Ma-Yi Theater Company & The Public Theater

By Lisa Sanaye Dring

Free Ticket Program for NYC High School Students

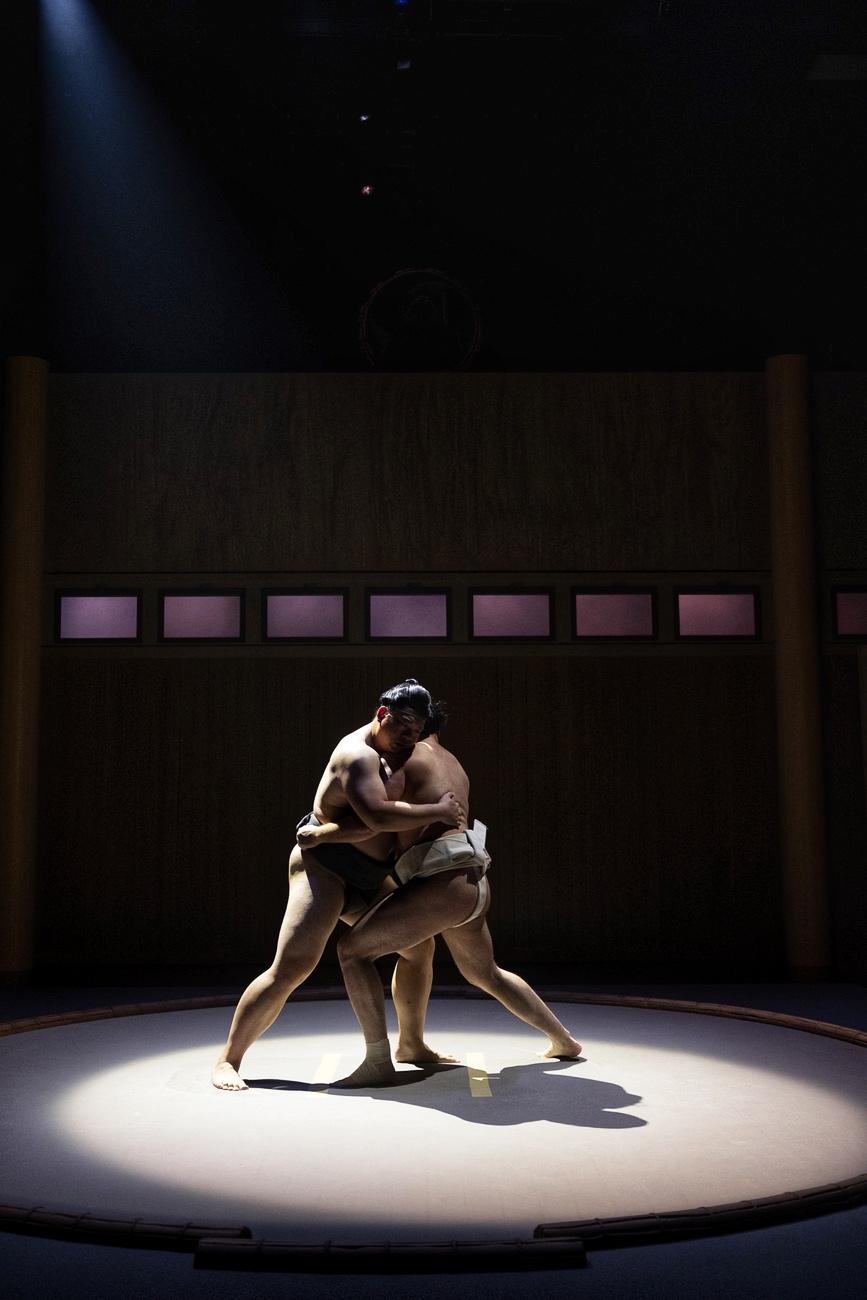

Sumo is a centuries-old Japanese sport that combines physical prowess, ritual significance, and cultural heritage. At its core, sumo is a form of wrestling where two competitors, known as rikishi, strive to push each other out of a circular ring called the dohyo, or force their opponent to touch the ground with any part of their body other than the soles of their feet.

However, sumo is much more than just a sport—it is a deeply symbolic practice rooted in Shinto traditions and Japanese history. The origins of sumo date back over a thousand years, and it was originally performed as a religious ritual to honor the gods and pray for a bountiful harvest. Many elements of these rituals remain integral to modern sumo matches, such as the purification of the ring with salt, the elaborate ceremonial stomping, and the traditional attire of the rikishi.

The rikishi themselves follow strict customs and live a disciplined life in sumo stables, where they train, eat, and sleep under a hierarchy that emphasizes respect and tradition. Matches are often quick, lasting only seconds, but require immense strength, balance, technique, and strategy. Despite its ancient origins, sumo continues to evolve, attracting both local and international audiences, and remains a powerful symbol of Japan’s identity, blending athletic competition with a profound reverence for its cultural roots.

The history of sumo wrestling can be traced back over 1,500 years, deeply intertwined with Japan's mythology and spiritual practices. According to Japanese folklore, the origins of sumo are rooted in a legendary contest between two deities, Takeminakata and Takemikazuchi. In this myth, Takemikazuchi, the god of thunder, challenged Takeminakata, a deity associated with agriculture and water, to determine the rightful ruler of the Japanese archipelago. Their epic wrestling match symbolized a divine struggle, and Takemikazuchi emerged victorious, solidifying his claim to the land. This story not only highlights sumo’s ties to Shinto beliefs but also establishes the sport as a representation of balance between power and ritual.

Following these mythical beginnings, sumo evolved as a Shinto ritual to honor the kami (gods) and secure their blessings for abundant harvests. These early matches were performed at Shinto shrines and were more ceremonial than competitive, featuring elaborate dances, purification rites, and symbolic gestures to appease the gods. The movements in sumo, such as the stomping of feet and the sprinkling of salt, are believed to have originated from these ancient rituals, meant to purify the ground and ward off evil spirits.

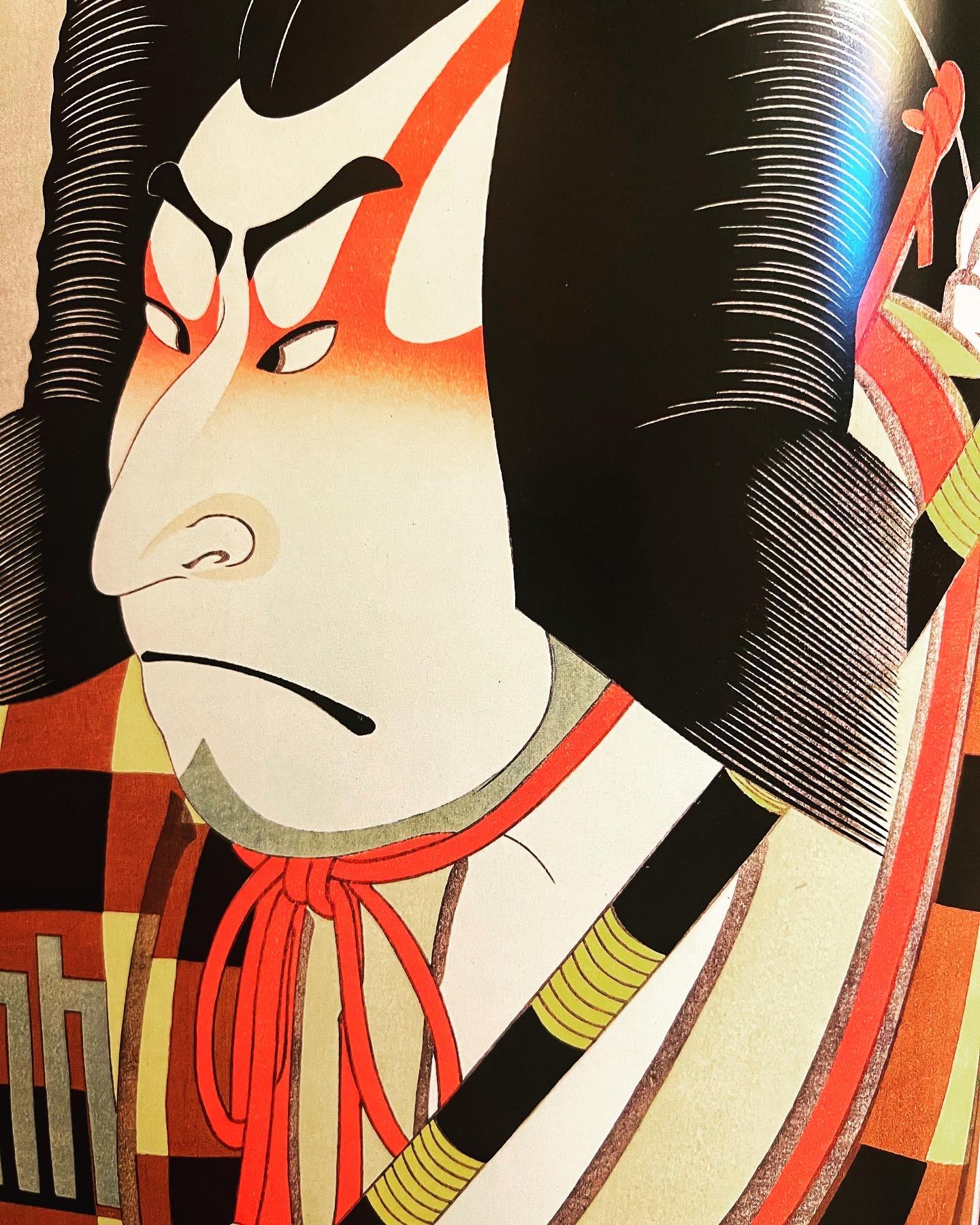

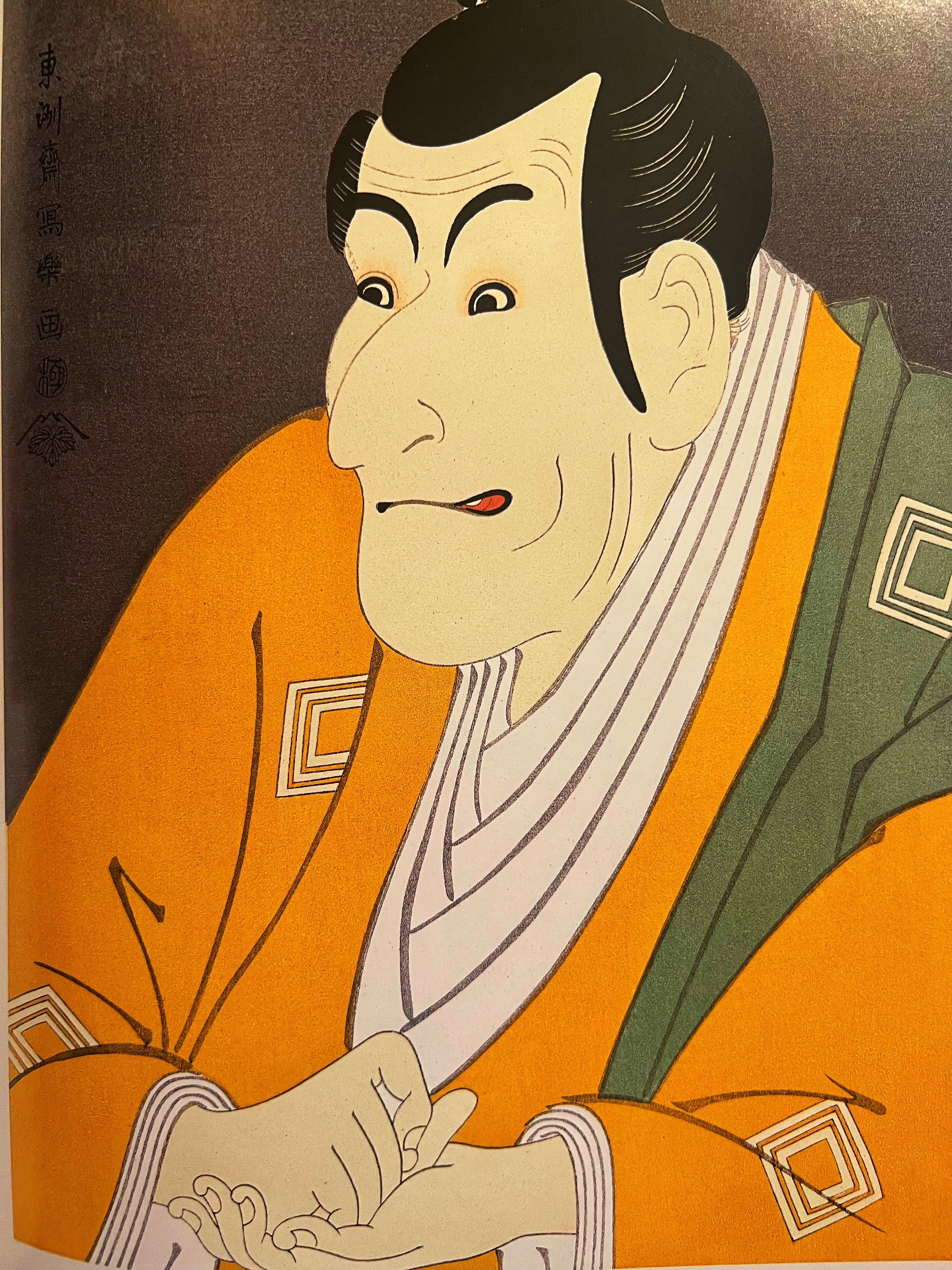

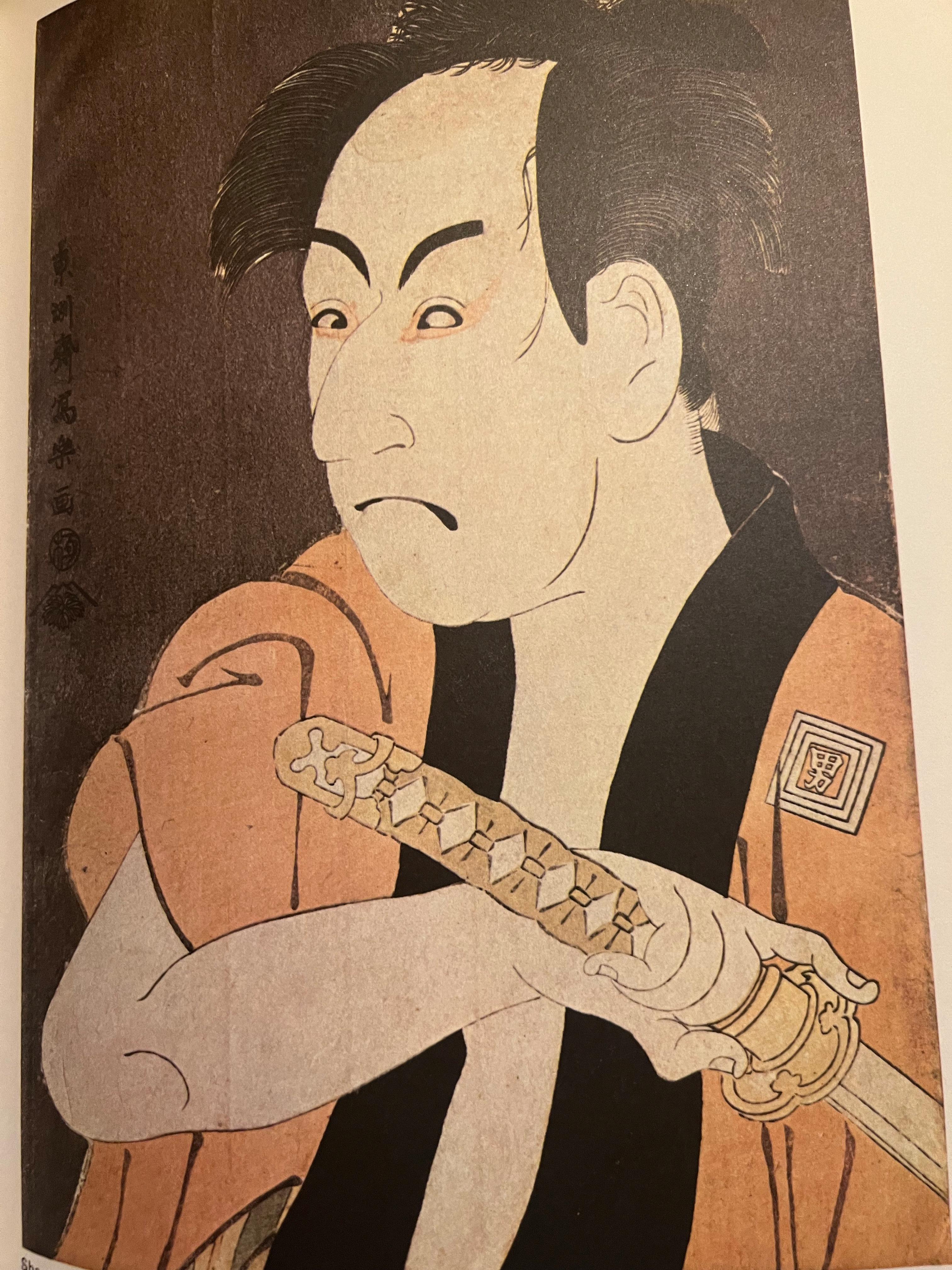

During the Edo period (1603–1868), sumo transitioned into a structured spectator sport while retaining its sacred roots. Professional sumo leagues were established, matches were held to entertain the masses, and rules were standardized. Despite this shift toward entertainment, the spiritual and ceremonial elements of sumo remained central to its identity.

Today, sumo wrestling continues to honor its mythical and spiritual origins, with tournaments incorporating rituals such as the dohyo-iri (ring-entering ceremony) and the construction of the sacred dohyo (ring), which is treated as a divine space. Modern sumo not only showcases the physical strength and skill of its wrestlers but also serves as a living connection to Japan’s ancient traditions and Shinto heritage, embodying the enduring legacy of Takeminakata and Takemikazuchi’s divine contest.

Significance in Japanese Culture: Pre- and Post-World War II

Sumo wrestling is more than just a sport in Japan; it is a profound cultural institution that reflects the country’s core values of discipline, respect, and tradition. These values are deeply embedded in the lives of sumo wrestlers, known as rikishi, who live under a strict code of conduct that governs their daily routines, diets, and social interactions. The hierarchical system within the sumo world demands respect for rank and seniority, fostering a sense of discipline and humility that extends beyond the ring.

Before World War II, sumo was a symbol of national pride and traditional identity. The sport maintained strong connections to Shinto beliefs, with rituals like salt purification and the dohyoiri (ring-entering ceremony) serving as spiritual acts of purification and harmony. Matches often coincided with Shinto festivals, emphasizing sumo’s role in honoring the kami (gods) and preserving the cultural fabric of Japan.

During this era, sumo was also seen as a unifying force, bringing together people from all social classes to celebrate Japan’s heritage. The tournaments provided a platform for showcasing the physical and mental strength that Japan admired in its citizens, particularly during a time of rising nationalism and militarization in the early 20th century.

After World War II, Japan underwent significant societal changes as it rebuilt itself from the devastation of the war. During the U.S. occupation, there were fears that traditional cultural practices, including sumo, might lose their significance in the face of modernization and Western influence. However, sumo not only survived this transitional period but also emerged as a key symbol of Japan’s cultural resilience and identity.

In the post-war years, sumo was revitalized, serving as a reminder of Japan’s deep cultural roots amid rapid industrialization and globalization. The sport became a unifying force once again, with televised tournaments bringing sumo into households across the nation. Icons like Taiho Koki, a legendary post-war yokozuna (grand champion), became symbols of perseverance and excellence, inspiring a generation of Japanese people.

At the same time, sumo began to adapt to modern society. While the rigorous training and traditional values remained intact, the sport opened its doors to international competitors, reflecting a changing Japan that was becoming more globalized. The inclusion of foreign-born rikishi, such as Hawaiian wrestlers like Konishiki and later champions like Hakuho from Mongolia, showcased sumo’s ability to maintain its traditions while embracing diversity.

Today, sumo continues to embody values such as respect for hierarchy, reverence for tradition, and discipline, making it a cultural cornerstone in Japan. Rituals like salt purification and the ceremonial construction of the dohyo (ring) serve as constant reminders of its Shinto origins, while the lifestyle of the rikishi reinforces the importance of dedication and respect. Despite modern influences, sumo retains its role as a bridge between Japan’s historical past and its evolving present, ensuring its significance remains undiminished in a rapidly changing world. In sum, sumo’s enduring appeal lies in its ability to honor its ancient roots while adapting to the demands of modernity, symbolizing Japan’s unique balance of tradition and progress.

• Rituals:

◦ Ring-Entering Ceremony (Dohyō-Iri): Wrestlers perform ceremonial movements to purify the ring and honor the gods.

◦ Salt Purification: Before each match, salt is sprinkled in the ring to cleanse and protect it from evil spirits.

◦ Pre-Match Stomping (Shiko): Wrestlers stomp their feet to drive away bad spirits.

• Training Regimen: Wrestlers live in communal stables (heya) under strict discipline. Their daily routines include intense physical training, eating large meals like chankonabe (a high-protein stew), and observing traditional customs.

• Hierarchy: Senior wrestlers receive privileges and respect, while juniors perform chores and assist in daily routines, reinforcing humility and discipline.

A honbasho is an official sumo tournament and represents the pinnacle of the sport, where rikishi (wrestlers) compete at the highest level in a display of skill, strength, and discipline. These tournaments are not only the most anticipated events in the sumo calendar but are also significant cultural and ceremonial occasions in Japan, deeply rooted in the country's traditions.

There are six official honbasho tournaments held annually, each lasting 15 days. They occur every two months, ensuring a consistent rhythm to the sumo season. The tournaments take place in specific locations, with four held in Tokyo and two in regional cities:

1. March (Haru Basho) – Osaka

2. May (Natsu Basho) – Tokyo (Ryogoku Kokugikan)

3. July (Nagoya Basho) – Nagoya

4. September (Aki Basho) – Tokyo (Ryogoku Kokugikan)

5. November (Kyushu Basho) – Fukuoka

The schedule ensures that fans from various parts of Japan have an opportunity to witness sumo’s grandeur in person, while also marking seasonal transitions and maintaining the sport's steady presence throughout the year.

The honbasho holds great importance in both the sporting and cultural realms of Japan:

1. Athletic Pinnacle of Sumo

Each honbasho determines the ranking of rikishi, as performance in these tournaments affects their position on the banzuke (ranking list). The highest honor in a honbasho is to win the yusho (championship) in the top division, a feat that requires unparalleled skill, mental toughness, and consistency over 15 days. For a yokozuna (grand champion), winning a honbasho reinforces their legacy, while for lower-ranked wrestlers, it is an opportunity to rise in the hierarchy.

Honbasho is steeped in tradition, making it more than just a sporting event. Ceremonial rituals are a central part of the tournament, such as the dohyo-iri (ring-entering ceremony), where wrestlers clad in ornate silk aprons perform rituals to honor the gods and purify the ring. The gyoji (referee) and yobidashi (announcer) also wear traditional attire, adding to the pageantry and historical continuity of the event.

Honbasho tournaments are televised and widely watched across Japan, uniting the country in admiration for its national sport. These events transcend regional and generational divides, creating a shared cultural experience. The sight of a rikishi achieving victory, often accompanied by the throwing of zabuton (seat cushions) by excited spectators, is a vivid symbol of communal joy and celebration.

The honbasho ensures the ongoing preservation of sumo’s ancient rituals and practices. From the purification of the dohyo with salt to the meticulous way the tournaments are conducted, these events keep alive the Shinto-inspired customs that are integral to sumo's identity.

The regional honbasho in cities like Osaka, Nagoya, and Fukuoka provide significant economic boosts to their respective areas. Hotels, restaurants, and local businesses see increased patronage during the tournaments, and the events help promote regional pride and tourism

Synopsis of SUMO by Lisa Sanaye Dring

Set in the cloistered and hierarchical world of a sumo stable (heya) in Japan, SUMO is a compelling exploration of tradition, discipline, identity, and ambition. The play focuses on the lives of six sumo wrestlers, each grappling with their place in the rigid structures of sumo while confronting their personal struggles and desires.

At the center is Akio, a young, fiercely determined newcomer, who joins the heya with dreams of greatness. As he navigates the grueling physical demands and the emotional toll of sumo, Akio clashes with Mitsuo, the stable's top-ranked wrestler, poised to become a Yokozuna (grand champion). Mitsuo’s harsh mentorship forces Akio to confront the depths of his ambition, self-worth, and identity.

Throughout the play, the wrestlers live under the shadow of tradition, with the Kannushi (Shinto priests) narrating the spiritual and mythological roots of sumo. Rituals and matches are interspersed with moments of camaraderie, rivalry, and personal revelation. The characters’ interactions reveal the burdens of conformity and the sacrifices demanded by the sport. As Akio ascends the ranks, he learns the cost of greatness and the unspoken rules that govern the world of sumo. The play culminates in a climactic tournament that tests the wrestlers' physical and emotional limits, leaving them irrevocably changed.

1. Akio

◦ A newly recruited sumo wrestler (maezumo, unranked) and the play’s protagonist. Akio is driven by an intense desire to prove himself, though his youthful arrogance and inexperience make him a target for the stable’s hierarchy. Over the course of the play, Akio grows from a brash novice into a resilient and determined competitor, though not without great personal cost.

2. Mitsuo (Kōryū)

◦ The top-ranked wrestler in the heya (ōzeki), on the brink of becoming Yokozuna. Mitsuo is a fearsome, disciplined leader whose strict mentorship style borders on cruelty. He carries the weight of the stable’s legacy, balancing personal ambition with the expectations placed on him as the heya’s best fighter.

3. Ren (Shūgyō)

◦ A skilled, disciplined wrestler (jūryō rank) and a stabilizing force within the stable. Ren is pragmatic and quietly supportive, often serving as a mentor to the younger wrestlers. Despite his strength, he struggles with chronic injuries and the pressures of maintaining his position.

4. Fumio (Taka no Shima)

◦ A wrestler of middling rank (makushita) who is talented but inconsistent. Fumio’s insecurities and self-doubt often hinder his performance, making him a tragic figure in the play. His vulnerability underscores the harsh realities of sumo life.

5. Shinta (Kakugyō)

◦ A free-spirited wrestler (sandanme rank) with a kind heart. Shinta’s empathetic nature makes him ill-suited for the brutality of sumo. His eventual failure and departure from the heya highlight the unforgiving nature of the sport.

6. So (Gyōsen)

• The lowest-ranked wrestler (jonidan) besides Akio. Optimistic and somewhat comedic, So serves as both a servant and a moral compass for the heya. His lighthearted demeanor masks a deep understanding of the emotional weight carried by the wrestlers.

7. Kannushi 1, 2, and 3

• Shinto priests who act as narrators and spiritual guides, weaving the mythological and cultural significance of sumo into the play. They embody the connection between the wrestlers’ rituals and their spiritual origins.

Lisa Sanaye Dring's play SUMO is deeply relevant to what's happening in the U.S. today because it addresses issues and themes that resonate with the country's evolving cultural, social, and political landscape. Here's why:

• The play delves into the complexities of identity, including cultural heritage, gender roles, and personal authenticity. These themes reflect ongoing conversations in the U.S. about diversity, inclusion, and the challenges of navigating multiple identities in a multicultural society.

• For Asian Americans and other marginalized communities, SUMO provides a nuanced exploration of the struggle to honor tradition while forging a new path, mirroring the experiences of many fi rst- and second-generation immigrants.

2. Body Image and Societal Expectations

• The world of sumo wrestling offers a unique lens to examine body image, physicality, and societal expectations around beauty and strength. These conversations are highly relevant in the U.S., where there’s a growing movement to challenge harmful stereotypes and promote body positivity.

• The play explores the psychological toll of striving for greatness in an intensely competitive and hierarchical system. This reflects broader issues in the U.S. about mental health, burnout, and the pressures of achieving success, particularly among young people and those in high-stakes industries.

4. Representation and Cultural Visibility

• The play centers on a uniquely Japanese cultural practice, offering an opportunity to elevate and celebrate a nonWestern tradition in a U.S. context. This aligns with the current push for better representation of underrepresented cultures and narratives in the arts and media.

5. The Role of Tradition in a Changing World

• Sumo wrestling, as portrayed in the play, grapples with the tension between honoring tradition and adapting to modernity. This mirrors debates in the U.S. about how to preserve cultural heritage while embracing progress, especially in a rapidly changing society.

6. Power, Gender, and Patriarchy

• The hierarchical and male-dominated structure of sumo wrestling invites a critique of power dynamics and gender roles. These issues are central to many movements in the U.S., including ongoing discussions around gender equality, feminism, and dismantling systemic patriarchy.

7. Interconnectedness in a Global Society

• As the U.S. becomes more interconnected with the world, SUMO fosters cross-cultural understanding by inviting American audiences into a deeply Japanese cultural space. This reflects the importance of global awareness and empathy in today’s increasingly interdependent world.

David

1. Introduction to Sumo Wrestling

• Overview of Sumo:

◦ Definition: Sumo is a traditional Japanese sport combining physical strength, ritual significance, and cultural heritage. Matches involve forcing an opponent out of the dohyo (ring) or making them touch the ground with any part of the body except their feet.

◦ Rituals: Ring purification with salt, ceremonial stomping (shiko), and the dohyo-iri (ring-entering ceremony) connect the sport to Shinto traditions.

◦ Daily Life of Rikishi: Wrestlers live in hierarchical stables (heya), following rigorous training regimens and a disciplined lifestyle.

Questions:

1. What elements of sumo wrestling reflect its Shinto origins?

2. How does the hierarchical system in sumo shape the lives of rikishi?

3. Why is sumo considered more than just a sport in Japan?

2. History and Evolution of Sumo

• Mythical Origins:

◦ According to folklore, the gods Takemikazuchi and Takeminakata wrestled to decide the fate of Japan. This myth links sumo to Shinto beliefs and rituals.

• Evolution:

◦ Initially a religious practice to honor kami (gods), sumo transitioned into a spectator sport during the Edo period while retaining its ceremonial roots.

◦ Modern sumo incorporates international wrestlers and adapts to globalization while preserving tradition.

Questions:

1. How do sumo rituals like stomping and salt purification reflect their ancient purposes?

2. In what ways did sumo evolve during the Edo period?

3. How has modern sumo balanced tradition and globalization?

3. Key Themes in SUMO

• Exploration of Tradition vs. Modernity:

◦ The play examines the tension between preserving sumo's traditional values and the personal struggles of the rikishi in a changing world.

◦

• Humanizing Wrestlers:

◦ Wrestlers are portrayed as multidimensional characters, revealing their vulnerabilities, ambitions, and emotional complexities.

◦

• Masculinity and Identity:

◦ Challenges stereotypes of stoic, invulnerable masculinity by presenting the wrestlers as emotionally complex and struggling with personal burdens.

Questions:

1. How does SUMO highlight the tension between tradition and modern values?

2. What moments in the play reveal the wrestlers’ emotional vulnerabilities?

3. In what ways does SUMO challenge traditional views of masculinity in sumo wrestling?

4. Cultural Significance of Honbasho (Grand Sumo Tournaments)

• Structure and Rituals:

◦ Held six times annually in cities like Tokyo, Osaka, and Fukuoka.

◦ Features ceremonial rituals like the dohyo-iri and salt purification, emphasizing spiritual and cultural traditions.

• Cultural Unity:

◦ Broadcasted widely, honbasho unites Japan in celebrating its heritage and showcases sumo’s enduring significance.

Questions:

1. What role do honbasho tournaments play in preserving sumo’s rituals and traditions?

2. How do honbasho reflect the cultural and spiritual significance of sumo in modern Japan?

3. Why are regional honbasho important for both cultural unity and local economies?

5. Characters in SUMO

6. Discussion Questions for Deeper Analysis

• Akio: A determined novice, grappling with ambition and personal growth.

• Mitsuo: A senior wrestler balancing the pressures of legacy and personal ambition.

• Ren, Fumio, Shinta, So: Wrestlers representing various ranks and emotional struggles, showcasing the diverse challenges within the sumo world.

• Kannushi (Shinto Priests): Narrators who connect the wrestlers’ lives to the spiritual and mythological roots of sumo.

Questions:

1. How does Akio’s journey reflect the personal sacrifices required in sumo?

2. What role does Mitsuo play in highlighting the pressures of success and tradition?

3. How do the Kannushi’s stories connect sumo’s past to the wrestlers’ present struggles?

1. How does the rigid hierarchy of sumo reflect broader societal structures in Japan?

2. In SUMO, how do the personal struggles of the wrestlers parallel the challenges of maintaining tradition in a modern world?

3. How does Lisa Sanaye Dring use the characters’ stories to humanize the physical and emotional demands of sumo?

4. What do the rituals in sumo, as depicted in the play, reveal about the importance of spirituality and discipline in Japanese culture?

5. How does the inclusion of foreign-born rikishi in modern sumo parallel the play’s exploration of cultural adaptation and globalization?