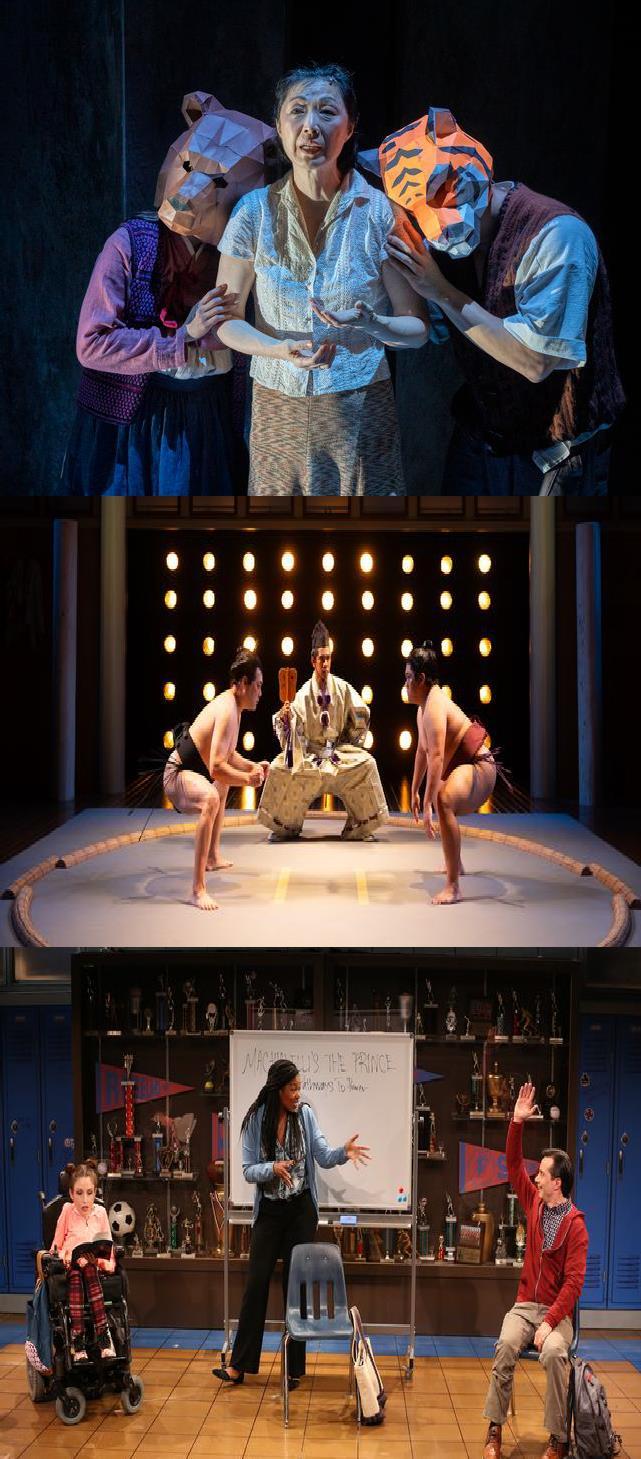

SUMO

By LISA SANAYE DRING

Directed by Ralph b. Peña

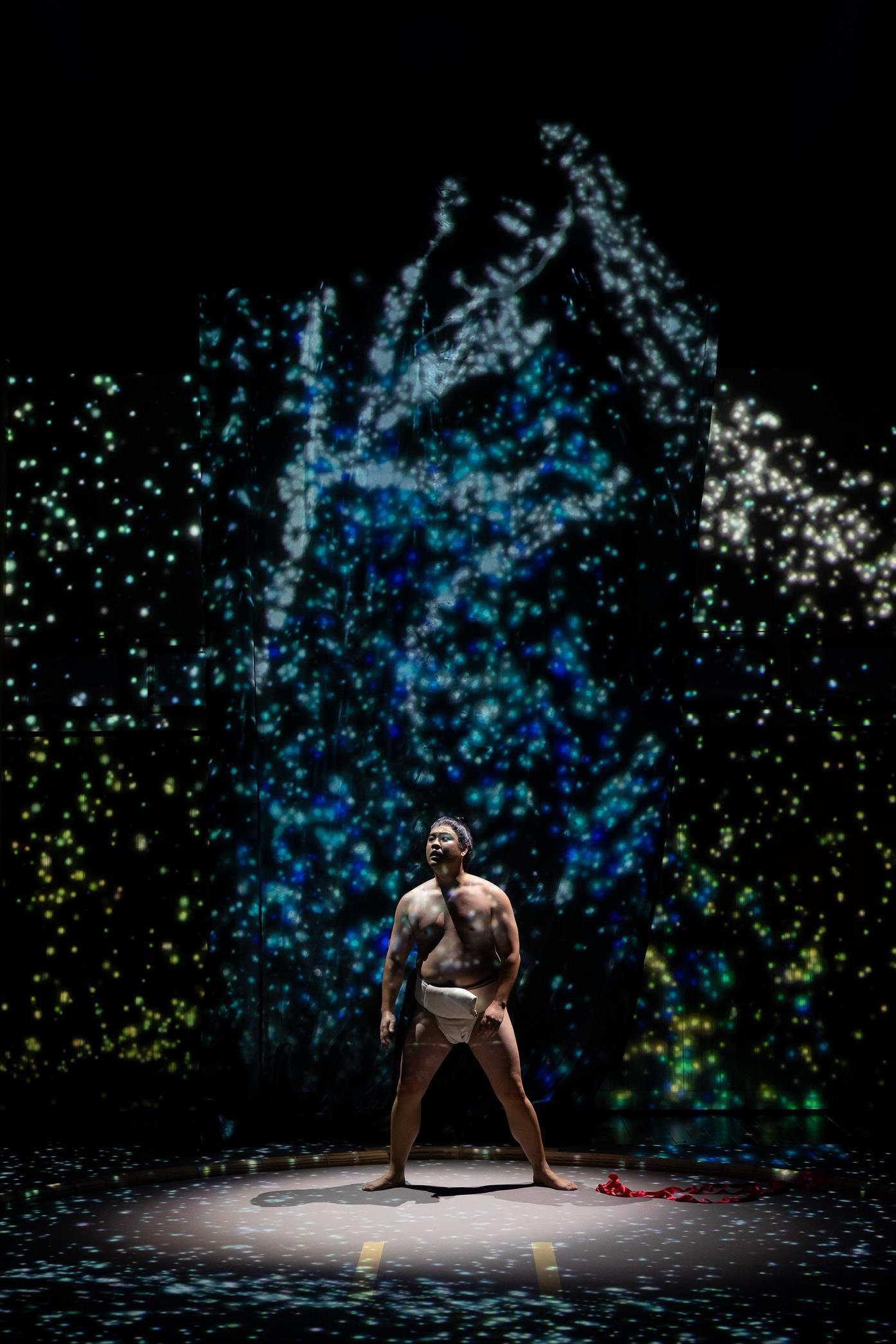

A young, ambitious rikishi named Akio risks everything to gain acceptance into the world of gods.

By LISA SANAYE DRING

A young, ambitious rikishi named Akio risks everything to gain acceptance into the world of gods.

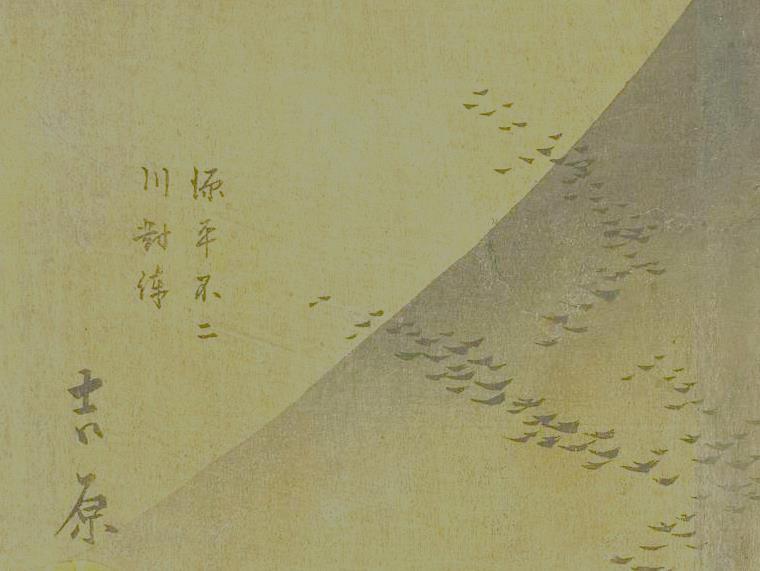

Sumo wrestling, an iconic symbol of Japanese culture, intertwines the threads of sport, religion, and tradition into a distinct and captivating tapestry. As Japan's national sport, sumo's origins can be traced back over 1,500 years, making it one of the oldest forms of organized competition in the world. Its rich history is steeped in ritual and ceremony, reflecting the Shinto belief system from which it originated.

The earliest references to sumo are found in the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters), compiled in 712 AD, which includes stories of gods engaging in sumo bouts, suggesting the sport's divine origins and its role in Japanese mythology. Sumo was not only a sport but also a ritualistic offering to the gods, a prayer for a bountiful harvest and peace across the land. It was performed at the imperial court in front of the emperor during festivals, further entwining it with national pride and spiritual significance. During the Nara and Heian periods (710-1185), sumo evolved from a loose form of combat into a more structured sport with defined rules. It was during these times that sumo started to become part of the annual harvest festivals, serving both entertainment and religious purposes. The sport's popularity grew, and professional sumo wrestlers began to emerge, although it was still primarily practiced by Shinto priests and as a form of military training.

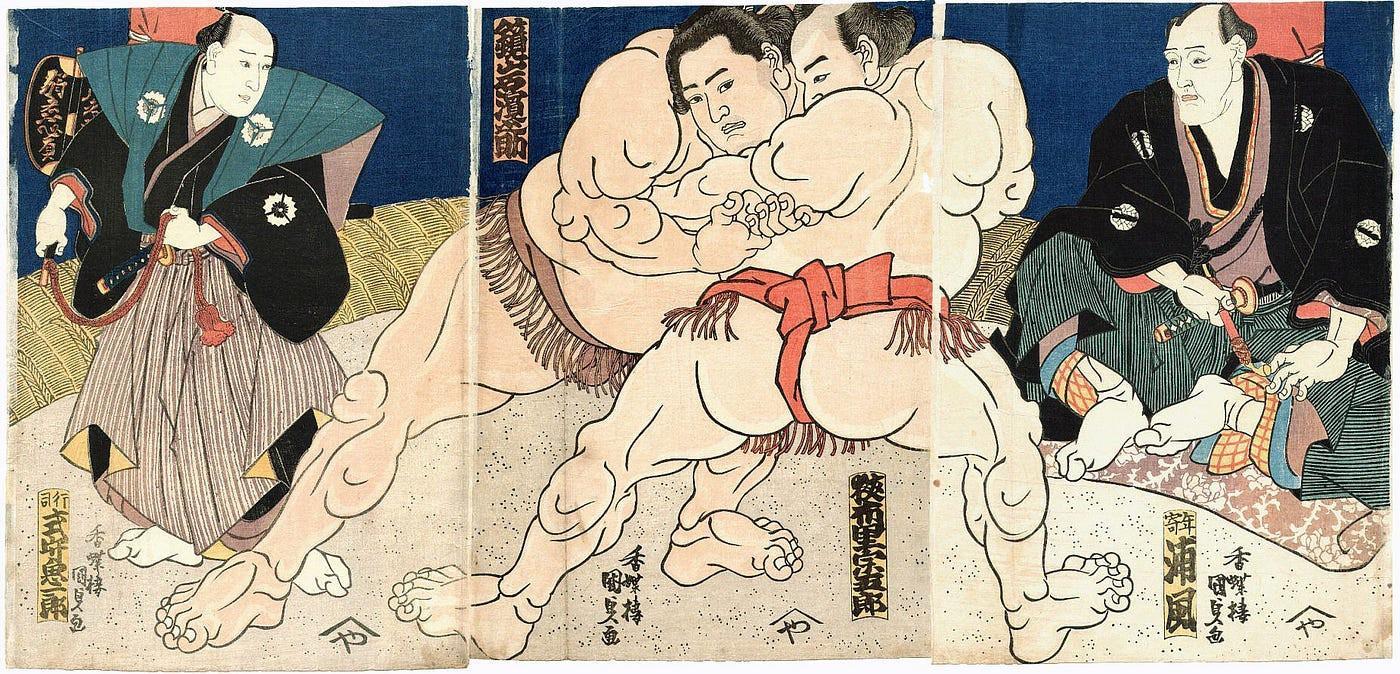

The Edo period (1603-1868) marked a significant evolution in the history of sumo. It transformed into a professional sport, with organized tournaments and a formal ranking system. This period saw the establishment of the stable system, where wrestlers trained and lived together under the guidance of a stable master. The role of the Yokozuna, the highest rank in sumo, was formalized during this time, becoming a symbol of utmost excellence and respect in the sport.

Sumo matches were held to raise funds for constructing temples, bridges, and other public works, indicating the sport's integral role in community development and social welfare. The circular ring, or dohyo, was introduced, and the sport's rules were standardized. Matches were held under the patronage of wealthy merchants and feudal lords, who sponsored tournaments and contributed to the sport's growth.

In modern times, especially post-World War II, sumo has undergone further professionalization and internationalization. While remaining deeply traditional, with rituals such as the salt- throwing ceremony for purification of the dohyo and the wearing of the elaborate silk aprons (kesho-mawashi) during official ceremonies, sumo has adapted to contemporary times, attracting global audiences. Tournaments are now broadcast worldwide, and while the sport is dominated by Japanese wrestlers, it has seen champions from other countries, reflecting its international appeal.

Despite its global reach, sumo remains a quintessential part of Japanese identity. It is more than just a sport; it is a living tradition that embodies the Japanese spirit of respect, honor, and perseverance. Sumo's endurance and ongoing popularity attest to its deep roots in Japan's cultural and spiritual landscape, making it an enduring symbol of the nation's heritage and an enduring spectacle of human strength and spirit.

I N G S

Sumo wrestling features awell-defined ranking system known as the "banzuke," which is updated before eachof the six annual tournaments, or "honbasho." The rankings determine not only the order of bouts but also aspects of wrestlers' daily lives, including their accommodations, salaries, and even their dining order in the communal sumo stables. Here’s a breakdown of the main ranks within professional sumo:

1. Yokozuna

The highest rank in sumo, Yokozuna, is not just a testament to a wrestler’s ability in the ring but also to their dignity and character outside of it. A Yokozuna is expected to be a paragon of the sumo community and once promoted, cannot be demoted; they must retire if they can no longer perform at the top level.

2. Ozeki

Just below Yokozuna, Ozeki are sumo's most senior champions. Wrestlers must consistently perform at a very high level to be considered for promotion to Ozeki. Unlike Yokozuna, an Ozeki can be demoted if they have several poor performances, but they also have the chance to reclaim their rank with strong showings in subsequent tournaments.

3. Sekiwake

This is the third-highest rank and often considered one of the most challenging as wrestlers must perform exceptionally well to advance beyond it. Achieving consistent wins at this level can lead to consideration for promotion to Ozeki.

4. Komusubi

The fourth-highest rank and the lowest of the "San'yaku" ranks, which include Yokozuna, Ozeki, Sekiwake, and Komusubi. Wrestlers at this level face very tough bouts against the highest-ranked opponents, serving as a proving ground for potential elevation to higher

5. Maegashira

This is the lowest rank in the top division, or "Makuuchi," and the most populous. Wrestlers at this level are trying to improve their records to advance into theSan'yaku ranks. The performance of Maegashira wrestlers, especially against higher-ranked opponents, can significantly impact their future rankings.

Beneath the Makuuchi division, there are several lower divisions where wrestlers work to improve their skills and ascend to the top division. These include:

• Juryo: The second division, featuring wrestlers who can potentially move up to Makuuchi with strong performances.

• Makushita: The third division and the highest rank where wrestlers do not receive a salary.

• Sandanme: The fourth division.

• Jonidan: The fifth division.

• Jonokuchi: The lowest division, primarily for new wrestlers.

Promotions and demotions among these ranks are based strictly on performance in official bouts, with wrestlers moving up or down thebanzuke based on their win/loss records in each tournament. The dynamic nature of the ranking system adds a strategic depth to sumo, as wrestlers must not only contend with the physical challenges of the sport but also navigate their careers through its structured hierarchy.

There have been over 70 wrestlers who have attained this highest rank since the title was officially recognized in the late 18th century. The title of Yokozuna is not just an indicator of a sumo wrestler's skill and performance, but also of their ability to uphold the dignity and cultural significance of sumo. Here, are some notable Yokozuna throughout the history of sumo, highlighting different eras:

Early Yokozuna:

Akashi Shiganosuke (1630s): Recognized posthumously as the first Yokozuna.

Ayagawa Goroji (mid-1700s): Another early figure recognized retroactively as a Yokozuna.

19th Century:

Tanikaze Kajinosuke (1778–1795): The first wrestler officially recognized as a Yokozuna within his lifetime.

Raiden Tameemon (1790–1811): One of the most famous sumo wrestlers of all time, known for his immense strength and size.

20th Century:

Futabayama Sadaji (1937–1945): Held a record of 69 consecutive match wins, a record that stood for several decades.

Taiho Koki (1961–1971): Holds the record for the most tournament wins (32) by any sumo wrestler.

Chiyonofuji Mitsugu (1981–1991): Known for his longevity and dominance in the sport, winning 31 top division championships.

21st Century:

Asashoryu Akinori (2003–2010): Dominated the sport in the early 2000s with a fierce style, winning 25 top division titles.

Hakuho Sho (2007–2021): Considered by many to be the greatest sumo wrestler of all time, Hakuho set numerous records, including the most tournament wins (45) and the most wins overall.

Recent Yokozuna:

Kakuryu Rikisaburo (2014–2021): Known for his technical skill and consistency.

Kisenosato Yutaka (2017–2019): The first Japan-born Yokozuna in nearly two decades, his promotion was highly celebrated.

Terunofuji Haruo (2021–present): A remarkable comeback story, having dropped to the lower Jonidan division due to injuries before climbing back to the top.

Lisa is a writer from Hilo, Hawaii and Reno, Nevada. She is currently the Tow Foundation Writer- in- Residence with Ma-Yi Theater Company. SUMO was recently produced by La Jolla Playhouse and Ma-Yi; it won an Edgerton Award and was named Best Play by Broadway World. Lisa's play Kairos is receiving a 24/25 NNPN Rolling World Premiere with East West Players, Know Theatre of Cincinnati and Theatre Nova. She has worked with Meow Wolf and was a member of The Geffen Writers' Room. They were honored as a recipient of the 2020/21 PLAY LA Stage Raw/Humanitas Prize. She has been a finalist for the Relentless Award, the O'Neill Playwrights' Conference, the Seven Devils Playwrights Conference, and a 2x finalist (one honorable mention) for the Bay Area Playwrights Festival. Kaidan Project: Walls Grow Thin, a piece cowritten with Chelsea Sutton, was nominated for 7 Ovation Awards including Best Production (winner of 5). Lisa has been awarded fellowships at MacDowell, Blue Mountain Center and Yaddo, and received an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Interactive Programming for a piece she co-wrote and co- directed with Matt Hill called Welcome to the Blumhouse Live. lisasanayedring.com

RALPH B. PEÑA - Director

“Lisa Sanaye Dring is a playwright to watch. She has real chops and brings an abundance of talent into any room she’s in. I’m privileged to work with her on SUMO.”

Ralph is an Obie Award-winning theater-maker based in New York City.

Recent directing credits include The Far Country (Yale Repertory), the world premiere of Lisa Sanaye Dring’s SUMO (La Jolla Playhouse/Ma-Yi), Lloyd Suh’s The Chinese Lady (Ma-Yi/The Public Theater, Indiana Rep, Long Wharf Theater, Barrington Stage, (Drama Desk, Lortel, NY Outer Critics, Berkshire Theater Critics, CT Critics Circle Nominations), Michael Lew’s Tiger Style! at South Coast Repertory, and Daniel K. Isaac’s ONCE UPON A (korean) TIME for Ma-Yi Theater Company where he is

currently Producing Artistic Director. For Ma-Yi he has also directed the world premieres of Hansol Jung’s Among The Dead, Michael Lew’s microcrisis, Lloyd Suh’s

The Wong Kids (Off Broadway Alliance Best Children’s Play) and Children of Vonderly.

He wrote and directed the short film Vancouver (Cannes World Film Festival, L.A.

Indie Festival, NY International Film Award for Best Short and Best Director, 2023

UNIMA Citation of Excellence), and the documentary Twenty Years of Asian American Playwriting for PBS / ALL ARTS.

Ralph has served as Ma-Yi Theater Company’s Artistic Director since 1996, and is one of its founding members.

Founded in 1989, Ma-Yi Theater Company is a professional, award-winning not-forprofit 501(c)(3) organization whose primary mission is to develop and produce new and innovative plays by Asian American writers. Since its founding, Ma-Yi has distinguished itself as one of the country’s leading incubators of new works shaping local and national conversations about what it means to be Asian American today.

Central to Ma-Yi’s mission are challenging popular perceptions for culturally specific theater, and encouraging artists to push Asian American theater beyond easily identifiable markers. To that end, Ma-Yi provides a nurturing home for exciting, generative, contemporary playwrights to produce risky, challenging, forward-thinking new plays for American Theater.

Onstage and off, Ma-Yi is guided by knowing why and for whom we create. Ma-Yi aspires to exemplify the extent to which theater makers can be active local partners to the diverse communities that inspire them, while also participating in larger, global conversations about our roles as artists/ citizens.

Ma-Yi Theater productions have garnered many awards including multiple Obie Awards, Drama Desk, Lucille Lortel, and Henry Hewes Design Awards, among others.

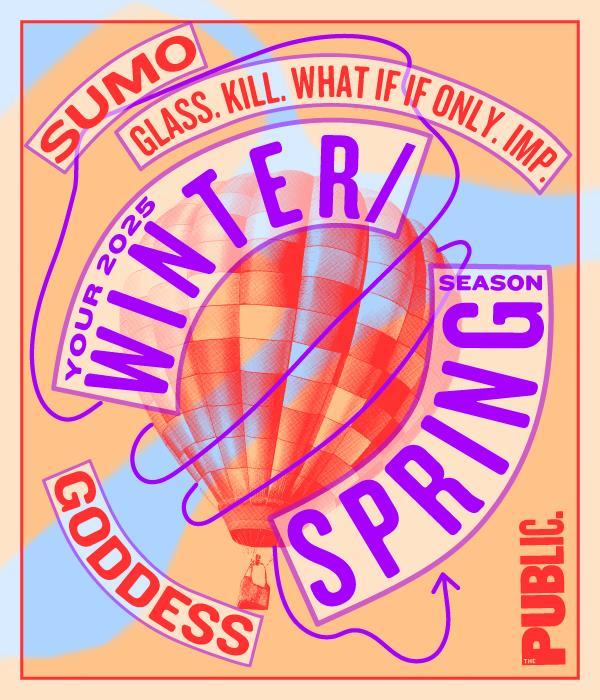

THE PUBLIC continues the work of its visionary founder Joe Papp as a civic institution engaging, both on-stage and off, with some of the most important ideas and social issues of today. Conceived over 60 years ago as one of the nation’s first nonprofit theaters, The Public has long operated on the principles that theater is an essential cultural force and that art and culture belong to everyone. Under the leadership of Artistic Director Oskar Eustis and Executive Director Patrick Willingham, The Public’s wide breadth of programming includes an annual season of new work at its landmark home at Astor Place, Free Shakespeare in the Park at The Delacorte Theater in Central Park, the Mobile Unit touring throughout New York City’s five boroughs, Public Works, Public Shakespeare Initiative, and Joe’s Pub. Since premiering HAIR in 1967, The Public continues to create the canon of American Theater and is currently represented on Broadway by the Tony Award-winning musical Hamilton by Lin-Manuel Miranda, Suffs by Shaina Taub, and Hell’s Kitchen by Alicia Keys and Kristoffer Diaz. Their programs and productions can also be seen regionally across the country and around the world. The Public has received 64 Tony Awards, 194 Obie Awards, 62 Drama Desk Awards, 61 Lortel Awards, 36 Outer Critic Circle Awards, 13 New York Drama Critics’ Circle Awards, 65 AUDELCO Awards, 6 Antonyo Awards, and 6 Pulitzer Prizes.

The world premiere of Lisa Sanaye Dring’s play SUMO was presented by La Jolla Playhouse in partnership with Ma-Yi Theater Company at La Jolla’s Forum Theater. It opened on October 13, 2023.

La Jolla Playhouse is a place where artists and audiences come together to create what’s new and next in the American theatre, from Tony Awardwinning productions, to imaginative programs for young audiences, to interactive experiences outside its theatre walls. Led by Tony winner Christopher Ashley, the Rich Family Artistic Director of La Jolla Playhouse, and Managing Director Debby Buchholz, the Playhouse is internationally renowned for the development of new plays and musicals, including mounting 120 world premieres, commissioning 70 new works, and sending 36 productions to Broadway, garnering a total of 38 Tony Awards, plus the 1993 Tony Award for Outstanding Regional Theatre.

Here’s a basic glossary covering key terms used in sumo wrestling for your next honbasho.

Banzuke

The official ranking hierarchy in professional sumo, updated before each tournament to reflect changes based on wrestlers' performances.

Chanko

A type of hearty stew that is a staple of the sumo wrestler's diet, often made with a variety of protein sources and vegetables, intended to help wrestlers gain weight.

Dohyo

The circular ring where sumo matches take place. It is made of clay and covered in a layer of sand.

Gyoji

The referee who officiates the sumo matches. They wear traditional robes and use a fan to signal their decisions.

Hakkeyoi

A term shouted by the gyoji to encourage the wrestlers to keep fighting when action in the match has slowed or come to a standstill.

Harite

Aslap to the opponent's face or body, used as a legitimate tactic within a match.

Henka

Asidestep maneuver at the initial charge, used to dodge the opponent’s attack. It is legal but often considered unsporting or controversial.

Kachi-koshi

Achieving a majority of wins in a tournament (more wins than losses), which typically leads to a promotion up the banzuke.

Kensho

Sponsorship banners that are paraded around the ring before high-profile matches. Prize money from these sponsorships is awarded to the winner of the bout.

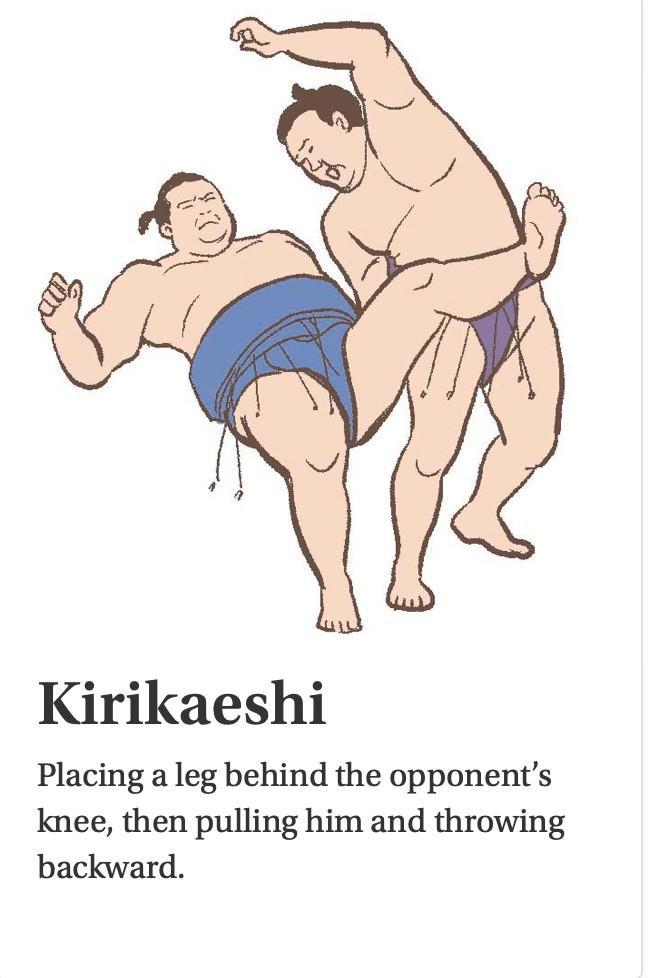

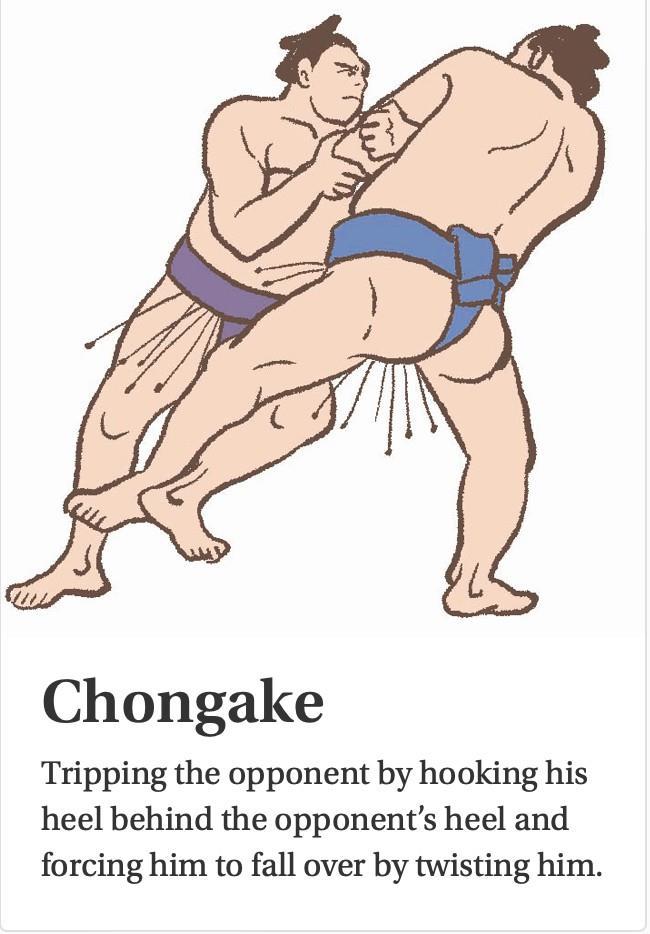

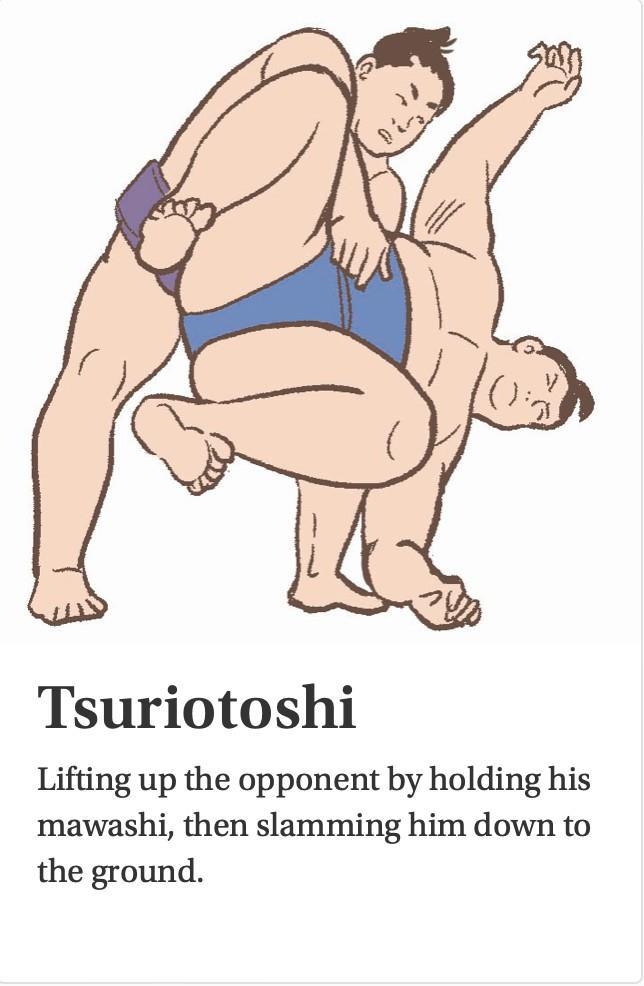

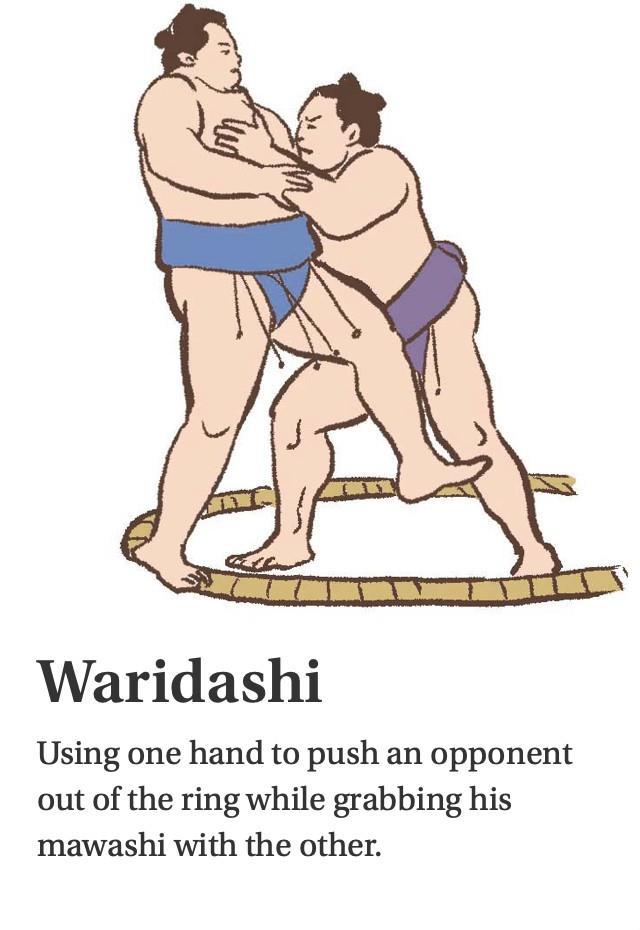

Kimarite

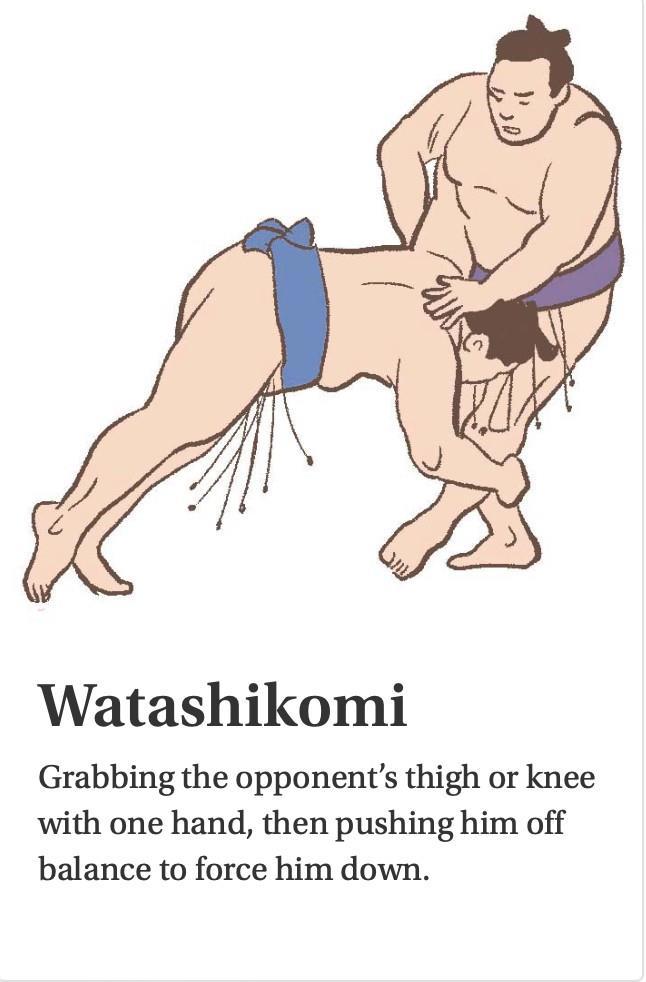

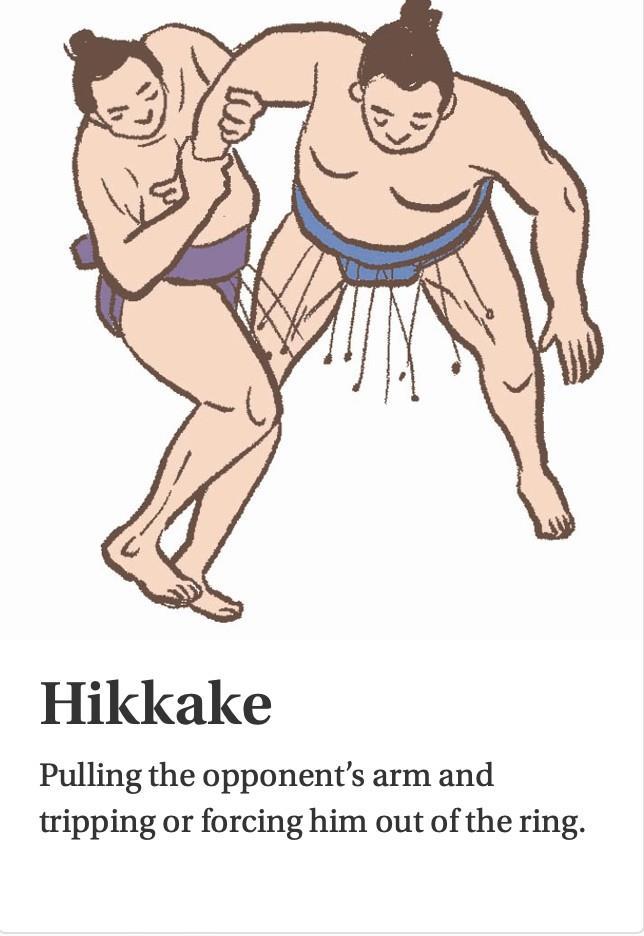

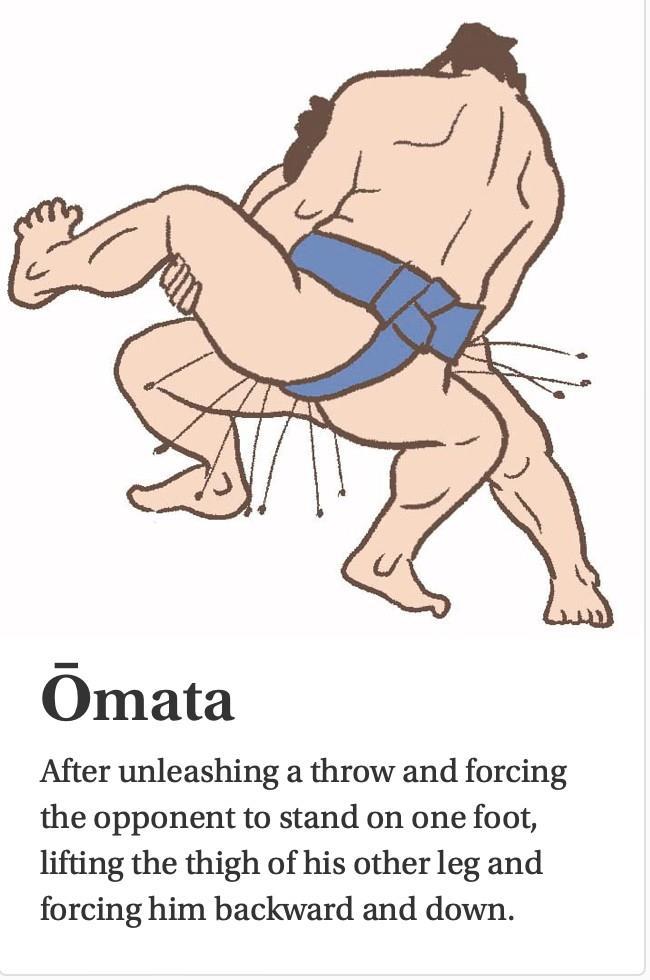

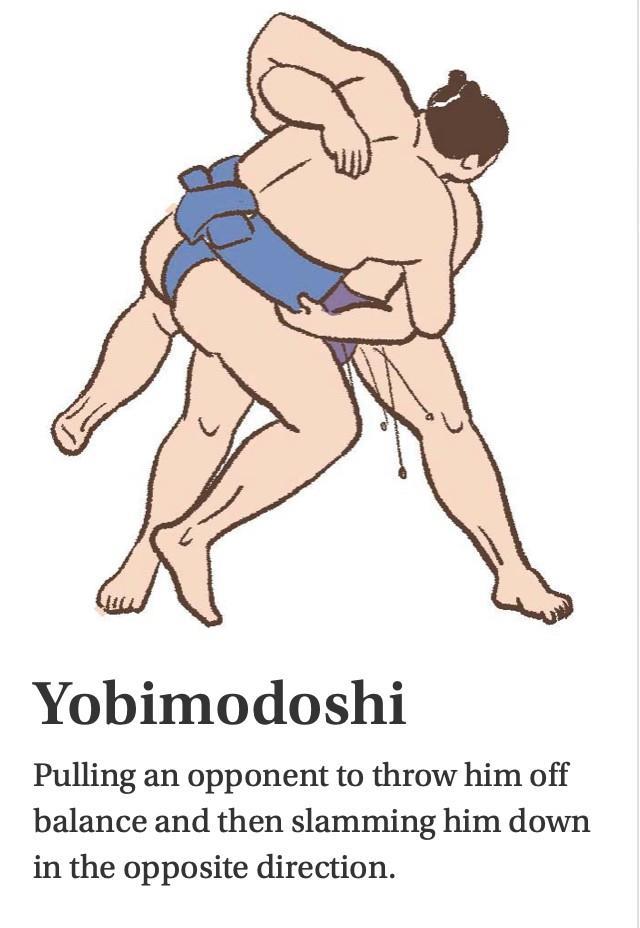

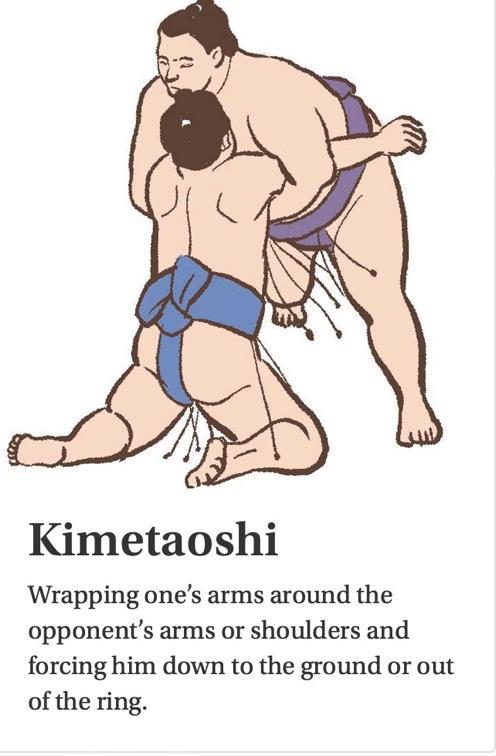

The various techniques used by wrestlers to win a bout. There are 82 official kimarite recognized by the Japan Sumo Association.

Kinboshi

A "gold star" victory achieved when a Maegashira-ranked wrestler defeats a Yokozuna.

Makuuchi

The top division in professional sumo wrestling.

Mawashi

The heavy silk belt that rikishi wear during matches. It is the only garment worn during bouts and can be used by the opponent in various techniques.

Ozeki

The second-highest rank in professional sumo.

Rikishi

Asumo wrestler.

San'yaku

The collective term for the top ranks in sumo, excluding the Yokozuna: it includes Ozeki, Sekiwake, and Komusubi.

Sekiwake

Arank just below Ozeki in the sumo hierarchy.

Shikona

A sumo wrestler's ring name, often a name that conveys certain qualities or attributes desired by the wrestler or their coach.

Tachiai

The initial charge at the start of a sumo bout.

Yokozuna

The highest rank in sumo, indicating not only superior ability but also a display of great dignity and honor both inside and outside the dohyo.

1. What does a sumo match look like?

A sumo match takes place in a ring, 4.55 meters in diameter, called a dohyo. Matches are typically brief, often lasting only a few seconds to a minute.

2. What are the rules of sumo wrestling?

The basic rules are straightforward: the wrestler loses if any part of his body except the soles of his feet touches the ground, or if he steps out of the ring. There are no weight classes, which means wrestlers can face opponents of any size.

3. How are sumo wrestlers ranked?

Wrestlers are ranked in a hierarchical system that is updated after each tournament based on their performance. The highest rank is Yokozuna (grand champion), followed by Ōzeki, Sekiwake, Komusubi, and then several divisions of Maegashira.

4. What do sumo wrestlers wear?

During matches, sumo wrestlers wear a mawashi, which is a heavy silk belt that is several meters long. It is wrapped around the body several times and securely knotted at the back.

5. How often are sumo tournaments held?

There are six Grand Sumo tournaments (Honbasho) each year, each lasting 15 days. They are held in odd-numbered months and are spread across various cities in Japan, including Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, and Fukuoka.

6. How do sumo wrestlers train?

Sumo wrestlers live in communal training stables, known as heya, where all aspects of their daily lives—from meals to training—are strictly regimented. Training typically begins early in the morning and can be very intense, focusing on building strength, flexibility, and technique.

7. What is the significance of the pre-match rituals?

Pre-match rituals in sumo, which include stomping, throwing salt, and certain Shintoinspired ceremonies, serve to purify the ring, invoke divine protection, and also psych out the opponent

8. Can women participate in sumo wrestling?

In professional sumo in Japan, women are not allowed to compete or enter the sumo ring, as it is considered a violation of purity traditions. However, amateur sumo is more inclusive globally.

9. How do sumo wrestlers maintain their weight?

Sumo wrestlers consume large quantities of a high-calorie stew called chankonabe, which includes a mix of protein sources like chicken, fish, and tofu, along with vegetables and broth. They eat this in conjunction with rice and beer to add calories. Their diet, combined with their training regimen, helps them maintain a large physique necessary for the sport.

10. Are there any health concerns associated with sumo wrestling?

Due to their heavy weight and intense physical engagements, sumo wrestlers can face various health issues, including joint problems, diabetes, and high blood pressure. The life expectancy of sumo wrestlers is generally lower than the average for Japan, partly due to obesity-related complications.

11. What happens during a sumo tournament?

A sumo tournament, or Honbasho, features a series of daily matches where each wrestler competes once per day, aiming to achieve the best record over the 15 days. The wrestler with the best record in the top division typically wins the championship, and special prizes are awarded for exceptional performances.

12. How does one become a sumo wrestler?

To become a professional sumo wrestler, one must join a sumo stable, where they live and train full-time. Most wrestlers are scouted at a young age and begin their careers in their teens. Foreigners who wish to join must also meet additional criteria, including a sufficient grasp of the Japanese language and culture.

13. What is an oyakata in sumo wrestling?

An oyakata is a title for a retired sumo wrestler who has transitioned into a coaching and managerial role within a sumo stable. Oyakata, which translates to "stablemaster," is responsible for training wrestlers, overseeing their daily lives, and managing the stable's operations. To become an oyakata, a former wrestler must have reached a certain level of achievement in their sumo career and be a member of the Japan Sumo Association. They must also purchase or inherit a share in the association, known as a toshiyori kabu. Oyakatas are responsible to maintaining tradition and discipline in a stable.

Takeminakata and Takeminazuchi are deities from Japanese mythology, particularly noted in the context of the ancient chronicles "Kojiki" and "Nihon Shoki." Takeminakata, a god associated with the Suwa region, is considered a deity of hunting and agriculture, while Takeminazuchi is a prominent warrior deity. Their relevance to sumo wrestling stems from a mythological contest described in the ancient texts, where Takeminazuchi challenged Takeminakata to a test of strength. This bout is one of the earliest recorded references to sumo, illustrating its deep-rooted connection to Shinto rituals and Japanese cultural heritage. The myth symbolizes not only physical prowess but also spiritual strength, echoing the values upheld in modern sumo wrestling, where the sport is still intertwined with Shinto rituals and ceremonies.

you can try in your next honbasho fight.