3 minute read

Urban clay – local clay?

from Urban Clay

by mizajn

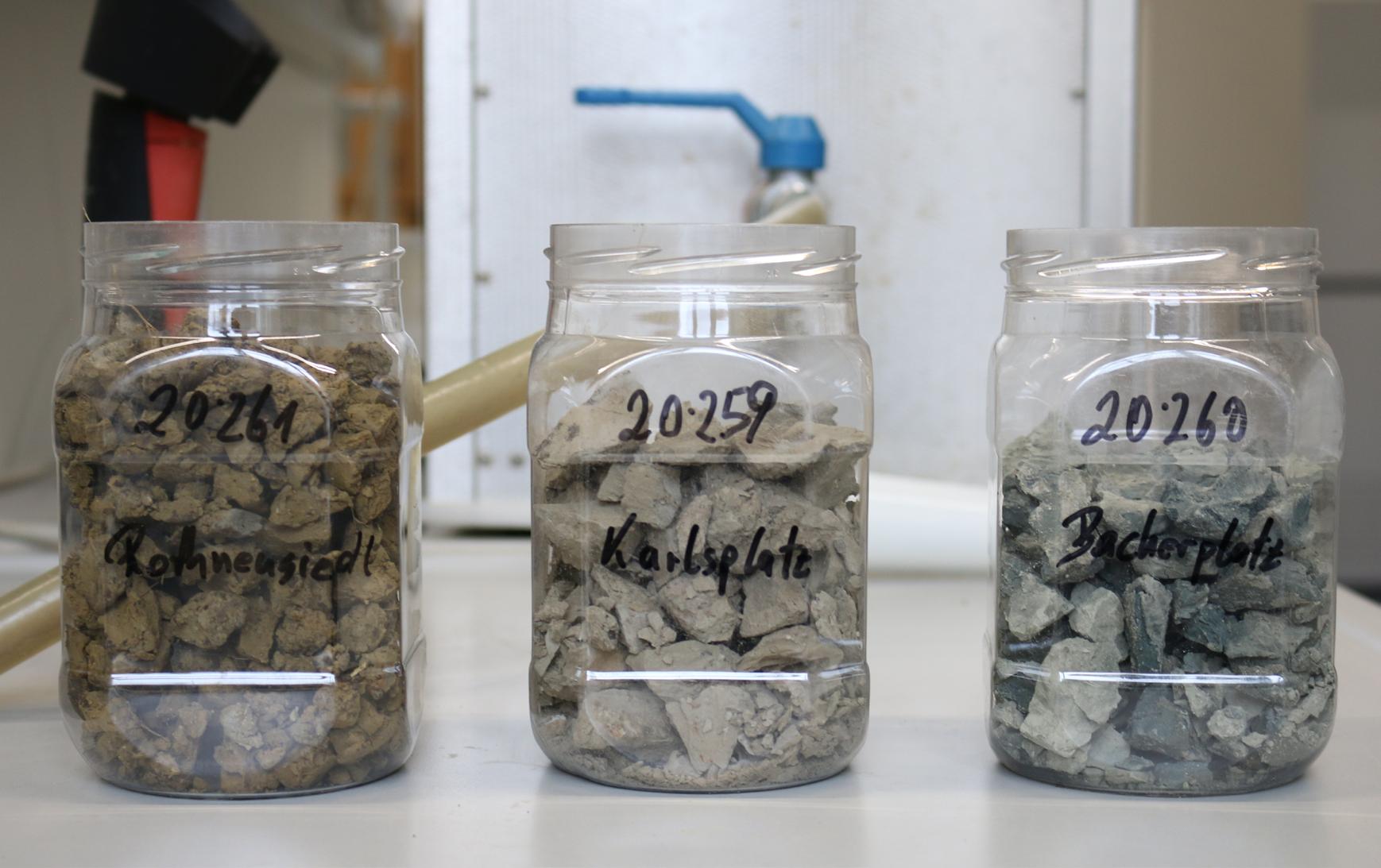

objects, including ceramic ones, are being excavated, cataloged and mapped. One of the main actors playing a role in the excavation processes in the city is construction work. Vienna is rapidly growing, and busy construction sites are a very prominent element of its urban landscape. Works related to building the new metro line U5 cause excavation of massive amounts of soil, a high percentage of which is clay. If the material doesn’t get incorporated at the site, sadly, it ends up in a landfill at the outskirts of the city. In the Urban Clay project, me, Michalina Zadykowicz, and Sabrina Haas, discuss the possibility of Vienna as a mine for anthropogenic and natural resources. Mapping Vienna’s underground clay deposits and overlaying them with planned construction work we track the urban mining which is bound to happen in the upcoming years. We propose a future in which there is a system in place that allows Viennese clay to re-enter local arts, crafts and industries. Looking at the coincidental clay excavation at construction sites from a potter’s perspective, we attempt to make first steps in material research of urban clays, their properties and usability for ceramic artists. We position ceramics as a medium to imagine a more sustainable, local future of the city.

Using locally sourced clay is not a recent concept. Potters’ workshops were usually founded next to the material deposits, which determined the regional qualities of the ceramic products. Nowadays, materials used in pottery are in most cases a byproduct of large-scale industrial mining. Globalization and low transport costs made raw materials from all around

Advertisement

the world widely available for artists and craftspeople. In the year 2019, the top exporter of clay was the United States, followed by China and Germany. The top importers were Italy, Germany and the Netherlands.2 No one is anymore surprised at seeing minerals – literal powdered rocks – that were mined in Canada in a ceramic atelier in Austria. The majority of blue color decorations on pottery, such as for example the famous Delft Blue, are made using cobalt oxide, a byproduct of cobalt ores mining for the smartphone industry, most of which is happening in the Democratic Republic of Congo.3 Ceramics truly reflect the availability and value of resources.

With such a great selection of materials at their fingertips, artists often choose to buy pre-made ceramic masses from manufacturers. Ready to use right out of the package, they speed up work drastically and provide consistent material properties. The ingredients of said masses may be locally sourced, but are often imported as well, depending on the intended purpose of the clay. For instance, one of the main components of porcelain is kaolinite, which occurs naturally in Austria in negligible amounts, but is often imported from Germany. A few enthusiasts choose to search for and dig up wild clay on their own, but the process of preparing it for use is very laborious and timeconsuming, which discourages many professionals, especially those who rely on the ceramics as a source of income.

The city of Vienna lies in the Vienna Basin, a fairly young geological formation of tectonic origin. It is a sinkhole between the Carpathians and the Alps. In the Neocene, the existing sea left filled a layer of sediment up to 5,5 km deep. The top layers of those sediments within the city borders consist mainly of clay, slit and sand, partially covered by the gravel brought later

by the Danube River.4 Therefore, from a geological standpoint, Vienna is very rich in clay. In the past, there were many brickyards operating in places like Wienerberg or Laaerberg.5 They highly contributed to the growth of the city. Most of the historical sites no longer exist, but clay deposits under them remained. However, the industry and material excavation changed the landscape of the city significantly. Transformation of post-industrial areas in Wienerberg and Oberlaa led to the establishment of recreational zones with artificial lakes in the closed clay mines and to reforestation. During a walk in the Wienerberg park, one can still notice slippery clay-rich soil and occasionally find old bricks scattered around.

Figure 1. Detail of bird’s eye view with historical brickyard in the Bacherplatz area .