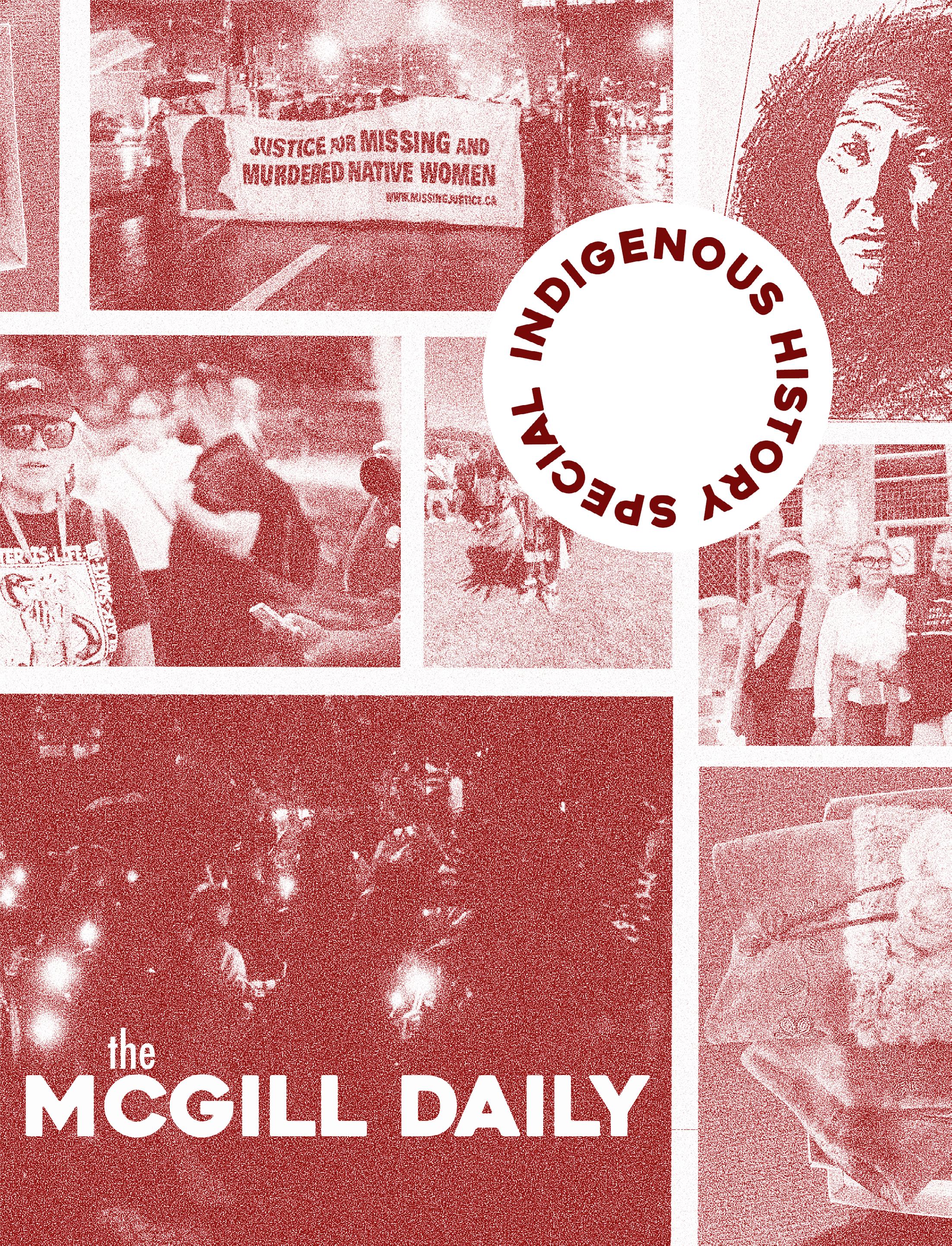

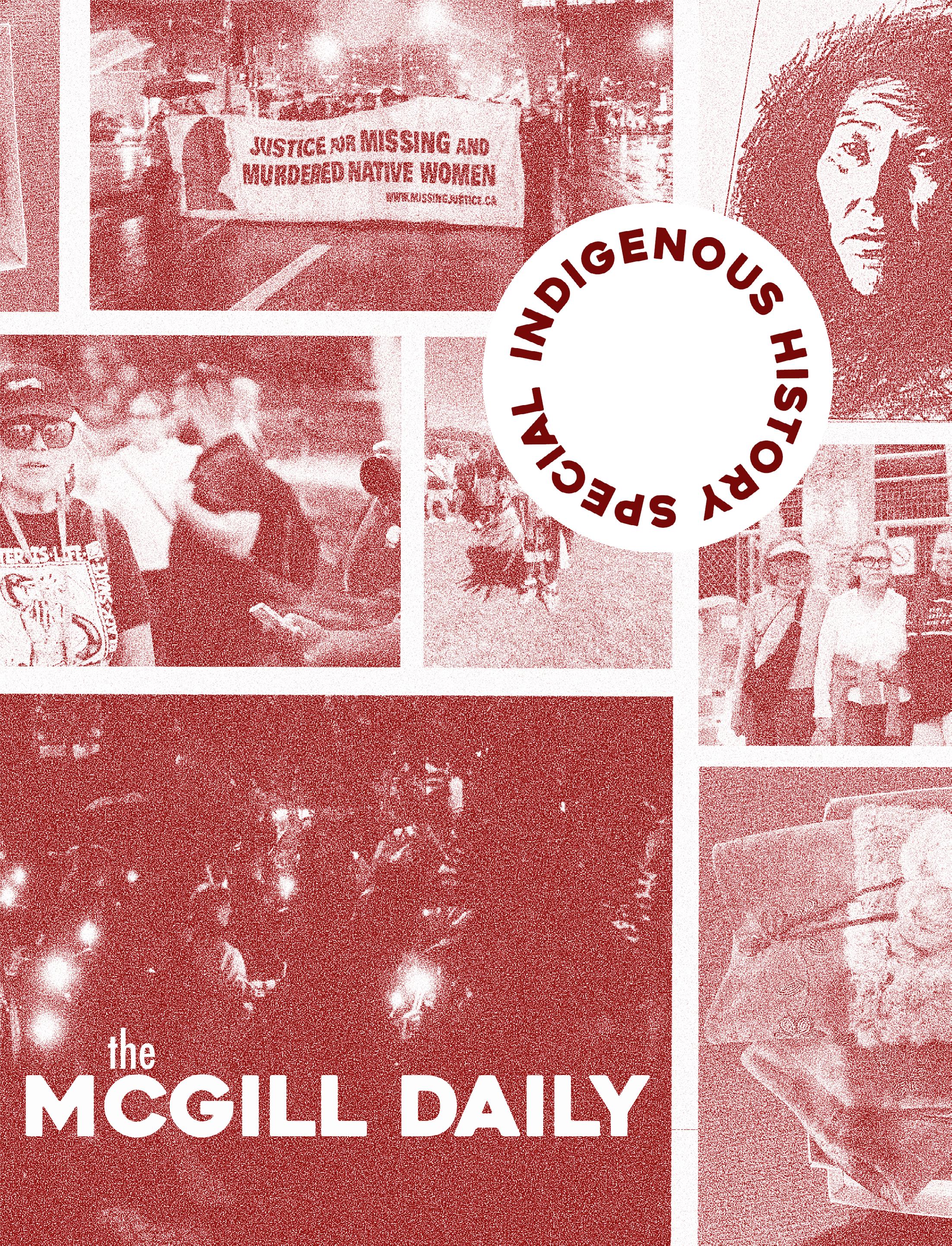

Editorial 3

Silencing Languages, Erasing Histories

News 4

Montreal’s New Metro Stations

Good People

The Green Update

McGill’s 24th Annual Powow

Sci-Tech 6

Demystifying Cancer

7

Indigenous Memories at the MEM Dali the Band

The Y-Intersection Mural Spilling the Tea

• Reflecting on the Oka Crisis Gentrification in Tiohtià:ke

Commentary 11

Indigenous Languages at McGill Dessert Horoscopes!

Call for Candidates

All members of the Daily Publications Society (DPS), publisher of The McGill Daily and Le Délit, are cordially invited to its Annual General Assembly:

Wednesday, October 1st @ 6:00 pm

McGill University Centre, 3480 Rue McTavish, Room 107

The general assembly will elect the DPS Board of Directors for the 2025-2026 year.

DPS Directors meet at least once a month to discuss the management of both Le Délit and The McGill Daily and get to vote on important decisions related to the DPS’s activities.

The annual financial statements and the report of the public accountant are available at the office of the DPS and any member may, on request, obtain a copy free of charge.

Questions?

Send email to: chair@dailypublications.org

editorial board

3480 McTavish St, Room 107

Montreal, QC, H3A 0E7

phone 514.398.6790 fax 514.398.8318 mcgilldaily.com

The McGill Daily is located on unceded Kanien’kehá:ka territory.

coordinating editor

Andrei Li managing editor

Sena Ho news editor

Adair Nelson commentary + compendium! editor

Ingara Maidou culture editor Isabelle Lim

Youmna El Halabi features editor

Elaine Yang science + technology editor

Vacant sports editor

Vacant video editor

Vacant visuals editor

Eva Marriott-Fabre

Nikhila Shanker copy editor

Charley Tamagno design + production editor

Vacant

social media editor

Lara Arab Makansi radio editor

Vacant cover design

Sena Ho staff contributor

Mara Gibea, Enid Kohler, Aurelien Lechantre, Auden Akinc contributors

Karonhia'nó:ron Dallas CanadyBinette, Zoe Sanguin, David Farla, Emma De Lemos, Miranda Forster, Anthony Hayek, Eva Moore, Jemima D’Sa

Published by the Daily Publications Society, a student society of McGill University. The views and opinions expressed in the Daily are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of McGill University. The McGill Daily is independent from McGill University.

3480 McTavish St, Room 107

Montreal, QC H3A 0E7 phone 514.398.690 fax 514.398.8318

advertising & general manager

Letty Matteo ad layout & design

Alice Postovskiy

Contentwarning:genocide.

Language is inherently human. Being able to articulateourthoughtsiswhatdistinguishesusfrom animals. Language is a tool to foster communities and shape identities.

When one sets out to learn a new language, one is usually encouraged to partake in a variety of activities in order to improve.Wearetoldtolistentomusicsunginthattongue,read itsbooks,watchitsmovies,orpracticewithnativespeakers to perfect the language. What do these actions have in common? They’re grounded in cultural customs – because language is inherentlycultural.

When your mother tongue is suppressed, and you are forbidden to speak your own language, you are subject to culturalerasure.

TheFirstNations,Inuit,andMetisPeopleshavealwaysrelied on oral communication and storytelling to impart wisdom and preserve history. Storytelling in particular is a traditional method that is used to teach cultural beliefs, values, customs, history,andwaysoflife.

According to First Nations Pedagogy Online, “First Nations storytelling involves expert use of the voice, vocal and body expression, intonation, the use of verbal imagery, facial animation, context, plot and character development, natural pacing of the telling, and careful authentic recall of the story.” First Nations, Inuit, and Metis stories are essential to relaying historical or sacred narratives, as well as the socio-political practices of the community. One can only imagine how much historyislostwhenelderslosethisabilitytocommunicatewith youngergenerations.

Thisisawaycolonialismdestroysnations.Whenoneismore concerned with mastering the colonizers’ languages, like English or French, they are eventually forced to abandon their cultural identities. However, we cannot blame the victims of colonial erasure for their need to assimilate and thrive in an environment where the dominant language is not the one

spokenbytheirancestors.Attheendoftheday,humansrequire community.Speakingthecolonizer’slanguagebecomesameans ofsurvival,especiallywhenitimposesitselfinallaspectsofour lives,beitacademic,professional,andevenpersonal.

The Canadian government’s efforts at pursuing truth and reconciliation have remained performative and empty. Land acknowledgements are made at public events or plastered all over government and university websites. Truth and Reconciliation Day is marked by orange t-shirts and public speeches from the government, but after October 1, it’s back to counting down the days until Thanksgiving: another dark day fortheIndigenouscommunity.Yettheseefforts failtopreserve anintegralpartofIndigenousculture:language.

In 2019, the government of Canada passed the Indigenous Languages Act in an attempt to promote and revitalize Indigenous languages. However, the impact of this legislation has been mostly symbolic. The province of Quebec insists on preserving its Francophone culture by implementing The Charter of the French Language, conveniently forgetting that Quebec is on unceded Indigenous land, with Kanien’kéha initially being the land’s native tongue. French lessons are offered by the government, and universities like McGill are reducing tuition for students who take French classes. Yet Indigenous languages are hardly as accessible, forcing yet anotherbarriertoIndigenousculturalpreservation.

ThisNationalTruthandReconciliationDay,wemustdomore thanjustacknowledgethelandonwhichwereside.Wecannot merely offer empty apologies for the genocidal crimes that led toCanada’sestablishment.Weallmustrecognizethestructural repercussions of the ongoing colonial project which have destroyedFirstNations,Inuit,andMetiscommunities.Wemust commit to long-term actions in preserving Indigenous culture, and pushing for more accessible opportunities to learn Indigenouslanguages.

Indigenous history lies in stories told, and it is our duty to learnthelanguagesinwhichtheyweremeanttobeheard. Read

www.mcgilldaily.com www.facebook.com/themcgilldaily @themcgilldaily @mcgilldaily

CONTACT US

managing@mcgilldaily.com visuals@mcgilldaily.com visuals@mcgilldaily.com radio@dailypublications.org copy@mcgilldaily.com socialmedia@mcgilldaily.com

Mara Gibea Staff Writer

On September 9, Montreal

Mayor Valérie Plante announced five metro stations that Société de transport de Montréal (STM) is expected to open and be completed by 2031, known as the Blue Line project. This plan follows the Quebec government’s pledge to revitalize the East of Montreal past the corner of Jean-Talon Street East and Viau Boulevard. The stations’ names call to strengthen collective memory, particularly the legacy of Mary Two-AxeEarley,whowillhavea station named in her honour as an activist for the rights of Indigenouswomenandchildren.

“Naming a station for Mary Two-Axe Earley is a good step,” wrote Mia Alunik Fischlin to The McGill Daily, the Administrative Student Affairs Coordinator in the Indigenous Studies Program at McGill (MISC). “Hearing powerful Indigenous names in daily life matters,” she continued.

“It reminds people that these are Indigenous places and that Indigenous women and Peoples fought for their rights.

”

Mary Two-Axe Earley was a member of the Kanien’kehá:ka nation (Mohawk), born in Kahnawà:ke, which is located on the southern shore of the St. Lawrence River. This is the easternmost point of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, of whichtheKanien’kehá:kaPeoples are the “Keepers of the Eastern Door.” At the age of 18, Two-Axe Earley relocated to New York City, despite being separated by the colonizer-determined Canadian-American border. She then lost her “Indian Status” in 1938 upon marrying her nonIndigenous husband, Edward Earley. According to Section 12(1)(b) of the Indian Act of 1876, Indigenous women who married non-status spouses lost their status of Indigeneity and could notpassitdowntotheirchildren. Additionally, Indigenous women could lose their status upon divorcing their husbands. This was not true for Indigenous men with non-status spouses. This is because status was inherited patrilineally, rendering Indigenous women statusdependent on Indigenous men to “displace our matriarchs and destabilize our society,” writes

Dr. Wahéhshon Whitebean to The McGill Daily, a Wolf Clan Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) scholar and professor in MISC at McGill.

“We pass our identity and citizenship through our matrilineal Clans,” states Whitebean. “Status is manufactured and determined by the colonial state and imposed on us to undermine our traditional Haudenosaunee Clan System,” she says, which is particularly evidentintheinstitutionalization of Indigenous women’ s disenfranchisement.

Losing status meant losing distinct legal rights to Band Council membership, treaty benefits, and reserve property ownership.

According to the Montreal Gazette, Two-Axe Earley’ s activism was prompted by the death of a close friend, Florence, who was unable to return to Kahnawà:ke after losing her status and property. In 1967, the same year the Royal Commission on the Status of Women (RCSW) was established, Two-Axe Earley founded Equal Rights for Indian Women (ERIW), a provincial organization that later evolved nationally into the Indian Rights for Indian Women (IRIW). The timingoftheRCSW,whichcalled for the amendment of the Indian Act to allow Indigenous women to keep their status and pass it down to their children, was an objective shared by the IRIW. Two years after the commission, Two-Axe Earley returned to Kahnawà:ke with her daughter, who had gained status from her Kanien’kehá:ka husband and could thus own housing on the reserve. There, Two-Axe Earley continued her activism as a founding member of the Québec Native Women’s Association (QNW) in 1974.

“My grandmother [Millie, who was stripped of her status] was part of these movements and joined meetings with Mary TwoAxe Earley,” recalled Dr. Whitebean. “She spoke highly of her, and as a result, I grew up thinking of her as a hero for fighting against one of many inequalities that Indigenous women face in our lifetimes,” added Whitebean. This perception of Two-Axe Earley was shared by many, as her work spread internationally in 1975 when she and 60 women from Kahnawà:ke attended the International Women’s Year

conference in Mexico City. Duringthistime,theKahnawà:ke Band Council sent eviction notices to the Kanien’kehá:ka women participating in the conference, which were repealed when Two-Axe Earley publicly revealed the discriminatory nature of these actions at the conference. The council’s actions are examples of “what colonialism does,” which, according to Dr. Whitebean, “[destabilizes] communities and destroys relational bonds,” as “[the] pain and struggle [Whitebean’s grandmother] endured was mainly at home, inflictedbyherownpeople.” This is still apparent now. For example, the Quebec Superior Court ruled the Kahnawà:ke Band Council’s membership law, known as the “marry out, stay out” policy through which Indigenous residents with nonIndigenous spouses were evicted from the Kahnawà:ke reserve, as aCharterofRightsandFreedoms (Charter) violation in 2018. Nonetheless, Two-Axe Earley and Dr. Whitebean’ s grandmother Mille “remained on the reserve through all of the tensions and violence.” Moreover, “[m]any people do notrealizethatitwasatleasttwo decades of advocacy and activism at local, regional, national, and international stages that built enough momentum to push those changes through the legislature,”

reflected Dr. Whitebean. In 1982, Two-Axe Earley’s activism pressured the federal government to address the discrimination First Nations womenfaced.Thiswasdonewith the support of Quebec’s former Premier René Lévesque, who at the First Minister’s Conference, gave his seat to Two-Axe Earley after she was denied time to speak. The conference regarded the inclusion of “Aboriginal and treaty rights” into the patriation of the Canadian Constitution in 1982 and its protection in the CanadianCharter.Today,Section 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982 guarantees these rights for all Indigenous Peoples, including women, as stated explicitly in subsection 4. Nonetheless, Section 12(1)(b) of the Indian Act remained in place. Ultimately, it was in 1985, with Bill C-31, that the section was amended. That same year, at the age of 73, TwoAxe Earley became the first Indigenous woman to have her status reinstated and was awarded the National Order of Quebec for making contributions of the highest order to the province’s development. It is important to note, however, that many Indigenous women and children did not regain their status following the amendment. It took until 2011 for Bill C-3 to reinstate status to thoseafterthesecond-generation cut-off where third generation

children don't hold status despite being Indigenous after two previous generations of parents lost their statuses and until 2017 for Bill S-3 to grant status to the grandchildren of the Indigenous women who were reinstated. According to the Government of Canada, “[w]ith the full enactment of Bill S-3 on August 15, 2019, all known sexbased inequities have been eliminated from the Indian Act.” These amendments are a result of decades of activism pioneered not only by Two-Axe Earley but also by Jeannette Corbiere Lavell, Yvonne Bédard who challenged Section 12(1)(b) at the Supreme Court of Canada, and activist Sandra Lovelace. “Although these legislative changes were a [product] of collective activism,” wrote Dr. Whitebean, “they also required personal sacrifice.” Thus, names like Mary Two-Axe Earley “should be raised up,” especially since many governmentsubsidized public spaces “ are named after colonial settler men or religious figures.” Dr. Whitebean reminds us that “[t]here is power in naming”; the metro stop named in Two-Axe Earley’s honour represents “the power of Indigenous women and Kanien'kehá:ka matriarchs.” These efforts have not ceased; Whitebean affirms, “we're still here fighting for our future generations.”

David Farla | Visuals Contributor

Since the new bill on forestry was tabled, protest has risen from First Nations authorities and environmental groups. Good People

Aurelien Lechantre Staff Writer

The Green Update is a bi-monthly/ monthly column focusing on recent inforelatedtoclimatechangeandthe environment. Innovations, policy decisions, green models to follow, anything that can shape our future environmentcanbediscussedhere!

Author’snote: Bill97wasabandoned byLegault’sgovernmentonSeptember 25.Thisarticlewaswrittenpriortothe government’s decision. This reform proves the importance of uplifting Indigenous and environmentalist voicestoprotectourland.

In April 2025, Quebec Minister of Natural Resources and Forests

Maïté Blanchette-Vézina pushed forwardBill97,alargereformaimedat Quebec forestry, arguing it would modernize the forestry regime and be moresustainableinthelongterm.The Actproposedtoreformsupplylicenses fromfiveyearsofvaliditytotenyears, claimingthatit wouldallowformore sustainable approaches by encouraging longer term investments from forestry exploitation actors: having a longer license, they will by defaultlookfurtherinthefuturewhen drafting exploitation regimen. Bill 97 also granted more flexibility to local actors to adapt to the local factors moreefficiently.Themaincomponent of Bill 97, titled “An Act mainly to modernize the forest regime” is its introduction of the ‘triad-zoning model.’ It would divide Quebec Forestryintothreezones:conservation areaswhereloggingisstrictlylimited, multi-purpose areas which allow for tourism and other activities alongside forestexploitation,andfinally “priority forest-development zones” meant for intensetimberexploitation.

However, Blanchette-Vézina’ s bill was met with much resistance. The only ones who who have approvedofthegovernment’sbillare theindustrialistsoftheforestry,with the Quebec Forest Industry Council claiming it offered more predictability while still blaming it forbeing “tooprescriptive” according to the President of the Conseil de l'industrie forestière du Québec, Jean-FrançoisSamray.

As soon as the bill was released, First Nations representatives contested it. Regional Chief Francis Verreault-PauloftheAssemblyofFirst Nations Quebec-Labrador (AFNQL) said Bill 97 was both “extremely surprising and disappointing.” Recommendations made by the Indigenous representatives were not considered at all and Lucien Wabanonik, chief of the Lac-Simon Anishnabe Nation, even called the proposal “aninsulttoourintelligence.”

Indigenous student-led project looks at the sites McGill University occupies through an anti-colonial lens.

Indeed, not only did the Minister ignore her constitutional duty to collaborate and concert with IndigenousPeoplesinthedraftingofa bill that directly affects their lives, livelihoods, and ancestral lands, she also drafted a bill that places the industry above Indigenous rights. Chief Wabanonik explains the bill authorizestraditionalactivities “onlyif theydonotharmlogging,” showingthe little consideration this bill, and the wayitwaswritten,hasforIndigenous Peoples’ rightsandancestrallands.

The “triad-zoningmodel” planned to grant at least 30 per cent of public forestry in all of Quebec for exclusive exploitation by the industry by 2028. This is not taking into account the ‘multi-use’ zoneswhereloggingisalso permitted alongside other activities. Because of this, the AFNQL has accusedthegovernmentofprivatizing nearly a third of First Nations territoriesforindustrialinterest. This not only impacts traditional and legal rights of the First Nations, but also the survival and livelihood of communities in addition to the preservation of the environment. While Quebec’s forestry is already more fragile than ever, the Bill places industry over conservation of its natural forests, which have already been compromised as authorities currently authorize clear-cutting far toooften.Furthermore,theincreaseof industrial exploitation will mean the increase in monoculture, which is the directlossofbiodiversityandexposure of the forest to increased risks of fire anddisease.

Alongside the AFNQL’ s immediatecondemnationofBill97,the MAMO/MAMU alliance of several Indigenous nations took up protest and blocked forest exploitation by writing letters of expulsion to 11 forestry companies. Environment activists and First Nations members actively protested, even in the streets of Montreal-South. The Cree Nation government also threatened to take legalactionusingthe “PaixdesBraves” agreement of 2002. This legally binding treaty protects Cree rights, obligating the Quebec Government to consult them before developing or usingIndigenouslandsintheNorthof the province. After the Quebec Ministryconcededtolookatproposed amendments over the summer, the AFNQL demanded the complete withdrawalofBill97.Theonlysolution would be to draft a bill alongside the First Nations and conservationists, as Chief Verreault-Paul stated, “Only through the full withdrawal of Bill 97 and by returning together to the drawingboardcanwebeginatruecoconstruction legislative process and envision a balanced future for our forests, while reducing the tensions currentlyobservedontheground.”

Enid Kohler Staff Writer

GoodPeopleisabi-monthlycolumnhighlighting McGillstudentsdoingcommunity-orientedwork onandaroundcampus.Becauseit’simportantto celebrategoodpeopledoinggoodthings.

Margaret MacKenzie is a 2024 McCall MacBainScholarpursuingaMasterofArts in Educational Leadership at McGill University. She is a citizen of the Métis Nation, British Columbia and is the Indigenous Outreach Program advisor for Branches, McGill’ s Community Outreach Program. Margaret worked alongside a team of Indigenous researchers at McGill to create the Critical Campus Tour: an evolving project that launched in 2023. The tour, facilitated by Indigenous students and graduates, visits select sites on McGill’s campus to critically engage with their history and significance. The Daily spoke with Mackenzie about the tour, the importance of community, and why knowledge shouldevolveratherthanremainstatic.

This interview has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

Enid Kohler for the Daily (MD): How did the CriticalCampusTourcomeabout?

Margaret Mackenzie (MM):Itstartedwiththe ParticipatoryCulturesLab,whichisintheFaculty ofEducationandisrunbyDr.ClaudiaMitchell.In 2023, I was an intern in her lab as part of the IMPRESS program (Indigenous Mentorship and Paid Research Experience for Summer Students) andmytaskwastoformalizethetour,toaddmore spots on the tour, and then to digitize it. That September, we ran the tour for the first time inperson,attheWeWillWalkTogetherEvent.There were three tour groups, each about 15-20 people. Lastyear,theturnout inmygroupalonewashuge – therewereprobablyover100people.

Basedonthefeedbackfromour2024tour,Ihave been working with other students to continue workingonthetourandmakeitmoreconcretefor thefuture.

MD: If you were pitching the Critical Campus Tour to an educator in a nutshell, how would you describeit?

MM: It's to look at McGill's campus in an anticolonial and truth-seeking lens. It's also about engagingwiththesitesandmonumentsatMcGill that you walk by everyday, which actually have a deephistoryormeaningbehindthemthatwedon't payattentiontoorrecognize.Thetourissupposed to provide a basis for critical conversation, discussion,andreflection.Thetourguidegivesyou some points to consider and then you have what canbeuncomfortableorchallengingconversations. Youneedtoshowuptothistourreadyandwilling todothat.

This tour is also about uplifting and shedding lightonallthehardworkthatIndigenousstaffand studentsaredoingoncampus.Oneofmyfavourites is Projections: Kwe in the Faculty of Engineering building, which was an Indigenous student group out of the Faculty of Engineering that put up this really cool art display in the lobby. So things like thataswell,justupliftingandprovidingaplatform forreallyamazingworkoncampus.

MD: You mentioned digitizing the Critical Campus Tour. What is your vision for how the projectwillevolveinthefuture?

MM:We’vebeentryingtoshare[thetour]with professorsandstudentstohaveitbeaccessible,so that it’s available on days other than just September30.That'swhywe'retryingtomoveit to a digital platform, because all the information and all of what we would say on the tour is now online. So you can do it yourself. There’s also a maptoguideyou.

We really hope that it's a useful resource for classesandforgroupsoncampus,justtocontinue thelegacyofhavingthistourrunbecauseithasso muchinterestinginformation.Alotofitgetsswept undertherug.Sojusthavingpeoplebemoreaware andusingitindifferentspaces.

I also want to emphasize that the Critical Campus Tour is definitely not just my work; I’ m one piece but it’s been many, many people who have worked on this. (Emilee Bews, Samantha Nepton, Sarah Boyer and Rune Hartgerink are Mackenzie’sprimarycollaborators.)Thetouralso getsrevisedeveryyear.It’slikealivingdocument.I hopethatitcontinuestogrowandchangesinceit's not meant to stay the same. We hope that other students will do more work [on the project] and continueit.

MD: What is your relationship with McGill’ s Indigenouscommunitylikeandhowhasitchanged since participating in the IMPRESS program and startingtheCriticalCampusTour?

MM: I'veneverseenmyselfassomeonetodoa Master's. That was never really in my plan. I just waslike, ‘OK,I'mgoingtobeateacher.’ Andthen after I did IMPRESS and research, my mentor Emilee Bews – who was also an undergrad at the sametimeasmeandinthesameprogram – really encouraged me to apply to the McCall McBain program. She was like, “just do it.” And I wasn’t sure. But Emily really pushed me. And then I decidedtodoaMaster's.AndthroughmyMaster's, I’m so lucky to do Indigenous centered research, which is really, really incredible. And I'm really grateful.Ifullychangedmytrajectory.

Working with and supporting Indigenous students in higher education also really changed howIseewhatIwanttodointhefuture.It'sbeen afullcircleexperience.I'mso,sogratefulforallthe experiencesthatI'vehad.

MD: The theme of this column is “good people doinggoodthings.” Inthecontextofyourresearch andworkwithotherIndigenousscholarsatMcGill, whatdoesbeinga “goodperson” meantoyou?

MM: Well, for me, it's just supporting my community.It’snotaboutmyself.Ithinkit'sreally about uplifting the voice of my community and strengthening my community. And following our valuesanddoingeverythingwithagoodheartand goodintentionsisreallyimportanttome.

I've been so grateful to have so many amazing opportunities. And I just want that also for my community.

Thedigitalversionofthe2025CriticalCampus Tour will launch at the We Will Walk Together EventonSeptember30.Studentscanfindoutmore about the project and McGill’s Indigenous communityandhistorybyattendingtheevent.

Charley Tamagno

Copy Editor

On September 17, the 24th annual McGill Powwow kicked off Indigenous Awareness Week. Hundreds of Indigenous people and allies from around the Montreal area and beyond gathered upon Macdonald campus ’ field to celebrate Indigenous culture and resilience in the face of hundreds of years of persistentdiscrimination.

Combining forces with John Abbott College, the Powwow was moved off of McGill’s downtown campus for the first time. Situated on Watson Field at McGill’ s Macdonald campus, a monstrous white tent sheltered hundreds of peopleclusteredaroundthecenter stage, enraptured by colorful regalia and thundering drums. Toddlers, teenagers, and adults alike took to the stage in small groups,competingforprizemoney in various traditional dances. Vendor tents dotted the field surrounding the tent, selling Indigenous artwork, jewelry, and promoting services for the Indigenous community in the

greaterMontrealarea.

The change of venue took the event out of the Tomlinson Fieldhouse and helped smooth its transition from an exhibitionary format with no prizes, towards a traditional powwow in which the dancers compete for prize money andbraggingrights.

“It’s easier for the dancers and the vendors coming with equipment and setups, parking there’s not as much construction,” comments Kim Tekakwitha Martin, Dean of Indigenous Education at John Abbott College. “But also, it’s being able to utilize this wonderful space that we have oursharedcampuseson.”

Martin worked alongside McGill’s Indigenous Initiatives Office to provide the opportunity for students to engage in this cultural experience on campus. Notonlywasitherfirsttimebeing abletoattendtheMcGillPowwow, but the new venue extended the opportunity to other John Abbott and Macdonald campus students, and various communities closer to the West Island that might have typically been too far to attend the powwow before. “It’s the 24th

annual McGill Powwow but this is the first annual McGill x John Abbott Powwow I think that it will be something that will continuebecauseitreallyhasbeen awonderfulexperience.”

While the two schools sharing a campus have the occasional collaboration, such as the weekly Mac Market publicized at John Abbott,andotherprograms,thisis a stride towards organizing larger eventstogether.

Martin remarked that powwows typically come out of harsh times within an Indigenous community. Kahnawake, where she is from, beganhostingtheannualEchoesof a Proud Nation powwow after the 1990OkaCrisis.

In Martin’s words, the event serves to celebrate Indigenous resilience: “That was to signify the community coming together, and whatwehaddone,andthatweare aproudnation.” Al Harrington, of the Ojibwe people of northwestern Ontario, competed in the men’s 18+ traditional dance. Taken from his cultureandhomeduringtheSixties Scoop, he was unable to connect and learn his roots until he turned

Anthony Hayek Sci+Tech Contributor

Recently,Iranintoareelthatone of my friends reposted, claiming it described a “herbal cure ” for cancer. I watched a little more of the video, but when the creator described cancer as being “ a parasitethatentersyoursystem,” my lil’ nerdbrowwasinstantlyraised.So Irepliedtomyfriend’srepost,asking herifshebelievedwhatthereelwas saying.Oddlyenough,tomeatleast, she said she did and hoped this repostreachedsomeonewhoneeded it. I then spent the next five to ten minutes ranting to her about how thiswasflagrantmisinformationand explainingtoherwhatcancerreally is.Afewdayslater,Iranintoavideo of a podcast where two dudes were sayingmatchacuresbreastcancer. We’veallheardofcancer.Butwhat isit,atacellularlevel?Ourbodiesare madeupofcells:insideanormalcell lies a nucleus, a little ball-like structure, whose main purpose is to protect the cell’s most basic instructions, its DNA, from the extranuclear environment, which containsanamalgamofenzymesand proteins or other structures, both extracellular and intracellular, that could possibly damage it. The cell uses these instructions to build its machinery: proteins. Some of these proteins can act as guideposts, providing the cell with the tools to

detectwhenandhowtodivide. However, sometimes the cell can make mistakes. Sometimes, external factors, such as UV radiation or tobaccosmoke,canalsodamagethe DNA, causing it to mutate. Thankfully, the cell is prepared for these kinds of scenarios and has many mechanisms to either repair theDNAorfixitsmistakes.However, thesemistakesmayattimesgounder theradar.Ifthosemistakeshappenin the instructions on how to divide your cells, you get cancer. Examples ofthisphenomenonarewhatwecall tumour suppressor proteins. These are a category of sub-cellular machinery responsible for telling your cell, “this is not the time to divide.” An example of this type of protein is a protein called p53 (protein number 53). When a mutation happens at the level of these proteins, they can be in a “permanently off” state, which is known as a loss-of-function mutation. When this happens, the cell loses its “ no-go ” signal, so it thinks it's always the right time to divide, which is not what it's supposed to think. This drives it to divideinunfavourablesituationsthat couldcauseittoevenfurtherdamage itsDNA.

Theaforementionedp53proteinis socrucialtothisprocessthat60per cent of colorectal cancer cases contain tumours with a damaged p53. On the flip side, you have

18.In2009,hebegantoorganizehis own powwows, including facilitating the annual springtime Montreal Powwow until 2020. Working to break the cycle of Indigenous disenfranchisement, Harrington runs cultural workshopsintheMontrealareaand has his children enrolled in a Mohawk immersion school in Kahnawake.Hischildrenhavebeen raised speaking Mohawk, Ojibwe, English,andFrench.

“They know their culture,” he said,withanairofdetermination.

What is cancer, and why is it so hard to cure?

oncogenes,whicharethecell’ s “keep going” signal and sometimes mutations on these proteins can cause them to be constantly on or evenoverproducedinthecell.Allof these distinct damaged instructions have the same end result of producing an abnormally dividing cell.Andthisisafairlyboiled-down way of how a cancerous cell develops; in reality, there is much morethathappensunderthehoodat even the most microscopic parts of your cells. Even when this happens, your body has so many failsafes in place to defend itself from these mutatedcells.Forinstance,cellswill often recognize that they’ ve gone rogue and self-destruct in a process known as apoptosis. Unfortunately, these mechanisms may also fail due to a plethora of factors: genetic variance between individuals, the nature of the damage to the DNA, immune health, work environment, andsoforth.

When these “mistake” cells begin to propagate, that’s when you get tumour development. Cancer happens when your cells start dividing too much and in ways they’renotsupposedto.

Why has cancer been so notoriously hard to cure? The fundamentalnatureofcanceriswhat makesitsohardtotreat.Astumours start, they are similar in makeup to your body’s healthy cells, and they maintain some aspects of the

microscopic appearance of those cells. Targeted therapies are therefore harder to engineer since you do not want to damage your healthycells.

What muddies the waters even moreisthephenomenonoftumour heterogeneity: two tumours don’t always have the same “messed up instructions.” Sometimes, even in the same tumour, you can have the accumulation of multiple different cells, each with different “messed upinstructions.” Thismakesithard to produce a “one size fits all” drug forcancer.

Despite these challenges, many cancer treatments have been developed. Chemotherapy is composedofabroadrangeofdrugs, but fundamentally, all work on the same principle: targeting and killing any cell that divides and produces other cells really quickly. Unfortunately, this also affects healthy tissues that divide rapidly, like a patient’s hair, for example, which is made of very rapidly regenerating cells. This is precisely the reason why chemotherapy patientslosetheirhair.

Another commonly used treatment is radiotherapy (or radiation therapy), which works by blasting cells with high-intensity radiation until they die. This could affecthealthycellsinadditiontothe cancerous ones, yet the use of highprecision radiation beams mitigates

this effect somewhat. Other treatments do exist, but they are specific to unique cases of a particularcancer.

In essence, cancer is hard to cure becausecancerouscellsaresimilarto our own cells, acting like impostors inourbodiesthatareverydifficultto separatefromhealthycells.Although treatmentsdoexist,theyeitheractas general “cell killers” or are often administered on a very case-by-case basis and require extensive evaluationfromprofessionals.

Isabelle Lim Culture Editor

Nestled between Rue St. Catherine and Rue St. Laurent is the Centre des Mémoires Montréalaises (MEM).

In the lobby on the second floor, you ’ll see a large road sign displaying Rue Amherst’ s renamingtoRueAtateken,moving away from its colonial origin of JefferyAmherstwho,accordingto the accompanying description, wished smallpox upon Indigenous communities. In contrast, “Atateken” is a Mohawk term loosely translated as “sisters and brothers,” emphasizing values of friendship and collaboration. This display is just one of many references to Indigenous culture sprinkledaroundtheMEM.

According to their website, the MEM “place[s] citizens’ voices at the heart of their actions.” They aim to “share authentic local histories” and “reflect Montreal’ s diverse realities” in order to “facilitate responsible, sustainable cohabitation.” This is done through innovative exhibitions, which include first-hand accounts and artifacts from various time periodsandcommunities.

Said communities, of course, include the First Nations people, who have lived on the island of Montreal and in Canada at large for hundreds of years. According to the MEM’s permanent exhibit, “Montréal” (the Greater Montreal area) was home to an Indigenous population of over 4 million in 2016. Through its mission, the MEMplaysaroleinpreservingthe memories of the Indigenous, who havebeenherelongerthananyone else, and thus have the richest history in Montreal, even if much of it remains buried, undocumented,orevenneglected.

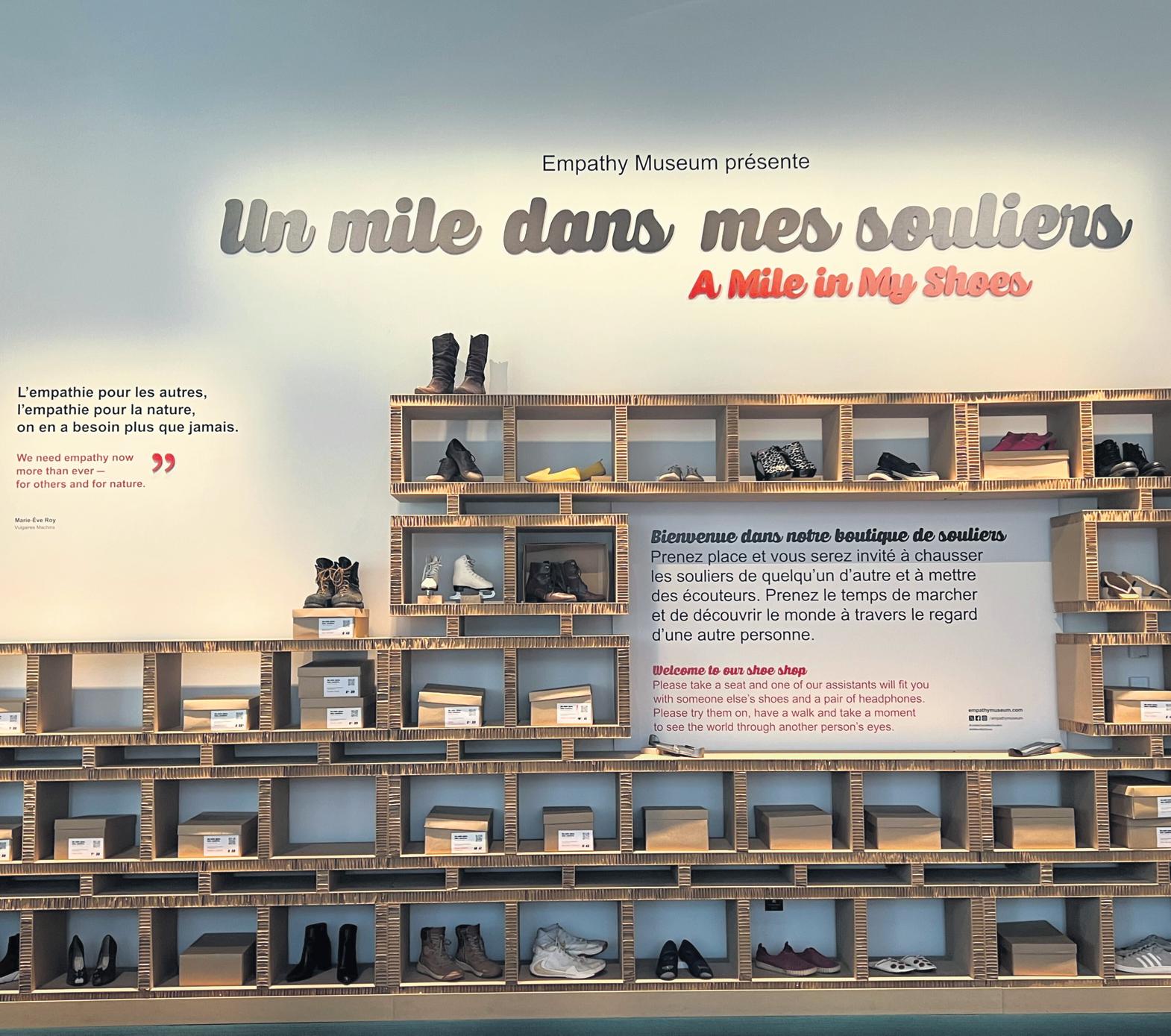

Indigenous memory is layered with stories of loving community, as well as immense trauma. Many Indigenous people carry the weight of intergenerational suffering on their backs, with family members having faced discrimination at best and unimaginable abuse at worst. In the temporary exhibition that ended on September 21 titled “A Mile In My Shoes” a collaboration between the MEM and the Empathy Museum, visitors are givenapairofshoesbelongingtoa storytellerwiththesameshoesize, which they are encouraged, but not forced, to wear, along with a pair of headphones and an audio device to listen to the owner’ s story. The exhibit is designed to instill empathy in the visitor by being given a tangible symbol of the storyteller’s real existence.

This exhibit included shoes and stories from Montrealers of various demographics, including thoseofIndigenousbackground.

As one of the storytellers in “A MileinmyShoes,” InnupoetMaya Cousineau Mollen, represented by aneclecticpairofboots,speakson the trauma she faced as an Indigenous child raised by her adoptive white parents, and the uneasy feeling of never being enough for either side. These themes of cultural upset are echoed by bead artist and seller Oskenontona Philip Deering, whose story is represented in this exhibit by a pair of brown sneakers. Deering discusses the abandonment of his Indigenous name in his youth which is representative of the grey area Indigenous people often occupy between their native identity and thecolonisedworldwelivein.

Thisculturaldissonancepersists to this day. Montreal and McGill University continue to occupy

unceded Indigenous territory, the landscape of which has been and continues to be drastically altered by urbanization. Another exhibit, “Detours - Urban Experiences,” is animmersiveexperiencefeaturing short video clips of various Montrealers sharing their life experiences. In one of these videos, Indigenous radio host and activist Melissa Mollen Dupuis bringsacameramanaroundMontRoyal, which she describes in the footage as “Montreal’s lung.” As developmentprojectsencroachon natural spaces worldwide, Dupuis illustrates the importance of preservingMont-Royalnotjustfor environmental reasons, but to maintain the enduring connection between Indigenous people and nature, especially considering Mont-Royal’s status as an importantgreenspace.

In the hustle and bustle of globalization, where the frontiers between cultures and continents grow increasingly blurred, we

cannot afford to neglect Indigenous narratives, which extend far beyond our collective consciousness. Cousineau Mollen states, in the English dub of her recording in the exhibit, that she wouldlikepeopleto “findawayto behappyinsocietytogether.”

As inhabitants of their land, we must make an effort to uplift the sorrows and joys of Indigenous people,ensuringthattheyareseen not only as victims but as fighters. In historically resisting and continuingtorallyagainstsystems that continually oppress them, Indigenous experiences are powerful markers of the importance of community and resistance, which we must seek to uplift. After all, the Indigenous people are not just memories –theyarestillhere.

FindoutmoreabouttheMEMat theirwebsite.Ticketsforstudents are$10.90.

Montreal and McGill University continue to occupy unceded Indigenous territory, the landscape of which has been and continues to be drastically altered by urbanization.

Karonhia'nó:ron Dallas Canady-Binette Culture Contributor

At the beginning of the Fall 2025 semester, McGill students were greeted by the sight of a new mural on the university’s lower campus,inbetweentheRoddickGates andtheArtsBuildingattheso-calledYIntersection. As a returning student myself,Iwasanxioustoseewhatthe murallookedlike.Foranentireyear,I walkedpasttheclosed-inconstruction site and attempted to spot what was goingonbehindthetall,tarpedfences.

When the Y-Intersection renovations would come up as a topic of conversation,Irealizedthatmypeers, andevensomeofmyprofessors,hadno ideawhatthepointoftheprojectwas.I would answer them with the simple statement, “They’re Indigenizing the Y!” But even I didn’t fully know how constructioncouldbe ‘Indigenizing’ OnthefirstdayIreturnedtocampus inSeptember,Iwonderedifthemural was finally complete. I didn’t see any kind of social media post, journal article, or email celebrating its unveiling. I walked from University Street towards the Arts Building and unceremoniously stumbled upon the installation. The mural is circular and laid into the ground, made from differentkindsofblackandgreystone.I noticed a number of symbols, though they were difficult to see through the

masses of people walking across the mural and the relentless sunlight beating down from above. With some squinting, I recognized the traditional clananimalsoftheKanien’keha:ka:the bear,wolf,andturtle.Beyondthat,what I saw were the generic silhouettes of plantsandpeople.

As I looked around for a commemorativeplaquethatexplained thesymbolismofthemuralortheintent of the artist who made it. There was none.Idecidedtositononeoftheeight benches surrounding the mural and watch how the public interacted with the piece. I observed hundreds of pedestrians pass through the intersection, never stopping to inspect the change beneath their feet. Some touristswalkedoverthemuraltotake pictures of the Arts Building, adorned withMcGill’sredmartletflag.Myheart sank.Ileftdisappointedbutdetermined tofindoutmoreaboutthemural.

Ten years ago, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) publisheditsFinalReportonthehistory and legacy of Indian Residential Schools in Canada. The report found that the government of Canada was responsibleforthephysical,biological, and cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples. Included in the Final Report were94CallstoActionthatCanadians, atalllevelsofsociety,couldtakeupto address the injustices faced by Indigenouspeoples.

A number of these Calls to Action

concerned making education more equitable and accessible for Indigenous peoples. Heeding these calls,ataskforceledbyProvostandVP Academic Christopher Manfredi publisheditsownreportonthestatus of Indigenous studies, Indigenous education,andreconciliationatMcGill University in 2017. This report includeditsownCallstoAction,with the Y-Intersection mural directly linked to Call #26: Indigeneity and PublicSpacesatMcGill.Here,thetask force recommended that the University establish a dedicated fund tobuyanddisplayartfromIndigenous artists and to “embed Indigenous themesinourpublicspaces.”

According to McGill’s Office of Indigenous Initiatives (OII), the redesignoftheY-Intersectionismeant to “createafunctionalgatheringspace that challenges Western ways of thinking by thoughtfully integrating Indigenous worldviews, art, and culture throughout the space” with a specific emphasis on Kanien’keha:ka themes. The project was done in collaboration with Morningstar Designs,alsoknownasAlanahJewell (OneidaoftheThames),althoughit’ s not confirmed if she designed the mural, the benches, or both. Unfortunately,thisinformationisonly availableonawebpagenestleddeepin theOII’swebsite.

Themural,whichisauniversity-led initiative,standsinstarkcontrasttoan

Indigenous-led initiative that was attemptedayearearlier.OnNovember 18th,2024,acoalitionofwomenknown as Kanien’keha:ka Konnon:kwe, including prominent Kanien’keha:ka activists Katsi’tsakwas Ellen Gabriel and Kahentinetha Horn, gathered on McGill University’s lower field. Here, the women held a ceremony to commemoratetheplantingofawhite pine sapling, recognized as an important symbol of peace for the Rotinonshion:ni (Six Nations). The tree, which was planted near the former student encampment for Palestine, called for peaceful relations betweenMcGillstudents,theuniversity administration, the Kanien’keha:ka, andthePalestinianpeople.

Manfredi and VP Administration Fabrice Labeau were informed over emailofthewomen’sintenttoplantthe tree two weeks in advance. They responded that McGill would not be participatingintheceremony,andthat the university only carries out reconciliation efforts in partnership with “traditionalandelectedleadership of local Indigenous communities.” An additional email from Manfredi and LabeaustatedthattheKanien’keha:ka women were not authorized to plant the tree on McGill’s property, despite the fact that these women, under the traditional governing structure of the Rotinonshion:ni, are the sole titleholdersoftheland.

Students remained on campus to

watch over the tree until 11:00 p.m. when the university closed to the public. By morning, the tree had disappeared.Ithadbeenuprootedand confiscated by McGill University securityguards.Theremovalofthetree wasmetwithprofoundangerandgrief. “Thedesecrationofthesapling,” wrote thewomeninastatement, “isaviolent actagainsttheKanien’kehá:kapeoples [...]Thisistakenasasignthat,despiteits LandAcknowledgementandextensive equity policies, McGill University adoptsaselectivepolicyforrespecting Indigenousvoices.”

AsIsitwritingthispieceandlooking outoverthemural,Ican’thelpbutask myself, who is reconciliation actually servingatMcGill?Itisdifficulttomake senseofwhyuniversityadministration wouldsoviolentlyrejectanattemptat reconciliation made by Indigenous peoples, yet proudly claim that their ownprojecttruly “honoursIndigenous presence. ” Moreover, it remains to be seen whether the mural will meaningfully contribute to amelioratingtherelationshipbetween theuniversityandIndigenouspeoples, whethertheybestudents,faculty,staff, or community members. Reconciliation isn’t just about making campus more beautiful. It requires institutions like McGill to disrupt and seriouslyreimaginethewaytheyrelate to the lands, waters, and peoples of TurtleIsland.

A Q&A with the diverse rock quartet.

Youmna El Halabi Culture Editor

In Montreal, we’ve had our share of cultural disappointments this year, with institutions like Blue Dog closing down, and noise complaints hailing from across town,threateningtokillthenightlife Montrealisknownfor.

Thatbeingsaid,westillhavebands bringing in the heat and staying loud andproud. Agreatexampleofthatis noneotherthanDali:anewwaverock band known for their gravelly rock textures, soulful melodies and contemplativelyrics.Daliisfrontedby singer-songwriterandrhythmguitarist Naïla, with David on lead guitar, Indianaonbass,andPabloondrums.

The band was originally a twopersonguitarduoformedbyNaïlaand David. The pair would attend open micsinMontrealwithjusttwoguitars andahungerforperformance.Atthat point, singer-songwriter Naïla had alreadywrittenquiteafewsongsand wasitchingtoplaymoreshowswitha biggerband.

“DavidbroughtonPablo,whocame to one of our rehearsals, and it really clicked,” saysNaïla.

“IndieandPabloaredating,andshe also happened to have a bass, and we neededabassist.Itjustworked.Itwas notreallyplanned.”

Dalihasbeentearingupanumberof Montrealbarsthissummer.FromQuai desBrumes,to L’hémisphèregauche,to TurboHaus, you can find their tunes rushing crowds into mosh pits and dancebreaks.

Youmna for the McGill Daily (MD): Do you find that you all have similar musical tastes for you to become a band, or is it very eclectic throughout, and then you agreed on thesoundfortheband?

Dali: The four of us have a lot in common. Most of us like bands like Radiohead, The Strokes, Arctic Monkeys.Butwearealsoverydifferent in certain aspects, especially when we ’rewritingsongs.Whilecomingup with solos, one of us could think of a certain Metallica phrase or riff or whateverthatmaybetherestofusdon't necessarilyknoworlistento,butweall rollwithit,andforwhateverreason,it workswiththetune.So,weguessboth statementsaretrue.Musically,itworks becauseofbandsandsongswehavein common, but it also works because of ourdifferentinfluences.

MD: How would you describe a typical songwriting session with all fourofyou?

A: We have this new song, and we just jam to it. We created it this way pretty much, but we don't write that muchtogether.We'retryingmoreand more to collaborate even more on every aspect. We've had a few spontaneous moments and it feels so good once it comes all together organically. Also, sometimes [we] set out with a plan, and then the plan completelychanges,andthen “Woah” MD:Whatdoyoulovemostabout playinglive?

A: Playing live is really fun. We're with different crowds all the time. Sometimesitcouldbepeopleourage. Sometimesit’sthatweird47yearold guythatbroughthisfriends,butthey're really funny. soIt's definitely cool to navigateallthedifferentpersonalities of the crowd because they're the one feedingtheenergytotheband.

MD: What’s one thing you would changeinyourgigs?

A: Maybe that the crowd is mostly theonegivingusenergy.Weshouldn’t waittoreceiveenergytogiveit.

MD:What'syourfavoritemoment whenyou'replayingliveingeneral?

A: Playingliveissuchabigrelease of energy. There's a little bit of nervousness at the beginning, but then you release and then you have all this energy with the crowd, and it'sverypowerful.

MD: What would be your song thatmadeyoufallinlovewithmusic andfallinlovewithmakingmusic?

P: Igotintomusickindofbecauseof destiny. I just kinda fell into it. I was struggling to truly find the motivator that would propel me forward. And thenIranintothealbumSwimmingby Mac Miller. I went deeper into his discography and him as an artist just kindalitalittlefireunderme.

D: WhenIwas11yearsold,Iheard “AlltheSmallThings” byBlink182for the first time and it blew my mind. I was playing Guitar Hero on the Nintendo DS, like, the worst way you couldplayGuitarHeroandthat'swhat Iplayed.Theaudiowasreallybad,butI heard the song and I loved it. I just thought it was so energetic [and] so catchy. It just stuck in my head. I remember my mom took me to see themwhenIwas12,andtheyplayedit.

N:WhenIwasyounger,Ilistenedtoa lotofpsychedelicrockandIwantedto play a tune. I also listened to a lot of

Quebec francophone music. I love to playandsing.

I:Ikindaalwayswantedtoplaymusic asanactivity,andIdidforsixyears.But when I was 15, I went to high school, andthat'swhenImetpeoplethatwere 18 and they were making it their job. And I was like, “What? You can be a musician that young and play gigs at, like,19?Okay.I'llgetserious.” AndIdid. Anex-boyfriendofminegotmeintoa conservatory.Ididclassicalupperbass, andthenIjustcontinued.Mymomisa photographer, so being an artist is normal.Evenifshewantedtokeepme awayfromit,shecouldn’t,clearly.

MD:Sowhythename“Dali”?

A: It'slikeSalvatoreDaliandthe clock painting. When you listen to asongoryouplayone,you'rekind ofsuspendedintime,andtimecan feel different. Depending on the arrangementofthesong,itcanfeel longer than three minutes. It's just the way music can almost manipulate time, almost like a meltingclockorsomething. BesuretofollowDaliontheirsocials to keep up with their upcoming performances!

Jemima D’Sa Culture Contributor

Your local neighbourhood coffee shop today serves more than just a reliable cappuccino; it now might also boast a blueberry whipped matcha iced latte. As an Indian girl, I always make jokes about my ancestors looking down at me withshameeverytimeIordermy vanilla oat milk dirty chai. In Western countries, Asian ingredients have rapidly become viral as can be seen with matcha taking over TikTok and more and more people in the West buying, making,andconsumingchai.Yet, what exactly is so different about thesebeverages?Wheredoesthis obsession come from?

The truth is, Asian products like chai and matcha have been around for centuries. Whilst todayinCanadayoucangetthese ingredients in lattes, pancakes, smoothie bowls and tiramisu, matcha originates from the Tang Dynasty in China (7th-10th CenturyCE),andwasintroduced to Japan in the late 12th Century CE. Matcha soon became an important part of the traditional Japanese tea ceremony; it was not only a drink, but developed into an art form and a meditative ritual. Japanese Zen Buddhist monks incorporated the careful preparation and consumption of matcha into meditation, as the tea helped improve focus and contemplation – enhancing the practice of mindfulness, balance and presence. With this focus on conscious, careful consumption, the matcha craze in Western countriesisinstarkcontrastwith the drink's original meanings.

Matcha’s artisanal nature means that it is not a product

With the boom of wellness culture in the 2010s and the rise of social media, these ingredients became ripe for commodification.

suited for huge consumer demand. Ceremonial-grade matcha requires shade-grown leaves that are finely stone-

ground, yet the rise in matcha popularity in North America demands an impossibly infinite supply. The result of this high demand is lower-grade matcha blended with filler substances being sold as high-grade, thus surmounting pressure being placed on the Japanese tea industry. With the heatwaves in Kyoto this summer severely reducingmatchaproduction,this once sacred tea is facing neverbefore-seen shortages. Uji, the historic matcha capital in Japan, saw its shelves wiped clear this summer, unable to keep up with the craze.

Thus, a drink meant to evoke mindfulness, wellness, and simplicity is eviscerated by insatiable consumer demand. Matcha, rebranded and repackaged in the West, is now simply associated with health by virtue of its easily marketable signature green colour and socalled purity. Matcha, therefore, becomesawatered-downversion of itself – it is wellness and mindfulness that has been commodified and gentrified, served with a dollop of strawberry cold foam. Similarly, chai’s history and tradition are negated by its rebranding in the West. Chai, simply meaning ‘tea’, has ancient roots in the Assam region of India, yet its commercial productiondatesbacktothe19th centurywhentheBritishcolonial

relied on the indentured labour of Indians to satiate the British demand for tea and are perhaps reminiscent of contemporary

chai. Knowing this history, it becomes ironic that masala chai, once transformed into a uniquely Indian drink under an anti-

In Western countries, Asian ingredients have rapidly become viral ... matcha [is] taking over TikTok and more and more people in the West [are] buying, making, and consuming chai.

manifestations of Asian markets catering to Western interests in “exotic products”

In the early 20th century, when the British led campaigns to boost tea-drinking in India, the distinct flavour of masala chai was created by Indians in response. Meanwhile, tea, despite being produced in India, had been branded a distinctly British product – symbolizing British culture and national pride. Yet as Indian calls for independence grew, tea needed to be rebranded into an Indian product to shake off tea’ s imperial association. As a result, tea in India, despite British protest, was made sweeter with

imperialcontext,isnowbeingreappropriated in the Western world in the form of a chai latte. That being said, I’m not calling every barista, TikTok food influencer, and beverage enthusiast a neo-imperialist, nor am I asking for a historical disclaimer next to every coffee shopmenu.Butitisworthasking – why do these drinks start trending? Matcha and chai have the appeal of being ‘exotic’ as they are sourced from Asia and delivered to your local coffee shop. They transform your regular drink order into something more niche than just a basic flat white. These beverages are cultural capital, whereby

Contributor

Western consumer culture cherry-picks from global traditions and severs them from their roots, all while profiting off their aesthetic. With the boom of wellness culture in the 2010s and the rise of social media, these ingredients became ripe for commodification. TikTok algorithmsprovidethespeedand scale for the Instagrammable aesthetics of matcha and chai to go viral, with their meanings collapsed into a “vibe.” Ultimately, the marketing of these drinks benefits from an association with the “exotic” , whilst still being palatable to the Western consumer through the incorporation of frothy soy milk and hazelnut syrup.

Withthisinmind,thisraisesthe question: which ‘exotic’ drink is going to go viral next? Creators of colour on TikTok have taken to guessing – will it be Thai iced tea next? Has bubble tea had its moment already or will it see skyrocketing demand in the seasons to come? While it’ s amazing that we can try and taste fooditemsfromaroundtheworld, it’s always important to consume with awareness, lest we perpetuate cycles of erasure and appropriation, even if the crime seemsasinnocuousasacupoftea.

The Mohawk Resistance at Kanehsatà:ke, 35 years later

Miranda Forster Culture Contributor

Montreal, 1990. What had started as a peaceful blockade in the community of Kanehsatà:ke, erected by the Kanien'kehà:ka (Mohawk) Nation to block the expansionofagolfcourseonto their land, became a bloody confrontation with the arrival of the Quebec Police, RCMP, and Canadian Armed Forces. 78 days later, negotiations brought the blockade to an end, and the golf course expansion was cancelled. But the larger fight, for the recognition of Kanien'kehà: kan sovereignty over their land, was not won.

Settler media has dubbed the event the Oka Crisis. Those involved or in support of the blockade prefer a different name: the Mohawk Resistance. 35 years later, we examine the history and legacy of the resistance, as a microcosm of the struggle which continues to define our nation.

The Kanien'kehà:ka struggle for sovereignty against colonial powers stretches as far back as 1761, when they petitioned British authorities for the return of land which had been stolen in 1717 by New France. These requests were repeatedly denied, and a part of Kanehsatà:ke was renamed the town of Oka by settlers. In the 1880s, the Kanien'kehà:ka of Kanehsatà:ke planted around 100,000 pine trees outsidethetownofOka,which would come to be known as The Pines. In 1961, a golf course was built bordering the Pinesand,subsequently,neara Kanien'kehà:ka burial site.

When an expansion of the golf course was proposed in 1989, the Kanien'kehà:ka were not consulted at all. Under the settler legal system, they still hadnotbeengrantedanyclaim to the land after having seen their claims rejected three years prior. The expansion would not only encroach on the burial site, but also clear outtheremainderofthePines.

To prevent construction vehicles from breaking ground ontheexpansion,agroupfrom Kanehsatà:ke erected a blockade in March of 1990. Despite an injunction allowing

the municipality of Oka to dismantle the blockade, the resistancegainedstrengthwith support of Kanien'kehà:ka from Kahnawà:ke and Akwesasne, as well as an activist group called the MohawkWarriorSociety.After another injunction which failed to dismantle the blockade, Quebec’s provincial police force, the Sûreté du Québec (SQ), arrived slinging tear gas and concussion grenades. In the ensuing violence, an SQ corporal was killed and the SQ retreated.

The Mohawk Resistance continued to grow, drawing support and solidarity from Indigenous communities across the country through communications networks between locals. The movement had grown bigger than the golf course, bigger than just Kanehsatà:ke – it came to represent the fight for stolen land which is shared by Indigenous peoples across socalled Canada.

Kanien'kehà:ka from Kahnawá:ke blocked the Honoré-Mercier bridge. The RCMP and Canadian Armed Forces were soon called in to help the SQ, and forcefully dismantled the blockade. Then

“It wasn’t a crisis for Oka ... Oka caused the crisis. We [the Kanien'kehà:ka of Kanehsatà:ke] were the ones occupied.”

— Ellen Gabriel

14-year-oldKanien’kehá:kagirl (and future Canadian Olympian) Waneek HornMiller was stabbed in the chest by a soldier’s bayonet. In response to the Mercier Bridge blockade, local Quebecers engaged in racist protests, including the burning of a Kanien'kehà:ka effigy. The resistance ended 78 days later, with Prime Minister

Auden Akinc | Staff Illustrator

Brian Mulroney conceding to some of the Kanien’kehá:ka demands, such as cancelling the expansion of the golf course and the purchasing of the Pines by the federal government. The government promised that no further development would proceed.

Ellen Gabriel is a Kanien'kehà:ka filmmaker, artist, and activist, who becameaspokespersonforher community during the Mohawk Resistance. She recently published a book, When the Pine Needles Fall: Indigenous Acts of Resistance, detailing the complicated history and legacy of the Resistance. In an interview with The Philanthropist Journal, Gabriel gives a retrospective account of the crisis.

“It wasn’t a crisis for Oka,” she says, explaining why the moniker “Oka Crisis” is misleading. “Oka caused the crisis. We [the Kanien'kehà:ka of Kanehsatà:ke] were the ones occupied.” Indeed, the media has framed the “crisis” as an unfortunate breakdown of Indigenous and settler relations. State-sanctioned violence against Indigenous people is portrayed as the regrettable, but inevitable consequence of resistance which is deemed too radical. As Gabriel says, the media largely portrayed Kanien'kehà:ka protesters as

terrorists, “focus[ing] on the men in camo gear and ski masks holding guns.” Pauline Wakeham’s 2012 analysis of the Mohawk Resistance draws a parallel between the resistance and Operation Desert Storm (an offensive campaign by Western powers during the Persian Gulf War), which occurred within a year of each other. To illustrate the continued anti-terrorism panic sparked by the Mohawk Resistance and violence in the Middle East, Wakeham cites a collection of letters from 2006 titled “Home-grown Terror in Caledonia, Ontario,” which compares the Haudenosaunee Grand River land dispute to the violence of the Iraq War. Bizarrely, the equating of Indigenous land-rights activism to the wars in the MiddleEastwasnotlimitedto posthumous media exaggeration: a staggering four thousand soldiers were sent to Kahnawà:ke and Kanehsatà:ke, a more aggressive reaction than that which was deployed to the concurrent Persian Gulf War.

This conflation of Indigenous land-rights activism with terrorism does immense damage to the movement, and is a lasting legacy of settler institutions’ mismanagement of the Resistance.

35 years after the Mohawk Resistance, regrettably little has changed. As Ellen Gabriel

puts it, “the government just learned different ways to be sneakier about extinguishing our rights to our land.” Although the 1990 golf course expansion at Kanehsatà:ke was cancelled, ownership of thelandwasnevertransferred to the Kanien’kehá:ka it is considered an “interim land base” for the Kanien'kehà:ka to use, meaning that they have some jurisdiction over the land but no title to it. And today, 308 years after Kanehsatà:ke was first stolen, the government continues ignoring the petitions to return it. The battle against the development of the Pines was won, but the larger struggle for Indigenous sovereignty over their land continues. In the face of Quebec’s Bill 97, which catered to Quebec’s logging industry and blatantly ignored Indigenous interests, Indigenous-led blockades and protests all over the province demanded a retraction of the bill. The Coalition Avenir Quebec government showed no sign of heeding them. It seemed Canada had failed to learn the lesson which the Mohawk Resistance should have taught us decades ago: if we keep refusing to listen, Indigenous land defenders will make themselves heard.

Emma De Lemos Culture Contributor

Montreal’s perpetual state of construction does not deceive:itremainsacityof constantchange.

The McCord Museum’s current exhibition, “Pounding the Pavement,” perfectly captures the city’seclecticspiritinacollectionof Montreal street photography, running until October 28th demonstrating how street culture, particularly vibrant in neighbourhoods like the Plateau, binds together the city’ s many diasporas, later widened by the influx of international students. In truth,Montrealisnowaplacemany call “home.”

Ironically, the streets are also marked by the presence of unhoused First Nations people, whomakeuproughly12percentof Montreal’s visible houseless population. Indeed, long before its colonization, the island was home to the Mohawk and Anishinaabemowin peoples known by their names Tiohtià:ke and Mooniyang. However, the current influx of international populations has reshaped the city

both geographically and economically, further pushing Indigenouspeoplestoitsmargins.

Originally, the Plateau thrived as a multicultural hub for workingclass European immigrants between the 1850s and the 1970s. Slowly, it became the original bourgeois-bohèmehub,welcoming Montreal’sartisticimmigrantscene and the very underground local Quebecanculture.

However,thePlateau’sreputation hasshifted.

It is now one of the most coveted places to live in Montreal, often branded as the city’s bougie heart. And, according to Radio-Canada, the Plateau now stands as Montreal's most expensive neighbourhood.

For many long-time Montrealers, the Plateau has lost the prestige it once carried, and hasbecomefarremovedfromthe European bourgeois-bohème image it originally sold. As the neighbourhood became an alternative to traditional student housing and, increasingly, as an English-speaking enclave, its identity was reshaped when many streets were given anglicized names in the early

2000s such as Gilford Street, once Chemin des Carrières– at the cost of erasing Quebecois history. A new wave of gentrification has accelerated this transformation, driven by private residential and commercial investments that inflate housing prices, raise living costs, and displace residents, while commodifying the essential character of the Plateau neighbourhood.

This represents a shift from earlier attempts to profit from the Plateau’s cultural cachet most notably before October 2018, when the Plateau-Mont-Royal borough restricted short-term rentals like Airbnbs toward a new model of gentrification, where living in the neighbourhood has become an expensive and transitory experience. Gentrification in the Plateau doesn’t rely on big chains displacingsmallbusinesses.Instead, itthrivesonaestheticconsumption: the rise of pricey, vintage shops along St-Denis, the sudden appearance of eight-dollar matcha pop-up concept cafés, and the opening of costly niche bookstores onDuluth.

Underthisveilofaestheticism,the

process of gentrification raises serious concerns about housing discrimination against Indigenous peoplesinMontreal,wherewealthy international students are often prioritized for leases, reinforcing enduring colonial patterns of exclusion. Indigenous peoples represent only 0.6 per cent of Montreal’s total population, but they made up 12 per cent of the city’s unhoused population in 2018 marking them as the first and most vulnerable victims of gentrification even before the process fully unfolded. Indeed, Indigenous homelessness is rooted in Canada’s colonial history. Indigenous communities have been subject to land dispossession under the 1876 Indian Act, systemic disempowerment through the denial of self-governance, and the cultural violence of residential schools that severed their ties to land, language, and education. Today, many Indigenous families continue to face discrimination in housing services, despite legal entitlementstosupportthem.Here, Indigenous homeless people's high visibility in areas like Park Avenue or the McGill “Ghetto” ironically named, given its soaring rents

underscores how gentrification reshapes socio-spatial representations, pushing them furtherfromplaceslikethePlateau. Homelessness among Indigenous peoples can take on chronic or cyclical forms, often intertwined with mental health struggles, addictions,orunstableemployment. Yet, beyond individual causes, it is best understood as the product of historic and ongoing displacement, cultural genocide, and spiritual disconnection. What disadvantaged minority neighbourhoods truly require is sustained, targeted reinvestment that provides resources and opportunities while safeguarding affordable housing. Indigenous peoples, however, face compoundedbarriers theyare27 times more likely to be homeless than non-Indigenous people, with Inuit individuals being 80 times morelikely.

The Plateau’s gentrification lays bare a bitter truth: the housing gap between international students and struggling Indigenous people is wielded as an excuse to make the class and ethnic divide even wider. Homeshouldnotbereservedforthe luckyfew.

Eva Moore Commentary Contributor

McGill’s Indigenous Studies languageclassesaredying.

As it stands, Intro to Kanien’kéha (INDG 302) is the only INDG language course currently offered in the Faculty of Arts, with a maximum capacity of 25 students. While Naskapi, Mi’gmaw, Cree, Mohawk, and Algonquin language courses used tobeavailablethroughtheFaculty of Education, they are not offered this academic year. The IndigenousStudiesprogramisalso struggling financially. Due to a deficitinthisyear’sbudget,caused in part by the out-of-province tuition hikes imposed last year by the Legault government, individual departments at McGill are tasked with downsizing. This follows hot on the heels of the McGill hiring freeze, instituted in December 2023. The university’ s financial situation, unsurprisingly, disproportionately affects the operation of smaller departments, which already have fewer resourcesattheirdisposal.

However, the lack of both courses and funds in the Indigenous Studies department is onlyoneofthemany symptomsof the slowing momentum of social

movementsinQuebecandCanada overall.Whiletheprogramitselfis small, with only a minor offered, its symbolic importance is immense. Indigenous studies recognizes the importance of Indigenous knowledge systems, history, and, most importantly, languages – which are spoken by fewerandfewerpeople.Thestudy of Indigenous languages in educational establishments functions as a form of activism by making Indigenous cultures visible and giving a voice to their speakers, yet the underfunding and dismantling of such programs reveals how our pressing social movements are increasingly gettingsidelined.

Throughout the 2010s, Indigenous issues were pushed into mainstream public consciousness. This was largely due to grassroots mobilizations such as Idle No More, a 2012 peaceful protest movement to protect Indigenous rights and the environment, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) reports, and widespread calls for the decolonization of Canadian institutions, as well as, later, the 2021 discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves at the Kamloops Residential School. The TRC’ s Calls to Action explicitly include greater educational initiatives to

revitalize Indigenous languages that were systematically repressed through colonial policies banning their usage. Universities responded to these calls to action by creating Indigenous language courses and programs. Concordia University, for example, implemented a B.A. in First PeoplesStudies,andtheUniversity of British Columbia (UBC) is renowned for its programs in the field, one of which is specifically targeted at endangered languages. McGill’s Indigenous studies program is a consequence of this movement, declaring itself as first and foremost, “tasked with the initiationoftheimplementationof the 52 Calls to Action,” The program is meant to signal the university’s willingness to take linguisticrevitalizationseriously Yet, a mere decade later, the slow-but-sure dissolution of the program points to a regression of Indigenous activism. This decay mirrors a larger Canadian trend. The federal government pays lip service to reconciliation while simultaneously cutting resources, building oil pipelines through Indigenous land, and deprioritising social initiatives when it doesn’t suit the political agenda. For example, despite federal commitments to support Indigenous languages through the

2019 Indigenous Languages Act, funding has been inconsistent in the face of global recessions and the COVID-19 pandemic, which took the front seat in terms of federalpriorities.

Here in Quebec, ongoing efforts to support the French language through policies such as Bill 96 exclude Indigenous languages in their creation of an anglophonefrancophone binary. They leave little room for Indigenous linguisticrevival.

The gains made by social movements are often already

limited.Theybecomefragilewhen they are no longer in the public consciousness. Without the preservation of languages, Indigenous activists lose their voices, and without these voices, strong social justice movements cannot happen. McGill, the Quebecgovernment,andCanadian federal policies need to commit to prioritizing the preservation of these languages. Otherwise, we risk the dissipation of the momentum we have built up, leaving behind the rhetoric of changewithoutanysubstance.

Eva Marriott-Fabre

Aries (Mar 21Apr 19)

That’s some damn good coffee and cherry pie.

Taurus (Apr 20May 20)

Gemini (May 21Jun 20)

Have a sweet tooth? Here’s a brownie! Grandma’s Cookies are your one and only true love.

Cancer (Jun 21Jul 22)

Tiramisu is your fuel going into midterm season.

Leo (Jul 23Aug 22)

Feeling down? Have some Cheesecake! Smile and Say Cheese!

Libra (Sept 23Oct 22)

Sesame balls with savoury red bean paste, for life!

Scorpio (Oct 23Nov 21)

You bake yourself a whole tray of apple crumble on friday nights.

Virgo (Aug 23Sept 22)

A good custard will make your skin glow golden.

Sagittarius (Nov 22Dec 21)

You eat ice cream in the winter, and yes, we support you.

Capricorn (Dec 22Jan 19)

A Lil’ cupcake a day keeps the seasonal blues away.

Aquarius (Jan 20Feb 18)

Dried fruit dipped in dark chocolate, no question.

Pisces (Feb 19Mar 20)

You gobble up everything sweet, for better or for worse. but mostly better.