Tan-Chua Siew Ling

Copyright ©2016 by Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR) Ministry of Education, Singapore

All rights reserved.

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright. No part of it may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts.

Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts moe_star@moe.gov.sg www.star.moe.edu.sg

Project managed by Straits Times Press Pte Ltd Singapore Press Holdings stpressbooks@sph.com.sg www.stpress.com.sg

ISBN: 978-981-09-8449-6

Printed in Singapore

Writer: Hong Xinyi

Photographer: Desmond Wee

Art and Music Educators:

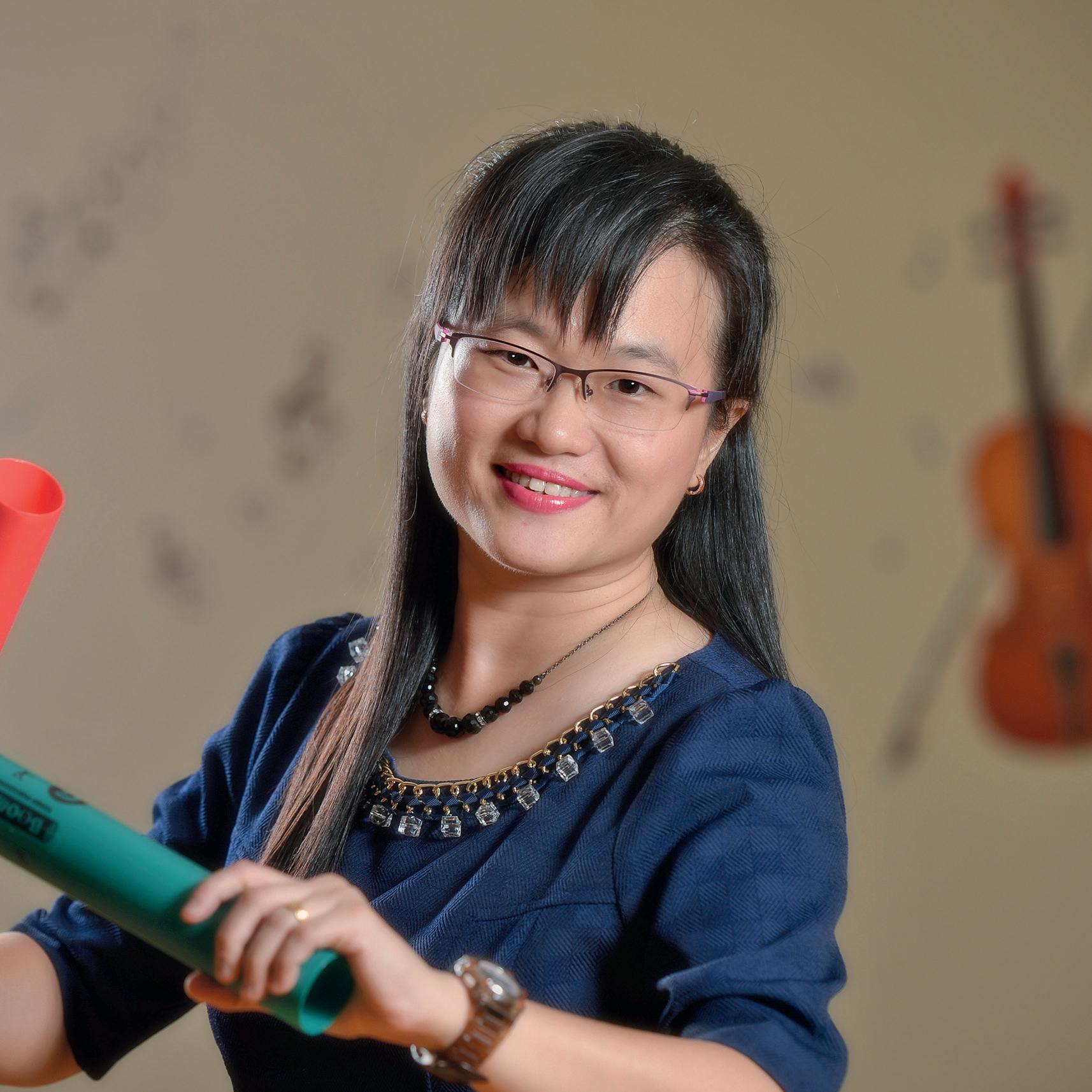

Ms Adeline Tan

Subject Head for Aesthetics

Bishan Park Secondary School

Mr Benjamin Yeo Music Teacher

Anglo-Chinese School (Independent)

Mrs Clara Lim-Tan

Principal

Yu Neng Primary School

Mr Clifford Chua

Principal

Palm View Primary School

Mrs Dawn Kuah

Subject Head for Aesthetics

Dazhong Primary School

Mdm Gan Ai Lee

Subject Head for Art

Endeavour Primary School

Ms Hew Soo Hun

Subject Head for Art Elective Programme

Nanyang Junior College

Mdm Ira Wati Sukaimi

Lead Teacher for Art

Mayflower Secondary School

Ms Leong Su Juen

Music Coordinator

Pasir Ris Secondary School

Ms Ler Jia Yi Art Teacher

Yew Tee Primary School

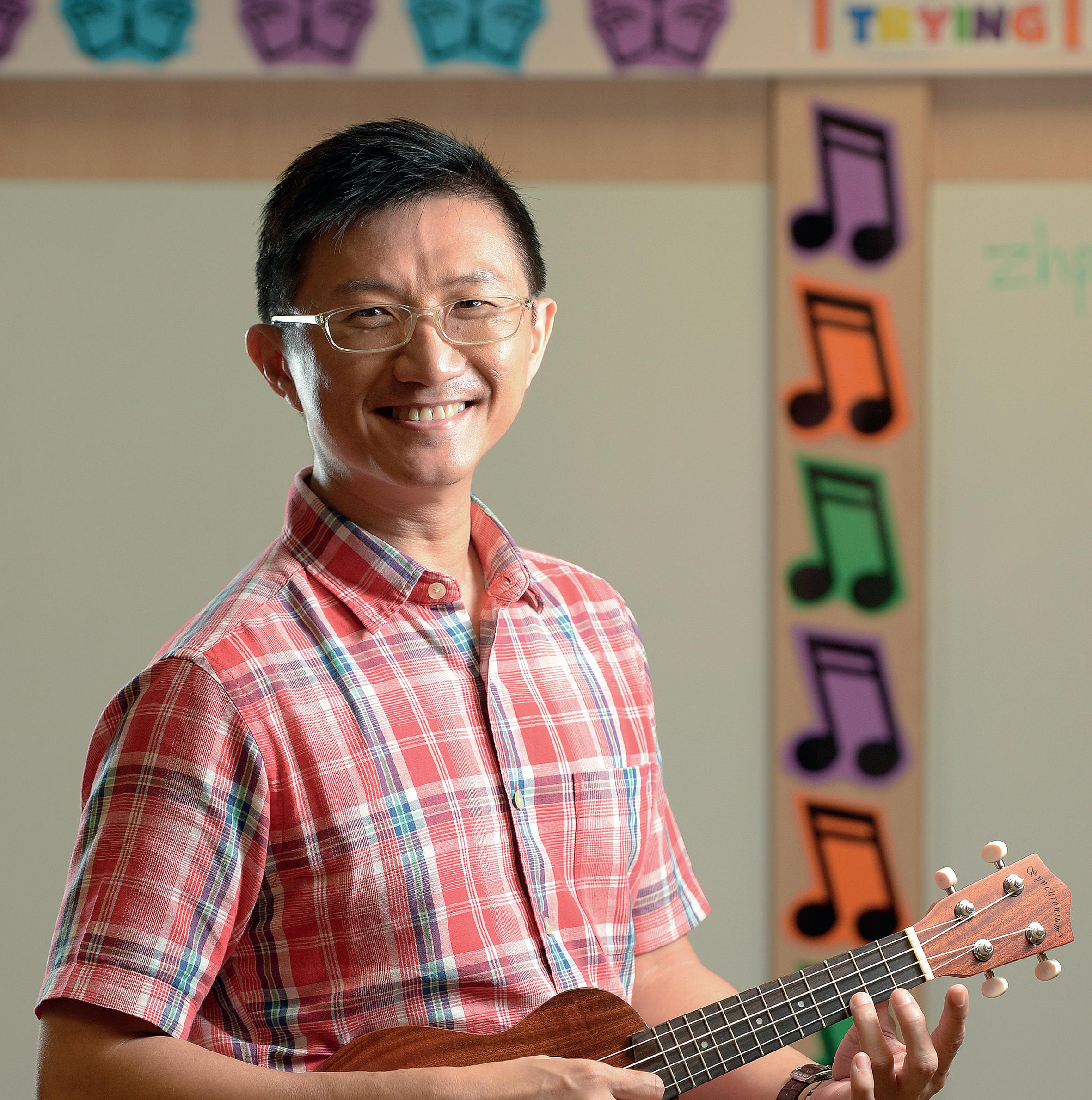

Mr Loo Teng Kiat

Lead Teacher for Music

Zhenghua Primary School

Mr Murugesu Samarasan

Senior Teacher for Music East View Primary School

Ms Ng Siew Kuan

Lead Teacher for Visual Arts

Ang Mo Kio Secondary School

Mrs Siti Anis Osman

Senior Teacher for Art

Naval Base Secondary School

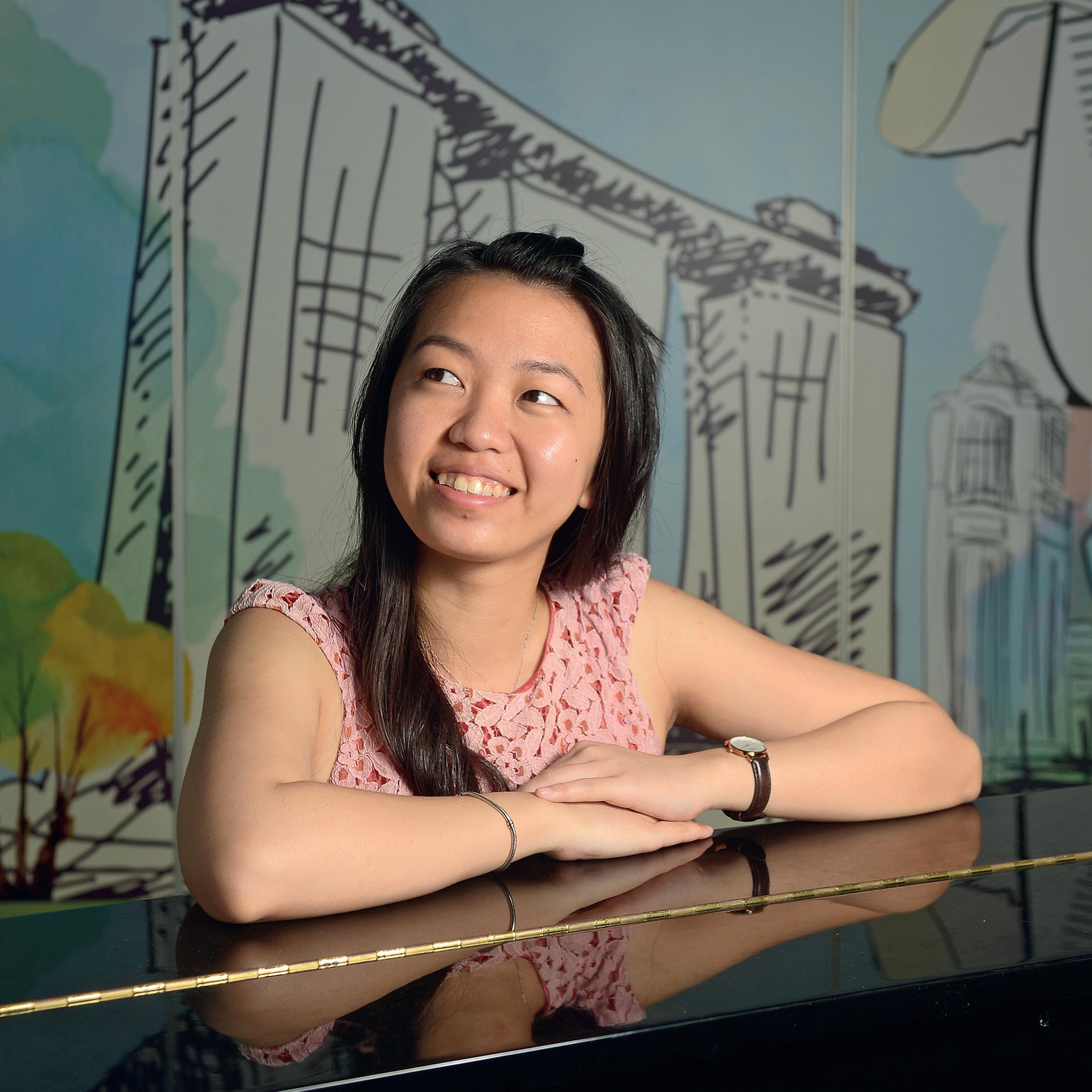

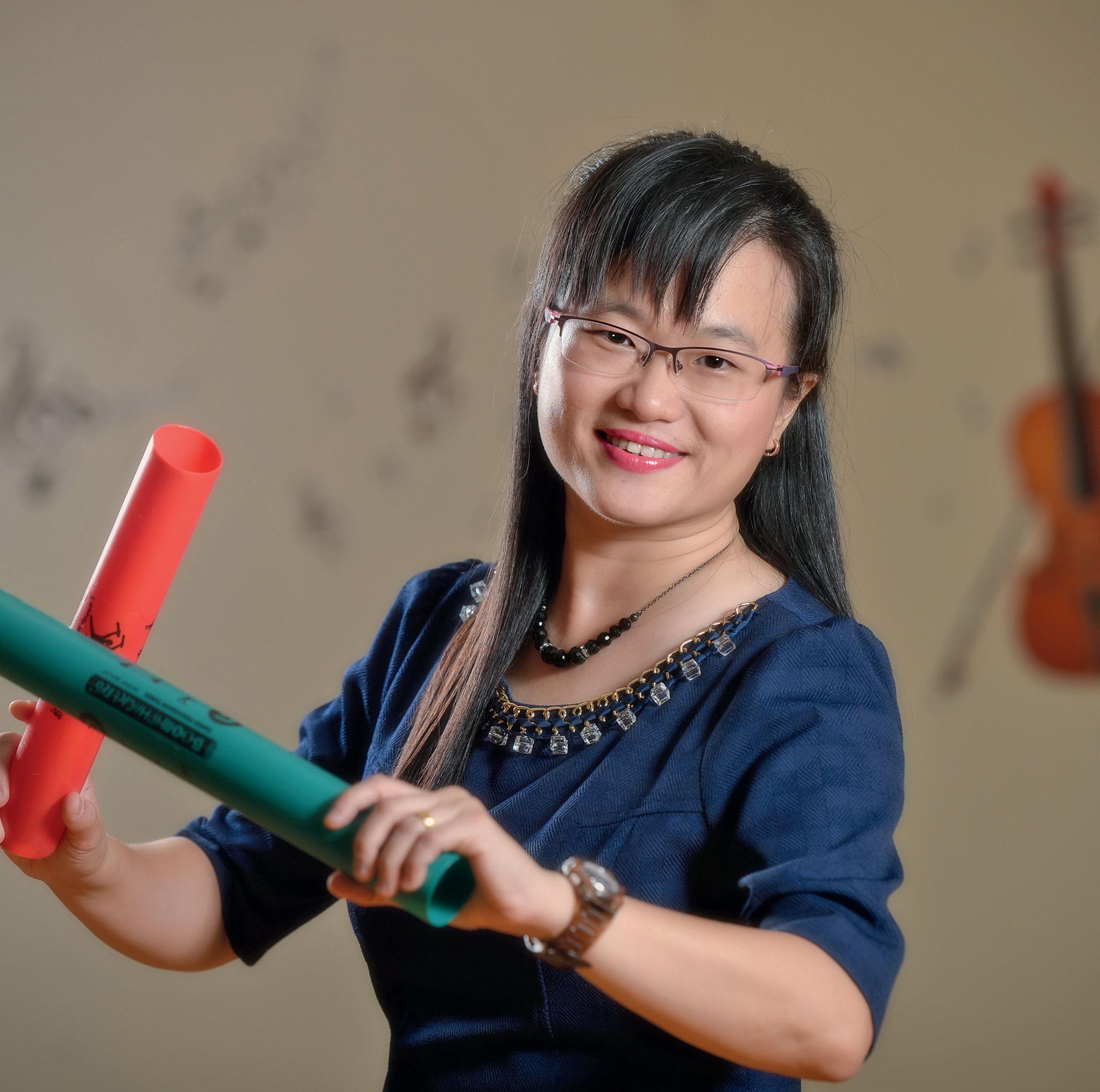

Mrs Tan-Chua Siew Ling

Master Teacher for Music

Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts

Mr Tan Siang Yu

Head of Department for Aesthetics

Hwa Chong Institution

Portraits II continues to collate the narratives of educators who share their personal philosophies teaching art and music. Each shares his or her passion and dedication in not only building a learning environment that is conducive, but also long-lasting teacher-student relationships built on trust, mutual respect and care. Their stories, anchoring in their belief that every child matters, contradict all misconception that art and music teaching is ad hoc and laissez-faire. Many a time, the studio may appear like a battlefield, but in fact, the teacher is being steadfast in encouraging students’ exploration through art and music, thereby leaving an indelible mark on them.

The way we communicate our ideas through our lessons nurtures our students’ social and emotional learning. The teachable moments created by my teachers have not only been embedded as fond memories of a great arts lesson that I had, but have also prompted the development of my deep respect for the mentors who provided me with the learning opportunity to access the arts.

The narrative inquiry is carried through from the first volume, exploring the identity of the Singapore arts educator. The unique beauty of each educator’s story reminds us of why we teach the way we do, and encourages us to be inspired by everyday moments, to continue creating, collaborating and transforming.

Rebecca Chew

Principal, Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts

Making art a part of life

Shaping indelible encounters with art

Tan-Chua Siew Ling

In 2014, Master Teacher for Music Tan-Chua Siew Ling signed up for a two-week professional development course in the Republic of Ghana. She was intrigued by the course’s pairing of African music and the Orff approach, which teaches music concepts through elements like movement, play and improvisation.

“I felt it was an interesting combination of Western pedagogy and nonWestern music, and I wanted to see what that would be like, and whether I could get any ideas from the experience for our work at the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR),” she says.

To prepare for her trip, she started learning how to play the djembe, a West African drum. But when she got to Ghana, she realised that while the worldwide popularity of the djembe had made the country the world’s largest producer of these drums, this instrument was in fact not widely played in Ghana itself. “Each ethnic group there plays a variety of drums. The djembe is associated with a particular ethnic group, and it is just one among their many drums,” she explains.

This improved understanding of a musical culture was a good reminder that popular perceptions can sometimes elide the nuances and complexities of how music is conceptualised, practised and disseminated in different cultures.

This topic is of particular interest to Siew Ling, who studied ethnomusicology at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, in the United Kingdom. “There are so many different kinds of practices and thinking about music. Knowing that, I am more careful about using certain language and not narrowing students’ ideas,” she says.

For example, the concepts of notation, melody lines and rhythm can be very different in different cultures. In Ghana, where drums play a central role, the understanding and use of rhythm are much more complex compared to that in the Western classical tradition. Each set of rhythms is named, each drum plays a specific pattern that combines with those of other drums to form a set of rhythms, and the meters of the rhythmic lines create a polyphony of sound patterns.

This sensitivity to cultural differences has broadened her perspective about teaching music, says Siew Ling, who was formerly the Vice-Principal at Deyi Secondary School. “What makes music music is the sound that is produced, rather than

what’s notated on paper. Developing the ability to make sense of these sounds, rather than interpreting a score, can be a more engaging way to learn music,” she believes.

Siew Ling was instrumental in driving the Centre of Excellence for Performing Arts for the North 6 Cluster schools, and also contributed to music syllabus development as a Curriculum Planning Officer at the Ministry of Education. She has been at STAR since its inception in 2011.

As a Master Teacher, she anchors the teaching of its milestone programme, Teaching Living Legends. Designed for educators teaching General Music at the primary and secondary levels, the programme features content like Indian Orchestra and Malay rhythms, and it aims to deepen the approach to teaching Singapore music.

“We want to raise awareness of the music traditions that still live among us in Singapore, and the narratives behind these traditions,” says Siew Ling.

“The context of music is also what makes it meaningful –how it is performed, the composers’ stories and how they put the pieces together, the constraints and the impetus that led to the creation of the music. Understanding and appreciating these aspects can make the learning more meaningful.”

From her trip to Ghana, Siew Ling brought home some ideas about how to teach Malay rhythms using Orff techniques like games and body percussion. Traditional Malay music also displays a sophisticated use of rhythm, and pays particular attention to how timbre gives a rhythm pattern a distinct character. “It is exciting to see students become more open to understanding our heritage and how these practices exist in our lives,” says Siew Ling. “In the future, if they hear these rhythms at a Malay wedding, for example, they will have a better appreciation of this music.”

Having taught the Music Elective Programme as well as the General Music and Normal (Technical) Music programmes, Siew Ling understands the challenges teachers face when engaging with different student profiles.

As a Master Teacher, she believes she serves as a sparring partner of sorts for the teachers whom she mentors. “We think through issues and questions together, generate ideas, and challenge one another in positive ways. That requires respect for one another, because we are sharing our experiences and by doing so, we are being vulnerable.”

Besides undertaking research work to inform the workshops she conducts for teachers, she also spends a lot of time observing teachers in their classrooms, sometimes co-teaching with them.

“Seeing the disposition of a teacher in action conveys a different understanding,” she believes.

“Some things are very hard to code in words; you have to see it. That’s also why I believe in using videos to stimulate discussions about what good teaching is.”

In fact, she shares: “A question I always ask myself is, what does good music teaching look like? It’s a question I’m still asking, and there is a lot of room for reflection.”

She ventures to answer: “It really depends on the student profile, and the context and purpose of the lesson.

“Good teaching can look very different with different approaches. Sometimes the students may look disengaged and the class is messy, but it might not really be so. I’ve seen classes where the students appear to be fooling around, but can articulate very clearly how they are experimenting with sounds when I ask them.”

Much like a musical culture, the ecology of a classroom can, in fact, be very complex. “It’s a very nuanced art, teaching.

Everything you say and do, even the way you look at students, all communicate what you want as a teacher and your hopes for the students,” she says.

“Students respond to not just what you say, but also your non-verbal communication. How much affirmation to give, how critical you want to be, all these things make a lot of difference to whether they are engaged in their learning. Every second in a lesson can make a lot of difference to each child. Having that heightened awareness of where each individual student is at, is actually very demanding for teachers and something we all aspire to do.”

It’s a very nuanced art, teaching. Everything you say and do, even the way you look at students, all communicate what you want as a teacher and your hopes for the students.”

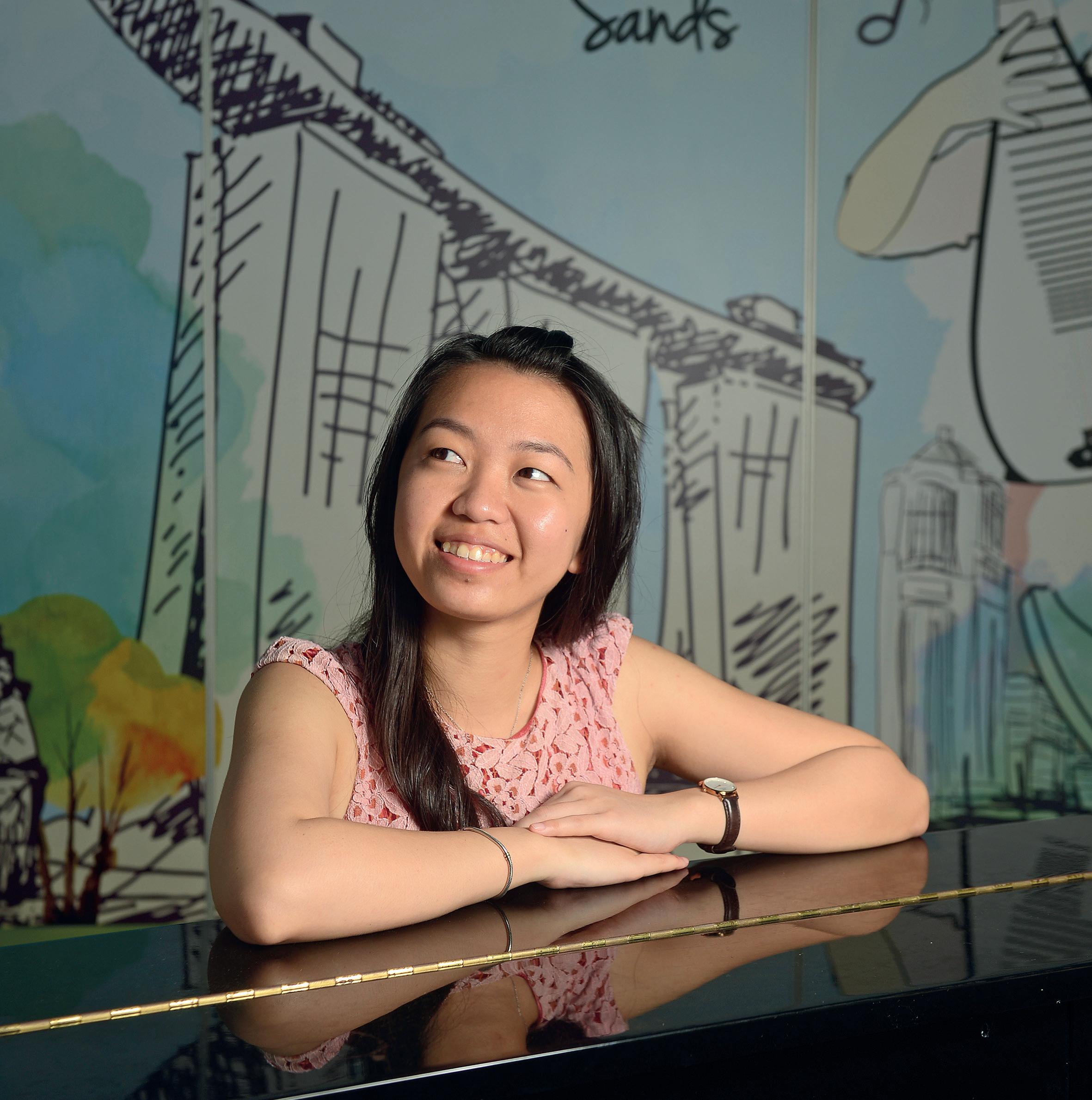

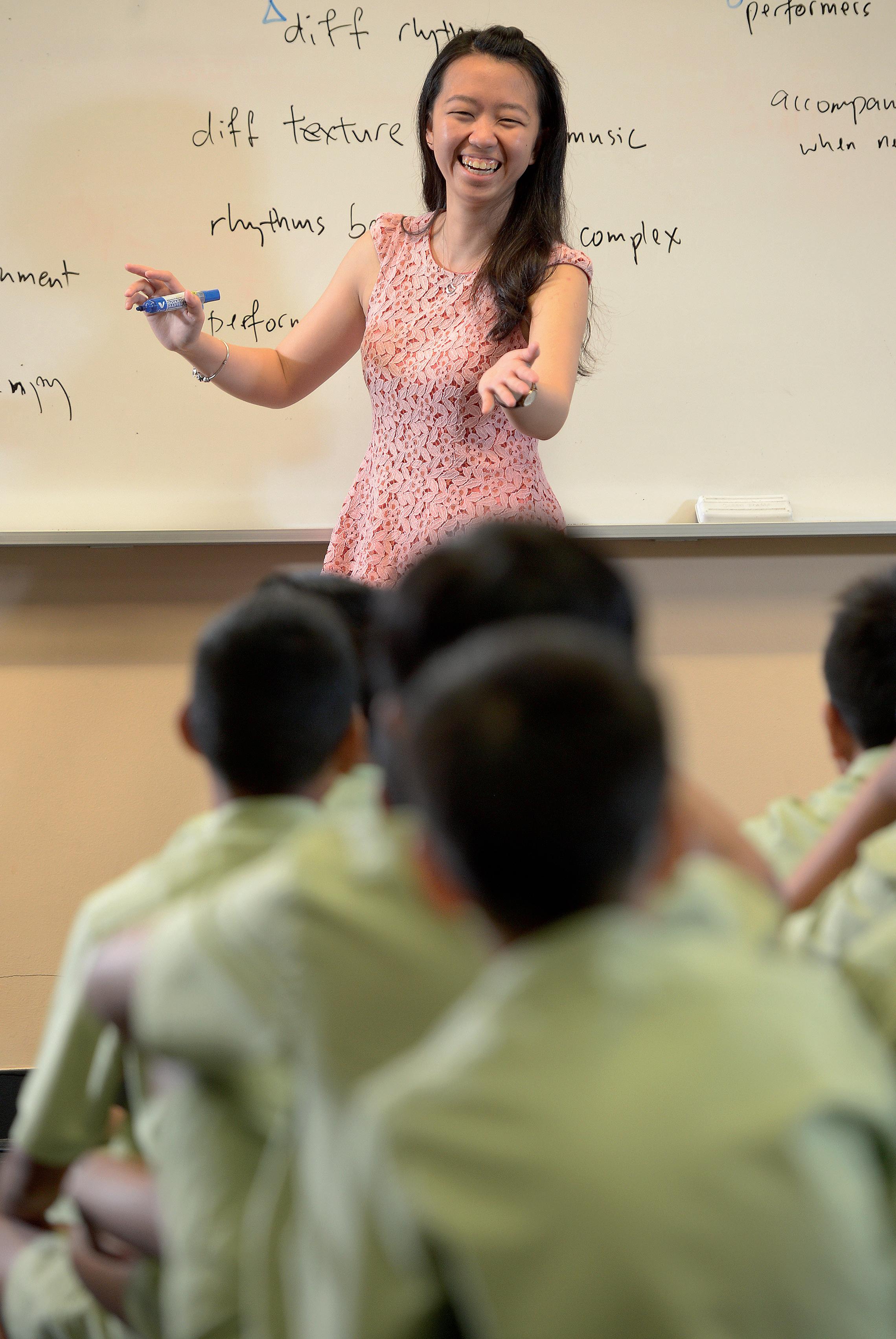

Music teacher Adeline Tan may like jazz more than pop, but she has more than a passing interest in Top 40s hits. The Subject Head for Aesthetics at Bishan Park Secondary School knows that using a pop song familiar to her students can make all the difference when it comes to capturing their interest.

“I don’t force classical music on my kids,” she says. “A pop song like Bruno Mars’ Just The Way You Are, for example, uses just three chords throughout, but I will ask them to pay attention to how the song tries to capture their attention –the different ways that make the chorus interesting, the way the song plays with

dynamics and phrasing. This gives students that easy access, and once they grasp the concepts, I may slip in one piece of Western classical music to reinforce their understanding.”

Adeline became interested in music as a child due to the golden oldies her father blasted on the hi-fi every Sunday, so she understands the allure of a catchy pop chorus. She is also no stranger to the tedium induced by rote learning – practising the same pieces of classical music over and over again to pass her piano exams used to bore her to tears.

A church friend rekindled her enthusiasm by explaining to her that understanding what the music was trying to tell her would help her better appreciate the composer’s intent. Later on, her piano teacher at the National Institute of Education, Ms Yuko Kamimoto, further strengthened her understanding of music by reminding her that it was not about hitting the right notes but rather about telling a story.

Performing during church services with a band also kept her love for music alive. “I was interested in different genres, so I would add Latin rhythms to certain hymns or infuse jazz elements. The church members were very appreciative, and that spurred us to play better.”

Still, when she became a music teacher, Adeline took a while to figure out how to make music classes more engaging for her students. Initially, she went about it in a conventional way, explaining music theory and attempting to engage them in music appreciation. “It completely bored them. I was facing so much difficulty engaging them, and it was demoralising for all of us,” she says. “I realised I needed to change. I needed to go into something they enjoy and draw out the learning points from there, to engage them in music making.”

Eventually, she found a key source of inspiration — the Informal Learning pedagogy pioneered by Professor Lucy Green from the Institute of Education, University of College London in the United Kingdom. In this framework, students choose to learn music they like, and master musical skills through listening, performing, and peer support, with the guidance of teachers.

Adeline became acquainted with this pedagogy while pursuing her master’s degree in Music (Performance Teaching) at the Music Conservatorium of Melbourne, University of Melbourne in Australia. “Initially, I thought applying Informal Learning principles would just lead to a mess. How is it possible for students to be motivated enough to practise and perform when left on their own?” she recalls.

But she changed her mind after seeing how these principles were put into practice as part of a Musical Futures programme in an Australian school.

“The students had no formal music background. They chose a song and figured out how to play it as a group, and you could see the effort they put into working together. It appealed to them because they got to use the same instruments you hear in pop music. This pedagogy was able to connect with students who were not interested in showing up, and draw them back to school,” she remembers.

In 2014, she introduced a similar framework to music lessons at Bishan Park Secondary School. Adeline started the students’ learning process by first teaching them basic chords on the keyboard and guitar, and the basics of drumming.

She says: “Once they learn the basics, they have to choose a song and figure out how to play it. They can Google a chord they don’t know how to play, or the ones who know more will teach the others. It gives them a sense of ownership over the learning process.” Working in groups, students are connected via headsets to a mixer that allows them to hear one another’s music-playing clearly, without interference from neighbouring groups’ music.

Pop is not the only style of music her students are given exposure to, of course. Adeline believes “that would be too skewed and not give them enough exposure”, so she also introduces Chinese, Malay and Indian music to give them a wider context.

While in Melbourne, she had started thinking more deeply about what defined Singapore music. “How can we encourage students to define and create music that we can say is Singaporean? One way is to give students exposure to certain

elements that are present in Chinese, Malay and Indian music.

“With that exposure, perhaps somewhere along the way when they are older, they can find some kind of relationship between all these different elements, and maybe in a hundred years or sooner, we will have a unique Singaporean sound. It could be a style, a chord progression, a rhythm or a scale that is derived from our understanding of our environment and culturally diverse society, that makes it instantly recognisable as Singapore music.”

She has also introduced her students to the evolution of Singapore pop music, and to current Singaporean singersongwriters and musicians, like The Sam Willows, Scarlet Avenue, Corrinne May, Shawn Kok and Regi Leo. In 2015, local acts Gentle Bones and Shigga Shay also kicked off youth outreach programme *SCAPE Invasion Tour at Bishan Park Secondary School.

“I want to let the students know that there are local musicians playing professionally,” she says. “If you can better understand how music works, when you attend performances in the future, you can explain why you like or don’t like something. I believe this will help to sustain the local music industry. If you don’t teach students how to understand music at a deeper level from young, when they grow up, they won’t be able to appreciate anything other than what’s on the radio.”

While it may be too early to tell if the approach to music lessons at Bishan Park Secondary School will produce any notable Singapore bands, it has already “worked wonders” in the classroom, she says. “You can see the students are totally engaged in a variety of ways.”

Some have also expressed interest in pursuing music further. One student told Adeline that she wants to pursue sound engineering at a polytechnic, and several who moved on to

Secondary 3, when music is no longer compulsory, still clamour to make music in their own time.

Adeline’s dream is for the school to tie up with companies that do sound and production, “to give continuity to students who want to keep pursuing music”, she says. “It would be great if they could get internships and gain exposure to the industry by working with musicians. If that can happen, it will give them greater impetus and inspiration to keep pursuing music.”

How can we encourage students to define and create music that we can say is Singaporean? One way is to give students exposure to certain elements that are present in Chinese, Malay and Indian music. With that exposure, perhaps… they can find some kind of relationship between all these different elements, and maybe in a hundred years or sooner, we will have a unique Singaporean sound.”

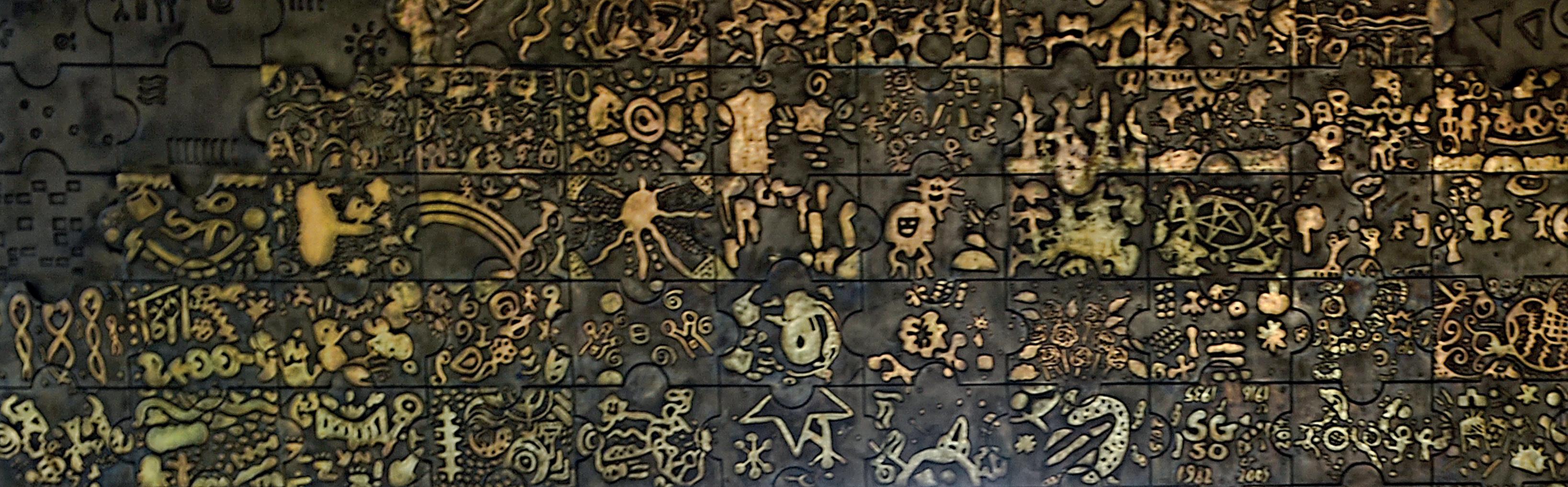

Siti Anis Osman

Believe it or not, Naval Base Secondary School Senior Teacher for Art Siti Anis

Osman used to find art classes pretty intimidating as a student. She can still recall the time a teacher singled out her artwork as “horrid” in front of the whole class, prompting her to run to the toilet for a good cry.

But she fell in love with art anyway, thanks to her late father, who was a teacher as well as a painter. “My dad was my biggest inspiration,” she says. “He loved to paint but never forced me to do it. I think for him, an artist is a person who wants to give, and art is not just for the snooty few who go to galleries.”

When she was growing up, her father would encourage her to journal instead of watching television, and this habit also planted a seed for her teaching methodology. Today, journaling is an important component in her art classes – each student is given a journal, which they have to fill with their reflections on assigned topics, as well as their own creative renderings.

“Students are empowered when they are anchored to what they do,” Anis believes.

“Through their journals, they can take every opportunity to react to an artwork, and I am able to know what’s going on in their lives. I also ask them to design the covers of their journals because I want them to be proud of what they carry – you see these journals and you know they are art students.”

Anis’ vivacious teaching style mirrors her lively personality. Before each art class, she likes to play music as a way to give the students a jolt of energy and set the mood for the lesson. She also comes up with quirky rewards as a way of motivating her students, like holding “an imaginary tea party in the south of France”, which really just involves humble canteen food and maybe some nasi lemak. “Simple things like these allow them to push themselves a little bit more,” she believes. “My motto is to put colours in their lives. Every time we do art, it’s about an indulgence of the senses.”

Making art a vibrant and engaging experience is important to her. “The moment they come here, we hope to instil that love for doodling. We want to enhance their learning. Art is about inquiring and embracing what’s out there.”

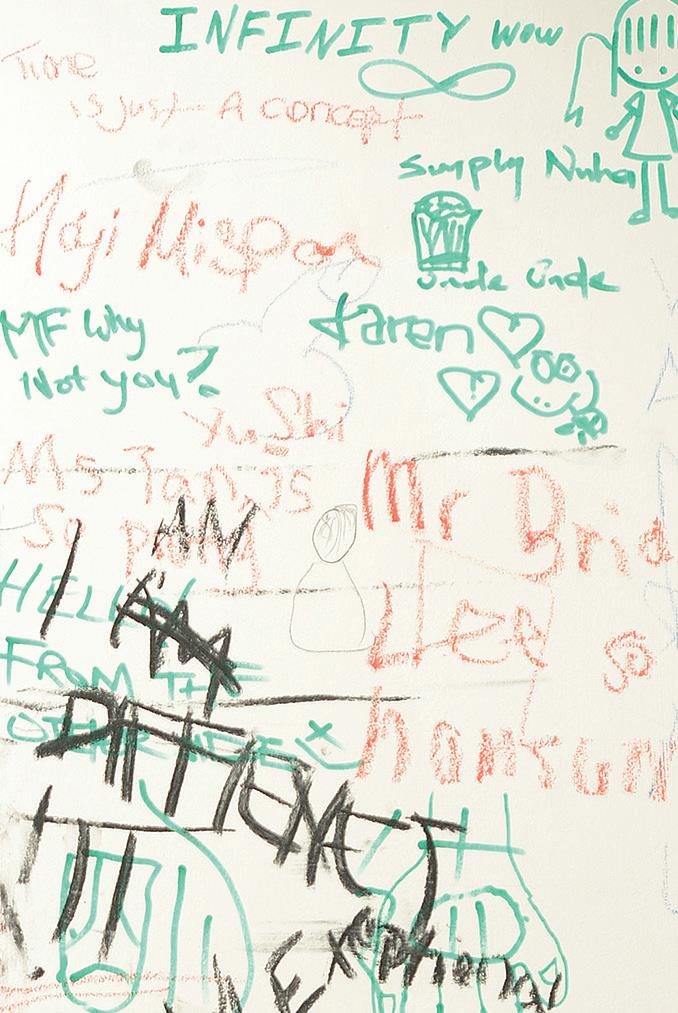

Naval Base Secondary School is known for housing plenty of striking artwork created by its art teachers and students, and the school even describes its campus as a giant art gallery. In 2015,

the mosaic panels and ceramic chimneys that adorn the school’s exterior earned praise from then-Education Minister Heng Swee Keat, who dubbed it the “Great Wall of Yishun”.

Painstakingly assembled from ceramic pieces created by the students, as well as objects donated by the community, some of these panels took six months to complete and students spent hours installing them under the hot sun during the school holidays. “When we were installing the artwork, a little girl would come every evening with her mother to visit us, and she asked her mum every night, ‘how much more do you think they will get done tomorrow?’” Anis recalls. “We invited her to the official opening, and she had the chance to meet the guest of honour, Member of Parliament for Nee Soon GRC Lee Bee Wah.”

She says: “Painting the wall would have been fast and easy, but we want to leave a legacy.

“Every child who comes here will now know it’s possible to love art and colours and explore your potential.”

The mosaic technique showcased on these walls is inspired by the art students’ visit in 2011 to Barcelona’s Parc Guell, a public park designed by Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí.

The use of mosaics on the walls is the most visible example of their exposure to a wider world of art, but hardly the only one. The school also houses a mosaic garden footpath, also inspired by Gaudí’s work, and a charming Lilliput Green where students have placed miniature ceramic versions of landmarks that represent the places they have visited, which include Asian and European destinations such as Japan, France and Spain.

These overseas learning trips are a good way to motivate the art students, and the impact of these experiences on them is immense. “Most have never been out of Singapore,” says Anis.

“When we are in these places, they will say, ‘Pinch me teacher, am I really here?’ They get to meet artists from all over the world, even exhibit their work. It’s empowering and something they will never forget.”

Being able to work on art inspired by these overseas trips also allows the students – and teachers too – to consolidate what they learned during those trips. “Every project makes us better teachers and dreamers,” Anis believes. “The 20 boys who did the footpath project were so engaged. The one whom I thought was the naughtiest – because he had that fierce look – turned out to be the leader who organised everyone. When we finished it, he said it looked beautiful with everything in place.”

From 2016, Naval Base Secondary School students have more opportunities to pursue art as the school is now one of nine secondary schools in Singapore offering the Enhanced Art Programme (EAP). “EAP exposes them to different mediums, and we also bring in different artists to share about their craft,” she says.

It is a development that fits right into the culture at the school, where art is very much a lifestyle, she says. For example, a longstanding signature event is the annual art exhibition, where students not only display their artworks, but are also in charge of publicity, installation, and designing the menus and invitation cards as well.

In the past year, the school has further broadened its art programme, in an effort to develop students into art enthusiasts, art practitioners, and future art leaders.

The curriculum was updated to include the study of digital media and various design disciplines, such as character design, fashion design and visual communications, so that students can learn to apply such artistic skills to real-life tasks and are given exposure to possible future educational and career pathways.

The school has also restructured its co-curriculum so that every graduand enjoys both breadth and depth of art learning, with an understanding of industry practices developed through interaction with practitioners from various art disciplines, such as design, urban art and fashion.

Under the Art Talent Development Programme, jointly developed with the National Gallery Singapore, students also learn about curating art exhibitions from experts. They will curate future editions of the school’s annual art exhibition – a task previously done by the teachers.

“We are surrounded in this school by beauty and kindness and teamwork,” says Anis, who has been teaching in the school for 20 years. “It’s easy for a child to be moulded in this environment to appreciate art.”

Students are empowered when they are anchored to what they do. Through their journals, they can take every opportunity to react to an artwork, and I am able to know what’s going on in their lives.”

Clifford Chua

What is the purpose of an arts education? Palm View Primary School Principal and former art teacher Clifford Chua has spent a lifetime trying to answer this question, as a student, an educator and a school leader. The answer at which he has arrived is informed by all these different perspectives. “The greatest value of art education lies in its ability to draw connections among seemingly separate and distinct things,” he says.

Clifford’s story begins in the 1960s in the rough-and-tumble neighbourhood of Amoy Street, where art became his main avenue of play. “I used to live in

a notorious neighbourhood and my mother didn’t want me to become a gangster, so I was not allowed downstairs to play with the other kids,” he says. To while away the time, the comics enthusiast doodled superheroes and assorted demons all over the paper-covered walls of his home. “My mother used to comment that my drawings felt so alive,” he remembers.

Encouraged, he continued to dabble in art in his spare time, teaching himself oil painting through books. By the time he graduated from secondary school, art had become a passion and a choice he was resolved to make. That meant he had to prove himself repeatedly. His art teacher at National Junior College, Mr Chia Hearn Chek, refused to accept him into the A Level art class since he had not studied art at O Level. Instead, Mr Chia issued a challenge – paint a still life. “I had never painted from life before, only from books. I spent three months painting a piece of velvet drapery, and I got in,” Clifford recalls.

Mr Chia later encouraged him to apply for a teaching scholarship. It took him two tries and months boning up on the different techniques needed to strengthen his portfolio, including in an apprenticeship with sculptor Ng Eng Teng, before he was accepted into New Zealand’s University of Canterbury. The only international student on its Christchurch campus then, he majored in printmaking and art history. The experience, especially in printmaking, was eye-opening. “The discipline needed to master the demands of the medium appealed to the methodical, scientific part of me. You have to go through the ritual of preparation properly, and really think it through and give it time.”

Following his studies, he was posted to Victoria School to helm the Art Elective Programme. The start of his teaching career

also kick-started a long process of questioning the purpose of art education more deeply. “I was determined to be a very good teacher, because I had had such great teachers. When I first started teaching, I had vague ideas of what teaching art should be about – that art should be about developing creativity, cultural sensitivity and being comfortable with ambiguity. It was an educational experiment,” he says.

In the late 1990s, building critical thinking skills had become an area of emphasis in schools in Singapore, in line with the Ministry of Education’s (MOE’s) vision of “Thinking Schools, Learning Nation”. Amidst these developments, “a friend asked me, why is art education so important that so much resources have to go into it?” Clifford recalls. “I left the conversation thinking that I really didn’t know the answer, and that prompted me to want to find out more.”

He decided to pursue a master’s degree in curriculum and teacher education in art education at Stanford University, where he further clarified his thinking in a paper he wrote. Titled ‘Why is Arts Education So Important Anyways?’, it was an attempt to clarify and defend the value of art education in developing cognition and creativity. “The discipline of art trains the mind to think differently,” he says. “Artists work in a state of ambiguity because the end is never clear, so we develop the disposition of searching for questions rather than answers. Writing the paper helped to give me a theoretical underpinning that crystallised what I was already doing as a teacher.”

He subsequently spent about four years in MOE’s Curriculum Planning and Development Division, where he was able to draw on these ideas. Art also shaped his approach to leadership, helping him when he was Vice-Principal at Radin Mas Primary School and Principal of Kuo Chuan Presbyterian Primary School. “I can work with ambiguity. I don’t have to have all the answers

given to me before I make decisions. I can see connections in disparate things and pull things together, because art helps you to build your own bridges.”

When he became Principal of the newly established Palm View Primary School in 2012, he recruited specialist art teachers and an experienced Head of Department, and worked with his teachers to develop the scope and sequence of the art curriculum for the school. He also champions the idea of ‘artizenry’ – the use of art to inculcate a strong sense of community identity. In 2015, for instance, students from the primary school collaborated with those from North Vista Secondary School to create artworks for an exhibition that raised over $8,000 for the Yellow Ribbon Project. The project sensitised the students to disadvantaged communities in Singapore and the importance of second chances in life. “They also learn that they have the ability to make a difference,” Clifford says.

With his many duties as a school leader, he does not have much time to create art these days. But he still keeps a visual diary whenever he travels. He took it along on a two-month sabbatical in 2014, when he did volunteer work in Cambodia and toured Europe to visit masterpieces like Spanish artist Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, Italian artist Michelangelo Buonarroti’s Sistine Chapel ceiling, and Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Família.

“It was a good break from daily routines and the time away helped me to rethink what is important. For me, experiences are important, because they shape people,” he says. “The thing about art is you have to experience it. You have to slow down, scrutinise and let the beauty flood your senses. It was great.”

For him, a good art lesson must draw from this experiential power and tap into art’s potential to build a sense of identity. In

his ideal lesson plan for a school excursion to National Gallery Singapore, he would first introduce students to paintings by Western artists who have influenced Singapore’s pioneer artists before showing them particular works in the gallery. He would then ask them to identity these influences and make comparisons, for instance, between works by Georgette Chen and French artist Paul Cézanne, or Chen Wen Hsi and Picasso.

“I would impress upon them the stylistic innovations of our pioneer artists, who combined these Asian and Western influences into a unique style called the Nanyang style. Our pioneer artists struggled with being dislocated from their land of birth. Having been influenced by international styles, they had to negotiate between these two influences and try to find their own voices,” he says. “That is what being Singaporean is about. We try to negotiate all the time between our identity as Asians and influences from the West, to carve out something that is uniquely us. Once students get that, they will understand that this place is about them, and they will be able to see themselves in these paintings. Once they experience what art has to offer, they will never forget it. And art will have changed them.”

Artists work in a state of ambiguity because the end is never clear, so we develop the disposition of searching for questions rather than answers.”

Gan Ai Lee Teaching self-expression

Ira Wati Sukaimi Exploring creative tensions

Gan Ai Lee

Endeavour Primary School Subject Head for Art Gan Ai Lee has a habit of photographing certain moments that occur during her art classes. These tend not to be snapshots of outstanding artworks. Rather, she has the instincts of a street photographer for the decisive moment when a normal day yields an instant of candid beauty, like her students’ expressions when they are entranced by something as mundane as raindrops on their skin, or when they are engrossed in an art project. She says: “I document them because I like that look on their faces, and I always wonder, how can I get you to look like that when I am teaching you?

I also show them the photos, because I want them to know what they look like when they are attentive. It’s a way of reinforcing their interest.”

Along the way, her students have also picked up on the language she uses to explain her photography. “Are you documenting my learning?” is something you might hear her students ask, and that comfort with articulating their questions and thoughts is very much an attribute she works hard to inculcate. “I believe in empowerment,” she explains. “The art students who have been with me since Primary One are very comfortable articulating their views. If I present a project, they know they can say to me – we like this theme but can we present a different way of working on it that works better for us? To me, that is ideal. I like that they question a lot, and that they don’t take my answer for the answer.”

For Ai Lee, nurturing this confidence in the validity of one’s voice is not a by-product of an art education, but rather the whole point of it. “I’m not pushing for them to be artists, but to think like an artist. To me, an artist is always curious, always questioning, and always pushing beyond the limits. The artist is always about that inner voice. We may not all have the profession of an artist, but we can all have the attributes of an artist.”

Here’s something else she feels strongly about: “When you don’t have your own voice, it’s very hard to help others find their voice.”

Art education has been instrumental in the journey of finding her voice. She began her career as a generalist teacher in 1993, teaching English Language, Mathematics and Art. In 2000, she enrolled in the National Institute of Education (NIE) to earn her degree. Despite not having taken Art at O Level and A Level, she appealed to be allowed to pursue art as a subject, and managed

to convince the Visual Arts faculty of her passion for the subject.

She knew she had a lot of catching up to do, so she worked very hard. Her course-mates helped by explaining things to her and advising her on what to read. She says: “My teachers made it a point to tell me they could see the beauty and passion in my rawness, that skills are not everything. That affirmation of my voice made me feel good.”

She graduated with honours, an achievement she chalks up to the power of that affirmation. That has influenced the way she teaches, as has being mentored by Singaporean artist Tang Da Wu during her time at NIE. He was a man of few words who never sought to impose his views on her work, she remembers. Instead, he simply asked her this question whenever they met for mentoring sessions: “Is that all?”

This approach sometimes pushed her to tears on days when she felt insecure about her technical abilities, but in retrospect, she found his respect of her art-making invaluable. “I chose him as a mentor because I wanted to be pushed, and he wanted nothing except for me to be me,” she says. “I want to encourage my students to believe in themselves in the same way.”

After graduating from NIE in 2003, Ai Lee opted to specialise in art as a teacher. “I witnessed how art education sparks students’ curiosity through artistic exploration, how it honours every child’s voice by valuing his personal interpretation, and how it offers the opportunity for collaboration in art-making and discussions. These are essential values in learning and affirmed my decision to contribute to teaching and learning as an art educator.”

Her way of encouraging students to be themselves is a tad less Sphinx-like than that of her former NIE artist mentor. Journaling can be a way to help the quieter students express themselves, she believes, while the more vocal students can require a different type of encouragement. “Those who try to

hide behind the loudness, when I tell them not to hide behind a mask by affirming their voices, I can see them making a deliberate effort to be themselves,” she shares.

Holding on to a strong sense of self is crucial, because “it is a very complex world now, and I see not only children losing their voices, adults are losing theirs too”, she observes. “Not all norms are suitable for everyone. It is particularly important to know where we want to go, and not always feel that we have to adhere to someone else’s dream. If one can find one’s inner voice, it can be much easier to find that balance.”

As an experienced teacher, Ai Lee continues to push herself to dig deeper into teaching and learning, and explore the benefits of an integrated curriculum. In the classroom, she is interested in exploring the potential of connecting art and literacy. In 2016, as part of a Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts study trip, she attended the National Art Education Association conference in Chicago in the United States. During one session, some participants – including her – were asked to look at a painting, and list descriptive words inspired by it. They then collectively created a poem based on the words from the list, and then, created new imagery based on their poem. “There was an extension of learning to language through art. I really liked how the integration between subjects can enhance students’ learning experiences.”

In 2013, she led art teachers from Endeavour Primary School in initiating a teacher-led workshop at the Academy of Singapore Teachers to share effective art teaching practices that foster emerging 21st century competencies with the fraternity. Subsequently, she collaborated with art educators from other schools to co-facilitate such sessions for both specialist and

generalist art educators teaching at the primary level. She hopes to deepen their professional capabilities through the exchange of pedagogical knowledge, and also empower fellow art educators to collectively contribute to a teacher-led culture of professional excellence. These teacher-led workshops continue to be conducted yearly.

Even when she is facilitating a workshop for teachers, Ai Lee still whips out her smartphone to capture those moments of engagement so that she can share the photos with the participants. Like her students, the teachers who attend her workshops have grown used to this. Some have even started photographing her, because “they say I’m always documenting others and there are no photos of me and my engaged moments”, she says with a laugh. “So I have started getting a lot of photos of me seen from their perspective, and I appreciate that sharing.”

I witnessed how art education sparks students’ curiosity through artistic exploration, how it honours every child’s voice by valuing his personal interpretation, and how it offers the opportunity for collaboration in art-making and discussions. These are essential values in learning...”

Ira Wati Sukaimi

What does an art teacher do? That’s the question that inspired an artwork by Lead Teacher for Art in Mayflower Secondary School, Ira Wati Sukaimi, and fellow art teacher Nurulhuda Mustafa.

Titled Searching Re-Search, the installation features rubber bands looped together (much like the rope used in the childhood “zero-point” rope game) and anchored to a weighted rod. It was displayed first in the school, and later at the 2016 a?edge exhibition featuring works by Singapore art educators. Visitors were invited to interact with the piece by stretching the rubber band rope in different

directions and playing with the objects incorporated in the work.

This artwork came about because veteran teacher Ira and newbie Nurulhuda were both “quite blur” when they were newly posted to Mayflower Secondary School, Ira shares with a laugh. “Over time, we realised that the same struggles emerged for both of us. It can be very difficult to concretise some of the things we do as art teachers. The discipline is such that there can be various entry points and solutions that are not that easy to map onto a standard lesson template. This can be hard to express to others, and that creates a kind of tension.”

She was intrigued by how the artwork triggered a variety of responses from students and colleagues. “The thing about art is you don’t have to interpret things the way I do. You can derive the meaning from your own experiences,” she says. “What is important is they think about their own experiences, times in their lives where they felt that tension.”

She credits the a?edge platform for giving her an important nudge for her art-making. “This discipline is very dynamic and we have to keep abreast of the trends and stay dynamic in our approaches,” she believes. “The process of making allows us to get feedback and forces us to look at what others have done with the same materials and themes.”

Ira has been teaching for 20 years, and spent three years at Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR) before joining Mayflower Secondary School in 2015. “I gained a lot from my experience in STAR and was able to do things I don’t get to as a classroom teacher, like seeing how other teachers conduct lessons and observing primary school art lessons. It was an eyeopener,” she says.

One of her most rewarding experiences at STAR was working

on the Artist Mentor Scheme, in which artists partner schools to provide professional development opportunities for teachers. “I spent a lot of one-on-one time with artists, and met many who genuinely care about art education and went all out to help our teachers,” says Ira. Sculptor and ceramicist Ahmad Abu Bakar, for example, was very patient and effective in his sessions with teachers, she remembers. “The way he asks questions prompts you to think deeper and reflect. He doesn’t give you answers, but he will ask questions to help trigger solutions.”

Her time at STAR sensitised her even more to the importance of pedagogical theories as a basis upon which she could identify weaknesses and strengths. Now that she is back in the classroom, she is eager to put theory into practice, and try new ways of engaging students that make art lessons more relevant to them and empower them to make choices.

When teaching art history, for instance, she has used French artist Edgar Degas’ ballerina paintings as a starting point to talk to students about their co-curricular activities. “Once they relate to the experience, they learn how to apply that idea,” says Ira. She asked her students to take a series of photographs capturing their peers in action, be it on the soccer pitch or in the dance studio. The exercise not only gave her a window into their world, but also allowed the class to tease out the symbolism and inferences in the photos together. In this way, “their understanding of the work becomes internalised”, she says.

Another lesson she remembers fondly came from her days teaching the Art Elective Programme in CHIJ Secondary (Toa Payoh). Using American artist Judy Chicago’s installation, Dinner Party, as a source of inspiration, she asked her students to pretend they were attending a lunch party honouring distinguished women who had made positive impact on the lives of women around the world. The students were allowed to

choose the guests they wanted at this imaginary gathering, and their selections ranged from ancient Egyptian queen Cleopatra to Albanian Roman Catholic nun and missionary Mother Teresa. They then conducted extensive research on these women, and made life-sized papier-mâché figures of them that were displayed in the canteen.

Not only did this 10-week curriculum tie in nicely with the school’s mission to nurture “women of distinction”, it also resulted in a very engaging experience for the students, Ira recalls. “The kids were very self-directed in identifying the contexts of these characters, and it engaged the entire school community.”

It is important for students to understand the enduring relevance of what they learn during art classes, she believes. “Art teaches us about culture, what happened in the past, and what could happen in the future. What they learn has value that endures beyond their years in school.”

Ira’s own experiences while she was an art student were certainly shaped by teachers who helped her see the value in considering different perspectives. In Secondary Three, she once forgot to bring paints for art class and so, crushed the orchids she was supposed to paint and used the juices as pigment instead.

She still remembers how surprised she was when her art teacher praised her solution and told the class this was how people used to extract pigments from plants. “She took that as a teachable moment, and I became more engaged,” says Ira, who confesses to not being an enthusiastic art student before that. “She made me see the subject in a different way.”

In the National Institute of Education, another teacher helped to open her eyes to the genre of performance art, pushing the class to explore adventurous themes outside the

classroom. “It was quite a tumultuous and powerful experience,” she remembers. “I feared that unpredictable zone at the time, but it did make me braver in exploring.”

This receptivity to exploration continues to influence her teaching approach. This year, for example, as a trial for immersive art pedagogy, she asked her Secondary One class to walk barefoot on grass, rocks and a wooden bridge before translating this experience into textures. “That was something different that they were not used to. A lot of students thought it was very icky,” she says with a laugh.

As a Lead Teacher for Art, she wants to reach out to more teachers and boost their morale and sense of motivation. She initiated an exhibition in Mayflower Secondary School featuring artworks by students and teachers, and invited cluster teachers to attend and give feedback on what she hopes will become an annual event. It’s a first step in making the work of art students and teachers more visible to other students and teachers, and she is convinced that the key to making an impact on the students is to first touch the teachers. “They are the ones who will cascade key messages to the students. If we can build up the teachers’ confidence and motivate them, they will be able to translate their passion to their lessons.”

Art teaches us about culture, what happened in the past, and what could happen in the future. What they learn has value that endures beyond their years in school.”

Tan Siang Yu

Tan Siang Yu, the Head of Department for Aesthetics at Hwa Chong Institution, has made more than 20 short films over the last decade and picked up quite a few awards along the way.

While filmmaking is a hobby he pursues outside the classroom, it is a passion that was first sparked by his beliefs as an educator, and that now also helps him teach better.

Around 2000, Siang Yu started including digital art and filmmaking in his teaching, as more new digital tools used in the creative industries started

becoming available for the classroom. “I realised as I started to mentor my students in these projects that I should learn a bit more about this discipline,” says Siang Yu, who studied Fine Art at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom.

So in 2003, he signed up for a course taught by director Wee Li Lin, and was bitten by the filmmaking bug. “Something just clicked. Even though there is a lot of stress and pressure in filmmaking, on a set I come alive. I really enjoy it,” he says.

While making his first short film, titled Heroes, he found himself trying to shoot a bus stop scene while perched on a road divider under the blazing sun.

The shoot wasn’t going very well and he was on the verge of giving up.

“Then Li Lin came to visit me, and she was very encouraging. She had also brought an umbrella and held it over me to shelter me from the sun,” he remembers.

“So I didn’t give up. The little things that a teacher does can make a lot of difference. I will always think of her as my teacher, even though she is younger than me.”

He often ropes in students to collaborate with him on these short films.

In Heroes, one of his students helped to create special effects like a close-up of a speeding bullet and a watch that transformed into a tiny gun.

His students also took on the main roles in another of his films, Short, and a number of them became interested in filmmaking after being involved in this production.

The themes Siang Yu explores in his films also sometimes reflect the issues he comes across as a teacher. For example, in The Red Umbrella, which he dedicated to his art students, he told the story of a girl who is stressed out by school and wants to escape into a fantasy world through her creativity.

His own engagement with filmmaking is one reason he encourages young teachers to carve out time to pick up new art disciplines they can continue to develop.

“Teaching is of course the first priority, but when you can understand a craft better, you can guide the students better as well,” he believes.

“In exposing yourself to learning, you also continue to understand what it is like to be a student and the different ways a student’s mind may work under different situations.”

As a student, Siang Yu was part of the Art Elective Programme at National Junior College.

In his two decades as an educator, he has witnessed firsthand how the programme has developed a more process-oriented focus, in which conceptual development is just as important as technique.

The ubiquity of technology like affordable editing software has also levelled the playing field, and students now also have more opportunities to gain exposure to the art world through experiences like school trips.

Some of Siang Yu’s students include tech entrepreneurs

Elisha Ong and Ryan Tan, up-and-coming artist and art writer Ho Rui An, and Esmond Loh, who won the UOB Painting of the Year Competition in 2012 while he was still a student at Hwa Chong Institution and is now represented by Chan Hampe Galleries.

“My hope is to continue to converse and collaborate with students after they graduate. In the initial years, as a teacher, you see only one part of who they are. It’s only when they come back as adults that you realise you played a part in their development,” says Siang Yu.

“As teachers, we don’t necessarily have to hold the brush

and teach them to draw. We are also facilitators and mentors who can point out a direction for them.”

One of his favourite sayings is American animation mogul Walt Disney’s belief that “if you can dream it, you can do it”. Siang Yu views his work as helping students learn how to dream their own distinctive dreams.

“In this programme, we want them to develop their personal identity, and find their own passion,” he says. “We place a lot of stress on creativity and coming up with ideas. It is important to develop craft, but without your own ideas, you will be providing a service to someone with the ideas. If you are the one with the ideas, you will be the one providing the jobs.”

Siang Yu has spent the bulk of his career at Hwa Chong Institution, and its predecessor, The Chinese High School. “My key passion is mingling and working with students,” he says. “This school has a certain heritage as many pioneer artists taught here, and it has provided me with a supportive environment where I can do what I want in terms of teaching and still pursue my own projects along the way.”

Besides winning several awards for his short films, Siang Yu also helped to conceptualise and shoot a music video in 2012, which also garnered praise from Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, who lauded the work on his Facebook page. Siang Yu made the music video, titled I Still Love You, together with his former students and friends, and it was intended as a love song to Singapore.

He has developed a few feature-length scripts and looks forward to producing a feature film if the right opportunities come along.

In the meantime, he says he will continue to seek inspiration

from everyday life, as well as filmmakers he admires, like Taiwaneseborn director Lee Ang and home-grown talents Anthony Chen and Royston Tan.

“Ultimately, I am a storyteller,” he says.

Since he is usually working with a shoestring budget, family, friends and students appear repeatedly in his films, and he can see them growing up on screen if he views all his shorts chronologically.

“Filmmaking is definitely a team effort and I am thankful for everyone who has joined me in these projects.”

We place a lot of stress on creativity and coming up with ideas. It is important to develop craft, but without your own ideas, you will be providing a service to someone with the ideas. If you are the one with the ideas, you will be the one providing the jobs.”

Dawn Kuah

Dazhong Primary School’s Subject Head for Aesthetics Dawn Kuah does not hesitate to describe herself as a bubbly teacher, and that has everything to do with how much she adores her job.

“In class, I’m always very happy and joyful,” she says.

“I became an arts educator because I discovered at a young age the value of the arts in my daily life. The act of creating art and composing music helped me to create my own identity.”

Indeed, Dawn took great pleasure in both art and music as a child, and found

her way back to the arts as a music teacher after a long detour in the sciences.

She is actually trained in Polymer Technology and worked as a chemist for four years before becoming a primary school teacher, teaching mainly Science.

But even then, “something was still missing,” she says.

After talking things over with her mother, who is also a teacher, Dawn decided it was finally time to “go with my heart” and start teaching music as well.

A key mentor for her as she began this new path at Radin Mas Primary School was its then-Principal, Mrs Jenny Yeo, who is known by the very joyful moniker, “the singing Principal”, due to her penchant for breaking into song during school assembly.

“She opened my eyes and mind, and her wonderful and kind words are the reason I am here today,” she says.

“She told me that the arts are very special, and not everybody can do what I am doing. So if I have the talent, I must share it and inspire my students.”

She proudly shares a text message from a former Radin Mas Primary School student who has a gift for singing. Dawn had encouraged her to keep pursuing her love for music after discovering the girl’s talent during an audition.

The student went on to join the choir in both primary and secondary school, and is now pursuing opera and vocal studies in the United Kingdom.

The student had sent Dawn a text message to wish her a happy birthday, writing: “You are the one who discovered my musical talent and paved the way for me to do so many things.”

Dawn is visibly moved as she reads these heartfelt words of thanks. For a teacher, “receiving just one message like this is enough,” she says. “I really want to see them succeed, and I believe that they can do it.”

Unsurprisingly, this joyful teacher is also a very joyful student. In 2011, Dawn decided to begin a master’s degree in music education at the National Institute of Education (NIE), completing the course on a part-time basis over three years as she continued to juggle work and family.

“It was very tough,” says the mother of three.

“But I wanted to level up my knowledge, and push myself further since I was leading the department, and professional development and continuous learning are important. I really enjoyed myself. I love challenges.”

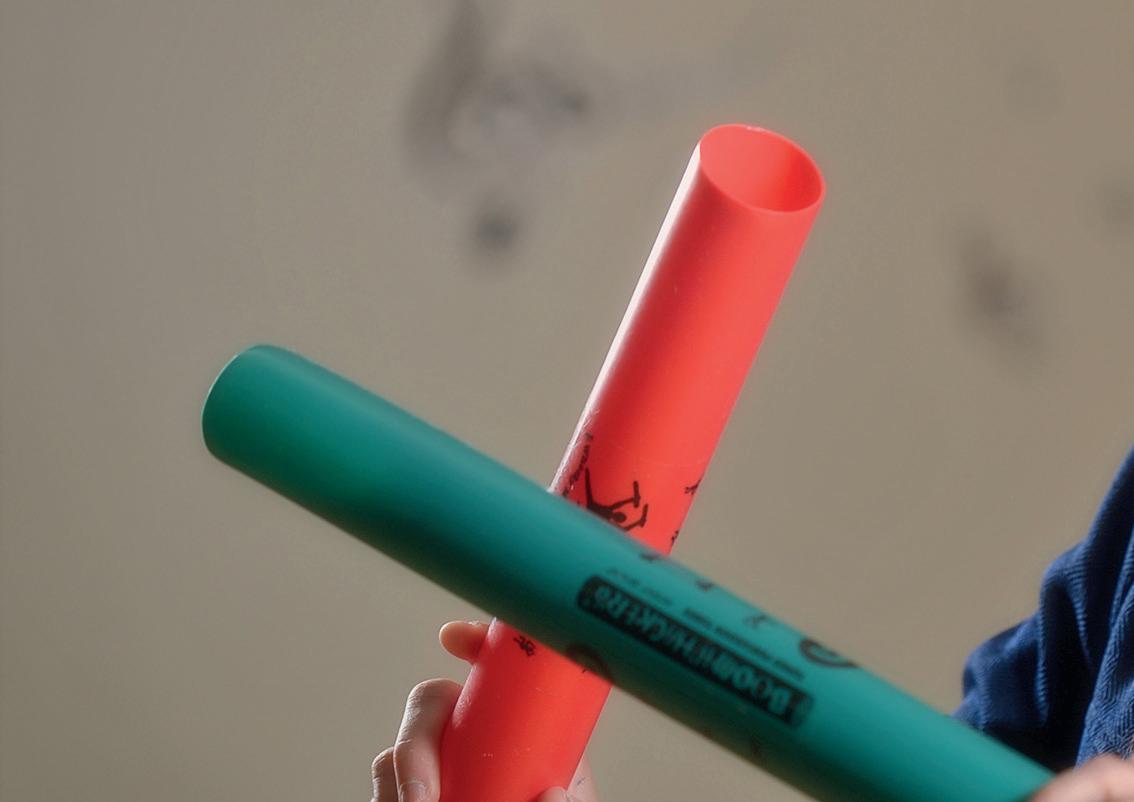

One of the most memorable experiences during this time occurred when she took a module on Informal Learning. The lecturer brought the class of five to a band room, and instructed them each to pick an instrument that they had never played before. Their assignment – to figure out how to perform as a team to an audience within just two days.

“That was really throwing us in the deep end. It was a wonderful yet challenging learning experience,” Dawn recalls. And it was also exhilarating, especially when they pulled it off.

“I thought I couldn’t do it, but we worked it out as a team and persevered. Music can really bring people together.”

Her master’s degree course experience has prompted more reflection, especially after she switched to specialised music teaching three years ago. “I want to guide my music and art teachers to reflect on their practices. Now that I have more knowledge, I also want to test these theories in class, and see how the students learn and gain their musical knowledge and skills,” Dawn shares.

As a Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR) Champion, she hopes to help motivate more arts educators, who can in turn teach and inspire more students.

Dawn has taught students with special needs, and she finds that their engagement and concentration can show significant improvement during art and music classes, especially if the lessons are attuned to their sensitivities.

In a 2012 research project, her findings seemed to suggest that students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and dyslexia might respond better to lower-tone sounds. “They don’t like high-pitched metal instruments like bells and the triangle,” she says.

She turned this insight into a mood creation exercise using unpitched percussion instruments like wood blocks and castanets. These produce timbres that don’t cause distress for students with special needs and which they can use to communicate their emotions.

When she works with students who require learning support, she uses music to encourage inclusion. These students struggle with their core subjects and some among them have special needs. Music lessons allow all students to interact and learn together through various activities, and Dawn makes sure to group the class in a way that ensures students are able to interact in music-making and learn from one another.

“Music is a vehicle for expressing emotions, so there is never failure in the class,” she believes. “Even if they can’t perform the rhythms or movements accurately, they still get the idea and can feel more confident. Self-confidence is very important, and good teamwork helps create that as well.”

She is also very interested in connecting art and music. One idea she came up with in 2013 was the Music Rhapsody Programme, which used classical music as a tool for students to think about their emotions. “I asked them to draw whatever came into their minds when they heard a piece of music. It’s

about being creative and expressing yourself, and also a way for me to see what’s happening in their lives,” she says.

The music of Mozart prompted some particularly happy drawings, Dawn recalls. “I asked them to stand in front of the class and articulate what they were trying to express by describing and narrating. I wanted to teach the students that they are free to imagine, be creative and just let the ideas flow.”

Dawn values how arts education helps students develop communication, teamwork, leadership and time management skills. These, in turn, impact the students’ attitude towards learning and motivate them further in the pursuit of learning.

“I believe that the arts can help harbour a sense of value and build a sense of accomplishment. The arts help to foster students’ sense of identity and develop their individual voices. These are why I believe arts education needs to be an integral part of my students’ holistic education.”

I really want to see them succeed, and I believe that they can do it.”

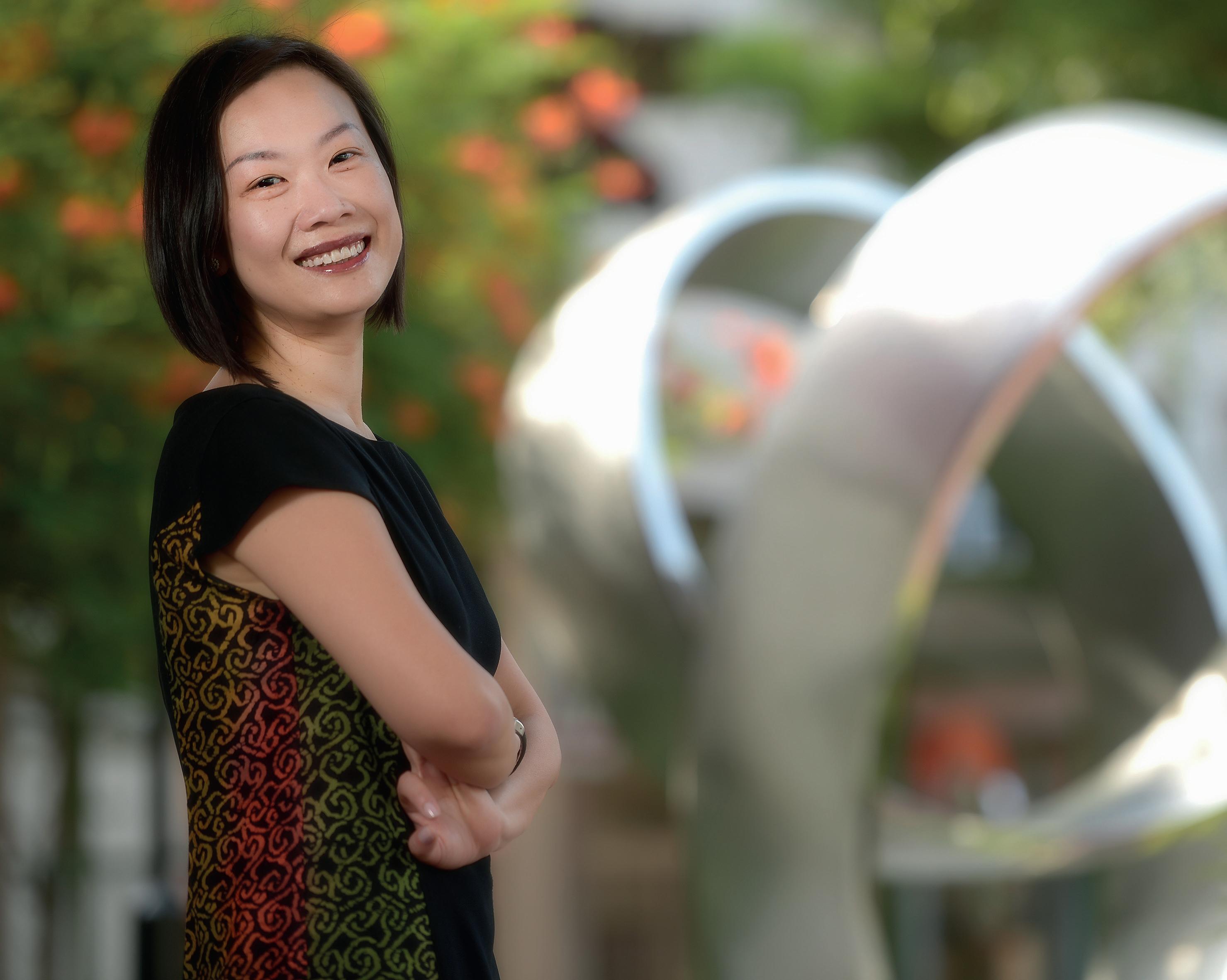

Clara Lim-Tan

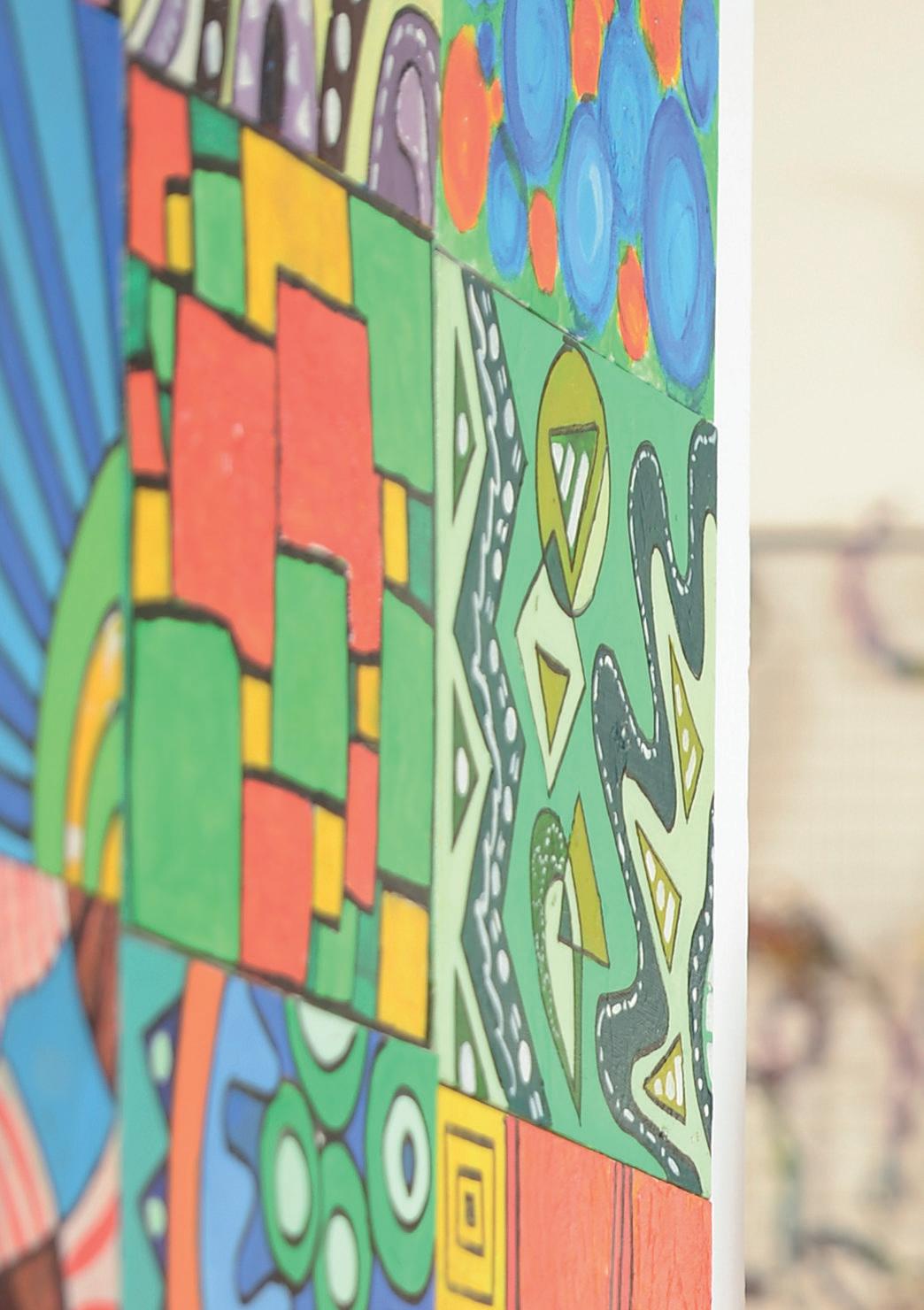

First-time visitors to Yu Neng Primary School will probably find their eyes drawn to a striking stainless steel sculpture by Singapore master artist Sun Yu-li near the school entrance. The abstract silver swirls of the sculpture, titled With All My Heart, resemble the shape of a heart if viewed from a certain angle. But walk around this sculpture and the same swirls seem to curve into ‘YN’, the initials of the school, or the loops of the infinity symbol or even the shape of a pretzel.

This piece of art was installed as part of a collaborative project between the Yu Neng Primary School Alumni Association and The RICE Company Limited to

commemorate the school’s 80th anniversary in 2015. Its shapeshifting ability illustrates a tenet that Principal and former music teacher Clara Lim-Tan holds dear – the importance of exploring different perspectives.

The pianist credits collaboration with artists of other disciplines for helping her understand how seeing things from different points of view better serves the bigger picture. In 2006, for instance, Clara collaborated with filmmaker Royston Tan and dancers Ix Wong and Joey Chua in a performance called Background Foreground Playground, a multi-disciplinary performance where the role of each artist shifted in relation to the others sharing the stage.

“Sometimes I was the one in the spotlight, sometimes I provided piano accompaniment for the dancers and sometimes, a film recording of me playing the piano appeared on the projection screen as I sat at the piano in darkness,” Clara recalls.

“You can’t be insular as a musician. It is important to have an interest in and develop understanding of the other art forms. I find that interplay and the process of joining the dots very intriguing. You never know what possibilities open up.”

This conviction that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts continues to drive her work as a school leader. When she first joined Yu Neng Primary School in 2014, for instance, she learnt that the school was going to be celebrating its 80th anniversary in 2015 and saw that as a great opportunity to bring different pieces of its history together into a coherent whole and build school pride and culture. She also saw the need to involve stakeholders – past, present and future – in coming together to co-write the next chapter of the school’s history.

That’s why the school’s students, staff and alumni were invited to create art pieces that represented personal stories, aspirations and memories of the school. Mr Sun then re-created

80 of these as brass jigsaw pieces, which now form the YN80 Art Legacy Wall that flanks the school entrance along with his sculpture. The year-long YN80 celebrations also helped to raise funds for the school improvement fund, which enabled the design and installation of an interactive heritage gallery that showcases the school’s history alongside that of the Bedok community.

Clara is known for leveraging the arts in diverse ways to excite and engage students. “It is imperative that we provide all our students with opportunities and platforms to experience and engage in the arts, regardless of their backgrounds and starting points,” she believes.

As an arts educator and school leader catering to different profiles of students in both primary and secondary schools, she has initiated an Arts Passport scheme to connect students to various Singapore arts groups, and attached students as docents at the Singapore Art Museum. “As a school, our resources and expertise may be limited, so it is essential to tap on the rich resources beyond the school and connect with the arts industry and the community to bring in new learning experiences for our students,” she says.

Indeed, such experiences can become indelible parts of their school years. Clara recalls the exhilaration of working with students, staff and parent volunteers, during her time as Principal of CHIJ (Kellock) from 2008 to 2013, to stage an original musical that featured a theme song specially written by Cultural Medallion recipient Iskandar Ismail. “That song is still sung by the students and staff today, and the sense of pride and ownership continues to remain in the hearts of those involved in the production,” she says.

More recently, Yu Neng Primary School collaborated

with a local bank on a project that saw students working with professional designers to create an app that could ‘teach’ their peers financial literacy concepts through game play. The school has an Applied Learning Programme in Information and Communications Technology and offers coding as part of its curriculum. Even in this highly technical field, Clara points out, the arts still plays a role — in conceptualisation, storyboarding and game design.

By weaving the arts into the fabric of their school experiences, she hopes to help her students build up their selfesteem and sense of empathy, and develop communication and problem-solving skills. She also hopes that this exposure will encourage them to continue engaging with the arts as they become young adults. “The arts can change mindsets. I hope when parents see their children transform, they will be convinced that it opens doors and transforms lives.”

The arts have certainly transformed her life and opened doors, and she credits her parents for this. They had an inkling of her aptitude for music when she kept tinkling a toy piano as a child, and even though her book-keeper dad was the sole breadwinner, they started her on piano lessons around the age of five. She went on to the Music Elective Programme at Methodist Girls’ School and Raffles Junior College, and later took a government scholarship to study music at King’s College London in the United Kingdom. That plane ride to university was her first time travelling abroad.

“My whole experience in the United Kingdom was lifeshaping on so many counts. There was the exhilaration of being in the capital of the arts, working with other musicians and artists in other disciplines. I built up confidence and independence

and took up things I thought I would never be able to,” she says. “Without all of that, my trajectory would have been quite different.” She later went on to do her Master of Philosophy in School Development at the University of Cambridge.

She also credits her former school leaders and bosses for believing in her and providing her with the opportunities to lead and innovate. That trust and support meant a lot to her as a young teacher, and has shaped the way she works with her staff.

“These things matter a lot to me. As a school leader, educator and musician, I feel that it’s very important that our children – the leaders of the future – have access to a quality arts education in every school. We must not only provide them with platforms and opportunities to dream, explore, experiment and create, but also with a safe and supportive environment in which to take risks.”

One of her favourite quotes is from Michelangelo: “Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.” She says: “If we link that back to what we do as educators, it’s about discovering potential. Every child is talented. Our role in chipping away at that block is simply to recognise the talent and potential in every child.”

Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.... Our role in chipping away at that block is simply to recognise the talent and potential in every child.”

Ceramics is an elemental art, shaped by the meeting of earth, water, air and fire. For Ang Mo Kio Secondary School Lead Teacher for Visual Arts and ceramist Ng Siew Kuan, it is also a practice tempered by the passage of time. She likes to play with the element of temporality in her work, letting its unpredictability and idiosyncrasy shape her pieces.

Siew Kuan has made clay structures conceived to cave in at their weakest point; bone-dry cups that might well crumble as you drink from them; and an installation of suspended extruded clay rods that would drop and shatter on the

ground according to the varying speeds at which they dried out.

Her interest in stretching the boundaries of ceramic art can be traced back to a pivotal period spent in California in the United States. She became interested in ceramics while a student at the National Institute of Education, and subsequently mastered different throwing, firing and glazing techniques.

In 1991, after years of teaching, she took study leave to pursue a degree in fine art at the California College of Arts & Crafts (now known as California College of the Arts) in the United States. The area was a hotbed of avant-garde progressive conceptual art, and she experienced a culture shock that sparked an artistic awakening.

“I was quite proficient in throwing. But while the school gave me strong credit for my competence, they didn’t consider pottery an art. They considered it a craft,” she recalls. This attitude “challenged me to think conceptually”, she says.

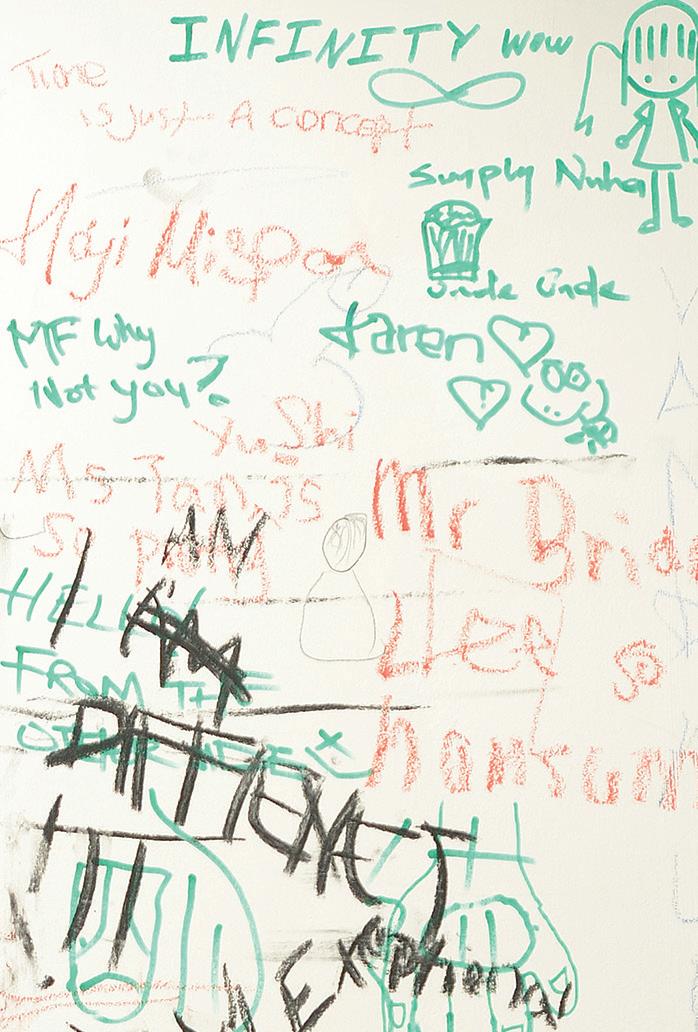

Her first breakthrough came when she created an installation piece called Here I Sit For Hours And Hours, for which she sank a glass trough into a chair placed behind the potter’s wheel, and then filled the trough with slurry. Some of the slurry was also flung onto the surrounding paper-covered walls.

She also experimented with pieces of varied scales and forms, as well as different techniques and materials. “One of the things people say when they go overseas is that they are forced to look inwards. You have to dig deeper to find out who you are,” she says. “If I had not gone into a different world, I would not have been bold enough to transcend my parameters.”

These experiences enriched Siew Kuan’s teaching as well. Upon returning to Singapore, she was posted to The Chinese High School (now Hwa Chong Institution) to teach the Art Elective

Programme (AEP). “My time away had changed my outlook. I wanted to expose my students to that kind of thinking as well,” she says. “Students come into AEP because they are interested in art, so you can push them and take the critical discourse to a higher level.”

Her involvement in the art world also inspired her students. In 1995, she collaborated with fellow ceramist Jason Lim to stage performance piece Three Tonnes of Clay at The Substation. They filled the entire gallery with unfired clay, moulding it differently every day to transform the space. Some of her students were among the visitors. “It was an example of art that was not the norm, and they found it different and refreshing,” she says. She believes she influenced her students to become the first batch to put up installation art as an O Level genre.

In 1994, she also collaborated with performance artist Amanda Heng for an installation at Fort Canning. This piece was part of an immersive arts experience by TheatreWorks titled Longing, which saw visitors taking different routes to various performance sites within Fort Canning Park.

Inspired by this, she experimented with a similar sitespecific multi-sensorial approach for several editions of the Night of Music and Dance (NOMAD) arts showcase at Ang Mo Kio Secondary School. These events feature visual art and performances with strong student input.

NOMAD is a whole-school effort that takes over a year to prepare, and students often collaborate with professional artists to workshop ideas. The 2005 edition, for example, drew on the talents of creative director Jeremiah Choy, choreographer Gani Abdul Karim, drama instructor Norlinah Mohamad, and visual artists Ulrich Lau and Justin Lee, to mention a few. In 2010, students got to work with artist Cheo Chai-Hiang to come up with their NOMAD project.

“We start preparing from Day 1 of Term 1,” says Siew Kuan. “The teachers instruct and facilitate the process of interpreting the theme, formulating ideas, and they give different kinds of stimulus to elicit the students’ views. It’s a very organic process, as we work, we tweak.”

She describes the finale of the inaugural NOMAD in 2005 as one of the most memorable moments of her teaching career. “There were a lot of artists involved, the energy level was very high and it was very stirring.”

After a decade, NOMAD has also become a signature school event cherished by the students. Siew Kuan recalls an alumni gathering where a recent graduate stood up when talk turned to the possibility of scaling down the event, and said: “You cannot take away NOMAD.” She believes he did so because he had benefited from the NOMAD experience. “It had given him an outlet to express himself and develop that ability to speak in front of people and fight for a cause.”

Siew Kuan has continued to explore the theme of temporality and its unpredictability in her practice and the classroom.

As a member of a group of clay artists who practise at Thow Kwang Pottery Jungle in Jurong, she was involved in the campaign to revive the pottery’s iconic dragon kiln, an elongated brick kiln that creates variable results during wood-firing due to the way the flames and ashes react with the clay.

In the classroom, unpredictability has emerged as a dominant theme in recent years. “Art is a thinking subject. That’s why even after teaching for 25 years, I don’t get tired, because no two responses to the same question are ever alike,” she says. “Previously, we do more demonstrations to show students how to paint, how to use proportions and space. Now, the course work is

very thematic, and we go from thinking to making. It’s up to the students to interpret the theme, and we tease out their thinking by facilitating and asking questions. It’s more open-ended, and sometimes I do find students quite at a loss because there is no one correct answer, just possibilities.”

That sense of possibility is the key to art and to life, she believes. “Ultimately, what they are thinking about is, what is the stand I want to make? They have to take a risk and justify their stand with the materials and research to back them up, and with resourcefulness and articulation. That is a 21st century skill.”

Ultimately, what they are thinking about is, what is the stand I want to make? They have to take a risk and justify their stand with the materials and research to back them up, and with resourcefulness and articulation. That is a 21st century skill.”

She’s now Nanyang Junior College’s Subject Head for the Art Elective Programme (AEP), but when she was a student herself, Hew Soo Hun enrolled in the AEP simply because she thought it would be fun to sit for the selection test with her friends. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do as a 12-year-old,” she recalls.

Once she had settled into AEP at Nanyang Girls’ High School, she found herself enjoying the experience, not least because of her art-loving friends, and good teachers like Mr David Cumming.

“He was a ceramist and we marvelled at how good he was at handling clay,

and thought perhaps one day we could be like him,” she recalls.

They also looked forward to his assignments, which constantly challenged them creatively. Tasked with recreating the works of masters like Monet or Cézanne, in the pre-Internet age, they scrutinised the reproductions of these works in the school library’s reference books. They could not loan the books out, had no smartphones to take photos of the pages, and could only make black-and-white photocopies of the images and make meticulous annotations to help them remember which colours went where.

“We really had to analyse the work, and figure out how to mix the paint to create a certain effect, or how to produce the intensity of this colour. And we were not even using acrylic paints, but poster colours,” says Soo Hun. “To emulate these painters, we had to understand the brushwork and the palette. We were really excited by the exercises and would stay up all night to do them.”

When Soo Hun went to Goldsmiths College, University of London in the United Kingdom to study painting, however, she discovered a different aspect to art education. “In Singapore back then, art education focused on skills. Your work had to look nice compositionally, and you had to make it well whichever medium you chose,” she says. But in London, the ideas underpinning the artwork, and the ability to articulate these ideas well, were extremely valued. “I had to grapple with the question: what more is there to art besides the skills? There was a period when I felt very lost and confused, but after two years, things became clearer.”

Art education in Singapore has since evolved and Soo Hun views helping her students to build the skills for articulating their ideas as an important part of her job. “We need to challenge them to think, to be critical, and to talk about their art,” she says.

To facilitate that, she makes sure that students receive feedback from fellow students as well as teachers. For instance, she builds regular critique sessions into the curriculum for Nanyang JC’s AEP, which gets students into the habit of articulating their ideas to others and clarifying their own thinking after receiving feedback. “It’s always interesting to hear how other people perceive your work, and the more art you see, the more ways you can approach looking at a piece of work.”

The soft-spoken Soo Hun says her early years as a secondary school teacher were not easy. Once, she burst into tears during a class because the students were simply not paying attention to her and being very mischievous. “Everyone became very quiet and one boy ran out of the classroom,” says Soo Hun, who recalls getting even more upset that he left without her permission. “Then he returned carrying this huge bundle of toilet paper and offered it to me to wipe my tears,” she says, laughing. “So I couldn’t stay angry after that.”

She grew to enjoy getting to know her students. “Being in a secondary school was very good training. I learned how to manage a large class, and handle different types of students.”