SPRING 2023

ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLU SIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASH ION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILL USIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLU SIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FAS HION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION IL LUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLU SIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASH ION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION ILLUSIONS OF FASHION

Cover shoots: Claire Yubin Oh (photographer), Hsiao Hsuan Charlotte Jin (direction), Simon Kogutt, Prajwal Trivedi

Editor-in-chief : Sarina Seth

Production executives : Maahika Singh, Anouk Bethany Richards

Contributors: Maria Valentina Bezzi, Ademi Nwadike Maahika Singh, Tom Holmes, Chiara Wolter, Imrana Pirbay, Sarah Mokhtari, Addington Willimams, Offa Sinfrey, Hsiao Hsuan (Charlotte) Jin, Tatiana Gaglowicz, Lola Caputo

3 24 06 12 18 22 A love letter to MODO One Size Fits All Toms Trunks Disclaimer: this photo has been digitally altered Between History and Assertiveness These aren’t Boobs! Soul and Elements Negative Illusions Parasite 04 06 12 16 18 22 24 30 32 CONTENTS 32

A letterlove TO MODO

by Maria Valentina Bezzi

Having written for MODO since its first print edition, I have seen this society grow a fair bit. As a celebration of this growth, and a thank you for everything MODO has done for me (and many others!) over the years, here is a love letter to the creatives and the daredevils, the alchemists and the believers, those who were, and those who will be.

Dear UCL MODO Fashion Society,

I have enjoyed telling the story of how I wound up on the magazine team for the past two years. I love to highlight the randomness of it all: walking into the Bloomsbury Hotel Cafe almost by mistake, a glaring example of what people often refer to as a ‘sliding doors’ moment. Had I not seen the Instagram post pop up on my feed on my way home from UCL’s main campus on a (surprisingly) sunny October day in 2021, and had I not thought, “well, I’m here now, might as well give it a go,” I would have never learnt about this incredible society.

Walking into the hotel’s cafe, my mind crowded with memories of dressing up in my mom’s oversized shoes and wearing my dad’s ties when they would reach my knees as a little girl, I distinctly remember wondering, “why in the world did I not think of this before?” The people, the energy — the electricity — in what was a simple cafe get-together to plan the magazine’s January 2022 Edition immediately convinced me that this would be a project I was eager to partake in. A month later, I became an editor executive, and six months later, I was honoured to see the UCL Students’ Union webpage announcing me as the society’s new Vice President. Now, over a year and a half after that

4

sunny October afternoon, I can confirm that walking into that cafe has been the best mistake I have ever made.

Fashion has a reputation for the dreadful role it plays in polluting our planet, its unhealthy obsession with fixed (and often unattainable) beauty standards and, of course, its glaring snobbiness. But fashion is so much more than that: in my past articles for the MODO Magazine, I have sought to showcase a different side of this industry each time. From sustainability initiatives across the luxury industry, to the crucial role played by fashion in the liberation of social norms throughout the late 20th century, and the role of new technologies in democratising fashion, a new generation of designers and artists is rising from the pitfalls created by current fashion houses in the pursuit of a fairer world. And MODO Members are, and will forever be, at the forefront of these developments.

Fashion’s biggest illusion — one perpetrated by the media, more often than not — is that of its meanness, its unwavering bitterness and a repulsion for ethics and kindness. And certainly, this is the case for an unsettling amount of retailers. But fashion is so much more than that: it is the most intimate form of art, which we plaster on our bodies and exhibit for the world to see day in and day out. Fashion is a banner, a flag, a testament to our unique experiences and worldview. Fashion is a tailored uniform and a pair of ripped shorts; a sleek pair of flats and daring high heels. We are fashion, and fashion is us: an immovable part of our identity as human beings. Crucially, fashion is, and historically has been, a powerful tool for campaigning, a symbol of unity, a shared roadmap towards a common goal. Young designers seeking to make the industry kinder, fairer and more accessible must not be lost in the noise. You are seen. You are valued. And you are what makes this industry as amazing as it is.

The people I have met and the experiences I have lived thanks to this society are unlike

anything I could have ever dreamed of when starting my Law degree at UCL. Despite my unfaltering love for my course, the spark of creativity, pride and joy provided by each runway show, each magazine edition, each photoshoot, and every single social we have taken part in together is something I can only wish for every- one I meet: seek out the experiences which set your heart on fire and keep your eyes fixed, watering, glowing with admiration for your work and your team. This society has provided plenty for me, that much I can tell you.

With everlasting love, keep being you.

5

by Ademi Nwadike Photographer : Vittoria Avigliano

by Ademi Nwadike Photographer : Vittoria Avigliano

7

The body positivity movement, dating back to the ‘Fat Acceptance’ movement of the 1960s, gained immense virality in its third wave, starting around 2012. Now, #bodypositivity has been used over 13 million times on Instagram, and body positivity has visibly entered the fashion industry, with plus-size models like Precious Lee and Paloma Elsesser nearing supermodel status, Victoria’s Secret’s inclusivity-inspired rebrand, and fashion houses extending their size ranges, making fashion more accessible. However, critics worry that the steady rise of Y2K fashion and the idolisation of the 90’s ‘heroin-chic’ aesthetic slips fashion back into unprogressive times. Arguably, the fashion industry never discarded those ideals, with the perceived ‘regression to size zero’ having stealthily underlay the industry for years.

Fashion’s curated illusion of acceptance belies its reality as a closed-minded industry. Inclusivity seems to not be the future of the fashion industry, but rather, the current, most profitable trend. How can we distinguish between genuine inclusivity and tokenistic virtue signaling? Lizzo, who is heralded as a body-positive role model for simply existing in a bigger body, is draped in stunning bespoke Louis Vuitton for red carpets, while their Pre-Fall 2023 collection is restricted. The fashion industry has also turned its back on plus-size models. Chanel was praised heavily in 2020 for casting Jill Kortleve as their second ever plus-size model since 1910, but the Vogue Business A/W 2023 size inclusivity report revealed just 0.6% of 10,000 looks across over 200 shows during the A/W 2023 season were presented by plussize models. Chanel has 0 plus-size models and is

still considered to be one of the most inclusive in the industry. Many of these brands flaunt inclusivity on social media or with tactical PR moves but it is clear, unfortunately, that thinness remains the standard.

The valorisation of smaller bodies has always been most evident in sizing. The one-size-fits- all epidemic infamously restarted in the new millennium with the introduction of Brandy Melville, a popular women’s fashion store, in which most of their product range discards ‘standard’ sizing in favor of one size - an ‘average’ UK size 6. The average UK woman is a size 16, for reference. The exclusivity in size range sends a resounding message, stating that different bodies are unwelcome to partake in trends and popular fashion. This shoot therefore showcases ‘unflattering’ silhouettes, clothes worn in ways they aren’t supposed to be, and styling to allow the body to be the center of focus - not the clothes. The styling focuses on adjustments used as clothes - belts, ties, ribbons and pins feature as the main pieces. The fashion industry has almost successfully deceived us into believing that fashion is in its ‘inclusive and progressive era’ without accountability for the persistent exclusivity of non-straight-sized bodies or tangible change. The exclusion of bigger bodies in fashion is historically a complex issue that transcends measurements.

It is evident, however, that we as a society have moved beyond these restrictions that the fashion industry has placed on us. Bodies are not designed to fit the clothes, clothes are designed to fit the body, and high fashion and style truly have no ‘one size.’

8

Ademi Nwadike considers how we can challenge the illusions and lies fed to us by the fashion industry; focusing on ‘unflattering’ silhouettes and distorting styling conventions, Nwadike sends a powerful message of inclusivity showing that fashion has no size, no colour and no ‘right’ way.

10

Creative Director & Stylist : Ademi Nwadike

Models : Sara Ekutudo, Leene Elleithi, Matilda Siri, Alexa Wong, Lola Caputo, Jenan

by Maahika Singh and Tom Holmes

by Maahika Singh and Tom Holmes

TOM’S illusions of the industry

TRUNKS

Tom’s Trunks is an apparel company that creates loungewear that looks and feels fantastic whilst lasting a lifetime. It encapsulates a positive shift in fashion toward building a more sustainable, ethical, and inclusive sector. Interviewing Tom Holmes, founder of Toms Trunks, Maahika Singh provides insight into Tom’s journey, navigating the worlds of commerce and clothing as well as the many illusions of the industry he’s broken into.

Tom’s inspiration for his products “stemmed from the beautiful colours found on the coast of East Africa” and “the Kikoy, a handwoven striped cotton textile, originally used by tradesmen travelling long distance.” Not only was he taken by the fabric but also its comfort; since discovering it in 2014, he has been wearing them constantly. Realising that “there is a gap in the market for great loungewear” Tom decided to introduce these gorgeous garments to the UK and emerging desigers, giving way to “Tom Trunks”.

When discussing the theme of the magazine, Tom commented: “let’s be honest, there are many illusions about the fashion industry. I am still learning about them every day [...] when I started the brand aged 14, I did not know a lot [about the industry].” Despite the flexibility and autonomy of entrepreneurship and starting your own businesses is often glamorised, Tom emphasised the challenges of starting up so young as his age was sometimes a “barrier”. Being “too young” to be a CEO presented hurdles. Practical ones such as not being able to own a PayPal account or register a company house and other social ones. For instance, when negotiating with suppliers, Tom confessed he was not taken seriously as most people saw him as “too young to do business” and many felt they could take advantage.

Despite these challenges, Tom continued pursuing his mission to make comfortable clothing that also gives back to the community and the planet by donating 10% of profits to charities like People & Planet and Tom’s Trust. Putting sustainability at the forefront of all its endeavours, Tom’s Trunks also ensures that its production is environmentally sustainable, banning single-use plastics from all operations. By focusing on sustainable consumption and production, Tom’s Trunks commits to its “endeavours to empower young people” and stand up for whats right.

Ten years after its conception, Tom is unwaveringly committed to his beginnings. Reminiscing on the brand’s growth, Tom recalls his naïvety as a blessing, as well as a curse, as it allowed him to trust people and maintain a much needed curiosity in everything. Maintaining these two qualities allowed him to grow. Tom’s journey is one that highlights the realities of starting a brand at a young age, countering the commercial illusion of “overnight success” that social media has created. Tom says the jounrey, albeit difficult, was completely worth it: “it has allowed me to expand and explore a different world outside of education”.

14

15

Models : Maahika Singh, Sara Etukudo, Lucas Duncan, Rosie Holloway, Kemal Yigit

by Chiara Wolter

16

DIGITALLY THIS

DIGITALLY ALTERED

THIS PHOTO HAS BEEN

PHOTO HAS BEEN DIGITALLY ALTERED

Digitally altered images are everywhere. You can find them when you pass a newspaper stand, a billboard, when you turn on the TV or when you enter your nearby clothing store. With the rise of social media and various apps that allow anyone to easily alter their photos themselves, our exposure to digitally altered images has become perpetual. The beauty standard is no longer only created by magazine editors or major fashion labels; but instead every individual contributes to and warps the standard by each edited picture of themselves that they upload.

The negative consequences are significant. Studies have found that low self-esteem, anxiety, eating disorders and/or disordered eating patterns and an overall decrease in well-being can all––at least partly–– be linked to consuming digitally altered advertisements and images online. Such findings should not be taken to mean that all social media and altered photographs are the root of all such mental health issues. However, the connection between growing up with––and constantly living on––a diet of photoshopped media and the consequent effects on mental health cannot be ignored. In light of such worrying findings, it’s natural to wonder about what has been done to counteract these consequences?

How are users being protected against misleading and potentially harmful content? Sadly, the answer to this question yields a more or less unsatisfactory answer, particularly dependent on the country within which you reside. In some countries, laws have been passed that require certain edited images to be marked by a disclaimer. France, for instance, requires images that have been edited to “make a model’s silhouette ‘narrower or wider’’ to be marked with the disclaimer: “photographie retouchée’’ (or ‘edited photograph’). In a different approach, other countries such as the UK or Ireland rely on the industry itself to introduce regulations. This usually happens through Advertising Standards Authorities (ASA) which, in the case of the UK, cooperate with the Committee of Advertising Practice to draw up Advertising Codes. Based on this code, the ASA can condemn advertisements that ‘’are considered likely to encourage or condone harmful behaviours or attitudes related to body image’’.

However, this in no way means that all retouched photos are banned or must contain a disclaimer. Despite the lack of consensus on regulation, positive

developments have been coming to light over the past few years. In the UK in 2020, a motion was put forth to bring in a Bill regarding the requirement of a disclaimer on digitally altered images. If this Bill were to become a Statute, the UK would join the likes of countries like France, which uphold stricter regulations for digital manipulation.

While such advances signal a good direction, I believe that far more should be done because a simple disclaimer just does not feel sufficient. Studies have shown that disclaimers only have a slight impact, if any, on the way in which consumers negatively interact with the media and consequently think about themselves. One study with French women found that despite knowing images had been manipulated, the women still considered them to be ‘realistic’.

Given the consequences of high consumption of digitally-manipulated images, stronger legislative and regulatory changes must be prioritised. We must move away from simplistic solutions focused on disclaimers––that not only have little impact on reducing negative effects but altogether draw more attention to beauty standards–– and move towards more restrictive measures.

17

ALTERED

THIS PHOTO HAS BEEN DIGITALLY ALTERED THIS PHOTO HAS BEEN

DIGITALLY

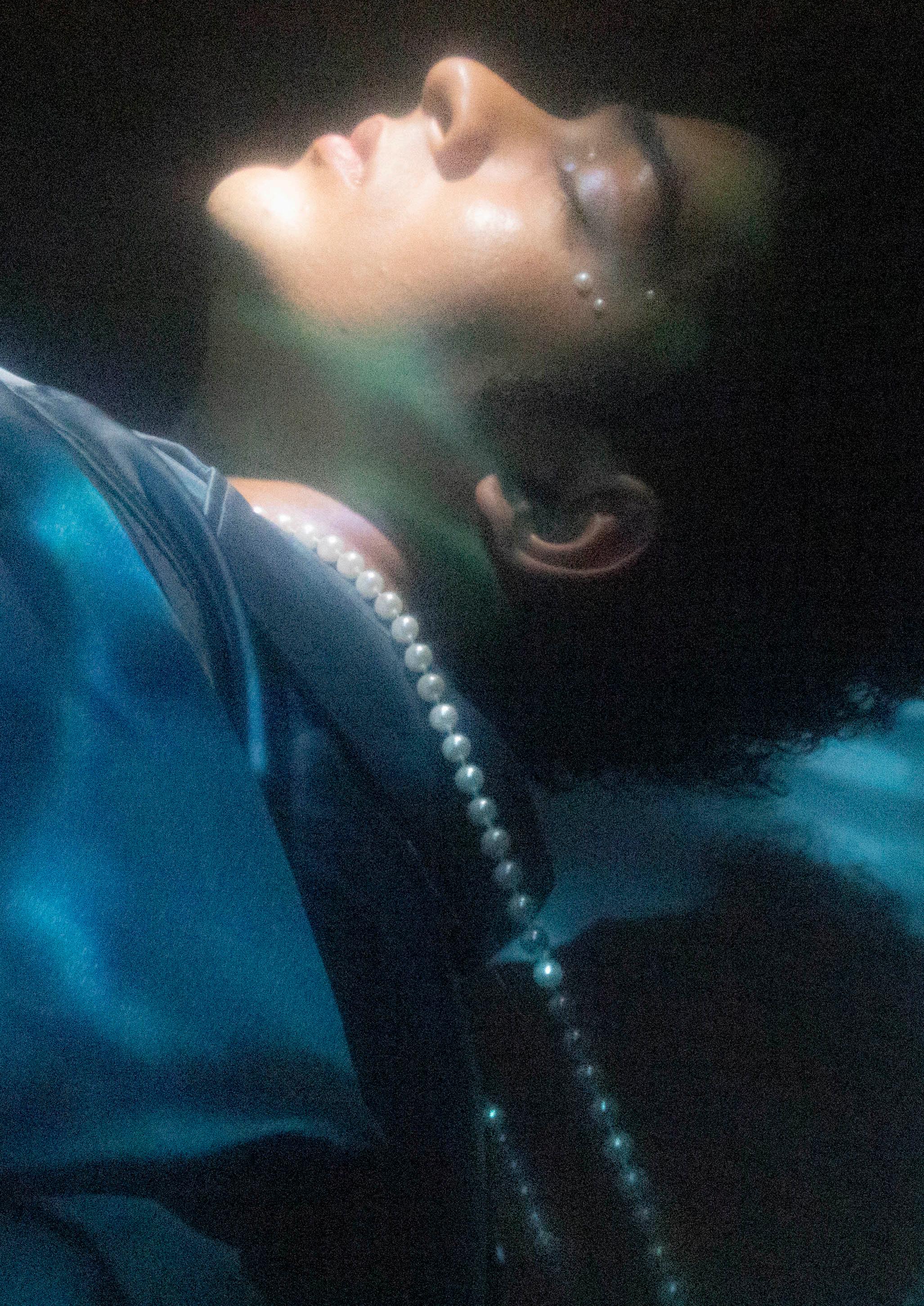

Through her clothes, Sarina Seth celebrates diversity and embraces fashion as a symbol of freedom. The seamless blends between the exotic allure of Indian garments and the vibrant backdrop of London city create a captivating tapestry that fuses cultural richness with cosmopolitan energy.

by Imrana Pirbay and Sarah Mokhtari

by Imrana Pirbay and Sarah Mokhtari

Photographer: Songju Kang

Photographer: Songju Kang

Fashion trends can significantly affect consumer behaviour, shopping decisions and sense of style. This is because trends and styles are often presented as aspirational or desirable, encouraging consumers to emulate the looks of the latest trendsetters or influencers. This raises significant issues regarding the connections between consumerism, identity, and fashion. Is the urge to wear the newest trends primarily motivated by a desire to adhere to social and cultural conventions, or is it more motivated by a real expression of

one’s own taste and sense of style?

During the 18th century a new type of fashion emerged in the United Kingdom: the Macaronis. Macaroni fashion highly contributed to the social and political history of England in the 1700s, as it became a way of expressing satire through fashion. People were not only expressing themselves, but conveying strong political messages for the time through their style. In Smollett’s Roderick Random (1748) Captain Whiffle wears a pink-coloured silk lined coat and white satin waistcoat embroi

dered with gold at the heart of his breast. At a time where men wore darker clothing for their everyday routines, this concept reinvented conventional dressing. Today, we are all redefining our own “fashion norms”. Conventionality is rethought and new perceptions are considered. Our idea is to bring back that notion of “Macaroni fashion” to the present. Although it was unique to its period and location, there are general lessons we can learn from its emergence and popularity that we can apply to the modern era.

20

Models: Simran Mahtani, Carmen Chang, Maahika Singh, Imrana Pirbay, Sarah Mokhtari

The macaroni style was initially inspired as a means of rebelling against common norms and expressing individualism. Even today, fashion is utilised to subvert social norms and expectations and is still a potent means of self-expression. Individuals can use fashion to express originality. Our goal in our shoot is to promote the idea that people can wear whatever they want, even if it seems unconventional or outside the norms of Western fashion. Instead of focusing on trends and illusions created by the fash

ion industry, we encourage people to explore their own unique sense of style and creativity, and to wear clothing that makes them feel confident and comfortable in their own skin. People now create their own occasion to wear whatever they want to wear. Ultimately, we believe clothes are always fashionable, regardless of whether they conform to latest trends or styles. Fashion should be a form of self-expression that reflects our individual personalities, cultural identities, and personal values.

Designer: Sarina Seth MUA: Hsiao Hsuan Jin

Designer: Sarina Seth MUA: Hsiao Hsuan Jin

HESE AREN’T boobs!

HOW DRAG CULTURE CONTOURS

FLAT FASHION

In fashion, proportion and silhouettes are the central focus of styling. From the golden ratio to the hourglass figure (and the endless variety of buzzwords society coins for them), artists to celebrities, drag performers to fashionistas make sure that their proportions and silhouettes are not only fashionable but also visually illusive to fit whatever persona or vibe they are emulating. Not to be confused with always working in favour of society’s beauty standards, proportions are important more so for tapping into the potential the body possesses regardless of size, colour, and/or shape.

Drag legendaries such as Danny La Rue, Divine and The Cockettes encompass perfect examples of how gender-bending performers use extensive methods to attain the ‘right’ proportions for their drag characters. For drag queens, the most notable, and arguably most known, technique is padding, using a foam or silicone to produce more curvaceous features mimicking those of a ‘traditional’ woman’s body. Padding is often used in conjunction with corsetry to create the illusion of an hourglass figure; a body type that is depicted as the ‘standard’ of feminine bodies. Queens also use techniques such as tucking to allow for the crotch bulge to become inscrutable in one’s physical appearance.

For drag kings, on the other hand, techniques are often more aimed at achieving a more ‘masculine’ or

22

androgynous appearance. One such technique is that of binding which is a popular method of compressing and flattening the chest area using specialised garments. Further, the face is another dimension in which drag artists can transform themselves using makeup, particularly through contouring. By manipulating lighter and darker shades, one can alter jawline, nose and lip definitions to create the desired effect. Contouring can also be used to create illusions on other parts of the body such as the chest.

Intense performers, for instance, may find breast padding to be inconvenient and instead may opt for contouring the upper parts of the chest to create the illusion of cleavage. While seemingly used for base-level alterations in their physical appearance, illusions in drag push boundaries not only in fashion but in all aspects of art. Pythia and Priyanka are drag artists who presented an artificial real-looking head and synthetic hands on runways. These bold moves challenge society’s notion of ‘the Right Proportion’ and where it lies within the imagination.

by Addington Willimams and Offa

The culmination of these boundary- pushing practices is influencing the mainstream fashion industry to re-evaluate the fashions used in the more ‘mainstream’ industry; Jared Leto carrying a one-to- one copy of his head on the runway, Doja Cat wearing a prosthetic nose and Janelle Monae performing a gimmick silhouette transformation on Met Gala— thought these examples may appear excessive yet detached from meaning at first glance, the shift away from the ‘norm’ is what drag is all about.

No matter what obstacles the drag culture might face, these practices will always be central to the future of fashion. Drag isn’t just about wearing fake boobs and high heels. Drag is about making visual illusions wherein one can craft a limitless reality from dreams.

23

Sinfrey Photography: Songju Kang

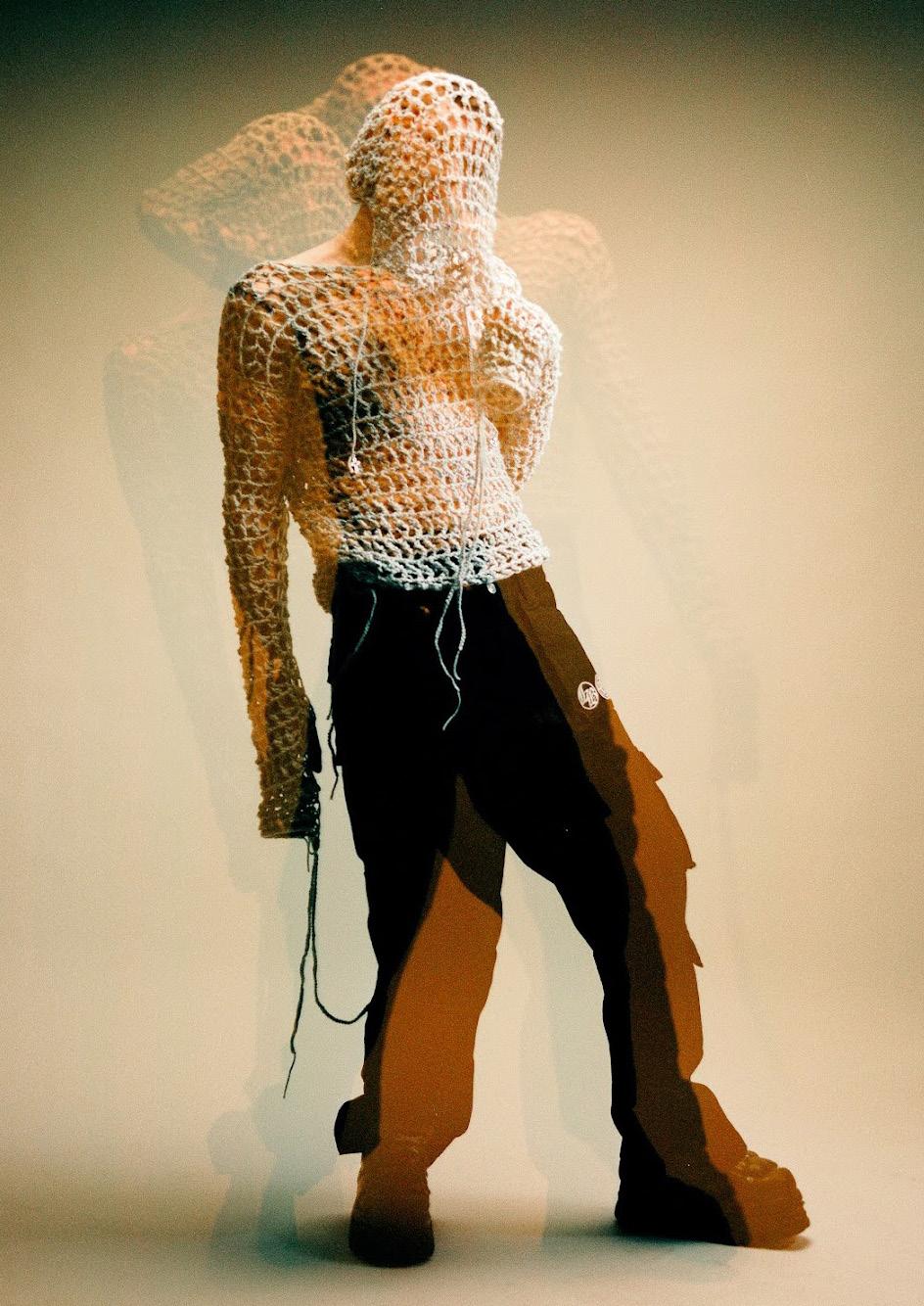

Director/Stylist: Hsiao Hsuan (Charlotte) Jin

Photographer: Claire Yubin Oh

Technical aid: Eileen Chang

Creative team: Hsiao Hsuan (Charlotte) Jin, Tatiana Gagalowicz

There is nothing in this physical world that truly embodies my soul. I am given this organic form and I learn to live with it.

With this body, I dance in my room, howl through the night streets, and lie among the wet blades of grass under the light spring rain. I learn to live and find beautiful things in this world to adorn myself with.

I just want to live truly; experience and fall in love with the elements of the world. To rage with the thunderstorm and to die and rebirth with the sun.

Walking through the forest at night, I found other souls adorning themselves with different elements of the world. They showed me the beauty in this world that I didn’t notice before: the way the smallest stars shine as bright as the sun, how life thrives as it branches on the skull of death, and the way they beautifully exist in their most organic forms.

I decorate my body with the worldly elements, and I see how my body is harmonious with everything.

We danced together despite the different elements and existence. We celebrate the world and we find our coexistence.

model phenomena in society.

The use of slimming illusions in the fashion industry is by no means a novel concept. Advocating for extremely thin physiques has been part of designers’ lines and the fashion scene for over a century. This body ideal can be traced back to just before the 20th century, though it became an important part of Western society during the ‘flapper’ era of the 1920s, where women began to break away from traditional stereotypes of femininity and embraced a more liberated and in the eyes of society at that time, a more masculine lifestyle. The ‘flapper’ style was characterised by loose-fitting clothing and a slim, boyish figure. After this era of fashion, being tall and thin was rapidly idealised and was linked with being a

Visual tricks to produce the illusion of a slim physique have long been a staple of the fashion arena. These techniques have been utilised in the past in hope of making the designers’ clothes more attractive to buyers, making audiences believe that the clothes will shrink their figures by creating a thinner silhouette. These days, a commonly employed technique is the use of the HelmHoltz illusion which involves the use of diagonal lines or patterns generating a leaner and more elongated shape. A majority of designers have used these visual tricks in many of their collections such as Stella McCartney and Haider Ackermann. Similarly, simpler techniques such

egative illusions

by Lola Caputo

as padded shoulders in clothing are used to enhance the narrowness of the rest of the body by comparison. The undeniable problem with these fashion illusions is that they perpetuate an impossible ideal.

The models underneath the clothing are not the same shape as the clothing makes them seem and these illusionary techniques can lead to an unhealthy obsession with achieving an unattainable body in both the models and the consumers. Though these slimming techniques may be seen as a healthier option to dieting, the fashion industry is still unable to shake it’s history as a purveyor of unrealistic beauty standards. The primary reason behind these illusions is financial - clothes are more attractive to buyers, but at what cost? We need to demand more from the fashion industry. More diversity, more inclusive, and more acceptance of all body types as the promotion of not just a slimmer figure but an unattainable body is detrimental to consumers’ self esteem and self perception.

In recent years, the inclusion of plus-sized models in advertising and on runways has been a much needed step for the fashion industry towards body inclusivity though undoubtably much more needs to be accomplished. That being said, with the advancement of technology in the fashion industry a new illusion has emerged - Al models - and with it, a whole new set of problems. Through the use of Al, designers can create a digital avatar, in other words a fake person - an illusion, to wear their clothing lines. These technological models have placed further emphasis on skinniness as they can be altered

to an extremely thin figure, far thinner than a real human could sustain without suffering heath issues. The use of Al models reinforces the narrow beauty ideals of the toxic industry and further promotes unachievable body types. The narrow ideals created through the fresh use of avatars may contribute to feelings of low-self esteem and mental health struggles such as eating disorders among society.

But it doesn’t stop there. The use of Al models not only reinforces damaging beauty standards but it also allows for biases to continue to permeate the fashion industry. Despite not being real people, Al models are not neutral, the coding behind their entire existence is biased. If a model’s code is built on previous fashion data - prejudice and discrimination of society is reflected in their algorithm. For example, the Al could prioritise conventional Eurocentric features and beauty standards over other ethnicities which would be damaging to already marginalised ethnic groups.

The use of slimming illusions and Al models in the industry which places excessive importance on skinniness needs to be reevaluated. To truly promote body inclusivity and positive self-image, the fashion industry as a whole needs to hold itself to a higher standards and take accountability for its past and current promotion of harmful body ideals. Consumers should support designers who are making waves in the industry to protect all body types and hopefully the toxicity surrounding body image in fashion will develop into a celebration of all body types.

31

Phtographer: Sam Prescott

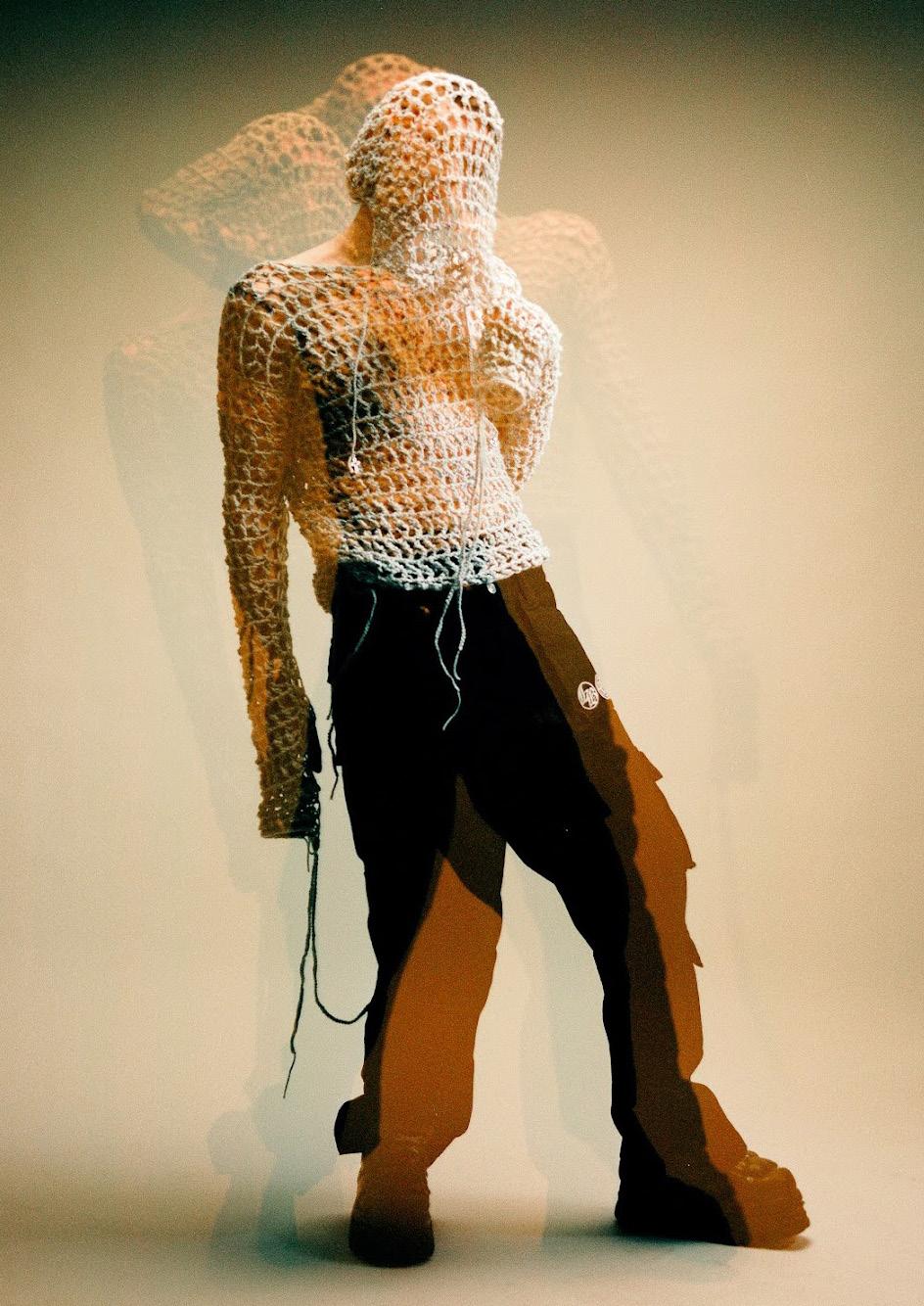

PARASITE

Sustainable fashion, made in the United Kingdom

Instagram: @parasite_sf

Website: www.parasitesf.com

33

Creative Direction: Rachael Hawthorne, Giacomo Tanner

Models: Szymon Kogut, Ibukun Osi, Maria Eto

35

Instagram: @uclmodomagazine Email: modomagazine.ucl@gmail.com SPRING 2023

by Ademi Nwadike Photographer : Vittoria Avigliano

by Ademi Nwadike Photographer : Vittoria Avigliano

by Maahika Singh and Tom Holmes

by Maahika Singh and Tom Holmes

by Imrana Pirbay and Sarah Mokhtari

by Imrana Pirbay and Sarah Mokhtari

Photographer: Songju Kang

Photographer: Songju Kang

Designer: Sarina Seth MUA: Hsiao Hsuan Jin

Designer: Sarina Seth MUA: Hsiao Hsuan Jin