2 minute read

How did we end up at construction sites?

from Urban Clay

by mizajn

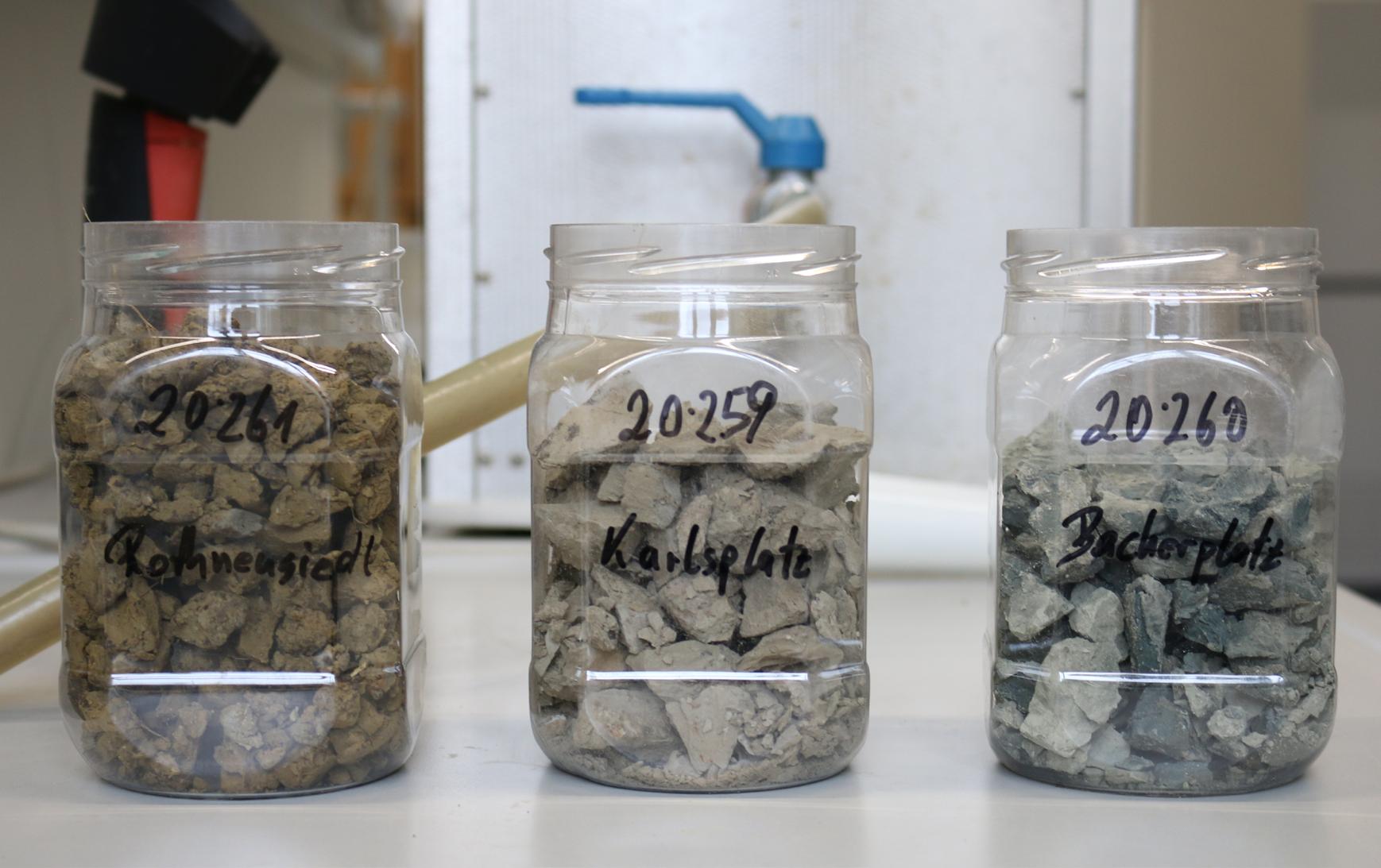

Not every old brick factory got turned into a nice green space. Some were simply demolished, and nearby clay deposits were sealed with a layer of concrete, asphalt and new buildings. This is precisely what happened to the XVIII century site in Bacherplatz, in the 5th district of Vienna. In the summer of 2020, excavation work began at this location for the relocation of various installations prior to the construction of the Reinprechtsdorfer Straße U2 subway station. The work proceeded under the supervision of archeologists, who predicted possible finds based on historical maps and data. The results of their research, including a map of the old brickyard, can be seen at the website of Stadtarchäologie Wien. The profile of a 4 meter deep drilling proved that the clay pits had been backfilled at some point. The finds included both fragments of even older medieval bricks, and a 19th century ceramic bottle, probably from the time of backfilling, all surrounded by the old/new, freshly opened clay deposit.6 One day, we asked the construction workers if we may take a lump of clay from what they dug out. ‘Of course,’ they said enthusiastically, ‘you can take as much as you want!’ – and handed me a heavy piece over the fence. This is how the research started.

Half a year later, more and more construction work are happening in the area, also north, near the station Pilgramgasse, and south, around Matzleinsdorferplatz. The machines you see most often are drilling rigs. Next to them, you can see piles of sand and wet clay. Construction companies are not very fond of archeological work since it usually stops the progress of a site. Likewise, they are not keen on clay, which is

Advertisement

a difficult substrate: it sticks to the excavators, makes a lot of mess and so on. What, then, happens to the gigantic clay mountains from the construction sites? According to current regulations, clay is treated like any other excavated soil. Depending on the level of contamination, it must be reused at the site or disposed of.7 Unfortunately, clay soils are not a good foundation. Their water absorption and swelling properties make them too unstable as a base for buildings. This may sound somewhat surprising, but excavated soil makes up 85% of Austria’s landfilled waste8. In the year 2014, 30,300,000 tons of soil got excavated in Vienna, and 18,400,000 tons of it, that is around 60%, ended up in a landfill.9 In the spirit of circular economy, the topic is becoming fairly popular, and there are already some projects, mainly in the area of architecture, dealing with reusing construction clay on site. The Zürich based project Oxara10, for instance, worked with excavation materials and patented cement-free concrete. Similarly, BC Materials11 from Brussels transforms earth excavated at local construction sites into building materials. More locally, in Vienna, the field of construction waste is addressed by Baukarussell12. They combine social issues with urban mining concepts by analyzing buildings for demolition and extracting components from them that can be reused. They also sell these building components to companies and individuals. Turns out that one person’s trash is another person’s treasure.

Figure 2. Worker at construction site near the U4 station Pilgramgasse during drillings, the gray pieces scattered around are clay.

Figure 2. Worker at construction site near the U4 station Pilgramgasse during drillings, the gray pieces scattered around are clay.