MRS LISA BROWN

I am delighted to introduce the inaugural edition of Meriden Muse , a publication dedicated to showcasing the remarkable talents and insights of Meriden girls. This journal is more than a collection of research papers; it is testament to the boundless curiosity, intellectual rigour, and creative spirit that define our students.

In an era where information is readily accessible, the ability to engage in deep research and critical thinking is more vital than ever. Research is not just about finding answers; it is about asking the right questions, challenging assumptions, and exploring new territories of knowledge. It is through this process that we advance our understanding of the world and contribute to the broader body of knowledge that shapes our society.

Within these pages, you will find a diverse array of research projects, as well as literary and musical compositions and artworks, that reflect the interdisciplinary nature of our community. Each contribution is a reflection of the hard work, dedication, and intellectual curiosity of our students. Their work spans a wide range of topics, from the sciences to the humanities, and demonstrates the profound impact that students can have on their fields of study.

Critical thinking, a cornerstone of scholarly research, empowers students to analyse complex problems, evaluate diverse perspectives, and make informed decisions. It encourages a sceptical yet open-minded approach, enabling students to discern the validity of arguments and the reliability of sources. In an age of information overload, the ability to think critically is essential for navigating the vast sea of data and making meaningful contributions to academic and public discourse.

Creativity, often seen as the spark that ignites innovation, plays a crucial role in research. It is the force that drives us to think outside the box, to envision possibilities beyond the conventional, and to develop original solutions to pressing challenges. Creativity leads to breakthroughs that can transform disciplines, industries, and lives. It fosters a spirit of experimentation and resilience, encouraging students to persevere in the face of setbacks and to view failures as opportunities for growth and discovery.

This journal celebrates the symbiotic relationship between research, critical thinking, and creativity.

As you explore this journal, I hope you are inspired by the passion and ingenuity of our students. I encourage you to engage with their work, to ask questions, and to consider how their findings and their creative expression might inform your own thinking.

I would like to thank the students who have contributed to this first edition of Muse, for bravely sharing their research and their creative spirit with our community, and to the teachers who lit the spark, inspiring and guiding these projects. Special thanks must also be extended to Ms Priscilla Curran, Dean of Lateral Learning and Dr Jocelyn Laurence, COLL – Research and Critical Thinking, who first floated the idea of this publication as a platform to showcase the exceptional student work they have witnessed in their roles. Together with the work of the Student Editorial Committee, this has culminated in a wonderfully curated publication.

I hope you enjoy the 2023 edition of Muse

MRS LISA BROWN Principal

Priscilla Curran and Dr Jocelyn Laurence

Critically assess historians’ differing interpretations of the most prominent cause of the expulsion of Nikita Khrushchev from power

Lael Sakalauskas, Year 12

Should there be restrictions on free speech?

Leah Har, Year 10

Explain the change and continuity between the first and second waves of feminism in the women’s rights movements in America during the 19th and 20th centuries

Which characteristics distinguish successful movements for social change from unsuccessful ones?

(Christina) Zhou, Year 9

Critically evaluate historians’ interpretations of Enver Hoxha’s leadership of Albania from 1944-1985

Seeto, Year 11

With reference to the quotation, how does Christianity guide adherents to seek transformation of self and the world?

Aurita 1, 2 and 3

Cracked Television

Kailasanathan, Year 11

Beyond the Binary: A Search for Nuance

Van Niekerk, Year 12

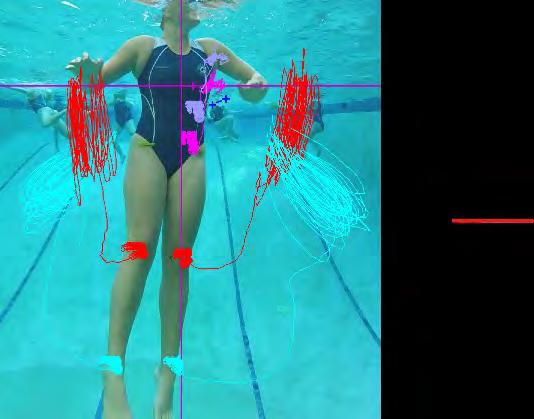

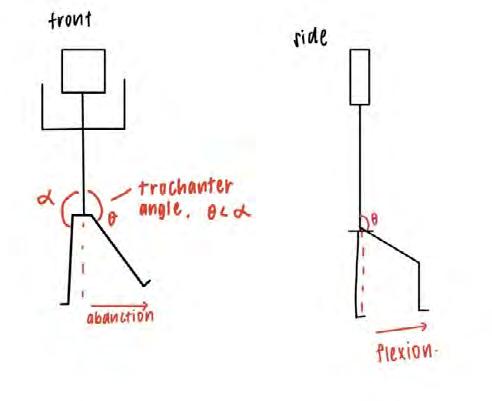

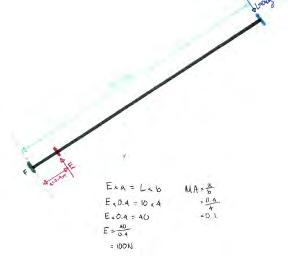

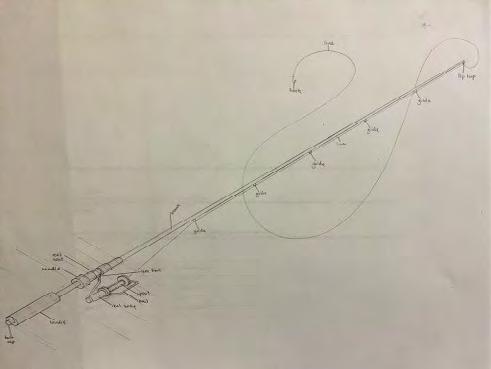

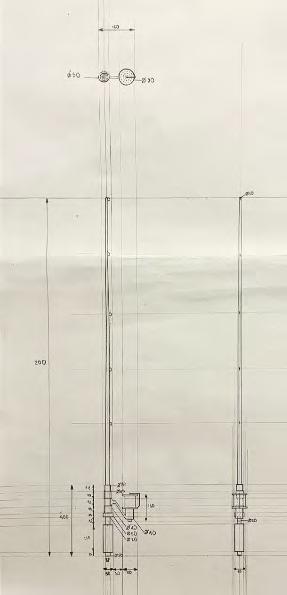

Engineering eggbeater:

An investigation of the trochanter angles effect on the height achieved by eggbeater kick over 14s in females [pilot study (Abridged)]

Anneke Dykgraaff, Year 12

Alchemy’s enchantment

Qianqi Zhou, Year 9

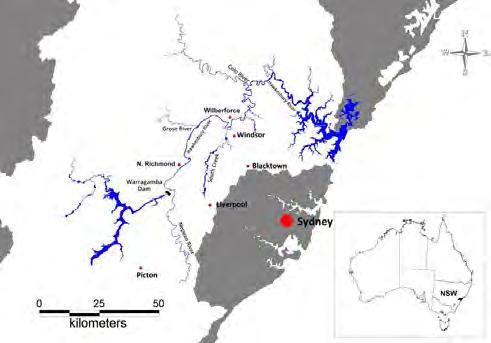

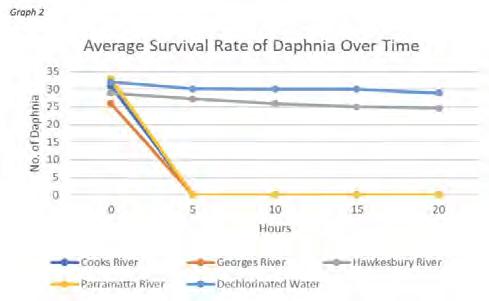

The Toxicity of Sydney Waterways

Sophie Yi and Meredith Xu, Year 10

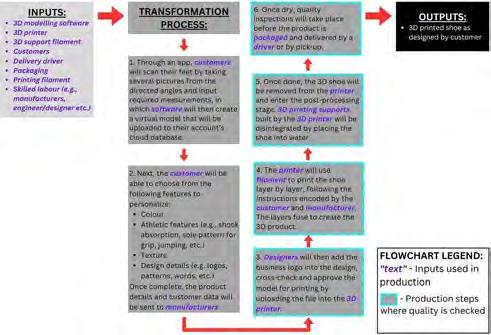

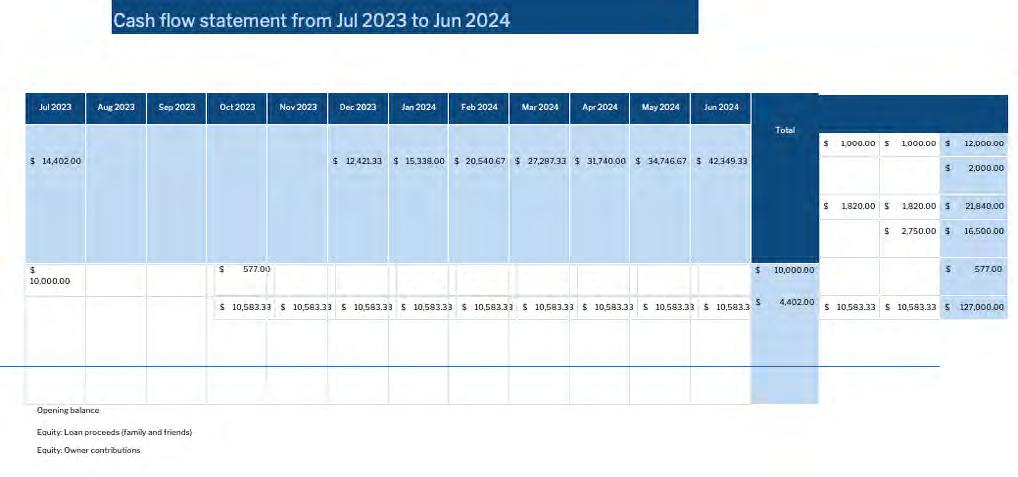

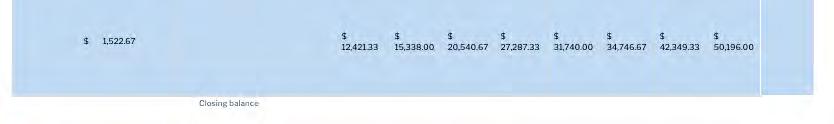

FutureFit Footwear Business Plan

Esther Yum, Year 11

The evolution of the Meriden Duck

Canice Lei, Year 10

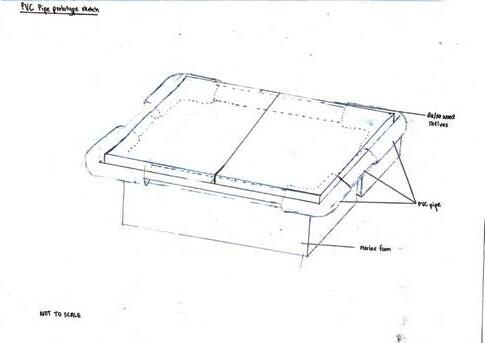

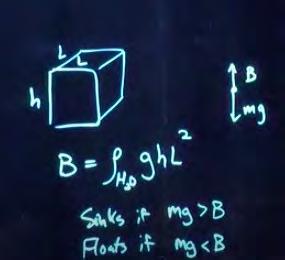

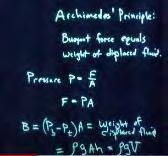

The ARK

India Whip, Year 9

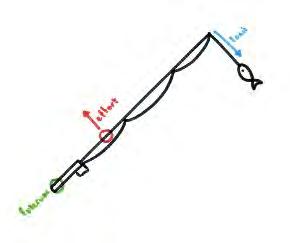

The Fishing Rod

Merryn Quang, Year 11

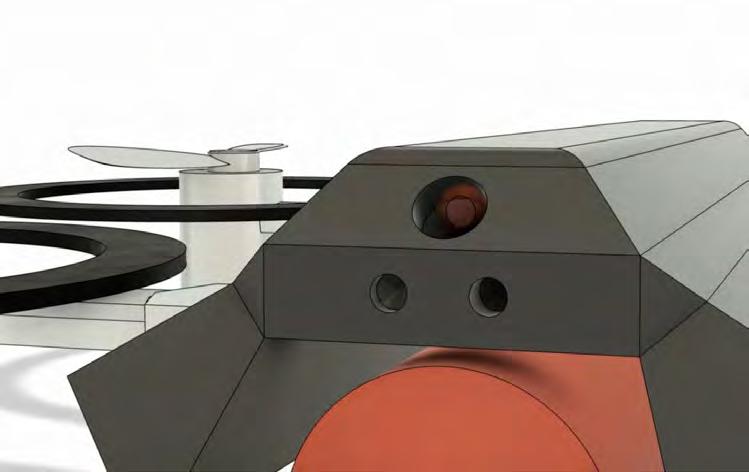

How can drones coordinate by delegating tasks in search and rescue missions to assist firefighters in a limited time frame?

Danielle Gallico and Keira Taganesia, Year 8 174

How has Lego shaped ideals and expectations of gender? A comparative study between Generation X and Generation Z

Zara Chan, Year 11

Do the effects of foreign aid contribute to economic development?

Sabrina Cao, Year 10

Should the natural habitat of species be protected from deforestation?

Amrita Wadhera, Year 10

A study of the integration of two generations of Chinese immigrants into Western culture.

Anna Liu, Year 12

Five Sectors: The Commerce Song

Alexandra Katanasho and Freya Cleary, Year 10

How does the socio-economic composition of a suburb impact the availability and affordability of fresh produce offered in its grocery stores?

Mia St George, Year 11

The Little Bird Elisya Arfianto, Year 7

Are electric vehicles a sustainable solution to reducing greenhouse

LUCINDA HARRICKS

Welcome to the inaugural edition of Muse , a journal that showcases some of the incredible work of Meriden students. Students on the Muse Editorial Committee have thoughtfully compiled these pieces to create this beautiful collection.

Our efforts in the curation of these research projects have allowed us to engage with, and grow our appreciation for, the research process. Research is a crucial skill — something that we, as students, are particularly aware of the night before a research task is due! However, its uses extend beyond school assignments. Undertaking research develops our critical thinking skills as we learn to evaluate sources, analyse findings and reach an informed conclusion. Breaking apart information into manageable pieces is a crucial step in the problem-solving process that leads us to a fact-based solution. Research allows us to critically examine and enhance our understanding of the world, guiding us toward informed conclusions. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Laurence for the guidance she has provided us as Committee members.

I hope you appreciate the many and varied research projects and other fascinating works in this journal, and the valuable insights they provide.

On behalf of the Muse Editorial Committee, happy reading.

MS PRISCILLA CURRAN AND DR JOCELYN LAURENCE

It is indeed a very special moment for us to see this publication of Muse come to fruition. Firstly, it represents the culmination of a year’s worth of dedication, curiosity, creativity and intellectual exploration by our talented students. Beyond that, it also represents for us the coming to life of an idea that we have long harboured in our roles within the Lateral Learning department. In our roles as COLL – Research and Critical Thinking and as Dean of Lateral Learning we are fortunate to see the wide range of works produced in a variety of academic disciplines. Over the years, we have discussed the idea of publishing a journal that would showcase the breadth and depth of these pieces; works that exemplify the extraordinary achievements of our student researchers, writers, innovators, artists and musicians.

The title Muse was inspired by the significance of Parnassus to Meriden’s heritage. The lilies of Parnassus feature in the school crest, and Mount Parnassus was the mountain sacred to the muses in Ancient Greece. It is these muses, who preside over the different realms of learning, be it poetry, science, history or music, that have provided the inspiration for this journal and the sections within it. The verb ‘to muse’ also means to consider something thoughtfully, and there is no doubt that all of the students who have had their work published in this journal have spent many hours in quiet contemplation of their work, researching, questioning, drafting and refining in order to produce the final product.

The works presented here cover a wide array of topics, demonstrating the varied interests and passions of our students. Many of these pieces were created as a result of the demands of the curriculum. Some are HSC Major Works and others were awarded a Gold Parnassus Award, an award at Meriden that recognises research, and critical and creative thinking at the highest level. Other works reflect the varied competitions that our students have chosen to engage in. Some works take the form of detailed research essays and reports, others use the mediums of painting, sculpture, musical scores, song lyrics and poetry. No matter the form, each piece contributes to a broader understanding of our world and showcases the intellectual rigour and creativity that is fostered at Meriden.

We are immensely proud of our students’ achievements and hope this journal inspires current and future students to embark on their own journeys of discovery and wonder.

DR JOCELYN LAURENCE COLL – Research and Critical Thinking

LAEL SAKALAUSKAS

YEAR 12, 2023

The expulsion of Nikita Khrushchev, who stands as the only Soviet leader to have been expelled from power, generated contentious debate. Khrushchev’s expulsion stimulated a particular interest in the nature of leadership in authoritarian regimes, as it challenged the formerly prevailing Western perception that the Soviet Union’s political system required an omnipotent leader.1 The debate regarding Khrushchev’s expulsion is one analysed by historians who hold competing political, personal and temporal contexts, influencing their access to historiography and shaping their perceptions of the Soviet political system, 2 thus, generating contesting perspectives.3 Carl Linden,4 one of the earliest commentators on Khrushchev’s expulsion, interpreted the event as a product of Khrushchev’s failure to attain absolute authority, based upon the “conflict school”5 of Soviet politics.6 Yet, Linden’s temporal context hindered his access to key Soviet historiography and, consequently, relied on inference to support his analysis.7 Comparatively, Soviet historian and former member of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),8 Roy Medvedev,9 gained significant access to source material that remains inaccessible to Western historians.10 Drawing on his MarxistLeninist11 ideology,12 Medvedev identified party structural changes, which threatened the stability of the Soviet political system, as the primary cause of Khrushchev’s expulsion.13 A notable shift in the analysis of the event transpired following the Soviet policy of Glasnost14 and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union.15 William Tompson,16 an historian who wrote during this period, examined the significance of Khrushchev’s broken political promises, as the most prominent cause for his expulsion.17 Hence, competing perspectives encapsulate the question of whether it is possible to discern the most prominent cause behind the events of Khrushchev’s expulsion.

1 Elwood, R. C. (1967). [Review of Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 19571965, by C. A. Linden]. International Journal, 22(4), 715–716. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40200249 p.716

2 Torigian, J. (2022). “You Don’t Know Khrushchev Well”: The Ouster of the Soviet Leader as a Challenge to Recent Scholarship on Authoritarian Politics. Journal of Cold War Studies, 41(1), 78-115. https://direct.mit.edu/jcws/ article/24/1/78/109004/You-Don-t-Know-Khrushchev-Well-The-Ouster-of-the p.80

3 Ibid.

4 Carl A. Linden is a highly educated American professor of Russian and Soviet political science, who served in the US air force intelligence during the Korean War. Prompted by the fall of Khrushchev, Linden wrote the text Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 1957-1964, published in 1966.

Taylor and Francis. (n.d.). Variety and Adventure in the life of Carl Linden https://albert-schmidt.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/33-Carl-Linden-Tribute_ PPS_2014.pdf p. 114

5 Introduced by Boris I Nicolaevsky, the conflict school questions the adequacy of the concept of totalitarianism as the most appropriate tool for understanding the inner political realities of Soviet regimes. The school perceives that the internal conflict inherent in Western, multi-party systems was similarly present within the Soviet Union.

Ibid. p. 113

6 Linden, C. A . (1966). Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership, 1957-1964. The Johns Hopkin University Press p. 206

7 Taubman, W. (2004). Khrushchev: The Man and His Era. W. W. Norton and Company. p. 2

8 Britannica. (n.d.). Roy Medvedev. In Britannica.com. Retrieved March 2, 2023 from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Roy-Medvedev

9 Born in 1925, Roy Medvedev is a Soviet scholar, historian and the son of a Marxist philosopher, purged under Stalin’s Great Terror. Between 1956 and 1969, Medvedev was a member within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, before his dismissal. Medvedev is the author of the text Khrushchev: The Years in Power, published in 1976. In reference to Medvedev’s political ideology, he identified himself as both a critic of Western capitalist societies, and a Soviet oppositionist who has publicly condemned Stalinist rule.

Medvedev, Z. A. and Medvedev, R. A. (1971). A question of madness. [e-book]. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/questionsofmadne0000unse/page/14/ mode/1up p. 3

10 Cohen, F. S. (1975, July 13). On Socialist Democracy. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1975/07/13/archives/on-socialist-democracy.html

11 Mar xist-Leninism refers to Lenin’s political understanding of Marxism; that a revolutionary proletariat class would not emerge automatically from capitalism but rather, that there was a need for a professional party to lead the working class in the overthrow of capitalism.

New World Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Marxism-Leninism https://www. newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Marxism-Leninism

12 Medvedev, R. (1978). Khrushchev: The Years in Power. W. W. Norton and Company. p. 152

13 Ibid.

14 The policy of Glasnost is most closely translated as “openness” and refers to the removal of information constraints in the Soviet Union, allowing freedom of media, embracing of criticism and decreasing censorship. The period of Glasnost, between 1986-1991 is often linked to a period of increased thought, with a widening of Soviet public discussion of both foreign and internal policy issues. The RAND Corporation. (1990). Glasnost and Soviet Foreign Policy https://www. rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/notes/2009/N3008.pdf p. 36

15 Torigian, J. (2022). Op. cit. p. 80

16 William J. Tompson is a highly educated professor of political science in both the United States and the United Kingdom. In 1995, he published Khrushchev: A political life, the first English biography of Khrushchev to make use of Soviet sources, and since, has written prolifically, on Soviet political leaders and the current Russian Federation.

Tompson, W. (n.d.). Curriculum Vitae https://oecd.academia.edu/ WilliamTompson/CurriculumVitae

17 Tompson, W. J. (1994). Khrushchev: A Political Life. Palgrave Macmillan London. p. 266

Linden18 proposed that the absence of an institutionalised system of succession, in the post-Stalin era,19 had implications for Khrushchev’s capacity to successfully consolidate his power, resulting in his expulsion.20 Due to the lack of a welldefined mechanism for resolving disputes of authority21 within the presidium, 22 Linden concluded that conflict within Soviet leadership increased in prevalence, 23 irrespective of Khrushchev’s rise to high office, or the defeat of the “anti-party” 24 group.25 McAuley similarly identified that, following Stalin’s death, conflict emerged within the leadership.26 Thus, Linden maintained that Khrushchev was unable to secure his position as an absolute leader, 27 and was rather engaged in a constant

struggle to maintain and extend his authority.28 While Linden dismissed Khrushchev’s erratic style of leadership as more of a “pretext than a real issue”, 29 he diverted attention to the Cuban Missile Crisis30 and the disintegration of Soviet authority over Eastern Europe.31 Such circumstances placed Khrushchev in a position of vulnerability,32 undermining his ability to overcome ever-present opposition.33 This granted Khrushchev’s opponents the opportunity to consolidate and broaden their own power, ultimately culminating in his expulsion.34 Ergo, Linden argued that Khrushchev’s expulsion was not preordained, but rather, “an outgrowth of an on-going conflict” by which Soviet politics was characterised.35

18 See footnote 4.

19 Hanak, H. (1967). [Review of Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership, 19571964., by C. A. Linden]. International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), 43(4), 759–760.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2612849 p. 760

20 Holm, K. C. (1967). [Review of Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 19571964, by C. A. Linden]. Naval War College Review, 19(9), 128–129. http://www. jstor.org/stable/44640988 p. 129

21 Conolly, V. (1968). [Review of Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 19571964, by C. A. Linden]. The Slavonic and East European Review, 46(106), 261-262. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4205967 p. 262

22 The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, now known as the Politburo, was a 7-member group with the purpose of deciding on urgent matters of the state. It was established as the most decisive and influential structure in the Soviet Union. The Cold War. (2020, September 26). Structure of USSR – Cold War Documentary [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qNnyfziopko

23 Linden, C. A . (1966). Op. cit. p. vii

24 The anti-par ty group was responsible for an attempted ouster of Khrushchev in 1957, led by Viacheslav Molotov and Lazar Kaganovich, who accused Khrushchev of promoting a cult of personality and acting irresponsibly. The attempt was unsuccessful due to the support of the Central Committee. Consequently, Khrushchev’s opposers were named the “anti-party group” and forced to resign, removing Khrushchev’s opponents from positions in office and supposedly strengthening his stability within Soviet leadership.

Siegelbaum, L. (n.d.). The Anti-Party Group https://soviethistory.msu.edu/1956-2/ the-anti-party-group/

25 Rush, M. (1968). [Review of Khrushchev: A History of Postwar Russia; Beginnings of the Cold War; Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 1957-1964, by M. Frankland, H. Schwartz, R. W. Pethybridge, M. F. Herz, and C. A. Linden]. Slavic Review, 27(3), 492–494. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2493357 p. 493

26 McAuley identified that while the party became the dominant institution over the secret police, army and ministries, the decade following Stalin’s death saw contending perspectives over policy towards the economy, agriculture and foreign affairs. For example, initially, Malenkov, who assumed chairmanship of the Council of Ministers, advocated for an economic policy, laying emphasis on consumer durables, while Khrushchev questioned the neglect of agriculture. As policy positions became identified with individuals, there remained a lack of unity towards a common policy programme.

McAuley, M. (1992). Soviet Politics 1917-1991. Oxford University Press. p. 63

27 Rush, M. (1968). Op. cit. p. 493

Linden’s interpretation of Khrushchev’s expulsion was constructed in terms of his objective,36 and his adherence to the conflict school of Soviet politics.37 Linden reflected on the intention of his text, saying it was not a history of the Khrushchev era, but rather that he aimed to use Khrushchev “as a vehicle” to reveal the nature of Soviet politics.38 According to Bell, understanding the nature of the Soviet regime is crucial to effectively evaluate Khrushchev’s expulsion, as Soviet events, “cannot be defined outside of the context of Soviet politics”.39 However, while Linden’s aim is evidently valid, it imposed a distinct partiality to his argument, intending to investigate no further than the political system in which Khrushchev operated.40 Alternatively, Linden’s political ideology on the conflict school,

28 Butler, W. E. (1967). [Review of Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 1957-1964; Soviet Policy-Making: Studies of Communism in Transition; Soviet Economic Controversies: The Emerging Marketing Concept and Changes in Planning, 1960-1965; Central Asians Under Russian Rule: A Study in Culture Change, by C. A. Linden, P. H. Juviler, H. W. Morton, J. L. Felker, and E. E. Bacon]. World Affairs, 129(4), 275–278. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20670857 p. 278

29 Linden, C. A . (1966). Op. cit. p. 207

30 Ibid. p. 206

31 Butler, W. E. (1967). Op. cit. p. 278

32 Ibid.

33 Linden, C. A . (1966). Op. cit. p. 206

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid. p. 2

36 Elwood, R. C. (1967). Op. cit. p. 716

37 See footnote 5.

38 Elwood, R. C. (1967). Op. cit. p. 716

39 Bell, D. (1958). Ten Theories in Search of Reality: The Prediction of Soviet Behavior in the Social Sciences. World Politics, 10(3), 327–365. https://www.jstor. org/stable/2009491 p. 350 cited in Linden, C. A. (1966). Op. cit. p. 8

40 Butler, W. E. (1967). Op. cit. p. 278

Critically assess historians’ differing interpretations of the most prominent cause of the expulsion of Nikita Khrushchev from power | LAEL SAKALAUSKAS YEAR 12, 2023

a product of his temporal context,41 offered unique insights into Khrushchev’s expulsion.42 Contrary to what Linden referred to as the “conventional school”,43 he aligned himself with the conflict school,44 proposing that Soviet leadership is a scene of “perpetual conflict behind a monolithic façade”.45 This theory directly supported Linden’s perspective that Khrushchev’s fall was a repercussion of the conflict in which he operated.46 Yet, while Linden’s ideology exerted a unique, “neo-enlightenment” understanding of international politics and history,47 Ali stated that, “whenever history is written under the influence of an ideology, its objectivity is sacrificed”.48 Thus, Linden’s political alignment significantly influenced both the scope and impartiality of his argument regarding Khrushchev’s expulsion from power.49

Published in 1966, two years post-Khrushchev’s expulsion, the efficacy of Linden’s text is limited by his temporal context 50 and lack of foresight. 51 In coherence with his aim, much of Linden’s research was dedicated to comprehending the workings of totalitarian and Marxist-Leninist regimes, granting him fundamental contextual understanding. 52 However, considering his temporal context, Linden’s access to Sovietbased historiography was finite, reliant upon Soviet published texts, 53 whose breadth was limited to political dictionaries

and encyclopaedias, 54 and party-based newspapers, such as Pravda. 55 Primarily, the culture of Soviet censorship required that the reliability of such sources be questioned. 56 According to Shwartz, Soviet publishing involved an estimated 70,000 censors responsible for choosing what was suitable in terms of “state security” and the expectations of the leader. 57 Moreover, Bergson, although referring to Soviet economics, identified that the volume of statistical data available pre-collapse of the Soviet Union, was “systematically limited”, a consequence of its international standing as a “closed society”. 58 Thus, Linden suffered a, “poverty of historiography”, 59 limiting the extent and depth of his research.60 Consequently, Light maintained that a “social scientific analyst of the USSR”, such as Linden, “is forced to resort to speculation”, rather than engaging in the testing of coherent facts.61 Thus, contradicting Jenkins’ assertion that an ethically responsible historian does not “fill in the silence of history by empirical noise”.62 Hence, by inferring in the absence of evidence, it is inevitable that Linden’s conclusions were flawed,63 impeding the accuracy of his interpretation.64 Thus, Linden’s text, while comprehensive for its time, nevertheless presented a limited interpretation of the most prominent cause of Khrushchev’s expulsion.65

Medvedev 66 perceived Khrushchev’s reformist ideology, and subsequent alterations to the political structure of the Soviet Union, as the most prominent cause of his expulsion.67 While Medvedev, like Tompson, acknowledged Khrushchev’s

41 Linden’s Cold War context was characterised by attempts to formulate alternative visions of global history and politics, with intellectuals seeking to break away from the traditional framework of global affairs, that appeared to offer only two competing visions of world order (communism and capitalism). Sachsenmaier, D. (2006). Global History and Critiques of Western Perspectives. Comparative Education, 42(3), 451–470. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29727795 p.456

42 Ibid.

43 Linden obser ved the “conventional school” as those that emphasise the stability of a recognised leader within the Soviet Union. While accepting that conflict occurs between contenders for succession, it treats conflict, not as continuous, but rather believing there to be a phase of political stability once a political figure becomes the recognised leader of the regime. Linden, C. A. (1966). Op. cit. p. 2

44 See footnote 5.

45 Linden, C. A . (1966). Op. cit. p. 2

46 Taylor and Francis. (n.d.). Op. cit. p. 113

47 Joel likened the Cold War period to that of the Enlightenment period, with the emergence of significant social and political reform following the intensive indoctrination of the Western world in relation to Cold War events, such as the Vietnam War. Hence, he identified the period as “the Cold War enlightenment”. Joel, I. (2014). The Cold War Enlightenment https://www.crassh.cam.ac.uk/events/25494/

48 Ali, M. (2002). History, Ideology and Curriculum. Economic and Political Weekly, 37(44/45), 4530–4531. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4412809

49 Linden, C. A . (1966). Op. cit. p. vii

50 Linden wrote in 1966, during the Cold War period and amidst Brezhnev’s years in power. Thus, Gorbachev’s policies of Glasnost had yet to be implemented, and Soviet material remained inaccessible. Shvangiradze, T. (2022, February 20). The Gorbachev Era: Glasnost and Perestroika Pre-Fall of the Soviet Union. The Collector https://www.thecollector. com/gorbachev-era-glasnost-perestroika-fall-of-soviet-union/

51 Conolly, V. (1968). Op. cit. p. 262

52 Linden, C. A . (1966). Op. cit. p. 263

53 Linden utilised published Soviet texts available to the Western audience such as The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and Fundamentals of Marxist-Leninism by Kuusien Ibid.

54 Linden made significant use of political dictionaries and encyclopaedias such as Bol’shaya sovetskaya entsiklopediya (the large Soviet Encyclopaedia), Politicheskii Slovar (Political Dictionary), from which he obtained brief statements of political agendas on several policy decisions, and Spravochnik Partiynhogo Rabotnika (Handbook of the Party Worker).

Ibid.

55 Ibid.

56 Elwood, R. C. (1967). Op. cit. p. 716

57 Schwartz, B. A. (1959). Publishing in the USSR. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 73 cited in Booher, E. E. (1975). Publishing in the USSR and Yugoslavia. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 421(1), 118–129. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1040874 p. 124

58 Bergson, A. (1953). Reliability and Usability of Soviet Statistics: A Summary Appraisal. The American Statistician, 7(3), 13–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2685494 p. 14

59 St Mary’s University, Twickenham. (2013, December 5). Interview with Professor of Historical Theory Keith Jenkins (University of Chichester). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cu2znmjTgvM

60 Linden, C. A . (1966). Op. cit. p. 263

61 Light, M. (1981). Approaches to the Study of Soviet Foreign Policy. Review of International Studies, 7(3), 127–143. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20096914 p. 128

62 Jenkins, K. (2005). On History, Historians and Silence. History Compass, 2(1), 1. https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.14780542.2004.00112.x

63 According to Linden, Khrushchev’s failure to assert Soviet domination amidst the Cuban Missile Crisis resulted in a loss of support from the Central Committee, placing him in a vulnerable political position. Alternatively, Tompson’s later access to the Central Party Archives, and the revelation that decisions were made collectively in relation to the Cuban Missile Crisis, contradict Linden’s perception. Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 272

64 Elwood, R. C. (1967). Op. cit. p. 715

65 Rush, M. (1968). Op. cit. p. 493

66 See footnote 9.

67 Medvedev, R. (1978). Op. cit. p. 147

decreasing popularity within the public sphere, he regarded it as a temporary issue.68 Rather, Medvedev placed notable weight upon the introduction of democracy into Soviet politics, following Khrushchev’s policies regarding the political party.69 Primarily, the decision that one-third of CPSU members were to be replaced by 1965,70 laid the foundation for party members to fear replacement by “younger blood”, subsequently depriving them of the sense of security typically affiliated with a lifetime tenure.71 Such fears were exemplified by the 1962 division of oblast-level party committees into industrial and agricultural sectors,72 that fundamentally divided the party structure into two independent components.73 Thus, resulting in the rise of a system that exhibited similarities to “a two-party structure”.74 Consequently, Khrushchev’s expulsion was regarded as fundamental to restore the CPSU to its “accustomed state of unified territorial power”.75 Similarly to Linden,76 Medvedev acknowledged the prevalence of conflict over positions of authority, post-Stalin, however, he viewed such conflict as a consequence of the prevalence of democracy in “embryo form”, rather than being inherent to the natural state of the Soviet political system.77 Collectively, Medvedev viewed that one of Khrushchev’s significant shortcomings was his limited comprehension of party motives78 and, as McAuley stated, he “failed to realise that they [party members] would not follow him” and his reformist policies “blindly”.79 Thus, policies regarding the structure of the CPSU established the “determination of Khrushchev’s allies to switch loyalties and replace him”, resulting in his expulsion.80

Medvedev’s previous membership in the CPSU provided him with a comprehensive understanding of its political inner workings, by which his viewpoint on Khrushchev’s expulsion was framed.81 As a samizdat 82 historian, Medvedev held a post-structuralist viewpoint,83 attempting to look beyond the framework of traditional Marxist-based ideology84 in order to transmit the “truth suppressed by state-censored publications”.85 Accordingly, he was a member of the reformist Party Democratic Movement86 and held the personal ideology of a committed Marxist-Leninist.87 Thus, Medvedev aligned himself with many of Khrushchev’s reformist policies,88 maintaining a less critical analysis.89 Consequently, he viewed that the issue of such policies lay in their rapid implementation, rather than their foundational ideology.90 Further, having been removed from the CPSU, much like Khrushchev, as a consequence of the publication of his text Let History Judge,91 Medvedev held a unique personal comprehension of the incompatibility of Khrushchev’s reformist

81 Cohen, F. S. (1975, July 13). Op. cit.

82 Samizdat can be defined as self-published material, which was secretly written, copied and circulated, often by hand, in the former Soviet Union, rather than being approved and published by the Soviet government. Samizdat texts were most commonly critical of the Soviet Government and began appearing following Stalin’s death, in 1953, as a revolt against restrictions on freedom of expression for Soviet authors. Contributors were subjected to high surveillance and harassment by the KGB, reflected in the show trial of 1973. The most active period of samizdat publication took place between 1962 and 1966. Britannica. (n.d.). Samizdat. https://www.britannica.com/technology/samizdat

83 Komaromi, A. (2004). The Material Existence of Soviet Samizdat. Slavic Review, 63(3), 597–618. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1520346 p. 598

68 Medvedev identified that Khrushchev stabilised his popularity amongst the Soviet public by denouncing Stalin at the 22nd Congress meeting, in which he revealed details of gulag death warrant lists and the millions of victims. Consequently, portraits and monuments of Stalin were destroyed, Stalingrad renamed, and Khrushchev successfully diverted attention away from his own broken political promises. Ibid.

69 Ibid.

70 1965 was both the end of a leadership term, according to the Soviet Union’s constitution, and the year in which the next party congress meeting was to take place. Hence, the reversal of Khrushchev’s reforms could not be made until then. Ibid.

71 Ibid. p. 169

72 The 1962 division of oblast-level party committees into industrial and agricultural sectors was essentially a reorganisation of the party structure. While aiming to improve upon the agricultural sectors of Soviet society, the decision resulted in a lack of authority in both agricultural and industrial production. This was significant as party committees were viewed as the “nuclei” of local authority. For instance, agricultural councils no longer had the power to recruit urban factory workers, and industrial committees were free from such responsibility, causing disunity. Consequently, Oblast secretaries who had previously supported Khrushchev during the 1957 anti-party group coup, now opposed him. Tucker, R. C. (1957). The Politics of Soviet De-Stalinization. World Politics, 9(4), 550–578. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2009424 p. 553

73 Medvedev, R. (1978). Op. cit. p. 155

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid. p. 158

76 Linden, C. A . (1966). Op. cit. p. 1

77 Medvedev, R. (1978). Op. cit. p. 157

78 Ibid. p. ix

79 McAuley, M. (1992). Op. cit. p. 73

80 Medvedev, R. (1978). Op. cit. p. 151

84 This post-structuralist viewpoint is similarly evident in Medvedev’s aim. In writing his text, Medvedev aimed to educate his Western and Soviet audiences on the “atmosphere of the Khrushchev period as it was felt by those living within the Soviet Union”, thus providing a perspective of Khrushchev “from within the system”. As many of Medvedev’s historical works remain taboo in Russia, circulating only under samizdat, Medvedev aimed to expose this inner political experience to those who remained unaware.

Barghoorn, F. C. (1973). Medvedev’s Democratic Leninism [Review of Kniga O Sotsialisticheskoi Demokratii., by R. Medvedev]. Slavic Review, 32(3), 590–594. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2495414 p. 590

85 Komaromi, A. (2004). Op. cit. p. 614

86 In Medvedev’s text, On Socialist Democracy, he defines the Party Democratic Movement as those viewing that the USSR was not a society of developed socialism, although its official ideology suggested this. Members believed the Soviet system should involve rationalised communist economics and the political freedoms associated with Western liberalism such as freedoms of expression and civil rights.

Fireside, H. (1989). Dissident Visions of the USSR: Medvedev, Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn. Polity, 22(2), 213–229. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3234832 p. 216

87 See footnote 11.

88 Whilst a member of the CPSU, Medvedev advocated for the introduction of democracy into Soviet politics, such as the emergence of a two-party system and restrictions upon time in office, all of which had been introduced, or attempted to be introduced, during the Khrushchev-era. Further Medvedev similarly subscribed to Lenin’s belief that, “Socialism is impossible without the realisation of democracy”.

Barghoorn, F. C. (1973). Op. cit. p. 592

89 Cohen, F. S. (1975, July 13). Op. cit.

90 Medvedev, R. (1978). Op. cit. p. 143

91 Let History Judge, by Roy Medvedev, published in 1959, was an investigation into Stalinism in the Soviet Union from 1922-1953, including unpublished memoirs and archives from survivors of the gulags. Consequently, the text exposed the distortions of socialism in the Soviet Union under Stalin. Conquest, R. (1972, June). Let History Judge, by Roy A. Medvedev. Commentary https://www.commentary.org/articles/robert-conquest/let-history-judge-by-roya-medvedev/

Critically assess historians’ differing interpretations of the most prominent cause of the expulsion of Nikita Khrushchev from power | LAEL SAKALAUSKAS YEAR 12, 2023

philosophy with the basic principles of the traditionally one-party Communist state.92 Thus, it is inevitable that Medvedev projected his own political context onto his interpretation.93 Whilst Medvedev’s political context granted him “insider” observations,94 the tendency to apply his personal ideology and experiences to his interpretation of Khrushchev’s expulsion limits its impartiality.95

Living and writing in the Soviet Union, Medvedev was granted access to “internal information”,96 however, he remained subject to Soviet constraints on the transmission of knowledge.97 Khrushchev remains a topic seldom discussed in the Soviet Union, and current Russia, as hardly a word about Khrushchev “has been published in his own country”.98 Consequently, Medvedev relied not on published works, but texts that emerged from the most active period of samizdat 99 publication.100 Further, Medvedev referenced both personal observations, acquired during party membership, and oral testimony of individuals within the state apparatus, offering invaluable insight into the inner workings of Soviet politics.101 However, utilising sources obtained through unconventional means, Medvedev’s text lacked scholarly footnotes, limiting its reliability.102 Accordingly, Warth identified that it is unknown which material is “derived from high-level rumour and which has been obtained by reliable witness accounts”.103 Further, residing in a state with tight control on the consumption of information,104 Medvedev lacked a familiarity in foreign policy, prevalent in several Western texts.105/106 Consequently, Medvedev directed his focus primarily

92 Parks, M. (1989, April 29). Medvedev Dumped in ’69 : Soviet Party Reinstates Anti-Stalinist Historian. Los Angeles Times https://www.latimes.com/ archives/la-xpm-1989-04-29-mn-1673-story.html

93 Medvedev, R. (1978). Op. cit. p. 143

94 Warth, R. D. (1985). [Review of Khrushchev; All Stalin’s Men, by R. Medvedev, B. Pearce, R. Medvedev, H. Shukman, and B. Pearce]. The American Historical Review, 90(1), 187–188. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1860864 p. 188

95 Cohen, F. S. (1975, July 13). Op. cit.

96 Pethybridge, R. (1977). [Review of Khrushchev. The Years in Power, by R. Medvedev and Z. Medvedev]. Soviet Studies, 29(4), 616–617. http://www.jstor. org/stable/150544 p. 617

97 Gustafson, B. (1978). [Review of Khrushchev: The Years in Power, by R. Medvedev and Z. Medvedev]. New Zealand International Review, 3(3), 33. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/45232888 p. 33

98 Medvedev, R. (1978). Op. cit. p. vii

99 See footnote 82.

100 Pethybridge, R. (1977). Op. cit. p. 617

101 Ibid.

102 Warth, R. D. (1985). Op. cit. p. 187

103 Ibid.

104 During the writing of both Let History Judge and Khrushchev: The Years in Power, Medvedev claimed an incident in which the KGB searched his residence, confiscating all material on Stalin and Khrushchev, thus demonstrating restrictions on the circulation of information within Soviet borders.

Marwick, R. D. (2004). Medvedev, Roy Alexandrovich. Encyclopedia of Russian History, 3(1), 909-910.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3404100810/ WHIC?u=61merid&sid=bookmark-WHIC&xid=c68d42b7 p. 910

105 Historians such as Swain and Tompson provided more in-depth recognition of international affairs, such as the Cuban Missile Crisis and relations with China, either in setting the atmosphere of the Khrushchev period or demonstrating the consequences they had for his leadership.

Swain, G. (2015). Khrushchev. Red Globe Press.

106 Warth, R. D. (1985). Op. cit. p. 188

towards domestic and agricultural affairs,107 neglecting to adequately consider the “whole spectrum of policy” and providing a highly selective perspective.108 Additionally, as a samizdat publication, that has not obtained state verification, Medvedev’s argument carried no guarantee of authenticity prior to Western publication, limiting its credibility.109 Regardless, while the reliability of Medvedev’s text must be questioned, his access to Soviet historiography, unprecedented by Western historians, strengthened his comprehensive interpretation of Khrushchev’s expulsion.110

Tompson111 regarded Khrushchev’s broken political promises, and subsequent loss of popularity, as the most prominent cause of his expulsion.112 Much like Linden, Tompson maintained that there was a period of political uncertainty post-Stalin, from which Khrushchev presented himself as an individual who would ensure the “survival of the socialist regime”.113 Yet, Tompson examined that it was this promise of utopia that generated unrealistic expectations which, when unmet,114 both alienated Khrushchev from popular support and provoked fears of mass disorder amongst the Soviet population.115 Tompson perceived that the Soviet public held sufficient power to act on their grievances and intimidate the elite, as evident in the events of Novocherkassk.116/117 This perception is reinforced by Weeks who wrote in reference to the threat of war, asserting that “many autocratic leaders face a realistic possibility of punishment by

107 Medvedev placed significant emphasis on agricultural affairs such as the Riazan affair. While the city of Riazan had been the centre of a national campaign to drive up meat production, having announced a tripled annual yield of meat in 1959, investigations in 1960 revealed falsities in the state’s statistical reporting. The true meat production was barely a third of the figure presented, significantly impacting the reputation of the Soviet government holistically.

Gorlizki, Y. (2013). Scandal in Riazan: networks of trust and the social dynamics of deception.

Kritika, 14(2), 245. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A332655149/AONE?u=googles cholar&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=b4b231d5 p. 245

108 Gustafson, B. (1978). Op. cit. p. 33

109 Conquest, R. (1972, June). Op. cit.

110 Warth, R. D. (1985). Op. cit. p. 187

111 See footnote 16.

112 Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 274

113 Tompson, W. J. (1993). Khrushchev and Gorbachev as Reformers: A Comparison. British Journal of Political Science, 23(1), 77–105. http://www.jstor. org/stable/194068 p. 90

114 Khrushchev’s political promises went unmet under several circumstances, the most prevalent being the 1963 harvest failure of the “virgin lands”. The virgin lands were lands for agricultural production that Khrushchev placed particular emphasis on, sowing 10 million hectares more than in 1955. However, the harvest of 1963 produced the smallest crop output in eight years, thus not reaching goals set forth in Khrushchev’s seven-year plan and causing mass food shortages.

Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 264

115 Ibid. p. 274

116 Novocherkassk took place in June 1962, a riot against low living standards and poor working conditions within the Soviet public. 26 individuals were killed and 86 wounded as a result.

The Cold War. (2021, July 31). Novocherkassk Massacre 1962 - Soviet Army vs People. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b06Gfm2QVxY

117 Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 274

a civilian domestic audience”.118 Hence, Tompson perceived Khrushchev’s broken political promises as the most prominent catalyst for provoking fear within Soviet leadership, ultimately leading to his expulsion.119

Tompson’s political ideology had a significant impact on his comprehension of Khrushchev’s expulsion. Sachsenmaier, reflecting Rankean ideology, states that “any kind of research with a global perspective is required to find a way to balance the universal with the particular”.120 In this sense, Tompson successfully endeavoured to be aware of both the Soviet Union’s internal structure and its international standing, maintaining a balanced viewpoint.121 Regardless, Tompson, as a political scientist, is inclined to adopt a nomothetic stance, applying “regularities and broad patterns” in order to make “lawlike generalisations”,122 according to Schroeder.123 Accordingly, Tompson’s comprehension, of Marxist-Leninist systems is one consistent with the views of De Mesquita and Smith, who asserted that “no leader is monolithic”, but requires the support of others.124 As such, it is the “reliable implementation of political promises to those who count” that ensures a leader’s position,125 a direct reflection of Tompson’s argument that the failure to implement political promises was foundational to Khrushchev’s expulsion.126 However, according to Schroeder, this understanding neglects to consider existing diversity amongst Marxist-Leninist regimes.127 Thereby, Tompson’s political agenda regarding the operation of Marxist-Leninist systems, is foundational to his understanding of Khrushchev’s expulsion.128

As a consequence of his temporal context, Tompson’s interpretation is one shaped by the prevalence of Soviet sources in Western scholarship, enhancing understanding of Khrushchev’s expulsion.129 Unlike Linden,130 Tompson gained significant access to historiographical material as a consequence of Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and following

118 Weeks, J. L. P. (2014). Dictators at War and Peace. [e-book]. Google Books. https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/Dictators_at_War_and_Peace/ ijVtBAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=jessica+L.P.+Weeks&printsec=frontcover p. 4

119 Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 274

120 Sachsenmaier, D. (2006). Op. cit. p. 455

121 Ibid.

122 According to Schroeder, the aims of a political scientist differ significantly from those of a traditional historian. The political scientce approach often involves the development of a hypothesis, which is then examined with regard to a theory. Accordingly, they often assign causes for events and developments, and establish general patterns that are applied to variety of circumstances. Schroeder, P. W. (1997). History and International Relations Theory: Not Use or Abuse, but Fit or Misfit. International Security, 22(1), 64–74. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/2539329?seq=2 p. 68

123 Ibid.

124 Smith, A. and Mesquita, B. (2012). The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics. PublicAffairs p. 14

125 Linden, C. A . (1966). Op. cit. p. 263

126 Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 274

127 Schroeder, P. W. (1997). Op. cit. p. 65

128 Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 274

129 Torigian, J. (2022). Op. cit. p. 80

130 Elwood, R. C. (1967). Op. cit. p. 716

the 1992 Pioneer Agreement.131 Further, successive to the fall of the Soviet Union, Tompson was provided with the opportunity to reside in Russia (1992 to 1993).132 Thus, he obtained access to pivotal material in the previously inaccessible Central Party Archives and Archive of the Soviet Army, expanding the scope of his research.133 Further, in conducting interviews with Khrushchev’s surviving associates, not dissimilar to Medvedev, Tompson gained primary accounts of Khrushchev’s expulsion, collecting evidence that a failure of policy decisions led to his deterioration of character and subsequent unstable leadership.134 Richter observed that the majority of Tompson’s archival research was committed to Khrushchev’s early career, rather than his expulsion from power,135 as a consequence of his generalised aim “to account for new information and evidence”.136 According to Yekelchyk, this may be a consequence of the reality that the majority of Soviet documentation regarding Khrushchev’s years in power remained in the inaccessible Presidential Archives, highlighting the persistent constraints of Tompson’s Western context.137 Additionally, while the Gorbachev period saw greater access to Soviet documentation, it is crucial to recognise that such records continued to reflect the expectation of the leader,138 and therefore their reliability remains questionable, as

131 The Pioneer Agreement on exchanging archival information, was signed between the Federal Archival Service of Russia, the Hoover Institute on War, Revolution and Peace at Stanford University, and Cambridge University. The Agreement saw the exchange of archival information on Russia and its people in the 20th century. An equal number of documents were compiled: Russian and American historical works with an emphasis on power, religion, public expectations and state response, and the international activity of the USSR. Shvangiradze, T. (2022, February 20). Op. cit.

132 Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 273

133 Fitzpatrick stated that the introduction of Soviet sources shifted the situation from “one comparable to that of… early modern history to that of [a] developed 20th century state”. Consequently, although Tompson addressed several contentions in his text, particularly between Beijing and the United States, access to documentation led him to conclude that foreign affairs did not act as a point of dispute between the party and Khrushchev, in his removal during the Presidium meeting of 1964.

Fitzpatrick, S. (2015). Impact of the Opening of Soviet Archives on Western Scholarship on Soviet Social History. The Russian Review, 74(3), 377–400. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/43662294 p. 386

134 Some specific examples of interviews Tompson conducted include P. E. Shelest, a surviving associate of Khrushchev, as well Sergei Khrushchev, Nikita Khrushchev’s son.

Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 270

135 Richter, J. (1995). [Review of Khrushchev: A Political Life, by W. J. Tompson]. Slavic Review, 54(4), 1103–1104. https://www.cambridge.org/core/ journals/slavic-review/article/abs/khrushchev-a-political-life-by-william-j-tompsonnew-york-st-martins-press-1994-ix-341-pp-index-2495-hard-bound/203636DE7B7 B81563992B10E2A89A094 p. 1104

136 Tompson, W. J. (1995). Khrushchev: A Political Life. History: Reviews of New Books, 24(2), 90. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03612759.1996 .9951238 p. 90

137 Yekelchyk, S. (1998). [Review of Khrushchev: A Political Life, by W. J. Tompson]. The Slavic and East European Journal, 42(3), 565–566. https://www.jstor. org/stable/309710 p. 566

138 Taubman, W. (2004). Op. cit. p. xiv

Critically assess historians’ differing interpretations of the most prominent cause of the expulsion of Nikita Khrushchev from power | LAEL SAKALAUSKAS YEAR 12, 2023

previously discussed.139 Thus, although Tompson’s access to Soviet historiography expanded his comprehension of Khrushchev’s expulsion, the reliability of his evidence remains ambiguous.140

Despite Khrushchev’s expulsion from power occurring less than a century ago, understanding surrounding the most prominent cause of the event has evolved significantly. This evolution can be attributed to the increased access to Soviet historiography, allowing for the assembling of a more complete picture of the atmosphere and circumstances influencing Khrushchev’s expulsion. Linden’s interpretation, whilst supported by compelling contextual information and neo-enlightenment understanding, suffered from a deficiency of substantial evidence.141 Alternatively, Medvedev’s theory, although lacking variation in regard to international policy, is strengthened by critical analysis of internal Soviet politics and invaluable access to Soviet historiography.142 Tompson, although the most credible in terms of sufficiently balanced historiography, is not without influence from his political context, maintaining a nomothetic stance.143 Thus, much like Linden, Tompson presented a highly Western-centric perspective by drawing parallels between Soviet and Western politics.144 Thus, due to a range of historiographical factors, the opportunity to uncover the most prominent cause of Khrushchev’s expulsion becomes increasingly complex. As such, “there are no definitive histories since no historian’s ruling perceptual network can ever account for the entire historical field”,145 and it remains inevitable that amidst the ever-changing nature of political relations between Russia and the Western world, perspectives of Khruschev’s expulsion from power will continue to evolve.

Lane, D. (1981). Leninism: A sociological interpretation. Cambridge University Press.

Linden, C. A. (1966). Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership, 19571964. The Johns Hopkin University Press.

Linden, C. A. (1983). The Soviet party-state: the politics of ideocratic despotism. Praeger.

Linden, C. A. (1990). Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership: With an Epilogue on Gorbachev. The John Hopkin University Press

McAuley, M. (1992). Soviet Politics 1917-1991. Oxford University Press.

Medvedev, R. (1978). Khrushchev: The Years in Power. W. W. Norton and Company.

Medvedev, R. (1981). Leninism and Western Socialism. Verso Books. Rigby, T.H. (1968). Stalin Dictatorship: Khrushchev’s ‘Secret Speech’ and Other Documents. Sydney University Press.

Seton-Watson, H. (1960). From Lenin to Khrushchev: The History of World Communism. Routledge.

Smith, A. and Mesquita, B. (2012). The Dictator’s Handbook: Why Bad Behavior is Almost Always Good Politics. PublicAffairs. Swain, G. (2015). Khrushchev. Red Globe Press.

Tompson, W. J. (1994). Khrushchev: A Political Life. Palgrave Macmillan London.

Taubman, W. (2004). Khrushchev: The Man and His Era. W. W. Norton and Company.

Book as E-book

Possing, B. (2017). Understanding Biographies: On Biographies in History and Stories in Biography. [e-book]. University Press of Southern Denmark. https://www.universitypress.dk/images/pdf/2992. pdf

Svolik, M. W. (2012). The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. [e-book]. Google Books. https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/ The_Politics_of_ AuthoritmcZ6pmTnIwQC?hl=en&gbpv= 1&dq=milan+svolik&printsec=frontcover

Tompson, W. (2003). The Soviet Union Under Brezhnev. [e-book]. Google Books. https://www.google.com.au/ books/edition/ The_Soviet_Union_under_Brezhnev/ F8UeBAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=william +J.+Tompson&printsec=frontcover

139 In his text, Tompson explicitly admitted occasions of heavy censorship, primarily amongst the communist press of Pravda and Izvestiia. For example, a 1964 live broadcast to the Soviet Union saw Khrushchev referring to Stalin as among the “tyrants in the history of mankind”, yet the version that appeared in Pravda the following day omitted such a statement.

Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 225

140 McCauley, M. (1995). [Review of Khrushchev: A Political Life, by W. J. Tompson]. Europe-Asia Studies, 47(7), 1247. http://www.jstor.org/stable/152598 p. 1247

141 Linden, C. A . (1966). Op. cit. p. 206

142 Medvedev, R. (1978). Op. cit. p. 152

143 Schroeder, P. W. (1997). Op. cit. p. 65

144 Tompson, W. J. (1994). Op. cit. p. 266

145 Octalog, G. (1988). The Politics of Historiography. Rhetoric Review, 7(1), 5–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/465534 p. 6

Weeks, J. L. P. (2014). Dictators at War and Peace. [e-book]. Google Books. https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/Dictators_ at_War_and_Peace/ijVtBAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=jessica+ L.P.+Weeks&printsec=frontcover

Medvedev, R. (1976). Khrushchev: The Years in Power. [e-book]. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/ khrushchevyearsi00medv_0/mode/1up

Medvedev, Z. A. and Medvedev, R. A. (1971). A question of madness. [e-book]. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/ questionsofmadne0000unse/page/14/mode/1up

Corporate publication

Taylor and Francis. (n.d.). Variety and Adventure in the life of Carl Linden. https://albert-schmidt.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/33Carl-Linden-Tribute_PPS_2014.pdf

The RAND Corporation. (1990). Glasnost and Soviet Foreign Policy. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/notes/2009/N3008.pdf

Encyclopaedia

Britannica. (n.d.). The Gorbachev era: perestroika and glasnost. In Britannica.com. Retrieved April 3, 2023 from https://www.britannica. com/place/Russia/The-Gorbachev-era-perestroika-and-glasnost Britannica. (n.d.) Pravda. In Britannica.com. Retrieved April 3, 2023 from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Pravda Britannica. (n.d.). Roy Medvedev. In Britannica.com. Retrieved March 2, 2023 from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Roy-Medvedev Britannica. (n.d.). Samizdat. In Britannica.com. Retrieved April 16, 2023 from https://www.britannica.com/technology/samizdat

Encyclopedia Astronautica. (1997). Kamanin Diaries. In Astronautix. com. Retrieved April 15, 2023 from http://www.astronautix.com/k/ kamanindiaries.html

New World Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Marxism-Leninism. In Britannica.com. Retrieved April 16, 2023 from https://www.newworldencyclopedia. org/entry/Marxism-Leninism

Journal Articles

Ali, M. (2002). History, Ideology and Curriculum. Economic and Political Weekly, 37(44/45), 4530–4531. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/4412809

Armstrong, J. A. (1996). [Review of Khrushchev: A Political Life, by W. J. Tompson]. The American Historical Review, 101(4), 1250–1251. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2169756

Barghoorn, F. C. (1973). Medvedev’s Democratic Leninism [Review of Kniga O Sotsialisticheskoi Demokratii., by R. Medvedev]. Slavic Review, 32(3), 590–594. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2495414

Bergson, A. (1953). Reliability and Usability of Soviet Statistics: A Summary Appraisal. The American Statistician, 7(3), 13–16. https:// www.jstor.org/stable/2685494

Boiter, A. (1972). Samizdat: Primary Source Material in the Study of Current Soviet Affairs. The Russian Review, 31(3), 282–285. https:// www.jstor.org/stable/128049

Booher, E. E. (1975). Publishing in the USSR and Yugoslavia. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 421(1), 118–129. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1040874

Butler, W. E. (1967). [Review of Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 1957-1964; Soviet Policy-Making: Studies of Communism in Transition; Soviet Economic Controversies: The Emerging Marketing Concept and Changes in Planning, 1960-1965; Central Asians Under Russian Rule: A Study in Culture Change, by C. A. Linden, P. H. Juviler, H. W. Morton, J. L. Felker, and E. E. Bacon]. World Affairs, 129(4), 275–278. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20670857

Conolly, V. (1968). [Review of Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 1957-1964, by C. A. Linden]. The Slavonic and East European Review, 46(106), 261-262. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4205967

De Mesquita, B. and Smith, A. (2017). Political Succession: A Model of Coups, Revolution, Purges, and Everyday Politics. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(4), 707–743. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/26363872

Elwood, R. C. (1967). [Review of Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 1957-1965, by C. A. Linden]. International Journal, 22(4), 715–716. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40200249

Fireside, H. (1989). Dissident Visions of the USSR: Medvedev, Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn. Polity, 22(2), 213–229. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/3234832

Fitzpatrick, S. (2015). Impact of the Opening of Soviet Archives on Western Scholarship on Soviet Social History. The Russian Review, 74(3), 377–400. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43662294

Gorlizki, Y. (2013). Scandal in Riazan: networks of trust and the social dynamics of deception. Kritika, 14(2), 245. https://link.gale.com/ apps/doc/A332655149/AONE?u=googlescholar&sid=bookmarkAONE&xid=b4b231d5

Gustafson, B. (1978). [Review of Khrushchev: The Years in Power, by R. Medvedev and Z. Medvedev]. New Zealand International Review, 3(3), 33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45232888

Hanak, H. (1967). [Review of Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership, 1957-1964., by C. A. Linden]. International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), 43(4), 759–760. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/2612849

Hanson, G. (1997). [Review of Khrushchev: A Political Life, by W. J. Tompson]. The Historian, 59(3), 711–712. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/24452072

Holm, K. C. (1967). [Review of Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 1957-1964, by C. A. Linden]. Naval War College Review, 19(9), 128–129. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44640988

Jenkins, K. (2005). On History, Historians and Silence. History Compass, 2(1), 1. https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ abs/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2004.00112.x

Komaromi, A. (2004). The Material Existence of Soviet Samizdat. Slavic Review, 63(3), 597–618. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1520346

Kneen, P. (1984). [Review of Khrushchev, by R. Medvedev and B. Pearce]. Soviet Studies, 36(1), 152–153. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/151871

Linden, C. A. (1979). [Review of Khrushchev: The Years in Power, by R. A. Medvedev and Z. A. Medvedev]. The American Political Science Review, 73(2), 644–645. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1954985

Light, M. (1981). Approaches to the Study of Soviet Foreign Policy. Review of International Studies, 7(3), 127–143. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/20096914

Marwick, R. D. (2004). Medvedev, Roy Alexandrovich. Encyclopedia of Russian History, 3(1), 909-910. https://link.gale. com/apps/doc/CX3404100810/WHIC?u=61merid&sid=bookmarkWHIC&xid=c68d42b7

McCauley, M. (1995). [Review of Khrushchev: A Political Life, by W. J. Tompson]. Europe-Asia Studies, 47(7), 1247–1247. http://www.jstor. org/stable/152598

Nasaw, D. (2009). Historians and Biography. The American Historical Review, 114(3), 573–578. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30223918

Nemzer, L. (1966). [Review of Russia after Khrushchev, by R. Conquest]. The Russian Review, 25(2), 184–187. https://doi. org/10.2307/127331

Octalog, G. (1988). The Politics of Historiography. Rhetoric Review, 7(1), 5–49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/465534

Pethybridge, R. (1977). [Review of Khrushchev. The Years in Power, by R. Medvedev and Z. Medvedev]. Soviet Studies, 29(4), 616–617. http://www.jstor.org/stable/150544

Richter, J. (1995). [Review of Khrushchev: A Political Life, by W. J.

Critically assess historians’ differing interpretations of the most prominent cause of the expulsion of Nikita Khrushchev from power | LAEL SAKALAUSKAS YEAR 12, 2023

Tompson]. Slavic Review, 54(4), 1103–1104. https://www.cambridge. org/core/journals/slavic-review/article/abs/khrushchev-a-politicallife-by-william-j-tompson-new-york-st-martins-press-1994-ix-341-ppindex-2495-hard-bound/203636DE7B7B81563992B10E2A89A094

Richards, J. R. (2007). The role of Biography in Intellectual History. KNOWN: A Journal on the Formation of Knowledge, 1(2), 1. https:// www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/693727

Rush, M. (1968). [Review of Khrushchev; A History of Postwar Russia; Beginnings of the Cold War; Khrushchev and the Soviet Leadership 1957-1964, by M. Frankland, H. Schwartz, R. W. Pethybridge, M. F. Herz, and C. A. Linden]. Slavic Review, 27(3), 492–494. https://www. jstor.org/stable/2493357

Sachsenmaier, D. (2006). Global History and Critiques of Western Perspectives. Comparative Education, 42(3), 451–470. http://www. jstor.org/stable/29727795

Schroeder, P. W. (1997). History and International Relations Theory: Not Use or Abuse, but Fit or Misfit. International Security, 22(1), 64–74. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539329?seq=2

Tompson, W. J. (1991). The Fall of Nikita Khrushchev. Soviet Studies, 43(6), 1101–1121. http://www.jstor.org/stable/152407

Tompson, W. J. (1993). Khrushchev and Gorbachev as Reformers: A Comparison. British Journal of Political Science, 23(1), 77–105. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/194068

Tompson, W. J. (1995). Khrushchev: A Political Life. History: Reviews of New Books, 24(2), 90. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/ 03612759.1996.9951238

Tompson, W. J. (2002). [Review of The Russian Presidency: Society and Politics in the Second Russian Republic, by T. M. Nichols]. Slavic Review, 61(1), 177–178. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2697027

Tompson, W. (2004). [Review of Khrushchev: The Man and His Era, by W. Taubman]. Journal of Cold War Studies, 6(4), 172–174. https://www. jstor.org/stable/26925440

Tompson, W. J. (2006). Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev: Commissar (1918-1945). Political Science Quarterly, 121(1), 178. https://link-galecom.ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/apps/doc/A144868726/AONE?u=slnsw_ public&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=06a49c29

Torigian, J. (2022). “You Don’t Know Khrushchev Well”: The Ouster of the Soviet Leader as a Challenge to Recent Scholarship on Authoritarian Politics. Journal of Cold War Studies, 41(1), 78-115. https://direct.mit.edu/jcws/article/24/1/78/109004/You-Don-t-KnowKhrushchev-Well-The-Ouster-of-the

Tucker, R. C. (1957). The Politics of Soviet De-Stalinization. World Politics, 9(4), 550–578. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2009424

Warth, R. D. (1985). [Review of Khrushchev; All Stalin’s Men, by R. Medvedev, B. Pearce, R. Medvedev, H. Shukman, and B. Pearce]. The American Historical Review, 90(1), 187–188. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/1860864

Weir, F. (1993). An interview with Roy Medvedev. Monthly Review, 44(9), 1. https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/ apps/doc/A13469431/AONE?u=slnsw_public&sid=bookmarkAONE&xid=4d8aa6b2

Yekelchyk, S. (1998). [Review of Khrushchev: A Political Life, by W. J. Tompson]. The Slavic and East European Journal, 42(3), 565–566. https://www.jstor.org/stable/309710

Newspaper Article

Cohen, F. S. (1975, July 13). On Socialist Democracy. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1975/07/13/archives/on-socialistdemocracy.html

Conquest, R. (1972, June). Let History Judge, by Roy A. Medvedev. Commentary. https://www.commentary.org/articles/robert-conquest/ let-history-judge-by-roy-a-medvedev/

Conquest, R. (2003). The first Comprehensive biography of Stalin’s successor. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/ magazine/2003/03/31/loudmouth

Parks, M. (1989, April 29). Medvedev Dumped in ’69 : Soviet Party Reinstates Anti-Stalinist Historian. Los Angeles Times. https://www. latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-04-29-mn-1673-story.html

Shvangiradze, T. (2022, February 20). The Gorbachev Era: Glasnost and Perestroika Pre-Fall of the Soviet Union. The Collector. https:// www.thecollector.com/gorbachev-era-glasnost-perestroika-fall-ofsoviet-union/

Videos

C-Span. (1990, January 3). Second Meeting of the Soviet Congress. [Video]. C-Span. https://www.c-span.org/video/?10468-1/meetingsoviet-congress

St Mary’s University, Twickenham. (2013, December 5). Interview with Professor of Historical Theory Keith Jenkins (University of Chichester). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cu2znmjTgvM

The Cold War. (2020, September 26). Structure of USSR – Cold War Documentary. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=qNnyfziopko

The Cold War. (2021, July 31). Novocherkassk Massacre 1962 – Soviet Army vs People. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=b06Gfm2QVxY

Websites

Harvard Library. (2023). Soviet history: archival resources at Harvard university library and archives. https://guides.library.harvard.edu/ soviethistoryarchives/communistpartysovietstate History. (2009). Détente. https://www.history.com/topics/cold-war/ detente

Joel, I. (2014). The Cold War Enlightenment. https://www.crassh.cam. ac.uk/events/25494/ Siegelbaum, L. (n.d.). The Anti-Party Group. https://soviethistory.msu. edu/1956-2/the-anti-party-group/ Tompson, W. (n.d.). Curriculum Vitae. https://oecd.academia.edu/ WilliamTompson/CurriculumVitae

LEAH HAR

YEAR 10, 2023

This essay won first prize in the Philosophy in Schools Association of NSW 2023 Essay Competition. The stimulus asked students to critically evaluate two contrasting views and defend their own views of the topic: Should there be restrictions on free speech?

1. Introduction

Free speech is the expression of information, ideas and opinions without government restrictions1 and is fundamentally protected under the right to freedom of expression in the UNDR’s Article 19.2

Free speech in its absolute form, completely unrestricted, would mean that the state cannot impose any laws restricting freedom of expression or its associated laws. To argue for unrestricted free speech, one must prove why speech is valuable. The main values noted are democracy, autonomy, and utility; however, each of these allow for some limitations. For example, if speech is valued because it promotes democracy, then there are no grounds for protecting speech that damages democratic processes, as some forms of speech tend to suppress other forms of speech. If speech is not seen as useful, then under the utility argument, we have no reason to defend it.

Not only does the defence of speech have limiting factors but, in many cases, restrictions are necessary as the harms of some forms of speech outweigh the benefits of absolute free speech.

2. Values of speech

2a) Democracy

Alexander Meiklejohn, member of the American Civil Liberties Union, viewed free speech as inextricably linked to democracy. He believed that the First Amendment to the US Constitution, which includes the statement that Congress cannot make any law curtailing freedom of speech,3 served to keep the electorate informed, thereby creating self governance.4 Essentially, free

1 T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2023). freedom of speech Encyclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/freedom-of-speech

2 United Nations. (2021). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/03/udhr.pdf

3 Constitution Annotated. (n.d.). Constitution of the United States. https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-1/

4 Pur vis, D. (2009). Alexander Meiklejohn

https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1302/alexander meiklejohn

speech must be protected not just as the right of the person who speaks to be heard, but the right of those to hear what they are saying. Thus all speech, including speech criticising the government, is important to the functioning of democracy. However, a level of restriction on speech is beneficial to a healthy democracy. Some forms of speech, such as hate speech, suppress others, which hinders discussion based on mutual respect and is detrimental to democracy. Additionally, an increasing problem in the modern age is the spread of misinformation and fake news on social media. False information can influence opinions and alter the organic processes of public opinion formation, eroding the epistemic quality of deliberation in the people and, ultimately, shaping their behaviours in voting5 or taking stances on public issues.6 This affects democratic decision-making, making the government representative of a people who are influenced by fear and the often inflammatory and polarising content present in fake news. Misinformation is harmful even when it is not being consumed, as the knowledge itself that it exists and pervades our culture can lead to confusion over what the truth is and discourage civic engagement. If speech had no restrictions, misinformation would be even more pervasive, exacerbating this harm. Therefore, if we value democracy, then we should also value a level of restriction on speech.

2b)

Where Meiklejohn viewed the First Amendment as a keystone to democratic self government, C. Edwin Baker interprets it in Human Liberty and Freedom of Speech (1989) as concerned primarily with individual human liberty and autonomy;7 basically, the main reason for having free speech is because it allows us to be free. This echoes the sentiment of John Locke in 17th century England, who believed speech was a right guaranteed to citizens by virtue of their status as autonomous, individual beings living in a free society. Locke writes in Two Treatises on Civil Government (1689) that all individuals are equal in being born invested with certain “inalienable” natural rights, amongst which are life, liberty, and property.8

5 Buckmaster, L. and Wils, T. (2019). Responding to fake news. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/ Parliamentary_Library/pubs/Briefing Book46p/FakeNews

6 Benson, J. (2021). Is fake news a threat to deliberative democracy, and how bad is it? https://ecpr.eu/Events/Event/PaperDetails/59890

7 Baker, C. E. (1989). Human Liberty and Freedom of Speech. Oxford University Press.

8 Locke, J. and Filmer, R. (1884). Two Treatises on Civil Government. George Routledge and Sons. (Originally published 1689) https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/Two_Treatises_on_Civil_Government/ zEIqAAAAYAAJ

However, in everyday life, some individual rights are sacrificed for the sake of wider society, tying into the utilitarian view supporting the greatest good for the greatest number. Thomas Hobbes saw the unrestricted public expression of controversial beliefs and opinions as a source of civil strife.9 From Protagoras and Epicurus,10 Hobbes revived the idea of social contract theory, which states that people agree to rules and laws governing how to live in order to have security in society. An example of the social contract in practice would be that I forfeit my freedom to murder, so that others have the arguably more important freedom to live peacefully. Applying this to speech, the freedom to profess speech that incites violence is less valuable than the freedom of others to live safely.

A criticism of social contract theory is that it gives the government too much power.11 The power imbalance held by law enforcement is deemed part of the social contract agreed upon in exchange for security, but problems arise when this is abused to enforce intrusive laws under the guise of protecting the public. Under Hobbes’ social contract, the will of Leviathan, the political state, is law and is uncontested. However, Locke interprets the contract as dependent upon the condition that each person’s natural rights are protected. Rulers who violated these terms could be justifiably overthrown.12 Therefore, the people and the government are responsible for keeping each other in check.

John Stuart Mill writes in On Liberty (1859) that any doctrine should be allowed to be professed and discussed, regardless of how immoral it may seem to everyone else.13 His free speech advocacy was founded in a belief that a liberal, potentially laissez-faire society would lead to the most social utility.

Mill is often associated with the concept of the “marketplace of ideas”, although the exact phrase is attributed to Justice William O. Douglas in United States v. Rumely 14 The great benefit of the marketplace accrues from competition; the truth, or the best idea, will emerge from free public discourse, as long as their proponents are given a fair chance to argue for it and it garners popularity. Thus, the marketplace delivers the best ideas most efficiently and promotes utility. “Bad” ideas are ejected from the

9 Hobbes, T. (1651). Leviathan, Or, The Matter, Form and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiastical and Civil. Andrew Crooke. https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/Leviathan_Or_The_Matter_Form_ and_Power_o/L3FgBpvIWRkC

10 D’Agostino, F., Gaus, G. and Thrasher, J. (2021). Contemporary Approaches to the Social Contract, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/contractarianismcontemporary/

11 McCar tney, M. and Parent, R. (2015). Ethics in Law Enforcement. [e-book]. BCcampus. http://opentextbc.ca/ethicsinlawenforcement/

12 T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2023). social contract Encyclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/social-contract

13 Mill, J. S. (1895). On Liberty. Henry Holt and Company. (Originally published 1859) https://www.google.com.au/books/edition/On_Liberty/EPMQAAAAYAAJ

14 Gordon, J. (1997). John Stuart Mill and the “Marketplace of Ideas.” Social Theory and Practice, 23(2), 235– 249. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23559183

market due to a lack of demand, meaning dangerous or erroneous ideas are refuted, rather than suppressed. This places the power with the people to evaluate and critique ideas, instead of the government to decide what is right or wrong, moral or immoral. This is especially important in the skeptical view that there is no certainty in knowledge, and therefore nobody can claim the singular right or any superior authority in determining what is the truth.

However, it is arguable that this concept is unattainable in the modern day, especially with the rise of social media.15 Social media is a near-manifestation of a “marketplace of ideas”, but it is evident that the most popular ideas, indicated by likes or shares, are not necessarily the highest quality or most truth-based. Mill’s defence of free speech is contingent on the assumption that people have adequate judgement in which ideas to uplift and promote, but such faith in humanity may not have a solid basis.

Additionally, James Fitzjames Stephen, critic of John Stuart Mill, writes in Liberty, Equality, Fraternity (1874) that only the constraints of morality and law make liberty possible.16 Mill assumes that removal of restraint invigorates character, as full liberty of expression is required to push arguments to their logical limits. Stephen argues for the opposite: vigour comes from vicissitude and the overcoming of obstacles created by restraint. With restrictions in place, people may actually ideate more creatively and resourcefully, which promotes greater utility.