July–August 2025 Program

Pictures at an Exhibition

Mozart and the Mendelssohns

Journey to the Americas

Quick Fix at Half Six: Dvořák‘s Cello Concerto Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto

July–August 2025 Program

Pictures at an Exhibition

Mozart and the Mendelssohns

Journey to the Americas

Quick Fix at Half Six: Dvořák‘s Cello Concerto Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto

In the first project of its kind in Australia, the MSO has developed a musical Acknowledgement of Country with music composed by Yorta Yorta composer Deborah Cheetham Fraillon ao, featuring Indigenous languages from across Victoria.

Generously supported by Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and the Commonwealth Government through the Australian National Commission for UNESCO, the MSO is working in partnership with Short Black Opera and Indigenous language custodians who are generously sharing their cultural knowledge.

The Acknowledgement of Country allows us to pay our respects to the traditional owners of the land on which we perform in the language of that country and in the orchestral language of music.

As a Yorta Yorta/Yuin composer, the responsibility I carry to assist the MSO in delivering a respectful acknowledgement of country is a privilege which I take very seriously. I have a duty of care to my ancestors and to the ancestors on whose land the MSO works and performs. As the MSO continues to grow its knowledge and understanding of what it means to truly honour the First People of this land, the musical acknowledgement of country will serve to bring those on stage and those in the audience together in a moment of recognition as we celebrate the longest continuing cultures in the world.

—Deborah Cheetham Fraillon ao

Our musical Acknowledgement of Country, Long Time Living Here by Deborah Cheetham Fraillon ao, is performed at MSO concerts.

The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra is Australia’s preeminent orchestra, dedicated to creating meaningful experiences that transcend borders and connect communities. Through the shared language of music, the MSO delivers performances of the highest standard, enriching lives and inspiring audiences across the globe.

Woven into the cultural fabric of Victoria and with a history spanning more than a century, the MSO reaches five million people annually through performances, TV, radio and online broadcasts, as well as critically acclaimed recordings from its newly established recording label.

In 2025, Jaime Martín continues to lead the Orchestra as Chief Conductor and Artistic Advisor. Maestro Martín leads an Artistic Family that includes Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor – Learning and Engagement Benjamin Northey, Cybec Assistant Conductor Leonard Weiss, MSO Chorus Director Warren Trevelyan-Jones, Composer in Residence Liza Lim am, Artist in Residence James Ehnes, First Nations Creative Chair Deborah Cheetham Fraillon ao, Cybec Young Composer in Residence Klearhos Murphy, Cybec First Nations Composer in Residence James Henry, Artist in Residence, Learning & Engagement Karen Kyriakou, Young Artist in Association Christian Li, and Artistic Ambassadors Tan Dun, Lu Siqing and Xian Zhang.

The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra respectfully acknowledges the people of the Eastern Kulin Nations, on whose un‑ceded lands we honour the continuation of the oldest music practice in the world.

Tair Khisambeev

Acting Associate Concertmaster

Anne-Marie Johnson

Acting Assistant Concertmaster

David Horowicz*

Peter Edwards

Assistant Principal

Sarah Curro

Dr Harry Imber *

Peter Fellin

Deborah Goodall

Karla Hanna

Lorraine Hook

Jolene S Coultas*

Kirstin Kenny

Eleanor Mancini

Anne Neil*

Mark Mogilevski

Michelle Ruffolo

Anna Skálová

Kathryn Taylor

Matthew Tomkins

Principal

The Gross Foundation*

Jos Jonker

Associate Principal

Monica Curro

Assistant Principal

Dr Mary Jane Gething AO*

Mary Allison

Isin Cakmakçioglu

Emily Beauchamp

Tiffany Cheng

Glenn Sedgwick*

Freya Franzen

Cong Gu

Andrew Hall

Robert Macindoe

Isy Wasserman

Philippa West

Andrew Dudgeon AM*

Patrick Wong

Cecilie Hall*

Roger Young

Shane Buggle and Rosie Callanan*

Violas

Christopher Moore Principal

Lauren Brigden

Katharine Brockman

Anthony Chataway

Peter T Kempen AM*

William Clark

Morris and Helen Margolis*

Aidan Filshie

Gabrielle Halloran

Jenny Khafagi

Margaret Billson and the late Ted Billson*

Fiona Sargeant

Learn more about our musicians on the MSO website. * Position supported by

David Berlin

Principal

Rachael Tobin

Associate Principal

Elina Faskhi

Assistant Principal

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio*

Rohan de Korte

Andrew Dudgeon AM*

Rebecca Proietto

Peter T Kempen AM*

Angela Sargeant

Caleb Wong

Michelle Wood

Andrew and Theresa Dyer*

Double Basses

Jonathon Coco

Principal

Stephen Newton

Acting Associate Principal

Benjamin Hanlon

Acting Assistant Principal

Rohan Dasika

Aurora Henrich

Suzanne Lee

Flutes

Prudence Davis

Principal

Jean Hadges*

Wendy Clarke

Associate Principal

Sarah Beggs

Piccolo

Andrew Macleod Principal

Oboes

Johannes Grosso Principal

Michael Pisani

Acting Associate Principal

Ann Blackburn

Margaret Billson and the late Ted Billson*

Clarinets

David Thomas Principal

Philip Arkinstall

Associate Principal

Craig Hill

Rosemary and the late Douglas Meagher *

Bass Clarinet

Jonathan Craven Principal

Bassoons

Jack Schiller

Principal

Dr Harry Imber *

Elise Millman

Associate Principal

Natasha Thomas

Patricia Nilsson* Contrabassoon

Brock Imison Principal

Horns

Nicolas Fleury Principal

Margaret Jackson AC*

Peter Luff

Acting Associate Principal

Saul Lewis

Principal Third

The late Hon. Michael Watt KC and Cecilie Hall*

Abbey Edlin

The Hanlon Foundation*

Josiah Kop

Rachel Shaw

Gary McPherson*

Trumpets

Owen Morris Principal

Shane Hooton

Associate Principal

Glenn Sedgwick*

Rosie Turner

Dr John and Diana Frew*

Trombones

José Milton Vieira

Principal

Richard Shirley

Bass Trombone

Michael Szabo

Principal

Tuba

Timothy Buzbee

Principal

Timpani

Matthew Thomas Principal

Percussion

Shaun Trubiano Principal

John Arcaro

Tim and Lyn Edward*

Robert Cossom

Drs Rhyl Wade and Clem Gruen*

Harp

Yinuo Mu

Principal

Pauline and David Lawton*

For a list of the musicians performing in each concert, please visit mso.com.au/musicians

The MSO’s return to Europe brings Australian music to the world stage.

This August, after an 11-year hiatus, the MSO will showcase Melbourne’s symphonic voice across Europe, performing distinctively Australian compositions alongside established classical masterpieces under the baton of Chief Conductor Jaime Martín. In the past, Australia has looked to Europe as the cradle of the orchestral canon; now, the MSO is bringing a confident and boldsounding Australian orchestra to the stages of Europe.

MSO Chair Edgar Myer noted that this return to European concert halls after more than a decade represents an important opportunity to showcase Melbourne’s cultural identity to international audiences while highlighting the orchestra’s artistic excellence.

‘The decision to embark on the Europe Tour,’ said Myer, ‘represents a leap of faith that reflects a braver, bolder, more culturally ambitious company, one that all Melburnians can be proud of.’

Following a performance at the renowned Edinburgh International Festival on 22 August, the MSO will travel through Spain, Italy and Germany before concluding the tour with a final UK appearance in the BBC Proms at London’s Royal Albert Hall. This marks the MSO’s first international tour with a full orchestra since our North American engagements across four cities in 2019.

The Edinburgh concert presents a thoughtfully curated program to authentically reflect our MSO at its best. Audiences will experience the world premiere of a commissioned work by Deborah Cheetham Fraillon, Treaty,

featuring acclaimed First Nations artist and cultural songman William Barton as soloist on the yidaki (didgeridoo).

‘It’s the second work I’ve written for the MSO that features William, and this work has a special significance,’ explains Cheetham Fraillon AO. ‘Right now, in Australia, Victoria is leading the way in truth telling and justice for First Nations people. To honour and highlight this process of treaty, and to help initiate for some a conversation about the process of treaty and the need for it, is an extraordinary opportunity.’

Framing this contemporary Australian centrepiece is Elgar’s evocative In the South (itself the work of a composer on tour, in Italy) and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, concluding with its powerful finale, The Great Gate of Kyiv. This thrilling program will be repeated in the magnificent Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg.

In Edinburgh, the MSO joins an illustrious roster of international ensembles, including the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Budapest Festival Orchestra and the MSO’s own artistic partner, the NCPA (National Centre for the Performing Arts) Orchestra from Beijing. The prestigious festival, founded in 1947, continues its tradition of transcending political boundaries through global celebration of the performing arts under the direction of Scottish violinist Nicola Benedetti.

The other Australian work in the tour repertoire is Margaret Sutherland’s 1950 symphonic poem Haunted Hills, a lush

I am particularly thrilled to bring the MSO to my hometown of Santander. It’s where I grew up, where my family still live, and most importantly, where I was first introduced to orchestral music by my father.

—Jaime

Martín

evocation of the Dandenong Ranges. It has been matched with Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 (with soloist Khatia Buniatishvili) and Dvořák’s Sixth Symphony for concerts in the Südtirol Festival (Merano) and at the BBC Proms.

The tour holds additional significance as it includes the Santander International Festival on Spain’s northern coast –the birthplace of Jaime Martín. This picturesque city on the Bay of Biscay will provide a fitting location to celebrate the Orchestra’s European journey, with Martín planning a party coinciding with his own 60th birthday to commemorate the tour.

The MSO carries a distinguished international touring legacy, having been the first Australian orchestra to tour internationally, in 1965. This year’s European engagement represents a continuation of that pioneering spirit and an opportunity to promote Australian cultural excellence on the world stage.

Adapted from an article by Nicole Lovelock

The MSO’s UK and Europe Tour is proudly supported by the Gandel Foundation, Metal Manufactures Electrical Merchandising, and MSO Europe Tour Circle patrons.

Extend your musical journey through the MSO’s Patron Program.

An annual donation of $500 or above brings you closer to the music and musicians you love. Enjoy behindthe-scenes experiences and exclusive gatherings with MSO musicians and guest artists, while building social connections with other music fans and directly supporting your Orchestra.

Scan the QR code to become an MSO Patron today.

Artists

Friday 27 June at 11 am

Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Jaime Martín conductor

Program

Ravel Alborada del gracioso [8’]

Mussorgsky orch. Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition [35’]

CONCERT EVENTS

Pre-concert talk: Learn more about the concert with MSO Head of Operations and percussionist Callum Moncrieff at 10:45am in the Stalls Foyer (Level 2) at Hamer Hall.

Running time: 1 hour. Timings listed are approximate.

Chief Conductor and Artistic Advisor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra since 2022, and Music Director of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra since 2019, with those roles currently extended until 2028 and 2027 respectively, Spanish conductor Jaime Martín also took up the role of Principal Guest Conductor of the BBC National Orchestra of Wales last year, and has held past positions as Chief Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland (2019–2024), Principal Guest Conductor of the Orquesta y Coro Nacionales de España (Spanish National Orchestra) (2022–2024) and Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of Gävle Symphony Orchestra (2013–2022).

Having spent many years as a highly regarded flautist, Jaime turned to conducting full time in 2013. Recent and future engagements include appearances with the London Symphony Orchestra, Dresden Philharmonic, Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as a nine-city European tour with the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Jaime Martín is a Fellow of the Royal College of Music in London, and in 2022 the jury of Spain’s Premios Nacionales de Música awarded him their annual prize for his contribution to classical music.

Jaime Martín’s Chief Conductor Chair is supported by the Besen Family Foundation in memory of Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AC.

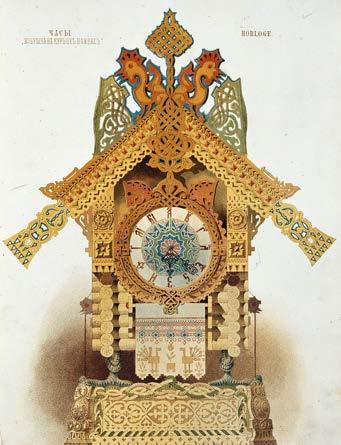

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

Alborada del gracioso (Morning Song of the Jester)

Like many French composers in the l9th and early 20th centuries, Ravel was fascinated by Spain, a fact reflected in many of his works (from the one-act opera L’Heure espagnole to the celebrated Bolero). This fascination was not primarily the result of personal experience. The Spain of Alborada del gracioso (or, for that matter, of Bizet’s Carmen or Debussy’s Ibéria) was not a real country, but rather an exotic, mysterious ideal of heady perfumes and vibrant colours, populated by passionate gypsies and dashing bullfighters: the Spain of travel brochures.

Alborada del gracioso was originally written for piano, as part of a set entitled Miroirs (Mirrors) which appeared in 1905. Several of Ravel’s orchestral works are transcribed from piano pieces: such is his genius as an orchestrator, however, that the orchestral and piano versions both have the status of originals. Each version is so perfectly conceived for its scoring that it seems impossible to imagine it in any other medium. Alborada is particularly interesting, in that its whole harmonic and rhythmic fabric is a powerful evocation of a guitar, being played by a virtuoso in the Spanish tradition – an ‘original version’, which does not exist and yet appears to predate the other two!

The timbres featured in Ravel’s orchestration (made in 1918) make the guitar references explicit, with much use of harp, and string pizzicato and harmonics, as well as an extensive percussion section (with particularly prominent parts for side drum and castanets). There are a number of specific

genres in Spanish folk music which bear the name ‘Alborada’ (literally ‘dawn song’), but Ravel was perhaps thinking more of the romantic mediæval idea of a farewell serenade sung by a lover, as he rides away from his beloved at dawn. The complete title, ‘Morning Song of the Jester’, aptly suggests the music’s volatile nature, by turns melancholy, playful and extravagant.

Elliott Gyger © Symphony Australia

Modest Mussorgsky (1839–1881)

orchestrated by Maurice Ravel

Pictures at an Exhibition

Promenade –

1. Gnomus (Gnome) Promenade –

2. Il vecchio castello (The Old Castle) Promenade –

3. Tuileries. Dispute d’enfants après jeux (Tuileries. Children quarrelling after play)

4. Bydło (Oxen) Promenade –

5. Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks

6. ‘Samuel’ Goldenberg und ‘Schmuÿle’

7. Limoges. Le marché. La grande nouvelle (Limoges Market. The Big News) –

8. Catacombæ. Sepulcrum romanum (Catacombs. A Roman Sepulchre) –Con mortuis in lingua mortua (With the Dead in a Dead Language)

9. The Hut on Hen’s Legs. Baba Yaga –

10. The Great Gate of Kyiv

Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition is piano music but it has inspired more orchestrations and arrangements than possibly any other piece of music. And it was one of these – Ravel’s brilliant and sophisticated orchestration from 1922 –that brought this remarkable music to widespread public attention, decades before it entered the piano recital repertoire courtesy of champions Vladimir Horowitz and Sviatoslav Richter.

Mussorgsky never intended to orchestrate Pictures at an Exhibition, and yet many musicians have felt that this vivid music called for orchestral colours. Among them have been conductors Henry Wood (who withdrew his 1915 effort after Ravel’s was published) and Leopold Stokowski, as well as Serge Koussevitzky, whose instructions to Ravel were that the orchestration be in

the style of Rimsky-Korsakov, the one composer who, surprisingly, didn’t attempt the task.

Ravel didn’t have access to Mussorgsky’s original music from 1874 – only the 1886 edition by Rimsky-Korsakov, compromised by misreadings and errors – but as best he could, he aimed for fidelity to Mussorgsky’s style, sublimating his own. It’s no accident that his orchestration was praised for not sounding like his ballet Daphnis et Chloé. Similarly, and despite Koussevitzky’s brief, Ravel avoided the showy glamour heard in Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade.

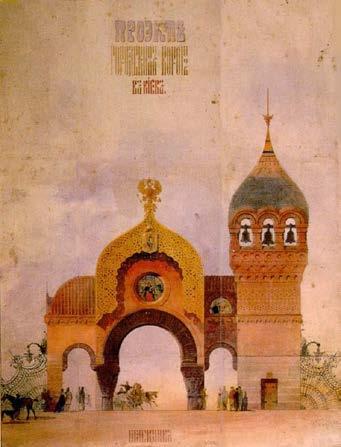

The exhibition of the title was a memorial in honour of Mussorgsky’s friend, the architect and artist Viktor Hartmann, who had died in 1873, at the age of 39. As an architect, he was notoriously bad at constructing ‘ordinary, everyday things’, but given palaces or ‘fantastic’ structures, his artist’s imagination was capable of astonishing creativity.

From hundreds of drawings, watercolours and designs, Mussorgsky chose ten –some showcasing Hartmann’s imagination, others reflecting his travels. His music places the listener at the exhibition itself, promenading from picture to picture in ‘Russian style’ with a lopsided alternation of five- and six-beat groupings.

(Mussorgsky said his own ‘profile’ could be seen in these promenades.) Then, pausing before each artwork, he takes us into its world.

Many of the gestures in Ravel’s orchestration have become so intimately associated with Mussorgsky’s music that their genius seems inevitable. The first picture, Gnomus, was really a caricature –a design for a nutcracker – and Ravel’s colours are grotesque and menacing, featuring the eerie effect of the strings sliding to flute-like harmonics. The Old Castle depicted a mediæval castle, with a solitary troubadour included for scale. Mussorgsky places the castle in Italy with a lilting siciliano rhythm but the melody has a mournful Russian character. Ravel, memorably, gives the minstrel a (BelgianFrench) saxophone!

The Tuileries painting depicted a group of shrieking children in the palace gardens. Mussorgsky was fond of children (as was Ravel) and his music captures the shapes of their speech. Curiously, though, these Parisian children seem to be calling for their nanny in Russian: ‘Nianya! Nianya!’ Ravel’s pristine orchestration features flute, oboe and clarinets.

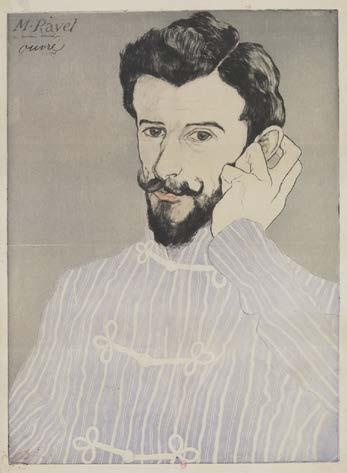

FROM LEFT: Costume design for the ballet Trilbi; Hartmann in the Paris catacombs

In Bydło (Oxen), through no fault of his own, Ravel departed from Mussorgsky’s original, which begins with heavy, thundering chords in the bass register of the piano. What we hear instead is a slow crescendo, emerging from the muted sound of bassoons, tuba, cellos and basses: an ingenious representation of the approach and passing of a Polish ox-drawn wagon.

The design that inspired Mussorgsky’s imaginary Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks survives: a whimsical egg costume. After the fourth and last Promenade, Ravel sets the scene with chirping flutes, fluttering violin trills, and the staccato tapping of chicks at their shells.

‘Samuel’ Goldenberg and ‘Schmuÿle’ refers to a pair of portraits depicting two Polish Jews – one rich, one poor. Mussorgsky probably named them himself (the Germanicised ‘Samuel’ for the wealthy Goldenberg and its Yiddish equivalent ‘Schmuÿle’) and he unites them in a timeless narrative – the poor man begging from a rich one. Goldenberg appears first – assertive and powerful –with (in Ravel’s orchestration) full strings. Then, in a stroke of genius to match the earlier use of the saxophone, Ravel casts a stuttering trumpet as Schmuÿle.

At Limoges Market gossip is the primary currency: ‘Important news,’ began

Mussorgsky’s scenario, ‘Monsieur de Puissangeout has just recovered his cow, Fugitive…’ A neighbour’s new dentures and another’s bulbous red nose are equally fascinating in this racing and brilliantly coloured miniature.

Another surviving painting shows Hartmann himself looking at the Paris catacombs by lanternlight, the inspiration for Catacombæ Sepulcrum romanum (Catacombs. A Roman Sepulchre) and Con mortuis in lingua mortua (With the Dead in a Dead Language). Cue gloomy brass sounds. Then, writes Mussorgsky alongside his dodgy Latin: ‘The creative spirit of the departed Hartmann leads me to the skulls and invokes them: the skulls begin to glow faintly.’ The introspective mood is sustained with an evocation of the Promenade theme in a minor key, which Ravel gives to the oboes and mournful cor anglais against shivering high strings.

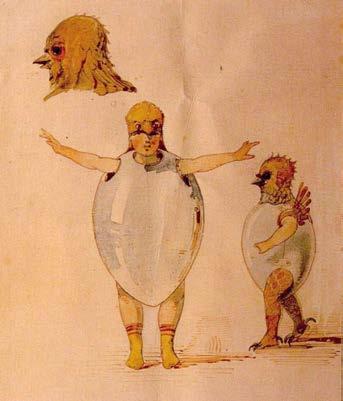

The final pair of pictures brings the music to a climax. Both images reveal Hartmann’s gift for grand and fantastic conceptions: the table clock in the form of Baba Yaga’s hut on hen’s legs and a

FROM LEFT: design for a clock in the Russian style showing Baba Yaga’s hut on hen’s legs; design for the Kyiv city gate

competition entry for a city gate with a cupola in the form of a Slavonic helmet. Unlike Western witches, Baba Yaga travels in a mortar propelled by a pestle – her broom is for sweeping over her tracks. Mussorgsky portrays Baba Yaga’s ride as much as her dwelling place with this terrifying and inexorable music (and, marked with a tempo of one bar of music per second, clocklike as well!).

Mussorgsky’s Great Gate of Kyiv conveys an ‘old heroic Russia’ with a Russian Orthodox chant (‘As you are baptised in Christ’), which Ravel gives to a choir of clarinets and bassoons in imitation of Russian reed organs. This is interrupted by a characteristically Russian peal of bells, which Ravel gives to everyone except the tubular bells and glockenspiel – these are held in reserve for the Promenade theme as it rings out one last time.

Yvonne Frindle © 2019

Thursday 3 July at 7:30pm Melbourne Town Hall

Friday 4 July at 7:30pm Frankston Arts Centre

Saturday 5 July at 7:30pm Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo

Artists

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Jaime Martín conductor

Johannes Grosso oboe

David Thomas clarinet

Jack Schiller bassoon

Nicolas Fleury horn

Program

Hensel (Fa. Mendelssohn) Overture in C major [11’]

Mozart Symphonie concertante for four winds, K.297b [32’]

Interval [20’]

Fe. Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4, Italian [28’]

CONCERT EVENTS

Organ recital: Calvin Bowman performs a free recital on the Melbourne Town Hall Grand Organ on 3 July at 6:30pm

Pre-concert talk: Learn more about the music with MSO Principal Third Horn Saul Lewis at 6:45pm at the Frankston Arts Centre (4 July) and Ulumbarra Theatre (5 July).

Running time: 1 hour 45 minutes including interval. Timings listed are approximate.

The MSO’s Bendigo performance is supported by AWM Electrical, Freemasons Foundation Victoria and the Robert Salzer Foundation.

“I’ve benefitted so much from the MSO. I love knowing that my support will enable others to benefit from MSO’s transformative music experiences.”

Jennifer Henry, MSO Guardian and Patron

Leaving a gift in your Will to the MSO ensures your story—and the orchestra you love—lives on in perpetuity. We are honoured to play an important role in your musical journey and invite you to become our next Guardian of the MSO.

Scan the QR code to learn more or call (03) 8646 1551 to speak with a member of the MSO Philanthropy team.

Chief Conductor and Artistic Advisor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra since 2022, and Music Director of the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra since 2019, with those roles currently extended until 2028 and 2027 respectively, Spanish conductor Jaime Martín also took up the role of Principal Guest Conductor of the BBC National Orchestra of Wales last year, and has held past positions as Chief Conductor of the National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland (2019–2024), Principal Guest Conductor of the Orquesta y Coro Nacionales de España (Spanish National Orchestra) (2022–2024) and Artistic Director and Principal Conductor of Gävle Symphony Orchestra (2013–2022).

Having spent many years as a highly regarded flautist, Jaime turned to conducting full time in 2013. Recent and future engagements include appearances with the London Symphony Orchestra, Dresden Philharmonic, Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as a nine-city European tour with the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Jaime Martín is a Fellow of the Royal College of Music in London, and in 2022 the jury of Spain’s Premios Nacionales de Música awarded him their annual prize for his contribution to classical music.

Jaime Martín’s Chief Conductor Chair is supported by the Besen Family Foundation in memory of Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AC.

Johannes Grosso was recently appointed Principal Oboe of the MSO. He has enjoyed an illustrious career in Europe, as solo oboe in the Frankfurt Opera House and as a member of the Budapest Festival Orchestra, having previously spent four years with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio-France, as well as regularly appearing as a guest principal with leading orchestras such as the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Bayreuth Festival Orchestra, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig and Bamberger Symphoniker.

As a concerto soloist, he won the 2014 Prague Spring International Music Competition. He also won the Giuseppe Tomassini International Competition (Italy) and Asian Double Reed Society Competition (Taiwan) and received second prize in the Fernand GilletHugo Fox Competition (USA), as well as the Végh Sándor Competition Prize (Hungary). These successes led to solo appearances working with conductors such as Christoph von Dohnányi, Daniele Gatti, Gábor Takács-Nagy, Tommas Guggeis, and with orchestras including the Czech Radio Orchestra, Prague Chamber Orchestra, Budapest Festival Orchestra, Frankfurter Opern- und Museumsorchester, the SchleswigHolstein Music Festival Orchestra and New Bach Collegium Leipzig.

Johannes also gives masterclasses and in 2018 he was appointed to the Norwegian Music Academy in Oslo.

David Thomas has been the Principal Clarinet of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra since 2000. Growing up in the Dandenong Ranges, he studied at the University of Melbourne with Phillip Miechel and later at the Vienna Conservatorium with Roger Salander. David has played as a member of the West Australian Symphony Orchestra and is a member of the Australian World Orchestra.

He has appeared as concerto soloist with the Melbourne, West Australian, Sydney, Tasmanian and Darwin symphony orchestras, performing works by Mozart, Copland, Debussy, Françaix and Brett Dean amongst others. Concertos have been written for him by Australian composers Ross Edwards, Philip Czapłowski and Nicholas Routley, and his recording of the Edwards concerto with the MSO conducted by Arvo Volmer has been released by ABC Classic.

David is involved in training the next generation of classical musicians at the Australian National Academy of Music, where he is the principal teacher of clarinet and head of the woodwind department.

Jack Schiller was appointed Principal Bassoon of the MSO in 2013. He previously held a contract position with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra as Associate Principal Bassoon and was an SSO Fellow under the mentorship of Matthew Wilkie. He regularly collaborates with colleagues and friends to play chamber music and is a founding member of the Melbourne Ensemble. As a chamber musician, he has performed at Musica Viva’s Huntington Estate Music Festival, the Australian Festival of Chamber Music in Townsville, Music By the Springs (Hepburn Springs), the Sydney Opera House Utzon Room and the Ukaria Cultural Centre in Adelaide. As a soloist, he has performed with the Melbourne and Tasmanian symphony orchestras, Orchestra Victoria and Melbourne Chamber Orchestra, and with the MSO he gave the premiere of Matt Laing’s concerto Of Paradise Lost. He also gave the premiere of The Song of the Wombat, a solo work by Rachel Bruerville.

Jack is an alumnus of the Australian National Academy of Music, where he studied with Elise Millman and won the concerto and chamber music competitions as well as the Director’s Prize. He has also studied with Mark Gaydon (Adelaide Symphony Orchestra), including two years at the Elder Conservatorium, and has been a member of the Australian Youth Orchestra.

Position supported by Dr Harry Imber

Nicolas Fleury began studying natural and French horns at the age of eight. On completing his studies in his native France – at the Nantes Conservatoire and later the Rueil Malmaison Conservatoire –he continued his education at the Royal College of Music under the guidance of Timothy Brown, Timothy Jones and Sue Dent. He graduated in 2009 with distinction and the Tagore Gold Medal.

Nico was appointed Principal Horn of the MSO in 2019. Previously he was Principal Horn in the Aurora Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, where he performed Mozart’s horn concertos and Britten’s Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, broadcast live on BBC Radio 3.

He appears frequently as a guest principal horn in orchestras such as the London Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, Academy of St Martin in the Fields, Orchestre de Chambre de Paris, Sydney Symphony Orchestra and Utah Symphony Orchestra. He has performed the most demanding works of the orchestral repertoire alongside conductors such as Andrew Davis, Charles Dutoit, Lorin Maazel, Esa-Pekka Salonen, Bernard Haitink, Andris Nelsons, Valery Gergiev, Neville Marriner and John Eliot Gardiner.

Position supported by Margaret Jackson AC.

Fanny Hensel’s only known concert overture begins as her listeners would have expected: with a slow introduction –announced by exposed notes for horns (no pressure!) and thoughtful exchanges between strings and woodwinds. This Andante section winds up with a tiny flute solo before scurrying violins (Allegro di molto) and fanfares propel the orchestra in the overture proper (‘with fire’).

Who were Hensel’s listeners? They were Berlin’s cultural elite and visiting celebrities, gathering in the Mendelssohn family mansion (correction: the mansion’s garden hall, with a capacity of 200 or so) for her exclusive Sunday Musicales.

For one particular Musicale, on 15 June 1834, members of the Königstadt Theater orchestra were enlisted to play a program including this overture. Reporting to her brother and confidant Felix Mendelssohn, she told him how, in rehearsal, the director had wickedly handed her the baton at the last minute, obliging her to conduct: ‘Had I not been so horribly shy, and embarrassed with every beat, I would’ve been able to conduct reasonably well.’ (In fact, she was a fine conductor, and an even better pianist than Felix.) Later, she writes how much fun it had been to hear the piece for the first time in two years, and that ‘everybody seemed to like it’.

The picture forms: a remarkable musician planning brilliant pro-am salon concerts, but also a member of Berlin’s ‘aristocratic bourgeoisie’, and married – her husband and champion, Wilhelm, was the Berlin court painter, her son was named for her favourite composers: Sebastian Ludwig Felix. It is class, even more than gender, that shaped Hensel’s musical activity

(effectively private and non-professional), and to some extent her brother’s too. Early in his career, Felix performed as a gentleman-amateur; it would have been unseemly to accept payment. Similarly, Fanny played in public on only three occasions, each time for charity. Felix held strong reservations about publishing his music and works such as his Italian Symphony remained unpublished at his death. Fanny embarked on the publication of her own works relatively late and only because she thought it might prove motivating.

Hensel’s privilege – with the expectation that for her, music could only ever be an ‘ornament’ – was a hindrance. By contrast, her poorer friend Clara Schumann enjoyed a flourishing career as a concert pianist. And yet Hensel’s talent could not be hidden from the world. On her untimely death in 1847, obituaries acclaimed her as an exalted artist. Her story was told – and works such as her songs and a very fine string quartet were performed – well into the 1920s. (The past 40 years have seen a revival of interest and the publication of works such as tonight’s overture.) But in one respect, the private nature of her musical practice may have freed her to take more risks, wittily playing with expectations even as she worked within the conventions of her time.

Yvonne Frindle © 2025

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

Symphonie concertante in E flat major for four winds, K.297b

I. Allegro

II. Adagio

III. Andantino con variazioni

Johannes Grosso oboe

David Thomas clarinet

Jack Schiller bassoon

Nicolas Fleury horn

In 1778, Mozart arrived in Paris, landing in the middle of a craze for music featuring more than one soloist with orchestra – the symphonie concertante. This new genre –part symphony, part concerto – was enormously popular at the time, showing off the skills of individual virtuosos from within the fine orchestras that were developing for public concerts. Later, in Salzburg, Mozart would compose his bestknown work in the genre, the peerless Sinfonia concertante for violin and viola. But while in Paris, he catered to French fashion with his concerto for flute and harp (a symphonie concertante in all but name), and a work for four wind instruments that has left a mystery in its wake.

On 5 April 1778, Mozart wrote from Paris to his father: ‘I am about to compose a symphonie concertante for flute, Wendling; oboe, Ramm; horn, Punto; and bassoon, Ritter.’ The musicians were new friends from the famous Mannheim orchestra and from Paris (Punto who ‘plays magnifique’). It was composed for the Concert Spirituel series directed by Joseph Le Gros, but apparently was never performed. In a letter from 1 May, Mozart refers to a ‘hitch’, alluding to ‘behind the scenes’ politics and suspecting Le Gros of suppressing it in favour of another composer, Cambini. Meanwhile, his four soloists were ‘quite in love’ with his symphonie concertante and when it wasn’t programmed as planned, Ramm and Punto had come to him in a rage. Later that year,

on 3 October, Mozart wrote that he intended to reconstruct the symphonie concertante from memory. He never did, presumably because the circumstances of having four such wind players never arose, and the manuscript, which Le Gros must have retained, is now lost.

In the 1860s, Mozart authority Otto Jahn found unsigned music which he believed was Mozart’s, but with clarinet instead of flute. There’s no proof this is the piece Mozart mentions in his letter. Some scholars think the orchestral sections are by Mozart, others not. All agree the solo passages have been adapted, and the three movements are all in the same key, something Mozart did in only one other piece (a wind serenade, K.375). But whether its Mozart birth-line is in order or not, this music has always seemed way too good to be neglected.

The typical symphonie concertante was light in character – less tightly written than a symphony and making more concessions to virtuosity – and this brilliant and expansive music is no exception. The orchestra presents the themes of the Allegro, including a strong motif that will be stated by the four soloists entering in unison. As the music continues, the soloists are presented individually and in different combinations. In the slow movement (Adagio) the four soloists share a thread of sustained songfulness. The last movement is a set of variations. The relative lack of display for the horn raises doubt as to whether the music was written for Punto, but oboe, clarinet and bassoon each have variations in which to shine.

This symphonie concertante for winds is, at best, the nearest we can get to a work in the genre by Mozart, but its survival in the repertoire is due to more than its attribution to him. The music pleases both connoisseurs and music lovers – further evidence, if you like, that it could be Mozart’s.

David Garrett © 2025

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847)

Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 90, Italian

I. Allegro vivace

II. Andante con moto

III. Con moto moderato

IV. Saltarello (Presto)

Mendelssohn’s travels in 1829–31 took him to Scotland, Wales, England, Paris and Vienna, but no ‘Grand Tour’ could be complete without Italy. The land of ‘bright skies and warmth’ inspired the sunny effervescence of his Italian Symphony, although it wasn’t completed until after he’d returned to the grey skies of Berlin.

The Italian Symphony is the creation of a young composer, optimistic and confident. Writing home, Mendelssohn described its rapid progress, saying: ‘it will be the most amusing piece I have composed, especially the last movement. I have not yet decided on the adagio, and I think I shall reserve it for Naples.’

Mendelssohn begins the first movement as he intends to go on: brilliantly with a breathless, bounding momentum. (The dance-like character is unusual for a symphonic first movement, but Mendelssohn wasn’t the first to begin with a skipping rhythm – Beethoven had been there before with his Symphony No. 7, also in A major.) The ‘undisguised commitment to pleasure’ (Thomas Grey) echoes the underlying spirit of the Roman Carnival, which Mendelssohn was experiencing for the first time. But he would have known what to expect, because he’d read Goethe’s Italian Journey:

The Roman Carnival is not really a festival given for the people but one the people give themselves… there are no fireworks, no illuminations, no brilliant processions. All that happens is that, at a given signal, everyone has leave to be as mad and foolish as he likes, and almost everything, except fisticuffs and

stabbing, is permissible. …everyone accosts everyone else, all goodnaturedly accept whatever happens to them, and the insolence and licence of the feast is balanced only by the universal good humour.

Good humour fills the Italian Symphony, but there’s a shift of mood for the second movement – the ‘adagio’ that Mendelssohn was saving for Naples. There he witnessed a religious procession and this movement is like a walking meditation, beginning with music that suggests mediæval plainchant and becoming more elaborate as flutes and violins spin their melodies above a solemn bass line.

In many ways, Mendelssohn’s symphony is a musical postcard. It’s full of images and scenes: the Lenten carnival, pilgrims… Perhaps the graceful third movement is music for a German tourist nostalgic for home. It isn’t called a minuet, but it occupies the same spot as that dance would have done in a Classical symphony. In the contrasting middle section, the horns and bassoons are given poetic music that suggests Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The finale (Presto or ‘as fast as possible!’) features two Italian dances: the leaping saltarello to begin and end, and in the middle a tarantella, the whirling dance supposedly recommended for spider bite victims. This movement has such an irresistible and joyous energy, it’s easy to overlook the fact that – almost until the end – it’s in the key of A minor, which in Mendelssohn’s day was associated with a tender and sorrowful character.

The Italian Symphony sounds effortless and fresh. Mendelssohn himself characterised it as a ‘cheerful’ rather than a ‘grand’ symphony, but he also considered it ‘the most mature thing’ he’d ever done, and it remains one of his most popular creations to this day.

Yvonne Frindle © 2012/2025

Artists

Thursday 17 July at 7:30pm

Saturday 19 July at 2:00pm

Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne

Friday 18 July at 7:30pm

Costa Hall, Geelong

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Miguel Harth-Bedoya conductor

Raphaela Gromes cello

Program

Jimmy López Fiesta! – Four pop dances for orchestra [10’]

Joe Chindamo Concerto for Orchestra [25’]

Interval [20’]

Dvořák Cello Concerto in B minor [40’]

CONCERT EVENTS

Pre-concert talk: Learn more about the concert with composers Matthew Hindson and Joe Chindamo at 6:45pm (17 July) and 1:15pm (19 July) in the Stalls Foyer on Level 2 at Hamer Hall and at 6:45pm (16 July) at Costa Hall.

Running time: 1 hour 50 minutes, including interval. Timings listed are approximate.

MSO’s Geelong performance is supported by AWM Electrical, Freemasons Foundation Victoria, the Robert Salzer Foundation and Geelong Friends of the MSO.

Peruvian conductor Miguel Harth-Bedoya is a master of colour, drawing idiomatic interpretations from a wide range of repertoire. He is Music Director Laureate of the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, where he was Music Director for 21 years, and recently completed seven years as Chief Conductor of Norwegian Radio Orchestra.

Having established himself early as Associate Conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, he continues to work at the top level of US orchestras, including the Chicago, Boston, Atlanta and Baltimore symphony orchestras, the Cleveland, Philadelphia and Minnesota orchestras, San Francisco Philharmonic and New York Philharmonic. With his immense personal charisma, he has also nurtured close relationships with orchestras worldwide, including the Helsinki Philharmonic, MDR Sinfonieorchester Leipzig, National Orchestra of Spain, Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and, following his Australian debut in 2006, the Sydney Sydney Orchestra. He made his MSO debut in 2020.

Opera highlights include the premiere of Jennifer Higdon’s Cold Mountain (Santa Fe Opera), Jonathan Miller’s production of La bohème (English National Opera) and Golijov’s Ainadamar (New Zealand Festival and Metropolitan Opera).

Miguel’s award-winning recordings include Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Prokofiev’s Cinderella, Lutosławski’s Concerto for Orchestra and orchestral works by Jimmy López.

Committed to unearthing under-explored South American repertoire, Miguel HarthBedoya founded and serves as Artistic Director of Caminos Del Inka, a non-profit organisation dedicated to researching, performing and preserving the rich musical legacy of South America.

Highly virtuosic, passionate and technically brilliant, German cellist Raphaela Gromes captivates audiences with her versatile and effortless playing. Born into a family of cellists, she studied at the Munich Music Institute and the University of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, followed by masterclasses David Geringas, Yo-Yo Ma, Frans Helmerson, Wolfgang Boettcher, Anner Bylsma and Wolfgang Emanuel Schmid.

As a concerto soloist, she performs the main cello repertoire alongside, and often in combination with, lesser-known works by female composers, following her research at the Frau und Werk Archive in Frankfurt. She has performed with orchestras including the HR Sinfonieorchester Frankfurt, Tonkünstlerorchester, Zurich Chamber Orchestra, Nurnberg Symphoniker and Belgian National Orchestra, collaborating with conductors such as Roberto Gonzalez-Monjas, Michael Sanderling, Pietari Inkinen, Ari Rasilainen, Aziz Shokhakimov, Anna Rakitina, Christoph Poppen and Marcus Bosch.

A Sony Classical artist, she has made six award-winning recordings, all distinguished by creative programming and an explorative spirit. Her 2024 release of the Dvořák Cello Concerto with the Ukrainian National Symphony Orchestra and Vlodomyr Sirenko marked an important collaboration that began with a performance of solidarity in Kyiv and developed immediately into a deep musical connection. She subsequently toured Europe with the orchestra in 2024. Other recordings include Femmes (2023), a double album of music by 23 outstanding female composers from across nine centuries of music history, Imagination (2021), featuring fairy-tale themed works; and Romantic Cello Concertos (2020).

These concerts mark Raphaela’s Australian debut.

Raphaela Gromes plays a Carlo Bergonzi cello from 1740, obtained for her through a private patron.

Jimmy López (born 1978)

Fiesta! – four pop dances for orchestra

Trance 1 –

Countertime

Trance 2 –

Techno

Eclecticism is an important part of my musical language. The challenge of creating musically sensible interactions out of the juxtaposition of apparently incompatible musical sources – some of which result in unexpected contrasts –fascinates me. Fiesta! draws influences from several musical sources: European academic compositional techniques, Latin-American music, Afro-Peruvian music and pop music. It utilises elaborate developmental techniques while retaining the primeval driving forces latent in popular culture.

The first and third movements of Fiesta! (Trance 1 and Trance 2) are connected in spirit and form. Both start energetically, both feature slow passages, and both lead to the following movement by means of open endings that feature soft melodies over a repeating pattern (ostinato) or repeated low note (pedal note).

The word ‘trance’ belongs to the realm of techno – electronic dance music with its use of hypnotic and repetitive rhythms. Here the purpose of repetition is to keep a steady pulse so that everybody can dance continuously while also maintaining tension. But I also use the word ‘trance’ in its original meaning – conveying the hypnotising state achieved while listening to a constantly shifting melody against a static background, much like in Hindu music.

The second and fourth movements (Countertime and Techno) maintain high

levels of energy from beginning to end. Latin rhythms play an essential part in these movements and therefore the percussion section is prominent. Countertime constantly shifts the downbeat from the strong to the weak beat of the bar – a form of syncopation. Its title derives from ‘counterpoint’, which in music theory defines the rules of interaction between two or more melodies, the goal being to produce a harmonious whole. I use the word ‘countertime’ to underline the interaction between an underlying steady pulse and the actual rhythms playing against it.

Techno uses Latin-American rhythms such as merengue. A solo for trumpet and trombone marks the beginning of a section where techno rhythms are made explicit. In a techno piece, this type of solo would be played by synthesizers, and would generally happen at the precise moment in which the constant beat of the electronic bass drum has been momentarily suspended in order to give the music a certain lightness it wouldn’t otherwise have.

Fiesta! was the first piece in which I made explicit use of elements from popular music, but it was certainly not the first time this had been done. Composers from the past, especially during the baroque period, would write suites assembling the dances that were popular in European courts. Later, composers such as J.S. Bach made these dances more sophisticated. That was part of my intention when picking up these genres. I believe they have enough potential to justify further development, but always keeping the primeval driving forces present in them.

Abridged from a note by Jimmy López © 2008

Born in Peru, Jimmy López studied at the National Conservatory of Music in Lima, and the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, before completing a doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley. His music has been performed by leading orchestras worldwide, in venues such as Carnegie Hall, the Vienna Musikverein, Amsterdam Concertgebouw, Royal Albert Hall (BBC Proms) and the Sydney Opera House. He is composer-in-residence at the San Diego Symphony and the Montreal Symphony Orchestra, previously holding the same post for three seasons at the Houston Symphony. In the 2024–25 season he was composer-curator with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Recent highlights include the premiere of his Symphony No.5, Fantastica, his oratorio Dreamers and his opera Bel Canto, and the nomination of his Aurora violin concerto for a 2022 Latin Grammy (Best Classical Contemporary Composition).

Fiesta! was commissioned by Miguel Harth-Bedoya to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Lima Philharmonic Society in 2007. It received its Australian premiere, conducted by Harth-Bedoya, in Sydney in 2013.

Joe Chindamo (born 1961)

Concerto for Orchestra

I. Preludio (Con bravura) –

II. Adagio, Intermezzo, Corale (Pastorale)

III. Scherzo (Giocoso)

IV. Interludio (Grave – Like the wind) –Cadenze – Moto Perpetuo

The concerto for orchestra medium is a relatively recent addition to the orchestral concert repertoire. Its ancestors can be found in the Baroque concerto grosso and the Classical sinfonia concertante. The modern incarnation, however, came into being in 1925, courtesy of Paul Hindemith.

In the hundred years since, as many concertos for orchestra have appeared. Notwithstanding the many worthy contributions, it is impossible to speak of this genre without acknowledging Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra. Composed in 1943, it is still the posterchild for the medium, and the work that almost single-handedly defines it.

A standard concerto traditionally features one soloist, and at its most vulgar, its nature is to provide a framework for the soloist, the superhero, in which to exhibit ‘parting of the waves’ feats against a backdrop of mortals who provide the accompaniment. Both the concerto grosso and sinfonia concertante genres are closer to the model of the concerto for

orchestra in that they feature more than one soloist or a solo group, which remains constant throughout the work. The distinguishing characteristic of a concerto for orchestra is that the spotlight shifts from one instrument to another and between the sections of the orchestra.

Born in the jazz age, at about the same time as Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, the concerto for orchestra is indeed a 20th-century idea – capturing the youthful exuberance of the age, and the celebration, rather than shunning, of excess. And through its democratic nature and elevation of the individual, it, more than any other medium, perhaps signposts Andy Warhol’s claim that we all shall have our 15 minutes of fame.

The remarkable advancements in technology, and the exponential speed with which they occurred, were reflected in the unprecedented virtuosity of the players, since the concerto for orchestra was, and is, as much about them as it is about the music.

Finally, the concerto for orchestra affords the composer the luxury of writing many works under the rubric of one. To paraphrase Luigi Barzini, who defined Italy as a mosaic of families rather than a country, the medium is in essence a mosaic of genres, whose collective nature can suddenly transform itself from an intimate chamber work into a full symphonic explosion.

These are the formal and expressive qualities I have set out to capture and exploit in my own contribution to the genre.

Dr Joe Chindamo OAM © 2025

About the composer

Having forged an international career as a brilliant jazz pianist, Joe Chindamo OAM has now emerged as a coveted new voice in contemporary classical composition, with commissions from the Australian

String Quartet, ACO, Camerata and the Melbourne, Tasmanian and Queensland symphony orchestras. In 2016 he collaborated with Steve Vizard to create Vigil for the Adelaide Cabaret Festival. Recent premieres include Ligeia (ASO and trombonist Colin Prichard), Principia Clarinettica (Melbourne Chamber Orchestra and MSO Associate Principal Clarinet Philip Arkinstall) and Concerto for Drums and Orchestra (MSO and David Jones). His Concerto for Orchestra was commissioned by the TSO in 2021.

Antonín Dvořák (1841 – 1904)

Cello Concerto in B minor, B. 191 (Op. 104)

I. Allegro

II. Adagio ma non troppo

III. Allegro moderato

Raphaela Gromes cello

Brahms was impressed. ‘If only I’d known,’ he said, ‘that one could write a cello concerto like that, I’d have written one long ago!’ And he wasn’t just being polite. Brahms had recognised Dvořák’s talents early on, ensuring the young composer received from the Imperial Government in Vienna the Austrian State Stipendium, an annual grant, for five years, and persuading his own publisher, Simrock of Berlin, to publish Dvořák’s music.

But Brahms’s admiration aside, the composition of what Dvořák scholar John Clapham has called simply ‘the greatest of all cello concertos’ was no easy matter. In fact, it was his second attempt at the medium – the first, in A major, was composed in 1865, but appears only to have been written out in a cello and piano score. This work was rediscovered by the German composer Günter Raphael in 1929. He made an orchestral version at the time, as did Jarmil Burghauser in 1977, but the versions are significantly different. That Dvořák left the work unorchestrated

suggests that he was dissatisfied with this first effort. Despite the urgings of his friend, the cellist Hanuš Wihan, Dvořák thought no more about writing such a piece until many years later.

In 1894 Dvořák was living in New York, having accepted the invitation of Jeannette Meyer Thurber to head the National Conservatory of Music that she had founded there in 1885. In March 1894, Dvořák attended a performance by Victor Herbert of his Second Cello Concerto. The Irish-born American composer and cellist is now best remembered for shows like Naughty Marietta and Babes in Toyland, but his concerto, modelled on SaintSaëns’ First, made a huge impact on Dvořák, who re-examined the idea of such a work for Wihan. The work was sketched between 8 November 1894 and New Year’s Day, and Dvořák completed the full score early in February.

Much to Dvořák’s annoyance, the first performance of the concerto was not given by its dedicatee, Wihan. The London Philharmonic Society, who premiered it at the Queen’s Hall in March 1896, mistakenly believed Wihan to be unavailable, and engaged Leo Stern. Despite Dvořák’s embarrassment, Stern must have delivered the goods, as Dvořák engaged him for the subsequent New York, Prague and Vienna premieres of the work. Wihan did, however, perform the work often, and insisted on making some ‘improvements’ to Dvořák’s score so that the cello part would be more virtuosic. Wihan also insisted on interpolating a cadenza in the third movement, which the composer vehemently opposed. For some reason Simrock was on the point of publishing the work with Wihan’s amendments, and only a stiff letter from Dvořák persuaded the publisher to leave out the cadenza. Brahms, incidentally, had by this time taken on the job of correcting the proofs of Dvořák’s music before publication, to save the time of sending them to and from the United States.

Despite being an ‘American’ work, the concerto is much more a reflection of Dvořák’s nostalgia for his native Bohemia, and perhaps for the composer’s father who died in 1894. As scholar Robert Battey has noted: ‘Two characteristic Bohemian traits can be found throughout the work, namely pentatonic [‘black note’] scales and an aaB phrase pattern, where a melody begins with a repeated phrase followed by a two-bar “answer”.’ The work is full of some of Dvořák’s most inspired moments, such as the heroic first theme in the first movement, and the complementary melody for horn which adds immeasurably to its Romantic ambience.

The Bohemian connection became even stronger and more personal when Dvořák, working on the piece in December 1894, heard that his sister-in-law Josefina (with whom he had been in love during their youth) was seriously, perhaps mortally, ill. Dvořák was sketching the slow movement at the time. The outer sections of this movement are calm and serene, but Dvořák expresses his distress in an impassioned gesture that ushers in an emotionally unstable central section in G minor, based on his song ‘Kéž duch můj sám’ (Leave me alone), which was one of Josefina’s favourites. Josefina died in the spring of 1895, and Dvořák, by this time back in Bohemia, made significant alterations to the concluding coda of the third movement, adding some 60 bars of music. The movement begins almost ominously with contrasting lyrical writing for the soloist. Dvořák’s additions to the movement, and his determination not to diffuse its emotional power with a cadenza, allowed him, as Battey notes, to revisit ‘not only the first movement’s main theme, but also a hidden reference to Josefina’s song in the slow movement. Thus, the concerto becomes something of a shrine, or memorial.’

Gordon Kerry Symphony Australia © 2004

QUICK FIX AT HALF SIX

Monday 21 July at 6:30pm

Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne

Artists

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Miguel Harth-Bedoya conductor

Raphaela Gromes cello

Dvořák Cello Concerto in B minor [40’]

Introduced by Miguel Harth‑Bedoya

The artist biographies and program note for this performance can be found on pages 26 and 31.

Tonight’s onstage introduction by Miguel Harth-Bedoya will be Auslan interpreted.

Running time: 1 hour. Timings listed are approximate.

Quick Fix at Half Six is supported by City of Melbourne. Auslan interpreted performances are supported by the Australian Government Department of Social Services.

Ryman Healthcare Spring Gala with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra conducted by Jaime Martín

Thursday 7 August at 7:30 pm

Saturday 9 August at 7:30 pm

Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne

Artists

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Shiyeon Sung conductor

Simone Lamsma violin

Program

Klearhos Murphy * The Ascent ** [10’]

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto [34’]

Brahms Symphony No. 2 [46’]

* Cybec Young Composer in Residence ** World premiere of an MSO commission

Running time: 1 hour 45 minutes, including interval. Timings listed are approximate.

Shiyeon Sung is a trailblazer of her profession – the first female conductor from South Korea to make the leap to the podiums of internationally renowned orchestras, including the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Los Angeles Philharmonic and Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. In 2023 she was appointed Principal Guest Conductor of the Auckland Philharmonia.

Born in Busan, South Korea, Shiyeon Sung won various prizes as a pianist in youth competitions. She studied orchestral conducting with Rolf Reuter at the Hanns Eisler School of Music in Berlin (2001–2006) before continuing her education with advanced conducting studies with Jorma Panula at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm.

When she was appointed assistant conductor at the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 2007, her reputation as one of the most exciting emerging talents on the international music circuit was already secure. Shortly before, she had won both the International Conductors’ Competition Sir Georg Solti and the Gustav Mahler Conducting Competition. In 2009, the Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra established for her an associate conductor position, which she held until 2013. Now resident in Berlin, she remains a popular guest in her home country.

Shiyeon Sung made her Australian debut conducting the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in 2016, and has since conducted the Queensland, Adelaide and Tasmanian symphony orchestras. This year she conducts the MSO for the first time.

Dutch violinist Simone Lamsma is respected by critics, peers and audiences as one of today’s most striking musical personalities. She has been the guest of many of the world’s leading orchestras, from New York, Chicago and Los Angeles to London, Berlin, Paris, Vienna and Amsterdam, collaborating with such conductors as Jaap van Zweden, Antonio Pappano, Paavo Järvi, Gianandrea Noseda, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Louis Langrée, Gustavo Gimeno, Karina Canellakis, Stanislav Kochanovsky, Marc Albrecht, Stéphane Denève, Vassily Petrenko, Domingo Hindoyan, François-Xavier Roth, Edward Gardner, Kent Nagano and James Gaffigan. She made her Australian debut in 2016 and this year performs with the MSO for the first time.

Her most recent recordings include Pärt über Bach with the Amsterdam Sinfonietta and Candida Thompson, released last year, and the acclaimed Rautavaara: Lost Landscapes (2022), with the Malmö Symphony Orchestra and Robert Trevino. Other recordings include Shostakovich and Gubaidulina with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic under James Gaffigan and Reinbert de Leeuw, and a recital album with pianist Robert Kulek.

A graduate of the Yehudi Menuhin School and the Royal Academy of Music in London, in 2019, Simone was made a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music, an honour limited to 300 former Academy students, and awarded to those musicians who have distinguished themselves within the profession.

Klearhos Murphy (born 1998)

The Ascent

The Ascent was inspired by St Nikítas Stethátos’ 11th-century work On Spiritual Knowledge. In it, he epitomises the tripartite spiritual life as articulated in the Orthodox Christian tradition (purification, illumination and deification). More than merely prescribing a method for moral improvement, he describes the stages of the whole person being radically transformed through grace, beginning with ascetic struggle, moving to an illuminating knowledge of the created order, and ultimately culminating in the telos of humanity, namely, oneness with God (θέωσις).

Rather than setting the music directly to the text, this composition meditates upon the three key goals – each a spiritual summit of its respective stage – quoted below from St Nikítas’ work in both Greek and English:

I. Purification (Κάθαρσις)

To be forged in the fire of ascetic struggle

This section evokes the person’s struggle against passion through discipline, compunction and prayer.

II. Illumination (Φωτισμός)

To be elucidated of the nature of created things by the Logos of Wisdom

Here the music turns contemplative, gesturing toward interior stillness and spiritual insight.

III. Deification (Θέωσις)

τὸ

To be filled with ineffable wisdom through union with the Holy Spirit

The final part aspires to sonically express the joy of divine union – where human and divine meet in simplicity, harmony, and mystery.

Klearhos Murphy © 2025

About the composer

Greek-Australian composer Klearhos Murphy is currently studying for a master’s degree at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music. His research focuses on the capacity of Eastern

Orthodox spirituality and Greek folk music to inform the creative process.

In addition to his role as the MSO’s Cybec Young Composer in Residence, this year Murphy has been collaborating with Ensemble Offspring and the Australian Hellenic Choir. He has also worked with the West Australian, Perth and WAAPA symphony orchestras, Vienna Pops Orchestra and the Willoughby Symphony Orchestra, and 2024 saw world premieres at the Sydney Opera House through Omega Ensemble’s CoLAB: Composer Accelerator Program and Ensemble Offspring’s Hatched Academy.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893)

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35

I. Allegro moderato – Moderato assai

II. Canzonetta (Andante)

III. Finale (Allegro vivacissimo)

Simone Lamsma violin

It was the winter of 1877, and Tchaikovsky was in love. He wrote to his brother Modest about the ‘unimaginable force’ of the passion that had developed; its object was a young violinist and student at the Moscow Conservatorium, Josef Kotek. Tchaikovsky had known ‘this wonderful youth’ for about six years. In 1876 Kotek had also acted as a go-between for Tchaikovsky and his new patron, Nadezhda von Meck, who eschewed any face to face contact with the composer. Kotek was a devoted and affectionate but platonic friend to Tchaikovsky, but predictably enough, soon became besotted with a fellow (female) student.

The composer’s ardour cooled quickly, and within three weeks of discovering Kotek’s new relationship, Tchaikovsky had made his fateful proposal to Antonina Milyukova, a former Conservatorium student who had fallen in love with him. They married two months later, and as the

depth of their cultural and personal differences quickly became clear, Tchaikovsky left his wife two months after that. Milyukova, incidentally, was not the deranged harpy that histories (or myth) have made of her.

Kotek and Tchaikovsky remained friends, however, and the Violin Concerto seems to have grown out of a promise that the composer made to write a piece for one of Kotek’s upcoming concerts. ‘We spoke,’ Tchaikovsky told his brother, ‘of the piece he ordered me to write... He repeated over and over that he would get angry if I didn’t write this piece.’ While Kotek was not, ultimately, the dedicatee or first performer of the work, he was of enormous help to Tchaikovsky in playing through sections of the piece as the composer finished them.

After leaving his wife, Tchaikovsky, accompanied by one or other of his brothers (and at one point Kotek himself), travelled extensively in western Europe. Tchaikovsky worked on the Violin Concerto in Switzerland in early 1878, not long after completing the Fourth Symphony and the opera Eugene Onegin. Commentators are generally agreed that both of those works

reflect Tchaikovsky’s emotional reactions to the traumatic events of his marriage, though the composer himself was careful, in a letter to Mme von Meck, to point out that one could only depict such states in retrospect. In any event, it seems likely that, apart from honouring a promise to Kotek, Tchaikovsky found the conventions of the violin concerto offered a way of writing a large-scale work without the personal investment of the opera and symphony.

Like the great concertos of Beethoven and Brahms, Tchaikovsky’s is in D major and in three substantial movements. The first develops two characteristic themes within a tracery of brilliant virtuoso writing for the violin, and like Mendelssohn in his concerto, Tchaikovsky places the solo cadenza before the recapitulation of the opening material. As in the slow movement of the Fourth Symphony, the central Canzonetta works its magic by the deceptively simple repetition of its material. The work concludes with a bravura, ‘Slavic’ Finale which is interrupted only by a motif for solo oboe which for one writer recalls a moment in the ‘Letter Scene’ from Onegin (which itself parallels the relationship between Tchaikovsky and Antonina).

The work was initially dedicated to the virtuoso Leopold Auer, who thought it far too difficult and refused to play it. In 1881 Adolf Brodsky gave the premiere in Vienna, where that city’s most feared critic, Eduard Hanslick, tore the piece to shreds: ‘The violin is no longer played; it is pulled, torn, drubbed...We see plainly the savage vulgar faces, we hear curses, we smell vodka...’

Hanslick, like many a music critic, made a bad call; Tchaikovsky had written one of the best-loved works of the repertoire.

Gordon Kerry © 2003

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73

I. Allegro non troppo

II. Adagio non troppo

III. Allegretto grazioso (Quasi andantino) – Presto ma non assai

IV. Allegro con spirito

Defending Brahms against a common charge, American composer Charles Ives observed that:

to think hard and deeply and say what is thought, regardless of consequences, may produce a first impression either of great translucence or of great muddiness, but in the latter there may be hidden possibilities… The mud may be a form of sincerity.

In fact, Brahms’s music sounds ‘muddy’ only where we move too far from the original disposition of the orchestra he used. Brahms wrote for a modest band of two of each wind and brass instrument (using the latter sparingly), though with four horns and a matching compliment of strings. He uses forceful orchestral effects to be sure, but if ever proof were needed that Brahms’s orchestration could be of the most refined, we need go no further than the Second Symphony.

Brahms took a long time to produce his First Symphony, and to have it described as ‘the Tenth’ (as conductor Hans von Bülow called it, alluding to Beethoven) might well have been a recipe for crippling stage fright; nonetheless the Second followed almost immediately. The relationship between the two offered another irresistible comparison with Beethoven, one which the great British writer Donald Tovey and others have seized upon: in the case of Beethoven’s Fifth and Sixth Symphonies and Brahms’s First and Second we have pairs of works where the first is a strenuous, dramatic, maybe even tragic, work in the key of C minor whose trajectory traces a metaphorical journey from darkness to light, whereas the second is a contrastingly serene, happy, Apollonian work in a major key with certain elements that we might describe as pastoral. Brahms sneered at such suggestions (which is not to say they have no merit), and it is true that his orchestration in this work relies more than usually heavily on wind solos – particularly the bucolic sounds of oboe and horn, and that in the third movement, in particular, there is that reliance on vernacular music which reminds us of the peasants’ merry-making in Beethoven’s Sixth.

But as Brahms well knew, ‘et in Arcadia ego’: he joked to his publisher that this was the saddest piece he had ever written, and it is significant that the symphony begins, and ends, with the sound of trombones, instruments only dragged out of the church by Mozart (in Don Giovanni) and into the concert hall by Beethoven.

The scoring at the start is, naturally, ‘dark’ thanks to the trombones, creating a slightly ominous atmosphere that is swept away by the more high-spirited material, with its hint of the famous ‘Brahms lullaby’ stated first by the lower strings. The overall vector of the movement is upwards

to the high wind scoring at its centre, which gives way to some intensely Brahmsian counterpoint, two-againstthree rhythmic figures and veiled warnings from the trombones. The movement ends introspectively, paving the way for one of Brahms’s most beautiful adagios. The lovely, endless opening melody is stated in the low strings and answered by simple falling scale passages from the higher instruments. (Paradoxically, in this movement there are moments that sound like Brahms’s rival Bruckner.) But again, there is no serenity without the possibility of conflict, and the pastoral calm is more than once challenged by emotionally charged outbursts, particularly as the movement reaches its final moments.

Here as elsewhere Brahms replaces the traditional scherzo with a lighter dancemovement. The Allegretto grazioso consists of three statements of a genial dance with two faster, possibly Slavic or Hungarian-inspired, episodes.

The finale returns us to a purely Arcadian world, with the memory of the darker implications that have surfaced earlier, and an electrifying conclusion. It is formally straightforward, notionally a sonata design but with no especially rigorous development. Brahms balances the impulse to Lisztian Romantic rhapsody with a strong sense of formal design. The Second Symphony is conceived on a large scale, within classical norms; but Brahms never allows an idea to stand, or to be simplistically repeated. His technique of developing variation made him an unlikely hero to Schoenberg, and therefore a kind of grandfather to modern music. But Brahms doesn’t just transform his themes: his treatment of forms transforms them. As such it is one solution to the problem of late Romanticism.

Gordon Kerry © 2015

MSO Patron

Her Excellency Professor, the Honourable

Margaret Gardner AC, Governor of Victoria

Honorary Appointments

Chair Emeritus

Dr David Li AM

Life Members

John Gandel AC and Pauline Gandel AC

Jean Hadges

Sir Elton John CBE

Lady Primrose Potter AC

Jeanne Pratt AC

Lady Marigold Southey AC

Michael Ullmer AO and Jenny Ullmer

MSO Ambassador

Geoffrey Rush AC

Artist Chair Benefactors

Chief Conductor Chair Jaime Martín

Supported by the Besen Family Foundation in memory of Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AC

Cybec Assistant Conductor Chair

Leonard Weiss CF

Cybec Foundation

MSO Now & Forever Fund: International Engagement Gandel Foundation

Artist Development Programs –

Cybec Foundation

Cybec Young Composer in Residence

Cybec First Nations Composer in Residence

Cybec 21st Century Australian Composers Program

East Meets West

The Li Family Trust

Community and Public Programs

Australian Government Department of Social Services, AWM Electrical, City of Melbourne, Hansen Little Foundation, Dr Mary-Jane H Gething AO

Student Subsidy Program

Anonymous

Jams in Schools

Melbourne Airport, Department of Education, Victoria – through the Strategic Partnerships Program, AWM Electrical, Jean Hadges, Hume City Council, Marian and EH Flack Trust

MSO Regional Touring

AWM Electrical, Freemasons Foundation

Victoria, Robert Salzer Foundation, Sir Andrew and Lady Fairley Foundation, Rural City of Wangaratta

Sidney Myer Free Concerts

Sidney Myer MSO Trust Fund and the University of Melbourne, City of Melbourne Event Partnerships Program

Instrument Fund

Tim and Lyn Edward, Catherine and Fred Gerardson, Pauline and David Lawton, Joe White Bequest

Platinum Patrons ($100,000+)

AWM Electrical

Besen Family Foundation

Dr Mary-Jane H Gething AO ♡

The Gross Foundation ♡

David Li AM and Angela Li

Lady Primrose Potter AC Anonymous (1)

Virtuoso Patrons ($50,000+)

The Aranday Foundation

Tim and Lyn Edward ♡ ♫

Dr Harry Imber ♡

Margaret Jackson AC ♡

Lady Marigold Southey AC

The Yulgilbar Foundation Anonymous (1)

Impresario Patrons ($20,000+)

Christine and Mark Armour

Shane Buggle and Rosie Callanan ♡

Debbie Dadon AM

Catherine and Fred Gerardson

The Hogan Family Foundation

Pauline and David Lawton ♡

Maestro Jaime Martín

Paul Noonan

Elizabeth Proust AO and Brian Lawrence

Sage Foundation ☼

The Sun Foundation

Maestro Patrons ($10,000+)

John and Lorraine Bates ☼

Margaret Billson and the late Ted Billson ♡

John Calvert-Jones AM and Janet Calvert-Jones AO

Krystyna Campbell-Pretty AM

Jolene S Coultas ♡

The Cuming Bequest

Miss Ann Darby in memory of Leslie J Darby

Anthony and Marina Darling

Mary Davidson and the late Frederick Davidson AM

Andrew Dudgeon AM ♡

Andrew and Theresa Dyer ♡

Val Dyke

Kim and Robert Gearon

The Glenholme Foundation

Charles & Cornelia Goode Foundation

Cecilie Hall and the late Hon Michael Watt KC ♡ ♫

Hanlon Foundation ♡

Michael Heine

David Horowicz ♡

Peter T Kempen AM ♡

Owen and Georgia Kerr

Peter Lovell

Dr Ian Manning

Janet Matton AM & Robin Rowe

Rosemary and the late Douglas Meagher ♡

Dr Justin O’Day and Sally O’Day

Ian and Jeannie Paterson

Hieu Pham and Graeme Campbell

Liliane Rusek and Alexander Ushakoff

Quin and Lina Scalzo

Glenn Sedgwick ♡

Cathy and John Simpson AM

David Smorgon OAM and Kathie Smorgon

Straight Bat Private Equity

Athalie Williams and Tim Danielson

Lyn Williams AC

The Wingate Group

Anonymous (2)

($5,000+)

Arnold Bloch Leibler

Mary Armour

Philip Bacon AO

Alexandra Baker

Barbara Bell in memory of Elsa Bell

Julia and Jim Breen

Nigel and Sheena Broughton

Jannie Brown

Chasam Foundation

Janet Chauvel and the late Dr Richard Chauvel

John Coppock OAM and Lyn Coppock

David and Kathy Danziger

Carol des Cognets

George and Laila Embelton

Equity Trustees ☼

Bill Fleming

♡ Chair Sponsor | 2025 Europe Tour Circle | ☼ First Nations Circle ♫ Commissioning Circle | ∞ Future MSO

John and Diana Frew ♡

Carrillo Gantner AC and Ziyin Gantner

Geelong Friends of the MSO

The Glavas Family

Louise Gourlay AM

Dr Rhyl Wade and Dr Clem Gruen ♡

Louis J Hamon OAM

Dr Keith Higgins and Dr Jane Joshi

Jo Horgan AM and Peter Wetenhall

Geoff and Denise Illing

Dr Alastair Jackson AM

John Jones

Konfir Kabo

Merv Keehn and Sue Harlow

Suzanne Kirkham

Liza Lim AM ♫

Lucas Family Foundation

Morris and Helen Margolis ♡

Allan and Evelyn McLaren

Dr Isabel McLean

Gary McPherson ♡

The Mercer Family Foundation

Myer Family Foundation

Suzie and Edgar Myer

Rupert Myer AO and Annabel Myer

Anne Neil in memory of Murray A Neil ♡

Patricia Nilsson ♡

Sophie Oh

Phillip Prendergast

Ralph and Ruth Renard

Jan and Keith Richards

Dr Rosemary Ayton and Professor Sam Ricketson AM

Gillian Ruan

Kate and Stephen Shelmerdine Foundation

Helen Silver AO and Harrison Young

Brian Snape AM

Dr Michael Soon

Gai and David Taylor

P & E Turner

The Upotipotpon Foundation

Mary Waldron

Janet Whiting AM and Phil Lukies

Kee Wong and Wai Tang

Peter Yunghanns

Igor Zambelli OAM

Shirley and Jeffrey Zajac

Anonymous (3)

Associate Patrons ($2,500+)