Editorial

Welcome back to the new school term. I hope all of you had the opportunity to rest and recharge during the June holidays.

The year 2020 was a year that saw great shifts in the way we taught, learnt, and assessed teaching and learning. Some might say we had to redefine what going to school meant. The pandemic forced us to move out of our comfort zones and into a seemingly brand-new world of e-pedagogy, new technology, and new jargons. Before long, terms such a ‘flipped classrooms’, ‘asynchronous’, ‘synchronous’, breakout rooms’, etc. were part of our normal conversations. It also brought about the acceleration of the adoption of personal learning devices (PLDs) for the secondary and JC/CI students. E-pedagogy, in actual fact, has been creeping into and gaining traction in our education landscape even before the pandemic struck. It has been identified as one of the 6 areas of practice in SkillsFuture for Educators (SFEd).

In this issue, we continue to share our learning gleaned from 2020, especially in e-pedagogy. In “Creating Effective Videos for Teaching and Feedback”, Mr Desmond Seah and Ms Tan Mei Hui share their learning in using and creating videos in their lessons and in providing feedback. We explore the world of blended learning, in particular, the use of flippedclassroom in “Blended Learning: Blending the Best of Both Worlds”.

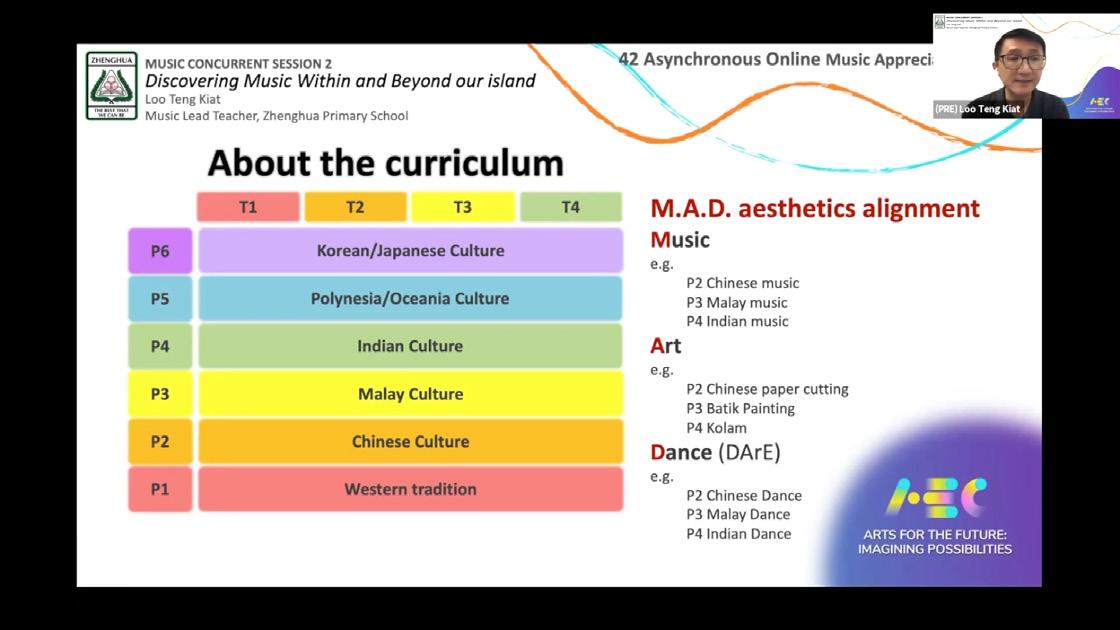

In our continuing series, Musical Conversations, Lead Teacher Mr Loo Teng Kiat shares his journey as a teacher-leader and his experiences teaching music, especially during a pandemic.

We are excited to introduce a new segment, “Tips & Tools for Music Educators”, to you. As we become more familiar with technology and explore more ICT tools and applications in our teaching and learning, little tips that help us navigate the applications go a long way to overcome our hesitations and bumps that we may encounter.

As we begin the new semester, I wish all of you well and hope that you have fun music-making in your classrooms. Take care and stay safe!

Susanna Chau Deputy Director, Music Singapore

Teachers’ Academy for the aRts

Creating Videos for Effective Teaching and Feedback

Guo, Philip & Kim, Juho & Rubin, Rob. (2014). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. 41-50. 10.1145/2556325. 2566239.

Creating Effective Videos for Teaching

Video has become a widely-used technological tool for teaching in both physical and virtual classroom settings. A quick search on online video platforms such as YouTube will reveal vast collections of educational videos across a variety of topics. Yet, the effectiveness of a video in enhancing a student’s learning experience depends on many factors apart from the use of the medium itself.

One important aspect of creating effective teaching videos is to include elements that can help to increase student engagement. In 2014, Philip J. Guo, Juho Kim, and Rob Rubin conducted a study of how video production affected student engagement, analysing data from 6.9 million video watching sessions across four courses on the edX Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) platform.

Adapted from Guo, Kim, and Rubin (2014)’s study on how video production affects student engagement.

Soh P.W. (2020). Designing Differentiated Instruction through Guitar Video Tutorials. In STAR (Ed). Sounding the Teaching IV: Diversity and Inclusion in the Music Classroom. p.158-163.

Findings

• Shorter videos are much more engaging.

• Videos that combine slides with footage of an instructor speaking are more engaging than slides alone.

• Videos produced with a more personal feel could be more engaging than high-fidelity studio recordings.

• Videos where instructors speak fairly fast and with high enthusiasm are more engaging.

Based on their findings, they proposed some recommendations for producers of educational videos.

Closer to home, there have been studies from music teachers on the use of teaching videos. To achieve their intended learning outcomes, some teachers prefer to create their own videos, instead of using existing online videos that may not be entirely suitable for their students, or simply because there are no available resources to tap on. For example, Soh Pei Wen, at Manjusri Secondary School then, conducted a Critical Inquiry study on her selfcreated guitar video tutorials for differentiated instruction. She found that students paused videos for practice or peer coaching, and they chose to watch (and re-watch) certain

Recommendations

• Invest heavily in pre-production lesson planning to segment videos into chunks shorter than six minutes.

• Invest in post-production editing to display the instructor speaking at opportune times in the video.

• Try filming in an informal setting; it might not be necessary to invest in big-budget studio productions.

• Coach instructors to bring out their enthusiasm and reassure that they do not need to purposely slow down.

parts of the videos. Overall, she found that students appreciated the control they had over the pace of learning through these videos. She also found that some students might require more visual cues in the videos and subtitling, whereas others found them distracting. By customising content and delivery to meet their students’ specific needs and preferences, these teachers not only promote a deeper level of engagement with the video, but also help students to develop a richer understanding of key ideas and concepts.

The next section of this article will highlight the experiences of two music teacher-leaders (1 Primary and 1 Secondary), who have created video tutorials for their students.

Creating Videos to Teach a Primary 3 to 4 Recorder Module

Brief

Overview of Desmond’s Primary 3 to 4 Recorder Module

Notes

1. Introduction to the Recorder Parts of the recorder

Music Elements / Instrumental Skill

Good Breath Control/Fingering Techniques through Games

2. Notes B, A, G Kueh Pisang/ Hot Cross Buns Patterns in Music

3. New Note C’ Chorus of Chan Mali Chan

4. New Note D’ Ode to Joy (Ludwig van Beethoven)

5. Composing Activity using G, A, B, C’, D’

6. New Note E Diddle Diddle Dumpling

7. New Note D Crotchet, Quavers, Ties] Swinging Bones (Susie Davies-Splitter & Phil Splitter) Scoo Be Doo (Susie Davies-Splitter & Phil Splitter)

8. New Note C

Burung Kakak Tua Munnaeru Vaalibaa (S. Jesudassan)

By Mr Desmond Seah, HOD (Aesthetics), Jiemin Primary School

Video-Based Learning

Staccato and Legato

Chan Mali Chan (Chorus Only) click to view

Listen Practise Perform

Dotted Crotchet and Quaver Ode to Joy click to view

Listen Practise Practise (slow) Perform (slow) Perform

Improvisation on the Recorder using E and G

Ostinato, Playing in Parts

3/4 Time Signature, Binary Form 4/4 Time Signature, Ternary Form, Syncopation

Burung Kakak Tua click to view Munnaeru Vaalibaa click to view

Listen Practise Practise (slow) Perform (slow) Perform

Listen Practise Practise (slow) Perform (slow) Perform

These

recordings allowed the

teachers to document the students’ musical growth over time and also helped to inspire other students to keep striving for musical excellence.

Students were invited to submit recordings of their performances via Flipgrid, or SLS. Some students even submitted multiple audio or video recordings over a period of time, which showed their determination to improve. As they prepared their recordings, the students were also engaging in selfassessment in terms of note accuracy and tone quality, before deciding whether their work was ready for submission. These recordings allowed the teachers to document the students’ musical growth over time and also helped to inspire other students to keep striving for musical excellence.

I was fortunate to be able to collaborate with my team members, who saw the potential in self-created video tutorials and shared a similar passion and interest in exploring

There were two push-factors for me to start creating and using self-created videos to complement classroom teaching:

1. I had students who were very interested in playing the recorder. They were independently learning popular songs from video tutorials on YouTube, and these songs were more complex than the songs I taught in class.

2. There was a lack of existing recorder-playing video tutorials on Singaporean songs.

Referred to many existing tutorials and noted the positive and negative aspects of these, before conceptualising and creating our videos.

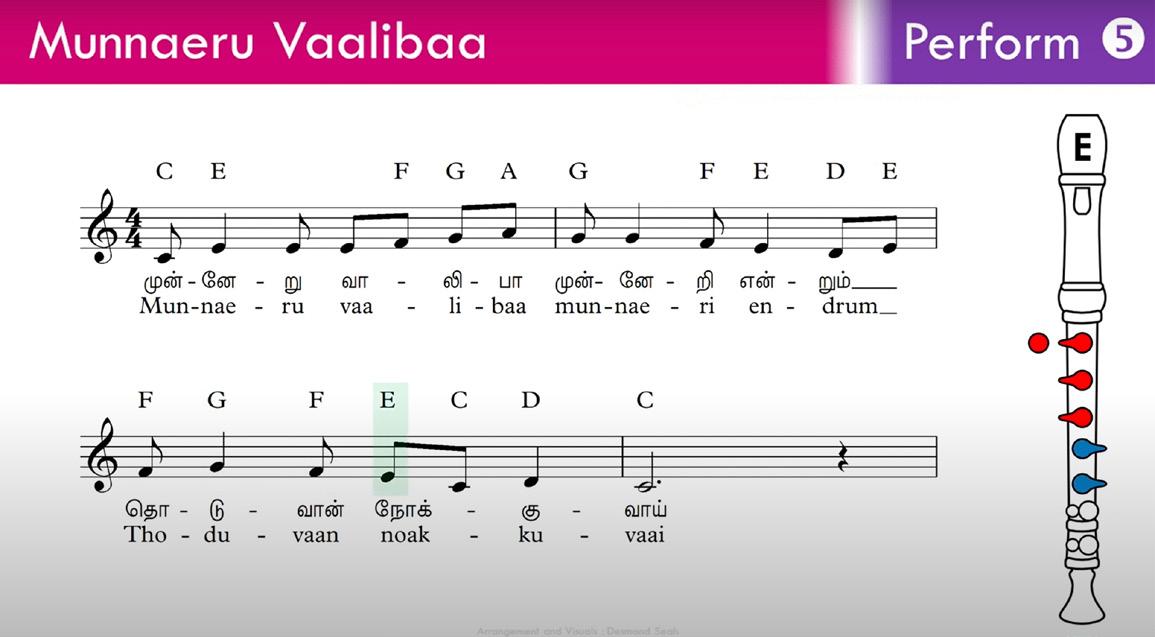

An example of Desmond’s video tutorials for his recorder module

how we could enhance our students’ learning. My colleague, Mr. Joseph Lim, helped to create the audio backing tracks, while I focused on designing the visual elements for the videos. The videos comprised slides for individual musical notes, which I created using Microsoft PowerPoint.

The objective of our video tutorials was to encourage self-directed learning by providing my students with musical guides to practise their instruments in their own time beyond the music classroom. To ensure that these videos would be pedagogically grounded and useful for students, my colleagues and I referred to many existing tutorials and noted the positive and negative aspects of these, before conceptualising and creating our videos.

For instance, the design of the recorder in our videos took on a few different forms. Initially, we experimented with a side-view recorder, before deciding that a front-view recorder would offer greater clarity as a visual guide for accurate fingering. For the practice videos, we segmented each piece into shorter phrases, where students would be prompted to listen to a demonstration of each phrase, before playing that phrase on their recorders immediately after. In determining the appropriate length of each phrase, we also considered the amount of air that a student could typically hold, as well as musical flow.

I felt that my students benefitted from the video tutorials and were more engaged in learning. In fact, many students requested for more of such videos. The tutorials facilitated selfdirected learning and allowed for more effective independent practice outside of music lessons. The aural and visual scaffolds were useful for students who needed additional guidance to visualise the placement of their fingers, refine their produced tone, and adhere to tempo, easing the process for them to translate musical notation into accurate playing.

Features of Desmond’s Video Tutorials

Scaffolding

Inspired by the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model, students would listen to the song and learn by echo playing, followed by independent playing. Students could learn the notes and practise at two speeds: slow and fast.

Content

Inclusion of new pitches and rhythmic values.

Sound

Inclusion of:

• Authentic recorder sounds (not MIDI samples) for students’ reference as they worked on tone production.

• Backing tracks to help students maintain pulse.

Visual

Inclusion of:

• Animated fingerings (red dots for the left hand, blue dots for the right hand, and extensions to symbolise the fingers).

• Animated highlighted notes, synchronised with the rhythm of the melodic part.

• Clean lines and a white background to minimise visual distractions.

Duration

Not more than four minutes per video.

Click here to read about the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model.

Students also had the autonomy to choose the pace best suited for their learning.

Video tutorials also offer greater flexibility and options for teachers in various teaching and learning contexts, beyond that of home-based learning. In a flipped classroom context, such videos could be used to facilitate students’ self-practice, allowing

teachers to use face-to-face time in school to analyse the music and discuss different music elements in greater detail. During in-school music lessons, teachers could tap on the videos to facilitate the musicmaking process, freeing themselves to move around the class to provide immediate support and feedback for students without disrupting the musical flow.

Creating Videos to Teach a Secondary 2 Drumming Module

By Ms Tan Mei Hui, SH (Arts), Hillgrove Secondary School

1 Introduction to the Drum Kit and Building a Basic Drum Groove

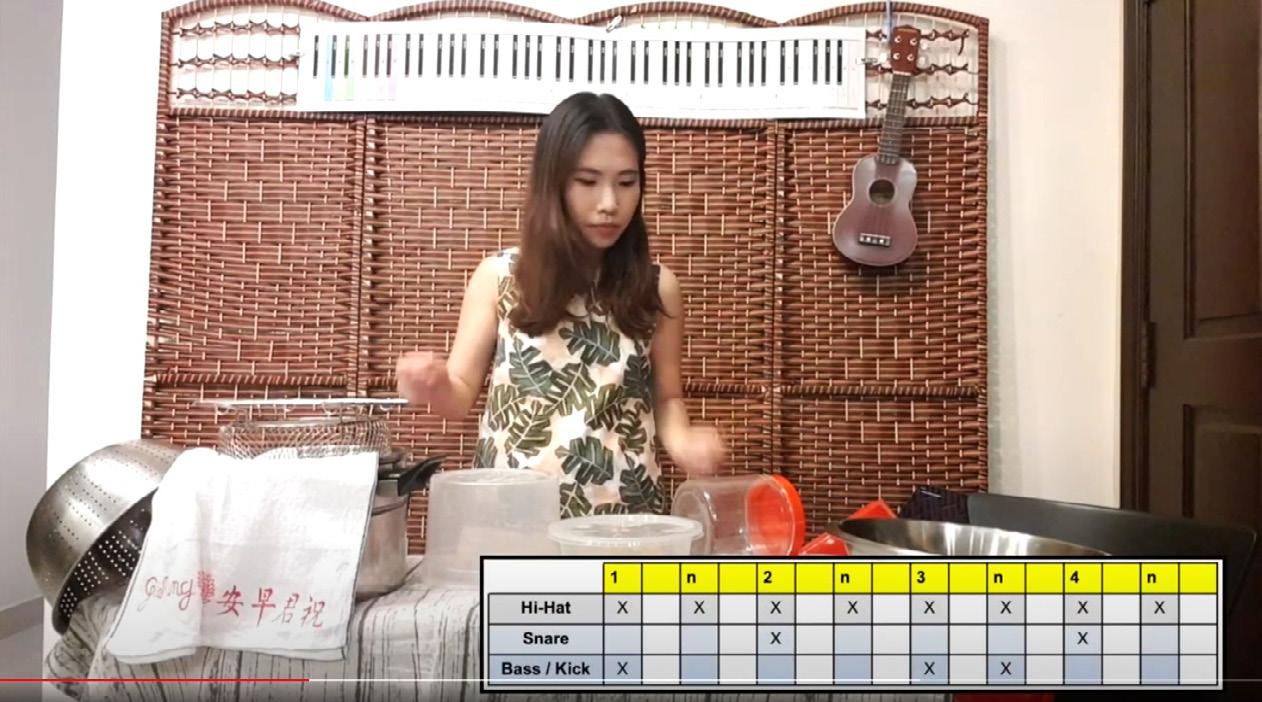

Prior to the Circuit Breaker in April 2020, my students were working on their pop band covers, in preparation for an upcoming Music Festival. However, the Circuit Breaker meant that our plans had to be modified. As part of a 3-part HBL package, I decided to create a series of four video tutorials. Brief Overview of Mei Hui’s Secondary 2 Drumming Module. The videos can be accessed here

2

More Drum Grooves and Rhythms (and a bit about music production)

3 Making your own DIY Drum Kit at Home

3.1 – Video 1

Introduction & recap on parts and sounds of a drum kit

3.2 – Video 2

Assembling your own DIY drum kit at home

3.3 – Video 3

Playing a rock drum groove with a backing track on your DIY drum kit

3.4 – Video 4

Bonus Challenge – Drumming along to an actual song (‘Don’t Stop Believin’)

Some considerations which prompted me to create my videos:

How could I get my students to continue music making while they were isolated at home?

How could their learning be applicable to their Music Festival Pop Band preparations after the Circuit Breaker? (Back then, we were not aware of the eventual implementation of safe management measures, or whether singing would be permitted during music lessons.)

What would be the most accessible mode of music making (e.g. instrument / virtual tool) for all students, regardless of their backgrounds? Was there an alternative that students with no access to actual instruments at home could use?

How could we nurture and instil creativity in students through music, while developing their performing and listening skills at the same time?

Should I (i) source for suitable tutorials on YouTube, or (ii) create my own? While (i) would be less time-consuming, it was not easy to identify existing online tutorials that were concise, effective, and engaging. Although (ii) would require more time and effort, I eventually decided to create my own videos, thinking from the perspective of my 14-year old students before customising my content and delivery for them.

Overarching objectives

Students could continue to engage in instrumental music making individually at home and hone their performing and listening skills.

Students could develop greater sensitivity to sound, rhythm, and timbre.

Students could develop better co-ordination skills.

Students would be able to nurture selfdirectedness, and thus be empowered in the process of learning.

Students would continue to be enthusiastic about learning and discovering new skills and new knowledge about music.

Features of Mei Hui’s Video Tutorials

Intentional Scaffolding and Sequencing

3.1 – Video 1

Introduction & recap on parts and sounds of a drum kit

3.2 – Video 2

Assembling your own DIY drum kit at home

3.3 – Video 3

Playing a rock drum groove with a backing track on your DIY drum kit

3.4 – Video 4

Bonus Challenge – Drumming along to an actual song (‘Don’t Stop Believin’)

Specific learning objectives

Students would be able to identify the different components of the drum kit.

Students would be able to identify the sounds made by the different components of the drum kit.

Students would be able to apply their knowledge to create a DIY (“Do It Yourself”) drum kit at home.

Students would be able to perform a basic rock drum groove via a virtual drum kit as well as a DIY drum kit.

1. In Video 1, I recapped the different sounds of the drum kit by using GarageBand. In doing so, students could develop the auditory discernment and familiarity with the various timbres of the drum kit.

2. Video 2 served as an extension of Video 1, where I explained how to find substitute objects to create a DIY drum kit. The follow-up task would require students to exercise their listening skills and sensitivity to timbre.

4. As I was aware that some students might find the task in Video 3 too simple, I crafted Video 4 as a bonus challenge for students who might be interested to drum along to a rock song.

Scope of Content and Duration of Video

Each video had one key objective, as I wanted to keep the content in each tutorial concise and clear. I also tried to keep the duration of each video to three minutes to avoid “video fatigue”, although two videos were slightly longer to ensure a coherent flow within each video. All videos were designed to be embedded into an SLS lesson, which meant that there were questions that the students had to respond to, or tasks to complete after watching each video.

Presentation Style

Text Overlays: for humour and to bring across the point that it is fine to make mistakes. Even teachers make mistakes!

3. Thereafter, I felt that it would make sense for students to put their DIY drum kit to the test by performing a simple drum groove. Previously, I had taught the drum groove featured in Video 3 in an earlier lesson using virtual drums, which meant that students could build on their prior knowledge and demonstrate their understanding in a new context.

I did not script my videos as I preferred the flexibility of speaking “freestyle”. I tried to keep my delivery fun, cool, bright, and energetic. To achieve this, I referred to numerous videos of popular vloggers and other instrumental tutorials online, and adapted their techniques, such as text overlays, picture-in-picture inserts, and notational diagrams to help students visualise the beats. It took me some time to acquire information, learn, and familiarise myself with these video editing techniques on my chosen software to create my desired graphics.

01 Picture-inPicture

02 Notational Diagrams

I used various strategies to maximise the overall engagement value of my videos. For example, I created an attention-arresting title image that was bright red in colour and incorporated tongue-in-cheek graphics to lighten the mood and set a positive tone for learning to take place. This image was accompanied by an upbeat and cheeky-sounding “hook jingle”, which was intentionally chosen

“Many students found it cool and interesting that they could create something similar to a drum kit at home.”

to capture the students’ auditory attention. I also spent approximately thirty minutes to create an attractive visual backdrop before filming. My video tutorials were well-received by my students. I felt that the video tutorials helped them to process, internalise, and synthesise information better, as they were engaged both aurally and visually. Many students found it cool and interesting that they could create something similar to a drum kit at home. Some were also amused to see their music teacher (me) appear on screen. My sensing was that students would be more inclined to watch a video made by their teacher, compared to one created by a random content creator, due to the stronger personal connection between both parties.

As an optional stretch activity, I invited students to submit video recordings of themselves drumming on their DIY drum kits. While I expected to receive very few, or even no submissions, I was pleasantly surprised to receive a considerable number of submissions from my students.

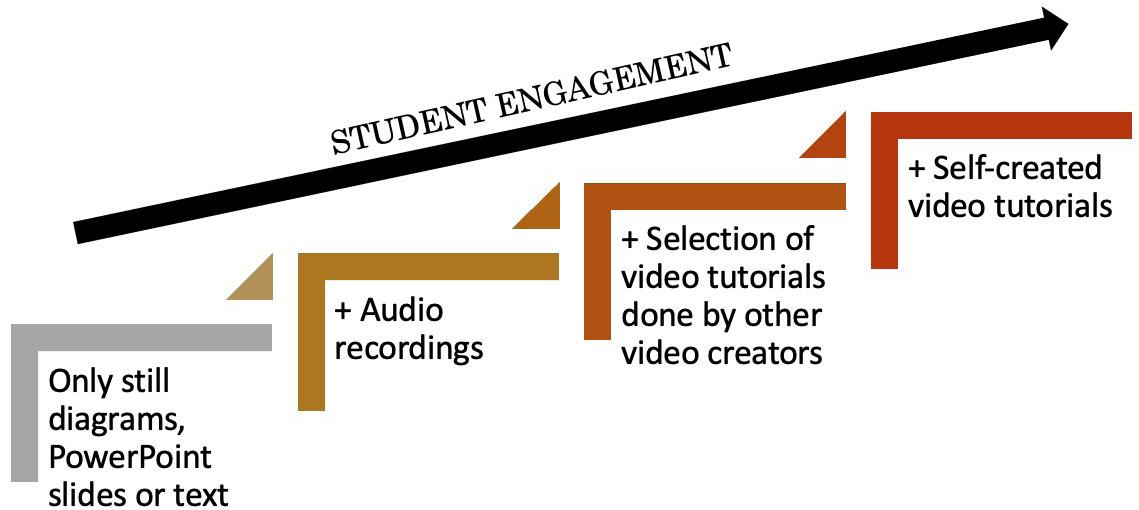

Moving forward, I believe that video tutorials can open up an exciting world of possibilities for music teaching and learning both in and

out of school, even as we continue to seek more ways to facilitate effective and engaging music lessons for our students. For example, teachers might previously adopt some of these common approaches to teach students keyboard skills:

• “Air-play” on a paper keyboard stuck onto the whiteboard (this was the method my first teacher used).

• Connect a visualiser, or phone to project a top view of one’s fingers on a keyboard on a screen.

• Take turns to demonstrate to small groups of students.

Through the use of bite-sized video tutorials, teachers could give all students immediate access to clear demonstrations via their personal learning devices, which all secondary students will own by end-2021,

Mei Hui’s personal observations on student engagement levels vis-à-vis different modes of learning resources

as part of the National Digital Literacy Programme for all schools. Students would also be able to control their viewing experience (e.g. replay, skip) and, thus, manage their pace of learning.

As such, a music lesson employing the use of video tutorials could look like this:

1. Teacher instructs students to access a specific video tutorial.

2. Teacher assigns a certain amount of time for students to complete a task (aided by the video tutorial).

3. Teacher allows students to work individually, or in groups, while he/she moves around to check on students’ progress and assist those facing difficulties.

4. At the end of the allocated time, the teacher addresses the entire class and employs assessment for learning (AfL) strategies to ascertain students’ progress and understanding, before bridging the learning gaps, if any.

Henderson, M. & Phillips, M. (2014). Technology enhanced feedback on assessment. Paper presented at the Australian Computers in Education Conference 2014, Adelaide, SA.

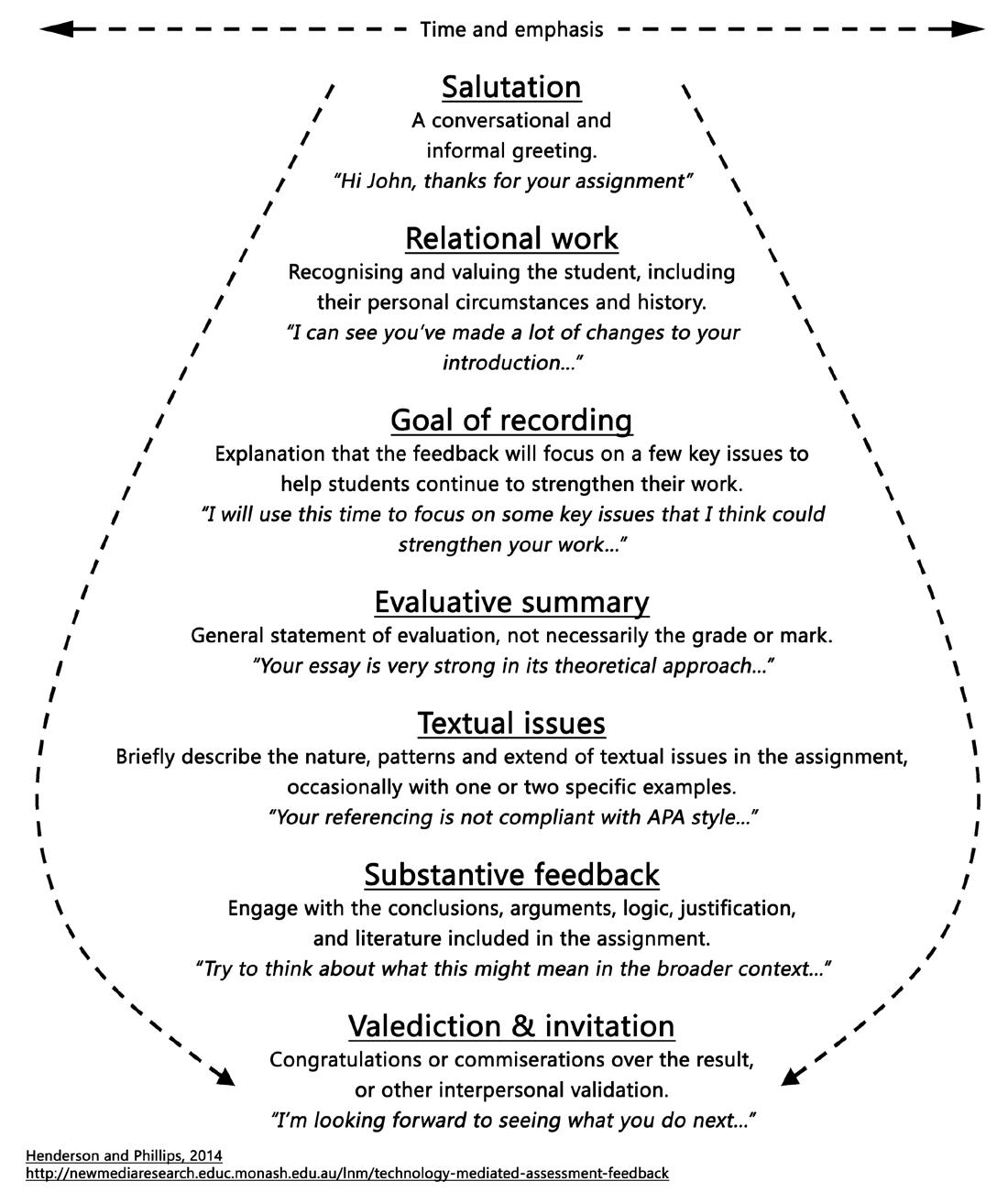

Creating Effective Videos for Feedback

As part of teaching and learning, feedback plays a critical role in determining students’ progress and achievement. Henderson and Phillips (2014) proposed eight guiding principles for effective feedback by teachers:

Principle

1. Be timely

2. Be clear (unambiguous)

3. Be educative (and not just evaluative)

4. Be proportionate to criteria/goals

5. Locate student performance

6. Emphasise task performance

7. [Situate feedback] as an ongoing dialogue rather than an endpoint

8. Be sensitive to the individual

Description

Give feedback while details are still fresh, and in time to assist the student in future task performance.

It is important to be unambiguous in communication. For example, do not assume students have the same understanding of academic language or discourse. Similarly, phrases such as “good work” are unclear, due to the lack of specificity.

Indicating something as incorrect is not as helpful as suggesting how it could be corrected or improved. It is also valuable to focus on strengthening, developing, and extending what has been done well.

More time should be spent providing feedback on the more significant goals of the assessment task.

In relation to:

• The goals of the task (feed-up)

• Clarifying what they did well and not so well (feedback)

• What they can productively work on in the future (feed-forward)

More emphasis should be placed on feed-forward.

Feedback to students should be focused on the task rather than self or attributes of the learner. In particular, the feedback should provide guidance on the process and metacognition (self-regulation) level.

Instead of an end-point in the teaching and learning processes, feedback should be seen as an invitation and a starting point for reciprocal communication that allows students to continue developing skills and ideas through conversations with their teachers.

Feedback should reflect the individual student’s:

• Context and history

• Emotional investment and needs

• Power

• Identity

• Access to discourse

It should encourage positive self-esteem and motivation.

While many teachers would be familiar with giving text-based feedback, an alternative would be to consider creating videos for feedback. Given that teachers could include and customise audio-visual

to students. At the same time, students might also be more receptive to individualised video feedback, as it possesses a greater personal touch from the teacher, compared to textbased feedback alone. For example, Athena Choo, from Xingnan Primary School, found that giving individualised feedback through a video of herself demonstrating how the recorder could be played more accurately, in the context of a recorder module during full home-based learning in 2020, had enhanced students’ learning.

Video feedback does not necessarily have to cover every aspect of a student’s work. A few constructive comments in a short video can also go a long way in developing students’ awareness of their areas for improvement and clarifying how they could proceed to address their learning gaps and build on their strengths. Perhaps, this mode of feedback is one

Structural Elements of Feedback

Recordings

(Henderson and Phillips, 2014)

Choo, A. (2021). ‘Enhancing learning with formative feedback through ICT platforms’ in STAR (Ed). Sounding the Teaching V: Technology and Inclusion in Pedagogy. p.184-189.

A few constructive comments in a short video can also go a long way in developing students’ awareness of their areas for improvement and clarifying how they could proceed to address their learning gaps and build on their strengths.

communication cues (e.g. vocal tone, facial expressions, body language), demonstrations, and supporting artefacts such as students’ work and marking rubrics, videos have the potential to convey more information

that teachers could experiment with, especially if they were interested to explore different ways to maximise the time spent on giving feedback, as well as the impact of their feedback on students’ learning.

“International research has highlighted that feedback can be one of the most powerful factors influencing student learning. My research shows that teachers who create individual videos to provide feedback to students can have substantially greater impact than other forms of feedback. Our data reveals that student perceptions of personalisation, usefulness, and clarity are substantially increased simply by switching from written feedback to video feedbackin one school, students reported feelings of connectedness to their teacher rose from 69% to 91% simply by teachers switching feedback mode. If you are teaching large numbers of students, video feedback can actually save you time - you are able to say a lot more in one or two minutes compared to how much you can write or type!

If you are new to providing digital feedback, you might like to look at this page which gives you some ideas about how to get started. This page provides you with some information about the order in which you might present ideas in your videos. If you are wanting to find out more, you can click here to read a number of articles we have written reporting our findings as well as accessing some quick reference guides which you can use yourself as well as share with colleagues.”

Dr Michael Phillips, Associate Professor of Digital Transformation in the Faculty of Education, Monash University

Blended Learning: Blending the Best of Both Worlds

Blended Learning

Blended learning presents the best of both worlds, where students can benefit from a wider spectrum of learning experiences in both physical and online spaces. Ideally, when planned and implemented well, blended learning allows for competency-based learning and the customisation of learning, enabling students to learn anytime and anywhere. Blended learning in MOE’s context refers to the re-imagination of our students’ educational experience by providing them with a more seamless blending of different modes of learning. The key intended outcomes of blended learning are to nurture self-directed and independent learners and develop passionate and intrinsically motivated learners (MOE, 2020).

In July 2021, all secondary schools and junior colleges/Millennia Institute (JC/ MI) will implement blended learning for some levels before extending this to all levels by Term 4, 2022.

Ministry of Education Singapore. (2020, December 29). Blended Learning to Enhance Schooling Experience and Further Develop Students into Self-Directed Learners. [Press release]. Retrieved from: https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/press-releases/20201229blended-learning-to-enhance-schooling-experience-and-further-develop-students-intoself-directed-learners

The Clayton Christensen Institute. (n.d.). Blended Learning Models. https://www. blendedlearning. org/models/

This blended approach, though largely accelerated by the ongoing pandemic, is a step towards developing our students to be self-directed, passionate, and life-long learners.

This signals a shift in the way classrooms have typically been structured. This blended approach, though largely accelerated by the ongoing pandemic, is a step towards developing our students to be selfdirected, passionate, and life-long learners.

As a guide, there are various blended learning models that teachers can refer to when structuring their lessons. The Clayton Christensen Institute has developed a few blended learning models that teachers can adopt or adapt.

LEARNING

School: Practice and Projects

Home: Online Instruction and Content

The Flipped Classroom Model

One model that most teachers would be familiar with is the flipped classroom model.

Click here to watch the video on ‘The Flipped Class: Rethinking Space & Time’

The Clayton Christensen Institute. (n.d.). Blended Learning Models. https://www. blendedlearning. org/models/

Flipped Learning Network. (2014, March 12). Definition of Flipped Learning. https:// flippedlearning. org/definition-offlipped-learning/

In this model, the learning of the content happens out of class, typically at home. Although the teacher sets the parameters of what to learn, the

processes and planning instruction around students’ interests, ideas, and needs. However, with a class of approximately 30 to 40 students, it is difficult for the teacher to personalise the learning experience for every student. By flipping the classroom, students come to class equipped with the content knowledge for the lesson, learning it online prior to the face-to-face lesson. The teacher then spends his/her time in class to provide additional support to guide students who have difficulty applying the concepts taught. The teacher is also able to transform the lesson into a dynamic, interactive learning environment where the educator guides students as they apply concepts and engage creatively in the subject matter (Flipped Learning Network, 2014).

The teacher is also able to transform the lesson into a dynamic, interactive learning environment where the educator guides students as they apply concepts and engage creatively in the subject matter.

student has a say about how he or she learns the content. Students then work on assignments or projects in class, thus “flipping” the classroom. This way, the physical classroom is redesigned such that the teacher is no longer the focal point. Music teachers are encouraged to design lessons that are student-centric in nature, placing students at the heart of teaching

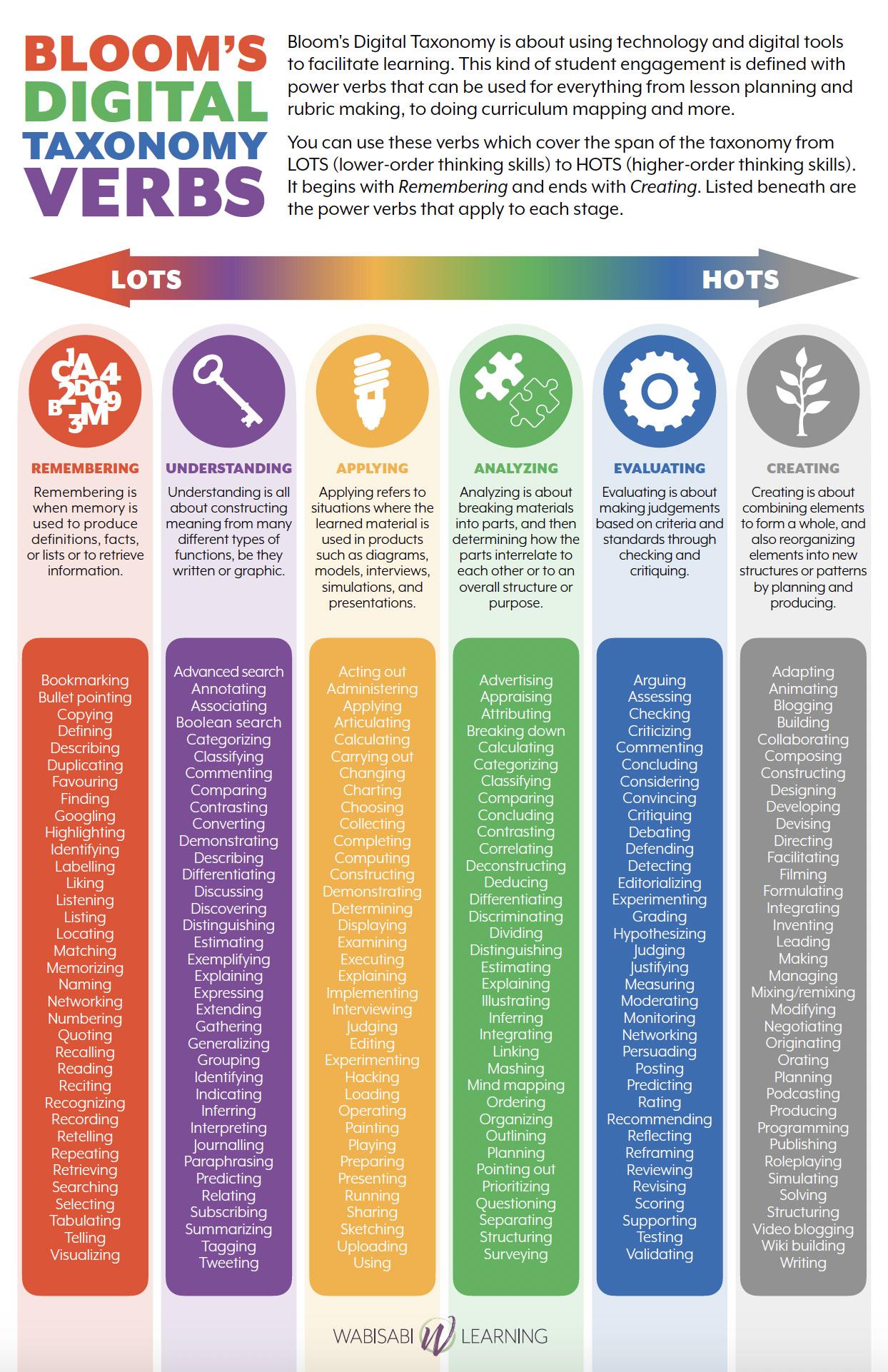

The flipped classroom model encourages teachers to reconsider how their students spend their time when they are physically in school. Teachers need to plan ways to get students engaged in the higher order of thinking of Bloom’s Digital Taxonomy, such as the analysis, application, evaluation, and creation components.

Click here to read more about flipped learning.

WatanabeCrockett, L. (2020, February 3). The Bloom’s Taxonomy Verbs Poster for Teachers. Wabisabi Learning. https:// wabisabilearning. com/blogs/ literacy-numeracy/ download-bloomsdigital-taxonomyverbs-poster

Horn, M. B., Staker, H., & Christensen, C. M. (2014). Blended: Using Disruptive Innovation to Improve Schools (1st ed.). JosseyBass.

The classroom activities should be designed building on or extending from the content that students have already learnt before coming to class. Following which, lessons in class could adopt an inquiry design where the teacher transits into the role of a facilitator, with the main focus on the students and the learning that is happening in the classroom.

Today, with a host of online resources and technologies available, flipping the classroom is easier than ever. Currently, with the safe management measures in place in music classrooms, the flipped classroom model lends itself well to enable students to continue their learning in singing or playing a wind/brass instrument. Most teachers can utilise the Student Learning Space (SLS) or Google classrooms to post resources for pupils to access, practise, and self-evaluate.

How does flipping the classroom then help to nurture self-directed and independent learners and develop passionate and intrinsically motivated learners? Flipped learning alters the act of learning as students engage with the material independently online. When students access resources online, it gives them the freedom to learn at their own pace. For example, they are able to revisit and revise a particular concept, pause for further contemplation, or even progress quickly through parts they are familiar with. With the ability to learn at a pace that is comfortable for them, students have more control over when they learn. They also have the opportunity to explore further or extend their knowledge, which gives them a greater sense of ownership of their learning (Horn et al., 2014). This process promotes self-directed learning and develops independent learners.

Helmi, E. (2021).

‘Flipping the ukulele classroom to ensure student readiness’. In (STAR). Sounding the Teaching V: Technology and Inclusion in Pedagogy. p. 30-38.

Woo, M. (2021).

‘Flipped learning on the recorder’ In (STAR). Sounding the Teaching V: Technology and Inclusion in Pedagogy. p. 23-29.

Students were more well-prepared and more motivated with a flipped learning approach

The above benefits have resonated with music teachers who have conducted critical inquiry studies related to flipped learning. For example, Eymani Helmi from Yu Neng Primary School found that students were more well-prepared and more motivated with a flipped learning approach. Marianne Woo from St Stephen’s School then, found that flipped learning created a more inclusive music learning environment.

Considerations for Blended Learning

Student readiness

When harnessing technological platforms for direct instruction in the individual online learning space, teachers need to consider various factors such as age, prior knowledge, disposition towards learning, competency level and challenge and the extent of home support. When adopting a blended learning approach, teachers need to be mindful of the age group of students that they are planning the lessons for. Younger students will require more guidance and scaffolding when completing tasks online. For example, teachers can post tutorial videos of new applications on SLS to help students understand the functions of the application before they use it.

Teachers could also spend some time in class introducing the interface of a new application that their students will be using.

Disposition towards learning

Teachers need to know their students well. It is important to be aware of the various learning needs in their classes, as well as other external factors that may impede the students’ learning when they are not in a formal learning environment. For example, teachers can consider posting instructions in a multi-modal format to cater to students of various learning styles. Text-based instructions may be better suited for visual learners while an audio recording of the instructions will greatly aid auditory leaners. If the teacher posts a video online, it would be more appealing to kinaesthetic learners if they are given a task to try while watching the video, instead of passively viewing it. Another example could be creating a video with subtitles, as this could greatly aid those who have to learn in a noisy environment at home.

Competency Level and Challenge

In order to nurture self-directed and independent learners, teachers need to ensure that the tasks assigned to students are engaging and instill a sense of ownership and achievement

upon completion. Teachers can consider differentiating the content posted online or differentiating the product/ final submission based on the lesson objectives. For example, for students who are learning how to play the recorder through the flipped learning approach, the teacher can consider posting various repertoire of similar difficulty levels for students to practise. Students can then choose to submit a video performance based on a song of their choice from the selection. The teacher can also post repertoire of varying levels of difficulty and students can challenge themselves or choose easier songs to play.

Extent of home support

Teachers should also design lessons that require minimal home support i.e. from the selection of platforms to ensuring that resources can be easily accessed. For example, resources should also be hosted on platforms that allow for access on multiple devices. Students should be able to view or use the resources on the myriad of portable electronic devices available. This can help to facilitate learning and reduce barriers to the access of these resources.

Assessment for Learning

Apart from gaining knowledge online, teachers should also harness technology to allow their students to evaluate their performances. Performing, creating, listening, and responding are the main learning outcomes of music education. When students record themselves, they should be able to develop a sense of self-awareness to assess their performance, if teachers provide scaffolding in the form of checklists, or rubrics. Teachers are also able to assess their students’ performances prior to the physical lesson and tailor the lesson to target different groups of students’ learning, thus allowing for better differentiation of the music lesson.

Blended Learning in the music classroom

At the start of the year, Dr Brent Gault, Professor of Music (Music Education) and Chair, Department of Music Education at the Jacobs School of Music in Indiana University Bloomington shared various blended learning strategies with the Primary Music STAR Champions.

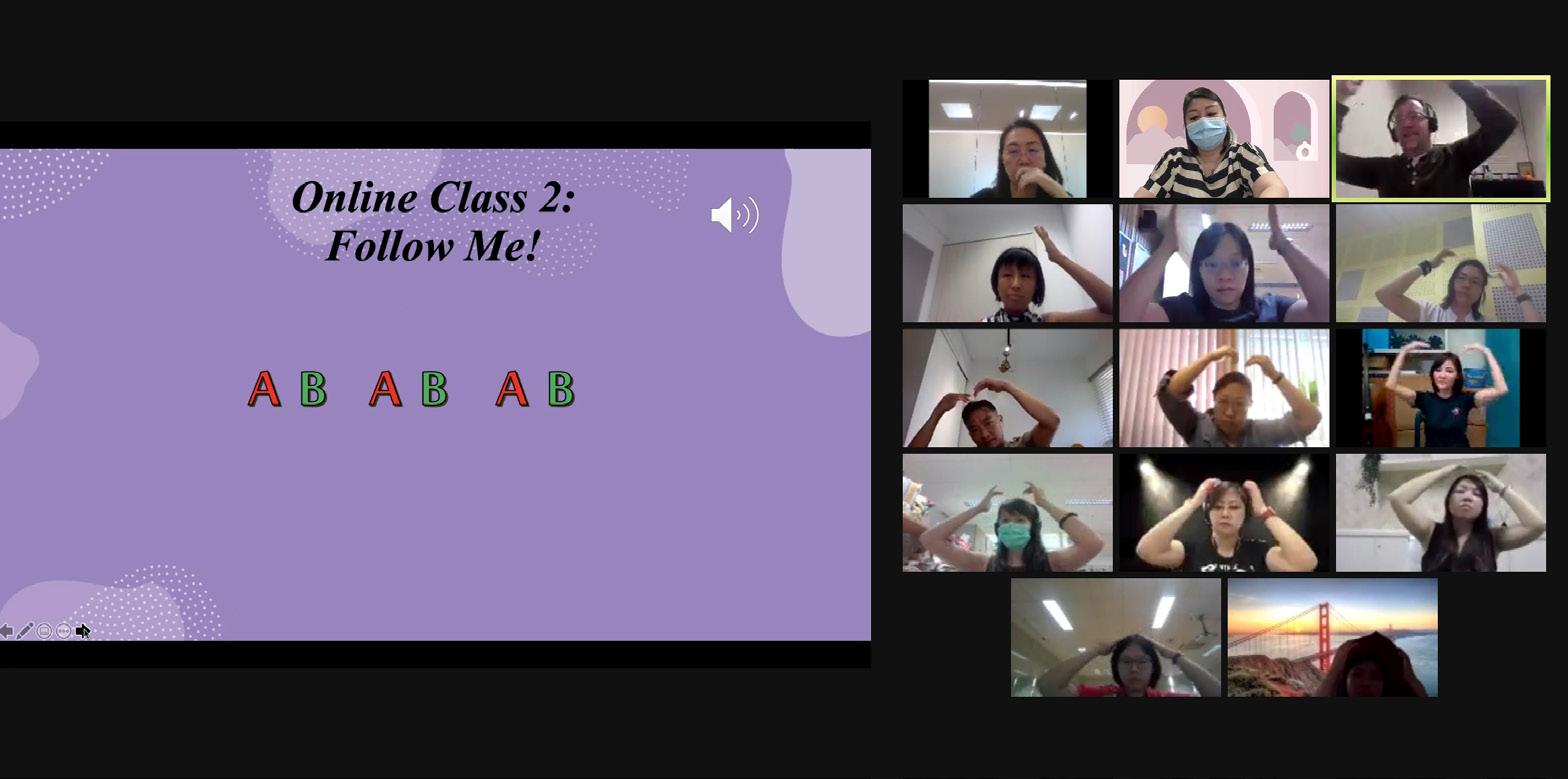

Since the start of the global Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns, he has been conducting online classes with his higher-education music students. His expertise in using the Flipped Classroom approach for teaching singing has enabled him to facilitate a more engaging home-based learning experience for his students.

Here, he shares other considerations when designing blended learning music lessons.

“When engaging in blended learning, music teachers must examine how best to navigate student learning so that online experiences result in meaningful face-to-face experiences,” says Dr Gault. “While there are many different ways to interpret and implement meaningful blended learning activities, here are a few suggestions based on my own recent experiences.”

“Traditional blended learning settings are ones in which students engage in learning about concepts online so that they can experiment with those concepts during face-to face instruction. When this is applied to music, teachers can create online lessons that introduce students to rhythmic, melodic, formal, expressive, and other concepts through structured experiences. This is a wonderful opportunity to utilise musical behaviours that are not possible in face-to face settings due

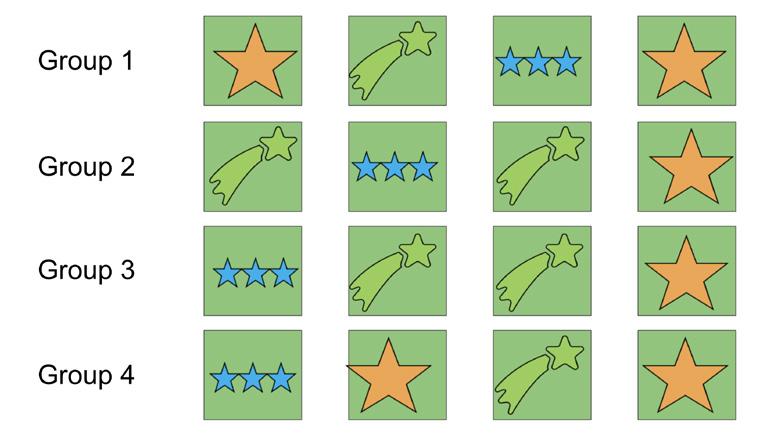

Icon Pattern! Group work

to current restrictions,” he added. “For example, students can learn and sing a song in an online setting, and this can be the basis for teaching them about specific concepts found within the song. Using the voice or piano to scaffold and guide singing or having a recording that students can sing along with provides support for them as they participate.”

With the wide range of technologies today, this can be quickly achieved. For example, a teacher could record and upload a short tutorial video of himself/herself teaching students how to play an instrument. Alternatively, teachers could source for suitable videos from the plethora of videos hosted on various video sharing platforms. However, simply getting students to watch the videos while practising on their own at home is not sufficient. It is critical that the teacher draws connection from the online lesson with subsequent faceto-face sessions.

“When thinking of ways to connect an online lesson to face-to-face instruction, having some type of project students can create and use once they are face-to-face enables them to see how their work online connects to creative musical behaviours they can perform inperson,” Dr Gault explains. “For example, if an online class focused on rhythm, a teacher could ask students

to compose a 16-beat rhythmic composition using what they learned with a platform such as Google Slides. The teacher could save students’ compositions and use these during face-to-face instruction as the basis for movement, performing with instruments, or improvisation. In addition, an open-ended assignment like this allows for students to work at different levels based on their own understanding of the given concept and allows them to present it in numerous different ways based on their own interests.”

Conclusion

There are various models to the blended learning approach. As educators we need to be aware of the considerations for blended learning based on the profile of our students, before designing the module. We should adopt an approach that is most suitable in enabling our learners to understand the concepts taught. We will need to continue to innovate ways to engage our students both in the online and physical space.

Musical Conversations with Loo Teng Kiat

Loo Teng Kiat, Lead Teacher at Zhenghua Primary School and STAR Champion, shares his journey as a teacher-leader and his experiences teaching music during a pandemic.

What does music education mean to you? How do you think music education can positively impact individuals for life and society at large, particularly during this COVID-19 period?

I believe that music education empowers communities to discover and preserve their heritage, as well as share their culture with the world. I think of music teachers as magical beings – they can transform any day, especially a really bad day, into a memorable day filled with singing or instrumental playing. In my opinion, music is a powerful force that can heal individuals, even though I always joke and remind my colleagues and friends that I’m a musician, not a magician.

Unsurprisingly, music was my favourite subject in school. Music lessons were always the highlight of my week, as those enchanted experiences showed me how music was like an elixir that could comfort, heal, and inspire. One could draw

a parallel with the countless viral videos of how people from different countries turned to music making during lockdowns.

Teng Kiat leading P6 students

in a drumming session

“In these times of isolation and separation, music has brought comfort and strengthened social bonds.”

In these times of isolation and separation, music has brought comfort and strengthened social bonds. From the impromptu balcony duets in Italy to the international virtual choirs by Eric Whitacre, I can say with certainty that music and music education have helped many to overcome these trying times.

Share with us a significant or memorable moment during this COVID-19 period.

In 2020, I was co-teaching a Primary 6 music class when I noticed a group of ten at-risk boys.

learning. In doing so, I could get to know these students better, give them more attention, and differentiate the music lessons for them based on their interests. Although each child had his own struggles, they soon bonded over their interest in drumming, especially after I shared with them my own experiences as a percussionist in a marching band. The boys thought it was “cool” to be able to drum. We started with body percussion, boom whackers, and subsequently progressed to proper drumsticks. Despite the disruptions from the pandemic and school closure, it was encouraging to witness how these boys eventually developed into a disciplined drumline. There was a noticeable improvement in many of their attitudes and they also found a renewed purpose in coming to school.

In terms of teaching and learning, what are some challenges you have faced during the COVID-19 period?

My co-teacher and I decided to split the class to facilitate their

I regard the uncertainties and fears arising from COVID-19 as a great opportunity for growth and advancement within the fraternity. It was uncomfortable to rethink and reframe what teaching and learning would look like in a pandemic, and it was certainly frustrating to manage changes that emerged from multiple directions. Nevertheless, I was heartened that many teachers were able to overcome various challenges through perseverance and collaboration.

Since the Circuit Breaker in 2020, there has been a significant increase in the number of online lessons and resources shared on platforms such as the Student Learning Space (SLS). Teachers have rallied together, sparking an amazing synergy within the fraternity. In particular, it has been inspiring to witness how a disruptive pandemic has amplified the union between the technical savviness of the younger teachers and the strong pedagogical knowledge of the experienced teachers. Together, teachers created websites, explored new applications, produced and shared instructional videos and online lesson packages. I truly hope that we will continue to build on this collective momentum of progress and development.

“In particular, it has been inspiring to witness how a disruptive pandemic has amplified the union between the technical savviness of the younger teachers and the strong pedagogical knowledge of the experienced teachers.”

Could you share some examples of strong mutual support/sharing of ideas from the community of music teachers that have helped you or your colleagues tide through this challenging time?

I believe that these challenging times have brought out the best in us as a fraternity. When the Circuit Breaker occurred, music teachers exchanged technical expertise to help each other

with online teaching and learning. Many of us were also grateful to receive frequent updates and guidance on Safe Management Measures (SMM). Apart from sharing our ideas, materials, and lessons, we provided and received encouragement and emotional support. The pandemic has definitely brought our community of music teachers closer together, and it is reassuring to know that we can count on each other.

Could you share with us some of your experiences and takeaways from facilitating blended lessons? What competencies should music teachers develop in order to implement effective blended learning?

Blended learning is not a new concept. Since its inception, educators have been developing and refining such learning experiences to cater to their students. I first pondered over the notion of blended learning during a conversation I had with a few colleagues about the flipped classroom approach some years ago. I decided to explore the flipped classroom approach then with the upper primary students to enhance the short and infrequent music lessons. When SLS was rolled out, I utilised it as a platform to upload sound bites with visual cues for the students to review the concepts learned in class.

“I believe that learning activities require immediate and customised feedback from the teacher, which ideally leads to follow-up actions by the learner.”

I believe that learning activities require immediate and customised feedback from the teacher, which ideally leads to follow-up actions by the learner. Therefore, the curation and design of blended learning for music would require deeper understanding of the content and mode of the lesson, while taking into consideration how the learner interacts with the information and feedback provided by the teacher.

Teachers must also be able to understand and motivate their students to take ownership of their learning beyond the face-toface interactions in the classroom. Students learn through different modes and are motivated by diverse reasons – be it the learner’s technical competence, or interest in selection of songs.

In addition, teachers need to ensure that the follow-up teacherled lessons are meaningful for the learners. Teachers should track their students’ progress after each lesson to inform future instruction and allow them to differentiate and pitch learning activities appropriately for their students.

How has the role of a STAR Champion developed over the years, and what has been the impact of STAR Champions in strengthening and expanding the pedagogical capability of music teachers?

Initially, STAR Champions primarily served as anchors and knowledge bases for teachers within the clusters. I have had the privilege to be appointed yearly as a STAR Champion over the last decade. Through the years, I noticed that our responsibilities strategically shifted. While we previously emphasised the development of musicianship, we have increasingly focused on deepening our pedagogical content knowledge. As STAR Champions, we have been engaging our fellow music teachers during annual zonal or cluster workshops. STAR Champions have also connected with more music teachers by being involved in cross-cluster Network Learning Clusters (NLCs) and Communities of Practice (CoP) as a way to learn alongside more teachers and grow as a fraternity. These have been possible through the professional development programmes organised and led by the Master Teachers at STAR.

What are some of the platforms you have been involved in as a teacher-leader to contribute to the fraternity?

As a Lead Teacher, I serve as a mentor to my school and cluster. It is a privilege to be able to engage with a wide spectrum of teachers via different platforms. In terms of mentorship, I lead the teacher-leader Professional Learning Team (PLT) in school for weekly cross-discipline discussions with teacher-leaders in-charge of various subjects. I also mentor aspiring teacher-leaders in their respective PLTs, which cut across different subjects and levels. Besides the music teachers in my school, I also have the opportunity to mentor music teachers from schools within my cluster.

Over the years, I have hosted music teachers from the Cross-Level Deployment Course (CLDC) in my classroom. Although the pandemic

restricted school visits in 2020, I was able to share my insights and experiences in the designing of online lessons with the CLDC participants via Zoom. I also lead in NLCs and CoP, and have presented my department’s work at the recent e-Arts Education Conference in 2020.

What are some key takeaways from the workshops you have attended this year? How have they transformed the way you look at music teaching?

STAR offers a wide range of PD for music teachers, and the STAR Champions have certainly benefitted from numerous workshops to help them grow in their capacities to lead and impact the fraternity. For example, the joint workshop by STAR and Associate Professor Michael Phillips from Monash University on integrating Technological, Pedagogical, and Content Knowledge (TPACK) into teaching and learning helped me to frame my thinking about effective assessment and feedback. The PD session on blended learning by Professor Brent Gault from Indiana University Jacobs School of Music challenged my own assumptions about blended learning, and the implementation and practices within my own school.

I also had the privilege to be part of AST’s Teacher Leader Programme

“It is important to explore our local music traditions and pass on knowledge of these practices to our students.”

(TLP) last year. In January 2021, we attended a drumming session by NADI Singapura at the Awali Arts Centre. It was conducted by rebana artist, Mr Yaziz Hassan, together with a prominent percussionist, Mr Riduan Zalani. Apart from experiencing the inspiring drumming from such passionate musicians, it reaffirmed my belief in taking time to understand our local cultures and their roles within the Singaporean musical context in contributing to our unique identity as a nation. It is important to explore our local music traditions and pass on knowledge of these practices to our students. Unlike the unrest that is currently occurring around the world, we have worked hard to build and sustain strong intercultural relationships within our island, because we appreciate the importance of going beyond tolerance to embrace our multi-faceted society.

How have you applied your learning from the workshops in your teaching practice?

At Zhenghua Primary we use cultural themes to align our Arts curriculum. For example, the students at Primary Three are exposed to Malay culture, so they learn to do Batik painting with tjanting, perform Malay dances, and sing and perform Malay songs from the indicative repertoire. In terms of future plans, the experience at NADI Singapura sparked the idea of inviting performers to the school for a live demonstration and to give a talk on Malay drumming techniques. I hope the wonderful experiences during future hands-on sessions will be an opportune moment to spark in-depth conversations between my students and these local artists.

Tips & Tools for Music Educators

As music educators, we continually seek to enhance the learning experiences of our students. Here are a few tips on various applications to facilitate the learning process in your digital classroom.

Click here to watch the video on Optimising Zoom settings for music lessons.

Creating a positive learning environment through Zoom

Enhancing your musical feedback when the sounds are being optimised

Optimising Zoom settings for music lessons

Conducting a synchronous music lesson over Zoom may not be ideal. However, you can adjust certain audio settings to create a smoother Zoom experience for your students.

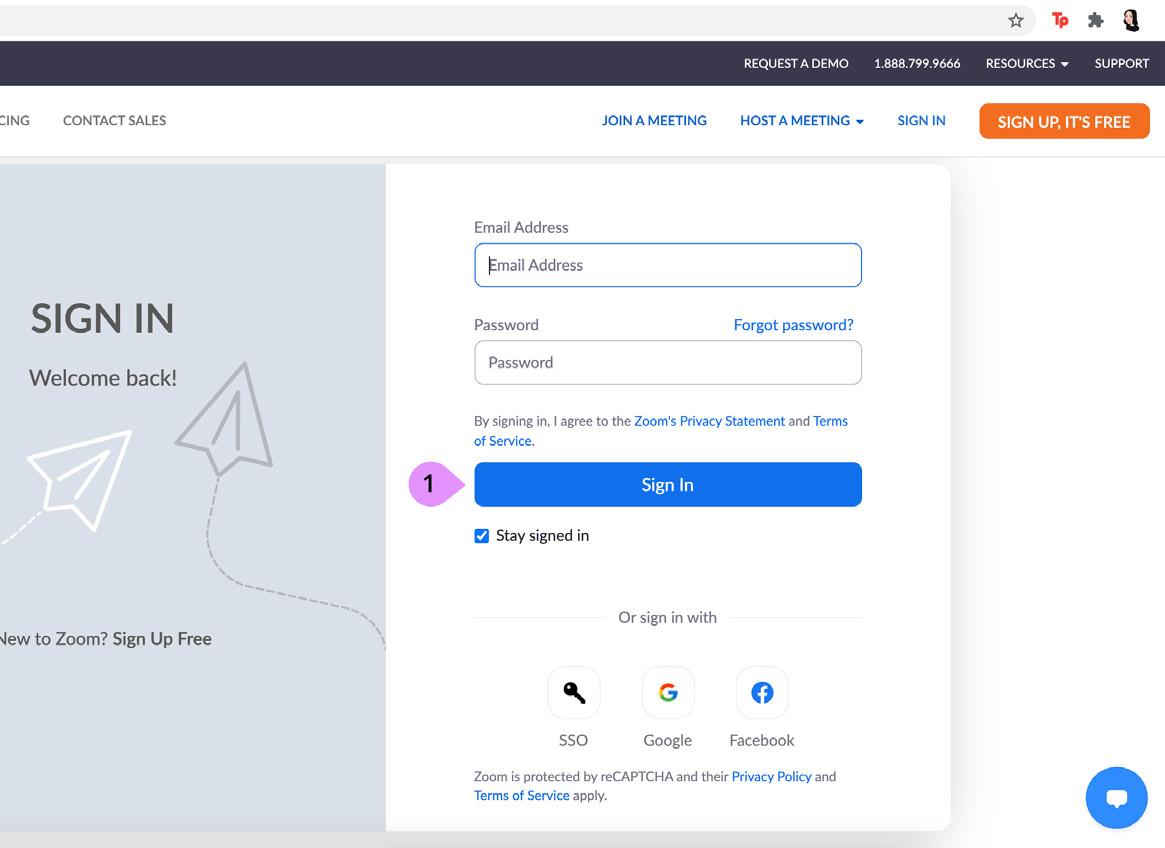

Before starting the Zoom session

Ensure that you have a strong internet connection. It will be best if you are able to connect the ethernet cable to your laptop.

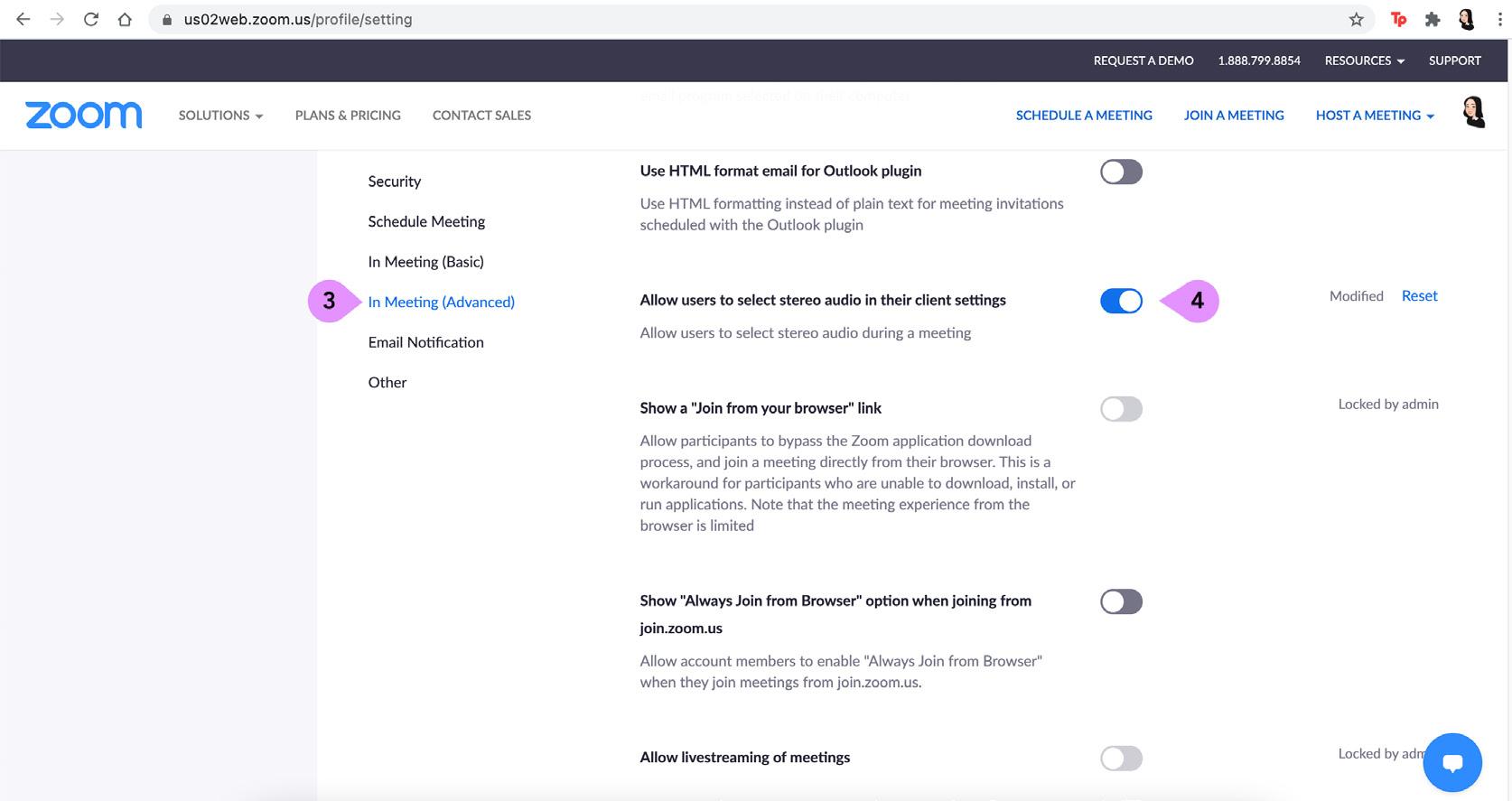

Enable Allow users to select stereo audio in their client settings – this will allow your students to view and turn on the Enable original sound setting during the Zoom lesson as well.

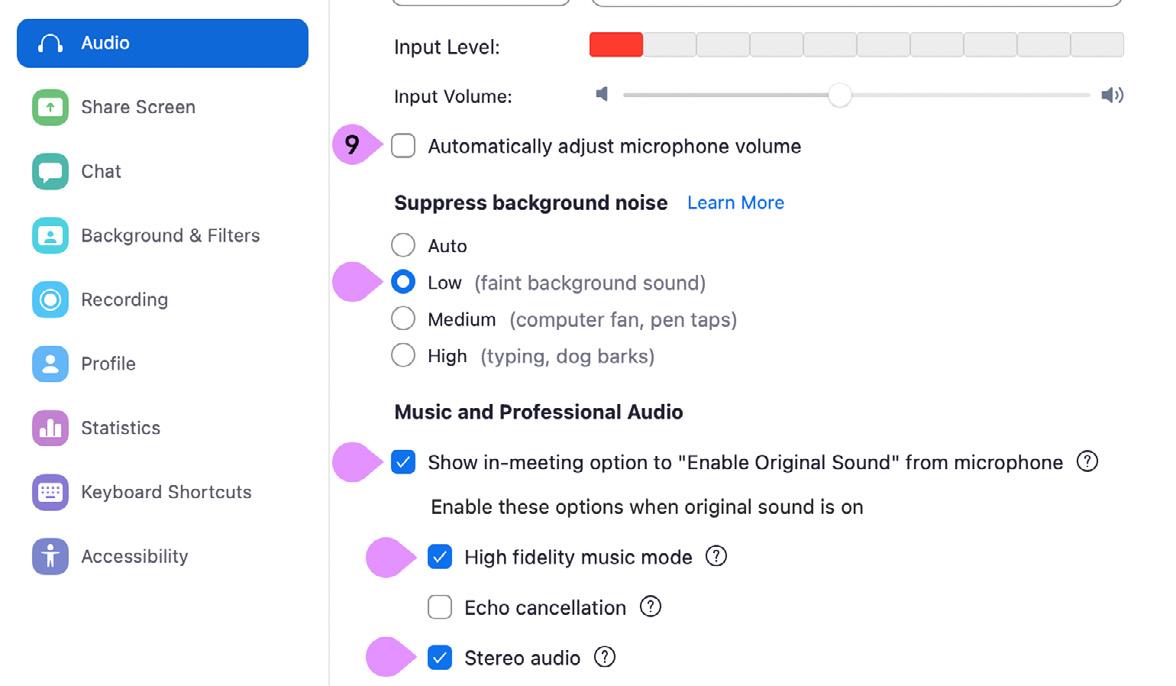

Adjusting the settings in Zoom desktop client

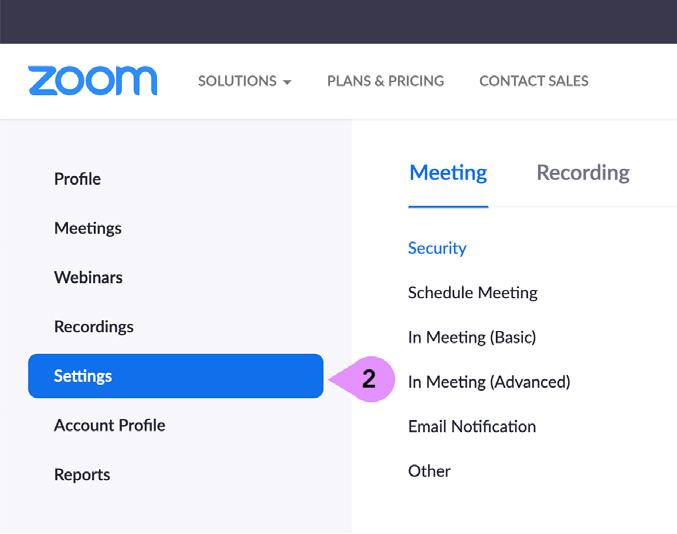

After managing the settings in the Zoom portal, adjust the settings in the Zoom desktop client

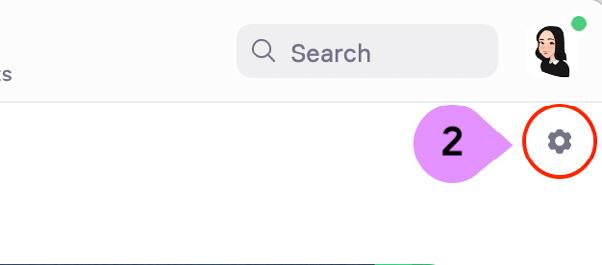

Sign in to the Zoom desktop client on your device.

3

Click on Audio in the Settings menu.

Click on the image of the cog on the top right corner to enter the Settings menu.

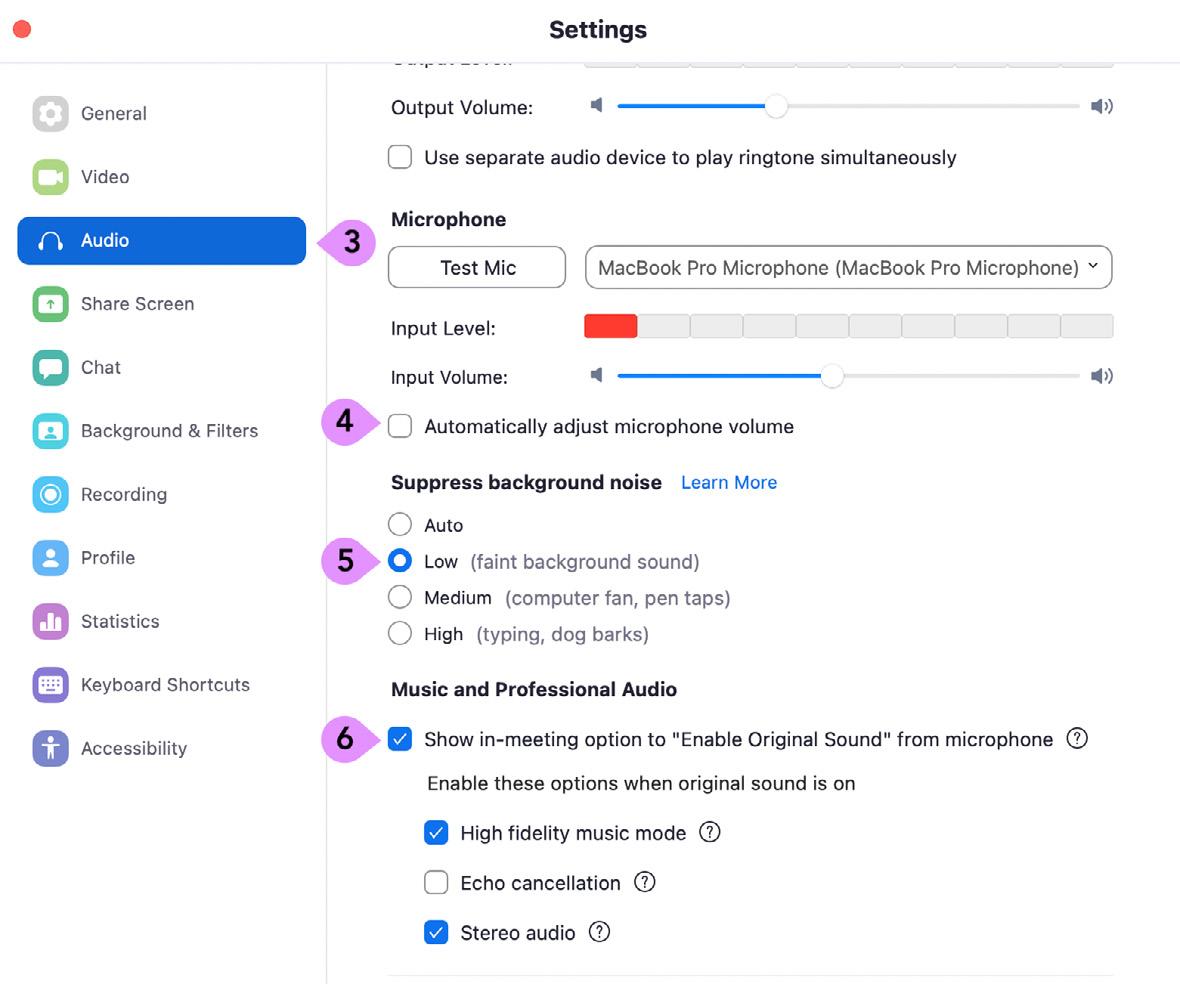

Uncheck the Automatically adjust microphone volume option. 4

5

6

Select the Low (faint background sound) option under the Suppress background noise menu.

Check the Enable Original Sound option. Once you have enabled it, three other options will appear. Check High fidelity music mode, uncheck Echo cancellation, and check Stereo audio After you have updated the settings, exit the Settings menu.

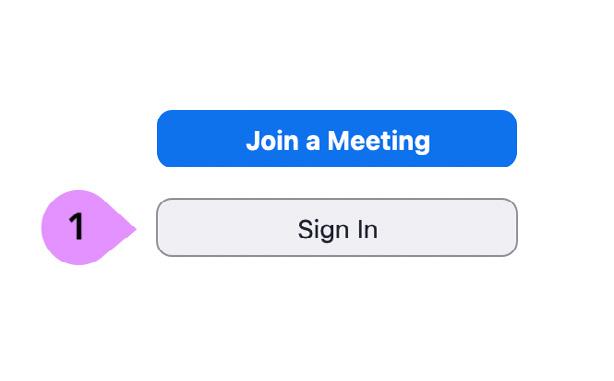

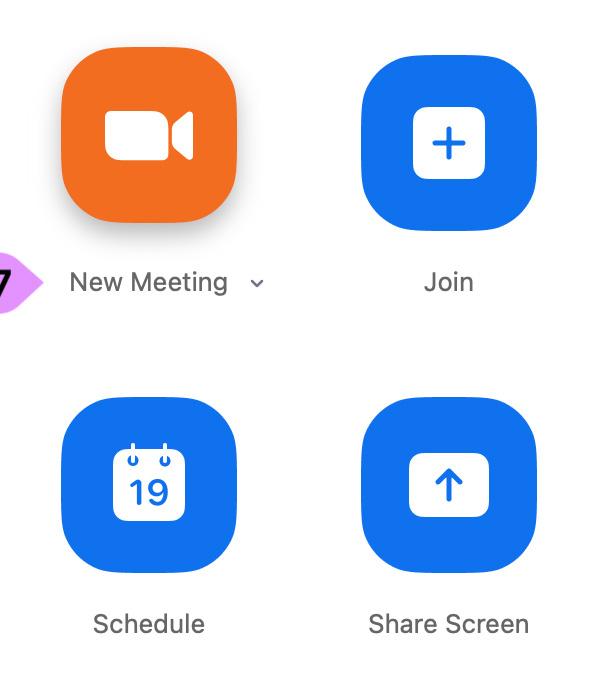

To check that the audio settings have been updated, click on New Meeting.

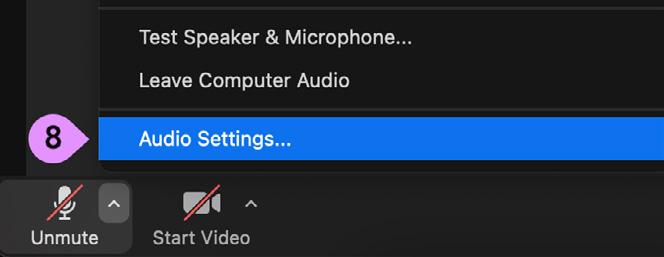

Click on the upward arrow next to the audio icon to access the Audio Settings.

Check that the audio settings are updated.

a. Automatically adjust microphone volume option is unchecked

b. Low (faint background sound) option under the Suppress background noise menu is selected

c. Enable Original Sound option is checked

d. High fidelity music mode is checked

e. Echo cancellation is unchecked

f. Stereo audio is checked

Finally, select Turn On Original Sound to enable updated audio settings.

• 5.6.7 or earlier (Original sound is successfully turned on when Zoom shows ‘Turn Off Original Sound’).

• 5.7.0 (Original sound is successfully turned on when Zoom shows ‘Original Sound: On’)

Enhancing assessment for learning

Google Classroom

Apart from SLS, Google Classroom is another versatile platform music teachers can use to host asynchronous lessons, to share resources, and to assess students’ submissions. Students are able to collaborate and submit assignments through various Google applications in Google Classroom. Teachers are also able to provide feedback to their students through various means e.g. rubrics, video conferencing, comments, etc.

Click here to watch the video on a short video on Google Classroom.

Creating opportunities for self-directed learning Setting Up Your Google Classroom Log

We will be introducing various functions of Google Classroom below.

1

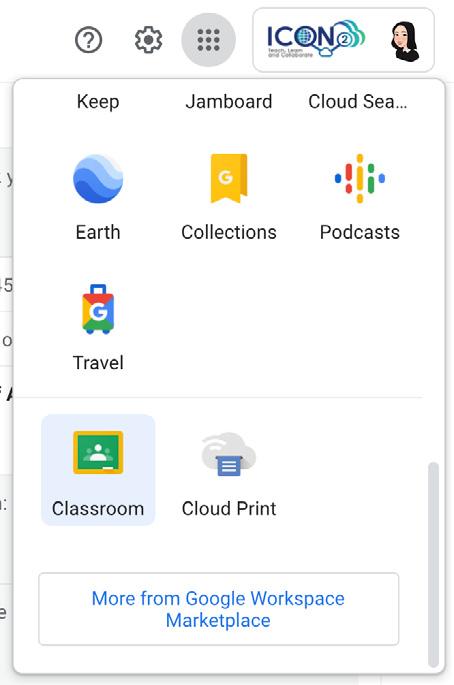

2

Under Google Apps, scroll down and select Classroom.

3

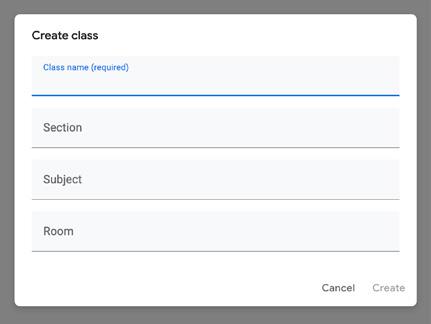

Click on the + symbol at the top right corner to create and name your class.

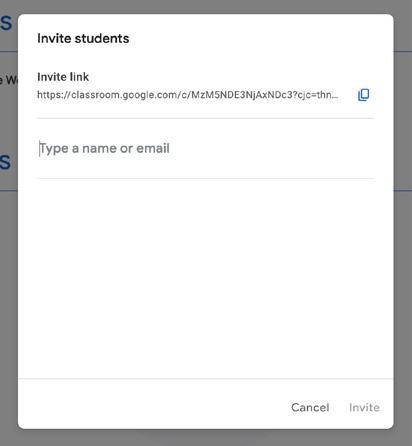

4

To add students, click on People, then click on the + symbol. You can also add co-teachers and parent/ guardians through the same process. However, please take note of PDPA guidelines when adding participants.

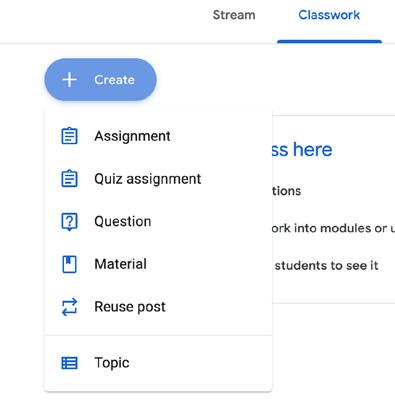

Creating Assignments

1

2

3.1

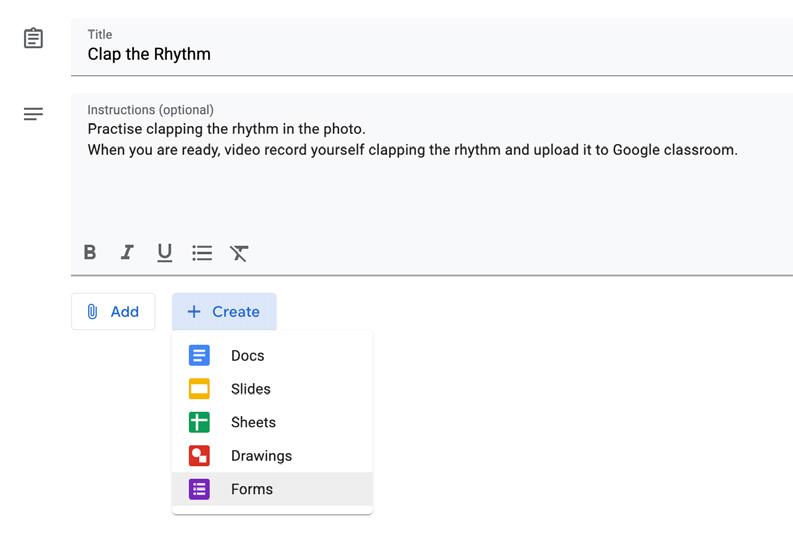

Click on Create and select Assignment. Alternatively, you can choose to create your own resources by clicking on Create and choosing from the following options:

• Docs

• Slides

• Sheets

• Drawings

• Forms

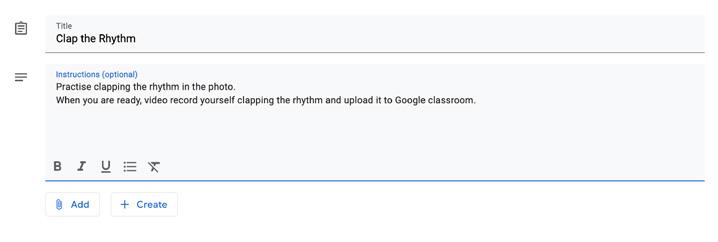

Add a title and instructions to the assignment.

3

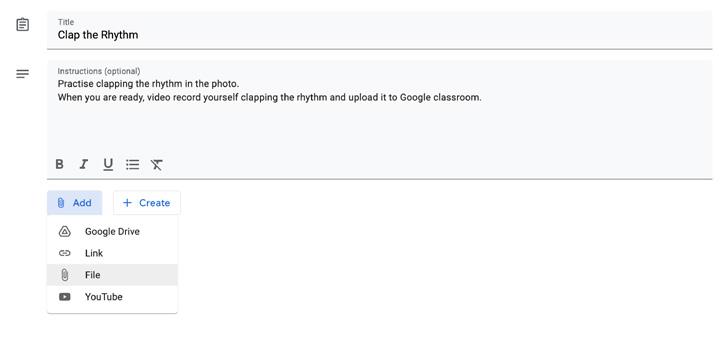

Click on Add to add resources by choosing from the following options:

• Google Drive

• Link (to another website)

• File (upload from computer)

• YouTube

All of these resources have various functions. You can explore the applications to select those that are suitable for the assigned task. (e.g. Students can collaborate to write a song using a Google Sheet template shared by the teacher)

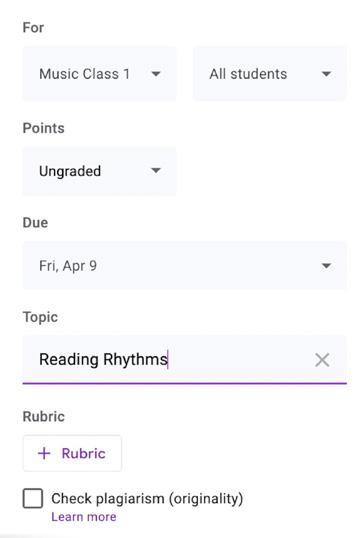

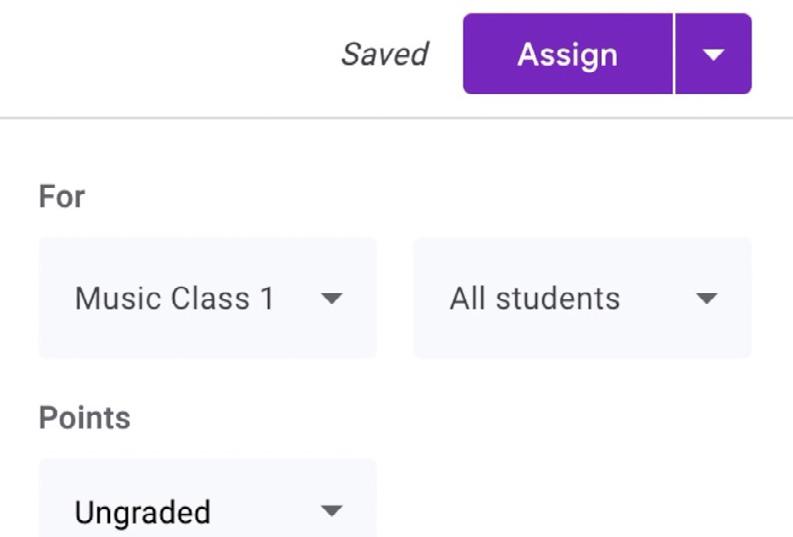

4

On the right-hand column, you can include a due date, topic, and even points (if necessary) for the assignment. Including a topic will help to catalogue your assignments.

5

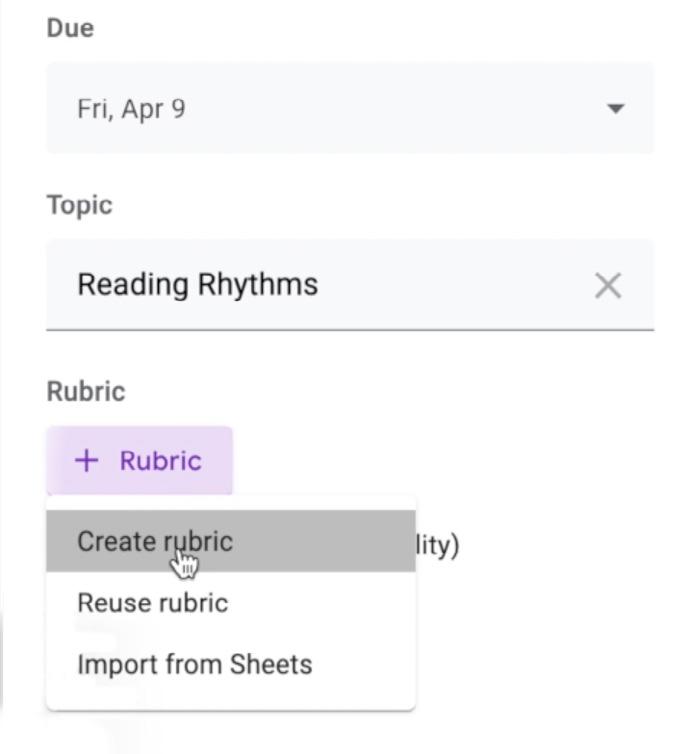

In the same column, you can choose to add a rubric for the task. Your students will be able to see the rubric and familiarise themselves with the expected criteria and skill(s) to be demonstrated. While creating the rubric, you can add more levels and criterion by clicking on the + symbol.

6

Click on Assign to assign the task to students. There is also the option of specifying which students you would like to assign the work to.

Students’ Work

1

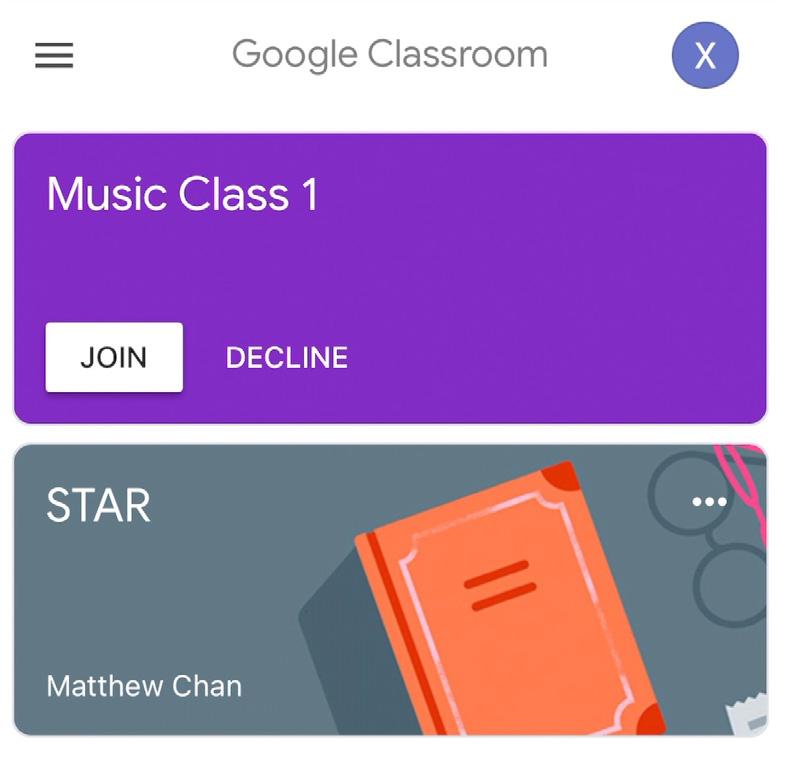

Your students can access Google Classroom via the app on their mobile device, or through the Google Suite on their web browser. They should click on Join to join the Google Classroom. Alternatively, you can send students the Classroom Code, which can be found on the main page of the class.

2

Students are to read the instructions for the assignment.

3 4

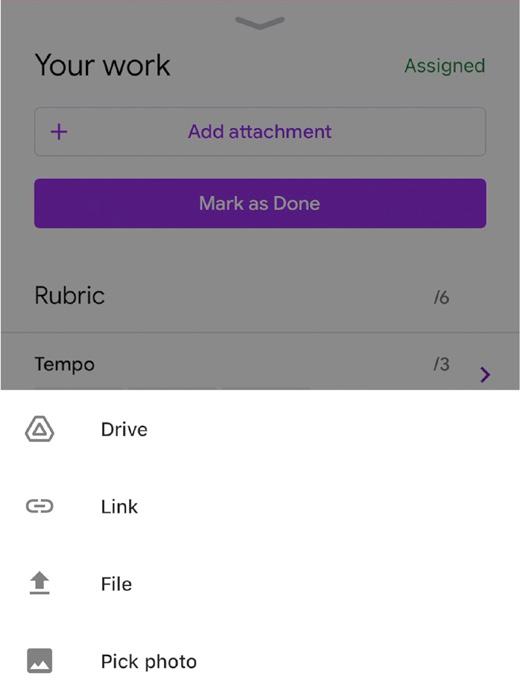

Students are to click Add attachment and select from the following options to upload their work:

• Drive

• Link

• File

• Pick photo

There are other options for submitting work but do consider your students’ familiarity with these tools. Alternatively, students can also upload media via other Apps (e.g. Photos on iOS).

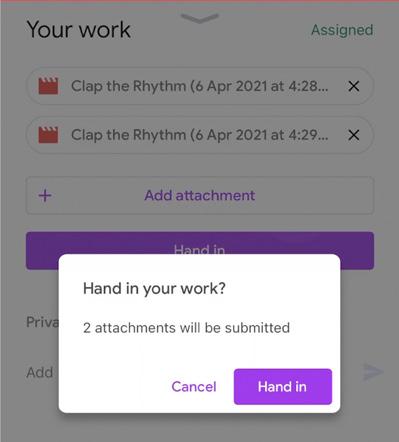

Students to click on Hand in to submit their assignment.

5 For Teachers

To mark a student’s work, select the student via the Turned in tab.

Assign marks on the rubric, give comments, before clicking Return.

Students are able to post replies to your comments and also re-submit their work after you have returned their assignment.

Other Functions

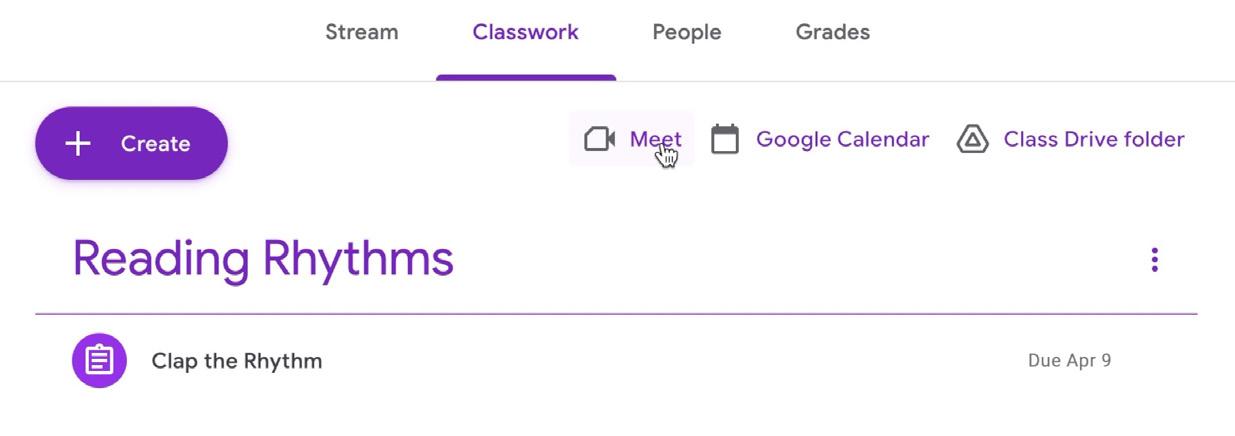

1

Google Meet: You can plan video conferencing sessions with your students from within the platform.

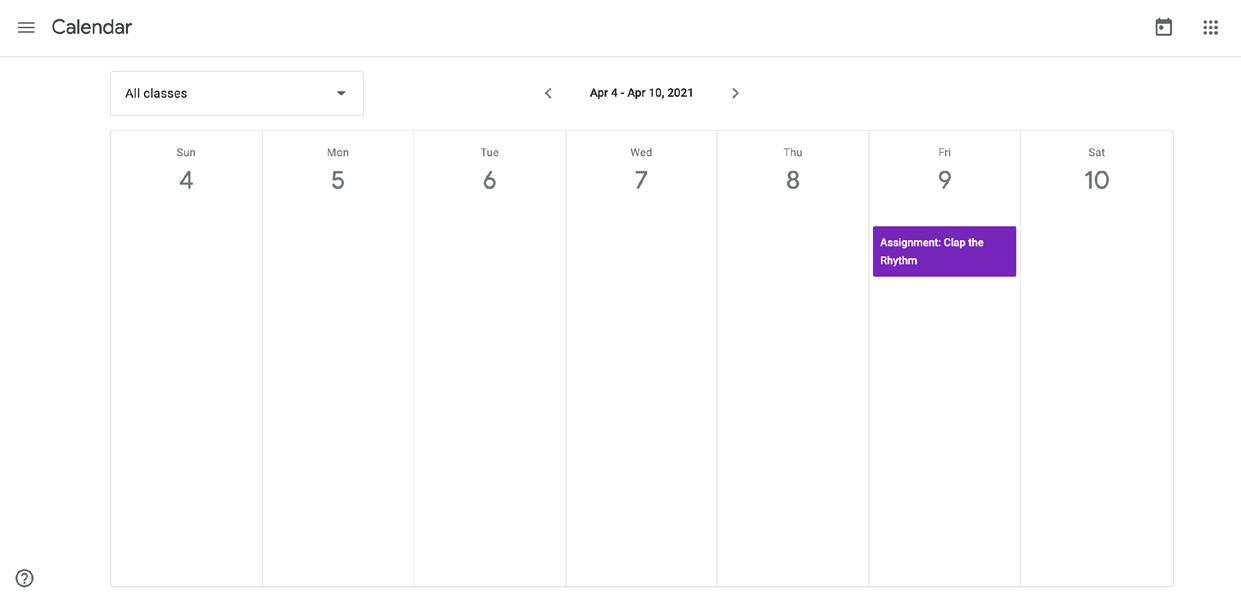

2

Google Calendar: The class will have its own calendar and assignment deadlines are automatically added in.

Google Drive: The class can access/download various resources from Google Drive, based on how you manage the sharing settings. 3

Click here to watch the video on a short video on BandLab MIDI editor keyboard shortcuts.

BandLab Keyboard Shortcuts

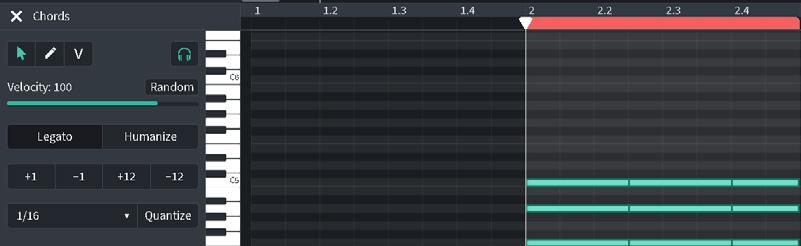

BandLab is a web-based digital audio workstations (DAW) that students can easily access to compose/arrange music. Here, we share some shortcuts that you or your students can use on the MIDI Editor in BandLab.

Developing students’ awareness and mastery of music editing practices, while building their understanding of different musical elements (e.g. rhythm, pitch, chord voicing etc.).

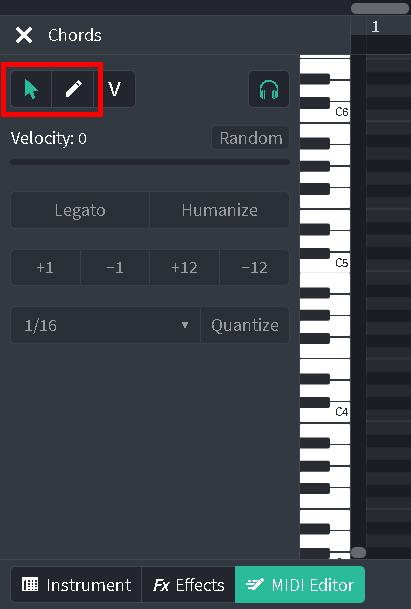

1

Temporarily toggle between ‘Select Note’ and ‘Add Note’ tool

Hold the ‘Ctrl’ key to switch temporarily from the Select Note to the Add Note tool.

2

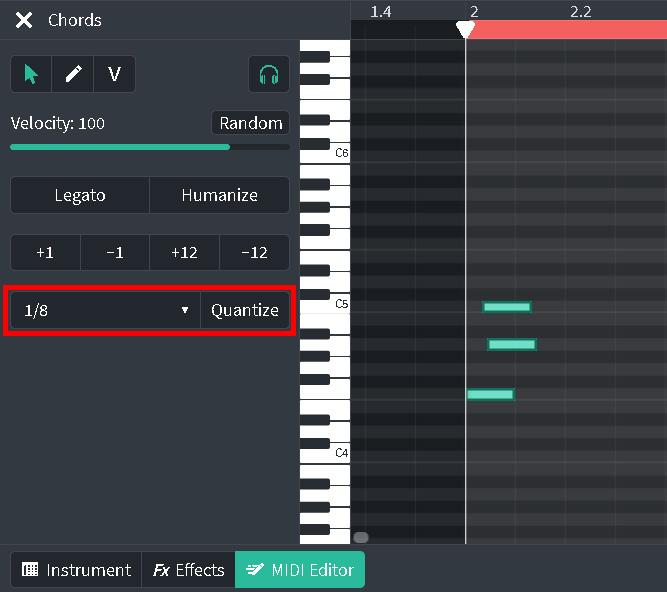

Quantise notes

Press the ‘Q’ key to Quantise the selected notes, snapping the notes back on the beat.

• Before quantise • After quantise

3

Duplicating notes

Hold the ‘Alt’ key and drag selected notes to duplicate notes.

4

Adjust pitch of notes by +/-1 semitone

Use the ‘Up’ and ‘Down’ arrow keys to move selected notes up or down by a semitone.

• Before Arrow Key

• After Arrow Key

Note: You can also click on the +12 or -12 buttons to move selected notes up or down an octave.

5

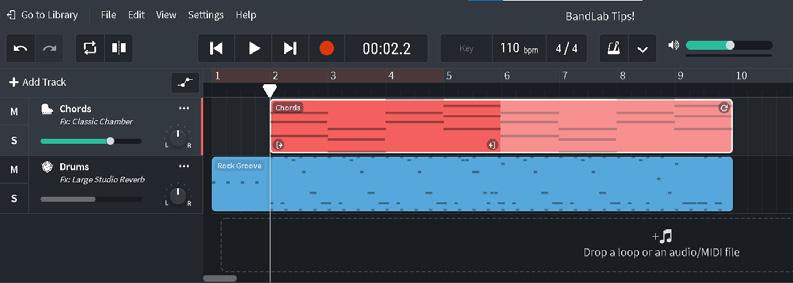

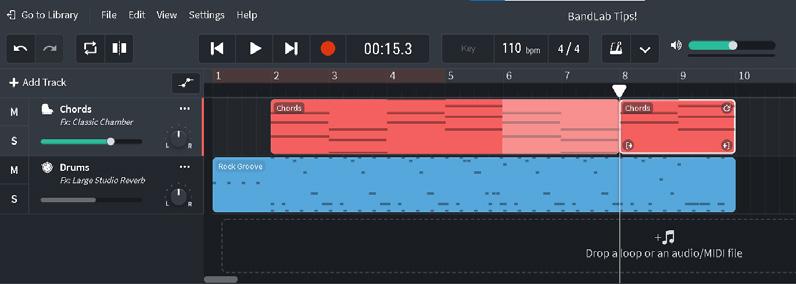

Slice track

Drag the marker to the audio region you wish to slice and press the ‘S’ key to slice regions into 2. This allows for further manipulation of the region e.g. editing, copying, duplicating etc.

• Before Slice

• After Slice

Other Tips

Legato – to tie notes together

To make the notes smoothly connected, click Legato to extend selected notes to tie the notes together.

• Before Legato

• After Legato

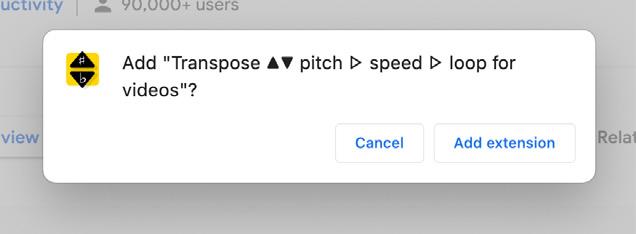

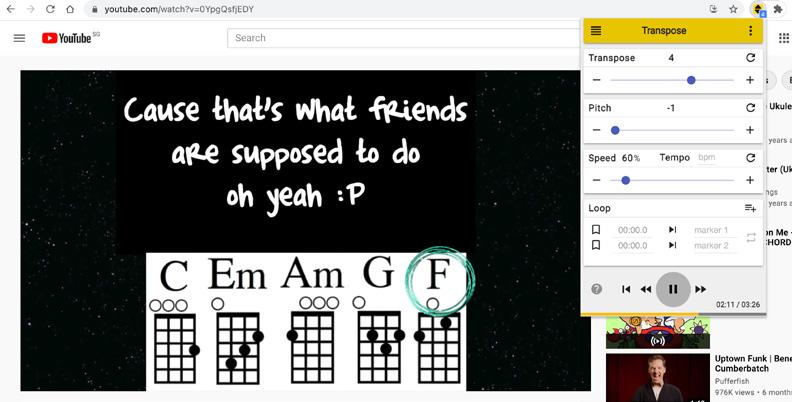

Click here to watch the video on a short video on Transpose - Google Chrome extension

Transpose – A Chrome Extension

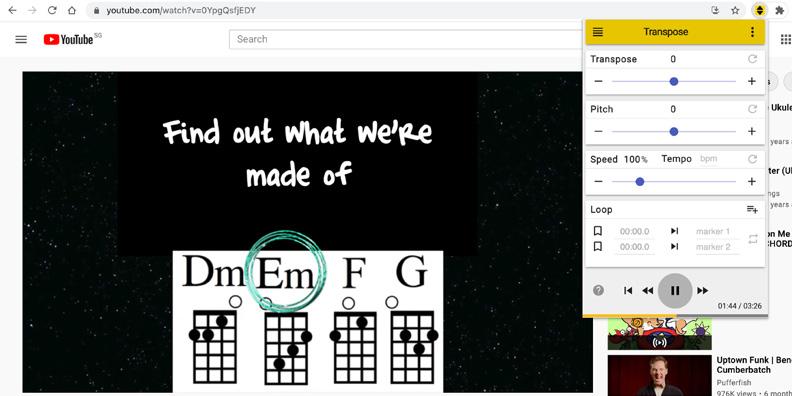

‘Transpose’ is a pitch shifter, speed changer and looper for online videos such as YouTube. It allows teachers to change the pitch of a music video, slow down or speed up the music in the video which they are playing in the browser to suit the learning context in their music class.

2

Customise learning for your students through transposing or changing the speed of the music in the video that is being played on your browser

1

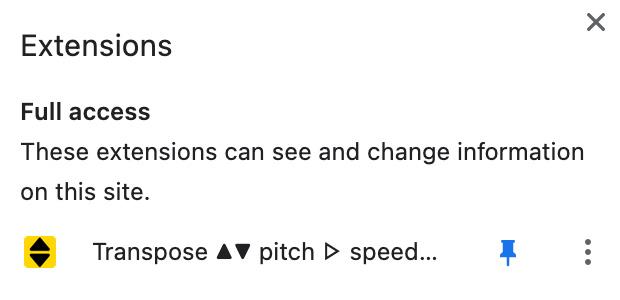

Download Transpose from the Chrome Web Store and add extension. This extension only works with Chrome browsers.

Ensure that you activate the app by clicking on the extensions app in your Chrome browser. Select ‘pin’ for the icon of the app to appear in your navigation bar.

3

To try the various functions in Transpose, you can go to www.youtube.com and click on the Transpose icon on your navigation bar and adjust the settings accordingly.

STAR Highlights

Another semester of new musical experiences with STAR. We’ve put together a roundup of highlights that have been taken place.

01 Sharing session at our Teaching ICT-based Music-Making (Sec and JC) workshop

02 Workshop on TPACK and Video Assessment for STAR Champions (Pri)

03 Experiencing a song through movement at our Kodaly (Milestone) workshop

04 Workshop on CCE, Inclusive Education, and e-Pedagogy for STAR Champions (Sec)

05 Workshop on Blended Learning for STAR Champions (Pri)

06 Creating instrumental arrangements at our Orff Plus workshop

We’d Love To Hear From You

Chau Poh Lin Susanna

Deputy Director (Music)

Susanna_Chau@moe.gov.sg +65 6664 1558

Kelly Tang

Master Teacher (Music)

Kelly_Tang@moe.gov.sg +65 6664 1561

Chua Siew Ling

Principal Master Teacher (Music)

Chua_Siew_Ling@moe.gov.sg +65 6664 1554

Li Yen See

Master Teacher (Music)

Chan_Yen_See@moe.gov.sg +65 6664 1499

Wong Yong Ping, Tommy

Academy Officer (Music)

Tommy_Wong@moe.gov.sg +65 6664 1495

Woo Wai Mun Marianne

Academy Officer (Music)

Marianne_Woo@moe.gov.sg +65 6664 1555

Liow Xiao Chun

Academy Officer (Music)

Liow_Xiao_Chun@moe.gov.sg +65 6664 1494

Suriati Bte Suradi

Master Teacher (Music)

Suriati_Suradi@moe.gov.sg +65 6664 1498

Ng Yong En, Joel

Academy Officer (Music)

Joel_Ng@moe.gov.sg +65 6664 1544

Matthew Kam-Lung Chan

Academy Officer (Music)

Matthew_Chan@moe.gov.sg +65 6664 1497