Volume 59 | No. 3 | September 2021

Time to introduce mentorship into surgical training programmes?

Surgery in South Africa – challenges and barriers

Editor Prof. J E J Krige

Deputy Editors Prof. E Panieri

Surgery in South Africa – the attitudes toward mentorship in facilitating general surgical training

Prof. S R Thomson

Emeritus Editors

Prof. C G Bremner

Surgical rib fixation as an alternative method of treatment for multiple rib fractures: an audit of results compared with traditional medical management

Prof. M R Q Davies

Prof. G J Oettlé

The spectrum of blunt abdominal trauma in Pietermaritzburg

The correlation between full moon and admission volume for penetrating injuries at a major trauma centre in South Africa

Manuscript Supervisor Sue Parkes, Department Medical School, York Tel. (011) 717-2080

E-mail: susan.parkes@wits.ac.za

An analysis of paediatric snakebites in north-eastern South Africa

An audit of patients clinically deemed as high risk for malignant breast pathology at the Helen Joseph Hospital Breast Clinic

The surgical burden of breast disease in KwaZulu-Natal province

Associate Editors J P Apffelstaedt, Stellenbosch

P C Bornman, UCT E Degiannis, Wits A Dhaffala, Transkei R S du Toit, Bloemfontein

D Kahn, UCT

An audit of patients presenting with clinically benign breast disease to the Helen Joseph Hospital Breast Imaging Unit

Clinicopathological spectrum of small bowel obstruction and management outcomes in adults – experience at a regional academic hospital complex

T E Madiba, Natal T Mokoena, Pretoria M D Smith, Wits M G Veller, Wits B Warren, Stellenbosch

The spectrum of abdominal wall desmoid fibromatosis and the outcomes of its surgical treatment

_____________

Published by the HEALTH & MEDICAL

A 7-year retrospective review of renal trauma in paediatric patients in Johannesburg

Editor-in-Chief Janet Seggie

Diabetes and lower extremity amputation – rehabilitation pathways and outcomes at a regional hospital

Factors affecting bacteriology of hand sepsis in South Africa

Cardiac tamponade following post-pericardiotomy syndrome

An inguinal hernia imposter

Deputy Editor Bridget Farham

Editorial Systems Manager Melissa Raemaekers

Scientific Editor

Ingrid Nye

The role of surgery in Conn’s syndrome – a case of refractory hypertension secondary to an aldosterone secreting adenoma

Biliary tract anatomical variance – the value of MRCP

Technical Editors

Emma Buchanan

Paula van der Bijl

Head of Publishing

Robert Arendse

Production

Bronlyne Granger

Art Director

Brent Meder

DTP,

Carl Sampson

&

Edward Macdonald

Head of Sales and Marketing

Diane Smith

Volume 52 | No. 4 | November 2014

Coordinator

Setting

Layout

Manager

Distribution

91 Developing a clinical model to predict the need for relaparotomy in severe intra-abdominal sepsis secondary to complicated appendicitis V Y Kong, S van der Linde, C Aldous, J J Handley, D L Clarke 96 Exposure to key surgical procedures during specialist general surgical training in South Africa 101 An audit of trauma-related mortality in a provincial capital in South Africa N B Moodley, C Aldous, D L Clarke 105 Propeller flaps for lower-limb trauma 108 Regional anaesthesia for cleft lip surgery in a developing world setting V Malherbe, A T Bosenberg, A K Lizarraga Lomeli, C Neser, C H Pienaar, A Madaree 111 Haemangiopericytoma/solitary fibrous tumour of the greater omentum J H R Becker, M Z Koto, O Y Matsevych, N M Bida 114 Largest recorded non-invasive true intrathoracic desmoid tumour G R Alexander 116 The mystical foot with pink mushrooms: Imaging of maduromycosis –a rarity in southern Africa G Jackson, N Khan 118 Isolated gallbladder perforation following blunt abdominal trauma S Cheddie, C G Manneh, N M Naidoo OBITUARY 120 Hamid Ismail Yakoob D Kahn

CONTENTS

ISSN 0038-2361

Official Journal of the Association of Surgeons of South Africa ORIGINAL, PEER-REVIEWED CLINICAL RESEARCH

Granisetron Fresenius 1 mg/ml (1 ml)

Granisetron Fresenius 1 mg/ml (3 ml)

Concentrate for solution for injection/infusion

INDICATIONS: For the prevention or treatment of nausea and vomiting induced by cytostatic therapy (chemotherapy and radiotherapy) and for the prevention and treatment of post-operative nausea and vomiting.1

Identifies Granisetron Fresenius1

For full prescribing information refer to professional information approved by the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority.

S4 GRANISETRON FRESENIUS 1 mg/ml (1 ml): 44/5.7.2/0671 S4 GRANISETRON FRESENIUs 1 mg/ml (3 ml): 44/5.7.2/0672

Reference: 1. Fresenius Kabi data on file.

Fresenius Kabi South Africa (Pty) Ltd, Reg. No.: 1998/006230/07 Stand 7, Growthpoint Business Park 162 Tonetti Street, Halfway House Extension 7, Midrand, Gauteng, 1685 PO Box 4156, Halfway House 1685 Tel: + 27 11 545 0000

Fax: + 27 11 545 0060

www.fresenius-kabi.co.za

IMA_13_3_2021_V1

Identifies the location of a small cut to help breaking/ opening the ampoule1

IN STOCK

EDITORIAL

74 Time to introduce mentorship into surgical training programmes? J Edge

GENERAL SURGERY SURVEYS

77 Surgery in South Africa – challenges and barriers

P Naidu, I Buccimazza

82 Surgery in South Africa – the attitudes toward mentorship in facilitating general surgical training

P Naidu, I Buccimazza

TRAUMA

86 Surgical rib fixation as an alternative method of treatment for multiple rib fractures: an audit of results compared with traditional medical management

BI Monzon, LM Fingleson, MS Moeng

90 The spectrum of blunt abdominal trauma in Pietermaritzburg

P Rhimes, S Moffatt, VY Kong, JL Bruce, MTD Smith, W Bekker, GL Laing, DL Clarke

94 The correlation between full moon and admission volume for penetrating injuries at a major trauma centre in South Africa

VY Kong, AA Keizer, MM Donovan, RD Weale, NS Rajaretnam, JL Bruce, A Elsabagh, DL Clarke

97 An analysis of paediatric snakebites in north-eastern South Africa

JJP Buitendag, S Variawa, D Wood, G Oosthuizen

BREAST DISEASE

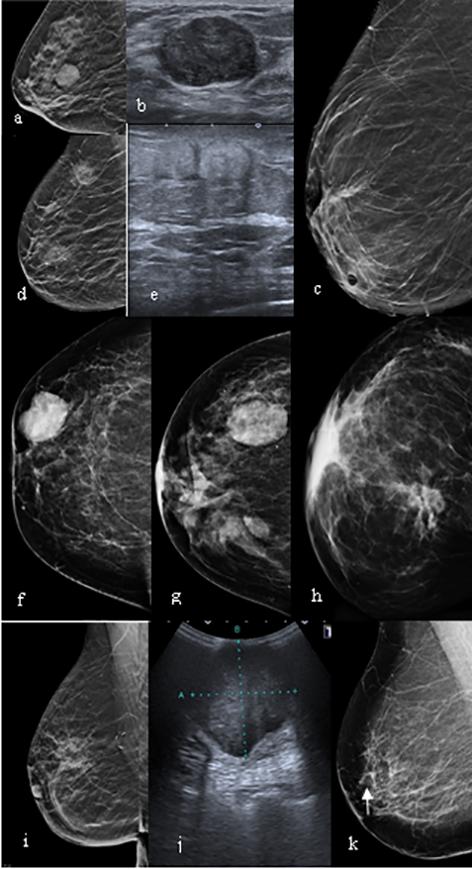

102 An audit of patients clinically deemed as high risk for malignant breast pathology at the Helen Joseph Hospital Breast Clinic

H-M Brink, G Rubin, C-A Benn, S Lucas

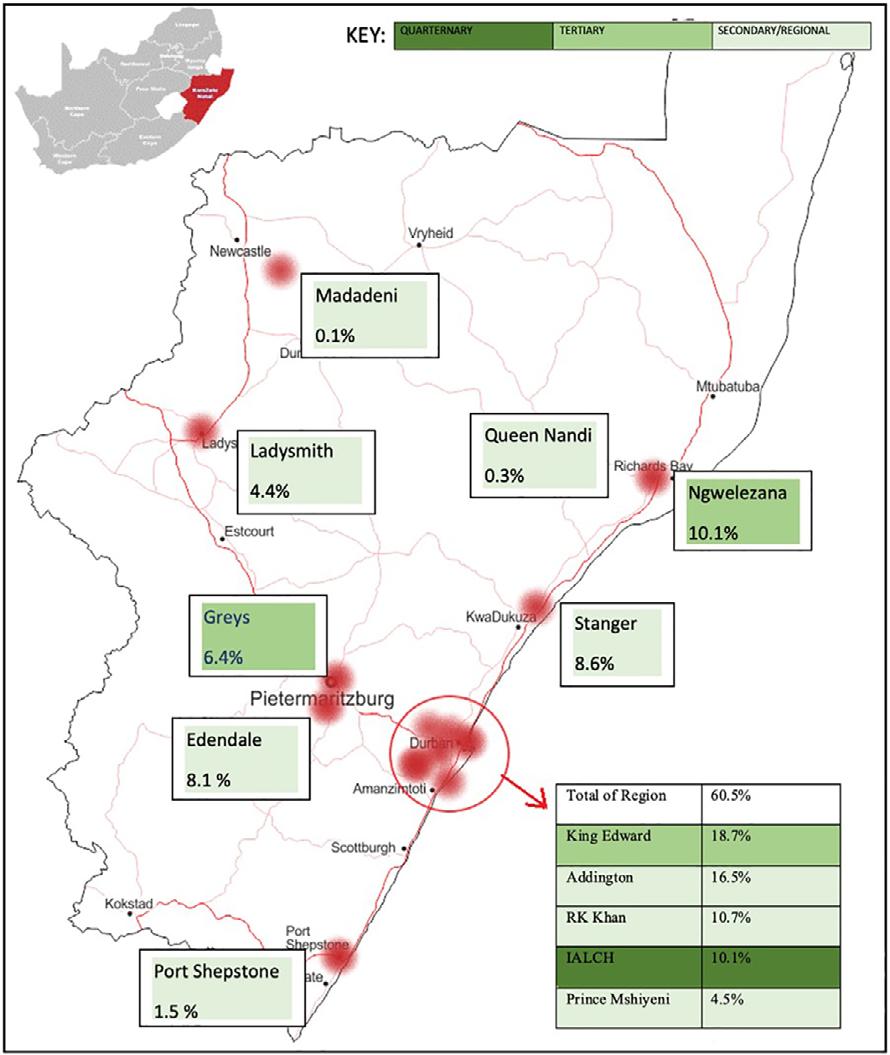

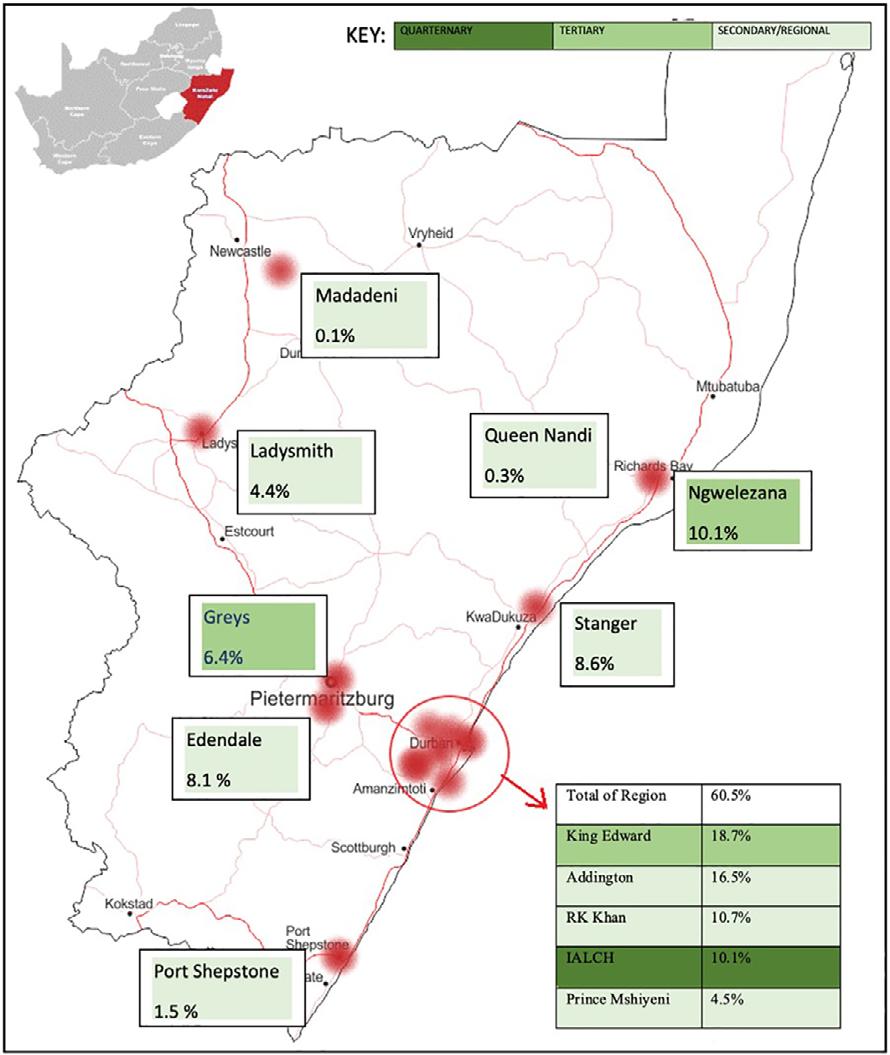

108 The surgical burden of breast disease in KwaZulu-Natal province

VU Ehlers, CF Kohler, E Lutge, A Tefera, DL Clarke, I Buccimazza

113 An audit of patients presenting with clinically benign breast disease to the Helen Joseph Hospital Breast Imaging Unit

NC Christofides, G Rubin, C-A Benn

GENERAL SURGERY

118 Clinicopathological spectrum of small bowel obstruction and management outcomes in adults – experience at a regional academic hospital complex

MR Mthethwa, C Aldous, TE Madiba

124 The spectrum of abdominal wall desmoid fibromatosis and the outcomes of its surgical treatment

I Bombil, L Ngobese

ARTICLES ONLINE

127 A 7-year retrospective review of renal trauma in paediatric patients in Johannesburg

NZ Mashavave, A Withers, T Gabler, V Lack, D Harrison, J Loveland

128 Diabetes and lower extremity amputation – rehabilitation pathways and outcomes at a regional hospital

P Manickum, SS Ramklass, TE Madiba

129 Factors affecting bacteriology of hand sepsis in South Africa

M van der Vyver, A Maderee

CASE REPORTS ONLINE

130 Cardiac tamponade following post-pericardiotomy syndrome

K Gandhi, JSK Reinders, PH Navsaria

130 An inguinal hernia imposter

RR Patel, S Tu, J Plaskett

131 The role of surgery in Conn’s syndrome – a case of refractory hypertension secondary to an aldosterone secreting adenoma

MD Carides, NT Sishuba, I Bombil, C Christofides

131 Biliary tract anatomical variance – the value of MRCP

C Ferreira, CB Noel

132 CPD

Editor Prof. S R Thomson

Deputy Editors

Dr I Buccimazza

Prof. E Panieri

Emeritus Editors

Prof. C G Bremner

Prof. M R Q Davies

Prof. G J Oettle

Prof. J E J Krige

Manuscript Supervisor

Susan Parkes (Secretariat), Association of Surgeons of South Africa

E-mail: susanparkes@mweb.co.za

Associate Editors

Prof. D Clarke

Dr T Hardcastle

Prof. E Jonas

Prof. P Navsaria

Prof. A J Nicol

Publisher

Medical and Pharmaceutical

Publications (Pty) Ltd. trading as

Production

Robyn Marais

Ina du Toit

Chandré Blignaut

Layout

Celeste Strydom

Sales

Asnath Masogo

Cell: 079 413 0119

E-mail: asnath@medpharm.co.za

Plagiarism is defined as the use of another’s work, words or ideas without attribution or permission. No manuscript which includes plagiarised material will be considered for publication in the SAJS. For more information on our plagiarism policy, please visit http://www.sajs.org.za

No.

September

Volume 59 |

3 |

2021 meeting expectations

https://doi.org/10.17159/2078-5151/2021/v59n3a3753

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0]

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0

Time to introduce mentorship into surgical training programmes?

J Edge

Division of Surgery, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

Corresponding author, email: dr@jennyedge.co.za

I didn’t realise it, but as a junior doctor working in New Zealand, I had the privilege of having my first mentor. She was an older woman, Dr Ira, a radiologist from Sri Lanka. At the time, I was working as the only female in the department of general surgery and battling with my male colleagues. After a particularly bruising incident, I went down to see her to complain. She gave me advice I have never forgotten. She introduced me to silence as a reply. It is a powerful weapon. You never regret what you haven’t said. It gives you space to contemplate the situation and eventually formulate a reply.

In 2020 the Association of Surgeons of South Africa (ASSA) sent out a questionnaire to all its members. The results have been published in two articles written by Naidu and Buccimazza and published in this edition of the SAJS. The first addresses challenges and barriers to pursuing a career in surgery in South Africa.1 The second article elucidates the attitudes toward mentorship among South African general surgeons.2 One hundred and twenty-nine respondents took part in the study overall. The majority (67%) were specialist surgeons and 18% registrars. Over half (53%) reported having suffered from burnout.1 Fiftyfour per cent reported not having a mentor, however, 80% felt mentorship is an important part of surgical training.2

The results of burnout are similar to those reported in other international studies. In a meta-analysis evaluating burnout amongst physicians in the USA, an estimated 67% reported having had symptoms.3 In 2019, the results from a questionnaire sent to all surgical trainees in the USA were published in NEJM.4 They asked about the incidence and source of abuse and discrimination, symptoms of burnout, and frequency of events. Ninety per cent experienced symptoms of burnout in the preceding year; 38.5% reported experiencing symptoms of burnout within the preceding week. There was an increased incidence of burnout amongst trainees who were subject to discrimination and harassment. Interestingly, the major source of most categories of abuse and discrimination was from patients and patients’ families.

As part of a quality improvement process in the Division of Surgery, Stellenbosch University, we conducted a similar anonymous survey in 2019 and 2020. Approximately 20 trainees responded. Specific questions about burnout were not asked but they were asked about incidents of discrimination and verbal abuse and their source. They also reported that the most common source of abuse and discrimination was from patients and their families. They were asked to indicate what the department could do to support them. The introduction of mentoring programmes was amongst the most popular options chosen.

The word mentor was first introduced by Homer in the 8th century in his epic poem the Odyssey. In the poem, Mentor was a friend of Odysseus. When Odysseus was called to war, he asked Mentor to take over the care of his son. And so, the concept of mentoring was formed. There are varied definitions of mentoring, and it can be applied in different ways. Naidu and Buccimazza describe the goal of a mentorship programme “to support and guide individuals through career and leadership development”.1 Programmes can be introduced on a one-to-one basis or can be run in groups. Many informal initiatives exist within surgical departments, however, the problem with having an informal structure is that extrovert registrars tend to benefit more than introverted registrars.

Whilst watching tennis, the surgeon Atul Gawande asked himself “If Rafael Nadal has a coach, how come lawyers and teachers and journalists don’t? Specifically, how come surgeons don’t”.5 Coaching is a self-directed process that is ongoing and facilitated by a trained instructor. Although there are identifiable goals, there are no measurable parameters. In that way, coaching and mentoring are similar.

Most surgical departments in South Africa are unlikely to be able to afford a formal coaching programme. However, why hasn’t there been widespread adoption of formal membership programmes within surgical training? There are many reasons cited. The most common objections are from the senior staff within the department. Generally, the people who would be mentors. I believe it is true to say that more attention is paid to the burnout rate among surgical trainees than to that among senior colleagues. There is a perception that adding a mentoring programme in a department adds to their work. Importantly, the study that was done by Naidu and Buccimazza demonstrates that senior surgeons recognise the importance of mentorship programmes and that they too experience burnout.

The fact we work in a resource-constrained setting with exceptionally high trauma volumes places extra burden on all surgeons. COVID-19 has diminished access to health care for our patients and there is a perception that we are all seeing surgical patients with more advanced disease. Although the survey done in our department was too small to claim a causal link to COVID-19, a higher percentage of trainees reported incidences of verbal abuse in 2020 compared to 2019.

There are many tools that can be used for educational purposes. Teaching, mentoring, and coaching are the most employed techniques worldwide. Ubuntu is an African concept that has been used to good effect in selected

74 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021 South African Journal of Surgery

038-2361

The

EDITORIAL

ISSN

© 2021

Author(s)

South African Journal of Surgery.

2021;59(3):74-76

BREAK OUT OF THE PAIN LIVE AGAIN. STILPANE

• Relief of short-term pain associated with anxiety and tension

• Effective in acute and post-operative pain treatment1

• Available in tablets (with caffeine) and capsules (without caffeine)

• Capsules are more suitable for CV or GI sensitive patients as it does not contain caffeine2,3

• Trusted, Affordable, Effective Relief1

CV: cardiovascular; GI: gastrointestinal References: 1. Outhoff K, Dippenaar JM, Nell M, et al. A randomised clinical trial comparing the analgesic and anxiolytic efficacy and tolerability of Stilpane® and Tramacet® after third molar extraction. SA J Anesthes Analg 2015; 21(2): 40-45. 2. Temple JL, Bernard C, Lipshultz SE, et al. The safety of ingested caffeine: A comperehensve review. Front Psych 8:80.doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00080. 3. Tavares C, Sakata RK. Caffeine in the treatment of pain. Revista Brasileira de Anestesiologia 2012; 62(3): 387-401. S5 STILPANE Tablets. Reg. No.: M/2.9/2. Each tablet contains paracetamol 320 mg, codeine phosphate 8 mg, caffeine anhydrous 32 mg, meprobamate 150 mg. S5 STILPANE Capsules. Ref. No.: B624 (Act 101/1965). Each capsule contains paracetamol 320 mg, codeine phosphate 8 mg, meprobamate 150 mg. For full prescribing information, refer to the professional information approved by the medicines regulatory authority (Tablets 11/1979, Capsules 03/1969). Trademarks are owned by or licensed to the Aspen Group of companies. © 2020 Aspen Group of companies or its licensor. All rights reserved. Marketed by Aspen Pharmacare for Pharmacare Limited. Co. Reg. No.: 1898/000252/06. Healthcare Park, Woodlands Drive, Woodmead, 2191. ZAR-CCM-07-20-00001 07/20. STEP OUT OF THE PAIN.

circumstances.6 The conventional modality utilised to train a surgeon is teaching with assessment by specialist exit exams. Teaching or training is a formal structured process whereby an individual learns specific skills. There is generally a curriculum that is followed and once the competence has been achieved, the process is complete. Atul Gawande looked for excellence in sport to form his opinion about the need for alternative education modalities that could be implemented to help the process of training a good rather than an ordinary surgeon.

Some of the barriers to choosing a surgical career in South Africa have been illustrated by this local questionnaire. If, as a profession, we are going to be able to continue recruiting bright medical trainees, train them and help them develop the resilience needed for a lasting career, we need to involve them in both identifying problems and working towards solutions. Group mentorship programmes are one way of achieving both: getting suggestions from the “shop floor” and being able to provide guidance and support.7 The survey carried out by ASSA is a move in the right direction.

One of the attributes of mentoring is that the mentee may choose their mentor. It may happen informally, as it did to me, and may or not be a person from an aligned profession. There is no doubt that my career path has been altered by the sage words from my mentor, Dr Ira. It behoves all of us in our profession to move on from simply being a teacher and to integrate the principles of mentoring and coaching into our daily surgical practice.

REFERENCES

1. Naidu P, Buccimazza I. Surgery in South Africa – challenges and barriers. S Afr J Surg. 2021;59(3):77-81. https://doi. org/10/17159/2078-5151/2021/v59n2a3391.

2. Naidu P, Buccimazza I. Surgery in South Africa – the attitudes toward mentorship in facilitating general surgical training. S Afr J Surg. 2021;59(3):82-85

3. Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians. A systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131-50. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018. 12777.

4. Hu Y-Y, Ellis RJ, Brock Hewitt D, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741-52. https://doi.org/10.1056/ NEJMsa1903759.

5. The New Yorker 2013. Available from: https://www. newyorker.com/video/watch/atul-gawandedo-surgeons-needcoaches. Accessed 19 Jul 2021.

6. Clutterbuck DA, editor. Case studies of mentoring across the globe, part 1V. The SAGE Handbook of Mentoring. 1st ed. Chapter 31. SAGE.

7. Henry-Noel N, Bishop M, Gwede CK, Petkova E, Szumacher E. Mentorship in medicine and other health professions. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(4):629-37. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s13187-018-136.

76 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021

South African Journal of Surgery. 2021;59(3):77-81

https://doi.org/10.17159/2078-5151/2021/v59n3a3391

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0]

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0

Surgery in South Africa – challenges and barriers

P Naidu,1 I Buccimazza2

1 Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

2 Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Corresponding author, email: pnaidu2012@gmail.com

Background: Sustaining a surgical career can be challenging and there are numerous barriers to pursuing a career in surgery. These barriers and challenges are well reported in international literature, but there is a lack of knowledge on how this affects surgeons in South Africa. This study aimed to determine the barriers and challenges that South African surgeons face in their training and careers.

Methods: A 15-item questionnaire was designed and distributed via the Research Electronic Database Capturing software from 1 February–3 April 2020. Data were analysed in Stata 15 SE. All responses were anonymised.

Results: One hundred and twenty-nine participants responded to the questionnaire, 33 (26%) of whom were female. The majority were specialist surgeons (n = 87; 71%). One hundred and eleven participants (90%) reported they did not regret pursuing surgery. Barriers to pursuing surgery included limited personal time (n = 98; 76%), heavy surgical workload (n = 92; 71%), and difficulty taking leave of absence (n = 64; 50%), limited postgraduate training (n = 34; 26%), and verbal discouragement (n = 22; 17%). Challenges included difficulty maintaining work-life balance (n = 74; 56%), racial discrimination (n = 29; 23%) and gender discrimination (n = 15; 12%). Fifty-three per cent of participants experienced burnout.

Conclusion: Despite high career satisfaction, South African surgeons face numerous barriers to pursuing and challenges in sustaining a career in surgery and often experience burnout. These barriers and challenges disproportionately affect female surgeons and can be mitigated through formalised mentorship programmes, flexible work schedules, funding for postgraduate training, and training in diversity and discrimination.

Keywords: surgery, training, challenges, barriers

Appendix 1 available online: http://sajs.redbricklibrary.com/index.php/sajs/article/view/3391

Introduction

A career in surgery, while rewarding, is known to be highly competitive and demanding.1,2 The surgical work environment is challenging and fraught with mistreatment, which presents barriers to pursuing and difficulty in sustaining a surgical career.2

Reported challenges in the surgical workplace include discrimination on the basis of gender, race, pregnancy or childcare status; verbal, emotional, and physical abuse; sexual harassment; duty-hour violations; and genderbased salary discrepancies.3 These challenges perpetuate emotional and physical exhaustion and often deter medical students and junior doctors from pursuing a career in surgery.4 Overwhelming time commitments, lack of worklife balance, and disruption of personal life have all been cited as reasons for burnout, a common phenomenon among surgeons and surgical trainees.3,5 Nearly half the surgical resident workforce in the United States of America (USA) has reported burnout and one in 20 have reported suicidal ideation as a result of these workplace challenges.3,6,7 In sub-Saharan Africa, the demand on a surgical career is substantial owing to the high burden of surgical disease and lack of providers.8,9 These challenges may adversely affect the well-being of both patient and provider.10 In addition to

burnout, surgeons often neglect their physical, spiritual and emotional health, and fail to seek medical attention following occupational injuries.10,11 Among female surgeons, higher rates of pregnancy complications and infertility have been reported.12

A surgical career can be particularly challenging for women who have to balance work schedules with pregnancy and motherhood, and work in a traditionally male-dominated field which can sometimes be hostile and unaccommodating.13 Female surgeons experience greater discrimination than their male counterparts, have greater barriers to pursuing a surgical career, and fewer opportunities for career advancement, particularly with respect to academia.13,14

While challenges such as long work hours and poor worklife balance are common across both genders, South African female surgeons face unique challenges. In a study by Roodt, one-third of participants, mostly male surgeons, felt that an increased number of female surgeons complicated or disrupted the departmental routine and the majority perceived males to be better suited to a career in surgery than females.4 Apart from this single-centre study in the Western Cape, there is a paucity of literature on the challenges of a surgical career among South African surgeons and trainees.

77 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021 South African Journal of Surgery

ISSN 038-2361

SURGERY SURVEY

© 2021 The Author(s) GENERAL

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the challenges of and barriers to pursuing a career in surgery amongst all surgical cadres throughout South Africa. A secondary objective was to establish whether some of these challenges and barriers are unique to female surgeons.

Methods

A 15-item questionnaire was designed on the Research Electronic Database Capture platform and included questions on both barriers to pursuing a career in surgery and challenges of a surgical career (as detailed in Appendix 1). The questions in the survey were informed by questions asked in previous studies, however, the survey was not a validated questionnaire or tool. Both male and female participants were asked questions on barriers and challenges, including questions on discrimination. The survey was circulated electronically to qualified general surgeons who are members of the Association of Surgeons of South Africa (ASSA) and/or Surgicom, and general surgical trainees/ medical officers through the various heads of surgical departments. Respondents could access the survey from 1 February–3 April 2020. Data were analysed in Stata 15 SE. All responses were anonymised and no identifying data were analysed. The ASSA committee approved the questionnaire for dissemination to its members. Ethical approval for this study was obtained (information removed for blinding). Descriptive analyses were performed as proportions, means and medians. Measures of association were performed

using chi-squared tests. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A specialist surgeon was defined as any surgeon who had qualified with a specialist degree in any surgical specialty and was currently employed as a consultant.

78 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021

Definitions

Characteristics n (%) Gender Male 96 (74%) Female 33 (26%) Age 20–29 8 (6%) 30–39 36 (28%) 40–49 25 (19%) > 50 60 (47%) Marital status Married 94 (73%) Single 14 (11%) Non-marital relationship 10 (8%) Divorced 10 (8%) Other 1 (1%) Training/practice location Western Cape 42 (33%) Gauteng 41 (32%) KwaZulu-Natal 24 (19%) Free State 8 (6%) North West 5 (4%) Eastern Cape 3 (2%) Limpopo 3 (2%) Northern Cape 2 (2%) Mpumalanga 1 (1%)

Table I: Demographic characteristics of respondents (n = 129)

Position Specialist surgeon 87 (71%) Registrar 23 (19%) Fellow 8 (7%) Medical officer in surgery 5 (4%) Number of years in practice (median; IQR) 18 (10–28) Sub-specialty No 76 (66%) Yes 39 (34%) Type of subspecialty Colorectal 9 (23%) Gastroenterology 7 (18%) Breast and endocrine 5 (13%) Hepatobiliary 4 (10%) Trauma 3 (8%) Vascular 3 (8%) Bariatrics 1 (3%) Paediatric surgery 1 (3%) Transplant 1 (3%) Not specified 5 (11%) Type of post Full-time public 53 (43%) Full-time private practice 40 (33%) Part-time public with RWOPs 8 (7%) Full-time private with public sessions 7 (6%) Part-time public 4 (3%) Employed abroad 2 (2%) Limited private practice 2 (2%) Other (retired/supernumerary/lecturer) 7 (14%) Reason for choosing surgery as a career *participants were allowed to selected multiple options Technical aspect 69 (53%) Acute element of surgery 66 (51%) Inspired by role model 49 (38%) Academic competitiveness 18 (14%) Prestige 8 (6%) Family pressure 2 (2%) Other 13 (10%) Regret choice to pursue surgery? No 111 (90%) Yes 12 (10%)

Table II: Surgical career characteristics of respondents (n = 129)

Results

One hundred and twenty-nine participants responded to the survey, 33 (26%) of whom were female and 60 (47%) were over the age of 50 years (Table I). The majority of respondents (84%) were from the Western Cape, Gauteng, and KwaZulu-Natal. Specialist surgeons accounted for 71% of the responses (n = 87) and the median number of years in practice was 18 (IQR 10–28) (Table II). Most respondents were in full-time public practice (n = 53; 43%). The desire to pursue a surgical career was informed by a variety of reasons: technical aspect of surgery (n = 69; 53%), acute element of surgery (n = 66; 51%), inspired by a role model (n = 49; 38%), academic competitiveness (n = 18; 14%), prestige of surgery (n = 8; 6%), or family pressure (n = 2; 2%).

Many candidates perceived the demands of surgery, including a lack of personal time (76%), heavy workload associated with surgery (71%), and difficulty taking leave of absence (50%), as potential barriers to a surgical career (Table III). More than half of the participants reported a lack of personal time to spend with family or for outside interests. Specific barriers to training included limited opportunities for postgraduate training (26%) and the cost of training (9%), as well as verbal discouragement (17%) and a lack of mentorship (11%).

Unique challenges of a surgical career related to a lack of a work-life balance (57%), with 53% of participants reporting burnout. Specialist surgeons were more likely to experience burnout than any other position, although not statistically significant (p = 0.06). Other challenges related to a hostile work environment, including negative experiences with colleagues and discrimination and abuse of varying forms (Table IV). More participants reported negative experiences with male colleagues than with female colleagues (p = 0.02). In addition to challenges, candidates also suggested aspects that would facilitate surgical training, including formalised mentorship programmes (49%), scholarships or funding to pursue postgraduate surgical training (47%), and more flexible work schedules (36%) (Table IV).

Discrimination

Both males and females were asked to report if they believed gender discrimination was a challenge in their surgical career; gender discrimination was reported as a challenge among 15 out of 33 females (45%) and zero out of 96 males (0%). Females were more likely than males to pursue surgery if inspired by a role model (p = 0.007) or due to family pressure (p = 0.015). With respect to barriers to pursuing a surgical career, 45% of females (n = 15) reported gender discrimination and were more likely than males to experience verbal discouragement (p < 0.001). Females more than males reported limited time to have a child (p = 0.002). Additionally, females were also more likely to report sexual harassment than males (p < 0.001). Female surgeons reported unique challenges including having to impersonate male qualities to toughen up (n = 11; 33%), not being treated equally to their male colleagues (n = 15; 45%), and a hostile culture toward females (n = 9; 27%).

Other forms of discrimination and abuse included racial discrimination (n = 29; 23%), physical abuse (n = 15; 12%), and sexual harassment (n = 7; 5%).

There were statistically significant differences in challenges reported by males compared with females

(Table IV). While these challenges were reported by both males and females, female participants were more likely to report gender discrimination (p < 0.001), sexual harassment (p < 0.001), impersonating male colleagues to toughen up, not being treated equally to male colleagues (p < 0.001), and a hostile culture toward females (p < 0.001).

79 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021

Table III: Barriers to pursuing a career in surgery (n = 129) Limited personal time 98 (76%) To spend time with family 83 (64%) For outside interests 70 (54%) To date/marry 19 (15%) To have a child 13 (10%) Surgical workload 92 (71%) Difficulty taking leave of absence 64 (50%) Limited postgraduate training 34 (26%) Verbal discouragement 22 (17%) Discouragement by male colleague 15 (68%) Discouragement by female colleague 7 (32%) Family aspirations 11 (9%) Gender-based 11 (9%) Age 3 (2%) Other 6% Cost of training 11 (9%) Lack of mentors 14 (11%) Other (race/lack of experience/work environment) 10 (8%) Table IV: Challenges of a career in surgery (n = 129) Challenge Difficult work-life balance 74 (57%) Burnout 68 (53%) Negative experience with colleagues 47 (36%) Racial discrimination 29 (23%) Gender discrimination 15 (12%) Physical abuse 15 (12%) Sexual harassment 7 (5%) Impersonating male colleagues to toughen up 11/33 (33%) Not treated equally to male colleagues 15/33 (45%) Hostile culture toward females 9/33 (27%) No challenges 9 (7%) Negative experience with Both 26 (57%) Male colleague 18 (39%) Female colleague 2 (4%) Facilitation of surgical training Mentorship programme 76 (59%) Postgraduate surgical training scholarships 61 (47%) Part-time surgical training programmes 46 (36%) Other (flexible training programmes, appropriate cover of maternity leave, better working hours) 17 (13%)

The 12 candidates (10%) who regretted their career choice did not face more gender discrimination (p = 0.154) or racial discrimination (p = 0.903) than those who did not regret their career choice.

Discussion

Our study highlights that substantial challenges and barriers exist within surgical training in South Africa. Burnout was reported among more than half of the participants. Challenges related to the demanding nature of a surgical career, heavy workloads and long hours, having limited personal time, and the lack of a work-life balance were most commonly reported. These challenges can further be exacerbated by bullying in the surgical environment which has previously been documented and defined as persistent negative behaviour or aggression, and is often experienced more by women.15,16 In our study, 17% of participants were verbally discouraged from pursuing a career in surgery, mostly by male colleagues and 36% of participants reported a negative experience, both of which can be considered as bullying. This form of mistreatment can be mitigated through training focused on professionalism.

In addition to bullying, other forms of discrimination were reported by our participants and can make sustaining a career in surgery difficult. Nearly one-quarter of participants experienced racial discrimination and 12% reported gender discrimination, forms of mistreatment also reported in international literature.15,17 Challenges and barriers were reported by both genders, but some were unique to and more common among females; for example, the need to emulate masculine qualities and a hostile culture toward females. Five per cent of participants experienced sexual harassment, and while this is lower than international literature,15 women reported sexual harassment more than men. Nearly half the female respondents reported gender-based discrimination and not being treated equally to their male colleagues. Additionally, female surgeons found having a child to be more challenging than males. The survey did not capture other forms of discrimination, such as religious or ethnic discrimination. These would be important to explore in more detail in future studies.

Despite these challenges, 90% of participants were satisfied with and did not regret their career choice. This is consistent with findings from previous studies.1,5,18 Some of the reported benefits of a surgical career in our study included job satisfaction, making a difference, and financial stability. While this study did not report the proportion of surgeons who wished to leave surgical practice, previous US-based studies have shown that despite high career satisfaction, one in four surgeons were considering leaving surgery on the basis of work-schedule demands and limited personal time.1

In comparison to a study published in the USA among residents, fewer South African residents reported gender discrimination (31.9% in the US versus 21.7% in our South African study), fewer reported physical, verbal and emotional abuse (30.3% in the US versus 17.4% in our South African study), yet more residents in South Africa reported burnout (60.9%) in comparison to USA residents (38.5%).3 Similarly, in internal medicine, a study conducted by the American College of Physicians reported that 51.3% of female physicians reported gender discrimination, which is higher than that reported among our female cohort.19 In a study evaluating perceptions among residents in obstetrics

and gynaecology, 40.6% of women and 2.9% of men reported gender discrimination, in comparison to our South African study in which 45% of female participants and 0% of male participants experienced gender discrimination.20 The challenges described in this study are not new or unique to South Africa or to the field of surgery; they are a global phenomenon and often disproportionately affect female surgeons.1,5 However, mitigating these challenges and barriers requires context-relevant local solutions. In South Africa, this could necessitate the restructuring of surgical training, including: i) a formalised mentorship programme; ii) programmatic changes that facilitate surgical training, such as scholarship opportunities for postgraduate training and part-time or more flexible work schedules; and iii) specific training in awareness of discrimination and accepting diversity in the discipline, particularly with respect to the mistreatment and challenges experienced by female surgeons.

Mentorship in surgery is gaining traction globally.21 Formalised mentorship programmes have been reported to aid job satisfaction and retention, facilitate career development, increase opportunities to engage in academia with respect to research and education, and improve technical skills and confidence.21,22 The goal of mentorship is to support and guide individuals through career and leadership development. The role of a mentor in career development can be substantial, allowing for expansion of professional network and providing a new personal or clinical perspective. Mentorship could be beneficial with regards to providing advice on how to achieve a work-life balance, or how to deal with or report discrimination. With a shortage of experienced faculty, the advent of online learning platforms and technology has proven to be useful in linking mentors and mentees.23,24 Exemplary role models who encourage diversity and inclusivity are crucial in changing the current hostile culture and biases in surgery. Previous studies have shown that medical students considering a career in surgery are more likely to be influenced by a positive role model than those who do not have such an influence.25 In our study, women were more likely to be inspired by a positive role model to pursue a career in surgery than men. Furthermore, access to career and academic opportunities were important motivators for choosing a career in surgery.26-28 Mentors can play an important role in career development, both in the academic and clinical settings. One-quarter of participants expressed there were limited opportunities for postgraduate training. More than half reported that mentorship programmes would facilitate surgical training. Further studies are required to address the value of mentorship and how this can be leveraged to create a more sustainable, inclusive, and safe environment for surgeons and surgical trainees, especially for women in surgery.

A study in the USA found that male surgeons were significantly less likely to encourage female medical students to pursue a career in surgery.1 In our study, females were more likely to experience verbal discouragement compared to their male colleagues, and this was cited as a barrier to pursuing a surgical career. This overt and implicit discouragement needs to be addressed if we are going to increase diversity and opportunities for minority groups, such as females, in the field of surgery.1,2 In recent years, there has been an increasing number of female medical students, with some medical schools reporting a female majority.29 If we continue to foster an environment that is

80 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021

hostile toward women in surgery, we will perpetuate the shortage of surgeons that currently exists.2,8

Furthermore, our study reported statistically significant differences in the challenges reported by males compared with females. Female participants were more likely to report gender discrimination, sexual harassment, impersonating male colleagues to toughen up, being treated unfairly compared with male colleagues, and a hostile culture towards female surgeons.

Professor Boffard, a world-renowned trauma surgeon and a past president of the International Society of Surgery, has been pioneering the way forward for female surgeons, being one of the first to recognise the need for and to implement part-time surgical training. These flexible work schedules are designed to “make surgery more attractive, particularly to women, who now consist of 60% of all medical graduates but only 5% of surgeons”.29 However, in Johannesburg, more than half the surgeons are female and creating an environment that fosters gender equity is essential.29 More flexible work schedules will not only benefit female surgeons, but male surgeons too. The majority of our participants were male, and the majority reported that the surgical workload was a challenge to sustaining a career in surgery. Furthermore, more than half the participants reported burnout. The Flexibility in Duty Hour Requirements for Surgical Trainees (FIRST) Trial, conducted in the USA, has paved the way for the discussion on flexible work schedules in international literature, reporting that more flexible work schedules can decrease the notoriously high surgical workload, and assist in greater job satisfaction and career retention.30,31

South African surgical training lacks postgraduate programmes, mostly pertaining to fellowship opportunities. One-quarter of participants identified this as a challenge and nearly half reported a need for these programmes to facilitate surgical training. Postgraduate research fellowship grants and scholarships are available but limited, however not nearly as scarce as clinical fellowships.26-28 The ASSA Trust plans to source private funding to support fellowship posts. There is further opportunity to engage corporates, societies, and other organisations to fund postgraduate surgical fellowships, thereby encouraging continued learning in the field of surgery.

While our study focused mostly on gender discrimination, there is an opportunity to incorporate the value of diversity and the meaning of professionalism into formalised training curricula and to create a platform for both trainee and faculty surgeons to express their opinions, concerns, and suggestions about discrimination in the surgical workplace. By building intentional platforms for engagement into training, we will not only create awareness about any form of discrimination, but also help to decrease the biases in surgery. Non-technical skills are becoming increasingly important in surgical training and have been shown to facilitate cultural diversity and improved surgical outcomes.32,33 These existing platforms could be expanded to include training on the value of other types of diversity, including gender, ethnic and racial diversity.

Study limitations

This study was limited by its methodological design. The questionnaire was limiting, providing only quantitative answers. A mixed-methodology study design would have provided even more valuable and substantial information regarding the challenges of and barriers to a surgical career

in South Africa. Additionally, this study was limited by the poor response rate, meaning that results are not necessarily generalisable to the entire South African surgical community. Despite these challenges, this study provides initial insight into the existing barriers to and challenges of a surgical career in South Africa. However, future studies should address the limitations discussed in this study.

Conclusion

This study highlights the numerous barriers to and challenges of surgical career in South Africa. More than half the South African surgeons who participated in this study experienced burnout. While barriers to pursuing and challenges in sustaining a surgical career are reported by both male and female surgeons, some inordinately affect females. Despite these challenges, career satisfaction was reported to be high among the overwhelming majority of surgeons. Encouraging sustainability of a surgical career requires addressing the barriers and challenges that exist. Potential solutions include formalised mentorship programmes, facilitating surgical training through postgraduate funding and flexible work schedules, and integrated training on discrimination and diversity. With increasing interest in medicine among females, the gender profile of medical school and postgraduate surgical training is changing. To address the shortage of surgeons, surgical work environments and training programmes need to adapt to reduce burnout and encourage inclusivity and diversity, especially among females.

Acknowledgement

We extend our gratitude to the steering committee of ASSA who enhanced the survey by their input, the ASSA secretariat for circulating it widely to the target audiences, and to all those who completed the survey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding source

None.

Disclaimer

This survey was initiated by and conducted under the auspices of the Association of Surgeons of South Africa (ASSA).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (protocol number: BREC/00002259/2020).

ORCID

P Naidu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1112-9606

I Buccimazza https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5399-3101

REFERENCES

1. Mahoney S, Strassle P, Schroen AT, et al. Survey of the US surgeon workforce – practice characteristics, job satisfaction, and reasons for leaving surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2020 Mar;230(3):283-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jamcollsurg.2019.12.003

Full list of references available on request.

81 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021

South African Journal of Surgery. 2021;59(3):82-85

https://doi.org/10.17159/2078-5151/2021/v59n3a3597

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0]

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0

©

ISSN 038-2361

Surgery in South Africa – the attitudes toward mentorship in facilitating general surgical training

P Naidu,1 I Buccimazza2

1 Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

2 Department of Surgery, Inkosi Albert Luthuli Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health, South Africa

Corresponding author, email: pnaidu2012@gmail.com

Background: There are many barriers to pursuing a surgical career in South Africa, some of which are unique to females. Mentorship has been proposed as a solution to mitigate these barriers. The value of mentorship has not been formally assessed among South African general surgeons and trainees.

Methods: The study was part of a larger study designed to assess barriers to pursuing a career in surgery, including the value of mentorship. A 15-item questionnaire was designed and distributed via the Research Electronic Database Capture from 1 February 2020–3 April 2020. Data were analysed using Stata 15 SE. All responses were anonymised.

Results: One hundred and twenty-nine (13.5%) of 955 potential participants responded to the survey of which 26% (33/129) were female. Sixty-seven per cent of respondents were specialist surgeons (87/129). Seventy per cent (90/129) of participants reported having a role model in surgery, however, 66% (86/129) reported they had no mentor in surgery. 107/129 (83%) participants reported the importance of mentorship. The need for a formalised mentorship programme to facilitate surgical training was recorded by 60% (78/129) of participants, while 18% (23/129) reported the need for a mentorship group specifically for females.

Conclusion: Eighty-three per cent of participants reported the importance of mentorship however two-thirds lacked a mentor. Most participants advocated for a mentorship group to facilitate surgical training. Establishing formalised mentorship programmes could mitigate the barriers to pursuing a surgical career.

Keywords: surgery, training, barriers, mentorship

Appendix 1 available online: http://sajs.redbricklibrary.com/index.php/sajs/article/view/3597

Introduction

Surgery is a highly competitive specialty and a particularly challenging learning environment.1 Barriers to pursuing a career in surgery include heavy workload, poor worklife balance, verbal discouragement, and limited options for postgraduate surgical training. These barriers can lead to low interest to pursue a surgical career choice. Challenges identified in the surgical workplace include, among others, verbal, physical and emotional abuse, long working hours, and lack of time for commitments outside of surgery.1,2 Challenges in the surgical workplace have led to burnout, physical and emotional exhaustion, and even attrition of surgeons. Some of these challenges are unique to female surgeons, such as limited time to plan a family and gender discrimination in the workplace.3 There is an increasing number of female doctors in medicine, yet a disproportionately low number of women in surgery. In South Africa, 60% of medical students are female, however, only five per cent are surgeons.4 The under-representation of women in surgery is evident at all levels including in academic and leadership positions.5,6

Mentorship has been gaining traction in the field of surgery and can be an important way to mitigate challenges

of and barriers to pursuing a surgical career. Mentorship has been defined as a “two-way relationship and type of human development in which one individual invests personal knowledge, energy and time in order to help another individual grow and develop and improve to become the best and most successful they can be.”7 Mentors can be important facilitators of the entrance of young doctors, particularly female doctors, into the field of surgery.8 Mentors can also play an important role in a mentee’s career satisfaction and development, particularly in academia, and aid in the retention of surgeons.9

While evaluation of mentorship in surgery has been increasingly reported in the literature from high-income countries, such as the United States, there is a paucity of literature on the value or perceptions of mentorship in lowand middle-income settings, such as South Africa.1,9

The primary objective of this survey was to determine the value of mentorship among South African general surgeons. The secondary objectives of this study were to determine the proportion of participants that felt a formalised mentorship programme for surgical trainees in general and women in particular was needed.

82 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021 South African Journal of Surgery

2021 The Author(s) GENERAL SURGERY SURVEY

Methods

This was a cross-sectional survey conducted using a 15item questionnaire (Appendix 1) which was designed and distributed via the Research Electronic Database Capture (REDCap) software (version 8.1.13, Vanderbilt University). The survey was developed by both authors, the senior author being a surgical sub-specialist, and included questions on challenges and barriers to pursuing a career in surgery, as well as the attitudes and perceptions of mentorship in facilitating surgical training. These questions were adapted from previously published studies.1-3,9 Questions on the value of mentorship were single-answer choice questions except for the question on methods to facilitate surgical training, where participants were allowed to select multiple answers. The questions on the value of mentorship were analysed using Stata 15 SE. The survey was circulated to qualified general surgeons who are members of the Association of Surgeons South Africa (ASSA) or Surgicom, as well as to general surgical trainees through their heads of department. The survey was conducted over a two-month period from 1 February 2020 to 3 April 2020. All responses were anonymous, and no identifying data were included. Descriptive analysis of the data was performed using measures of dispersion (means and median).

Results

One hundred and twenty-nine (13.5%) out of 955 general surgeons and trainees approached to participate, responded to the survey. Seventy-four per cent (96/129) were male and 47% (60/129) were older than 50 years of age (Table I). Sixty-seven per cent (87/129) of participants were consultant surgeons with a median of 18 years (IQR 10–28) post-fellowship experience. Twenty-three (18%) of the participants were registrars in surgical training and the median number of years in training was two years (IQR 1–3).

Fifty-three per cent of participants (69/129) reported having a role model in their lives and 70% (90/129) reported the presence of a role model in surgery (Table II). This role

model in surgery was a senior colleague in 60% (78/129) of cases.

Fifty-four per cent (70/129) did not have a mentor; of these 61% (43/70) felt they lacked mentorship and would have liked to have had a mentor for their career development. Eighty-four per cent (36/43) of the mentees had a male mentor and 68% (29/43) had two or more mentors. Fortyfour per cent (57/129) reported having a mentee with 56% (32/57) having both male and female mentees.

Eighty-three per cent of the participants (107/129) reported that they felt it was important to have a mentor (Table III).

83 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021

Characteristics Gender n = 129 Male 96 (74%) Female 33 (26%) Age n = 129 20–29 8 (6%) 30–39 36 (28%) 40–49 25 (19%) > 50 60 (47%) Position n = 129 Consultant 87 (67%) Fellow 8 (6%) Medical officer in surgery 5 (4%) Registrar 23 (18%) Unspecified 6 (5%) Median number of years post-fellowship (IQR) 18 (10–28) Median years in registrar training (IQR) 2 (1–3)

Table I: Demographic characteristics

Male (n = 96) Female (n = 33) n = 129 Presence of a role model in life Yes 55 14 69 (53%) No 31 13 44 (34%) No response 10 6 16 (13%) Presence of role model in surgery Yes 65 25 90 (70%) No 21 2 23 (18%) No response 10 6 16 (12%) Who is your role model Senior colleague 62 16 78 (60%) Other (family member/none) 18 5 23 (18%) Peer 6 6 12 (9%) No response 10 6 16 (13%) Presence of a mentor Yes 28 15 43 (33%) No 58 12 70 (54%) No response 10 6 16 (12%) Gender of mentor n = 43 Male 26 10 36 (84%) Female 0 2 2 (5%) Both 2 3 5 (12%) Number of mentors per respondent n = 43 1 11 3 14 (32%) 2 9 8 17 (40%) 3 or more 8 4 12 (28%) Presence of a mentee n = 129 Yes 42 15 57 (44%) No 44 12 56 (43%) No response 10 6 16 (13%) Gender of mentee n = 57 Male 16 3 19 (33%) Female 2 4 6 (11%) Both 24 8 32 (56%)

Table II: Presence of role models and mentors

Table III: The value of mentorship as reported by participants

differences.8 While mentorship has often been regarded as a casual relationship, recent literature argues that mentorship should be cultivated in surgical programmes as this is an important method of teaching both technical and nontechnical skills.8,12 Formalised mentorship programmes are becoming increasingly important globally for their ability to address mentor time constraints, increase confidence and interest in surgical careers among medical students,13 and increase satisfaction of the mentorship environment among surgical trainees.11 A recent study in the United Kingdom reported that 83% of participants (surgeons in various surgical specialties) were willing to undergo formal mentorship training to increase the number of qualified mentors and improve effective mentorship.14 However, formalised mentorship programmes require involvement of the surgical department and the academic institution to ensure success.9

Numerous organisations, including the College of Surgeons of East, Central, and Southern Africa, have established formalised mentorship groups specifically for female surgeons in all specialties.15 These dedicated groups for women in surgery have helped to improve retention of female surgeons in the field by increasing academic and leadership opportunities and providing support for challenges that are unique to female surgeons.15,16 A 2017 study reported that same-sex mentorship was preferred among females and could positively influence career choice and address barriers to pursuing surgery, advocating for the development of national mentorship programmes in the United States.17 Our study showed that 45% of female participants had a mentor, and an overwhelming majority (84%) of mentors were male, which could be explained by the male-dominated nature of surgery in South Africa but also suggests a lack of female mentors.

The need for a formal mentorship group for all surgeons was recommended by 60% (78/129) of the participants, whereas 18% (23/129) reported the need for a group to specifically support female surgeons; 16 out of the 23 (70%) respondents were female.

Discussion

Our survey shows that South African general surgeons and trainees perceive the need for mentorship in surgery. Eightythree per cent of participants regarded the presence of a mentor as important, yet two-thirds did not have a mentor in surgery. Sixty per cent of participants reported that a mentorship programme would facilitate surgical training and a similar amount further reported the need for a formalised mentorship group for all surgeons.

Mentors can play a role in aiding retention of surgeons and increasing career satisfaction by creating a supportive environment that cultivates learning, advice on how to mitigate stress and decrease barriers to pursuing surgical careers, particularly for female doctors.10 Surgical trainees in orthopaedics who had mentors reported significantly higher job satisfaction and career development than those without mentors.11 There are several barriers to effective mentorship which include time constraints, generational and cultural differences, scarcity of qualified mentors and gender

Nearly two-thirds of participants in the current study reported the need for a mentorship group for all surgeons and 70% of female respondents reported the need for a dedicated group to support female surgeons. Despite this, there is no published data as to whether South African academic institutions have formal mentorship programmes in general or for females specifically and if they are effective. Even in institutions that have established these programmes, there is no data on their effectiveness. We believe it should be a priority to establish formalised mentorship programmes in surgical training programmes whilst at the same time devising metrics to assess their value.

It is recognised that there are several inherent limitations and challenges associated with surveys. There was a relatively low response rate, and the study sample was not representative of all regions and academic institutions in South Africa despite constant communication and reminders to encourage survey completion. Being embedded in a larger questionnaire meant that for simplicity of completion mostly single-answer responses were used. As a result, we were unable to do a more qualitative assessment of some responses; for example, reasons why respondents felt it is important to have a mentor or what aspects the respondents felt they lacked in their training that could be improved by being mentored.

Despite these limitations, over 80% of the South African general surgeons and surgical trainees who participated in

84 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021

Conclusion

Male Female Total Important to have a mentor? n = 129 Yes 82 25 107 (83%) No 3 2 5 (4%) Missing 11 6 17 (13%) Perceived lack of mentorship (if no mentor) n = 70 Yes 30 13 43 (61%) No 14 13 27 (39%) Facilitation of surgical training n = 129 Mentorship programme 57 19 76 (59%) Postgraduate surgical training scholarships 50 11 61 (47%) Part-time surgical training programmes 36 10 46 (36%) Other (flexible training programmes, appropriate cover of maternity leave, part-time post graduate training, better working hours) 15 2 17 (13%) Is there a need for a mentorship group for all surgeons? n = 129 Yes 56 22 78 (60%) No 6 4 10 (8%) Unsure 34 7 41 (32%) Is there a need for a group to support female surgeons? n = 129 Yes 7 16 23 (18%) No 20 7 27 (21%) Unsure 50 3 53 (41%) Missing 18 8 26 (20%)

the study valued mentorship and 60% felt there was a need for a formal mentorship programme to facilitate surgical training.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding source

No funding was required.

Disclaimer

This survey was initiated by and conducted under the auspices of the Association of Surgeons of South Africa (ASSA).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (protocol number: BREC/00002259/2020).

ORCID

P Naidu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1112-9606

I Buccimazza https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5399-3101

REFERENCES

1. Mahoney ST, Strassle PD, Schroen AT, et al. Survey of the US surgeon workforce – practice characteristics, job satisfaction, and reasons for leaving surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230(3):283-93.e1.

2. Hu Y-Y, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741-52.

3. Roodt L. Female general surgeons – current status, perceptions and challenges in South Africa. A pilot study at a single academic complex. University of Cape Town; 2016.

4. Boffard K. SA trauma expert to head world body. S Afr Med J. 2010;100:144-5.

5. Cochran A, Elder WB, Crandall M, et al. Barriers to advancement in academic surgery – views of senior residents and early career faculty. Am J Surg. 2013;206(5):661-6.

6. Cochran A, Hauschild T, Elder WB, et al. Perceived genderbased barriers to careers in academic surgery. Am J Surg. 2013;206(2):263-8.

7. Flaherty J. Coaching – evoking excellence in others. 2nd ed. Development and Learning in Organizations. Taylor & Francis Ltd; 2006.

8. Entezami P, Franzblau LE, Chung KC. Mentorship in surgical training – a systematic review. Hand. 2012;7(1):30-6.

9. Kibbe MR, Pellegrini CA, Townsend CM, Helenowski IB, Patti MG. Characterisation of mentorship programmes in departments of surgery in the United States. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(10):900-6.

10. Welch JL, Jimenez HL, Walthall J, Allen SE. The women in emergency medicine mentoring programme – an innovative approach to mentoring. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):362.

11. Flint JH, Jahangir AA, Browner BD, Mehta S. The value of mentorship in orthopaedic surgery resident education – the residents’ perspective. JBJS. 2009;91(4):1017-22.

12. Holt GR. Idealised mentoring and role modeling in facial plastic and reconstructive surgery training. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2008;10(6):421-6.

13. Drolet BC, Sangisetty S, Mulvaney PM, Ryder BA, Cioffi WG. A mentorship-based preclinical elective increases exposure, confidence, and interest in surgery. Am J Surg. 2014;207(2):179-86.

14. Sinclair P, Fitzgerald J, Hornby S, Shalhoub J. Mentorship in surgical training – current status and a needs assessment for future mentoring programmes in surgery. World J Surg. 2015;39(2):303-13.

15. McCarthy MC. The Association of Women Surgeons – a historical perspective 1981 to 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128(6):633-6.

16. Odera A, Tierney S, Mangaoang D, Mugwe R, Sanfey H. Women in surgery Africa and research. Lancet. 2019;393(10186):2120.

17. Faucett EA, McCrary HC, Milinic T, et al. The role of samesex mentorship and organisational support in encouraging women to pursue surgery. Am J Surg. 2017;214(4):640-4.

85 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021

https://doi.org/10.17159/2078-5151/2021/v59n3a3463

Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0]

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0

ISSN 038-2361

Surgical rib fixation as an alternative method of treatment for multiple rib fractures: an audit of results compared with traditional medical management

BI Monzon,1 LM Fingleson,2 MS Moeng3

1 Trauma Unit, Steve Biko Academic Hospital, University of Pretoria, South Africa

2 Sunninghill Hospital Acute Care and Major Injuries Unit, South Africa

3 Trauma Unit, Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

Corresponding author, email: bignaciomonzon@gmail.com

Background: Rib fractures are a common cause of morbidity and chronic pain, delaying return to normal activities. Reports suggest that surgical fixation improves acute and long-term outcomes.

Method: A single centre retrospective review of multiple rib fractures, comparing the outcomes of cases managed using surgical fixation with cases managed only with best medical therapy (BMT) over 2 years.

Results: Thirty-five patients with rib fractures were admitted over the study period. The most common causes of rib fractures were motorcycle crashes (34.2%) and falls (31.4%). Fourteen patients had surgery. There were no differences between the two groups regarding the number of fractured ribs, injury severity score (ISS), ICU or hospital length of stay. The median numeric pain visual analogue scale (VAS) on admission was eight points for non-ventilated patients. In the surgical group the median VAS significantly fell to a median of 2 points in the first 24 hours after surgery (p = 0.04). Only two out of 25 major complications were directly attributable to the surgery for rib fixation. Patients managed without surgery needed significantly longer time to return to normal activities compared to those who had surgery (median 7 weeks versus 3 weeks, p = 0.03).

Conclusions: Our preliminary results suggest that rib fixation should be considered a treatment alternative in patients with multiple rib fractures.

Keywords: rib fractures, surgical fixation, flail chest, trauma

Introduction

Rib fractures are common and causations are multifactorial; they are a recognised marker for severity of injury and a significant cause of in-hospital morbidity, chronic pain, and delays in return to normal activities.1-3 The number of ribs fractured, presence of flail segment, patient age, associated lung trauma and extra thoracic injuries, especially traumatic brain injury are predictors of outcome.1-10

The current standard of care for rib fractures is nonoperative and is based on several key components. These include appropriate oxygenation, management of respiratory failure with mechanical ventilation, lung re-expansion techniques, appropriate management of pain, removal of secretions and aggressive chest physiotherapy.1-10

Unfortunately, non-operative management addresses only the pathophysiological component of this problem, while the mechanical and anatomical problems (actual fractures) are usually overlooked and treated with options that are not designed to facilitate bone consolidation.

The impact of rib fractures on prolonged disability is usually greater than traditionally expected; chronic pain is considered to be present in 22% of cases (could be as high as

59%) and some form of disability in 53% of cases 6 months after injury.10-22

Attempts to provide rigidity to the chest wall in the event of fractures is not a new proposition, multiple techniques have been used along the years to achieve stability with variable success.

Efforts to advance the surgical fixation of flail chest and multiple rib fractures to the level of standard of care have not met the expectations or received the approval of many surgeons, mostly due to lack of appropriate evidence and familiarity with the procedures.11

Evidence in favour of surgical stabilisation of rib fractures has been limited by the quality of the studies as with other trauma related issues,11-20 however, the accumulated evidence both from randomised clinical trials and from the systematic reviews and metanalysis consistently favours rib fixation over medical management.1,12-26

This mounting experience points to significant advantages such as the reduced incidence of pneumonia and respiratory failure, shorter ventilation time, shorter ICU and hospital stay with minimal complications as well as faster return to productive life, all of which result in improved quality adjusted life-years and costs.1,12-26

86 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021 South African Journal of Surgery

© 2021 The Author(s) TRAUMA

Journal

South African

of Surgery. 2021;59(3):86-89

At our institution, all patients with rib fractures were admitted to a trauma ICU ward and offered the standard of care as per protocol of the unit, including intravenous analgesia; oxygen, nebulised bronchodilators as needed, mechanical ventilation when indicated, management of associated injuries and active physiotherapy. A computed tomography scan (CT) of the chest was obtained and three-dimensional (3-D) volume reconstructions performed to evaluate the thoracic skeleton and assess indication for surgery.

As per unit protocol, a follow-up visit was scheduled at two weeks interval after discharge in all cases to clinically assess pain level, physical and pulmonary functionality and obtain chest radiographies to exclude residual pulmonary problems and in the surgical cases to evaluate the fracture site and implant complications. Once the patients re-incorporated to normal activities, they were considered discharged and advised to return for consultation if a problem or concern arose.

Only patients who have three or more rib fractures, or a flail chest with severe pain, as assessed by numeric visual analogue scale (VAS) higher than 6 points, fracture displacement, pulmonary contusion or inability to tolerate physiotherapy are considered for fixation at our institution.

The aim of study was to compare outcomes between subjects with multiple ribs fractures who received surgical rib fixation, and those who only received best medical therapy (BMT).

Method

Retrospective study from 1 July 2015 to 31 August 2017 (a 25-month period).

Inclusion criteria

All trauma patients presenting with multiple fractured ribs at a level 2 private trauma centre in Johannesburg.

Exclusion criteria

Subjects < 18 years of age, incomplete clinical data, associated severe traumatic brain injury (GCS < 8), major spinal injuries, those with predominantly posterior fractures not amenable to surgical options, and those who have mild symptoms and are able to participate fully in physiotherapy care.

Data collected

The following information was extracted from clinical notes and entered on a Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA): Demographic data (age and sex), mechanism of injury, patterns and number of rib fractures, associated injuries noted, physiological factors (revised trauma score, injury severity score, new injury severity score, probability of survival), medical treatment offered, surgical treatment offered, time to surgery, ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, in-hospital mortality, procedure related complications, time to return to work or normal activities, pain assessment on admission, after surgery and during outpatient review, and radiological findings during outpatient review.

The surgical procedure to fix the ribs was performed using a muscle sparing thoracic incision (Figure 1). The ribs were stabilised using titanium plates and screws (RibFix BluTM, Zimmer Biomet, Jacksonville, USA); an effort was always made to provide stability for all accessible fractures.

Fractures in ribs one, two, three, ten, eleven and twelve or fractures less than 3 cm from the costo-vertebral or sternocostal joints were not fixed. The flail segments were either bridged with a long plate spanning the two fractures or using two individual plates.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the data. Statistical difference between comparable groups was assessed using Student’s t-test for continuous variables, p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, 35 patients were admitted with a diagnosis of rib fractures alone or as part of polytrauma. The patients were mostly males with a median age of 44 years (range 16–68) (Table I).

The most common causes for rib fractures in our series were motorcycle crashes (34.2%) and falls (31.4%), closely followed by motor vehicle collisions. More than

87 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021

Figure 1: A typical example of multiple rib fractures and three plated fractures

sixty per cent of the cases were considered severe trauma (ISS > 16), the median ISS was 21 (4–75). For the patients treated with BMT, the median ISS was 24 (4–75) versus ISS 21 (16–75) for those offered surgery (Table 2).

There was no major difference regarding affected side (15 right – 19 left), and only one patient had bilateral fractures.

Seventy-seven per cent (77.1%) of the patients had three or more fractures (median 6; range 3–7) including nine flail chests (25.7%). The most common associated injuries were pulmonary contusion in 27 cases (77.1%), followed by haemopneumothorax in 24 cases (68.5%). Other associated injuries included clavicular fracture, upper and lower limb fractures, ruptured spleen and mild TBI, among others.

Numeric visual pain scale (VAS) assessments were administered to all conscious patients; overall the median VAS pain on admission for non-ventilated patients was 8 points (range 6–10), operated patients who were not ventilated demonstrated significant immediate postoperative reduction of the pain scales to a median of 2 out of 10 (range 1–4) (Figure 2).

Twelve of the fourteen patients (85.7%) had the surgery performed in the first seven days following injury (median 4 days, range 2–14).

Twenty-five major complications were recorded, 13 in the surgery group and 12 in the BMT group. The most common complication was pneumonia in 23% of cases (4 in each group); other complications included cardiovascular failure, severe sepsis and acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy. Complications related to the ORIF procedure were recorded in only 2 of 14 patients operated (Table 3).

ICU and hospital stay were similar for patients operated or managed with BMT (6.5 and 8.5 days, respectively). The median time to return to normal productive life was 3 weeks for the surgical patients (ranging between 2–16 weeks) versus 7 weeks for the BMT group (range 3–52 weeks) (Table 4).

Discussion

The idea of stabilising fractured ribs to reduce pain, complications and facilitate healing is not new. In 1926, Jones3 first described the application of traction to the sternum to treat flail chest. Others soon followed with a myriad of different methods including traction, direct wiring of ribs and metal implants, unfortunately, surgical stabilisation did not become the standard of care, as mechanical ventilation was considered satisfactory for the treatment of the associated pulmonary contusion and to provide stability to the chest wall.3,5,6

Over the years, multiple publications have demonstrated a clear reduction in the need for opioid analgesia, incidence of pneumonia, shorter ventilation times and ICU stay and generally, a better outcome when surgery was offered over BMT.1,2,5,6,10,12-30 Unfortunately, in South Africa, not all patients have access to all of the BMT strategies, including options in advanced pain management.

Our series showed similar results between the two groups regarding ISS, number of fractures, pain VAS on admission, ICU and hospital length of stay and complications; the

88 SAJS VOL. 59 NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 2021

Surgery Best medical Pneumonia 4 4 Cardiovascular failure 1 2 Severe sepsis 2 1 Acute kidney injury (RRT) 1 2 Retained haemothorax 1 1 Chest wound seroma/hematoma 2Other 2 2 Total 13 12 (*) Some patients had

RRT

renal replacement therapy

IV: Time to return to normal activities Weeks Surgery Best medical 3 or less 8 4 to 6 3 10 7 or more 3 11 Average 5.3 9.3 Median (Range) 3 (2–18)* 7 (4–36) (*) Student’s t-test p = 0.003 p = 0.04* 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Pain VAS Medical Surgical Post op

(*) Student’s t-test

2:

(VAS)

Table III: Complications (*)

more than one complication recorded

–

Table

Case by case pain VAS

Figure

Pain: numeric visual analogue scales

Gender Surgery Best medical Females 4 7 Males 10 14 Median age (Range) 43.5 years (34–68) 45 years (16–68) Table II: Injury severity score (ISS) Severity of injury (ISS) All Surgery Best medical Moderate (1–15) 2 2 Severe (16–25) 21 10 11 Very severe (26–40) 5 1 4 Critical (41–75) 7 3 4 Median (Range) 21 (4–75) 21 (16–75) 24 (4–75) (p > 0.05)

Table I: Demographic information

main difference observed was the time necessary to return to normal activities (median 7 weeks for medical therapy versus 3 weeks for surgical cases [p = 0.03]) and an obvious reduction of pain VAS in the postoperative period (p = 0.04).

Despite the clear advantage of mechanical ventilation to treat the respiratory failure associated with multiple rib fractures, the use of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) does not achieve complete stability of the thoracic skeleton, which impacts the consolidation of the fracture site. Adequate analgesia, chest physiotherapy and early skeletal (rib) fixation seems to prevent complications, as stated in several recent studies.1,2,13,15-17,19,21

Study limitations

A single centre study with a small sample size having potential selection bias and lack of power. The retrospective nature opens it up to the usual limitations of such studies. The pain VAS is subjective and results may not be accurate.