it finally made it to Thessaloniki, and I’ll always remember Bruce Chatwin’s book, What Am I Doing Here, because that’s where I first learned about Costakis. Chatwin had heard of him and decided to visit him in Moscow. He entered what seemed to be an ordinary apartment, only to discover it was, in fact, a museum of modern art, revealing a neglected, captivating, and sometimes harsh story.

How easily can modern art be appreciated and understood in a country with such deep roots in classical art traditions?

I get the sense that we’re not doing too badly, although I might be wrong. Over the past two decades, we Greeks have travelled widely. We’ve visited some of the world’s greatest museums, and experienced firsthand the iconic works of the most influential artists of the 20th century. Not to mention that museums in Greece have also played their part, providing food for thought for those willing to explore further. But even for those who weren’t actively seeking, a window may have opened. And while a connection might not have immediately formed, perhaps they found a thread that eventually will draw them in.

Regardless, modern art compels us to repeatedly ask the same question when standing opposite an enigmatic, incomprehensible, and provocative piece: What is art, and what

are, if any, its limits? It’s a great conversation to have because it’s always open and continuously evolving. Thankfully there’s never a conclusion. I also get the sense that these very discomforts can sometimes create a work that becomes, for lack of better words, a classic. As we stand looking at a sculpture of well-known prestige, beauty, and harmony, it confuses us, or sparks thoughts that would have never occurred to us. This can surely happen. True, such works, often make us feel safer, as if we’ve discovered real art—something that, in theory, should elevate us. However, how artwork—whether classical, modern, or contemporary—affects each one of us is a different matter entirely. It’s an intellectual journey with no rules, or boundaries.

What is the definition of a museum today?

And to give an answer to a common concern, how can museums adapt to the current demand for greater outward engagement and visibility?

What is the definition of a museum today? That’s a hard question to answer. Fortunately, there are experts who can. It’s clear that a museum should leave a cultural mark on the city it’s located in. It should contribute to the production of culture and support education. It should be accessible to all, with easy access for anyone who wishes to visit. A place that takes a stance on the pressing issues of the time, that collaborates with similar museums in other cities, that finds ways to surprise us. Each museum, through

“Each MUSEUM, through its permanent collections, tells a STORY and conveys its unique NARRATIVE.”

its permanent collections and identity, tells a story and conveys its unique narrative. It invites us into a world as seen through its own lens.

I suppose that in a world as fluid and ever-changing as ours, “ruptures” or different interpretations of a narrative will emerge and that’s inevitable. It’s essential that cultural institutions, like museums, do not remain stagnant. Generating doubt and constant reflection may, in fact, be the whole point. In today’s world, we can’t afford to stand still, that’s for sure. Each day requests that we learn more. Maybe each day offers us a chance to make sense of it all. I think this applies to everyone—individuals and museums alike. After all, museums are the places that showcase human adventure, ingenuity, and creativity. And they’re meant to draw people in.

Dostoyevsky wrote in The Idiot: “Beauty will save the world.” In this sense, can art, as a more tangible form of beauty, save us too? And in our fast-paced modern lives, is there space for it?

We love to think that beauty can save the world, this idea of an alternate reality deeply rooted in the human condition. Beauty is something of an ongoing reminder that there is harmony in the world, and from which spiritual upliftment thrives. I would lean towards the approach of Umberto Eco, a Renaissance man of the 20th century, who, in two of his books, explores both the history of beauty and the history of ugliness. Both are integral to the world, and to art. Perhaps they complement each other, seeing as they offer a fascinating exploration of human perceptions, desires, fears, and contradictions—capable, with equal power, of saving or destroying the world. n

Discover gifts inspired by some of the most iconic artists of our time. Imaginative, practical, and effortlessly stylish. At the MOMus gift shop, you’ll find everything you need to spoil your loved ones (and also treat yourself).

AVANT CARD. Top Trumps Card Game: “Avant Card: A game about the art of the Russian Avant-Garde.” Card game based on artwork from the Costakis Collection. 52 cards. Age: 5+. 2-4 Players.

This educational book, designed for children, parents, and teachers, offers engaging activities and tools that unfold the story behind the artworks of the Russian Avant-Garde. It also includes a glossary to explain key concepts. Suitable for all ages. Children aged 5–7 are encouraged to enjoy the book alongside an adult.

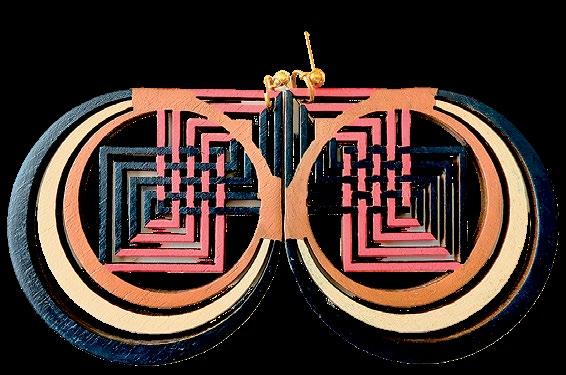

LYUBOV POPOVA EARRINGS. Handmade wooden earrings, laser cut. Ιnspired by the Constructivist movement and Lyubov Popova’s artwork “Drawing for Fabric.”

BY ILIAS SIPSAS. Internal print on a custom plexiglass structure with artwork by Ilias Sipsas’ “I Know Everything,” from the exhibition “Syzygy. Solid Light & Timeless Motion” at MOMus – Alex Mylonas Museum.

IOLAS SILK SCARF. Made from premium-quality silk, this scarf is the product of a collaboration between the Mantility Silk Scarves Gallery and Tsiakiris Silkhouse in Soufli. Its design is an exclusive creation by Mantility, and draws inspiration from archival materials in the Alexandros Iolas collection at the MOMus – Museum of Contemporary Art.

“FROM NOW ON” CATALOG. This bilingual catalog accompanies the namesake exhibition at MOMus – Museum of Contemporary Art.

(PhotoBiennale

PHOTOBIENNALE CATALOG. The bilingual catalog for the main exhibition of PHB23 (PhotoBiennale 2023), titled “The Spectre of the People,”.

SCRUNCHIE. Αξεσουάρ

(1924-26)

SCRUNCHIE. This oversized scrunchie, inspired by Xenia Ender’s Untitled (1924–26) from the Costakis Collection at MOMus – Museum of Modern Art, is made from cotton fabric with a satin texture.

IVAN KLIUN’S PLEXIGLASS ARTWORK. Featuring an internal print of Ivan Kliun’s Red Light. Spherical Structure (1923) in a specially designed plexiglass structure.

CUFF BRACELET. Plexiglass cuff bracelet by designer Structivi. Laser-cut, features key characteristics of the Costakis Collection’s Russian avant-garde works at MOMus – Museum of Modern Art. Statement piece with a minimalist yet dynamic design.

KLIUN SILK SCARF. Made from premium silk in collaboration with the Tsiakiris Silk House in Soufli, it’s inspired by Ivan Kliun’s Suprematist Composition from the Costakis Collection.