Ann Arbor, Michigan Wednesday, November 5,

Michigan residents lose SNAP benefits Nov. 1 amid government shutdown

Federal judges ordered the Trump administration to use emergency reserve funds for SNAP payments

Update 11/2: On Oct. 30., the State of Michigan announced it will provide $4.5 million to the Food Bank Council of Michigan to assist residents impacted by the government shutdown.

On Oct. 31., two federal judges ruled President Donald Trump’s administration must use contingency funds to continue the dispersal of SNAP benefits.

According to Michigan Attorney

General Dana Nessel, even if the Trump administration releases the contingency funds to states immediately, Michigan residents set to receive SNAP benefits may still see delays. It is not yet clear if the Trump administration intends to appeal this ruling.

Update 11/3: On Nov. 3, the Trump administration announced in response to the federal judges that it will send out partial SNAP payments this month. The emergency fund it will use has $4.65 billion — enough to cover half of recipients’ usual benefits. It is still unclear when recipients will receive their aid.

The United States Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service announced Oct. 27 that no Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits will be distributed from Nov. 1 until further notice due to insufficient funds. Nearly 13% of Michigan households receive assistance from SNAP, a federal program that provides monthly food benefits to low-income households. USDA’s website states that due to the ongoing federal government shutdown, there may be limited availability of government funding to pay for these benefits.

About 41.7 million Americans, including 1.4 million Michiganders, receive SNAP benefits, typically through an electronic debit card

which can be used at grocery stores nationwide. In a press release, Elizabeth Hertel, Michigan Department of Health and Human Services director, said losing SNAP funding will have drastic impacts on many families, and that the state will do what it can to minimize harm.

“SNAP is more than a food assistance program; it’s a lifeline for many Michigan families,” Hertel said. “It helps families put nutritious food on the table, supports local farmers and grocers, and strengthens our communities and economy. We are strongly disappointed by the USDA’s decision to delay this assistance, and in Michigan we will do what we can to help blunt this impact.”

Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel announced in a press release Tuesday that she has joined a coalition of 22 other attorneys general and three governors in filing a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts against the USDA and Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins for the suspension. The press release claims

the suspension violates the Administrative Procedure Act, which governs the process by which federal agencies develop and issue regulations.

“While states are responsible for administering SNAP in their state, the federal government is obligated to fund and set the monthly amount of SNAP benefits,” the press release read.

“Suspending SNAP benefits in this manner is both contrary to law and arbitrary and capricious under the Administrative Procedure Act.

Where Congress has clearly spoken to provide that SNAP benefits should continue even during a government shutdown, USDA does not have the authority to say otherwise.”

On Oct. 24, the USDA released a memo stating that it won’t use its emergency funding to distribute partial SNAP payments for next month if the government shutdown continues after Oct. 31. The USDA explains that the contingency fund is not available to support regular benefits for fiscal year 2026, as it is not considered an unforeseen event, which the contingency fund

is meant for.

“Due to Congressional Democrats’ refusal to pass a clean continuing resolution (CR), approximately 42 million individuals will not receive their SNAP benefits come November 1,” the memo reads. “Instead, the contingency fund is a source of funds for contingencies, such as the Disaster SNAP program, which provides food purchasing benefits for individuals in disaster areas, including natural disasters like hurricanes, tornadoes, and floods, that can come on quickly and without notice.”

Nessel wrote in her press release that she believes the government shutdown should be considered an emergency to avoid a pause in benefits.

“Emergency funding exists for exactly this kind of crisis,” Nessel said. “If the reality of 42 million Americans going hungry, including 1.4 million Michiganders, isn’t an emergency, I don’t know what is. It is cruel, inhumane, and illegal to hold back emergency reserves while families struggle to put food on the table.”

UMich Law professor files U.S. Supreme Court petition

Laura Beny requested the Supreme Court hear her discrimination case against the University

CHRISTINA ZHANG Daily News Editor

Laura Beny, University of Michigan Law School professor, filed a petition on Monday asking the Supreme Court to hear her racial and gender discrimination case against the University. Beny alleges University officials — including Mark West, former dean of the Law School — subjected her to improper and discriminatory disciplinary action.

Beny’s original lawsuit was filed in 2022 and dismissed by the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan in 2024. Beny appealed the dismissal, but the Sixth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s decision this July.

Beny was hired in 2003 and became the second African American female tenure-track professor in the Law School’s history. In 2018, she received a disciplinary notice for disruptive conduct and in 2019 received another notice for verbal abuse.

The Sixth Circuit opinion states West issued Beny her third notice of disciplinary action on March 31, 2022, the sanctions from which are the subject of her lawsuit.

“The University provided a legitimate reason for the disciplinary actions set out in the third notice: ‘[Beny’s] ‘abandonment’ of the classroom, retaliation against students who raised concerns about her course, and her troubling communications with other faculty and staff members’,” the opinion reads.

However, according to the District Court opinion, Beny was approved for medical leave on April 15, 2022, under the Family and Medical Leave Act for the period between Feb. 15, the date Beny informed her class that she could no longer teach, and May 15, 2022.

Beny argues in her lawsuit the University disciplined her when they should have known she did not truly abandon her class due to her approved medical leave, which she alleges would make the decision to discipline her pretext for a discriminatory motive.

The Sixth Circuit opinion asserts the University and West are protected under the honest belief rule — which holds that as long as an employer had an honest belief in their provided reason for disciplinary action, an employee cannot establish pretext, even if the reason is later proven false.

“There is no evidence in the record to suggest that West and others doubted that Beny ‘abandoned’ her class when she was issued the disciplinary notice,” the opinion reads.

“That is, nothing in the record suggests that any relevant decisionmakers knew about Beny’s leave application or that it was FMLA related.”

Beny is represented by a team of four attorneys led by Amos Jones, principal and founder of Amos Jones Law Firm. In an interview with The Michigan Daily, Jones alleged decisionmakers at the Law School were aware of Beny’s medical leave claim.

CONTINUED AT MICHIGANDAILY.COM

Ann Arbor community protests United Electrical Contractors amid racial discrimination lawsuit

About 30 protesters gathered Thursday morning outside of the Five Corners construction site on Packard Street to call for housing developer Core Spaces to terminate their contract with United Electrical Contractors. Protesters carried signs that read “United Electric Liable for Racism” and called for “Justice for the United Six,” the initial group of six former UEC employees who filed a federal lawsuit against UEC for racist behavior by company management and employees.

UEC is assisting in the construction of Five Corners, a new student housing development, and admitted legal liability in a federal racial discrimination case in June. They were held liable for racial discrimination against nine employees who said they were harassed and called racial slurs while working. As part of the settlement, UEC will pay each former employee, on average, $47,960 plus attorney fees. Richard Mack, an employee and union rights attorney at Miller Cohen, organized and led the rally. In an interview with The Michigan Daily, Mack said the protest aimed to bring attention to the working conditions faced by UEC employees.

“It was shameful, some of the things,” Mack said. “A Black man who had the N-word written on his hard hat and was forced to wear that hat for a week because they wouldn’t give him a new one and Hispanic Latino employees faced all of the most vile slurs you can think of from workers. And not only would the employees complain about all of these things, which happened weekly

for many of them, but when they complained to supervision, supervisors laughed.”

Mack led the group in a march around the Five Corners project area, guiding them in a series of call-and-response chants to voice their frustration with the situation. The crowd stopped in various locations around the site to listen to different speakers,

including U.S. Rep. Debbie Dingell, D-Mich. Dingell said the citizens of Ann Arbor cannot back down from fighting for racial justice.

“Every person on this Earth was created equal and every person should have the right to compete for a job based on their ability no matter their sex or the color of their skin,” Dingell said.

“We cannot let them wear us down. Our future is at stake and we the workers are the backbone of America.”

City Councilmember Cynthia Harrison, D-Ward 1, who also spoke out at the protest, said she believes racist and sexist comments to employees are unacceptable and should not be tolerated in Ann Arbor.

“We are here today to fight against racism,” Harrison said.

“We are here today to fight against sexism. This is my hometown. I was born and raised here, and I will not tolerate it. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

Mack told The Daily he believes the Ann Arbor community, who he believes do not agree with racist and sexist behavior in the workplace, should ask Ann Arbor authorities not to allow Core Spaces to work with UEC.

“You need to go to your city council, you need to go to your city leaders, you need to go to the University itself, who was going to be sending students to live in that edifice that is built by a racist, sexist contractor,” Mack said.

“We cannot allow it to happen, so we need to let everyone in Ann Arbor know to come out and stand up against this. Because if we don’t stop it, it’s going to grow.” Andre’ Watson, president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People of Ann Arbor, who also spoke at the protest, said the fight is not over until there is justice for those who have been discriminated against in the workforce.

“We appreciate all the support out today, and just understand that this is just the beginning,” Watson said. “We will fight this to the end.”

Ann Arbor’s aging rentals leave students fighting mold

“For some reason, there’s always water leaking from the showerhead, out of the shower — basically, where the mushroom is living.”

SALMA ABDELALE Daily Staff Reporter

When LSA senior Daisy Galgon spotted a small beige lump sprouting from her bathroom wall, she assumed it was a bug.

“Then I looked closer and thought, ‘there’s actually no way’ — it was a mushroom,” Galgon said. Her housemates named it Stanley. But the mushroom soon became a reminder of a recurring problem many student renters face — mold.

In an interview with The Michigan Daily, Galgon, along with two of her roommates, Art and Design senior Emery Swirbalus and LSA senior Zach Levine, said that while they love the experience of sharing a house, they’ve encountered several maintenance issues since moving in.

“When we got here, there was a ton of mold everywhere,” Swirbalus said. “There was literally mold in our dishwasher.”

In their bathroom, Galgon said, persistent moisture has led to an unusual sight — mold that grew its own mushroom.

“The wall behind is covered in mold and peeling and breaking, so it’s not a terrible surprise where (the mushroom) comes from,” Galgon said.

Levine said he worries the issue likely goes beyond surface-level mold and stems from the issue of water damaged walls.

“For some reason, there’s always water leaking from the showerhead, out of the shower — basically, where the mushroom is living,” Levine said. “There must be water in the wall that’s causing the mold.”

In an email to The Daily, Jennifer Head, an assistant professor and researcher at the School of Public Health, wrote that mold exposure can have significant health impacts.

“It can trigger asthma episodes and exacerbate respiratory symptoms, including coughing, sneezing, and eye irritation,” Head said.

“Spores are microscopic, so an individual may not know if they are inhaling spores. Mold growing behind drywall or in corners of homes may not be readily visible to residents.”

For some students, those health risks have been experienced firsthand. In an interview with The Daily, LSA sophomore Alex Ponzio said he first encountered mold in his University residence hall and again later in an off-campus rental. He noted that while the issue in his Bursley Residence Hall room was handled promptly by University Housing, his experience in off-campus housing in Ann

Arbor was more complicated.

“We walked in and you could just feel the air was thick,” Ponzio said. “It smelled really musty. There was stuff leaking down the walls, like the tiles were covered in it. I actually noticed that I’m allergic to mold, so I was pretty nasal for the first few weeks.”

Tian Xia, a research investigator in the University’s Department of Environmental Health Sciences, said mold often grows under conditions similar to those found in older student housing.

“Mold grows in damp, warm and dark environments with poor ventilation,” Xia said. “It can grow in hidden spaces like behind furniture or under the carpet, and spores can become airborne from these areas and pose health risks.”

Property managers, meanwhile, emphasize that prevention and fast response are critical. In an email to The Daily, Katie Vohwinkle, vice president of property management at Oxford Companies, a prominent Ann Arbor leasing company, wrote that they prioritize timely inspection and verification whenever tenants report potential mold issues.

“When a tenant reports a potential mold concern, we treat it with the same urgency as any maintenance issue,” Vohwinkle wrote, “A qualified maintenance technician is

dispatched to inspect and document the reported area.”

Vohwinkle emphasized that Oxford’s lease agreements outline clear expectations for tenants regarding mold prevention.

“Our lease agreement includes comprehensive mold prevention requirements, outlining tenant responsibilities such as removing visible moisture accumulation, using exhaust fans, and maintaining reasonable climate and moisture levels,” Vohwinkle wrote. “Tenants are contractually required to report water leaks, persistent mold growth, or HVAC malfunctions immediately in writing.”

While Oxford outlined a detailed remediation process, students said experiences with other leasing companies in Ann Arbor can vary widely. Ponzio said he feels that, in some cases, property companies rely on high demand to avoid more expensive repairs or replacements.

“A lot of property companies in Ann Arbor try to cut as many corners as they can because they know they can charge whatever to students,” Ponzio said. “If the property company’s not going to respond to you and take care of the issue, you’re kind of stuck. You either pay $1,900 for a newer place or deal with the conditions you have.”

New Ann Arbor Economic Development Director Joe

Giant talks affordability, development goals

“To be able to live in a city that I had for a long time really admired and grown to love was a dream come true.”

GRACE SCHUUR Daily Staff Reporter

The Michigan Daily sat down with Joe Giant, Ann Arbor’s new director of economic development to discuss housing affordability, the city’s development priorities and economic relationship with the University of Michigan. Giant began the position March 17 after previously working as the community development administrator for the Redevelopment Department of Fort Wayne, Ind. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The Michigan Daily: What drew you to Ann Arbor?

Joe Giant: When you’re studying city planning, you’re learning about all these cities that are doing it right with progressive, best practices, and Ann Arbor is always on those lists: number one quality of life, best place to raise family, most educated. So we just drove up. It was the middle of March, the longest, most disappointing month. But there were so many people out: people running, walking, eating outside, drinking coffee outside, just being active, being so vibrant. And it just had this energy that I had just never experienced anywhere that I had been, especially in making the most of an otherwise disappointing season. So it just felt serendipitous. I felt like I had to apply for it. I’m really excited and happy about the stuff that I get to do on a dayto-day basis, but to be able to live in a city that I had for a long time really admired and grown to love was a dream come true.

TMD: What does the role of Ann Arbor’s economic development director entail, and what does a typical week look like for you?

JG: Over the last few years, we’ve experienced some city challenges: It’s an expensive place to live. We are kind of struggling to provide some basic city services, like maintaining our parks and getting our roads paved and everything.

So city staff created this office and charged me with trying to facilitate housing development,

helping to build our tax base and place-making. So, making sure that the development that we have helps to continue forward our wonderful, exciting, vibrant quality of life.

A lot of it is being the first point of contact for a lot of developers that are coming to town, the first point of contact for businesses that are thinking about opening up here. When projects start to become a little bit more real, it might be negotiating with them to figure out if the city is going to be involved in the project, whether it’s infrastructure or it’s tax increment financing, trying to put together deals, working with other city agencies — like utilities and like transportation — to make sure that our infrastructure is keeping up with the growth that we want to see.

TMD: What are your top priorities for Ann Arbor’s economic development?

JG: It’s not “Joe Giant’s plan for Ann Arbor,” it’s the residents’ and community’s plan for their community. The city is commendable in a lot of ways, but one of them is definitely that the people that live here really, really care about it, and they care actively about it. Right now the city is undergoing an amendment to our Comprehensive Plan, where we’re looking at areas that we want to grow. And so what I would do is look at the policies that are in that plan and say, “How do we take those just from a sentence that’s pretty open-ended to actual activity on the ground?” It’s making that connection between what our policies and goals are to how that affects the built environment, how that affects the economy.

If you look at our Comprehensive Plan draft, it is very focused on making sure that there is housing for people that want to be here. Right now, there are wonderful communities here. There’s places to live, but it’s challenging when the people that make a city a city can’t afford to live there; teachers and police officers, firefighters and nurses have to commute in. So, that shows up in the plan a lot.

That’s something that definitely is important to people that work at Larcom City Hall, making sure

that we have housing options for not just for professors, doctors and lawyers, but also the people that on a day-to-day basis make this a wonderful place to live.

TMD: Are there any early wins or projects from your first six months you’d like to highlight?

JG: We have a couple of cityowned properties. One of them is called the Kline’s Lot. It’s right behind Main Street on Ashley Street, a real high-profile site. I’d say it’s probably one of the best development sites in Michigan, if not the Midwest. And then another site around the corner across from our YMCA. We talked to City Council, tried to get their priorities, tried to figure out what our policy said about how those lots can be developed and we selected developers for those sites. And we’re negotiating with those now, which doesn’t sound like a huge win, but knowing that we have at least some preliminary buy-in from a couple world-class developers for these sites, I’m gonna take the W … The vision that these two companies put forward for these respective sites is really exciting and ambitious, and I am thrilled to see where it goes.

TMD: What development projects are you currently prioritizing?

JG: In our Comprehensive Plan draft that I mentioned, we identified some areas of the city where we think we could thicken it up, grow a little bit, add some higher density housing. One of those is South State Street just north of I-94, there’s this tall building, 17 acres of surface parking, an old parking structure, and there’s a gas station. We have proposals to redevelop 17 acres into 1,000 units of housing, including 200 affordable units, 100,000 square feet of commercial units, streets, blocks, open space — essentially just about six blocks of a downtown feel. I think it’s something like a $600 million development. It would be one of the largest projects in Ann Arbor’s history, probably the largest publicprivate partnership where the city is taking an active role in the development of it. It’s called Arbor South. It’s on the agenda for the Nov. 6 City Council

Stanford Lipsey Student Publications Building 420 Maynard St. Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1327 734-418-4115 www.michigandaily.com

ZHANE YAMIN and MARY COREY Co-Editors in Chief eic@michigandaily.com

ELLA THOMPSON Business Manager business@michigandaily.com

NEWS TIPS tipline@michigandaily.com

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR tothedaily@michigandaily.com

EDITORIAL PAGE opinion@michigandaily.com

PHOTOGRAPHY SECTION photo@michigandaily.com NEWSROOM news@michigandaily.com CORRECTIONS corrections@michigandaily.com

ARTS SECTION arts@michigandaily.com

SPORTS SECTION sports@michigandaily.com

ADVERTISING wmg-contact@umich.edu

Editorial Staff

CECILIA LEDEZMA Joshua Mitnick ’92, ’95 Managing Editor cledezma@umich.edu

FIONA LACROIX Digital Managing Editor flacroix@umich.edu

meeting, and we’re really excited to present it to the community.

TMD: What emerging trends in Ann Arbor’s economy present the biggest opportunities — or concerns — for the city?

JG: Our downtown is a regional destination. It’s an amazing place. Since the COVID19 pandemic, I think that we’ve heard that a lot of businesses have seen a change in what their day-to-day experience is like: not as many people around during the day, more people around nights and weekends. So if we’re going to have a smaller daytime workforce population, we’re going to have second, third floors of businesses that are not really great spots for offices anymore. What are we going to do with those? We’re thinking about how to maybe repurpose those for housing or some other uses that might work great in downtown but are a little bit different than we previously contemplated. Another part of that is trying to increase our downtown-resident population. One way to support Main Street businesses is to have more people there, just on a dayto-day basis.

TMD: How do you approach economic development in a city that’s both a traditional municipality and a college town? Do you collaborate directly with the University on projects?

JG: It’s an interesting push and pull: Ann Arbor would not be the wonderful place that it is without the University, and I would argue that the University would not be the wonderful place that it is without Ann Arbor. I think one of the coolest things about this community is the way that the University just bleeds into the city. We have regular meetings with University leadership where we’re learning about what they’re doing, we’re telling them about what we’re doing. We collaborate on big infrastructure projects. For instance, the University of Michigan is building these beautiful residence halls north of the Big House, and when you add that many units there’s an impact on the infrastructure, and they’re helping us fund huge sewer expansion.

CONTINUED AT MICHIGANDAILY.COM

JONATHAN WUCHTER and ZACH EDWARDS Managing Sports Editors sports@michigandaily.com

Senior Sports Editors: Annabelle Ye, Alina Levine, Niyatee Jain, Jordan Klein, Graham Barker, Sam Gibson

CAMILLE NAGY and OLIVIA TARLING Managing Arts Editors arts@michigandaily.com

Senior Arts Editors: Nickolas Holcomb, Ben Luu, Sarah Patterson, Campbell Johns, Cora Rolfes, Morgan Sieradski

LEYLA DUMKE and ABIGAIL SCHAD Managing Design Editors design@michigandaily.com

Senior Layout Editors: Junho Lee, Maisie Derlega, Annabelle Ye Senior Illustrators: Lara Ringey, Caroline Xi, Matthew Prock, Selena Zou

GEORGIA MCKAY and HOLLY BURKHART Managing Photo Editors photo@michigandaily.com

Senior Photo Editors: Emily Alberts, Alyssa Mulligan, Grace Lahti, Josh Sinha, Meleck Eldahshoury

Graciela

Cestero, Irena Tutunari, Aya Fayad

ALENA MIKLOSOVIC and BRENDAN DOWNEY Managing Copy Editors copydesk@michigandaily.com

Senior Copy Editors: Josue Mata, Tomilade Akinyelu, Tim Kulawiak, Jane Kim, Ellie Crespo, Lily Cutler, Cristina Frangulian, Elizabeth Harrington

DARRIN ZHOU and EMILY CHEN Managing Online Editors webteam@michigandaily.com

Data Editors: Daniel Johnson, Priya Shah Engineering Manager: Tianxin “Jessica” Li, Julia Mei Product Managers: Sanvika Inturi, Ruhee Jain Senior Software Engineer: Kristen Su

AHTZIRI PASILLAS-RIQUELME and MAXIMILIAN THOMPSON Managing Video Editors video@michigandaily.com

Senior Video Editors: Kimberly Dennis, Andrew Herman, Michael Park

Senior MiC Editors: Isabelle Fernandes, Aya Sharabi, Maya Kogulan, Nghi Nguyen

AVA CHATLOSH and MEGAN GYDESEN Managing Podcast Editors podeditors@michigandaily.com

Senior Podcast Editor: Quinn Murphy, Matt Popp, Sasha Kalvert

MILES ANDERSON and DANIEL BERNSTEIN Managing Audience Engagement Editors socialmedia@michigandaily.com

Senior Audience Engagement Editors: Dayoung Kim, Lauren Kupelian, Kaelyn Sourya, Daniel Lee, Quinn Murphy, Madison Hammond, Sophia Barczak, Lucy Miller, Isbely Par SARA WONG and AYA SHARABI Michigan in Color Managing Editors michiganincolor@michigandaily.com

SAYSHA MAHADEVAN and EMMA SULAIMAN Culture, Training, and Inclusion Co-Chairs accessandinclusion@michigandaily.com

ANNA MCLEAN and DANIEL JOHNSON Managing Focal Point Editors lehrbaum@umich.edu, reval@umich.edu Senior Focal Point Editors: Elizabeth Foley and Sasha Kalvert

TALIA BLACK and HAILEY MCCONNAUGHY Managing Games Editors crosswords@umich.edu Senior Games Editors: James Knake, Alisha Gandhi, Milan Thurman, Alex Warren

Business Staff

OLIVIA VALERY Marketing Manager

DRU HANEY Sales Manager

GABRIEL PAREDES Creative Director JOHN ROGAN Strategy Manager

UMich Dance Marathon hosts ‘Spook-A-Thon’ on the Diag

Raises awareness for C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital through Halloween-themed event

About 400 University of Michigan students and community members filled the Diag Sunday afternoon for “Spook-A-Thon,” a Halloweenthemed event hosted by Dance Marathon. The student-run non-profit organization raises awareness and fundraises for pediatric therapies and programs at the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital and outpatient clinics through volunteering, hosting events and fundraising.

In an interview with The Michigan Daily, LSA senior Amrita Bhattacharjya, DMUM communications director, said community events like “Spook-AThon” are designed to help U-M students foster relationships with families and patients at the children’s hospital.

“Because our organization is so big, and since we’re students, the members of our work can’t necessarily get to know the families that well,” Bhattacharjya said. “This gives us a chance for all of our members to make friends with the kids (and) the families.”

Bhattacharjya told The Daily DMUM values keeping events such as this one free and instead uses social media for marketing and fundraising.

“All of our family events are completely free because we want to make it as accessible as possible to not just the families, but the greater Ann Arbor community, as well as all of the students,” Bhattacharjya said. “So, this event does not involve any fundraising, but we post a lot on our social media to raise awareness about what we’re doing.”

Kinesiology junior Alex Kersten, DMUM public relations

chair, told The Daily she enjoys the festivity of seeing everyone dressed in costumes.

“My favorite part of the event is definitely seeing all the families come out and seeing all the kids dressed up in their costumes, as well as all the members of Dance Marathon dressed in the costumes,” Kersten said. “Because it really livens the mood for the families and the kids, and it’s a fun experience for them, just to play, (to) do more Halloween-themed things.”

There were numerous U-M student organizations tabled with booths offering activities as part of the event, including Alpha Epsilon Delta, a preprofessional health care society.

In an interview with The Daily, Public Health junior Natalie Hood, DMUM chair at AED, said the event served as a good way for AED’s members to directly

Students Supporting Israel and Let’s Do Something host march in solidarity with

Jewish students

The gathering came after an unidentified person attempted to kick down the door of the Jewish Resource Center

About 100 University of Michigan students and community members marched from the Diag to the Jewish Resource Center Wednesday evening in support of the Jewish community on campus.

Organized by the University’s chapter of Students Supporting Israel and advocacy group

Let’s Do Something, the march was organized after a person attempted to kick down the door of the center Sunday morning.

In an interview with The Michigan Daily, Rabbi Yitz Pierce, program director at JRC, described the attack on the center.

“Early Sunday morning, someone came by our building,” Pierce said. “It’s all on camera. They tried to kick in the front door. And when they failed, they left running and were screaming, ‘F the Jews. F Israel. The Jews control us. F the Jews,’ over and over again. And it was pretty disturbing, to be honest.”

During the event, speakers spoke about their experiences with antisemitism, but also the support they received from the Jewish community at the University following Hamas’s Oct. 7, 2023 attack on Israel which killed more than 1,200 people and resulted in about 250 more being taken hostage. The resulting Israeli military campaign in Gaza has killed more than 67,000 people.

Moshe Shear, chief marketing officer of Let’s Do Something, described how the attack on Israel impacted the Jewish community on campus.

“When I look out here on the lawn and see within 36 hours, so many proud Jews, I really see the essence of the Jewish people and

why we’ve been around since the dawn of time and why our people are never going to go away,” Shear said. “Even with so much hate, things that happened, like October 7…and how we reacted to that moment, or an antisemitic hate crime on the Jewish Resource Center two years later in Michigan, how Jews react to that and take so much hate and turn it into a place of love and a place of building, and build something positive out of it. And it’s so, so beautiful to see.”

LSA senior Dan Viderman, president of SSI and a speaker at the event, thanked attendees for being present at the march.

“SSI was approached with this idea 36 hours ago, and I want to thank each and every one of you guys sincerely for coming out of here,” Viderman said. “These clubs are only as strong as the people that make them up. And we have so much hatred, so much darkness.”

Pierce told The Daily the march was meant to come out of love and support despite the attack against the center.

“The march is happening as a show of love and unity,” Pierce said. “Because when there’s sort of an attack — even a verbal attack — on this community, the way we try to protest and go against it is by coming together as a unit and just showing that we’re strong and proud and not afraid to be Jews.” Pierce said while the march was to show support for the University’s Jewish community, everyone was welcome to participate.

“I think when people see that there’s strength in any community, they feel more included,” Pierce said. “Anyone can join in and walk with us. We try to be very open, not intimidating, and it’s peaceful. Everyone looks at this group

interact with the families they fundraise for with DMUM.

“It’s a nice kickstart because it shows all the members in AED who they’re supporting by fundraising throughout the year,” Hood said. “We get to interact with the community directly, helping through all the fundraising activities.”

Business graduate student Joe Longo, an infielder on the Michigan baseball team, was invited to the event to play games with the children who attended. In an interview with The Daily, he said it was great to see them enjoying the event.

“I’m a member of the Student Athlete Advisory Committee — a couple of our members said it would be a great opportunity for us to get out here and spread some Halloween cheer,” Longo said. “Seeing the kids, seeing their smiles — it’s been amazing so far. They’re going through so

much, and it’s just great to see them out here for fun.”

Kimberly Bannoy, a parent of a child who attended the event, told The Daily in an interview that she enjoyed the enthusiastic atmosphere of the event and was happy to see her son having a good time.

“Halloween is over, but we do love to support anything (U-M),” Bannoy said.

“Obviously, (my son’s) having a blast. The enthusiasm from everybody, involvement with the kids, … we’re having so much fun.”

Ashley Simon, another parent of a child who attended the event, has attended previous “Spook-A-Thon” events with her daughter. In an interview with The Daily, Simon said she especially values how the younger kids can form friendships with the college students.

“Fostering that relationship between the two helps a lot,” Simon said. “What they’re doing has helped so much, like (my daughter) was nonverbal a few years ago, and the small group activities have helped get her verbal and foster some friendships.”

The event, however, is not only supposed to help children. Bhattacharjya told The Daily participating in the event can be fulfilling for all attendees.

“I hope that whoever comes to this event realizes that no matter how much time or how big or small your contribution is…you are making a difference in these kids’ lives,” Bhattacharjya said.

“And if everyone just puts a little bit of effort in, we can really create something beautiful and make a difference in the families’ lives every single day. And, hopefully, make the world a better place.”

William Clements Library presents a ‘Haunted Histories’ murder mystery experience

The library transformed into a 19th century haunted mansion with actors in historically accurate costumes

JOSEPHINE VELO Daily News Contributor

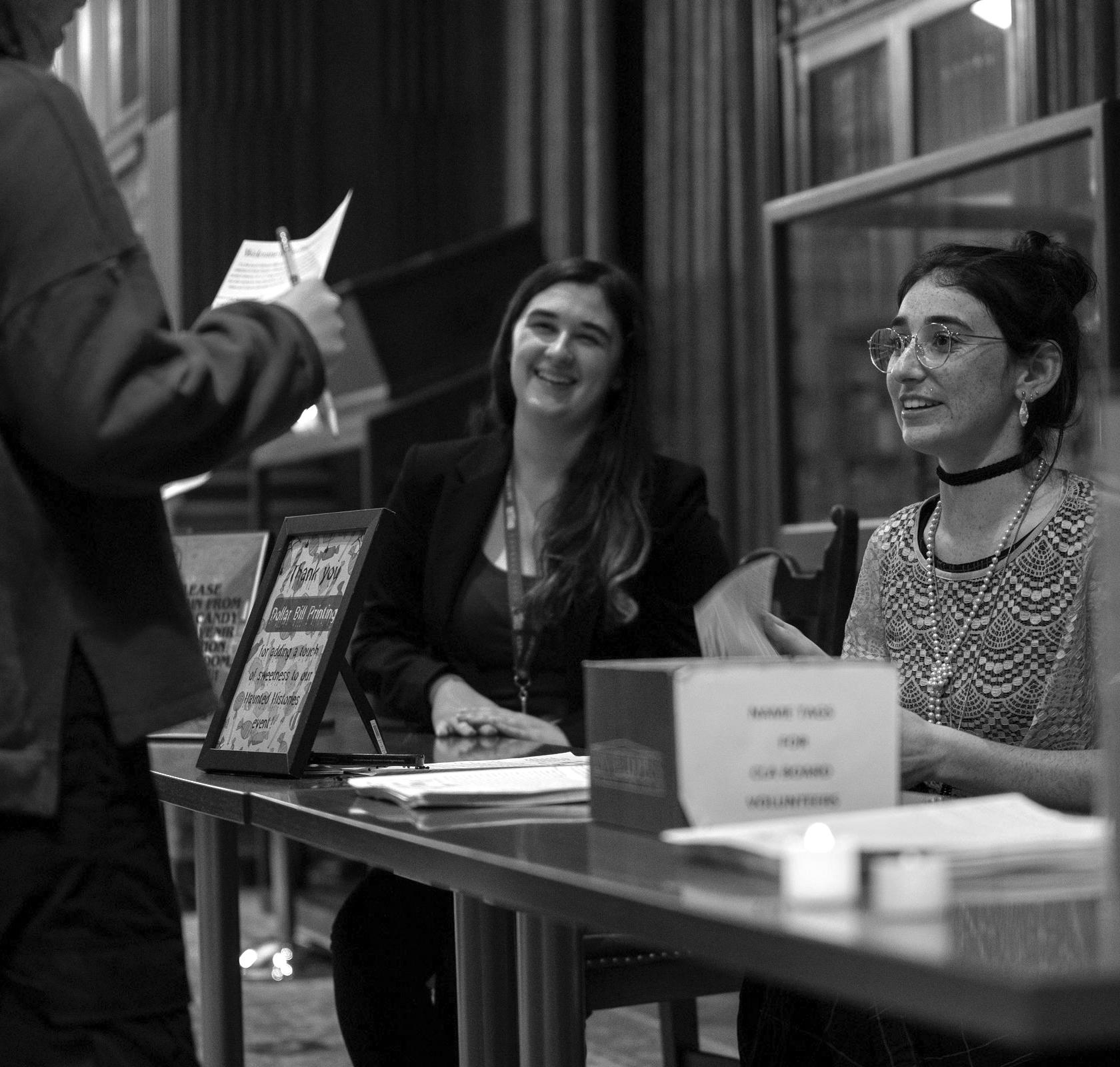

About 130 students and community members gathered Wednesday evening at the William Clements Library for “Haunted Histories,” an interactive 1800s-themed murder mystery event enacted by staff and volunteers. There were historically accurate Halloween costumes accompanied by activities inspired by the time period, such as the card game old maid, paper-doll making and fortunetelling.

The event also centered around a chilling performance by Music, Theatre & Dance senior Sarah Hartmus, who recited part of Edgar Allan Poe’s short story “The Black Cat” for each hour of the event.

In an interview with The Daily, Hartmus said she originally got involved with the William Clements Library through a class and did a voiceover for one of their previous exhibits.

“I love history,” Hartmus said.

something kind of in the theme of the 1883 Vanderbilt Ball.” Oonk told The Daily the William Clements Library is open to students from all academic disciplines, especially since their history is steeped in interdisciplinary curiosity.

and they see people are having a peaceful display of unity.”

In an interview with The Daily, Business senior Izzie Haymann, vice president of strategic planning for SSI, attended the event and said she joined the march to stand against the antisemitic act that occurred next door at the Sigma Delta Tau sorority house where she lives.

“I actually lived at the (Sigma Delta Tau) house next door, and it can be very scary when you have to be worried about events like this,” Haymann said. “So I wanted to march today to show that students at the (University) shouldn’t have to be worried about antisemitism and violent acts occurring due to being Jewish.”

Viderman told The Daily the march served as a reminder of the need to support the Jewish community — which only makes up 0.2% of the world population — in the face of rising antisemitic incidents.

“It’s important now, at a time like this, when Jews make up only 0.2% of the world’s population, to come together to show unity,” Viderman said. “So it’s important for us all to come here.”

Viderman also said all communities can find strength in coming together against hate.

“The Jewish community is not the only community that has to deal with hate crimes, but I do hope that other communities can take inspiration from how we deal with hate crimes,” Viderman said. “The response to hatred is not to spread more hatred against other minority groups or any groups in general. The response should be us all coming together. Let’s all be doing unity events, supporting the great country that is the United States of America, coming together under these pretenses on our amazing campus and coming together in unity.”

The library transformed its interior into a haunted mansion, with cobwebs and fake spiders lining the Avenir Foundation Room stairwell. Participants were given clues and interacted with actors to slowly decipher the murder of the fictional Dr. A. C. Cruing.

In an interview with The Michigan Daily, Kinesiology sophomore Yahil Ceballos said he enjoyed how dedicated the actors were to their roles.

“My favorite part of the event so far is how engaged the actors are at the moment,” Ceballos said. “I’ve had some impromptu discussions with them where I’ve been able to get some clues I don’t think other people have gotten.”

“Anytime I get the chance to do something that’s a period piece or something like this where it’s helping facilitate teaching about history or anything like that, I’m always very into it.”

LSA junior Samantha Huck, William Clements Library outreach assistant, organized the event alongside Angela Oonk, the library’s director of development. In an interview with The Daily, Huck said the library has hosted three haunted history events, and two have included a murder mystery.

“We had wanted to do something kind of in the theme of Edgar Allan Poe, something traditionally kind of spooky, Halloween-esque,” Huck said.

“That’s how ‘The Black Cat’ specifically came about. The theme was dreamt up by our director Angela Oonk, and she decided that we should do

“Sometimes people are like, ‘Oh, you must only host history classes’,” Oonk said. “Mr. Clements himself, he was a U-M alum, and he had an engineering degree but loved history and collected rare books, and I think that speaks a little bit to the (University of) Michigan tradition of being people who are interested and curious. Our biggest hurdle though is because the building is a little imposing, finding ways to make sure people know that they can come inside.”

The Avenir Foundation Room is currently hosting its “For All Ages” exhibit, which showcases historical American games. In an interview with The Daily, Oonk said the inclusion of historical games can help connect the past to the present.

“I’m always thinking about fun ways to get people into the Clements and show people things about history,” Oonk said.

“Everybody’s grown up playing games, so this particular exhibit that we have lends itself very well to people seeing themselves playing those historical games.”

A number of magnificent auteurs broke out in the scene at the start of the 21st century. Blockbuster king Christopher Nolan has been dizzying and dazzling audiences since his debut, “Memento,” in 2000. Horror-turned-social-commentary powerhouse Bong Joon Ho finally got people paying attention with “Parasite,” but he has been documenting the foibles of capitalism since “Snowpiercer.” And then, there’s the science fiction enthusiast Denis Villeneuve (“Dune”), whose subversive films have elevated the idea of what a modern blockbuster movie could be. The greatest of them all, though, may just be a guy who’s obsessed with symmetry.

Wes Anderson’s style has become one of the most easily recognizable (and parodied) in modern cinema. He uses symmetric, centered shots, vibrant color palettes and that iconic yellow text, to create films that feel like they take place inside a dollhouse or diorama.

With the release of his most recent film, “The Phoenecian Scheme,” over the summer, the Film Beat has decided it’s time to decide once and for all which of Anderson films reign supreme.

However, despite our fair and democratic system of voting, some writers were shocked, even horrified, to see where their favorite Anderson piece ended up, resulting in both supportive blurbs and violent refutations of our ranking.

So, for better or worse, here’s The Michigan Daily’s spectacular, phenomenal and totally-not-subjective Wes Anderson ranking that the world has been waiting for:

The Michigan Daily ranks Wes Anderson films

Honorable Mention: “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Three More” (2024)

How does a legendary director evade all the talk about whether he’s too indulgent, too full of himself or too obsessed with his own style? By making a series of shorts in which the artifice, which once decorated his frames, define the formal language of the films, of course!

In the aptly titled “The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Three More” — a feature-length compilation of four short films directed by Anderson — the

auteur has decided to push his style to near avant-garde experimentation. Gone is dynamic scene blocking or elaborate dialogues that flow into one another; a person standing up straight and reciting directly to the camera drives the narrative. Gone is the slightly robotic affectation of Anderson characters — a cold delivery will do instead.

Indeed, these short films find Anderson once again adapting Roald Dahl stories, but with a disregard for conventional film wisdom. The short films feature characters narrating each line of dialogue with book-like, third-person attributions (“he said,” “she said,” etc.). Cheap-looking, set-like foreground and background elements highlight the artifice of film form — which Anderson seems intent on exploring.

Be it boredom, curiosity or a jab at all the critics, the resulting compilation is wonderfully endearing. Anderson, in acknowledging and playing into the awkwardness of his stilted writing and scene construction as of late, ends up ironically making a digestible film that feels unforced and unencumbered. However, “Asteroid City,” for all its thematic import about emotional distance, is still emotionally distant — a conundrum which this series manages to side-step by not having any emotional depth at all. Relying heavily on visuals and Dahl’s original texts, “Henry Sugar and Three More” is a surprising highlight in Anderson’s late career.

— Ben Luu, Senior Arts Editor

“The French Dispatch” (2021) I hate to say it, but “The French Dispatch” represents the worst of Anderson’s style. In the film, the cracks in his iconic style become deep and unavoidable. His work appears as a cumbersome parody of itself, harming the overarching story rather than supporting it. His style has lost a sense of genuineness, instead feeling campy and akin to the recent social media trend of people “Wes Anderson-ifying” their lives. It’s overly complicated, full of rapid cuts and contains intensely obnoxious symmetry, building an elaborate, whimsical aesthetic that distracts from the actual story. It’s a beautiful and vibrantly colored mess.

The film is further burdened by an unnecessarily large ensemble cast that collapses under its own weight. Anderson weaves so many threads together that they get tangled. It seems that he tried to write a story to ensure he’d be able to fit all of his collaborators (and some newcomers) into one film. The narrative suffers as a result of this overly complex structure. Characters are underdeveloped and emotionally removed, storylines are half-baked and the pacing never seems to even out.

It’s no coincidence that this was one of the Film Beat’s few

ror, “The French Dispatch” is the perfect reflection of all of Anderson’s flaws as a filmmaker.

— Isabelle Peraut , Film Beat Editor

“Asteroid City” (2023)

Late-style Anderson (that is, everything since “The French Dispatch”) has its fair share of detractors. Anderson’s success and army of cinephile fans has transformed his style into a recognizable trademark and source of endless parody. Rather than departing from his style, the filmmaker leaned into it even further, stretching his visual language to its formal and emotional limits. No film of his epitomizes this phenomenon more than “Asteroid City.” The film is a play within a documentary within a movie; its actors are actors playing characters turned actors once again. Critics have decried the film with a menagerie of insults: it’s a self-parody, cold, distant or simply insists upon itself.

However, I write this blurb as an impassioned defense of “Asteroid City,” as my well-intentioned yet misguided Film Beat brethren exile it to this undeserved subaltern position. Yes, it is true that “Asteroid City” reflects the most stylized mise-en-scène of any of his films. The artificial set of the diegetic play makes the film’s

son’s style overshadows any semblance of emotional core — is missing the point. The emotional distance between audience and character is more of an intentional feature than a bug; by centering the story around artists making a work of art they don’t understand, “Asteroid City” is Anderson questioning his own commitment to craft. This self-analysis of artistry and meaning makes it one of Anderson’s most personal. What does the play mean? What’s up with that alien? Does any of this matter? Anderson doesn’t pretend to know the answer to any of these questions, but he keeps on asking. “Asteroid City” may have its haters, but I find it to be one of Anderson’s most self-aware and emotionally resonant films to date.

— Will Cooper, Daily Arts Writer

“The Phoenician Scheme” (2025)

There are plenty of reasons why “The Phoenician Scheme” ranked this low. For starters, it’s Anderson’s most recent release, so it’s possible that many of my fellow Film Beat writers have not gotten around to seeing it. It’s also possible that people don’t rock with late-stage Anderson and his overt stylization. Or maybe people are tired of his aesthetic. Whatever the reason may be, I simply do not care — “The Phoenician Scheme” is great, and deserves to be in the upper echelon of his films. Despite being in the later part of his career, “The Phoenician Scheme” is very much a return to form for Anderson. He departs from ensemble works to revisit a formula that has worked for him time and time again: narratives centered around family. As with many of his films, especially his recent work, Anderson has been criticized for prioritizing “style over substance,” but this simply isn’t the case here. Sure, his aesthetics have been dialed up a notch, but the emotional core — the father-daughter relationship — is what defines the film. Beneath the schemes, assassination attempts and espionage, the film is really about a father’s struggle to balance his work life and personal life. It seems to serve as a reflection for Anderson on managing the roles of both a working director and a parent, resulting in one of the most beautiful narratives in his filmography. As I noted in my review of the film, “The Phoenician Scheme” is Anderson at his most personal, and

ABIGAIL WEINBERG Daily Arts Writer

Football. In a small, rural high school smack dab in the middle of Ohio, football may have very well been the first word I heard when I entered high school. What stood out to me about this sport was not its fast-paced action, and definitely not its entertainment value, but its incredible ability to take over the lives of everyone around me — from obsessive players to crazed, small-town fans. Moving to college, this obsession seems to have followed me, as every weekend I watch thousands of attendees make their way to Michigan Stadium. I’m haunted by the one sport I can’t understand.

When I saw the latest horror film in theaters was not just

‘Him’ makes football horrifying

a sports horror, but a football horror, I was neither phased nor interested. What did intrigue me, however, was the immensely divisive discourse it was causing online. It seemed that all these reactions came as a result of the big name attached to this film: Jordan Peele.

Ever since 2017’s immensely successful “Get Out,” Peele has brought the psychological horror film genre to a new level of dark and twisted. In past projects like “Get Out” and “Us,” his work has gone beyond the classic psychological trope of madness, delving into societal issues such as systemic racism and class ideologies. These works drew praise from fans and critics, and led to Peele becoming the first Black person to win the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay for “Get

Out.” However, Peele’s success streak seemed to end with his last film “Nope,” which was seen by critics as too ambitious, with little connection between plot points — from horse ranch activities to UFO sightings. So, when Peele’s name appeared in the title card next to the psychological football horror “Him,” not as a director but as a producer, it was unclear what this new project would look like. But given my disinterest in football, as well as Peele’s lack of creative direction on the film, my expectations were low. That was, until “Him” proved me wrong.

Cameron “Cam” Cade (Tyriq Withers, “I Know What You Did Last Summer”) is a quarterback tackling a quick rise to fame and the opportunity to join the professional football league, the USFF. But there’s a catch:

To earn his spot in this league and on his dream team, The Saviors, he must make it through a week of training with his predecessor, quarterback Isaiah White (Marlon Wayans, “Scary Movie”). As the week begins, the plot becomes more absurd and Cam’s problems worsen. At Isaiah’s house, Cam is locked in a sauna, injected with unknown medicine and haunted by a rolling football (of course).

Isaiah’s wife, Elsie (Julia Fox, “Uncut Gems”), seems like a beacon of normality at first, but soon proves to be just as corrupt as the rest. All the while, Cam and Isaiah’s relationship grows increasingly tense, as Isaiah teaches Cam what he will have to give up to become the greatest. The concept of being the Greatest of All Time, or the “GOAT,” is a prevalent motif

throughout this film, alongside extremely similar descriptions of success such as becoming “Him” (or, in other words, becoming the best). Both “GOAT” and “Him” are terms whose origins are tied to Black athleticism. The former originated with Muhammad Ali, and has since been used to describe athletes like Michael Jordan, LeBron James and Simone Biles. “Him,” often used in the phrase “I’m him,” was popularized by Odell Beckham Jr. in 2019. Given that professional American football is a majority Black sport filled with some of the highest-achieving athletes in the world, it’s no surprise that “GOAT” and “Him” soon found their place on the field. But for everything the words celebrate, it also casts a veil over the debilitating pressure haunting Black athleticism. Players work

toward unattainable standards of perfection, conditioned to believe that all their work is meaningless if they cannot be The Greatest of All Time. Throughout Isaiah and Cam’s training, these terms consistently arise. Cam’s greatest motivation is his family — particularly his deceased father, who introduced him to the sport at a young age — as well as the idea of being the greatest. Isaiah sees Cam’s love for his family as a weakness, emphasizing that if Cam truly wants to be the GOAT, he will need to stop caring about everyone and everything. These all-or-nothing conversations between the two raise the stakes and eventually reveal more and more of the league’s cult-like influence.

ISABELLA CASAGRANDA Daily Arts Writer

Searching for chic nails in Ann Arbor? Look no further than Ally Cool Cat, a nail artist who has amassed more than 216,000 followers on Instagram for her incredibly intricate nail sets. Ally, University of Michigan Stamps School of Art & Design alum, creates and mails out press-on nail sets entirely on her own, and has created scenes that depict everything from Lorde songs to floral fantasies. She’s not alone, either. In recent years, online nail art has exploded; now, business is booming. In an interview with The Michigan Daily, Ally Cool Cat described how she was driven to start her business through her own dissatisfaction with the limited designs offered in most salons.

“I saw an image on Pinterest,

this really simple design: a nude color base with black stars painted on top. … The thought of presenting one of the nail techs at the salon with that image, I just felt like I could not do that” Ally said. “At salons, it’s pretty basic, just a flat color and maybe a French tip. So I just went online on Amazon and bought an at-home nail kit for gel. And I just did it myself!”

The support of her friends, who would let her practice on them, fueled her hobby, which eventually grew into a self-made business. According to Harper’s Bazaar’s Arabelle Sicardi, the nail art explosion has been a long time coming. Acrylic sets first appeared on the market in the 1950s, and eventually became an important form of cultural expression within Black and Asian communities, who have been pushing the boundaries of nail art since the medium’s creation. Nails are now crucial aspects of runway

looks around the world and even on display in museums – Sicardi highlights Bernadette Thompson, who became the first nail artist to have a museum exhibit of her nail designs at the MoMa. But Sicardi credits the most recent uptick in nail art to the COVID-19 pandemic, when, in the absence of salons, press-ons became essential for those who wanted expertly crafted acrylics. The press-on nail side of

‘Haunted Hotel’: Frights and delights

ANA TORRESARPI

Daily Arts Writer

Content warning: This article contains mentions of suicide. Spoilers for “Haunted Hotel” season one. The beginning of “Haunted Hotel” plays like the ending of every horror movie you’ve ever watched: A young girl sprints down an eerie hallway, screaming as a ghostly figure chases close behind. She hastily turns a corner and trips, turning to look at her pursuer before he sinks a knife into her back. Only this time, the girl doesn’t scream, but laughs as the knife goes straight through her without leaving a mark. It turns out her “killer” is really a harmless ghost, and she just loves messing with him. This little girl is Esther (Natalie Palamides, “The Real Housewives of Shakespeare”), a mischievous kid who just moved into her new, extremely haunted home and is enjoying the undead company. Her unorthodox introduction serves as the perfect embodiment of Netflix’s new animated comedy, “Haunted Hotel.” The show revels in using typical horror tropes to propel its comedy, blending morbidity and absurdity together. With a plot coming straight out of “The Shining,” the series spends more time poking fun at its horror elements than intentionally scaring its audience. Although the name gives it away, “Haunted Hotel” is about a family living in an enormous, rundown hotel in the middle of the woods.

The show centers Katherine (Eliza Coupe, “Happy Endings”), a single mother who recently inherited the Undervale Hotel from her

deceased brother, Nathan (Will Forte, “The Last Man on Earth”). The catch? The hotel runs rampant with demons, monsters and ghosts — including Nathan himself. Katherine is left to raise her kids, Ben (Skyler Gisondo, “The Righteous Gemstones”) and Esther, deal with her dead brother’s ghost and somehow turn a profit from her new hotel business all on her own. Nathan, lacking any corporeal vessel on this mortal plane, can only watch and give terrible advice from the sidelines. Meanwhile, Ben and Esther navigate the paranormal and do what any other kids in their situation might do — practice black magic and date ghosts. On top of all that, living with the family is Abaddon (Jimmi Simpson, “Dark Matter”), a demon trapped in the body of a little boy that has been tormenting the entire town for centuries.

Every character has their own charm that breathes life into the series. Esther’s love for black magic and her general air of mischief is endearing and entertaining, while Katherine’s immediate exasperation at the supernatural is a fun foil. Nathan’s carefree energy and identity as a ghost also brings a unique dynamic to the table. But, hands down, the best character (and arguably the best element of the entire show) is Abaddon. Dressed in the clothes of a 10-yearold pilgrim, he is capable of great atrocities while simultaneously not knowing what a computer is or how to tie his own shoes. This cast of endearing characters really set the tone for what “Haunted Hotel” brings to the table.

Every episode features a new scare, ranging from a soul-eating angler fish to “Gremlins”-esque

“rollyfluffs” to the actual end of the world. With only a short, 10-episode debut, the show takes great lengths to introduce as many novel ideas as possible, allowing it to exhibit its narrative potential while keeping audiences interested. With so many out-of-the-box ideas, it’s hard to imagine getting bored.

That being said, there are moments where this strategy hinders the show’s overarching integrity. With only 10 episodes at its disposal, all of which try to jump into new ideas and scares, the show tends to abandon its original premise in favor of showcasing its creative potential. Although the show introduces Katherine’s struggle to book guests and manage the various supernatural beings in the hotel as the focal point of the series, it’s hardly recognized in any episode after the pilot. There isn’t a single episode that hinges on Katherine’s ability to ward off or hide ghosts from any prospective guests, which just feels like a missed opportunity to lay a foundation for the show’s episodic formula.

While “Haunted Hotel” never wavers in its quality of humor, there are times when the show struggles to maintain a consistent tone. Most of the time, the series takes a lighthearted approach to its characters and storytelling, which complements the comedy and makes the more horrordriven scenes pop. However, the later episodes show a desire to be more mature and nuanced. While it’s definitely an interesting avenue to pursue, introducing darker themes after building a consistently playful tone in the first half felt very disjointed.

CONTINUED AT MICHIGANDAILY.COM

Wajahath/DAILY

the industry, and the internet, has continued to surge in popularity since then.

Ally Cool Cat used that creative independence to her advantage. She initially viewed her nail art business as a side hustle, a way to make money during her time in college. But soon, she found personal value in the medium.

“I was in art school (at the Stamps School of Art & Design) and I was

really focused on printmaking, which is a pretty physical medium and labor,” Ally said. “And then that was gone. So I really threw myself into nail art. Rather than trying to make a profit off of the set, it became, ‘I want to make something that I really love and use this as a form of creative expression.’”

Entrepreneurship comes with its challenges, the biggest of which is the time commitment, which Ally also discussed.

“It’s a pretty long work day, usually six to 12 hours,” she said.

“It is so time-consuming. If I’m being completely honest, I spend almost every day at home working on (nails). I’m lucky enough to be able to do this as my full-time job, but it is all I do. I see friends when I can here and there, but my mind is always on this and I’m always doing this. And it does get a bit overwhelming. When orders pile up, it gets so stressful.”

But she doesn’t let that get her

down. The core of Ally Cool Cat’s business is a positive attitude.

“When you do what you’re passionate about, you enter that zen state where it really goes, and you’re in this mode of relaxation” Ally said. “It doesn’t feel like a lot, but it is a long time.”

Ally Cool Cat has to make sure her social media stays up to speed, too. At the beginning, when she had to exclusively make commissioned designs instead of following her own artistic endeavors, finding inspiration was a challenge.

“Sometimes it makes me feel a bit anxious that I can’t keep up with it — the trends and stuff on social media,” Ally said. “I really try to remember it’s not about the likes and the followers, even though I love them. I just try to remind myself that as long as I’m still doing what I love to do, it’ll be okay. It’ll work (itself) out.”

CONTINUED AT MICHIGANDAILY.COM

Plant ___ of hope 8. "___ we all" (everyone agrees) 9.

Edited and managed by students at the University of Michigan since 1890.

Stanford Lipsey Student Publications Building

420 Maynard St. Ann Arbor, MI 48109 tothedaily@michigandaily.com

ZHANE YAMIN AND MARY COREY Co-Editors in Chief JACK BRADY AND SOPHIA PERRAULT Editorial Page Editors

Mateo Alvarez

Zach Ajluni

Angelina Akouri

Jack Brady

Gabe Efros

Lucas Feller

FIONA LACROIX AND CECILIA LEDEZMA Managing Editors

EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS

Liv Frey

Seth Gabrielson

Tom Muha

Sophia Perrault

Hunter

Lindsey

Zhane

Unsigned editorials reflect the of f icial position of The Daily’s Editorial Board. All other signed articles and illustrations represent solely the views of their authors.

Dearborn isn’t oppressive

ARIANNA MEHMOOD Opinion Columnist

Church bells ring without question, but when mosques share their call to prayer, the country paints it as controversial. In America, one sound is considered a tradition while the other is disruptive. Viral TikTok videos and media stories surrounding the broadcasting of the Azaan — the Islamic call to prayer — in Dearborn have highlighted the rise in Islamophobia and misrepresentation of Muslim communities. Critics claim that the loud noise from the announcement is pressuring the community to craft their daily routines around the Islamic tradition, contrasting with traditional American ideals of freedom of religion and cultural coexistence.

Online videos have gained significant attention, instigating deep tensions within the community. Multiple non-Muslim residents have shared clips of the Azaan echoing around 5:30 a.m.

during the Fajr prayer, noting it as a disturbance rather than a moment of faith. The comments under these posts often spiral into outrage — many users claiming that Dearborn is being taken over or implying that Islamic practices are incompatible with American culture. This even connects the issue to the so-called liberal propaganda in America. As a result, Muslim residents are being villainized for exercising their faith, without forcing it on anyone.

Some argue that the Azaan exceeds the city’s decibel limit. This is true in a few isolated instances and may momentarily disrupt the morning routines of residents. Dearborn has a limit of 55 decibels at night and 60 decibels during the day. After the recent uproar, city officials have conducted tests that show that many of these mosques are actually operating under permissible noise levels, suggesting that for most residents, the nuisance is minor or nonexistent. While a few have surpassed the limit, it is ultimately up to the city to find a balance that

allows the Azaan to continue as a protected religious practice while addressing the lawful concerns regarding sound.

Debates over the Azaan have led to larger discussions about religious freedom in Dearborn.

One social media user shared a video of Dearborn’s largest mosque surrounded by several churches, arguing the setup proves the city’s imbalance and lack of recognition for Christian beliefs. Her framing, however, misses the point entirely. The coexistence of churches and mosques side by side is a visual representation of what America strives for: freedom of religion and a diverse nation. The user points out how the mosque caters to more than 3,000 worshippers, but that simply mirrors Dearborn’s population demographic, where a significant number of residents are Muslim. The mosque’s large architecture isn’t to assert dominance, but rather to accommodate the community’s needs.

CONTINUED AT MICHIGANDAILY.COM

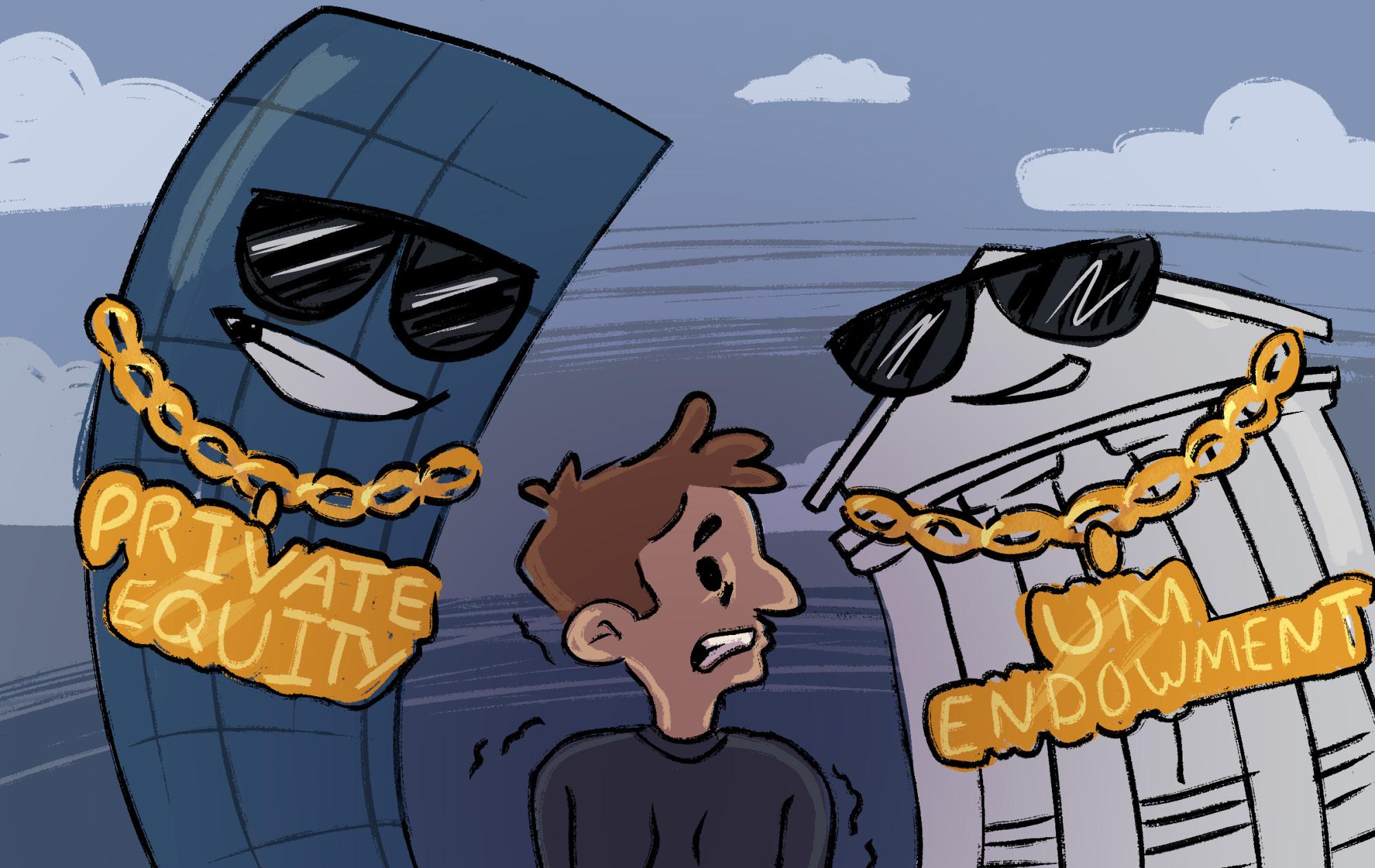

University of Michigan students are no strangers to high rent prices. Ann Arbor is one of the most expensive college towns in the nation, with the average rent hovering at about $2,060. For many students, housing consumes the majority, if not all, of their budget. Students tend to attribute these rising prices to a number of things — general inflation, lack of Universityowned housing, a rising student population and greedy landlords to name a few. All of these are true to some extent. But there is another force quietly reshaping Ann Arbor’s rental market — private equity. Private equity is not only buying up student housing and increasing rent, but also decreasing the quality of the housing itself. What makes this trend even more troubling is the University’s own financial entanglement with private equity. The University has already committed portions of its multibillion-dollar endowment to private equity firms, which are not on their face a bad thing, but something that demands far greater scrutiny. Private equity’s expanding role in Ann Arbor’s student housing market raises the risk that the University may be directly profiting from practices that make life harder for its own students. And with 39.4% of university endowment money invested into private equity and venture capital companies, the greater U-M community deserves to know whether the University is indirectly funding these predatory companies. The

University of Michigan must be transparent about where its endowment’s private equity investments go to ensure it isn’t profiting from practices that harm its own students and that raise broader social equity concerns.

Simply put, private equity is a way for firms to invest in private companies that are not on the stock market. Firms raise capital from institutions and accredited investors, pool that money into a limited liability fund separate from the firm and use it to buy companies to resell them for profit. To maximize returns, these funds typically strip assets, cut jobs and extract fees for their own management services while saddling these companies with debt. For example, a common practice of private equity companies is to sell off a newly acquired business’s land, which is often the biggest asset of a company. Then, that same land is leased back to the company, where they are subject to uncontrollable rental prices. Many of the acquired companies eventually collapse under these pressures, but because of the legal structure of private equity, the firms themselves avoid accountability. Private equity targets a broad range of industries from retail to healthcare and in 2024, played a role in 56% of corporate bankruptcies in the United States despite accounting for only 6.5% of the national economy. Now, there’s a growing private equity footprint in student housing. On campus, private equity firms own Willowtree, The Courtyards, Campus Edge Ann Arbor, Varsity, Saga, The Yard, Six11, Sterling Arbor BLU and Landmark, totaling 1,804

Trump’s

EMMA MARGARON Opinion Columnist

Normally, a celebration is appropriate when a class assignment isn’t available, but when my professor told us that our class couldn’t access Arctic ice and sea levels data because of the government shut down, no celebration was in order. Instead, the class felt confusion and a sinking recognition that political agendas are affecting our academic resources. Since Oct. 1, the current government shutdown has resulted in widespread restrictions on government websites. These restrictions are part of a concerning trend of the Trump administration: the disappearance of public data. The rise of inaccessibility to public data is a major threat to maintaining societal health, government transparency and environmental justice.

When attempting to access various government websites, a message appears stating that the government shutdown because of Democrats. The blame on one party is an unethical, deliberate misdirection by the Trump administration. The actual reason for the 2025 government shutdown was a disagreement between Democrat and Republican representatives on a bill related to funding government services. Some environmental websites that show this message and now aren’t fully accessible include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture — all crucial inlets to research and information.

The shutdown amplifies the fact that government data is disappearing, but this is not a new occurrence for the Trump administration.

In the first 100 days of office, Trump’s changes to 70% of government environmental websites include modifying content, focus or links with a specific decrease in information pertaining to climate and environmental justice. Since February 2025, more than 8,000 pages from various government websites, ranging from scientific research to justice issues, are absent from public sites. In their Library Research Guides, the University of Michigan writes:

“It has become increasingly common for government data sets that were previously publicly available to be removed. Some of these datasets may be altered and made available again, while others may remain offline indefinitely.”

This disappearance of data isn’t a stunt specific to this year. Immediately after Trump’s inauguration in 2017, the administration began removing all climate-related data from the official White House website. This kind of denial of public access to government information and data is a pattern of the Trump administration.

Government-funded data and research is vital to public health and protection. Scientists, communities and government employees use this data daily to track and respond to environmental threats involving air, water, forest and other natural systems.

Caren Grown, senior fellow in the Center for Sustainable Development at Brookings,

emphasizes the importance of data in our age.

“I think reliable statistics collected, financed by governments, but open, accessible, transparent, are a public good,” she claims. “Effective policymaking relies on accurate and timely data, as I said, that are open and accessible not just to government agencies, but to international organizations like UNICEF, for instance, or parts of the UN system, to academics, like I mentioned, to journalists, to civil society organizations. Reliable and timely statistics are a tool of accountability.”

As Grown dictates, data is essential to instigating policy changes. When it comes to the environment, scientific policy makers combat climate change by monitoring data on environmental barriers such as resource quantities, pollution, droughts, deforestation patterns and temperature fluctuations. Sustainability methods develop from this data analysis so it is critical for progress in protecting the environment. More than 100 climate studies came to a halt this year due to the Trump administration. Restricting publicly funded research is a step backward for democratic society because it is a political move that supports Trump’s agenda. The country’s biggest authoritarian doesn’t want new environmental policies to exist from this data, so he continues to restrict and delete. When there is a government shutdown, the Trump administration gains another opportunity to quietly stall environmental progress by taking down data related to the environment.

CONTINUED AT MICHIGANDAILY.COM

units. In order to rapidly double or triple their investments, they often raise rent, fees and evict residents. This has led to rent hikes of 26% over three years, which far outpace regional increases of 13%. As a result, students are suffering, in part because of investments in private equity. The higher the rent students pay, the more money private equity firms and their investors make, which could include the U-M endowment, given the lack of transparency and accountability from the university.

The University risks harming its reputation if it doubles down on strategies increasingly seen as at odds with academic and social responsibility through broad-level private equity

investment. The current University endowment policy is to generate the most money possible in concurrence with the University’s goals in teaching, research and service. Housing insecurity undermines academic success, mental health and equity on campus. The University of Michigan should not be actively investing in the forces creating it. Investing in companies actively hurting students, or other populations for that matter, does not support the University’s mission and therefore should not be welcome in the endowment.

However, if the university is not moved by its moral responsibility to divest from private equity, it should be moved by the financial one.

Private equity investments often lock funds away in long-term structures with limited access. As President Donald Trump’s administration continues attacks on higher education and calls to tax endowment funding, universities are quietly selling off their private equity stakes, anticipating the need for more liquid assets. The University of Michigan should follow suit as costs increase. Additionally, these investment returns are only really good on paper and hard to estimate until the PE firm actually exits its position, which is normally 5 to 8 years after the initial investment. As these investment activities slow down, exiting them will become harder and offer smaller returns. The University of Michigan

should commit to endowment transparency by publishing information about its private equity partners and the industries they invest in. A clear outline would send a signal that the institution takes its social responsibilities seriously. At the end of the day, students should not have to wonder whether the institution they attend is making a killing from their rising rent. If the University continues to profit from private equity’s dominance in student housing, it risks further eroding trust and deepening inequality. For a public institution that prides itself on affordability and access, continuing down the private equity path without greater scrutiny is both financially risky and ethically unsound.

Why Ann Arbor’s Vision Zero falls short of protecting U-M students. And how to fix it.

MADELEINE BURKE Opinion Columnist

Whether attempting to get to a library, a dining hall or an academic building, crossing busy streets is a common occurrence for students at the University of Michigan. In fact, U-M students are the most prominent pedestrians and cyclists in the city. While students rely on the safety of these streets, the number of pedestrian and cyclist crashes in Ann Arbor is at a high. According to Ann Arbor Police Department reports, there have been two fatalities and 11 serious injuries caused by these crashes in 2025 so far — the highest number since 2014. To top it off, Washtenaw County is the most collision-prone county in the state of Michigan, with Ann Arbor being one of its major cities. In an attempt to address these safety concerns, the Ann Arbor City Council formally adopted Vision Zero in June 2021, intending to eliminate pedestrian crashes by 2025. While this policy has ambitious goals — such as reducing speed limits, creating safety infrastructure for cyclists and filling sidewalk gaps — Vision Zero is ultimately insufficient due to a lack of motivation among elected officials to enforce it and weak public advocacy. To properly address Ann Arbor’s crash problem, Vision Zero’s road safety initiatives need to become the top priority for City Council members and their constituents. Some of Vision Zero’s main objectives are to create pedestrian zones, add bike lanes and construct curb extensions. These additions are necessary to promote road safety for pedestrians by giving them safer places to walk, bike and cross the street. However, these additions would take away space from metered parking spots that generate revenue for the city. There’s profit in parking — there