Inhabiting according to the context

Issue 02 | 2024

the best of the MCH 2023 edition...

#untagged presents a selection of the best works produced by students in the Master of Collective Housing – MCH 2023 edition.

The knowledge produced in the MCH through the projects in its Workshops and Specialty courses is at the forefront of the body of thought related to collective housing architecture.

The teachers, juries and guest lecturers are amongst the most recognized in the field, contributing to the quality of the discussions and production made during the one year master.

This first issue lays out the structure for the following numbers, opening up on display the entire year and its contents.

https://www.mchmaster.com/

MCH Directors 2023

José Ma de Lapuerta - UPM

Andrea Deplazes - ETH

MCH Manager 2023

Nuria Muruais

Edited by Camilo Meneses Andrés Solano Cover image by Santiago Aguirre Reinterpretation of A. Deplazes workshop

ISBN 978-84-09-62269-6

© 2024 Master in Collective Housing. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. ETH Zurich.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

MCH Directors

José María de Lapuerta - UPM

Elli Mosayebi - ETH

MCH Manager 2023

Nuria Muruais

Edition and design

Camilo Meneses

Andrés Solano

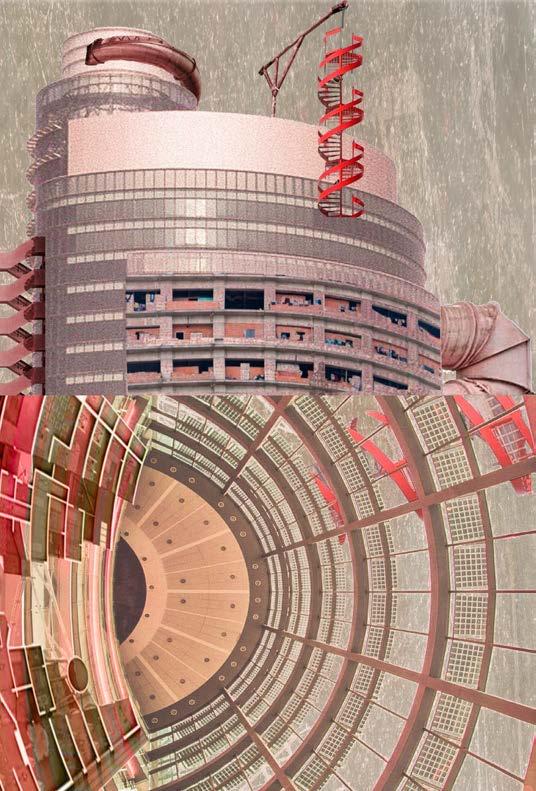

Cover image by Santiago Aguirre from the final booklet MCH, Andrea Deplazes Workshop final submission

Printed and bound by Estugraf

Sp_01 Climate, Metabolism and Architecture

Sp_02 Housing Practice

Sp_03 Sociology, Economy and Politics

Sp_04 Construction and Technology

Sp_05 Leadership, Processes and Entrepreunerurship

Sp_06 Low Resources and Emergency Housing

Sp_07 Urban Design and City Science

ZÜRICH

WORKSHOPS

W_01 Hrvoje Njiric / Housing the Unpredictable

W_02 Andrea Deplazes / Working+Living

W_03 Juan Herreros / Residential Productive Towers

W_04 Elli Mosayebi / Domestic Fragments W_06 Joan Roig / Merging City and

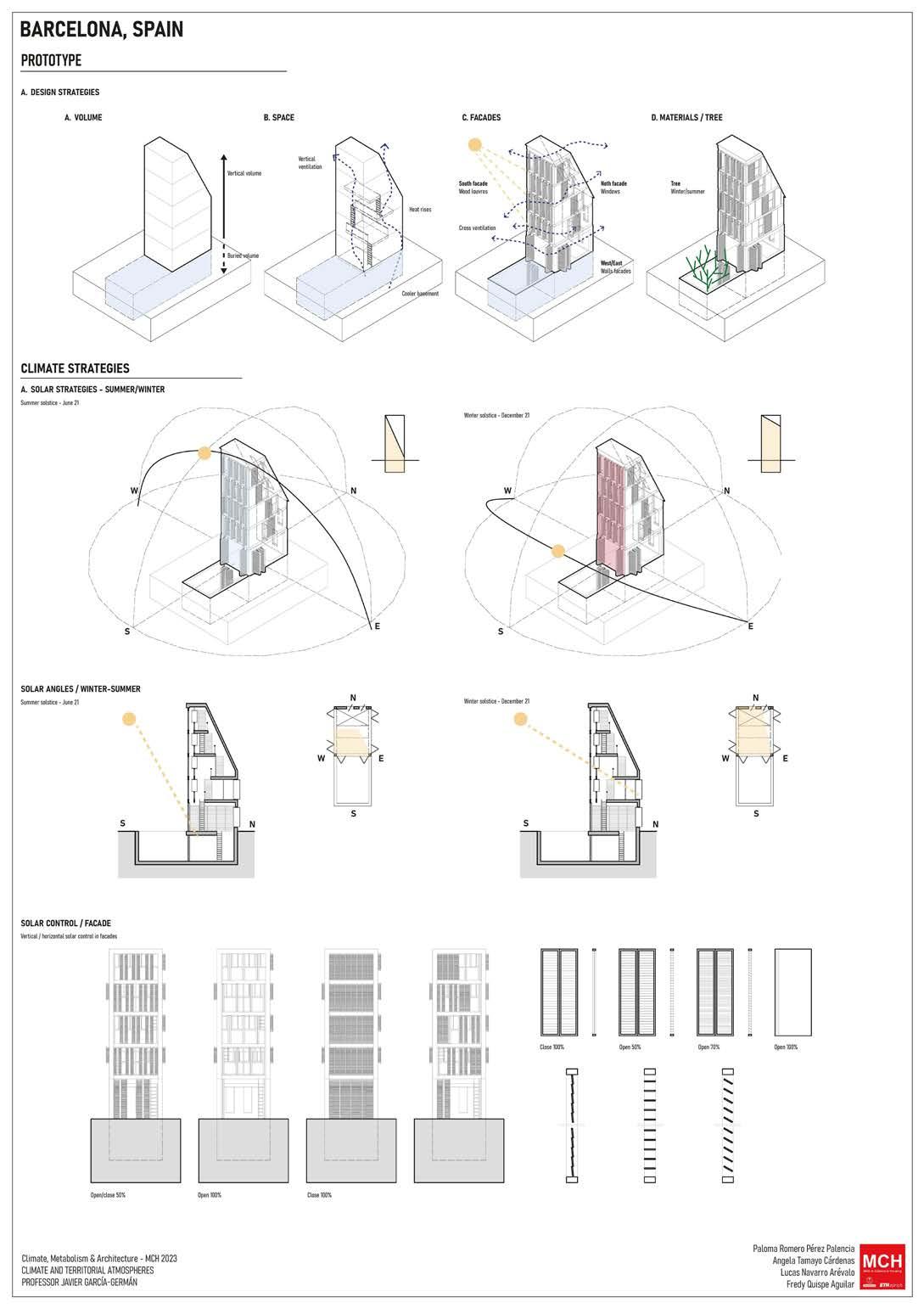

01_ Body, Climate and Architecture / Lucas Navarro, Fedy Quispe, Paloma Romero, Ángela Tamayo

02_ Living in the Nature / William Castro, Nestor Lenarduzzi, Camilo Meneses, Jeronimo Nazur, Brittany Siegert

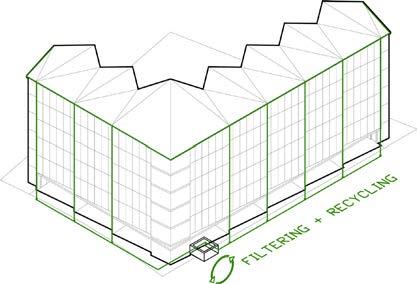

03_ Compactness Ratio in Buildings / Nestor Lenarduzzi

04_ Puerta del Ángel, Madrid / Isabel Monsalve, Vyoma Popat, Brittnay Siegert, Ángela Tamayo

05_ Segragation and Speculation of the Land (de)regulation in Mexican cities / Fernando González 06_ Spare parts for the Jaguar: Alternatives To The Housing Crisis In Chile / Camilo Meneses

07_ From Germany to Colombia / Fernando González, Lucas Navarro, Brittany Siegert, Alejandro Yañez.

08_ From France to Japan / Andrés Melo, Camilo Meneses, Fredy Quispe, Stephany Pavón.

09_ How to manage Progressive Housing / Camila Cano, Camilo Meneses, Paloma Romero, Samira Taubmann

10_ KYAKA II / Camila Cano, Jerónimo Nazur, Andrés Padilla, Stephany Pavón, Brittany Siegert, Angela Tamayo.

11_ Renaturing Campamento / Fredy Quispe, Andrés Padilla, Stephany Pavón, Samira Taubmann.

02_ Humanizing MNN / Gabriel Barba, Fernando González, Isabel Monsalve, Brittany Siegert, Alejandro Yañez.

Visiting Zürich - Basel

Elli Mosayebi interview / Andrés Solano

13_ Be Ready: Rethinking the emergency in Chile / Santiago Aguirre, Camilo Meneses, Isabel Monsalve.

14_ Hurricane Band-AID / Stephany Pavón, Brittany Siegert, Samira Taubmann, Krishna Yadav.

15_ The Trival Code / Hector Herrera, Paloma Romero, Alejandro Yañez.

16_ Inception: Living inside working / Camilo Meneses, Lucas Navarro.

17_ Arround a tree: Here, there, above and below / Santiago Aguirre, William Castro.

18_ Visionexus: The future of desing / Hector Herrera, Fredy Quispe, Ángela Tamayo.

19_ Living with the industry / Nestor Lenarduzzi, Stephany Pavón, Paloma Romero.

20_ Accomoding Guest - Collecting - Armchairs / Santiago Aguirre, Lucas Navarro, Stephany Pavón.

21_ Taking Care of Someone - Thinking - Bay Window / William Castro, Andrés Melo, Ángela Tamayo.

22_ Keeping Tradition Alive - Search for no Wifi - Balcony / Camila Cano, Isabel Monsalve, Fredy Quispe, Brittany Siegert

23_ Community in Campamento, Madrid / Andrés Melo, Fredy Quispe, Paloma Romero.

24_ A New Center in Campamento / William Castro, Fernando González, Stephany Pavón, Vyoma Popat.

25_ Small Scale / Krishna Yadav.

26_ Small Scale / Fernando González.

27_ Medium Scale / Fredy Quispe.

28_ Large Scale / Jeronimo Nazur.

29_ 2 Worlds and the inbetween / Santiago Aguirre, William Castro, Ángela Tamayo, Vyoma Popat.

30_ [Re] Building Community / Nestor Lenarduzzi, Jeronimo Nazur, Samira Taubmann.

_ Alumni Work Selection / Victor Ebergenyi (MCH’11).

_ Alumni Interview / Carlos Chauca (MCH’18), Fernando (MCH’06) Nieto, Álvaro Pedrayes (MCH’20), Tanvi Shah (MCH’21).

EDITOR’S NOTES

Inhabiting according to the context

Camilo Meneses

#Untagged Editor

The MCH is a diverse and compressed program that explores multiple approaches to housing projects from complex perspectives: climate, urbanism, landscape, sustainability, construction, sociology, real state, emergency, crisis, needs, future projections, ideals, among others; always understanding its collective role, for and with society, designing from the craft of detailing to urban presence and interaction with its neighbors.

Inhabiting according to the context is the name of the 2nd edition of #Untagged, compilation of the 2023, 15th edition of MCH that teaches us how our decisions impact others, as well as the context influences our design, being this correlation a fundamental part to understand the resolution of the current housing crisis.

Regardless of the scale or starting point, all projects are inserted and are part of the territory, transforming and integrating on it. The value of this interaction establishes communities beyond the individual vision, being the key that governs us as a society: coexistence.

In only 7 months, 22 students produce more than 100 architectural projects to multiple commissions in their 8 specialties and 7 workshop classes. This magazine presents 30 of the most outstanding projects, architectural visions on collective housing and its possible solutions, always from the collaborative perspective of teamwork between professionals, of different ages and multiple countries.

The ability to have a positive impact will always depend on what surrounds us. Being aware of seeing beyond the architectural ego or the individual professional search, understanding the role of service and responsibility that implies the design of spaces for living.

... that is MCH, that is #UNTAGGED.

DE LAPUERTA MCH DIRECTOR

About:

The nature of practice in architecture.

José María De Lapuerta MCH DirectorThe design of the Master’s program in Collective Housing UPM-ETH, at the beginning of this century, started from a conviction: Housing is a social modifier that affects ALL aspects of society.

This amplifies the importance of collective housing although, to go deeper into it, we no longer have to talk only about housing. We are talking about the fact that it will influence the thermodynamic bill, the integration of immigrants and many other groups, the economy, the care of the elderly and children, even the decrease of the vulnerability index of this society.

This is the program of a Master’s, in which “learning by doing” exemplifies our aspirations. We are immensely fortunate that there are no excuses for possible weaknesses in the program. We can have the best faculty and students in the world and we have an obligation to look closely at society to realize the changes in the areas we can influence.

“From architecture to high density housing to the city”

Every exercise, whether it is a design or theoretical project, needs tangible variables, elements that support our point of view and that frame what we do and what we do not do, since both the project and the research are linked by the elements that allow us to understand, represent and transmit it.

We know where the architects who have studied in the different editions of the MCH are. They are improving aspects that society demands from us in the 5 continents and from very different responsibilities. Some of them very important.

Let #UNTAGGED be the testimony of what we believe MCH is and hopes to be.

SPECIALTIES MCH_ 2023

01_ CLIMATE, METABOLISM AND ARCHITECTURE

JAVIER GARCÍA-GÉRMÁN.

SILVIA BENEDITO, DANIEL IBAÑEZ, ALVARO CATALÁN DE OCÓN, EMILIANO LOPEZ, FLEXO ARQUITECTURA, TAKK ARQUITECTOS, ROGER BOLTSHAUSER, RENATA SENTKIEWICZ.

02_ HOUSING PRACTICE

FERNANDO ALTOZANO.

JAVIER ARMA, ENRIQUE ARENAS, BALPARDA BRUNEL ARQUITECTOS, PATRICK GMÜR, PALAFITO ARQUITECTURA, ANDRÉS SOLANO.

03_ SOCIOLOGY, ECONOMIC AND POLITICS

DANIEL SORANDO.

IRENE LEBRUSÁN, MELISSA GARCÍA LAMARCA, SONIA ALBACI, JAVIER GIL, ANTONIO LÓPEZ GAY, EDUARDO GONZÁLEZ, GAIA REDAELLI.

04_ CONSTRUCTION AND TECHNOLOGY

IGNACIO FENÁNDEZ SOLLA.

DIEGO GARCÍA-SETIÉN, ARCHIE CAMPBELL, DIEGO CASTRO.

05_ LEADERSHIP, PROCESSES AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP

SACHA MENZ.

AXEL PAULUS, AEDAS HOME, RAFAEL DE LA HOZ.

06_ LOW RESOURCES AND EMERGENCY HOUSING

ELENA GIRAL.

GIULIA CELENTANO, KHALDA EL JACK, JEROEN STEVENS, N’UNDO

07_ URBAN DESIGN AND CITY SCIENCE

JOSÉ MARÍA EZQUIAGA.

GEMMA PERIBAÑEZ, JULIA LANDABURU, SUSANA ISABEL, CARLOS MORENO, JAVIER MALO DE MOLINA, FLAVIO TEJADA, BELINDA TATO, JAVIER DORAO, MARIOLA MERINO.

08_ HYBRID TECHNIQUES FOR ARCHITECTURE DESIGN

FELIPE SANTAMARÍA.

CLIMATE METABOLISM AND ARCHITECTURE

CLIMATE METABOLISM AND ARCHITECTURE

Javier García-GermánSpecialty Leader

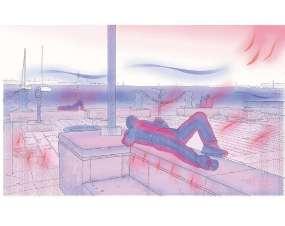

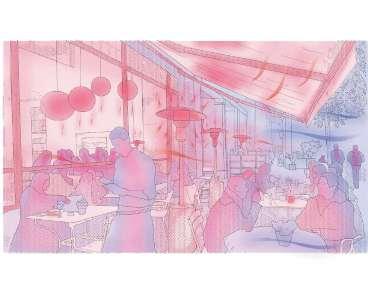

On atmospheres, constructed spaces

Arquitectos, Roger Boltshauser, Renata Sentkiewicz.This workshop departs from the structural connection that exists between the climate of a given location and the culture unfolded by its inhabitants. This question, which has been rarely addressed by architects, underpins a wide array of questions which connect climate to social patterns, local lifestyles, how people dress themselves or how architecture is inhabited.

From this perspective, a thermodynamic approach to architecture needs to explore the interactions between the local climate, the spatial and material particularities of architecture, and the lifestyle of its users. Contrary to mainstream design procedures which deploy a top-down approach which proceeds from outdoor massing to indoor space, this studio explores the potential to conceive architecture from the interior. The objective is to design a building starting from the particular atmospheres demanded by its users. As a result, departing from the specific ambient conditions needed by users, students will define the set of sources and sinks required to induce specific atmospheric situations.

#workinprogress

2024 | 03 - 04

Urban, landscape and building typologies will be a useful tool during the module as it offers the possibility to bridge the gulf between local climate and specific everyday life patterns.

Climatic typologies show how architecture can interact between a given climate and the way people live and socialize, offering the potential to connect the spatial and material lineaments with the specific physiological and psychological behaviors, bridging the gulf between the thermodynamic processes induced by architecture and the quotidian behavior of its inhabitants.

Starting from quotidian situations the studio will proceed defining interior space, and through gradual steps will explore consecutive architectural scales: first an interior climatic space and later a collective housing program. The workshop will be developed in groups of students, and each group will work in similar location in a specific climatic zone.

Body, Climate and Architecture

Living in the Nature

William Castro, Nestor Lenarduzzi, Camilo Meneses, Jeronimo Nazur, Brittany Siegert.

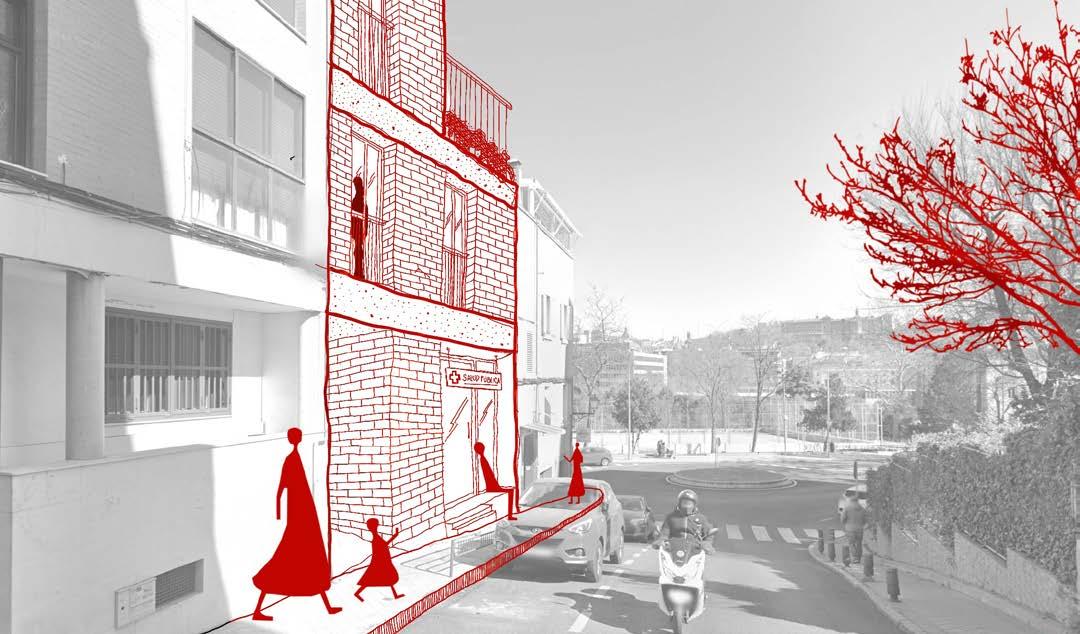

BARCELONA, SPAIN

BARCELONA, SPAIN

Barcelona is a compact city, one of the densest in Europe, with 1.6 million inhabitants in 101.3 km2 and a metropolitan area of more than 3.2 million inhabitants.

The city is between water and mountain, standing between the coastal mountain range, the Mediterranean Sea, the river Besòs and Montjuïc mountain.

Barcelona is a compact city, one of the densest in Europe, with 1.6 million inhabitants in 101.3 km2 and a metropolitan area of more than 3.2 million inhabitants.

As a mediterranian city and its location it has one of the biggest passenger ports in Europe and the world

The city is between water and mountain, standing between the coastal mountain range, the Mediterranean Sea, the river Besòs and Montjuïc mountain.

As a mediterranian city and its location it has one of the biggest passenger ports in Europe and the world

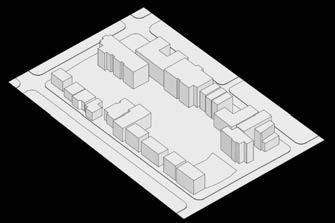

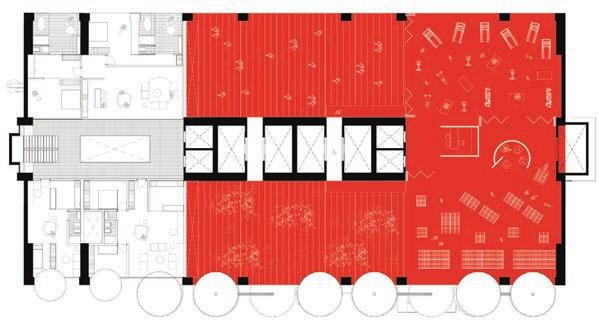

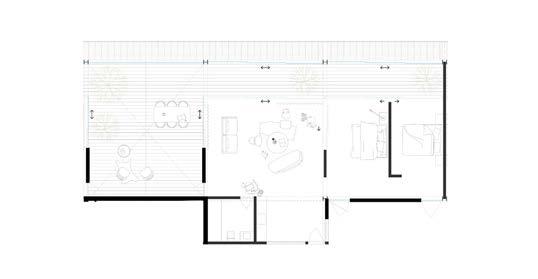

COMMUNAL BUILDING PLANS

HOUSING PRACTICE

HOUSING PRACTICE

Fernando Altozano

Specialty Leader

Javier Arpa, Enrique Arenas, Balparda Brunel, Carmen Espegel, Patrick Gmür, The Why Factory Arenas Besabe Palacios About BBOA office

Espegel Arquitectura

Santiago Pradilla, Andrés Solano

Palafito arquitectura SGGK

Esteoeste

About the specialty leader

Fernando Altozano is an architect and a GIVCO doctor, set in Madrid. At the present, he works in his own construction firm “Dos Quijotes” with his partner Sebastián Severino.

He has coordinated the MCH from 2005 until 2010 and has been a teacher at the Projects Department in ETSAM between 2010 and 2015.

He is a frequent workshop assistant at MCH and invited professor to several European universities.

He is coauthor or author of several books and articles in housing, and co-curator of the exhibition “Paris Habitat : Cent ans de ville, cent ans de vie” (Pavillon de l’Arsenal. 2015).

#workinprogress

2024 | 03 - 10

Editor’s note

The work of this specialty consisted in the development of a brief research on collective housing cases.

Each student reviewed emblematic cases, as well as new references from their places of origin, establishing a critical number of references in search of patterns or ideals, which will be represented graphically and through an analytical text.

Campactness Ratio in Buildings

Nestor LenarduzziIntroduction

ple of The vast majority of human interactions, energy consumption and waste generation are related to —or take place in— buildings and cities. Buildings and, consequently, cities are also the greatest single cause of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and the largest consumer of the Earth’s finite natural resources. D’Amico & Pomponi

General approach

Throughout history the building’s construction has responded to epochal paradigms and today is not an exception. Climate change, growing energy awareness and resource economy are issues that need to be urgently addressed.

“Global population growth and urbanization necessitate countless more buildings in this century, causing an unprecedented increase in energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, waste generation and resource use. It is imperative to achieve maximal efficiency in buildings quickly. The building envelope is a key element to address environmental concerns, as it is responsible for thermal transfers to the outdoors, causing energy demand and carbon emissions. It also requires cladding, thus consuming a significant amount of finite resources.”

D’Amico & Pomponi

As one of the many factors to consider to design and build a wiser, more sensible and efficient architecture, and consequently more economical, is the Compactness Ratio (CR). The CR is a shape parameter that relates two variables: the envelope and the volume it encloses, that is, it is the quotient between the first divided by the second (fig. 1). From the algebraic point of view a number that relates surface area to volume is obtained, being able to read it as the number of hypothetical square meters necessary to contain a cubic unit in each studied case. It is important to understand that the building envelope is the key by which thermal transfer between indoor and outdoor space occurs, thus, it is directly responsible for the building’s heating and cooling demands and related GHG, and to be able to anchor this component to the volume that allows human activities is crucial. This is not only to reduce the square meters of the envelope in relation to accommodating the greatest amount of volume possible, achieving better energy efficiency for acclimatization during the lifecycle of the building, but also to economize resources in its construction (try to build less envelope to accommodate the same volume).

State of the art

There are some studies about shape/form factor or compactness ratio and each address the topic to a geometrical problem either architectural.

According to Bernardino D’Amico and Francesco Pomponi article, there are two macro areas of research on building forms: one can be labelled as classification-seeking, that includes contributions aimed at a better understanding of the existing building stock and the other can be labelled as form-seeking, for it aims at identifying optimal or effective forms given a specific objective.

This article is going to be somehow related to the first one. Cases will be studied and this will lead the investigation to try to understand some parameters and its behaviours according to geometrical performances respect to different relations, proportions and shapes.

The study of D’Amico and Pomponi aims to provide a tool (suited to a broad range of stakeholders, such as designers, urban planner and policy makers) to help achieve a more sustainable use of resources and space through geometrial and mathematical analysis concluding in different buildings shapes (that may be taken as typologies) and its parameters.

There are other investigations aiming to reach the relation between the shape and the envelope for rehabilitation of existing buildings (Araujo Romero & Azpilicueta Astarloa), others that analises the urban shape performances of the block typologies (Fernandez de Troconiz y Revuelta) and some about choosing the building compactness to improve thermo-aeraulic comfort depending on climate (Bekkouche & others).

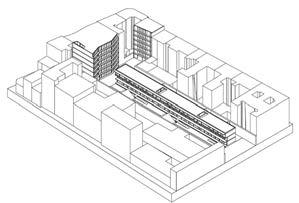

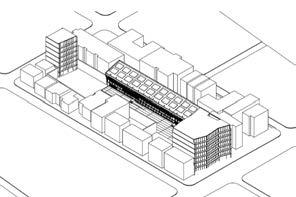

Study cases and methodology

The study of cases (maybe some architectural more iconic than others) of collective residential architecture allows to understand a problem that seems to be only geometric in a much broader spectrum. That is, if the problem of the efficiency of the architectural form is abstracted only through a mathematical term, this reasoning would fall into a simplistic (and maybe coherent) conclusion of constructing spheres that ideally are the three-dimensional shapes with minimum external surface area for a given volume, but without having into account issues as use, function, human scale, constructive feasibility, formal harmony, proportions, context, market availability, etc.

In this research, 22 cases of collective residential architecture of different scales and places were selected (fig. 2). Each of these examples was volumetrically redrawn taking into account some predetermined criteria to avoid further distortions in the comparison of cases once the calculations were made.

These conditions are:

• Envelope is the group of surfaces in contact with the environment separating the interiorexterior. Bottom face is not considered for envelope and either basements for the volume.

• Semi-covered spaces or balconies will be considered as full-covered spaces just when they are protruding and have at least four opaque faces, if not, they are exterior. The volumetry analyzed it is which makes the building identifiable

List of 22 cases (images shown from left to right and top to bottom direction) of collective residential architecture of different scales, locations and housing typologies.

Research Process.

First analysis approach

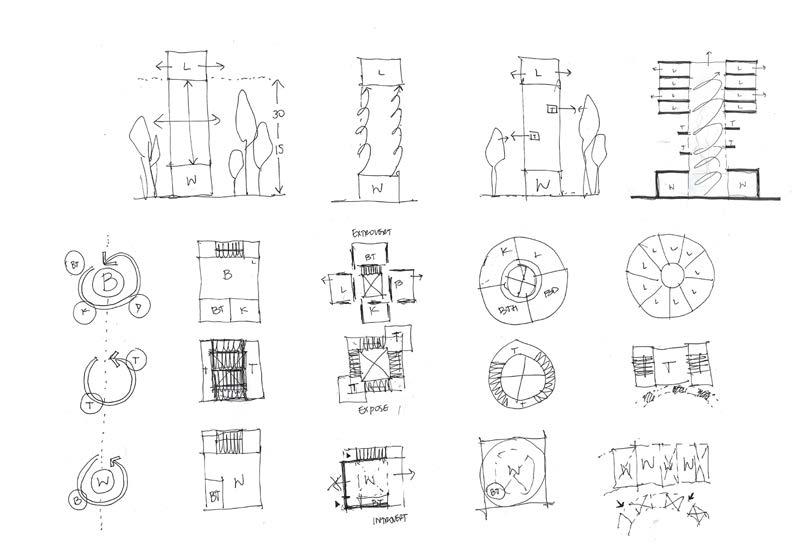

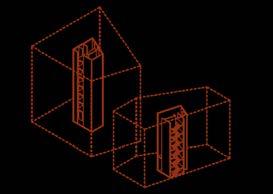

Once the 22 analyzed cases were listed, the information obtained pertinent to the two main parameters analyzed (the envelope and the volume of each building) and its compactness ratio (quotient) was arranged in a graph that allows the three aligned values to be observed (fig. 3). Accompanying this information, an axonometric view of each of the cases was provided to reference its shape and scale (fig. 4).

Subsequently, the list, the graph and the axonometrics of each case were sorted depending on their CR (fig. 5), with which the first partial conclusions could be obtained.

Compactness-Ratio (CR) ordering

At first sight, after ordering the cases by CR (from smallest to largest), an organization trend is evident corresponding to buildings of greater volume with smaller CRs and smaller volumes with larger CRs (a situation that will be developed later). Furthermore, by quickly analyzing the geometries of buildings it has also been shown that lower CR buildings tend to have purer geometries, they are more massy and the balconies are added geometries (considered exterior for the calculation) and on the contrary those with higher CR are geometries modeled through operations of subtraction (balconies are “in” the shape”), they have open groundfloors and they have more openwork (fig. 6).

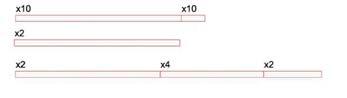

Scaling CR: Playing with the cases

After obtaining the first conclusions, it has been interesting to be able to carry out an exercise that allows relating the CR of each building with the case of lowest CR (Hauser A of Duplex Architekten).

To do so, it is necessary to change the scale of all cases, for which we must take into account that a shape scaled to a larger size (that is, increasing its envelope and its volume), will decrease its CR because the growth of the envelope (in the CR equation the divisor) and the volume (in the CR equation the dividend) are not linear and both are raised to different exponents: when the dividend grows exponentially squared (x2), the divisor does it to the cube (x3). If the shapes of 3 cubes are taken as an example, with side values 1, 2 and 3 (fig. 7) it is possible to observe that scaling of the same shape changes the CR, as the shape gets bigger the CR decreases.

Now it is important to focus on the CR reference case and the rest to be scaled and this would lead the following question to arise: how are the cases scaling grades obtained? First of all, it must be understood that the scaling has to be proportional, that is, the original shape does not lose its relations, so it is resized equally in X, Y and Z planes (fig. 8).

To obtain the scaling grade it is necessary to operate with the CR of reference and the CR of the building to be scaled. Suppose we have a building A, which is the reference CR, and a building B, which is the one that needs to be resized. The quotient is made between the reference CR and the original CR, so the percentage of increase or decrease will be obtained (fig. 9).

Using this procedure, all cases were scaled in comparison to Hauser A’s example. To have a more graphical approach an indicative scaling-grade-line drawing was made with the axonometric volumetrics of each case showing its original version (in green) and its scaled shape (in linear format).

Also to these figures, a circle was added in the lower part that refers to the degree of scaling of each case, having at its beginning “Hauser A” (as a reference unit = 1) and at its ends “Habitat 5” (as the greatest scaling grade = 3.76) -fig 10-.

After resizing, what about the volume?

After completing the escalation of all cases, a striking situation could be seen regarding the volume increase (VI) according to the increase in the CR. The VI of each building has not had a constant or linear increment in regard to the degree of scaling, or a linear relationship compared to the other cases.

For example: while Amarras Center Tower had a rescaling of 1.205, its volume has increased by 1.77 (+77%) while Kavanagh Building has had a 1.594 and 3.54 (+254%). Faced with this curious situation, it proceeded to look for a parameter that would allow this work to compare the values of the rescaled cases, so a quotient was made between the VI and the scaling grade (SG), called VI/SG.

This operation informs how much the volume increases with respect to the degree of scaling (fig. 11). Once these new parameters were obtained, the original CR, the VI and the new VI/SG parameters were listed comparatively and the corresponding graph was made.

To facilitate the reading of the values objectively and to be able to compare them, a color scale was given: from green to red in the VI and from yellow to pink in the VI/SG. When the graph is analyzed from left to right, it is denoted that all the examples with similar Hauser A’s volume have an almost linear increase relationship until the eighth case (Copa Building) where a radical change of scale occurs and the cases begin to alternate moderately following the same logic but with some more marked ups and downs (fig. 12).

Edificio Damero case

A fairly notable exception in the table color code and the graph is from the “Edificio Damero”. It was striking that this case obtained such low values of VI and VI/SG for the position where it was in the CR rescaling.

To achieve the same CR of “Hauser A” it had to be rescaled to 3.256 and consequently its volume had an increase of 10.06 times, which gives an increase in volume with respect to its scaling degree (VI/SG) of 3.091 , quite inferior to all the predecessor and successor cases in the list with much higher VI/SG (fig. 13). From there it was interesting to try to hypothesize as to which factors may be the most influential for this exception.

First, an attempt was made to anchor this phenomenon to the scale of the building, but there are cases that have similar m3 and do not apply to the rule. All cases of similar m3 (perhaps by mere chance) have a block typology, but even so the values returned by the “Edificio Damero” are curious, which even when compared with similar scales and typologies do not have a evident logic.

Intuitively, the question arose as to whether the “cubic” shape of the case could explain this phenomenon since the cube is the parallelepiped that most closely resembles the most efficient form of CR, which is the sphere. In order to determine this, the case analyzed (CR: 0.5688 and V: 3310.37m3) was compared with three examples of similar scale and typology: Andarzgoo building (CR: 0.5022 and V: 3071.53m3), Building DL1310 (CR: 0.4712 and V: 2225.61m3), and Cordova Multifamily Building (CR: 0.3576 and V: 4157.22m3) -fig. 14-.

In order to compare these cases and verify the hypothesis that this phenomenon may responds in some way to its “cubicness”, it was necessary to choose a comparative parameter which has been called “Cubicity Shape Ratio (CSR)”.

This new comparative parameter (of which no antecedents have been found) evaluates the shape of parallelepipeds taking into account their sides. The smallest side is taken as the elementary reference unit, for example L, and the quotient between the remaining sides and the reference side (that is, L1/L and L2/L), then everything is determined based on the same variable L (fig. 15). By multiplying the coefficients the CSR is obtained, that is, L x L1 x L2 = CSR. Carrying out this same operation, the CSRs of these 4 cases have been obtained, which shows that the “Edificio Damero” tends considerably more towards a cube than the rest (fig. 16).

Future investigation lines

This in some way can be taken as a trigger for another type of research: How much does CSR influence vs. the scale of the building in the CR?. In order to verify (and perhaps quantify) the influence of CSR on VI/SG (and consequently on CR), all cases could be rescaled taking the largest volume as a reference, which would allow evaluating the efficiency of the form by taking out the scale of the equation.

Thus a free-scale-comparable CR could be obtained (taking into account all buildings would have the same m3), and this would purely and exclusively show the efficiency of the shape of each one. This exercise removes a sensitive variable in the CR calculation such as the scale of the building.

In addition to what was stated, other lines of research that would be interesting to carry out could be:

1. Plot restriction (height variability): what if we would like to have the lowest-case-CR-building in all the other cases, but the only thing we can scale is the building-height

2. Building latitude (building location): what if we relocate all the buildings acording to the CR better performances depending on the latitude, asuming some ideal weather and geographic conditions

3. Facade/volume (economical relation): what if we would like to maximise the ammount of m3 and minimise the m2 of facade to improve the economical equation of the building construction.

Conclusions

Bringing the term “compactness” into the architectural world is a polite way to talk about shape (the chassis of a building) without talking about form (the internal content) and its complexity.

Taking an abstract and geometrical parameter as compactness into architecture and treat it as an isolated problem somehow permits to focus in some issues that would be very difficult to tackle all at once in the vast architectural knowledge where many sciences meet.

In this work it can provisionally be concluded that those cases with better cubic relations have a better CR performance what could be expanded and verified with several of the proposed future research guidelines. Although it has not been the objective of the research, no antecedents of shape cubicity analysis in buildings have been found, so a new parameter such as the CRS was tested. The same thing happened with the VI/GS parameter that allows evaluating how much the volume of the building increases in relation to its degree of scaling in a resize process.

It can also be concluded by mere mathematical analysis that the scale of the building alters its CR. In future approaches to this problem, it would be very interesting to be able to intertwine scale, shape and typology, to somehow analyze the extent to which they affect the CR

Although geometric abstraction allows for a much hypothetical and more detailed analysis of the shape of buildings, it is also necessary to begin to incorporate other parameters as habitability, minimum requirements for lighting and ventilation, general well-being and situations that favor the mental health of inhabitants, aspects that have been taken up and rediscussed again after the COVID-19 pandemic.

In that sense, the work of Bekkouche & others is very valuable because it is situated (that is, their analysis corresponds to a specific location) and proves that the compactness is better when the compactness ratio is lower. Like this study, there are others that would be interesting to incorporate in a future expansion of the topic, such as: the relationship between shape and energy requirements (Depecker & others, Tsanas & Xifara), materials, windows and shape (Granadeiro & others), building orientation and shape as practical passive parameters (Aksoy & Inalli) among others.

It is true that analysing the problem in an specific location would allow the research to have more restrictions with which to operate and thus obtain a more solvent and concrete result

In line with what has been said, there are also different software that allow very accurate simulations to be carried out in terms of shape optimization, including CR and many other variables. The possibility of being able to operate with computer systems could expand the horizons of research by incorporating new variables and bringing the analyzed problems closer to more real situations. This could be related to one of the future lines of research of relocation of the cases analyzed to different latitudes according to their CR. It would be interesting to be able to computationally incorporate climatic variables, which would account for a situated investigation, and to be able to evaluate how each form adapts or responds. better to local problems.

Starting to analyze isolated variables and then moving on to complex equations aided by computational models can develop new tools for better decision-making by architects, urban planners and developers in order to reduce construction costs (the stage that consumes the most amount of energy and materials) and obtain better energy efficiency over the life cycle of the building. Not to incorporate passive strategies and morphology adaptation approaches in early design stages of the building can result in a greater need for active climatisation and, thus, increased energy use.

Although the CR can be taken into account as another design strategy in all the projects, it is true it has to be emphasised when the climatic situation in certain locations defines scar thermal comfort levels and therefore the building needs to be acclimatized more frequency during the year. For example, it would not be of the same importance to have a corresponding CR in Mumbai or Salvador de Bahia than in Oslo or Dubai.

On the other hand, it would also be of great interest to be able to jump scale and incorporate the urban environment as a means of buildings interaction (like Fernandez de Troconiz y Revuelta). All the cases analyzed in this work have been taken from their singular perspective, as unique elements, without taking into account annexed volumes or party walls, which if incorporated could help to further improve their material and energy efficiency.

Aksoy U. & Inalli M. (2006). “Impacts of some building passive design parameters on heating demand for a cold region”. Building and Environment, Volume 41, Issue 12, Pages 1742-1754. ISSN 0360-1323,

Bekkouche S.M.A., Benouaz T., Hamdani M., Cherier M.K., Yaiche, M.R. & Benamrane, N. (2015). “Judicious choice of the building compactness to improve thermo-aeraulic comfort in hot climate”. Journal of Building Engineering, Volume 1, pages 42-52, ISSN 2352-7102.

D’Amico, B., & Pomponi, F. (2019). “A compactness measure of sustainable building forms”. Royal Society open science, 6(6), 181265. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.181265

Depecker, P., Menezo, C., Virgone, J. & Lepers, S. (2001). “Design of buildings shape and energetic consumption”. Building and Environment. Volume 36, Issue 5, Pages 627-635, ISSN 0360-1323,

Fernandez de Troconiz y Revuelta, Alberto J. (2010). “Implicaciones Energéticas de la Tipología de Manzana”. Tesis doctoral. UPM-ETSAM.

Granadeiro V., Correia J. R., Leal V. M. S. & Duarte J. P. (2013). “Envelope-related energy demand: A design indicator of energy performance for residential buildings in early design stages”. Energy and Buildings, Volume 61, Pages 215-223. ISSN 0378-7788

Tsanas A. & Xifara A. (2012). “Accurate quantitative estimation of energy performance of residential buildings using statistical machine learning tools”. Energy and Buildings, Volume 49, Pages 560567. ISSN 0378-7788

SOCIOLOGY ECONOMY AND POLITICS

SOCIOLOGY, ECONOMY AND POLITICS

Daniel Sorando

About the Specialty Leader:

Daniel Sorando earned his undergraduate degree in Sociology from the University of Granada, before studying his Master’s in Population, Society and Territory at Complutense University of Madrid (UCM), his Master’s in Research Methods in Social Sciences at Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, Madrid, and a Ph.D. in Urban Sociology at UCM.

He was also a Visiting Scholar at the University of Brown. His research focuses on social structure, residential segregation and urban policies. He teaches at UCM, where he has worked in several R&D projects. As a result of his research he has published several articles and book chapters in scientific journals and collective works.

Editor’s note

The work of this specialty consisted in the development of a research on several neighborhoods in Madrid, focusing on collective housing and the city, using census data, interviews and field visits as a means to understand the current problems of the sector and its potential improvement through architectural interventions.

2024 | 05 - 07

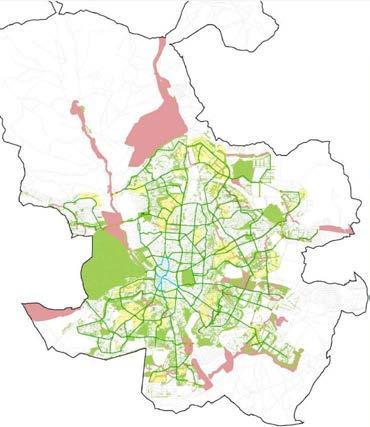

Puerta del Ángel, Madrid

Isabel Monsalve, Vyoma Popat, Brittany Siegert, Ángela Tamayo.

Distrito de La Latina Latina is district No. 10, located in the southwestern part of Madrid across the Manzanares River from the city center. It is made up of seven barrios: Los Cármenes, Puerta del Ángel, Lucero, Aluche, Campamento, Cuatro Vientos and Las Águilas.

Barrio de Puerta del Angel Puerta del Ángel is barrio No. 10.2 located closest to the city center of all the barrios in the Latina district. It is bordered on its North and East sides by the A-5 and the M-30, respectively, both of which have been buried, providing the neighborhood with better connectivity to the city center and the adjacent Casa de Campo. The neighborhood is also next to the somewhat recently constructed Madrid Río and a the Segovia Bridge separates the neighborhood from the city center, giving it a distinct character that has been compared to New York’s Brooklyn.

objectives This research attempts to address the economic, social, and political problems confronting Puerta del Angel as the transformation of the Madrid Rio has affected the housing market of the neighborhood. It will explain the current residential conditions and how the neighborhood has evolved over time by identifying the sociological issues associated with the housing situation and by defining a proposal for an architectural intervention which can improve the conditions.

hypothesis The historical neglect of the Manzanares River caused Madrid’s city center to metaphorically turn its back on the river, and consequently isolate the neighborhood of Puerta del Ángel. Since burying the M-30 and constructing the Madrid Río, the neighborhood has become more integrated into the city and therefore a much more desirable place to live. It has improved the quality of life in the neighborhood for those living there, but simultaneously attracted a new demographic who are interested in living in a neighborhood closely linked to the city at a cheaper price The process of gentrification has begun in the neighborhood as rental prices continue to rise, though Puerta del Angel has not yet seen the displacement of its residents in extreme numbers.

Historical Context

1800’s - 1960’s

In the 1800s, Puerta del Angel was a small, relatively unpopulated neighborhood of Madrid, despite its proximity to the city center. This was due to several streams which cut through the neighborhood, Goya’s expansive estate, the adjacent Casa de Campo, and because it was across the river from the center. It was mostly composed of small industries, orchards, and roads until 1882, when Goya’s estate was replaced by Goya train station, connecting Madrid to other cities of Spain and giving Puerta del Angel more prominence in the city.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Puerta del Ángel was still a relatively rural area characterized by open fields, small farms, and orchards, but it slowly began to become more populated. The Parish of Santa Cristina was built, and Paseo de Extremadura, an important thoroughfare of the neighborhood which still exists today, was lined on either side with houses. Eventually, Puerta del Angel was connected to the city center via tram, and Mercado Tirso de Molina was built.

From 1936 - 1939, during the Spanish civil war, much of Puerta del Angel was destroyed, which ultimately led to significant urbanization and population growth during the post-war period. New residential buildings and infrastructure were developed, attracting new residents to the neighborhood.

During the 40s and 50s, Puerta del Angel continued to grow, as public initiatives supported the development of new housing. Several pockets of the neighborhood managed by developers become home to homogenous housing types. Much of the housing built was very small in area and was built with poor construction quality. Because of this, the neighborhood was in bad condition by the 60s, with residents hosting trading and selling stolen objects in the streets and giving the neighborhood a reputation of insecurity.

Historical Context 1800’s - 1960’s

In the 1970s and 1980s, Puerta del Ángel experienced further urban development; housing built under public initiative was replaced by new housing projects, including apartment buildings and townhouses, built under subsidized private initiative. After the Goya railway station is shut down, housing blocks of up to ten stories begin to appear in its place. However the reputation of insecurity persisted, as Puerta del Angel was also one of the sites of the heroin epidemic in the 80s.

The 1990s marked a period of revitalization and improvement for Puerta del Ángel. The city government invested in the renovation of public spaces, such as parks and plazas, to enhance the quality of life for residents, and the neighborhood was connected to the metro system by line 6. The neighborhood also saw an increase in commercial activity, with new shops, restaurants, and services opening up.

In the early 2000s, the neighborhood continued to evolve as a residential area with improved infrastructure and amenities. Its low prices and proximity to the city center made it an attractive location for immigrants, making it one of the neighborhoods with the highest percentage of foreigners, which is still true today. Following the 2008 financial crisis, the neighborhood became somewhat empty again, as much of the commercial activity came to a halt and businesses were forced to shut down. This created opportunities for investments in the neighborhood, including the development of the Parque Madrid Rio which included burying the A-5 and M-30 and was opened in 2011.

Population

Puerta del Angel is one of the most dense neighborhoods of Madrid, with approximately 40.000 inhabitants at a density of 30.433 inhabitants per square kilometer compared to Madrid’s 5.337 inhabitants per square kilometer.

Unemployment

Puerta del Angel has a low unemployment rate overall as well as specifically for women. The unemployment rate has been steadily decreasing ove the last ten years, with the exception of the years during which the Covid-19 pandemic affected employment worldwide. Unemployment rates have since fallen even lower than they were prior to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Foreign nationality

Puerta del Angel is very diverse compared to the rest of Madrid, with 21,6% of individuals living in the neighborhood having foreign nationality. Of the 131 neighborhoods in Madrid, Puerta del Angel ranks 21 as most diverse.

Social condition / Age

A much larger percent of the population is between 16 and 64 years of age when compared with Madrid overall. The percentage of individuals in this age range has grown significantly in this neighborhood compared to the rest of Madrid, while the number of children has decreased. Compared to the rest of Madrid, Puerta del Angel has a similar percentage of individuals over 64 years old and a lower percentage of individuals below 16 years old.

Income

Puerta del Angel has a relatively low average income compared to the rest of Madrid, at 30.717 euros on average compared to Madrid’s 43.003 average income. The average household income has grown at a similar rate in both the neighborhood of Puerta del Angel and Madrid overall over the past ten years.

Prices (sale, 90% of housing stock)

Since January 2009, sale prices for property in Puerta del Angel has dropped and then risen again, dramatically compared to the rest of Madrid. Since then, the highest average cost was in Seprember of 2009 at 2.957 euros/square meter; it then dropped steadily until 2015, hitting a low point in August of that year at 1.660 euros/square meter, and finally rising back the current highest prices averaging 2.883 euros/square meter in 2023. These numbers remain low in comparison to Madrid’s overall average cost, currently 4.002 euros/square meter, the highest it has ever been.

Prices (rental, 10% of housing stock)

Unlike sale prices, the rental prices in Puerta del Angel have trended steadily upwards since 2011, with the exception of a decrease in average rental prices during the Covid-19 pandemic. Average rental costs have increased by a total of 4 euros/square meter since 2011, now averaging around 15 euros/square meter as compared to 11 euros/square meter twlelve years ago.

Housing typology

In Puerta del Angel the residential blocks are the most common building type. Nevertheless, they can be clearly categorized into two main groups: pre 1960s and post 1960s. The main characteristics of the first group are: height of between two to four floors and a smaller scale due to smaller plots. On the other hand the second group consists of higher buildings, more than five floors, that leave space on the plot for a semi public or comunal green area. Both typologies help with the area’s density and provide a sense of community with has been one of the biggest attributes of the neighbourhood.

Household size + neighborhood density

The average household size in Puerta del Angel is slightly lower than the rest of Madrid, with around 2,3 inhabitants per home on average as compared to Madrid’s 2,55. Because the overall density of Puerta del Angel is very high, we can assume that there are many small apartments (one or two bedrooms) in Puerta del Angel when compared to the rest of the city.

Green spaces

The periphery of Puerta del Angel is rich with parks, as it is located adjacent to Casa de Campo and contains part of the Parque Madrid Rio, as well as Parque Caramuel; however the neighborhood lacks developed public squares and other outdoor spaces inside the neighborhood, where it would be more closely associated with the housing. Connections to the large peripheral parks have been strengthened overtime, increasing the value of the neighborhood within the context of Madrid.

Gentrification Studying Puerta del Angel led to the conclusion that while the process of gentrification has begun in the neighborhood, there is insufficient evidence to support the claim that the neighborhood has been gentrified at this point. The neighborhood has seen many improvements over the last ten years, including improvement of streets, infrastructure, security, and parks, along with an influx of middle class citizens. However, the neighborhood has not yet seen significant displacement of the existing community of the neighborhood, a key factor of gentrification.

Housing The property market in Puerta del Angel has experienced both ups and downs over the years, with prices dramatically rising and falling. Nevertheless, it appears that the area’s property prices have not reached the same level as the broader Madrid market, where prices have been consistently higher and have recently reached record highs. Contrary to sale prices, the rental prices in Puerta del Angel have shown a consistent upward trend since 2011, except for a decline during the Covid-19 pandemic. Over the past twelve years, average rental costs have risen by 4 euros per square meter, reaching an average of approximately 15 euros per square meter, compared to 11 euros per square meter a decade ago. This difference in sale and rental prices is an opportunity for private investors to take advantage of low to average sale prices and rent housing at higher than average prices, turning a significant profit and contributing to the gentrification of the neighborhood.

Proximity to parks Within the neighborhood limits, three parks can be found: Madrid Rio, Parque Caramuel, and Parque del Olivar. However, it’s important to note that north of the neighborhood lies Casa de Campo, which is not technically part of Puerta del Ángel but is conveniently accessible for its residents. After analyzing and considering the park locations, it becomes evident that the far west side of the neighborhood lacks adequate park spaces. Additionally, there are some noticeable gaps in small green spaces and plazas for the residents. These findings underscore the potential need for further urban planning and development to ensure a balanced distribution of parks and green areas within the community.

Cycles of poverty and redevelopment Puerta del Angel has been through many cycles of redevelopment. For example, during the Spanish Civil War, it suffered extensive destruction. However, in the aftermath of the war, the neighborhood underwent significant urbanization and experienced a surge in population. This transformation was facilitated by the development of modern residential buildings and essential infrastructure, which attracted an influx of new residents to the area. The post-war period witnessed a remarkable revival and growth for Puerta del Ángel due to these initiatives. Then, in the 1960s and 1970s, Puerta del Ángel witnessed significant urban growth, with the original public housing being replaced by new apartment buildings and townhouses constructed through subsidized private initiatives. Despite these developments, Puerta del Ángel struggled with a persistent reputation for insecurity, partly due to its association with the heroin epidemic that plagued the area during the 1980s. In contrast in the 1990s, the quality of living was improved again, by the revitalization of the neighborhood, new metro stops, new plazas, new parks, etc. After the 2008 financial crisis, the neighborhood experienced a decrease in population as a result of a significant decline in commercial activity, leading to the closure of businesses. This resulted in a somewhat empty and deserted atmosphere in the area. Now, Puerta del Angel is experiencing another period of revitalization and influx of residents.

Lifestyle Based on the interviews conducted with the residents, our findings suggest that the neighborhood continues to exude the essence of the traditional “Madrid lifestyle,” and the authentic spirit of the Spanish city remains intact; however, they also reported the fear of losing this neighborhood feeling as one of the biggest concerns with the evolution of the neighborhood.

Density and apartment size The neighborhood exhibits a density nearly six times higher than the average in Madrid, indicating a well-densified area with efficient land utilization. While this observation reflects successful urban planning, it also raises pertinent questions concerning the potential impact of gentrification and resident displacement. Byadvocating for government owned housing, enforcing fixed rent control prices, and promoting community engagement, the neighborhood can retain its vibrancy, preserve its unique character, and ensure the continued well-being of its residents in the face of urban development.

additional housing only as infill

maximize height without exceeding surrounding buildings

infill social housing provided at a fixed price by the government

prioritize traditional spanish community

improve exisiting urban spaces

introduce small scale green spaces into each subdivision of the neighborhood

introduce public amenities to storefronts around new plazas + infill housing hybridize infill construction

activate storefronts surrounding plazas

Segregation and Apeculation as a Result:

Land (de)regulation in Mexican cities

Fernando González García MorenoIntroducción

Housing as part of the Real Estate Market instead of a basic human right, makes it vulnerable to the interests of capitalism. The moment in which a profit can be made, the reasons for acquiring a home cease to be personal, as could be the proximity to your work, family or services, or simply by meeting the characteristics you need, and become factors that allow to generate a greater return on investment, either by the area in which it is located, or by the very conditions of the house, like the dimensions, the number of rooms, etc. REIT’s and single private investors will always look for a greater revenue over their investment, which result on foreseeing a possible added value to the property they intend to buy, purchasing it not out of necessity, but by investment. This is called Real Estate Speculation.

Speculation can be seen throughout consolidated neighborhoods in the way of gentrification or touristification, where properties are bought at a discount price to later either sell it for a profit or rent it for an amount higher than the current one. Nowadays it seems that the only way to manage this phenomena is with rent control, to prevent investors from being able to increase the rent to their liking and generate the displacement of the local population from these areas.

Another “asset” subject to speculation, other than the built “product” itself, is land. By briefly going through Spain’s Real Estate Market and its characteristics, we will set a work frame for analyzing the factors that make Mexican cities vulnerable to speculation and corruption, affecting greatly the quality of life of its population.

Spain

During the real estate boom in the beginning of the century, most cities in Spain saw a disproportionate development to the demand for housing, creating a greater supply than necessary due to the surplus of financial liquidity of world banks, which, through cheap loans, sought to place homes in the hands of people who did not need them, or who did not need them under those particular conditions. The government, knowing how beneficial the construction industry is for tax revenues, economic growth indicators and sometimes corruption, allowed the expansion of cities to the peripheries.

When the real estate bubble exploded, millions of SqM of land had been already urbanized and were left empty, with poor quality buildings and paid with subprime credits that ended up being abandoned. This was a clear example of the result of speculation with weak regulation. Weak regulation because at the end of the day, there was a regulation that allowed it, the problem is that there was not really a justification beyond the growth and economic benefit of a few.

The 2018 bubble represented a learning opportunity about how

fragile the real estate market is and how dangerous the lack of regulation is. Although mistakes continue to be made in favor of the economic benefits of private companies, urban growth has since been controlled and regulated. It has been sought that the land already urbanized be gradually filled, seeking to provide it with services that can make it attractive for newcomers and effectively cover a real demand for housing. Meanwhile, new land has not been transformed from agricultural or ecological to urban use, which in itself is a way of controlling speculation.

Limiting investment in urban growth has focused resources on improving the already consolidated areas of the city, providing existing neighborhoods that already have services with better conditions, making them more attractive to live than any new development in the peripheries. This has been gradually transforming low income, mixed neighborhoods into gentrified, segregated, higher class ones.

Currently in Spain the rent control law has been approved, which could represent the solution to the problem of gentrification, along with policies that would limit touristification, it would seem that the problem of speculation and the consideration of housing as a good or business could be controlled to some extent. This must go hand in hand with a better distribution of services and infrastructure to all areas of the city, in order to release pressure on those that could be considered attractive right now. If this is achieved, in addition to new social housing being built, as well as a rearrangement of the main economic activities that could better distribute the flow of people within the city, we could think that it would improve the quality of life of the cities and their inhabitants.

After this brief review of the case of Spain, which is similar to many other countries in Europe and that could serve as an example of a developed country, with a mix of familistic, latin culture and a great capitalistic US influence due to money flows, we approach the case of Mexico, a country that presents similar political and social issues of Latin America, with a mix of Spanish urban and cultural influence and a close relationship with the United States.

Mexico

The growth model of the North American city was developed in the first decades of the twentieth century by the Chicago School. This model of growth of cities locates a central business area surrounded by a mostly industrial area of transition, subsequently there is a working class area, then a middle-class residential area and finally the suburbs where the upper class lives.

In Mexico around the 1920’s this idea of modernism was adopted and the growth of cities towards the peripheries started. The emptied city centers were then filled by the lower income population. At this stage and throughout the second third of the XX century, we could see three types of urban growth. Two of them

by the legal route, mostly for middle and high income population, in the shape of large suburban residential areas and on the other hand the sprawl of the urban fabric, which eventually reached the suburbs. The other one came to be informal settlements towards the outskirts of the city, mostly in agricultural and high risk land, which at some point ended up caught in between the central neighborhoods and even surrounding some of the suburbs.

The various forms of land ownership generated a constant tension between the growth of the city and the existence of “Ejidos” that put in risk the continuity and urban growth due to the nature of article 27 of the constitution coined after the Agrarian Law of 1915 that defined Ejidos as a collective land, undivided and without the possibility of being sold or inherited. Ejido lands were owned by the State and could not change the use from agricultural to urban, hence when the city grew on ejido lands, such settlements were considered “irregular” and therefore took long time for services to finally reach them.

After the 1970’s, with the massive migration of population to the cities, a lot of pressure was placed on the land and governments were unable to regulate this growth, giving rise to hundreds of irregular settlements that eventually became permanent. As part of this informality, the ejidal lands were an escape for a large mass in need of a space to live that with the complicity of authorities, leaders and ejidatarios, consolidated the existence of irregular settlements in all the cities of the country.

Between 1991 and 1993, the great constitutional reforms to the agrarian regime were carried out, which fundamentally facilitated the disposition of social property, giving “ejidatarios” the possibility to get property titles. This law was the breaking point for not only normalizing informality but capitalizing on it. Instead of strengthening the public institution’s power over land regulation and urban planning, this represented a desperate measure to allow urban growth and investment, but it never took into account the next steps to promote municipalities to use it as means for an ordered urban growth. With debilitated institutions, privatization and deregulation were the government’s answers for allowing private investment in all areas of economy and social welfare.

This has since generated a huge problem of speculation and corruption, because it is no longer only considered housing or real estate as objects of investment, but the land itself. All land is available for development as long as the municipalities allow it, no matter if it meets or not the demand or if the government can provide the basic services and infrastructure. Governments have limited themselves to allow for land use changes and basically asking in return for the minimum accessibility to this private plots, no matter their location, size or shape.

Before the modification in the article 27, land was illegally being used for construction; services weren’t given in accordance and there was no urban planning, but it was still illegal, thus leaving

an opening for intervention either for improving or removing this settlements with the intention of creating a sustainable urban model. Nowadays the city still grows the same way, with no planning, no services and building in rural or ecologically vulnerable areas, but now it is legal. This of course, gives some certainty and security to the inhabitants, but it is a tragedy with no return in terms of urban development, ecological sustainability and city life.

The government also saw an opportunity within an already existing private management model: the condominium. The condominium regime include now the rules that dictate coexistence and development where urban planning and policies don’t exist. This scheme was first allowed in vertical developments, where it regulated life within the same structure, but by allowing the use of the same model in horizontal developments, it has caused the complete loss of the city. Zoning is decided by developers and it is legally impossible to change the use or reconfigure the urban structure of these areas since by law each owner is in turn assigned a proportional part of the common areas. This then generates a maintenance fee that pays for all services provided within the condominium, which would also make taxes completely useless, but are still demanded.

In addition to this, the real need for basic services and human interaction exists. People want to live in a place where they can exercise, have green areas, feel safe, etc. But instead of this being part of the city, new projects include all this amenities within the same development with slogans that romanticize having “all you need without having to leave your doorstep”. As the government fails to ensure the basic wellbeing of people, private developers profit from this and use it as a sale’s pitch, making the breach between high and low income population even bigger. You can only have wellbeing if you can pay for it.

Conclusions

Walls and fences around neighborhoods and barriers in streets have been spread through the urban geography. These demonstrations are copies of the American gated communities, which emulate the medieval walled architecture. With the influence of globalization and economic transformation and its consequences in the deregulation of urban growth, this become powerful forces that strengthen the process and development of exclusive reserves (Borsdorf, 2003:1).

The process of urbanization in our country is an irreversible phenomena with very high costs for society due to the lack of planning, a problem that has been manifested specifically in lands of agricultural centers that have been devoured by the urban area, with or without their consent, altering their organizational and productive premises. (Aguado and Hernández, 1997)

The modification in the article 27 of the constitution was necessary to allow cities to grow, but the complete disregard for urban planning and service provision by the government, has set the ground for an urban growth model based on private interests, all land can become subject for development if you reach the price and services are offered as amenities for those who can pay them. Segregation has become literal in the form of walls and condominium regimes regulate even the size of the households, not allowing it to evolve and change in the future.

It is hard to predict the future of Mexican cities, there is little space left within urban areas for interventions that could improve the quality of life and connectivity. It is every day becoming more difficult and expensive to add urgent infrastructure in this areas. Expropriating land to make room for roads or services is almost imposible due to condominium schemes and the high prices of land as a consequence of speculation. Many of this areas have started their decline and eventual death because life conditions are simply unbearable, but they are still being built all over the country and the social and economic cost that they are causing is invaluable

References

Bojórquez-Luque, J (2011) “Importancia de la tierra de propiedad social en la expansión de las ciudades en México”. Ra Ximhai, vol. 7, núm. 2, mayo-agosto, 2011, pp. 297-311. Universidad Autónoma Indígena de México

Sobrino, J (2012) “La urbanización en el México contemporáneo”, núm 94, pp. 93122. El Colegio de México.

Borsdorf, A (2003) “Cómo modelar el desarrollo y la dinámica de la ciudad latinoamericana” EURE (Santiago) v.29 n.86 Santiago

Janoshcka, Michael (2002). “El nuevo modelo de la ciudad latinoamericana. Fragmentación y privatización”. Eure, diciembre, Vol. 27, Núm. 85. Pontificia Universidad católica de Chile, Facultad de arquitectura y Bellas Artes, Instituto de estudios Urbanos, Santiago de Chile.

Bazant, Jan (2008). “Procesos de expansión y consolidación urbana de bajos ingresos en las periferias”. Revista Bitácora Urbano Territorial, Vol. 13, Núm. 2, juniodiciembre, 2008, pp. 117- 132. Universidad Nacional de Colombia

Aguado Hernández, Emma y Francisco Hernández y Puente (1997). “social y desarrollo urbano: experiencias y posibilidades”. Estudios agrarios Núm. 8, julioseptiembre de 1997, México, Procuraduría Agraria.

Sorando, D. &. (2019). “Distant and unequal : The decline of social mixing in Barcelona and Madrid”. REIS, Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 167, pp. 125-148.

Gideon Bolt , Deborah Phillips & Ronald Van Kempen (2010) Housing Policy, (De) segregation and Social Mixing: An International Perspective, , 25:2, 129-135

Melissa García-Lamarca (2020): Real estate crisis resolution regimes and residential REITs: emerging socio-spatial impacts in Barcelona, Housing Studies, DOI: 10.1080/02673037.2020.1769034

DIARIO OFICIAL DE LA FEDERACIÓN; Ley Agraria publicada el 26 de febrero de 1992, H. Congreso de la Unión, México.

CIUDAD DORMITORIO

https://www.elsoldepuebla.com.mx/local/cuautlancingo-en-riesgo-de-convertirseen-ciudad-dormitorio-con-carencias-de-servicios-basicos-11471032.html

REAL ESTATE MARKET

https://www.statista.com/outlook/fmo/real-estate/worldwide#:~:text=The%20 value%20of%20Real%20Estate,US%24498.60tn%20in%202023.

REAL ESTATE MARKET

https://realestatemarket.com.mx/mercado-inmobiliario/37767-urbanismo-30-anosde-crecimiento-en-mexico-1992-2022

Source: SIG UC

Alternatives to the Housing Crisis in Chile

Camilo Meneses FerradaAbstract

Chile, like any other country in the world, has employed various methods to provide housing for its most vulnerable citizens. Ranging from basic sanitary sheds to extensive housing complexes, the array of strategies and typologies appears almost limitless. These multiple approaches stem from a basic phenomenon related to the need for housing and the state’s capacity to finance, manage and build it.

The Chilean model, founded on principles of free competition, has relegated the role of the state in favor of fostering the market. Housing has been treated as both a consumer good and an asset, but the absence of regulation and state management has promoted segregation and real estate speculation. This has led to an estimated deficit of more than 650,000 homes.

Numerous policies have been implemented to address this crisis, always framed within the context of the current constitution established during the dictatorship. The big question is whether these measures will genuinely suffice to reduce these figures, or if more fundamental structural changes are necessary.

Keywords

Housing, State Regulation, Financing, Consumer Goods, Right to Housing.

The Evolution of Social Housing

The first notable state intervention in the realm of a national level occurred in 1906 with the “Workers Housing Law”, which defined minimum habitable conditions in terms of health for the growing working class of the time (Hidalgo, 2005). However, was not until 1932 through the “Cheap Housing Law” that these ideas materialized by establishing a means of financing to produce housing within the national territory (Alcaino, 1942). This approach utilized mortgage credit funds to stimulate housing management and construction, consolidating the establishment of the “Popular Housing Fund” in 1936, where mandatory pension funds were used to finance this type of interventions, through various minors capitals who endorsed the creation of housing for their own members. This was the beginning of the management of multiple housing projects, and in turn, the use of these investment funds as their main operating support.

Later, following several national catastrophes, a shift in the model led to a massive formula in 1953, where large housing complexes were developed through state management and construction companies, guided by the Urban Improvement Corporation - CORMU and the Corporation of Housing - CORVI (Raposo, 2011). Although these complexes boasted high standards and were well received, their construction cost proved prohibitive in

addressing the prevailing housing demand. This prompted a new model in 1965, focused on site operations that allocated small lots with basic sanitary sheds to families.

This approach provided the basic minimum for the construction of the home, but above all its roots behind the right to ownership of the land given, promoting low-rise self-construction and a sense of belonging in the neighborhoods. Consequently, Chilean cities expanded exponentially, considering as an example that only in the capital, Santiago de Chile, 466 new neighborhoods were created under this system at the time. (Palmer & Vergara, 1990)

After the 1973 dictatorship, population displacement policies began in communes with high economic income, pushing vulnerable family groups to the city outskirts and significantly expanding urban limits. In addition to this change, the public organizations designed for housing management were reduced, relegating their function to subsidiary financing and supervision through the Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning - MINVU, and handing over the main design and construction tasks to private entities, such as mediators between the State (principal) and the beneficiary (citizen), and where the latter is forced to acquire a mortgage loan to cover the differential cost of the property. This change led to an increase in debt on the part of the beneficiaries and a loss of resources on the part of the Ministry, who were the main lenders at the time.

During the 2000s, the Ministry’s role transformed further, subsidizing private home purchases and introducing new neighborhood models, offering financial support for minimal housing units (land and structure) of approximately 33m2, usually prefabricated housing solutions that are purchased from private parties without debt, which allowed families to expand over time. (Navarro, 2005)

The Current Model and the Crisis

In the private sphere, the capitalist model enforced during the 1970s dictatorship led to the centralized privatization of workers pension funds through loans to large financial entities. This injection of capital was, and continues to be, the fundamental support of the country’s economic policy. In this scheme, the State forces workers to contribute a percentage of their monthly income to the AFPs, private pension fund management entities which can freely invest, lend and finance private projects of large economic groups, establishing a minimum profit for the affiliate, and in turn multiplying the capital for themselves and future investments; It should be noted that affiliates cannot decide what to invest in, and on the contrary they are only participants in establishing the risks willing to take according to ranges established by the AFPs themselves, and in addition they must absorb the total loss of the investment in the event of that this is not beneficial.

Consequently, large real estate groups have since managed housing in Chile, requesting loans with a lower cost from the AFPs for the construction of new housing, which is sold to citizens (affiliated with these same systems), supported by a contribution state that helps reduce this value through a subsidy. In short, the state provides money to pay for private housing for its citizens, who, in turn, are the ones who lend their pension money to large economic groups that manage the housing. Likewise, the contribution to be made by citizens mostly corresponds to bank loans with high rates, which are also financed by private banks with support from the AFPs, therefore, again the worker pays for everything and this time in a higher cost.

This arrangement persisted, with new housing models that further aggravate the problem, such as the creation of housing in the periphery with low connection, hyperdensity housing in small spaces, high loans and real estate speculation by the non existing land price regulation policies, among others, all considering that, more than the development of housing as a right, it corresponds to state benefits that include housing as a good, promoting the purchase market from private entities, partially or total, these being the main beneficiaries rather than a support system for the citizens themselves, even worse, considering that this entire scheme is financed with the workers’ own savings for their retirement. Consequently, the current housing crisis in Chile emerged when banks became apprehensive about extending credit for home purchases.

Today the country, according to data from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning - MINVU, presents a deficit of 650,000 homes, an unprecedented figure since 1996 (Déficit Cero + CPP UC, 2022). Families are increasingly falling below the poverty line, residing in subpar conditions or illegal settlements. Projections indicate that these numbers will triplicate with the new 2023 CENSUS, where those who live with relatives or subtenants within the same home will also be registered. The Ministry itself has investigated various alternatives to remedy this deficit, but

the question remains open as to which housing financing model will be the most effective to fight against this crisis.

Thoughts on Housing Value

The housing crisis is not exclusive to Chile; it is an escalating global phenomenon. Housing-bases wealth, meaning housing values minus mortgage debt, has reached historically unprecedented levels internationally, implying that real estate has become important as a store of value for households in the era of financialization. (Fernández & Aalbers 2016)

To address the housing deficit, various authors reaffirm that, to resolve the current housing deficit, it is not possible to avoid the existing contraction between private and public interests (Correa, Vergara, Truffello & Aguirre, 2023), understanding the duality of housing as it is a good of consumption and in turn a basic need and right.

Regarding the cultural sphere, we know that, in Southern European countries, the main roots of South America, housing is considered a family heritage both in practical, material, emotional and symbolic aspects (Allen et al, 2004), that is, it has a burden linked to tradition and heritage that fosters roots and a sense of ownership, even more so in Latin American countries where it acts as a source of family protection in the absence of a welfare state that supports them, for the same reason, the value housing is recognized as something more than the purely economic. In this way, the problem becomes even more complex, since these new variables must also be considered in the equation before any type of intervention.

Reforms for Price Regulation

Following more effects of the dictatorship, after the loss of state powers in housing and management, was the liberation of the urban land market. With this, the State largely privatizes public land, leaving it without essential capital for housing construction, and with this, relegated to private management and development. Consequently, real estate speculation and the supposed selfregulation of the market generated a financial bubble where housing prices exceeded the credit capacity of citizens, causing the most vulnerable population to be relegated to living on the outskirts of the city or with relatives in large family groups.

After the National Urban Development Policy in 2014, and subsequent creation of its Council, the discussion on this topic is opened again, where one of its fundamental axes was establishing a land policy to promote social integration, this is expected promote regulatory changes to regulate housing prices, through the so-called new Urban Integration Law.

On May 27, 2022, Law No. 21,450 was officially published, which approves the Law on social integration in urban planning, land management and housing emergency plan. This promotes three fundamental changes in territorial management and regulation, considering that (i) it allows the MINVU to obtain land, generating

a bank of properties that allows social housing to be inserted in consolidated neighborhoods and not only in the periphery, (ii) it allows to create, together with the community, local regeneration plans including regulatory incentives for the creation of public interest housing, and finally (iii) mandates the MINVU to create a Housing Emergency Plan, with goals by region and commune, including monitoring and evaluation mechanisms that allow us to confront the crisis.

Although this law empowers the State and may regulate the market, it is still framed in the current constitution where there is no mention of housing as a right and, on the opposite, allows the private sector to be a fundamental part of its creation, considering it a good. It will take a couple of years to know if this change has really been effective, or if new regulations or structural changes will have to be added to improve the current situation.

Conclusions