Secular Icons in an Age of Moral Uncertainty Nathan Coley, Mimosa Echard, Simon Fujiwara, Sara Naim, Indrė Šerpytytė. Curated by Coline Milliard

Secular Icons in an Age of Moral Uncertainty Nathan Coley, Mimosa Echard, Simon Fujiwara, Sara Naim, Indrė Šerpytytė. Curated by Coline Milliard

Secular Icons in an Age of Moral Uncertainty

Nathan Coley

Mimosa Echard

Simon Fujiwara

Sara Naim Indrė ŠerpytytėCurated by Coline Milliard

1 December 2017 –

3 February 2018

I like the word ‘belief.’ I think in general when people say ‘I know’ they don’t know, they believe … To live is to believe; that’s my belief, at any rate.

— Marcel Duchamp, 1973At a time when the notion of belief is particularly fraught, Secular Icons in an Age of Moral Uncertainty examines contemporary takes on some of the objects we turn to for meaning or solace. Photographs, screens, movies and commodities are here filtered through formally abstract conceptual propositions, linked by a sense of indeterminacy. Taking its title from Nathan Coley’s eponymous grids of fairground lights, the exhibition brings together forms of image-making which – while redolent of an art history spanning from Byzantine icon painting to 20th-century avant-gardes – decidedly engage with the now.

The new icons presented here don’t gesture towards the spiritual or the sublime: they send us back to today’s world in all its brilliant and brutal reality. The ‘now’ they address is multifarious; it encompasses the lure of entertainment, of luxury and gore, as well as the grisly spectacle of terrorism, and the untapped riches of technological obsolescence. More than these subjects themselves, though, what’s under scrutiny in Secular Icons is the act of looking, the dynamics driving our gaze, and the very idea of art as a system of belief, articulated around objects whose aura both depends on and transcends their materiality.

Nathan Coley is perhaps best known for his large-scale illuminated text pieces, such as There Will Be No Miracles Here (2006), which challenge the human compulsion to believe. His series Secular Icon(s) In An Age of Moral Uncertainty (2007-8) reduces the text pieces’ formal language to its bare-bone sculptural elements: metal structure and fairground lights. What remains are ambiguous light boxes at once minimal and saturated with visual memories of the funfair, as well

as of the now-ubiquitous glow of the Smartphone screen.

With wry humour, Coley appeals to our magpie attraction for all things bright and shiny, a well-worn technique used by religious imagemakers of all creed, from Orthodox icon painters to Buddha sculptors. Coley similarly tempts the viewers with illuminated baubles, but he uses no tricks, no illusions. In his Secular Icons, image and medium are equivalent: the sculpture is a strict presentation of its component parts. Yet despite this verging-on-austere conceit, Coley’s pieces’ effect far exceeds their Luna Park physicality. They shine upon the viewers like an infinite fountain of knowledge, radiating Technicolor beams. Repeated throughout the space, Coley’s Secular Icons are simultaneously authoritative and frivolous, awe-inspiring and toy-like. They articulate a push-and-pull, endlessly unresolved.

The word icon draws its etymology from the ancient Greek eikon (εἰκών) whose original meanings comprised ‘image,’ ‘figure,’ ‘reflection,’ and ‘representation’. From the start, it was understood as signifying an item standing in for a larger entity to which it was connected through likeness. Religious icons have been in circulation since the 4th century AD, but it’s only in the 8th century, with the second Council of Nicaea in 787, that their legitimacy as objects of veneration was established. From then on, icons proliferated. They followed an increasingly rigid formula whose purpose was simple: icons were meant to be easily readable for worshipers across the vast Christian world.

Coley’s Secular Icons – and by extension, all the works presented in the exhibition –are icons of a very particular kind since they undermine the very concept of ‘likeness’. These icons resist clear-cut reading; they do not fulfill a direct function, or carry a message. Instead, they flaunt a sense of indeterminacy, an openness that links them to the ‘uncertainty’ of Coley’s title. It’s important to note that

Parafin

18 Woodstock Street

London W1C 2AL

Directors

Ben Tufnell, Matt Watkins

Gallery Manager

All artworks © the artists

2017

+44 (0)20 7495 1969

info@parafin.co.uk

www.parafin.co.uk

@parafinlondon

Leanne Parks

Exhibitions and Sales

Marta Jiménez Tubau

Gallery Assistant

Fionnuala Keane-Conley

‘moral uncertainty’ here should not be taken as a critique of the contemporary world –quite the opposite. Certainties too often lead to dogmatisms, many of which are currently ravaging the globe. Moral uncertainty, the capacity to question one’s own beliefs and open up to the other, is thus a welcome state, urgently needed.

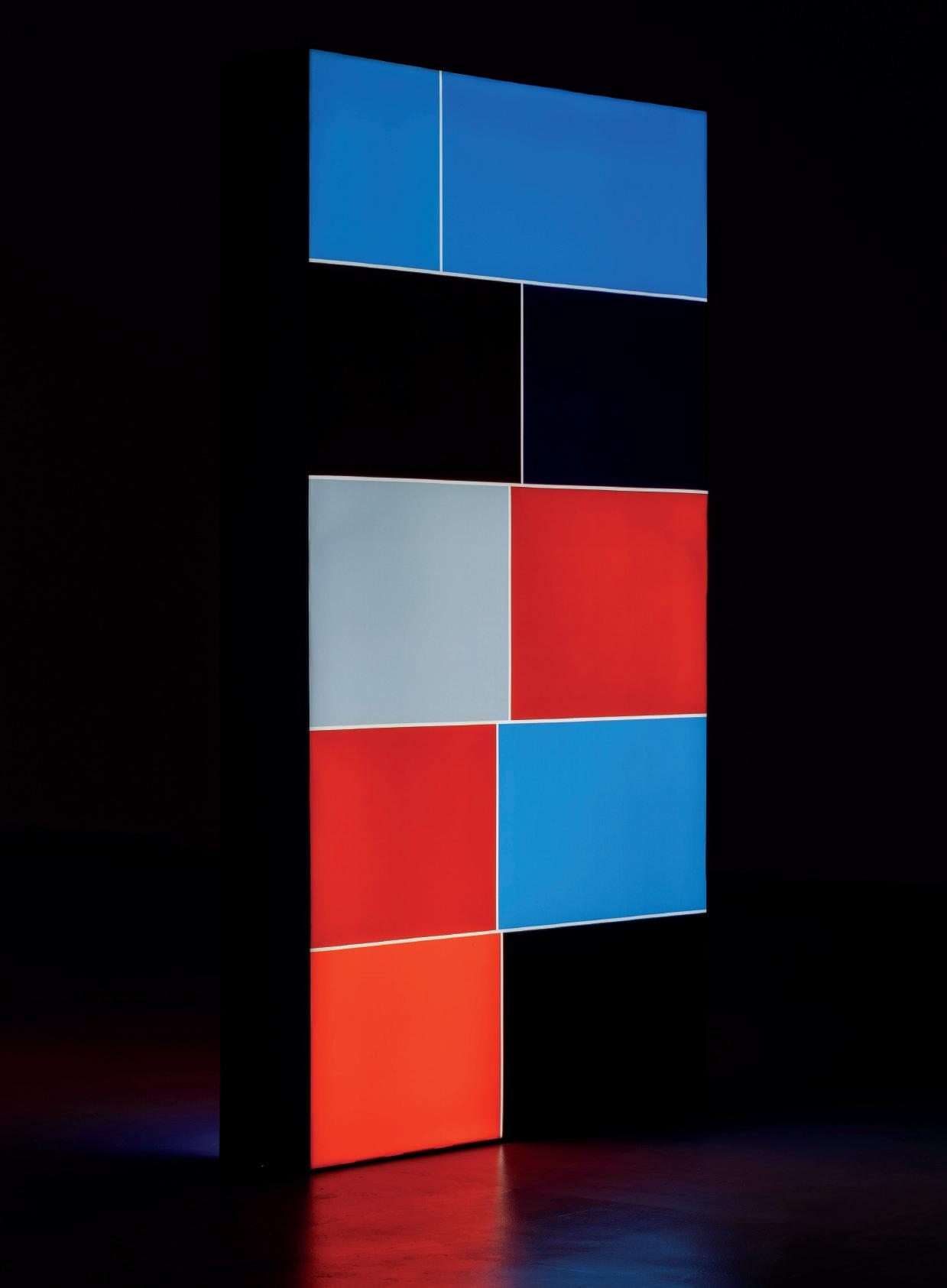

Still, if an icon remains an object allowing access to another entity – be it religious or cultural – then Indrė Šerpytytė’s pieces 2 Seconds of Colour (2015) are among the most icon-like works in the exhibition. Her monumental light boxes bring to mind geometric abstraction: the interplays between colour planes engage with the space’s vertical and horizontal sight lines. However, knowledge of Šerpytytė’s process radically transforms the perception of these

pieces. The artist captured the blocks of colour that first come up in any Google Images Search before the pictures are fully loaded. Their referent is gruesome: the burnt red, deep brown, and opaque black rectangles were triggered by the term ‘Isis Beheading’. They stand in for the desert sand, the sky, as well as the victims and executioners’ bright clothing.

The stark emotional detachment of these Mondrianesque compositions is a powerful response to the mechanisms of spectacle increasingly cultivated by extremist groups. Šerpytytė’s pieces forbid any pathos while communicating through their size, and sheer volume, something of the horrors of war and of the folly of any forms of fanaticism. Like all icons, they carve out a space for reflection, connecting us to a reality too violent to be fully comprehended.

Mimosa Echard’s Braindead series (2015) also contrasts opposites, namely the tension between its seductive, shimmery veils and the gory images the series is based on (all lifted from Peter Jackson’s 1992 comedy horror movie of the same name). To compose each work, the artist spreads silver acrylic paint on

one of the film’s ketchup-red stills. She then covers it with a thin piece of fabric and lets it harden. When the photograph is torn away, some of its pigments remain embedded in the paint. Echard embraces the disturbingly entertaining power of broken skin and gushing blood. She stages smooth body surfaces and glistening innards – outside, inside – eliciting the uncomfortable site that connects the two: the wound.

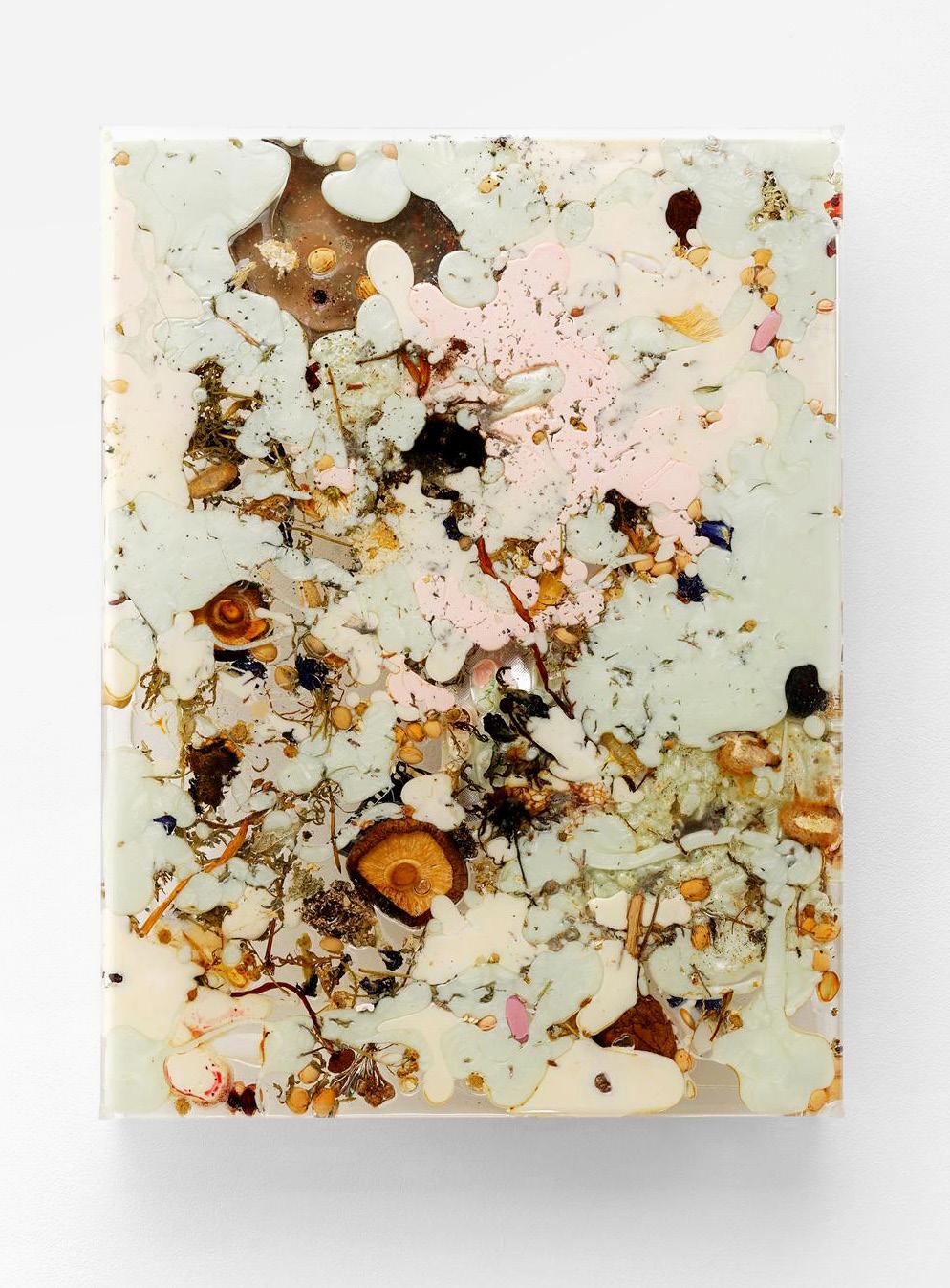

This probing of the body and accumulation of elements that refer to the corporeal in absentia are central tenets of Echard’s work. In many of her other pieces, exemplified in the exhibition by A/B29 (2017), the artist instigates a semi-controlled chaos in which melted depilatory wax features prominently. Organic elements, including plants, mushrooms, and fruit stones (often collected by Echard’s extended community in the Southern French mountains of her childhood) feature alongside fake nails and pharmaceutical products, such as lactation pills and food supplements. The patches of congealed wax activate an unruly network of formal and symbolic relationships

— Continued on page 10

Nathan Coley

Simon Fujiwara

Fabulous Beasts (True North)

2017

Shaved fur coat on wooden stretcher frame

85 × 85 × 2.5 cm, 33 1/2 × 33 1/2 × 1 in

Simon Fujiwara

Fabulous Beasts (Bluewashed Mink)

2017

Shaved fur coat on wooden stretcher frame

175 × 100 × 2.2 cm, 68 7/8 × 39 3/8 × 7/8 in

Simon Fujiwara

Fabulous Beasts (Elegy I)

2017

Shaved fur coat on wooden stretcher frame

140 × 100 × 2.2 cm, 55 1/8 × 39 3/8 × 7/8 in

Mimosa Echard

Braindead

2016

Acrylic paint and fabric

74 × 70 cm, 29 1/8 × 27 1/8 in

Mimosa Echard

Braindead

2016

Acrylic paint and fabric

230 × 150 cm, 90 1/2 × 59 1/8 in

Mimosa Echard

Braindead

2016

Acrylic paint and fabric

200 × 130 cm, 78 3/4 × 51 1/8 in

Mimosa Echard

Braindead

2015

Acrylic paint and fabric

54 × 34 cm, 21 1/4 × 13 3/8 in

Mimosa Echard

Braindead

2015

Acrylic paint and fabric

108 × 68 cm, 42 1/2 × 26 3/4 in

Sara Naim

Reaction #17

2017

C-type digital print and Plexiglass

36 × 58.5 × 26 cm, 14 1/8 × 23 1/8 × 10 1/4 in

Sara Naim

Reaction #13

2016-17

C-type digital print and Plexiglass

222 × 114 cm, 87 3/8 × 44 7/8 in

Indrė Šerpytytė

The Screen Fades to Black

2016

Video, audio 1:17 minutes duration

Indrė Šerpytytė

2 Seconds of Colour

2015-16

Double sided lightbox

150 × 265 × 30 cm, 59 1/8 × 104 3/8 × 11 3/4 in Installation views, CAC Vilnius, Lithuania

with and between the objects they glue to the Plexi-picture plane. Cosmetics, modern medicine and ancient herbalism are forced to coexist, suggesting different ways in which the body can be enhanced, healed, and perhaps destroyed.

A/B29 and the Braindead series also tackle the painting medium itself, inevitably loaded with the legacy of historical movements such as Supports/Surfaces and Abstract Expressionism. Echard’s practice develops as an ongoing research into the way images come to be. Her work stages a process of syncretisation that negates traditional taxonomies (natural and artificial, beautiful and abject, high and low culture) – process, which at times can verge on the performative. But ultimately it’s the piece, not the gesture, that the artist offers to our gaze. She pins it to the wall and exhibits it like a relic, or a hide stretched out to dry.

The skin has been cured for some time in Simon Fujiwara’s Fabulous Beasts series (2015-17). Luxurious second-hand fur coats have been shaved to expose the intricate sewing patterns constructing the garments. The leather reveals dozens, sometimes hundreds, of tiny fragments, hinting at the number of animals killed for each jacket. What remains of the slaughter, though, couldn’t be more enticing. Even shorn of their soft fleeces, the Fabulous Beasts seem to call for the hand, to demand caresses and adoration. They are

Nathan Coley

Secular Icon in an Age of Moral Uncertainty (Black)

2008

Fairground lights and aluminium

46 × 24 × 10 cm, 18 1/8 × 9 1/2 × 4 in

Nathan Coley

Secular Icon in an Age of Moral Uncertainty

2007

Fairground lights and aluminium

56 × 28 × 10 cm, 22 1/8 × 11 1/8 × 4 in

haptic fetishes, dominating those upon which they exert their fascination. Marcel Duchamp biographer Bernard Marcadé quotes the father of the readymade comparing the experience of art ‘to religious belief or sexual attraction’. As secular icons, Fujiwara’s sensual beasts occupy the nexus of these yearnings: in turns consoling and teasing but perennially elusive.

Mounted on stretchers, Fujiwara’s works also summon up a traditional painting language. The scarred leather evokes generation of artists’ struggle with painting’s core component, canvas – a struggle that has punctuated the history of the medium since the early 20th century. Fujiwara’s choice of material unsettles the distinction between image and object. Yet, although formally suggesting an almost canonical form of abstraction, the Fabulous Beasts are readymade compositions that escape the self-referential, never ceasing, instead, to refer back to the world. Their seams chart paths through uncanny landscapes, mapping intricate links between comfort, vanity, desire, and death.

Like Fujiwara’s Fabulous Beasts, Sara Naim’s Reactions (2016-7) have terrain-like qualities. As with Echard’s Braindead, they conjure up skins, inside and outside, but the artist’s main concern is the materiality of the image itself. Reactions capture the chemicals sandwiched between the positive and negative sheets of an expired Polaroid film. For each piece, Naim

dissects the film’s membranes, scans them, and blows choice details up. She is almost scientific in her approach, which is perhaps not surprising from an artist who spends as much time in labs as she does in her studio, and took anatomy classes while studying at art school. Naim’s scanner – or in the case of other series, her electron scanning microscope – fosters new types of relationships with familiar objects. As she zooms in, the scale shifts and traditional reference points dissolve. In Reactions, the rich hues of the dried up chemicals that had lied unseen for years are revealed and exposed.

What started up as an exercise in discovery – finding out what these films were like seen from up close – soon turned into an almost painterly process of composition. In an allimportant second stage, the scans are mounted behind Plexiglas and cut out into vibrant panels, defined and completed by their organic outlines. Naim relentlessly tests the possibilities of the photographic medium, and the many ways it can exist in two- and threedimensional spaces. The patterns adorning the Reactions’ surfaces are spellbinding. The more they are scrutinized, the more their formal complexity comes through; they encourage contemplation. In Naim’s hands, damaged film isn’t the end of an image, but the beginning of its reinvention. The results are beguiling polyptychs, whose commanding presence echoes the altarpiece’s.

Nathan Coley

Nathan Coley (born 1967, Glasgow) was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2007. Recent solo exhibitions include the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh (2017), Parafin, London (2017), Kunstverein Freiburg (2013), the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver (2012), ACCA, Melbourne (2011). His work was included in Generation: 25 Years of Contemporary Art in Scotland (2014), You Imagine What You Desire, 19th Biennale of Sydney (2014), Mom, Am I Barbarian, 13th Istanbul Biennial (2013), Tales of Time and Space, Folkestone Triennial, UK (2008), Days Like These, Tate Triennial of Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain (2003), and in the British Art Show 6 at BALTIC (2005). His work is represented in many collections worldwide. Nathan Coley lives and works in Glasgow.

Mimosa Echard

Mimosa Echard (born 1986, Ales, France) studied at the École Nationale Superieure des Arts Décoratifs, Paris and lives and works in Paris. Solo exhibitions include Pulsion Potion, Cell Project Space, London (2017), iDeath, Galerie Samy Abraham, Paris (2016) and Dead is the New Life, Vitrine au Plateau/FRAC Île-de-France, Paris (2015). Recent group exhibitions include Le Rêve des Formes, Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2017), Pre-capital, curated by Nicholas Bourriaud, La Panacée, Montpellier, Independence Day 2, Sommer Gallery, Tel Aviv, and The Plates of the Present, So Far, Gallerie Praz-Delavallade, Paris. In 2016 Echard exhibited in Faisons de l’inconnu un allié, Lafayette Anticipation, Paris, following her residency at Fondation d’Entreprise des Galeries Lafayette (2015). Her work is in public and private collections including the Centre National d’Art Contemporain, Paris, the Musée National d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Musée Regional d’Art Contemporain Languedoc Roussillon Midi Pyrenees, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Fondation Lafayette, and Samdani Art Foundation. Mimosa Echard is represented by Galerie Samy Abraham, Paris.

Simon Fujiwara

Simon Fujiwara (born 1982, London) studied architecture at Cambridge University and Fine Art at The Städelschule, Staatliche Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Frankfurt. He lives and works in Berlin. Recent solo exhibitions include Joanne, The Photographers’

Gallery, London (2016), The Humanizer, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (2016), Grand Tour, Kunstverein Braunschweig (2013) and Simon Fujiwara: since 1982, Tate St Ives (2012). Recent group exhibitions include Making and Unmaking, Camden Arts Centre, London (2016), Berlin Biennale 9, Akademie der Künste, Berlin (2016), British Art Show 8, Leeds Art Gallery and tour (2015) and History is Now: 7 Artists Take On Britain, Hayward Gallery, London (2015). His work is in collections including Tate, London, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York and MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt/Main.

Sara Naim

Sara Naim (born 1987, London) studied at Chelsea College of Art and Design, London College of Communication and The Slade School of Fine Art. She lives and works between London and Paris. Solo exhibitions include When Heartstrings Collapse, The Third Line, Dubai (2016) and Heartstrings, Hayward Gallery, London (2015). Recent group exhibitions include The Third Image, Biennale des Photographes du Monde Arabe Contemporain (2017). Sara Naim is represented by The Third Line, Dubai.

Indrė Šerpytytė

Indrė Šerpytytė (born 1983, Lithuania) studied at the University of Brighton and the Royal College of Art, London. Recent solo exhibitions include Absence of Experience, CAC Vilnius (2017), Pedestal, Parafin, London (2016), Still House Group, New York (2016), the Museum of Contemporary Art, Krakow (2015) and Ffotogallery, Cardiff (2013). Important recent group exhibitions include the 10th Kaunas Biennial (2017), Age of Terror: Art Since 9/11, Imperial War Museum, London (2017), The Image of War, Bonniers Konsthall (2017), Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (2015), Conflict, Time, Photography at Tate Modern and the Museum Folkwang, Essen (2014-15) and the National Gallery, Vilnius (2013). Šerpytytė will particpate in the inaugural Front International Triennial of Contemporary Art, Cleveland, and the Riga Biennial, Latvia, in 2018.