Andy Warhol: A Life Well Drawn

An Exploration of Andy Warhol’s Life Through Drawings from His Last Decade

Long-Sharp Gallery

1 North Illinois, Suite A Indianapolis, IN 46204

The Indianapolis gallery is open by appointment, though you can always explore our virtual galleries here. To inquire about works available, make an appointment in Indianapolis, or speak with a member of the gallery team:

Telephone: +1 866 370 1601

Email: info@longsharpgallery.com

www.longsharpgallery.com

To view videos of any of the featured works, look for the icon

Andy Warhol: A Life Well Drawn

An Exploration of Andy Warhol’s Life Through Drawings from His Last Decade

Introduction

Andy Warhol’s hand was undoubtedly skilled. That skill transformed commercial art, fine art, and the art world in ways well beyond one exhibit’s ability to communicate. In this exhibition, larger-scale drawings from Warhol’s last decade serve not only to illustrate his skill, but to provide insight into the last decade of his life.

Warhol’s innate artistic talent landed him at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in the late 1940s, where as a student he developed his signature blotted line technique. Warhol attributed the origin of this technique in part to a dissatisfaction with his artistic abilities.1 Nevertheless, when Warhol moved to New York in 1949 to work as acommercial artist, his blotted line technique and whimsical style were well-received. The largerpart of his oeuvre from the 1950s – pen and ink compositions in that now-beloved style – were championedin New York commercial illustration circles evenas “photography was increasingly supplanting illustration.”2 Indeed, part of the genius in his 1950s newspaper ads was that, even in print, they appeared hand-drawn.3

Vincent Fremont, co-curator of the New York Academy of Art’s 2019 exhibit Andy Warhol: By Hand, describes drawing as “vital” to Warhol’s artistic practice.4 Although Warhol’s work impacted fields from film to fashion, publishing to rock & roll, everything he created – from the beginning of his career to the end of his life – emanated from his skill as a draftsman. To that end, though he “retired” from painting in the mid-1960s, Warhol’s hand-drawn line again took center stage in

the 1970s. Several screenprint projects from the era, such as Flowers (Black and White) (1974) and Skulls (1976), championed the hand-drawn line.

The last decade of his life saw Warhol engaged in an escalating number of hand-drawn compositions. Indeed, almost half of the print projects Warhol created during his lifetime were produced in his last decade.5 Each of these print projects began with Warhol’s skilled hand and eye, as photography and drawing (normally in graphite, but sometimes with polymer paint) were at the conceptual beginning of this enormous body of work.

Through this exhibition of fifteen drawings from the 1980s, we highlight various facets of Warhol’s life and career. We explore how Warhol shared his gifts with charities and the arts (pages 6-9); how he merged commercial advertising and fine art (pages 10-15); the ways Warhol both championed causes and published books over the decades (pages 16-19); how he used his studies to create gifts for friends and colleagues (pages 20-21); how fashion permeated Warhol’s career from the 1950s to 1980s (pages 22-31); how his body of work found relevance throughout four decades of printmaking (pages 32-33); and finally how religion impacted and inspired Warhol’s life and work (pages 34-35).

Through these drawings from his last decade, we explore Andy Warhol – the man and the artist.

With love (of art),

Nicole ML Sharp2 Ibid.

3 Ibid., 20-21.

4 New York Academy of Art, Press Release, “New York Academy of Art presents Andy Warhol: By Hand,” accessed December 1, 2022, https://nyaa.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/WarholEx19-PressRelease-1-1.pdf.

5 De Salvo, “God is in the Details,” 30.

1 Donna De Salvo, “God is in the Details: The Prints of Andy Warhol,” in Andy Warhol Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné 1962-1987, 4th ed. (New York: D.A.P., Ronald Feldman Fine Arts & The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, 2003), 20.Water Color Paint Kit with Brushes

Andy Warhol was an accomplished artist across disciplines – drawing, photography, screenprinting, painting, sculpture, film – and was quite prolific. His oeuvre spans subject matter from portraits to still lifes to landscapes, and he is said to have created over 9,000 paintings and sculptures and 12,000 drawings in the course of his career.1

Yet, Warhol created few works like Watercolor Paint Kit with Brushes that pay tribute to that which made him famous—that is, the foundations and tools of art-making. The subject of a watercolor paint kit is perhaps even more tongue-in-cheek for Warhol, who eschewed paint and brush for several decades of his career. Indeed, he told TIME magazine in 1963: “Paintings are too hard. The things I want to show are mechanical. Machines have less problems. I’d like to be a machine. Wouldn’t you?”2

Warhol’s Watercolor Paint Kit with Brushes is particularly indicative of his process. There exist polaroid photographs, drawings, and unique screenprints on the subject, all of which led to a regular edition of prints created in 1982. The screenprint was physically quite small (nine by twelve inches) and created in an edition of 500 plus proofs. It was made to raise funds for the New York Association for the Blind.

1 “Paintings, Sculptures, and Drawings,” The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, accessed November 4, 2022, https://warholfoundation.org/warhol/catalogue-raisonne/paintings-sculptures-drawings/.

2 “What Was Andy Warhol Thinking?,” Tate, accessed November 4, 2022, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/andy-warhol-2121/what-was-andy-warhol-thinking.

Andy Warhol

Watercolor Paint Kit with Brushes Circa 1982 Graphite on paper

23.5 x 31.75 inches (59.7 x 80.6 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 104.002) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 104.002 Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

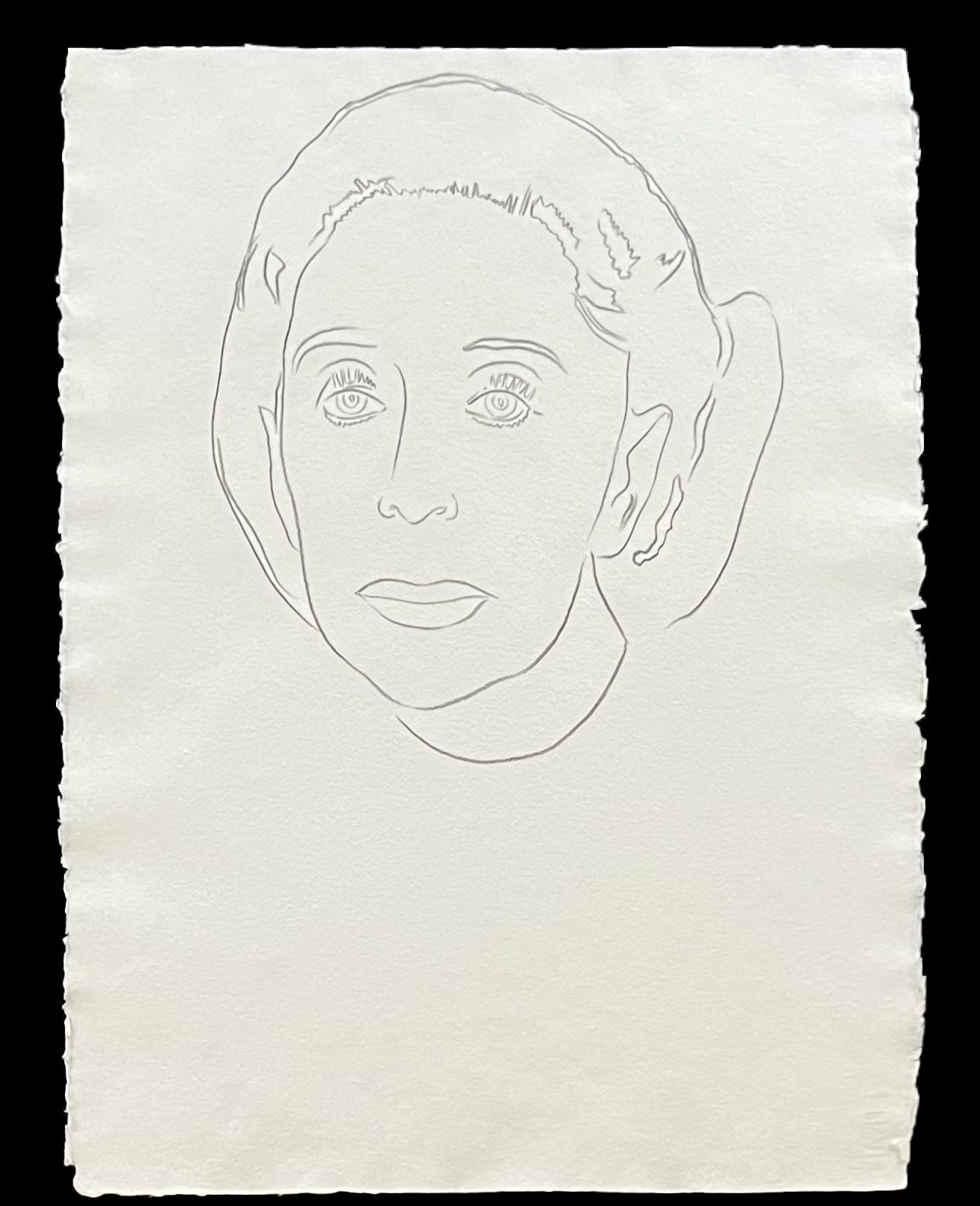

Martha Graham

Andy Warhol’s brother John recalls Warhol’s early desire to be a tap dancer.1 While living in Pennsylvania in 1948, Warhol enrolled – as the only male, no less – in the Modern Dance Club at Carnegie Tech.2 That summer, two of Warhol’s works – I Like Dance and Dance in Black and White – were chosen for a juried show for the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh.3 (The show tipped off dance club members to Warhol’s talent; as a result, he was relegated to graphic design for the group instead of actually dancing.) Once in New York, he applied for a job as a commercial illustrator at Dance Magazine in 1951.4 He contributed several drawings, including two covers, to the publication.5

When Warhol moved to New York City at the end of the 1940s, New York was overflowing with musicians, dancers, and avant-garde performers. For decades, he was a devoted attendee at theatre performances, concerts, and counterculture events. Works spanning the 1950s to the 1980s reflect this immersion in arts and music. It is perhaps no wonder, then, that the enigmatic Warhol befriended fellow artist, dancer, and choreographer Martha Graham during this time.

Touted as both the “Mother” and the “Picasso” of Modern Dance, Graham and Warhol were long-time friends. He frequently attended her dance shows and fundraisers, and the pair was often seen in a group with Liza Minnelli and fashion designer Halston.

In addition to pencil drawings of Graham, Warhol created the Martha Graham suite in 1986, both to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Martha Graham Dance Company and to raise funds for her planned school of dance in Florence. The suite was comprised of three images: Lamentation, Letter to the World (The Kick), and Satyric Festival Song. Each image was based on a photograph taken by Barbara Morgan between 1935 and 1942 of the legendary Graham in motion.

According to Graham, “When I first met Andy, he confided to me that he was born in Pittsburgh as I was, and that when he first saw me dance ‘Appalachian Spring’ it touched him deeply. He touched me deeply as well. He was a gifted, strange maverick who crossed my life with great generosity. His last act was the gift of three portraits he donated to my company to help my company meet its financial needs.”6

1 “Warhol and Dance!,” Carnegie, January/February 1999, https://carnegiemuseums.org/magazine-archive/1999/janfeb/feat6.htm

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Wendy Perron, “The Secret Dance Life of Andy Warhol,” Dance Magazine, August 8, 2016, https://www.dancemagazine.com/secret-dance-life-andy-warhol/.

5 Ibid.

6 Douglas C. McGill, “Andy Warhol, Pop Artist, Dies,” New York Times, February 23, 1987, https://www.nytimes.com/1987/02/23/obituaries/andy-warhol-pop-artist-dies. html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

Andy Warhol

Martha Graham

Circa 1980 Graphite on paper

Size: 31.5 x 23.5 inches (80 x 59.7 cm)

Framed: 39 x 31.5 inches (99 x 80 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 114.061) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 114.061 Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

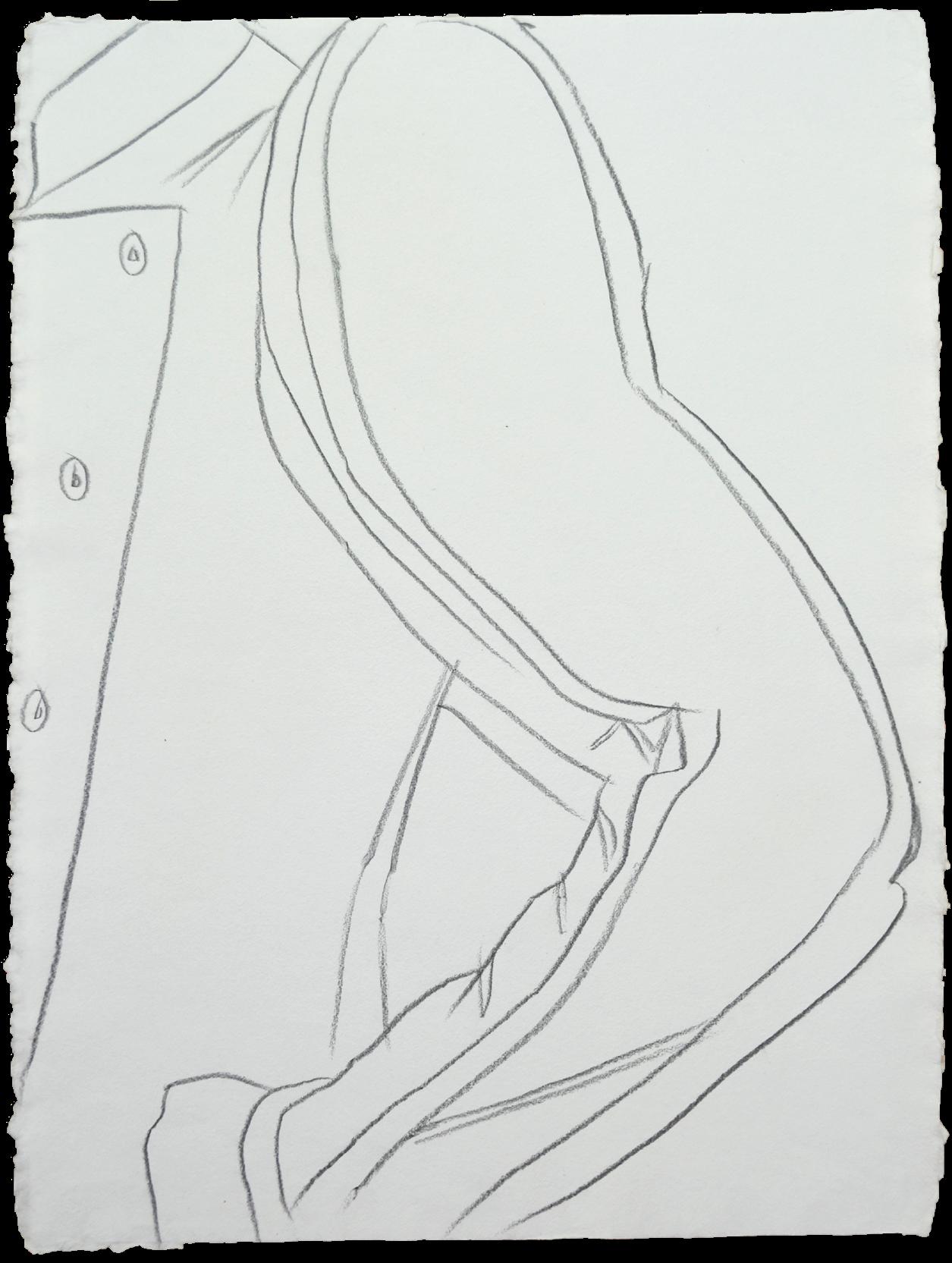

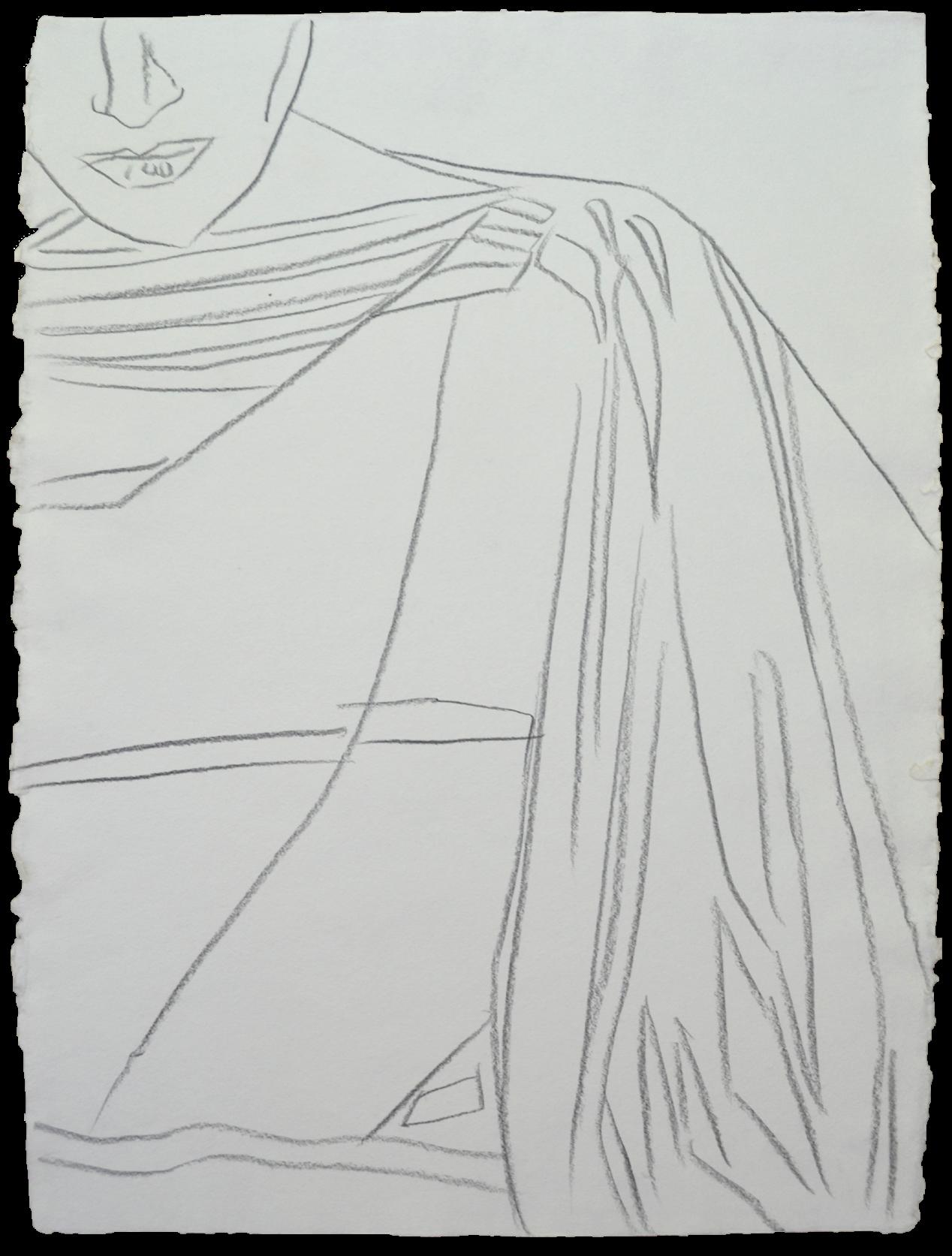

Halston Advertising Campaign

“Advertising is communication, persuasion – Andy practiced the art of persuasion as well as anybody.”

- Stephen Frankfurt, Art Director, Young & Rubicam.1Imbued with a keen eye, inimitable wit, and an intuitive sense of mass appeal, advertising may have been the perfect microcosm for Andy Warhol. “Warhol’s commercial output in the 1950s lay squarely in the ‘creative’ camp, while also revealing a natural aptitude for understanding the psychological factors at play in consumer desire.” 2 Whether illustrating for magazines like Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Glamour, or any of the other national publications that eagerly snapped up his designs, Warhol was able to capture and capitalize on the pulse of pop culture. He applied this same savvy to collaborations with famous designers of the era, though perhaps none more vociferously than fashion designer Halston.

The two powerhouse entrepreneurs met in the early 1970s through fashion designer Joe Eula. They became close friends who each influenced the other’s creative practice in unique ways. Halston, for example, used Warhol’s works as inspiration for his designs, including a 1972 dress based on Warhol’s 1964 Flowers canvas. Indeed, the two were so involved in each other’s careers that a book has been written on their friendship and collaborations, Halston and Warhol: Silver and Suede (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2014)

In 1982, Warhol designed an advertising campaign for Halston’s eponymous brand, including features for menswear, accessories, and fragrance. When Warhol created the drawing featured here as part of that campaign, his relationship to advertising was nothing new; rather, it was an extension of a skill developed in the early days of his career and honed over time.

1 Nicholas Chambers, “Andy Warhol: adman,” in Adman: Warhol Before Pop, ed. Nicholas Chambers (Sidney & Pittsburgh: Art Gallery of New South Wales & The Andy Warhol Museum, 2017), 18. 2 Ibid., 16.Andy Warhol

Fragrance and Cosmetics, Study for Halston Advertising Campaign

1982

Graphite on paper

30.25 x 40 inches (76.8 x 101.6 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 79.011) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 79.011 Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

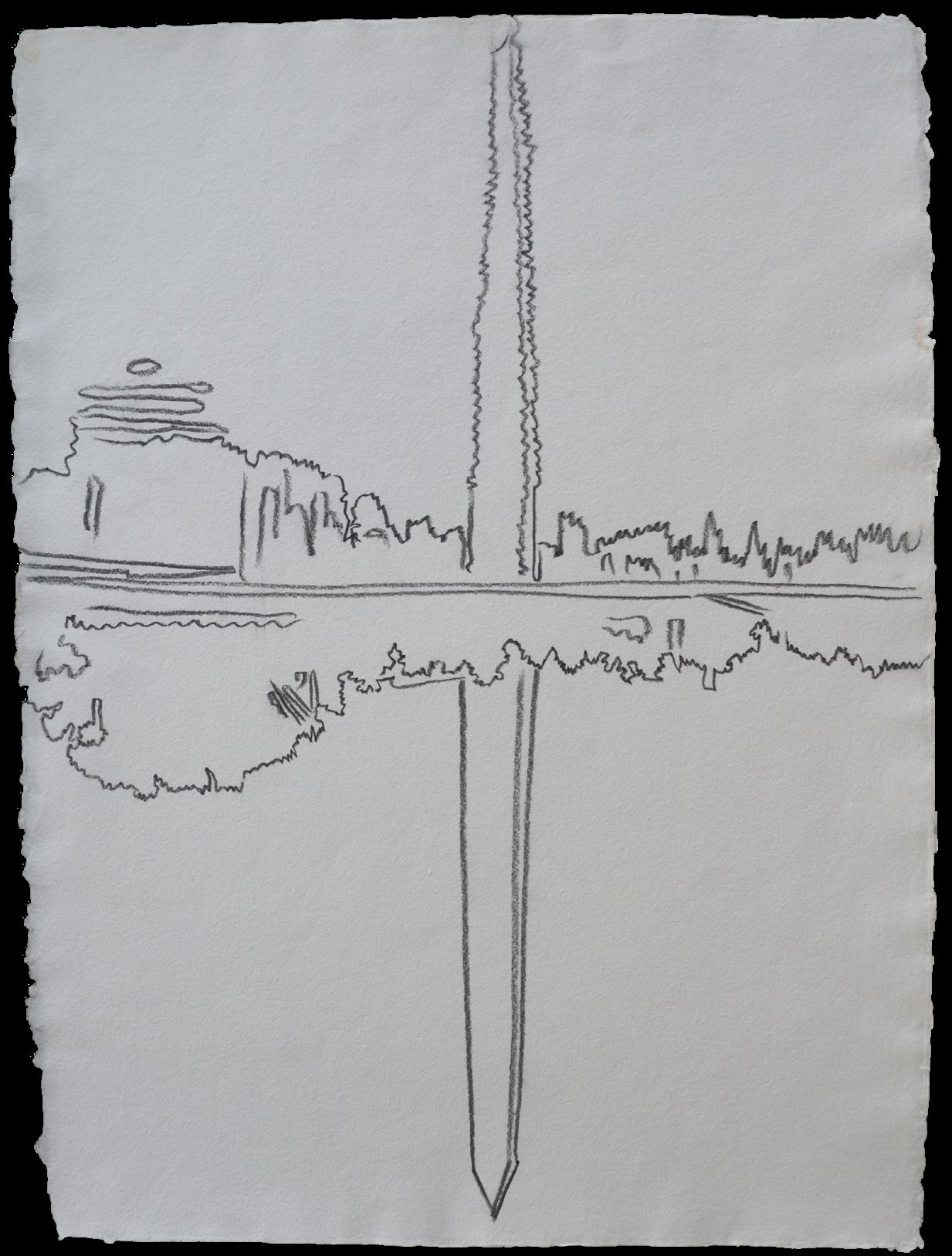

Washington Monument and Tidal Basin

In the same way that his Campbell’s soup cans or portraits of Marilyn Monroe have become iconic images of the Pop Art movement, Andy Warhol’s signature illustration style for important magazines from the 1950s through the 1980s was iconic as well. He created in this artistic arena throughout his life. In his last decade, his skill as a commercial draughtsman took many forms. One might find his work on the cover of a magazine or in advertisements benefitting friends and colleagues.

“Over the course of the 1950s, Warhol was awarded numerous industry accolades and worked on a diverse range of commissions. He was sought after not only for the unique style of his illustrations, but also for his sophisticated understanding of how to create a successful advertisement.”1 His unique ability to distill an object to its most fundamental could be said to underlie every aspect of Warhol’s career.

When commissioned to create and design the cover of the Washington Post Magazine in 1983, illustration remained a pivotal part of Warhol’s creative process. He created two images for the cover, putting his signature style to work on Washington, D.C.’s Tidal Basin and the Washington Monument. The final unique screenprint of the Tidal Basin was selected for the cover of the magazine on August 14, 1983.

1 Nicholas Chambers, “Andy Warhol: adman,” in Adman: Warhol Before Pop, ed. Nicholas Chambers (Sidney & Pittsburgh: Art Gallery of New South Wales & The Andy Warhol Museum, 2017), 18.Andy Warhol

Washington Monument

1983

Graphite on paper

Size: 31.75 x 23.5 inches (80.6 x 59.7 cm)

Framed: 39.25 x 31 inches (99.7 x 78.7 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 67.002) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 67.002

Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

Andy Warhol

Tidal Basin

1983

Graphite on paper

Size: 31.25 x 23.5 inches (79.4 x 59.7 cm)

Framed: 39.25 x 31.75 inches (99.7 x 80.6 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 67.017) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 67.017

Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

2

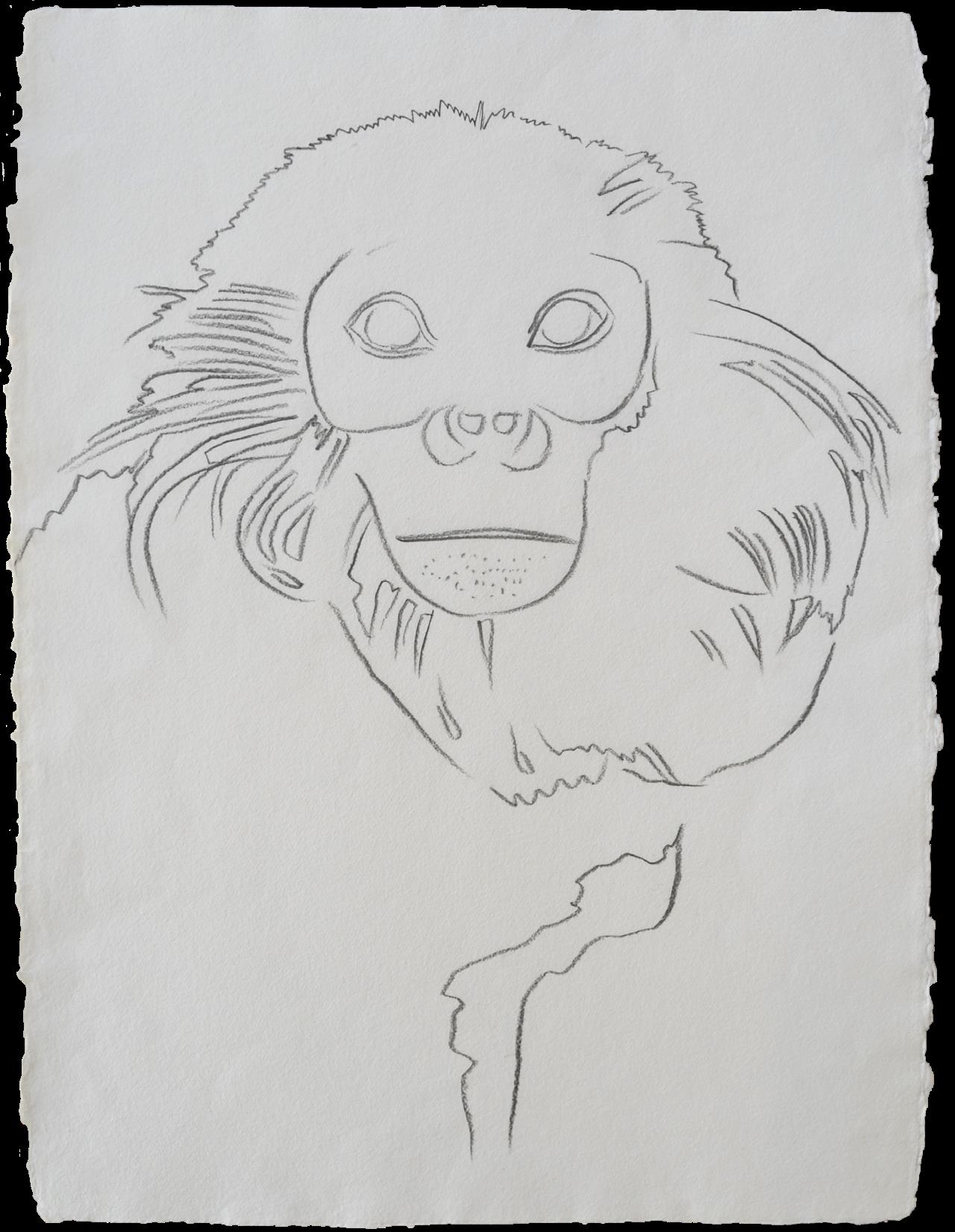

Vanishing Animals

In the 1980s, Andy Warhol embarked on several projects focused on animals, including among them his suites of Endangered Species and Vanishing Animals. Studies and screenprints of Vanishing Animals led to an eponymous book created in collaboration with German American conservationist Kurt Benirschke of the San Diego Zoo.1 The studies presented here depict two of the animals included in the Vanishing Animals suite: Douc Langur and La Plata River Dolphin.

Warhol’s interest in endangered animals was in some ways an extension of themes Warhol had explored throughout his career. As gallerist Fergus McCaffrey posits in the catalog accompanying the 2006 exhibition Andy Warhol –Vanishing Animals:2

Warhol’s concern about the death of entire species of animals fits neatly into the lexicon of untimely and unseemly ends that he repeatedly mused on during his long career. Bearing in mind the self-referential nature and frequent quotation of his own earlier work in much of the output of the 1980s, it does not take much of a leap to imagine Warhol making a connection between the suicides, car crashes, poisonings, executions, and pervasive threat of nuclear annihilation of the 1960s and the tragic plight of Vanishing Animals in the 1980s. After all, extinction is just another variety of death, and one gets the sense that Warhol was sensitized to care equally for man and beast.

1 Kurt Benirschke and Andy Warhol, Vanishing Animals (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986). Fergus McCaffrey, Andy Warhol: Vanishing Animals (St. Barthélemy, French West Indies: Me.di.um, 2006). https://www.marcjancou.com/writings/andy-warhol-vanishing-animals.Andy Warhol

Douc Langur

Circa 1986

Graphite on paper

31.5 x 23.5 inches (80 x 59.7 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 89.065) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 86.065

Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

Andy Warhol

La Plata River Dolphin 1986

Synthetic polymer on paper 23.375 x 31.5 inches (59.4 x 80 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 89.017) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 89.017

Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

Candy Box

From his proclamations at dinner parties, “Oh, I only eat candy,” to his “usual” Frozen Hot Chocolate drink at the New York City café Serendipity 3, Andy Warhol’s affinity for chocolate and sweets is legendary. Perhaps less known is that it appears to have been genetic: his mother, Julia Warhola, is quoted as being persuaded to marry Warhol’s father, Andrej, in part because he gave her candy.1 Her love for sweets was instilled in Warhol early and was perhaps subconsciously related to his creativity; Warhol recounts childhood memories of receiving candy bars in exchange for every page completed in his coloring book.2 During his decades in New York, entries from his diary recount visiting several candy shops and chocolatiers, including one instance when he stopped into a candy shop intending to sell them advertising space in Interview magazine, but ended up “buying $200 worth of candy instead.”3

It is perhaps no surprise, then, that Warhol translated his love of candy into his work. He first mentions a “chocolate box of art candy” in his diaries in 1980 as a Christmas gift for his friend Halston.4 In 1982, he gifted a chocolate box containing a piece of cement bearing his signature to Halston’s butler, Lorenzo Vasquez.5 Then, in 1983, he began a series of prints based on a box of chocolates. As with the rest of his artistic practice, photographs and drawings preceded the prints; the graphite presented here is one such study drawing.

1 Wayne Koestenbaum, Andy Warhol: A Biography (New York: Open Road, 2001), 22, reprinted in New York Times, September 16, 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/16/books/chapters/andy-warhol.html.

2 Ibid.

3 Andy Warhol, The Andy Warhol Diaries, ed. Pat Hackett (New York: Warner Books, 1989), 156.

4 Ibid., 352.

5 Eric Shiner, “Andy Warhol: Thinking Inside the Box,” Sotheby’s, February 17, 2017, https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/andy-warhol-thinking-inside-the-box.

Andy Warhol Candy Box

1981

Graphite on paper

31.75 x 23.75 inches (80.6 x 60.3 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 65.002) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 65.002 Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

1980s Fashion

Upon graduating from Carnegie Tech with a degree in Pictorial Design, Andy Warhol moved to New York in 1949 to become a commercial illustrator. He was quickly hired on by the likes of Glamour, Vogue, and Harper’s Bazaar magazines. According to Simon Doonan’s foreword in Andy Warhol: Fashion: “From his whimsical line drawings of cats to sleek renderings of ladies’ shoes, Warhol’s work became a hit in the fashion publishing world. Warhol sketched hundreds of drawings of shoes, handbags, jewelry, and gloves.” 1

Warhol’s interest in fashion, however, was not limited to commercial illustrations and advertisements. Over the decades, Warhol would befriend, collaborate with, and create portraits of designers including Halston, Yves Saint Laurent, and Diane von Furstenberg. Models, especially in the 1960s, were a new kind of celebrity, and Warhol capitalized on this notoriety. He is recognized as one of the first artists to print his work onto clothing and sell it exclusively to high profile clientele. At one time, Warhol himself could be booked as a model through the Zoli and Ford Models agencies. As to the importance of fashion during his time, Warhol captured it best: “Fashion wasn’t what you wore someplace anymore; it was the whole reason for going.”

1 Simon Doonan, Andy Warhol: Fashion (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2004), 7.Andy Warhol Fashion

1981

Graphite on paper

31.375 x 23.375 inches (79.7 x 59.4 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 78.012) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 78.012 Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

Andy Warhol

Fashion

Circa 1984 Graphite on paper

31.375 x 23.375 inches (79.7 x 59.4 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 78.015) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 78.015 Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

Andy Warhol

Fashion

Circa 1984 Graphite on paper

31.25 x 23.5 inches (79.4 x 59.7 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 78.007) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 78.007

Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

Andy Warhol

Fashion

Circa 1984 Graphite on paper

31.625 x 23.625 inches (80.3 x 60 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 78.006) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 78.006 Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

Paola Dominguin

Paola Dominguin grew up in a family of creatives. Her father was a renowned Spanish bullfighter, her mother an Italian actress, and her brother, Miguel Bosé, a famous musician. (Warhol created the cover art for one of Bosé’s albums in 1983.)

Dominguin was a model in New York in the 1980s and walked in Carolina Herrera’s first show as a fashion designer. Herrera, adored by Warhol, presented her collection on April 27, 1981, at the Metropolitan Club in New York.1 It was the first time the venue had permitted a fashion show within its walls.2 The debut was attended by Warhol, Paloma Picasso, Diana Vreeland, and Bianca Jagger.3 American fashion giant Bill Blass helped Herrera book the group of models that included Dominguin. Later, Warhol took polaroid photographs of the model in addition to sketches like the one shown here.

Andy Warhol

Paola Dominguin

1982

Graphite on paper 31.25 x 23.625 inches (79.4 x 60 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 78.004) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 78.004 Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

Indian Head Nickel

Andy Warhol was fascinated with the American West. His time capsules and scrapbooks from childhood include photos and paraphernalia of Western stars including Roy Rogers and Gene Autry. Entries in his diary from the 1970s and 1980s mention outfits sporting cowboy boots.1 This interest manifested in his work as early as 1963, when he integrated an image of Elvis from the Western film Flaming Star into his oeuvre. Warhol also produced two avantgarde Western films around that time: Horse (1965) and Lonesome Cowboys (1968).

The magnetism of the American West continued to attract Warhol in later decades. He completed a portfolio of works depicting Native American civil rights leader Russell Means in 1976 followed by his famous Cowboys and Indians suite in 1986. The ten screenprints in the latter portray images of the American West culled from both reality and fiction; for example, performer and sharp-shooter Annie Oakley and film star John Wayne are presented alongside Apache leader Geronimo and an anonymous Native American mother and child. According to Bethany Montagano, curator of the Eiteljorg Museum’s 2007 exhibition

Andy Warhol’s Cowboys and Indians, Warhol’s imagery in the suite juxtaposes counterfeit cowboys against historical Indigenous figures to show that our misconceptions and stereotypes of Native Americans were created “through myth, the printed word, movies, and . . . not from personal experience.”2

The graphite presented here is a study for Indian Head Nickel, one of the ten screenprints included in the Cowboys and Indians suite. In addition to the historical and fictional personas in the suite, Warhol chose to include the Indian Head nickel (sometimes also called the Buffalo nickel). The first Indian Head nickels were struck in February of 1913. They had their unofficial debut at the groundbreaking ceremony for the National American Indian Memorial in New York – a memorial that was never built. They were produced for the minimum time allowed by law (twenty-five years) and then replaced by the Jefferson nickel in 1938.

1 Andy Warhol, The Andy Warhol Diaries, ed. Pat Hackett (New York: Warner Books, 1989), 102 & 406. 2 Marc D., “Worth Seeing: Cowboys & Indians: Eiteljorg showcases famous artists’ not-so-famous work,” Indianapolis Business Journal, March 19, 2007, https://www.ibj.com/articles/12604-worth-seeing-cowboys-indians-eiteljorg-showcases-famous-artists-not-so-famous-work.Andy Warhol

Indian Head Nickel 1986

Graphite on paper

Size: 31.5 x 23.75 in (80 x 60.3 cm)

Framed: 37.625 x 33.625 inches (96 x 85.4 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 73.043) on verso in pencil, initialed by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 73.043

Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

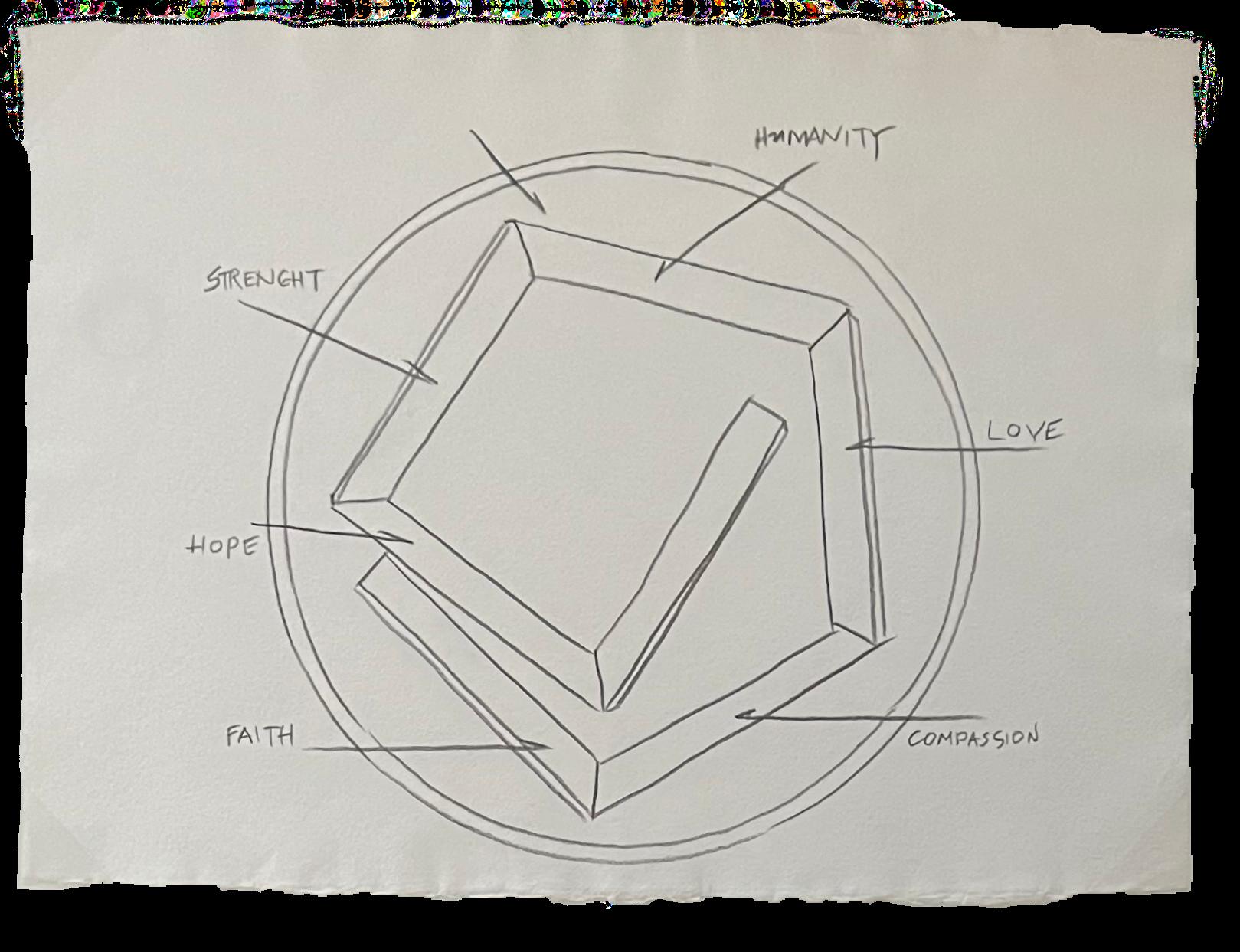

Pentagon With Virtues

Research into Andy Warhol’s Pentagon with Virtues yields inconclusive results; the piece is indeed unique. Much has been written about Warhol’s Catholic upbringing and his devotion to the Church.1 This dedication inspired several works throughout the artist’s life, from early 1950s drawings of angels to his 1980s depiction of The Last Supper. Perhaps the virtues delineated in this drawing stem from the same spiritual or religious inspiration.

Warhol’s misspelling of the word “strength” could have been intentional or a mistake. According to Molly Donovan of the National Gallery of Art, “while many reasons have been offered for Warhol’s numerous misspelled words – from intentionality, to dyslexia, to the broken English spoken by his immigrant parents – a definitive explanation is difficult to provide.”2 Several of Warhol’s friends and collaborators noted Warhol’s acknowledgment that mistakes were evidence of humanity’s imperfect, real essence, and that he was at times so “delighted” by these happy mistakes as to keep them in his works.3

1 See, e.g. Andy Warhol: Revelation (Pittsburgh: The Andy Warhol Museum, 2019); Jane Daggett Dillenberger, The Religious Art of Andy Warhol (New York: Continuum, 1998). 2 Molly Donovan, “Where’s Warhol? Triangulating the Artist in the Headlines,” in Warhol: Headlines, ed. Molly Donovan (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011), 9. 3 Victor Bockris, “a: A Glossary,” in a: A Novel, by Andy Warhol (New York: Grove Press, 1968, 1998), 453.Andy Warhol

Pentagon with Virtues 1980

Graphite on paper

Size: 23.5 x 31.625 inches (59.7 x 80.3 cm)

Framed: 34 x 41.75 inches (86.3 x 106 cm)

Authentication:

Authenticated by the Authentication Board of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamp on verso), Foundation archive number (TOP 110.024) on verso in pencil, by the person who entered the works into the Foundation archive.

Provenance:

Estate of Andy Warhol (stamped)

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (stamped), archive number TOP 110.024

Long-Sharp Gallery

Click to view a film

Bibliography

Benirschke, Kurt and Andy Warhol. Vanishing Animals. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986.

Bockris, Victor. “a: A Glossary.” In a: A Novel, by Andy Warhol, 453-58. New York: Grove Press, 1968, 1998.

Carnegie. “Warhol and Dance!” January/February 1999. https://carnegiemuseums.org/magazine-archive/1999/janfeb/feat6.htm.

Chambers, Nicholas. “Andy Warhol: adman.” In Adman: Warhol Before Pop, edited by Nicholas Chambers, 15-23. Sidney & Pittsburgh: Art Gallery of New South Wales & The Andy Warhol Museum, 2017.

D., Marc. “Worth Seeing: Cowboys & Indians: Eiteljorg showcases famous artists’ not-so-famous work.” Indianapolis Business Journal. March 19, 2007. https://www.ibj.com/articles/12604-worth-seeing-cowboys-indians-eiteljorg-showcases-famous-artists-not-so-famous-work.

De Salvo, Donna. “God is in the Details: The Prints of Andy Warhol.” In Andy Warhol Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné 1962-1987, 4th ed., 18-35. New York: D.A.P., Ronald Feldman Fine Arts & The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, 2003.

Donovan, Molly. “Where’s Warhol? Triangulating the Artist in the Headlines.” In Warhol: Headlines, edited by Molly Donovan. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2011.

Doonan, Simon. Andy Warhol: Fashion. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2004.

Fury, Alexander. “Carolina Herrera’s Very First Show — and What It Meant for Fashion.” The New York Times Style Magazine. April 16, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/16/t-magazine/fashion-1980s-carolina-herrera.html.

Koestenbaum, Wayne. Andy Warhol: A Biography. New York: Open Road, 2001.

McCaffrey, Fergus. Andy Warhol: Vanishing Animals. St. Barthélemy, French West Indies: Me.di.um, 2006. https://www.marcjancou.com/writings/andy-warhol-vanishing-animals.

McGill, Douglas C. “Andy Warhol, Pop Artist, Dies.” New York Times. February 23, 1987. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/02/23/obituaries/andy-warhol-pop-artist-dies.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm.

New York Academy of Art. Press Release. “New York Academy of Art presents Andy Warhol: By Hand.” Accessed December 1, 2022. https://nyaa.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/WarholEx19-PressRelease-1-1.pdf.

Perron, Wendy. “The Secret Dance Life of Andy Warhol.” Dance Magazine. August 8, 2016. https://www.dancemagazine.com/secret-dance-life-andy-warhol/.

Shiner, Eric. “Andy Warhol: Thinking Inside the Box.” Sotheby’s. February 17, 2017. https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/andy-warhol-thinking-inside-the-box.

Tate. “What Was Andy Warhol Thinking?” Accessed November 4, 2022. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/andy-warhol-2121/what-was-andy-warhol-thinking.

The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. “Paintings, Sculptures, and Drawings.” Accessed November 4, 2022. https://warholfoundation.org/warhol/catalogue-raisonne/paintings-sculptures-drawings/.

Warhol, Andy. The Andy Warhol Diaries. Edited by Pat Hackett. New York: Warner Books, 1989.