Space

Is design connecting communities or deepening differences? DESIGN THE FUTURE September/October 2023

for Contemplation

Woven with energy. Love for color and design. Commitment to innovation. To us, it’s not just material. It’s passion, pride, performance, and beauty. A legacy built over 50 years. Together with you, we will continue to create— Today, tomorrow and for decades to come.

Arc-Com.com GLYPH COLLECTION ~ In collaboration with House Industries

Upholstery | Wall Surfaces | Privacy Curtains | Drapery | Panel | Digital | Custom

Image by Imperfct*

Image by Imperfct*

Artful acoustics for welcoming spaces

turf.design

Plaid Ceiling Scapes

YEARS OF SHADE REVOLUTION

OCEAN MASTER MEGA MAX CLASSIC TUUCI.COM

MEGA SHADE. MEGA PERFORMANCE. SUPERIOR WIND RESISTANCE

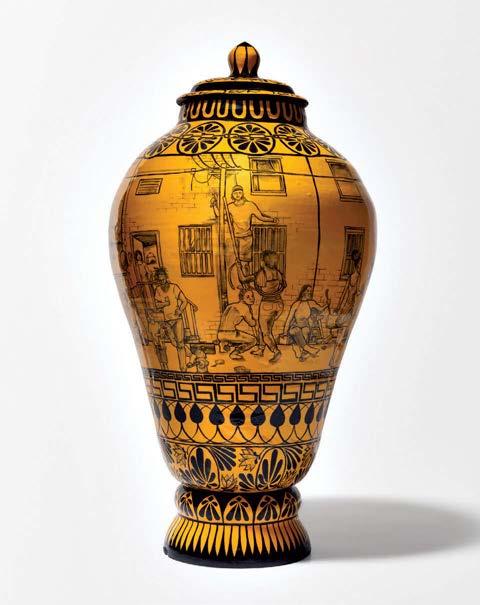

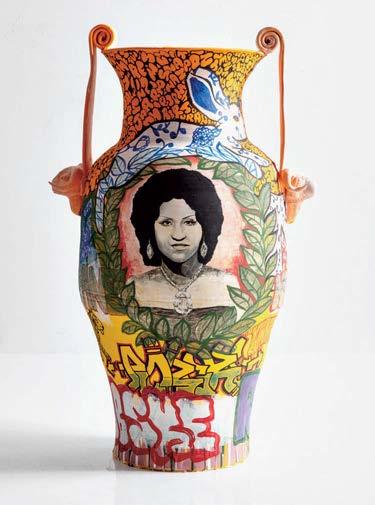

Community Made in Clay 86

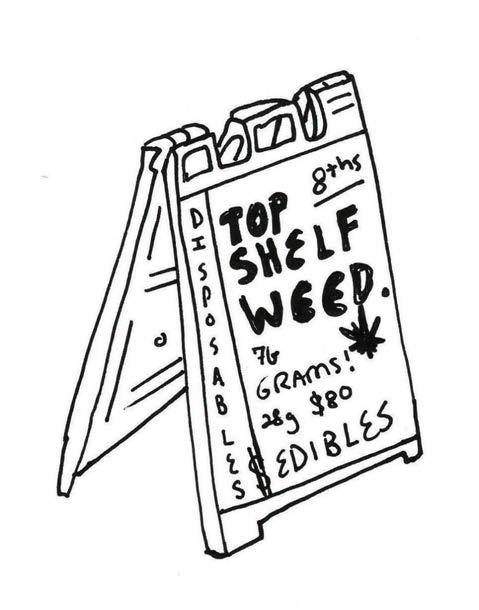

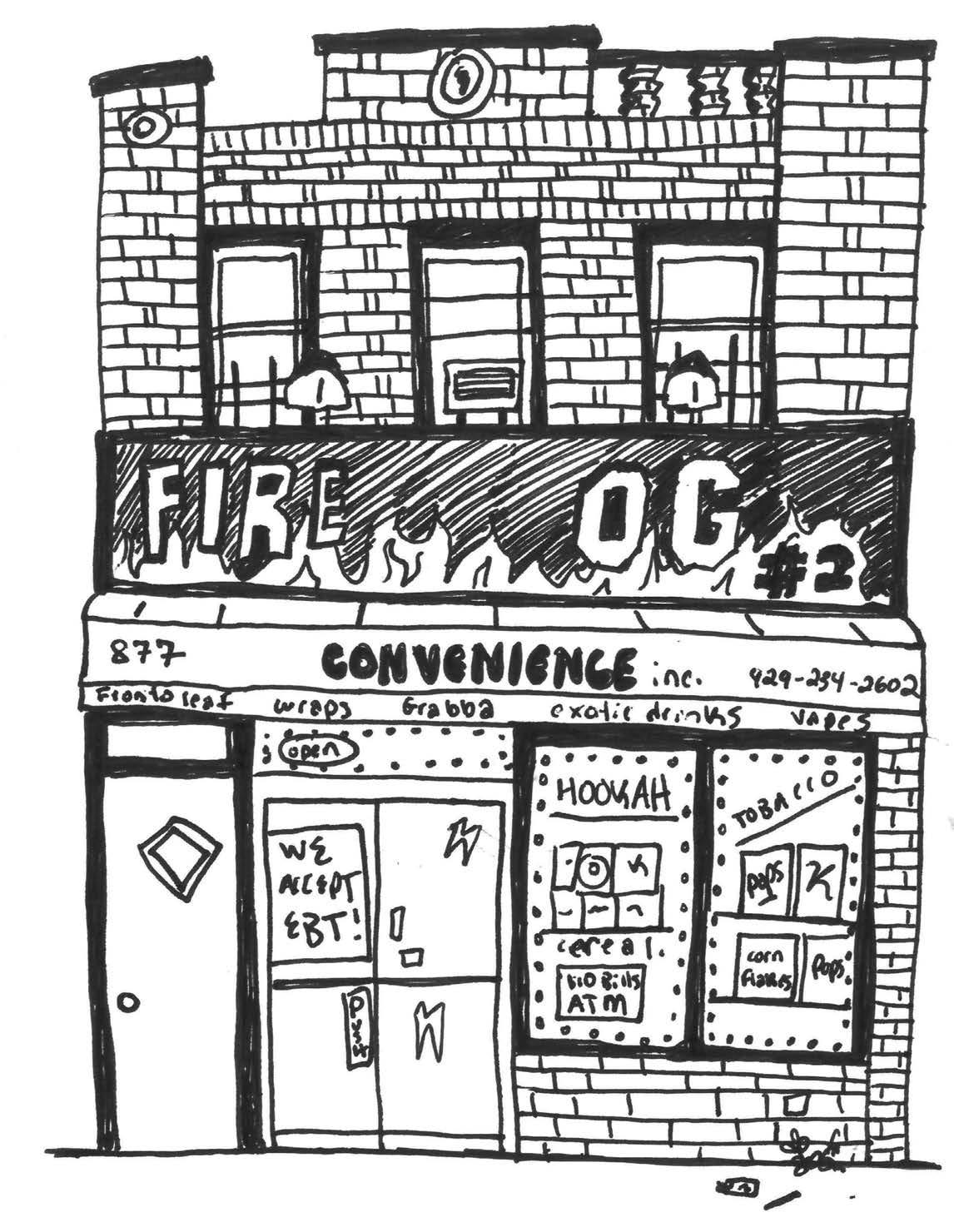

High Design 96

Following the legalization of recreational cannabis, New York City faces an identity (and equity) crisis when it comes to dispensary design.

Mixing It Up in Memphis 108

A

United We Stand 116

It’s that time of year when METROPOLIS asks design professionals how they’re navigating pressing industry issues. Executives steering America’s most influential A&D associations answered by highlighting futurism, advocacy, and data collection.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: COURTESY © 2023 HALKIN MASON PHOTOGRAPHY; COURTESY JAXSON STONE; COURTESY E. JASON WAMBSGANS; COURTESY LAKISHA ANN WOODS; COURTESY KHOI VO; COURTESY © SCAPE & TY COLE

FEATURES

The Clay Studio puts down new roots in Northeast Philadelphia with a state-of-the-art facility designed by local firm DIGSAU.

new park on the Mississippi River waterfront is part of a plan to help different classes, communities, and histories commingle.

METROPOLIS 8 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

Fabrics that party.

For design that exceeds expectations, nothing ordinary will do. Crypton fabrics bring luxury, performance, and a wealth of style options to the party.

Keep the party going at crypton.com.

SPAIN

ADEX USA

A-EMOTIONAL LIGHT

ALARWOOL

BOHEME DESIGN

BOVER

CASADESÚS

COMERSAN FABRICS & DECO

DUPLACH GROUP

DURSTONE

ESTILUZ

EXPORMIM

GANCEDO

iSiMAR

JOVER

VALLS/ ANTIQUE BOUTIQUE

KRISKADECOR

LEDS C4

LLADRÓ

NANIMARQUINA

NATURTEX

NOVOLUX LIGHTING

NOW CARPETS DESIGN POINT PUNT ROCA RESOL RS BARCELONA SYSTEMTRONIC SANTA & COLE WOOP RUGS WOW DESIGN IS IN Nov 12th & 13th 2023 BDNY EUROPEAN REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FUND A WAY TO MAKE EUROPE www.spainisin.com @interiorsfrom_spain

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: COURTESY FLOS; THOMAS TEAL; © BUILT WORK PHOTOGRAPHY CONTRIBUTORS 20 IN THIS ISSUE 22 SPECTRUM 26 TRANSPARENCY Bottled Up 38 FOCUS Cup and Ball 40 PRODUCTS Living Legacies 42 SUSTAINABLE Water Filter 44 DEPARTMENTS METROPOLIS® (ISSN 0279-4977), September/October 2023, Vol. 43, No. 5 is published six times a year, bimonthly by SANDOW DESIGN GROUP, LLC, 3651 FAU Blvd., Boca Raton, FL 33431. Periodical postage paid in Boca Raton, FL, and at additional mailing of ces. POSTMASTER: Send all UAA to CFS; NON-POSTAL AND MILITARY FACILITIES: send address corrections to METROPOLIS, PO Box 808, Lincolnshire, IL 60069-0808. Subscription department: (800) 344-3046 or email: metropolismag@omeda.com. Subscriptions: 1 year: $32.95 USA, $52.95 Canada, $69.95 in all other countries. Copyright © 2023 by SANDOW DESIGN GROUP, LLC. All rights reserved. Printed in the USA. Material in this publication may not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. METROPOLIS is not responsible for the return of any unsolicited manuscripts or photographs. On the cover: Theaster Gates created the installation A Monument to Listening for Tom Lee Park in Memphis. Cover photo by Connor Ryan. HOSPITALITY Path of Kann 54 NEW TALENT New Traditional 62 INSIGHT Gathering with Purpose 66 NOTEWORTHY Andrés Jaque 120 p. 54 step outside 69 Making sense of the past, present, and future for outdoor spaces

70 A Brooklyn-based landscape architecture and design-build studio blends fabrication and urban placemaking to reframe public space.

Facing 76 Three separate stories in which municipalities are investing in public space improvements for the good of cities past, present, and future. Outdoor Enablers 80 Ten products that add fresh function outdoors. p. 40 p. 44 METROPOLIS 12 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

Greening the Future

Public

DISCOVER SAIL, SLIDING PANELS. DESIGN GIUSEPPE BAVUSO New York Flagship Store 102 Madison Ave New York, NY 10016 newyork@rimadesio.us +1 917 388 2650

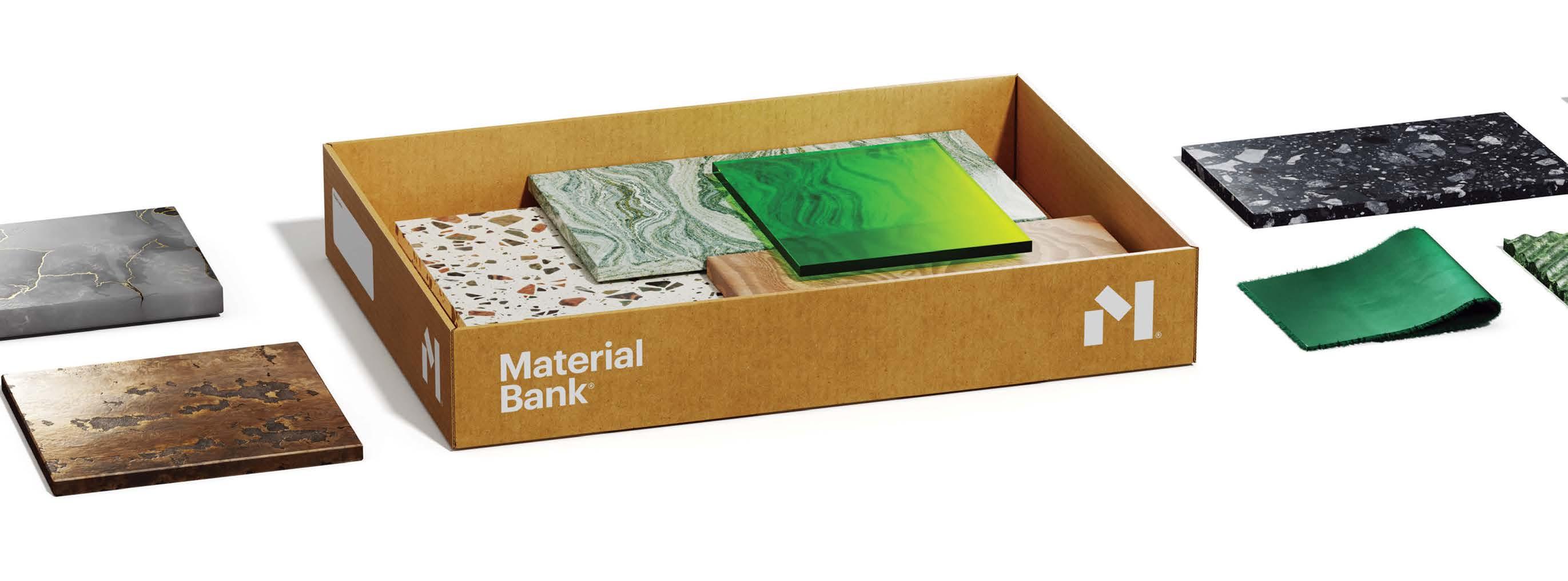

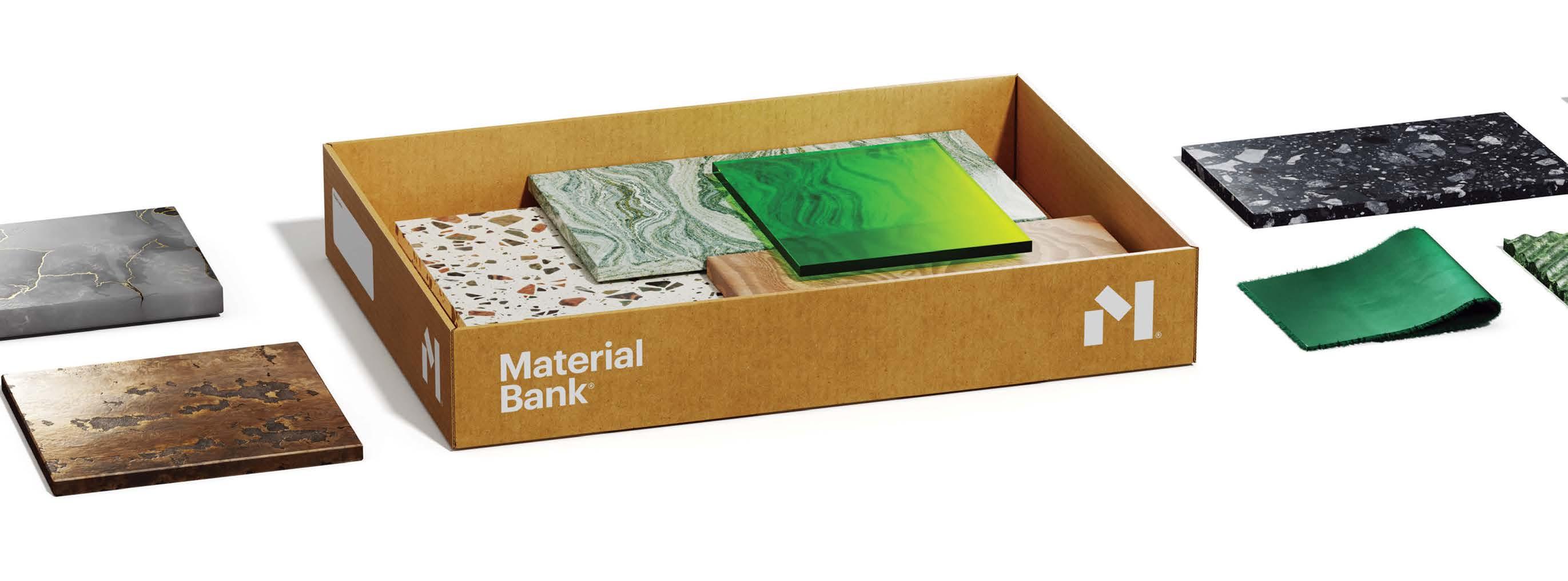

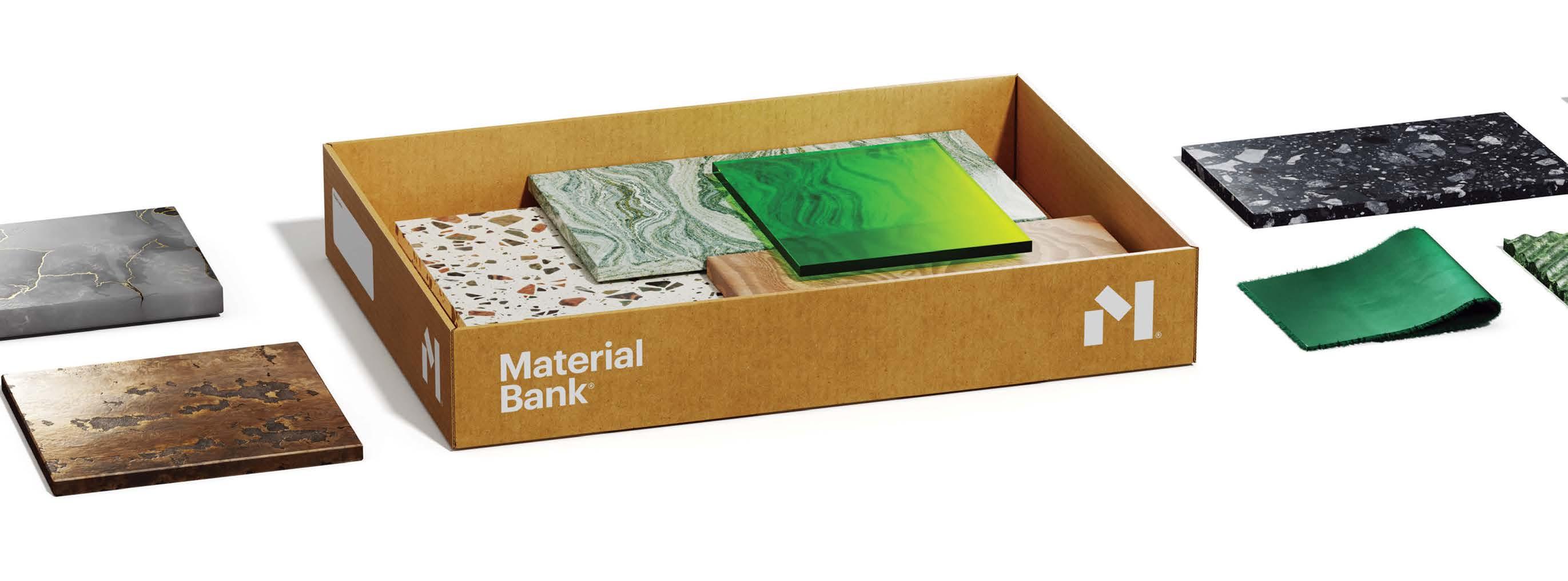

Textiles. Carpet. Paint. Wood. Leather. Wallcovering. Doors. Acoustical. Laminate. Resin.

Window Treatments. Quartz. Everything in one box.

500+ leading brands. One site. Order by midnight.

Samples tomorrow AM. Always FREE.

Flooring. Tile. Stone. Felt.

Marble. Ceiling. LVT. Film. Decking. Metal. Glass. Seating. Paneling. Terrazzo.

materialbank.com The most sustainable way to sample.

Brutalism Is Echoing in Contemporary Furnishings

Product designers are drawing on the historic architectural style to inform visionary seating, surfaces, and lighting.

One Willoughby Square Is a Welcome Relief to the Brooklyn Skyline

Designed by FXCollaborative, the new office building not only adds a unique silhouette to the borough’s skyline but has also achieved the highest LEED Interior rating in the United States.

Lina Ghotmeh Connects Space and Time Through Porosity

The Lebanese-born architect’s cultural projects play on spatial porosity to weave a thread between the past and the future.

Join

Register

(CLOCKWISE FROM TOP) PHOTO: IWAN BAAN, COURTESY SERPENTINE; COURTESY DAVID SUNDBERG/ESTO; COURTESY SANAYI313

METROPOLISMAG.COM More of your favorite Metropolis stories, online daily

discussions with industry leaders and experts on the most important topics of the day.

for free at metropolismag.com/ think-tank

METROPOLIS 16 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

A HARMONIOUS FUSION OF MUSIC & MINIMALISM.

KIMBALLINTERNATIONAL.COM

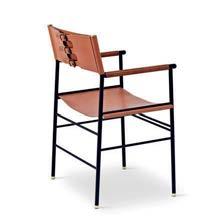

Designed by Brad Ascalon

KITHARA

EDITORIAL

EDITOR IN CHIEF Avinash Rajagopal

DESIGN DIRECTOR Tr avis M. Ward

DEPUTY EDITOR Kelly Beamon

EDITORIAL PROJECT MANAGER Laur en Volker

ASSOCIATE EDITOR J axson Stone

DESIGNER Rober t Pracek

COPY EDITOR Benjamin Spier

FACT CHECKER Anna Zappia

EDITORS AT LARGE Ver da Alexander, Sam Lubell

PUBLISHING

VICE PRESIDENT, PUBLISHER Carol Cisco

VICE PRESIDENT, MARKETING & EVENTS Tina Brennan

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Tamara Stout tstout@sando wdesign.com 917.449 .2845

ACCOUNT MANAGERS

Ellen Cook ecook@sando wdesign.com 423.580.8827

Gr egory Kammerer gkammer er@sandowdesign.com 646.824.4609

Colin Villone colin.villone@sando wdesign.com 917.216 .3690

Laury Kissane 770.791.1976

SENIOR MANAGER, MARKETING + EVENTS Kelly Allen kkriwko@sando wdesign.com

SENIOR MANAGER, DIGITAL CONTENT Ile ana Llorens

SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR Zoya Naqvi

METROPOLISMAG.COM

@metropolismag

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, FINANCE & OPERATIONS Lorri D’Amico

SENIOR MANAGER, MANUFACTURING + DISTRIBUTION Stacey Rigney

DIRECTOR, SPECIAL PROJECTS Jennifer Kimmerling

PARTNER SUCCESS MANAGER Olivia Couture

SANDOW DESIGN GROUP

CHAIRMAN Adam I. Sandow

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Erica Holborn

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER Michael Shavalier

CHIEF DESIGN OFFICER Cindy Allen

CHIEF SALES OFFICER Kate Kelly Smith

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT + DESIGN FUTURIST AJ Paron

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, STRATEGY Bobby Bonett

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, PARTNER + PROGRAM SUCCESS Tanya Suber

VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES Lisa Silver Faber

VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Laura Steele

SENIOR DIRECTOR, PODCASTS Sam Sager DIRECTOR, VIDEO Steven Wilsey

SANDOW DESIGN GROUP OPERATIONS

SENIOR DIRECTOR, STRATEGIC OPERATIONS Keith Clements

CONTROLLER Emily Kaitz

DIRECTOR, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Joshua Grunstra

METROPOLIS is a publication of SANDOW

3651 FAU Blvd. Boca Raton, FL 33431

info@metropolismag.com

917.934.2800

FOR SUBSCRIPTIONS OR SERVICE

800.344.3046

customerservice@metropolismagazine.net

SANDOW was founded by visionary entrepreneur Adam I. Sandow in 2003, with the goal of reinventing the traditional publishing model. Today, SANDOW powers the design, materials, and luxury industries through innovative content, tools, and integrated solutions. Its diverse portfolio of assets includes SANDOW DESIGN GROUP, a unique ecosystem of design media and services brands, including LUXE INTERIORS + DESIGN, INTERIOR DESIGN, METROPOLIS, and DESIGNTV by SANDOW; ThinkLab, a research and strategy firm; and content services brands, including The Agency by SANDOW, a full-scale digital marketing agency, The Studio by SANDOW, a video production studio, and SURROUND, a podcast network and production studio. SANDOW DESIGN GROUP is a key supporter and strategic partner to NYCxDESIGN, a not-for-profit organization committed to empowering and promoting the city’s diverse creative community. In 2019, Adam Sandow launched Material Bank, the world’s largest marketplace for searching, sampling, and specifying architecture, design, and construction materials.

METROPOLIS 18 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

THIS MAGAZINE IS RECYCLABLE. Please recycle when you’re done with it. We’re all in this together.

FORM & EXPRESSION. KIMBALLINTERNATIONAL.COM

SIGNATURE PRODUCTS THAT EFFORTLESSLY UNITE

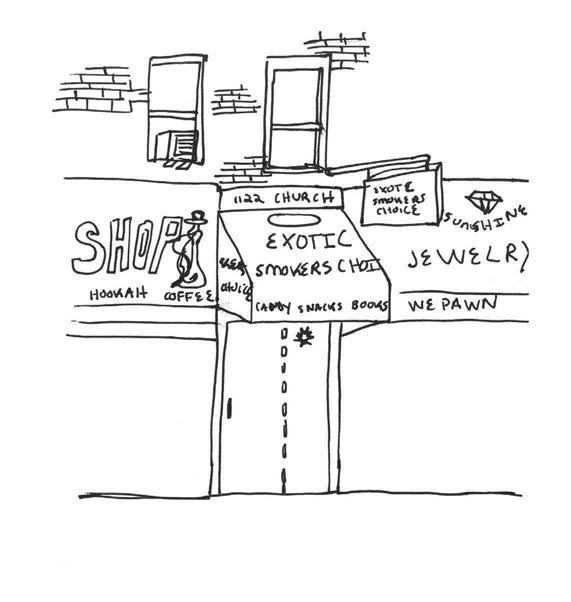

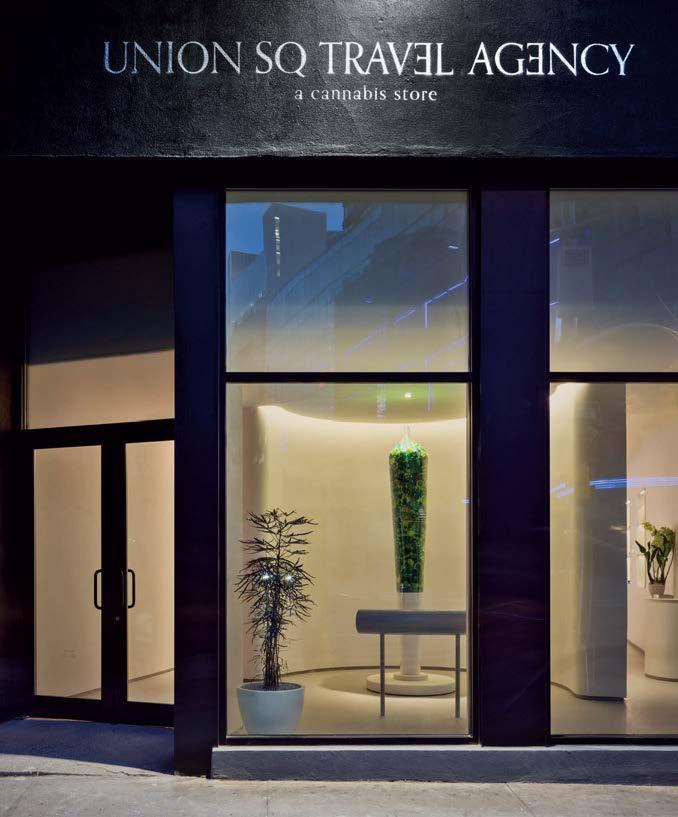

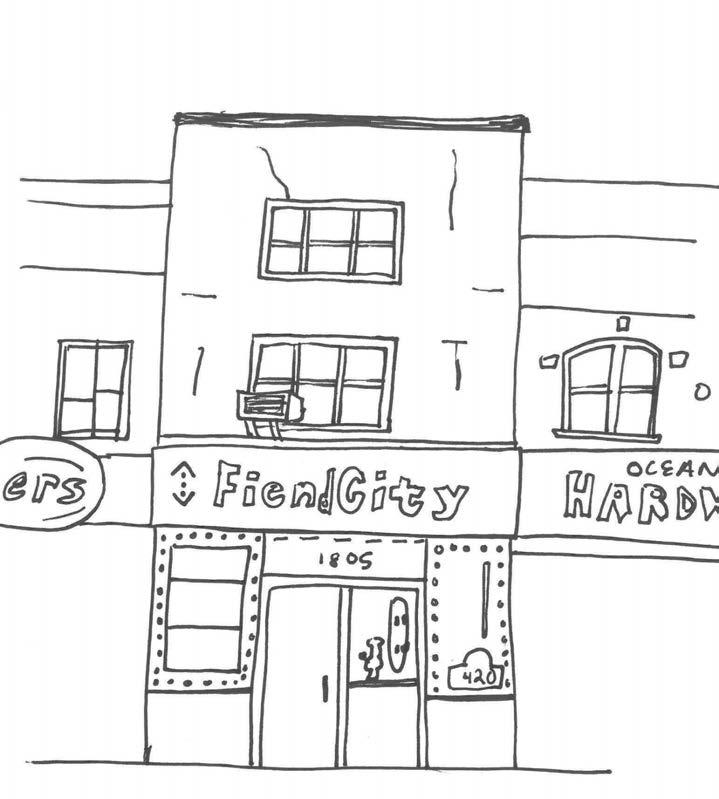

JAXSON STONE

As METROPOLIS’s associate editor, Jaxson Stone covers topics ranging from craft and identity to disability in architecture and interior design within the metaverse. Their writing has also appeared in The Architect’s Newspaper, HYPERALLERGIC, Architectural Digest, and Crafts, among others. When they are not writing and editing, they are teaching interior design history and theory at Parsons School of Design. When they are not teaching, they draw cartoons. Stone penned and illustrated this issue’s feature “High Design” (pg. 96) on the current state of cannabis culture and design in NYC. Follow their drawing practice on Instagram and Substack (@psychicinteriors).

SARAH ARCHER

Sarah Archer is the author of The Midcentury Kitchen, Midcentury Christmas, and Catland: The Soft Power of Cat Culture in Japan from Countryman Press. Her articles and reviews have appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Cut, Architectural Digest, NewYorker.com, and METROPOLIS, among other outlets. She also writes the Substack newsletter Cold War Correspondent Archer contributed this issue’s feature on the community-driven design of The Clay Studio’s new facility in Philadelphia (pg. 86).

STEPHEN ZACKS

Stephen Zacks is an advocacy journalist, architecture critic, urbanist, and project organizer based in New York City. A graduate of Michigan State University and the New School for Social Research with a bachelor’s degree in interdisciplinary humanities and a master’s in liberal studies, he serves as president of Amplifier Inc., a nongovernmental organization imagining the future of planetary governance. He is a regular contributor to Abitare, L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, The Architect’s Newspaper, Dwell, METROPOLIS, and Oculus For this issue, Zacks covered the new Tom Lee Park in Memphis, Tennessee for “Mixing It Up In Memphis” (pg. 108).

COURTESY THE CONTRIBUTORS METROPOLIS 20 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

CONTRIBUTORS

Take-Out

Set the Mood.

We believe that for design to be truly great, it must stand the test of time, be sustainably crafted, and proudly American made.

Take-Out : Go Configure

Designed by Rodrigo Torres

Landscape Forms | A Modern Craft Manufacturer

Designed to Divide

During a conversation with writer Stephen Zacks as he was reporting this month’s story on Tom Lee Park in Memphis (“Mixing It Up in Memphis,” p. 108), Carol Coletta, president and CEO of Memphis River Parks Partnership, pointed to some new research by economist Raj Chetty that appeared in the venerable journal Nature last year: “The ability to form weak tie networks with people wealthier than they are is the only thing that has an impact on the upward mobility of low-income people.”

The massive study, based on the social networks of 72.2 million Facebook users ages 25 to 44 years, yielded another insight that’s equally interesting: Rich people’s friendship networks are more likely to be made up of people who went to college with them than people who live in the same neighborhood. The inverse is true of most low-income individuals.

These are indicators that as income inequality in the United States continues to rise—as reported by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office—the social chasm between the haves and have-nots is likely to deepen. Even worse, if we don’t create more ways for people to encounter those unlike themselves, the chances to close that gap will get slimmer and slimmer.

So this month our annual North American Design issue provides a few snapshots of how design can either bridge or divide communities.

Tom Lee Park has the mission of bringing people together, as does The Clay Studio in Philadelphia, one of America’s most important art organizations (“Community Made in Clay,” p. 86). In The Clay Studio’s old building, “people who participated in different aspects of their programming didn’t always have the opportunity to meet by chance,” Sarah Archer reports. The finely crafted new structure, says

DIGSAU architect Mark Sanderson, is a place to “see the arts in action.”

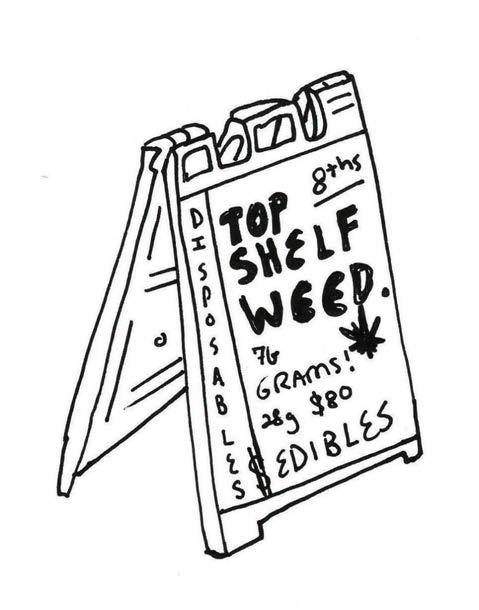

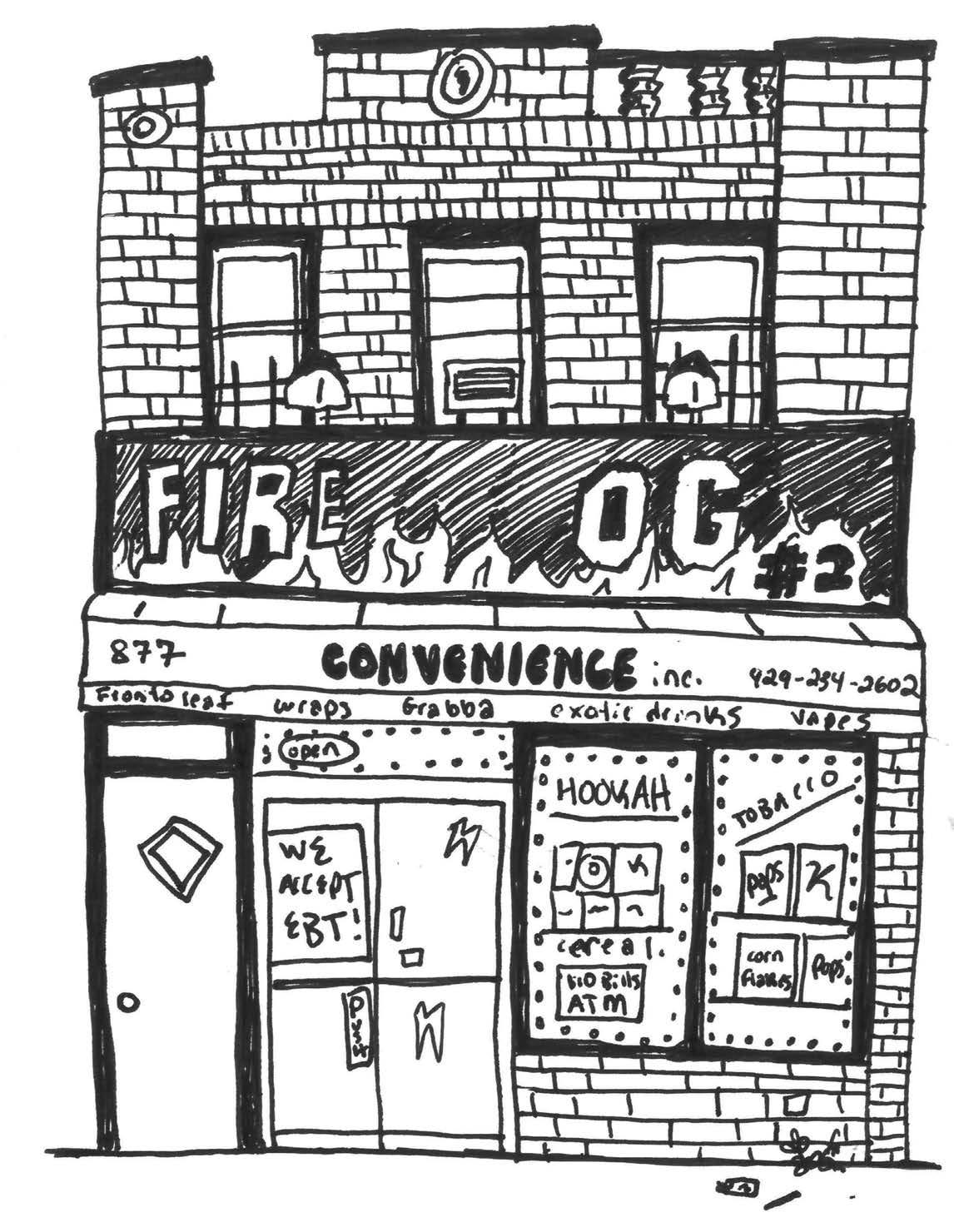

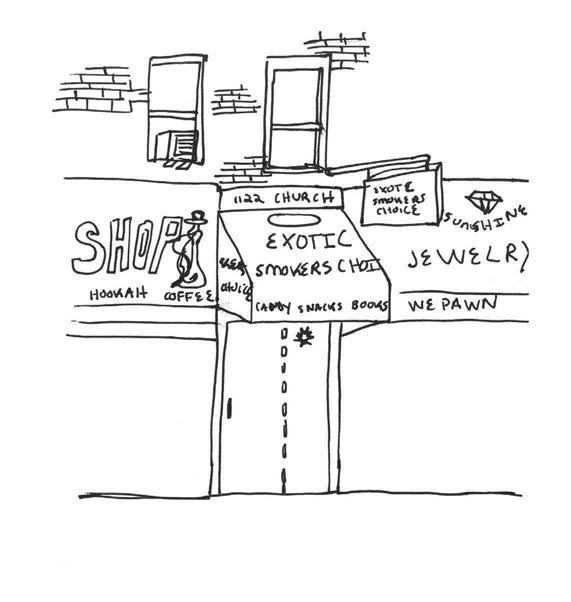

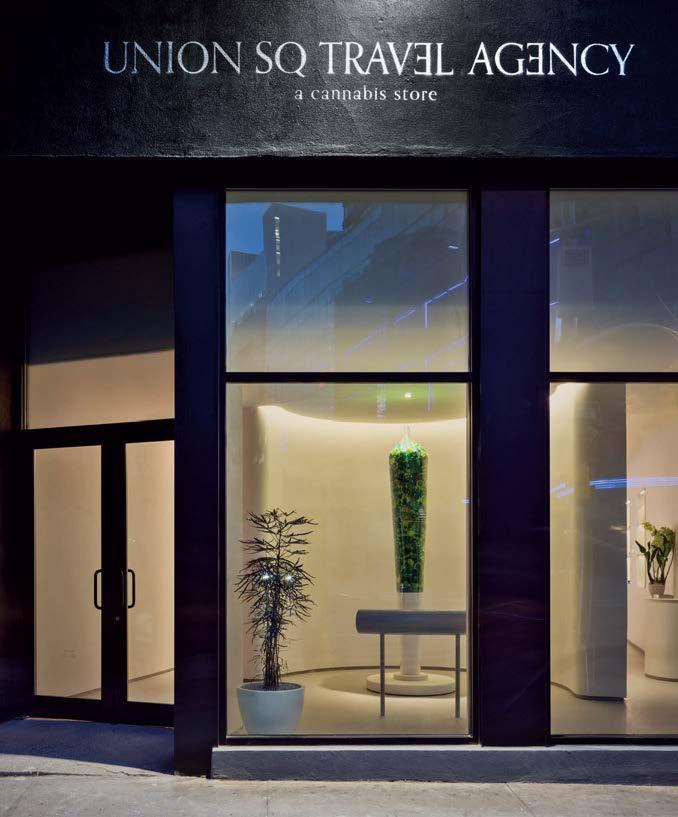

Less than a hundred miles east it’s a different story. In “High Design” (p. 96) , associate editor Jaxson Stone analyzes how the design of cannabis dispensaries in New York City reinforces class differences. The city’s Office of Cannabis Management has issued a 4 7-page guide for any outlet that wants to sell marijuana legally. One of the things it bans, Stone reports, is “any color which…has a saturation value greater than 60 percent.” The result of this kind of bureaucratic gatekeeping? There are only twelve licensed dispensaries operating in all of New York City; five of them in whitemajority neighborhoods. Let me remind you that between 2015 and 2018, Black and Hispanic New Yorkers were arrested on

Nearly 1,500 cannabis stores in New York City remain unlicensed because they run afoul of the city’s regulations, which include design mandates to avoid bold colors, nonstandard fonts, and any colloquial terms for marijuana.

low-level marijuana charges at eight and five times, respectively, the rate of White people, despite all three communities using marijuana at roughly the same rate.

What a blatant example of design being instrumentalized for segregation!

The truth is, decision makers at cities and organizations will always leverage designers’ work to further their agendas, and our best response would be to define and adhere to professional standards. The heads of our professional associations here in the United States are making inclusion a cornerstone of their leadership (“United We Stand,” p. 116), and rightly so. It’s more vital than ever before that architects and interior designers hold on to our core principle—we work to bring people together, not drive them apart. —Avinash Rajagopal, editor in chief

ILLUSTRATION BY JAXSON STONE

THIS ISSUE

IN

METROPOLIS 22 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

Spinneybeck | FilzFelt knows natural materials. With a legacy started five decades ago sourcing the finest full grain upholstery leather, the product line now includes a full range of natural materials including 100% wool felt, wood, and natural cork. These materials go it alone or are paired with acoustic substrates that up the ante of performance for the ceiling, walls, and dividing space.

For more of our story, please visit filzfelt.com/sustainability.

We’ve always been sustainable and always will be.

IRVINE | CHICAGO momentumacoustics.com DALLAS | NEW YORK

PINDROP: BENGAL IN WEATHERED OAK

TEXTILE: FLETCHERALABASTER, CODARAINFOREST

At All Scales

COURTESY © JAMES BRITTAIN

METROPOLIS SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023 25

The Montreal Insectarium’s Chromatic Collection is displayed in a cavernous domed hall that appears on its exterior to be a planted mound. Seventy-two frames hang on the shotcrete wall, displaying the museum’s extensive collection of preserved insects. The new museum was designed by architects Kuehn Malvezzi alongside Pelletier de Fontenay, Jodoin Lamarre Pratte architectes, and atelier le balto.

SPECTRUM

An essential survey of architecture and design today

After winning an international competition in 2014, Berlin-based architects Kuehn Malvezzi and Montreal firms Pelletier de Fontenay and Jodoin Lamarre Pratte architectes redesigned the largest insect museum in North America. Replacing the former Insectarium (opened in 1990), the new building opened in April 2022.

ARCHITECTURE Museum Metamorphosis

Bugs aren’t for everyone. I, for one, have experienced intense periods of katsaridaphobia (fear of cockroaches). So it’s a bit surprising that the most fun I had during a recent trip to Montreal was at the city’s Insectarium, where I looked into the eyes of the largest cockroach I’d ever seen. Designed by Berlin-based architects Kuehn Malvezzi and local firms Pelletier de Fontenay and Jodoin Lamarre Pratte architectes, the newly redesigned 38,750-square-foot Insectarium sets out to “redefine our relationship with insects.” And with insects representing 85 percent of animal diversity, perhaps it’s about time.

While the giant cockroach was behind a glass barrier (thank God), other spaces throughout the building allow visitors to get up close and personal with the creatures, and even include immersive sensory experiences that simulate entomophilic perception, such as alcoves that mimic the tight passageways cockroaches can crawl through and the pixelated vision of a fly. With 3,000 preserved insect specimens, 175 species of live insects, and 3,000 plant specimens, it’s the largest insect museum in North America.

To experience the building is to walk a tightly choreographed route that begins in an outdoor pollinator garden and gradually introduces visitors to indoor galleries, creative workshops, and a majestic greenhouse where they can experience up to 80 species of butterflies, year-round, in a lush, barrier-free environment.

One of the most impressive features is the Chromatic Collection—a wall of preserved insects arranged by hue. The collection is housed in a cavernous domed hall that resembles a

planted mound and envelops the viewer in a shotcrete interior that feels like an underground labyrinth. Visible from the exterior, the dome emerges from the surrounding botanical garden landscape and, a few years from now, will be covered in plant life.

Once visitors pass through the dark domed hall, they experience another shift in perception as they begin a slow ascent into the large, sunlit greenhouse, which features a gradually inclining path through a range of microclimates. While the building’s positioning makes the most of natural light, advanced mechanical systems allow much of the heat from the greenhouse to be redistributed to the rest of the building. A range of additional systems— such as textile shades, motorized louvers, geothermal wells, roof water recovery, and the use of local, VOC-free materials—are helping the building meet its LEED Gold certification goals.

Throughout the space, the architects wanted to “challenge the notion of biophilia being anthropocentric” and reveal that the history of natural history museums can’t be separated from the history of environmental exploitation. For Wilfried Kuehn, it’s about power. In a conversation published by the museum with the Insectarium’s director, Maxim Larrivée, Kuehn said: “[As architects] it is our task to advocate for the ones underrepresented or those not in charge. This led us to the question of the insect as part of the spatial experience and to make sure that they have an environment that does not violate them and does not treat them as objects.” I left the museum humbled and in awe, almost wanting to give back some power to the cockroaches. —Jaxson Stone

COURTESY © JAMES BRITTAIN

METROPOLIS 26 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

Roda

by Joana Bover

The Roda Collection is characterized by its large, cylindrical, ring-shaped shade. Its inner contour is surrounded by an aluminum ring housing a continuous circle of LEDs, emitting a uniform, filtered light.

The warmth of the ribbon is highlighted by the dark ring outlining the perimeter, making these fixtures particularly cozy and lightweight, because despite their large volume, they seem weightless.

| +1 (404) 924 2342

www.boverusa.com

RESIDENTIAL On a Mission

Where there once were two parking lots in San Francisco’s Mission District, there is a nine-story, 127-unit affordable housing development overlooking a lively public park. The two look as though they were designed together, but in fact, In Chan Kaajal Park was fully designed before Casa Adelante 2060 Folsom went out for proposals. The city’s housing department had assumed that the new housing would have a blank party wall facing the park, with a narrow fire easement between the two, but Mithun, the firm responsible for the housing component, made sure that the complex took full advantage of its sunny southern exposure and park views. The firm designed a wide paseo and successfully lobbied the park designers to include two gates into the park from the walkway.

Beyond the obvious linkages, the design creates more subtle connections. A number of community nonprofit organizations occupy the building’s ground-level spaces along the paseo, and the building also provides the city’s first all-gender public restroom for park visitors.

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of the exterior is a large mural on the north facade by local muralist Jessica Sabogal, created as an homage to artist and activist Yolanda López, highlighting the historical struggle for social justice in the Bay Area. The chartreuse hue that accents the building’s exterior was color-matched to the spring buds of the silk floss trees growing in

the park, and the light filtering into the building’s open-air corridors through perforated metal screens mimics the dappled light coming through a tree canopy. The building’s private courtyard is planted with native sycamore trees, which are the tallest trees that would have grown in the historical marshlands. “They are a representation of what was here before,” says project architect Mary Telling at Mithun.

In addition to embracing the outdoors, the building works hard to be a model of sustainability. The city’s first all-electric multifamily housing development, Casa Adelante 2060 Folsom is also extremely energy efficient. With a rooftop solar array that supplies enough power for the common areas, the building has a net EUI (energy use intensity) of 14.9 kBTU/sf/year, outperforming its Architecture 2030 design target. According to Mithun’s Anne Torney, “It’s an amazing piece of cultural infrastructure for combating climate change and advancing social and racial equity.” —Lydia Lee

COUNTERCLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: COURTESY BRUCE DAMONTE (2); COURTESY TOOLBOX VIDEO SPECTRUM

Overlooking one of San Francisco’s newest public parks, Mithun’s Casa Adelante 2060 Folsom features 127 affordable housing units, a green open-air courtyard, and a community roof deck. It’s also the city’s first all-electric multifamily housing development.

METROPOLIS 28 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

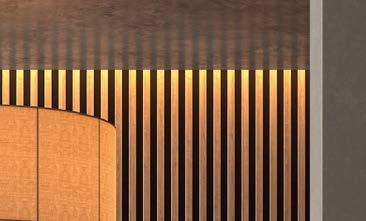

This Isn’t Wood. This is Fortina.

Available in over 100+ wood and metal finishes and 50+ profiles for interior and exterior applications. Available with integral lighting as well as larger, up to 2" x 12" profiles. Get it fast with our new QuickShip program.

Available in over 100+ wood and metal finishes and 50+ for interior and exterior Available with as well as up to 2" x 12" Get it fast with our new program.

www.BNind.com 800.350.4127 Fortina

Fortina is a remarkable architectural system that looks and feels like real wood, but is made with aluminum and a hyper-realistic non-PVC surface. F OR T I N A Q U I C K SH I P Getit fast. © B+N Industries Inc.

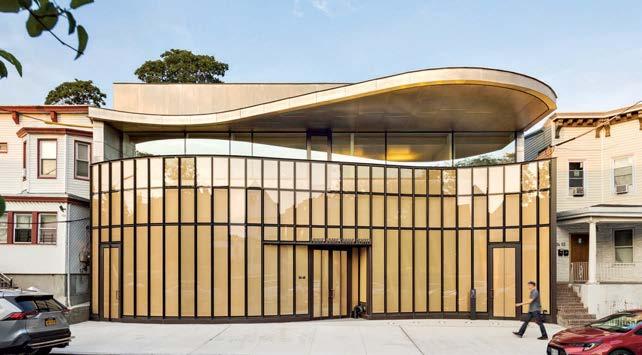

MUSEUM All That Jazz

In 1943 the great American jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong and his wife, Lucille, settled into what would be the last residence they shared: a two-story house in the New York neighborhood of Corona, Queens. As one of the world’s most famous musicians, Armstrong could have lived anywhere but he made 107th Street his home, and practiced there every day until he died in 1971.

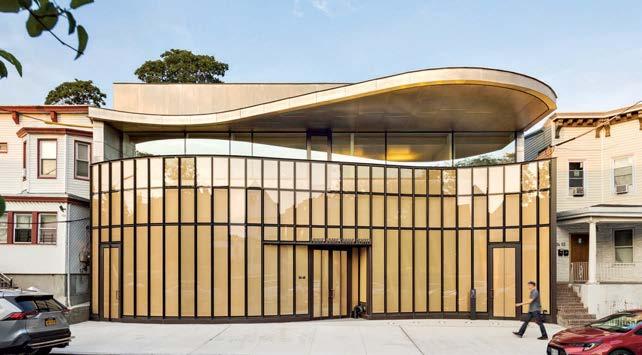

That house became a National and New York Historic Landmark, thanks to the efforts of Lucille. And thanks to Caples Jefferson Architects, a new, 14,000-square-foot visitor center opened this summer across the street, forming a kind of institutional duet. “Armstrong’s music didn’t come out of some fancy pla ce,” says principal Sara Caples. “It came out of a deep tradition, a brilliant tradition, but very much part of a working person’s tradition.” The new Louis Armstrong Center also eschews fanciful gestures while staying in the pocket of the block. Its forecourt welcomes in the neighborhood, while its faceted facade embeds metal fins like music staffs even as the glazing appears to swing.

Inside, exhibition space offers stages for some of the center’s 60,000-piece collection of recordings, mouthpieces, scrapbooks, and reel-to-reel tapes (whose shapes inform display tables) in boxes Armstrong hand-decorated. More archives are stored below, and even more of them above, along with offices overlooking a flowering green roof.

Beneath beats the heart of the center. Faceted mahog any and perforated acoustic panels—some upholstered in what Caples calls the red of “sexy, joyous nightclubbing”—give the 75-seat sound room its shape. Its placement is intentional. “We wanted the archives to kind of just sandwich [the club],” says firm cofounder Everardo Jefferson. This way the concerts are “all built on the archives. They affect the music itself.”

The spotlit glow of Satchmo’s brass trumpet echoes in finishes throughout the center, from the woven mesh within the facade’s double glazing to the interior columns’ incipits. They form a familiar refrain as you wander through Caples Jefferson’s architectural riffs. “The spaces are very distinct experiences,” says Caples. “When you listen to a piece by Louis, it’s just like an adventure.” Fittingly, each pops. —Jesse

Dorris

© ALBERT VECERKA/ESTO SPECTRUM

METROPOLIS 30 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

This June, the neighborhood of Corona, Queens, gave a warm welcome to the new Louis Armstrong Center. Located across the street from the Louis Armstrong House Museum and designed by Caples Jefferson Architects, the center showcases rotating exhibitions, a 60,000-piece archive, and a performance venue.

Lapala hand-woven

Lievore Altherr Molina & Atrivm dining table . Manel Molina —— Photographer: Meritxell Arjalaguer © Expormim —— (212) 204-8572 usa@expormim.com www.expormim.com

chair.

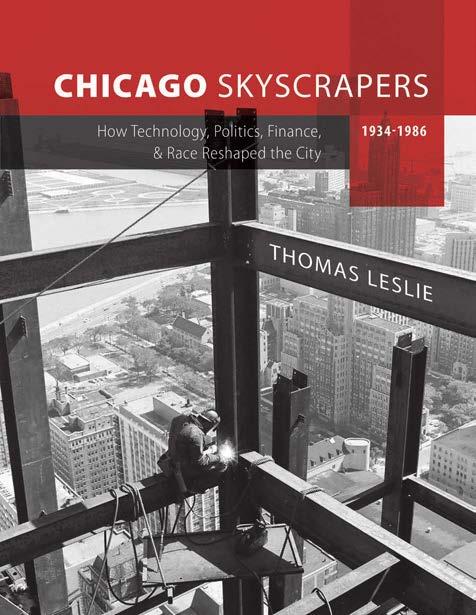

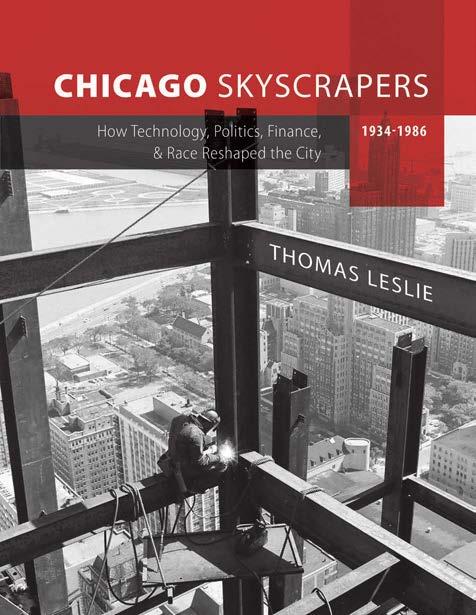

BOOKS Too Tall to Fail

Chicago Skyscrapers 1934–1986: How Technology, Politics, Finance, and Race Reshaped the City

By Thomas Leslie University of Illinois Press, 2023

By Thomas Leslie University of Illinois Press, 2023

354

pp., $44.95

Chicago Skyscrapers 1934–1986 traces the political economy of the Modern skyscraper backward from the city it originated in, illustrating how high-rises were used by savvy public- and private-sector actors to concentrate both wealth and poverty, for the benefit of those with power and money to remake cities. Leslie’s book inducts the disastrous Chicago Housing Authority high-rises into the city’s skyscraper canon, with the implication that their failure is as canonically American as the success of the Sears and Hancock Towers, which are also present alongside the rest of Chicago’s 20th-century steel-andglass titans. With granular observation of how new building technology (fluorescent lights, air-conditioning, curtain walls) aided this ascent, and how public policy carefully controlled who was allowed into which skyline perch, Chicago Skyscrapers 1934–1986 situates architecture as a clumsy yet still often graceful mediation between ambition, imagination, and economics stripped of saintly airs of neutrality. —Zach Mortice

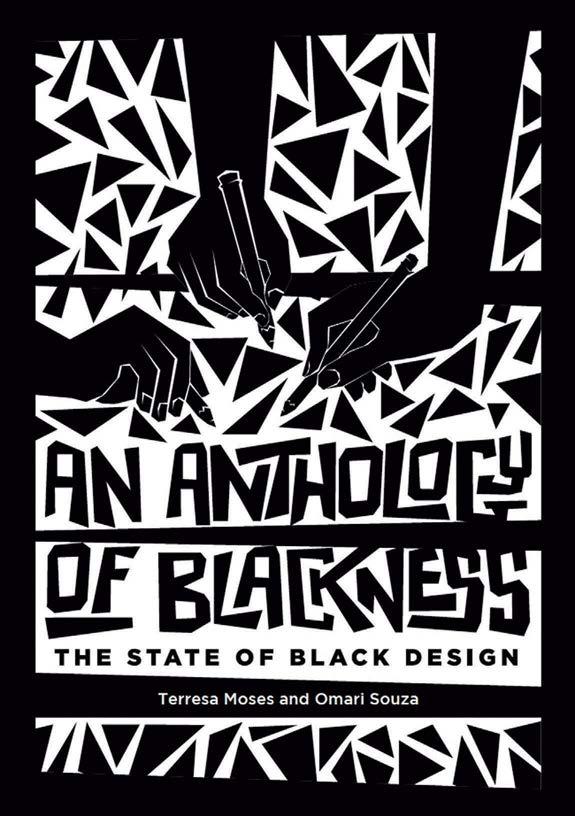

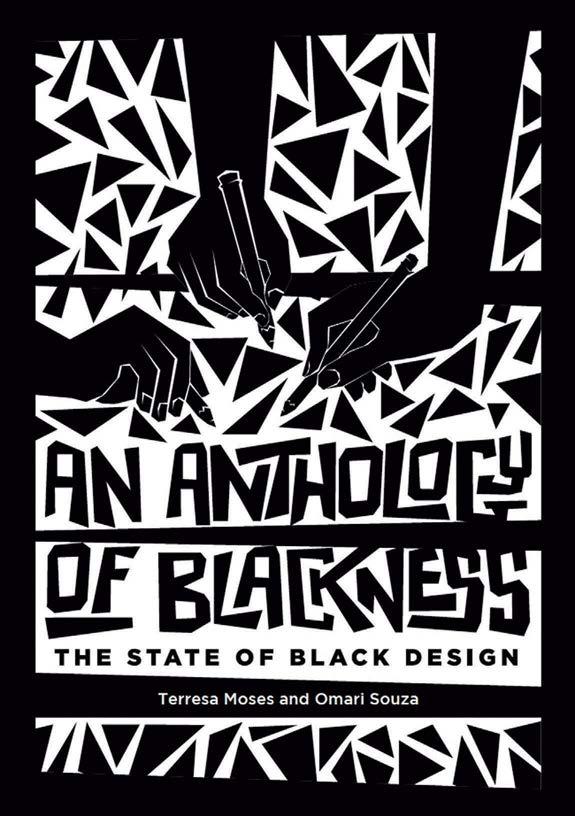

Radical Reformers

An Anthology of Blackness: The State of Black Design

Edited by Terresa Moses and Omari Souza/ foreword by Elizabeth (Dori) Tunstall MIT Press, 2023

Edited by Terresa Moses and Omari Souza/ foreword by Elizabeth (Dori) Tunstall MIT Press, 2023

264

pp., $32.95

This collection of essays, opinion pieces, case studies, and visual narratives looks toward the horizon of an anti-racist design industry. Divided into three sections that focus on the design industry itself, surrounding pedagogy, and activism, the book analyzes how Black graphic designers—from the early 20th century to today— have called for social justice while exploring the legacy of Eurocentric beauty standards, especially hair. There’s a brisk survey of African histories of

making in the pedagogy section, as well as an investigation of why Black students don’t enroll in design electives. The portion on the design industry offers technocratic and heartfelt suggestions: for example, using videogames to attract Black youth to design, and improving practices of arts and cultural stewardship. With intersectional perspectives on race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and ability, the anthology reminds the reader: “Design is not a master’s tool.” —Z.M.

COURTESY THE PUBLISHERS

SPECTRUM METROPOLIS 32 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

Proxy Collection

Create supportive spaces with the Proxy Collection. PVC-free, this non-vinyl resilient plank and tile flooring offers comforting wood and stone visuals in warm, soothing neutrals that support a sense of wellbeing. Declare Red List Free and 105% carbon offset cradle to gate, Proxy helps create a better environment, indoors and out. manningtoncommercial.com

Proxy Collection I Wood Andara Oak PRX204

Proxy Collection I Wood Andara Oak PRX204

RETAIL Carving Block

In London and Paris, the indoor shopping arcade is a beloved urban form. Now, for different reasons, the covered commercial passageway is being reimagined in the city of Los Angeles. Local architecture firm Formation Association transformed a nearly century-old masonry building into Atwater Canyon, a multi-tenant retail and restaurant complex organized around a welcoming pedestrian passageway that deftly merges indoor and outdoor spaces.

Cofounder and design director John Chan and his team introduced a series of wide exterior and interior storefront arched openings and earthy materials, such as hand-raked plaster walls in a muted dusty rose palette, to integrate with preexisting details. The building’s three bays, a parapet wall with eyelet openings, and decorative ceramic tile remain familiar fixtures to residents. Subtle yet forceful landscape elements by David Godshall of Terremoto include rooftop succulent plantings. Formation Association designed trellises to support native California morning glory vines. Along with branding and signage by graphic designer Jessica Fleischmann of

Still Room, these valuable contributions come from local collaborators who are attuned to the community context.

For Chan, the building’s materiality and construction evoke a meeting of “Gordon Matta-Clark openings” with Japanese joinery. The designers highlighted exposed brick walls, studs, joists, and rafters from the original building.

Los Angeles’s Atwater Village neighborhood is characterized by long blocks and a scant tree canopy. Atwater Canyon

Los Angeles–based architecture firm Formation Association has transformed a former market in Atwater Village into an indoor/outdoor retail and restaurant complex, oriented on an open-air pedestrian passageway.

aims to provide a pedestrian-friendly experience by connecting the property’s street-facing facade on Glendale Boulevard to municipal parking lots in the rear. While European cities may have needed arcades to protect against precipitation, Angelenos benefit from a respite from L.A.’s unrelenting sunshine. Yet the project eagerly embraces it too. Chan notes, “You see the edge of Griffith Park raking across that opening, which is really magic when the sun is going down.” —Jessica Ritz

COURTESY PAUL VU

SPECTRUM

METROPOLIS 34 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

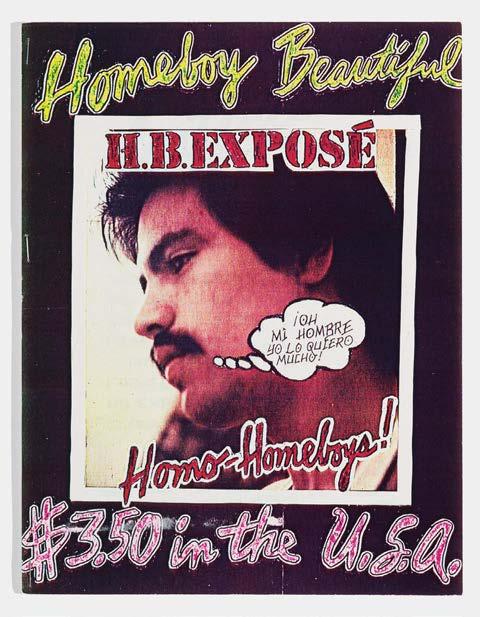

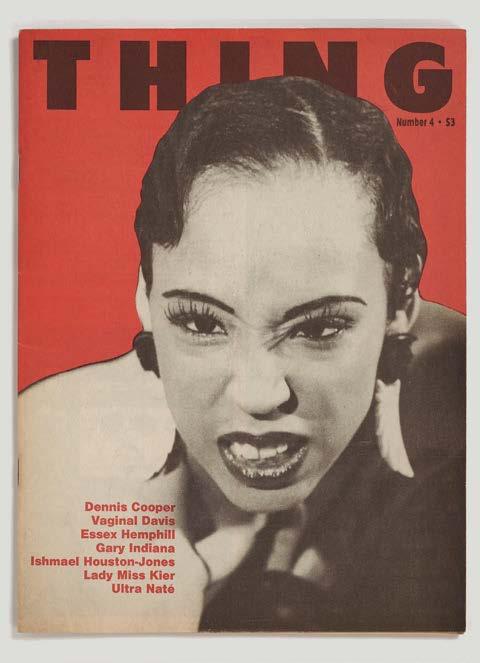

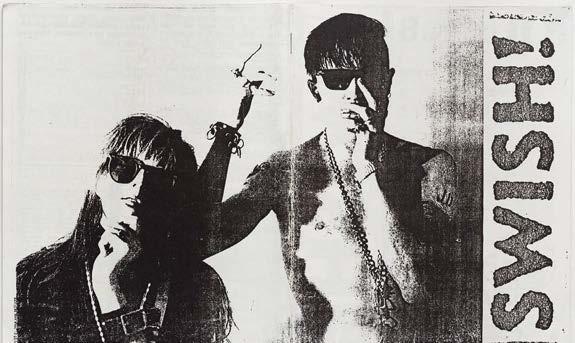

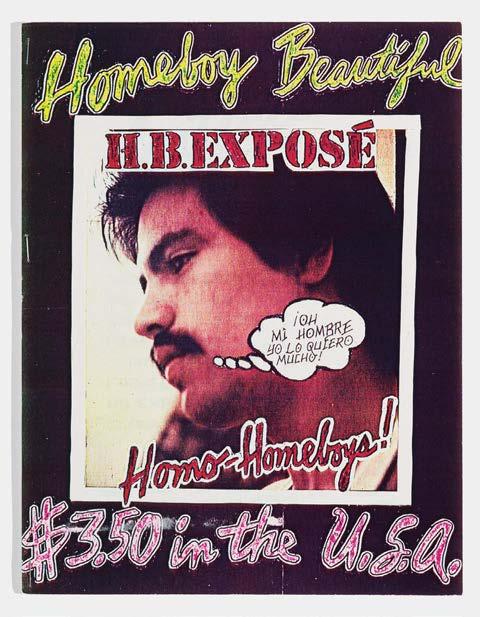

EXHIBITION Arti–Zines

Before the advent of augmented reality or the digital town square, people on the margins of society communed between the pages of zines establishing safer spaces, constructing alternative realities, and voicing dissent. These distinctly visual, often self-published booklets proliferated during the late 20th century using newly accessible technologies. But until now, few have celebrated the significance of these cultural ephemera.

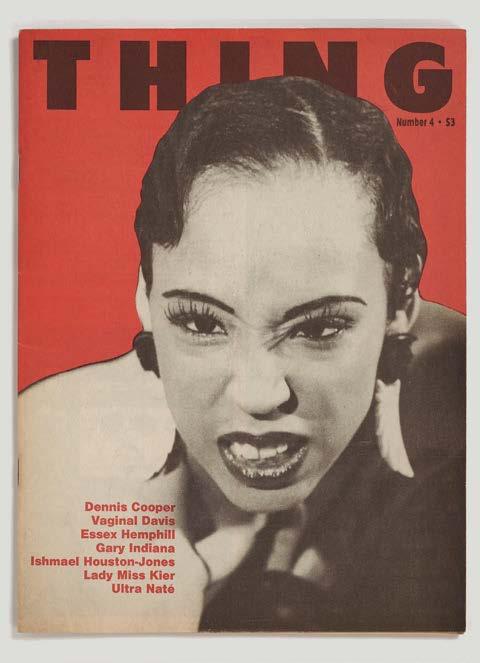

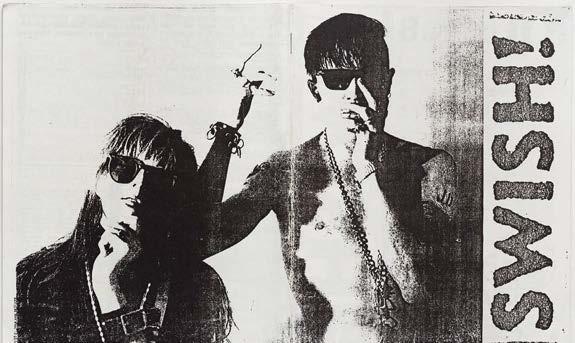

Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines—on view at the Brooklyn Museum November 17 through March 31, 2024—is the first show dedicated to such works by North American artists, examining how the aesthetic practice evolved over the past half century while contextualizing it within the lineage of art history.

Composed of some 800 artifacts, Copy Machine Manifestos’ monumental undertaking is organized by Branden W. Joseph, Frank Gallipoli Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at Columbia University, and Drew Sawyer, Sondra Gilman Curator of Photography at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It will also feature an accompanying catalog of the same name.

The robust survey of early mailers, poster pages, shape-shifting inserts, and unfurled printed matter—highlighting a sliver of the canon—is roughly organized by chronology and further parsed by social networks from the 1970s through today. Presented as genres, narratives include the Correspondence Scene, Punk Explosion, Queer and Feminist Undergrounds, Subcultural Topologies, Critical Promiscuity, and A Continuing Legacy. Much of the material honors authors, artisans, and outliers who drew inspiration from their subcultures to challenge institutions.

Works like Jordan Nassar’s saddle-stitched We Were Here

First are finished with colored twine showcasing their haptic nature, while editor Linda Simpson’s My Comrade subverts the gatekeeping of traditional distribution channels with its xeroxed cut-and-paste composition.

Whereas contemporary digital media are often an exercise in—and sometimes victim of—man’s own hubris, this form of slow journalism still captivates audiences. “It is far from nostalgic or outmoded,” says Joseph. “The photocopied and printed zine remains a vibrant means of artistic expression.” Joseph P. Sgambati III

COURTESY THE ARTISTS SPECTRUM

METROPOLIS 36 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

The Brooklyn Museum’s upcoming exhibition Copy Machine Manifestos offers visitors a glimpse into the world of artist-made zines from the 1970s until today. The works on view will showcase a selection of underground zines from various queer subcultures including (clockwise from top) J.D.s, a queer punk zine; Thing, a magazine that documented Black queer nightlife in Chicago; and Homeboy Beautiful, a queer Chicano zine.

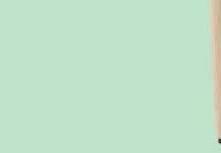

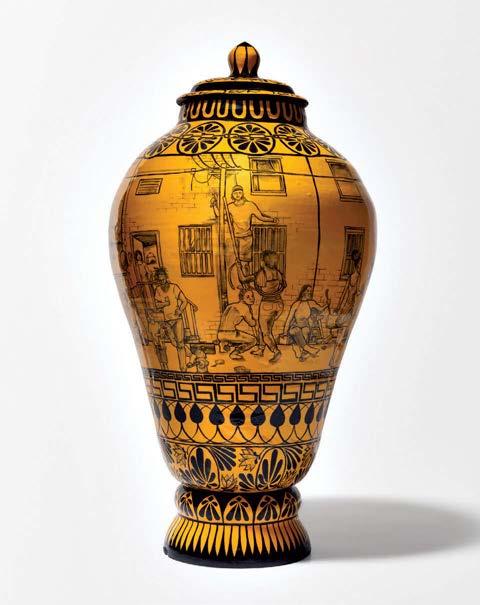

TRANSPARENCY Bottled Up

KFI Studios embraces PET felt in its new collection, securing a seat among the most eco-friendly chair options.

By Kelly Beamon

By Kelly Beamon

01

PLASTIC WASTE DIVERSION

Vale’s main component, the PET felt shell, is made of plastic diverted from landfills to the tune of roughly three pounds per side chair up to about eight pounds per lounge and ottoman combined.

02

CLEAN CHEMISTRY

It feels like traditional felt, but PET felt has the same properties as plastic—easy to clean without dangerous off-gassing.

03

BIFMA-TESTED

Like KFI’s other furniture, seats are tested to perform: Chairs and stools meet ANSI/ BIFMA X5.4, and lounge chairs meet the X5.11 Large Occupant standard.

04

DOMESTIC SUPPLY

To cut transportation pollution tied to product deliveries, the Louisville, Kentucky, plant is located within a day’s drive of 65 percent of the United States.

05

INDOOR ADVANTAGE GOLD

Vale is certified at the Gold level for indoor air quality by SCS Global Services.

06

CIVIC IMPACT

VALE COLLECTION

Billed as the first of its kind from a U.S. company, Vale’s commercial-grade furniture (side chairs, armchairs, lounges, and stools) features a seat made of PET felt, a material made from recycled water bottles. That is earning it industry praise, including a 2023 MetropolisLikes NeoCon award. Designed by London-based studio Layer, the collection introduces the U.S. furniture market to a manufacturing technique pioneered at European companies such as Vepa and De Vorm. Here are seven reasons to consider KFI’s stateside version:

By participating in IIDA’s Zero Landfill upcycling program, the manufacturer collected discontinued materials from dealers for use by Louisville and Southern Indiana artists, diverting 1,500 pounds from landfills in 2019 alone.

07

ABUNDANT FEEDSTOCK

There’s an abundance of plastic waste for PET felt manufacturers to draw from.

COURTESY © KFI STUDIOS

METROPOLIS 38 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

FOCUS Cup and Ball

The Bilboquet table lamp is radical in its simplicity and designed for disassembly.

By Avinash Rajagopal

In most desk lamps, the critical design detail is the joint that allows users to direct and hold the beam where it’s needed. The iconic British Anglepoise lamp does this through a system of springs, and Richard Sapper’s ingenious 1972 Tizio lamp uses a system of counterbalancing weights. For Flos’s Bilboquet lamp, London-based designer Philippe Malouin chose a ball-andsocket joint—like the one in your shoulder— and this opened up new possibilities for both function and sustainability.

“It’s simple in appearance but full of personality,” Malouin says. The movable cylindrical arm that contains the LED bulb is

magnetically attached to a shining ball that in turn sits in a hollow cylinder. The cable runs straight into the movable arm, meaning the light can be not only directed but also completely detached from the base. “Bilboquet shines light where it is needed,” Malouin says.

This almost childlike simplicity—the lamp is named for a traditional French toy that is widely known as cup and ball—belies the sensitive engineering that makes Bilboquet durable and sustainable. The entire lamp can be disassembled, and every part can be repaired and replaced. Even the LED bulb has a standard dimension and is detachable

British-Canadian designer Philippe Malouin set up his London studio in 2008 and has since designed for brands like Hem, Ishinomaki, Iittala, De Sede, SCP, Established & Sons, and Marsotto Edizioni. His artistic work is represented by the Salon 94 gallery in New York City as well as the Breeder gallery in Athens. For the Bilboquet lamp (below), he collaborated closely with Francesco Rodrigues and Andrea Gregis from Flos’s R&D department.

from the fixture, making it easy to replace or upgrade as lighting technologies change. The iron ball, which is the heart of the design, is finished with a surface treatment called physical vapor deposition rather than the typical anticorrosive galvanic coating. Both the metal cylinder that holds the LED and the bioplastic base come in the Gen Z– and millennial-friendly colors of Linen, Tomato, and Sage—hues that are intrinsic to the material, and not the result of painting or coating.

Bilboquet represents a new generation of lighting—infinitely versatile in use, tailored to the tastes of our times, and prepared for a planet-friendlier future. M

PORTRAIT COURTESY TIMO JUNTTILA; IMAGE COURTESY FLOS

METROPOLIS 40 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

SHAPING NATURE

Flagship Store, Soho 152 Wooster St, New York Flagship Store, San Francisco 111 Rhode Island St #3, San Francisco Flagship Store, Midtown East 145 East 57th Street, New York

Designed by Hans J. Wegner in 1965 as part of a wider series of furniture, the CH45 Rocking Chair highlights Wegner’s appreciation of the functional principles of Danish Modern. Featuring his signature envelope woven paper cord seat and shaped in a solid, FSCTM-certified oak, Wegner merged a careful balance of poise and elegance with a Nordic aesthetic.

CH45 Rocking Chair Hans J. Wegner 1965 CARLHANSEN.COM FSCC135991

PRODUCTS Living Legacies

Whether nascent or well established, brands innovate to expand on their product heritage.

By Joseph P. Sgambati III

The latest design solutions across product categories are tapping into nostalgia to build on existing brand recognition. KI, maker of the original metal folding chair, expanded a seating collection by including a new contemporary base, while Maharam turned to a 20-year collaboration with Paul Smith to release new textiles made partly from postconsumer material. HBF (shown right) owes the most playful pattern in its new Reunion Collection to a childhood memory of vice president of design and creative direction Mary Jo Miller. Review similarly inspired designs on the opposite page.

SCS

HBF TEXTILES hbftextiles.com

01 LAWN CHAIR

Part of the aptly named Reunion Collection, this plaid by Mary Jo Miller recalls the woven strap detail on aluminum lawn chairs used by her mother and friends in the 1960s. Miller scaled up the plaid to mimic the unique effect. This and the collection’s four other patterns (Ms. Quilty 2.0, Comfort Zone, Tête-à-tête, and Gather) are PFAS-free, and certified

Indoor Advantage Gold.

01 METROPOLIS 42

02 LIMELITE SEATING

KI expands its heritage with an alteration to its typical stacking chair. This cohesive family comprises nine frame styles, up to three arm configurations, and copious colorways for the seat and base, which now includes a wood leg option.

KI ki.com

03 BRISA

Ultrafabrics’ rerelease of the Brisa performance fabric adds a recycled back cloth made of 8.3 plastic bottles per yard in a diversified range of 54 shades—nine of which are new. Indoor applications range from upholstery to vertical and horizontal paneling.

ULTRAFABRICS ultrafabricsinc.com

04 V COLLECTION

Biophilic design is made more accessible with the expansion of Havwoods’ V Collection, now including maple and black American walnut, as well as a new XL width option for four other finishes to accommodate varied design languages.

HAVWOODS havwoods.com

05 METERED STRIPE

While based on a classic design, this fresh fabric consists of two different scales in a densely gridded pattern. The result is a dimensional surface of assorted stripes reminiscent of needlepoint.

MAHARAM maharam.com

06 DASH AND TEXTURE

The Tessellate Collection, composed of 60 percent PET, adds two new wall solutions with the Dash and Texture acoustic tiles. Both feature tactile surface patterns that are visually engaging while providing added surface areas for sound control.

KIREI kireiusa.com

COURTESY THE MANUFACTURERS

04 02 03 05 06 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023 43

SUSTAINABILITY Water Filter

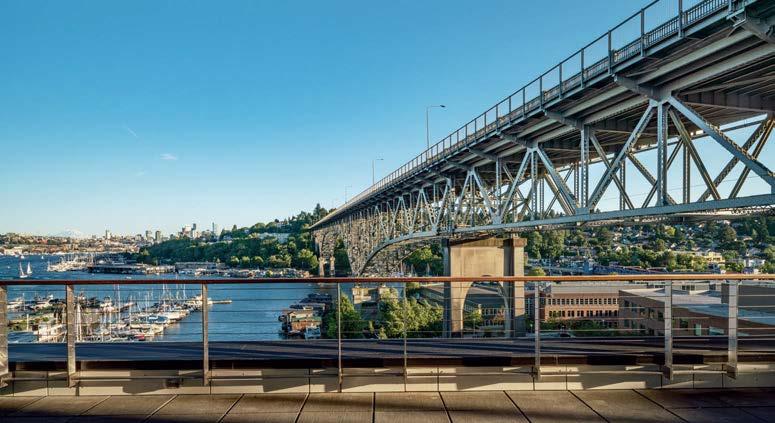

An office building in Seattle takes on ecological responsibilities that reach far beyond its site.

By Sam Lubell

By Sam Lubell

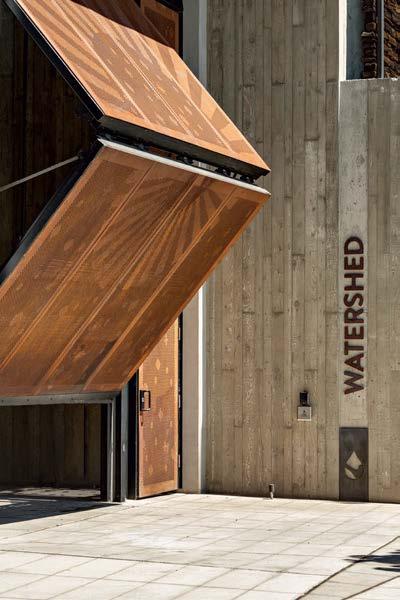

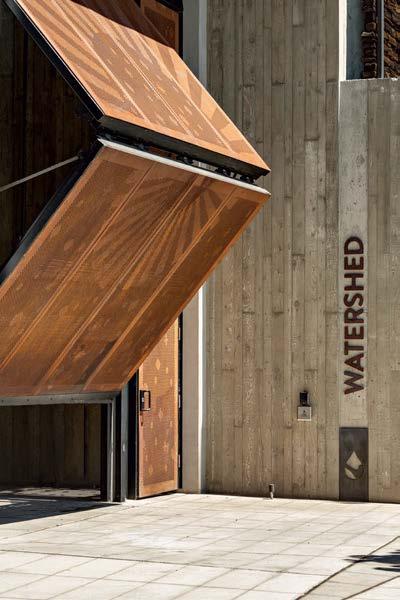

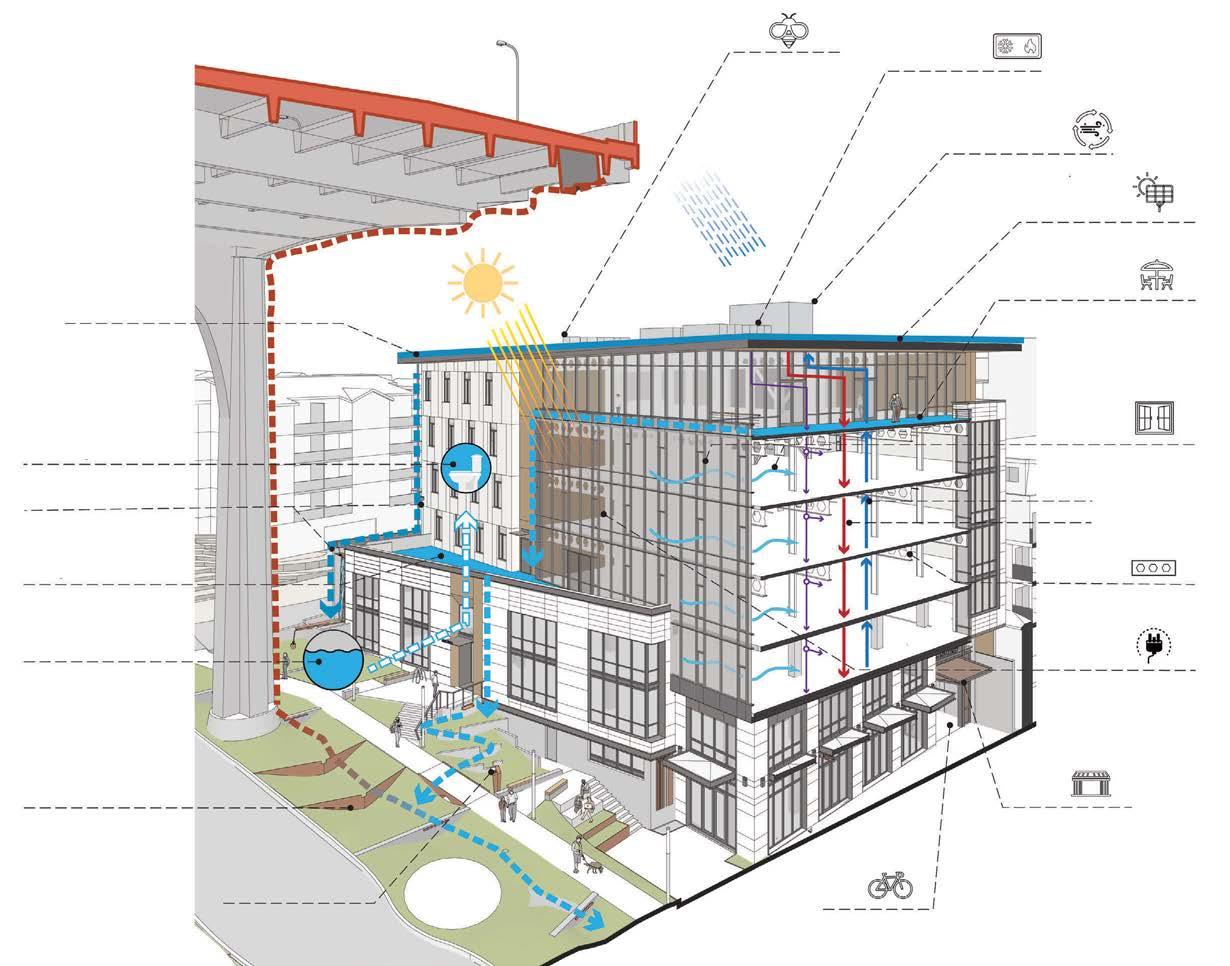

The green building movement has made dramatic strides in just a few decades, constantly advancing and widening its goals to adapt to new needs, research, and technology. If you’re looking for a symbol of this progress, look no further than Watershed, an office and retail complex designed by Weber Thompson in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood with a stunning breadth of sustainable features.

© BUILT WORK PHOTOGRAPHY

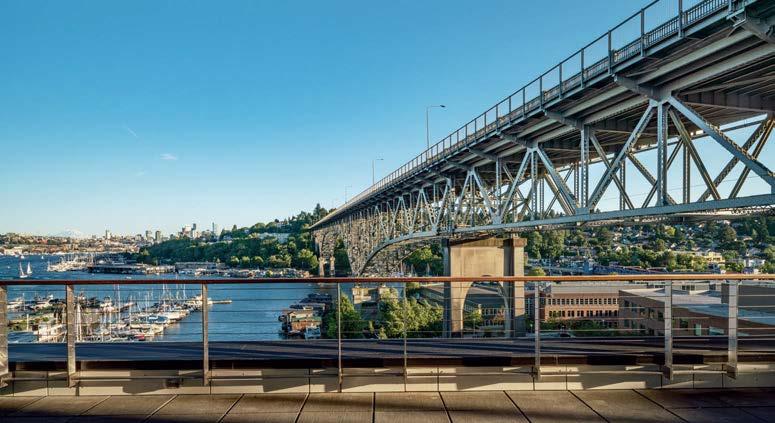

Weathered steel plates (left) welcome people into Watershed, an office and retail building in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, under the Aurora Avenue Bridge (below). The building is pursuing Living Building Challenge Petal certification.

METROPOLIS 44 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

THE PALE ROSE COLLECTION

Located on Lake Union, the building was commissioned by Center of the Universe LLC (COU), whose moniker nods to Fremont’s longtime nickname. Weber Thompson and COU had established trust years ago while developing another ambitious green building, the Terry Thomas, a 2009 LEED Gold project in the city’s South Lake Union neighborhood.

The seven-story, 72,000-square-foot Watershed is a podium edifice sitting on a tight downhill corner lot overlooking the water, under the towering Aurora Avenue

Bridge. The building provides space for 61,000 square feet of workspace and 5,000 square feet of retail, not to mention parking spaces for both cars and bikes. Its significant green bona fides were both aided and dictated by, among other things, the developer’s sustainable ambitions, Seattle’s stringent codes, and the city’s Living Building Pilot. The latter program, based on the International Living Future Institute’s (ILFI) Living Building Challenge, provides additional height and FAR (especially valuable on a floor plate

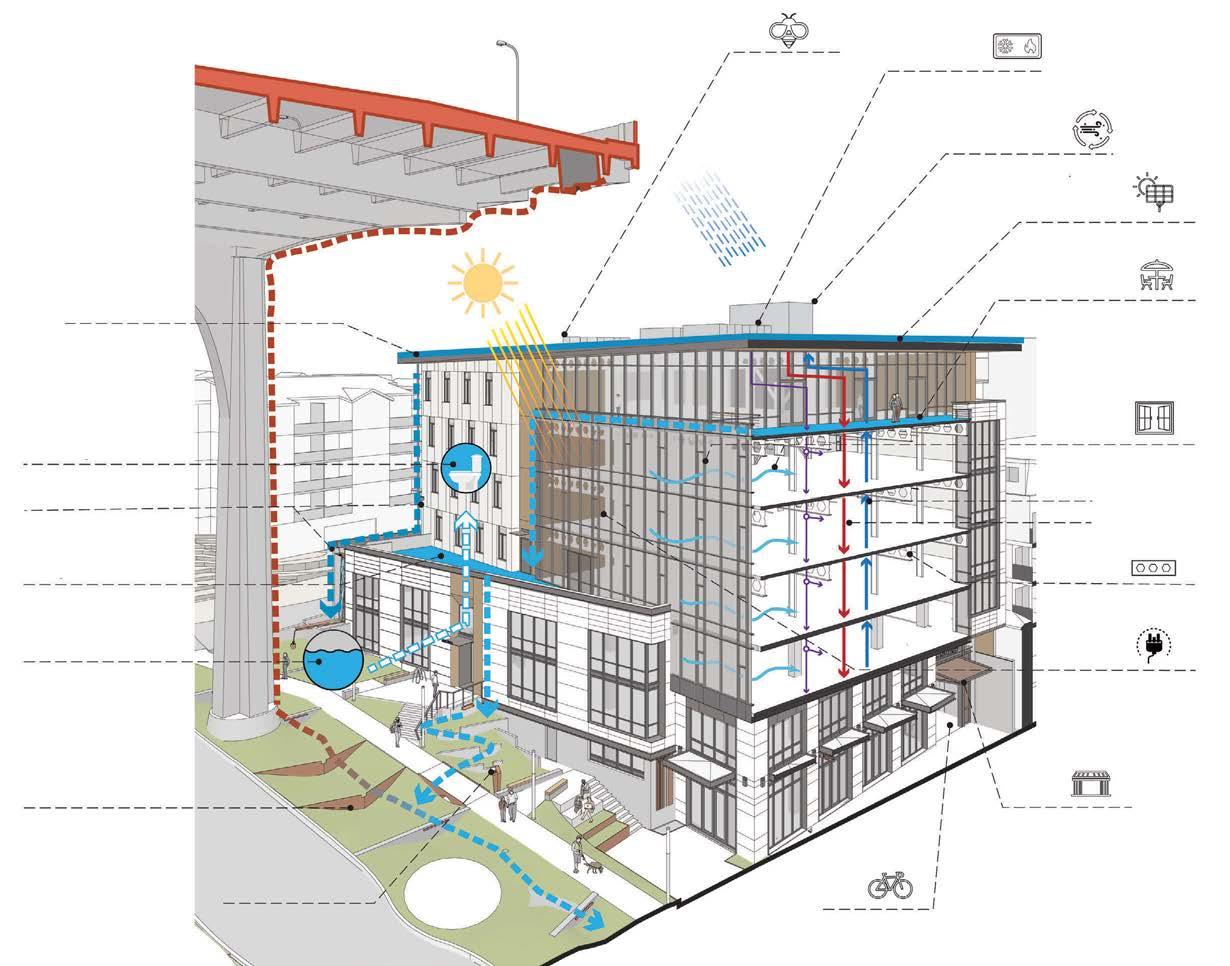

Watershed incorporates a host of sustainable design strategies that earned it an AIA COTE

Top Ten award this year.

measuring just 10,000 square feet) in exchange for meeting at least three of the stringent “petals” within the certification system. The team is pursuing the challenge’s place, materials, and beauty petals, and is in the final stages of receiving certification from the ILFI. In the meantime, it has won a prestigious Top Ten award earlier this year from the AIA Committee on the Environment.

“We give huge credit to our clients to be willing to go through these rigorous processes,” says Kristen Scott, Weber

COURTESY WEBER THOMPSON

SUSTAINABILITY Water Filter

Roof designed for rainwater collection

Low-flow, waterconserving fixtures

Rainwater art features Roof terraces manage stormwater

Below-grade rainwater cistern Bioretention system cleans Aurora Bridge and roof deck stormwater runoff

Educational signage tells the water story

Exterior entry court and access to bike room

Lightweight castellated steel beams

Self-tinting glass reduces peak cooling load and glare Weathering steel gate serving as entry canopy

DOAS air supply DOAS air return

Operable windows allow natural ventilation

Roof terrace views of Lake Union, downtown, and Mt. Rainier

PV-ready roof

Heat recovery DOAS

Heat pumps for flexible and efficient VRF mechanical system

Beehives installed on the roof

Aurora Bridge

METROPOLIS 46 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

to Lake Union

RESIDENTIAL STYLE. COMMERCIAL CAPABILITIES. roomandboard.com/business 800.952.9155

© BUILT WORK PHOTOGRAPHY METROPOLIS 48

Watershed’s most impressive contribution to the local ecology is its ability to clean about 400,000 gallons of runoff water from the neighborhood and the Aurora Avenue Bridge before it flows into Lake Union. The building achieves this through a series of bioswales with native plantings.

Thompson managing partner. The move was especially brave, she adds, given that the pilot program levies a financial penalty if buildings don’t meet its requirements in their first year of operation. To ensure that doesn’t happen, the list of sustainabilityinformed elements in the building is remarkably long.

Watershed’s most dramatic feature relates to water use and habitat sustainability. The building’s overhanging roof helps it use more than 88 percent less water than the local baseline by collecting rainwater in a 20,000-gallon underground concrete cistern, to be reused in the toilets and for irrigation. Meanwhile the structure and its surroundings play a key role in reducing the neighborhood’s toxic stormwater runoff, which has contributed to the region’s dramatically dwindling salmon and orca populations. The architects (who also served as the project’s landscape architects) helped edge Watershed with a system of stepped bioswales, treating runoff from the bridge and nearby streets.

Another major focus for the project is energy savings. Twelve months of utility data have proved Watershed to be 67 percent more efficient than a typical benchmark structure. Heat recovery is maximized via a high-performance HVAC system that includes a dedicated outside air system (DOAS) and a variable refrigerant flow (VRF) system. Meanwhile the building’s sizable upper curtain wall is embedded with self-tinting electrochromic glazing on its south and west sides, significantly reducing solar gain, glare, and thermal waste. This element has helped reduce cooling demand by an estimated 14 tons.

Next on the outsize green checklist are building materials, which were vetted to ensure they didn’t contain any Red List chemicals. Local cedar clads the underside of the roof canopy, soffits, and most of the lobby, which is highlighted by an open stairway

SUSTAINABILITY Water Filter

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023 49

and light well. Weathering steel plates cover the dramatic steel hangar front door. And recycled materials include a portion of the existing concrete foundation, which was reused as temporary shoring, eliminating about 100 tons of concrete waste.

Since its opening in 2020 the building has filled with tenants, including Weber Thompson itself on the second floor, all drawn to its beauty, tall ceilings, site, views, natural light, breezy authentic comfort, and mission, among other things. The only spaces not

yet leased are two retail suites, about 2,000 square feet in all: Retail has been slower to fill up countrywide.

“It’s really gratifying to prove that so many sustainable principles are aligned with what people are looking for after going through a pandemic,” says Scott.

“Healthy buildings are a much more attractive way to get people into office spaces,” adds Cody Lodi, a Weber Thompson principal, who also notes that the building and its landscaping have been

well received by the neighborhood. “These buildings are going into communities,” Lodi says. “We need to start seeing them as community investments.”

Meanwhile, the design—specifically its steel gutter system, landscaping, and bioswale filtration system—is beginning to have an impact beyond the project’s footprint, annually cleaning an estimated 400,000 gallons of water on its way to Lake Union. “I expect in the next five to ten years we will see meaningful results,” says Scott. M

© BUILT WORK PHOTOGRAPHY SUSTAINABILITY Water Filter

The interiors of the building incorporate healthy materials, including local cedar cladding in the lobby.

METROPOLIS 50 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

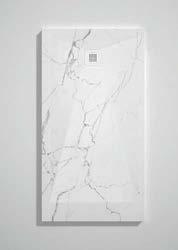

Ec o Sto ne

Introducing the industry's 1st carbon neutral porcelain tile collection in large format up to 48"x110." Reimagining the timeless beauty of travertine, EcoStone is suitable for everything from floors to façades.

Discover

the full collection

While the building plays a crucial mediatory role between the city and Lake Union, four beehives on its roof support the local honeybee population and produce 50 pounds of honey a year.

Selected Sources

CREDITS

• Design architect, graphics, landscaping: Weber Thompson

• Interiors: Weber Thompson, common areas

• Developer: HessCallahanGrey Group and Spear Street Capital

• Consultants: Turner Construction (general contractor), WSP (MEP design, built ecology)

• Engineering: DCI Engineers (structural engineer), KPFF (civil engineer)

INTERIORS

• Ceilings: Turf Design, Armstrong

• Flooring: Bentley Mills

• Furniture: Teknion, Knoll, Humanscale, Watson, Keilhauer, Blu Dot, Andreu World, Gus Modern

• Kitchen products: Bosch

• Kitchen surfaces: Richlite, PentalQuartz, Cambria

• Lighting: LightArt, Ledalite, Lumenwerx, Alphabet Lighting

• Paint: Sherwin-Williams

• Textiles: Luum Textiles

• Wall finishes: BuzziSpace

EXTERIORS

• Cladding /facade systems: Equitone, Taktl

• Glazing: Oldcastle, Vitro, View Glass

© BUILT WORK PHOTOGRAPHY SUSTAINABILITY Water Filter METROPOLIS 52 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

&5($7,1*�%($87,)8/�%$7+52206 0$'(�,1�7+(�86$ &86720�352-(&76�:(/&20( /$&$9$ �FRP FRQFUHWH�VLQN�LQ�FOD\�ILQLVK PHWDO�FRQVROH�LQ�PDWWH�EODFN PLUURU�ZLWK�PDWWH�EODFN�IUDPH IDXFHWV�LQ�PDWWH�EODFN WRZHO�EDU�LQ�PDWWH�EODFN EDWKWXE�LQ�PDWWH�ZKLWH 1(:7(55$ 0(7$//2 0(7$//2 )/28 521'$ 277$92

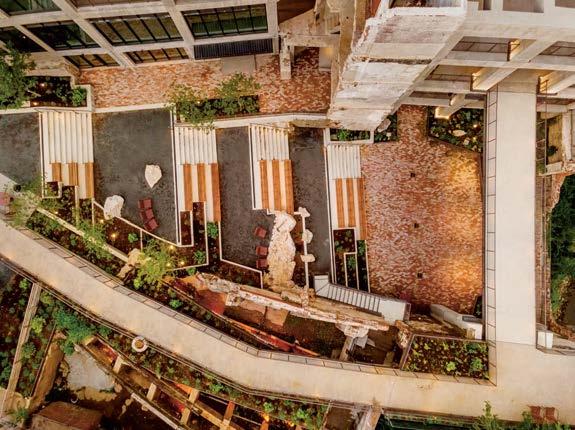

HOSPITALITY Path of Kann

Fieldwork’s design of celebrity chef Gregory Gourdet’s Portland, Oregon, restaurant fuses open-kitchen theatrics and soft natural tones.

By Brian Libby

The entrance (left) leads to Kann, a recent James Beard Best New Restaurant winner designed by Fieldwork Design & Architecture. The main dining room’s wood furnishings (below) contrast with a gold-toned recess in the ceiling.

Brass, a durable and more affordable alternative to gold leaf, also defines a ceiling element over the open kitchen, which is visible to diners (opposite).

COURTESY SHELSI LINDQUIST

54

METROPOLIS

Chef Gregory Gourdet first began planning Kann in 2019, but when the COVID-19 pandemic brought inevitable delays, he made effective use of the lockdown, penning his first cookbook, Everyone’s Table. Eventually his team leased the ground floor of a 1928 building in Southeast Portland’s Lower Burnside neighborhood, to be reimagined by Portland’s Fieldwork Design & Architecture.

“We had so many meetings with the 3D model open, looking at design options with Gregory [Gourdet],” recalls Fieldwork principal Cornell Anderson. “It became really hands-on.” As Gourdet explained it in an opening-date Instagram post last August, “No one thought we would get done on time but the team is mighty and we fought every post-COVID challenge to get here today.”

Kann, which was named the James

Beard Best New Restaurant in June, sets the mood even before one enters, with many palms and potted plants visible outside and inside the building’s glowing, glass-walled storefront: The effect is of a kind of tropical portal. A 2023 winner of the International Interior Design Association’s Will Ching Design Competition for small firms, the light-filled interior is conceived around an open kitchen with a custom

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023 55

Wood stools provide a direct view into the theatre-style kitchen while balancing brass elements such as the pendant lighting.

COURTESY THOMAS TEAL HOSPITALITY Path of Kann

METROPOLIS 56 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

A METROPOLIS series that explores the many facets of sustainable residential design.

Episode 1: A Tranquil Retreat in Cold Spring .

NEW ON

W A T C H

wood-fired iron hearth, where Gourdet and his staff are showcased like actors on a stage—interacting with customers as they barbecue, grill, and smoke. The dining room’s design takes inspiration partly from the fine-dining, white-tablecloth establishments where Gourdet trained, specifically New York’s Jean-Georges, with its eyecatching gold-leaf-festooned cove ceiling.

“Gregory wanted to bring an elevated restaurant to Portland. To be known globally,” says Fieldwork principal Tonia Hein. So Kann too has a gold-toned recessed ceiling, as well as a long

gold-colored sheath covering the range hoods. The designers, however, chose the more durable, affordable brass, which nevertheless retains an iridescent quality. “It just kind of glows,” Hein says.

The brass stands out all the more against Fieldwork’s muted palette of natural wood and light, earthy tones. The design lets the visually pleasing food, blue earthenware dinnerware, and artwork stand out (especially an abstract Peter Gronquist painting commissioned specifically for Kann). “We did not want anything to compete with how colorful and vibrant the food is,” Hein says.

The moody downstairs bar Sousòl was added after the restaurant was already under way. The architects created the bar’s atmosphere with illuminated bottle shelving, floral-patterned wallpaper, and fuchsia velour banquettes.

Instead, an array of natural materials helps Kann feel very much like an Oregon restaurant. It also feels a bit residential, starting with the extensive use of white oak from the dining room flooring, chairs, and armoires to the chefs’ work surfaces topped with oak instead of stainless steel. A wall of stacked firewood near the entrance also adds a rugged, unpretentious ambience.

There is scarcely a right angle in the place, from the curving chef’s counter to a series of oval pendant lights hanging over a family-style dining table in front and the corner bar in back, meant to evoke the

COURTESY SHELSI LINDQUIST

HOSPITALITY Path of Kann

METROPOLIS 58 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

‘Public Display', designed by spacial designer Michael Bennett of Studio Ker and Form Us With Love design studio based in Stockholm. Presented by NYCxDESIGN in partnership with AIA New York and the Center for Architecture, in celebration of Archtober. Learn more at nycxdesign.org In partnership with: Organized by:

Design Pavilion October 12-22 NYC Presents

traditional Haitian baskets worn to transport food from the markets.

Instead of white tablecloths, milkycolored tabletops were made using a custom wax-embedded concrete that has a smooth, soaplike finish. The open kitchen’s black iron hearth is framed with earth-toned brick that extends to form the backsplash wall. The nearby chef’s counter, where diners enjoy a front-row seat for the cooking show, is clad in quartzite with blue and pink veining, for a hint of the Caribbean.

After Kann’s design was well under way, Gourdet’s team added a sister project: the downstairs bar Sousòl. Here the restaurant’s bright space gives way to a darker, more atmospheric nighttime space, featuring illuminated bottle shelving, floral-patterned wallpaper, and fuchsia velour banquettes lining the wall, as well as a club-level sound system that has already attracted DJs for after-hours gatherings.

After facing first extensive delays and then an accelerated schedule, this was a

project of high intensity and high reward. “I personally needed a project like this,” Hein says. “After the pandemic it just brought all of my creativity back again and challenged that in a new way.”

A few weeks before Kann and Sousòl’s opening, it all hit her while going over final details with operations director Tia Vanich. “I remember Tia left the table for a moment and I just started to cry,” Hein recalls, “just because everything was coming to life and this was what we had all been working so hard for.” M

COURTESY SHELSI LINDQUIST HOSPITALITY Path of Kann

METROPOLIS 60 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

Kann is not only chef Gregory Gourdet’s first restaurant of his own conception, but his chance to share the cuisine of Haiti and the Caribbean diaspora, which he grew up on as a New York City–born child of Haitian immigrants.

Finest selection of contemporary European wood and gas stoves and fireplaces Varia 0-clearance Built-in Fireplace 914.764.5679 www.wittus.com Interested in being a guest or sponsoring? Reach out to Kelly Kriwko, kkriwko@sandowdesign.com LISTEN HERE Deep Green takes you to the forefront of responsible architecture and design! From discovering the power of community solar projects to debating the real meaning of biophilia, our expert guests help you explore sustainability in the broadest sense of the word. HERE

NEW TALENT New Traditional

Los Angeles–based furniture practice L.A. Door draws on the history of decorative arts to revitalize and reinterpret the long-standing staples of American design—no irony intended.

By Cindy Hernandez

L.A. Door is the Los Angeles furniture practice of Katie Jean Payne (b. 1982, Detroit, Cherokee Nation) and Doug McCollough (b. 1982, Tokyo, American).

The duo’s background in design histories provides the foundation for a studio practice that updates and recontextualizes instances of American decorative arts. The pair has shown with Marta Los Angeles in 2021, at Built In at the Neutra VDL House, and again in 2023, for their inaugural solo exhibition, L.A. Door: Open and Close

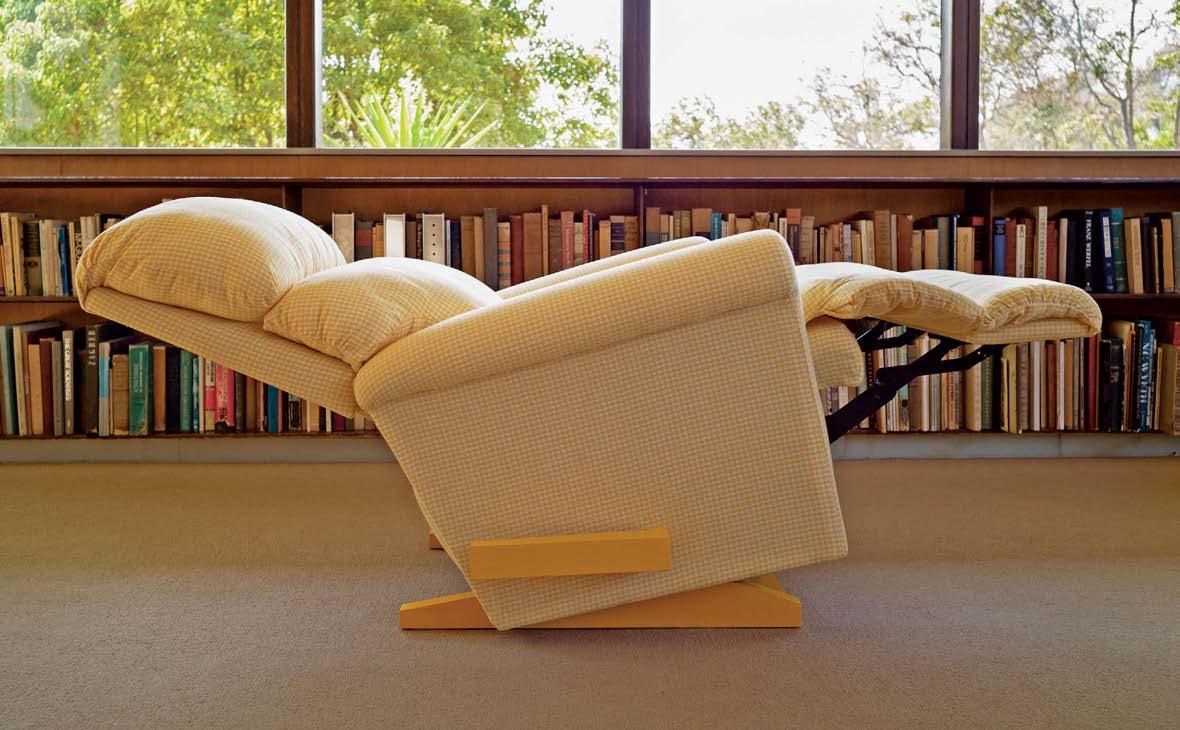

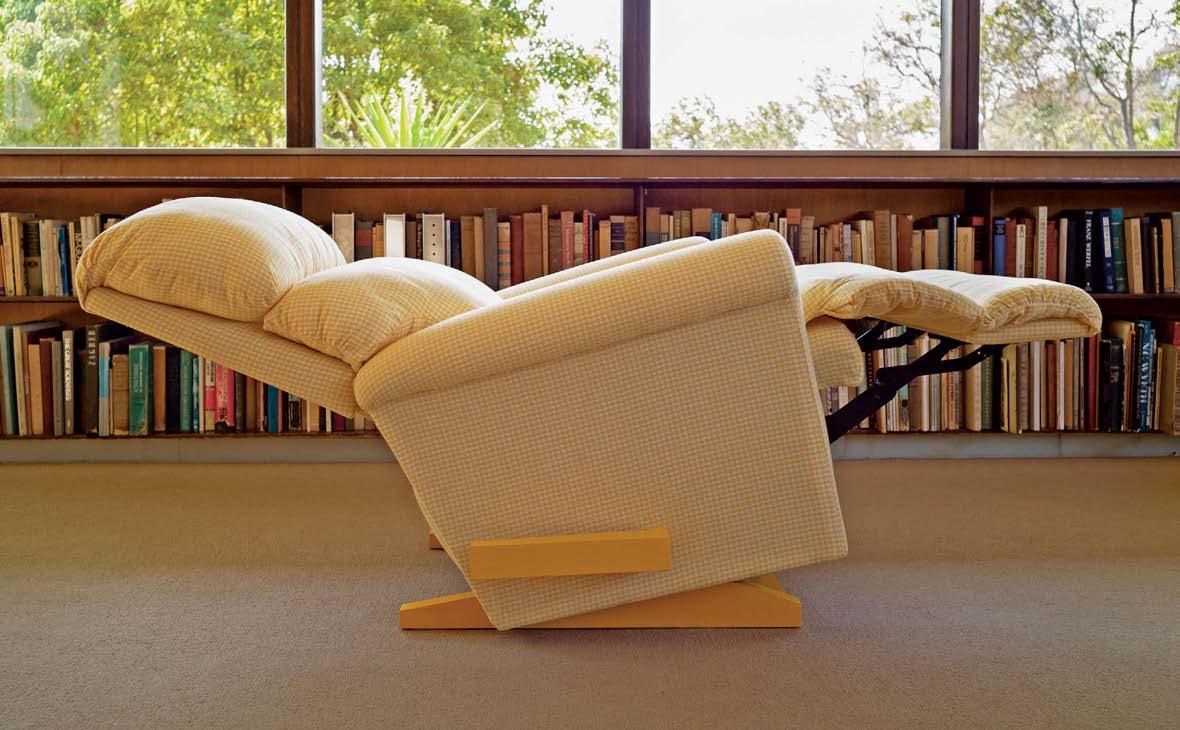

The dour face of comfort in American design has long belonged to champions of ergonomics and efficiency. (Take the archetypal molded fiberglass chair, for example, with its rigorous lab testing, statistical analysis, and patented fibers.) The midcentury icon emanates a faux coziness that has become synonymous with ideas of ease and “good American design.” Perhaps, then, the inverse of that ideal is the distinct visual language of the typical American Midwestern living room where pastel gingham curtains and wooden Colonial-style side tables frame a different American icon: the reclining chair. Los Angeles–based design studio L.A. Door is willing to admit what many won’t—comfortable design is beautiful design.

COURTESY THE ARTISTS

METROPOLIS 62

Los Angeles–based Katie Jean Payne and Doug McCollough of L.A. Door have established a furniture practice that blends elements across design history, from riffs on Gerrit Rietveld’s Modernist Z-shaped chair to vernacular Americana and PoMo nostalgia. “It starts with Gerrit Rietveld’s classic Zig Zag chair, and then Garry Knox Bennett did a series of chairs that were all playing on the Rietveld chair, and one of them was this Great Granny Rietveld where he upholstered it in a ‘granny fabric’,” McCollough explains. “Our contribution is adding the plastic slipcover.” A blanket chest made of quilted maple wood (opposite) also features pulls by Bennett. The studio furniture maker Bennett passed away last year.

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023 63

The studio was established in 2019 by designer Katie Jean Payne and furniture maker Doug McCollough. The duo began their collaboration with a series of actual doors inlaid and crafted with sex-toyshaped handles (fitted lower on the door for pleasure’s sake) and have since gone on to create limited-edition furniture that references an entire gamut of American decorative arts history, from the strict utility and proto-modernity of Shaker furniture to the luxurious working-class comfort of the La-Z-Boy recliner.

L.A. Door’s magic touch balances history and function. “Our idea in the beginning was to celebrate the comfort, beauty, and pleasure of traditional American design,” says Payne. The studio reimagines American clas sics with bespoke artisanal techniques, sourcing materials that are quintessentially Los Angeles, such as their various colorful takes on the reclining chair and love seat, equipped with cup holders.

“The first thing that we designed together in L.A. Door was kind of like a faux frame and panel door using linoleum to graphically represent a frame and panel construction door,” explains McCollough. The duo also incorporate laminate in other work such as a 2020 quilted maple corner cabinet (top left). The studio had its first solo show at Los Angeles gallery Marta this past spring, showcasing new and existing work including doors, cabinets, and Shaker-inspired blanket racks made of solid cherry wood (above).

COURTESY THE ARTISTS NEW TALENT New Traditional

METROPOLIS 64

Often familiarly nostalgic, this conceptual precision stems from Payne’s own roots and upbringing in a Colonial home in Detroit, prior to receiving her MFA in American Fine and Decorative Art at Sotheby’s. “There’s a widespread rudimentary craft element to early American firms that I really like,” Payne explains. The studio actively references the design of common people, as opposed to the design objects often found in museum collections. “I think the ’90s Sears catalogs’ home goods sections are far more interesting.”

The duo’s wood-turned wall hooks, for example, recall Shaker pegboards, yet reject the group’s celibacy as the cherry wood hooks take on the shape of a butt plug. In their design for a blanket chest, an outdated storage piece is given a new, multifaceted

life, fashioned out of curly maple and outfitted with teardrop drawer pulls created in collaboration with the late American studio craft designer Garry Knox Bennett, who passed away last year.

Sourcing their provocative textiles from a local supplier, their daringly curated selections range from airbrushed flowers to yellow gingham, bringing forth a more “accurate” interpretation of 1980s nostalgia—in contrast with other contemporary reinterpretations out there that merely imply the ’80s. “There is this guy in the valley that just has one of the most incredible collections of upholstery and drapery fabrics. It’s just one of those L.A. places that we found and it’s very inspiring,” Payne explains. “You could put together the most amazing 1980s/1990s kitchen with drapes, upholstery, everything. It’s all there.”

A material like linoleum brings up not only Ettore Sottsass’s 1980s but the 1950s-era kitchens that came before. But for L.A. Door’s linoleum doors, McCollough and Payne opt for natural linoleum versus stark contrasting graphics. “It can’t be too Memphis. It can’t just be a cheap thrill, right? With the doors, it’s not polka dots. It’s not vertical black and white stripes,” says McCollough.

The commitment to comfort goes against the unspoken conventions that collectible design is sculpture for the home. “A big thing I think is comforting is nostalgia—it feels good. I think, oh, this feels like my grandma’s house. And to see other people feel that is nice,” Payne concludes. I think we can all bask in the good feelings and restorative power of a La-Z-Boy recliner. M

L.A. Door’s L.A. Lazy II reclining rocker is upholstered in woven linen with hand-painted cherry hardwood accents. Pictured here, the chair is leaned back in Built In, a 2021 group exhibition at Richard Neutra’s VDL Studio and Residences in Los Angeles, curated by Marta, Erik Benjamins, and Noam Saragosti.

L.A. Door’s L.A. Lazy II reclining rocker is upholstered in woven linen with hand-painted cherry hardwood accents. Pictured here, the chair is leaned back in Built In, a 2021 group exhibition at Richard Neutra’s VDL Studio and Residences in Los Angeles, curated by Marta, Erik Benjamins, and Noam Saragosti.

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023 65

INSIGHT Gathering with Purpose

Jeffersonian dinners inspire conversation, forging new paths for local designers.

By Amanda Schneider

If you haven’t heard of a “Jeffersonian dinner” before, you’re not alone. The tradition began with Thomas Jefferson, who was known to invite the thought leaders and influencers of his day to share conversation in his home in the 1700s. And there was a distinct characteristic to these talks that made them special: Jefferson and his guests engaged in one single thread of conversation, with only one person speaking at a time. By doing so, they unlocked the power of their collective wisdom.

The purpose of a Jeffersonian dinner is to listen, learn, debate, and inspire one another through meaningful dialogue. When ThinkLab hosts these conversations, our goal is to create a safe environment for individuals from the community to do just that. Here, we share how you can get involved in an upcoming Jeffersonian dinner with ThinkLab or create your own.

OUR RULES FOR A JEFFERSONIAN DINNER ARE SIMPLE:

01 We have one main conversation (no side conversations).

02 We try to engage in equal “airtime” for all guests.

03 There are no right or wrong answers. We encourage vulnerable sharing and challenging your neighbor (respectfully).

The Setup

We recommend booking a private room at an inspirational local restaurant. It is critical to provide a space where participants will not only be able to hear each other but also be more likely to get vulnerable and honest with their peers.

With an experienced facilitator and the right mix of participants at the table, the topic can be nearly anything, but we recommend choosing broader, open-ended topics over narrow and specific questions. Our dinner themes typically revolve around the business of design.

The most critical component is bringing together the right people. ThinkLab’s goal is to assemble a group where even the most connected people in the most connected markets meet someone new and can learn from varied perspectives.

The next most critical component is the “what to expect” invite. This is an email sent to participants that shares a welcome message, the rules, a brief personalized blurb about each participant and why

they were invited (we include links to their LinkedIn profiles so that guests can connect with one another in advance), and three discussion questions (one of which will accompany the start of each course) with a nudge to think about these questions in advance.

The Dinner

This is not your typical corporate networking event. Our dinners start early (because they can go long). Each dinner has a total of 8–12 participants, including sponsors and hosts.

To kick off, the facilitator prompts the start of the discussion with something like “We can have the same discussions we always have, or we can get into what you really want to discuss. It’s up to all of you.” A new question is introduced with each course.

SAMPLE QUESTIONS INCLUDE:

• Q1 (salads): “Introduce yourself, your company, your role, then answer the following question: ‘In the past, the role of design was _____. In the future, the role of design will be _____.’ ”

• Q2 (main course): “What disrupters are on the horizon, and how might they affect your business, role, and hiring practices?”

• Q3 (dessert): “How do we shift our mindset from ‘disrupters as challenges’ to ‘disrupters as opportunities’?”

What Happens Next

We typically close with one last “lightning round” that explores the following prompt: “Please share one thing that you are thinking about as you leave here.” This is often one of our favorite parts of the dinner, because it helps bring to the surface the shifts in perspectives and fresh ideas sparked by the conversation.

To hear specific insights from our dinners, follow @thinklab.design on LinkedIn or Instagram. Or, for a list of upcoming cities where you can explore becoming a host or participant, reach out to Olga Odeide at oodeide@sandowdesign.com.

COURTESY THINKLAB

METROPOLIS 66

Amanda Schneider is president of ThinkLab, the research division of SANDOW DESIGN GROUP. Join in to explore what’s next at thinklab.design/join-in

ThinkLab invites members of the design community to listen, learn, and debate during its Jeffersonian dinners. Above, left to right: Carlos Madrid III, SOM; Anosha Zanjani, HDR; Anya Ostry, CBRE; Nellie Hayat, Density; Marisa Boedeker, Material Bank; Amiyra Perkins, Pinterest; Brett Shwery, AECOM; Amanda Schneider, ThinkLab; Bill Bouchey, Gensler; James Woolum, ZGF Architects; Katlain Schultz, Williams-Sonoma. Left, left to right: Jennifer Ruckel, 3form; Amanda Schneider, ThinkLab; Rhiannon Adams, Mohawk

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023 67

Creative Strategies for Low-Carbon Spaces

The Climate Toolkit for Interior Design is a living resource to aid interior designers in incorporating decarbonization into their practice.

Sections Include:

• Interiors and Climate

• Work with Clients

• Change Your Practice

• On Your Next Project

• Wishlist

Together, we can make a global impact and contribute to the safety and well-being of generations to come.

EXPLORE

step outside

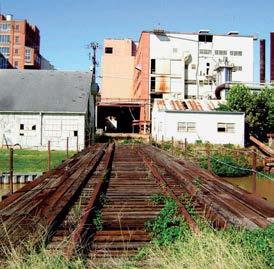

The notion that urban outdoor space is owned by the people is a popular ideal among American designers: Manicured parks and lively squares and marketplaces spring to mind. But technically “outdoor space” also includes deserted commercial plazas, heat-trapping sidewalks, neglected trails, and areas with divisive histories that few want to claim. For average citizens, solutions for these unappealing areas are becoming more important than another prestige project built for commerce. The stories on the following pages present a range of perspectives on making sense of the past, improving current conditions, and opening up future possibilities for outdoor spaces.

COURTESY CREATIVE COMMONS

METROPOLIS 69 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023

Greening the Future

The Brooklyn-based landscape architecture and design-build studio blends fabrication and urban placemaking to reframe public space.

By Laura Raskin

On a recent visit to Future Green’s office in Brooklyn, things were in flux, including the material library. For the time being, a displaced tower of brick samples was being relocated next to a row of computer stations as the 15-year-old landscape architecture and design-build studio had just downsized its footprint in the industrial building it has called home since 2012.

Future Green’s woodshop and design studio will remain in Red Hook, but the metal shop has been transplanted upstate to a farm that the studio purchased in Chester, New York.

The s hop will take over a metal-framed building with garage doors, a former stable will be used for additional woodworking, and the farmhouse will be a satellite design office for house staff who are visiting or who decide to relocate. Vegetables will be grown in the horse paddock.

When David Seiter founded the firm in 2008, smaller-scale projects and installations supported Future Green’s design work. As name recognition and commissions grew, the design work opened up opportunities for custom fabrication. “It’s been a really nice balance,” says Seiter. Now the upstate satellite represents Future Green’s evolution as it secures more public and larger-scale work—such as a lush civic and retail core on a former power plant site in Atlanta, or the renovation and rethinking of the Broadway Malls, the green artery that runs from 70th to 168th Streets in Manhattan—and focuses its fabrication

With a landscape design studio based in Red Hook, Brooklyn, and a metal shop located on a farm in Chester, New York (top), Future Green describes itself as a studio “at the forefront of Landscape Urbanism—a design movement that combines a deep understanding of plants, people, and places.” Opposite: Sited on the former property of the Georgia Power company in Atlanta, the 4th Ward includes pedestrianoriented streetscapes and plazas inspired by the Appalachian Mountains.

step outside COURTESY FUTURE GREEN

METROPOLIS 70

COURTESY RICH BRASHER SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023 71

step outside METROPOLIS

72

arm on furniture and urban placemaking. But the firm maintains its design-build spirit. “That’s a draw, that collaborative process. You learn so much,” explains Zenobia Meckley, associate managing principal, who first joined the firm in 2012. “It’s what attracted me.”

The farm also propels Future Green’s staff out of the city and into “relating to plants,” adds Meckley. It’s plants, after all, that are at the heart of the studio’s conceptual strategy, the roots of which go back to Seiter’s teenage gardening business in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. In his book Spontaneous Urban Plants: Weeds in NYC (Archer, 2016), Seiter and Future Green’s team of horticulturists, landscape architects, and artists explored and celebrated weeds, “the overlooked backbone of an emergent green infr astructure” that thrives against the odds. A deep investigation of urban ecology and the forces that have affected a site over time remains Future Green’s starting point.

This is evident at the 12.7-acre Neuhoff District on the Cumberland River in Nashville, Tennessee. There, Future Green conceived

COURTESY SMITH GEE STUDIO/SETH PARKER SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2023 73

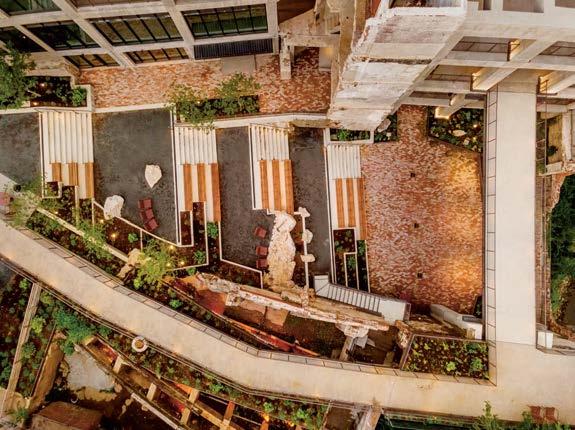

Located in Nashville, Tennessee, the Neuhoff District is a strategic preservation of a 12.7-acre waterfront site dominated by the ruins of an old meatpacking plant. Future Green transformed the area, situated on the Cumberland River, by creating pocket gardens, pedestrian pathways, and an amphitheater made from the repurposed brick of the factory buildings.

step outside

Situated between New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral and the ice-skating rink at 30 Rock, Future Green’s Rockefeller Center Channel Gardens (this page) has hosted a variety of temporary displays over the seasons. The studio is currently serving as the landscape architecture consultant for Newark’s upcoming New Jersey Performing Arts Center redesign (opposite).

of a progression of pocket gardens, courtyards, and pedestrian pathways that weave through the mixed-use district and terminate on the riverbank. Located on the site of an early 20th century meatpacking plant, the project includes a cluster of seven main buildings—some new and others adapted from the original plant— by Smith Gee Studio and S9Architecture (with HKS as architect of record). “We drew heavily on the ecologies of the region, the Appalachian Piedmont. The plantings are meant to evoke a layering and composition to create something really immersive and reminiscent of another environment,” says Meckley.

Future Green’s concept for the site evolved as demolition began and the team unearthed unexpected artifacts. At the River Terrace—carved out of the footprint of an arcing section of one of the repurposed brick factory buildings—Future Green created an amphitheater that steps down to a plaza laid with reclaimed brick. Bedrock unearthed during the excavation was integrated into a series of stepped planters. The amphitheater also includes steps and seat walls topped with wood slat benches and embedded limestone boulders. Elsewhere, a series of found concrete wedges, the original purpose of which remains a mystery, will be repurposed in a water feature.