04 18 30 37

The Odyssey of Mentoring Leading the Way Musical Conversations with STAR Music Principal/ Master Teachers

Special Featurette by Arts Education Branch Empowering the Music Teacher Fraternity for the Next Mile

04 18 30 37

The Odyssey of Mentoring Leading the Way Musical Conversations with STAR Music Principal/ Master Teachers

Special Featurette by Arts Education Branch Empowering the Music Teacher Fraternity for the Next Mile

Happy New Year. We trust that the start of the academic year brings with it great expectations and excitement. As the world slowly emerges from the shadow of the pandemic, there is much to celebrate and look forward to. The Music Unit at STAR is abuzz with excitement for the programmes we have planned for the fraternity and waits in great anticipation for our teachers’ active participation in the coming year.

The motto to Lead, Care and Inspire is a rallying call for us as educators not only to champion the cause of nurturing the young but also to advocate for the strengthening of efforts in building the professional capacity of the fraternity. This responsibility does not lie solely at the hands of the various MTTs at STAR but must be shared across the ecology of teachers and teacher-leaders from our schools. Teachers and teacherleaders on the ground are key movers of educational experiences for our students and are critical agents of change to their respective schools’ teaching and learning cultures. One of the most powerful drivers of change has come about through teachers skilfully mentoring other teachers. In this issue of STAR-Post, we want to focus our attention on the teacher-leaders amongst us who have made an impact in building others even as they are themselves being built. Such is the case with Ms Low Sok Hui, Mrs Allen Losey and Mrs Geraldine Tay, three teacher-leaders who have invested time and effort towards caring for and growing beginning teachers posted to their schools. In sharing their experiences, co-teaching and providing feedback to lessons taught and observed, these teacher-mentors provide a fertile environment for professional growth to their younger colleagues, further sustaining the music educator eco-system towards better engagement of students and enhancement of their musical experiences.

Through the years, STAR has encouraged greater teacher agency towards teacher-initiated, teacherled learning platforms. In providing PD platforms such as Critical Inquiry (CI) and Networked Learning Communities (NLC), STAR is placing teachers in the driver’s seat regarding choice and responsibility of their own professional learning, insofar as we believe that

teachers learn best when they own their professional development. STAR does not command a monopoly of pedagogical expertise. Central to our belief is that much ability resides within our fraternity and that each teacher brings to the community their unique skills, perspectives and beliefs which when tapped upon, would create a ripple of innovation across our schools. For this to happen, music teachers must believe in themselves as leaders in their field and be prepared to utilise their unique strengths and experiences to grow their peers and add value to the larger ecosystem. These teacher-initiated, teacher-led endeavours, often localised within respective schools, are important vignettes of the diverse kinds of issues confronting music teachers on a daily basis. Whether it is dealing with the challenges of inclusive classrooms or the use of technology, the process of working through these ‘problems’ and sharing the lessons learnt build professional confidence in these teacher-leaders and help, not only to level up the professional competence of the community, but also give assurance to fellow musicators that they are not alone. These are important cultural outcomes that STAR hopes to advocate.

Finally, with this issue of STAR-Post we want to celebrate our Master Teachers. Even at the apex of the teacherleadership track, learning continues for them. Much of this takes place when they get opportunities to work with the teachers on the ground. As is often the case, we tend to reap the greatest dividends for ourselves when we invest time and effort in others. The more we pour ourselves into the growth of others, the greater the growth we reap in return. It is the same for our Master Teachers. No doubt their collective sharing would make for a good read. We hope that their reflections will go some way towards inspiring our music teachers so that in time, they too could give of themselves to serve in a similar capacity…for the benefits of the fraternity and the smiles of our students. Happy Reading.

Susanna Chau Deputy Director, Music Singapore Teachers’ Academy for

The etymology of the term “mentor” has roots from 800 BCE ancient Greece. In the epic poem Odyssey by Greek poet Homer, Mέντωρ (Mentor) was the name of a character who was a trusted adviser to the main character, Odysseus. Athena, the goddess of wisdom, disguises herself as Mentor when she appears to Odysseus’s son, Telemachus, and acts as his guide, adviser, and teacher. Odyssey inspired the 1699 novel Les Aventures de Télémaque by French author François Fénelon, where Mentor is portrayed as a ‘sage counsellor’ and ‘another parent’. “Mentor” also relates to “मन्तृ (mantṛ)” in Sanskrit, meaning ‘sage’ or ‘wise

person’, and the Proto-Indo-European “monéyeti”, meaning ‘to think’.

Through these definitions, we see that the traditional role of a mentor has been closely associated with the act of guiding, advising, thinking (reflecting), and teaching, often undertaken by someone who could serve as a ‘parental’ figure and teacher to the mentee.

This article will proceed to examine what mentoring entails within the context of the Singapore education system, why it is important, and how mentoring can be effective.

• Introduced in 2006

• Focus on school-wide mentoring and induction

• Introduced in 2011

• Instructional Mentors focused on teaching and learning

In Singapore, the Structured Mentoring Programme (SMP) was first formally introduced to schools in 2006. It aimed to unify standards of induction and mentoring practices across schools.

In 2011, the Skilful Teaching and Enhanced Mentoring (STEM) programme was launched. Based on the Skilful Teacher Framework (Saphier et al., 1997)1, it aimed to improve teaching and learning among beginning

• IMP introduced in 2015

• Aimed to expand number of instructional Mentors trained annually

• STEM continued

• Completely replaced STEM from 2017 with the launch of STP

teachers (BTs) while developing skilful instructional mentors.

In 2015, STEM expanded to include the Instructional Mentoring Programme (IMP), with the aim of increasing the number of instructional mentors.

Finally, in 2017, with the introduction of the Singapore Teaching Practice, IMP completely replaced STEM.

Let us look at its definitions and theoretical underpinnings to find out.

Definitions

Lipton, Wellman, and Humbard (2003)2 describe it as a developmental and mutually beneficial partnership whereby a mentor guides and develops a mentee to achieve quality teaching and learning, while Feiman-Nemser (2012, p. 241)3 describes it as “a role, a relationship and a process… mentors take on an educational role, form a pedagogical relationship [and] engage in an educational activity”.

The terms “developmental” in Lipton et al.’s definition and “process” in Feiman-Nemser’s suggest that mentoring is guided by long-term goals and is not evaluative. Mentoring must be localised in mentees’ needs, which would enable them to achieve their professional goals.

There are three inferences we can make based on these definitions: 2 1 3

The phrase “mutually beneficial” in Lipton et al.’s definition suggests that mentoring promotes mutual growth, and that the mentoring process benefits and transforms both the mentor and the mentee.

Finally, the terms “partnership” in FeimanNemser’s definition and “relationship” in Lipton et al.’s suggest that relationship-building and the dynamics of the mentor-mentee relationship are critical to the success of mentoring.

3

1

4 Schon, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Temple Smith.

5 Hartman, H. (2009). A guide to reflective practice for new and experienced teachers McGraw-Hill.

6 Zeichner, K. M. (2005). A research agenda for teacher education. In CochranSmith, M., & Zeichner, K. M. (Eds.), Studying teacher education: Report of the AREA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 645–735). Lawrence Erlbaum.

7 Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Instructional Mentoring has two theoretical underpinnings:

^ is a process of introspection that focuses on “thinking about doing” before, during, and after a lesson (Schon, 1983)4

^ Mentors guide mentees in reflective practice by analysing the strengths and weaknesses of their lessons, allowing teachers to gain insights into the nature and purpose of teaching practices to improve future performance (Hartman, 20095; Zeichner, 20056).

(Ryan & Deci, 2000)7

^ When people’s three basic psychological needs of competence, relatedness, and autonomy are met, they will be motivated to initiate new behaviours and sustain them over time.

^ Localising mentoring to meet mentee’s needs would provide mentees with the optimal conditions for them to grow and strive for professional excellence.

T hus, based on what we have learned from looking at the definitions and theoretical underpinnings, we can conclude that instructional mentoring aims to help mentees develop competence, relatedness, and autonomy for lifelong learning towards pedagogical excellence. This could be achieved by localising mentoring to meet mentees’ needs, and building a trusting relationship that facilitates reflective thinking and mutual growth.

It is based on this understanding that the rest of the article will unfold.

In the next sections, Mr Lim Ji Heng, Mr Valentin Welzl, Mrs Allen Losey, and Mrs Geraldine Tay share their thoughts and experiences of their mentoring odysseys.

Mr Lim Ji Heng (BT) was mentored by Ms Low Sok Hui (Senior Teacher, Art) at Eunoia Junior College.

Mr Welzl Valentin (BT) is mentored by Mrs Allen Losey (Senior Teacher) at Fengshan Primary School.

Mrs Geraldine Tay (Senior Teacher) mentored BTs who are teaching other subjects at Holy Innocents’ High School.

Note:

The discussions in this article are limited to the personnel mentioned above. Teachers could have other mentors or mentees who were not discussed in this article.

As teachers, our goal for professional excellence invariably leads back to how we can better serve our students, which is after all where the heart of education lies. Mentoring is important, as quality mentoring enhances the quality of teaching, which can have a significant impact on student learning (Timperley et al., 2007)8.

In return, students’ feedback provides useful information that mentors could guide teachers to reflect on in order to improve their teaching.

The cyclical benefits of quality mentoring can be illustrated through the Quality of Feedback loop below.

Let’s hear about this from mentees’ perspectives:

The mentoring process has aided me in my classroom teaching and pedagogy. I can execute lessons with more confidence, and I observe that my students enjoy the music lessons and are able to pick up the necessary skills as per the learning objectives. The students are eager for music lessons and this encourages me to do my best and to be confident of my abilities. It is a positive cyclic loop that benefits all involved.

The feedback I glean from co-teaching with my mentor feeds dynamically into the lesson flow, and transforms into ‘meta-feedback’ through students’ responses.

Mentoring can occur between mentors and mentees teaching different subjects, as pedagogical skills can be shared across subjects. This would allow for deeper content and pedagogical understandings, and

would also encourage curiosity, openness, and adaptive thinking to creatively transfer knowledge across domains (Billett, 20139; De Corte, 201210).

The interdisciplinary exchange of knowledge between myself and my mentor opened my eyes to the broader artistic movements surrounding and influencing certain musical works.

Mr Lim Ji Heng

Mentoring is one of the key roles that a teacher-leader takes on; he/she needs to develop as a pedagogical leader, collaborator, and mentor.

9 Billett, S. (2013). Recasting transfer as a socio-personal process of adaptable learning. Educational Research Review, 8, 5–13.

10 De Corte, E. (2012). Constructive, selfregulated, situated, and collaborative learning: An approach for the acquisition of adaptive competence. Journal of Education, 192(2-3), 33–47.

While mentors are typically recognised for their experience and pedagogical competence in the classroom, good classroom teachers need to consciously develop their skills to be effective mentors as well.

As mentioned above, the end goal of instructional mentoring is to meet mentee’s needs and encourage lifelong learning. The effectiveness of mentoring is a complex issue with many tacit factors. However, it can largely be determined by the interplay between the following three factors:

unique developmental needs

in which the interaction between the mentor’s dispositions and the mentee’s openness plays an important role

Mentors’ competencies in the classroom, their dispositions, as well as the developmental focus of their mentorship will help enable them to form trusting relationships with their mentees. This is reflected in the panellists’ comments:

The relationship has to be founded on mutual trust. I need to first trust that my mentors genuinely understand my growth needs and aspirations, to even seek and heed their advice with assurance. I must trust their experience and wisdom in looking out for meaningful and manageable opportunities for my professional development.

I think it is crucial for me to be authentic and real, not judgmental, and encourage my mentee to do his best. I would share my own goals/dreams and challenges as well, and how I overcome them. This would allow my mentee to know that I also have my fair share of challenging days but it is alright as I would work to find solutions around them.

Of course, relationships are a two-way street, and the extent to which this relationship-building is successful is also dependent on a mentee’s openness to learn and willingness to be mentored:

I would occasionally share concerns about my lessons to seek advice from my mentor. The sharing of concerns is made much easier upon understanding and trusting that my mentor is there to affirm and provide suggestions.

There were instances where the sharing of experiences [between mentor and mentee] helped to clarify certain issues and helped the mentee to understand and manage processes better.

Thus, building a trusting relationship between mentors and mentees involves a co-dependent process that both parties define and navigate together. Mentors can also encourage mentees to be more open as they develop a stronger mentor-mentee relationship:

Building a positive relationship from the start is important. Rather than plunging straight into the lesson planning and observations, I wanted to get to know my mentee on a more personal level. We talked about personal things - family, friends and interests as well as how he or she was coping in school. I find that through these candid yet heartfelt sharing of ideas and experiences, we can build the trust that is paramount in the mentoring journey.

My mentor trusts me wholeheartedly from the getgo. As such, on a day-to-day basis I feel more at ease knowing that there is someone to consult when in doubt. I can comfortably approach her regarding any query, knowing without any doubt that her intentions are to advise and assist in my growth.

An open and trusting mentee enables mentors to better understand how mentees think, and in turn better meet their needs through long-term, development-focused reflections:

Building trust is very important in every relationship, not only in mentor-mentee relationships. When there is trust, the suggested areas for improvement come from a place of care.

Without trust, a mentor-mentee relationship is but a transactional duty. I believe my mentors trust me too; they give me space to explore different approaches and work areas, make mistakes, and then learn from my mistakes.

Mentees’ needs are met when mentors are able to account for their learning preferences and learning needs, and respond dynamically to changes in the three stages of a mentoring relationship:

Mentees display development-seeking behaviours (Higgins, Chandler, & Kram, 2007)11. Mentors can use this stage to assess mentees’ needs (Mullens & Schunk, 2012)12 and encourage them to reflect on their mental models of teaching (Rajuan, Douwe, & Verloop, 2007)13

This is reflected in the panellists’ comments:

Through conversations with my mentee, I get to know more about his or her concerns in the classroom and these can be a starting point for areas to work on.

Open classrooms with my mentor have helped further cement my understanding of music education. My mentor also spearheads various programmes such as assembly programmes or professional learning circles and provides me the opportunity to be involved while observing how they are done.

Mr Lim Ji Heng

I did several lesson exchanges (i.e. informal lesson observations) with my mentor. I gleaned valuable insights just from observing how she facilitated student peer critique and also checked for students’ understanding at critical junctures during her art lessons.

Everyone needs to start somewhere, and allowing my mentee to copy first then find his own way was a good way to start the ball rolling. We did this through co-teaching some classes at the beginning. My mentor is welcome at any time to come in to watch my lessons, and we can have an informal chit chat after that.

Mrs Allen Losey

11 Higgins, M. C., Chandler, D. E., & Kram, K. E. (2007). Developmental initiation and developmental networks. In B. R. Ragins, & K. E. Kram (Eds.), The handbook of mentoring at work: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 349-372). SAGE.

12 Mullens, C. A., & Schunk, D. H. (2012). Operationalizing phases of mentoring relationships. In S. J. Fletcher, & C. A. Mullens (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of mentoring and coaching in education, 89–104. SAGE.

13 Rajuan, M., Beijaard, D., & Verloop, N. (2007). The role of the cooperating teacher: Bridging the gap between the expectations of cooperating teachers and student teachers. Mentoring & Tutoring, 15(3), 223–242.

14 Zachary, L. (2011). The mentors’ guide: Facilitating effective learning relationships. Jossey-Bass.

15 Mullens, C. A., & Schunk, D. H. (2012). Operationalizing phases of mentoring relationships. In S. J. Fletcher, & C. A. Mullens (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of mentoring and coaching in education, 89–104. SAGE.

16 Schunk, D. H. (1989). Social cognitive theory and self-regulated learning. In B. J. Zimmerman, & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Selfregulated learning and academic achievement (pp. 83–110). Springer.

Mentors and mentees “negotiate” an agreement about goals and structure for the relationship and its content (Zachary, 2011)14. Mentors enable mentees by providing advice (Mullens & Schunk, 2012)15, building upon and refining learning goals, and facilitating the mentee’s sense of self-efficacy for attaining them (Schunk, 1989)16.

Let’s hear from our panellists about this:

Mr Welzl Valentin

My mentor provides me room to experiment and make mistakes. She would occasionally remind me of the support system we have built, that she is always there to be a listening ear, and to provide more opportunities for learning in various ways, such as one-to-one discussions on classroom teaching pedagogies, or invitations to open classrooms.

There should be no intimidation at any point and the end goal is always for growth

Being open and understanding that people develop on their own timelines, I have to be patient and give time for my mentee to grow. Giving bite-sized areas to work and improve upon will make the process more enjoyable and celebrating small successes to motivate the mentee. Encouraging my mentee to be reflective would help pave the way for his own practice and development.

Mentees might feel apprehensive as they “graduate” from the instructional mentoring programme, while also experiencing positive feelings of appreciation, loyalty, and identification. Mentors could respond to this by evaluating the learning that has occurred, expressing appreciation, and celebrating mentees’ achievement (Mullens & Schunk, 2012).

What better way to motivate and encourage another person than to praise them for a job well done. I am very proud to see my mentee grow and succeed and feel confident about his own teaching.

Similar to how relationships are a two-way street, the mentoring process itself also promotes mutual growth for both mentors and mentees. When mentoring is effective, there will be many benefits for both mentors and mentees.

Mrs Geraldine Tay

’In learning you will teach, and in teaching you will learn’musician Phil Collins, in the song Son of Man. I will always remind myself of this and also reiterate to my mentee that we learn from each other through the process. It is a mutually benefitting partnership that will develop quality teaching and learning as well as socio-emotional aspects in my role as an educator and mentor.

Adapted from the Guide to Effective Professional Development: Instructional Mentoring (Ministry of Education, 2019).

The table below features a summary of some of the growth that mentors and mentees may experience through the mentoring process.

Mentee

Self-Confidence

Job satisfaction

Career advancement

Socialisation

Psychosocial support

Increased professional competencies

Mentor

Self-Confidence

Personal satisfaction and self- actualization

Career enhancement / rejuvenation

Positive network building, interpersonal skills, collegiality

Self-reflection

Insights to how younger colleagues think, which could lead to the acquisition of new skills and/or fresh perspectives

Our teachers share how they have grown from the mentoring process:

Having a mentor has reconstructed my view of music education. My mentor provided me with a perspective on music education, and through that, encouraged me to find mine. Now, I find much more enjoyment teaching in the music classroom and I notice that such joy is spread to the pupils. This makes the entire classroom environment a more fun and conducive space for learning music.

I feel that I would be missing the forest for the trees if I fail to recognise that the mentoring process refines my mindset. Working alongside my mentors has shaped and sharpened (and at times, shaken up) my convictions surrounding what it means to be a genuine and thoughtful educator.

Mr Lim Ji Heng

Mentoring others has helped me to develop a deeper understanding of my own pedagogies and approaches Many of us have our own biases and blind spots, but in helping others, I was able to see things in different perspectives. I also gained new learning from my mentees; I gained new insights and learned about new tools, which are helpful in my teaching as well.

Mr Lim Ji Heng

My mentors have run long distances on the teaching racecourse with their fair share of disappointments, but they are still proactively learning, persevering, upgrading, exploring, and educating with passion. I try to catch these ideals from them.

My mantra as a mentor is to always try to put my mentees on my shoulders in hope that they can see and go further than I can. I look forward to that day.

In Homer’s Odyssey, Athena tells her father Zeus of her plans to help Telemachus, “Then I’ll go to Ithaca, to spur his (Odysseus’s) son on more, and I’ll put the courage in his heart…”.

Like Athena, mentors, through their acts of guiding, advising, thinking, and teaching, imbue courage in the

hearts of their mentees. This courage and the wisdom they impart would strengthen mentees and stay with them as they set sail on their own odysseys as music teachers, and like proud parental figures, mentors themselves can be enriched and fulfilled as teacher leaders in the process.

1

The landscape of education is ever-changing, and the breadth of pedagogical knowledge teachers need to learn is increasing exponentially. Due to this constant movement, teachers must be proactive in charting their professional learning to remain relevant. The journey of deepening pedagogical knowledge is an ongoing and self-directed process.

“…teachers never finish learning. They must constantly enlarge their repertoire, stretch

their comfort zones, and develop their ability to match students to reach more students with appropriate instruction.” (Saphier et. Al, 2008)1

In this article, we delve into the ways teachers can initiate their own professional learning and delve into the thoughts of teachers who continuously seek to deepen their pedagogical content knowledge through varied professional learning opportunities.

There are many platforms for teachers to initiate professional learning. STAR had its inaugural run of ten-minute Pop-Up 10 presentations by teachers last year, Teacher Work Attachments (TWAs) are becoming more and more popular and there are always opportunities for Professional Learning Communities at the school level.

For this article, we will take a look at the following three platforms: Critical Inquiry,

Networked Learning Community and TeacherLed Workshop. These are platforms which put teachers in the driver’s seat in terms of what areas of the self-development they want to explore and what knowledge they wish to share with the fraternity. To begin their journey, teachers submit a proposal for approval of their project and for MOE to allocate possible support.

The table below provides a brief description of each platform as well as a link to their respective informational pages.

Critical Inquiry is a reflective process involving systematic analytical approaches to refine classroom practices and enhance student learning. During the critical inquiry process, teachers identify an area of inquiry, examine strategies, gather evidence, and analyse data to improve their classroom teaching and learning.

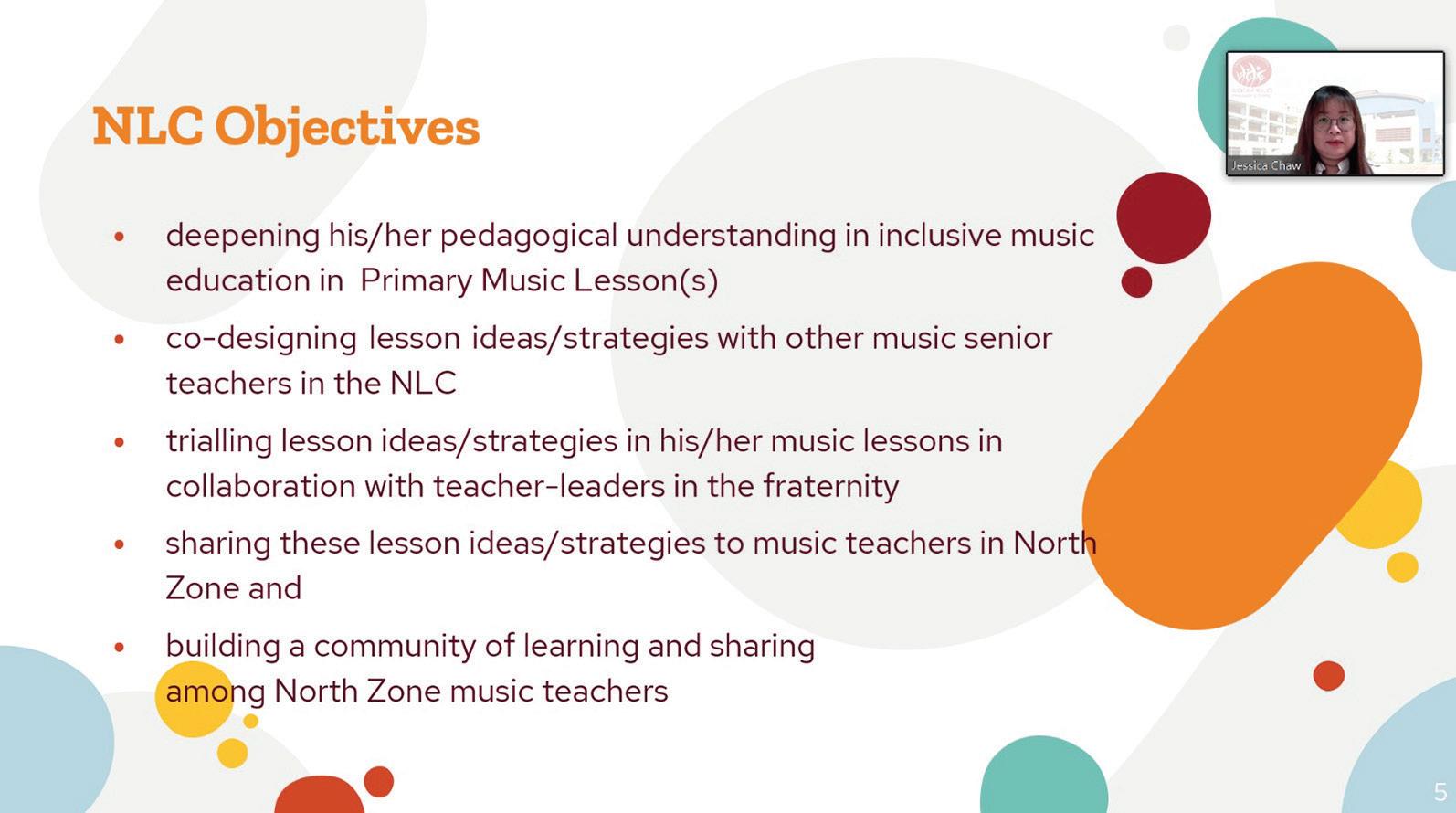

Networked Learning Communities are teams of teachers from different schools working and learning collaboratively to examine and reflect on their practice. They learn from one another, with one another and on behalf of others. In the process, teachers co-create and share new knowledge and practices to improve student outcomes.

Teacher-Led Workshops are conducted by teachers for teachers. Guided by the mission of the Academy of Singapore Teachers (AST) to develop a teacher-led culture of professional excellence, AST has built on the work of Teachers’ Network to create opportunities for teachers to lead and inspire through the sharing of good practices. Through this platform, teachers will engage in professional exchange of pedagogical content knowledge, leading to enhanced pedagogical practice.

In short, CI help us to be a more reflective practitioner through an inquiry process in the classroom, NLCs enable us to learn and cocreate collaboratively across schools and TLWs provides opportunities to share good practices

with the fraternity. By challenging ourselves to initiate these opportunities, we become more self-directed in our professional learning and experience.

To help us understand the inspirations, challenges and learning from their self-initiated professional learning, four teachers share their experiences of embarking on their self-initiated learning journeys. Here is a quick look at the kind of projects they worked on:

Platform

Networked Learning Community

Project Title

Inclusive Education in Music Classroom

Synopsis

A collaborative project and presentation that trialled strategies that support a culture of inclusivity in Music Classrooms with a focus on special needs. This included elements of Universal Design for Learning and Differentiated Instruction.

Platform

Networked Learning Community

Project Title

Music Production (Mixing)

Synopsis

A two-day programme focussing on audio post-production which included the sharing of good practices in mastering and the use of software plugins. The programme included a visit to Republic Polytechnic and working with Artist-Mentor Mr Khew Sin Sun.

Teacher-Led Workshop

Collaborative Learning Experience Using Music Technology

A workshop on how collaborative learning strategies and usage of music technology platforms could better engage students in learning musical concepts, instead of using traditional music instruments.

Platform Critical Inquiry

Project Title

Authentic Learning Through Real-World Scenarios in Composition Assignments

Synopsis

Narrative-based research on how students experience an authentic learning composition assignment using real-world examples. The teacher questions whether students are more likely to be interested in what they are learning if what they are learning mirrors real-life contexts and addresses topics that are relevant and applicable to their lives outside of school.

Each teacher’s inspiration to take professional learning into their own hands came from different starting points; a desire to build upon school-based projects, an opportunity to work

with like-minded colleagues or an opportunity to share and inspire others. The essence of their inspiration is reflected with how Michael Cartwright summarised his inspiration:

I’m always looking for new opportunities to learn and grow.

“I’m always looking for new opportunities to learn and grow. I see Critical Inquiry as a means for the teacher to grow on many different levels. Personally, I benefit from learning how to go about conducting research and the kind

of mindset that is needed. Professionally, it’s a chance to reflect on and adapt my teaching practice and also gather evidence and feedback on how my approach is going.”

When leading and facilitating their NLC discussions, Jessica engaged the team members in establishing clear learning goals for their professional learning and mapping out how the team might achieve them. Subsequently, they explored how to grow a culture of inclusivity by following the Action Research process and undergirded their pedagogical strategies based on Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

Throughout the process, Jessica listened actively and objectively, and provided a safe environment for members to share their positive experiences and challenges. For her, these discussions were a highlight of the journey as teachers shared candidly and freely about their successes and areas for growth. As critical friends within the NLC, they provided suggestions for feedback for each other’s teaching strategies.

As critical friends within the NLC, they provided suggestions for feedback for each other’s teaching strategies.

After brainstorming some of the possible areas of focus, Jasmin and her NLC team members engaged in a discussion with an invited ‘knowledgeable other’, Mr Khew Sin Sun, to streamline the focus so that the end goals were manageable and relatable.

As a Senior Lecturer at Republic Polytechnic, Mr Khew had experience teaching tertiary students so he was able to advise on the skills

that secondary school students should acquire to have a solid foundation in music post-Production.

During their trip to Republic Polytechnic in 2021, Mr Khew not only demonstrated how to use different pieces of equipment in the audio production process, but also provided Jasmin and her team the opportunity to observe how recording studios, foley studios and media rooms are set up. The team was inspired to incorporate some of these ideas in their own curriculum to support students who had interest in pursuing a related career in audio production.

Jasmin shared how her learning had a direct impact on her students during COVID:

“Personally, the NLC was useful in giving me confidence to put my students’ voices together. Since that was the SYF year affected by COVID, the choir CCA had to submit an audio recording. One of the choir’s section leaders teared after listening to the completed recording because she could finally hear everyone’s voices together after not being able to sing as a group for two years. That was a touching moment for us both.”

Dawn was mentored by a PD Friend, who was one of the Master Teachers (MTT) from Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR). Through their conversations, she learnt that an adult learner’s experience is based on the knowledge they have brought with them through their life experiences.

During both the planning and presentation stages, she challenged herself (i) to provide pedagogically grounded and relevant content

(ii) to be able to leverage on technology well, and (iii) incorporate collaborative and interactive activities to engage participants during the workshop.

Upon completion of the workshop, she further reflected on new ideas that came about during the entire process and considered how she might incorporate these ideas in her lessons and to improve upon the existing lessons.

An adult learner’s experience is based on the knowledge they have brought with them through their life experiences.

Michael also had the opportunity to work with an MTT from STAR. At the beginning of his Critical Inquiry project, he had a conversation with the MTT regarding the various research methods. Being the only music teacher in his school, Michael found the experience inviting because it was his chance to bounce ideas with others while also learning a new approach to reflect critically on his teaching.

After learning about the various research methods, he chose the narrative approach as he liked the idea of developing a narrative between the project, the students, and the teacher. Over a term, he journaled the ‘stories’ that developed as the research progressed. He enjoyed the process greatly because

there would always be a ‘twist’ or something unexpected that pops up. These moments excited and motivated him and kept him curious throughout the project.

Prior to trialling this new approach, he felt some trepidation relinquishing certain parameters of the task. As a result of his willingness to step into the unknown, he observed students going above and beyond when creating posters for their authentic tasks. They also displayed greater musical connection between their composition and the real-world scenario by using more detailed descriptions with musical concepts to illustrate the type of composition they were aiming to create.

What

and seconds)

How many sections is your composition going to have? How long will each section be?

Any specific requirements according to the job description that you need to put in your composition?

How are you going to create your melody?

E.g.: Tracks/smart instruments/ live loops.

How are you going to create your chord/harmony part(s)?

E.g.: Tracks/smart instruments/ live loops.

How are you going to create a bass part?

E.g.: Tracks/smart instruments/ live loops.

How are you going to create drum/rhythm parts?

E.g.: Tracks/smart instruments/ live loops.

Are you going to add in sound effects? Yes/no? What effects? Why/Why not?

loops Yes, water effects. To create experiences Term 3 GarageBand Composition assignment.

Music to create mood that matches the view and the spirit of cruise ships. Start music when elevator closes.

Smart instruments and live loops

Smart instruments, tracks and live loops

Smart instruments

For each of these projects, there were also obstacles to overcome in terms of planning. We have summarised some of these challenges in the table below along with the suggested resolution each teacher found when dealing with the challenges.

Having difficulty selecting strategies and deciding upon what to share during the presentation.

Difficulty trying to standardise the research method when capturing classroom observations due to the unique set up of each classroom and students’ behaviour.

Difficulty trying to accommodate a variety of abilities and experiences within the team on the selected topic.

Unforeseen logistical constraints disrupted plans.

Use of a discussion board such as Padlet, to facilitate an open discussion and for members to vote on various ideas after listening to everyone’s point of view.

Entertain the possibility of mixing methods and exercising flexibility where possible to be inclusive and respectful of all participants.

Invite an expert to share an unbiased perspective on what has already been done and where common ground could be found for the benefit of all.

Leverage technology and plan for contingencies where possible.

Through their NLC or CI or TLW, the teachers reflected on what they enjoyed most about the experience and how it impacted them as a learner.

By leading an NLC, I became a mentor to a group of teachers and teacherleaders to support their professional learning. It has given me the opportunity to share my knowledge and experiences in Inclusive Classrooms and be a sounding board for the members’ thoughts. This experience allowed me to connect with the team and help them grow their skills, make better decisions, and gain new perspectives in their work. From this mentorship, I also learnt from my members and expanded my repertoire of innovative, creative, and appropriate strategies to create inclusive music classrooms.

The NLC gave me opportunities to practise being a change leader and a network leader. We had rich discussions with the participants and our mentor about current music practices that are aided by technology. With this knowledge, I am more prepared to help my students respond to the global influences on music, where the production process of music is becoming more accessible to everyone. This NLC also provided us with the chance to network with others and build sustained relationships between secondary and tertiary schools. This is especially important in a subject like ours where discussions are limited as there are usually only one or two teachers within a school.

It gave me the impetus to take a module that was already quite successful and see what I could do to make the module even more student-centric and authentic. Additionally, having the courage to take risks and seeing them payoff is very affirming and drives my desire to continue learning as a teacher and musician.

By presenting a TLW, my learning capacity as a teacher leader expanded and I feel more confident to share my knowledge and skills with others. I also offered support with critical but constructive feedback. I encouraged teachers to think deeper in both their teaching and learning, engaging teachers in professional exchange of pedagogical content knowledge, leading to enhanced pedagogical practices among the teachers.

In conclusion, here are some suggestions from the teachers on how to initiate and lead a professional learning experience:

1. Have an open mind and provide a safe environment for open discussion.

2. Choose a topic or area that is close to the hearts of teachers on the ground.

3. Establish your rationale and set clear objectives.

4. Find like-minded colleagues and have fun learning together.

5. Do not hesitate to look for guidance and advice from colleagues.

6. Consider a research approach that best fits your topic and your working style.

7. Ensure the experience is interactive.

8. Engender a lifelong learning and reflecting attitude.

In the pursuit of professional excellence, we sometimes must step outside our comfort zone to engage in meaningful discussions and look beyond the classroom in order to understand others’ perspectives and find the right approach in our teaching.

The following is a short exchange between the author and Michael Cartwright, prior to sharing his responses to the interview questions. It encapsulates the essence of what the journey of deepening pedagogical knowledge is about: an ongoing process of self-directed learning.

I’m finishing up my new CINLC presentation now, then I’ll switch over to finishing up your questions.

Thank you! Wow! Another CI project!

Got to keep trying till I get it right!

In a 2021 study on growing music teacher identity, Chua and Welch (2021)2 states that “(teacher) identity is open to influences, and environmental contexts continue to change, professional development work is therefore an enduring one.”

As mentioned previously, the landscape of education is ever-changing, and the breadth of pedagogical knowledge teachers must be familiar is increasing. This ongoing self-directed learning attribute is critical to the identity and mission of the teacher.

2 Chua, S. L., & Welch, G. F. (2021). A lifelong perspective for growing music teacher identity. Research Studies in Music Education, 43(3), 341. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/ 1321103X19875080

STAR’s Music Master Teachers Mrs Li Yen See, Mdm Suriati Suradi, Dr Kelly Tang and Principal Master Teacher Dr Tan-Chua Siew Ling share their journey as teacher-leaders, beliefs on music education and aspirations for the music teaching fraternity.

What inspired you to take on the role of a Master Teacher? What is your vision for Master Teachers?

T he big question is, what does good music teaching look like? In our role as Master Teachers, we could discover that for ourselves and work with other music teachers to help discover that big idea together.

and work with other music teachers to help discover that big idea together. We want to grow ourselves and others to be who we want to become.

I see myself as a music education advocate – I feel strongly about this and it gives me an edge to approach teachers to bring forth our subject to a greater height.

We dived deep into teaching, understanding pedagogies and equipping ourselves with the relevant skills. What inspired me to do so was the growth that I observed among the teachers. They were willing to apply their new learning and then, shared with us on how it worked for the children. This gave me hope that music education is something worth delving in as I could really help teachers in that area. I see myself as a music education advocate – I feel strongly about this and it gives me an edge to approach teachers to bring forth our subject to a greater height. I appreciate the fact that we are in the position where we can help teachers; to

When we were invited to be Master Teachers, an important question I asked myself was, how do we grow into our role as a Master Teacher so that we can influence and impact the music fraternity? As a teacherleader, being able to provide pedagogical leadership and mentorship to enhance the capacity of the teaching fraternity is essential. I believe that pedagogical leadership is about how I can be a and pedagogical influencer resources for the curriculum that are instructional and strategic. Being a pedagogical influencer has to do with us being connectors, mavens and advocates. As connectors, we are the initiators of the connections within the fraternity as we work with teacher-leaders on the ground whom in turn work with the rest of the fraternity. We are mavens as we need to have the expert knowledge and experience to help our peers connect with new information. We are also advocates who need to have good facilitation and negotiating skills. These are the roles which I see myself undertaking.

My vision of an MTT is threefold; firstly, to lead music teachers by exemplifying the four values of creativity, collaboration, curiosity and cultural perspective. Secondly, to provide practical strengths. Thirdly, to listen and to understand the unique situations of each teacher and to try to support and help. I am always aware of these roles, and I try my best to embody them in my life and my interactions with teachers. No doubt they have made me a better musician, educator and person.

Your work as Master Teachers involves mentoring teachers on the ground. Could you share your experiences and takeaways as mentors?

This is something that resonates strongly with me – that we need to mentor teachers in a way that they can perceive themselves in a ‘better state’, rather than what ‘better state’ for them. We may have some visions and ideas on what good music teaching is, but there are just so many visions of what good music teaching is and what a studentcentric music lesson can look like. It is not about us telling and prescribing certain methodologies or music teaching approaches, but how the teachers can approach it such that they believe in the values that are embedded within these approaches and can grow and shine with that pedagogy.

When we collaborate with teachers, mutually beneficial relationships are formed. An example is when we had collaborated with teachers in 2012-2013 to develop student centric music lessons and thereafter in developing the four pedagogical leverages. Throughout these years, we worked with the teachers on their lesson ideas, video-recorded their lessons and had post-discussions. Our conversations with them helped us to understand if certain strategies were feasible and how we might extend them. The mentoring process is not one-way but a developmentally mutual and beneficial relationship as we also learn from them.

We developed relationships with the teachers through close connection and intense rapport. We knew almost everyone back in the day because we visited schools so often to meet them and to offer help whenever possible! Such relationships that we have fostered allowed us to know their needs better.

A big part of that relationship building is also trust. I appreciate that the teachers place their trust in us, and we trust them to collaborate. As a mentor, I believe in having the four ‘A’s – Attitude (willingness to share), being Available, being Analytical and being an Active listener. Having a good attitude is essential as we are not the know-all and end-all. Being available is to keep an open door in terms of mentoring, to collaborate, and take an interest to grow alongside with them. We can be analytical by being not just strategists and factfinders, but also to help teachers contextualise the theories and pedagogies. As an active listener, we ask questions that invite our mentees to reflect before we provide guidance and feedback. We nurture their strengths and address their misconceptions so that our mentees can grow.

We not only share the breadth of the content but also give them the confidence so that they can make informed choices and decide what is best for themselves.

We also encourage them to not be afraid to fail the first time, so that they can develop into being reflective practitioners.

As Master Teachers, you are also involved in developing the professional learning of teachers. Could you share your thoughts on that?

I am grateful for having a team to work with – we bounce ideas, tear them apart, deconstruct and reconstruct them. We also collaborate with experts in other subjects, understand their perspectives and explore how we make them relevant to music. To me, developing PD involves a collective understanding – it is about planning, trying, dissecting, implementing and reflecting on different pedagogical ideas/perspectives.

We deepen our pedagogical understandings from different experts in other universities, and then collaborate with the teachers on developing these ideas as they are our crucial partners. That is when we switch our roles from being mentors to collaborators with the teachers. We typically work with a small group of teachers to understand and hear their perspectives and ideas, make tweaks and changes and then share the pedagogical ideas and perspectives with the fraternity.

Your work as Master Teachers involves mentoring teachers on the ground. Could you

When one of the teacher-leaders whom I worked with for a Differentiated Instruction (DI) resource said, ‘It works! I should have used this earlier! I must continue to use this and plan for DI for different modules!’, that was very inspiring for me. It showed that he absolutely believes in it. Seeing how I sparked a belief or passion in someone such that they are so inspired and want to extend their learning is the greatest gift for me. Similarly, it was heartening to see one of the teachers whom I worked with for Social-emotional Learning (SEL) in music further her development exploring that area further through a Critical Inquiry (CI) project. I see myself as the spark that ignites the flame for the teachers. It is such a great gift to see how their flame continues to grow and be bright.

My time in STAR is truly the peak of my career. Everything that came before was meant to prepare me for this moment. I learnt deeply about many pedagogies – for example, Kodaly, Orff, and non-formal music approaches – and tried to synthesise and apply them in my own workshops. I have learnt so much from the wonderful STAR team and fellow teachers. What is inspiring for me is knowing that every teacher and student has their own story and music to share, and the role of a Master Teacher is to bring that out.

The greatest learning for me would be understanding the diversity of people and the experiences that they bring. Sometimes when I share a certain approach, others may not understand where I am coming from as their background and experiences are so different from ours. While I believe that it is important that teachers should adapt and rationalize teaching approaches, I now also understand that sometimes, teachers and mentees see the possibilities from just simply by copying an action. This is similar to how the Singapore Teaching Practice (STP) comes with sets of teaching actions that teachers can activate and try out in the classroom which comes with a degree of copying and emulating, and a desire to achieve a similar outcome. That is the beginning of change that can blossom into something greater. As we work with others who have diverse experiences, I learned that every effort, no matter how small, is an effort that we can support. The openness to try and to evaluate the effort themselves helps shape their identities in the long run as teachers.

Could you share your thoughts on being a good music teacher/ teacher-leader?

Parker J. Palmer says, “we teach who we are”, so being a good teacher is about being a better person. Being a teacher-leader is about growing yourself and others, thus even more imperative to be better versions of ourselves. This experience is very humbling as I realised the need to be more mindful when I speak to and interact with people in terms of my language and actions. I have to reflect on them daily so that I can become a better person and teacher. Alongside developing 21st Century Competencies (21CC) in students, we also nurture our dispositions and reflect on who we are as educators and as teacher-leaders.

music in each person. As a teacher-leader and music educator, it makes me come to terms with my own mistakes, reflect on them and see how I can use them to provoke and influence others.

Music teachers contribute to a society that allows music and brings out the personal music in each person.

Please share your aspirations for the teaching fraternity and advice to aspiring teacher-leaders.

I hope that there would be even more sharing amongst the fraternity. When you share, you grow yourself and others. There is learning for all; ideas can grow –

Like how Bach grew his ideas by stealing ideas from everyone!

requires great self-awareness. An educator has an immense impact and influence on

worked for you. Then collaborate with team members to see how you can improve – when people ask questions, your understanding deepens as you deconstruct and reconstruct ideas and synthesise responses to the questions. Start in your own classroom and school

that difference.

Every teacher must have the drive, the passion and the heart to want to make

The 2023 Music Syllabus was developed over the course of two years with contributions from teachers, and colleagues from the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts and National Institute of Education. We are happy to have shared it with all primary and secondary schools early last year.

The 2023 Music Syllabus builds on the strengths of past music syllabuses, and the increasing level of competency and professionalism across the music teacher fraternity. It stems from the belief that with the world becoming increasingly complex and uncertain, the role of music and music teachers in helping our students thrive in the future would be increasingly important. The syllabus seeks to feed every music teacher’s sense of purpose to equip students with the 21st Century Competencies and develop them holistically through ways that are meaningful to the subject.

The syllabus seeks to feed every music teacher’s sense of purpose to equip students with the 21st Century Competencies and develop them holistically through ways that are meaningful to the subject.

To empower teachers in realising and contributing to this next mile of Music Teaching and Learning envisioned by the syllabus, the Arts Education Branch (AEB) highlighted the following key shifts intended by the syllabus during the syllabus implementation workshops that started since May 2022:

Implementation Workshop Part 1 (Secondary Level) conducted in May 2022

Implementation Workshop Part 2 (Primary Level) conducted in September 2022

Let us hear from some teachers on how they have begun making these key shifts in their teaching and learning while co-developing and trialling resource packages with AEB, so as to support the fraternity in implementing the 2023 Music Syllabus.

to access the Primary and Lower Secondary Music Wikipage for the latest information and resources on the planning and implementation of the 2023 Music syllabus.

Acquire and apply musical skills, knowledge and understanding through Listening, Creating and Performing

NEW A new aim has been included to foreground the importance of strengthening the acquisition and application of musical skills, knowledge and understanding through Listening, Creating and Performing, which are key in building students’ musical understanding.

The Music Curriculum Concept acts as an organising frame for teachers to ensure coherence and alignment across the planned curriculum, pedagogy and assessments.

The Learning Outcomes are anchored on the Musical Processes (Listening, Creating and Performing). Teachers should weave in the corresponding “Musical Elements and Concepts” and relevant contexts under “Making Connections” in the lesson design as students engage in the three Musical Processes.

Christine shared how she used the Music Curriculum Concept as an organising frame in planning learning experiences for her students.

Core Understandings derived from Philosophy and Purpose of Music Education

Before we began planning the resource package that introduces music from Thailand, Adrian and I searched for resources online and at the National Library for inspiration. We found many resources but were unsure how to incorporate these into our lessons. Questions that came to our mind were, “What musical elements and concepts should we cover?” and “How could we introduce the content to the students?” The Music Curriculum Concept helped us organise and plan our resource package from the resources we have gathered, while ensuring coherence and alignment in the activities. We decided to teach the concept of texture and the roles of the instruments in a Thai ensemble. This was done through playing of the song Loy Krathong in heterophonic texture using Orff instruments to simulate a Piphat ensemble. The song Loy Krathong was also chosen because it is commonly sung at the Loy Krathong Festival and the tune offers opportunities for creating and performing activities.

Core Understandings help students find greater relevance and purpose in their music learning by making connections between music and their daily lives and applying their music knowledge, skills and understanding in real-world contexts. Core Understandings can be facilitated by:

a. Providing students with relevant guiding questions that support students in Listening, Creating and Performing activities; and

b. Bearing the Core Understandings in mind when teachers design and plan lesson experiences.

Adrian shared his thoughts on how he applied the Core Understandings in his lessons:

Besides designing learning experiences that are closely aligned to the Knowledge, Skills and Values (KSVs) in the syllabus, it is also important to help students find purpose in their learning.

Students performed Loy Krathong as a class using Orff instruments to simulate the Piphat ensemble. To allow students to have a richer understanding of music and cultures, I used the Core Understandings to guide them to think about how the music reflects the mood of the Loy Krathong Festival and relate that to the music and mood associated with festivals celebrated in Singapore.

Through the lesson trial, I observed that my students responded better when they understand the intent and relevance of the lesson content.

Singapore’s music scene reflects the rich histories and diversities of our multicultural society. Songs that are sung and loved by the community over generations and have become part of our shared heritage, such as Jinkli Nona, are included as Core Repertoire.

AEB organised a learning journey to the Eurasian Association, Singapore, for teachers who are co-developing the Jinkli Nona resources. Charmian and Gracia share their reflections about the song and its significance to our community:

Teachers involved in the co-development of the Jinkli Nona resource package for Stages 2 and 3:

It is interesting to know that the lyrics of Jinkli Nona are in Kristang, a language spoken by Eurasians of Portuguese and Malay ancestry. With its lyrics reflecting traditional values of marriage, Jinkli Nona is usually sung at weddings, and accompanies the Branyo, a traditional social dance.

During the visit to the Eurasian Association, we were taught the Branyo. We discovered that the Malay’s Joget dance is believed to be derived from the Branyo

I believe children learn best through movement and it was exciting to teach our students the learning to sing Jinkli Nona. We may be fearful about teaching dance. However, if we look deeper, we would be able to highlight musical concepts through the dance.

Teachers can organise learning journeys to different arts and cultural organisations to learn more about music from different cultures. This visit sparked our interest about the music and deepened our understanding about the Eurasian community.

This visit sparked our interest about the music and deepened our understanding about the Eurasian community.

Dynamic Repertoire is also introduced to broaden students’ awareness of Singaporean musicians. This includes vocal and instrumental music of different music traditions in both traditional and contemporary styles.

Wendy shared what inspired her team to co-devealop a lesson package based on the Dynamic Repertoaire, Sisters’ Islands, and her thoughts about teaching orchestral works to lower primary students.

Here are the teachers involved in the co-development of the Sisters’ Islands resource package for Stage 1:

Orchestral music can be accessible, fun, and enjoyable as students could make connections on how the choice of instruments brings about the effects, moods and feelings of the characters and settings.

We were drawn by the “Nanyang flavour” characteristics in Sisters’ Islands. For this programmatic composition, local composer Wang Chenwei drew inspiration from our folktale of Sisters’ Islands which resides in the south of Singapore. The timbre of the Chinese Orchestra, together with the Pelog scale used in the piece, encompass elements and characteristics that highlight Singapore’s multi-ethnicity and diversity.

We used to think…

Orchestral music could be too abstract for the students to relate to and appreciate. As some of these musical works were rather lengthy, lower primary students might not have the attention span to listen to the whole piece.

Now we think...

With careful planning and in selecting appropriately sized extracts when trialling the resource package, we observed that orchestral music can be accessible, fun, and enjoyable as students could make connections on how the choice of instruments brings about the effects, moods and feelings of the characters and settings.

The syllabus has a stronger focus on the music from Southeast Asia to provide students with a deeper appreciation and understanding of our regional neighbours. By exploring this varied repertoire, students could appreciate its social, cultural and historical meaning, and develop greater awareness of the people, musicians, and composers of the region.

Teachers involved in the co-development of the resource package on Music from Thailand for Stage 4:

Here are Christine’s thoughts about the importance of teaching music from a different culture:

Students should be exposed to different types of music as this provides exciting prospects for new expressions of musical creativity.

With a lack of resources and connections to culture bearers, music teachers may be hesitant to expose students to Southeast Asian music. However, I think it would be important and not difficult to introduce our students to such music. Even with limited cultural competency, teachers can gain confidence, skills, and resources to further educate themselves through collaborative research on the musical practices to share it well in the music classroom.

Three Key Music Pedagogical Principles are introduced to guide teachers in selecting the blend of pedagogies that would best facilitate students’ music learning.

Facilitating Critical, Creative and Reflective Thinking in Music

Foregrounding Experiential Learning in Music

Growing Student Agency and Empowerment

This helps to focus on the three Musical Processes and to tap on the multi-dimensional nature of music experiences.

Experiential learning in the music lessons can engage students and also motivates them to explore and experiment with different musical materials. It also gives students greater assurance to create, perform and share their ideas with their peers.

We designed our lesson package on Sisters’ Islands to allow students to experience music in different ways by taking on the roles of audience, performer, and composer. Firstly, students experienced Sisters’ Islands through active listening by moving the streamers in response to music. I noticed that students were able to pick up musical elements such as tempo and dynamics through this activity. Students also recited a speech chant to accompany the piece, allowing them to be fully immersed in the story through role-playing.

This helps to focus on the development and application of Music Discourse, as well as Critical and Inventive Thinking.

Following these ‘listen and respond’ activities, the rhythmic patterns and Pelog scale elements found in the music were highlighted and introduced to students. They then applied their understanding of the rhythm and the Pelog scale to create and perform their melodic compositions to complement the programme music of Sisters’ lslands.

Music is a natural avenue to develop creativity, critical and reflective thinking, and metacognition through inquiry, discovery, and sense-making. We included the use of “Praise-Question-Polish” in the Jinkli Nona resource package to challenge students to think and reflect on the musical decisions they make while listening, creating, and performing.

Students use this thinking routine to provide peer feedback to improve each other’s group performance. Students would also take into consideration how to balance and blend the melody and accompaniment parts played on different instruments. This allows students to find more relevance, meaning and purpose as they prepare for their performances.

This encourages multiple ways of expression and engagement, which develops students’ voices and helps them find personal meaning and purpose in music.

When teaching students to perform the melodic line for Jinkli Nona, students can exercise their voice and choice in the instruments they would like to play.

The resource we created also provides both standard and graphic scores for students to refer to. Students who are familiar with note-reading could choose to refer to the standard scores, while those who require more assistance could access the same musical materials through the colour-coded graphic scores. With such resources, the music classroom becomes more inclusive towards students with diverse learning needs and would also nudge them to progress further.

Previously, I would spend much time in helping the low readiness students. Now, I would reconsider the materials to cater to the diverse student profiles, to include catering to students of higher readiness levels.

Alongside the Key Music Pedagogical Principles, there is also a stronger focus on the use of Differentiated Instruction and Blended Learning (BL) approaches in the new syllabus. Here is an example of how BL could be incorporated into the music classroom.

In our resource package for Music from Thailand, we created the resources in Student Learning Space (SLS) to allow teachers to use multimodal online learning resources to meet students’ diverse learning needs and allow them to access learning anytime, anywhere. It would also enable students to receive more targeted and timely feedback to improve their understanding and performances. By allowing peer feedback using Interactive Thinking Tools and teachers highlighting good examples within the platform, students can make refinements to their musicking performance using the suggestions on SLS when they are back in class.

While primary and lower secondary Music is non-examinable, quality assessments are very important for teachers to monitor students’ progress, give them a goal to work towards and guide them to take ownership of their learning. In designing assessment tasks for diverse students’ profiles, teachers need to adhere to the three key principles of assessment – validity, reliability, while considering students’ well-being.

In the performing activity for Jinkli Nona, different levels of assessment tasks were designed to cater to students’ readiness. Teachers would be able to match to the suitable Knowledge, Skills and Values (KSVs) depending on what is to be assessed.

Through the different assessment tasks, there would be opportunities for students to work as individuals, in pairs or groups. During the lesson, students would be required to provide peer feedback through “Praise-Question-Polish”. I would model how students could give feedback. This would provide clear expectations on what is required and how students can use the information to improve their learning.

The various assessment activities allow students to develop socio-emotional competencies and higher-order thinking skills as they collaborate. Student self-assessment also builds metacognition and encourages them to own their learning.

As Music teachers, we can create opportunities in the music classrooms that would bring about greater confidence in students’ expressive and collaborative skills, deepening their socio-cultural awareness, and growing their sense of belonging to Singapore. Hence, we play a key role in determining how music can shape our students’ lives and contribute to their development to thrive in an increasingly complex and uncertain world. We take to heart that in carrying out this important responsibility, we are never alone in figuring out how to realise it for our students. As the saying goes,

“No one can whistle a symphony. It takes a whole orchestra to play it.”

Let us continue to connect, collaborate and create as a community of Music teachers to progress together in this next mile of Music Teaching and Learning envisioned by the 2023 Music Syllabus.

Another semester of new musical experiences with STAR. We’ve put together a roundup of highlights that have been taken place.

Filming session in the city for the Friends In-Concert Choir ensemble

STs and LTs listening to a guest speaker at an Inclusive Music Classroom workshop

Beginning Teachers (Sec) trialling musicking routines during a session on positive classroom culture

Participants improvising on xylophones during the O-Level Music: Teaching of Jazz workshop

Participants learning about musicals in the Primary classroom at Engaging With Songs workshop 8C/1

Large Group performance in a popband setting during Full SBB PD Workshop

Understanding musical concepts through different types of movement during an Orff Approach workshop

Creating Sound-based Arrangements using a DAW with Philip Tan

Discussion of group ensemble performance during the Why Music and SEL in Primary Music (Series 2) workshop

Chau Poh Lin Susanna

Deputy Director (Music)

Susanna_Chau@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1558

Chua Siew Ling

Principal Master Teacher (Music)

Chua_Siew_Ling@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1554

Li Yen See Master Teacher (Music)

Chan_Yen_See@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1499

Suriati Bte Suradi

Master Teacher (Music)

Suriati_Suradi@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1498

Kelly Tang

Master Teacher (Music)

Kelly_Tang@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1561

Woo Wai Mun Marianne Academy Officer (Music)

Marianne_Woo@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1555

Matthew Kam-Lung Chan Academy Officer (Music)

Matthew_Chan@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1497

Ong Shi Ching Melissa Academy Officer (Music)

Melissa_Ong@moe.gov.sg

+65 6664 1495