Exercise is even more effective than counselling or medication for depression.

But how much do you need?

Exercise is even more effective than counselling or medication for depression.

But how much do you need?

As publishers and owners of the Mental Health Awareness Magazine we are declaring that the information contained in this publication is for general information purposes only. While we endeavour to provide correct information, we make no representations or warranties and give no advice of any kind, express or implied, about the completenesss, accuracy, reliablity, suitability, effectiveness, correctness or availibilty of any information, text, data, chart, image, contact details, articles, announcements, advertisements, products, claims, services, qualifications or related graphics contained in the publication for any purposes. Any action by you, or failure to act by you or reliance you place on any information in the publication or any of the content of the publication is therfore strictly at your own risk and we take no responsibility and accept no liability for any consequences direct or indirect. The inclusion in this publication of any advertisement, article, advertorial, announcement, information, contact details, listing, image, design, chart, data, mark or representation does not constitute and does not imply advice, recommendation or endorsement by us of the associated practitioners, service providers, product providers, services, products, claims, opinions or views.

02 06 08 12 14 18 20 24

Concerned about student mental health? How wellness is related to academic achievement

New findings show a direct casual relationship between unemployment and suicide

Exercise is even more effective than counselling or medication for depression. But how much do you need?

Need a mental health day but worried about admitting it? You’re not alone

With rising mental health problems but a shortage of services, group therapy is offering new hope

The tricky economics of subsidising psychedelics for mental health therapy

Menopausal mood swings can signal more serious mental illness

Climate-related disasters leave behind trauma and worse mental health. Housing uncertainty is a major reason why.

Supporting student mental health and well-being has become a priority for schools. This was the case even prior to the increased signs of child and youth mental health adversity in and after the pandemic.

Supporting student mental health is important because students of all ages can experience stressors that negatively affect their well-being and sometimes lead to mental health diagnoses.

However, some have suggested we can either support academic success or mental health — and that mental health is more important than academic achievement.

However, we can and should support both academic success and mental health — because they affect each other.

As a researcher who examines school-based mental health and also as a former school psychologist, it’s clear to me that one of the best ways to support mental health is to support academic development, especially early in children’s education.

Well-being in education

Well-being in educational settings involves all aspects of students’ lives: physical, cognitive, social and psychological functioning.

Education policymakers, schools

and educators must attend to student well-being holistically rather than targeting one area at the expense of other areas.

A great deal of research shows that early academic performance predicts mental health and wellbeing. Most of the research showing this relationship between well-being and academic success is in the area of reading.

Recent reports from both Ontario and Saskatchewan human rights commissions highlighted the important role of strong reading instruction for student well-being, confidence and academic engagement.

reading abilities, positive outcomes

In the example of reading and mental health, gaining reading skills increases positive student outcomes. Good readers report being more satisfied with their lives.

Later, they have fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression. Teachers rate students with strong reading skills as more prosocial and as having fewer behaviour problems.

These students are also more confident, have higher emotional intelligence and demonstrate more empathy. These positive outcomes are related to reading skill

development, an important early indicator of academic success.

Being a poor reader, however, increases the risk for poor outcomes. Weak readers in early grades are more likely to have behavioural problems later. They also have poorer self-concept and self control, difficulty with relationships, shame, anxiety, depression, suicidality and delinquency.

Students who drop out of school are more likely to be poor readers, and poor readers are more likely to be involved with the criminal justice system. It is particularly telling that one of the best ways to keep youth from re-offending is to teach them to read.

The relationship between dyslexia and poor well-being and mental health further reveals the interaction between academic success and mental health.

Students with dyslexia, which is characterized by difficulties gaining reading skills, have more difficulty making friends, and having friends is an integral part of mental health.

They are also more likely to be bullied and to have low selfesteem. More specifically, having

Concerned about student mental health? How wellness is related to academic achievement Concerned about student mental health? How wellness is related to academic achievement

dyslexia increases the risk for also having anxiety, depression and behavioural problems.

Equity, reading instruction and well-being

Further, students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds are at greater risk both of not gaining adequate reading skills and of worse mentalhealth outcomes.

Language and literacy researchers Joan F. Beswick and Elizabeth A. Sloat contend that adequate access to strong reading

instruction is a social justice issue. Their research, and other findings, document how students from poorer neighbourhoods are less likely to receive adequate reading instruction. This disproportionately puts them at risk for mental health problems that reduce their well-being.

The relationship between academic success and well-being is not limited to elementary school reading. High-school students who achieve academically also have better mental health.

A two-way relationship

It is important to note, nevertheless, that the relationship between academic achievement and mental health is bidirectional.

Some research shows that poor mental health, including behaviour problems, affect academic outcomes.

The relationship between academic success and mental health is complex and likely interactive with both poor achievement and excessive competition for high marks

contributing to poor mental health. Academic performance and mental health each affect the other — either supportively or adversely.

Unhealthy academic competition

Strong academic performance supports mental health and wellbeing, but unhealthy levels of academic competition negatively impact mental health and wellbeing. Reining in this unhealthy focus on intense academic competition is important.

But only focusing on stressors of classroom competition in the

relationship between academic performance and mental health could have adverse effects in the short- and longer term: It could reduce the mental health of students by not supporting healthy academic growth that promotes mental health and well-being.

It could also fail to teach students practices or habits required to navigate challenges with resiliency.

Need to support both

If we want to support student well-being and mental health, we

need to support mental health directly by developing healthy school climates, teaching social emotional learning, and providing psychological services in schools.

But we also must support student academic success. This is the case especially as our most vulnerable students are at risk of both academic difficulty and mental health problems.

We don’t have to choose: we can and should support students’ academic success and mental health.

Authors:

Jo-An Occhipinti - Assoc. Professor and Head of Systems Modelling, Simulation & Data Science, Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney

Adam Skinner - Research Fellow, University of Sydney

Ian Hickie - Co-Director, Health and Policy, University of Sydney

Studies using traditional statistical methods have long indicated a link between unemployment and suicide. But until now it has been unclear if this relationship is causal. That is, even though the suicide rate is higher among the unemployed, can we definitely say unemployment directly leads to suicide?

We now can. Using advanced analytic techniques borrowed from ecology we have found clear evidence of a causal relationship.

Based on Australian Bureau of Statistics data on underutilised labour and suicide rates, we estimate that unemployment and underemployment in the 13 years from 2004 to 2016 directly

resulted in more than 3,000 Australians dying by suicide – an average of 230 a year.

These findings have profound political, economic, social and legal implications, particularly in light of government and central bank policies that “require” unemployment.

To test for causal effects of unemployment and underemployment on suicide, we applied a technique known as convergent cross mapping.

This method has been developed over the past decade to detect causality in complex ecosystems. Among other things, it has been used to study and show causal relationships between cosmic rays and global temperature, and humidity and influenza outbreaks. The period of our study (2004 to 2016) was bound by the quality of available data.

A clear relationship between unemployment and suicide challenges governments and institutions to take greater responsibility for the impact of policies and actions. It challenges the ethics of ideas that require some level of unemployment for economic efficiency.

For example, last month the Reserve Bank of Australia’s deputy governor, Michele Bullock, said the unemployment rate would have to rise to curb inflation. The central bank expects the unemployment rate to rise to 4.5% by the end of 2024. The current rate is 3.6%, with a further 6.3% of workers underemployed.

Reserve Bank of Australia deputy governor Michele Bullock addresses the Economic Society of Australia in Brisbane, July 19 2023.

As Bullock noted, “full employment” to most people means that anyone who wants a job can find one. But most economists believe there is a need for a certain level of unemployment to prevent inflation.

This level is known as the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU). It’s a theoretical concept, so there’s no way to be sure what the level should be, but before the pandemic the consensus was that it was about 5%.

These findings of the human cost of joblessness bolsters the case for policies to achieve full employment as well as reduce the negative consequences of unemployment, through providing a liveable income and strengthening mental health systems.

Why should the unemployed face deprivation, stigmatisation and despair when unemployment is a consequence of deliberate policy decisions?

We hope our findings will spur discussions about expanding unemployment benefits and labour market reforms to achieve greater job security. We also hope to provoke a deeper conversation

about the design of the economy and how it values people, beyond simply making money.

Building on the ideas of University of Queensland economist John Quiggin, the Mental Wealth initiative is proposing a social participation wage. Set at the rate of a liveable wage, it would recognise the social value of unpaid volunteer work, civic participation, environmental restoration, artistic and creative activity, and activities that strengthen the social fabric of nations.

Legally there are implications concerning duty of care and the obligation of governments and institutions to safeguard the wellbeing of the population. These findings should contribute to discussions about legal frameworks relating to employment, work health and safety, discrimination and human rights.

A direct causal relationship between unemployment and suicide demands a re-evaluation of policies, a prioritisation of full employment, adequate social safety nets to prevent poverty, mental-health system reform, and greater urgency in shifting to a wellbeing economy.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, you can call these support services, 24 hours, 7 days:

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Suicide Call Back Service: 1300 659 467

Kids Helpline: 1800 551 800 (for people aged 5 to 25)

MensLine Australia: 1300 789 978

StandBy - Support After Suicide: 1300 727 24

Exercise is even more effective than counselling or medication for depression. But how much do you need?

Authors

The world is currently grappling with a mental health crisis, with millions of people reporting depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions. According to recent estimates, nearly half of all Australians will experience a mental health disorder at some point in their lifetime.

Mental health disorders come at great cost to both the individual and society, with depression and anxiety being among the leading causes of health-related disease burden. The COVID pandemic is exacerbating the situation, with a significant rise in rates of psychological distress affecting one third of people.

While traditional treatments such as therapy and medication

Originally published on

can be effective, our new research highlights the importance of exercise in managing these conditions.

Our recent study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine reviewed more than 1,000 research trials examining the effects of physical activity on depression, anxiety, and psychological distress. It showed exercise is an effective way to treat mental health issues – and can be even more effective than medication or counselling.

Harder, faster, stronger

We reviewed 97 review papers, which involved 1,039 trials and 128,119 participants. We found doing 150 minutes each week of various types of physical activity

(such as brisk walking, lifting weights and yoga) significantly reduces depression, anxiety, and psychological distress, compared to usual care (such as medications).

The largest improvements (as self-reported by the participants) were seen in people with depression, HIV, kidney disease, in pregnant and postpartum women, and in healthy individuals, though clear benefits were seen for all populations.

We found the higher the intensity of exercise, the more beneficial it is. For example, walking at a brisk pace, instead of walking at usual pace. And exercising for six to 12 weeks has the greatest benefits, rather than shorter periods. Longer-

term exercise is important for maintaining mental health improvements.

How much more effective?

When comparing the size of the benefits of exercise to other common treatments for mental health conditions from previous systematic reviews, our findings suggest exercise is around 1.5 times more effective than either medication or cognitive behaviour therapy.

Furthermore, exercise has additional benefits compared to medications, such as reduced cost, fewer side effects and offering bonus gains for physical health, such as healthier body weight, improved cardiovascular and bone health, and cognitive benefits.

Exercise is believed to impact mental health through multiple pathways, and with short and longterm effects. Immediately after exercise, endorphins and dopamine are released in the brain.

In the short term, this helps boost mood and buffer stress. Long term, the release of neurotransmitters in response to exercise promotes changes in the brain that help with mood and cognition, decrease inflammation,

accomplishment, all of which are beneficial for people struggling with depression.

Not such an ‘alternative’ treatment

The findings underscore the crucial role of exercise for

and boost immune function, which all influence our brain function and mental health.

Regular exercise can lead to improved sleep, which plays a critical role in depression and anxiety. It also has psychological benefits, such as increased self-esteem and a sense of

managing depression, anxiety and psychological distress.

Some clinical guidelines already acknowledge the role of exercise – for example, the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Guidelines, suggest medication, psychotherapy and lifestyle changes such as exercise.

However, other leading bodies, such as the American

Psychological Association Clinical Practice Guidelines, emphasise medication and psychotherapy alone, and list exercise as an “alternative” treatment – in the same category as treatments such as acupuncture. While the label “alternative” can mean many things when it comes to treatment, it tends to suggest it sits outside conventional medicine, or does not have a clear evidence base. Neither of these things are true in the case of exercise for mental health.

Even in Australia, medication and psychotherapy tend to be more commonly prescribed than exercise. This may be because exercise is hard to prescribe and monitor in clinical settings. And patients may

be resistant because they feel low in energy or motivation.

But don’t ‘go it alone’

It is important to note that while exercise can be an effective tool for managing mental health conditions, people with a mental health condition should work with a health professional to develop a comprehensive treatment plan –rather than going it alone with a new exercise regime.

A treatment plan may include a combination of lifestyle approaches, such as exercising regularly, eating a balanced diet, and socialising, alongside treatments such as psychotherapy and medication.

But exercise shouldn’t be viewed as a “nice to have” option. It is a powerful and accessible tool for managing mental health conditions – and the best part is, it’s free and comes with plenty of additional health benefits.

There are days when it’s hard to face work, even when you aren’t physically sick. Should you take a day off for your mental health? If you do, should you be honest about it when informing your manager?

If you work for an organisation or in a team where you feel safe to discuss mental health challenges, you are fortunate.

Despite all the progress made in understanding and talking about mental health, stigma and prejudices are still prevalent enough to prevent many of us from willingly

letting bosses and coworkers know when we are struggling.

Mental health challenges come in different forms. For some it will be a severe lifelong struggle. For many others the challenge will be periods of feeling overwhelmed by stress and needing a break.

Globally, the World Health Organisation estimates about 970 million people – about one in eight people – is suffering a mental

disorder at any time, with anxietyrelated disorders affecting about 380 million and depression about 360 million.

These numbers have jumped about 25% since 2019, a rise credited to the social isolation, economic hardship, health concerns and relationship strains associated with the pandemic.

You’re not alone

But declining mental health is a longer-term trend, and it’s likely work demands have also played a role. Research identifies three main workplace contributors to mental ill-health: imbalanced job design when people have high job demand yet low job control, occupational uncertainty, and lack of value and respect.

This at least partly explains why depression and anxiety appear to be more prevalent in wealthy industrialised nations. In the United States, for example, it is estimated more than half of the population will experience a diagnosable mental disorder at some point during their lifetime.

Managerial attitudes changing slowly

For the modern workplace, therefore, mental health is increasingly part of the landscape. But preconceptions and prejudices are hard to shift. People with these challenges are still seen as weak, unstable or lacking competence.

These attitudes make it even harder for those with diagnosed mental health disorders to find meaningful work and progress in their careers.

Business executives and managers, like the rest of the population, have limited knowledge of mental health issues, or skills to manage it in the workplace.

This blind spot is reflected in the management research literature. The best most recent study of managerial understanding of mental health issues dates from 2014. It found only about one in ten human resource professionals and managers felt very confident in supporting employees with mental health challenges.

Even when managers understand there are implicit biases against employees with mental health challenges, they may still not know what to do about it.

So it is hardly surprising many employees remain reluctant to disclose their mental challenges to colleagues and managers, fearing a lack of understanding and potential negative consequences to their careers. But keeping it secret and “soldiering on” can make mental health even worse.

Framing the conversation

So what to do about it? Our research shows leadership is key.

For all organisations, cultural change can start with leaders and managers speaking more openly about their own mental health challenges. This empowers others to follow suit.

Energy Queensland, a government-owned utility with about 7,600 staff who are responsible for maintaining the state’s electricity distribution infrastructure, did this in 2017. Two of its workers, James Hill and Aaron McCann, now work as full-time “mental health lived experience advocates”. Hill previously worked for the corporation as an electrician and McCann as a lineworker. Both have lived through deep depression and suicidal thoughts.

Our research – which involved surveying more than 300 psychologists, psychiatrists and others employed in mental health services – suggests “lived experience” advocates encourage more open organisational cultures, helping to break down the stigma stopping others from admitting their own mental health challenges.

Globally, the World Health Organisation estimates about 970 million people – about one in eight people – is suffering a mental disorder at any time, with anxiety-related disorders affecting about 380 million and depression about 360 million.

Language choices are important too. How we talk about mental health can change how we think about it. Australia’s National Mental Health Commission, for example, refers to “mental health challenges” instead of “mental illness”. Such framing can help others to regard a mental health day as something that may be needed by anybody, not something for some who is “sick”.

For larger organisations, one innovative idea is to have “mental health advocates” – employees with personal experience of severe mental health challenges.

And a small number of organisations globally have introduced “wellness/wellbeing days” – an allotment of “no certificate required” days off, which can be used at any time, no questions asked.

As the challenge of squeezing greater productivity out of service sectors intensifies and competition for skills and talent escalates, those workplaces that acknowledge and accommodate the mental health stresses of modern life will be the ones with the competitive advantage.

The needs of people with mental health problems are increasing globally, especially following the turbulence of COVID.

Even before the pandemic, it was clear that despite more resources for mental health services in New Zealand and Australia, the prevalence of mental health problems was on the rise.

Mental health care in the current format is not meeting the needs of people living in the community, and there’s an ongoing shortage of mental health providers and relevant therapies.

In an unequal world, the rising burden of mental illness is often made worse by lack of access to quality evidence-based care. We need a new approach and it should focus on communities, scalability and equity.

In our recently published scoping review, we examine how group-based therapies could improve mental health outcomes.

Social factors are important

Many think of mental health care as involving a visit to a GP, psychologist or psychiatrist, a

prescription for medicines and perhaps individual “talk therapy”.

But we wanted to examine the value of “psychosocial” care – a broader approach that meets individual needs but also considers social factors such as housing, income or relationships.

Our review aimed to understand the value of groupbased interventions, recognising the importance of social networks and relationships for recovery across all communities.

Group interventions might typically mean weekly or monthly

meetings with a regular group experiencing mental distress. These would be facilitated by peers or community members who have been through similar difficulties.

Our study focuses on communities with fewer resources in South Asia, including Nepal, India and Bangladesh. It takes a regional approach because we know context matters in mental health, and one size doesn’t fit all.

We considered group interventions that shared a cultural context to see if they better engaged people on a local level. As such, our findings are also relevant for addressing the mental health care gap in Aotearoa New Zealand. The value of relationships and whānau care is already well recognised for Māori.

There are also promising recent studies showing the value of group interventions for mental health among young people, and

the contribution of kaimahi (nonregulated health workers) to improve outcomes for people with chronic conditions.

Group interventions have been shown to improve mental health outcomes in both community trials and systematic reviews. A recent meta-analysis of 81 studies showed talk therapy is the best initial treatment for depression.

If psychosocial interventions were a pill, their effectiveness would be trumpeted globally. Yet Western biomedicine (mental health care that requires psychiatrists and psychologists to deliver it) continues to command the majority of resources because of hierarchies and global economic structures that privilege psychiatry and medicines.

As well as being effective, there are other advantages

to group-based interventions because they:

- do not rely on expensive specialist providers

- can be delivered in communities and therefore improve access to care

- are responsive to local contexts such as groups in rural areas

- improve outcomes for groups that typically experience worse health, including new migrants to New Zealand

- increase engagement with mental health services

- and are highly cost-effective and scalable.

Group therapy improves mental health and social connection and is at least as effective as individual therapy.

It can be used for a wide range of mental health problems and is more cost-effective than one-to-one individual therapy. In communities

that have a more collective approach to health and wellbeing, such as Indigenous groups, mental health care delivered in groups can better reflect these values. This in turn may increase accessibility and uptake.

Most quantitative health studies only ask whether a particular intervention works. But we used an approach that looks for how interventions work by examining the contexts, mechanisms and outcomes.

As well as examining effectiveness, a “realist” evaluation seeks to provide an explanatory analysis of how and why complex social interventions lead to improved health outcomes. This helped us assess what works, for whom and in what circumstances.

In this review of 42 peerreviewed research publications, we identified five key mechanisms that groups offer to improve mental health:

1. They increase opportunity to be part of trusted relationships, which is a key social determinant of health. Group members described new friendships that continue after the intervention was over.

2. They trigger a sense of social inclusion and support, meaning people access resources and services more easily. Social inclusion is an important factor that determines mental health. Studies gave examples of how group members supported each other emotionally and with child care, agricultural and home responsibilities.

3. Groups can strengthen people’s ability to manage mental distress because they provide an

opportunity to rehearse and use mental health skills and knowledge in a safe social space. This is key to building communication skills and self esteem.

4. They trigger a sense of belonging, and members can manage emotions better. This enabled behaviour changes. For example, widows in northeast India described how they were able to identify and control feelings of anger because of their sense of connection with the group.

5.Groups provide a sense of collective strength and can act collaboratively for their own wellbeing. Group interventions are particularly beneficial for minorities, such as non-binary and transgender people, who experience higher rates of mental distress as well as social exclusion. A group can offer social support and affirmation, which have also been identified as key mental health determinants.

These mechanisms are relevant in Aotearoa New Zealand as well as across the wider South Asian region we studied. The recent government inquiry into mental health and addiction, He Ara Oranga, underlined the value of non-biomedical and local solutions for mental health, including therapeutic groups. It called for a move from “big psychiatry” to “big community”.

Group therapy fits well with a community approach as it can meet mental health needs without medicines, hospitals or expensive professionals. Psychosocial group therapies do not seek to replace formal mental health care. They complement it by providing accessible, costeffective care in communities and among people who have unmet mental health needs.

Authors Cathy Mihalopoulos Professor, Monash University

Chris Langmead Professor, Monash University

Australia is the world’s first country to legalise the medical use of psychedelics. But not everyone is sure the timing is right. There are still major issues to work out for this move to benefit those most in need.

In particular, there is the question of whether psychedelic medicines will be publicly subsidised, given the lack of data about their cost-effectiveness compared with other treatments.

From July 1 2023, authorised psychiatrists will be able to prescribe psilocybin and MDMA for post-traumatic stress disorder and psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression, to be used in conjunction with psychotherapy.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), which regulates medicines and medical devices in Australia, made this decision in February, reclassifying psilocybin and MDMA from “Schedule 9” (prohibited substances, only legally available for use in research) to “Schedule 8” (controlled substances).

Many in the field were surprised. Advocacy group Mind Medicine Australia, which lobbied hard for the decision, was delighted. But mental health experts such as former Australian of the Year Patrick McGorry questioned the sufficiency of evidence.

The TGA considered the effectiveness and safety of psilocybin and MDMA, as the regulator is supposed to do, but not their cost-effectiveness. This is not a requirement of TGA approval processes, but it is for the regulatory bodies that must approve these treatments for a public subsidy.

The paucity of such evidence is going to be a high hurdle.

Will they be subsidised?

How much will such therapy cost? One estimate is $20,000 to $30,000, comprising the cost of the medication and therapists’ time for sessions.

The pharmaceutical-grade psilocybin and MDMA used in Australian clinical studies has largely been supplied free by USbased not-for-profit organisations such as the Usona Institute and Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. The bureaucratic requirements to import these medications include a permit from the TGA and an import licence and permit from the Office of Drug Control.

Increasing supply will require streamlining these import controls. There is also work to be done on the potential for local production. But for now the major determinant of costs for patients will be if the medicines and therapy are subsidised, as many psychological treatments and most psychiatric medications are now.

A subsidy for the psilocybin/ MDMA component will require approval by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee, the independent body of medical

Services Advisory Committee (MSAC), which is not a statutory committee like the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee but has a similar function.

To date there are no published studies on psilocybin’s costeffectiveness, and only three on MDMA – all on its use in treating PTSD.

The first of these studies was published in 2020, the second in February 2022 and the third

experts that advises the federal health minister on which drugs should be listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

This will require a detailed submission (usually from the pharmaceutical supplier) explaining how the medicine will be prescribed, its effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness compared with alternatives. Submissions must also include budget impact analysis – that is, how much it will cost if the medicine is listed on the PBS.

A subsidy for the psychotherapy component will require listing on the Medicare Benefits Schedule, which funds services such as blood tests, diagnostics and allied health services. This will need endorsement from the Medicare

in March 2022. All three used economic modelling to to simulate long-term benefits and costs of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy compared with standard health care, extrapolated from the results of clinical trials (involving a few hundred people).

All three conclude MDMAassisted therapy is a potentially cost-effective treatment for people with chronic and severe PTSD. However, the modelling assumes the effects of MDMAassisted psychotherapy taken from clinical trials of relatively short durations (with maximum follow up of 18 weeks) will extend over 10 to 30 years. This may be overly optimistic. They were also based

on the treatment patterns and costs from the US that differ to those in Australia.

PBAC and MSAC will likely need to carefully weigh this type of evidence to make an assessment about cost-effectiveness.

Another issue to be carefully considered is how many people will likely use these medicines in routine practice. Such estimates are complicated by the risk of off-label use – psychiatrists prescribing psilocybin and MDMA for purposes not listed by the TGA.

An estimated 40–75% of anti-psychotic medicine use is “off-label”. For example, the antipsychotic medicine quetiapine is registered for treating schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, but is often used off-label for conditions such as anxiety or insomnia. This is despite the rules for prescribing quetiapine (the prescriber must state why they are prescribing it).

Allowing only authorised prescribers of psilocybin and MDMA may reduce the risk but not eliminate it. It could mean the cost of the medicines to the health budget ends up being a lot higher than estimated.

The upshot of all this means, in practice, Australia is still a way off from offering a public subsidy for these psychedelic treatments. Which means, come July 1, the number of Australians able to afford these treatments will be small.

Author Tania Perich Career Development Fellow, Western Sydney University

Most women expect to experience the effects of hormonal changes when they come to menopause and many anticipate increased irritability and mood swings. But mood swings that can be just an annoyance for some women can develop into something more serious for others.

Menopause usually begins around the age of 50, when the body’s production of oestrogen and progesterone slows. This can

Although some women can have an episode of depression for the first time during menopause, women with a history of recurrent depression are up to 4.5 times more likely to experience another episode of depression at the start of menopause than other women at this stage of life.

Anxiety disorders (generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder and social anxiety disorder) are the most common of the mental health

leads to a range of effects such as hot flushes, vaginal dryness, breast tenderness and trouble sleeping. These symptoms can last around five years.

Menopausal hormone fluctuations can have a significant impact on women’s mental health, with some women more vulnerable to these changes than others. These mental health problems require specific treatment and support.

Women are two to four times more likely to have an episode of major depression during menopause than at other times in their lives.

problems, with around 25% of the population experiencing one in the last 12 months.

But despite anxiety symptoms and panic attacks being commonly reported during menopause, little is known about their link with menopause.

Oestrogen has a protective effect against psychotic symptoms for women, due to its modulating effect on the neurotransmitter dopamine.

Excess dopamine is one of the neurological changes seen in patients with schizophrenia, a mental illness that causes

episodes of delusions and hallucinations.

Women with an existing diagnosis of schizophrenia may be at increased risk of an episode as their production of oestrogen decreases.

While the causes of schizophrenia are a complex mix of genes, your early development and stress, some women develop schizophrenia for the first time after menopause.

Eating disorders affect women across their lifespan, and often begin at the first major period of hormonal change: puberty.

But researchers are beginning to understand the hormonal

changes that occur during menopause also increase the risk of developing an eating disorder, such as anorexia, bulimia and binge eating.

Once again, the increased risk is due to fluctuations in oestrogen, which plays an important role in how we regulate our food intake, affecting feelings of hunger, satiety after eating and weight gain.

Bipolar disorder is a serious mental health disorder affecting up to 2% of Australians. It causes bouts of severe depression and episodes of increased energy, known as mania.

Our research found that women with bipolar disorder may be

uniquely affected by menopause in many ways. Disturbances in sleep due to hot flushes, for instance, can affect the onset of depression and mania.

Planning for good mental health

It is important for women with a history of mental health conditions to plan their mental health care when menopause begins.

Women without a history of mental illness should be aware of the risks and talk to their GP prior if they notice persistent changes in mood, or other concerning symptoms.

GPs can prescribe medication and refer to psychologists for Medicare-subsidised counselling, or to psychiatrists for more specialised care.

It is important for women with a history of mental health conditions to plan their mental health care when menopause begins.

Housing uncertainty is a major reason why.

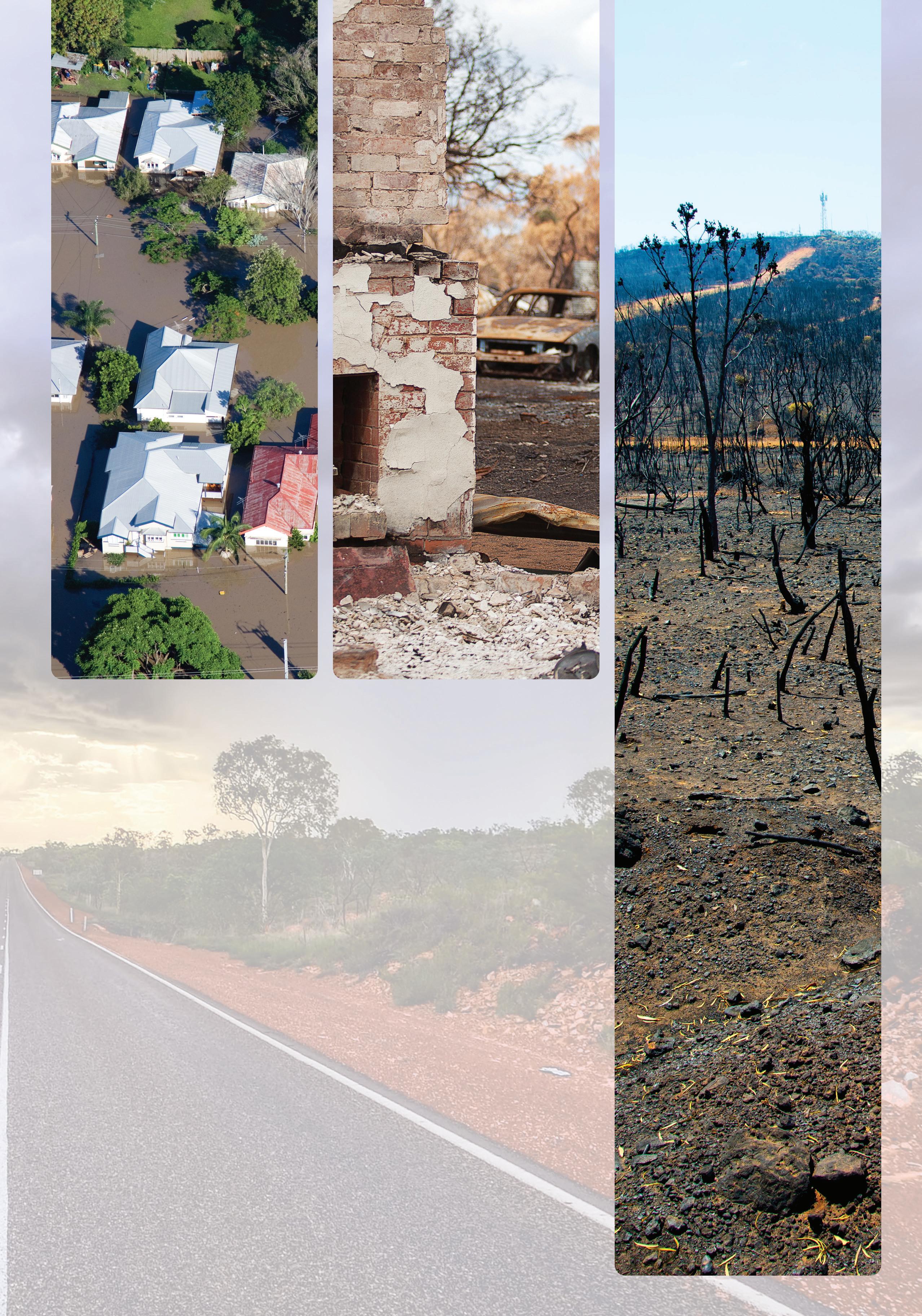

Australia, the world’s driest inhabited continent, is particularly vulnerable to climate-related disasters such as droughts, bushfires, storms and floods. In 2020, we were one of the top ten nations in the world for economic damage caused by disasters.

Recent catastrophic climatelinked disasters are etched into our communal psyche. The 2009 Black Saturday bushfires, where

173 people died and over 2,000 homes destroyed. The Black Summer bushfires in 2019–20, with 26 deaths and almost 2,500 homes destroyed. The triple La Nina from 2020–2022 caused flooding across the east coast, with last year’s claiming 23 lives and an estimated A$4.8 billion in property damage.

These climate-fueled disasters have immediate health impacts, from injury to distress and

Authors Ang Li

Research Fellow, NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Healthy Housing, Centre for Health Policy, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne

Mathew Toll Research Associate, NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Healthy Housing, Centre for Health Policy, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne

Rebecca Bentley Professor of Social Epidemiology and Director of the Centre of Research Excellence in Healthy Housing at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne

Originally published on

trauma. Less is known about the long-term effects on people who survived them.

Our new research in Lancet Planetary Health explored this over a longer time frame. We found disasters have a long tail – particularly around housing. As you might expect, people hit by disasters have worse mental and physical health in the year afterwards. But this effect lasts longer, with affected people

reporting worse mental health, worse emotional health and worse social functioning for two more years. Difficulty finding a place to stay is a large part of this.

As we plan for a future with intensifying natural disasters, governments must find ways to offer flexible housing support.

Our research involved around 2,000 people – half affected by disasters and half unaffected. All had responded to the longrunning HILDA survey. We compared data from the two groups over the decade to 2019. People were tracked up to eight years.

In this data were clear signs of the long tail of disaster. If your home had been damaged

by climate-related disasters, you were more likely to have worse health and wellbeing compared to a person from a similar background who had not been affected by disaster. We could see this negative mental health effect two years after the disaster. The effect was meaningfully large compared to other environmental factors weighing on health such as residential noise.

The way you lived also made a difference. People already affected by housing affordability stress – where rent or mortgage takes more than 30% of income – had bigger health losses after the disaster. This was similar for those in poor quality housing. Another major risk factor was a preexisting mental or physical health issue.

We’ve long known unaffordable and insecure housing is strongly linked to worse mental and physical health. If you don’t know where you’re going to live in a month’s time, it causes intense stress.

There was another divide, too – renters and owners. After a climate-related disaster, owners with a mortgage were more likely to suffer housing affordability stress for the next two years. This longer tail is likely due to shortterm relief measures running out.

By contrast, renters were more likely to face uncertain housing or forced relocation soon after the disaster. That’s likely due to Australia’s insecure tenure rights, which offer less protection against forced moves than comparable countries in Europe. Other factors include

the ongoing shortage of rental properties, and the fact rentals tend to suffer more damage in disasters and have less access to recovery resources.

This divide suggests we’ll need different approaches for different populations. In particular, this means offering medium-term help as well as short-term help for those who are highly vulnerable or in precarious housing conditions, like those left homeless after the devastating Lismore flood.

As authorities plan for a future with more intense disasters, they must not forget housing.

Many communities will become more vulnerable, from towns next to a river to cities surrounded by

forest. Governments have a responsibility to develop disaster preparedness and resilience –particularly around housing.

What we’re seeing now with post-disaster housing vulnerability is an unintended consequence of leaving housing to the market system.

That means finding flexible forms of housing support so we can respond to disasters as they

We’ve long known unaffordable and insecure housing is strongly linked to worse mental and physical health. If you don’t know where you’re going to live in a month’s time, it causes intense stress.

happen. This will reduce longerterm damage to health.

What does this look like? It might include:

- certainty for tenants that their tenure is secure immediately after a disaster

- support for homeowners to prepare for and recover from disasters

- safe, secure and high quality accommodation over short and long term for people who have lost their homes

- avoiding building in disaster prone areas and relocation of people living in high risk or uninsurable areas

- increasing the stock of climate resilient housing. Valuable work in this area has been carried out by local councils.

One thing is certain – doing what we’ve always done isn’t enough now. It certainly won’t be enough in a hotter world.