HOW BORING would life be without rivalries? Imagine Superman without Lex Luthor, Batman without the Joker, the X-Men without Magneto.

Democrats without Republicans. (Ah, for the days of my misspent youth, when fictional villains, not real politicians, represented the biggest threat to humankind.)

Without a foil—an arch-enemy or merely someone who holds a slightly different opinion—all of us could amble along our cozy little identical paths, never arguing, never gossiping, never having to defend the universe from the Ultimate Weapon of Doom. Our lives would be so much simpler and less stressful.

Here’s the thing, though: Without friction, progress doesn’t happen. Since time began, all great inventions—fire, the wheel, deep-fried pickles—came about because someone questioned the status quo and presented a radical alternative. Over time, radical alternative built upon radical alternative until we arrived at space travel and thermonuclear weapons. (Granted, some radical ideas were better than others.)

The cannabis industry is no stranger to friction, foes, or radicalism. In fact, the proto-industry consisted entirely of stressed radicals hiding from their archenemies. While that relationship has mellowed somewhat, rivalry has arisen in other areas—like between outdoor and indoor growers.

Both cultivation methods have their devotees. Fans of sun-grown flower insist terroir is the defining factor in creating distinctive terpene and cannabinoid profiles, much as terroir determines the essential nose and palate of fine wine. Indoor-flower fans, on the other hand, declare only by controlling every aspect of a plant’s environment can a cultivator produce the ultimate cannabis experience.

Potato, potahto.

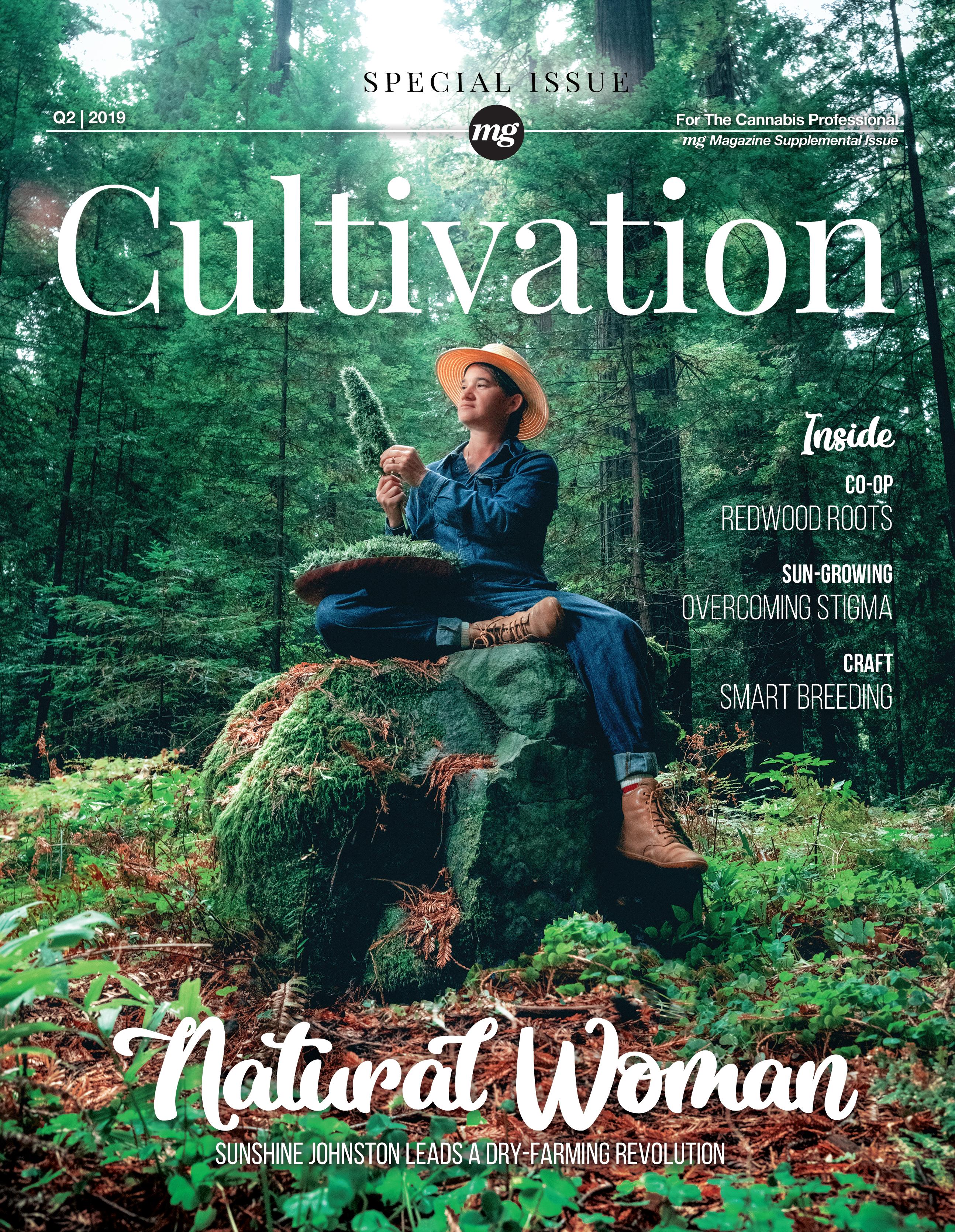

The interesting—and important—thing about the friendly rivalry is the way friction pushes both sides to up their game. Every season, growers in both camps make progress in the art and science of cannabis production, developing new methods, new strains, and new market approaches. Some, like Sunshine Johnston, have discovered the best way to move forward is to take a step back. Experimentation led her to the realization the best thing she can do for her plants is let Mother Nature tend the crop. Others, like the Redwood Roots family of farms, are redefining independence. Then there are keepers of the flame, like Kevin Jodrey, who believes classic genetics coupled with modern science and traditional growing zones represent boundless opportunity.

Radical ideas, all of them—and progressive.

Friction can be a very good thing. Bet Superman wishes his rivalry with Lex could be so productive.

Kathee Brewer Kathee@cannmg.com

Q2 Supplemental Issue mg Magazine, April, 2019

DIRECTOR OF CONTENT: Kathee Brewer

CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Angela Derasmo

COPY EDITOR: Erica Heathman

CONTACT: editorial@cannmg.com

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Tom Hymes, Chris Jones

ADVERTISING & MARKETING

CLIENT MAGAGEMENT

Brie Ann Gould: Brie@cannmg.com Hope Gainey: Hope@cannmg.com

Meghan Cashel: Meghan@cannmg.com

General Inquiries: sales@cannmg.com

PHOTOGRAPHY

Cover Photo: Phil Emerson

OUR DO NO HARM MANTRA IS THE CORE OF OUR BUSINESS VALUES. We all share the common goal of working smarter to reduce our carbon footprint with suppliers, customers and employees dramatically reducing waste to landfill, significantly cutting paper and material usage complying with environmental standards and programs that helps us achieve this mission. We only use recycled papers and soy based inks on our printed products WHENEVER POSSIBLE.

The humble dry farmer has a formidable message of quality for the world.

BY TOM HYMES

WITH CALIFORNIA’S permanent cannabis regulations recently finalized, licensees have a stable foundation of compliance upon which to build their branding and marketing, which is precisely where a lot of energy is being focused as 2019 gets underway. No region feels the pressure to brand more than northern California, and perhaps no county has more branding expectations placed on its shoulders than Humboldt, where cannabis courses through the body politic.

Sunshine Johnston is one farmer who has spent years preparing for just this moment. The owner-operator of Sunboldt Grown Farms dry-farms 10,000 square feet along the

weekly cannabis show on KMUD. “My mom was one of the founders,” she remarked of SoHum’s storied community station.

She’s made time to do all of this as a one-woman band, singlehandedly building a business and brand from scratch, which has meant reinventing herself while simultaneously remaining true to herself and the community that raised her.

“My mom’s generation felt let down by society primarily because their leaders at the time were assassinated; students were killed at Kent State,” she said. “They got kind of upset and just wanted to live outside society. At the same time, they did something unique by

Eel River. Arriving in southern Humboldt at the age of seven, Johnston said she was raised by activists and artists in the community where she started farming with her mother. “We grew to save redwood trees and to help indigenous people,” she said.

Johnston still touches the plant every day and said it defines her. “It’s my existence, my identity, who I am, and what I’ve been doing,” she said. “I think it may be because my mom looked at it in a very spiritual way, all those hours listening to Bob Marley as a kid, all the activism.” She paused. “It gave me a sense of freedom and independence I am very grateful for.”

Johnston lives with her husband, Eric, in Redcrest, where she is an avid farmer laserfocused on building a successful brand and a perennially active member of a community with which she closely identifies. A former board member of California Cannabis Voice Humboldt, she regularly attends meetings of the county board of supervisors to speak on behalf of craft cultivators, is a frequent speaker at industry trade events, and hosts a

starting their own institutions—community centers, a credit union, community schools where parents would help teach the children. There also was a health center started as a result of herbicide spraying by the lumber industry making people sick. There was selfreliance and a do-it-yourself attitude.”

They are qualities Johnston carries forward. “A lot of my motivation is just taking ownership. I feel an obligation to make it; to be successful. I have a responsibility to represent my community.”

Johnston has a cool expectation of fame, which might come off as arrogance if she didn’t really know her shit—and not just as a Humboldt-bred cultivator. She also brings years of experience as a local wine broker to the table, invaluable knowledge that gives her a decided advantage in the marketplace.

“What has been a major strength for me has been the ten years I spent brokering wine,” she said. “I’ve brokered for lots of

small wineries. They have the same issues with distributors and getting paid as cannabis cultivators do. They also have problems getting on the [store] shelf and getting their stories told.”

But her wine experience also gave her something potentially priceless in the cannabis world. “Through that process of selling wine I developed a palate, particularly of flavors,” she explained. The skill came in handy when she started breeding strains a few years ago.

“In 2015, I knew I needed a portfolio of genetics, so I just jumped right into it,” she said. “I started doing crosses and had my own breeding program.” She didn’t take breeding very seriously at first. “I just wanted to make nice flavors and build a portfolio, but other breeders started taking me seriously, I think because I have a palate and I’m able to create flavors,” she explained.

Now she sees her “vintner’s palate” and the benefit it gives her as a cannabis breeder to be a marketable asset. In 2018, she farmed three of her own original strains: Loopy Fruit, Wonderlust, and Chronic Freedom. “This year it really struck me that I have a strength here that I need to make a part of my company,” she said. “That’s great, because I really do enjoy it.”

“I was previously known for having good herb,” Johnston said of life before she founded Sunboldt Grown. Little has been the same since. “I started the company in 2015, and it has been nothing but [research and development] for me ever since,” she said. “It’s not easy to do, but I’ve created a brand with no product. I’ve created demand with no product. If there was anyone who could do it, it was me. All my moves were for one thing and one thing only, and I take it very seriously, and that is going to market. The reason I wasn’t making money in 2016 or 2017 is because I was preparing to go to market in 2019. That’s what I was doing and what all my moves were about. It just takes time.

“There is more to it than flower,” she continued. “Genetics was a big part of it.” She also made a “smart move” in 2017 when she partnered with Nasha to provide flower grown to maturity specifically for hashish. “I had done a little bit of work with Barron Lutz from Nasha, who does bubble hash, and I approached him and asked him to take half my crop,” she said. “No one had ever

approached him like this. He looked at me and his first response was, ‘I can’t do that.’ ‘Why not?’ I asked him. ‘I don’t know what to pay you.’ ‘Don’t worry about it,’ I said. ‘We’ll figure it out later.’”

Johnston’s explanation for why she gave Lutz the benefit of the doubt speaks volumes about her business acumen and her people smarts. “The reason I said that was because I watched him pound the pavement and get his product into all these shops the year before, and I knew he had good retail relationships,” she said. “His sales rep down here, who was also his brother-in-law, was going to shops once a week, and I knew that if you’re going to a shop once a week, you’re more likely to get sales and get paid. I knew that was a successful model, and I knew that in 2019 I would need retail partners. He would cobrand me and get me into all these shops. I didn’t have a license, a permit, or anything, and I went for it.”

In the end, the idea worked. “It’s proving itself because bubble hash, unlike distillates or these other types of extracts, shows off the

farmer the best,” she said. “You can’t really cut corners like you can with these other things, because you need oil, and to get oil you need to get ripe. The one thing I could say to Barron very convincingly was, ‘I can let things hang. I let things get ripe.’ We didn’t know the oil yields of my genetics, and that was a risk right there for the both of us, but it worked out.”

For his part, Lutz holds the quality of flower he gets from Johnston in very high esteem and is not shy about saying so. At The Emerald Cup in December, when asked what he needed to scale up his own production, he replied, “Twenty more Sunshine Johnston farms.”

Johnston is no less appreciative of Nasha’s product. “I really value the hash because it’s whole-plant medicine, and I feel it shows what I do the best,” she said.

So, what exactly does Johnston do on her dry farm that produces such quality flower? Not much, she said. “I would describe myself as a do-nothing farmer, which stems from The One Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming,” she said. Written by

I define craft farming as the cannabis being the artist. It creates me. I am crafted by cannabis. I don’t craft cannabis. I get to be the artist with my branding.

—Sunshine Johnston, owner, Sunboldt Grown Farms “ “

Masanobu Fukuoka in 2009, the book describes the author’s “do-nothing” technique, which was described by the New York Review of Books as “commonsense, sustainable practices that all but eliminate the use of pesticides, fertilizer, tillage, and perhaps most significantly, wasteful effort.”

Johnston continued, “It wasn’t until after I had started dry-farming and not using fertilizer that I realized that was what I was doing. A do-nothing farmer is like the concept of ‘do no harm’ by letting nature do the work.”

Half her crop was dry-farmed in 2018, and she was “just stunned at the results.” The plants that were watered were very uneven, but the plants without water flourished.” Now she’s hooked. “All of us who dry farm are very enthusiastic [about it] and want everyone else to dry farm, too,” she said.

“All I’ve been doing is strategizing, and now I’m closing a chapter and starting a new one,” said Johnston. “Once I go to market,

EVER VISIT a sushi restaurant and wonder whether the “red snapper” on the menu might be tilapia grown on a fish farm in parts unknown? In both the black and legal cannabis markets, it’s a more convoluted game of bait and switch. Brokers and retailers will do whatever it takes to move product, so if that bag of “Kush” needs to be an “OG” to fill an order, then how does “Humboldt OG” sound?

Even more scandalous is the pernicious, long-standing practice of brokers selling cannabis grown outdoors as “indoor.” In doing so, brokers and retailers have been able to double-down on their profits by claiming outdoor weed is inferior and then selling their outdoor flower as “premium” indoor cannabis. For years cannabis patients and consumers have been sold on the idea indoor cannabis is a superior product. For thousands of outdoor growers, it will be both a challenge and an opportunity to persuade consumers otherwise as the sun-grown market takes shape. Meanwhile, farmers are finding new and creative ways to market their flower and forging important new partnerships that could help them survive in cannabis-flooded regional markets.

Worldwide, the legacy of cannabis is tied to plants that were grown full-season outdoors, contending with wind, weather, pests, animals, and other threats. Through experimentation and patience, farmers successfully have planted strains from one part of the world in similar climates and latitudes around the globe. In particular, the cultivators in California’s Emerald Triangle have grown and bred strains from around the world since the 1960s, when the “back-to-the-land” movement took hold in Northern California and pioneering

BY CHRISTOPHER JONES

farmers started mixing cannabis in with their backyard gardens.

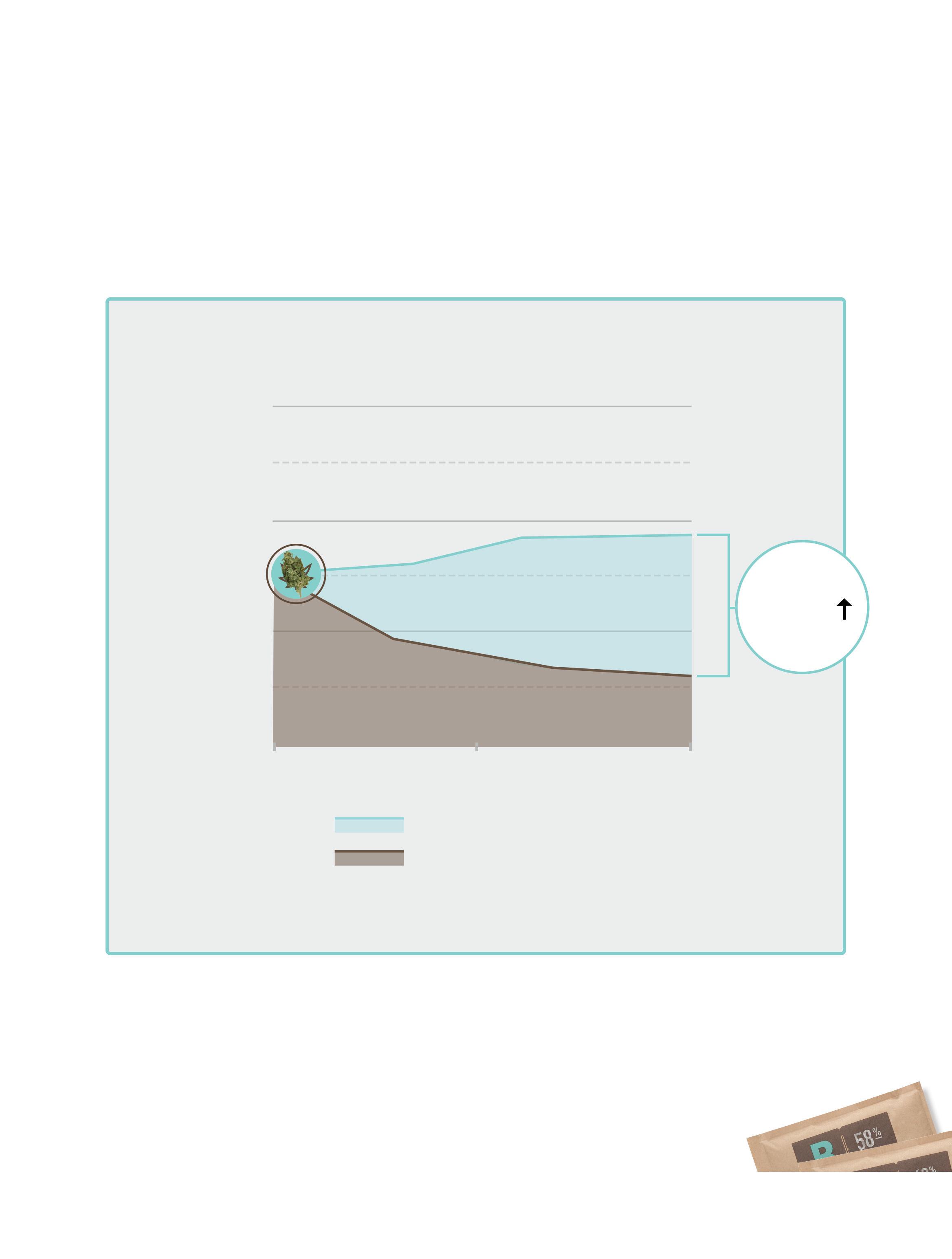

Today, cannabis grown full-season in the great outdoors—or “sun-grown,” as it is marketed—represents a unique opportunity for farmers who have the experience and tenacity to nurture fickle plants over a six- to eight-month rollercoaster of a season. Veteran farmers and aficionados still consider highquality sun-grown herb some of the tastiest and most effective medicine, with high concentrations of terpenes and a rich spectrum of cannabinoids that result from exposure to the full spectrum of the sun’s rays for months on end. From a sustainability standpoint, too, sun-grown cannabis is a clear winner. But in today’s hyper-competitive, highly-regulated industry, most sun-grown small farmers are fighting an uphill battle.

Shivawn Brady is the vice president of regulatory affairs at Justice Grown, a cannabis company with operations in a half-dozen U.S. states, and a member of the Sonoma County Growers Alliance. Over the past decade, she has consulted on cultivation projects nationwide. She explained one of the biggest challenges for sun-grown cannabis farmers is the lingering stigma associated with the practice, even in California, where more than half of counties ban sun-growing. Nationally, most states require cannabis be grown indoors or in greenhouses. Taking a high-level, long-term view of cultivation in the United States, Brady sees opportunities for outdoor cannabis cultivation in the future but she believes the practice always will be concentrated on the West Coast.

“I could see outdoor cannabis cultivation in states with hemp programs and a rich history in agriculture. But if there is hemp, then cannabis growers see a risk [of cross pollination],” she said. “I’m also hearing from folks that paranoia about outdoor plants is

too fierce right now in other states, but as anxiety falls, we might see [willingness to allow outdoor grows] open up. There is a lot of recognition of how much energy indoor systems use, and there is no reason we should be doing so much. So, as consciousness shifts and people start to understand these [outdoor] facilities aren’t a public safety issue, we will start to see more farms across the U.S.”

While there is little doubt farms in the Emerald Triangle have advantages in terms of legacy, genetics, experience, knowledge, and a number of other intangibles, bigger market forces are at play. In California, several regions of the state are prime areas for cannabis farming, and investors are placing big bets on large-scale operations. Almost any region where wine grapes grow provides a good environment for cannabis, because the plants thrive under the same conditions: hot days, dry summers, and cool nights.

Whether large or small, one of the biggest challenges for sun-grown farms is the glut of weed on the West Coast that has forced prices down to unprecedented levels. In Washington and Oregon, the average price for sun-grown cannabis has been cut in half over the past two years, from about $1,500 per pound to between $700 and $800 per pound. At the bottom end of the flower market, manufacturers of oils and extracts pay farmers as little as $50 per pound. In 2017 alone, Oregon growers produced 1.1 million pounds of flower, according to state regulators. Of that total, it’s estimated less than half was sold and consumed in the legal market.

Now that California’s regulated recreational industry is up and rolling, the state’s 3,000-plus licensed growers are expected to produce several million pounds of flower annually, and the competition for shelf space and survival is sure to be intense.

In every legal state, indoor flower accounts for the vast majority of plant product sold at retail. However, craft cannabis farms on the West Coast have begun marketing “sungrown” flower and extracts to appeal to the same consumers who shop at organic markets and support environmentally conscious companies. Outdoor strains that have been grown for decades in the remote mountains and valleys of California and Oregon exhibit THC and terpene levels that rival or exceed indoor strains.

So the challenge now is to sell new consumers and patients on the unique, nuanced qualities of sun-grown cannabis and its rightful place in the market. Tina Gordon, founder of Moon Made Farms in southern Humboldt, relishes the task.

“Cultivating in full sun is the sum of all the parts—full sun, night sky, fresh air and water—and it’s the soil native to this area that is nurtured, and so there is a lot of intention to how the plants are cultivated,” she said. “With indoor[-grown], you have artificial light, municipal water, and a simulation of the natural environment. So, it’s easy for people to understand how and why

ingesting sun-grown is better for them than ingesting indoor.”

In order to help market sun-grown cannabis in Oregon, the Oregon SunGrowers Guild began hosting the Terpene Cup competition in 2016 to recognize and reward some of the best outdoor growers in the state. Sun-grown cannabis typically has more robust and complex terpene profiles than indoor cannabis, and the competition provides a platform for highlighting the desirable characteristics.

Among the ways sun-grown farms have been able to hedge their bets amidst the glut and declining prices is selling large portions of their crops to manufacturing labs. The labs turn the raw biomass—trim, smaller buds, and even whole plants—into distillate and extracts. Growers even have begun planting specific strains that produce lab-coveted terpenes and packaging their biomass in different grades for different manufacturing purposes.

Nate Ferguson, a master extractor and co-founder of Jetty Extracts in Oakland, California, said his company sources about 20 percent of its biomass from sun-grown farms, but some of the best-tasting and -smelling

cannabis he has seen lately comes from mixed-light greenhouses. He explained sungrown plants are at the mercy of the elements and more susceptible to mold, and thus can be difficult to source on a consistent basis. By contrast, greenhouse operations have more control over their environments—dialing in temperature, humidity, pest management, and other variables—and produce, on average, three harvests a year.

“When we first started, we were getting the trim the farmers dumped over the hill, but now we’re doing contracts where we get the whole plants, which is great because we are extracting twice as much in about half the time,” said Ferguson. “For more of a flavordriven product, a lot of the fruity strains are good for extraction—the Clementines, Tangies, Jacks, and high-limonene strains. The earthy strains are darker [and thus less desirable] and more finicky, so it all depends on what you are going for.”

Also an issue for small, sun-grown farms: Many retailers operate their own flower cultivation facilities, making competition for shelf space a growing challenge.

“This is a tough thing for a lot of the [Emerald Triangle] folks,” Ferguson said. “Guys are coming up from San Luis Obispo, Salinas, and Santa Barbara and offering as

low as $300 for a whole-plant pound. For the boutique-y, craft guys in the Triangle, we see prices anywhere from $300 to $1000.”

Debate within the industry encompasses two competing philosophies about the best way to structure a business in today’s hypercompetitive climate. Some argue having a vertical operation that includes everything from indoor-outdoor grows to manufacturing labs and retail shops is the way to win. Others insist specializing in excellence and consistency in one area of the supply chain is the best way to survive and thrive as the industry grows.

After growing medicinal product for ten years, Oregon’s Grown Rogue ventured into the recreational market and now is one of the bigger vertically-integrated operators in the state. The company is listed on the Canadian Securities Exchange and plans to expand into a national brand. Chief Strategy Officer Jacques Habra, a vocal advocate for sun-growing, said about 70 percent of the company’s sun-grown product is packaged for flower sales and the remainder becomes prerolls and extracts.

“The price point is low in Oregon, but people like our product a lot so the demand is there,” said Habra. “Sun-grown is the lowestcost flower, so we use it for derivative product lines, too.”

The company operates two farms: Trails End in northern Jackson County and a newer farm in Manzanita Glen outside Grants Pass. Director of Outdoor Cultivation Seann Igoe said he likes to keep his crews lean and mean, so each farm has two dedicated farmers. Igoe floats back and forth between the farms. “I’m the leader but we are a team, so it’s similar to a kitchen where not one person is in charge of everything and we are all capable of doing most anything.”

Thus far, the farms and the brand appear to be on a good run. An Oregon lab recently confirmed Grown Rogue’s outdoor harvest included a strain testing at 35-percent THC, potentially breaking state records for outdoor cultivation. At the recent Grow Classic competition in Eugene, Oregon, Grown Rogue took first place in the Highest Percentage THC category, first place in Highest Percentage Terpenes, and third place in Growers Choice. Grown Rogue grows about thirty different strains and classifies them according to both name and the

experience consumers can expect.

“Consumers in Oregon and California appreciate the science behind the strain descriptions and really want to know what strain they’re enjoying,” Habra said. “As cannabis goes mainstream, people may care less about strain names, but some people will always care.”

Habra said the experience categories are a work in progress. The company collects information about physical and mental effects via customer surveys. The feedback will help other users understand the specific effects of different strains. He cited an example: “I was focused and balanced, but it also gave me a lot of energy.”

Grown Rogue recently established a microbusiness license that allows it to process and distribute products, and the company has been identifying and establishing strategic relationships with local farmers in the Humboldt region.

“There is a desire to know that the product came from an outdoor farm with the sun, earth, and land and pine trees and [other] things that influence the plant’s production,” said Habra. “There are some psychological differences when you know a plant is grown outdoors, with more terpenes and the sun

powering the plant. There’s always going to be a lot of people who want to smoke the sun and not electricity.”

In the Emerald Triangle, growers are developing standards for appellation of origin so consumers will be able to recognize strains coming from specific areas, much like the wine industry has turned Napa Valley and Sonoma into appellations known throughout the world.

Sun-grown cultivators face a big challenge—and opportunity—in the amount of education and marketing that will be required to reverse decades of bias favoring indoor flower. Many are accustomed to producing smaller crops due to terrain, regulations, and limitations set in place during the medical cannabis era. Justice Grown’s Brady said each small farm must produce at least 500 pounds in order to survive, a hefty increase from the 100 pounds necessary pre-adult-use legalization.

Two women who well understand the dynamics are Katie Jeane, founder of Emerald Spirit Botanicals, and Moon Made Farms’ Tina Gordon.

Katie Jeane has lived in Mendicino County for more than fifty years. Her farm resembles a traditional small farm, with a diverse array of vegetables, plants, and bushes intermixed with cannabis plots. Such “intercropping” or “companion planting” has been popular for decades, but in the newly regulated industry it’s becoming a rarity.

Gordon owns two forty-acre parcels in the southern Humboldt mountains and possesses county and state licenses allowing her to farm a half-acre of cannabis. She also maintains a small mixed-light greenhouse. Gordon estimated her yearly production at 500 to 1,000 pounds of flower and 1,000 pounds of biomass material.

As small- and medium-sized farms, Gordon’s and Katie Jeane’s operations allow little room for error. On the positive side, the women can maintain tight control and oversight of their staff and operations, and they can choose their strategic partners carefully. Both Moon Made Farms and Emerald Spirit Botanicals have another hedge in an extremely competitive market: a relationship with Flow Kana, one of the biggest champions of sustainable, sungrown cannabis.

Located on the eighty-acre former Fetzer Vineyards property in Redwood Valley, California, the Flow Cannabis Institute is building everything it needs to process, test, manufacture, and distribute flower and other products from more than 100 partner farms. Its first functional facility is dedicated to processing, sorting, and packaging flower.

“Flow Kana has solved a lot of the challenges and issues that small farmers have been facing and has magnetized a talented group of people who found partners to support sun-grown,” said Gordon.

Willie’s Reserve's partnership with Flow Kana recently benefitted Gordon when country music star Margo Price chose one of Moon Made Farms’ cultivars, Pineapple Wonder, to debut her new flower line under the Willie’s Reserve brand. Gordon also understands the importance of a strong retail connection and bought a small stake in the Vapor Room, a cannabis shop in San Francisco. There, as much as 80 percent of flower selection is dedicated to cannabis grown full season under full sun.

“It’s all about partnerships right now and community building and strengthening to promote sun-grown,” said Gordon. “It’s also going to be really important to ensure the consumer that they’re getting something organic and clean and cultivated with intention.” She quoted Japanese organic farmer and philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka: “The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.”

Katie Jeane and her two sons, Joseph and River Haggard, subscribe to Fukuoka’s notion of farming and have a unique perspective on breeding, cultivation, and nurturing their plants. She grows about a dozen different strains but said she has an archive of many different seeds passed down to her over the years. She takes a spiritual path in her breeding and plant selection, talking to and listening to her plants, and even seeking guidance from them.

“Thinking about [competitors] would be stressful, so it’s not something I think about,” she said. “I focus on listening to the plants and figuring out what they want to bring forward, and how can we support them to grow in a beautiful way.”

For the past few years, she has focused on developing more balanced 1:1 strains, to deliver a more harmonious effect. “I’ve been reviewing lab tests for the last five years, and it’s interesting to see what cannabinoid profiles come out and how long it takes to

stabilize them. That’s the really exciting stuff for me, where my passion is,” she said.

With a background in plant science, Joseph Haggard can discuss everything from homemade compost for heating the greenhouse to creating a holistic balance on the farm using companion plants and other natural solutions. He spends a good deal of time traveling to Emerald Spirit Botanicals’ retail partners to educate budtenders.

“I’m trained in biodynamic farming, so we incorporate some of those concepts. And the farm went through the Bronner family’s Sun and Earth Certification process,” he said. “When the cannabis is growing, we intercrop it with potatoes and onions and illicium, which is a habitat for beneficial insects. We work with various insects in our pest-management plan, so if anything damaging shows up then we have something to deal with it.”

Given the competition from large commercial operations cranking out thousands of pounds each harvest in massive indoor and greenhouse cultivation projects, craft farmers in the Emerald Triangle know they have little room for error moving forward.

“NorCal and Oregon grow the best outdoor cannabis in the world,” said Grown Rogue’s Habra. “But in California this is the beginning of price compression, so it will be interesting to see what happens to these highly-invested brands when the price plummets and surplus is the name of the game. It will be a major shift, just like in other states, so California is at the beginning of a cycle that will really rock the industry.”

What farmers of all stripes really are waiting for is federal legalization, so they can start shipping their creations to new markets across the country. Until then, it’s up to consumers to embrace sun-grown flower and the small farms that have cultivated plants outdoors for decades.

“It’s pretty challenging for small farmers to compete, but the market here in California is pretty sophisticated compared to other parts of U.S.,” Brady explained. “Folks in other parts of the country don’t have the heritage of boutique craft cultivators. So, if these farmers can hold on and develop their genetics and create some notoriety, they have a chance to succeed.”

The Redwood Roots family of farms brings artisan herb and culture to the world.

BY TOM HYMES

IF LIFELONG friendships, family values, fine artisan herb, and smart breeding are enough to fuel a revolution in small farming, Redwood Roots has all the elements it needs to succeed in a “green rush” atmosphere where everybody is betting against them except the people who know them best. Despite what you may have heard about the outlaw culture of California’s Emerald Triangle, and most notoriously the “Murder Mountain” area of southern Humboldt County, this is a tight-knit community of families whose shared experiences over many years have imbued them with a communal toughness they equate with the intertwining “tribal” root system of the redwood forests.

“There are several reasons why we chose the name Redwood Roots and why we thought it was so strong,” said Chris Anderson, who founded the collective in 2015. “‘Redwood trees is where we’re from’ is the obvious one, but the science behind redwood roots—how the forests interact with each other and literally hold each other up by communicating through the root system underneath, through the biology and life force underneath the soil—how they communicate is the Redwood Roots. We are the ancient trees as a community, and the roots of those trees are what is intertwined and helps support the Roots and hold us up. That’s the message behind us.”

Anderson frequently mentions the word “community” when he talks about the process of making Redwood Roots into a legal, functioning entity. The road to legalization has been particularly challenging for small farmers dealing with drastically falling prices and huge compliance costs for ever-

changing regulations. Everyone who decided to go legal has been living the challenges, including Anderson.

“In the cannabis industry they call business plans ‘sandcastle’ plans, because you build them around the law and then all of a sudden the law changes,” he said. “You go back and change your plans to conform to the new laws, and guess what? A new wave comes and knocks them over—only this time you build them differently, because you saw the waves coming from another direction.”

It’s just another day at the office when your history includes hiding from helicopters piloted by the U.S. military. “It’s what we’ve done our entire lives up here,” said Anderson. “Adapt, improvise, overcome, support each other, love each other, stick together. It’s in our DNA, second nature. We don’t even think about it. It’s a huge plus.”

Now, that huge plus is being calculated in terms of market penetration, marketing campaigns, licensing opportunities, and expansion strategies that include “retail, transport, distribution, delivery, and the operation of our own manufacturing facility,” according to Anderson. They may still do business on Humboldt Time, but no one at Redwood Roots is fooling around.

The story of Redwood Roots is the story of family, plain and simple. “Gregg Gratzel planted the seed in me,” said Anderson. “I really owe a lot to him for instilling in me the idea that this is happening, and maybe it would be a good way to support our people as well as create business for ourselves.” The two

men had known one another since childhood. “We were neighbors growing up,” Anderson said. “We’ve known one another that long.”

Long-term relationships are common among the Redwood family of farmers. “Another cultivator was my grandma’s neighbor in Redway,” Anderson said. “We’ve all played sports together, cried together and bled together as children, graduated high school together—not all in the same year, of course. The typical relationships of a small, rural community you find across America. In this one, there just happened to be a way to make money—and lots of it—by staying and not going away to school. Those relationships carried over into adulthood in a very intimate way.”

When Gratzel realized recreational legalization was on the horizon, he reached out to his boyhood buddy. “He had cerebrally started the process of getting his farm under compliance, what it would look like moving forward,” recalled Anderson. “He reached out to me knowing about my property in Benbow and the fact that it would make a fantastic facility and location for cannabis activity. I was in limbo about what to do with it, and he was like, ‘Hey, dude, what do you think about putting a dispensary in there?’ I said, ‘Wow, that’s a great idea.’ I hadn’t really thought about going in that direction.”

Out of such acorns grow mighty oaks, or in this case, redwoods. The Emerald Cup 2015 was only a few weeks away, and the two friends decided to drive down and check out the two-day event. “We ended up walking the show the first day for three or four hours without saying a word, our jaws-dropping, flabbergasted by the magnitude and volume of what was happening,” said Anderson.

“We didn’t stay the first night and talked the whole drive home about what a partnership would look like,” he continued. “Gregg even called his attorney that night, a Saturday, and got us an appointment the next week. We had no idea about the regulations that would come down or what the distribution model would look like. We just thought it was a great idea and decided to open a dispensary. That’s how it started in terms of planting the seed.”

In the end, limitations on allotted licenses forced the two to divide their efforts, with Anderson keeping Redwood Roots and Gratzel forming Humboldt Mountain, which today is called G Verde and is a member of the Redwood Roots family of farms. The collective model was a feature from the get-

go. “We went with a collective model from the beginning so we could utilize the patient base,” said Anderson. “The thought was, ‘Let’s use the laws to protect our people while we work together to cut costs.’ That transitioned quickly into pushing distribution services.

2015 was a year of beta-testing at events. “We got really good feedback,” said Anderson. “The brand and mark were strong, and our story was one of a kind. It was obvious we were doing the right thing and heading down the right road. At that time, our intention was to bring on maybe twentyfive farms, because we knew we weren’t going to be able to service more than that. Our theme then and now is that we will not overpromise and under-perform.”

As expected, the collective grew organically. “We didn’t make the launch of Redwood Roots public or do any radio spots,” said Anderson. “It was basically word of mouth, talking among friends about what Redwood Roots could do for them in terms of protection and the law, coming out of the shadows into the light. ‘Here we are in the

light,’ we told them. ‘Come and join us. We’d like you to come.’ It was slow, organic growth among people intrigued not just about Redwood Roots, but the process of going legal and what that would look like working as a group. The idea was, ‘If these guys are doing it, we can do it, too.’ The conversation literally spread from neighbor to neighbor: ‘Maybe you should go have a conversation with Chris.’”

Redwood Roots encompassed forty-four farms at one point, with most of the workload split between Anderson and Holly Carter, his righthand person at the time. “We were doing all the work, and it just got to be too much,” he said. “The quality of service went down. I had a cultivation site and a nursery, and I was spread too thin.” By the end of 2016, Redwood Roots had downsized to a couple dozen farms.

February 14, 2019, marked a very special occasion for the Redwood Roots team, which, in addition to the farmers and farms that

Redwood Roots' Family of Farms

Clearwater Farms

Cut Creek

Formidable Flower

G Verde

Galen Farm

Hidden Prairie

High Tree

Humboldt Cure

Humboldt Generations

Humboldt Infuzions

Humboldt Redwood Healing

King Range

Lady Sativa

Mattole Valley Sungrown Riverview Gardens

Savage Farms

Sohum Royal

Twin Creeks

Uplift Coop

Westside Heritage

make up the collective, is composed of new and longstanding helpers working to create a vision of small-farm self-determination and independence that everyone on the team passionately shares. The first order of business for Anderson was to celebrate survival. “First, [we wanted] to take some time to celebrate the fact that we’ve persevered through tough times of prices falling out from underneath us, spending all our money on lawyers and consultants from engineering companies and whatnot, and we now have licenses from the state of California to sell cannabis to the people. And that is a big reason to celebrate,” said Anderson. “We have persevered as small farmers, and as people we have persevered together, and we now can follow through on this whole idea of being a distributor for all of these wonderful families that started all of this. The celebration is simple in that we made it this far and we’re still here, and now we get to go do what we do.”

February 14 also marked the official start of RR distribution, as well as other limited services. “The Benbow dispensary should

the community, because it is not limited to farms,” said Anderson. “Anyone in the community can join and cut costs, even if it’s for one vehicle a year. If you save 30 percent, you’ve just saved a whole lot of money. It’s an across-the-board entity that can drive the cost of living down.”

For Anderson, the GPO is one of the ways his community can overcome challenges facing the artisan farmer. “These are fluffy things that can help us overcome challenges as we move forward, but I truly believe in staying true to our values, being authentic, being who we truly are as a community. They’re not just words produced by a marketing firm. What’s going to sell is our story and the people, the human beings behind the herb that’s being cultivated. It’s being cultivated by family hands getting dirty in the earth, getting up at 5:30 a.m. and not going to bed until 10 p.m., because they’re out literally with their children on their backs farming this ganja for you.

“Maybe I’m a dreamer,” he added, “but I truly feel that what we are and who we are is so marketable right now. Health and wellness are very hot across the country and the world right now—yoga, Pilates, wholefoods shopping, farm-to-table restaurants are everywhere in Southern California.

Millennials want to know where their products come from, and that the companies they support are community-oriented; that they’re giving back. We don’t even have to try to do that, because that’s just who we are. I feel like having those things inside of us puts us a step ahead from what the big companies are trying to market themselves as. We support the small farmers of Northern California, and we only use organic fertilizer.”

Genetics also will play a key role in the success of Redwood Roots going forward.

“The original seed smugglers came to Humboldt [County],” said Anderson. “This is where all the genetics came into this country, and about half the farms we’re working with now have genetics projects going on. These are people who have been working on genetics for years, some for decades. They have some consistent, strong seed stock that they’ve developed over time and continue to develop. I absolutely think genetics are one of the important factors moving forward for Redwood Roots—or anybody, really.”

With many farms to work with, Redwood Roots has enviable options, genetically speaking. “We’ll have five to seven strains we always carry that will be the standard strains we know will sell, that everybody likes,” he said. “But then there will be more

than a hundred varietals we can choose from, including designer strains from Los Angeles that get up here that we can tweak and make our own. Most of those strains originally came from somewhere up here anyway.”

Regarding the question of when to release new strains, Anderson said timing is everything. “There’s no reason to hoard genetics anymore, because it’s not going to do you any good in the market,” he cautioned. “You’ve got to create a demand for it, and to do that there has to be a certain amount of it or you have to win an award. Genetics and the issue of when to release and what farmers are doing about it is super fascinating to me.”

Anderson’s parents and grandparents operated restaurants and gift shops in the area. He was raised in the service industry, not on a farm, giving him a unique perspective about the industry. “I understand the tourism economy from a different perspective than some other folks in the area,” he said. “I have seen redwood tourism fall off over the past few years, and I haven’t seen a big push from the chamber of commerce or the bed-tax people [to fix it]. It’s time to resurrect redwood tourism as a combination of canna, redwood, outdoors, fishing, hiking, surfing. We need to market it as a destination location for experiences that are beyond cannabis and beyond the redwoods.

“Tourism is a monster part of this community surviving and moving forward, because it’s so much more than selling a product to the consumer down the road,” he added. “That doesn’t do any good for the businesses in town, and this is a community. We’re all in this together. It’s a package deal.” Anderson doesn’t intend to build it and wait for them to come, however. He wants to hand-deliver his community to the world. “We’re going to take the Redwood Roots[Southern Humboldt] circus on the road, and we want to bring everybody with us,” he said.

“The musicians of Humboldt are coming to do the music; the chefs are coming to make the food. We’re bringing everything else— the food, the massage therapists, the yoga practitioners, the speakers about regenerative farming practices, the farmers and their products, and we’re taking it all on the road. It’s a huge part of expressing who we are and getting that face time with the consumer.”

ORIGINALLY FROM Rhode Island, Kevin Jodrey spent years as a selfprofessed outlaw grower in California before going legal. In 2008, he joined a dispensary called the Humboldt Patient Resource Center (HPRC), where he helped isolate CBD genetics from a Spain-bred strain called Cannatonic. Since then, he’s become one of the most respected cannabis breeders in the industry.

“Around 2009, Jamie of Resin Seeds came to Humboldt [County, California] with the original Cannatonic line,” Jodrey told Leafly in January. “He provided it to Dr. William Courtney, who reached out to a grower named Dready Aaron. They brought the stock to me over at HPRC because they needed a place to legally hold it and sift it for unique [phenotypes]. At the time, I was cultivation director of the resource center and I agreed to allow them to conduct their research in the facility. Together, we started locating the outlier cultivars.”

In 2012, Jodrey purchased the Grass nursery in Garberville, California, which he renamed Wonderland Nursery. A year later, he and the team began an effort called “Free CBD for the People.”

“Financed by THC-dominant clone sales at Wonderland Nursery, between 2013 to 2017 we gave away upwards of 150,000 CBD clones,” he told Leafly. “Additionally, we provided information to patients on how to cultivate strains while allowing them to access

laboratory testing for free. This allowed patients to start their own breeding projects. It was important to build seed lines, because to a lot of the patients, clones took too much energy to keep alive.”

A natural and effusive communicator, Jodrey has produced a series of educational videos about breeding—a service he does without charge, reflecting his willingness to help craft farmers find a conceivable, if unlikely, path to long-term survival.

In Jodrey’s view, the area best-suited for cultivation is Humboldt County’s timber production zone. “Because you’re above the fog and you have beautiful airflow,” he told mg, adding good water sources and sun penetration make the area even more suitable for cannabis. “These higher-altitude spaces have a lot more wind blowing [through] them than you do in a canyon, and you’re above the fog level, so you have a lot less pathogenic pressure on the plant.

“I have a half-acre that’s permitted, and I could have gone up to a full acre if I had moved [down the mountain, as the county wanted],” he continued. “But as a cannabis cultivator, even though I think the alluvial flood plains of the Eel River are great for dry-land farming, they also limit your cycle because at the end of the season you have incredible amounts of mold and fungus pressure. To me,

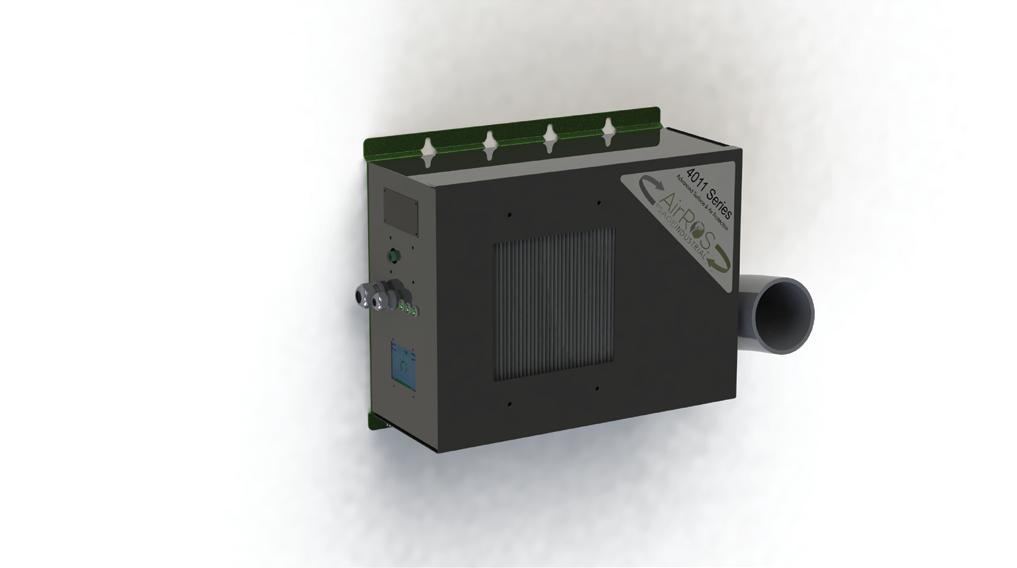

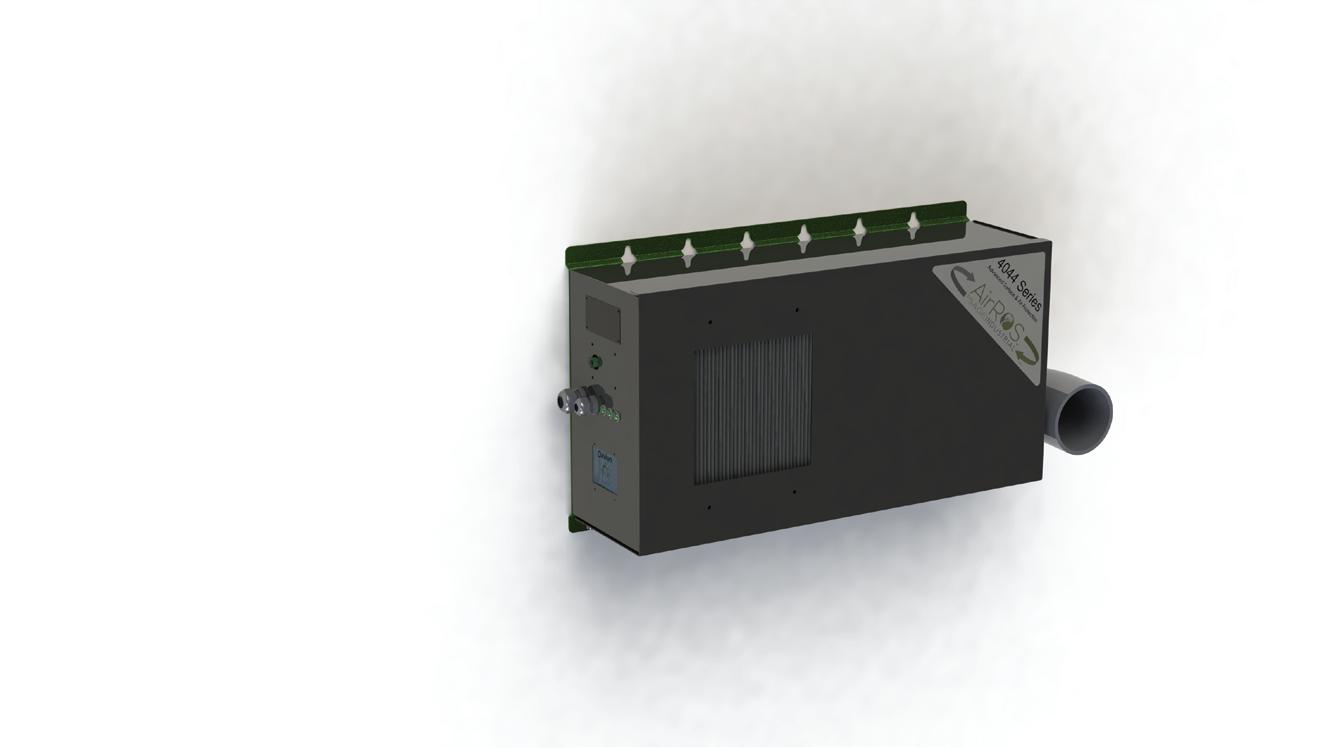

•Provides

•Reduces

•Destroys

•Reduces

•Greenhouses

•Indoor Growing Rooms

•Indoor Flowering Rooms

•Mothering Rooms

•Drying Rooms