Design Big Ideas

This isn't Wood. This is Fortina. ™

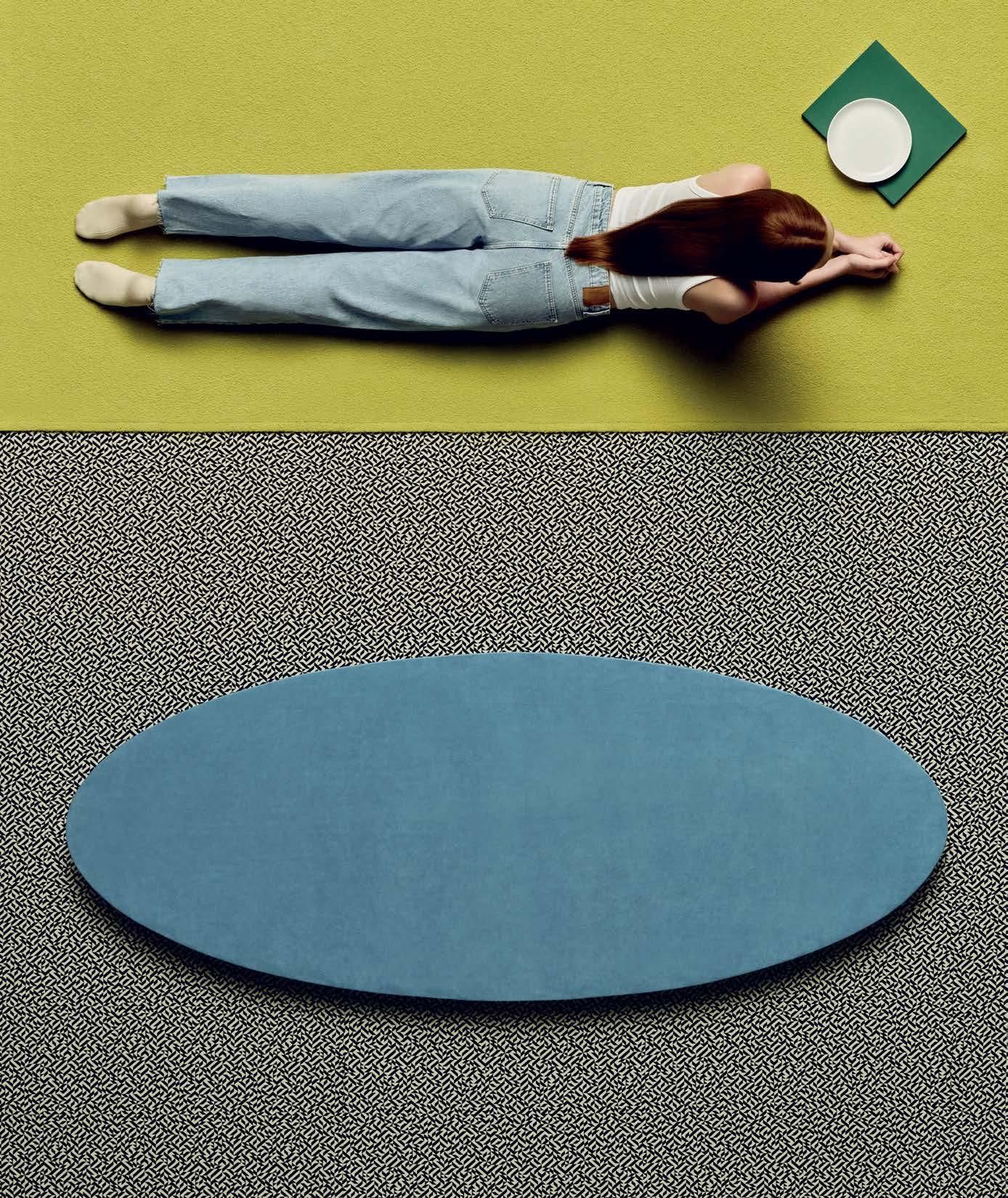

Suchi Reddy’s me + you

BEAUTIFUL INTERIORS START WITH THE FLOOR

BIG IDEA 06: NEW CIVICSCAPES 80 The Architects Shaping

Weiss/Manfredi’s Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park in Queens

BIG IDEA 05: CARING HOMES 72 Where Housing Meets Humanity

Weve

Meet now, nest later.

Lightweight and flexible, Weve offers thoughtful comfort and effortless nesting. Smart, sleek and always ready for what’s next.

Designed by EOOS. Made by Keilhauer.

ON

Left: Makan, a restaurant in Mexico City designed by Locus. Photo by Rafael Gamo; Right: Growing Matter(s), designed by Henning Larsen in collaboration with Politecnico di Milano, at Milan Design Week 2025.

Photo by DSL Studio

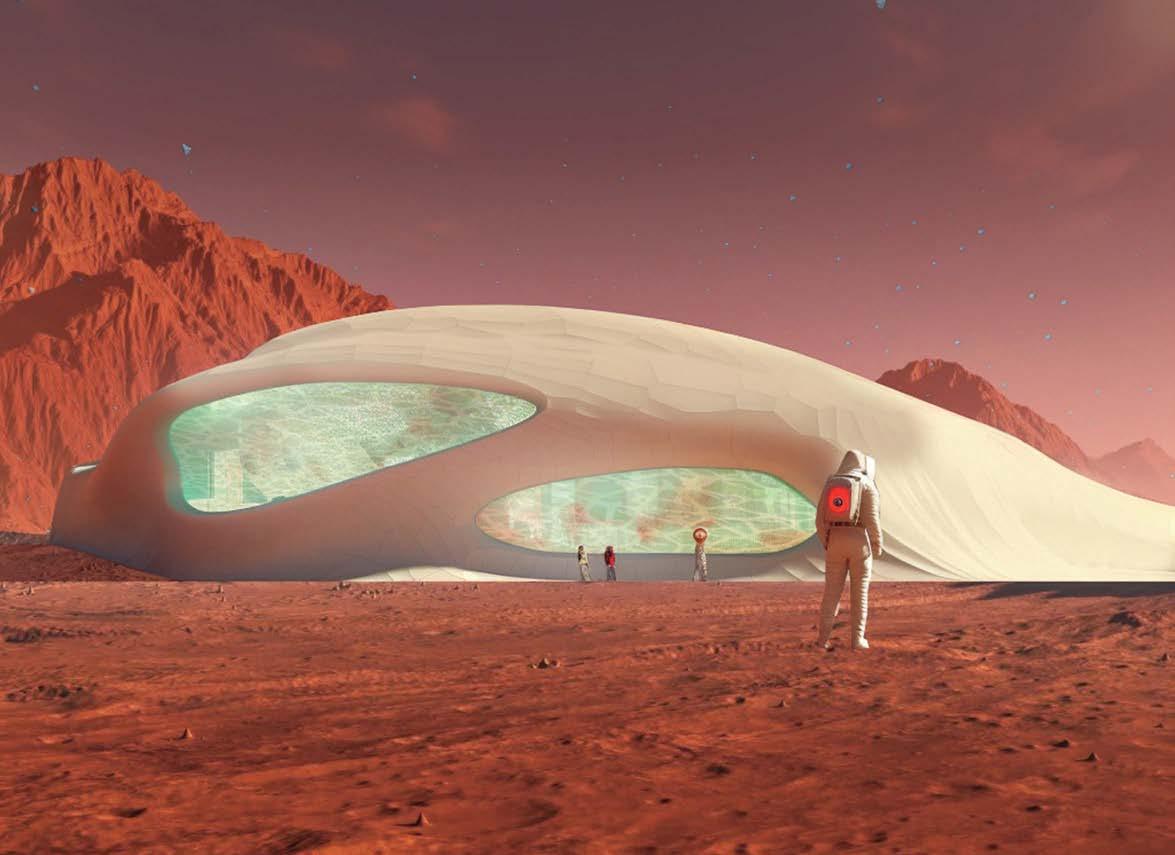

Anthony Acciavatti’s Grounded Growth: Groundwater’s Blueprint for Intelligent Urban Form at the 2025 Venice Biennale

Grounded In Space

From 9x36 planks to 24x24 and 18x36 tiles, Grounded Spaces gives you the freedom to design with scale, rhythm, and flow. Whether you’re layering textures or defining zones, this collection adapts to your vision—offering a spectrum of sizes and colorways to ground every space.

EXPLORE

EDITORIAL

EDITOR IN CHIEF Avinash Rajagopal

DESIGN DIRECTOR Tr avis M. Ward

SENIOR EDITOR AND PROJECT MANAGER Laur en Volker

SENIOR EDITOR AND ENGAGEMENT MANAGER Fr ancisco Brown

ASSOCIATE EDITOR AND RESEARCHER J axson Stone

DESIGNER Rober t Pracek

PROGRAMS COORDINATOR AND ASSISTANT EDITOR Dinky A srani

COPY EDITOR Don Armstr ong FACT-CHECKER Anna Zappia

EDITORS AT LARGE Ver da Alexander, Sam Lubell

PUBLISHING

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Tamara Stout tstout@sando wdesign.com 917.449 .2845

NATIONAL SALES DIRECTOR Ra chel Pettit

ACCOUNT MANAGERS

Julie Arkin jarkin@sandow design.com 917.837.1344

Meredith Barberich meredith.barberich@sando wdesign.com

Gregory Kammerer gkammer er@sandowdesign.com 646.824.4609

Laury Kissane lkissane@sando wdesign.com 770.791.1976

Julie McCarthy jmccarth y@sandowdesign.com 847-567-7545

Colin Villone colin.villone@sando wdesign.com 917.216 .3690

PRINT OPERATIONS MANAGER Olivia Padilla

MARKETING & EVENTS

DIRECTOR, PROGRAMS & PARTNERSHIPS

Kelly Allen kkriwko@sando wdesign.com

DIRECTOR, CLIENT STRATEGY Kasey Campbell

SENIOR DIRECTOR, MARKETING OPERATIONS Ra chel Senatore

DIRECTOR, CREATIVE SERVICES Carly Colonnese

GR APHIC DESIGNER, CREATIVE SERVICES Paige Miller

METROPOLISMAG.COM @metr opolismag

A MORE SUSTAINABLE METROPOLIS

As part of the SANDOW carbon impact initiative, all publications, including METROPOLIS, are now printed using soy-based inks, which are biobased and derived from renewable sources. This continues SANDOW’s ongoing efforts to address the environmental impact of its operations and media platforms. In addition, through a partnership with Keilhauer, all estimated carbon emissions for the printing and distribution of every print copy of METROPOLIS are offset with verified carbon credits.

SANDOW DESIGN GROUP

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Erica Holborn

CHIEF MARKETING & REVENUE OFFICER Bobby Bonett

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER Michael Shavalier

CHIEF DESIGN OFFICER Cindy Allen

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT AND DESIGN FUTURIST AJ Paron

VICE PRESIDENT, DIGITAL Caroline Davis

VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Laura Steele

VICE PRESIDENT, FINANCE Jake Galvin

SENIOR DIRECTOR, VIDEO Steven Wilsey

SANDOW

CHAIRMAN Adam I. Sandow

CONTROLLER Emily Kaitz

VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES Lisa Silver Faber

DIRECTOR, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Joshua Grunstra

METROPOLIS is a publication of SANDOW 3651 FAU Blvd. Boca Raton, FL 33431

info@metropolismag.com 917.934.2800

FOR SUBSCRIPTIONS OR SERVICE

800.344.3046

customerservice@metropolismagazine.net

SANDOW was founded by visionary entrepreneur Adam I. Sandow in 2003, with the goal of reinventing the traditional publishing model. Today, SANDOW powers the design, materials, and luxury industries through innovative content, tools, and integrated solutions. Its diverse portfolio of assets includes LUXE INTERIORS + DESIGN, INTERIOR DESIGN, METROPOLIS, and DESIGNTV by SANDOW; ThinkLab, a research and strategy firm; and content services brands, including The Agency by SANDOW, a full-scale digital marketing agency, The Studio by SANDOW, a video production studio, and SURROUND, a podcast network and production studio. SANDOW is a key supporter and strategic partner to NYCxDESIGN, a not-for-profit organization committed to empowering and promoting the city’s diverse creative community. In 2019, Adam Sandow launched Material Bank, the world’s largest marketplace for searching, sampling, and specifying architecture, design, and construction materials.

THIS MAGAZINE IS RECYCLABLE.

Please recycle when you’re done with it. We’re all in this together.

REVOLUTIONARY TWISTS AND TURNS

Experience next-level airflow with the Venn 58” ceiling fan—where cutting-edge design meets powerful performance. Engineered with an energy-saving 6-speed reversible DC motor, this fan delivers comfort through every season. A pre-paired handheld remote puts control at your fingertips, and an optional light kit (sold separately) offers added functionality. With the Venn fan, comfort takes a stylish, revolutionary turn. Find Venn and other amazing fans at craftmade.com

Suchi Reddy, FAIA, is a pioneering architect and designer whose practice centers on neuroaesthetics— the study of how design impacts the brain and body. As founder of Reddymade, she merges research and intuition to create spaces that enhance well-being, from civic and residential architecture to immersive public art. Guided by her mantra “Form follows feeling,” Reddy has completed key projects, including Google’s flagship NYC retail store; a Salt Point, New York, home designed with artist Ai Weiwei; and a hospital room prototype for children with disorders of consciousness, incorporating a spatial prescription to aid recovery. She is a leading voice in designing for neurodiversity and teaches at Columbia GSAPP. Born and raised in India, she is now based in New York City. In this issue, Reddy reflects on how neuroaesthetics has shaped her practice and argues for a future of architecture grounded in feeling, empathy, and well-being (p. 40).

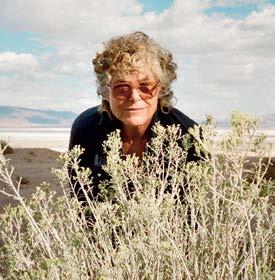

Timothy A. Schuler is an award-winning journalist and design critic whose work focuses on the intersection of the built and natural environments. He is an editor at Landscape Architecture Magazine and served as Places Journal’s critic-in-residence in landscape architecture from 2024 to 2025. His Places essay “The Middle of Everywhere” was included in The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2020 He lives in Manhattan, Kansas. In “Designers Rethinking Our Relationship with Water” (p. 106), Schuler highlights projects that are making hidden water systems visible and advocating for more civic, ecological, and equitable engagement with this essential resource.

For 25 years, Stephen Zacks has been dedicated to advocacy journalism, architecture criticism, book editing, urbanism, project organizing—and, lately, improving his tennis technique. He graduated from Michigan State University and The New School for Social Research with a bachelor’s in interdisciplinary humanities and a master’s in liberal studies. Zacks works as an independent architecture book editor for Actar, Axiomatic Editions, Cahiers d’Art, Goff Books, and Lars Müller Publishers and writes regularly for Abitare, L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, the Architect’s Newspaper, Dwell, Landscape Architecture Magazine, METROPOLIS, and Oculus He recently relocated from New York City to Mexico City. For this issue, Zacks profiled Locus Architects (p. 96), whose climate-reparative work in Mexico City offers a powerful model for ecological and social resilience.

STEPHEN ZACKS

SUCHI REDDY

TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

Big Ideas in Architecture and Design

A PROFESSOR OF MINE in design school liked to say, somewhat pompously: “The domain of design is the entirety of human knowledge.” What he meant was that, unlike certain other professionals (looking at you, neurosurgeons, quantum physicists, and yoga instructors), designers aren’t required to be deep experts in a defined set of topics. Instead, we are generalists because we design for all the situations of life. The corollary to that is that the ideas for great design can come from absolutely anywhere.

Take neuroaesthetics, a field of research first defined in the early 2000s that studies how our brains process and experience art. In this issue, we invited architect Suchi Reddy, who has been testing ideas drawn from this field in a series of installations and projects going back nearly a decade, to tell us what she has learned from her explorations. You can read her vigorous call for spaces informed by feeling (“An Architecture of Sensation”) on p. 40, and then see how neuroscientific research has made its way into product development for architecture and interiors (“5 Smart Designs that Boost Brain Function,” p. 46).

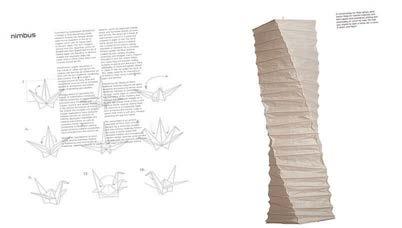

New materials often spur fresh design paradigms, but none is perhaps as farfetched or intriguing as mycelium—the fibrous, rootlike, often-invisible structure of fungi. In “The Future Is… Fungi?” (p. 114) associate editor Jaxson Stone picks their way through a now enormous body of installations, explorations, proposals, and products made of mycelium to see how practical or proximate are the claims that we could be building our homes from the material or letting fungi eat our plastic waste.

Eye-opening research or surprising materials make for great design prompts, yes,

but new concepts in architecture also emerge gradually from a body of work. To mark New York City’s four hundredth anniversary, senior editor Francisco Brown spoke to three local architecture firms that have helped evolve what we think is a significant but underappreciated export from the city—a new type of civicscape (“The Architects Shaping NYC’s Public Space,” p. 80) most easily exemplified by the High Line. Thanks to innovators like Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Marvel, and Weiss/Manfredi, New York is fine-tuning a unique formula that combines public space, infrastructure, cultural arena, and development engine. “We’re questioning the norms of how we treat the city and

where we draw the line between public and private,” says Elizabeth Diller.

Other ideas in this issue include AI helpers, all-rounder affordable housing, stage-setting in hospitality, localized sustainability, groundwater as a design framework, artful lighting, and a provocation from Charlotte Malterre-Barthes to halt all new construction—even if only as a thought experiment—so we can take stock of the other, less extractive possibilities that architecture could explore.

There’s much to ponder in the pages ahead, and we hope you find something that inspires you!

—Avinash Rajagopal, editor in chief

Mycelium, a byproduct of mushroom cultivation, is capturing the imagination of architects, designers, and product manufacturers worldwide. Read more in "The Future is... Fungi?" on p. 114.

kimballinternational.com

Sustainability News Updates for Q4 2025

A year of policy ups and downs in the United States has created a fragmented regulatory landscape for the building industry to navigate.

By Avinash Rajagopal

Over the course of this year, federal priorities in the United States have shaken up both new sustainability-focused initiatives launched under the last administration as well as longer-term cornerstones established under administrations before that. Meanwhile, most state-level policies have stayed in place or moved forward. The result is a mixed bag for building industry professionals when it comes to driving efficiency, minimizing risk, and advancing sustainability and well-being in their projects. Here are a few examples that show the current state of flux in this country:

PFAS Pullback

In 2019, the EPA announced an action plan to address the complex issue of cancer-causing “forever chemicals,” also known as PFAS, in drinking water. Since PFAS chemicals are widely used in building products, the A&D industry can play an important role in their elimination. In fact, many manufacturers have eliminated them in anticipation of upcoming restrictions: Designtex, for example, announced

last October that it was a totally PFAS-free company. However, this May, the EPA announced that it will delay enforcement on more stringent limits for two PFAS chemicals in drinking water and will reconsider the limits on four other forever chemicals, lifting regulatory pressure on industry. Public awareness and pressure from motivated manufacturers and specifiers will now have to hold the line.

PV Sunset

Homeowners who install solar energy have been able to claim tax credits since 2005, when President George W. Bush revived an older program that had been allowed to lapse. But that 20-year subsidy ends at the end of this year. Meanwhile, the EPA has canceled its $7 billion Solar for All program, pulling back $156 million from low-income communities in Michigan and $130 million from Indiana, among other states. Solar power is a cornerstone of the Net Zero movement, which will now have to rely on local incentives or other means to finance our energy transition.

Recycled. Refined. Remarkable.

For over 75 years, Bolon has been a pioneer in sustainability, producing woven flooring with a past anda future.

New York Concrete

Under the state’s Buy Clean Concrete Guidelines, New York’s Low Embodied Carbon Concrete program went live early this year. The codes now mandate a maximum global warming potential (GWP), i.e. a maximum amount of embodied carbon emissions for concrete used in building and transportation projects in New York. With some exceptions for high-strength or quick-curing concrete, concrete mixes used in state projects must have an EPD that shows compliance with the GWP limits.

California Clean

At the start of this year, the Buy Clean California Act took effect, setting GWP limits on structural steel, concrete reinforcing steel, flat glass, and insulation. All public works by state agencies and schools in the University of California and California State University systems will be affected by this policy.

Stellar Support

Alarmed by news reports that the EPA planned to cut funding for its successful Energy Star program, which saves Americans an estimated $40 billion in energy costs each year, a group of 1,000 organizations has banded together in support of the program, including built environment bodies USGBC and the National Association of Home Builders. The fate of the program still hangs in the balance, but the overwhelming bipartisan vote of confidence from industry is an encouraging sign.

Crafted Close to Home, Designed for Impact

A table from Room & Board tells a quiet story of resilience, place, and purpose—one rooted in the company’s hometown of Minneapolis and the city’s changing canopy.

The Orlin, available as both a dining and coffee table, is made from wood reclaimed from urban ash trees, many of which were lost to a local pest, the emerald ash borer. First detected in Minneapolis’s Prospect Park—along Orlin Avenue, the table’s namesake—the ash borer has devastated more than 867 million trees across Minnesota, dramatically altering the state’s tree cover. To prevent these felled trees from becoming mulch or landfill waste, Room & Board set out to transform them into something lasting.

That effort stays close to home. Through a partnership with Minneapolis-based Wood From the Hood—which reclaims trees lost to storms, disease, or construction—the wood is milled, dried, and finished just miles from where it's sourced. From there, it’s crafted into sustainable furniture by longtime local partner Siewert Cabinet & Fixture Manufacturing in South Minneapolis. The newest addition to the collection, an oak finish, follows a similar path—made from reclaimed wood from Minneapolis-based Storm Trees and manufactured by American Woods in North Dakota.

Crafted with care, the Orlin table carries the imprint of its origins—visible in knots, grain patterns, and subtle imperfections that connect it to the landscape. Its form nods to Minneapolis’s Scandinavian heritage with clean lines, simple joinery, and purposeful proportions. Clear or charcoal finishes let the natural character of the wood take center stage.

Orlin is part of Room & Board’s broader commitment to sustainability and urban wood reuse. The company’s partnership with Wood From the Hood is a local expression of its larger

Urban Wood Project, launched in 2018 with the USDA Forest Service and the social impact organization Humanim. The initiative began by reclaiming lumber from Baltimore row homes, while also creating jobs for people facing barriers to employment. It has since grown into a national network. Today, cities like Detroit, Sacramento, New York, and Minneapolis contribute to a supply chain that rescues wood from demolition and disease, repurposing it into durable furniture.

This approach not only reduces waste—it also helps store carbon. According to the Sacramento Tree Foundation, another Room & Board partner, the wood in 100 coffee tables can retain over 13 metric tons of carbon dioxide, the equivalent of removing nearly three cars from the road for a year. Through

View Room & Board’s 2024 Impact Report here.

the Urban Wood Project, Room & Board already diverted more than 400 trees from the waste stream in 2024, with a goal of reaching 1,000 by the end of 2025.

“We continue to learn how to maximize the reclaimed wood we use,” says Jenon Bailie, merchandising and design director for Room & Board. “Our goal is greater efficiency and developing reliable sources so we can incorporate more reclaimed wood into our collections.”

Room & Board’s values—craftmanship, sustainability, and community—are reflected in every phase of Orlin’s journey, from tree to table. It’s a piece that invites people to gather around something made with care and reminds us that the future of furniture isn’t just about design. It’s about meaningful, measurable impact.

BIG IDEA 01: AI-CHITECTURE

How to Embrace AI in Your Workflow

By Dinky Asrani

AS INNOVATION IN AI TOOLS ADVANCES rapidly, we see its influence across the built environment in both predictable and unexpected ways. It has the potential to create fundamental changes in the way buildings are made, operated, and how they connect to and impact wider systems.

Designers bring the soul and the human touch, while AI brings the speed. Explore how these tools can collaborate with architects, designers, and product manufacturers, reshaping the means by which they approach everything from code compliance to conceptual visualization, accelerating decision-making, and aligning teams to create a more efficient built environment.

PATHWAYS

Material manufacturers face mounting pressure to provide environmental performance data. Still, the information that exists is scattered across PDFs from different vendors, utility bills with varying units of measure, and disparate procurement systems.

Pathways tackles this data challenge head-on, using AI to process large volumes of unstructured information and convert it into comprehensive life-cycle assessments. The platform transforms vendor documentation, ERP systems (Enterprise Resource Planning), and utility data into third-party certified EPDs (Environmental Product Declarations) while delivering crucial insights into production efficiency and environmental performance benchmarks. “EPD is the bare minimum,” explains Jack Cove, head of go-to-market at Pathways. The company’s vision extends beyond compliance to help manufacturers identify improvement opportunities and build sustainable products. pathwaysai.co

FINCH

Finch’s AI-powered generative design platform optimizes 3D building design by providing immediate performance feedback.

Finch transforms the early stages of architectural design by generating optimized yet customizable floor plans from building masses while considering real-world constraints like structural systems, MEP requirements, and local codes. The platform seamlessly integrates with Revit, Rhino, and Grasshopper, positioning itself as “Figma for architects.” By blending AI with human creativity, Finch enables exploration of design options, makes data-driven decisions, and streamlines architects’ workflows.

The tool’s approach democratizes parametric design, making advanced computational tools accessible to firms without specialized programming expertise while maintaining the designer’s creative control throughout the iterative process.

finch3d.com

Featured: Portland Cliff™ Porcelain Tile

Gemini Porcelain Panels by Laminam®

UPCODES

Rather than manually parsing through thousands of code sections, the AI-powered platform UpCodes delivers tailored responses to specific compliance queries, catching requirements that might otherwise be missed.

It revolutionizes building code research by transforming dense regulatory text into instantly searchable, contextually relevant guidance. With over 800,000 AEC professionals using the platform, architects have reported saving many hours monthly through its iterative feedback capabilities. The platform’s Copilot feature helps professionals unpack and interpret building codes by sourcing from a curated library of adopted regulations rather than generic LLM-based tools or web content. While AI provides analysis and interpretation support, it enhances rather than replaces professional judgment— trained professionals still add their essential layer of understanding to ensure proper code compliance. up.codes

BIMBEATS

Bimbeats functions as a fitness tracker for architecture firms, silently monitoring software usage, model health, and team productivity to reveal hidden patterns in design workflows. The platform captures detailed activity data across all AEC software, feeding it into analytics engines that visualize and identify bottlenecks, predict system crashes, and guide resource allocation decisions.

While Bimbeats doesn’t automate design tasks directly, it analyzes data to provide intelligence that enables firms to identify automation opportunities and optimize their existing processes. This shift from reactive troubleshooting to predictive workflow management fundamentally changes how design teams understand and improve operational efficiency, enabling cross-team insights that will enhance collaboration between BIM managers, project leaders, IT teams, and developers. bimbeats.com

VERAS

Veras bridges the gap between conceptual sketches and photorealistic renderings, generating quick and compelling visualizations directly within established design software like Revit, Rhino, and SketchUp. Built specifically for AEC workflows, this platform understands architectural constraints and material properties that traditional AI tools miss. Designed for early-stage design ideation and exploration, Veras serves architects, interior designers, urban planners, and real estate developers seeking to rapidly visualize concepts and communicate design intent.

photorealistic AI-generated

The integration with Enscape allows Veras to work with actual 3D models and camera views, producing context-aware visuals grounded in real project data rather than abstract prompts. This capability transforms design communication, enabling architects to generate multiple visualization options quickly for client presentations and design development, all while maintaining technical accuracy and design intent. evolvelab.io/veras

POLYCAM

Polycam is streamlining AEC workflows by combining LiDAR and photogrammetry into a simple video recording process and transforming spatial documentation. The platform can generate 3D models and 2D floor plans from a single capture session—aligned and ready for project integration with software like AutoCAD, Revit, Rhino, and SketchUp.

The tool enables architects and interior designers to quickly document existing conditions, measure spaces, and create as-built models without the need for specialized equipment, excelling in early-stage site analysis. poly.cam

A

visualization of an A-frame house, created using descriptive prompts to guide style, materials, and environmental settings for architectural inspiration on Veras.

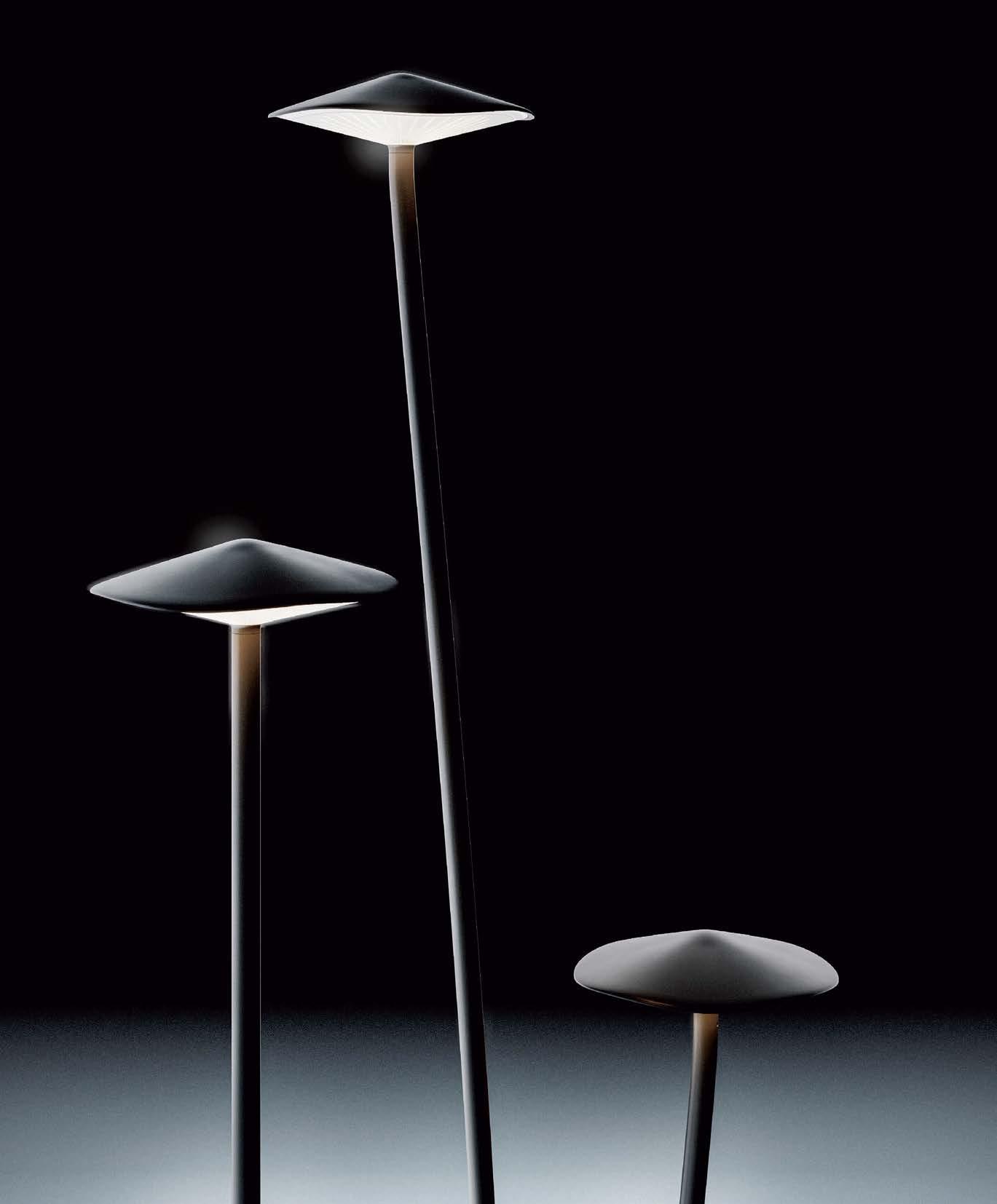

Lighting That Lets Shape Shine

From sculptural forms that blend art and illumination to fixtures inspired by nature’s quiet beauty to sleek lines that guide the eye— these three lighting trends reimagine how we shape space, mood, and meaning with light.

By Murrye Bernard

Balancing Act

Form and function fuse together, perfectly complementing one another, in this year’s plethora of sculptural, asymmetric offerings. Seemingly defying gravity, these fixtures bring a creative focal point to a variety of interiors. Sometimes lighting is meant to be concealed, but these four options will undoubtedly take center stage.

Introducing a fresh new collection of contract fabrics by Anna Elisabeth and Crypton—where elevated design meets trusted performance. Crafted for contract spaces, these textiles offer stain, spill and odor resistance without compromising softness, beauty or style.

Shop the collection at

02 A-N-D: TIER

Designed by Lukas Peet, this linear pendant fixture is made entirely of extruded aluminum. It features a scalloped profile that allows light to reflect and disperse evenly. Tier is formatted as a single pendant or can be segmented in multiples, as well as stacked horizontally or vertically, mimicking a tessellated pattern. The fixtures comprise a reflector and an underlying LED housed opposite in suspension, concealing the direct light source. a-n-d.com

03 STACKABL X ROCKWELL GROUP: TILT + SHIFT

A five-piece series comprising the biodegradable materials cork and felt, Tilt + Shift includes two intentionally off-kilter table lamps and three floor lamps with tops offset from the bases. The playful collection is both tactile and visually disarming— LED discs are encased in precision-cut wool felt discs mounted atop sculptural cork bases. The touch-dimmable lamps are built to order in multiple colorways and range from 6 to 46 inches in height. stackabl.shop

04 ANONY: HIGHWIRE. TRIO CHANDELIER

Inspired by the natural forces of gravity, this chandelier features cables that create tension between multiple points with weighted centers—the luminaires. Combining multiple pendants, the chandelier takes on a three-dimensional form that frames views within interior environments. Available in either anodized matte black or brushed aluminum finishes, the pendants measure eight inches in diameter and are made of aluminum, polycarbonate, and plexiglass. anony.ca

Designed from eelgrass collected off the coast of Denmark, Søuld Wall is a sustainable panel that highlights a rapidly renewable, carbon-storing material while offering exceptional sound-absorbing qualities. spinneybeck.com

Earth Forms

Biophilia is about more than just bringing greenery indoors: This fresh crop of fixtures draws inspiration from natural elements to create an earthy, calming vibe. Whether evoking the organic shapes of fruit or mushrooms or more rugged specimens such as stones and boulders, these light fixtures instantly become both a focal point and a conversation piece.

These outdoor light fixtures mimic the look of elegant, long-stemmed mushrooms. The lamps are designed to be staked directly into the soil to cast a gentle pool of light. Available in earthy hues ranging from brown to black and dark green, the fixtures comprise replaceable, modular components to extend their lifespan—a sustainable detail that hearkens back to their natural origins. lodes.com

05 LODES: KINNO BY PATRICK NORGUET

Drop It

Like It’s Hot

Drops and other mini disasters are a now a piece of cake. Armstrong Flooring® TimberTones® stands up to a range of daily demands within hard-working commercial spaces. Our revolutionary process uses heat and pressure, not acrylic fillers, to create an ultra-dense 100% natural, highly sustainable, hardwood floor that’s ideal for restaurants, hotels, retail spaces and more.

06 JUSTIN BAILEY

DESIGN: POLYP LAMPS

While exploring organic forms like apples, pears, and lemons, Polyp Lamps also draw inspiration from traditional Japanese Akari lamps. Their playful, glowing silhouettes feature signature tabbed inserts that create an interplay between light and shadow. Available in 13 designs, the lamps are generated from a custom parametric system. Comprising laser-cut YUPO paper and 3D-printed recycled PETG, the lamps feature standard socket bases and can be assembled without hardware or glue. jbaileydesign.com

07 JESSE VISSER: PULSE

Blending technology with nature and rhythm with balance, the Pulse lamp boasts an exquisitely detailed aluminum shade paired with a boulder as a counterweight. In addition to the single version, the fixture is available with three or five stones aligned in a row, balancing at varying heights. The solid aluminum shade is ten millimeters thick in order to level with the counterweight. jessevisser.com

08 AREA JAPAN: BLESSED STONE

Designed by Go Noda, this floor lamp features “a stone chosen by the heavenly light that fell silently that night.” The materials include a date-kanmuri stone—a unique andesite quarried from Mount Okura in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan—with an angled black-painted stainless steel rod, black-painted MDF, and an LED. The lamp measures just over 16.5 inches wide, 10.6 inches deep, and 78.8 inches tall. area-japan.co.jp

This is What Sustainable High Performance Looks Like.

As a high-performance textile made from up to 91% rapidly renewable sugarcane, Biobased Xorel® sets the standard — delivering unmatched durability and sequestering 2.5 tons of carbon for every ton of feedstock produced, all without harm to human, ecosystem, or community health.

09

The first collection by Formafantasma for Flos, SuperWire is a family of modular lamps—available in table, floor, and suspension versions—made of planar glass and polished aluminum. The table model consists of a single module surmounted by a hexagonal transparent glass cover sealed with an invisible, extrathin layer of special UV glue. The floor model features two glass modules that rest on a steel tripod in a tribute to the historic Luminator by the Castiglioni brothers. professional.flos.com

Sightlines

When you think of linear fixtures, you might picture the standard-issue office types that look nice enough but otherwise blend into the visual noise of a space. These new offerings are anything but: Their linear forms and designs generate palpable energy that guides the eyes around an interior, allowing us to make connections we might have otherwise missed entirely.

FLOS: SUPERWIRE

ABMARATHON®

RUBBER TILE &STAIR TREADS

Designed for today’s high-traffic spaces, the new ABMARATHON® collection offers improved stain resistance, underfoot comfort, and long-lasting durability. Showcasing 23 trend-forward colors curated for contemporary commercial and institutional design, ABMARATHON® is the perfect choice where durability and aesthetics merge. Available in three profiles — round, hammered, and slate — with coordinated stair treads in round and hammered, this collection is designed to adapt effortlessly to any project, from floors to stairs.

Scan to learn more about this collection: Join us at the Healthcare Design Conference, Booth 1333

Introducing ABMARATHON® , a rubber flooring collection that is not afraid to be stepped on. american-biltrite.com/flooring/abmarathon

Red List Free

10 STICKBULB: PILLAR

Known for its linear LED lights made from salvaged wood, Stickbulb explores its softer side with the curving Pillar collection. The modular fixtures feature an illuminated square pocket within a small circular wooden housing. They come in a variety of lengths and can be joined together in standard and customizable configurations, including a sconce, pendant, ceiling-mount, and chandelier. Pillar is available in hand-stained natural, white, black, and custom finishes and can be specified with matte, white, glass LED bulbs for soft, warm lighting or LED MR16 bulbs for spot lighting. stickbulb.com

11 ARTICOLO STUDIOS: SWIVEL

The Swivel collection includes single and double wall sconces and a double pendant. The fixtures combine bronze with tactile leather inlays in a variety of colors, and the linear tubes can be rotated to direct light where needed. Each fixture comes in several size options with customized versions available. articolostudios.com

12 MATTERMADE: DELPHI LINEAR

Designed by Jamie Gray, Delphi Linear is the newest addition to a lighting collection that pairs cast and machined brass with fluted glass tubing, paying homage to iconic Greek columns. It can be oriented horizontally or vertically, allowing multiple elements to be combined end to end to create a variety of compositions. The fixture features a custom LED array, providing 360 degrees of light within each cluster, and it measures 59.8 inches long, 3.6 inches deep, and 3.3 inches high and comes with a 36-inch chain. mattermade.us

A LEGACY OF CRAFT

Carl Hansen & Søn is honoured to craft the world’s largest collection of Hans J. Wegner designs, continuing the legacy of Danish modern design through elegant, functional furniture. Each Wegner design is made in Denmark using traditional techniques and responsibly sourced wood, ensuring lasting quality. With a deep respect for craftsmanship, Carl Hansen & Søn carefully balances heritage and innovation to create timeless furniture that endures for generations.

Carl Hansen & Søn is honoured to craft the world’s collection of Hans J. designs, continuing the legacy of Danish modern design through elegant, functional furniture. Each is made in Denmark traditional and responsibly sourced wood, ensuring lasting quality. With a deep respect for Carl Hansen & Søn balances and innovation to create timeless furniture that endures for generations.

BIG IDEA 03: NEUROAESTHETICS

The Architecture of Sensation

Growing research in the field of neuroaesthetics gives us a new understanding of the power of design.

By Suchi Reddy

TURBULENCE

In this 2025 installation at Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Suchi Reddy makes nature’s distress palpable. As visitors walk through two reflective passageways, they not only see themselves in a distorted view of the surrounding landscape, but also hear sounds composed by Malloy James that makes the ultrasonic distress clicks emitted by plants, audible to human ears.

WE BUILD OUR WORLD OUTWARD from our bodies—our first home. Before we can name what design is, we feel it. I remember vividly, at ten years old in Chennai, India, realizing that my home wasn’t just where I lived—it was shaping me. It influenced how I moved through the world, how I thought, how I felt. That early awareness became the foundation of my life’s work: exploring how environments shape us and how, through design, we can shape them in turn—more intelligently, more empathetically, and more beautifully.

My design practice has always been rooted in the relationship between inner experience and external form. Over time, that connection has deepened through study—both formal and intuitive. Alongside architecture, I have explored meditation, sound healing, vibration, stone medicine, and other integrative approaches to well-being. These modalities taught me to understand the body as an instrument of perception and space as something that vibrates with us. They gave language and structure to what I had always felt intuitively: that our environments are not inert containers but active agents in our health, joy, and sense of self.

This exploration led me to the field of neuroaesthetics—a growing body of research at the intersection of neuroscience, design, and the arts that explores how aesthetic experience affects the brain and body. Centering neuroaesthetics in architecture invites a profound shift: from designing for use to designing for experience. By grounding our decisions in how spaces actually make people feel—physiologically, emotionally, and cognitively—we can create environments that support mental health, foster connection, and promote equity. This approach expands the role of the architect from form maker to well-being steward, leading to more inclusive, responsive, and humane built environments.

This is especially urgent since over 20 percent of the global population identifies as neurodivergent. Their experiences must no longer be treated as edge cases. When we design for sensory sensitivity, for overstimulation, for cognitive friction, we design better for everyone. Neuroinclusion is not a constraint. It is a creative and ethical imperative.

For the other 80 percent of the population—when we are collectively navigating

A SPACE FOR BEING

Created for Google for Milan Design Week 2019, this installation analyzed visitors’ sweat levels, skin tension, and heart rates as they walked through and interacted with the objects in three different settings. Reddy collaborated on this project with Ivy Ross, Google’s vice president for hardware design, UX, and research; Muuto design director Christian Grosen; and Johns Hopkins University International Arts + Mind Lab executive director Susan Magsamen.

ME + YOU, DETROIT

When people step up to this installation and speak a word that relates to their vision of the future, it uses open-source AI technology to express that word as patterns of light, color, and sound that shimmer through the sculpture. Debuted at the Smithsonian’s FUTURES exhibition in 2021–22, me + you was installed at Detroit’s Michigan Central Station in 2024 to mark its reopening.

political polarization, rising mental health crises, and accelerating climate instability— this shift is not just timely, it’s necessary. People are seeking spaces that restore rather than extract, that connect rather than divide. The built environment must evolve from a background condition to an active contributor to individual and collective resilience. Neuroaesthetics offers a way to reimagine architecture not as a neutral stage for life, but as a cocreator of health, empathy, and regeneration in a world that urgently needs all three.

In my own work, this understanding has taken many forms—ranging from rigorous, data-driven collaborations with scientists and health-care institutions to poetic spatial gestures that speak to the emotional, cultural, and sensory dimensions of being human. In 2019, I cocreated A Space for Being, an immersive installation at Milan Design Week in collaboration

with Google, Muuto, and the International Arts + Mind Lab at Johns Hopkins University. Visitors wore custom-designed bands that recorded biometric data as they moved through three distinct spaces, each composed with a unique palette of colors, textures, lighting, proportions, and sound. Though each room served the same function, people’s bodies responded differently. The data showed that design has measurable effects on stress, relaxation, and emotional resonance. This was not just a poetic truth—it was scientific proof that how we design truly matters.

This same philosophy guides our approach across typologies: residential, hospitality, and retail. In residences, we design environments that reflect and support the emotional and sensory needs of the people who inhabit them—crafting places for creativity, restoration, and belonging. We reorient views, adjust

proportions, and integrate natural materials to amplify presence and calm. In one home, we reorganized the entire floor plan to improve flow, deepen connection to nature, and activate the senses through curated textures, lighting, and rituals of daily life. Through warm palettes, soft edges, diffused lighting, and tactility, we shape experiences of welcome and restoration.

To me, the future of architecture is not in spectacle—it’s in sensation. Not in how buildings look, but in how they help us live. Feeling is not a trend. It is a universal and deeply human truth. When we design from the inside out, we create spaces that heal, connect, and empower us. M

Suchi Reddy, FAIA, is an architect, designer, and artist based in NYC. In 2002, she founded Reddymade, which focuses on public art installations, large-scale commercial spaces, and residential projects ranging from single-family homes to interiors and prefab architecture.

The Biodegradable Vinyl

BIG IDEA 03: NEUROAESTHETICS

5 Smart Designs That Boost Brain Function

By Lauren Volker

FROM FRACTAL-INSPIRED SURFACES to adaptive seating and sensory sanctuaries, these commercial products integrate neuroscience and biophilic design principles to support brain health. Designed with visuals, materials, and features that are proven to reduce stress, enhance focus, and promote cognitive function, they help create environments where people can work, learn, or rest with greater clarity and ease.

Developed by KI based on research into neuroscience and learning, Cogni classroom seating supports brain health and focus through movement, posture flexibility, and sensory engagement. Its cantilever frame encourages micromovements that boost blood flow and attention, while a patent-pending surface supports students—especially those with sensory processing needs—who seek tactile input to self-regulate and stay focused. It is ideal for K–12 settings thanks to an antitip design with patent-pending heel-wheel technology and a minimalist silhouette available in a modern color palette. ki.com

KI COGNI

This This space was designed by John Beckmann of Axis Mundi, space was John Beckmann of Axis featuring the Cerebral Matter mantle from his Altared States the Cerebral Matter mantle from his Altared States collection collection exclusively for ABC Stone. exclusively for ABC Stone.

MOMENTUM RENATURATION

Momentum’s Renaturation collection, developed with 13&9 Design’s Martin and Anastasija Lesjak and fractals expert Dr. Richard Taylor, harnesses the stress-reducing power of natural patterns. Taylor’s research shows that exposure to fractals with optimal complexity (measured by a “D-Value”) can reduce stress by up to 60 percent in just ten seconds. The wallcoverings’ patterns are scientifically calibrated to a D-Value of approximately 1.7—shown to be effective across diverse populations, including neurodivergent individuals. The PVC- and PFAS-free collection includes Fractal River, Moss, and Bark, each available in multiple colorways.

momentumtextilesandwalls.com

Armstrong® Wood Looks

Inspired by nature, designed for quiet

Capture the warmth and beauty of real wood with stunning finishes in wood-look visuals. Add whisper-quiet acoustics, like NRC 0.95, and sustainably smart durability that contribute to LEED credits. Order samples at armstrongceilings.com/quietdesign. Order

MOHAWK GROUP

CONNECTD

Developed with Fractals Research and 13&9 Design, Mohawk Group’s connectD 2.5 | 5.0 LVT features calming fractal patterns inspired by nature. Available in 18-by-36-inch tiles in 2.5-millimeter (glue-down) and 5-millimeter (loose-lay) options, it includes a 20-mil wear layer and M-Force™ Ultra protection. Part of the carbon-negative Hot & Heavy II collection, it’s NFSI certified and integrates with carpet tile. In addition, it is available in 14 QuickShip colors across three biophilic patterns. mohawkgroup.com

SIGNIFY

NATURECONNECT SKYLIGHT GEN3

Skylight Gen3 is the latest addition to Signify’s NatureConnect system, designed to re-create the dynamic patterns of natural daylight indoors. Rooted in biophilic design and powered by nature-inspired algorithms, the faux skylight delivers melanopic light doses throughout the day to support circadian rhythms—helping people feel alert by day and restful at night. Ideal for work, health-care, hospitality, and education spaces, the two-by-two-foot luminaire features an intuitive user interface and dual 0–10 V inputs for precise control. signify.com

SILEN ZEN

Silen Zen transforms any Silen office pod into a sensory sanctuary tailored for high-performance work environments. Drawing on research into the impact of mindfulness-based interventions, the add-on supports stress reduction, enhances focus, and fosters creativity. With smart-glass Privacy Mode, ambient lighting, and immersive soundscapes—like rainforest, ocean waves, and meditative music—it offers a restorative pause that helps people regulate emotions, clear mental clutter, and return to work refreshed.

silen.com

WHEN PERFORMANCE MATTERS

The original high performance real wood flooring. Built with pride in Pennsylvania since 1968.

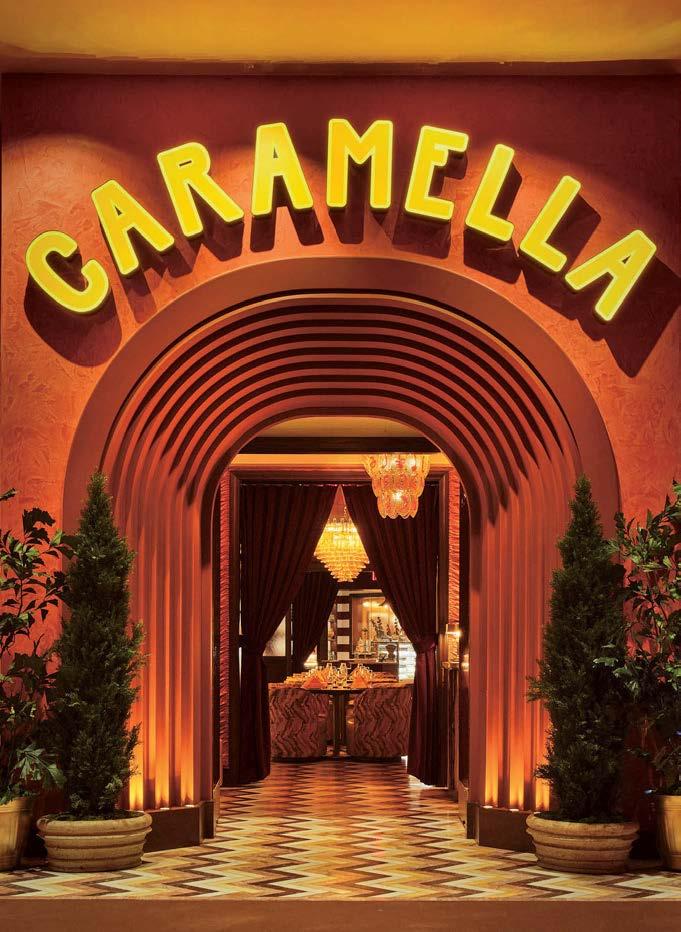

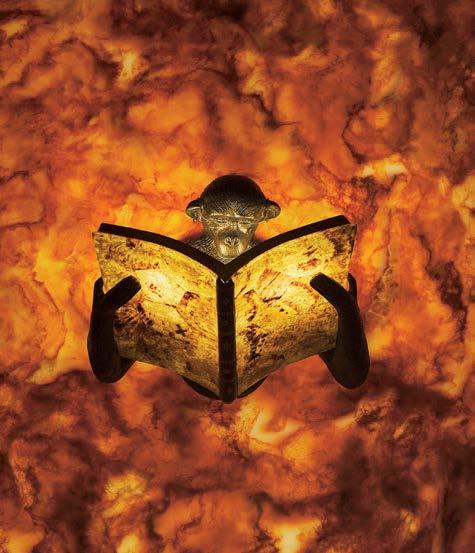

BIG IDEA 04: SCENOGRAPHY

Cinematic Hospitality Spaces That Put Guests Center Stage

From Las Vegas to Brooklyn, immersive interiors are embracing moody materials and theatrical flourishes to create unforgettable experiences.

By Lauren Jones

IN A SEA OF SAMENESS, hospitality designers are curating immersive spaces centered on stylish circulation, authentic storytelling, and polished materiality. On the Vegas Strip, Caramella—Planet Hollywood Resort & Casino’s newest restaurant—channels 1970s Italy. In Houston, Asian steakhouse Haii Keii blurs the boundaries between imagination and tradition, while in Brooklyn, Unveiled delivers an alluring subterranean retreat with amorphous seating and a reflective dance floor.

Created by Gin Design Group, Houston’s Haii Keii restaurant blends a modern Japanese ryokan concept with neon, cyberpunk features inspired by the streets of movies like Blade Runner.

HAII KEII

Dining at Houston’s Haii Keii is like stepping onto a science-fiction set, its saturated and futuristic palette drawing on films such as Blade Runner and Kill Bill. Designer Gin Braverman calls it “a surreal and cinematic reimagining of a Japanese ryokan.” While the owner aimed to bring “something really experiential and elevated to Houston in the way that Miami and Vegas have highly conceptual restaurants,” the brief was open-ended. Braverman set out to achieve “the experiential and visceral” by flipping tradition in favor of the unexpected. “I wasn’t going to do cherry blossoms,” she says.

Instead, the 3,000-square-foot interior centers on a glowing, inverted eight-foot bonsai tree and a set of shoji-style screens that wrap the upper level. “We put a samurai in there for fun, and every once in a while, he comes around,” she says of the rotating shadow projections that animate the space. Guests arrive through a glowing red glass door and navigate a narrow hallway lined with etched lucite screens before emerging into the dramatic, double-height dining room.

Curved black plastered walls set the tone, while black leather booths are wrapped

in more than 4,000 linear feet of red rope—an idea inspired by a dumpling den Braverman visited in Japan. Velvet upholstery softens the scene, while the backlit bar gleams with a powder-coated top and a scalloped brass mesh base. “There’s something about the way the colors come together,” she says of the bold red, turquoise, and purple palette. “It’s very physical.”

At mezzanine level, a private dining room is tucked behind thick black curtains and a keyhole-cut wall. “It has this circular, fishbowl-like window that feels like you’re in some high-rise in Tokyo,” she says.

While Braverman is no stranger to hospitality design, Haii Keii stands apart. “This project really let us open the floodgates on creativity,” she says. Conceived and built over approximately 18 months, it involved a close-knit team of collaborators, including a light artist, fiber artist, plaster specialist, and upholsterer. “It took an amazing team of people to pull this off.”

The result is a space where lighting, material, and mood constantly shift— immersing guests in something that feels elevated and highly choreographed.

Bold red elements are woven through the restaurant's seating areas, “balancing seclusion with voyeuristic tension.” Even the restrooms extend the illusion—glowing doors and coordinated fixtures make every moment part of the performance.

The designers wanted the restaurant to blend “reality and illusion”—Charred beams, obsidian pebbles, lacquered surfaces, and reflective mirrors warp perspectives, while oversized shoji screens, an inverted bonsai bar canopy, and shadowy portals create a journey of intrigue.

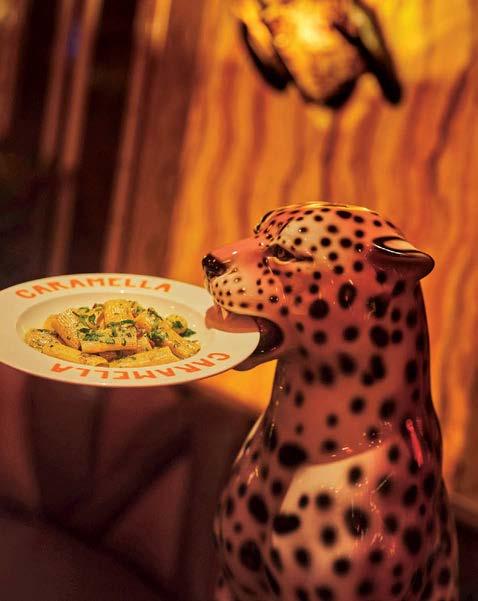

CARAMELLA

A bar, restaurant, lounge, and sweetly hidden speakeasy provide Vegas visitors a new destination to playfully peruse. Once a disjointed restaurant, the 9,500-square-foot space has been reimagined by Tao Group and Fettle Design cofounder Tom Parker as a maximalist ode to all things Italia.

The brief called for a “concept-driven restaurant that was very much 1970s Italian disco inspired,” Parker says. “A lot of the Tao Group restaurants are clubby as much as they feel like a restaurant.” The initial

imagery was “over-the-top fun and tonguein-cheek,” he adds, nodding to the Italo disco movement—a bold blend of musical and architectural experimentation that inspired iconic nightlife venues like Studio 54 and Italy’s Baia degli Angeli, placed high above the Adriatic.

Because guests must pass through the casino’s cavernous concourse before arriving at the mezzanine-level Caramella, Parker and team found it crucial to “recalibrate the scale after that journey,” he says. “So we created a

fabric-draped vestibule that acts as a kind of decompression chamber.”

Inside, the new layout—achieved by following the boundary of the original kitchen and reorganizing the multiple dining experiences—breaks the vast footprint into immersive zones. There’s a sweet shop, which conceals a speakeasy, as well as a bar, main dining area, and back patio, all seamlessly awash in whimsical, richly hued fabrics.

The palette is pulled directly from the era with orange, brown, and warm reds in Missoni-esque zigzag and other geometries, while Murano chandeliers and custom furnishings punctuate the stylish Italian way of life. “There’s a lot of patternon-pattern, marbling, and almost every fabric and wall finish we selected had a bit of a ’70s twist to it,” he says. In the speakeasy, kitschy leopard print adds a “colorful, bold, and jazzy” touch, he notes.

The project marked a turning point for Parker’s team. “It encouraged us to lean more into narrative design,” he says. “Even when the outcome isn’t this visually intense, the storytelling approach has stuck with us.”

entrance passes through a functioning candy shop—glass jars of sweets lining wooden shelves—before opening into a darker, moodier lounge. Tao Group and Fettle contrast the brightness of the shop with mirrored walls, low jewel-toned seating, and overhead sculptural lighting, creating a clear shift from playful display to intimate dining.

Caramella's

Perched on Planet Hollywood’s mezzanine, Caramella channels 1970s Italian glamour with warm gold hues, plush seating, and retro glamour—its elevated location also offers sweeping views of the Las Vegas Strip.

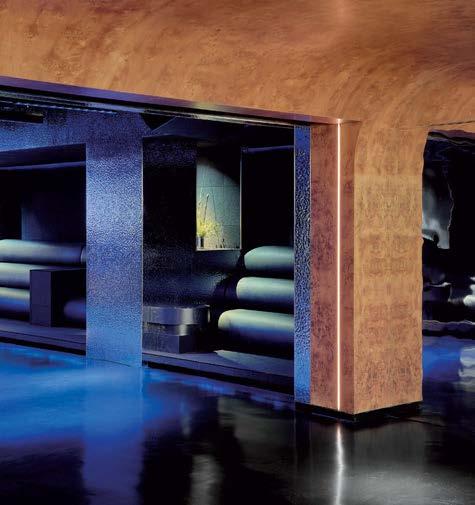

In a raw concrete basement beneath the William Vale Hotel, Studio MBM and Yakka Studio have crafted a bold, sensuous lounge called Unveiled.

UNVEILED

Below Williamsburg’s William Vale Hotel, Unveiled has turned a formerly underutilized basement into the coolest cocktail bar and club in town. “We were given this underground space that the hotel didn’t know what to do with,” says designer Maurizio Bianchi Mattioli of Studio MBM. The goal: an electric and high-end hospitality escape designed for total immersion.

The L-shaped basement, which came with initial challenges such as awkward circulation, large columns, and plumbing infrastructure, also brought an opportunity to compose two “very different environments that were still related in terms of texture, materiality, and volume,” says the designer. While he and his team started with research on historic New York clubs, he knew he wanted to “go back to the core and create something highly designed, but still raw.”

Rather than taking guidance from hospitality tropes, the team paid homage to postmodern architects like Philip Johnson and Gae Aulenti, as well as included details reminiscent of vintage car interiors, elements he felt could be translated into a contemporary setting. “The leather, the wood, the reflective lacquer—all of that set the tone for the material palette,” he says. The main bar area includes “heavy burl wood that formed geometries,” accented by green marble and curves that “feel almost carved out of the basement.” The ceiling was left as is and painted black, a simple choice that further contributes to Unveiled’s moody tone.

The seating arrangement, which Mattioli called the activator, generates different table sizes for unique usage throughout the evening. “People sit on top of it, on the side—it’s a much more dynamic central element,” he says.

For the club, that spatial rhythm continues with an equally playful iteration. Seating is placed around the edges, while the center is left open for dancing. “The DJ booth became the central altar—it’s church-like in a way.”

A half-mirror, half-perforated metal facade behind the booth creates trippy reflections and fluid movement. Lighting by Kawa Lighting changes constantly, reshaping the room moment to moment. “You suddenly find yourself slightly under a ceiling curve, then emerge into a different zone. It’s unexpected and active.” Patrons may even catch themselves in the mirrors.

The bathrooms are part of the experience too, featuring triangulated vanities, reflective walls, and stepped staging. “They’ve become social spaces,” the designer says. “The whole place is designed for performance—yours included.” M

The designers layered sensual materials—a burl plywood entry inspired by classic automotive interiors, a marble bar, shimmering metal walls reminiscent of a disco ball, and plush, moss-green sofas—all orchestrated to balance intimacy, drama, and acoustics.

massimo gatelli head of material research, impact acoustic

we we are on am a mission.

We’re here to redefine what’s desirable—elevating new materials, reshaping circularity, and setting a bold new template for the architecture and design world. This isn’t just a sustainability policy; it’s our promise, our passion, and the blueprint we live by.

sven

erni and jeffrey ibañez

founders, impact acoustic

A trio of vibrant paintings by artist

are newly transmuted into a collection of hand-knotted rugs inspired by different periods and places she has lived and worked. The soft New Zealand wool rugs elevate Chontos’s dynamic abstractions through techniques such as abrash dyeing, which introduces color shifts for a natural finish.

layeredinterior.com

8 Tone-Setting Products Shaping Guest Experience

By Will Speros

SUBTLE AND EXPERIENTIAL DESIGN TRENDS converge across a range of new products, reflecting hospitality’s influence on craftsmanship through refreshing perspectives on function and form. Enriching color palettes deepen storytelling, while pure materials anchor built environments with integrity and tactility. Here, eight refreshing designs promise to elevate interiors with luxurious statements that are as functional as they are formal.

01 HEATHER CHONTOS X LAYERED

Heather Chontos

MOBILE SURVEILLANCE

Invisible Security

Security Design is currently based on restricting access and protecting perimeters. Invisible security in contrast foresees free access.

Invisible security uses data, technology and design to secure places. Everywhere and at any point in time.

While putting security at its core, it respects public acceptance, privacy and convenience, in order to make physical spaces not only safe, but also frictionless, trustworthy, and liveable.

CONTINUOUS AUTHENTICATION

VIRTUAL PERIMETER

BEHAVIORAL ANALYTICS

CONSENT-BASED IDENTITY MANAGEMENT

02 FIJI FROM PORCELANOSA

As part of the Porcelanosa Group, L’Antic Colonial adds six new tiles to the S-Tile Collection. Among them is the colorful, marine-inspired ceramic, Fiji, which is crafted to evoke the visual strength of the ocean. Brushstrokes and waves of color enliven the surface, with seven customizable finishes that promise to disrupt interior monotony. porcelanosa.com

03

RADIANT FROM SHAW CONTRACT

The new hospitalityfocused collection of broadloom and rugs celebrates the transformative energy of light and the revelry of human connection. Detailed with luminous metallics and intricate embellishments, Radiant is crafted to instill vitality and a sense of occasion across convivial spaces from ballrooms to intimate lounges. shawcontract.com

04 ETERNA FROM ARCA

The maiden product collaboration from Meyer Davis, Eterna, distills the natural beauty of marble through refined, thoughtful forms. Clean lines and elegant proportions distinguish each of the 11 sculptural pieces, conveying distinct architectural narratives—from framed voids to layered volumes. Eterna also showcases the singular depth and character of stone, sourcing material from 22 international quarries. arcaww.com

05 CREATIVO

BY HBF TEXTILE

Mark Grattan’s new Layered collection draws inspiration from three aspects of his persona. Creativo, embodying his identity as “the creative,” features a seductive, checkered velvet motif. The textile alternates between cut and uncut surfaces in a rhythm that is both tactile and visually appealing across eight colorways. hbftextiles.com

06 SENSA FROM COSENTINO

Six new quartzites join the Sensa by Cosentino collection with richly veined patterns that imbue personality through colorways ranging from earthy greens to dramatic blacks. Protected with antiscratch and signature Senguard NK antistain treatments, Sensa products are backed with a 15-year warranty as well. cosentino.com

07 LEDOUX PRÊT BY NATALIE SHOOK

Natalie Shook evolves her sculptural Ledoux Shelving design with a pair of ready-to-order variations tiered to customizable new heights. Rounded, perforated, and draped in aluminum, one version touts a curvilinear bodily presence evocative of midcentury experiments in lightness and transparency. The second presents a square column integrated with simple cabinetry detailed with the same perforated dot pattern. nshook.com

08 JEAN NOUVEL SEATING COLLECTION FROM COALESSE

Ateliers Jean Nouvel channels the Pritzker Prize–winning architect’s portfolio of Modernist landmarks in a versatile new furniture collection. Intricate engineering and pattern work achieve distinctive, sinuous silhouettes reminiscent of rocks in riverbeds and dunes, while a wide variety of upholstery colors and textures put a signature on the lounge chair, sofa, ottoman, and a tête-à-tête couch. coalesse.com

LOOKING FOR AN INTERIOR DESIGNER?

Hiring the right interior designer and sourcing the best products for your project can be a difficult task. Let Design Finder by ASID simplify your search with listings of:

+ Interior Designers

+ Design Firms + Manufacturers + Suppliers

Use this platform to search through project image portfolios, product examples, and resources to make your space come to life!

At American Society of Interior Designers, we believe that Design Impacts Lives and finding the right partners is a key piece of the design process. Design Finder by ASID is your go-to resource for connecting with the interior design partners who will help bring your vision to life.

AND

Where Housing Meets Humanity

By Sam Lubell

AS HOUSING NEEDS GROW MORE URGENT , a new generation of design-led responses is emerging—rooted in care, community, and climate consciousness. These three projects, from Barcelona to Austin to Palm Springs, challenge conventional models by putting people first and embracing flexibility, visibility, and dignity. Designed for public housing residents, individuals living with HIV/AIDS, and unhoused populations, they ask not what’s standard but what’s needed.

BIG IDEA 05: CARING HOMES

ILLA GLÒRIES BY CIERTO ESTUDIO

Amid Barcelona’s deepening housing crisis, Illa Glòries illustrates how publicly funded development—focused more on people’s needs than on profit margins—can drive socially driven urbanism. The 51-unit public housing block, commissioned by the Institut Municipal de l’Habitatge i Rehabilitació de Barcelona, was designed by the women-led firm Cierto Estudio as the anchor of a four-building development near the city’s Plaça de les Glòries public square.

At the heart of the firm’s competitionwinning concept is a flexible, nonhierarchical apartment layout that breaks from traditional domestic models. Instead of prioritizing a central living room or a primary bedroom, the units feature equal-sized rooms that allow residents—whether nuclear families, roommates, or otherwise—to reconfigure space according to their evolving needs. Kitchens are treated not as secluded corners but as connective social nodes, turning childcare, cooking, and conversation into the core of the home. “We wanted to make caregiving visible and shared, not isolated behind a closed

Communal balconies, rooftop gardens, and flexible layouts make Illa Glòries a people-first vision for public housing in Barcelona. Designed by the women-led firm Cierto Estudio, the 51-unit building prioritizes caregiving, adaptability, and shared space—shifting the focus from profit to collective well-being.

door,” says Marta Benedicto Izquierdo, a principal at Cierto Estudio. Diagonally aligned joints, windows, and room openings encourage cross breezes and shape long sight lines through the apartment and beyond, creating a sense of openness and expansion.

Outside each apartment, Illa Glòries emphasizes community. Generous communal balconies, green sculpted courtyards, and a rooftop garden encourage interaction and create passive safety through visibility. The balconies, which bump out in front of the units themselves, are especially wide thanks to a design decision to slightly reduce interior square footage in favor of outdoor space. “You can leave your door open and have a conversation with your neighbor,” notes Izquierdo. “This sense of threshold was key.”

The project meets the EU’s NZEB (European Union Nearly Zero Energy Building) standards and features a crosslaminated timber structure, passive cooling strategies, and over 60 percent green space, with green roofs helping to combat the urban heat island effect. A pedestrian

passageway runs through the block, ensuring permeability and activating street life with commercial spaces at ground level.

The development creates a sense of dynamic, communal urbanity that nods to the past while still fitting into the city’s newer conditions. “This project isn’t just about living spaces,” says Izquierdo. “It’s about how we take care of each other.”

BURNET PLACE BY MICHAEL HSU OFFICE OF ARCHITECTURE

Just north of downtown Austin, tucked along Burnet Road and not far from the University of Texas at Austin, an affordable housing development is transforming what it means to live—and heal—in community. Burnet Place, a 61-unit residence designed by Michael Hsu Office of Architecture for the local nonprofit Project Transitions, serves residents living with HIV or AIDS. The project is conceived as a protective, nurturing environment that’s also imbued with a sense of vibrancy.

Inspired by the armadillo, the building’s form wraps a tough shell around a soft core. The exterior—composed of home-scaled siding, sun-shading porches, colorful tiles, and an abstract mural derived from the nonpr ofit’s logo—presents an artful face to the city. The interiors, in contrast, are intentionally warm and intimate, with natural wood finishes, daylight-filled rooms, and shared spaces designed to feel like residential living rooms. “We always talked about the building as having a central womb,” says Maija Kreishman, principal at Michael Hsu. “It wraps you in a very caring hug.”

Burnet Place offers supportive housing for people living with HIV or AIDS in Austin, Texas. Designed for local nonprofit Project Transitions, the 61-unit complex blends natural wood, daylight-filled rooms, and a garden courtyard for a healing, nurturing environment.

Rather than reading as a single mass, the project is composed of a series of smaller, interlocking volumes that echo the scale and cadence of traditional town houses. Arranged around a central courtyard, these forms give each segment its own identity. “When you’re walking through the courtyard, it’s as if you’re moving through a small neighborhood,” says Kreishman. Ground-floor communal rooms support case management, medical consultations, and dining, while maintaining the feel of a domestic space.

The courtyard, designed by longtime collaborators Nudge Design, includes community gardens, angled walking paths, and outdoor benches. An elevated porch bisects the complex in the spirit of a Texas dogtrot house, allowing breezes to pass through while offering shaded space for

residents to sit and observe daily life in the garden below. “It’s really about creating moments of pass-through activity where you meet your neighbors and come together,” says Kreishman.

With a one-star rating from Austin Energy Green Building, the project incorporates on-site rain gardens for stormwater management, native and adaptive plants, and alternating hard and porous materials to provide both sun shading and cooling breezes. Its design—rooted in regional tradition yet decidedly contemporary—offers a nuanced alternative to the standardized models of midscale urbanism in the area.

“I’ve always wished cities had more of these,” Kreishman adds. “It’s meaningful to support a mission like this. The building doesn’t just provide shelter—it provides dignity.”

Inspired by the armadillo, the design combines a tough exterior with a soft, inviting core. The architecture encourages casual encounters, neighborly connection, and a sense of belonging.

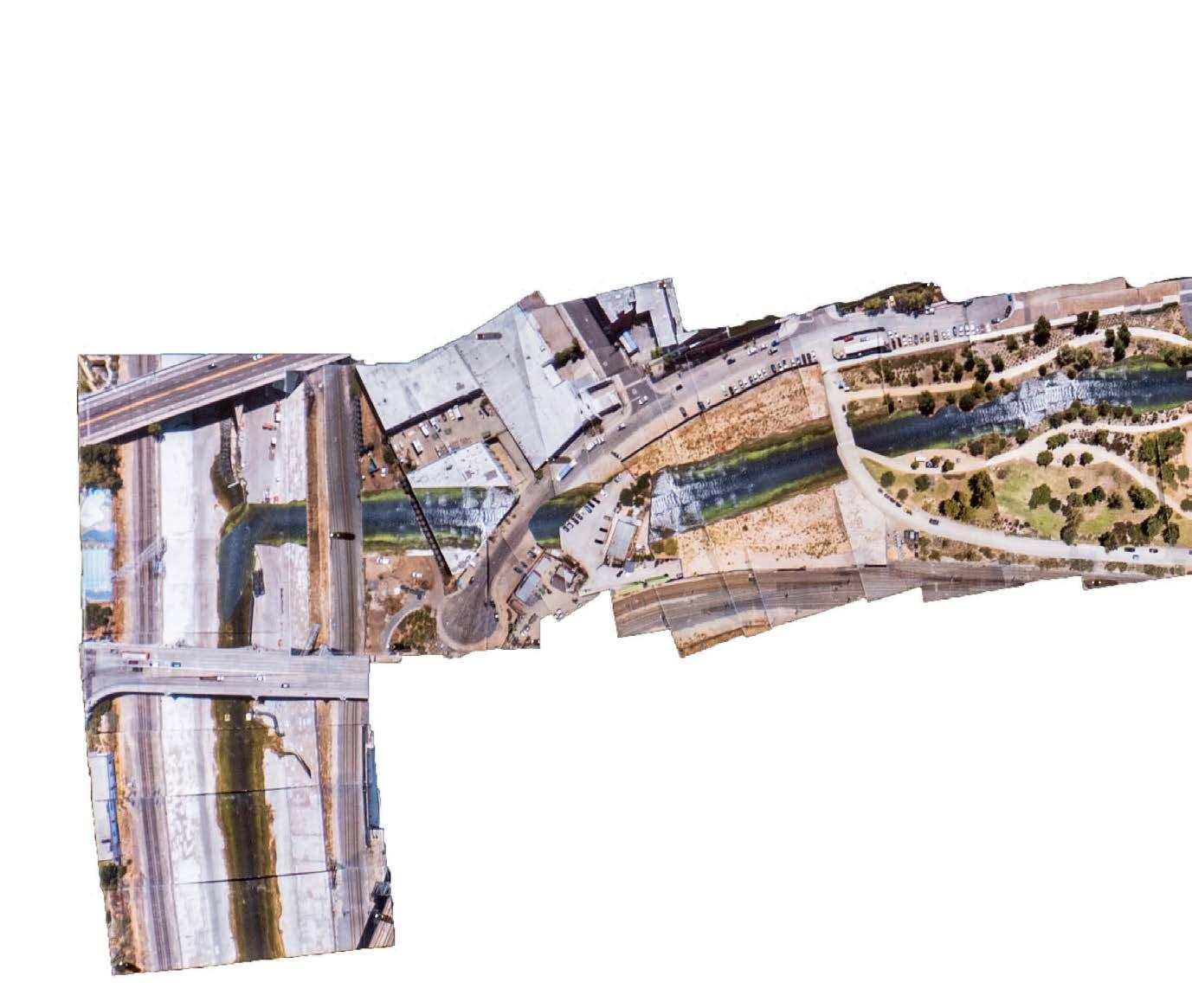

PALM SPRINGS HOMELESS NAVIGATION CENTER BY JFAK

The Palm Springs Homeless Navigation Center, a product of John Friedman Alice Kimm Architects (JFAK), opened at the end of last year and is one of a new generation of nurturing, multifunctional facilities transforming the way we think about housing the unhoused. Consisting of 80 modular housing units, varied outdoor spaces, and two repurposed warehouses offering support services, communal activities, and emergency beds, the $40 million center is a place, not a shelter—an extroverted sanctuary of hope, not a hastily assembled facility tucked away from public view.

“It’s a city for people to get help, whether they need it for eight hours or six months,” noted JFAK cofounder John Friedman, adding that the project combines “a kind of density with a sense of community.”

JFAK, selected via RFP, collaborated with contractors Tilden-Coil Constructors, fabricators California Modulars, landscape architect Esther Margulies, and the center’s operator, Martha’s Village and Kitchen. Designed and built in just a year and a half, the center inspires movement, interaction, and community. It’s a local centerpiece, not a liability.

The one- and two-story, factory-built modular residences are set perpendicular to the spine in a layered, slightly angled configuration that provides ample natural light and air but still protects from what can be harsh amounts of both. Inside, simple but airy units maximize views and cross ventilation, but with relatively small windows to reduce heat gain and glare.

Modular housing, green space, and support services come together in the vibrant JFAK-designed Palm Springs Homeless Navigation Center. Bold graphics, with warm hues greeting the sunrise to the east and cool tones reflecting the sunset to the west, bring rhythm and orientation to the design of the emergency housing facility.

Elevated walkways weave between buildings, providing shade and connection, while open-air corridors ensure that every resident—whether in a ground-level unit or a second-story home—has a clear view of the nearby San Jacinto Mountains. Graphics provide wayfinding and identification via large, colorful letters, and establish an artful sense of place via color and pattern.

As for the site’s two warehouses—repurposed steel-frame structures that originally had no insulation and were leaking—the team effectively built new buildings within. The first warehouse was transformed into a hub

of essential services: a commercial kitchen, communal dining area, laundry facilities, case management offices, and job training programs. Gathering areas have double heights, wide hallways, and colorful graphics that both welcome and orient. The second warehouse, known as the Early Access Center, offers 50 overnight-shelter beds.

The project’s biggest challenge, remembers firm cofounder Alice Kimm, was to create a special, humane place that wasn’t too nice. “The operator was afraid people would never want to leave,” she says. (Residents are encouraged to stay for

a playground, and even a

six months before finding more permanent housing, with help from the center’s staff.)

Ultimately, the design team struck a balance—warm and colorful, but not indulgent, comfortable but still transitional. The approach proves that emergency housing doesn’t have to feel institutional, and modular design doesn’t have to be rigid or impersonal. M

A wide central promenade (above) serves as the slightly sloped site’s spine, linking the varied facilities—including a communal dining area, studios, and two-bedroom homes for families (opposite)—each connected to the desert landscape through drought-tolerant gardens, walking paths,

dog run.

BIG IDEA 06: NEW CIVICSCAPES

The Architects Shaping NYC’s Public Life

On NYC’s 400th birthday, we talk to Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Weiss/Manfredi, and Marvel about civic spaces that are part of the city's infrastructure.

By Francisco Brown

When Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux designed Central Park in 1857, they weren’t just advocating for public health and urban equity—they were also leveraging a strategic understanding of how green space could drive land value, redevelopment, and, ultimately, displacement. This double legacy continues to shape the city, and architecture plays a part.

Today, some of the most prolific architecture studios in the city—Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Weiss/Manfredi, and Marvel—are reimagining the boundaries between buildings, landscape, and civic life, transforming infrastructural rem-

nants and underutilized land into shared assets while navigating complex politics.

Projects like the High Line, Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park, and Bronx Point Park demonstrate how adaptive reuse, resilience planning, and publicprivate partnerships are remaking parts of the city’s waterfronts and former industrial zones into new public realms.

This work builds on a century of evolving strategies: from 1960s POPS (privately owned public spaces) zoning to Open Streets, schoolyard conversions, and tactical urbanism. Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s design strategies at Lincoln Center and Weiss/Manfredi’s approach to

resilient public parks design both reflect a desire to make civic spaces more inclusive for residents and financially beneficial to the myriad private and public partnerships that run the city’s public spaces. Yet the challenge remains: How can architects design public spaces without accelerating exclusion or speculation? In a city shaped by activism and constraint, these firms are not just building spaces—they’re reframing what civic life can look like.

Senior editor Francisco Brown spoke with the architects about how their recent projects are shaping public spaces in NYC. These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

ELIZABETH DILLER AND CHARLES RENFRO, DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO

Francisco Brown: The work at Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R) has not only produced some of the most visited and emblematic public and cultural spaces in New York, but you’ve rethought the boundaries between private and public spaces. When did that start for you?

Liz Diller: I think it began when we started our practice in the 1980s, and we did Traffic, our first public installation, with street cones at Columbus Circle. It was a field of traffic cones, distributed to fuse the various “traffic islands” into one “smoother space.” It was one of the hardest areas to cross in New York City because of congestion, and we took interest not in the building, but the space of the vehicle and the problem of public crossing.

New York is such a real estate–oriented city, where every square inch is bought, sold, and traded. So, I think this impetus to think about public open space as part of the architectural project started there. There was this trajectory, familiarity, and comfort with working in public open spaces since the beginning.

FB: Then you won the High Line and Lincoln Center projects, which made these public art ideas into full architecture projects...

LD: Those came one after the other. And they made us think about permanent work in public open spaces, which was a different mindset than we had before. These new projects were addressing a broader public, and they had to work for an extended period of time, not just a season. They were real investments.

When we did our Lincoln Center work, its existing spaces were not for public use. They were just places between buildings. It became a dominant theme to bring culture out of these institutions, which are effectively private institutions. You had to buy a ticket to get in, therefore

Diller Scofidio + Renfro's installation, Traffic (above), was the winning proposal in a 1981 competition organized by the ReVisions program of the former Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies. Opening in 2009, and designed in collaboration with James Corner Field Operations and Piet Oudolf, the High Line is a 1.5-mile-long public park built on a former elevated railroad in Manhattan (opposite).

making these outdoor spaces an extension of those institutions, which were truly public. It was about democratizing what was always there, but never used, and making it habitable.

FB: The High Line and Lincoln Center projects were highly successful interventions in the city—but also had complicated, even unfortunate, consequences for some of the surrounding communities. What lessons were learned?

LD: The High Line grew eight blocks at a time like sausage links. And with each phase, it was increasingly popular. This project was a very big lesson that we learned over time: We should have anticipated more success and leaned on developers to add affordable housing and to put in more checks and balances so it wouldn’t be a runaway for the real estate market. But all in all, I’m very proud of it. And I wouldn’t have done anything differently on the design.

Charles Renfro: We wanted to make the park about New York City and the spaces and places it passed through. It was more a piece of infrastructure when it was a rail track, and now it’s become a bit of a theater experience. I think it’s more cinematic, even.

FB: Your work seems to connect design strategies, programming, and, yes, cinematic experiences. How do you deal with hybrid public-private clients?

LD: Public-private partnerships serve the public best when the private sector values public spaces. The Google [Pier 57] project is a great example, with the private part sandwiched between two public spaces. It would have been terrible if Google had just privatized the entire pier.

The city typically wants the parks and public spaces but doesn’t really fund them. Therefore, we have conservancies and trusts to raise money. The city doesn’t have enough money to do it all. It needs private investment. G ood design and architects that are willing and able to cross the line on both sides to make it work for the client, and make it work for the public, are crucial.

FB: Another public-private example is Casa Belongó. What was key there?

CR: Casa Belongó is the home of the Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra in East Harlem, right underneath the Metro-North train track. So, it’s both an awful site and a fantastic site. We convinced our client to open the entire institution to the street and the public during the day.

We used the [building] section to allow views from above and down into the depths of a performance space, making it part of the street. Another [part] is a center, which can be used by community members and organizations to have meetings and other activities. We’re trying to make Casa Belongó belong to the neighborhood.

FB: What would you recommend your peers, or planners, ask their clients?

LD: The city of New York is a grid city, based on traffic and efficiency. We have sidewalks and streets, but we don’t have many public spaces. Inside some of our tall buildings, you have vast lobbies that are totally empty. Why not develop these beautiful s paces, which are often available, into public spaces where tenants and the public can come together? There could be businesses, retail, places for coworking.

We’re questioning the norms of how we treat the city and where we draw the line between public and private. I also think of cultural institutions; if they want to survive, they need to make new audiences. They need to carefully consider how to bring culture outdoors and how to provide adequate space for unticketed guests.

The 2009 redesign of Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall (opposite) transformed the 1960s multipurpose venue into a publicly accessible performance space. Casa Belongó (this page) is the future home of the Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra, located in a new 340-unit affordable housing project in East Harlem.

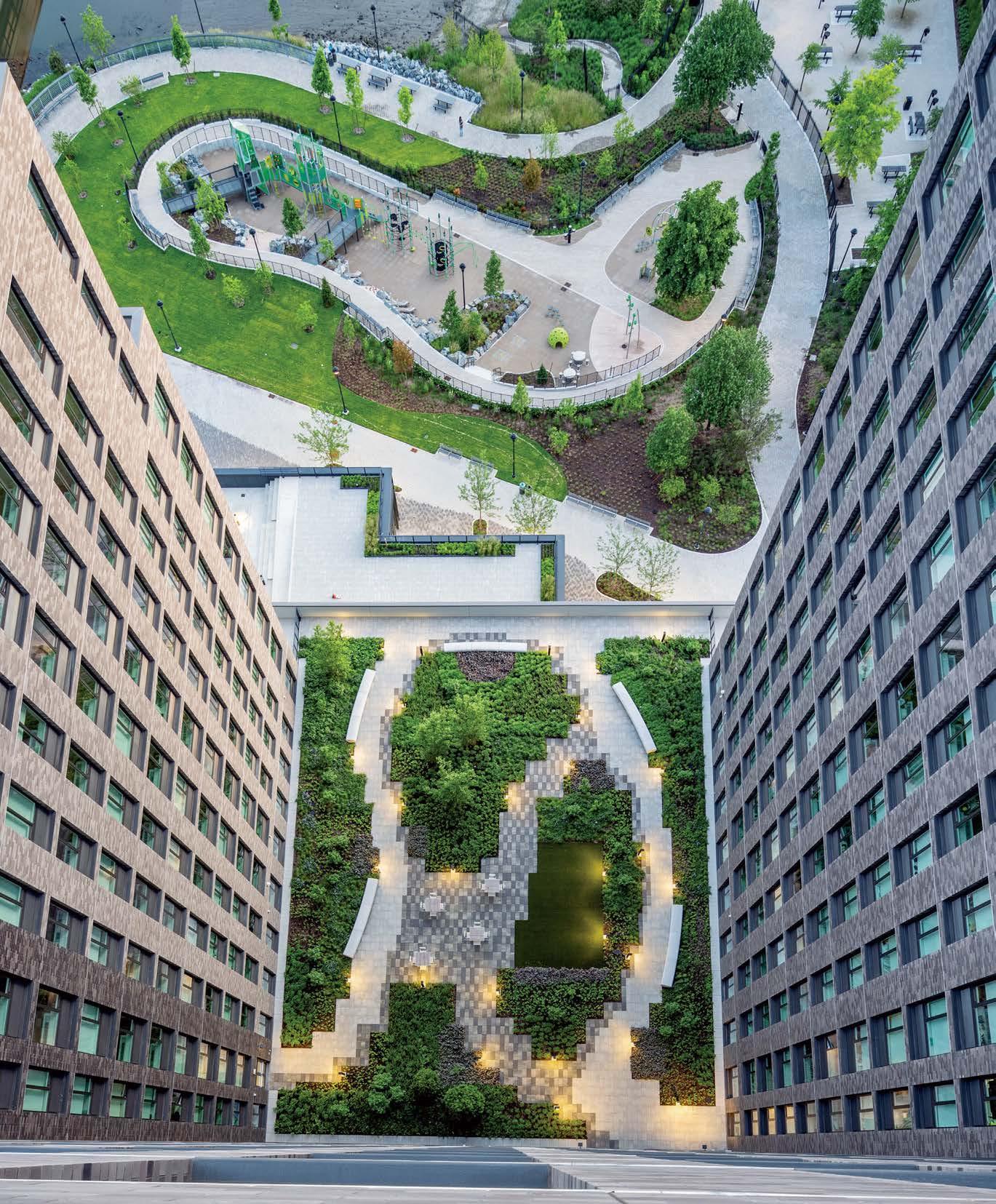

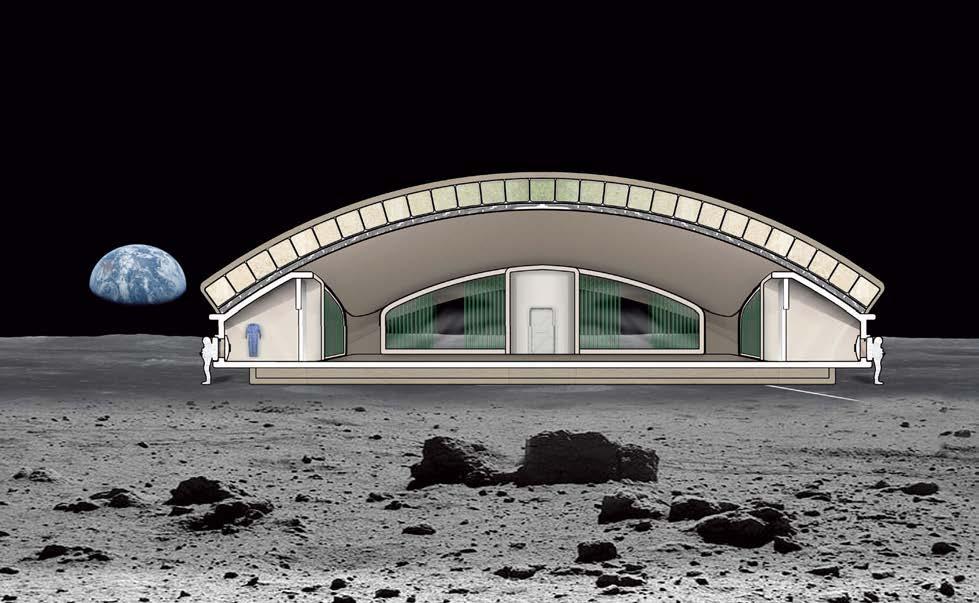

In 2018, Weiss/Manfredi transformed 30 acres of post-industrial waterfront into Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park, a public space in Queens, that simultaneously acts as a rising-water protective perimeter for the neighboring community.

MARION WEISS & MICHAEL MANFREDI, WEISS/MANFREDI