A MASSACHUSETTS HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY PUBLICATION

JULY 2024

JULY 2024

Participating in a national conference in Boston this week, with over 1,000 of my public garden colleagues, reminded me of the vast and impactful network that gardeners form. Over 120 million Americans will visit a public garden this year, and countless more are caring for gardens in their own homes. Looking globally, MHS is proud to be a patron member of Botanic Gardens Conservation International, the global organization representing over 3,500 botanic gardens, and an organization that has great impact in setting international goals and standards for plant and habitat conservation.

Massachusetts Horticultural Society is perhaps one of the smaller of these in terms of resources and garden size. Yet by being a part of this global network, we are contributing to transformational movements in both human and environmental flourishing. The collective impact of these gardens is truly making a difference.

Continued on page 4...

Tour Group explores the Italianate Garden

Similarly, as one of nearly 4,000 members of MHS, you have the ability to contribute to a greater impact than you might realize. The time you spend with family, friends, children and grandchildren in your garden is a wonderful, memory-creating experience for them. But it is also helping to support a broader good, of a generation connected to nature and the environment, one with intergenerational relationships and support, and a society which is working on positive habits that build resilience and support good mental health for life.

I want to thank you for being a gardener, and for bringing in others to share your enjoyment of this. The benefits flow further and may have a greater impact than you realize. I trust you are enjoying your garden this summer, reaping the success of the hard work of the springtime, and sharing it all with those you love. Happy gardening!

James Hearsum President & Executive Director

Orlando is a landscape architect turned freelance illustrator who loves plants, and does commissioned drawings of homes, pets and people. You can see samples of her work at www.marianneorlando.com

Shibori and Indigo Dyeing

Tuesday, July 9 9am–4pm

Drawing in the Garden: Sunflowers in Color Pencils

August 7 & 8 9:30am–3:30pm

Kokedama Workshop

Wednesday, July 17 10-11:30am

Portraying Sunflowers in Color Pencils

August 12-14 9:30am–3:30pm

Little Sprouts is a monthly class designed to foster a love and sense of wonder for the outside world in your child. Each month, we will explore a seasonal theme through a 5-senses garden walk, story-time, a hands-on craft or activity, and a take home kit.

JULY: POLLINATORS

AUGUST: SUNFLOWERS | SEPTEMBER: VEGETABLES

OCTOBER: LEAVES | NOVEMBER: WINTER HIKE

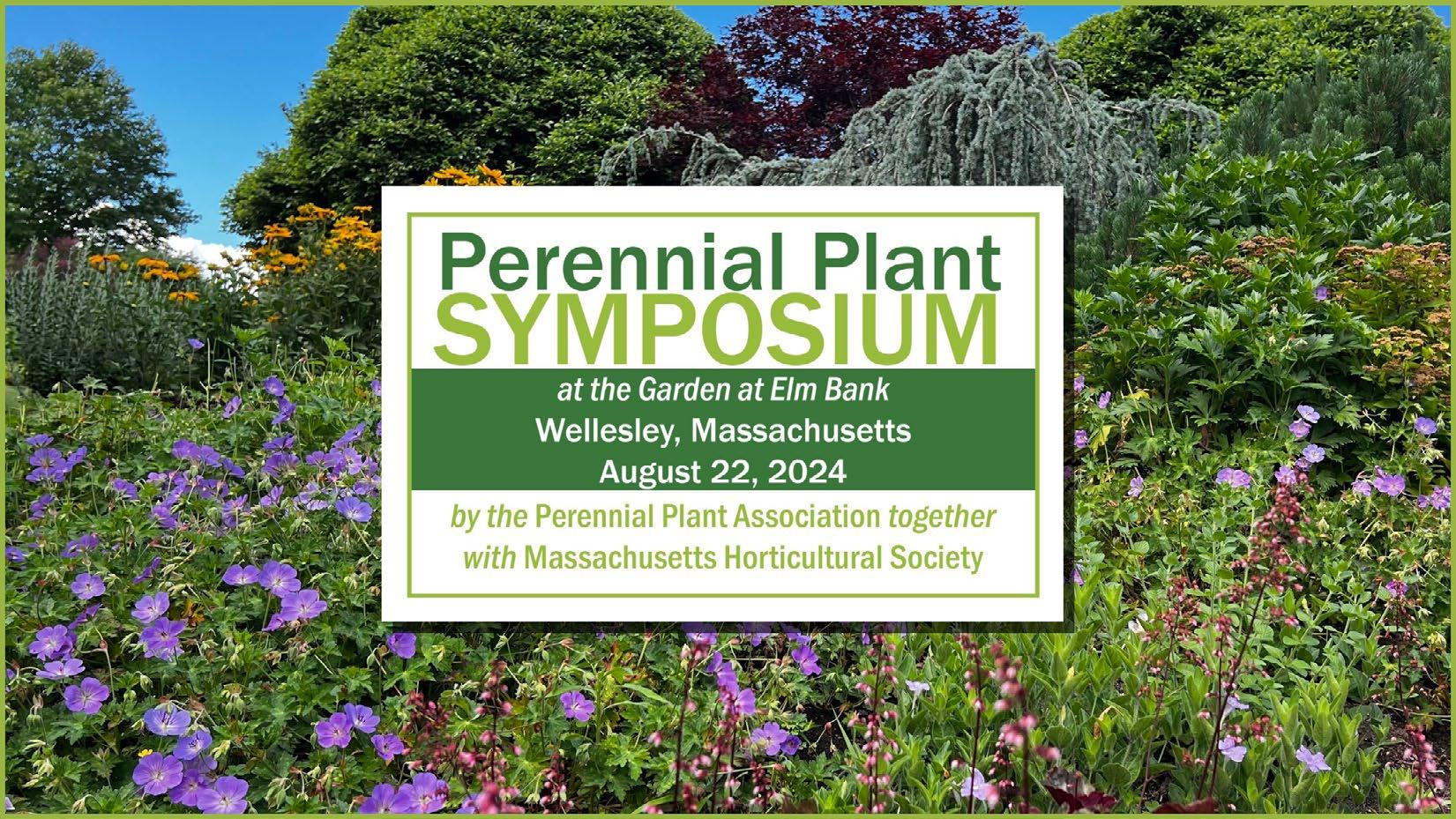

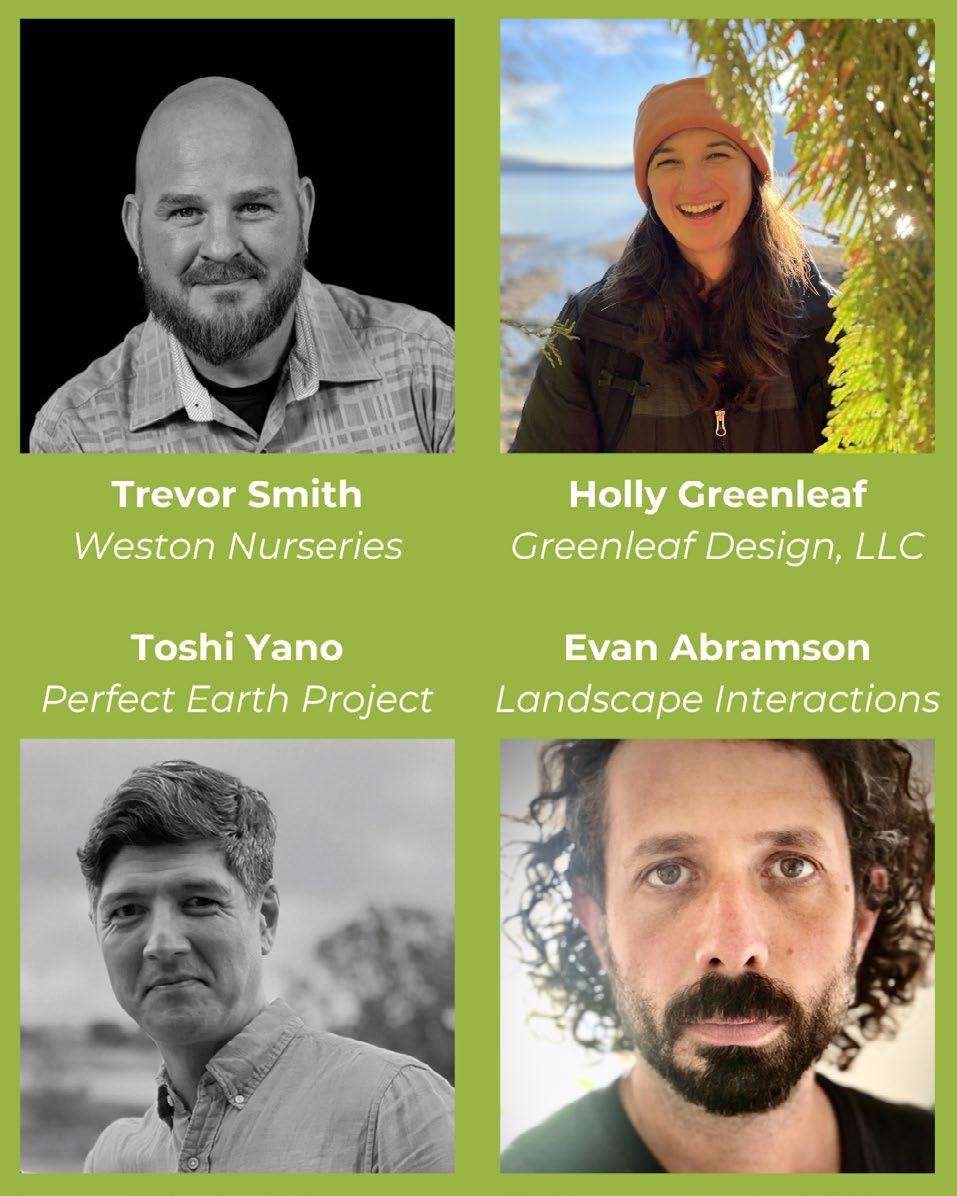

Learn everything you need to know about trends in gardening, horticulture, and landscape design at the Perennial Plant Symposium!

Thursday, August 22 from 9am-3:30pm 4 Speakers | 4 Topics Tour Opportunity Breakfast & Lunch Included

CEU credits available through APLD

General Admission: $149 MHS Members: $109

CROCKETT GARDEN BISTRO TABLES | WEDNESDAYS AT 12PM INCLUDED WITH GARDEN ADMISSION

Tuesday, August 20 at 1:30 pm

The Surprising Life of Constance Spry: From Social Reformer to Society Florist by

Sue Shepard

By Karin Stanley

By Karin Stanley

MHS was the first society I joined when I moved from Ireland to the States in 1985. Growing up in Ireland, sitting in the flower beds while my mother gardened, I had always found a deep and passionate connection with horticulture. I went on to complete the Radcliffe Landscape and History Program to expand my working knowledge in horticulture and design. My thesis was designing an Irish garden in a Celtic landscape and a Celtic garden in an Irish Landscape. This design vernacular has permeated all my work as an artist and designer. Through the years, my connection with MHS has evolved.

It is hard to describe the excitement of being ‘behind the scenes’ of a Flower Show. It’s a cross between an art installation and film production, design, horticulture, landscape lighting, water features sculpture during which one must carefully juggle the timing in cultivating all the various plants, trees, and shrubs, all of which bloom on separate schedules. Such simultaneous cultivation is an art itself. It was an incredible orchestral culmination of so many elements and hours, all to create a living canvas we can all step into. A live experience that is captivating and inspiring for only a short time, but enjoyed by so many. I was invited to be a judge in 2004 and 2005, so I have been involved the show from many angles. I am delighted we will once again see a new Flower Show this coming September at the Garden at Elm Bank.

Display gardens, whether built inside or outside, are in themselves works of art. They serve to inspire our own dream spaces, whether new vegetable potagers, or mediation corners, or wild eccentric moments within our gardens. Just being around gardens creates a sense of peace and wellbeing, inciting emotions that range from excitement to awe.

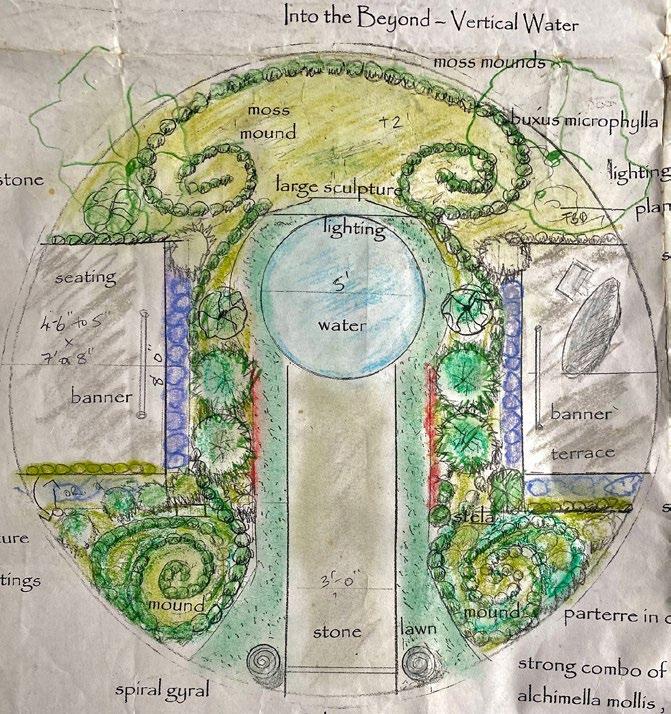

In 2006, I was asked by Massachusetts Horticultural Society to create a garden for the Irish Tourist Board at the New England Flower Show. Back then, it was held at the Bayside Expo Center. That show was one of the highlights of the Boston 2006 calendar. It brought together the best talent in Boston in all fields, from landscape architecture and design to horticulture, and showcased floral competitions and various botanical exhibitions, along with numerous lectures and a vibrant market place.

Named “Celtic Eclectic”, it combined my background as a garden designer, poet and sculptor. I created the garden in an Irish/Celtic vernacular made up of four mossy mounds, with boxwood spiraling around each mound to embrace a central path and terrace made from Irish Liscannor stone. Two additional terraces each featured a stone dolmen-style table, and a main focal point consisted of a circular pond topped by a large Celtic monolithic sculpture in steel and stone.

The plant material included four magnificent glossy green cryptomerias which anchored the four corners of the garden. The highlight was the espaliered Cercis canadensis, in peak bloom and in a rapturous shade of pink, elegantly flanking the central path described. Gary Koller remarked that they were one of the top specimens in the show, and one of best he had ever seen. After the show, the Redbuds were moved and planted in the courtyard at the Garden at Elm Bank, where they have been blooming happily for the last eighteen years.

One of my largest and most significant sculptures to date, “The Celtic Shadow Sundial,” (pictured left) was featured at the Garden in the Woods show “Rock On” and then moved to MHS. It now resides in the front of the redbrick educational building. If you look at the radial clock on the stone, the gnomon shows the time from dawn to dusk (albeit Daylight Savings Time). It is especially gratifying to visit on the summer and winter solstices, where one may observe the difference in shadows between the shortest and longest days of the year.

In 2016, John Forti, who was the Director of Horticulture, asked me to come up with a concept for “something interesting” beyond Weezie’s Garden. Julie Messervy, the designer

of Weezie’s Garden for Children, was my advisor at Radcliffe for my thesis project, and I was delighted to create something magical and enchanting next to the garden she originally designed. It eventually took on the form of a triple inverted spiral path, inspired by a Celtic amulet I designed years ago on one of my necklaces.

This was the incubus for what we called the Lunar Crescent Path, a mini land art installation. Embracing the music tree, one comes out from the secret corner of Weezie’s Garden and can walk on the ‘magical’ pathway all the way up to the other end, to the Belvedere designed by Frank Hamm. I have enjoyed seeing children and the occasional adult follow the path, connecting spaces and the journey around the garden.

In collaboration with The New England Sculptors Association (NESA), of which I am also a member, I was involved in bringing the “Sculpture in the Garden” juried exhibitions to MHS. The exhibits, “Gifts from the Garden” in 2017 and “Sculpture in Bloom” in 2018 featured sculptures throughout the property. It was a great opportunity to show how art and gardens align and enhance each other. The core principles of art and garden design both involve balance, proportion, rhythm, and focus, which come together to create a complimentary and dynamic presentation, elevating each other.

The Garden at Elm Bank has been evolving beautifully throughout the years, and I have been happy to be part of it in a number of ways. I have seen an enormous shift reflecting a tremendous and exciting change, with the development and larger vision happening under the leadership of President and Executive Director James Hearsum and Director of Garden and Programs Karen Daubmann. There are so many new garden areas within the Garden, like the new Labyrinth, which I walked a few days ago, and observing the ongoing restoration of the Olmsted Garden. I am delighted we will once again see a new Flower Show this coming September at Elm Bank. The New England Fall Flower Show this September will undoubtedly reflect this new style and energy, and will be one of the highlights of the autumnal season.

Designer-Artist-Poet Karin Stanley has a deep-rooted connection to nature, horticulture, Celtic and Megalithic precedents. She is a member of the MHS Friends Council. Her work explores spheres, monoliths, light and shadow works in stone and metal and are on display in healing gardens, institutions and numerous private collections around the world — including Cape Cod Museum of Art, and The Mount (Edith Wharton’s Home) in Lenox, MA.

By John Lee

John shares stories of Bert and Brenda and their gardening wisdom. These chronicles feature recipes, tried-and-true gardening practices, and seasonal struggles and successes. Bert and Brenda were first introduced in the March 2022 issue of Leaflet.

Over the last couple of years, maybe three, things around the homestead had become a little tatterdemalion. Brenda had chirped at Bert on and off about what she found displeasing but her comments (delivered in the nicest possible way, she thought) had heretofore fallen on deaf ears. Bert fancied himself as being really very organized - a tidy pachyderm as Rudyard Kipling might have said. He knew where everything was. To boot, he was the one who went around the kitchen closing cupboard doors, putting away the pots and pans and dishes, tidying up as she cheerfully cooked. But he, poor soul, often found himself chastised for being too tidy. As often as not, he managed to toss just the scrap of paper that Brenda’s where newest secret ingredient was noted or, equally, some recipe adventure from a magazine clipping. So, when she got her teeth into his leg about his squirrelly ways around the gardens, he tended to feel slightly ill-tempered.

All the while, he knew full well that her carpings were meant well even if they stuck in his craw. After all, it was her genius that made her sour dills taste a bit different (though equally delectable) every year. Winter evenings in the parlor in front of the Royal Oak wood stove, she would peruse her collection of clipped and saved recipes from the papers, pour over early editions of Fanny Farmer and her mother’s now yellowing Yankee Cookbook. She did this, to be perfectly honest, to avoid Bert’s annoying conversations with himself about the newest drama re the ‘hot stove league’ and whether the Red Sox would ever again achieve any measure of success in his lifetime. He had told Brenda a few years back that if the Sox ever traded Yaz, she could never again buy Hillshire Farm’s Polska kielbasa - that would be the last straw. She’d never bought any Polska kielbasa. Brenda didn’t know kielbasa from kleine wurst. She bought her sausage meat (pork scraps, really) from the local butcher when the weather turned cold - freshly ground, by the pound and she seasoned it herself just the way Bert liked it. (Winter mornings, sausage and anything for breakfast always got the day off to a good start.)

Turns out, Bert was pretty good at keeping things orderly indoors where space was restricted. His unwritten rule about too much stuff was more easily enforced (except where tools were concerned – they could never have too many tools (or even multiples like hammers and screw drives and plier-like tools). So long as his workbench was clear, Bert’s house was pretty much in order. However, this craving for orderliness seemed to end at the cellar door. Over the years, he had amassed an amazing shed-full of forks and spades, hoes and other cultivating equipment. If it had a wooden handle with a rivet sleeve, such things seemed to find their way to his shed. In fact, he had so many gardening tools that he tended to leave whatever he was using at whatever garden he was working in. And that’s what rubbed Brenda’s fur the wrong way. Seemed to her that one rolling pin, one flour sifter was quite enough.

Yes, she had only one kitchen but even so, enough was enough and Bert needed to get his gardening paraphernalia in order even though he religiously oiled and/or sharpened every implement every winter (so’s they’d last forever like “The Deacon’s Masterpiece” or the Wonderful OneHoss Shay by the redoubtable Oliver Wendell Holmes). She decided that Bert needed to come to his senses and simplify. Too many tools was simply too much and she was going to make it her mission get him to shed some of them lest they end up with a tool museum in their dying days. Bert was distraught at the thought of parting with almost any of his tools. Many of the hoes were ‘special purpose’tools. He did reluctantly acknowledge that a long-handled spade was really just a long-handled spade and he could part with a few of them (also the short-handled ones). But there was a recognizable beauty and elegance in every tool: the oak, maple or ash stems, the way the ash was split and riveted to make a place for a handle on some of them. It was the craftsmanship that made each tool special and the ‘Ames bend’ that made hand tools fungible currency during the Gold Rush days not to mention the varying shapes of the shovels. This factoid was only important to Bert. Brenda, however. thought a spade was just a spade. He, in a dark moment wondered what she would say if he told her that her dinner was just a dinner. He was pretty sure that comment would not set well and he’d best not test those waters.

Even if Brenda did not know a spade from a shovel she knew enough not to harp on his foibles too hard. He did manage to produce an amazing variety of small fruits and vegetables from their various gardens and he was a terrific help-mate whether or not her tomato puree was on the verge and in need of canning. She appreciated his help – in fact she could not do what she needed to have done all by herself anymore. Peeling the tomatoes, making the sauce, sterilizing and filling the jars was all getting to be a bit much. If nothing else, he was the best moral support and made her work less of a chore. As she was capable harvest help in the gardens, he cheerfully tasted and tested, washed and dried when push came to shove as the evenings wore on and Brenda exhausted herself putting up their off-season provisionings. At those moments, she knew, as hard at it may be, it was best to stay out of her husband’s hair about his tools as without them, she’d not be putting up the food she still loved preparing and he so appreciated enjoying day in and day out. Her meals were only as good as the garden could give, cultural practice and just the right tools.

John Lee is the retired manager of MHS Gold Medal winner Allandale Farm, Cognoscenti contributor and president of MA Society for Promoting Agriculture. He sits on the UMASS Board of Public Overseers and is a long-time op-ed contributor to Edible Boston and other publications.

Daniel Furman is co-owner of Cricket Hill Garden in Thomaston, CT. This second generation specialty nursery is known for its extensive selection of tree peonies, but also grows an interesting array of unusual fruit trees and other distinctive landscape trees and shrubs.

When I began my full-time career at Cricket Hill Garden in 2009, it was truly a “mom-and-pop” business. Twenty years earlier, after several false starts growing lettuce and garlic for local health food stores, my parents Kasha and David Furman finally hit upon a land-based business that found some traction: growing Chinese tree peonies. At the time, my father had just retired from a career in “Don Draper/ Mad Men”-style advertising and was starting a family in his 50s; after a Mr. Blanding Builds His Dreamhouse-esque misadventure in home construction, there was not much capital available for a nascent nursery. However, with their combination of marketing expertise and passion for growing, they quickly established a nursery specializing in Chinese tree peonies. Most stock was imported annually from China. The nursery was laid out at “garden” scale, with wheelbarrows and shovels as the main tools. We didn't own a tractor, though I do remember

a friendly neighbor once lent his walk-behind rototiller. The narrow focus of the business and small scale certainly circumscribed growth, but my parents had created a fulfilling way to live in a beautiful place to raise a family. Theirs was what we today call a lifestyle operation.

When I graduated from college in 2009, I had planned to try journalism, but the news business was hemorrhaging jobs amid the recession and decreasing print ad revenue. My mother asked me to come help at the nursery for a year or two, because my father’s recent Lyme disease symptoms were worsening. Alone, she was dealing with the twin burdens of both managing the business as well as my father’s healthcare.

From the beginning, my goal was to figure out how to propagate tree peonies at scale. We had always been reliant on imports from China. This worked well for about fifteen years, but beginning in the

mid 2000s, the USDA began to find prohibited fungal pathogens on our tree peony shipments. This was devastating to my parent’s business model. We cast about for replacement vendors, and did find sources for imported Japanese tree peonies, but these were hopelessly mixed up. You couldn’t even be sure to get the color you ordered, let alone the correct cultivar. Tree peonies are difficult to propagate; cuttings are not feasible for most varieties, so grafting is the traditional and still-best method for cloning tree peonies. It would take me many years to develop our technique, and I am still refining it. More time and energy also went into

clearing land so we could have more growing space for rootstock production and growing of stock plants. We still do not produce enough grafted tree peonies annually to meet the retail demand, let alone entertain any of the many requests we receive for wholesale availability.

In addition to the peonies, I also wanted to grow what interested me. I was smitten with edible and fruit bearing plants. I had always loved the raspberries which grew in semi-wild patches around the nursery, but now, with Lee Riech’s Uncommon Fruit For Every Garden as my holy book, I frantically planted mulberry,

pawpaw, persimmon, quince, and just about every other genus of temperate fruit-bearing tree or shrub. All my life, I have loved collecting things, and in my 20s this combined with my love of physical labor. (I cleared a forested 1 ⁄ 2 acre site for a “test orchard” with an old Stihl Farm Boss chainsaw and a 35 HP tractor.)

Adding more Crimean varieties of quince to our collection was not just fun, it was a business expense! I have loved the stories and culture

around these plants, and I take great delight in sharing these with our customers. One of my favorite unusual fruits, and one that has proven to be a financial success, is cornelian cherry (Cornus mas). We grow several excellent cultivars which originate from breeding work done in Ukraine. It has been a real pleasure to connect with customers originally from eastern Europe who share their memories of growing these in “the old country.” As with learning to graft tree peonies, it took me several years to learn how to grow these plants, many of which are container-grown due to ease of transplanting. As I increased our container-grown stock, so too did I have to learn about constant pressure pumps, filtration, fertigation, overhead vs. micro-irrigation, and professional potting media.

Six or seven years ago, I also was bitten badly by the bug of variegated trees and shrubs. I went from growing no sweetgums to no less than five variously dwarf, columnar, and variegated cultivars in two years. I can’t really pretend that these acquisitions were driven by well formed business considerations. I didn't carefully scrutinize the market for variegated redbuds and realize that I could carve out a corner for myself; rather, I simply

tried propagating many of the new plants I had added to our display garden. Some sold quite successfully while others did not. My approach has very much been “throwing spaghetti against the wall”; luckily some stuck. After a few years of sales data behind us, now we can begin to refine our offerings to suit demand. I remember going to the liquidation sale of a formerly prominent Fairfield country nursery many years ago: there were two partners who, due to economic headwinds and competing visions, had a rather acrimonious split, with each partner haphazardly selling what they could. I vividly remember one partner showing me the nursery’s impressive propagation house, full of heated misting beds. He said: “My partner is always saying, ‘look at all these plants I can make for free!’ and I said potting, fertilizing, and watering are not free! They just cost us money if we can’t sell them!”

Looking back over my fourteen years at Cricket Hill Garden, I am proud of the many advancements I have made, particularly in the realm of plant propagation and production. Hiring a full-time bookkeeper is probably the best money I have ever spent. This has relieved a lot of stress and brought professional expertise to an aspect of the business that

no one was particularly good at. About 10 years ago, while taking an agricultural small business administration class through UConn, we had a worksheet exercise to help construct a chart of accounts and balance sheets for the business. When it came to the business assets, there were shockingly few: a used tractor, some even more worn-out implements, and a used pickup truck. I think it was then that I realized that the most valuable asset which our nursery possessed was our good reputation and customer list. My parents had managed to source quality tree peonies for many years and had always offered customers replacements if they failed to grow in the first season. I have continued this policy, very rare in the nursery business, since there are so many factors

out of our control which affect how a plant grows once it leaves the nursery. This guarantee leads us to replace or offer store credit for a miniscule percentage of plants from the previous year’s orders. We consistently receive good customer feedback from this policy and I feel that the goodwill and loyalty it earns us is far more valuable than its cost.

Our growing practices at the nursery have always been more or less organic; anyone who sees our fields can testify to the fact that we do not use herbicides. I feel that I am at a crossroads in this regard: either I need to commit to USDA organic certification and use this as a way to market our plants, or I should set aside my inherited phobias and learn to apply herbicides safely and responsibly.

As I look to the future, my biggest challenge is how to make the nursery sustainable for decades to come. I mean this in all pertinent aspects: environmental, financial, physical and emotional. Climate change certainly poses a challenge. Warmer winters, with most precipitation coming in the form of rain rather than snow, and new insect pests are both top of mind for me. Financially, the nursery is profitable, but I draw a salary which is the same as the average journeyman plumber. I sometimes joke that I should have just gone to law school. In reality, trade school would have also landed me with a higher paying job than I currently have. My earnings need to increase in the years to come. Money is not everything, but it is something. Luckily, I married well, and my wife’s salary as a college professor enables us to live comfortably. I still do quite a bit of hard physical work at the nursery, from rock picking to hand weeding graft beds. It pains me when I fall asleep during my son’s bedtime routine after a long strenuous day. As he grows up and

begins to find his own interests, I want to be able to spend more time away from the nursery with him.. To do that, we will have to grow from our current four employees and I will have to learn to delegate more responsibility. Overall, I am optimistic, with the general plan to refocus on growing what we do best. While much hard work remains to be done, such as clearing new growing areas and building more infrastructure, I believe that if this is done in service of producing more of the plants in high demand, I can grow the business gradually year over year, staying true to the values which have brought us so far already.

We’d love to learn about your interests and ideas. Please contact me at 860-283-9393, email Dan@ crickethillgarden.com, and visit us to see for yourself how we grow our crops. We’re located at 670 Walnut Hill Rd., Thomaston, CT 06787, and open for visitation by appointment.

For ‘In First Person,’ Leaflet Editor-in-Chief Wayne Mezitt interviews people in horticulture and adjacent fields by asking a standard set of questions about their work. This column offers an opportunity for people in these fields to share their passions with readers; what motivates them, and how they define and measure success. Based on the idea that we’re often reluctant to talk openly about ourselves because of the potential for miscommunication or misinterpretation, Wayne works with the interviewee to transform their conversation into a personal story from the interviewee’s first-person perspective.

To me, reading through old letters and journals is like treasure hunting. Somewhere in those faded, handwritten lines there is a story that has been packed away in a dusty old box for years.

Sara Sheridan (b.

1968)

Why are old letters important? They are primary sources, i.e., documents that were written during the period being studied. The letters may reveal the writer's opinions and personality, everyday practices, reports on current events and controversies. They can also lead to new discoveries and research paths.

In the Library there was an archival box of folders titled “Founding Correspondence.” The records for that box provided the authors’ names and a vague description of the contents. However, searching the file was problematical and time consuming.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the Library created a remote volunteer project to transcribe the documents. Many people stepped forward and it soon became clear that the label on the box was misleading. It also became clear that transcribing the documents accurately was a challenge. When the Covid restrictions were lifted, the project took another direction that would be more useful for researchers.

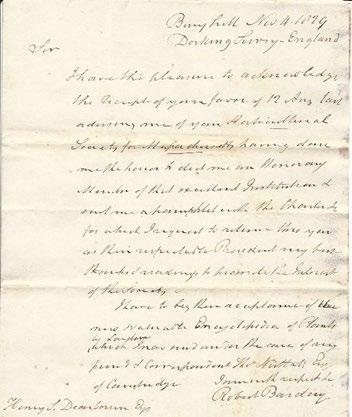

The documents date from the early 19th century and do not concern its founding, except for a few letters to officers. The most frequent

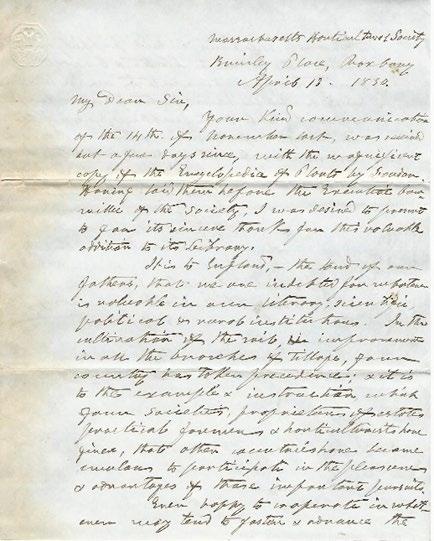

correspondent was General Henry A. S. Dearborn, Society President from 1829-1834. Many letters involve Society business, such as titular memberships and the acquisition of books for the Society’s new Library, many of which were sent by the Society’s agents in London and France by ship. Horticulture was also a frequent subject. A few letters are written in French and need to be translated.

Volunteer Kathleen Glenn, one of the Covid era transcribers, undertook the lead in the project. Volunteer Mackie Mckean assisted her. The result of their work is a research aid that is found here on the Library webpage. The aid includes additional information about the correspondents and a summary of the contents of the correspondence. Kathleen and Mackie have begun working on the next installment of the research aid involving papers from the second half of the 19th century.

Volunteers Kathleen Glenn on the left and Mackie McKean on the right, deciphering one of the Society’s early handwritten documents.

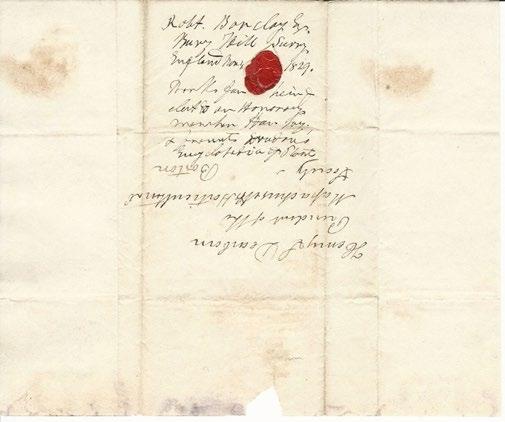

Letter dated November 4, 1929, to President Dearborn from Robert Barclay, of Bury Hill in Dorking, Surrey, England accepting Honorary Membership in the Society. Advises he is sending Loudon’s Encyclopedia of Plants, in care of his friend Thomas Nuttall of Cambridge. Nuttall (17861859). Nuttall, originally from Yorkshire, was a plant explorer, the first professor of Botany at Harvard and curator of its Botanical Garden. He was also an Original Member and Counsellor of the Society. The Library has many early 19th century books by Nuttall in its Collections.

Letter dated April 13, 1830, from President Dearborn responding to Barclay. Dearborn thanks Barclay for sending Loudon’s Encyclopedia of Plants. This book is considered an essential reference book for matters relating to gardens and gardening in the early 19th century and was part of the Society’s Original Library that is stored in our secure offsite storage facility. John Claudius Loudon (1783-1843) was a Scottish botanist, garden designer and author. He was the preeminent horticulture journalist of the early 19th century and influenced the public’s taste in gardens, parks and architecture throughout the Western world.

The next meeting of the Book Club is on Tuesday, August 20th at 1:30 pm. in the Crockett Garden. The club will be discussing The Surprising Life of Constance Spry: From Social Reformer to Society Florist by Sue Shepard. All are welcome to attend. There is no meeting in July.

August 20

The Surprising Life of Constance Spry: From Social Reformer to Society Florist by Sue Shepard

September 17

American Eden by Victoria Johnson

October 15

Mischievous Creatures by Catherine McNeur

COME VISIT!

November 19

The Story of Flowers and how they changed the way we live by Noel Kingsbury

The Library is open on Thursdays from 10am - 1pm and by appointment. Please email Library & Archives Manager Maureen O’Brien for an appointment if you want to schedule a visit.

By Catherine Cooper

brought us a very wet summer, which if you have free draining soil like me was welcome relief from the drought scenario that was 2022. Last summer saw plants flourish with very little intervention from me and I was glad to see that all my plants, including those which supply nectar and pollen, were adequately supported by the weather. However, despite the fact that I had plenty of nectar-rich flowers, the number and variety of butterflies I saw in my yard were much reduced. I don’t know if this was the experience of other Massachusetts residents, but I found it disconcerting how few monarch, and for that matter, any butterflies were in my yard. I believe that I have a decent number of nectar plants through the growing season, but for the most part last year all I saw were cabbage white butterflies. I did see one or two monarchs and other species, but despite my common milkweed plantings (or more accurately self-sown plantings) there was no milkweed munched by monarch caterpillars. To be honest, despite a reasonable number of common milkweed plants the monarchs in my yard have only produced a couple of caterpillars to my knowledge over the years that I have had milkweed. While I don’t believe my yard in one particular summer is an accurate indicator of butterfly populations, last summer did make we wonder what 2024 will bring.

In fact a bit of research has produced some grim news as far as monarch butterflies are concerned. Apparently the winter of 2023 saw the lowest number of monarch butterflies overwintering in Mexico in many years. This past winter they occupied 0.9 of a hectare which was a 59% area decrease from 2022. The reason for this has been attributed to loss of habitat and a drought along the southern part of their migratory path which reduced the availability of nectar producing plants, so it is possible numbers could be reduced this year. Changing weather patterns are having other

effects on monarchs and this might explain why I didn’t see many monarchs last summer. With warm springs in the south, monarchs quickly migrate north and run the risk of outstripping their food supplies, particularly the milkweed needed for their larvae. Overall increasing temperatures mean that spring monarchs are migrating further north with the result that some of those migrating in fall have to travel even further to reach their Mexican wintering grounds. However, before we all draw the conclusion that monarchs are doomed, there is also research that suggests that certain populations are overwintering in states such as California and Florida and that while some parts of the country have experienced declines in numbers, others are not so negatively impacted.

Monarchs are not the only butterfly species facing serious decline. Even butterflies that do not migrate are not immune to temperature changes and warmer winters can affect their ability to manage winter dormancy and/or the timing of their emergence in spring. While this past year’s crisis for the monarchs might be beyond our immediate influence, we cannot remain complacent: monarchs, and other butterflies in general, can struggle to find what they need to survive in a world in which climate change is happening at a rapid rate. Research shows that states like Massachusetts have been seeing

increased numbers of butterflies from warmer states start to make here their home, while butterflies preferring cooler temperatures are showing signs of decline.

What is to be done about this situation? Conservation organizations have been asking us to provide havens for pollinators for a number of years and this work is helping. Not only are nectar rich plants important for adult butterflies, but their caterpillars often depend on far less glamorous plants. Therefore the variety of plants that support butterflies is far greater than might be initially imagined. Common larvae hosts include not only milkweeds, but also grasses, willow, clover, cherries, birch, elm, sassafras, oak, tulip tree, violets and plants in the carrot family. Another way in which we can help overwintering butterflies is to not be overly zealous in our fall clean-up. A little bit of dead stems, leaf litter and dead wood can be beneficial for overwintering insects. And as with other beneficial insects, aim to limit the amount of chemicals used to the absolute minimum necessary.

While it can seem as if the odds are stacked against our butterflies, my research has also suggested that butterfly numbers can recover after a particularly bad year. This has been shown in the past where monarch numbers are concerned, but unfortunately the stresses on butterfly populations from climate change and loss of habitat are not going away any time soon and whatever we can do as individuals, however small, can only be of help. I am generally optimistic by nature and while I realize butterfly populations are experiencing stress, I would also like to think that the red admirals, cabbage whites and painted ladies I saw one warm late April day could be a sign that this year butterflies will make a resurgence in my yard.

Sources:

Monarch Conservation

World Wildlife

Monarch Watch Science Daily

Born in England, Catherine learned to garden from her parents and from that developed a passion for plants. Catherine works assisting customers at the newest Weston Nurseries location in Lincoln. When not at Weston Nurseries, she can often be found in her flower beds or tending to an ever-increasing collection of houseplants.

By Thomas Christpher

I remember visiting local garden guru Felder Rushing in Jackson, Mississippi, many years ago. Felder was (and still is) a deeply skilled horticulturist, but also a playful provocateur. In particular, he celebrated many disparaged aspects of the Southern vernacular garden. For example, I accompanied him on a trip to a bypassed, down-at-theheel little town in the Mississippi Delta where Felder was promoting a scheme to fill every front yard with homemade yard art. His idea was that this would make the town a tourist Mecca. Later, when he was driving his pickup truck north to give a lecture in Boston, he stopped without warning at my Connecticut home to install on my front stoop a planter he’d made from a whitewashed old tire. I woke up that morning to a redneck fait accompli.

One feature of Felder’s own garden I should have paid more attention to during my visit with him was the “privacy fence” that marked the border between his yard and the neighbor’s. This was an ordinary picket fence, except that Felder had cut the pickets thin enough that he could slip an upside-down, empty beer bottle

over the top of each one. This fence provided perfect privacy, Felder explained, because the view of the beer bottles made his neighbor so mad, he couldn’t see past them.

I’m not advocating that you start a neighborhood feud, just that you recognize, as I did at that moment, how hard it can be to see past our own convictions about what is, and what isn’t, beauty. When I was a young gardener, I most admired the informal English cottage gardening style, and I was prone to disparage suburban neighbors who clipped their shrubs into meticulous green globes, cones, and hedges. Eventually, I grew up and accepted that diversity is what makes gardens interesting. That belief has intensified in the last couple of years as I have encountered assertions that we need to take the wild out of native plants so that nurseries will have an easier time growing them and gardeners will have an easier time integrating them into traditional-style suburban plantings. As a University of Connecticut plant breeder explained in a lecture, if we were to identify and then clone dwarf variants of our native shrubs and perennials, that would enable nursery people to process them by machinery during such operations as potting and pruning. And customers who want their plants compact and predictable might be more prone to buying them.

I do not see these changes as benefits. Cloning native plants would eliminate the genetic diversity from their populations, a characteristic that makes them more adaptable and resistant to stresses such as

climatic change. Besides, I like the fact that each native plant is its own individual and not an exact duplicate of its neighbor. For me, the different personalities gives a visit to the garden some of the pleasurable unpredictability I find in a ramble through the woods or fields.

I mentioned this recently to Tom Knezick who is part of the second generation now operating Pinelands Nursery in Columbus, New Jersey. Founded by Tom’s parents in 1983, Pinelands has focused on growing native plants from locally collected seeds for use in environmental restoration projects. With sales in the millions of plants annually, Pinelands is one of the largest growers of natives in the East. Previously, sales were only wholesale, but in 2014, Tom founded a parallel business, Pineland Direct Native Plants, which makes plants from the family nursery available to retail customers via online orders (@pinelands_ direct_native_plants).

During our conversation, Tom mused about the potential appeal to home gardeners of making the plants he sells through Pinelands Direct more uniform and less genetically diverse. Restorationists need the genetic diversity of seed-grown plants, but maybe home gardeners would rather have the more compact, unform look of clones. I replied that the superior adaptation to local soils and conditions of plants recruited from local populations was a major benefit in the garden as well as in the natural landscape. Then I suggested that perhaps what we need to adjust is not the plants but rather our insistence on a single style of garden beauty. Maybe we need to integrate the beauties – and vigor – of the wild with the more domesticated look so many of us prefer around our homes.

To listen to the rest of my conversation with Tom Knezick, log onto the Berkshire Botanical Garden’s “Growing Greener” podcast at www. berkshirebotanical.org.

Be-a-Better-Gardener is a community service of Berkshire Botanical Garden, located in Stockbridge, Mass. Its mission, to provide knowledge of gardening and the environment through a diverse range of classes and programs, informs and inspires thousands of students and visitors each year. Thomas Christopher is a volunteer at Berkshire Botanical Garden and is the author or co-author of more than a dozen books, including Nature into Art and The Gardens of Wave Hill (Timber Press, 2019). He is the 2021 Garden Club of America's National Medalist for Literature, a distinction reserved to recognize those who have left a profound and lasting impact on issues that are most important to the GCA.