NEW DESIGN-LED EDIT FROM THE KNIGHT TILE COLLECTION.

Wood, stone and marble floor designs, launching August 2025.

12 Upfront Projects, products and people through a future-centric lens.

22 Things I’ve Learnt

Associate director at M Moser France Gain shares five insightful lessons from her personal journey in design.

24 The height of design Sisters and founders of Kapitza, Petra and Nicole Kapitza, reveal what represents the epitome of design for them.

26 Living Better

Architect, researcher and multidisciplinary Artist

Itai Palti speaks to designing for openness in times of polarisation.

28 In conversation with: Flaviano Capriotti

The leading architect on designing for our times, problem solving and the scourge of Instagram.

36 In conversation with:

Studio Truly Truly

We sit down with Netherlands-based practice

Studio Truly Truly to discuss taking risks and staying fascinated.

44 Colour Story

Colour expert and author of The Colour Bible

Laura Perryman on designing for joy and neuroinclusive spaces.

46 Case Study:

A by Adina Vienna

The first from the aparthotel brand in Europe, the BWM-designed property brings Australia to Austria.

52 Case Study: Jamie Lloyd

2LG Studio creates a home away from home for theatre director Jamie Lloyd at the prestigious Somerset House.

60 Case study: Reed Smith

At global law firm Reed Smith’s London HQ, tp bennett explores the art of the possible.

68 Case Study: Dock Shed

Conran and Partners, together with Allies and Morrison, crafts a workplace in London’s first new town in over 50 years.

74 Case Study: Flint HQ

Nodding to terroir, Mowat & Company designed a new-old workspace for wine merchant, Flint.

80 Building Narrative Co-founder of art consultancy, Artiq, Patrick McCrae muses on a summer centred around optimism.

82 Positive Impact

Likening design to zerowaste cooking, Mitre & Mondays regard ‘waste’ as a fundamental system failure.

88 Fast Forward

We explore the role of space, objects and ideas can play in creating a more optimistic future.

94 Mix Roundtable with Specialist Group

We speak to the rise of artificial intelligence and its potentially seismic impact on the commercial interior design industry.

102 Mix Roundtable with Milliken

A discussion on the transformative power of reuse and how it can guide a new approach to design and the built environment.

110 Mix Awards 2025

Looking back on the industry’s biggest event, we remind ourselves of the lucky few who took home the trophies.

136 Mix Talking Point: What do Gen Z want?

We look at the return to analogue for the digital generation.

140 The Making of: Pedrali

Six decades in, Italian furniture manufacturer Pedrali continues to stay true to its roots of local production and Italian craftsmanship.

144 Material Matters Director of materials research design studio Ma-tt-er, Seetal Solanki selects which materials have made the most impact on her life and work.

145 Material Innovation

Creating a new purpose for London’s discarded coffee cups, Blast Studio’s Cupsan interprets waste as a ‘neo-vernacular’ resource.

146 Innovative Thinking

M Moser’s Steve Gale on the difference between technology and engineering.

All designs, in all colours manufactured in 10 days PLAY TO CREATE

Get in touch

Managing Editor Harry McKinley harry@mixinteriors.com

Deputy Editor Chloé Petersen Snell chloe@mixinteriors.com

Editorial & Social Executive

Charlotte Slinger charlotte@mixinteriors.com

Editorial Assistant

Ellie Foster ellie@mixinteriors.com

Managing Director

Leon March leon@mixinteriors.com

Account Manager

Stuart Sinclair stuart@mixinteriors.com

Account Manager

Patrick Bowley patrick@mixinteriors.com

Account Manager Gaia Cafarella gaia@mixinteriors.com

Marketing Manager Paul Appleby paul@mixinteriors.com

Head of Operations Lisa Jackson lisa@mixinteriors.com

Advertising and Events Operations Manager Maria Da Silva maria@mixinteriors.com

Art Director Marçal Prats marcal@mixinteriors.com

Founding publisher Henry Pugh

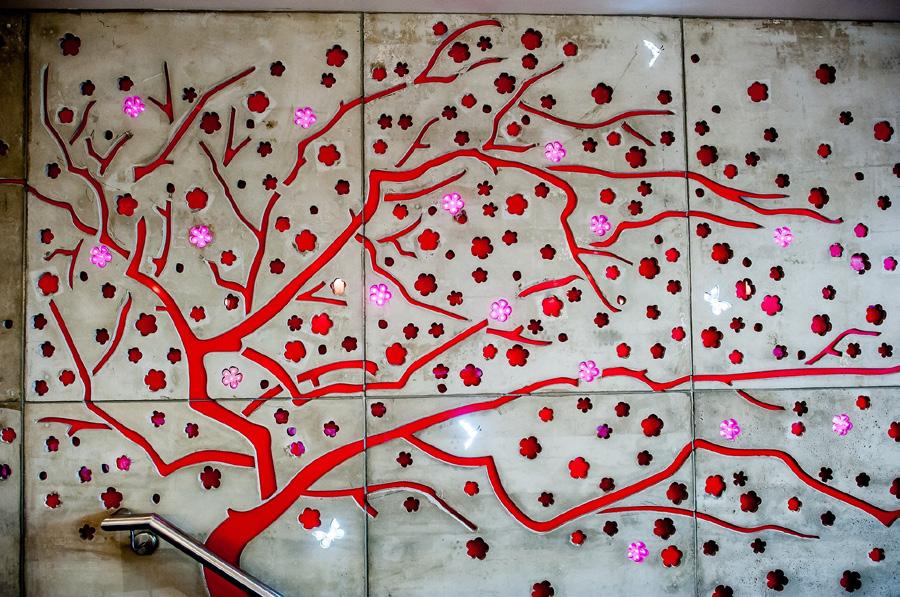

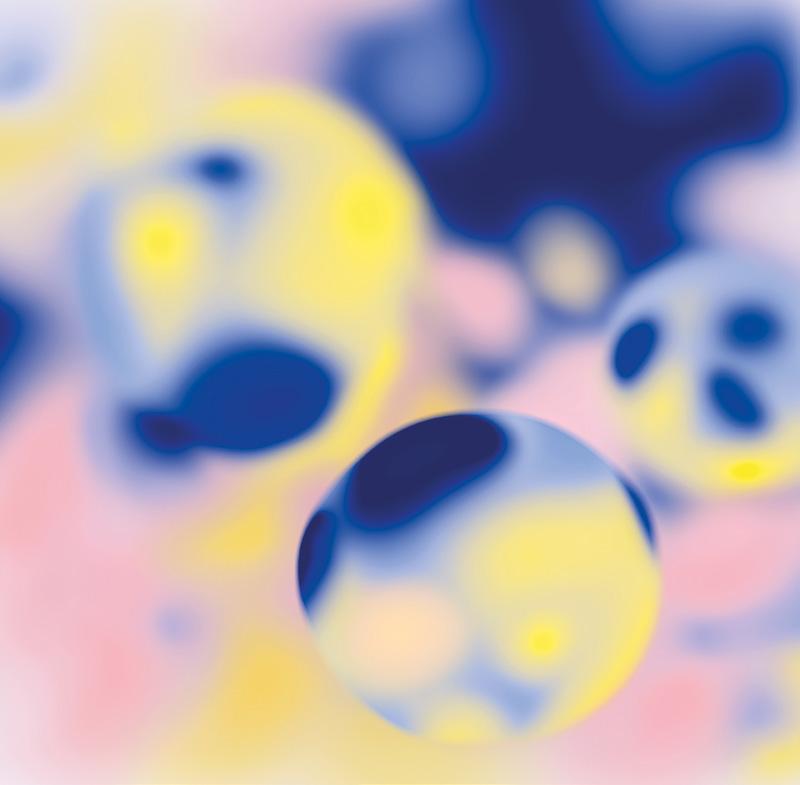

Office S&M Architects created a sensory experience that invites curiosity and discovery, drawing design cues from the calming qualities of sensory toys. Intended to feel both calming and energising, the design reflects the productive, playful environments the London-based practice is known for. Inspired by Karndean’s approach to neuro-inclusivity, the cover pairs a soothing yet strong colour palette with diffuse forms and sharper elements to evoke both hyper- and hyposensitivity.

officesandm.com

This year, Karndean introduced its CPD seminar Designing Neuro-Inclusive Environments, responding to the growing need for inclusive design. With one in seven people identifying as neurodivergent, the seminar provides critical insights into how flooring choices and spatial design supports cognitive and sensory wellbeing. By raising awareness and equipping designers with practical tools, Karndean hopes to shape more accessible, empathetic spaces for all, blending inclusivity with functional design intelligence.

karndean.com

To ensure that a regular copy of Mix Interiors reaches you or to request back issues, call +44 (0) 1161 519 4850 or email lisa@mixinteriors.com

Annual Subscription Charges UK single £45 50 Europe £135 (airmail) Outside Europe £165 (airmail)

Unit 2 Abito, 85 Greengate, Manchester M3 7NA

Telephone +44 (0) 161 519 4850 editorial@mixinteriors.com www.mixinteriors.com

Instagram @mix.interiors LinkedIn Mix Interiors

At the recent Mix Awards 2025 (revisited on p112) one of the judges seated at my table exclaimed, “you must be wonderful to work with, you’re always so positive”. I can only imagine the guffaw this would generate from some of my colleagues. Not because I’m a tyrant, but simply because I’ve never been one to believe anyone can exist in a state of permanent, performative joyfulness. Those that try? Well, it’s all just a bit annoying, isn’t it. No no, that wasn’t a question.

Yet while I don’t subscribe to a Hallmark-approved view of ceaseless cheerfulness, the pursuit of happiness is a recurring theme this issue. Whether as an antidote to a doleful global climate or as a response to the rise of AI (and all the ways we’re losing touch with the innately human), we’re increasingly looking at the role design can play in creating a more positive society. It’s the basis of this issue’s Fast Forward feature (p88), which explores if we can design our way to a happier future, and the foundation of two of our columns: with Laura Perryman charting the ways in which colour can breed optimism (p44) and Patrick McCrae asking if designing the arts into our spaces can support wellbeing (p80).

It’s also a motif that runs through our Mix Roundtables. With Specialist Group, we ask how AI can complement not replace human expertise (p94) – one of our guests mulling on whether more time (freed up by AI) will actually bring us more joy. While with Milliken, a discussion on reuse challenges us to think what ‘better’ looks like, if ‘more’ is no longer sustainable.

Across our case studies –from a workplace for a law firm to a Vienna aparthotel (from p46) – the desire to devise places that provoke delight and contentment reflects a changing design sensibility. It isn’t, perhaps, enough that environments work hard and look great, they should make us feel better – inhabit them not because we need to, but because we want to. Speaking to this same notion, our cover, with Office S&M and Karndean, is a statement on neuro-inclusivity and the ways in everyone should be able to enjoy spaces (more on that on p148).

So am I always ‘so positive’? Well, no. But if this issue is anything to go by, maybe design has the power to change that.

Harry McKinley Managing Editor

brunner-uk.com

Welcome to our public promise and a transparent account of our mission. This manifesto is a living document, an invitation to explore the systems, data, and partnerships that define our commitment to engineering a truly circular future for the acoustics industry. For us at Impact Acoustic, sustainability is the core of our business, the catalyst for our innovation, and the metric by which we measure our success as one of the world’s leading acoustics brands. We started Impact Acoustic to prove a simple but radical idea: that the world’s waste could be the raw material for a beautiful, functional, and sustainable future.

We’re here to redefine what’s desirable—elevating new materials, reshaping circularity, and setting a bold new template for the architecture and design world. This isn’t just a sustainability policy; it’s our promise, our passion, and the blueprint we live by.

founders, impact acoustic

1. radical materiality

2. designing for longevity

3. total transparency

4. strategic collaborations

5. united nations sustainable developemnt goals

6. the eco-warriors within

7. engineering tomorrow

8. partner and client enablement

It’s eye-catching. It’s honest. It’s a never-ending sofa, challenging the concept of sustainable public seating. Combining simplicity and versatility with unmatched durability for an endless seating experience.

Offering traditional opera, concerts and experimental performances, Shanghai Grand Opera House is set to be a major cultural landmark for the Chinese metropolis, opening its doors late 2025 Designed to captivate a diverse audience, the principal intention with the space was to engender a sense of public ownership through impressive – not oppressive –architecture, enticing open spaces and 24-hour visitor access.

Selected in a 2017 international design competition, Snøhetta’s proposal –encompassing architecture, landscape and interiors – comprised a robust architectural concept with an equally vigorous spatial strategy; one that

prioritised community-centric design and welcomed visitors, not just from Shanghai, but from all four corners of the globe. Allowing public right of way at all hours, 365 days a year, a sprawling plaza converges with a sculptural helical surface – a stage-cum-stairway that winds into the sky, inspired by the dynamism of the human body.

Located in the neighbourhood of Houtan along the Huangpu River waterfront, the radial roof will become an accessible stage and meeting place, presenting opportunity for large-scale, open-air events as well as the coalescing of artists, local people and tourists alike. Another key priority for Snøhetta – alongside

partners East China Architectural Design & Research Institute (ECADI), Theatre Projects and Nagata Acoustics – was that the overall geometry of the building harmonised with the surrounding landscape, solidifying the connection between the opera and the city with direct view paths at all angles.

Founding Partner of Snøhetta, Kjetil Trædal Thorsen comments, "The Shanghai Grand Opera House is a product of our contextual understanding and values, designed to promote public ownership of the building for the people of Shanghai and beyond."

snohetta.com

The award-winning RAK-Des collection is inspired by Bauhaus design principles and features minimalist sanitary fixtures, including countertop and freestanding washbasins with clean, sleek lines. Now available in a range of matt colours – Black, Grey, Cappuccino, Greige, and White.

Guarding ‘the gates’ to one of Manchester’s most lively districts, Northern Quarter, a mud-brown multi-storey from the 1970s sits monolithic, but somehow largely ignored by visitors making a beeline for the popular bars and restaurants of Stevenson Square and Thomas Street.

Replacing what council leader Bev Craig describes as ‘an eyesore and a barrier to the ongoing success of the Northern Quarter,’ the car park is scheduled for demolition later this year. A new development will replace the existing structure, posing a much more appropriate arrival sequence to the centre’s most highly trafficked areas; one that will become a natural part of the neighbourhood’s offering.

Manchester City Council marketed the Church Street site for clearance in 2024 and, following a competitive process, it was decided that developers Glenbrook Property would oversee the

transformation of the 1.54-acre plot, subject to formal decision making and planning permission. With design by Tim Groom Architects, the proposal is set to deliver more than 300 new apartments with 60 (20%) being affordable homes, providing accessible opportunity to live on the cusp of the quarter.

At street level, commercial space will offer a mix of smaller, affordable units to ensure that the local independent businesses that characterise NQ can still access the neighbourhood – alongside a new flexible community and gallery space.

Also central to Glenbrook’s plans, four new squares and significant urban greening will align with Manchester City Council plans to pedestrianise the surrounding streets to uplift the new mixed-use development, while supporting scenic and safe travel options to and through the area.

One of the furniture industry’s greatest environmental challenges is the widespread use of polyurethane (PU) foam – a petrochemical product that relies on isocyanates as a catalyst during manufacturing. PU foam off-gases harmful chemicals, is highly flammable and, due to its limited lifespan, cannot be truly recycled – only downcycled. Ultimately, it ends up being incinerated or, worse, polluting our oceans and landscapes.

Designed by Copenhagen-based designer Boris Berlin in collaboration with +Halle® and German textile technologists Krall+Roth, SHRINX is a protest against material overuse, proposing to product designers that luxury design isn’t always synonymous with ‘more.’

The antithesis of traditional upholstery, Krall+Roth developed SHRINX 4903 to be a semi-translucent mesh, crafted from 68% polyester and 32% polyamide, which is then draped around the SHRINX steel frame and shrunk to size. Conceptual designer Boris Berlin explains, “Normally, when you apply textile to be stretched, you must stretch more fabric than what is in use. With the SHRINX Lounge Chair, you apply a loose piece of pre-sewn textile cover, place it neatly in the groove or tunnel of the frame, and then apply heat, allowing it to reshape in its entirety.”

Berlin’s pairing of a stocky club chair typology with the gauzy nature of SHRINX 4903 not only curbs environmental impact but is a direct response to the rise of ‘soft privacy.’ Inspired by Shiro Kuramata’s How High the Moon chair, made for the Memphis group in 1987, the overall design of SHRINX responds to recent shifts in both sustainability standards as well as human behaviour in contemporary public spaces – to be both alone and amongst people.

krallroth.com

plushalle.com

Two end-of-life office buildings behind London’s Victoria Station – including a former 1975 cash depository – are due to be transformed into new sustainable workplace, The Langfield, meeting the increased demand for modern and adaptable workspace in the area. With design by tp bennett, 80,000 sq ft of floorplates will be subdivided for multitenancy, with street level units given over to an onsite café with access to a ‘pocket’ park. Four private rooftops will be available for tenants with ample integration of biophilia.

Spread across eight floors, The Langfield retrofit repurposes original construction where possible, however the compromised nature of the site’s Gillingham Street elevation has prompted the design team to carefully consider alternatives to the building’s aesthetics, MEP systems and material specifications to reduce both embodied and operational carbon in the development.

Striking a steady balance between heat loss, heat gain and solar comfort, the distinctive new façade synergises with the style of the 70s build visually, whilst bridging the technological gap between

the existing building fabric and newer materials. Because of this precision-based patchworking, the building will achieve an embodied carbon of 600kgCO2e/m2 and whole-life carbon of 950kgCO2e/m2, outperforming GLA embodied carbon targets. The optimisation not only brings about a reduction in energy consumption but also significantly enhances interior comfort levels for tenants and those utilising the F&B spaces at ground level.

The combined buildings now fulfil the area’s need for flexible workspace while swerving the wrecking ball.

Fin. Modular and linear, with a deceptively simple design, a Fin table brings refinement to the meeting room. With sleek elliptical steel legs, the fin frame changes its profile depending on your viewpoint, always maintaining its clean and simple lines.

Recent and rapid urbanisation has had Hanoi in its clutches, with hundreds of inner-city factories scheduled for demolition. Making way for modern residential blocks and office units, these 20th century heritage structures are more than mere production spaces – they shaped the everyday life of their original users and are responsible for the neighbourhoods that settle around them today.

Initially built as a mechanical depot where train locomotives underwent maintenance, Gia Lam Train Factory is but one of many facing the risk of erasure; the pressure of redevelopment threatening to erode the collective memory and socio-spatial dynamic of the Vietnamese capital. Recognising

this, the Hanoi-based Trung Mai / Ad hoc Practice has transformed the abandoned warehouse into a semipermanent exhibition space, serving as both a cultural landmark and a preventative measure against the actions of urban developers.

Inside, The grid acts as a ‘memorial’ to a bygone industrial era, while relating to the socialist architectural theory of gridded formats fostering equitable and efficient cities. Metal grating delineates the floorplate in a nod to the famed Eixample district in Barcelona designed by Ildefons Cerdà in the 19th century, where furniture is fashioned from ammunition boxes dating to the Vietnam war, discovered within the factory. Art

objects were also crafted using reclaimed fragments from the warehouse, such as industrial ventilation ducts and other salvaged materials.

An example of elevating forgotten spaces into vibrant cultural showcases, The grid stands as a testament to the enduring relevance of mindful urban planning and preserving Hanoi’s cultural heritage for generations to come. Visitors of the exhibition are encouraged to critically examine the repercussions of modern construction methods, retrofitting processes as well as consider how the site could further support collaboration within the local community.

adhocpractice.com

Explore the depth, dive into the craft. Lasting Impressions™ brings ancient ways to modern spaces.

In Heirloom™, the textures of tatami weaving make for a fresh take on tradition. While Plaster™ takes inspiration from handfinishes and natural patinas.

Two heritage styles, each drawing on crafts handed down. And your chance to take these legacies and make them your own.

For more information:

+44 (0)800 313 4465

ukcustomerservices@interface.com interface.com

Frances Gain is associate director at M Moser –blending her diverse background in marketing, architecture and academia to develop future workplace and design strategies, from change management to cultural mapping.

mmoser.com

@mmosersocial

Everything matters, but nothing actually matters. This is a mantra I've picked up along the way, which I say regularly to the team. What I mean by this is that the small things – the details, the wording, the page design – really do matter, especially when presenting work to clients or speaking with leadership. We care about getting them right. But the paradox is that they don't matter quite as much as we think. Will that typo or the phrasing of a headline make or break the whole presentation? Probably not, but it's still worth addressing. It's about developing a mindset that everything you do matters –so start strong and care about the work, but don't let the pressure overwhelm you. Care deeply but don't stress unnecessarily.

Do what you're good at.

Figure out your strengths, skills and passions, then focus on those. Seek out projects, roles and environments that align with your unique skillset. This will set you up for success far more than trying to ‘fix’ what you can't do.

I've assessed my skillset; I know what I'm good at and what I'm not. I'm comfortable expressing this to others – my boss, my peers, the team – and I make sure that most of my time and energy is spent in those areas. All while staying humble, staying hungry and learning every day. As a new(ish) parent, I've heard the rhetorical question: "If your child was good at tennis and bad at math, would you hire a tennis coach or a math tutor?"

If you want to go far, go together.

I'm proudly South African and there's a beautiful Ubuntu saying: "If you want to get somewhere fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together." Sometimes, collaborating with others feels harder and slower. I often catch myself thinking, this would be quicker if I just did it myself. Delegating, coaching, sharing and reviewing takes time and effort. As someone naturally quite independent, learning to step back and let go was a challenge.

But, over time, I've prioritised learning how to co-create through clear communication, iterative feedback and empathy – and the long-term benefits have absolutely paid off.

You don't need to know what you're doing when you start.

At any scale! I've worked across several fields – marketing, architecture, academia and now workplace strategy and change management. If there's one thing I've learnt it's that you don't need to have it all figured out before you begin.

On a project level, part of our role as consultants is to uncover the problem and figure out the solution. You can't wait for clarity to begin – you start and clarity follows.

During my yogi years, I had a phrase written on a chalkboard that's stuck with me: "As you step onto the journey, the path will appear." It turns out we can figure out many things if we're willing to just begin.

Sometimes, it's better just to keep quiet.

Kapitza is a visionary art and design studio founded in 2004 by sisters Petra and Nicole Kapitza. Known for its bold use of colour and geometric art, the East London-based studio creates large-scale murals, vibrant public art, uplifting hospital installations and joyful placemaking projects that invite connection and inspire wellbeing.

kapitza.com

@kapitza_studio

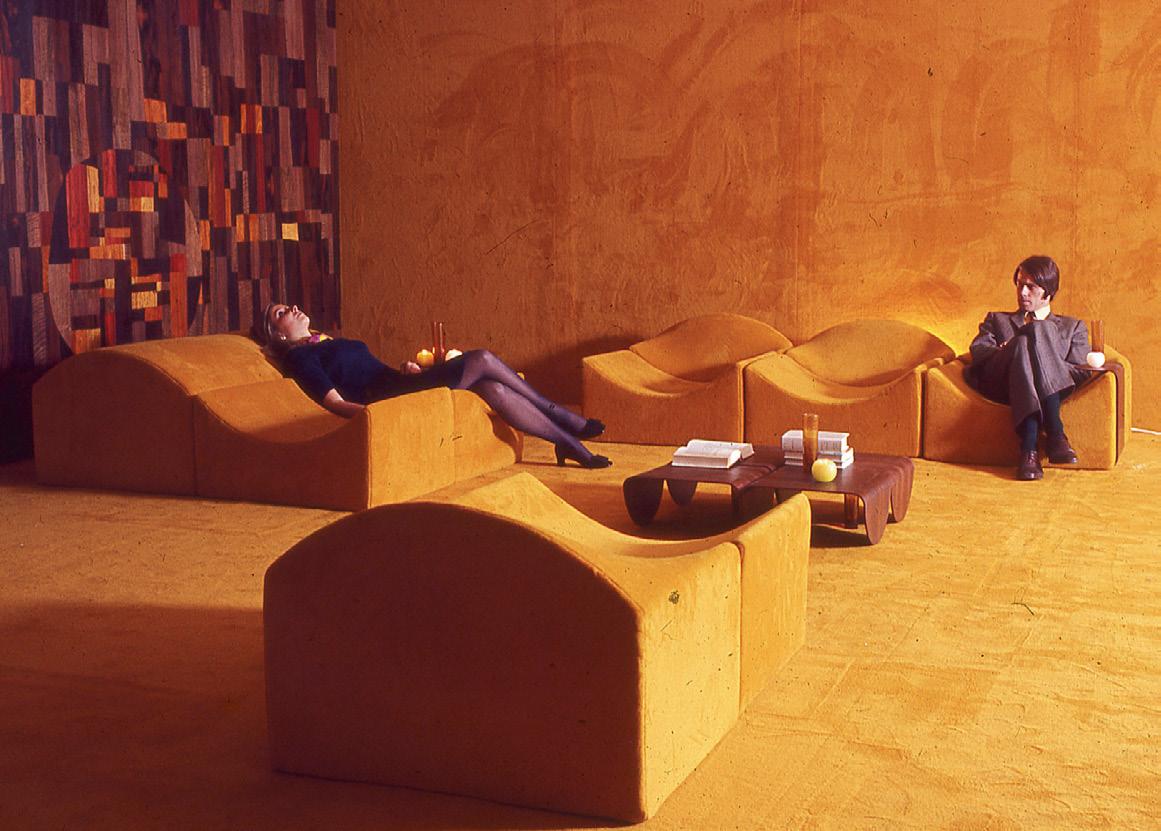

The item

The Togo sofa by Michael Ducaro.

why

The Togo sofa represents the height of design for us because it gave people a new way to interact, both with furniture and each other. When Michel Ducaroy first designed it in 1973, most furniture was stiff and formal – Togo’s soft, low and inviting shape was a revolution. Bold and cosy, it invited people to relax and connect in a more casual, comfortable way that matched the free spirit of the 70s. It showed that comfort and great design don’t need rules or formality. For us, it captures the heart of humancentric design: bold, cosy, timeless and made for real life.

The inspiration

This piece shows that bold design can be both daring and also deeply thoughtful. Initially met with scepticism, Togo became an icon, reminding us that to create something truly groundbreaking we must push boundaries and challenge norms in our work. We love how the Togo’s design is strong and bold, yet playful and soft to the touch.

impact

Togo challenged design norms by introducing a more informal, flexible approach to living spaces. As a cultural icon, it bridges high design with everyday comfort, inspiring generations of designers to focus on emotional connection and how spaces feel, rather than adhering to rigid formalities. Its impact is clear: the Togo sofa helped to redefine what makes a space truly liveable.

The personal connection

We’ve lived with our Togo sofa for over 10 years now and we still absolutely love it. We remember being nervous about investing so much in one piece, but it’s been completely worth it. It’s our favourite object in the house – cool, timeless, comfy and genuinely a joy to use every day. Togo is more than just a sofa, it’s part of our life and a quiet stand against disposable culture. We’ll keep it forever.

In an era where even benches and bins seem to carry ideological weight, public and commercial spaces are increasingly designed not just to serve, but to signal. But when spaces become too symbolic to be lived in, what’s left for those who simply want to feel welcome?

Place is often treated as a medium for values, a chance to showcase commitment to justice, sustainability, heritage or identity. That’s not inherently wrong. But when political messaging dominates or reflects a single worldview, it risks excluding the very communities it’s meant to serve. Worryingly, the idea that “there’s no such thing as neutral design” has spilled from matters of health and comfort into the aggressive politicisation of shared spaces.

In commercial environments especially, where a diverse mix of people pass through, over-politicisation can act like a gate; subtle to some, glaring to others.

Public environments and commercial spaces thrive on openness. It’s what turns a plaza into a favourite spot, or a high street café into a second home. But attachment rarely grows in places that feel like

they’ve already made up their mind about who belongs there. When a space declares itself too strongly, whether through corporate branding, political symbolism or social messaging, it leaves little ground for belonging to take root.

Ironically, this is often most evident in places trying hardest to “stand for something.” A retail park plastered with slogans about community can still feel sterile if the messaging feels imposed. A shopping centre decked in activism might alienate those it’s trying to welcome if the sentiment feels hollow or, worse, performative. Many public spaces have also too easily submitted to loud, extreme minorities who seek to exclude and politicise the shared realm.

Depoliticising space doesn’t mean scrubbing it clean of meaning. It means designing spaces that allow for difference without demanding allegiance. Environments should invite people to inhabit their own identity, not perform one. The most successful examples often feel effortless: a market square with places to linger, a bookstore with no agenda beyond comfort and curiosity, a plaza where protest, play and pause can coexist without contradiction.

This doesn’t mean designers or developers should abandon ethics or impact. Quite the opposite. The most inclusive environments are those where values are structural, not symbolic, where accessibility, safety and comfort are built into the bones of a place, not pinned on as statements.

Still, that may no longer be enough. Today’s social landscape suggests we need protection from ourselves, and perhaps the built environment can play a role. We must design spaces that repel tribalism, that reject aggression and hate. Can we create places so deeply inclusive that they overcome our own failures in empathy?

Belonging isn’t a design language, it’s a condition we create. It emerges where people feel safe and free in their identity. It means resisting the urge to brand ideology onto every surface and refusing to let space be appropriated as another battleground.

In a world full of signals, sometimes the most radical thing a place can do is stay quietly confident and resolutely welcoming to all.

Words: Harry McKinley

Photography: Courtesy of Flaviano Capriotti Architetti

Architect Flaviano Capriotti discusses changing the face of luxury, designing for the times we live in and why he doesn’t care about Instagram.

I first met Flaviano Capriotti in Milan, during the city’s Design Week; a small industry dinner at the Park Hyatt, which he designed. I arrived on time, but barely, fatigue setting in as I entered the latter hours of a day stretched thin. Each year, for this week in April, Milan swells as countless thousands of industry professionals coalesce on the city, schedules creaking at the seams. At times, the sheer volume of displays, activities and events sees them blur into one creative mass; live talks increasingly perfunctory, even laboured, as the days roll on and discussion points are rehashed. The week is undoubtedly a vital showpiece, but stressing under the weight of its own importance, and the pressure to see and do, it can fail to stir a crucial aspect of design: joy.

This was thrown into relief when I met Capriotti. Introductions out of the way, he quickly launched into an impassioned treatise on the delights of Italian culture, his passion for creating spaces that evoke meaning and, on a personal level, his enduring gratitude for a career doing something he loves. During breaks between cocktails or courses, he led me by the arm to point out design details in the hotel’s restaurant – speaking with infectious enthusiasm about the rationale of a colour choice or a tile. He was joyful.

When we join each other to speak more formally, months later, that same zest is present from the off – Capriotti in his Milan office, flanked by books. “I could talk all day,” he announces, laughing, “until a beer this evening.” Half wondering if I should nix a subsequent meeting, I believe him.

Image on previous page: Flaviano Capriotti

Above left:

Park Hyatt Milano, image Leo Torri Studio

Below right:

Park Hyatt Milano –Monte Napoleone suite, image Leo Torri Studio

Capriotti leads a prolific practice, Flaviano Capriotti Architetti, but his glee for design and architecture started at an early age. He recounts sitting in a traffic jam aged four or five and, instead of bemoaning the wait, wondering why the whole kit and caboodle hadn’t been devised differently. What if the road had more lanes? What if the cars could fly? At this suggestion, his father – a telecommunications engineer – began to explain the basics of aerodynamics, detailing what makes the chassis of a car different from that of an aeroplane. He was enrapt, realising not only that the wildest ideas can be rooted in some notion of reality, but that design itself is about solutions to problems.

“So I was always inventing and creating,” he explains, “but I was drawn to architecture because there was some understanding there – of what makes a building good – that I hadn’t grasped; that no one grasps until they study.

Most of us can understand if someone is elegant, well-dressed, or casual. We have some knowledge of those things, but not architecture. People visit an old cathedral and either feel it’s beautiful, or think it must be beautiful, because everyone goes there. But very few people can understand and read architecture; what architects wanted to express and, actually, if a building is well designed or not.”

Capriotti would study architecture at the prestigious Politecnico di Milano, graduating in 1998. The same year he won the XVIII Compasso d’Oro Premio Progetto Giovane (the Young Design prize) for an early project with Kartell. The Compasso d’Oro is sometimes nicknamed the ‘Nobel Prize of design’, and so to win the Young Design version of the award not only marked Capriotti as a prodigious talent, but remains a towering achievement even decades later – and still one of his proudest moments.

“Interiors are almost more important than what’s outside, because that’s where we truly experience buildings, it’s where we live.”

As for understanding architecture, well, Capriotti has some advice. Firstly, though reflecting on the exterior is important, one can never truly know a building –or gauge its success – without stepping inside. “In fact, interiors are almost more important than what’s outside,” he stresses, “because that’s where we truly experience buildings, it’s where we live.” This philosophy guides his practice today – the sense that architecture needs to satisfy a purpose. It isn’t just to be looked at, it’s to be functional and, crucially, it needs to evoke some emotion. “I’m not saying you need a person to cry,” he suggests, “but emotion can be to feel comfortable, to feel connected or to feel welcomed. As an architect, it’s a rarity to design something for yourself and, really, that’s an indulgence, so you need to understand how a building responds to the needs of others.”

Another of his central tenets is authenticity. It’s an overused word in design, but for Capriotti it’s shorthand for a much more complex and nuanced viewpoint – one that weaves together timeliness (and timelessness), a relationship to place and a clear point of view. He lives in a country of monuments and, while he clearly has a deep reverence for the grandeur of the past, good architecture and design, he forces, is about designing for the ‘time we live in’. Cities are not museums, or shouldn’t be. The same should be true of brands and experiences, he feels, which need to bend, flex and evolve to remain relevant – turning his whip-smart invective to the world of hotels.

“Emotion can be to feel comfortable, to feel connected or to feel welcomed.”

“That hotel is the same today as it was 21 years ago, so that’s the real test.”

“One of my most formative projects was the Bvlgari Hotel in Milan,” he says. Capriotti worked on it in his late 20s, during his tenure with Citterio Viel, today ACPV Architects. It opened in 2004. “It’s still a milestone in hotel development and, at the time, we were asked to create something that reflected five-star luxury in a genuinely contemporary way. Up until then, everything felt like a version of Buckingham Palace and there wasn’t really an example to follow, of what a new luxury might look like.” But the seeds of new ideas were being sown in lifestyle hotels, from figures such as Philippe Starck. Even though they didn’t sit in the luxury space, Capriotti saw something in the ‘energy’ they created as a source of inspiration.

Bvlgari Milan was a quiet revolution, then. Though it occupies an 18th-century palazzo, the gilded opulence that had reigned until the early noughties was supplanted with restraint; black Zimbabwe marble, Vicenza stone, teak wood and bronze suggesting sumptuousness, not by yelling for attention but through exquisite precision and craftmanship. Even the entrance, on a private street, is not brazenly signposted – unmarked until the entrance itself, in what has been described as one of the first ‘anti-luxury’ statements in hotel design. Milan became the blueprint for the Bvlgari hotels that followed – from Bali to Beijing, all carrying the same DNA, but with light-touch local

adaptions. “Other than changing some fabrics or some small details to keep it fresh, that hotel is the same today as it was 21 years ago,” Capriotti says. “So that’s the real test. It worked because it was authentic to the time and still is.”

Beyond aesthetics, what Capriotti’s hotel work demonstrates is an understanding that culture shifts. “There wasn’t just a visual style that was old,” he notes, reflecting on how hotel hospitality has pivoted, “there was a service style that was old. The bellmen were dressed so formally they might as well have been policemen, considering how off-putting it felt. You didn’t feel like you could walk in dressed casually. Now the world’s richest people live in t-shirts and jeans.”

Creating comfort and ease in spaces is something that echoes through the studio’s work – be it a luxury hotel, a workplace in Kuwait or a pioneering educational project in Lugano. The McNeely Centre of Ideas and Imagination, for example, part of Franklin University Switzerland (FUS), comprises two distinct but interconnected blocks, one a semi-transparent glass structure housing public and teaching space, and a pigmented concrete residential wing with a façade that suggests the pages of an open book. Its layout encourages intuitive navigation and gentle transitions. It won an Architecture MasterPrize in 2024.

“Creating comfort in buildings is about seeing not just how technology can change the architectural landscape, but how society is changing it,” he says. “Our world is not strict and straight anymore, it’s very soft and it’s very fluid. We want spaces and buildings that can cope with that; flexible and adaptable.”

Not all change is positive though and when talk meanders into the world of ‘Instagrammable’ architecture, he lets out an exaggerated, comical sigh. “What a nightmare,” he wearily exhales. “It’s the opposite of everything I stand for. I was reading the other day that, thanks to Instagram, our attention spans have shrunk to eight seconds – eight seconds is the opposite of timeless. Plus, what we’re talking about here is flattening architecture down into an image, when these are spaces to exist in. If I see on Instagram that you’ve been somewhere: great, I’m happy for you. But what’s important is to meet each other, talk to each other, touch each other. Buildings create that opportunity. I’m an architect, I care about real life.”

“I’m an architect, I care about real life.”

The compressing of a three-dimensional world into scrollable fragments – the distilling of experiences into something to be consumed, not lived – is a problem architecture is unlikely to solve. But, in an attempt to bring things full circle, I wonder how that appetite for meaningful solutions manifests with Capriotti today, in a world that still has traffic jams.

“I like to remind myself of Renzo Piano, who said something along the lines of, ‘when you start a project you enter a dark tunnel’, because you don’t yet have the solutions, even though you have the tools to find them,” he tells me. “And then you

keep walking very slowly, until you see a little light that tells you you’re heading in the right direction. It gets bigger and bigger until eventually you find your way to the end of the tunnel. Or maybe another way of looking at design is like a mathematical process. So, for me, until I have a correct answer, a project is not resolved. But getting to the answer is a wonderful part of design.”

And there it is, the mistakable optimism and love for the craft that, for me, has become defining of Capriotti – the spark of joy we can all strive to kindle, even during Design Week.

Studio Truly Truly’s Kate and Joel Booy on taking risks and staying fascinated.

Meeting as students in Australia, husbandand-wife team Joel and Kate Booy are two people who have grown together both personally and creatively across careers, continents and parenthood – evident in the way they finish each other’s sentences throughout our conversation. Carving out a niche between product design and the experiential, their design practice Studio Truly Truly offers a unique, tactile blend of function and art that has resulted in a diverse international portfolio, working with brands from Ikea to Leolux. “Although we have different personalities, we have the same goal,” says Joel. “We

have different functions and strengths but we’re both interested in well-made things that are really beautiful and functional.”

Former graphic designers frustrated with the limitations of 2D design, the pair upped sticks and moved from sunny Queensland to arty Eindhoven – Joel studying 3D design at the Design Academy and Kate taking on a graphic design job, slowly launching the studio two years later in 2013. A formative moment arrived in a visit from Ikea’s design team, led by Marcus Engman, right before Joel’s graduation. Intrigued by the intricate

Words: Chloé Petersen Snell

Photography: courtesy of Studio Truly Truly

textile work the studio had created for TextielMuseum, inspired by handknitting techniques and produced by the TextielLab's computer-controlled knitting machine, Ikea commisioned an initial project designing cushions. “Because we’re graphic designers, we did around 250 cushion designs,” Joel laughs, “as well as some furniture and objects. These caught [Ikea’s] attention, the cushion project dropped and we were put into the Ikea PS collection. And for us, that was a big deal.” The cushion concept remained an integral key to the resulting sofa – the studio exaggerated standard cushions into cloud-like forms that users can attach to a minimal metal frame. The frame and cushions were sold separately, not only making it easily recyclable, but also allowing for personalisation with any 50cm cushion and essentially futureproofing the design.

Joel graduated – the design work completed for Ikea in 2015 – and the sofa was released in 2017. In the interim, the pair created a few collectible design pieces, typical of Design Academy graduates –Joel gesturing to a cabinet behind him. “It's really difficult to make – a interesting process of marble mixed with hard epoxy to create a really artistic object. But it's such a difficult world because you've got to keep pushing, pushing, pushing. We weren’t like the other younger artists that had the time and financial support; we

“When we get a new project, we often look at the material and our fascination in that material.”

weren’t living at home. We were like, 'shit, we're running out of money'. We realised we needed to find an avenue to be able to be paid for this.”

The studio prepared for SaloneSatellite in 2017, the Daze table quickly picked up by Italian furniture manufacturer Tacchini. The design incorporates architectural shapes and discrete slits through which vibrant colours appear, inspired by observing hazy light escaping from a crack. The metal table was a unique experiment in applying powder coating – a typically Truly Truly exploration of material, form and ultimately functionality.

“When we get a new project, we often look at the material and our fascination in that material,” says Joel. “What's interesting? What would move us if we saw that object? How does it bend and is that interesting to deal with? [For example] the heaviness of an object and how that contrast of

heaviness be given a way to communicate through the object. That’s how we see objects – they should communicate, they should inspire us, or give us a feeling when we see them.”

“It's balancing and tweaking all the different properties of how a material expresses and communicates to us,” Kate adds, “to find that place where it's a little bit surprising or special in some way and makes you look twice. There are areas where we can be more expressive and extreme in how artistic something is, and then there are other times when things need to be more classically functional, and so it might include a little portion of that sort of interesting expression, but in the details or not as an overriding function.”

“I find it very hard to make things that are not functional; I hate them,” Joel laughs. “I have to try and tame myself to not put in too many ‘functions.’”

Below:

Below: VELA is part of Rakumba’s Typography lighting system

Right: The Big Glow light for Rakumba.

Credit: Josh Robenstone

“I find it very hard to make things that are not functional.”

This thread of function isn’t utilitarian by any means – the studio’s work balances the fun and purposeful, with a philosophy of bridging artistic expression with practical application. “We play on this spectrum,” Kate details, “and it’s interesting for us to switch back and forth between the two: how extreme, how familiar.”

The contents of their Dordecht studio speaks to this; converted from a restaurant, it’s a colourful museum of prototypes and intriguing-looking materials. The Grove Vessel, a sculptural vessel made from synthetic resin, plays with opacity and light – details revealed through varying degrees of thickness from which light is allowed to pass through. This experimentation with translucency and light caught the eye of Michael Murray, CEO of Australian lighting brand Rakumba, and was the start of a fruitful and continuing relationship – starting with Typography in 2018, a mix-andmatch track lighting system inspired by the way letters form words. Clearly graphic design still plays an important role; Typography not a direct application but rather an exploration of its underlying principles, says Joel.

A year later, the studio was invited to create Das Haus at IMM Cologne in 2019 – each year the fair invites a designer or studio to create a full-scale, simulated house within its exhibition halls. Studio Truly Truly’s take on contemporary living, Living by Moods, was a departure

from traditional room divisions, instead focusing on creating a fluid living space defined by different mood zones: Active, Reclining, Serene and Reclusive. This experimental approach aimed to reflect the blurring of boundaries in how people live, work and relax, focusing on moods and atmophere over the stictly functional. It was certainly ahead of its time one year before the pandemic. A hero piece, the volumptuously sculptural Press sofa, was a prototype created especially for the exhibition, launching commercially at this year’s 3daysofdesign by Australian manufacturer Design by Them.

At Milan Design Week 2025 the studio unveiled Big Glow with Rakumba – a collection of sustainable and innovative lighting that reimagines the classic glowing sphere. Taking inspiration from a trip to Copenhagen in the winter, the pair were struck by the charming and dark atmosphere of a hotel breakfast room, where soft, warm lights provided skillfull highlights.

“We have such different experiences of light between Europe and Australia,” Kate notes. “[In Australia] you’re embalmed in it for your whole life and then we moved over here and it’s a completely different feeling; it’s an adjustment. We miss that light sometimes, but here it’s much more subtle and refined.”

“We have such different experiences of light between Europe and Australia.”

“We have fun together.”

“And you get to experience it through the use of really functional light,” Joel adds. “[Big Glow] really had to be functional – it needed to really glow, it needed to be flat packed, it needed to be LED and have a functional down light too.”

The collection is distinguished through its use of Australian wool blended with plantbased bioplastic, creating a material that is not only beautiful with natural acoustic benefits, but is also certified compostable. It was a personal project for both the studio and manufacturer – Rakumba’s Murray growing up on a wool farm in Australia, where the product’s campaign was photographed. “Rakumba are so invested and interested that they want to put in that that layer of detail. That doesn't happen a lot,” Joel adds.

Where next? A slew of future projects awaits, from upcoming furniture and lighting launches to experimental projects in marble and textile. The duo have a desire to work with more UK-based brands. “There’s a cultural connection between Australia and the UK,” Joel muses. “It's an ‘island mentality’ – the UK and Australia being sort of separated from other cultures. Over here in Europe we are so much more connected to different cultures of design – Italian, German, we see it all. For example, with Danish design, you often know what you're going to get. UK design is about being contemporary and an exciting mixture of all these other cultures.”

As for sustaining a happy marriage alongside a happy business, the couple’s work-life balance appears to hang perfectly. “We like spending time together,” Kate smiles. “We’re not lone wolves – we have fun together.”

Laura Perryman is a colour designer and forecaster with over 18 years of experience in CMF design across multiple industries. The author of The Colour Bible, she is interested in material and sensorial experiences of colour. She directs Colour of Saying, a UK-based colour and material futures consultancy.

colourofsaying.com

@colour_of_saying

When did we start believing that professional spaces had to be serious to be taken seriously? Walking through countless corporate environments, I've witnessed what I call 'beige fatigue' – endless expanses of clinical whites and corporate greys. Yet something fundamental is shifting. There's growing recognition that our spaces need to do more than function, they need to lift us up.

The conversation around 'happy design' isn't feel-good rhetoric; it's a response to mounting evidence that our physical environments directly impact mental wellbeing and productivity. But what makes one person feel joyful might overwhelm another. This is where neuroinclusivity enters the colour conversation, acknowledging that our brains process sensory information differently.

Recent research reveals that certain colour combinations can measurably boost mood and cognitive performance. Warm yellows stimulate creative thinking, while specific greens reduce eye strain and promote focus. But the magic happens in nuanced layering, creating what I call 'thoughtful colour layering.'

Take a recent studio project at The Eades in Walthamstow, where I designed a guest suite using colour psychology principles. Rather than defaulting to rental-standard neutrals, we created distinct

emotional zones: warm, welcoming tones in living areas with pops of orange, green, pink and blue; while the bedroom embraced moody, high-contrast shades, with dark reds and blues that research shows promote deeper sleep. Neuroinclusive design means providing variety within a cohesive framework.

Traditional accessibility focuses on physical barriers, but neuroinclusivity challenges us to consider cognitive and sensory accessibility. For individuals with autism, ADHD or sensory processing differences, colour intensity, contrast levels and surface finishes significantly impact their ability to thrive.

This doesn't mean bland environments, quite the opposite. In one hospitality project, we created distinct zones: high-contrast, vibrant areas for those who find stimulation energising, and softer sections for those needing respite. The result wasn't segregation but an inclusive environment where everyone could seek out their optimal sensory space.

The business implications are compelling. Research shows that employing warm shades within waiting zones manipulates users' perception of time; customers feel more at ease and stay longer, encouraging exploration before making a purchase. Most significantly, these

approaches attract and retain diverse talent. As workforces become increasingly neurodivergent, creating environments where different minds flourish isn't just ethical, it's essential.

How do we translate this into actionable strategies? The Eades project taught me about creating ‘emotional zoning’ – using colour to define psychological territories within a space. This means designing gentle colour progressions that allow people to migrate naturally to environments suiting their needs.

Consider texture and finish as carefully as hue. Matte surfaces reduce glare for light-sensitive individuals, while strategic reflective accents energise without overwhelming. Layer lighting temperature with colour choices; warmer light makes even ‘cool’ colours feel more inviting.

The most exciting projects I'm working on involve collaboration with neuroscientists and neurodivergent consultants. Together, we're discovering that designing for difference creates richer experiences for everyone. The optimistic palette isn't about forced cheerfulness; it's about spaces acknowledging the full spectrum of human experience.

After all, if colour is one of our most powerful sensory design tools, shouldn't we use it to create environments where every mind can flourish?

Smart, scalable, and effortlessly stylish, Align is our contemporary desking collection designed for the modern workspace.

With a choice of leg styles and a variety of finishes to suit your scheme, Align adapts beautifully to any setting – from focused solo work to collaborative, open-plan layouts.

For the first A by Adina in Europe, BWM Designers & Architects brings a flavour of Australia to Austria.

A certain mythos surrounds Vienna. It’s a city famously swathed in shadow in the 1949 film noir, The Third Man, and the title of Ultravox’s enduring 80s lament – Midge Ure’s cry of ‘oh Vienna’ set to a haunting musical base, the video all smoke-cloaked streets and buttoned-up trenches. Then, of course, there’s its long association with classical music and art, a rarefied cultural aura manifest in its stately architecture and courtly demeanour. By contrast, it isn’t a place one thinks of in relation to towering, glassy skyscrapers; the dusty, sun-worn colours of Australia; or of sipping cocktails in swish infinity pools. And so, in this respect, the recently unveiled A by Adina Vienna is a dash of the unexpected.

A 120-key aparthotel, A by Adina Vienna is an assembly of novelties: the first of the A by Adina brand (from the Australia-born TFE Hotels) in Europe, occupying five floors of the tallest residential tower in Austria, in a location removed from the traditional tourist core overlooking the Danube. In Donau City, one of Vienna’s newest urban quarters, one won’t find gaudy souvenir shops or queues of coaches, instead contemporary high rises, sprawling green space and, on the adjacent Danube Island, riverside bars and restaurants. On a clement summer’s day, locals languish in swimwear by the water, cycle along tree-lined paths and while away the hours on park benches. It’s all a dramatically different vision of Vienna than the more familiar imperial grandeur, but equally enticing and – for visitors – largely untapped.

BWM Designers & Architects led on the interiors of A by Adina, which also sidesteps the usual Viennese tropes. Instead, Australia provides the primary inspiration.

“They [A by Adina] have more of a brand spirit than a brand standard,” explains Erich Bernard, BWM’s founder and managing partner, on the brief established at the outset. “It wasn’t that people should feel like they had arrived in Australia, but that it should establish a connection to the brand’s homeland.”

By virtue of its height (the building stretches to 180m), and the raft of floor-to-ceiling glass, the property innately befitted from bewilderingly panoramic views. And so, as Bernard explains, Vienna was already a constant and inescapable presence; the city’s increasingly eclectic skyline not something he wanted, or needed, to compete with. “Those astonishing views were really [a gift],” he continues, “as it meant we didn’t have to lean too heavily on the Viennese idea; we have Vienna outside, so we don’t have to do Vienna inside. I didn’t want to do another ‘fake’ take on the city – there was scope to do something different.”

Image on previous page: Inside Lottie’s main dining room at A by Adina

Left:

A guest suite lounge area with soft seating

Centre:

Cyclical panoramas from the guest suite kitchenette

Right:

The external elevation and branding

“It’s the best view of the best city in the world.”

Above right:

Dining area and artwork inside a guestroom

Below right: Green tiles characterise guest suite bathrooms

Avoiding pastiche across the board, the antipodean influence isn’t heavy handed but – across the studios and one- and two-bedroom apartments – reflected in materiality, colour and silhouette. An earthy palette nods to dry grass, with muted, chalky green; to the open sea, with deep blues; and to the wide, rolling mountains, with a weathered, sensitive red. “And then there’s the curves,” suggests Barnard, “in the free forms of the carpets, in lamps, in the softness of some of the details. This is really a representation of the Australian landscape, but expressed subtly.”

The apartments vary in scale from a neat 30 sq m to a roomy 96 sq m, but remarkably no two are the same. One of the challenges for BWM – and quirks of the build – was the sheer diversity of the floorplates, necessitating design that could be thematically, if not exactly,

replicated throughout. The studio developed an initial set of 20 broad-stroke room variations and, from those, adapted individually – esoteric corners becoming banquette-lined spaces for morning coffees, narrow through-spaces imaged as reading nooks and expansive outdoor terraces furnished for entertaining. But, still, those common threads: Cipollino marble splashbacks in the compact kitchenettes, robust parquet flooring and artwork by Indigenous Australian artist, Doreen Chapman; in the larger quarters, a few extra amenities, including deep, freestanding Laufen bathtubs.

“They aren’t ‘supermarket hotel rooms’,” details Barnard, “every one is special. And what A by Adina wanted us to deliver is a very particular kind of luxury – not cliché luxury, loud or gold and shiny, but instead understatement as luxury, cosiness as luxury.”

Whether on a shorter city jaunt or a longer stay, saunas, a state-of-the-art gym and that infinity pool, provide opportunity for both activity and respite without leaving the building, while Lottie’s segues from breakfast room and lounge to bar and small plates restaurant by evening.

“What became Lottie’s was only intended to be a kind of living room at first,” notes Bernard, on what is now one of the aparthotel’s defining and most impressive spaces. “Because it was something of an architectural leftover; a difficult room with a shaft in the middle. But it has this incredible view and as the concept for the property kept developing, the opportunity for it to be something more than a living room also grew. So we removed the shaft, which made room for a bar, and the idea of Lottie’s as a proper place to eat and drink was born out of that.”

It’s an undeniably slick spot, unfurling from an unobtrusive reception desk into a comfortable hangout and further onto a planted terrace overlooking the river and into Vienna – landmarks such as the ferris wheel and St. Francis of Assisi Church punctuating the skyline. “For me,” says Barnard, “it’s the best view of the best city in the world.”

Marking its first commercial office project, 2LG Studio creates a home away from home for theatre director Jamie Lloyd at the prestigious Somerset House.

Words: Charlotte Slinger

Photography: Megan Taylor

Image on previous page: The lounge area is awash with natural light

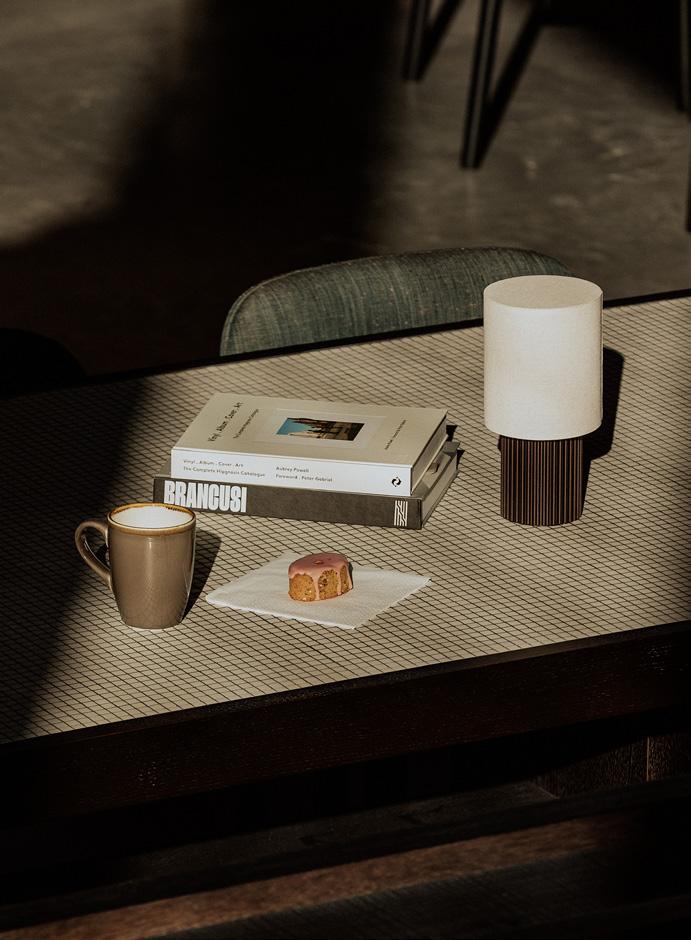

Above: Refreshment station and soft seating

The site of major historical events dating back as far as 1604, Somerset House has been ingrained in the fabric of London for centuries, from hosting treaty negotiations for the Anglo-Spanish War to narrowly escaping the Great Fire of London. In more recent history, the vast neoclassical building has operated as a centre for arts and culture since 1779, hosting exhibitions, festivals and screenings for some of the world’s leading artists. Not many people spend their 9-5 in a heritage landmark like this one, but for staff at the award-winning Jamie Lloyd Company, this is home.

Winner of four Olivier Awards, two Evening Standard Awards and, most recently, the Tony Award for his revival of Sunset Boulevard, this spring director Jamie Lloyd moved his theatre company into the West Wing of Somerset House –for the second time in a year. Soon after the space was first completed in August 2024, it seemed that the building’s past fortune of avoiding fires ran out, and the West Wing caught ablaze. The office and much of the furnishings within suffered significant damage, providing designers 2LG Studio the rare opportunity to revisit one of their most recent projects. Founded by partners Russell Whitehead and Jordan Cluroe, London studio and consultancy 2LG has long been a recognisable name

on the design scene, creating tentpole installations at Clerkenwell Design Week and appearing as guest judges on Channel 4’s Changing Rooms. Known for their distinctive use of colour and joyful, expressive product collaborations, Lloyd reached out to the duo and prompted them to undertake their first commercial workspace. Despite his typically minimalist style onstage, the director envisioned his office with a softer, more homely feel, something that spoke to 2LG’s experience in residential design and styling.

“We both had previous careers in theatre and TV as actors, so this project was hugely significant to us,” say Whitehead and Cluroe. “I think Jamie chose us for this project because he wanted a residential feel to the space and he doesn’t see boundaries between work and home design in many ways – it’s all part of the human experience.”

Occupying a modest footprint of 700 sq ft, the office consists of two adjoining rooms for Lloyd’s small team. The airy, light-filled shared workspace was informed by Lloyd’s beliefs as a practicing Buddhist, with each desk arranged according to his team’s ‘power positions’ – the direction each individual faces for success to flow easily.

“There was also a strong steer to eliminate clutter and reduce the number of drawers, to discourage items being left or forgotten about,” adds 2LG. “It’s all about living in the present moment and not being held back by physical clutter.” Lloyd therefore gave the studio full rein to create a dynamic space for his assistant and close-knit team of young creatives. Against a backdrop of grey-blue walls, a tufted wall hanging with cobalt blue and butter yellow accents smiles down at the central table and mid-century chairs below, a collaboration with Granite + Smoke for 2LG’s exhibition at London Design Festival 2023, ‘You Can Sit With Us’.

Despite moving the office two doors down after the fire, Lloyd wanted much of the original concept to stay the same. “The challenge was to make it feel fresh whilst retaining the atmosphere Jamie loved so much when we first delivered it,” the duo explains. “Changes were small and we tried to save any pieces we could so that there was no needless waste.” For his own office in the neighbouring room, the director wanted the space to feel comfortable yet elevated, with a ‘moodier, Bat Cave vibe’.

Often hosting meetings with actors such as Sigourney Weaver and Nicole Scherzinger, the space had to make an impact, with terracotta-hued walls, Gubi dining chairs, bespoke rugs created with FLOOR_STORY and, at its heart, an enveloping, cloud-like sofa by Phillipe Malouin.

As is the rule in most design lovers’ homes, the ‘big light’ is banned – but not just for aesthetics. The Grade II-listed building has strict parameters as to what can be altered, with the original doors and existing light fixtures out of bounds.

Flooring

Floor Story x 2LG Studio

Westminster Carpets

Furniture

SCP

Ercol

Crystal Palace Antiques

Swyft

Nest

Surfaces

Smile Plastics

Kvadrat (Raf Simons)

London Marble

Lighting

Aram

Flos

Hay

Six Dot

Opting to leave the large, overhead panel lights turned off, the space instead receives a softer, more forgiving glow from freestanding pieces including an abstract Six Dots floor lamp and a Flos Snoopy lamp perched on Lloyd’s desk. The smaller footprint allowed 2LG to fill each room with these tightly curated picks and personal touches, with vintage pieces selected from local gems like Crystal Palace Antiques and display shelves stacked with eclectic vinyls, ranging from Nils Fram to Tyler, the Creator and, of course, the Sunset Boulevard soundtrack. Also drawing from a background in art, Whitehead created custom artwork for the space, weaving in hidden references to actress Betty Buckley – whose West End performance in Sunset Boulevard had a huge impact on the designer as an early teen.

With their first office project now restored to its former glory, can we expect more from 2LG in the commercial sector? “We would love to explore more workspaces and certainly have a passion for designing more commercial spaces going forward,” the duo says. “The challenges are different, but our approach is the same: to create a human space that promotes connection, creativity and growth. It’s why we love what we do.”

At Reed Smith’s London HQ, tp bennett explore the art of the possible.

Words: Helen Parton

Photography: Hufton+Crow

Image on previous page:

Communal kitchen and dining facilities

Below:

Breakout spaces for relaxation and collaboration

ne of the things the client asked was 'are we cool enough to pull it off'; that was their challenge,” says Mark Davies, principal director at tp bennett, the practice responsible for the new home of law firm Reed Smith. We’re standing in the reception of Blossoms Yard, near London’s Liverpool Street, part of a 115,000 sq ft workspace which spans eight floors. As we head to the first floor reception, Davies goes on to explain that the interior “brings in that edge of Shoreditch”.

The legal sector is known more for its cautious approach to workplace design (still clinging on to cellular working when most other industries embraced open plan long ago). So what was tp bennett’s secret in bringing Reed Smith into a new era of flexibility, variety and style?

“We created an area in their old office which allowed them to see the art of the possible,” adds Davies, citing that before 30% of the space was open plan, with 70% cellular but, here in their new office, those figures have flipped. “From a business perspective, we wanted people making connections and working in other environments,” adds Mark Matthews, Reed Smith’s EME Operations Director.

The office is composed of two buildings, Blossom Studios, which was built in the 1890s and the new-build Blossom Yard, which faces onto the main road. The base build, by architects AHMM, has a modern brick warehouse aesthetic with ceramic panels that reference the cladding of what was a showroom for Nicholls & Clarke, a 150-year-old building materials supplier.

Standing in the courtyard of the project, Broadgate Tower, Reed Smith’s former high-rise home, peeps over the horizon.

Image on next page:

“This is not your average corporate tin can,” says Davies, provocatively drawing a comparison between past and present places of work for the law firm. Indeed the theme of old and new runs through this scheme, such as breaking through one of the walls of the old structure to create an internal atrium that reveals the brickwork of the warehouse’s former façade. The first three floors span across both buildings and one of the other primary connectors is a central staircase, designed within an existing lightwell, offering a physical and visual link between these floors of the Studios and the Yard.

Level 1 is a bright welcoming reception with intricate blossom shapes cut out in the ceiling and a microscreed floor, while a level above brings you into one of two ‘hub’ spaces (the other being on level 7) with homely informal seating setups, lockers aplenty and flexible meeting rooms. Pinks, greens and pale timber dominate the colour scheme here with a slightly darker, moodier look and feel on level 2 – a floor also featuring a whole wellness suite with fitness studio, quiet room, parents’ room and a multi-purpose treatment room. This floor is also where you’ll find a carefully designed workspace for global children’s charity Theirworld, reflecting Reed Smith’s commitment to supporting social opportunities.

“The design is based on three interconnecting circles or cogs, and it also doubles up as an events space.”

You’d be forgiven for thinking you were in an East London night spot on level 3 with its club-like space and stone bar, with walls of exposed brick and timber frame, raspberry hued seating and masses of planting, where colleagues and clients can mingle.

The same goes for level 4, a social hub called ‘The Mill’ intended for eating and gathering. “The design is based on three interconnecting circles or cogs,” explains tp bennett’s Chiara Dal Pozzo, associate director, adding that “it also doubles up as an events space.” Mark Matthews and his team are also based on this floor, in the heart of the action and he’s keen to stress that before client and employee spaces were quite segregated. “Now there’s a nice overlap,” he says. This space features adaptable furniture elements that can be

easily be moved depending on the type of event. It’s also connected to an adjoining external terrace with furniture in ontrend blush shades. Further refreshment points can be found in the ‘kiosk’ style setups on, for example, level 3.

There is, of course, desk-based work to be done here too for the 640-strong staff headcount and to this end, there are a mix of open, agile and private workspace to suit the employees’ preferences. The open plan areas have been prioritised along the façade side of the floorplates, while the cellular spaces are on the inside, a deliberate move to encourage greater collaboration. And this being the legal profession, confidentiality is paramount with effective soundproofing in meeting rooms where private discussions are being held. Elsewhere, acoustics were

“This is not your average corporate tin can.”

an interesting case in point, “We weren’t allowed to spray the soffits,” explains Dal Pozzo, “so we had to think of alternative solutions.” These range from colourful grids in the ceiling to fan shaped pendants by BuzziSpace to perforated timber solutions. Quiet is the order of the day in library areas too, where black bookcases separate small group areas.

Crisscrossing more into the ‘old’ Studios part of the project, there are remnants of its former use: a fire door and an original winch in a meeting room here, another exposed brick wall there. “It was something of a coordination challenge but these imperfections are what makes the building interesting,” says Davies, describing the scheme in conclusion as “the essences of a new and old building in a way that responds to architectural heritage and offers a modern, rejuvenated workspace. It’s a characterful not corporate office and not faddish.”

Flooring

Mafi

Element 7

Furniture

The Furniture Practice (products from: Gubi, Knoll, NaughtOne, &Tradition, NORR11, Cappellini, Normann Copenhagen, Muuto, Brunner, Kettal)

Other

Autex (acoustic ceiling panels), Shaw Carpets, Havwoods, IdealWork (microscreed), JBH (fabric walls and ceilings), TMJ (joinery), Tai Ping (rugs), ADS (decorators), TopAkustik (acoustic timber ceilings), Quadrant (carpets), Radii (partitions), Soltech (blinds & curtains), SAS International (ceilings)

aleaoffice.com |

Unveiling hybrid office space in London’s first new town for over 50 years, Conran and Partners and Allies and Morrison craft a warehouse space with heart.

“One of the best ways to create a place that feels real is to look at the history of the place and its people.”

Canada Water is an emerging development hub with an enviable postcode. Decades in the making, this area in Southwark’s Old Surrey Docks has been undergoing some form of regeneration or investment since the 2000s, with the current 53-acre masterplan by developers British Land promising to deliver London’s first new town in over 50 years.

With 130 acres of wildlife-rich green space, the dockland neighbourhood (set to include state-of-the-art offices, new homes, retail spaces and leisure centres) is being positioned as something of a rival to the nearby Canary Wharf – its leafier, trendier and somehow more tranquil sister, if only a ten-minute tube ride away. In progress for nine years, the first commercial building has now been completed, with architects Allies and Morrison and interior designers Conran and Partners tapped to create Dock Shed: a warehouse space with heart.

For 200 years, this dockland brought building supplies into the Thames from Europe and North America. Dock Shed therefore receives its name from the buildings that once occupied its footprint: simple sheds that covered stacks of

timber, drying them out ready for construction. “When you're working in a masterplan like this and have to create basically a brand-new neighbourhood, it's so hard to create authenticity,” says Michael Delfs, development executive at British Land. “One of the best ways to create a place that feels real is to look at the history of the place and its people. This history is what we've leaned on for a lot of the masterplan to create something that is both new, but which also feels authentic – like it belongs here.”

Architects Allies and Morrison also looked to archival photos to offer its contemporary take on the docklands, crafting a champagne-hued slat façade inspired by the old timber-clad buildings. “Because this was the first building going up on the masterplan, it was important that it had a mission statement and set a precedent,” explains Director Mark Foster. “We were mindful that it needed to be a precursor for what’s going to come next, setting

Image on previous page: Interdepartmental coworking space at Dock Shed

Left: Conference tables for collaborative working Centre: The floorplate is split into different islands with rugs and seating clusters

the mood for the development and how the architecture should be approached.”

Creating an L-shaped footprint, Foster’s team flanked the building with side streets and introduced plant-filled step-downs instead of a monolithic rear wall, in consideration of local residents. Dock Shed is also British Land’s most sustainable building to date, thanks to its use of XCarb steel, repurposed raised access floor tiles and recycled window frames saving as much as 400 tonnes of embodied carbon.

Inside, Dock Shed opens into an expansive, seven-metre-high warehouse: part lobby, part café and part social hub, it’s a welcoming face for the six-storeys of office space above, each level boasting a 40,000 sq ft floor plate and outdoor terraces with protected sight lines to landmarks like St. Paul’s and the Gherkin. The hybrid concept offers tenants a more informal space for coworking, taking meetings or simply a coffee break, with Conran and Partners tasked with bringing warmth and an elevated feel to an otherwise

industrial scheme. Cultivating a communal atmosphere that also offers enough privacy, layered interventions like soft, doubleheight drapery balance the generous volume and acoustics, while sculptural seating arrangements encourage different modes of work and leisure.

“Another challenge was our recurring theme of the ‘warm warehouse’ – if it felt cold, hard and a bit empty then we had definitely failed,” explains Conran and Partners’ Simon Kincaid. Ambient lighting, cushioned banquettes and verdant planting soften the concrete screed flooring and black steel trusses, introducing tactility with rattan rugs, Faye Toogood’s quilted Puffy Lounge chair and a modular leather sofa by de sede. And what it is it, exactly, that draws us to converted spaces like these? “As well as a feeling of authenticity, a lot of it is down to the flexibility and generosity of space,” answers Delfs. “There are so many things you can do with an old warehouse that you just can't in a typical office floorplate.”

Left: Spaces for dining back onto kitchen facilities

Below: Charcoal walling is offset by vibrant artworks

Right:

Steel beams and trusses have been painted and left exposed

Flooring

Lazenby screed Rols rugs

Furniture

Dodds & Shute for procurement. & Tradition

Mattiazzi

Aperatus

Carlo Scarpa Van Rossum de sede

Toogood

Surfaces

Na – joinery by Horohoe

Lighting 18 Degrees

Artwork

Installation fabrication by Art Story

Planting

Patrick Featherstone

Thanks to these generous proportions, the studio could enlist longtime collaborators Dodds & Schute to procure bespoke, oversized pieces, including a vast timber waiting bench and Van Rossum’s Adjacencies coffee table – both evoking a fallen tree. “High quality means longevity, so if you replace it less often, that’s a massive save in energy and carbon,” explains Kincaid. “This is something [Dodds & Schute] take very seriously – as a B-Corp company, they interrogate a lot of the supply chain to ensure that they're using materials that have been ethically sourced or manufactured, and that the furniture pieces come from companies that have the same morals and positions on sustainability as they do.”

The most notable custom pieces, created by Art Story, hang from the ceiling: three double-height installations weave sisal rope, cotton and carved timber to create permeable divisions that subtly zone each space, without blocking valuable light.

Diagonal woven lines echo the geometry of the colossal steel beams, an architectural feat in themselves bearing the 30-tonne weight of a new leisure centre below. This material honesty and raw, unfinished aesthetic continues with a stainless-steel communal table, crafted with a handfinished patina and exposed rivets. Against black timber cladding and sheer cream curtains, soft furnishings and artwork from British Land’s own collection also provide welcome accents of bottle green, burnt orange and mustard yellow.

With neighbouring mixed-use project

Three Deal Porters almost complete, British Land hope to turn Canada Water not only into a destination to work, but a place to stay. The developers use King’s Cross as an example, somewhat floundering in its early days before the bars and restaurants of Coal Drops Yard opened – instead, with spaces like Dock Shed, they’re baking in these ‘reasons to stay’ from the very beginning.

Words: Natasha Levy

Photography: Tim Salisbury

For wine merchant Flint, Mowat & Company designed a new-old workplace that nods to terroir.

It was 2006 when Sam Clarke and Jason Haynes founded the wine merchant Flint, with the aim of bringing fine wines from around the world to discerning oenophiles in the UK. Since its beginnings, Flint has championed the notion that the best tasting bottles are those that demonstrate a deep connection with their terroir: the natural environment in which they’re produced. Earlier this year the merchant sought to strengthen

its relationship with its own locale by commissioning architecture studio Mowat & Company to renovate its office in Kennington, South London.