7 minute read

Small creators vs. big industry

from Urban Clay

by mizajn

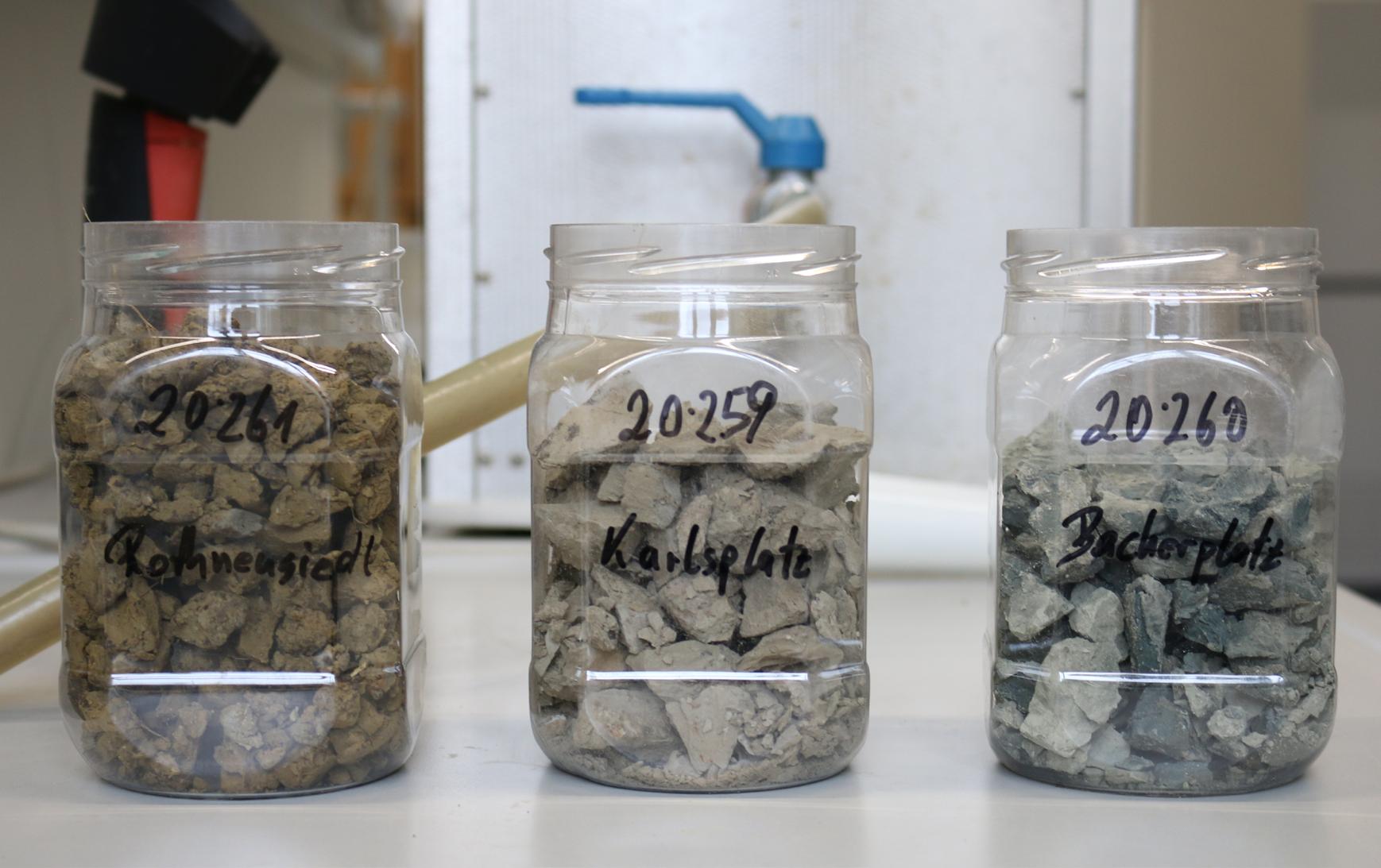

construction work consumes labor and energy, and its disposal in landfills generates costs. More research and properly guided city policies are needed so that a system of managing similar raw materials can emerge. A good example is the Warsaw Waterworks, which, on the occasion of water filtration works under the Vistula River in Poland, sell river sand to external entities19. In Vienna, on the other hand, municipal organic waste is turned into garden soil and sold under the name “Guter Grund”.20 We envision a future where Vienna has a similar system of clay management, where interested companies can obtain raw material from the city and citizens can buy a package of local clay, properly tested, described and composed for the creation of ceramics. This is why, as a part of our project, we labeled and packaged the clay we obtained from Bacherplatz to show what Vienna’s urban clay could look like in the future.

As we have already mentioned, art and utility ceramics exist in close relationship with big industry. Relying on natural raw materials whose sources are not inexhaustible, even simple plates can, to some extent, reflect socio-economic situations. There are many examples from recent history of events which have had a significant impact on the art of ceramics. For example, in the United States: Gerstley Borate, named after James Gerstley, former manager of Borax Consolidated Ltd., is a naturally occurring source of boron on which the vast majority of recipes for glazes designed for low temperatures is based. Especially in the United States, there were entire businesses that

Advertisement

based their production on this compound because it was cheap and reliable. It was mined in California for many years, but in 2000, U.S. Borax announced closing the mine, completely shaking the ceramic world.21 Currently, mostly chemically produced substitutes are available. In a more recent example, disruptions in the supply chain, caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, resulted in a raw materials shortage, and consequently a shortage of glazes of two big American producers, Amaco and Mayco.22

Figure 17. Ceramic-themed forum user commenting on talc shortages in the United States.

Daltile, a large U.S. manufacturer of wall and floor tiles, purchased the nation’s largest talc mine several years ago. The company recently issued a decision to stop selling the raw material externally, and smaller mines are unable to meet domestic demand.23 Art supplies are often made from the same raw materials used by global industries such as the car industry. Here again, because of the disrupted supply chain, large companies stockpile resources, leaving too little for smaller producers. The current raw material crisis is also affecting paper and cardboard packaging24, where shortages are obviously slowing down production and shipping of art supplies. Fuel prices are currently on an upward trend25, which could have a real impact on European imports of ceramic raw materials, e. g. from Germany to Austria. In such a situation, basing your

pottery production on available local materials seems to be a very sensible direction. With these predictions, we decided to visualize what everyday ceramics in urban mining Vienna could possibly look like in the future.

Urban Clay Pottery

To visualize what these Viennese everyday ceramics could look like, we created very simple bowls and plates, some with clay from Bacherplatz, some with clay from Karlsplatz. We wanted to recreate the process of producing a series of these dishes in a small studio, so the relative consistency of the pieces mattered. Due to the characteristics of the Bacherplatz clay, the casting technique popular in series fabrication was not an option. We decided to make plaster molds to press out the clay slabs. With this method, either the inside or the outside of the vessel can be molded, which makes this side more precise. Given the high shrinkage of our material, we chose the outer mold.

Figure 18. Preparation of the plaster model.

Figure 19. Cutting out slabs of clay for the bowl.

Figure 20. Finishing the plate on the pottery wheel.

Figure 21. Bowl taken out of the mold.

This is the process of production which resulted in our pottery: Since we did not have access to a pugmill, clay had to be prepared by hand by wedging. Wedging ensures a uniform consistency and moisture level of the clay, aligns the clay particles and gets rid of the clay bubbles. Suitable portions of clay were then rolled out into slabs before being cut into the appropriate shape and transferred to the mold. In the case of objects symmetrical around the axis, it was possible to finish the interior on the potter’s wheel. Clay has a “memory,” so when making vessels it is very important to compress the surface evenly and be careful not to create deformities, because even when repaired, deformities can return in the kiln during firing. The spirals which formed on the surface of the plate as we worked on the wheel reminded us of drills extracting clay. Machines responsible for test drilling usually create profiles between 15 and 30 cm in diameter. Our first lump of clay was a little over 20cm. The diameters of our dishes were designed to fall into this range as well. After finishing the surface, each item was left in the mold for 2 to 4 hours, depending on the initial moisture level of the clay. Once removed from the mold, there is the moment for corrections, repairing any cracks or irregularities, and removing plaster crumbs. The last and probably most challenging step before putting the pottery in the kiln is even drying. The Bacherplatz clay absorbs a lot of water and must be dried very slowly and carefully to avoid cracks and deformation. Round, regular forms such as bowls and plates proved to be a good test for the material. Especially the latter, flat objects tend to warp when dried too quickly. Factors such as whether the heating was on in the studio, or if it was a rainy day and someone had opened a window, had an impact. With the new material, it was also very much a trial-anderror method to find out the optimal drying time and

conditions. In comparison, the Karlsplatz clay behaved much better, possibly also due to the preparation in the machine. During drying, we did not observe any significant deformation, and the process itself took much less time. The next stage of production was the first firing at 980C, the so-called bisque. After removing the objects from the kiln, they were glazed. We chose the spray method, aiming for the most even application. The main lessons from this process were that pure clay, taken straight from the ground, is not always the most suitable material. Bacherplatz clay requires a lot of experience and patience, and the long drying time could discourage those making commissioned ceramics. However, it’s fine particle size and high plasticity suggest that it could be a great plasticizing addition to other clays. High stability and fine grain might tempt to use it on the pottery wheel, especially with a polished surface. Finding the optimal application would require more research and experimentation. Not every artist has the knowledge and time to do this, so it is understandable that they choose to buy material that is already prepared and standardized. On the other hand, this challenging clay body performed amazing used as a glaze on stoneware. Besides a set of plate and bowl that got produced, we experimented with making an airbrush gradient on a vase. It turned out that what we found in Bacherplatz is a great deep brown glaze taken straight from earth. Further glaze tests involving addition of calcite, rutile and cobalt oxide resulted in a broader spectrum of colors.

Figure 24. Pottery made from Bacherplatz and Karlsplatz clay

Figure 25. Pottery made from Bacherplatz and Karlsplatz clay

Figure 22. Bacherplatz slip with addition of calcite, used as a glaze.

Figure 24. Pottery made from Bacherplatz and Karlsplatz clay.

Figure 25. Stoneware pottery glazed with Bacherplatz slip