What Does Differentiated Instruction Ask of Us?

16

Catering to Diverse Learners in a Full-Subject Based Banding Music Class

What Does Differentiated Instruction Ask of Us?

16

Catering to Diverse Learners in a Full-Subject Based Banding Music Class

32 Musical Conversations with Rachel Tan Fong Kin

03

16

04

Editorial Musical Conversations with Rachel Tan Fong Kin What Does Differentiated Instruction Ask of Us?

Catering to Diverse Learners in a FullSubject Based Banding Music Class

32

37

Tips & Tools for Music Educators

42

43

Highlights We’d Love To Hear From You…

Liow Xiao Chun Academy Officer, Music

Matthew Kam-Lung Chan Academy Officer, Music

Ong Shi Ching Melissa Academy Officer, Music

This is a milestone year in my journey as an educator. As I reflect on the classes I had taught, I am blessed to have the opportunity to meet and teach students from a myriad of ability, talents, challenges and learning needs. In turn, much like in the musical The King and I when the character Anna quipped, “That if you become a teacher, by your pupils you’ll be taught” before she sang Getting to Know You, I have learned much from my students, adapting my teaching to their learning needs.

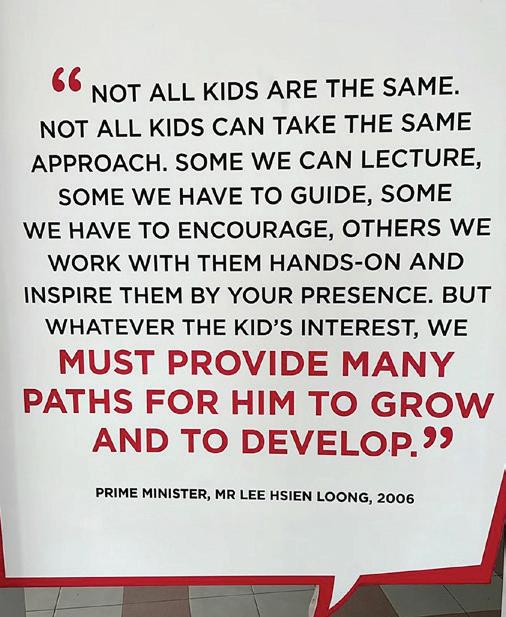

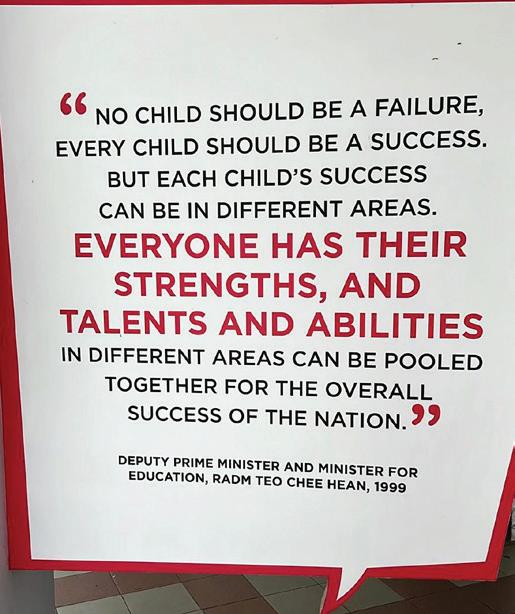

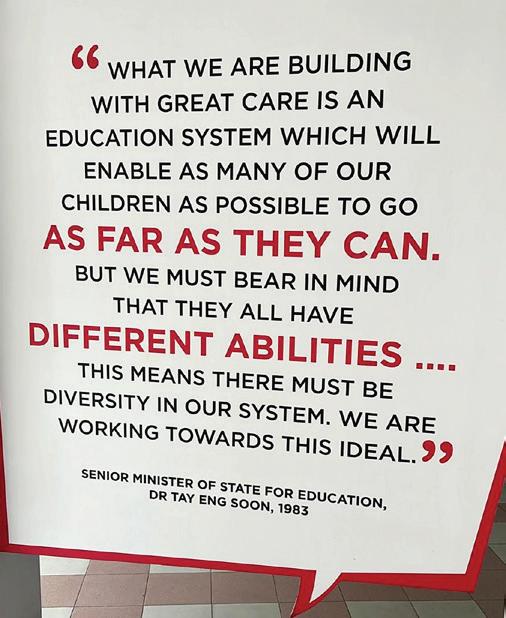

Over the decades, our education has always placed the students in the centre of all we do. If you have had the chance to read the quotes at the main foyer of the Academy of Singapore Teachers by Mr Lee Hsien Loong, Mr Teo Chee Hean and the late Mr Tay Eng Soon, each of them focussed on the same point – to develop students to reach their full potential and enable them to seize opportunities in the future. This focus has not changed as seen on the MOE website:

Diverse Learners in a Full-Subject Based Banding Music Class, we look at the implications of Full SBB in our music classroom, what considerations we should bear in mind in facilitating learning in a heterogeneous class and hear from our teachers who are onboard the Full SBB journey.

“We aim to help our students discover and make the best of their own talents, to help them realise their full potential, and develop a passion for lifelong learning.”

Over the years, we have worked towards Harmonising Differences in our students. We learn to appreciate the diverse strengths and abilities of our students, harness their strengths, meet their learning needs, and stretch and uplift them.

We have made much headway in this with moves such as Full-Subject Based Banding (Full SBB) to meet the strengths and needs of our students. In Catering to

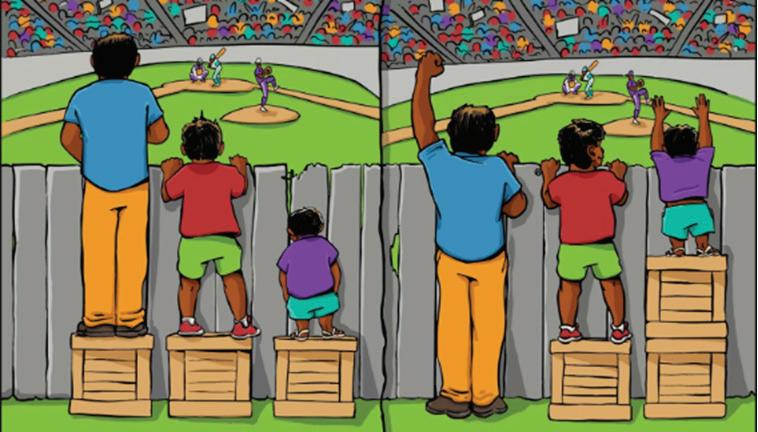

In addressing the varying needs of our students, we embarked on the journey of Differentiated Instruction (DI), learning how we can meet the students where they are in a heterogenous classroom. What Does Differentiated Instruction Ask of Us? What are the myths we may hold? Read the sharing by our fellow music educators of their experience using DI in their music classroom. When we employ DI in our teaching and learning, we are bringing equity to the classroom, allowing our students to receive the necessary and appropriate scaffolds to experience success. We continue to look at how we can translate the principles of DI into practical use in our music classroom in Tips and Tools for Music Educators. Senior Teacher Rachel Tan shares her journey as a music educator and teacher-leader in Musical Conversations, and how she applies DI in the music classroom.

I wish all of you a meaningful and engaging time with your students and colleagues, connecting, learning and growing together.

Susanna Chau Deputy Director, Music Singapore Teachers’ Academy

for the aRts

You are designing a ukulele module and your class consists of forty students. Within the class there are two students of different readiness levels and music background:

She has been playing piano for 4 years. She can read traditional notation and has performed in concerts. Her father plays the flute and her mother plays guzheng. During last year’s keyboard module, she performed very well.

She has learned to play a few chords on the guitar from watching YouTube videos in her free time. She sings along to pop songs while completing her homework. During last year’s keyboard module, her progress was described as ‘Developing’.

Your plan is to teach them to read the chord charts and perform different strumming patterns to accompany a pop song. The final assessment will consist of students performing and singing a pop song using four chords and an assigned strumming pattern.

Based on the information above, you intend to design an activity that can meet both the students’ learning needs and enable them to reach the learning goals set in the final assessment.

01

In the process of designing the activity, you ask yourself the following questions:

03

How can I design the activity to be interesting , meaningful and worth doing for students with different musical expertise and backgrounds?

02

How can the activity/task be of appropriate degree of challenge to both students?

How do I design the activity to meet the different learnings needs of all forty students in the class?

As teachers, we sometimes prepare lesson modules that seem to meet the average capability of the students. However, once the semester commences, we find some students struggling to keep up and others who are bored and unmotivated. As such, the activities in the lesson module(s) may not be suitable for all students. This is where Differentiated Instruction (DI) comes in.

Carol Ann Tomlinson (2017)1 describes the differentiated classroom as a place that “provides different avenues to acquiring content, to processing or making sense of ideas and to developing products so that each student can learn effectively.”

In this article, we hope to address some of the myths about what DI is and share the impact of practicing differentiation in the music classroom.

1

2 TEDx Talks. (2013, 13 June) The Myth of Average: Todd Rose at TEDxSonomaCounty [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu. be/4eBmyttcfU4

3 Ohalloran, M. (2018) Fair Selection. Faculty Learning Corner, University of Alaska. http:// flc.learningspaces. alaska.edu/?p=4462

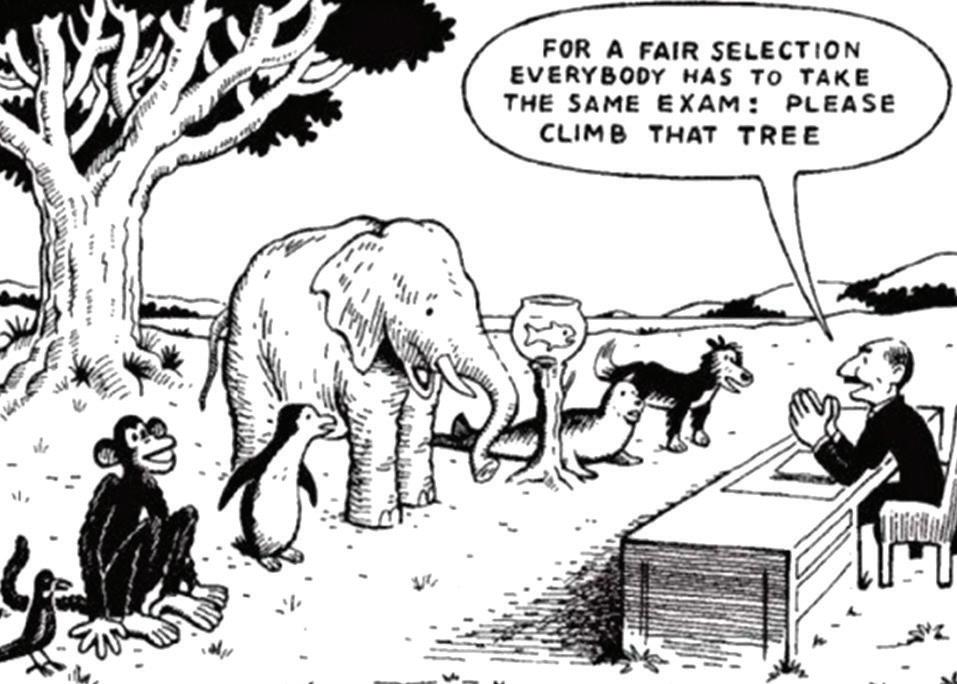

When setting tasks, we pitch the difficulty and teaching approach level based on what we think the average student in a class can handle; and that would become the ‘one size fits all’ as a whole class approach in teaching. This is based on the belief that something in the middle is what the average and high achieving students should be able to do. Students who have difficulties in keeping up with pace of the majority would ideally be assisted by other students once they have completed their own task.

The reality is that there is no “one-size-fitsall” option. In the 1950s, the U.S. Airforce tasked Lieutenant Gilbert S. Daniels, a Harvard researcher in the 1950s, to study pilots and discover the most optimal cockpit design for their fighter jets. He took the measurements of four thousand pilots and the result was that none of the pilots fit the average measurement of all the pilots combined. (TEDx Talks, 2013)2

We tend to focus on pitching the difficulty of the task at what we perceive is the average ability of the students; by doing that, we have actually designed a task to fit neither Student A who strives for more challenges nor Student B who needs more scaffolded help. If we follow an “average” student approach in a class of forty, it is likely that we may have not met the learning needs of all the students. Is

Jessica Chaw (Lead Teacher, Edgefield Primary School) opines when using the “one-size-fits-all” in the designing the lesson approach:

Some students would not be engaged throughout the lessons as most of them would either reach the learning goals very quickly and other students would not achieve them at all. This disengagement happens because students have not taken ownership of their own learning and had not been participative in the tasks and activities planned. And because it is a whole-class approach, many students’ voices would not be heard and areas of strengths and weaknesses would be overlooked. Students would not be motivated to want to ask and learn in such an environment.

Therefore, pitching our tasks using the “one-size-fits-all” average student approach would mean we are not meeting the learning needs of each unique individual. We could instead be thinking about how to set respectful tasks that are stimulating, authentic and meaningful to all students.

So, does this mean we need to prepare a different task for every single student in the class?

Not likely so, as the key is knowing how to differentiate according to our students’ interest and readiness levels.

Getting to know your students is a key part of differentiated instruction

Irene Chan (Lead Teacher, West Grove Primary School) shared her perspective on the concept of planning tasks based on readiness.

It is useful to have a pre-assessment of the students’ prior knowledge before we go about planning DI for a new unit. We can then plan tasks that are more customised within their level of readiness - bearing in mind the objectives of the syllabus and allowing each student to experience small successes to build confidence without compromising the learning objectives. Starting from what they know and building up is a great way to motivate and engage students of all levels.

To differentiate appropriately, we start by knowing our students well. We can get to know our students through activities, surveys, informal assessments, reflections, as well as discussions with the students’ form and subject teachers. From here, we will begin to recognise students with different backgrounds, interests, personalities, learning preferences and readiness levels. Along the way, we continue to assess through formative assessments to update our knowledge of the child’s learning progress.

LESSON 5 CHECKLIST

CHECKLIST FOR TASK 1B

Creating the Rhythmic ostinato

Playing the rhythmic ostinato using body percussion and nonpitched percussion

Playing the rhythmic ostinato with other parts

Our rhythmic ostinato pattern is;

• 2 bars, with 4 beats per bar

• Using choice rhythm values

• At least 3 different rhythmic values

Play the rhythmic ostinato using body percussion and non-pitched percussion instruments

Play the rhythmic ostinato in sync with the song

From this data gathering, we can plan activities while leveraging on these important pieces of information for whole-class, individual and group settings. Sometimes students are grouped based on the teachers’ assessment of their readiness to take up a task and sometimes it could be based on friendship or interest in a project’s theme. By being flexible in grouping the students, it allows us to forge unique paths to meet the needs of every student without needing to plan individual

LESSON 1

TIER 1 TASK CARD

• On non-pitched percussion instruments, create a rhythmic ostinato of 2 bars

• Use crotchet ♩, crotchet rest ��, and quavers ♫

• Perform your rhythmic ostinato pattern with the ‘Great Big House’ song

CHECK THE BOX

F 2-bar rhythmic ostinato

F 4 beats per bar

F 3 different rhythm values

F We have chosen the correct body percussion

F We have chosen the correct instrument

F We are still learning to play

F We are getting better

F We can do this pretty well

lesson plans for each child. This flexibility requires teachers to be open to adjusting instruction to act on difficulties faced by students by ensuring various means for them to express and demonstrate their understanding.

For example, the lesson can start with both Student A and Student B (as mentioned earlier) taking part in a whole-class tuning-in activity. In the following activity, they may be grouped with other students of similar readiness.

LESSON 1

TIER 2 TASK CARD

• On pitched percussion instruments, create a rhythmic ostinato of 4 bars

• Use minim, crotchet, crotchet rest, and quavers

• Perform your rhythmic ostinato pattern with the ‘Great Big House’ song

In a follow-up activity, they are grouped with their friendship groups to support one another’s learning and possibly spark further ideas. At the end of the lesson, the teacher could conduct a formative assessment and consider other types of groupings, to accommodate scaffolding and lesson adjustment each student might require.

LESSON 1

TIER 3 TASK CARD

• On non-pitched percussion instruments, create a rhythmic ostinato of 4 bars

• Use minim, crotchet, crotchet rest, quavers and semiquavers

• Perform your rhythmic ostinato pattern with the ‘Great Big House’ song

This approach gives students a variety of means to demonstrate their learning and for teachers to provide the appropriate support. It is from this cycle of pre, ongoing and post assessing of students’ learning that the teacher can provide options and different pathways for students to be engaged, upskilled and challenged.

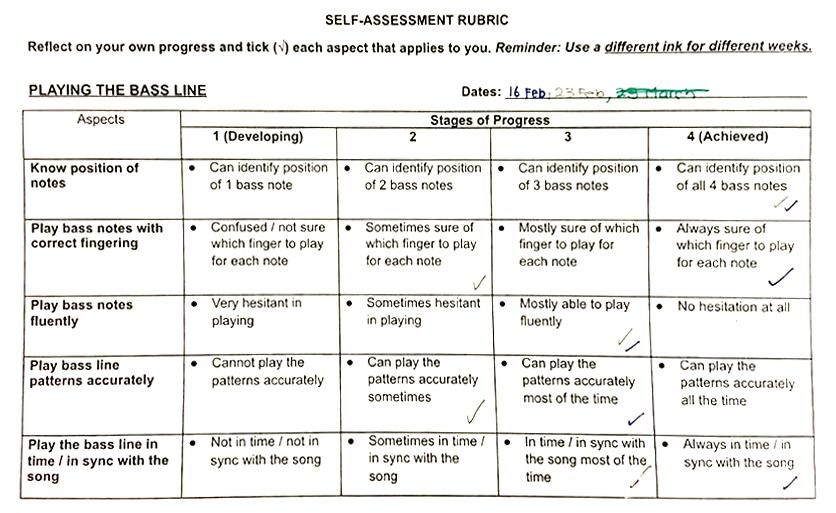

A self-assessment checklist for students that can help teachers make the appropriate adjustments to future tasks

Task cards can be used when teacher differentiates according to students’ readiness for a lesson on rhythmic ostinato

Tier 1: Low readiness,

Tier 2: Middle readiness

Tier 3: High readiness

First and foremost, DI advocates the concept of students’ readiness. It is not about the students’ level of ability and what they can do; readiness is described as the students’ proximity to the specific learning goals.

For example, let’s consider the scenario when planning for a ukulele lesson with playing and singing a song as an ensemble. We may come across a “Student A” who is a pianist with solo performing experience. However, is Student A ready to perform in an ensemble? Will his/her piano technical expertise be comparable to the skills on the ukulele? Can Student A sing and play at the same time? What if we were to ask the same questions for Student B, who has had a different set of music experiences (i.e., playing some guitar chords and singing pop songs)? What would be the readiness level of the 2 students for this module?

In a different scenario whereby the lesson is about songwriting, what would the readiness level of these students be?

Marcus Tay (Queensway Secondary School) had a ukulele module where students had the autonomy to self-assess their readiness level. Based on their readiness level, the student would choose from one of the four Learning Stations of different levels of difficulty to begin the learning.

Naturally, at the start I did not feel comfortable because of the fear that things would go out of control. Teachers want to be in control! But I realised rather quickly that when students have the autonomy to make choices and learn from their peers, they are a lot more engaged and learn to take charge of their own learning. By the end of the module, almost every student had advanced at least 1 zone up.

By planning lessons based on readiness, the students would be working at a task that is just above their comfort level. In short, we are not teaching to the status quo nor the skills the students already know. We are teaching with the intent to provide all students with appropriate degrees of challenge in terms of content and understanding.

The teacher will plan teaching actions and/or activities when students demonstrate higher or lower readiness instead of constantly reacting. Providing additional work should be intentional from the beginning and not a reaction when students finish earlier than expected.

Tay,

Each zone features a strumming pattern can be learnt from online videos (which can be accessed via QR codes and PLDs)

Self-Directed Learning

Students move up through the Zones after learning the strumming pattern and selfassessing their readiness to move on. Students have the option to move to a lower zone if they feel they need more reinforcement.

Formative Assessment

Before moving to a new Zone students need to check-in with the teacher or student mentor. Students are appointed as student mentor after passing Zone 4. They can help to assess or mentor classmates at each zone.

Tiered complexity in the strumming pattern from zone to zone

Example of Learning Stations, where students determine the level of challenge they want to take on

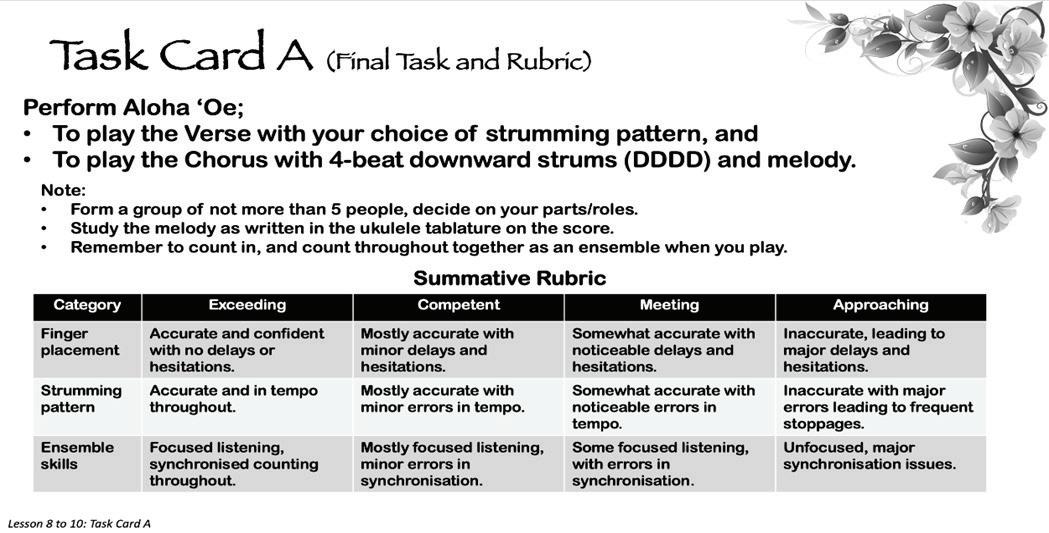

And now we must address the ‘elephant in the room’; if we have different tiers of assignments and different groupings, how do we assess fairly? For example, Student B was assigned a task that has less complexity in terms of musical challenge. On her final performance she achieved a summative grade that is higher than Student A who had been assigned a more complex task. Is this fair?

For a start, let’s consider the purpose of summative assessment – to allow students to demonstrate what they have learnt and understood according to the learning goals of the lesson module. It should not include a facet involving comparison between students.

The need to compare subverts the more authentic purpose of learning and being aware of what needs to be done to reach greater heights. The summative grade is meant to be an indication of the milestone of what each student has achieved and is neither the end of learning nor a ranking between classmates. Essentially, it is a means for equity in learning. This constant cycle of pre and ongoing assessment is to enable the teacher to challenge students with each new task through an uplifting and holistic approach. The assessment rubrics must be carefully worded so each student feels like improving themselves and is motivated to aspire to the next level of achievement.

Advocate student-agency by providing pathways to succeed

Loo Teng Kiat (Lead Teacher, Zhenghua Primary School) shared on the students’ learning when teaching with a DI approach:

The (students’) level of understanding met my expectations and went beyond. This was mainly due to healthy competition and immense support between the children and their peers. The rubrics provided helped to strengthen that understanding, giving them the confidence to correct and help their peers improve. The rubrics were also helpful for the individuals to gauge their progression, and to be aware of the next steps to take to elevate themselves to a higher level of performance.

01

Example of a task card for students of a certain readiness, but the summative rubric is the same for all levels of readiness

02 DI is about ensuring every student receives what he or she needs to succeed.4

4 Maguire, A. (2016) Equality vs Equity. Interaction Institute for Social Change. www. madewithangus.com

Firstly, while we consider students’ varied interests and abilities in our planning, we must still abide by the clear learning goals we set at the beginning of each module. With guidance from the Music syllabus, we should continue to unpack what we want the students to know, understand and be able to do in Music lessons. Planning with the end in mind is not a novel idea; it is what we do along the way that makes the ending meaningful.

learners that is willing to balance their individual needs to the learning needs of the class.

The DI approach is a new kind

Secondly, we would also consider providing a positive and safe environment; a holistic haven where students feel safe and accepted and are not afraid to voice out ideas and challenge one another to do better. The classroom encourages them to take responsibility of their learning and recognise how they might contribute to collaborative group work. DI asks us to consider building a community of

Most importantly, the DI approach is a new kind of fairness. Its concept of fairness is ensuring each student receives what he or she needs to succeed, and not whether all the students receive the same amount of support, nor whether students are given the same assignment.

And while that task can seem daunting, Tomlinson shared the following statement during a webinar in March 2021:

Differentiation doesn’t ask us to do all of these things tomorrow. Rather, it asks us to work day by day

Over the span of a career

To create classrooms that lift up – inspire – every student in our care. It asks us to get a little better tomorrow than we were today.

In summary,

do keep these six principles in mind as you embark on your DI journey. They are as follows:

CLEAR LEARNING GOALS

Use of pre-assessment formative and summative assessment to diagnose, facilitate and measure learning.

Learning goals are clearly articulated to focus on the learning conditions and expected criteria and address essential understandings and skills.

01 04 02 05 03 06 PRE AND ON-GOING ASSESSMENT RESPECTFUL TASKS

FLEXIBILITY

APPROPRIATE DEGREE OF CHALLENGE

Tasks are pitched at a level that is just right and facilitates students’ individual success.

To read more about the six principles of DI

Tasks are stimulating, worth doing, meaningful and emphasis learning and thinking for all students.

Teachers are open to providing various means for students to express and demonstrate learning.

Students understand differentiation is about balancing individual and classroom learning needs.

Here are some thoughts from the music teachers using DI in their classrooms

~ Curate your materials (e.g., instructional videos, diagrams) and tailor them to your activity. For example, if you are using tiered activities, make sure that the materials and tasks in each tier are challenging but at the same time attainable.

~ The tasks across the tiers should have a coherent progression so that students can logically advance from one tier to another and feel motivated to improve their musical skills.

~ If you cannot find suitable resources for very specific learning objectives, do not be afraid to make your own.

Teacher, West Grove Primary School

~ Differentiating the learning process includes all of the varied instructional strategies, activities, tools, and resources that help students meet the learning goals i.e., knowledge, skills, concepts, and habits that the teacher wants all students to learn.

~ Design tasks that have the same learning target but appeal to different learning styles to ensure every student meets the learning target.

~ Have the summative assessment of the learning objective in mind, and based on the readiness of the students, design activities that would help lead the groups towards that final assessment using their preferred mode of presentation.

~ When students experienced success with their group members, they were motivated to help one another and contributed to the final product.

~ They built on one another’s strengths and encouraged themselves to better their performance. This led to a more dynamic learning environment for the whole class.

Teacher, Zhenghua Primary School

~ To my surprise, my students seemed to enjoy the independence and the trust to learn on their own while knowing that the teacher is always there to help.

~ Even when that the teacher was not available, they knew they could turn to their peers who might share a similar learning profile. They would be able to find the classmates to help them with the tasks at hand.

~ There were no problems or issues for the students to collaborate and help each other even if they were of different genders.

Teachers are constantly making adjustments in class stemming from our innate desire to help our students to grow – thinking of strategies to better engage students, providing support and help resources, and giving individual feedback. When we are doing DI, we are approaching it in a proactive and structured manner. Differentiated Instruction is simply effective teaching.

For information on additional DI strategies, please refer to Tips & Tools for Music Educators. For Primary teachers, a DI Resource Thumb Drive has been sent to every school in January 2022.

Full Subject-Based Banding (Full SBB) in Secondary Schools is part of MOE’s ongoing efforts to nurture the joy of learning and develop multiple pathways to cater to the different strengths and interests of our students. Its aims are to develop the diverse strengths and interests of our students, and to ensure that they develop to their fullest potential regardless of starting points.

With Full Subject-Based Banding (Full SBB), we are moving towards a secondary school education where students learn each subject at the level that best caters to their overall strengths, interests and learning needs. Under Full SBB, there will no longer be separate Express, N(A), and N(T) courses, and students will be in mixed form classes taking subjects

of different levels (G1, G2 and G3) where they can interact with peers of different strengths and interests.

Full SBB has been piloted in 28 Secondary schools starting from 2020 and will be implemented in all secondary schools by 2024.

Under Full SBB, MOE will expand SubjectBased Banding (SBB) beyond the four PSLE subjects, to allow eligible students to offer Humanities subjects at a more demanding level from Secondary 2. Other subjects such as Art, Design and Technology, Food and Consumer Education, and Music will be offered as an accompanying set of Common Curriculum subjects at lower secondary.

The music classroom is an ideal environment for the realisation of the intent of Full SBB as music classes have always been of mixed musical abilities with teachers catering to different music learning needs of the students. Music also thrives and evolves when people of different musical skills, perspectives and backgrounds make music together. With Full SBB, Music will be offered as a subject common across all streams and would be a

Creating a Safe and Inclusive learning environment and building Positive Classroom Culture

Facilitating Learning for Heterogeneous Classes and Developing Student Ownership for Learning – Planning for Differentiation and Inclusion

fitting avenue for class bonding and social mixing amongst students. To cater to the increased diversity in Full SBB music classes, there are three areas we can develop for teaching Music in Full SBB music classrooms as detailed in the table below. In the next section, we explore how some Full SBB music teachers used these areas as considerations to guide their design and delivery of instructions and assessment in their music lessons.

• Cultivating a positive, inclusive learning environment

• Developing, implementing, and strengthening routines

• Strengthening Differentiated Instruction (DI) strategies

• Infusing elements of gamification in the design of lesson modules

1. Teacher-student interactions – Jermain Cho from Edgefield Secondary

Designing Assessment Tasks well

• Non-formal and Informal Learning Approaches to Music teaching

• Formative Assessment

• Differentiated Tasks

2. Dikir Barat and lyric composition – Tabitha Vicky from Riverside Secondary

Singing and Ukulele module ‘Music Passport‘ (2020) –Francesca Peck and Lim Xi from Greendale Secondary

1. Pop Band module – Samuel Soong from Evergreen Secondary

2. Keyboard Challenge module – Jeremy Lim from Clementi Town Secondary

1. Keyboard Challenge module – Jeremy Lim from Clementi Town Secondary

2. Singing and Ukulele module ‘Music Passport‘ (2020) – Francesca Peck and Lim Xi from Greendale Secondary

Learning of Bendera Kita via the Non-Formal and Informal Learning approaches during the Full SBB Music Workshop in April 2022

1. Pop Song covers on GarageBand – Eunice Chua from Montfort Secondary School

2. Keyboard and Ensemble playing – Teh Jane Khim from St Anthony’s Canossian Girls’ School 1

At Edgefield Secondary School, Jermain believes in creating an inclusive music classroom that accounts for students’ different music interests, personalities, abilities, learning styles and class culture. As part of the preparation for setting up an inclusive learning environment, Jermain advocates for being “streamblind” – not knowing students’ streams – for teachers to remain impartial in their interactions with students. He also makes it a point to model the development of positive teacher-student interactions:

“It is important for me to follow each student’s train of thought and give respect/value to their opinions during interactions or when giving feedback on their work. I am mindful of my choice of words, language and tone employed, speed of speech and make it a point to look students in the eye when speaking. This is then reciprocated in student-student interactions as they become more positive and respectful, which will channel good vibes into creating an inclusive class.”

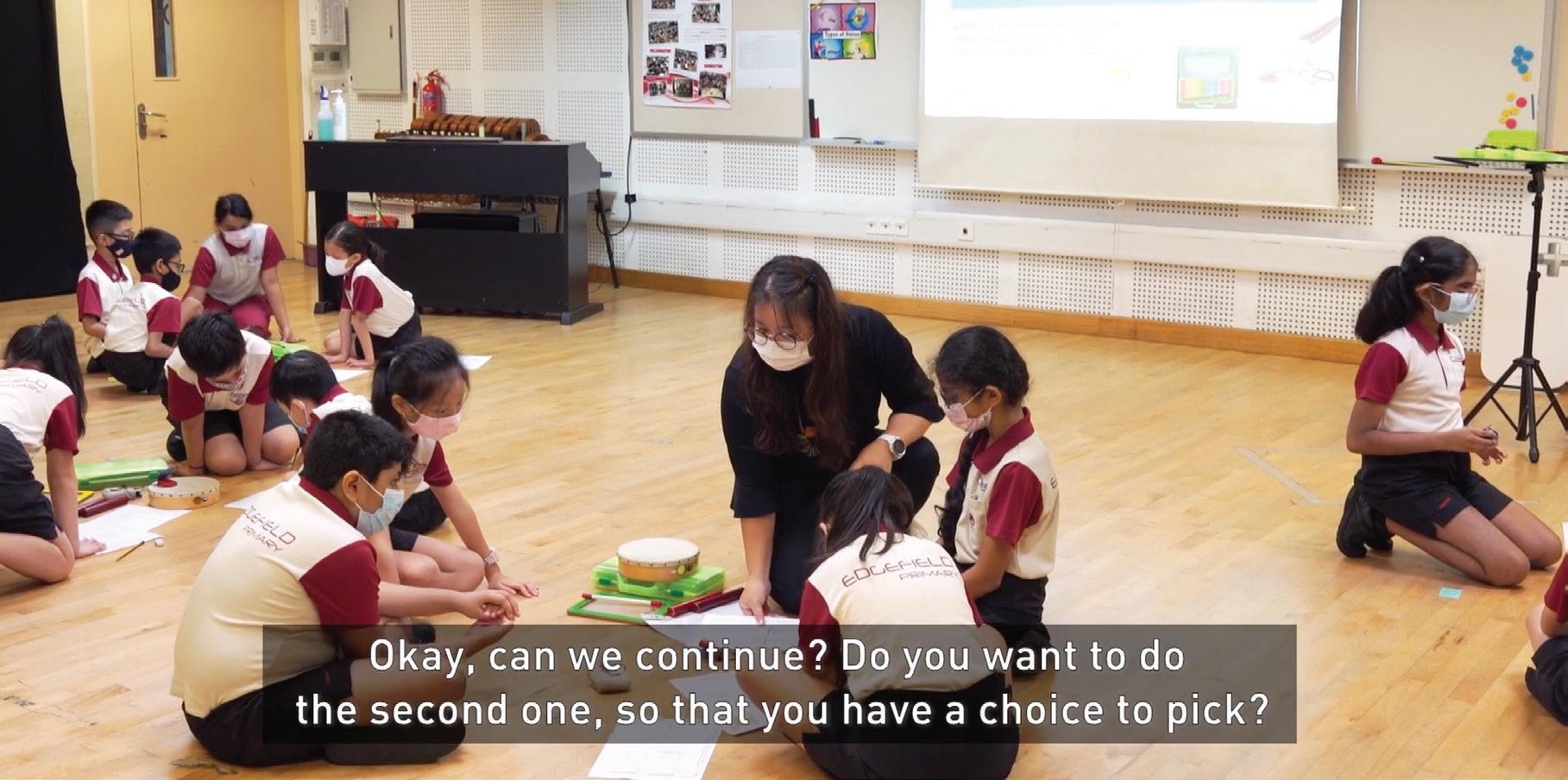

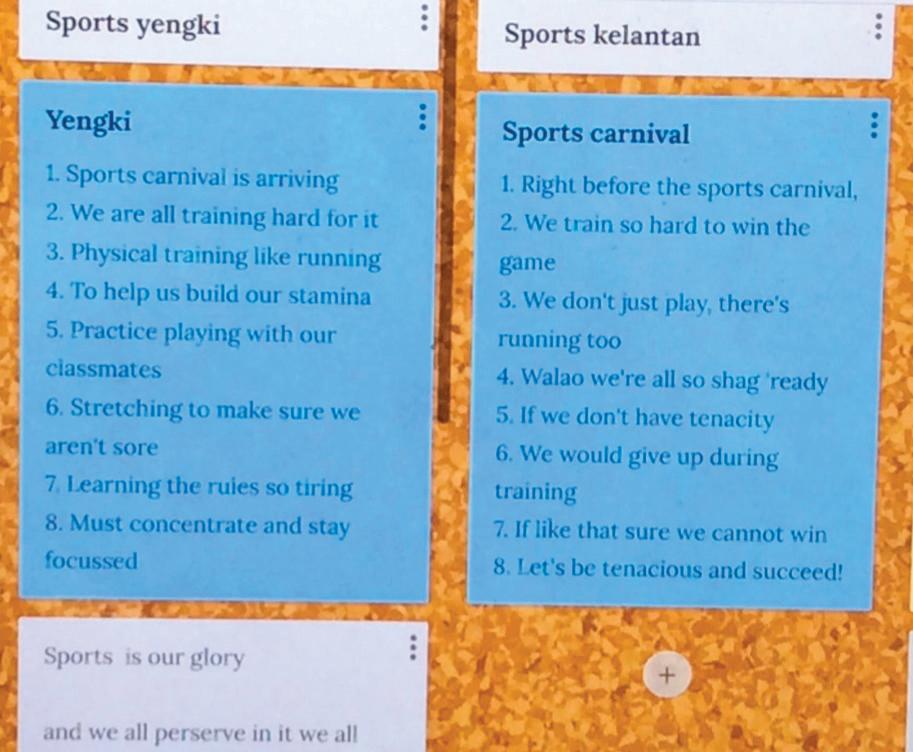

At Riverside Secondary School, Tabitha cultivated a positive learning environment in her music classroom by fostering teacher-student and student-student bonds through collaboration and the inculcation of values in a Dikir Barat module. The genre of Dikir

Barat lends itself well in this endeavour as its roots are in building community and fostering unity. In gender-based teams, groups brainstormed lyrics about values like tenacity. Groups chose different sections of Wau Bulan to perform, which they later combined to form the class’ version of Riverside Wau Bulan. This task not only allowed students to learn musical concepts such as lyric writing, word stress, the genre of Dikir Barat, and performing in both small and large group settings, but also allowed students to experience the camaraderie in preparing for the Riverside Wau Bulan performance.

During the Full SBB Music Workshop in April, participants shared strategies they had adopted to provide students opportunities to bond, participate in activities and create a safe and inclusive environment.

I encourage students to explore alternative notations and digital notations using the Beat Sequencer in GarageBand when they work on developing pulse and rhythmic creativity for their Rap project. This provided for students’ varying entry levels.

Anderson Secondary School

Students improvise rhythms on names of their favourite drink and food, thus bringing a piece of themselves into music-making.

It reflects the myriad of ways which musicians learn music, thus showing how inclusive music can be.

Ngee Ann Secondary School

I find that giving students peer and/or grouplearning opportunities and time to work on short tasks like improvising a rhythm increases the quality of the product, as it is a safe space for students to try and pool ideas together, as opposed to an individual improvisation.

Juying Secondary School

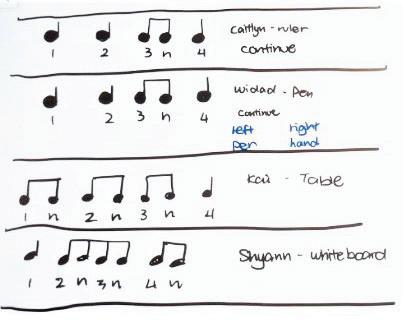

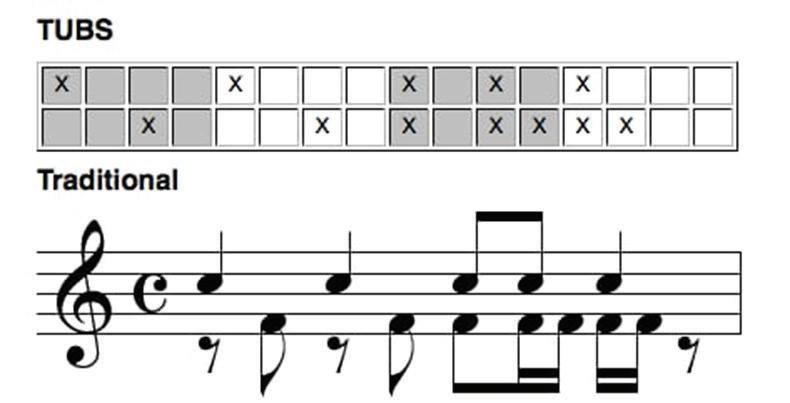

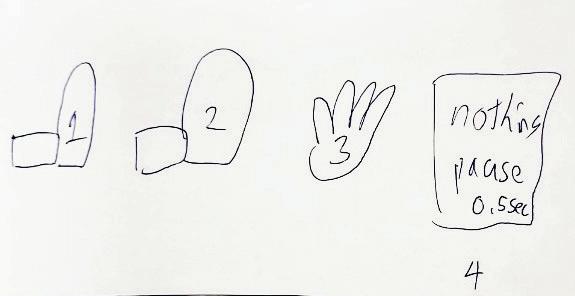

In our STOMP rhythm module, students are given the choice to document their STOMP rhythms in four ways:

We want to encourage the use of different tools to document music as it allows for student agency and ownership in their learning. It reflects the myriad of ways which musicians learn music, thus showing how inclusive music can be.

Storage of instruments and materials for the Passport module

1 Colvin, G., & Lazar, M. (1995). Establishing classroom routines.

In A. Deffenbaugh, G. Sugai, G. Tindal (Eds), The Oregon Conference Monograph 1995, Vol. 7, p. 210.

In a Full SBB music classroom, routines should be in place and further strengthened to provide diverse learners structure so that students know what to expect and what is expected of them. It also gives them the opportunity to practise responsibility and self-management skills and helps to create a shared ownership between the teacher and the students (Colvin & Lazar, 1995)1

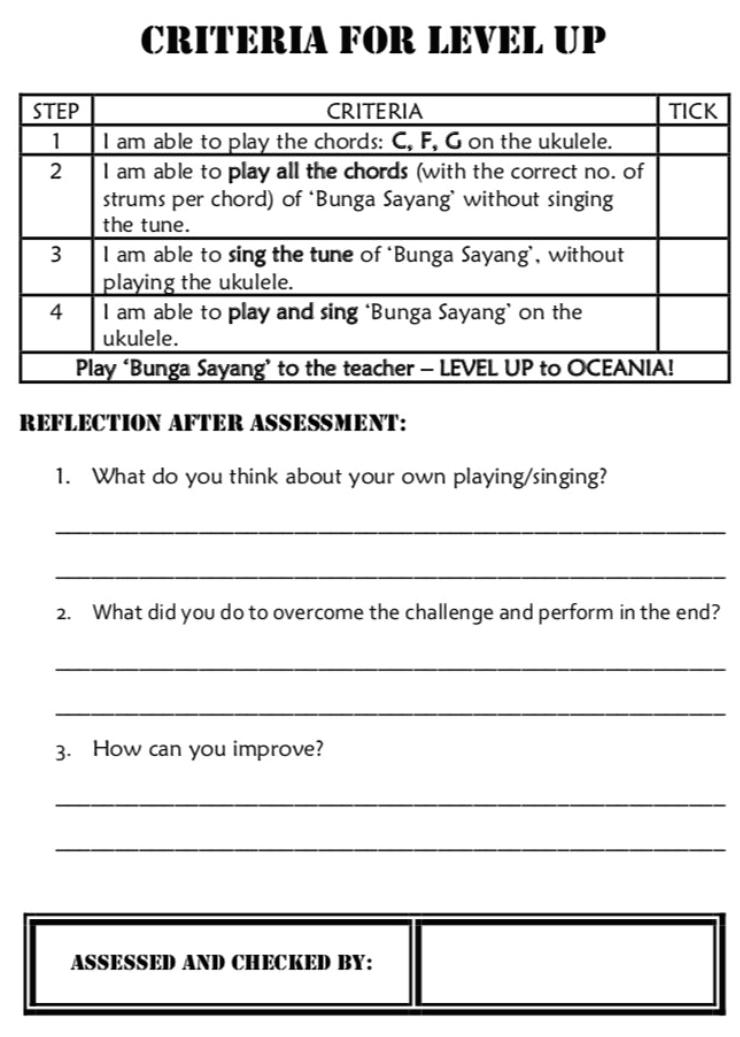

In Greendale Secondary School’s Singing and Ukulele module ‘Music Passport’ (2020), Francesca and Lim Xi developed and implemented routines for collecting, returning their instruments and materials, and ukulele tuning. As the weekly routines are systematic and consistently implemented, students are able to complete the routine quickly and more time was available for teaching and learning.

Opening Routine for Ukulele Lessons

Ukulele Tuning Routine

Closing Ukulele Routine

• Students collect their ukulele, bag, tuner and cleaning toolkit by rows

• Students tune their ukulele individually

• The teacher leads the class to complete the ukulele tuning routine (see below).

• After individually tuning their ukuleles with the help of a tuner, they individually pluck the open strings.

• The class listens to each student’s four open strings like a roll call and assesses which strings need to be further tuned.

• The teacher provides quick feedback on the tuning.

• Students clean their ukulele with a cleaning kit.

• Once complete, they return the kit, ukulele, Passports and reassemble in the class format.

• The teacher plays a song in the background to help students understand how much time they have for the routine as their routine needs to be completed when the music ends.

With increased diversity within each class due to the implementation of Full SBB, the need to plan for Differentiation and Inclusion becomes more apparent in order to support diverse learning needs. Differentiated Instruction (DI) respects that every student has different needs and different strengths, and therefore there is a need to devise differing strategies to draw out the best in every student, in order that everyone would feel valued and included.

At Evergreen Secondary School, Samuel values making every student feel included by cultivating a cohesive environment where students uplift and help each other based on their strengths. There are clear musical role structures in a student band such as timekeeper (keeping the beat and driving the music through percussion), highregister chord player, mid-register chord player, low-register chord player and singer. Students contribute based on their strengths and abilities, and this encourages them to work as a team to complement each other.

Sounding

Sounding

Musical Role Structures in a Pop Band

Low Sounding

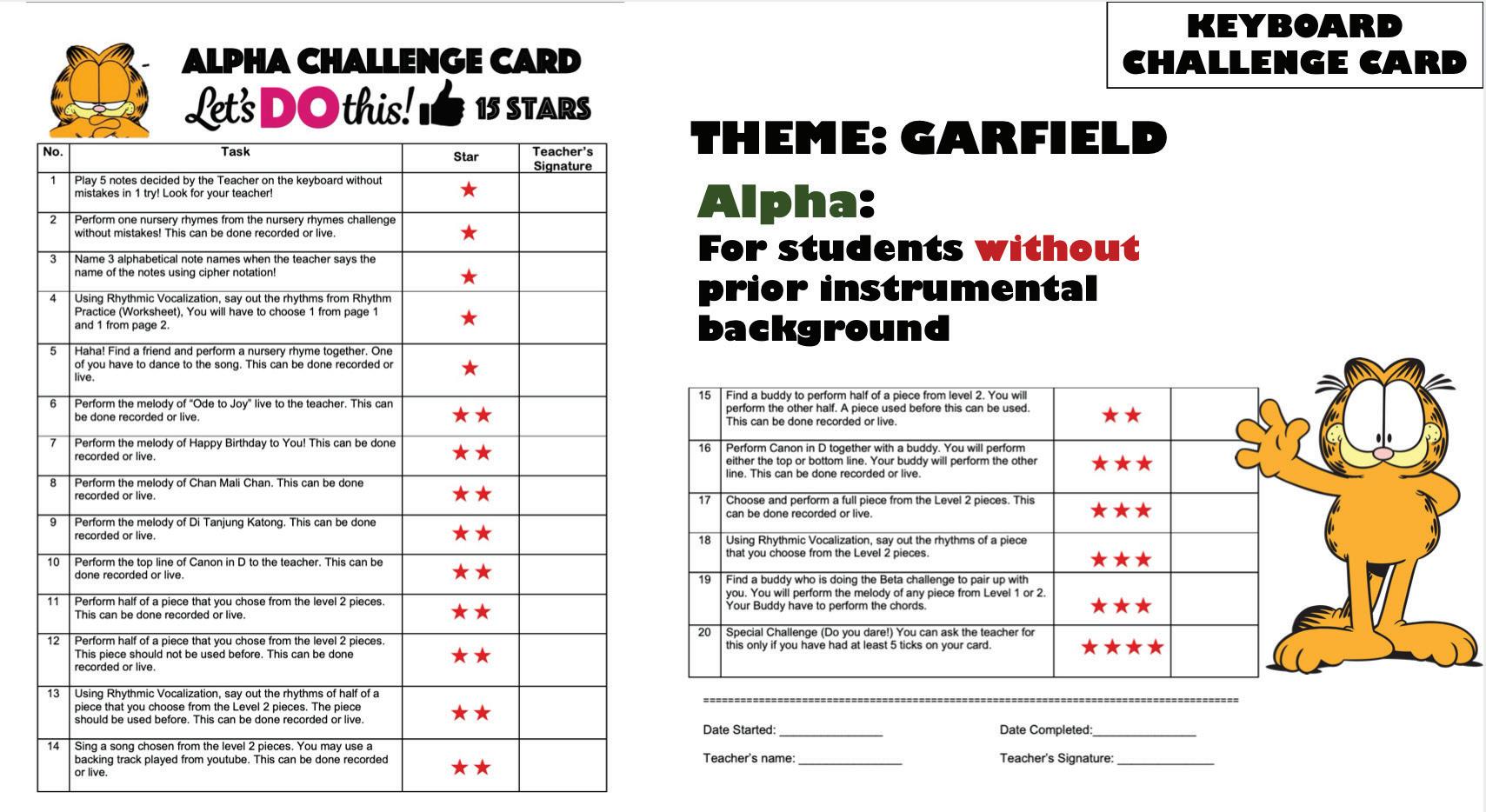

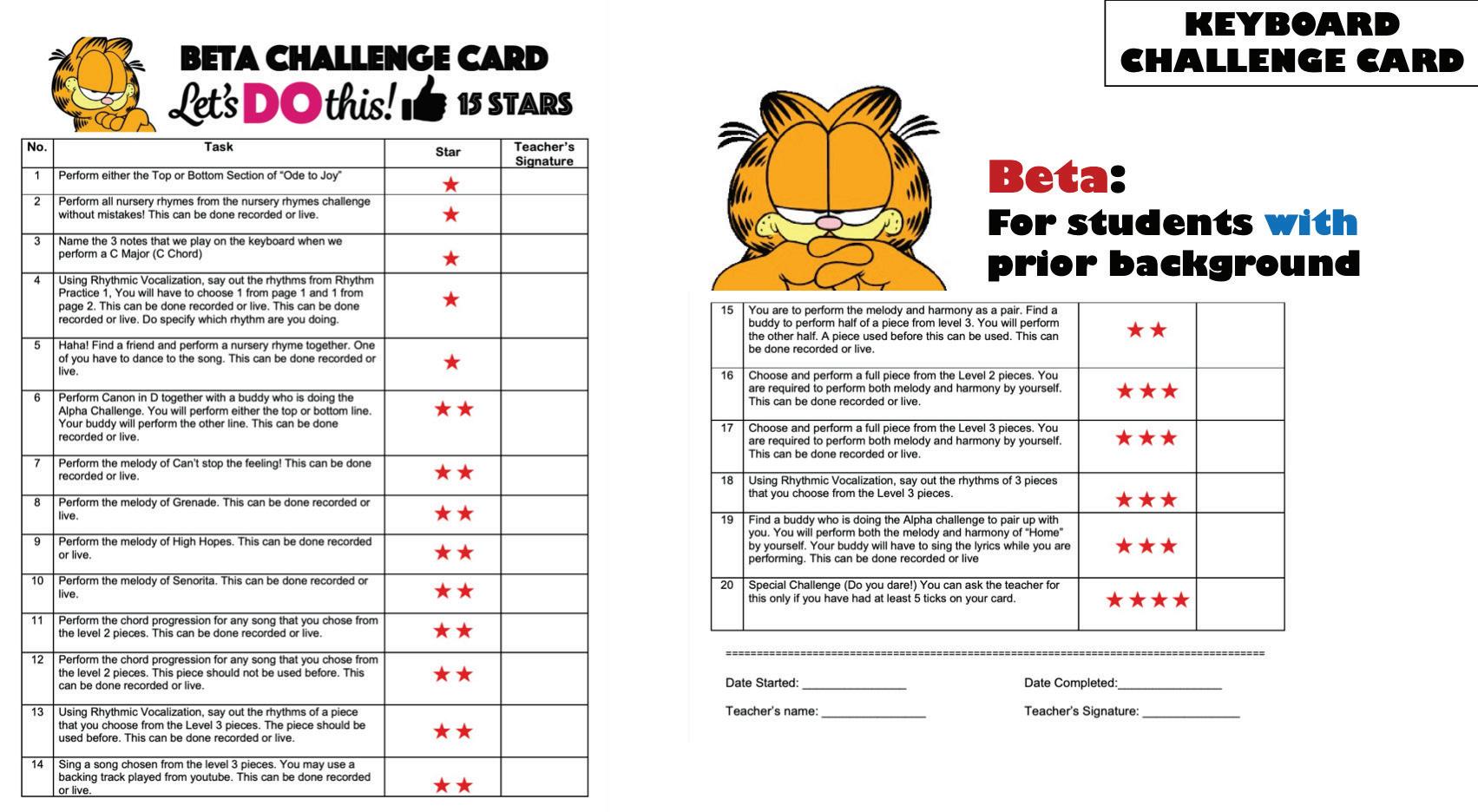

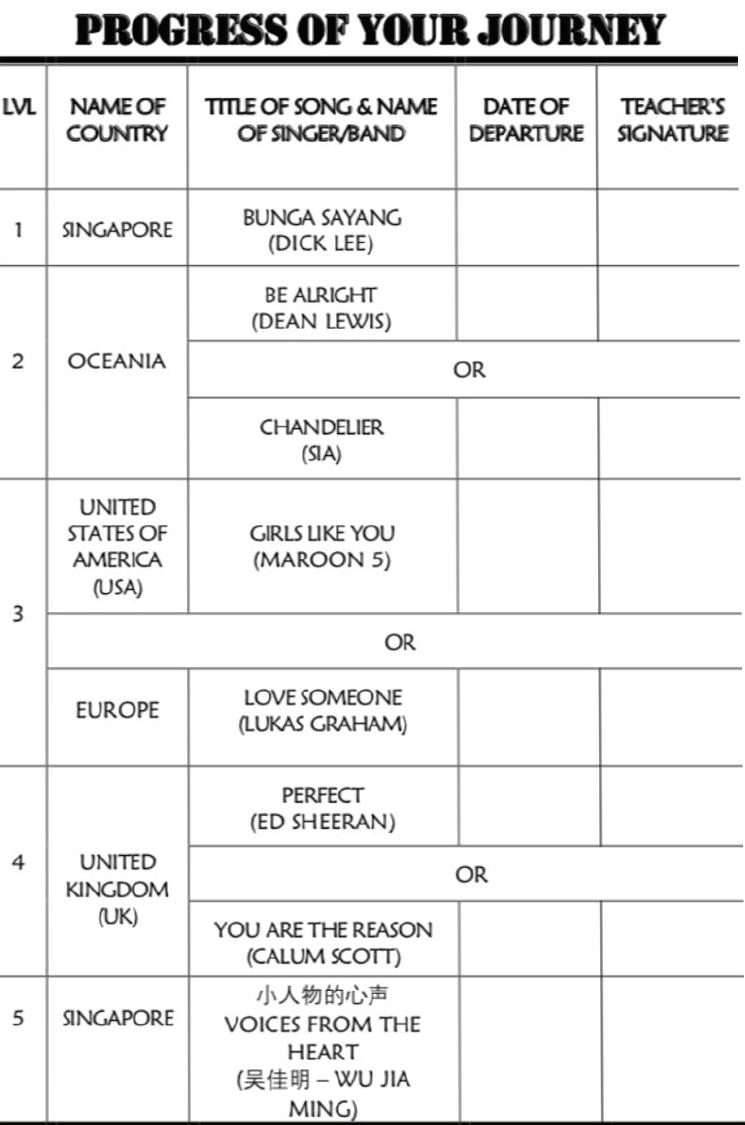

Jeremy used DI and gamification strategies in the design of his Secondary 1 Keyboard Challenge module for his Full SBB music class in Clementi Town Secondary School2 He was motivated to do so as he wanted to ensure that all students, despite varying readiness levels in keyboard playing, were optimally challenged and value-added, and thus feel included. Previously, some students with no background in keyboard or piano were interested but felt overwhelmed by the perceived degree of challenge, whereas others with background were unmotivated as they did not feel challenged.

The process started with Jeremy getting to know his students’ readiness level in keyboard playing by conducting a pre-survey. Students without background in keyboard playing would take the Alpha Challenge and students with background would take the Beta Challenge. The first four lessons were taught in a whole class setting to establish rules, routines and expectations, and provide clarification and to offer adaptations to accommodate the different ways by which students may have acquired keyboard playing skills and knowledge.

2 Lim, J, (2022).

‘Differentiated Instruction for Keyboard Module’ in STAR (Ed), Sounding the Teaching VI: Imagining Possibilities. p. 246-261

(students without keyboard/piano background) and Beta Challenge

Students will learn to relate rhythms to words through a Drum Circle activity, followed by teacher consolidation and reading rhythms.

Students will perform simple pieces using rhythms to words and cipher notation through the Nursery Rhymes Challenge

Students will perform two songs with the five finger positions, and with sensitivity to tempo and pulse:

• Ode to Joy

• Happy Birthday

Students move between different five finger positions and finger-over positions on the keyboard through duet versions of Canon in C (arranged by Jeremy and originally Canon in D)

(students with keyboard/piano background)

Teacher will provide clarification on different ways the students have learnt to read rhythms (e.g., Western notation, using numbers etc.)

Teacher will provide clarification on the different ways students have learnt to read notes (e.g., writing alphabetical note names, reading staff notation, using solfège etc.)

Students have the additional side challenge of performing dyads or chords in simple accompaniment patterns to accompany the Alpha Challenge players

Students are empowered to take up the additional challenge of being teacher assistants to Alpha Challenge players

Subsequently, students would embark on their respective Alpha or Beta Keyboard Challenges. The Alpha Challenge consists of curated Level 1 and 2 pieces, and Beta Challenge consists of curated Level 2 and 3 pieces that have been arranged to suit the respective needs of the students in each Challenge. Students work their way through their respective challenge cards and demonstrate their learning either by performing live or recording, and subsequently uploading their performances to the class’s Google Drive folder. The different challenge tasks also encourage collaborative music-making among students, regardless of whether they are taking the same or different challenge.

KEYBOARD CHALLENGE CARD

KEYBOARD CHALLENGE CARD

Jeremy found an increase in students’ intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, agency and enjoyment of music lessons. The students appreciated the variety of means used to represent music (e.g. Cipher notation, Alphabetical note names), their choice to choose which challenge tasks to complete, the time and space for self-practice, and enjoyed the gamification elements (please refer to the next section on p. 24 for more information on gamification)

The students appreciated the variety of means used to represent music, their choice to choose which challenge tasks to complete, the time and space for self-practice, and enjoyed the gamification elements.

3 Dichev, C., & Dicheva, D. (2017).

Gamifying education: what is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain: a critical review.

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 9

Gamification elements

Gamification in education is an approach for increasing learner’s motivation and engagement by incorporating game design elements in educational environments (Dichev & Dicheva, 2017)3

to read more about

Gamification for learning

Teachers found that students’ levels of ownership, self-efficacy and motivation increased in Greendale Secondary School’s Informal Learning-based Music Passport module (2020) by infusing elements of gamification (e.g., Story, Frequent Feedback, Rewards/Incentives, Increasing Complexity, Visible Progress) and DI strategies.

The students each have a music ‘Passport’ comprising five levels, through which they take on the persona of a pop band touring around the world. At each level, they are required to perform as a group (play the ukulele and sing) based on certain success criteria. Through a combination of self-assessment and teacherassessment of each group’s performance, students then progress to the next level. Successful ‘bands of student popstars’ are awarded a stamp on their passports and are handed the ‘visa’ (song sheet) to the next

Rewards/Incentives

Increasing Complexity

country (level). At each level, students are given a choice between two songs from popular culture which they are familiar and identify with. They will then listen to the original song and learn how to play and sing by emulating the recordings. Students can learn at their own pace to progress across the five levels and have the flexibility of time in learning and practising based on their readiness.

The teachers are gratified to see an increase in students’ ownership, self-efficacy and motivation as they help their groupmates to improve on their craft and devise solutions and practice methods to ensure the group can advance to the next level. For instance, students may suggest that some members anchor certain chords or strums, so that a successful performance as a group can be achieved. Students uplift each other and leverage on each other’s strengths in the process of levelling-up.

Non-formal and Informal Learning Approaches are examples of inclusive music pedagogies that would work well in a Full SBB music class where learning processes may be less linear since music learning takes place when students are immersed in music and musical practices. The table below summarises the key characteristics of the two approaches:

APPROACH NON-FORMAL APPROACH

Origin

Key characteristics

Derived from community contexts of music-making

• Teacher as facilitator

• Empowerment through co-construction of ideas

• Aural-oral processes

• Large group activities, friendship setting

• Open environment, trust, respect

Derived from understanding how pop musicians learn (Green, 2001)

• Learning is self-directed

• Empowerment through choice (e.g., choice of music, instruments, band)

• Learning music aurally (or through videos)

• Working in (small) friendship groups

• Working on real world music

To find out more about Non-Formal Approach and Informal learning

During the Full SBB Music Workshop in April, participants experienced learning Bendera Kita via the Non-Formal and informal approaches. Below is a detailed description of the nonformal approach.

Tune-in: Improvisation of 4-beat rhythms in a circle to lead into creation of drum fills

~ Call and response with teacher-facilitator using body percussion to energise and aurally prepare the students

~ Students are given time to work on creating a 4-beat rhythm using body percussion

~ Empower students to perform their rhythm and the class echoes the rhythm while keeping the pulse

~ Lead students to perform a drum groove and then their own rhythm during the fillin, to lead to the development of the drum groove

~ Students are invited to contribute their rhythms to form the fill-in of the class drum groove

~ Some students are invited to play the class drum groove on cajons while the rest of the class performs with body percussion

~ Teacher-facilitator aurally prepares the class by introducing 4 notes which the students would be improvising on through call-and-response

~ Students improvise an 8-beat / 2-bar riff using keyboards/virtual instruments on GarageBand consisting of 4 notes

~ Students are given time to work on their riff while the backing track is playing in the background

~ Students are invited to contribute to the class riff by playing their own 8-beat/2bar riff to make up the full 8-bar class riff. The teacher-facilitator can suggest or ask for modifications. The 8-bar class riff is notated on the board through graphic notation and note names.

~ The class performs the riff together with the backing track

~ The teacher-facilitator teaches the chorus of Bendera Kita by rote and the class then sings with the backing track

Putting the class performance of the chorus of Bendera Kita together

~ Students choose their preferred instrumental role (guitar, keyboard riff, percussion, vocals) and are given some time to practise.

~ Teacher-facilitator leads the rehearsal by layering the roles so that students can hear how they interact. It also allows the teacher-facilitator to check on each instrumental role before the whole class plays together.

Participants then participated in Informal Learning experiences by practising and performing a section of Bendera Kita in friendship groups. Participants were supported with lead sheets, audio stems and guide videos as references that were made available through the SLS platform.

Participants

To find out more about Assessment Literacy and to access assessmentrelated resources

4 Hattie, & Timperley, (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), p. 81-112

An example of formative assessment through a Checklist

Assessment for learning and assessment information allow both teachers and students to make continuous improvements to teaching and learning. In addition to interpreting assessment information and adapting instructional practices to address learning gaps, teachers can also guide students to use assessment information to improve their own learning. As students learn to self-assess and self-regulate, they will be equipped to become selfdirected learners who are motivated to learn for life.

One way to increase self-directed learning is to involve the learner in the assessment by developing students to be critical assessors. This can be done through checklists and rubrics with prior modelling of success criteria in class. The checklist or rubrics help students develop the ability to assess themselves and provides Feed Up (Where am I going? i.e., the goals), Feed Back (How am I going?) and Feed Forward (Where to next?) (Hattie & Timperley, 2007)4 .

Playing melody on instrument

I am able to play the correct notes

I am able to play the correct notes in time

Playing chords on instrument

I am able to play the chords I am able to change the chords in time

Assessment Tasks in a Full SBB music class should continue to engage and challenge students through respectful tasks by catering to a wide range of student strengths, interests and needs. The next section of the article will highlight the thought processes behind

I am able to play confidently and expressively

I am able to play chords together with my group

the design of differentiated summative tasks and formative assessment in Full SBB music classrooms, as well as practices that build positive classroom culture and create a safe and inclusive learning environment by two Senior Teachers (Music).

Senior Teacher (Music)

Montfort

Secondary School

In our school, teachers who teach the common curriculum subjects are encouraged to be ‘stream-blind’ (i.e., not knowing students’ streams), therefore removing labels and not forming any biases in the way we approach each student. It is heartening to see the students embracing this spirit as the friendship groups formed during music lessons are usually mixed between streams.

I also try to ensure that students have enough opportunities to work with different people by changing pairings and groupings once every few weeks. Students are also allowed to choose their pairs before merging with other pairs to form bigger groups so that they have a familiar friend in a big group setting.

PRINCIPLES WHICH GUIDED THE DESIGN OF EUNICE’S DIFFERENTIATED TASK: Create a song cover with a melodic line, chords and percussion on GarageBand using iPads VALUE STUDENT CHOICE TASKS SHOULD BE OF VARYING DIFFICULTY LEVELS TO OPTIMALLY CHALLENGE STUDENTS

~ Students voted for their favourite songs from a curated list ~ The class then decided on 5 songs ~ The selected songs are grouped according to difficulty level

~ A new layer (melody, harmony, rhythm) is introduced to the students each week, and resources are posted on Google classroom for students’ reference

~ Students spend the first few minutes of the lesson exploring what had been taught for the week, then proceed to complete their task. Students can choose to work on their project in any order

4

5

STUDENTS HAVE THE CHOICE TO DO MORE THAN WHAT IS REQUIRED

~ Students are allowed to work on a song that is not in the list after consultation with the teacher. They would also be provided with resources.

TIMELY FEEDBACK AND SUPPORT ARE PROVIDED

~ Students are given weekly feedback on how to improve

~ Students are aware of classmates who are working on the same song and are encouraged to find a knowledgeable other to lift and guide them

Senior Teacher (Music), St. Anthony’s Canossian Secondary School

OVERVIEW OF JANE’S KEYBOARD AND ENSEMBLE PLAYING DIFFERENTIATED TASK:

Performance of two instrumental parts (either keyboard, bass guitar or drum) in a pair with the backing track of the students’ song of choice from a curated list

As students were given the option to choose their song, some of them chose songs which were quite demanding for their current readiness level. As they were motivated to continue to work on their chosen song, I did not discourage them by making them change to an easier song. Instead, they were provided other options like only working on the chorus of the song or using simple accompaniment patterns. This is to ensure that they continue to be engaged, and to encourage them to pursue their interest and be resilient.

I observed an increase in student motivation and engagement as they were excited that they could choose their own songs. As the songs chosen were pegged to different levels, students with lower readiness levels were not pressured to attempt the higher-level songs. The students with higher readiness were generally very selfdirected using the resources provided. They were able to proceed independently, and some were motivated to go beyond the required task criteria.

1 2

~ Students complete an online survey on their keyboard background and their favourite songs

~ Based on the survey, teachers paired lower-readiness learners with higherreadiness learners

~ Students are taught rhythms using the drum kit patch on the keyboard first as this would allow students of different readiness levels to learn at a similar pace; students with keyboard background would often be able to play their classical exam pieces well but may not be able to play drumbeats and bass riffs in a pop style.

~ They are then taught notes on the keyboard for playing bassline patterns

During the teaching of the harmony / chords and accompaniment patterns, higher readiness learners in keyboard playing were offered challenges:

a. Play chords with the right hand and bassline with the left hand

b. Play chords with more challenging accompaniment patterns and chord inversions

We also used formative assessment to develop students into selfdirected, critical assessors in the form of weekly checklists. This allowed students to gain familiarity and deepen their understanding of the success criteria through the weeks of practice.

I observed that there was an overall increase in my students’ motivation to learn the keyboard. Even students who were initially reluctant or lacked confidence felt encouraged to learn and practise to improve their skills in playing when they experienced success. They felt a sense of achievement when they could play along to the given backing track of songs.

~ Students are given time for individual practise using their headphones before playing as a class

~ Pairs will practise together with the backing track of their chosen song using the mixer and headphones

~ Low-readiness learners could choose to play the role of a drummer or bass guitarist to focus on the rhythm and groove

~ Students are assessed as a duo and are encouraged to leverage on their strengths and uplift each other to work on arrangement and ensemble-playing skills

Formative assessment through students’ self-reflection using a checklist

When time is given for individual practice, I noticed that students were more self-directed to practise on their own. Those who were more competent also went on to play different songs. One of my students shared: ‘Music lessons help me to be a better selfdirected learner as when I am unsure of which notes to play, I will look it up myself.’

The very nature of music and music-making allows students opportunities to connect with others and to achieve goals collectively. The music classroom can be a safe and inclusive environment where students can foster bonds, appreciate and value diversity, and build community, embodying the spirit of Full SBB.

Rachel Tan Fong Kin, Senior Teacher at Compassvale Primary School, shares her journey as a pedagogical leader and how she applies Differentiated Instruction (DI) in her ukulele lessons.

Could you tell us about your musical journey so far and how that has influenced your identity as a music educator?

I grew up with Redifussion playing all day long. My father would often turn it to the Chinese channel, which played songs in different dialects and Mandarin, and featured Cantonese stories told by storyteller Lee Dai Sor. I could not understand the language, but I loved the melodies of the songs. I sang along with the melodies I liked and learned words through picking up sounds. This is how my love for singing and music came about!

Although I enjoyed singing, there were no music lessons in my primary and secondary school. I only received proper singing and theory lessons when I went to college. I joined the college choir, which gave me many opportunities to learn and perform. It was fun singing songs of different musical genres with others who are also passionate about singing. If only I could have had these experiences when I was younger, my school life would have been very different.

When I first became a music teacher, I learned to teach children hand signs, solfège, singing and recorder playing. I immensely enjoyed being a music teacher.

After I became a Music Coordinator, I better understood the importance of providing good learning experiences for students. Quality learning experiences can cater to different student interests and help them look forward to music lessons and special programmes. Thanks to the AMIS and NAC funds, I was able to organise more interesting Arts programmes for my students to gain rich learning experiences from. In addition, I would participate in the PD learning opportunities provided by STAR. When teachers make good decisions in choosing the right pedagogical tools for their students and apply them effectively, they deliver enjoyable and meaningful lessons to their students.

Quality learning experiences can cater to different student interests and help them look forward to music lessons and special programmes.

I would like my students to have the music lessons I did not get to experience when I was in primary and secondary school as a student. In addition to enjoying their lessons, I hope that all my students will be able to read simple notation and play at least one melodic instrument. Being able to read notation will enable my students to have more opportunities to perform with others and gain access to a wider variety of music. Being able to play instruments provides them with another way to express their emotions and attain emotional growth. I also hope that they enjoy singing like I do!

Please share with us about a musical experience that shaped your beliefs about teaching and learning in music education.

I volunteered to perform Dikir Barat with a group of teachers led by then Master Teacher (Music), Dr. Chua Siew Ling, for MOE HQ’s Teachers’ Day Celebrations in 2015. I had previously attended the Teaching Living Legends Professional Development (PD) Milestone Programme and thought that performing the Dikir Barat would enable me to apply what I had learnt. I noticed that the teachers in this group were already excellent performers and pedagogues, but they were still interested in broadening and deepening their knowledge; asking questions and learning from one another. This learning attitude was ‘infectious’, with the other teachers crowding around to

learn collaboratively even during the breaks.

I can be that spark.

I would like my students to be passionate about learning like these teachers were. I realised that this needed to start with me arousing my students’ interest in learning. After their interest has been sparked, it can continue to spread like a fire as I encourage students to take initiatives to learn from one another. I believe I can influence this type of learning to take place; I can be that spark.

Because peer inspiration and encouragement through collaborative learning can be a positive stimulus, I would create opportunities for this to take place in music lessons. For example, in my ukulele lessons, I would pick a few good players to perform for their peers, and they would become role models and inspire others. I would then spend more time practising with the players who need more support and help them to level up.

Are there any anecdotes you can share about how children have benefited from collaborative learning and having their learning needs met?

One of the most memorable successes I had is when I applied DI in the teaching of ukulele for Upper Primary students. Previously, when I employed a whole-class teaching approach, the class progressed according to the pace of the majority of the students. Students who would have needed more support in achieving the learning objectives, struggled to keep up with this pace. I had students giving up and choosing not to play the ukulele at all.

However, when I differentiated the teaching approach by allowing students the choice to form their own friendship groups (differentiating according to students’ learning profile), I noticed a very positive change in their behaviours. As they felt more comfortable when learning in friendship groups, these students challenged each other to improve their skills, while ensuring that everyone in the group was able to succeed.

What are your goals with regard to how students experience music in your classroom?

I love seeing the glow on their faces when they are able to sing and play the songs they like, and gain the self-confidence to share their joy and knowledge with their friends.

I would like my students to be able to learn at their own pace and enjoy the learning process. These are important to me as I love seeing the glow on their faces when they are able to sing and play the songs they like, and gain the self-confidence to share their joy and knowledge with their friends.

Tell us about some of the DI strategies you have used / are excited to try to achieve your goals.

As mentioned earlier, I have found that differentiating according to students’ learning profile using friendship groupings for classes that need more support was an effective strategy for my students. For other classes, I could group the students according to their readiness levels but allow for flexible groupings as they progress. This helped to sustain their interest and keep them motivated.

I was part of the ‘Planning Differentiated Instruction in the Music Classroom’ NLC (Accomplished) in 2020. It was a fruitful NLC, focusing on different aspects of DI. Master Teacher (Music), Mrs. Li Yen See, walked us through the entire planning of our lessons, guiding us in our thinking and planning processes. She also gave us feedback on our lessons so that we could improve them. I am now more confident in my DI lesson planning.

I would also differentiate content according to the students’ interest in ukulele lessons as this provides students with the choice of selecting from a variety of songs to play. Once students have mastered the basic chords, they are free to choose the songs they would like to learn on their own, and I will support them by teaching any additional chords that are used in the songs they have chosen. This way, the faster learners can continue to level up by learning more chords and becoming more self-directed. All students can continue to be interested and motivated when they are given choices too.

As a teacher-leader, what are some skills and attributes you would like to hone and develop in preparing for the road ahead?

As a teacher-leader, I hope I can guide teachers to enjoy their teaching and learning and encourage them to adopt a growth mindset.

I would like to attend the Orff Approach Milestone programme so that I can be equipped with more ways to engage my students. I would also like to explore more

strategies to support learners with special education needs, to better uplift and engage these students.

As rich learning can take place through meaningful sharing in a collaborative team, I believe my music peers and I can learn a lot from one another. As a teacher-leader, I hope I can guide teachers to enjoy their teaching and learning and encourage them to adopt a growth mindset.

In the earlier section, we spoke about the myths of Differentiated Instruction (DI) in context with the principles of DI. In this section, we will share strategies from literature and teachers’ experiences which you could consider using to facilitate differentiation in your music lesson.

(Bondie & Zusho, 2018, p. 49)1

Criteria Checklist enables teachers to differentiate students by readiness. All students would begin at the first/basic tier (in the Must Haves). Students of higher readiness can look ahead to how they might continue to stretch themselves and be appropriately challenged through an additional tier of complexity (in the Amazing column). The criteria checklist consists of two columns; the Must Haves identify the essentials that all students must do and Amazing articulates the possibilities for going beyond the Must Haves.

Examples to illustrate Criteria Checklist:

• Demonstrate the correct fingering for the notes: B, A & G

• Blow with a gentle tone – ‘tu’ sound

• Cover the correct holes completely

1 Bondie, R., & Zusho, A. (2018). Differentiated Instruction Made Practical: Engaging the Extremes through Classroom Routines (1st ed.). Routledge. https:// doi.org/10.4324/ 9781351248471

• Play a two-bar melody containing the notes B, A & G notes

• Play the two-bar melody in one breath

• Demonstrate the correct fingering for the chords: A Minor and F Major

• Strum with even strength across all the strings

• Press the strings well

• Switch from A Minor to F Major and back after every four strums while maintaining the pulse

• Keep the second finger from lifting when moving between the two chords

Structure Perform the chorus

Keyboard Play the chords in root position

Bass Perform the bassline using the root notes

Percussion The basic drum groove (Kick and Snare)

Perform the verse and chorus

Play the chords with appropriate inversions/voice leading

Perform the bassline with passing notes

Use of hi-hat

Appropriate drum fills

On a related note, some teachers have previously introduced tiered assignments or challenge cards in their classes For example, in the earlier article Catering to Diverse Learners in a Full-Subject Based Banding Music Class, Jeremy introduced two different levels of challenge in his Differentiated Instruction for Keyboard module

01

Students are aurally prepared and sing the song

Students learn about the background of the song

Students are introduced a specific interval that is featured in the song (descending fifth)

04

A differentiated classroom can and should include a mix of wholeclass, small-group and individual instruction. Introducing different means of achieving the same learning goal would help us better meet the needs of learners with different skills or learning styles.

At times, our lesson could be structured into several small sections or tasks. A Kodály-inspired classroom, in particular, typically has 5-8 different activities of different objectives within a single lesson. Here is an example of such a lesson on teaching the song ‘One By One’ by Kelly Tang and Aaron Lee from Stories We Sing:

05 As a class, students improvise a song based on the descending fifth, using various instruments e.g. resonator bells, boomwhackers, keyboards or virtual instruments. They would each take turns to contribute 1 bar to the class composition.

Students are to touch their shoulders for the higher note and their waist for the lower note every time the descending fifth is presented

06 Students record or (graphically) notate their contribution to the class composition

In the example above, even within whole-class instruction, students are provided with various modes with which to learn and demonstrate to their learning of the interval. First, the multiple activities build different forms of understanding for each student. Second, these can increase the likelihood of engaging different learners, enabling them more chances to discover success while feeling appropriately challenged.

(Bondie & Zusho, 2018, p. 120)

The Ideas Carousel is used to activate background knowledge through collaborative building upon ideas and brainstorming. Students learn by ‘getting up and moving’ i.e., being more physically engaged and mentally stimulated. As such, this routine encourages the process of brainstorming, building on ideas, giving feedback and consolidating thoughts in a collaborative context. Students could gain knowledge and learn in a safe environment from and with their peers.

01

Place posters of different topics or questions around the room.

02

Students select topics based on their interest and brainstorm ideas related to the topic as a group.

In their interest groups, students rotate to different topics and add Post-it notes in the following order (based on four topics):

First round

Read and add ideas

Introductory resources could be placed at each poster to help stimulate thinking.

Examples to illustrate Ideas Carousel:

Second round

Read, add new ideas and tick three important ideas

Third round

Read, add new ideas and circle the most important ideas

Fourth round

Review, discuss and present

What happens during these types of weather and what makes them special?

Examples of possible student responses

• Sunny – birds are chirping, children playing

• Raining – splash in puddles, wipers squeak

• Snow – shoveling sidewalks, sneezing

• You can only do certain things when it’s a certain weather

• They come and go, not always the same

Describe the kinds of sounds you can make using classroom percussion instruments?

Examples of possible student responses

• Triangle – long, ringing, metallic sound

• Two-tone woodblock – short resonant, tick-tock

• Shakers – soft, short, rattling, shh sound

• Resonator Bars – long, ringing, high and low notes

What do you know about the bassline?

Examples of possible student responses

• Very low

• Based on the lowest notes of a chord progression

• Provides a foundation for a full sound

• Makes the piece a bit heavier sounding

• Played by the bass guitar

What do you know about Chords?

Examples of possible student responses

• The chord progression

• Could include the 3rd and 5th notes in a chord

• Fills out the middle parts of the sound

• Played by the guitar and/or keyboard

(Tomlinson 1999, 2001)2

Learning Stations is a strategy that might be designed to cater for different interests as they could have a choice of which station to start and end with, and/or who they could learn with. It creates opportunities for movement where students must complete as many stations as possible to meet the learning objective(s) of the lesson or module.

Zones Activity (DI by Interest + Learning Profile)

1. Room is divided into 4 Zones

• Zone 1: D D D DU

• Zone 2: D D DUDU

• Zone 3: D DUDUDU

• Zone 4: D DU UD

2. Each Zone teaches a double-strumming pattern taught by a Student Mentor and videos (scan QR code)

3. Each Zone contains a Task for students to learn and practise

4. Students choose ANY Zone to start with (Interest)

5. Students choose who to go with (learning profile)

1 2 4 3

1. Students can move to next Zone after passing the current Zone’s pattern to challenge themselves (self-directed learning)

2. Before moving to a new Zone, students need to be checkedin with the teacher or student mentor (formative assessment)

3. Students can also move down to a Zone more appropriate to their level

4. Goal: To finish all 4 Zones

5. Student is appointed Student Mentor after passing Zone 4, sent to peer teach friends

1

4

2

3

If we were to merge these two strategies, we could have students first contribute ideas to each station, as in Ideas Carousel, then as part of a subsequent lesson demonstrate their understanding and thus fulfil the learning objective(s) by completing a task based on the collated ideas and information at each station.

01

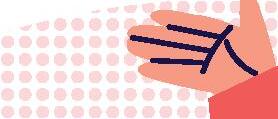

STAR Champions (Secondary) experiencing collective free music improvisation as a form of inquiry-based learning 02

Participants performing an Orff arrangement before attempting their own DAW arrangements in Music Arranging and Production 101 - Level 1

03

Participants exchanging teaching strategies during the SkillsFuture for Educators (SFEd) in O-Level Music NLC

Another semester of new musical experiences with STAR. We’ve put together a roundup of highlights that have taken place.

04

EWS 8 Members practise the Tinikling Dance to the song Bahay Kubo

05

Art and Music STs and LTs making music together during a kompang workshop

Participants from the Teaching ICT-Based Music Making (Primary) Workshop creating graphic scores from online media

07

Beginning Teachers (Sec) Arranging Covers of Popular Music during the BT (Sec) Programme

08

Beginning Teachers (Primary) Learning to Scaffold the Elements of Music Through Movement during the BT(Pri) Programme

Friends-in-Concert (FIC) Percussion Group after Rhythmic Jamming during the FIC Mentoring Session

Chau Poh Lin Susanna

Deputy Director (Music)

Susanna_Chau@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1558

Chua Siew Ling

Principal Master Teacher (Music)

Chua_Siew_Ling@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1554

Li Yen See

Master Teacher (Music)

Chan_Yen_See@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1499

Suriati Bte Suradi

Master Teacher (Music)

Suriati_Suradi@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1498

Kelly Tang

Master Teacher (Music)

Kelly_Tang@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1561

Woo Wai Mun Marianne

Academy Officer (Music)

Marianne_Woo@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1555

Liow Xiao Chun

Academy Officer (Music)

Liow_Xiao_Chun@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1494

Matthew Kam-Lung Chan

Academy Officer (Music)

Matthew_Chan@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1497

Ong Shi Ching Melissa Academy Officer (Music)

Melissa_Ong@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1495