Bridging Networks

Editors: Jennifer Donovan

Stefanie Koperniak

Design & Illustration: Michael Lewy

Writers: Grace Chua

Katie DePasquale

Barbara Donohue

Photography credits:

LIDS Student Conference photos provided by the Student Conference committee. Commencement Reception photos taken by Andrea Censi. Photo of Elie Adam taken by Jennifer Donovan. Photo of Andrea Censi taken by Michael Lewy. Photo of Munther Dahleh taken by Lillie Paquette.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems

77 Massachusetts Avenue, Room 32-D608

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139

http://lids.mit.edu/ send questions or comments to lidsmag@mit.edu

A Message from the Director

On behalf of the entire LIDS community, I would like to welcome you to the Spring ’15 issue of LIDS|All. As you may know, I have taken on the role of LIDS directorship in October 2014, following Alan Willsky, who stepped down as LIDS director in July 2014 and Munther Dahleh, who served as the interim director until he took on the directorship of the “New Entity”, recently entitled Institute for Data, Systems, and Society (IDSS). I would like to take this opportunity to thank Alan and Munzer, as well as John Tsitsiklis who was one of the associate directors, for their extraordinary leadership, which strengthened LIDS’s position as a focal platform for research in the broad area of analytical information and decision sciences, and also expanded its research beyond boundaries, including new emerging areas at the intersection of several fields. They have created a vibrant and supportive environment for all of us in LIDS, students, faculty, and staff included, which we are proud to be part of and call our home. I would also like to thank Pablo Parrilo not only for his excellent contributions as an associate director but also for agreeing to stay on this position.

This year is particularly exciting for us since LIDS has recently agreed to join IDSS, whose

ABOUT LIDS

The Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems (LIDS) at MIT, established in 1940 as the Servomechanisms Laboratory, currently focuses on four main research areas: communication and networks, control and system theory, optimization, and statistical signal processing. These areas range from basic theoretical studies to a wide array of applications in the communication, computer, control, electronics, and aerospace industries.

charter aligns with LIDS-style research of addressing fundamental challenges in a systematic and rigorous manner. IDSS focuses on solving complex, societal problems and has both academic and research components anchored in information and decision sciences, statistics, and human and institutional behavior. LIDS, while continuing to flourish as an international center of excellence in the science of information and decision sciences, is also excited to play a leading role in the development of the new institute and in realizing its vision and impact in both research and academic programs.

In this issue, you will find an article about IDSS, as well as a set of articles about LIDS students, faculty, research and administrative staff, and alumni. Each of these articles showcases the accomplishments of an extraordinary individual shaped in part by their experiences at LIDS. This is yet another piece of evidence that the future of LIDS is bright and I look forward to being part of it.

Sincerely,

Asu Ozdaglar

LIDS is truly an interdisciplinary lab, home to about 100 graduate students and post-doctoral associates from EECS, Aero-Astro, and the School of Management. The intellectual culture at LIDS encourages students, postdocs, and faculty to both develop the conceptual structures of the above system areas and apply these structures to important engineering problems.

BRIDGING NETWORKS

By Grace Chua

One sticky afternoon in mid-August of 2003, as people were just leaving work or school, an overloaded power line sagged into an unpruned tree outside Cleveland, Ohio. The line went down, and its power was rerouted to another line, which then short-circuited, causing a cascade that gradually swept across the northeastern United States. Streets went dark, subway lines stopped working, and some 55 million people from New York to Toronto were left without power for up to two days.

The blackout was a combination of many factors: insufficient monitoring meant operators were not alerted early enough to the blackout, while the region’s interconnected power grids were not conversing properly with each other. What’s more, the networks that control monitoring and communications often need grid power to operate, while power grids need communications networks to monitor and control power supply.

That interdependency between critical infrastructure networks is what LIDS graduate student Marzieh Parandehgheibi, of the Aeronautics and Astronautics department, is trying to understand on a theoretical level.

“I’m trying to look at the interaction between infrastructure like the power grid, the communications network, the water network, and the gas system,” she says. “These are interdependent, meaning that the operation of one system

is dependent on the operation of the others.” For instance, for a pair of interdependent networks, what’s the minimum number of points, or nodes, in one network that must go down to affect the operation of another point in the other? (And the more philosophical question: Is it even possible to tell?)

While some models of interdependent networks exist, Marzieh explains, they are often too simple to reflect real-world interactions. For example, one can develop a simple, centralized algorithm to control a grid, but the real US power grid is divided into regions and often split up between multiple utility firms. And real-world power grids usually have some form of backup capacity to tide them over for a while.

Marzieh, who works with Professor Eytan Modiano, hopes the theoretical insights gleaned from modeling and examining such networks will lead to the development of better control algorithms, as well as network designs that provide greater resilience—even-smarter smart grids, so to speak.

Growing up in Iran, the daughter of two philosophy professors was particularly keen on physics and mathematics, just like her brother Ali, who is three years older.

“We’ve always been close,” she says. “My brother has always been an inspiration to me, and we studied together most of the time. When

we were very young, our parents would always give us books to read, and as a child, I used to read biographies of the great scientists like Einstein and Marie Curie,” she adds.

and the practical reality of how power grids are engineered.

After majoring in electrical engineering at Sharif University of Technology, Marzieh followed in her brother’s footsteps to come to LIDS. (He, too, is a LIDS alumnus.) Here, she became fascinated by a 2010 paper in Nature that first outlined a model for such interdependent networks.

“But the more I read about it, the more I talked to people from the power-grid and communications fields, the more I learned about the gaps in the model,” she says. To come up with more realistic models, she attended conferences and seminars and found herself bridging worlds between the theoretical modeling work of LIDS

As power grids grow more complex, work like Marzieh’s will become even more important— even in ways that may not yet be foreseen. For instance, new technologies in transmission and distribution will have to be incorporated into the grid. Software will help operators with grid monitoring. Electric vehicles will alternately tap into the grid or serve as storage units. And as the grid share of renewable energy sources like wind or solar power grows, power grids might need to have more reserve capacity to smooth out electricity supply when these intermittent sources fluctuate. However, having too much reserve capacity is expensive and inefficient. Marzieh explains, “If we have smarter control over the system, we can decrease the size of these reserves. So we’re looking at appli-

“Our parents would always give us books to read, and as a child, I used to read biographies of the great scientists like Einstein and Marie Curie.”

cations where we can use these better controls, and evaluate the risks we might add to the system. If a failure occurs in the control and communication network, what is the impact on the power grid?”

“Everyone’s trying to see how we can connect these new technologies to the power grid,” she says. “They will help a lot, but may also pose new risks to the system, and it’s very important to identify these risks before failures happen.”

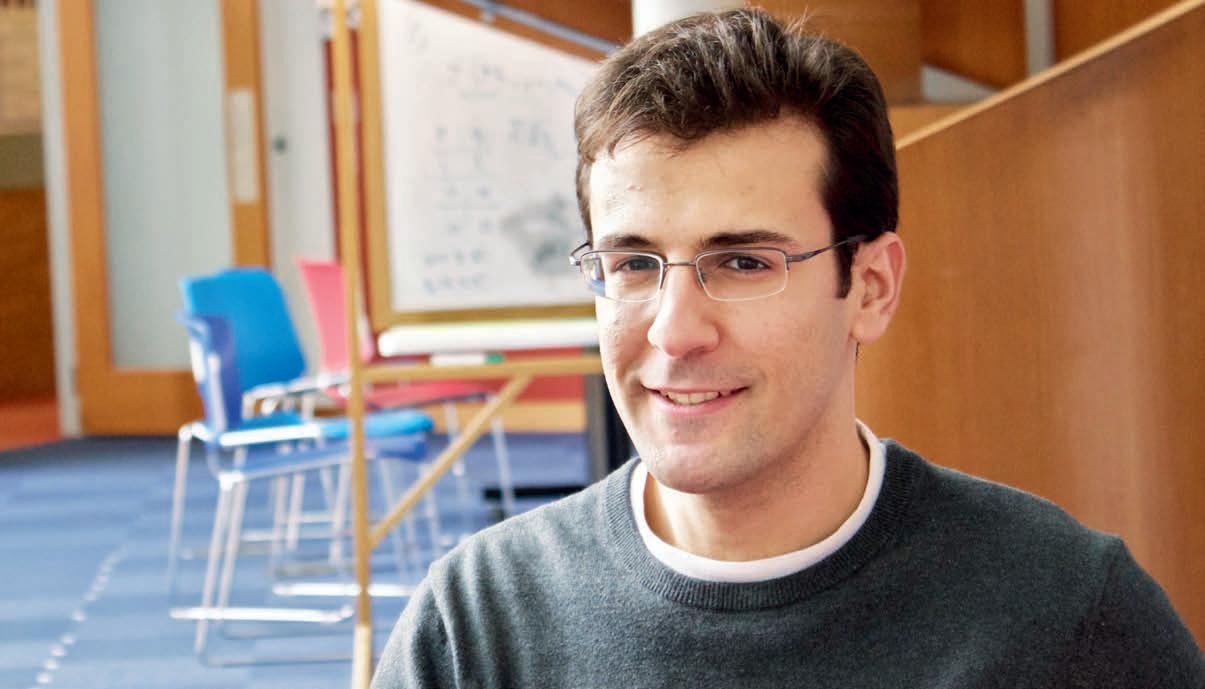

Mathematical underpinnings of the unexpected

By Grace Chua

On any given afternoon, a visitor to LIDS might find a dark-haired, bespectacled graduate student pacing back and forth across the sun-drenched lounge, or staring out of the floorto-ceiling windows.

Elie Adam isn’t just daydreaming—he’s lost in thought, perhaps about how failure propagates throughout interconnected systems, and the logical principles that underlie such cascades. And pacing is one of the ways he thinks best about his research.

Elie is a fifth-year graduate student at LIDS, where he works with Professors Munther Dahleh and Asu Ozdaglar.

Broadly, their team studies how large, interconnected networks such as power grids, financial markets, and transport systems might fail; looks to understand the theoretical underpinnings of how failures cascade through networks; and tries to develop more resilient networks for the future.

More specifically, Elie’s work is on the second aspect—understanding the logic of cascade effects and the unexpected phenomena that emerge. Think of it as basic, fundamental research that underlies and has applications across many fields where complex systems are involved, from power grids to financial systems.

kets—is studied separately on its own, he explains. But they share an important aspect that needs to be understood. “There isn’t a good foundation, a solid foundation, for people to understand how things propagate,” he says. And as technologies in each of these fields become more complex, he thinks it’s more and more essential to understand these systems rigorously.

But what are cascade effects? Elie likes to illustrate this with power grids. If one part of the grid fails, the electricity it carries gets redistributed to put pressure on other lines, which might fail in turn. That’s the basic idea of a cascade.

Take electrical circuits for instance, with a power source and resistors throughout the circuit. If a resistor cannot endure the current passing through it, the resistor breaks; in turn, the current is distributed elsewhere in the circuit and other resistors may break.

It might be relatively easy to figure out the eventual outcome of a failure in one circuit or another. But what happens when multiple circuits are linked up? The outcome might be greater than simply combining the outcomes of each circuit. Instead, there can be unexpected consequences and failures, produced by the very interactions between the circuits.

Each of these fields—grids, transport, and mar-

“The question we would be interested in is: what configurations will our circuits go through? Will our circuits break down?” Elie says. “You have

these systems, you combine them, and you get a gap between what you expect to happen without taking the interactions into account, and what actually happens.” The goal is to “mend that gap,” to extract some information or features from such interconnected systems to be able to say what will happen when systems interact.

And while it’s possible with today’s computing power to just simulate a simple system, Elie hopes to describe what happens mathematically. “In simple systems, simulating is fine. In larger systems, that’s not quite possible without guiding insight.”

Ultimately, the goal of such theoretical work is to give insights into how connections between systems and structures affect an outcome— what might cause a larger system to fail or be resilient, where its weak spots are, and so on. Applied to real-world situations, that would help policymakers figure out where best to invest resources or shore up weak spots. For example, there have been tremendous advances in renewable energy technology, but less work has been done on integrating such technologies into a larger power grid and balancing between efficiency and resilience.

Growing up in Lebanon, Elie had a natural flair for mathematics and science. At the American University of Beirut, he studied computer and communications engineering, and was influenced in particular by three professors there

who are LIDS graduates: Ibrahim Abou-Faycal, Fadi Karameh, and Louay Bazzi.

“I admired their rigor, skill, and knowledge— and that’s why I wanted to come here,” he says. In the long term, he hopes to stay in academia.

To relax and get away from work, Elie draws and paints; he’ll sketch mostly for fun, but has also used his sketches for posters and presentation slides. He also dabbles in stone carving and practices karate with an MIT club.

He sees parallels between his hobbies and work. “For instance, if you think too hard about what you’re drawing, you’re going to make an awful drawing,” he says. “So what you do is you forget everything and just do it. Now, to be able to develop the intuition to draw like that, you have to train.” Likewise with karate, which involves repeated practice until the movements are intuitive. His research, which requires only pen and paper—and sometimes not even that—is a creative process that takes repeated cycles of practice and thought.

And he views problems not as things to be defeated, but to be gently pried apart and solved. “Don’t consider the problem to be an enemy that you want to crack, consider it to be more of a friend that you want to understand,” says Elie. “You’re just talking to that friend, and what you want to do is get to know that friend by asking questions, and then they give you back

an answer. Sometimes that person doesn’t want to talk, then you come back later and carry on the conversation.”

It’s a conversation carried out in his head, while patiently pacing the long blue carpets of the LIDS lounge. “I carry what I do with me all the time,” he says. “It doesn’t mean that I’m thinking about it all the time, but that I play with it, do something else, and come back to think about it.”

That creative freedom is one of Elie’s favorite aspects of his work. “I’m lucky I’m doing this sort of thing,” he says.

Finding Safety in Systems

By Katie DePasquale

Mark Luettgen is in a unique position: he has a job that is both intellectually fulfilling and important to the well-being of the country. A LIDS alumnus who got his PhD in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at MIT in 1993 after getting both his bachelor’s and his master’s there, Mark has always loved studying

mand and control systems.” With such a breadth of areas in which STR works, the practical impact that Mark and STR can have is significant. “We’re addressing important problems that, if they can be solved, will result in technologies that influence people’s lives in a very positive way. They’re also technically interest-

“STR is developing a visual pill identification system that will enable the recognition of unknown prescription pills from an image taken from a cell phone.”

signals and systems. It’s what brought him from Wisconsin to Massachusetts for one of the best engineering programs in the nation. Now he puts that love to good use as President and CEO of Systems & Technology Research (STR), the company that he cofounded with LIDS alumnus Joel Douglas (’94) and other colleagues. With technology groups that do research and development applicable to defense, intelligence, and homeland security, STR is primarily focused on work done in the interest of national security.

When taking an overall look at what Mark and his colleagues do, he says, “Much of the work relies on signal processing, estimation, optimization, information theory, and control technologies that are developed at places like LIDS. We apply those technologies to a wide range of applications, including radar, communications, video, social media, navigation, and com-

ing challenges. What we’re building at STR is an intellectually stimulating environment where smart people work collaboratively on hard problems.”

The way that Mark came to cofound STR has a lot to do with his time at LIDS. A student of Professor Alan Willsky’s, Mark’s first job when he graduated was at ALPHATECH; Alan was its cofounder along with other LIDS colleagues including Michael Athans, Nils Sandell, and David Kleinman. (MIT alumnus Sol Gully was also an ALPHATECH cofounder.) Mark stayed there for 15 years, working in areas such as operations research, signal processing, object tracking, and resource management. When he left and went to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), he worked in similar areas, but this time directly for the government.

It was after his time with DARPA that Mark chose to cofound STR. With years of experience honing his expertise in intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance data collection, processing, and exploitation systems, Mark has taken on the challenge of continuing his work while running a company, and he believes LIDS has played a role in his success. “The ideas developed at LIDS are important to the problems we work on. We build on and apply related ideas and methods to the national security sector in which we work.”

As further proof of LIDS’s impact, Mark’s connection to it continues this day. Alan consults for STR on projects, and other STR staff members come from LIDS and from other departments at MIT.

As far as other, non-defense projects, STR does have some in the works. One is a medically related system that automatically classifies pills from camera imagery. Mark says, “Correct identification of prescription pills is a daily challenge for millions of patients and health care professionals. Most senior citizens take prescription medications and, unfortunately, many pills, capsules, and caplets look similar— and a single misidentification can lead to medical complications. Because of this, the National Library of Medicine has compiled a database of prescription drug images and pill descriptions to aid health care professionals in identification of an unknown pill; however,

there is a need for an automated tool to help the millions of senior citizens prone to accidental misidentification in the home. To address this need, STR is developing a visual pill identification system that will enable the recognition of unknown prescription pills from an image taken from a cell phone.”

When he’s not working, Mark unwinds by running, reading, and spending time with his four children. His oldest daughter is looking at colleges and considering studying astrophysics, so they’ve spent time together at the HarvardSmithsonian Center for Astrophysics, attending talks and pondering the mysteries of the universe. After this time spent on the stars, Mark returns from the intricacies of space to the intricacies of the sensor and information processing technologies that affect our daily lives.

MIT’s New Institute for Data, Systems, and Society

By Barbara Donohue

On July 1, 2015, MIT’s new Institute for Data, Systems, and Society (IDSS) was officially launched. Created with much thought and deliberation, IDSS provides a unique focus within MIT on understanding complex systems—one that combines both technical and social sciences, drawing from every school at MIT and a multitude of disciplines. LIDS will play a central and vital role in this new institute, in everything from its leadership and shape to its education and research activities.

The mission of IDSS is to provide an education and research environment that advances analytical methods for prediction, design, and control of complex systems encompassing both technical and social systems. Within this mission, IDSS will investigate societal challenges in areas such as finance, energy, health, and transportation, utilizing analytical methods and tools from statistics, data sciences, and information and decision systems.

“In order to understand things like power outages and bank failures, you still need electrical engineers and economists—but today you also need anthropologists and data scientists,” says Munther Dahleh (Director of IDSS and William A. Coolidge Professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science) in the MIT News article “Deans announce new Institute for Data, Systems, and Society.” “Our ability to collect and aggregate data is already well beyond our ability to un-

derstand what it could tell us—and no single discipline, on its own, holds the keys to understanding and mitigating such risks.”

“We used to have just mechanical and physical systems to deal with,” says Alan Willsky, Edwin S. Webster Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and former director of LIDS. Now, understanding of every type of system is broadening to include human and institutional behavior. “Even power systems include markets,” he says.

If you look at complex engineering systems, whether transportation systems, communications networks, or power grids, the physical part that is engineered is clearly important, but so is its interaction with people and institutions, Munther says. For example, humans are an important factor in problems with any transportation system. People’s driving habits create traffic congestion, but cities and states can influence travel behavior with tolls, incentives, and other factors. “To design efficient systems, you have to address all three components,” Munther says: engineering, human behavior, and institutional behavior (or the actions of governing and regulatory agencies).

The process of developing this new institute within the Institute began in January 2014, with the formation of committees made up of about 40 faculty members. These committees worked intensively for months to develop the mission,

scope, and structure of the proposed new entity, and the academic programs it would offer. In April 2014, the combined committees issued a report outlining the entity that would become IDSS.

As excited as people are about this new entity within MIT, it’s important for LIDS staff, students, and alumni/ae to know that LIDS is an integral part of IDSS, Munther says. LIDS is “part of the core and leadership of this new institute and will continue to retain its name as a research laboratory,” he says. LIDS will continue to have its own space on campus, and the current director of LIDS, Asuman Ozdaglar, is an associate director of IDSS.

Alan saw the development of the new institute close up. He served as co-chair of the committee on IDSS’s organizational structure. As a former director of LIDS, he was pleased with the new arrangement. IDSS addresses “major challenges deep in the areas where we have great strengths,” he says. “LIDS is a wonderful environment. People love it. We worked very hard to keep that.”

Part of the charge of IDSS is building a coherent effort in statistics at MIT, Munther says. The report on the formation of IDSS lists 49 courses in ten different departments that include statistics. “At MIT statistics is everywhere, so you can’t find it,” says Alan. “Now it will have a focal point.”

IDSS faculty will include those currently working in LIDS, the former Engineering Systems Division (ESD), and the Sociotechnical Systems Research Center (SSRC)—all entities that have traditionally investigated information and decision systems, statistics, and human and institutional behavior. Each faculty member of IDSS will hold an appointment in an academic department, as well. This will help IDSS maintain its interdisciplinary nature, Munther says.

Over time, the plan is to hire 15 to 18 new faculty, Munther says. “We are given slots to hire and do so in cooperation with the departments.” Faculty will be associated with all five schools of MIT: Architecture and Planning; Engineering; Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences; Science; and Sloan School of Management. The search is on to identify new IDSS faculty, Munther says, and offers have already been made to two statisticians to start in the fall.

The academic programs offered by IDSS will include a range of cross-disciplinary studies, including an undergraduate minor and a PhD in statistics and a PhD in Social and Engineering Systems.

The committee report outlined in some detail the different academic programs to be offered. For example, the new PhD in Social and Engi-

neering Systems will be based on the mathematical, behavioral, and empirical sciences, emphasizing data-driven analysis and modeling. It will require engineering expertise and engage quantitative social science, including field research. The program will draw students focused on specific problems, as well as students who are interested in particular methodologies.

Technological advances in areas like smart sensors, big data, communications networks, computing systems, and social networking have resulted in an increasing number of large-scale, interconnected systems that generate vast amounts of digital information. Using this information well—extracting actionable insights and developing rigorous modeling systems— presents substantial challenges across many disciplines. Alan recalls talking with another committee member, a professor of political science, when IDSS was in the planning stage. This committee member said that even political scientists have big data problems, too.

IDSS will be boundaryless, Alan says. The plan was “to be inclusive, not exclusive. It’s good to engage with people in different disciplines. That’s half the fun.” And it’s often at these intersections where real innovation happens.

Photo: Lillie Paquette

The Creative Side of Robotics

By Katie DePasquale

When entering Andrea Censi’s office at LIDS, the first thing you see is evidence of his experimental work: more than a few computers, a couple of mobile robots, a quadcopter on a shelf, and a robotic manipulator in the corner. Then you spy the slightly more unusual white beach ball, which Andrea refers to as a “spherical whiteboard” and uses to teach differential geometry. By the time you notice the presence of a few dozen yellow rubber ducks, a fancy microphone, and a redheaded wig, it’s clear that not only are you in the presence of a creative thinker, but it’s also going to be quite a story finding out how all of this is related to Andrea’s research.

Coming to LIDS in 2013 after getting his PhD in Control and Dynamical Systems (CDS) from Caltech (their equivalent of LIDS), Andrea is a research scientist who knows and respects the history and seriousness of control engineering. But as his office décor suggests, he wants to keep things lively and welcoming. He doesn’t believe that “serious” must imply “austere,” which is why you’ll find jokes in his papers and why he’s always happy to organize the occasional friendly prank on his fellow scientists.

Andrea grew up in Rome, Italy, in a household headed by two scientists. His mother is a nuclear physicist and his father a control engineer. Although getting a PhD in Control and Dynamical Systems could be seen as inevitable, Andrea arrived there through a circuitous route

that started with artificial intelligence and evolved into a more specific focus on the control aspects of robotics. These days, Andrea advocates a modern take on control that involves working with realistic complex systems, dealing with high-dimensional data and large-scale computation, and creating “cloud-enabled” robots. While the technical tools he employs are unusual for the field, Andrea sees his work as continuing the tradition of cybernetics in the original spirit of Norbert Wiener, the MIT professor who founded the field in the 1940s.

One area of robotics that Andrea is passionate about, and about which he wrote his dissertation, is the problem of learning for robots that’s known as “bootstrapping.” Can an agent embodied in an unknown body learn from sensorimotor data all the models needed for its operation? Andrea thinks so, citing the brain as an example of a system that can learn to use any sensor or actuator.

Upon arriving at LIDS, he started collaborating with Emilio Frazzoli, a professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics, on the use of eventbased neuromorphic vision sensors. The output of these sensors is not periodic frames, but rather a series of asynchronous events that mimic the neuron’s spikes-based communication. Together they believe that this new technology is the key enabler for creating very agile, autonomous flying vehicles; and in a way, this conclusion brings Andrea full circle to an

early inspiration for his work at Caltech, where he analyzed the behavior of the fruit fly, the most agile autonomous “vehicle” known to man.

As he continues his research, Andrea is cultivating his artistic side, as well, with his most recently acquired hobby: video editing. An early bit of performance art, posted on his website, shows a time-lapse video of him typing and drinking espressos, racing against the clock to finally submit his paper ten minutes before a conference deadline as Beck sings in the background. However, as with those unusual objects in his office, there is a more purposeful side to his video editing. It is becoming a professional service. Andrea proposed and led the creation of a video “trailer” for the 2015 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), held in May 2015 in Seattle, Washington. The trailer shows conference highlights, but it’s not just an excuse to create more “easily consumable media,” as Andrea puts it. Rather, the goal is to lead the public conversation about robots, their place in our lives, and possibilities for the future. He says, “If I ask you about a robot video, probably you’ve seen Google’s autonomous cars, but that is a video likely made by a PR department. This trailer is done by the scientific community, so it is our version of the story.”

Telling his version of the story with his philosophy is important to Andrea. So is inspiring

his colleagues by whatever means he can imagine, which is how we return, first, to those yellow rubber ducks. For next year’s ICRA conference, he’s arranging for a thousand of them in identical sizes to be delivered to the facilities for his roboticist colleagues to take home. Later, they can each submit clips for his new trailer, provided their clips all contain one of the official ducks. Of course, the ducks have nothing whatsoever to do with robots, but Andrea is betting that establishing an arbitrary duck constraint will make the submissions more creative. The several dozen rubber ducks currently in his office are there so he can evaluate the different models available. The fancy microphone is also related to the trailer, which was translated into eight languages. On very short notice, Andrea had to find and record versions of the text in Arabic, Korean, Spanish, and Italian. Fortunately, with the help of LIDS’s international community, he was able to gather a narrator for each language.

As for that final object, the redheaded wig, that is evidence of Andrea’s passion for pranks. When MIT Mechanical Engineering Professor and Irishman John Leonard was scheduled to give the LIDS Seminar on St. Patrick’s Day, Andrea arranged to have him served a pint of Guinness instead of the customary bottle of water. The improvised “Irish waitress” for the event, John’s post-doc Liam Paull, exceeded expectations by wearing that wig.

Goofy props and costumes notwithstanding, these activities demonstrate Andrea’s belief in the importance of people getting together, getting along, and having fun while they learn. As he says, “In the end, it’s not about making jokes, it’s about having an environment where creativity flourishes. Having a relaxed atmosphere helps students to be more creative, and also to have the feeling that everybody’s more accessible if they need help.”

Andrea likes to post to the LIDS mailing lists with thoughts about the discipline and bits of poetry about nonlinear systems. He has organized events such as the Faculty Applicants Support Group last winter, where students and post-docs shared their apprehension about the faculty application process, and is assisting in organizing the LIDS Tea with Asu Ozdaglar, Director of LIDS, which is meant to facilitate a more relaxed interaction among faculty, students, and postdocs. In the summer, he plans to take LIDS students on a series of “school trips” to robotics companies in and around Boston. He wants everyone who enters his office to take to heart the sign outside his door, which reads, “You are welcome here.” It doesn’t matter whether it’s to talk about neuromorphic sensors or to share a laugh.

by Barbara Donohue

LIDS alumnus Kostas Bimpikis likes to know how networks work, especially networks that include human agents.

A self-described “operations guy,” Kostas says, “Studying networks is natural for the field of operations. There has been a long tradition of studying physical networks like telecommunications. Networks that involve humans are more complicated. The questions are very different. People aren’t passive agents like computer switches. They are active and you have to take their incentives into account.”

“Most of my research revolves around the study of social networks, and specifically how social peers affect what we know, what we have access to, and what decisions we make,” says Kostas.

Kostas investigates the role of a social network’s structure on how information is obtained and shared among peers. Dense networks tend to be better at aggregating dispersed information than less connected, more clustered networks, he says. Right now he does this work at the Graduate School of Business at Stanford University, where he has been an assistant professor of operations, information, and technology since 2011.

However, Kostas’s love of learning began at an early age. Kostas grew up in Xanthi, a small city in northern Greece near the Turkish border. His father worked for the Greek public

telecommunications company and his mother taught in high school. His parents had both studied physics in college and instilled in Kostas a strong desire for a good education. This, he says, is one of the main reasons he ended up at MIT.

In 2003, Kostas received his undergraduate degree in electrical engineering from the National Technical University of Athens, Greece. He received an MS in computer science from the University of California, San Diego in 2005 and then enrolled at MIT, receiving his PhD in operations research in 2010.

When he first came to the US to study computer science at UC, San Diego, Kostas had no idea what operations research (OR) was. However, the father of a close friend had a PhD in OR and introduced him to the field. This led him to explore it more thoroughly at MIT.

“I was very, very lucky to find Asu Ozdaglar [a professor in Electrical Engineering & Computer Science, current director of LIDS, and associate director of IDSS],” says Kostas. “We started to work closely together, and my other advisor, Daron Acemoglu [Professor of Economics], joined in the work.”

During his time at MIT, Kostas was part of both LIDS and the ORC (Operations Research Center). This is when he began studying social networks. The motivation for this line of study

while at MIT came from the increasing availability and importance of social media. “When I started work on my PhD, social media were coming into prominence,” Kostas says. Facebook had its initial public offering; Twitter was gaining momentum.

A central question that occupied his research was: What is the impact of social media on the welfare of participants, given that these technologies make information exchange easier and faster? “We wanted to use our understanding of network theory,” Kostas says, “to look at things like how a company can use data on network structure and the interaction among customers to maximize product adoption or revenue.”

Targeted advertising offers another application. For instance, suppose two firms are competing. How do they allocate their budgets to maximize the impact on their customers?

The applications are not limited to business. “You can also use this line of work in exploring ways to maximize the impact of a limited budget for a social cause. “Our main goal is to provide a theoretical framework to support such applications,” Kostas says.

Lately, Kostas has been working on applying similar ideas to supply chain networks. For example, Toyota has a large, multi-tier supply chain that spreads to several geographical loca-

tions and is subject a variety of disruptive events. How do these disruptions propagate? How can the company work with its supply chain to mitigate these risks?

Another facet of Kostas’ work is examining dynamic learning in the context of research and development (R&D). “Imagine you and I are working separately toward a goal that no one knows for sure is achievable, such as building a driverless car,” Kostas says. “If we can see each other working, each can see the other succeeding or failing. Every time you see me failing, that makes you pessimistic about your own prospects. You say, ‘This guy is smart, he’s skillful, but he’s failing. Maybe that means the problem we’re trying to solve is not solvable.’ This effect might bias us away from putting effort toward achieving the goal.”

The research shows that this effect is dominant, Kostas says, “so it might be optimal for us not to observe each other.”

The ultimate goal is to think of R&D in a dynamic framework and explore how to optimally design regulations that could aid the process of innovation.

Since Kostas has such interdisciplinary interests, he has appreciated the opportunities available from LIDS and ORC. “I benefited a lot from being in a place like LIDS. Nobody can know everything, but collectively, people at LIDS

know a lot. There is a high concentration of intellectual capital. That was great about LIDS and ORC. I had desks in both, so I benefited from both and from MIT as a whole.”

“If I had to summarize what I liked about LIDS, ORC, and MIT, it would be the academic freedom. You can pursue pretty much whatever you want and do not have to stay within a single academic department.” This was certainly true in his case.

“Working with an engineer and an economist,” Kostas says. “There are not very many places you can do that.”

Sound Bites: Alina Man

How long have you been at LIDS, and what do you do here?

I’ve been at LIDS for a little over half a year (since 2014). I’m mainly an administrative assistant to Professor Munther Dahleh. I arrange his travel, manage his calendar, and deal with expense reports and the various committees in which he participates. I also handle travel and expense reimbursements for his research students.

Previously, I was a high-stakes testing coordinator in Toronto. I was in charge of all things exam delivery such as finding testing locations across Canada, creating exam forms, preparing proctor guides, proctor training, and quality assurance for the exams—for different organizations like the Financial Planning Standards Council or the National Dental Hygienist Board. I also proctored in test centers. I lived in Canada for three years before moving to Boston last year.

And before that, I worked as a front desk agent in Romania, where I’m from originally.

Outside of LIDS, what do you do for fun?

Wow, it sounds like you’ve lived and traveled all over the world.

My first time living in the US was in 2007. I took a year off from university to be in an au pair program in Virginia. The family I lived with was amazing. They made me feel very comfortable and helped me adjust to all sorts of things—the time difference, the language, the food...everything was different. That’s when I fell in love with North America and knew that I wanted to live here eventually. I was their first au pair so it was an adjustment for them, too! I’m still in touch with them today.

I studied tourism geography at university, and I love to travel. My mom jokes that I have a gypsy heart and have to move around; I can’t stay in one place.

How

do you like working at LIDS?

It’s different from what I used to do, but I enjoy it. I think it’s the people—it’s a good environment and they make me feel at home. I’ve never worked in higher education before, so there were a lot of things for me to learn. For instance, MIT has specific rules around travel and reimbursements. And different accounts have different rules.

I’ve traveled within Europe, in Canada, and now we’re traveling around the US. Last year we went to the Bahamas on a belated honeymoon, and this weekend, we’re visiting friends in Wisconsin and driving down to Chicago. Someday I’d love to go to India to visit the Taj Mahal; I’d also like to visit Finland and Norway, and maybe take a cruise to Alaska.

I’m also an avid reader of fantasy and science fiction—there’s just something about letting your imagination run wild.

What are your future plans or dreams?

My dream would be to travel for the rest of my life! But for now, I’m focused on getting to know the city and the surrounding area, getting to know MIT and all that it has to offer. That’s my main goal for now. Eventually, I’d like to go back to school and study project management, but that will be in the next two to three years.

LIDS Awards & Honors Awards

Congratulations to our members for the following achievements!

Prof. Sanjoy Mitter received the 2015 IEEE Eric E. Sumner Award.

Prof. Dimitri Bertsekas was the 2014 winner of the Khachiyan Prize of the INFORMS Optimization Society.

Prof. Bertsekas was also the 2015 winner of the George B. Dantzig Prize of SIAM and the Mathematical Programming Society.

Kuang Xu was named one of the recipients of the 2014 Dimitris N. Chorafas Foundation Award.

LIDS alum Kush Varshney was the winner of the KDD “Best Social Good Paper.” Varshney also received the 2014 IBM Faculty Award and was a finalist for the 2014 Bell Labs Prize.

LIDS student Marzieh Parandehgheibi was named a Graduate Woman of Excellence by the Office of the Dean for Graduate Education.

Prof. John Tsitsiklis received the EECS Louis D. Smullin Award for Teaching Excellence.

Graduate student Kimon Drakopoulos received the Sloan Outstanding TA award for 2014-2015.

LIDS alums, Profs. Kostas Bimpikis and Ozan Candogan, along with graduate student Kimon Drakopoulos were one of the winning teams in the LinkedIn Economic Graph Challenge.

Prof. Devavrat Shah received “Distinguished Young Alumni Award, IIT Bombay” in March 2015.

MEng student Kang Zhang received the David Adler Memorial EE MEng Thesis Award for outstanding Master of Engineering in electrical engineering.

LIDS alum Jinwoo Shin won the 2015 ACM SIGMETRICS Rising Star Research Award.

Honors

Prof. Asu Ozdaglar was named the Director of LIDS. Prof. Ozdaglar was also named an Associate Director of the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society.

Prof. Munther Dahleh was named the inaugural Director of the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society (IDSS).

Prof. Eytan Modiano was selected to serve on the IEEE Fellows Committee.

LIDS alum Kush Varshney was selected to participate in a Frontiers of Engineering Symposium by the National Academy of Engineering.

LIDS Seminars 2013-2014

Weekly seminars are a highlight of the LIDS experience. Each talk, which features a visiting or internal invited speaker, provides the LIDS community an unparalleled opportunity to meet with and learn from scholars at the forefront of their fields.

The Stochastic Systems Group seminar schedule can be found at: http://ssg.mit.edu/cal/cal.shtml

Listed in order of appearance.

Eric Kolaczyk

Boston University

Department of Mathematics and Statistics

Eli Gafni

UCLA

Department of Computer Science

Jon How

LIDS, MIT

Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Aerospace Controls Laboratory

Dario Floreano

EPFL

Laboratory of Intelligent Systems

Demosthenis Teneketzis

University of Michigan Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

Leandros Tassiulas

Yale University

Department of Electrical Engineering

Yuan Zhong

Columbia University

Department of Industrial Engineering

Stefano Soatto

UCLA

Department of Computer Science

Ilya Dumer

University of California, Riverside

Department of Electrical Engineering

Yihong Wu

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Ilan Lobel

NYU

Department of Information, Operations and Management

Sciences

Ian Dobson

Iowa State University

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

Alberto Abadie

Harvard University

John F. Kennedy School of Government

Kostya Turitsyn

MIT

Department of Mechanical Engineering

John Leonard

MIT

Department of Chemical Engineering

Randall Berry

Northwestern University

Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

Dirk Bergemann

Yale University

Department of Economics

Panagiotis Tsiotras

Georgia Tech

Department of Dynamics and Control Systems Laboratory

Rakesh Vohra

University of Pennsylvania

Department of Economics & Department of Electrical and Systems Engineering

Emmanuel Abbe

Princeton University

Department of Electrical Engineering

Andrew Lo

MIT

Sloan School of Management

Yiling Chen

Harvard University

Department of Engineering and Applied Science

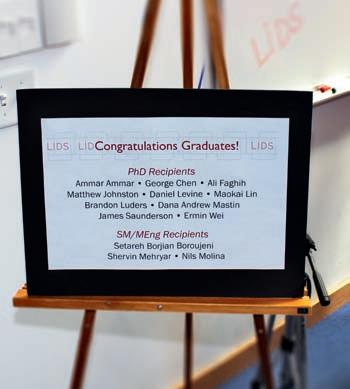

2015 LIDS Student Conference

ORGANIZING COMMITTEE SPEAKERS PANELISTS

Student Conference Chairs

Christina Lee

Shreya Saxena

Omer Tanovic

Committee Members

Giancarlo Baldan

Hamza Fawzi

Swati Gupta

Narmada Herath

Ali Kazerani

Nikita Korolko

Marzieh Parandehgheibi

James Saunderson

Dogyoon Song

Jennifer Tang

Jianan Zhang

Elie Adam

Diego Cifuentes

Ellen Czaika

Swati Gupta

Abigail Horn

Qingqing Huang

Dawsen Hwang

Alexandre Jacquillat

Prof. Ramesh Johari

Nikita Korolko

Christina Lee

Quan Li

Yongwhan Lim

Beipeng Mu

Marzieh Parandehgheibi

Maite Pena-Alcaraz

Frank Permenter

Jordan Romvary

Hajir Roozbehani

Vivek Sakhrani

Prof. Sridevi Sarma

Shreya Saxena

Jennifer Tang

Omer Tanovic

Dr. Jennifer Tour Chayes

Prof. Martin Wainwright

Andrew Young

Stephen Zoepf

Prof. Dimitri P. Bertsekas

Dr. John R. Dowdle

Prof. Robert G. Gallager

Prof. Sanjoy K. Mitter

Prof. John N. Tsitsiklis

Moderated by Prof. Munther Dahleh