May–June 2025 Program

An Evening of Fairy Tales

A Reflection in Time

A Reflection in Time

In the first project of its kind in Australia, the MSO has developed a musical Acknowledgement of Country with music composed by Yorta Yorta composer Deborah Cheetham Fraillon ao, featuring Indigenous languages from across Victoria.

Generously supported by Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and the Commonwealth Government through the Australian National Commission for UNESCO, the MSO is working in partnership with Short Black Opera and Indigenous language custodians who are generously sharing their cultural knowledge.

The Acknowledgement of Country allows us to pay our respects to the traditional owners of the land on which we perform in the language of that country and in the orchestral language of music.

As a Yorta Yorta/Yuin composer, the responsibility I carry to assist the MSO in delivering a respectful acknowledgement of country is a privilege which I take very seriously. I have a duty of care to my ancestors and to the ancestors on whose land the MSO works and performs. As the MSO continues to grow its knowledge and understanding of what it means to truly honour the First People of this land, the musical acknowledgement of country will serve to bring those on stage and those in the audience together in a moment of recognition as we celebrate the longest continuing cultures in the world.

—Deborah Cheetham Fraillon ao

Our musical Acknowledgement of Country, Long Time Living Here by Deborah Cheetham Fraillon ao, is performed at MSO concerts.

The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra is Australia’s preeminent orchestra, dedicated to creating meaningful experiences that transcend borders and connect communities. Through the shared language of music, the MSO delivers performances of the highest standard, enriching lives and inspiring audiences across the globe.

Woven into the cultural fabric of Victoria and with a history spanning more than a century, the MSO reaches five million people annually through performances, TV, radio and online broadcasts, as well as critically acclaimed recordings from its newly established recording label.

In 2025, Jaime Martín continues to lead the Orchestra as Chief Conductor and Artistic Advisor. Maestro Martín leads an Artistic Family that includes Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor – Learning and Engagement Benjamin Northey, Cybec Assistant Conductor Leonard Weiss, MSO Chorus Director Warren Trevelyan-Jones, Composer in Residence Liza Lim am, Artist in Residence James Ehnes, First Nations Creative Chair Deborah Cheetham Fraillon ao, Cybec Young Composer in Residence Klearhos Murphy, Cybec First Nations Composer in Residence James Henry, Artist in Residence, Learning & Engagement Karen Kyriakou, Young Artist in Association Christian Li, and Artistic Ambassadors Tan Dun, Lu Siqing and Xian Zhang.

The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra respectfully acknowledges the people of the Eastern Kulin Nations, on whose un‑ceded lands we honour the continuation of the oldest music practice in the world.

Tair Khisambeev

Acting Associate Concertmaster

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio*

Anne-Marie Johnson

Acting Assistant Concertmaster

David Horowicz*

Peter Edwards

Assistant Principal

Sarah Curro

Dr Harry Imber *

Peter Fellin

Deborah Goodall

Karla Hanna

Lorraine Hook

Kirstin Kenny

Eleanor Mancini

Anne Neil*

Mark Mogilevski

Michelle Ruffolo

Anna Skálová

Kathryn Taylor

Matthew Tomkins

Principal

The Gross Foundation*

Jos Jonker

Associate Principal

Monica Curro

Assistant Principal

Dr Mary Jane Gething AO*

Mary Allison

Isin Cakmakçioglu

Emily Beauchamp

Tiffany Cheng

Glenn Sedgwick*

Freya Franzen

Cong Gu

Andrew Hall

Robert Macindoe

Isy Wasserman

Philippa West

Andrew Dudgeon AM*

Patrick Wong

Cecilie Hall*

Roger Young

Shane Buggle and Rosie Callanan*

Violas

Christopher Moore Principal

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio*

Lauren Brigden

Katharine Brockman

Anthony Chataway

Peter T Kempen AM*

William Clark

Morris and Helen Margolis*

Aidan Filshie

Gabrielle Halloran

Jenny Khafagi

Margaret Billson and the late Ted Billson*

Fiona Sargeant

David Berlin Principal

Rachael Tobin

Associate Principal

Elina Faskhi

Assistant Principal

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio*

Rohan de Korte

Andrew Dudgeon AM*

Sarah Morse

Rebecca Proietto

Peter T Kempen AM*

Angela Sargeant

Caleb Wong

Michelle Wood

Double Basses

Jonathon Coco Principal

Stephen Newton

Acting Associate Principal

Rohan Dasika

Acting Assistant Principal

Benjamin Hanlon

Aurora Henrich

Suzanne Lee

Flutes

Prudence Davis

Principal

Jean Hadges*

Wendy Clarke

Associate Principal

Sarah Beggs

Piccolo

Andrew Macleod

Principal

Oboes

Johannes Grosso

Principal

Michael Pisani

Acting Associate Principal

Ann Blackburn

Margaret Billson and the late Ted Billson*

Clarinets

David Thomas

Principal

Philip Arkinstall

Associate Principal

Craig Hill

Rosemary and the late Douglas Meagher *

Bass Clarinet

Jonathan Craven Principal

Jack Schiller

Principal

Dr Harry Imber *

Elise Millman

Associate Principal

Natasha Thomas

Patricia Nilsson*

Contrabassoon

Brock Imison

Principal

Horns

Nicolas Fleury

Principal

Margaret Jackson AC*

Peter Luff

Acting Associate Principal

Saul Lewis

Principal Third

The late Hon Michael Watt KC and Cecilie Hall*

Abbey Edlin

The Hanlon Foundation*

Josiah Kop

Rachel Shaw

Gary McPherson*

Trumpets

Owen Morris Principal

Shane Hooton

Associate Principal

Glenn Sedgwick*

Rosie Turner

Dr John and Diana Frew*

Learn more about our musicians on the MSO website. * Position supported by

Trombones

José Milton Vieira

Principal

Richard Shirley

Bass Trombone

Michael Szabo

Principal

Tuba

Timothy Buzbee

Principal

Timpani

Matthew Thomas Principal

Percussion

Shaun Trubiano

Principal

John Arcaro

Tim and Lyn Edward*

Robert Cossom

Drs Rhyl Wade and Clem Gruen*

Harp

Yinuo Mu

Principal

Pauline and David Lawton*

What is a symphony orchestra? An orchestra is not just the configuration you see on stage at a concert, it’s the sum of the sounds it can make: it’s a symphonia, a ‘sounding together’ of musicians and their instruments.

While most of our wonderful string, woodwind and brass musicians own their instruments, many of the large percussion instruments you see on stage are owned and maintained by the MSO.

These instruments, however, are taking a beating – literally – week in, week out, and to maintain the highest quality of musical expression, we need to update our instrumental resources regularly.

Thanks to the amazing generosity of Tim and Lyn Edward, Catherine and Fred Gerardson, Pauline and David Lawton, the Joe White Bequest and other wonderful Instrument Fund donors, we have recently been able to purchase a set of four timpani, two xylophones, a glockenspiel, a vibraphone and a glistening set of tubular bells.

These transformative gifts have completely renewed the sonic resources of the beating heart of the MSO, our percussion section!

We’re also deeply grateful to Pauline and David Lawton, whose generous gift enabled us to purchase a beautiful new handmade concert harp from Lyon & Healy Harps in Chicago.

the new instruments in concert

The new tubular bells play a prominent part in An Evening of Fairy Tales (15–17 May) – listen for their chimes as the clock ticks inexorably towards midnight in Prokofiev’s Cinderella.

Together with the new glockenspiel, the bells will also feature in Ravel’s famous orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, to be performed at the Ryman Healthcare Winter Gala and as part of our Mornings series (27–28 June).

And keep an eye out for our dazzling and intricate new harp – the only one of its kind in Australia – especially in Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty music (15–17 May) and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade (29, 31 May and 2 June).

Adapted from a blog post by MSO Donor Liaison Keith Clancy.

To learn more about the MSO’s Instrument Fund priorities or to join this generous community, please contact Keith Clancy at philanthropy@mso.com.au

The MSO creates music that matters for all Victorians, whoever or wherever you are.

In addition to attending this concert, your generous gift this tax time will help ensure our concerts and programs are more accessible, welcoming, and inclusive than ever.

A gift of any size is appreciated. Thank you. mso.com.au/give | (03) 8646 1551 All gifts over $2 are fully tax-deductible

Give today

Artists

Thursday 15 and Saturday 17 May at 7:30pm Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne

Friday 16 May at 7:30pm Costa Hall, Geelong

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Alpesh Chauhan conductor

Program

Humperdinck Hansel and Gretel: Prelude [9’]

Prokofiev Cinderella: At the Ball (Highlights from Act II) [13’]

Interval [20’]

Tchaikovsky Dramatic highlights from Sleeping Beauty [64’]

CONCERT EVENTS

Pre-concert talk: Learn more about the performance with conductor and educator

Ingrid Martin at 6:45pm in the Stalls Foyer on Level 2 at Hamer Hall (15, 17 May) and Costa Hall (16 May).

For a list of musicians performing in this concert, please visit mso.com.au/musicians

Running time: 2 hours including interval. Timings listed are approximate.

MSO’s Geelong performance is supported by AWM Electrical, Freemasons Foundation Victoria, the Robert Salzer Foundation and Geelong Friends of the MSO.

Alpesh Chauhan obe is renowned for his interpretation of late Romantic and 20thcentury repertoire, and is a keen exponent of contemporary music. He is Principal Guest Conductor of Düsseldorfer Symphoniker and Music Director of Birmingham Opera Company, and works regularly with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. He was previously Principal Conductor of the Filarmonica Arturo Toscanini in Parma (2017–20) and also enjoys a longstanding relationship with BBC Scottish Symphony: he was Associate Conductor (2020–23), appeared with them at the BBC Proms in 2022, and is currently recording a Tchaikovsky cycle, with the first two albums released to acclaim in 2023 and 2024.

Alpesh has also conducted the Hallé Orchestra, Philharmonia Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, Oslo Philharmonic, Philzuid, Orchestre National de Belgique and Los Angeles Philharmonic, as well as the Malmö, Antwerp, Stavanger, Detroit, Vancouver and Toronto symphony orchestras, and he regularly collaborates with soloists such as Stephen Hough, Hilary Hahn, Johannes Moser and Benjamin Grosvenor. In Australia he has conducted the Adelaide and West Australian symphony orchestras in addition to the MSO.

Born in Birmingham, Alpesh studied cello and then conducting at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, and was conferred an Honorary Fellow of the RNCM in 2024. He received an OBE for Services to the Arts in 2022.

ENGELBERT HUMPERDINCK (1854–1921)

Hansel and Gretel: Prelude

SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891–1953)

Cinderella

Act II (At the Ball): Promenade

Cinderella’s Dance

The Prince’s Dance Duet for the Prince and Cinderella Waltz–Coda –Midnight

PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840–1893)

Sleeping Beauty

Prologue (Aurora’s Christening): Introduction

Finale

Act I (The Spell): Scene

Waltz

Rose Adagio: Adagio for Aurora –Dance of the maids of honour –Dance of the pages

Finale

Act II (The Awakening): Symphonic interlude (Sleep) and Scene

Finale

Act III (The Wedding): March

Pas de quatre (Jewel Fairies): Introduction

Finale and Apotheosis

FACING: Lana Jones (Aurora), Lynette Wills (Carabosse) and artists of The Australian Ballet in the dramatic conclusion to Act II of David McAllister’s The Sleeping Beauty

PHOTO © JEFF BUSBY, COURTESY THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET

prince. Cinderella appears hesitant at first, with a solo that, for all its brilliance, can’t decide whether it’s in duple or triple time. The Prince, by contrast, dances with an assured brio. When they dance together, an elegant slow waltz for the cellos blossoms into opulent, impassioned music. The waltz proper that follows hastens the scene to its climax, and we’re abandoned with Cinderella on the palace steps at midnight, Prokofiev’s nightmarish chiming clocks dragging us back into the real world.

As a 15 year old, Prokofiev named Tchaikovsky as one of his favourite composers, inspired in part by Sleeping Beauty. Tchaikovsky himself knew the ballet was one of his best works but the initial reception in 1889 had been lukewarm. It was dismissed as ‘too symphonic’ even as his Fourth Symphony had been deemed ‘too balletic’. Yet the balletic symphonies and symphonic ballets share many qualities: unsurpassed melodic invention, careful treatment of key relations, and a sense of drama and irresistible movement. It’s no surprise the Sleeping Beauty music is as remarkable on the concert platform as it is in the theatre.

As with Cinderella, Alpesh Chauhan has devised his own Sleeping Beauty suite, focusing on the ballet’s narrative rather than a parade of hits. We hear key scenes from each act in a selection that highlights Tchaikovsky’s theatrical instincts and brings the symphonic character of the music to the fore.

In the PROLOGUE, Tchaikovsky drops us into the thick of the action, playing two contrasting themes against each other: fierce Carabosse, and the lyrical but assured Lilac Fairy. The tension comes to a head when Carabosse gatecrashes the christening and curses the royal baby, only for the Lilac Fairy (harp and oboe) to temper that curse: not eternal sleep, but merely a hundred years.

ACT I brings two well-known numbers: the Garland Waltz and the Rose Adagio –a tour de force for the ballerina, who must demonstrate perfect poise, balancing en pointe as she accepts roses from four noble suitors, while Tchaikovsky’s impassioned music swirls around her. These are framed by two extended scenes that advance the narrative. The first shows a kingdom in which spindles have been banned and some old women caught spinning are threatened with prison before the king arrives to bestow mercy. Lurking underneath the general high spirits – it’s Aurora’s birthday – is Carabosse’s curse theme.

Nineteenth-century ballet composers were expected to conform to strict instructions concerning mood, tempo, metre and duration. For the Act I Finale, choreographer Marius Petipa specified:

Suddenly Aurora notices an old woman who beats her knitting needles – a 2/4 bar. Gradually she changes to a very melodious waltz…, but then suddenly a rest. Aurora pricks her finger. Screams, pain. Blood streams, give eight bars in 4/4 – wide. She begins her dance –dizziness… Complete horror – this is not a dance any longer. It is a frenzy. As if bitten by a tarantula she keeps turning and falls unexpectedly, out of breath. This must last from 24 to 32 bars.

And this, give or take a few bars, is what Tchaikovsky supplied.

ACT II presents Aurora’s awakening. In an extended symphonic interlude (Sleep), Tchaikovsky revisits and transforms the themes of the introduction: Carabosse’s fierce chords become sustained woodwind harmonies; the Lilac Fairy’s theme is given to a muted trumpet. The dreamy atmosphere dissolves in the concluding Scene as the Prince runs towards the sleeping Aurora and breaks the spell with a kiss. (Or is it the crash of the tam-tam that wakes her?) The palace comes to life again in the triumphant and vibrant Finale.

ACT III is a royal wedding: it contains many beautiful and entertaining character pieces (Cinderella makes an appearance) but is devoid of dramatic tension. In tonight’s suite, a ceremonial March sets the scene. The entertainments will begin with the lilting music of the Jewel fairies. Then we skip straight to the Finale – a splendid mazurka – and the Apotheosis. Here, Tchaikovsky reminds us that Aurora belongs to another century by quoting ‘Vive Henri IV’, a French tune from 1581 –wrapping Renaissance solemnity in Imperial grandeur.

Yvonne Frindle © 2025

“I’ve benefitted so much from the MSO. I love knowing that my support will enable others to benefit from MSO’s transformative music experiences.”

Jennifer Henry, MSO Guardian and Patron

Leaving a gift in your Will to the MSO ensures your story—and the orchestra you love—lives on in perpetuity. We are honoured to play an important role in your musical journey and invite you to become our next Guardian of the MSO.

Scan the QR code to learn more or call (03) 8646 1551 to speak with a member of the MSO Philanthropy team.

Artists

Thursday 29 May at 7:30pm

Saturday 31 May at 2:00pm

Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Elim Chan conductor

Alexander Gavrylyuk piano

Anna Clyne This Midnight Hour [12’]

Grieg Piano Concerto in A minor, Op 16 [31’]

Interval [20’]

Rimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade – Symphonic Suite, Op. 35 [47’]

Pre-concert talk: Learn more about the performance with musician and ABC Classic presenter Taj Aldeeb on 29 May at 6:45pm and 31 May at 1:15pm in the Stalls Foyer on Level 2 at Hamer Hall

Running time: 2 hours and 15 minutes including interval. Timings listed are approximate. For a list of musicians performing in this concert, please visit mso.com.au/musicians

Alexander Gavrylyuk is internationally recognised for his electrifying and poetic performances. Born in Ukraine and holding Australian citizenship, he gave his first concerto performance when he was nine years old. At 13, he moved to Sydney where he lived until 2006, and early accolades include First Prize and Gold Medal at the Horowitz International Piano Competition (1999), First Prize at the Hamamatsu International Piano Competition (2000) and Gold Medal at the Arthur Rubinstein International Piano Masters Competition (2005).

Alexander collaborates regularly with conductors such as Rafael Payare, Alexandre Bloch, Thomas Søndergård, Donald Runnicles, Juraj Valcuha, Kirill Karabits, Edward Gardner and Gustavo Gimeno. Recent concerto highlights include debuts with Hamburger Symphoniker, Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liege, Australian Chamber Orchestra, Estonian National Symphony, Phil Zuid, Enescu Philharmonic and Taiwan’s National Symphony Orchestra; return visits to the Rotterdam Philharmonic and New Zealand Symphony orchestras; and concerts with the NDR Radio Philharmonic Hannover, San Francisco Symphony and the Chicago and Sydney symphony orchestras.

As a recitalist he has performed at the Vienna Musikverein, Tonhalle Zurich, Victoria Hall Geneva, Southbank Centre (International Piano Series), Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatory, Cologne Philharmonie, Sydney’s City Recital Hall and Melbourne Recital Centre, as well as in Tokyo and San Francisco. He was Artist in Residence at Wigmore Hall for the 2023–24 season, and 2024–25 saw a return to the Concertgebouw Master Pianists Series in Amsterdam and a recital debut at the Philharmonie Luxembourg. He has appeared at many of the world’s foremost festivals and is currently Artist in Residence at Chautauqua Institution.

Anna Clyne (born 1980)

This Midnight Hour

Anna Clyne’s music glows with a radiant beauty. Where some composers may have an impulse to create tightly controlled intellectual puzzles, she rejoices in sounds that warm us like a fire on a cool evening. Clyne grew up in humble circumstances. She was raised on a housing estate in England, and music did not figure heavily in her early life. It was the discovery of the cello that gave her an early inkling of a love for music. It was not until her later teens that she discovered her true calling, composition, and her personal voice emerged quickly.

Her creative inspiration comes from many places. Clyne might paint a series of canvases, or project the shape of handwriting on a wall. Her studio is often covered with a potpourri of handwritten notes, photographs, and art works. She often finds herself, late at night, pacing or dancing in her room to the sounds of a draft of a new piece.

For This Midnight Hour (2015), Clyne was inspired by two poems. ‘Harmonie du soir’ by Charles Baudelaire begins:

The season is at hand when swaying on its stem

Every flower exhales perfume like a censer; Sounds and perfumes turn in the evening air; Melancholy waltz and languid vertigo!

Clyne was drawn to the image of the ‘melancholy waltz’, and drew on folk-like melodies to create ‘a slightly warped waltz melody’.

The work also draws inspiration from a very short poem by Juan Ramón Jiménez:

Music— a naked woman running mad through the pure night!

Clyne translated this powerful image into ‘very fast, accelerating rhythms, very condensed textures’. She also captures a wild, out-of-breath quality in the unpredictable character of the music, which ranges ‘from playful to ominous, to full of energy. It also ranges from

passages that are almost like chamber music, to a full orchestral tutti’.

Clyne writes with the personalities and idiosyncrasies of the performers in mind. In preparing for this work she spent time listening to the commissioning orchestra, the Orchestre national d’Île de France. She was particularly impressed by the deep rich sound of the orchestra’s lower strings, and her first sketch for the work, which also became its opening gesture, leans deeply and heavily on the cellos and double basses.

This Midnight Hour also features some experiments in orchestration. At times Clyne writes for the orchestra like a giant accordion, having the strings tuned slightly apart, to create a trembling, dissonant sound. She also played with the idea of dividing the large string section into many individual parts, creating a texture of richness and complexity.

Tim Munro © 2025

Edvard Grieg (1843–1907)

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16

I. Allegro molto moderato

II. Adagio –

III. Allegro moderato molto e marcato

Alexander Gavrylyuk piano

After hearing a performance of Grieg’s piano concerto, Arnold Schoenberg is supposed to have remarked, ‘That’s the kind of music I’d really like to write’, and one can’t help but feel that there was a wistful sincerity buried in the remark. Grieg’s concerto is, with good reason, popular – a fate not enjoyed by Schoenberg’s music.

Grieg composed the concerto at the age of 25 while relatively inexperienced in orchestral writing and tinkered endlessly with the orchestration between the time of the work’s (triumphant) premiere and his death in 1907. He had studied at the Leipzig Conservatory from the age of 15 with the initial intent of becoming a concert pianist. Dissatisfied with his first teacher, Grieg began lessons with EF Wenzel, a friend and supporter of Robert Schumann’s; under his tutelage Grieg began writing piano music for his

own performances and wrote passionate articles in defence of Schumann’s music.

The influence of Schumann’s Piano Concerto, also in the key of A minor, has been remarked on frequently, but apart from their similar three-movement design and opening gesture (in both works an A minor chord played by the full ensemble releases a florid response from the keyboard soloist), the style of each is markedly different. Both composers were, however, primarily lyricists, and Grieg’s Concerto is certainly replete with exquisite tunes. Many of these echo the Norwegian folk music with which Grieg had become familiar in 1864. The piano’s opening gesture, for instance, recalls folk music in its use of a ‘gapped’ scale, and the origins of the finale in folk dance are clear.

Grieg was unable to attend the premiere of his concerto in Copenhagen in 1869, but it was an outstanding success, no doubt in part because Grieg’s cultivation of folk music struck a chord with the increasingly nationalist Scandinavian audiences. But in large part it was because the concerto was recognised as a youthful masterpiece. Anton Rubinstein, for instance, described it as a ‘work of genius’. A year later, Grieg met Franz Liszt for the second time. Liszt allegedly sightread Grieg’s concerto and said: ‘you have the real stuff in you. And don’t ever let them frighten you!’

Grieg didn’t let them frighten him, and the Piano Concerto went on to establish his reputation throughout the musical world. Audiences responded, as they still do, to the charm of Grieg’s melodies, the balance of, it must be said, Lisztian virtuosity and Grieg’s own distinctive lyricism, and what Tchaikovsky, who adored the work, described as its ‘fascinating melancholy which seems to reflect in itself all the beauty of Norwegian scenery’.

One of Grieg’s greatest admirers described the ‘concentrated greatness and all-lovingness of the little great man. Out of the toughest Norwegianness, out of the most narrow localness, he spreads out a welcoming and greedy mind for all the world’s wares’. This was, of course, the Australian-born pianist–composer Percy Grainger who became one of the concerto’s most celebrated exponents and one of the dearest friends of Grieg’s last years. Not only that – Grainger spent time with Grieg working on the concerto before the composer’s death at which time Grieg was making the final adjustments to the orchestration; with such ‘inside knowledge’ Grainger was able to publish his own edition of the work in later years. Sadly, a proposed tour with Grieg conducting and Grainger playing the concerto never transpired.

Abridged from a note by Gordon Kerry © 2006

In 19th-century Russia, as in many Western nations, the so-called ‘Oriental’ style was a fashion that followed in the footsteps of colonialism and expanding empires. And composers frequently based their works on Eastern themes as an expression of their Russianness. Think: Borodin’s Prince Igor, Balakirev’s Islamey and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade.

‘Orient’ meant different things depending on where you were standing. If you were Russian, it began at home, with those countries that had been absorbed by Imperial Russia, moving south and east, through Turkey, Persia and beyond. For French composers like Saint-Saëns, the ‘Orient’ included North Africa and Spain, which had been influenced by centuries of Moorish presence. Ironically, it also included Russia. And for that we can partly blame Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes. His programming was designed to appeal to a Parisian audience, with Eastern themes and barely disguised erotic overtones, and among his productions was a Scheherazade ballet to Rimsky-Korsakov’s music with a decadent murder-in-the-harem scenario.

Scheherazade – Symphonic Suite, Op. 35

I. Largo e maestoso – Lento –Allegro non troppo

(The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship)

II. Lento

(The Story of the Kalandar Prince)

III. Andantino quasi allegretto (The Young Prince and the Young Princess)

IV. Allegro molto – Vivo – Allegro non troppo e maestoso – Lento (Festival at Baghdad – The Sea –The Ship Goes to Pieces on a Rock Surmounted by a Bronze Warrior –Conclusion)

The Sultan Shahryar, convinced of the duplicity and infidelity of all women, had vowed to slay each of his wives after the first night. The Sultana Shahrazad, however, saved her life by the expedient of recounting to the Sultan a succession of tales over a period of a thousand and one nights.

Our protagonist is Scheherazade, Persian queen and fabled storyteller of The Thousand and One Nights. Some of her stories (and a few that were invented for her by Europeans) have entered popular culture: Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, Aladdin (an 18th-century French addition), and one you’ll recognise from the movement titles for Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade: Sinbad the Sailor.

Strictly speaking, orchestras shouldn’t publish those titles – the composer withdrew them with so as not to constrain our imaginations. Rimsky-Korsakov had taken the idea of Scheherazade and the Arabian Nights as his starting point, and the narrative titles he’d devised in the winter of 1887–88 were intended to suggest particular characters. But the end result, he said, was a ‘kaleidoscope of fairy tale images and designs of Eastern character’, more concerned with the

connotations it brings to mind than with literal storytelling.

Rimsky-Korsakov wanted the music to create an impression of ‘a motley succession of fantastic happenings’, but he believed it was futile to try to link the musical ideas to particular characters and events. He hoped listeners would like the work as purely symphonic music: four brilliantly coloured movements united by common themes. And for the most part, he uses these themes flexibly. The ominous pounding melody that represents the Sultan at the very beginning, for example, turns up in the tale of the Kalandar Prince, in which he plays no part.

At the same time, Rimsky-Korsakov admitted that one motif was quite specific, attached not to any of the stories, but to the storyteller: an intricately winding violin solo that provides a unifying thread to the suite. This is Scheherazade herself, ‘telling her wondrous tales to the stern Sultan’.

It’s Scheherazade’s theme – played by the concertmaster and supported only by the harp – that soothes the thunderous opening and embarks on the first tale: the

Artists

Monday 2 June at 6:30pm Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Elim Chan conductor

Program

Rimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade – Symphonic Suite, Op. 35 [47’]

Introduced by Nicholas Bochner and Elim Chan

The artist biography and program note for this performance can be found on pages 18 and 22.

CONCERT EVENTS

Tonight’s onstage introduction by Nicholas Bochner and Elim Chan will be Auslan interpreted.

For a list of musicians performing in this concert, please visit mso.com.au/musicians

Running time: 1 hour and 15 minutes. Timings listed are approximate.

Quick Fix at Half Six is supported by City of Melbourne. Auslan interpreted performances are supported by the Australian Government Department of Social Services.

Thursday 12 and Saturday 14 June at 7:30pm with a relaxed performance on Friday 13 June at 7:30pm Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne

Artists

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Benjamin Northey conductor

Christian Li* violin

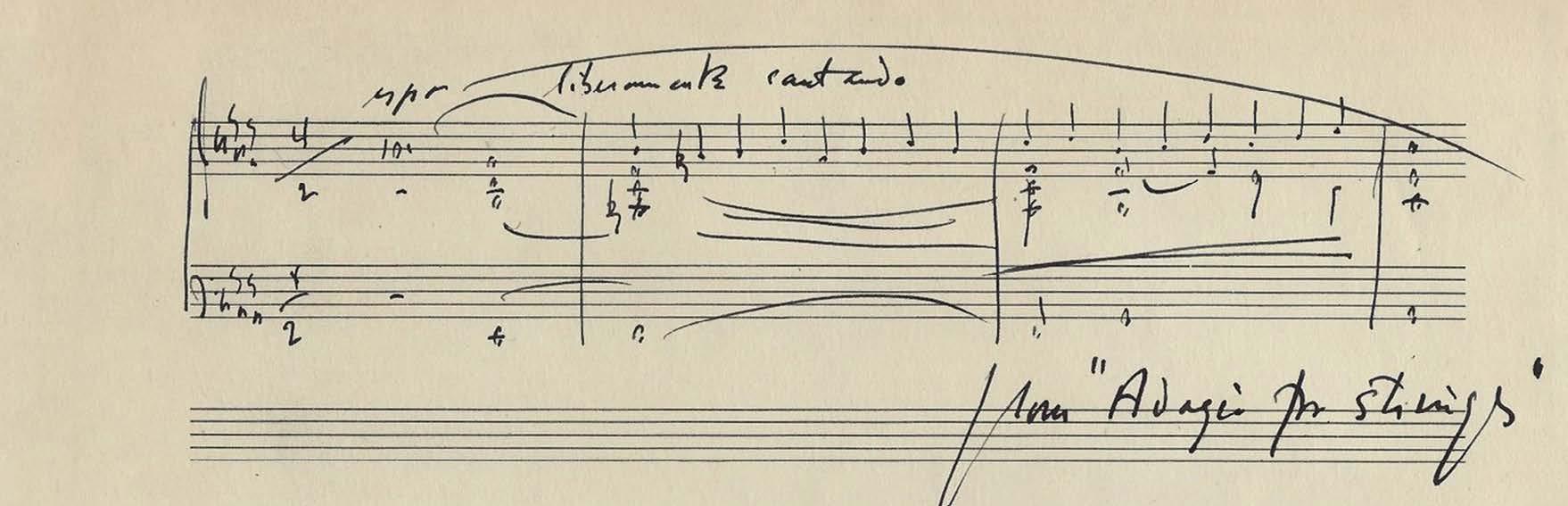

Barber Adagio for strings [9’]

Korngold Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35 [26’]

Interval [20’]

Shostakovich Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47 [50’]

* MSO Young Artist in Association

Pre-concert talk: Learn more about the performance with Luke Speedy-Hutton. 12, 13 and 14 June at 6:45pm in the Stalls Foyer on Level 2 at Hamer Hall

Running time: 2 hours and 5 minutes including interval. Timings listed are approximate. For a list of musicians performing in this concert, please visit mso.com.au/musicians

Relaxed performances are supported by the Australian Government Department of Social Services.

PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR AND ARTISTIC ADVISOR – LEARNING AND ENGAGEMENT

Benjamin Northey is the Chief Conductor of the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra and Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor – Learning and Engagement of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. This year he took up the position of Conductor in Residence with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

He studied conducting at Finland’s Sibelius Academy with Leif Segerstam and Atso Almila, completing his studies at the Stockholm Royal College of Music with Jorma Panula in 2006. He previously studied with John Hopkins at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music (2000–02).

He appears regularly as a guest conductor with all the major Australian symphony orchestras, Opera Australia (La bohème, Turandot, L’elisir d’amore, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte and Carmen), New Zealand Opera (Sweeney Todd) and State Opera South Australia (La sonnambula, L’elisir d’amore and Les Contes d’Hoffmann). He is also active in the performance of new Australian orchestral music, having premiered dozens of new works by Australian composers, and is a driving force in the performance of orchestral music by Australian First Nations composers and performers.

His international appearances include concerts with the London, Tokyo, Hong Kong and Malaysian philharmonic orchestras, Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg, National Symphony Orchestra of Colombia, and the New Zealand and Christchurch symphony orchestras.

An Aria, Air Music and APRA–AMCOS Art Music awards winner, Benjamin Northey was voted Limelight magazine’s Australian Artist of the Year in 2018. His many recordings can be found on ABC Classic.

Born in Melbourne in 2007, Christian Li captured international attention in 2018 when he became the youngest-ever winner of the Junior Menuhin Competition. Soon after, in 2020, he became the youngest artist to sign with Decca Classics and he released his debut album, featuring Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, in 2021, followed in 2023 by his second album, Discovering Mendelssohn. He also made a series of acclaimed concert debuts, appearing with the Sydney and Melbourne symphony orchestras, Australian Brandenburg Orchestra, Auckland Philharmonia, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and Oslo Philharmonic, among others, and gave recitals in Taiwan, Canada, Israel, Norway and the UK.

Christian is the Young Artist in Association with the MSO, a title he has held since 2021. In addition to this week’s concerts with the MSO, highlights of 2025 include a return to the SSO later in June, and a European tour, performing Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto with the Australian Youth Orchestra and conductor David Robertson, followed by a homecoming concert at the Sydney Opera House. Earlier this year he made his debut with the Sofia Philharmonic in Bulgaria.

Christian Li performs on the 1737 ex-Paulsen Guarneri del Gesù violin, on loan from a generous benefactor, and uses a bow by François Peccatte. He currently studies with Robin Wilson (former Head of Violin at ANAM) at the Yehudi Menuhin School and is mentored by David Takeno in London. In his free time, he enjoys reading, swimming and bike riding.

Samuel Barber (1910–1981)

Adagio for strings

Ask a music lover why Barber’s Adagio for strings is such a cathartic and profoundly moving piece of music and you may well find them lost for words. In theory, it’s possible to point to purely musical reasons, such as the seamless rising melodic line, the balanced arch-like structure, the way the phrases flow and breathe, and the anchoring unity that comes from repetition of simple patterns.

But even Barber’s composer colleagues set aside their technical knowledge when trying to explain the success of the Adagio. Aaron Copland heard it as pure sincerity: ‘It’s really well felt, it’s believable you see, it’s not phony. He’s not just making it up because he thinks that it would sound well. It comes straight from the heart…’ Virgil Thomson heard it as ‘a love scene…a detailed love scene…a smooth, successful love scene. Not a dramatic one, but a very satisfactory one.’

As for Samuel Barber himself, he finished the Adagio and declared, ‘it’s a knockout’. Or rather, he said that of the Adagio in its original form: as the slow movement from his Opus 11 String Quartet, completed in 1936. That same year, Barber reworked the music in a rich and weighty version for

string orchestra, and that’s the version everyone knows: the version that was heard in the movie Platoon; that became the music for national mourning in America following the death of Franklin D Roosevelt; and that was added to the BBC’s Last Night of the Proms in the days following September 11, 2001.

Yvonne Frindle © 2007

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897–1957)

Violin Concerto in D, Op. 35

I. Moderato nobile

II. Romance (Andante)

III. Finale (Allegro assai vivace)

Christian Li violin

Leaving most of his family behind, Erich Korngold departed Vienna for Hollywood in January 1938 to compose the music for The Adventures of Robin Hood, expecting to return in a few months. But Germany’s annexation of Austria in March made a return impossible, and his family escaped Austria on the last unrestricted train. Films were now Korngold’s only source of income. When his father berated him for not writing concert music, Korngold replied that if anyone in America wanted

officialdom – ‘A Soviet artist’s reply to just criticism’, assumed at the time to be Shostakovich’s own subtitle for the work.

Solomon Volkov’s book Testimony in 1976, however, painted a portrait of a composer who was at least, to use a psychological term, ‘passive-aggressive’; who knew how to get his views across in ways dull-witted party officials could never detect. Though subsequent commentators scorned Volkov’s claim to have ghostwritten Shostakovich’s memoirs, the contents of the book have not been entirely debunked: Maxim Shostakovich has said that the book depicted the father he knew.

What Volkov and a number of other writers reveal is a composer who did not buckle under official bullying, and who encoded political criticism in his music. Yet, pitted against those writers are also those who claim that music is never so obviously about any overt external subject. What evidence does the music provide?

The Fifth’s first movement is in a clearly recognizable classical sonata form, with jagged first and lyrical second themes; angry-sounding ostinatos on the piano and pizzicato (plucked) basses clearly begin the ‘development section’. This first movement is a far more orderly state of affairs than the explosion of themes which catapults the listener into the opening movement of the Fourth Symphony, composed at the time of the Pravda attack. But possibly Shostakovich withdrew the Fourth from circulation until the 1960s because it was no longer representative of his style anyway.

The second movement of the Fifth is a traditional scherzo with a playful trio, but listeners at the first performance wept during the Largo third movement. Many said how extraordinary it was to be able to experience emotion when the whole society was built on a paranoid secreting of thoughts and feelings.

Much of the debate about the meaning of this symphony revolves around the finale. Officials were quick to hail it as an expression of triumph. But Testimony has Shostakovich say:

I think that it is clear to everyone what happens in the Fifth. The rejoicing is forced, created under threat…. It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick saying, ‘Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing,’ and you rise, shaky, and go marching off, muttering ‘Our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing.’ What kind of apotheosis is that?

When doubts about Testimony first surfaced, writers such as Christopher Norris mocked Western liberals who thought they had discovered ‘cryptic messages of doom and despair’ in music which ‘sounds, to the innocent ear, like straightforward Socialist Optimism’. Yet such a close friend of Shostakovich as the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich has since said, ‘Anyone who thinks the finale is triumph is an idiot.’

With a piece of absolute music such as a symphony, however, it will always be up for debate what’s in the sound of the music.

Gordon Kalton Williams Symphony Australia © 2000/2009

Platinum Patrons ($100,000+)

AWM Electrical

Besen Family Foundation

The Gross Foundation ♡

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio ♡

David Li AM and Angela Li

Lady Primrose Potter AC Anonymous (1)

Virtuoso Patrons ($50,000+)

The Aranday Foundation

Jolene S Coultas

Tim and Lyn Edward ♡ ♫

Dr Harry Imber ♡

Margaret Jackson AC ♡

Lady Marigold Southey AC

The Yulgilbar Foundation

Anonymous (1)

Impresario Patrons ($20,000+)

Christine and Mark Armour

H Bentley

Shane Buggle and Rosie Callanan ♡

Debbie Dadon AM

Catherine and Fred Gerardson

The Hogan Family Foundation

Pauline and David Lawton ♡

Maestro Jaime Martín

Paul Noonan

Elizabeth Proust AO and Brian Lawrence

Sage Foundation ☼

The Sun Foundation

Gai and David Taylor

Maestro Patrons ($10,000+)

John and Lorraine Bates ☼

Margaret Billson and the late Ted Billson ♡

John Calvert-Jones AM and Janet Calvert-Jones AO

Krystyna Campbell-Pretty AM

The late Ken Ong Chong OAM

Miss Ann Darby in memory of Leslie J Darby

Anthony and Marina Darling

Mary Davidson and the late Frederick Davidson AM

Andrew Dudgeon AM ♡

Val Dyke

Kim and Robert Gearon

Dr Mary-Jane H Gething AO ♡

The Glenholme Foundation

Charles & Cornelia Goode Foundation

Cecilie Hall and the late Hon Michael Watt KC ♡ ♫

Hanlon Foundation ♡

Michael Heine

David Horowicz ♡

Peter T Kempen AM ♡

Owen and Georgia Kerr

Peter Lovell

Dr Ian Manning

Janet Matton AM & Robin Rowe

Rosemary and the late Douglas Meagher ♡

Dr Justin O’Day and Sally O’Day

Ian and Jeannie Paterson

Hieu Pham and Graeme Campbell

Liliane Rusek and Alexander Ushakoff

Quin and Lina Scalzo

Glenn Sedgwick ♡

Cathy and John Simpson AM

David Smorgon OAM and Kathie Smorgon

Straight Bat Private Equity

Athalie Williams and Tim Danielson

Lyn Williams AC

The Wingate Group

Anonymous (2)

Arnold Bloch Leibler

Mary Armour

Philip Bacon AO

Alexandra Baker

Barbara Bell in memory of Elsa Bell

Julia and Jim Breen

Nigel and Sheena Broughton

Jannie Brown

Chasam Foundation

Janet Chauvel and the late Dr Richard Chauvel

John Coppock OAM and Lyn Coppock

The Cuming Bequest

David and Kathy Danziger

Carol des Cognets

George and Laila Embelton

Equity Trustees ☼

Bill Fleming

John and Diana Frew ♡

Carrillo Gantner AC and Ziyin Gantner

Geelong Friends of the MSO

The Glavas Family

Louise Gourlay AM

Dr Rhyl Wade and Dr Clem Gruen ♡

Louis J Hamon OAM

Dr Keith Higgins and Dr Jane Joshi

Jo Horgan AM and Peter Wetenhall

Geoff and Denise Illing

Dr Alastair Jackson AM

John Jones

Konfir Kabo

Merv Keehn and Sue Harlow

Suzanne Kirkham

Liza Lim AM ♫

Lucas Family Foundation

Morris and Helen Margolis ♡

Allan and Evelyn McLaren

Dr Isabel McLean

Gary McPherson ♡

The Mercer Family Foundation

Myer Family Foundation

Suzie and Edgar Myer

Rupert Myer AO and Annabel Myer

Anne Neil in memory of Murray A Neil ♡

Patricia Nilsson ♡

Sophie Oh

Phillip Prendergast

Ralph and Ruth Renard

Jan and Keith Richards

Dr Rosemary Ayton and Professor Sam Ricketson AM

Guy Ross ☼

Gillian Ruan

Kate and Stephen Shelmerdine Foundation

Helen Silver AO and Harrison Young

Brian Snape AM

Dr Michael Soon

P & E Turner

The Upotipotpon Foundation

Mary Waldron

Janet Whiting AM and Phil Lukies

Peter Yunghanns

Igor Zambelli

Shirley and Jeffrey Zajac

Anonymous (3)

Associate Patrons ($2,500+)

Barry and Margaret Amond

Carolyn Baker

Marlyn Bancroft and Peter Bancroft OAM

Janet H Bell

Allen and Kathryn Bloom

Alan and Dr Jennifer Breschkin

Drs John D L Brookes and Lucy V Hanlon

Stuart Brown

Lynne Burgess

Dr Lynda Campbell

Oliver Carton

Caroline Davies

Leo de Lange

Sandra Dent

Rodney Dux

Diane and Stephen Fisher

Martin Foley

Steele and Belinda Foster

Barry Fradkin OAM and Dr Pam Fradkin

Anthony Garvey and Estelle O’Callaghan

Susan and Gary Hearst

Janette Gill

R Goldberg and Family

Goldschlager Family Charitable Foundation

Colin Golvan AM KC and Dr Deborah Golvan

Jennifer Gorog

Miss Catherine Gray

Marshall Grosby and Margie Bromilow

Mr Ian Kennedy AM & Dr Sandra Hacker AO

Amy and Paul Jasper

Sandy Jenkins

Sue Johnston

Melissa Tonkin & George Kokkinos

Dr Jenny Lewis

David R Lloyd

Andrew Lockwood

Margaret and John Mason OAM

Ian McDonald

Dr Paul Nisselle AM

Simon O’Brien

Roger Parker and Ruth Parker

Alan and Dorothy Pattison

Peter Priest

Professor Charles Qin OAM and Kate Ritchie

Eli and Lorraine Raskin

Michael Riordan and Geoffrey Bush

Cathy Rogers OAM and Dr Peter Rogers AM

Marie Rowland

Viorica Samson

Martin and Susan Shirley

P Shore

Kieran Sladen

Janet and Alex Starr

Dr Peter Strickland

Russell Taylor and Tara Obeyesekere

Frank Tisher OAM and Dr Miriam Tisher

Margaret Toomey

Andrew and Penny Torok

Chris and Helen Trueman

Ann and Larry Turner

Dr Elsa Underhill and Professor Malcolm Rimmer

Jayde Walker ∞

Edward and Paddy White

Willcock Family

Dr Kelly and Dr Heathcote Wright

C.F. Yeung & Family Philanthropic Fund

Demetrio Zema ∞

Anonymous (19)

Overture Patrons ($500+)

Margaret Abbey PSM

Jane Allan and Mark Redmond

Jenny Anderson

Doris Au

Lyn Bailey

Robbie Barker

Peter Berry and Amanda Quirk

Dr William Birch AM

Anne M Bowden

Stephen and Caroline Brain

Robert Bridgart

Miranda Brockman

Dr Robert Brook

Jungpin Chen

Robert and Katherine Coco

Dr John Collins

Warren Collins

Gregory Crew

Sue Cummings

Bruce Dudon

Dr Catherine Duncan

Brian Florence

Elizabeth Foster

Chris Freelance

M C Friday

Simon Gaites

Lili Gearon

Miles George

David and Geraldine Glenny

Hugo and Diane Goetze

The late George Hampel AM KC and Felicity Hampel AM SC

Alison Heard

Dr Jennifer Henry

C M Herd Endowment

Carole and Kenneth Hinchliff

William Holder

Peter and Jenny Hordern

Gillian Horwood

Oliver Hutton and Weiyang Li

Rob Jackson

Ian Jamieson

Linda Jones

Leonora Kearney

Jennifer Kearney

John Keys

Leslie King

Dr Judith Kinnear

Katherine Kirby

Professor David Knowles and Dr Anne McLachlan

Heather Law

Peter Letts

Halina Lewenberg Charitable Foundation

Helen MacLean

Sandra Masel in memory of Leigh Masel

Janice Mayfield

Gail McKay

Jennifer McKean

Shirley A McKenzie

Richard McNeill

Marie Misiurak

Joan Mullumby

Adrian and Louise Nelson

Marian Neumann

Ed Newbigin

Valerie Newman

The MSO gratefully acknowledges the support of the following Estates

Norma Ruth Atwell

Angela Beagley

Barbara Bobbe

Michael Francois Boyt

Christine Mary Bridgart

Margaret Anne Brien

Ken Bullen

Deidre and Malcolm Carkeek

Elizabeth Ann Cousins

The Cuming Bequest

Margaret Davies

Blair Doig Dixon

Neilma Gantner

Angela Felicity Glover

The Hon Dr Alan Goldberg AO QC

Derek John Grantham

Delina Victoria Schembri-Hardy

Enid Florence Hookey

Gwen Hunt

Family and Friends of James Jacoby

Audrey Jenkins

Joan Jones

Pauline Marie Johnston

George and Grace Kass

Christine Mary Kellam

C P Kemp

Jennifer Selina Laurent

Sylvia Rose Lavelle

Dr Elizabeth Ann Lewis AM

Peter Forbes MacLaren

Joan Winsome Maslen

Lorraine Maxine Meldrum

Professor Andrew McCredie

Jean Moore

Joan P Robinson

Maxwell and Jill Schultz

Miss Sheila Scotter AM MBE

Marion A I H M Spence

Molly Stephens

Gwennyth St John

Halinka Tarczynska-Fiddian

Jennifer May Teague

Elisabeth Turner

Albert Henry Ullin

Cecilia Edith Umber

Jean Tweedie

Herta and Fred B Vogel

Dorothy Wood

Joyce Winsome Woodroffe

The MSO honours the memory of Life Members

The late Marc Besen AC and the late Eva Besen AO

John Brockman OAM

The Hon Alan Goldberg AO QC

Harold Mitchell AC

Roger Riordan AM

Ila Vanrenen

The MSO relies on the generosity of our community to help us enrich lives through music, foster artistic excellence, and reach new audiences. Thank you for your support.

♡ Chair Sponsors – supporting the beating heart of the MSO.

2025 Europe Tour Circle patrons –elevating the MSO onto the world stage.

☼ First Nations Circle patrons –supporting First Nations artist development and performance initiatives.

♫ Commissioning Circle patrons –contributing to the evolution of our beloved art form.

∞ Future MSO patrons – the next generation of giving.

The MSO welcomes support at any level. Donations of $2 and over are tax deductible.

Listing current as of 7 May

MSO Board

Chair

Edgar Myer

Co-Deputy Chairs

Martin Foley

Farrel Meltzer

Board Directors

Shane Buggle

Lorraine Hook

Margaret Jackson AC

Gary McPherson

Mary Waldron

Company Secretary

Randal Williams

MSO Artistic Family

Jaime Martín

Chief Conductor and Artistic Advisor

Benjamin Northey

Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor – Learning and Engagement

Leonard Weiss CF Cybec Assistant Conductor

Sir Andrew Davis CBE † Conductor Laureate (2013–2024)

Hiroyuki Iwaki † Conductor Laureate (1974–2006)

Warren Trevelyan-Jones

MSO Chorus Director

James Ehnes Artist in Residence

Karen Kyriakou Artist in Residence – Learning and Engagement

Christian Li Young Artist in Association

Liza Lim AM Composer in Residence

Klearhos Murphy

Cybec Young Composer in Residence

James Henry

Cybec First Nations Composer in Residence

Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO

First Nations Creative Chair

Xian Zhang, Lu Siqing, Tan Dun

Artistic Ambassadors