Bringing Tech Down to Earth

When digital fantasy meets the real world

THE TECH ISSUE

2023

January/February

Virginia San Fratello at San Jose State University

ADAPTABILITY. MADE BEAUTIFUL.

The ideal office system for the modern workplace, GSD’s tables and benches feature built-in power sources that keep devices charged and help teams Get Stuff Done.

Designed by EOOS. Made by Keilhauer.

Designed by EOOS. Made by Keilhauer.

KEILHAUER.COM

DESIGN THAT SUSTAINS

©2023

Keilhauer LTD.

Image by Imperfct*

Image by Imperfct*

Artful acoustics for welcoming spaces

turf.design

Arbor Ceiling Baffles

teknion.com

FEATURES

Hi-Tech, Hi-Gloss 76

A new wave of designers blend elements of High-Tech Architecture, creating interiors and objects that are a testament to function as ornament.

Salt of the Earth 94

The work of Oakland, California–based design firm Rael San Fratello transcends categories but always remains grounded.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: COURTESY © JAMES HARRIS; COURTESY © MICHAEL MORAN; KELSEY MCCLELLAN

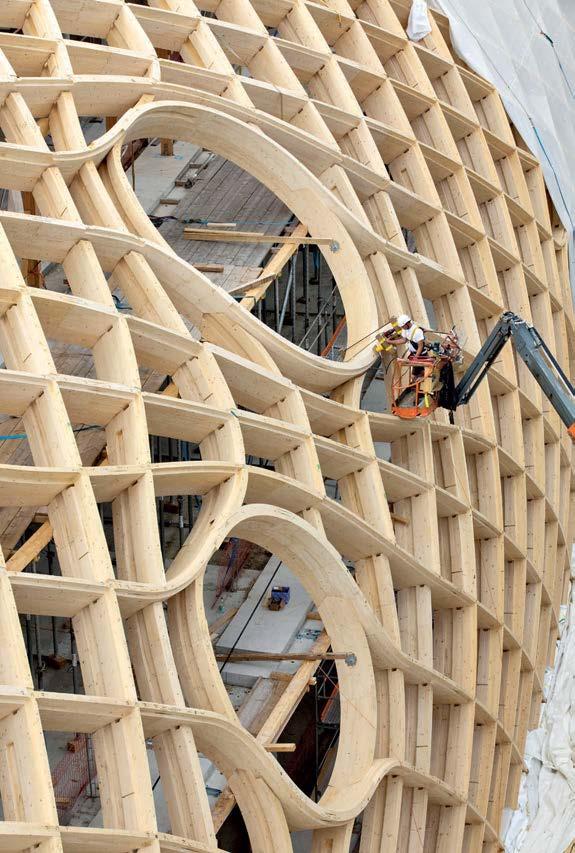

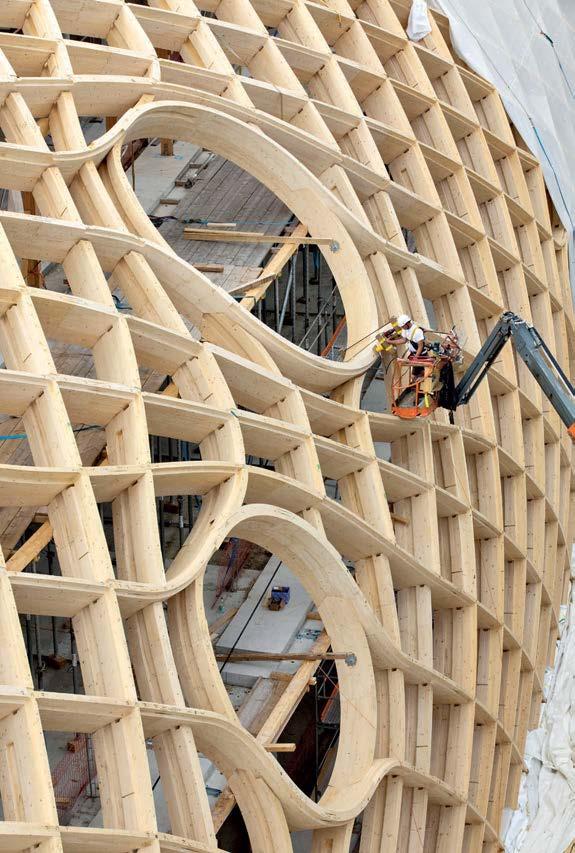

The Wizard of Wood 86

106

Shigeru Ban, the Pritzker Prize–winning maestro of timber architecture, weighs in on contemporary mass timber buildings.

METROPOLIS 6 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

Metropolis’s Responsible Disruptors program honors A&D technology projects that make a positive impact.

Samples. Simplified.

Discover

200+ categories.

450+ brands.

One site. One box.

100% carbon neutral shipping.

new

materials all in one place. Save time and get back to what you love.

materialbank.com

TOP: COURTESY KYRRE SUNDAL; BOTTOM: COURTESY DAVID BOYER CONTRIBUTORS 16 IN THIS ISSUE 18 THINK TANK 20 SPECTRUM 32 SOURCED Craft and Context 44 TRANSPARENCY Floor Show 46 PRODUCTS Sleek Chic 48 SUSTAINABLE Park Place 52 REUSE Radical Repurpose 58 DEPARTMENTS JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023, Volume 43, Number 1. METROPOLIS® (ISSN 0279-4977) is published six times a year, bimonthly. Periodical postage is paid in New York, NY, and at additional mailing offices. Canada Post International Publications Mail Product (Canadian Distribution) Sales Agreement No. 0861642. Publications Mail Agreement No. 40028983. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to circulation department or DPGM, 4960-2 Walker Rd., Windsor, ON N9A 6J3. Postmaster: Send address changes to Metropolis, PO Box 8552, Big Sandy, TX 75755. Subscription department: (800) 344-3046. Subscriptions: Six issues for $32.95 U.S.A., $52.95 Canada, $69.95 airmail all other countries. Domestic single copies $9.95; back issues $14.95. Copyright © 2023 by Sandow Media. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. Material in this publication may not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. Metropolis will not be responsible for the return of any unsolicited manuscripts or photographs. Publishing and editorial office is at 3651 NW 8th Avenue, Boca Raton, FL 33431. On the cover: Virginia San Fratello at San Jose State University, photographed by Kelsey McClellan WORKPLACE On the Grid 64 NEW TALENT AnthropologistArchitects 68 INSIGHT Personalizing the Buyer Journey 72 NOTEWORTHY Dolores Hayden 112 p. 58 22 What makes an architecture and design practice unique? How do firms and offices develop areas of expertise, deep insights, and passion projects? Metropolis editor in chief Avinash Rajagopal sat down with 20 firms in 2022, to find out. Here are nine architecture and design leaders on what gives them their edge. p. 64 METROPOLIS 10 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

FROM TOP COUNTERCLOCKWISE: COURTESY GLUCK+; COURTESY RAFAEL GAMO; COURTESY DMINTI METAVERSE AND JOSEPHINE MECKSEPER Meet the Firm Building New Amenities for New York’s Underserved Communities With a unique combination of architecture and construction expertise, GLUCK+ brings top-quality design to nonprofits and public institutions in northern Manhattan and the Bronx. METROPOLISMAG.COM More of your favorite Metropolis stories, online daily Join discussions with industry leaders and experts on the most important topics of the day. Register for free at metropolismag.com/ think-tank

Hani Rashid Builds a Fantasia of Art and Architecture in the Metaverse Called Dminti Metaverse, the platform displays digital work by blue-chip artists in an otherworldly setting with the aim of attracting new, more diverse audiences. At Deutsche Bank’s New York Headquarters, Work Is About More than the Desk A move uptown was an opportunity for the financial giant and Gensler, its designer, to explore a new, more flexible way of working. METROPOLIS 12 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

Architect

Introducing the 5 most requested specialty finishes. For those less concerned with staying in the lines. Indoor, outdoor, and custom options for residential and commercial applications. ¨ www.infinitydrain.com Made in the USA Color Theory

Satin Champagne

Polished Gold

Polished Brass

Matte White

Gunmetal

EDITORIAL

EDITOR IN CHIEF Avinash Rajagopal

DESIGN DIRECTOR Tr avis M. Ward

DEPUTY EDITOR Kelly Beamon

EDITORIAL PROJECT MANAGER Laur en Volker

DIGITAL EDITOR Ethan Tucker

ASSOCIATE EDITOR J axson Leilah Stone

DESIGNER Rober t Pracek

COPY EDITOR Benjamin Spier

FACT CHECKER Anna Zappia

EDITORS AT LARGE Ver da Alexander, Sam Lubell

PUBLISHING

VICE PRESIDENT, PUBLISHER Carol Cisco

VICE PRESIDENT, MARKETING & EVENTS Tina Brennan

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

ACCOUNT

.3690 Michael Croft 224.931.8710

L aury Kissane 770.791.1976

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT

Kathryn Kerns 917.935 .2900

MARKETING & EVENTS MANAGER Kelly Kriwko kkriwko@sandowdesign.com

EVENTS MANAGER Lorraine Brabant lbrabant@sandowdesign.com

SENIOR DIRECTOR, CONTENT DISTRIBUTION Amanda Kahan

SENIOR MANAGER, DIGITAL CONTENT Ile ana Llorens

SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR Zoya Naqvi

METROPOLISMAG.COM

@metropolismag

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, FINANCE & OPERATIONS Lorri D’Amico

DIRECTOR, PARTNER SUCCESS Jennifer Kimmerling

PARTNER SUCCESS MANAGER Olivia Couture

SANDOW DESIGN GROUP

CHAIRMAN Adam I. Sandow

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Erica Holborn

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER Michael Shavalier

CHIEF DESIGN OFFICER Cindy Allen

CHIEF SALES OFFICER Kate Kelly Smith

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT + DESIGN FUTURIST AJ Paron

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, DIGITAL + STRATEGIC GROWTH Bobby Bonett

VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES Lisa Silver Faber

VICE PRESIDENT, PARTNER + PROGRAM SUCCESS Tanya Suber

VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Laura Steele

VICE PRESIDENT, STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS Katie Brockman

SENIOR DIRECTOR, STRATEGIC INITIATIVES Sam Sager

DIRECTOR, VIDEO Steven Wilsey

SANDOW DESIGN GROUP OPERATIONS

SENIOR DIRECTOR, STRATEGIC OPERATIONS Keith Clements

DIRECTOR OF PRODUCTION Kevin Fagan

CONTROLLER Emily Kaitz

DIRECTOR, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY Joshua Grunstra

METROPOLIS is a publication of SANDOW

3651 FAU Blvd. Boca Raton, FL 33431

info@metropolismag.com

917.934.2800

FOR SUBSCRIPTIONS OR SERVICE

800.344.3046

customerservice@metropolismagazine.net

SANDOW was founded by visionary entrepreneur Adam I. Sandow in 2003, with the goal of reinventing the traditional publishing model. Today, SANDOW powers the design, materials, and luxury industries through innovative content, tools, and integrated solutions. Its diverse portfolio of assets includes The SANDOW Design Group, a unique ecosystem of design media and services brands, including Luxe Interiors + Design, Interior Design, Metropolis, DesignTV by SANDOW; ThinkLab, a research and strategy firm; and content services brands, including The Agency by SANDOW, a full-scale digital marketing agency, The Studio by SANDOW, a video production studio, and SURROUND, a podcast network and production studio. SANDOW Design Group is a key supporter and strategic partner to NYCxDESIGN, a not-for-profit organization committed to empowering and promoting the city’s diverse creative community. In 2019, Adam Sandow launched Material Bank, the world’s largest marketplace for searching, sampling, and specifying architecture, design, and construction materials.

Tamara

917.449

Stout tstout@sando wdesign.com

.2845

646.824.4609

917.216

MANAGERS Ellen Cook ecook@sando wdesign.com 423.580.8827 Gr egory Kammerer gkammer er@sandowdesign.com

Colin Villone colin.villone@sando wdesign.com

METROPOLIS 14 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

THIS MAGAZINE IS RECYCLABLE. Please recycle when you’re done with it. We’re all in this together.

RESIDENTIAL STYLE. COMMERCIAL CAPABILITIES. roomandboard.com/bicontract 800.952.9155

RITA LOBO

Rita Lobo is a Brazilian-British journalist who splits her time between London, Montreal, and Rio de Janeiro. She has covered topics from business to travel, but found her niche covering architecture and design internationally. When she is not traveling the world looking at architectural gems, she writes for film and TV, with her debut feature set to hit screens in 2023. Lobo wrote this issue’s Workplace column (p. 64) on Bio Square.

CINDY HERNANDEZ

Cindy Hernandez is a design historian and writer from New York City. Her research interests include futurity, utopias, theme parks, videogames, and American material culture. In 2017, she cofounded the Consumer Aesthetics Research Institute, a grassroots open-source design historical resource focused on archiving micro-trends and movements in design. She has a master of arts in history of design and curatorial studies from The New School. Hernandez penned “Hi-Tech, Hi-Gloss” (p. 76) for this issue.

KELSEY MCCLELLAN

Kelsey McClellan is a still-life, portrait, and documentary photographer based in San Francisco. She is inspired by wry humor, the mundane, and interesting and unexpected color combinations. In 2021 she self-published a book of her ongoing personal project titled If This Isn’t Nice. For this issue, McClellan photographed Rael San Fratello principals Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello for “Salt of the Earth” (p. 94).

Loop, Fractal, and Vertex

Post-Consumer Recycled Polyester

COURTESY THE CONTRIBUTORS

Axis Collection Connect,

100%

MayerFabrics.com

CONTRIBUTORS

METROPOLIS 16 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

Building Technologies, With Purpose

As a millennial who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s, I’m still surprised that we look back on those years with nostalgia in graphic design and fashion. Now in “Hi-Tech, Hi-Gloss” (p. 76), writer Cindy Hernandez analyzes how a slew of interior design projects around the world are revisiting that era’s celebration of industrial materials and fluorescent lighting. As we step into the metaverse, with the ruins of social media and cryptocurrency all around us, it makes sense that designers should feel some nostalgia for a simpler digital age, no matter how recent.

“Architects are always looking for the fashionable style of the day,” says Pritzker Prize laureate Shigeru Ban, referring to another obsession of our time—mass timber. In “The Wizard of Wood” (p. 86) he seems to urge us to find some higher creative purpose in our pursuit of the latest building technology, some ideal that lies beyond calculations of carbon emissions and a desire to soothe our climate anxiety. He strives for structural integrity and ingenuity. What do the designers of other mass timber buildings aspire to?

Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello (“Salt of the Earth,” p. 94) raise similar questions about the purpose of technology with their work. As founders of the California-based firm Rael San Fratello, they have had a polymorphic, much-feted career in which they have been characterized either as tech wunderkinds (because of their extensive explorations with 3D-printing objects and buildings) or as activists thanks to their long engagement with communities migrating across the United States–Mexico border.

But what’s truly remarkable about them is that they don’t see building technologies and border politics as mutually exclusive. Consider this: They spent years 3D-printing using humble materials until they were recently able to digitally fabricate beautiful earthen buildings that bear unmistakable connections to Indigenous craft and architecture. Their projects show influences of both ancient Pueblo culture and later Indo-Hispanic traditions, which span the presentday border between Mexico and the southwestern United States.

There’s a lesson in their work: If architects and designers fully accept their responsibility in shaping the world, then it isn’t enough to deploy new building technologies because they’re available, affordable, or expedient. We cannot compromise on the expressive, creative qualities of architecture and design, because it is in those expressions that we hold the power to shift culture and advance civilization. Cheap 3D printing and carbon-efficient mass timber buildings will remain a mere bandage on the wounds of inequity and environmental degradation, unless they’re delivered using a new design language that moves societal attitudes and preferences away from exploitation and oppression, and toward symbiosis and harmony.

This worldview is also exemplified by the winners of Metropolis’s second annual Responsible Disruptors program (“Conscious Innovation,” p. 106). The theme of migration in Rael San Fratello’s work echoes in Distance Unknown, a project by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Civic Data Design Lab, involving an unprecedented collaboration with Central American migrants to visualize their reality in an exhibition, website, and installation. Mass

timber is used as a tool for disruption in DLR Group’s prototype hospitality building to shake up a sector not particularly known for thinking beyond profit margins. Both projects aspire to change mindsets—with some success. Distance Unknown has influenced the draft of a U.S. immigration bill and proved a catalyst for new kinds of conversations between diplomats at the United Nations.

With such exemplars before us, let’s relegate our fetish for world-saving technologies to nostalgia. New software, materials, and construction methodologies are the means to express our convictions. By changing minds and not merely methods, we can build a more just and harmonious world.

—Avinash

OUR JOURNEY TO CARBON NEUTRAL, WITH KEILHAUER

Metropolis is committed to assessing and reducing its carbon emissions, with the goal of attaining carbon neutrality.

Our first step is a yearlong partnership with Keilhauer to offset all estimated carbon emissions for the printing and distribution of every print copy

of Metropolis in 2023 with verified carbon credits, including the one you hold in your hands. We are inspired by Keilhauer’s leadership in sustainability, the company’s work towards Closed Loop Manufacturing, and the commitments of the Planet Keilhauer program.

COURTESY CENTRE POMPIDOU–METZ IN THIS ISSUE

Rajagopal, editor in chief

More than 11 miles of glue-laminated timber were used to construct the roof structure of the Centre Pompidou-Metz, designed by Shigeru Ban. The Japanese architect is renowned for structural innovation with wood.

METROPOLIS 18 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

THE SOUND OF DESIGN

Slender yet durable, the VLA26 Vega Chair was originally created for Copenhagen’s historic concert hall, Vega. Many decades after its debut, Carl Hansen & Søn proudly launches Vilhelm Lauritzen’s functionalist masterpiece with meticulous attention to craftsmanship and detail.

CARLHANSEN.COM Flagship Store, New York 152 Wooster St, New York Flagship Store, San Francisco 111 Rhode Island St #3, San Francisco Showroom, New York 251 Park Avenue South, 13th Floor, New York

VLA26 Vega Chair by Vilhelm Lauritzen 1956

THINK TANK™

Through an online experiment with the panelists, IA’s designers proved it’s hard to find distinctive references on social media platforms that reinforce visual homogeneity.

Resisting Social Media Sameness

A Think Tank panel guides designers through strategies to break the algorithm.

Most designers consider social media—especially Instagram and Pinterest—a crucial part of their research and marketing efforts. But what if social media and its algorithms create sameness in design, inspiring the same aesthetics in Berkeley and Bangkok?

A Think Tank conversation on September 29, hosted by IA Interior Architects and moderated by Metropolis editor in chief Avinash Rajagopal, sought to address ways designers can leverage social media to break through to new audiences and boost social equity.

“Use social media as a tool,” implored Alexandria Davis,

designer at the host firm. “Let it be a supporting actor, not the lead.” Her colleague, design director John Capobianco, reminded the audience: “Listening is the most undervalued skill in the profession. If we can’t listen, then we can’t understand.”

Suzanne Tick, founder of Tick Studio, summed it up neatly: To succeed both online and in the real world, “be more physical and human and less digital.” Getting back in touch with human sentiments is good for variety and diversity in spaces, and for healthier design practices overall. —James

McCown

METROPOLIS 20

Healing Begins with Listening

Exploring design empathy in health-care spaces

In designing spaces for health care, nothing is more important than empathy. That was the premise of the Think Tank panel Rajagopal moderated on October 6.

“Empathetic design is all about listening and engaging,” said Christina Yates, senior associate and lead interior designer at host firm NBBJ. Her colleague Jonathan Ward, partner and firm-wide design leader, concurred, adding: “It’s about listening and collecting everybody together, collecting ideas, and finding the best solutions through that process.”

Empathy is key to achieving equity in the design of health-care spaces as well, pointed out Angelita Scott, director and community concept lead at the International WELL Building Institute, and one of the minds behind the new WELL Equity rating. She cited the sobering statistic that Black women see rates of maternal mortality—those deaths related to pregnancy or childbirth—almost three times higher compared with their white counterparts.

Acknowledging that racial disparities in the healthcare system are a reality “is really key to creating equitable health-care spaces,” she concluded. —J.M.

Reinventing Design Practice

The experts weigh in on what to do about interior design’s massive waste problem.

We’ve all seen it: A company will occupy an office for a scant five years and then decide to relocate. In the process virtually all the furniture and fittings of the existing space are trashed, and brand-new ones bought for the Taj Mahal that clients are about to move into. What a waste!

On October 13, Rajagopal moderated a Think Tank discussion titled “Reinventing Design Practice,” hosted by Studio O+A in San Francisco, that called on designers to rethink this shameful model.

“Furniture is thrown out with the baby and the bathwater, and along with everything else goes into the landfill. We need to change that quickly,” said Studio O+A cofounder Verda Alexander. “We need to take risks. We need to be willing to get uncomfortable.”

Kriss Kokoefer, president of Kay Chesterfield Inc., a contract furniture reupholstery company specializing in refitting and reusing office furniture, posited that even simple changes can have a big impact.

“Reupholstering is actually a really fun and creative way to be sustainable. There’s a long-term goal of keeping really well-made furniture that can last many lifetimes.” —J.M.

FROM TOP: COURTESY NBBJ; COURTESY STUDIO O+A

To combat waste in the commercial interiors industry, designers have to get creative with new ways to reduce, reuse, and recycle products and materials.

Above: O+A’s design for the Stevenson School in Pebble Beach, California.

NBBJ’s design for the Ohana Campus in Monterey, California. More and more health-care designers are embracing green space as a design strategy to reduce stress and improve patient outcomes.

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 21

The Think Tank discussions were held on September 29, October 6, and October 13. The conversations were presented in partnership with Garden on the Wall, GROHE, Mannington Commercial, Ultrafabrics, and Versteel.

What makes an architecture and design practice unique? How do firms and offices develop areas of expertise, deep insights, and passion projects? Metropolis editor in chief Avinash Rajagopal sat down with 20 firms in 2022, speaking to practitioners about what distinguishes their work. Here are nine architecture and design leaders on what gives them their edge.

© CREDITS GO HERE

METROPOLIS 22

Scan to watch the Leading Edge videos on DESIGNTV by SANDOW

Designing Hospitality Spaces That Transport Us

What does it take to design hotels and restaurants that operate seamlessly and are also endlessly inspiring? Every project New York–based GOODRICH creates utilizes the firm’s four Design Foundation pillars: Historic, Familiar, Aspirational, and Muse.

“We strive to make each project a completely unique experience rather than approaching the design from our own style or aesthetic point of view. We work to discover the ideal expression of a project—and that requires a lot of research into the site or the building or, more broadly, the neighborhood, city, or country the project is in.

One of the reasons you sense depth in our final designs is that we immerse ourselves as much as possible in all the different contexts of a space. We read novels, learn history, and walk the neighborhood to find these different stories. Then when we build that research into a place, we end up with a design that has multiple layers for guests to discover.

It’s very tempting to say, “What’s the design culture here and how do we reflect that back to the place?” We work hard to do our research more laterally so that we’re learning about a movement, time period, or layer of recent history that may be lost to contemporary eyes and minds. Then we consider how to bring the different things we’ve discovered through research together to create a design language that will both make the project unique and rich, but also will bring forward stories or histories that even locals might not be familiar with.

For every project we do, we have a Design Foundation comprising four different pillars. We have a Historic pillar that’s related to the history of the site or the location. We have a Familiar pillar, which is a cultural component, something that our guests might know from literature, cinema, or pop culture. We have an

Aspirational pillar, which is often heavily guided by what the owner, operator, or client hopes to create. And then we have a Muse for every project, which is a slightly discordant or contrasting point of view. For each project, these four categories are always the same, but we find unique inspiration that drives each one.

The most important thing is that guests feel as though they cross a threshold when they enter into one of our spaces. And while I would love it if they would immediately start

to see the thought and research that went into creating the design, the way our team thinks about it is that it doesn’t matter why they have the feeling. And, in fact, it’s much more powerful if guests’ awareness simply shifts and they think, “I’ve arrived at someplace special and different.” We’re successful when guests are transported—and then we hope they have some curiosity about what it was that made them feel that way. –Matthew Goodrich, founder and principal, GOODRICH

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH GOODRICH GOODRICH.NYC

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 23

UBS Arena at Belmont Park, Elmont, NY

Prioritizing People and Community in Spacemaking

International architecture, interiors, and masterplanning studio Woods Bagot has been delivering design solutions alongside clients, communities, and other creatives for over 150 years. Their dedication to progressive thinking and innovation results in outcomes that inspire users and break new ground. With 17 studios across six regions, their global reach and unique multidisciplinary approach allow Woods Bagot to create human-centric design that resonates with what’s going on in the world today while anticipating the needs of tomorrow.

“Woods Bagot’s ambition is to create a truly global business framework. What we mean by global is different than what a lot of people think. We are made up of an international collective of over a thousand people in 17 studios with many cultures, and many languages, but at the core of our model is the thesis of our Global Studio. It’s not about a founder per se, it’s about a foundation—and human-centric design drives us.

Today, we believe that architecture is in a position of crisis; it needs to recreate a whole new identity focused on ethics and people. Our industry can’t keep doing what it’s done up to now: just assume that if we build brickand-mortar spaces, people will continue to clumsily occupy them. Woods Bagot’s global footprint allows us to create hybridized sectors and really analyze how humans use space from the inside out and then back inside again. We deliver a diverse range of work around the construct of total design, an iterative and multidisciplinary approach to user-centric design. We have architects, interior designers, urbanists, anthropologists, change managers, and consultants all trying to move beyond conventional approaches to architecture to bring new, multifaceted thinking to problemsolving. We’re identifying issues and then looking at them through non-traditional lenses, not always architectural and built environment ones. About 10% of our people are non-practicing architects—and it makes us

very proud that they can not only contribute but also challenge, provoke, and encourage us to always do great work.

One of the interesting things about the last couple of years is that people now have more freedom and choice; they don’t have to come into the work every day and they can pick up and move to other cities. This has created a condition where our clients have had to go back to basic principles about the value proposition of what we’re doing. What’s going to attract people to come to this building or office space, or to buy in a particular residential building? We keep pushing to find the best solutions that answer the needs of today while predicting those of the future to create something new.

The diversity and richness of our work is critical to our portfolio. We never have two projects that look the same. That’s why our design aesthetic, in a way, is amorphous. This creates a condition where anything is possible–something that we as thinkers and designers all really enjoy.” —Nik Karalis, CEO; David Brown, principal and regional design leader for North America; and Krista Ninivaggi, principal and interior design leader, Woods Bagot

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH WOODS BAGOT WOODSBAGOT.COM

METROPOLIS 24

Over/Under Kiosks, New York, Courtesy Woods Bagot

Designing Gardens as Places for Living

Can a garden be more than a pretty place to stroll through? Can it restore our relationship with nature? Los Angeles–based landscape design firm Viola Gardens uses an approach called permaculture to influence how people and their gardens grow together.

“Most people think of a garden as something outside of themselves. When we’re designing, we’re looking for ways to help people find a part of themselves in the landscape. I work with people to understand who they are so we can optimize their engagement with creative solutions because a garden is a place for living, not a place for looking at.

Whether you’re experiencing fruit blossom into something that nourishes you or watching the birds and butterflies—witnessing the relationship that our garden has with the bigger world around us is magical. Permaculture is a design system based on these relationships in nature. For example, as landscape designers, we use a diversity of plant species that are curated, and hopefully artistic and inspiring.

But we also use a diversity of plant species because diversity fosters balance. If you plant all of one thing in a landscape, you create the conditions for fungus or other types of disease. We think of a plant as something that, yes, we experience or something that creates beauty, but at the same time is in relationship with a whole host of other species that keep the system in balance.

I use permaculture as a designer and a contractor and a builder, but equally it can be used in our legal and education systems. The more I’ve come to understand these principles and embody them, the more it’s illuminated my life, strengthened my relationships, and informed how I’ve built my business.” –Jessica

Advancing the Culture of Architecture

Known for fusing radical technology and dramatic use of natural materials, Enter Projects Asia emphasizes sustainability and tactility in its projects. Advocating for a connection with the arts and crafts community, the firm seeks to keep the trades alive through its modern approach to back-to-basics design.

“Eco chic is the new luxury. People want tactility; they want nature. They want all those things that we have available to us in Southeast Asia. Knowing where things are from is the new design currency. It’s incredibly important as designers to know where things are from and make alliances with communities—to go a little bit further than ordering from a catalog or online.

Originally, architects or designers, when they were designing cathedrals, would talk to the brick mason, the astrologer, the astronomer, and the engineer, and run a more vertical

infrastructure. Now, we tend to subcontract a little bit too much. I think the whole industry needs to become more vertical, meaning that designers need to get involved more in the grassroots. While we’re the designers, we’re also working intimately with the fabricators, working with on-site deployment, and in some cases even shipping and making componentry.

We are known for our work with rattan and natural materials but also our digital fabrication methods—right now, we’re working on a new thing, 3D printed coral for a resort in Malaysia.

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH ENTER PROJECTS ASIA ENTERPROJECTS.NET

It’s about educating people and coming up with alternatives that enliven the arts and crafts industries. In Southeast Asia, we’re fortunate that those industries are alive and well, when in other places they might not be.

Our projects are keeping the trades alive and preventing the biggest competition to us, which is the threat and the importation of cheap, inferior plastic products. These products have consumed the design industry, and it’s time to go back to basics.” –Patrick Keane, director, Enter

Projects Asia

Viola, founder, Viola Gardens

IN PARTNERSHIP

Viola Gardens Design Studio, Los Angeles

WITH VIOLA GARDENS VIOLAGARDENS.COM

Spice and Barley; Bangkok, Thailand

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 25

Breathing New Life into Old Spaces

Just a year after its start, npz studio+ began on a 2-millionsquare-foot project, Bell Works, a reimagination of Bell Labs in New Jersey. Specializing in interior design and creating experiences, the firm continues the legacy of the historic building with nods to the past but reactivates the space with flexible design and events.

“Bell Works is the reimagination of the former Bell Labs laboratories designed by Eero Saarinen. It was a process. I started with the café to bring life into the building. My mindset is very global, and I thought about the coolest markets in the world that are always bustling. I gave it a very simple look with string lights, and it worked. People started coming into the building, sitting on the couch, bringing their laptop, and enjoying the space. Then I started designing the offices, and one thing led to another, and an anchor tenant came in. It’s been a nice process, layering and giving a space life little by little.

Working with developer Inspired by Somerset Development, my company npz studio+ started as the interior design firm on the project but then my role organically evolved into the Lead Designer and Creative Director because, for me, it’s all about the brand—the design, the events, the space, and the social media. I also know that energy comes with people. You can have a beautiful space and design, but the people are what complete the space. We have live entertainment, farmers markets, wellness events... simple things like that bring energy and, as a

result, cultivate a community. When everything is connected to the five senses, that’s when people enjoy and feel connected to a space. I do a lot of research on a building’s history. It’s important for me to investigate what happened there, and then think of the innovations of today. When I started on Bell Works, I noticed the building was designed for collaboration. Saarinen was a forward thinker. The hallways were designed for you to have serendipitous encounters with your neighbors, which made me realize that I needed to create offices that felt good and gave people that community feel, that sense of belonging. It’s very important to keep that legacy, to connect everything to the past and then take it to the future.

I see how people appreciate the design of Bell Works. If you walk in on any given day, there are people just walking around with strollers, friends meeting for a glass of rosé, yogis heading out after their class, or colleagues meeting for a coffee. We are open to everybody because—dogs, people, art— those things give life to the building in a simple but beautiful way.” –Paola Zamudio, founder and head

designer, npz studio+

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH NPZ STUDIO+ NPZDESIGN.COM

METROPOLIS 26

Bell Works, New Jersey

Creating Environments That Speak

ZEBRADOG specializes in designing signature stories into built environments. Experiencebuilding experts, they tap into emotions and engage all senses to create environments that hold our attention and build brand loyalty in a world of digital noise.

“Today we’re living and working in an Experience Economy. Over the past two centuries, our world has transitioned from an agrarian economy to an industrial economy, to a goods and services economy—and now our services are simply props on the experiential stage. In the experience economy, we must deliver our services as theatrical experiences to deepen an emotional connection to our customers.

ZEBRADOG is deeply engaged in the physical design and delivery of stories in built environments. As a Certified Experience Economy Expert (CEEE), I’m working to identify and share with our clients what it means to go beyond delivering a professional service to delivering an experience. We define an

experience as a memorable event that engages each individual in an inherently personal way. We help people create memories that attach themselves to a brand promise.

Daily digital chaos measures success through views of seconds spent and click-through engagement. Time well spent is part of our success measure equation. We focus on the time we have you as an audience and use time as a currency. We want you to touch things. We want you to be engaged. The more we can engage all the senses, the more successful we’re going to be in delivering time well spent.

Current data suggests that Americans spend 87 percent of their lives indoors. There is an enormous responsibility in designing the

experiences people have in that time. In making places “matter”. Time is our least renewable resource. We have little of it to share and when we do choose to spend our time somewhere it’s because we trust the environment and people within it. We help build trust in the stories we design.

The more time you spend absorbing a real story, the deeper your emotional connection will be to creating a real memory in that place. We want you to linger, put your phone down and simply be in a place, participating in a designed experience connecting to the people and the stories they’re telling. We don’t necessarily remember the places we go but we do remember the memories made ther e. We conspire arm-in-arm with the architect, interior designer, and owner to bring passion to the built environment, to give their place a voice.”

–Mark Schmitz, founder, ZEBRADOG

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH ZEBRADOG ZEBRADOG.COM

The College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at North Carolina State University; Raleigh, NC

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 27

Livsreise (leaves-rice-ah) “Life’s Journey” Norwegian Story Center; Stoughton, WI

Building to Foster Human Connection

Atlanta-based TVS makes a big impact designing buildings to support the future of our cities. Each year, more than 240 million people interact with the firm’s work, which includes large-scale public assembly buildings like its renovation of the Javits Center in New York.

“TVS is a unique firm down in Atlanta, Georgia, with a unique specialty: we do large, complex and bespoke buildings all over the world. We’ve done the four largest convention centers in North America, the largest in India, the largest in Central America, and four of the five largest in China. We make a massive impact from a small footprint.

Having this influence through big public assembly buildings where people graduate from high school, get engaged, go see a concert, or go learn something, is what drives what we do. It’s what gets us out of bed in the morning. It’s what attracts people to come and work with us.

Designing the Javits Center expansion in New York, for example, was a dream. It’s originally an I. M. Pei design, an iconic building in the industry, so we were very motivated to create a dialog between the building and the expansion,

to make them complement each other.

The expansion was on the forefront of a lot of trends in the industry, taking a building that was primarily a trade show and exhibition center, and adding flexibility with small spaces, big spaces, meeting rooms, and banquet halls where people could meet formally or informally. It’s also designed as a place for gathering in the event of an emergency. Its independence from the grid allows the building to be a hospital or a vaccination center like it was during COVID.

The green roof on this project is not only something to look at but something productive: it’s a farm and a habitat to dozens of bird, bat, and insect species. As an architect, you try to minimize the impact your building has, but something that improves the ecosystem is a really interesting innovation. The intersection of sustainability and design is intriguing. You don’t want to create a building

that has all the sustainability bells and whistles but that everybody hates. Then they just want to tear it down. That’s how the approach to sustainable design has matured. Javits is a great example of how you make a building that is exceptional from a design and functional point of view, but also from a sustainability point of view.

Javits is so many things to so many people. But buildings like this are gathering places first and foremost, and for people with many different motivations, whether it’s to do business, find political consensus, or to have a drink with a view of the river at night. Ultimately, it’s about coming together. The more that our day-to-day life is remote, the more essential it is to be face-to-face, hug somebody, shake someone’s hand, learn something new, and be inspired. And that’s what these buildings do.”–Robert Svedberg, FAIA, principal, TVS

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH TVS TVSDESIGN.COM

METROPOLIS 28

Javits Convention Center Expansion, New York

Leveraging Research to Push Design Boundaries

Can design be a way of understanding people and spaces better? Multidisciplinary building design firm Cushing Terrell uses continuous research to create offices, schools, hospitals, and homes that exemplify what is possible through design.

“We have a design philosophy of ‘where design meets you,’ which means we’re always focused on the end user. As a firm, we apply this within all the markets and disciplines that we work, looking at how people are impacted by things like lighting, air, materials, and space when they all are combined. When we take this holistic approach is when we really elevate design. We like to say that our design process begins and ends with research. At the beginning, we might start with an informal charrette

session. We also partner with universities. For example, we’re currently partnering with the University of Texas to establish some tangible metrics within the unique intersection of design and psychology. Vibe Maps, which are also one of the first steps in our process, absolutely start with research. We look at the site daylighting, views to nature, the core location, and circulation. Then we analyze and identify—based on building features, geometries, and elements— buzzy and focus zones within a space.

WITH CUSHING TERRELL CUSHINGTERRELL.COM

But one of the most informative tools that we have in place is our post-occupancy evaluation process, which helps us gain actual data about the way that spaces we designed are being used and how they perform. These evaluations give our teams a wealth of knowledge that not only helps that client, but the next client. It gives us a bank of research and knowledge that we can leverage on any project going forward.” –Sandi Rudy, associate and director of interior design, Cushing Terrell

Putting People at the Heart of Sustainability

What makes a super sustainable building feel like home?

River Architects PLLC creates poetic, comfortable spaces that are also at the forefront of energy efficient and climate sensitive design.

“We’re innate problem solvers. And one of the urgent problems, of course, is climate change. Sustainability is critical to us, and we’ve got to create architecture that’s appropriate for the time.

We’re always working to address the needs of the clients. We want people to love the buildings they’re in. We have a very collaborative approach and believe that sometimes even a misunderstanding can lead to a great idea.

We make sure that people remain at the core of our thinking around sustainability. The technology that brings about passive house is sort of the back of house production that people don’t need to see but the result is compelling architecture. We use sustainability as a design tool to solve problems for people. It’s all about the people and the planet.” –Juhee Lee-Hartford, managing principal, and James Hartford, principal, River Architects

IN PARTNERSHIP

Gallatin High School, Bozeman, MT

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH RIVER ARCHITECTS PLLC RIVERARCHITECTS.COM

Rockquist Minor; Garrison, NY

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 29

At All Scales

COURTESY © KEVIN SCOTT

METROPOLIS JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 31

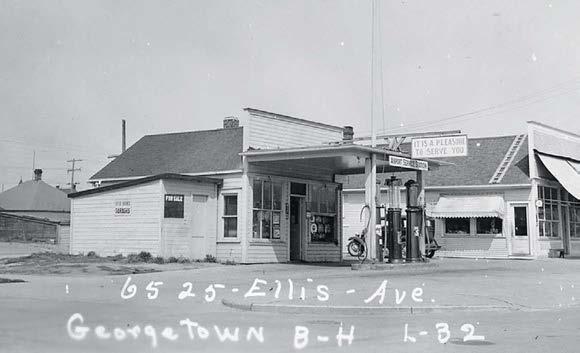

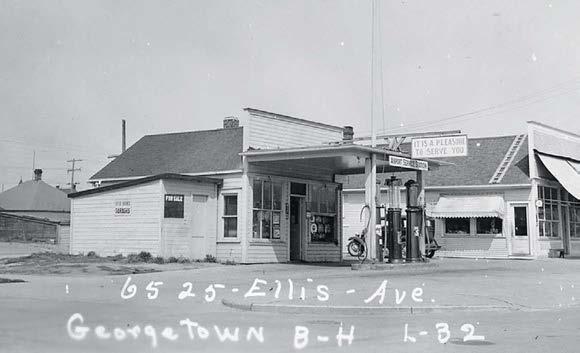

Built on the site of a former gas station, Seattle’s Mini Mart City Park, by artist collaborative SuttonBeresCuller, now hosts events for arts, culture, and environmental education—a sharp contrast to its toxic legacy as a piece of fossil fuel infrastructure.

An essential survey of architecture and design today

REUSE Creative Refueling

In Washington State as elsewhere, the relationship between cars and infrastructure is changing fast. The state is set to ban the sale of new gasoline-powered vehicles by 2035, and the question of what to do with gas stations—many of which are already disused—is increasingly pressing, not least because of the ground contamination often underfoot. In Seattle, an inventive, art-centric solution has emerged in Mini Mart City Park, a community-focused cultural center and 3,000-squarefoot public park that recently opened on the site of an abandoned gas station.

The brainchild of local artist collaborative SuttonBeresCuller—co-led by John Sutton, Ben Beres, and Zac Culler—Mini Mart City Park is the culmination of a decades-long journey, as the group first set out to activate a vacant building with their interactive, site-specific work in 2005. The trio set their sights on a 1920s-era fueling station in the city’s south end and worked with local firm GO′C to devise plans for a new facility after discovering that the existing structure was unsalvageable. “There was a naive optimism on our part about what it would take to remediate the site,” recalls Culler. “But we jumped in with both feet.”

“We knew from the beginning that ongoing remediation of the site was going to be a large part of the project,” says Jon Gentry of GO′C, who along with GO′C founding co-partner Aimée O’Carroll carried out the design. It is a nod to the familiar filling-station aesthetic of years past. Finding typical site cleanup technologies cost-prohibitive, the group worked with environmental cosulting firm G-Logics to integrate an air-sparge and soil vaporextraction system into the building’s design to clean the contaminated soil and groundwater over time.

While attending art exhibits, performances, and environmentally focused community events hosted at the park, visitors can view the air-sparge system mechanics, which use pressurized air to volatilize hydrocarbons and can remove over 200 pounds of petroleum from the soil annually. The artists hope that other communities in Washington and beyond will create their own Mini Mart City Parks. “We’ve always talked about this as a franchisable idea,” says Culler. “Wouldn’t it be amazing to activate all these derelict sites and help restore the landscape in the process?”

—Lauren Gallow

FROM BOTTOM: COURTESY © KEVIN SCOTT (2)

SPECTRUM

METROPOLIS 32 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

Mini Mart City Park in Seattle, Washington, occupies the polluted site of a former gas station. The cultural venue, designed by local firm GO′C, is an homage to the typology of 20thcentury filling stations rendered in simple, affordable materials.

The Office Unplugged. Introducing B+N’s solution for the new Hybrid Workplace: Rolling Office. Battery-driven or Plug-and-Play 120v. Easily rolled to create collaboration areas. Reconfigured without tools, without electricians, and with minimal manpower. Visit us on the web to see more inspiration and detailed information on just how Rolling Office can support the way we work now. Batteries recharge a laptop four times. Refresh with PET felt, wood, or steel. Meet Taboroid™: battery-powered, a PET felt pad, and storage. © B+N Industries Inc. Rolling Office. Adaptive. Inclusive. Collaborative. www.BNind.com 800.350.4127

THE ARCHITECTURE OF DISABILITY: BUILDINGS, CITIES, AND LANDSCAPES BEYOND ACCESS

By David Gissen University of Minnesota Press, 2022

By David Gissen University of Minnesota Press, 2022

BOOK Impaired Monuments

The issue of accessibility dominates any conversation about disability and architecture. David Gissen, a disabled designer, historian, and professor at Parsons School of Design, writes in his new book The Architecture of Disability, “Many contemporary explorations of architecture and disability focus almost exclusively on the pursuit of access: how it is achieved and how people with disabilities can be better accommodated.” Yet, Gissen notes, these “accessible” design strategies are “ultimately belittling of disabled people like me.” Why is successful accessible design so rare, and more importantly, how can architects and designers better accommodate the wide range of human ability?

Take, for example, the elevator system at the Acropolis, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that remained largely inaccessible until 2004—when Athens hosted the Olympic Games and modified construction elevators were installed on the citadel’s north face. In 2019, however, the elevators faced mechanical issues, forcing the parents of children in wheelchairs to carry both the children and chairs all the way up to the summit. It wasn’t until a couple of years ago that the Acropolis Restoration Service completed plans to make the elevators a permanent fixture. Just looking at the steep incline, it appears almost as if folks with mobility impairments

simply never visited the Acropolis. But this isn’t true. Gissen points out that ancient Athenians would have ascended to the Parthenon and other buildings via a series of ramps (which were destroyed in the first century CE), supporting an argument that the site might have actually been more accessible to disabled visitors in the past than in its present-day condition.

From the Acropolis to the American wilderness, Gissen dives into the artificial character of historic sites and landscapes, asking questions such as, Is nature innately inaccessible? Does accessible design contradict the authenticity of historical preservation? Do all people have an equal right to the city? Along the way he argues that “disability activism has the capacity to uncover and foster a deeper and more complex history beyond the problems of access to space itself.”

By recontextualizing the histories, theories, and practices of architecture through the lens of disability justice, Gissen places impairment at the heart of the built environment—rather than addressing access as an afterthought. “I want to foster practices in my discipline that emerge through impairments, not despite or as an accommodation to them,” Gissen writes, adding “The goal for disabled people is not just to enter practice but to change it.”

—Jaxson Leilah Stone

TOP LEFT: COURTESY JEROEN MUSCH; BOTTOM LEFT: COURTESY MANTHA ZARMAKOUPI, 2021 SPECTRUM

METROPOLIS 34 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

Clockwise: Detail of a tree support; an illustration from a book by architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc illustrates the human body being abstracted into a structural form; surviving fragments of the Acropolis ramp from the fifth century BCE.

TECHNOLOGY

Futuristic Formwork

Computational design and 3D-printing technology can make prefabricated concrete units more efficient to produce, but there’s a catch—all the wasted material used to make molds to shape concrete as it cures. Researchers at Gramazio Kohler Research, a program of the architecture department at Swiss university ETH Zurich, have found a possible solution with an extremely thin, 3D-printed form that can be fully recycled to create future forms.

Their demonstration project, called the Eggshell Pavilion, is a system of four columns and four ribbed slabs that can be disassembled, transported, and reassembled as needed. The pavilion’s design relies on computational algorithms that generate the architecture’s geometry in congruence with the fabrication data for the form’s 3D-printing process.

The design is then translated into a wafer-thin 3D-printed formwork of fiberglass-reinforced PET-G that is partially recycled from previous forms (three millimeters for the columns and five for the slab). “The difference between new and reused plastic is barely visible on the formworks. Such discoveries showcase how innovation can be successful in making building processes more sustainable,” wrote Guillaume Jami, a research assistant at ETH Zurich, and Joris Burger, a PhD researcher at Gramazio Kohler Research, in a joint statement. Traditional steel reinforcements are then placed inside the form before concrete is poured. The columns are made with a digitally controlled casting system that uses fast-setting concrete, while slabs are done in the traditional manner. Once the concrete is set, the form is cut off, ground into pellets, and put back into the 3D printer’s hopper to create the next set of molds.

While initial concepts are generated through sketching and traditional ideation, this digital solution, in conjunction with robotic fabrication, can produce concrete elements more efficiently than traditional formwork processes that are more labor-intensive and less cost-effective while generating more waste. “Computational design allows us to continuously evaluate our designs for their feasibility. This constant feedback helps us develop designs that could also be realized within [a shorter] time frame,” the pair explains.

—Joseph P. Sgambati III

COURTESY © GRAMAZIO KOHLER RESEARCH, ETH ZURICH SPECTRUM

METROPOLIS 36 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

Researchers at ETH Zurich developed the Eggshell Pavilion to demonstrate a 3D-printed mold for casting cement that can be recycled into future molds.

HEALTH CARE Narrative Form

You have to study the past if you want to define the future. And before completing an award-winning $14 million integrated care clinic last year for the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, Bremerton, Washington–based architecture firm Rice Fergus Miller (RFM) cultivated a 20-year history of working with the tribe’s leaders, including on the design of their resort and casino.

The tribe’s new Jamestown Healing Clinic in the city of Sequim, in the shadow of Olympic National Park, was a project with higher stakes. The 17,500-square-foot clinic treats members of the surrounding community for opioid use disorders, in addition to providing primary care, dental, and behavioral health services.

Before design began in 2019, RFM held meetings with tribal officials and the facility’s medical staff. That way, multiple perspectives guided conversations. “We looked at it from the patient point of view and kind of put ourselves in those shoes, in terms of what their experience had been in the past and dealing with their substance use disorder and how a building like this could positively impact their recovery,” explains Gena Lee, an interior designer for the firm.

Meanwhile, like other Pacific Northwest Indigenous tribes, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe takes steps to balance its history and traditions with both opportunities and challenges of the surrounding society. The clinic’s services and design were also subject to that approach.

The tribe and firm turned to tribal elder Elaine Grinnell for guidance. “She’s kind of the keeper of all of their traditional stories,” Lee says. “She started telling stories that she had learned over her lifetime.” Two narratives in particular influenced the design: One

told of how removing a stone from a stream can change its course. The other was about a journey during which a canoe was lost in the fog, and the people onshore sang a traditional song that helped guide it back to shore.

The new building expresses that spirit of a community coming together to guide those in need. The stories are manifested in curvilinear pathways that emulate the nearby Dungeness River, where headwaters flow from the flank of 7,639-foot Mount Mystery, a sacred area for the tribe.

The massing is informed by the tribe’s traditional low, long dwellings made of Western red cedar, which was also used for siding and support columns along the building’s facade. Freshly cut cedar’s natural burnt sienna hue is also an accent color throughout. Like a theater’s marquee, a five-foot-tall carving (created by Bud Turner, the tribe’s lead carver) dominates the entry.

For RFM associate principal Blake Webber, “we saw it as a strong analogy for the power of one positive interaction in someone’s journey for recovery.” —Craig Sailor

COURTESY RICE FERGUS MILLER SPECTRUM

METROPOLIS 38 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

The Jamestown Healing Clinic by Rice Fergus Miller features design that honors the tribe in Washington State who commissioned it, from carvings and colors inside (right) to the massing and cedar columns of the exterior (below).

Handmade in England

samuel-heath.com

PUBLIC SPACE A Civic Return

The building at 550 Madison Avenue (née the AT&T Building and more recently Sony Plaza) is among the more recognizable figures on New York’s skyline. Designed by architect and provocateur Philip Johnson, the 37-story skyscraper stands out thanks to its curious headgear: a classical pediment broken by a circular notch, inviting comparisons to the top of a Chippendale grandfather clock. The design was shocking when it debuted in 1979, the year Johnson appeared on the cover of Time magazine holding a model of the project, then four years from completion. It heralded the arrival of something new in American architecture: the fading of Modernism and the onset of the Postmodernist wave.

But that was then. “The building had many components changed over time,” says Craig Dykers, founding partner at the New York office of Norway- and U.S.based firm Snøhetta. “It kind of took away the original concept.” After the name changes, assorted corporate tenants, extensive interior renovations, and transformation of the street-level portico and rear-facing arcade— the erstwhile AT&T faded into the history books. Now, following its acquisition by development company Olayan Group in 2016, the building is poised for urban transformation once more.

After the Olayan takeover, Snøhetta unveiled an initial design—one with the lower trunk of the high-rise wrapped in a glass sheath—that had the opposite effect of the Time cover. Dykers’s team hashed out a revised plan with a dramatic ground-level entryway and an impressive grouping of meeting rooms, eateries, and private lounges on the second floor. There are new windows on the west-facing front and a newly cut opening at the rear of the lobby—yet the true focus of Snøhetta’s efforts is not in the building but behind it, in the north-south corridor connecting 55th and 56th Streets.

A common feature in midtown, privately owned public spaces (POPS) are mini parks constructed and operated by building management in exchange for a tax benefit. Some POPS are better than others—and Johnson’s was among the latter: a dismal corporate alleyway, lined with underused shops on one side and usually vacant chairs on the other.

Under a new glass canopy, the reconfigured gallery turns the gloomy non-place into a landscaped indooroutdoor garden, featuring native plantings, water features, ample seating, and even a “steam pit,” a circular rock-covered dais that emits heated vapor in winter and makes the space a true year-round attraction. In retreating from its original concept, Snøhetta has succeeded in doing something greater than giving one historic building a refresh; it has provided a promising model for putting the public back into POPS.

—Ian Volner

—Ian Volner

Alongside Gensler and Rockwell Group, which helped fashion the sleek new interiors, Snøhetta has transformed Philip Johnson’s AT&T Building into a more pedestrianfriendly respite for midtown Manhattan.

COURTESY BARRETT DOHERTY

SPECTRUM

METROPOLIS 40 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

Unveil the essence of immersive hi-tech design. Cosentino North America 355 Alhambra Cir Suite 1000, Coral Gables, FL 33134 786.686.5060 ™ @cosentinousa Find inspiration at cosentin o.com ONIRIKA

Designed by Nina Magon

SURFACES Pattern Play

The conventional stone mosaic gets a refreshing update in Sfera, a collection by New York–based designer Alison Rose, which can be specified for walls and floors including wet zones such as showers. Circular waterjetcut quartz layered with disks of Carrara, Calacatta, and Nero marble seems arranged randomly, but actually forms repeating triplets of stone in mixed finishes—a hallmark of Rose’s previous Bauhaus-inspired mosaic for Artistic Tile. This time, her geometric pattern play (available in Grafite, Lilac, and Verde colorways) was inspired by biological cell movement. Perhaps that’s one reason why visually the orbs appear to bounce across the surface with a life of their own. artistictile.com

—Kelly Beamon

—Kelly Beamon

Wood Wins

Geometry enlivens traditional wood paneling in new mosaic-style versions from one family-owned U.S. manufacturer. Hex Wood Mosaic wall panels are among the latest styles The Wood Veneer Hub has engineered to lend interest to both exterior and interior walls. Available in boxes of ten tile-like units, the panels measure roughly 12.5 by 11 inches, are

made from hemlock and Douglas fir, and are thermally modified at a super-high kiln temperature instead of being chemically treated to resist insects, moisture, and rot. The manufacturer also recycles its sawdust and wood scraps from the production process. thewoodveneerhub.com —K.B.

COURTESY THE MANUFACTURERS SPECTRUM

METROPOLIS 42 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

&5($7,1*�%($87,)8/�%$7+52206 0$'(�,1�7+(�86$ &86720�352-(&76�:(/&20( /$&$9$ �FRP concrete sink in sun finish metal console in matte black mirror with matte black frame faucets in matte black towel bar in matte black bathtub in matte black stool in matte black shelf in matte black NEWTERRA METALLO NEWTERRA FLOU RONDA ELEGANZA O OVALE WATERBLADE

SOURCED Craft and Context

New Rochelle, New York–based L. Bonime Design emphasizes handmade and local materials for spaces that best articulate clients’ brand identities.

Lindsey Bonime

The firm’s founder and creative director has an MArch from Tulane University, which informs her material choices in such projects as the recently completed Twelve restaurant in Portland, Maine. “I draw on my background in architecture to create warm minimalist interiors with a livable yet sophisticated sensibility,” Bonime says.

01 Hold sconce

“This sconce’s organic shape is reminiscent of a mermaid’s purse [the casing that protects a shark’s embryo] that can be found in waters off Portland’s coast.” sklo.com

02 Wall tiles

“Deep cerulean blue for a backsplash draws your eyes toward the action in an open kitchen.” artistictile.com

03 Murmuration ceramic sculpture

“This ceramic wall mural provides a minimalist yet ever-changing textural focus in a main dining space.” christinawatka.com

04 End-grain flooring

“The texture and ceruse finish result in a pattern that contrasts well with [adjacent] wide-plank oak flooring, to help define the bar and main dining area in an otherwise open space.” havwoods.com/us

05 Counter stool

“This local furniture company’s philosophy of using simple, native, high-quality materials aligned with our intent to lean into a quintessentially Maine aesthetic in Twelve.” heidemartin.com

06 Jenny wall sconce

“This playful sconce provides a sculptural element and soft, indirect light inside a simple, dark, and moody water closet.” blueprintlighting.com

07 Custom professional range commercial.hestan.com

PORTRAIT: COURTESY LINDSEY BONIME; PRODUCTS: COURTESY THE MANUFACTURERS

01 02 03 05 04 06 07 METROPOLIS 44 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

Sophisticatedly simple, yet dramatic; tasteful, yet sublime, Craft Wallcovering offers handmade surface art for your walls.

+

craftwallcovering.com

TRANSPARENCY Floor Show

By Kelly Beamon

LINOFLOOR XF2

Even with its plant-based chemistry, making linoleum generates a carbon footprint. To shrink that, Tarkett has focused on reducing the emissions associated with extracting raw materials and transporting the finished product. That effort, along with the innovative use of natural dyes, earned its latest linoleum product, LinoFloor xf2, Metropolis ’s 2022 Planet Positive Award. Here’s what it means for users.

01 BIOBASED CHEMISTRY

The chief appeal is its entirely biodegradable formula of linseed oil, pine rosin, wood and cork flour, calcium carbonate, and jute.

02 RECYCLED CONTENT

Tarkett has tweaked the recipe to source recycled content for roughly 36 percent of the raw ingredients.

03

ULTRALOW OFF-GASSING

VOCs for LinoFloor xf2 are 100 times lower than the industry standard for linoleum.

04

CRADLE TO CRADLE SILVER

This certification guarantees that the product is free from carcinogens, mutagens, or reproductive toxicants—and is linked to offsets for 5 percent of any on-site emissions.

05

FLOORSCORECERTIFIED

This label means the flooring is third-party tested for healthy indoor air quality and certified by SCS Global.

06

100

% RECYCLABLE

With its ReStart take-back program Tarkett has collected more than 112,000 tons of flooring over roughly a decade, easing the process of recycling for users and diverting waste from landfills.

07

HOSPITAL- AND KID-SAFE

The product meets Health Care Without Harm Silver requirements.

COURTESY THE MANUFACTURER

Linoleum has always been a biobased product. Now Tarkett has cut the material’s carbon and VOC emissions, making it a better flooring choice than ever before.

METROPOLIS 46 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023

Explore Metropolis's Design for Equity Primer, a guide to all existing resources to improve equity in the process and outcomes of architecture and interior design.

presented by

PRODUCTS Sleek Chic

Product debuts at this year’s Kitchen and Bath Industry Show suggest that a minimalist, hotellike residential style is here to stay.

By Kelly Beamon

By Kelly Beamon

Decades of decluttering and advice from decor magazines have led to a popular residential style that’s more hotel room than home. A review of product introductions (including some from this year’s Kitchen and Bath Industry trade show in Las Vegas) signals that won’t change soon, despite a few scattered experiments in maximalist baroque styles. The resilient minimalist aesthetic is evident in the number of compact, pared-down, low-profile, and nearly invisible offerings afoot. Meanwhile, designers are relying on bold, rich finishes to perform the heavy lifting of adding drama in the absence of fussy decorations. A case in point is Duravit’s new Zencha bath collection, which includes dark and muted wood vanities and beautifully simple sink basins and tubs. The busiest rooms in the house are doing more with less.

COURTESY MARK SEELEN

01 ZENCHA COLLECTION

METROPOLIS 48

A German manufacturer-designer partnership produced this Japanese-influenced family of vanities, washbasins, mirrors, and tubs. Duravit’s collaboration with Sebastian Herkner includes softly rectangular soaking tubs, available in 63-by-34-inch and 70-by-36-inch profiles, inspired by Japanese bathing and tea culture. DURAVIT duravit.us

ELMWOOD

To

Continuing to improve the design of its original 1996 drawer-style dishwasher, Fisher & Paykel has rolled out a version that’s more discreet, with a low decibel rating of 43 dBA and optional custom door panels for sleeker integration with cabinets.

FISHER

BLUESTAR

COURTESY THE MANUFACTURERS

03 BLUESTAR 36-INCH FRENCH DOOR

offer an affordable, custom, professionalkitchen look in standard 36-inch counter-depth refrigerators, Pennsylvaniabased BlueStar is rolling out a palette of more than 1,000 colors and ten trim options.

02 03 04 05

bluestarcooking.com

02 ELMWOOD CABINETRY “Dramatic, deep colors” is how cabinetmaker Elmwood describes some of its latest crowd-pleasing hues; all were developed based on a survey of 100 dealers and designers.

elmwoodcabinets.com

04 SPECIALTY FINISHES Linear-drain manufacturer Infinity Drain is rolling out five new on-trend finishes to expand design flexibility for its sleek drain profiles. INFINITY DRAIN infinitydrain.com

05 SERIES 11 DISHDRAWER

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 49

& PAYKEL fisherpaykel.com

Designed as a system, RainStick integrates a tiltable showerhead, foot spout, hand shower, controller, and reservoir in one slim vertical towerlike unit that can be operated with an app.

Exclusive to Atlas Homewares Stainless collection, new Matte Gold and Matte Rose Gold finishes extend options for designers specifying its 85 sleek, geometric cabinet pulls and knobs. ATLAS

Named in a tribute to Postmodernism, this collection of simple sinks in saturated, glossy colors was designed by Terri Pecora for Italian manufacturer Simas. They’re available in freestanding, countertop, and wall-mounted versions.

COURTESY THE MANUFACTURERS PRODUCTS Sleek Chic

06 DRAWBAR Designed to disappear like other offerings in Dometic’s interior appliance portfolio, this compact wine drawer cools in space normally occupied by cutlery— below or adjacent to 24-inch-wide cabinetry.

DOMETIC dometic.com

08 RAINSTICK

RAINSTICK rainstickshower.com

10 PO-MO

SIMAS simas.it

07 HIGHLAND GARDEN PLANTER This combination planter-with-trellis adds function without too much flair in residential and commercial outdoor spaces.

10 08 06 07 09

TUUCI tuuci.com

09 MATTE GOLD AND ROSE GOLD FINISHES

METROPOLIS 50

HOMEWARES shopatlashome.com

11 ALLOY COLLECTION

To add drama without distracting detail, quartz counter manufacturer Cambria has developed a line of worktops as part of its Grandeur series that feature brass and steel alloy veining.

CAMBRIA cambriausa.com

12 OCEAN PLASTIC SHOWERHEAD

Still in development at press time, this understated showerhead from Delta Faucet’s First Wave Innovation Lab adds value with eight settings and material makeup of up to 35 percent nearshore ocean plastic. Designers can follow its development at firstwavelab.com.

DELTA FAUCET deltafaucet.com

13 COOKING SURFACE PRIME Italian sintered-stone manufacturer ABKSTONE has managed to further minimize already streamlined induction cooking technology by integrating it seamlessly into the company’s nonporous counters.

ABKSTONE abkstone.com

14 OASIS COLLECTION

Robert A.M. Stern Architects designed this sculptural collection of door handles, backplates, knobs, and pulls.

ROCKY MOUNTAIN HARDWARE rockymountainhardware.com

12 11 14 13

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 51

SUSTAINABILITY Park Place

Kevin Daly Architects and Productora team up on a headquarters that models sustainability—and reflects a nonprofit’s image.

By Lauren Jones

The Houston Endowment’s new 31,718-square-foot headquarters opened to the public in October 2022. The building’s striking shade canopy and scalloped aluminum rainscreen (right and below) help cool it during summer.

PHOTO: IWAN BAAN; COURTESY KEVIN DALY ARCHITECTS

METROPOLIS 52

In 2019, Los Angeles and New York–based Kevin Daly Architects and Mexico City’s Productora joined forces to vie with 120 other firms in an international competition for the chance to design the Houston Endowment’s new headquarters. While the endowment, one of the largest private foundations in Texas, had an existing office, it was an uninviting and somber space on the 64th floor of a downtown skyscraper. “It was much like stepping into an oil and gas firm or a banking executive’s office,” remarks the organization’s president, Ann Stern. “No one wanted to visit our office, and it didn’t reflect who we are.”

The organization, which supports multiple initiatives and groups tied to parks, arts and culture, and education, needed a headquarters that felt more accessible; it also needed to be state-of-the-art, showcasing enough sustainable features to serve as a net-zero role model for the rest of the community. That imperative was more in line with its identity as a philanthropic organization than something more architecturally showy.

Meanwhile, a restrained profile would also be appropriately contextual: Houston has impressive antecedents of this type— austere buildings in verdant settings amid generous tree canopies such as a recent expansion at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Brochstein Pavilion at Rice University; and buildings that make up the Menil Collection.

The endowment’s prominent shade elements similarly exploit a wealth of greenery by filtering light and shadow from the treetops that shelter its location on a leafy edge of Spotts Park. Although it is highly visible as a lone building peeking through trees, the impact is softened by its use of dappled light, terraces, and clerestory windows. That design celebrates a local effect known as the “zoohemic” canopy, a term coined by architect Lars Lerup, a Swedish-born scholar and Rice University professor, in describing Houston’s generous landscape of trees in his 2011 characterization of it as a “suburban city.”

To capitalize on the site’s wealth of tree-filtered daylight, the canopy features louvers.

To capitalize on the site’s wealth of tree-filtered daylight, the canopy features louvers.

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 53

“Houston has a tradition of a number of notable buildings that balance this same relationship between building and park, public and private,” says architect Kevin Daly.

But while those elements help to align the building with tradition, its engineering is breaking new ground. That’s thanks in large part to consulting on sustainability by Stuttgart environmental engineering firm Transsolar. The firm was pivotal in projecting the structure’s energy performance and problem-solving within the increasingly warming site. “They have been a really strong partner in establishing a basic approach to evaluating solar control and how to manage the overall heat gain,” Daly says.

While such considerations were important to the endowment as well, the goal wasn’t to build a “big sustainable achievement” as much as present a “toolbox of possibilities” that could be adopted by the organizations it works with, he notes.

These strategies included utilizing a hybrid structure made of steel and crosslaminated timber; the combination is high-performing and similar in strength to concrete. The team also dug 300-foot-deep geothermal wells that “eject heat into the soil around the building and help warm it during the winter,” says the architect.

A scalloped aluminum rainscreen, fabricated by Kinetica in Monterrey, Mexico, minimizes interior cooling demand. The

PHOTO: ELIZABETH LAWRENCE KNOX, COURTESY HOUSTON ENDOWMENT SUSTAINABILITY Park Place

The architects’ hybrid steel-and-CLT framing solution is high-performing and a Houston first.

METROPOLIS 54

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 55

Clerestories and terraces visible from inside the main lobby area (below) add daylighting and connect the interior to green views outside.

lightweight material, while more energyintensive initially than, say, terra-cotta, was chosen for its potential recyclability. “A lot of design is now focused on strategies for making buildings completely recyclable,” Daly says. “We took the same considerations in mind for this project.” And while the project technically checks all the boxes for LEED Platinum certification (the client has chosen not to formally pursue the actual certification), gaining that recognition is less important to the architects than actually achieving carbon neutrality by 2030.

“That’s something we aspire to on all projects,” Daly says. “After the first year, the building will be energy self-sufficient year-round.”

Opened to the public in October 2022, the 31,718-square-foot, $21 million building has become a place where both endowment employees and partners look forward to meeting and continuing to work toward a better Houston. The organization’s new home is a representation of the city and its complex social structure, and it offers solutions to ever-evolving environmental changes and concerns.

“For us, building a [ground-up structure] when we had never done so before, it was incredibly important to find the right design team. Not only did they build a beautiful, sustainable building but they wanted to understand what we do. They got it right from the very beginning,” Stern concludes. M

COURTESY KEVIN DALY ARCHITECTS SUSTAINABILITY Park Place

METROPOLIS 56

Selected Sources

• Architects: Kevin Daly Architects and Productora

• MEP engineer: CMTA

• Structural engineer: Arup

• Civil engineer: BGE

• Environmental graphics: MG&Co.

• Landscaping: TLS Landscape Architecture

• Lighting: George Sexton Associates

• Sustainability: Transsolar

• Construction manager: Forney Construction

• General contractor: Bellows

• AV/IT:

4B Technology

• Acoustics: Newson Brown

• Waterproofing: CDC

INTERIORS

• Bath fittings: Toto

• Bath surfaces: Mutina

• Ceilings: Navy Island, Armstrong

• Flooring: Nora, Interface

• Furniture: Allermuir, Normann-Copenhagen, Herman Miller

• Kitchen surfaces: Corian

• Lighting: Zumtobel, USAI

• Paint: Benjamin Moore

• Textiles: Maharam

• Wall finishes: Unika Vaev

• Laminate casework: Fenix

EXTERIORS

• Cladding/facade systems: Kinetica

• Doors and windows: Kawneer

• Glazing: Tristar, Cristacurva

• Lighting: Ecosense, Selux

BUILDING SYSTEMS

• Photovoltaics: JA Solar

• Building management: Johnson Controls

• Geothermal system: Cole’s Drilling with MLN

FROM TOP: PHOTO: ELIZABETH LAWRENCE KNOX, COURTESY HOUSTON ENDOWMENT; PHOTOS: IWAN BAAN; COURTESY KEVIN DALY ARCHITECTS (2)

The second floor of the central atrium space (shown left) features clerestory glazing and artwork by JooYoung Choi. The Buffalo Bayou flexible event and meeting space (below, top) overlooks Spotts Park. The boardroom (bottom) features Kevin Daly Architects’ custom-designed furniture and white oak acoustic slats on walls.

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2023 57

REUSE Radical Repurpose

An office building in Norway is made almost entirely of scraps and demolition waste, changing the conversation around material reuse.

By Ethan Tucker

The European Commission estimates that the building industry creates around a third of the world’s waste. That’s an almost unimaginable volume of demolition debris— wood offcuts, old tile and carpet, pieces of steel, windows that didn’t quite fit, concrete rubble, and more. But viewed another way, all of that garbage is also a wealth of raw building materials waiting to take shape. Is it possible to design a building almost entirely from waste?

For Mad Arkitekter, an architecture studio founded in Oslo in 1997, the potential of reusing construction waste has been an obsession that led the firm to redesign its own offices with largely upcycled materials in 2021. When real estate developer Entra approached the firm about overhauling and expanding a 1958 office building nearby, the firm saw an opportunity to take reuse to the next level.